Essay Extender for Students

Have you ever struggled to reach the specific word count while writing an essay? Our online essay extender can help you get the desired word count with just a few simple steps. All you have to do is:

- Copy and paste your essay.

- Choose how many words you need in your paper.

- Click the "Extend" button.

💎 5 Key Advantages of the Essay Extender

🙋 when to use the ai essay extender, 📜 essay extender free examples, 🖇️ essay word extender tips, 🔗 references.

Our essay word extender offers a range of benefits that can enhance your writing experience. Here are some of them:

With its user-friendly interface, our online essay extender can assist you in various ways. Check out these ideas on how you can use the tool.

1. To Increase the Word Count

One of the most common uses of our essay extender is to increase an essay's word count. You add words to the entire text or a specific part, for example, introduction, conclusion, or body paragraphs. This gives you more control over where you want to expand an essay and helps you tailor the extension to the academic requirements .

Our tool adds words without compromising the quality of their writing. Since it uses advanced AI algorithms, it extends the text while maintaining the coherence and flow of the original content.

2. To Add a New Part

AI essay extender can also help you add a new part to your essay. For example, if you have already written the introduction and body paragraphs but are struggling with the conclusion, our tool can generate it.

Similarly, if you need to add a new body paragraph to support your argument , our essay extender can generate a paragraph based on your prompt. This feature is particularly useful when you are short on time and need to complete your essay quickly.

3. To Get New Ideas

Sometimes, you only need a fresh perspective to improve your writing. Our essay extender can generate unique ideas by developing a body paragraph on any topic. This feature is helpful for those who are stuck with their writing and need some inspiration to continue. You can use this generated paragraph as a starting point and further develop it according to your ideas and arguments.

Wanna see how essay extender generator works in practice? Let's try it together. Imagine you're writing an argumentative essay on "Should all internships be paid?" We'll use our tool to add some words to a body paragraph and then develop an effective introduction.

All internships should be paid for the simple fact that interns are providing valuable work and skills to the company. It is unfair to expect young workers, who are often already struggling with student debt, to work for free. Interns are not just shadowing or observing; they actively contribute to the company's operations and success. By not compensating them, companies are perpetuating a cycle of unpaid labor and exploiting the enthusiasm and eagerness of young workers. Furthermore, paying interns shows that their time and contributions are valued, allowing them to gain practical experience without financial strain.

All internships should be paid for the simple fact that interns are providing valuable work and skills to the company. It is unfair to expect young workers, who are often already struggling with student debt, to work for free. Interns are not just shadowing or observing; they actively contribute to the company's operations and success. For example, a student who is completing an unpaid internship at a marketing firm may be responsible for creating social media content, conducting market research, and assisting with client meetings. These tasks require time, effort, and skills, and the intern should be compensated for their contributions. By not compensating them, companies are perpetuating a cycle of unpaid labor and exploiting the enthusiasm and eagerness of young workers. Moreover, unpaid internships often come with hidden costs that can be a significant burden for students. For instance, a student interning in a different city may have to cover transportation, housing, and other expenses on top of working for free. Furthermore, paying interns shows that their time and contributions are valued, allowing them to gain practical experience without financial strain. Companies should recognize the contributions interns bring to their organization and compensate them accordingly for their hard work.

Internships have become a common way for students to gain practical experience and valuable skills in their chosen field. However, the issue of whether these internships should be paid or not has sparked a debate. While some argue that unpaid internships provide valuable learning opportunities, others believe that all internships should be paid to ensure fair treatment of young workers. In this essay, we will explore why all internships should be paid, including the value that interns bring to organizations and the hidden costs of unpaid internships.

Check out these helpful tips to work on your academic writing skills and extend an essay manually.

- Expand your arguments . Instead of simply stating your point, provide more detailed examples to support your ideas.

- Use transitional phrases . Transition phrases such as "in addition," "furthermore," and "moreover" can help you connect your ideas and add more depth to your essay.

- Include relevant statistics and data . Adding statistics and data from reliable sources can boost the credibility of your essay and help you expand your arguments.

- Incorporate quotes . Including quotes from experts or authoritative individuals adds depth and weight to your essay.

- Provide background information . If you feel that certain concepts need more explanation, you can provide background information to help the reader better understand your points.

Remember, when expanding on your arguments, it is essential to do so smartly. This means providing detailed explanations and relevant examples that add length to your essay and strengthen your points.

❓ Essay Extender FAQ

Updated: Dec 11th, 2023

- How to Increase or Decrease Your Paper’s Word Count | Grammarly

- How to Increase Your Essay Word Count - Word Counter Blog

- Transitions - The Writing Center • University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- What Are Filler Words? (Examples and Tips To Avoid Them) | Indeed.com

- How to Write an Introduction Paragraph in 3 Steps

- Free Essays

- Writing Tools

- Lit. Guides

- Donate a Paper

- Referencing Guides

- Free Textbooks

- Tongue Twisters

- Job Openings

- Expert Application

- Video Contest

- Writing Scholarship

- Discount Codes

- IvyPanda Shop

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Copyright Principles

- DMCA Request

- Service Notice

On this page, you can find a free essay extender for students. With the help of this tool, you can increase the word count of any text – paste it into the related field and add the necessary details. The essay extender can add particular paragraphs or double your words in two clicks! Don’t miss the helpful tips and examples of text expansion.

You can always rewrite, expand, or shorten your essays from here !

What's an AI Essay Exdender

AI Essay Extender is a free online generator tool that uses AI technology to extend essays. Simply paste your essay and get a longer, more comprehensive version in seconds.

The Ultimate GPT & AI Essay Extender Recommendation- Say Goodbye to Short Essays!

Are you tired of struggling to meet the word count requirement for your essays? Say hello to Essay Extender - the best essay extender bot that uses advanced AI technology to translate your writing into longer, more comprehensive essays.

You can then:

- Convert and turn your paragraphs and essay from short to longer.

- Generate and write new essays within no time using AI & GPT technology.

The Most Advanced Essay Extender AI

Our recommendation Essay Extender's GPT AI algorithms analyze your writing and generate additional relevant content, ensuring that your essays are not only longer but also more informative and engaging. It's like having your own personal essay translator, helping you to write better essays in less time.

Effortless Paragraph & Essay Expansion

With an Essay Extender, expanding your essays is a breeze. Simply paste your writing into the tool and let AI algorithms do the rest. In seconds, you'll have a longer, more comprehensive essay that's ready to submit. It's that simple!

Extended Definition Essay Examples and Topics

Whether you're writing an extended definition essay or need inspiration for extended essay examples, Essay Extender has you covered. AI algorithms are designed to work with all writing styles and topics, so you can focus on writing and let us take care of the expansion.

Freemium and Safe to Use Essay Inflator

Essay Extender recommendation is free and has an optional premium version to upgrade your inflate your essays and paragraphs. The too is also safe to use, and we never store or share your personal information. So, you can use our GPT & AI essay extender tool suggestions with confidence, knowing that your data is secure.

Who can use an Essay Extender

An essay extender AI tool can be used by a variety of individuals, including:

Students: Students who need to meet a minimum word count for assignments can use an essay extender to elaborate on their ideas or provide additional details.

Writers and Bloggers: Writers and bloggers might use such tools to expand their articles or posts, especially when they are aiming for a comprehensive coverage of a topic.

Researchers: Researchers who need to provide detailed explanations or extended discussions in their papers might find an essay extender useful.

Content Creators: Content creators looking to produce longer forms of content for websites, social media, or other platforms could use these tools to enhance the length and depth of their work.

Educators: Educators, such as teachers and lecturers, may use it to demonstrate how to expand on topics or ideas in a more detailed way.

Business Professionals: In the corporate world, professionals may use it to elaborate on reports, proposals, or other documents where comprehensive detail is necessary.

It's important to note that while essay extenders can increase the length of a text, the quality and coherence of the output may vary. Users should always review and edit the extended content to ensure it maintains the desired level of quality and relevance to the topic.

Best Essay Extender Generator

Essay Extender is quickly becoming the go-to best essay inflator and expander for thousands of users who want to write better essays in less time. So why wait? Try Essay Extender today and experience the power of AI technology for yourself!

Extend Your Essays Free with Ease

Want to know the best ways to extend your essay? Look no further than Essay Extender. AI algorithms make it easy to expand your writing and add relevant, engaging content. So, why not try Essay Extender suggestions today and take your writing to the next level?

Get the best of our recommendation tools to generate and write longer essays!

How to Extend an Essay Manually

To manually make an essay longer, follow these steps:

1. Elaborate on Key Points : Identify the main points in your essay and expand on them with more details, examples, or illustrations.

2. Add More Examples and Quotations : Support your points with additional examples, case studies, or relevant quotations.

3. Include Counterarguments and Rebuttals : Present opposing viewpoints and then refute them to add significant content.

4. Deepen the Introduction and Conclusion : Revise these sections to be more detailed with background information and implications.

5. Incorporate Related Subtopics : Introduce additional subtopics connected to your main thesis for a broader perspective.

6. Use Descriptive Language : Use descriptive language where appropriate for detailed explanations.

7. Review and Revise for Clarity and Flow : In revision, add content for clarity or to improve the logical flow.

How to Expand an Essay with an AI Extender Tool

To lengthen an essay with an AI extender, follow these steps:

1. Input Your Essay : Input your existing essay into the AI tool.

2. Set Parameters for Extension : Specify how much to extend your essay, by word count or percentage.

3. Use AI Suggestions : The AI tool will generate additional content based on your text.

4. Review AI-Generated Content : Review and edit the AI-generated content to ensure alignment with your essay.

5. Focus on SEO : If intended for online platforms, optimize the content for search engines using relevant keywords.

6. Integrate AI Content with Original Essay : Blend the AI-generated content with your original writing.

7. Final Review and Edit : Perform a final review and edit to ensure the extended essay is polished and coherent.

The Ultimate Guide to Essay Extenders: Maximize Your Word Count

Understanding the Purpose of Essay Extenders

Essay extenders are valuable tools that can help students, writers, and academic professionals meet word count requirements without compromising the quality of their work. These extenders serve the purpose of expanding the content of an essay, allowing for a more comprehensive exploration of ideas and arguments.

Meeting word count requirements is crucial in academic writing as it demonstrates a thorough understanding of the topic and provides ample evidence to support claims. However, many individuals struggle to reach these requirements, resulting in incomplete or insufficient essays.

This is where essay extenders come into play. They enable writers to maximize their word count by providing additional information, examples, and analysis. By utilizing these extenders effectively, writers can enhance their essays with more depth and complexity while maintaining clarity and coherence .

In the following sections, we will explore various techniques for extending your essay effectively and provide tips on using essay extenders without compromising quality. Let's dive in!

Techniques for Effective Essay Extension

When it comes to extending your essay effectively, there are several techniques you can employ. These techniques not only help you meet the word count requirements but also enhance the overall quality of your writing. Let's explore two key strategies: utilizing transitional phrases and words , and expanding on supporting evidence .

1. Utilizing Transitional Phrases and Words

Transitional phrases and words play a crucial role in expanding ideas within your essay. They act as bridges between different paragraphs or sections, allowing for a smooth flow of thoughts and arguments. By incorporating these transitions, you can elaborate on your points and provide additional context.

For instance, phrases like "in addition," "furthermore," and "moreover" can be used to introduce new supporting information or examples. Similarly, words such as "similarly," "likewise," and "comparatively" help draw connections between different ideas or concepts.

To use transitional phrases and words effectively, consider the following tips:

Use them sparingly: While transitions are valuable tools, overusing them can make your writing appear repetitive or forced. Use them strategically where they add value.

Choose appropriate transitions: Select transitions that accurately convey the relationship between ideas. Ensure they fit naturally within the context of your essay.

Maintain coherence: Transitions should contribute to the overall coherence of your essay by guiding readers through your thought process smoothly.

2. Expanding on Supporting Evidence

Providing sufficient evidence is essential for building strong arguments in an essay. To extend your essay effectively, focus on expanding on the supporting evidence you present.

Start by ensuring that you have included enough evidence to support each claim or point you make in your essay. If necessary, conduct further research to find additional sources or examples that strengthen your arguments.

Once you have gathered enough evidence, expand on it by providing detailed explanations, analysis, or relevant anecdotes. This will not only add depth to your essay but also demonstrate a thorough understanding of the topic.

While expanding on supporting evidence, it is crucial to maintain clarity and coherence. Make sure that each piece of evidence directly relates to your main argument and contributes to the overall flow of your essay. Avoid tangents or unrelated information that may confuse or distract your readers.

By utilizing transitional phrases and words effectively and expanding on supporting evidence, you can extend your essay in a meaningful way while maintaining its quality. In the next section, we will explore additional tips for using essay extenders without compromising the clarity and conciseness of your writing.

Tips for Using Essay Extenders Effectively

Using essay extenders effectively requires careful consideration to maintain the quality and coherence of your writing. Here are two key tips to help you make the most out of these tools: avoiding filler words and phrases, and adding relevant examples and case studies.

1. Avoiding Filler Words and Phrases

Filler words and phrases can unnecessarily inflate your essay without adding any meaningful content. They not only waste valuable word count but also dilute the clarity and conciseness of your writing. To use essay extenders effectively, it's important to identify and eliminate these unnecessary elements.

Start by reviewing your essay for words or phrases that do not contribute to the overall message or argument. Common examples of filler words include "very," "really," "basically," and "in my opinion." These words often add little value and can be removed without affecting the meaning of your sentences.

Additionally, watch out for redundant phrases or repetitive statements that can be condensed or eliminated. For example, instead of saying "I personally believe," simply state "I believe."

By eliminating filler words and phrases, you can ensure that every word in your essay serves a purpose, allowing you to focus on expanding substantive content.

2. Adding Relevant Examples and Case Studies

One effective way to extend your essay while maintaining its quality is by incorporating relevant examples and case studies. These provide concrete evidence to support your arguments, making them more persuasive and compelling.

When selecting examples or case studies, ensure they directly relate to the topic at hand. Look for real-life scenarios, research findings, historical events, or personal anecdotes that illustrate key points or demonstrate the validity of your claims.

To find relevant examples, consider conducting additional research in reputable sources such as academic journals, books, or credible websites. Make sure the examples align with the overall argument of your essay and contribute to its coherence.

When incorporating examples and case studies, provide sufficient context and analysis to help your readers understand their significance. Explain how each example supports your main argument and strengthens your overall position.

Remember, the goal is not simply to add more content but to enhance the quality and persuasiveness of your essay. By avoiding filler words and phrases and incorporating relevant examples and case studies, you can effectively extend your essay while maintaining its clarity and coherence.

In the next section, we will explore how to maximize word count without compromising the quality of your writing.

Maximizing Word Count without Compromising Quality

When it comes to extending your essay, it's crucial to strike a balance between meeting word count requirements and maintaining the quality of your writing. While essay extenders can help you reach the desired length, it's important not to sacrifice clarity and coherence in the process.

To ensure that your extended essay remains of high quality, be sure to revise and edit your work thoroughly. This includes checking for grammar and spelling errors, refining your arguments, and ensuring a logical flow of ideas.

Additionally, pay attention to the overall coherence and cohesion of your essay. Each paragraph should contribute to the central thesis, and transitions should guide readers smoothly through your thoughts.

By following these tips and techniques throughout the writing process, you can maximize your word count without compromising the quality of your essay. Happy writing!

Google's Best Practices for SEO: The Ultimate E-A-T Guide

Using ChatGPT for SEO: The Ultimate Beginner's Guide

Biggle's 5x Organic Traffic Growth: Unlocking the Quick Creator

A Blogger's Guide: Making Money with Affiliate Marketing

A Step-by-Step Guide: Adding SEO on Shopify

© Copyright 2024 Quick Creator - All Rights Reserved

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

UMGC Effective Writing Center How to Write an Extended Definition

Explore more of umgc.

- Writing Resources

Usually when you hear the word "definition" you think of a dictionary or encyclopedia. For example, a juvenile delinquent is an underage person convicted of crime or antisocial behavior. Likewise, a venture capitalist is a person who provides money for innovative projects.

Perhaps you have written a narrative essay about a personal experience in which you are called upon to classify and to analyze causes and effects. All of these patterns and more can be used in your paragraphs to clarify and extend the term you have chosen.

Example: Single Pattern

Sometimes a single pattern will be sufficient to extend the definition to achieve the effect you want for your audience. For example, let's say in an introductory sociology course, you are introducing the term "juvenile delinquent" to the class. You could use the "classify" pattern to clarify how broadly the term in used in this field:

- Term: juvenile delinquent

- Standard definition: an underage person who has committed a crime.

- Pattern: Classify

- Overall Point: To understand "juvenile delinquent" in this field, it's necessary to know the major types of delinquents.

- The first type of delinquent is . . .

- The second type of delinquent is . . .

- The third type of delinquent is . . .

Example: Multi Pattern

Depending on the term, you may find that using several patterns is the best way to help shape your audience's understanding of a term. For example, let's consider the innocent sounding term "arbitration." Maybe you wish to make the point that sometimes legal terms are used to desensitize us from what is really taking place. Consider this example:

- Term: Arbitration

- Standard definition: legal process of resolving a dispute

- Classify Pattern--list and define types of arbitration, including "forced arbitration"

- Narration Pattern--The FAIR Act seeks to end the use of forced arbitration by U.S. employers

- Cause/Effect pattern: Multiple examples of the victims of forced arbitration have pressured Congress to act through legislation

Your task in writing an extended definition is to add to the standard/notional definition in a way that will allow your audience to gain a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the term in a particular context. Whether you do this by adding facts, telling what a term does not include, or applying any of the many development patterns (classify, illustrate, cause/effect, compare/contrast, narration, description), matters not. Only the development of clear understanding between you and your audience should be the ultimate goal.

Video Tutorial: Writing the Extended Definition Essay

Follow along with UMGC's Effective Writing Center as they walk through the Extended Definition Essay.

Our helpful admissions advisors can help you choose an academic program to fit your career goals, estimate your transfer credits, and develop a plan for your education costs that fits your budget. If you’re a current UMGC student, please visit the Help Center .

Personal Information

Contact information, additional information.

By submitting this form, you acknowledge that you intend to sign this form electronically and that your electronic signature is the equivalent of a handwritten signature, with all the same legal and binding effect. You are giving your express written consent without obligation for UMGC to contact you regarding our educational programs and services using e-mail, phone, or text, including automated technology for calls and/or texts to the mobile number(s) provided. For more details, including how to opt out, read our privacy policy or contact an admissions advisor .

Please wait, your form is being submitted.

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

60 Writing Topics for Extended Definitions

These essays go beyond dictionary entries using analysis and examples

- Writing Essays

- Writing Research Papers

- English Grammar

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Simply put, a definition is a statement of the meaning of a word or phrase. An extended definition goes beyond what can be found in a dictionary, offering an expanded analysis and illustration of a concept that might be abstract, controversial, unfamiliar, or frequently misunderstood. Take, for example, writings such as William James' "Pragmatic Theory of Truth" or John Berger's " The Meaning of Home ."

Approaching the Abstract

Abstract concepts, including many of the broad terms in the list that follows, need to be "brought to earth" with an example to relate what they mean to your reader and to get your point or opinion across. You could illustrate the concepts with anecdotes from your personal life or examples from the news or current events, or write an opinion piece. There's no single method for developing and organizing a paragraph or essay by extended definition. The 60 concepts listed here can be defined in various ways and from different points of view.

Brainstorming and Prewriting

Start with brainstorming your topic . If you work well with lists, write the word at the top of the paper and fill the rest of the page with all the things that the word makes you think of, feel, see, or even smell, without stopping. It's OK to go off on tangents, as you might find a surprising connection that could make a powerful, insightful, or even humorous essay. Alternatively, brainstorm by writing the word in the middle of your paper and connect other related words to it and each other.

As you develop your angle, think about the concept's background, features, characteristics, and parts. What is the concept's opposite? What are its effects on you or others? Something in your list or word map will spark a writing idea or theme to use to illustrate the abstract concept, and then it's off to the races. If you run into a dead end the first time, go back to your list and pick another idea. It's possible that your first draft turns out to be prewriting and leads to a better idea that can be developed further and can possibly even incorporate the prewriting exercise. Time spent writing is time spent exploring and is never wasted, as sometimes it takes a bit of pursuit to discover the perfect idea.

If seeing examples will help spark your essay, take a look at "Gifts," by Ralph Waldo Emerson, Gore Vidal's "Definition of Prettiness," or "A Definition of Pantomime," by Julian Barnes.

60 Topic Suggestions

Looking for a place to start? Here are 60 words and phrases so broad that writings on them could be infinite:

- Sportsmanship

- Self-assurance

- Sensitivity

- Peace of mind

- Right to privacy

- Common sense

- Team player

- Healthy appetite

- Frustration

- Sense of humor

- Conservative

- A good (or bad) teacher or professor

- Physical fitness

- A happy marriage

- True friendship

- Citizenship

- A good (or bad) coach

- Intelligence

- Personality

- A good (or bad) roommate

- Political correctness

- Peer pressure

- Persistence

- Responsibility

- Human rights

- Sophistication

- Self-respect

- A good (or bad) boss

- A good (or bad) parent

- Learn How to Use Extended Definitions in Essays and Speeches

- The Use of Listing in Composition

- Discover Ideas Through Brainstorming

- Prewriting for Composition

- How to Explore Ideas Through Clustering

- 30 Writing Topics: Analogy

- Compose a Narrative Essay or Personal Statement

- 40 Topics to Help With Descriptive Writing Assignments

- Great Solutions for 5 Bad Study Habits

- How to Write a Descriptive Paragraph

- What Is Depth of Knowledge?

- Thesis: Definition and Examples in Composition

- Instructional Words Used on Tests

- Definition and Examples of Paragraphing in Essays

- Tips for Writing an Art History Paper

Frequently asked questions

What is an essay.

An essay is a focused piece of writing that explains, argues, describes, or narrates.

In high school, you may have to write many different types of essays to develop your writing skills.

Academic essays at college level are usually argumentative : you develop a clear thesis about your topic and make a case for your position using evidence, analysis and interpretation.

Frequently asked questions: Writing an essay

For a stronger conclusion paragraph, avoid including:

- Important evidence or analysis that wasn’t mentioned in the main body

- Generic concluding phrases (e.g. “In conclusion…”)

- Weak statements that undermine your argument (e.g. “There are good points on both sides of this issue.”)

Your conclusion should leave the reader with a strong, decisive impression of your work.

Your essay’s conclusion should contain:

- A rephrased version of your overall thesis

- A brief review of the key points you made in the main body

- An indication of why your argument matters

The conclusion may also reflect on the broader implications of your argument, showing how your ideas could applied to other contexts or debates.

The conclusion paragraph of an essay is usually shorter than the introduction . As a rule, it shouldn’t take up more than 10–15% of the text.

The “hook” is the first sentence of your essay introduction . It should lead the reader into your essay, giving a sense of why it’s interesting.

To write a good hook, avoid overly broad statements or long, dense sentences. Try to start with something clear, concise and catchy that will spark your reader’s curiosity.

Your essay introduction should include three main things, in this order:

- An opening hook to catch the reader’s attention.

- Relevant background information that the reader needs to know.

- A thesis statement that presents your main point or argument.

The length of each part depends on the length and complexity of your essay .

Let’s say you’re writing a five-paragraph essay about the environmental impacts of dietary choices. Here are three examples of topic sentences you could use for each of the three body paragraphs :

- Research has shown that the meat industry has severe environmental impacts.

- However, many plant-based foods are also produced in environmentally damaging ways.

- It’s important to consider not only what type of diet we eat, but where our food comes from and how it is produced.

Each of these sentences expresses one main idea – by listing them in order, we can see the overall structure of the essay at a glance. Each paragraph will expand on the topic sentence with relevant detail, evidence, and arguments.

The topic sentence usually comes at the very start of the paragraph .

However, sometimes you might start with a transition sentence to summarize what was discussed in previous paragraphs, followed by the topic sentence that expresses the focus of the current paragraph.

Topic sentences help keep your writing focused and guide the reader through your argument.

In an essay or paper , each paragraph should focus on a single idea. By stating the main idea in the topic sentence, you clarify what the paragraph is about for both yourself and your reader.

A topic sentence is a sentence that expresses the main point of a paragraph . Everything else in the paragraph should relate to the topic sentence.

The thesis statement is essential in any academic essay or research paper for two main reasons:

- It gives your writing direction and focus.

- It gives the reader a concise summary of your main point.

Without a clear thesis statement, an essay can end up rambling and unfocused, leaving your reader unsure of exactly what you want to say.

The thesis statement should be placed at the end of your essay introduction .

Follow these four steps to come up with a thesis statement :

- Ask a question about your topic .

- Write your initial answer.

- Develop your answer by including reasons.

- Refine your answer, adding more detail and nuance.

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . Everything else you write should relate to this key idea.

An essay isn’t just a loose collection of facts and ideas. Instead, it should be centered on an overarching argument (summarized in your thesis statement ) that every part of the essay relates to.

The way you structure your essay is crucial to presenting your argument coherently. A well-structured essay helps your reader follow the logic of your ideas and understand your overall point.

The structure of an essay is divided into an introduction that presents your topic and thesis statement , a body containing your in-depth analysis and arguments, and a conclusion wrapping up your ideas.

The structure of the body is flexible, but you should always spend some time thinking about how you can organize your essay to best serve your ideas.

The vast majority of essays written at university are some sort of argumentative essay . Almost all academic writing involves building up an argument, though other types of essay might be assigned in composition classes.

Essays can present arguments about all kinds of different topics. For example:

- In a literary analysis essay, you might make an argument for a specific interpretation of a text

- In a history essay, you might present an argument for the importance of a particular event

- In a politics essay, you might argue for the validity of a certain political theory

At high school and in composition classes at university, you’ll often be told to write a specific type of essay , but you might also just be given prompts.

Look for keywords in these prompts that suggest a certain approach: The word “explain” suggests you should write an expository essay , while the word “describe” implies a descriptive essay . An argumentative essay might be prompted with the word “assess” or “argue.”

In rhetorical analysis , a claim is something the author wants the audience to believe. A support is the evidence or appeal they use to convince the reader to believe the claim. A warrant is the (often implicit) assumption that links the support with the claim.

Logos appeals to the audience’s reason, building up logical arguments . Ethos appeals to the speaker’s status or authority, making the audience more likely to trust them. Pathos appeals to the emotions, trying to make the audience feel angry or sympathetic, for example.

Collectively, these three appeals are sometimes called the rhetorical triangle . They are central to rhetorical analysis , though a piece of rhetoric might not necessarily use all of them.

The term “text” in a rhetorical analysis essay refers to whatever object you’re analyzing. It’s frequently a piece of writing or a speech, but it doesn’t have to be. For example, you could also treat an advertisement or political cartoon as a text.

The goal of a rhetorical analysis is to explain the effect a piece of writing or oratory has on its audience, how successful it is, and the devices and appeals it uses to achieve its goals.

Unlike a standard argumentative essay , it’s less about taking a position on the arguments presented, and more about exploring how they are constructed.

You should try to follow your outline as you write your essay . However, if your ideas change or it becomes clear that your structure could be better, it’s okay to depart from your essay outline . Just make sure you know why you’re doing so.

If you have to hand in your essay outline , you may be given specific guidelines stating whether you have to use full sentences. If you’re not sure, ask your supervisor.

When writing an essay outline for yourself, the choice is yours. Some students find it helpful to write out their ideas in full sentences, while others prefer to summarize them in short phrases.

You will sometimes be asked to hand in an essay outline before you start writing your essay . Your supervisor wants to see that you have a clear idea of your structure so that writing will go smoothly.

Even when you do not have to hand it in, writing an essay outline is an important part of the writing process . It’s a good idea to write one (as informally as you like) to clarify your structure for yourself whenever you are working on an essay.

Comparisons in essays are generally structured in one of two ways:

- The alternating method, where you compare your subjects side by side according to one specific aspect at a time.

- The block method, where you cover each subject separately in its entirety.

It’s also possible to combine both methods, for example by writing a full paragraph on each of your topics and then a final paragraph contrasting the two according to a specific metric.

Your subjects might be very different or quite similar, but it’s important that there be meaningful grounds for comparison . You can probably describe many differences between a cat and a bicycle, but there isn’t really any connection between them to justify the comparison.

You’ll have to write a thesis statement explaining the central point you want to make in your essay , so be sure to know in advance what connects your subjects and makes them worth comparing.

Some essay prompts include the keywords “compare” and/or “contrast.” In these cases, an essay structured around comparing and contrasting is the appropriate response.

Comparing and contrasting is also a useful approach in all kinds of academic writing : You might compare different studies in a literature review , weigh up different arguments in an argumentative essay , or consider different theoretical approaches in a theoretical framework .

The key difference is that a narrative essay is designed to tell a complete story, while a descriptive essay is meant to convey an intense description of a particular place, object, or concept.

Narrative and descriptive essays both allow you to write more personally and creatively than other kinds of essays , and similar writing skills can apply to both.

If you’re not given a specific prompt for your descriptive essay , think about places and objects you know well, that you can think of interesting ways to describe, or that have strong personal significance for you.

The best kind of object for a descriptive essay is one specific enough that you can describe its particular features in detail—don’t choose something too vague or general.

If you’re not given much guidance on what your narrative essay should be about, consider the context and scope of the assignment. What kind of story is relevant, interesting, and possible to tell within the word count?

The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to reflect on a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

Don’t worry too much if your topic seems unoriginal. The point of a narrative essay is how you tell the story and the point you make with it, not the subject of the story itself.

Narrative essays are usually assigned as writing exercises at high school or in university composition classes. They may also form part of a university application.

When you are prompted to tell a story about your own life or experiences, a narrative essay is usually the right response.

The majority of the essays written at university are some sort of argumentative essay . Unless otherwise specified, you can assume that the goal of any essay you’re asked to write is argumentative: To convince the reader of your position using evidence and reasoning.

In composition classes you might be given assignments that specifically test your ability to write an argumentative essay. Look out for prompts including instructions like “argue,” “assess,” or “discuss” to see if this is the goal.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

An argumentative essay tends to be a longer essay involving independent research, and aims to make an original argument about a topic. Its thesis statement makes a contentious claim that must be supported in an objective, evidence-based way.

An expository essay also aims to be objective, but it doesn’t have to make an original argument. Rather, it aims to explain something (e.g., a process or idea) in a clear, concise way. Expository essays are often shorter assignments and rely less on research.

An expository essay is a common assignment in high-school and university composition classes. It might be assigned as coursework, in class, or as part of an exam.

Sometimes you might not be told explicitly to write an expository essay. Look out for prompts containing keywords like “explain” and “define.” An expository essay is usually the right response to these prompts.

An expository essay is a broad form that varies in length according to the scope of the assignment.

Expository essays are often assigned as a writing exercise or as part of an exam, in which case a five-paragraph essay of around 800 words may be appropriate.

You’ll usually be given guidelines regarding length; if you’re not sure, ask.

Ask our team

Want to contact us directly? No problem. We are always here for you.

- Email [email protected]

- Start live chat

- Call +1 (510) 822-8066

- WhatsApp +31 20 261 6040

Our team helps students graduate by offering:

- A world-class citation generator

- Plagiarism Checker software powered by Turnitin

- Innovative Citation Checker software

- Professional proofreading services

- Over 300 helpful articles about academic writing, citing sources, plagiarism, and more

Scribbr specializes in editing study-related documents . We proofread:

- PhD dissertations

- Research proposals

- Personal statements

- Admission essays

- Motivation letters

- Reflection papers

- Journal articles

- Capstone projects

Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker is powered by elements of Turnitin’s Similarity Checker , namely the plagiarism detection software and the Internet Archive and Premium Scholarly Publications content databases .

The add-on AI detector is powered by Scribbr’s proprietary software.

The Scribbr Citation Generator is developed using the open-source Citation Style Language (CSL) project and Frank Bennett’s citeproc-js . It’s the same technology used by dozens of other popular citation tools, including Mendeley and Zotero.

You can find all the citation styles and locales used in the Scribbr Citation Generator in our publicly accessible repository on Github .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Common Writing Assignments

9 The Extended Definition Essay

The extended definition essay presents a detailed account of a single term or concept that is central to the content of the course for which the essay is written. What is cryptocurrency? What is a black hole? What is an algorithm? What is symbolism? What is deoxyribonucleic acid? What is National Socialism? Every subject has its own special vocabulary, and teachers will often assign an essay requiring students to present a detailed definition of a key term.

Read carefully this extended definition of feminism.

Example: On Feminism

The word “feminism” describes a popular movement for social justice, based on the premise that women have been and continue to be systemically oppressed by men who do not want to share the greater social, political, and economic power they have historically possessed. But the definition of feminism extends beyond raising the status of one gender; feminism recognizes that equal standards for all people regardless of gender will benefit society as a whole (Montgomery). In this respect, feminism can be interpreted as synonymous with egalitarianism.

Feminist scholars divide the movement into three phases or “Waves.” First-wave feminism emerged in the early twentieth century in the form of a fight for the rights to vote, to own property, and to qualify for work in fields historically reserved for men. Second-wave feminism emerged in the 1960s as baby boomers entered university and demanded admission to programs that traditionally favoured men, such as engineering, medicine, and forestry, as well as “equal pay for work of equal value” (Montgomery). Third-wave or post-feminism is the movement’s twenty-first century incarnation, devoted essentially to ending all forms of gender discrimination. Some even argue that a fourth wave has recently emerged, one that is concerned with the portrayal of women in social media.

While there is no clear consensus as to when first-wave feminism began, most accept that it emerged as industrialization progressed in the nineteenth century. Martha Lear coined the term in 1968, though the first wave focused on what we now consider basic issues of inequality (“What Was”). One of the earliest feminists was Mary Wollstonecraft, who mostly wrote in the late eighteenth century advocating that societies, and individuals specifically, should have rights that the state provides. Most other philosophers and writers of the time ignored women and Wollstonecraft was among the first to call for gender equality. After the American Civil War, Elizabeth Stanton and Susan Anthony rallied support for what they saw as one of the first great obstacles to greater freedom: the right to vote. Others, such as Barbara Leigh Smith, saw employment and education for women as critical areas to focus on.

Throughout the nineteenth century, Biblical interpretation of women’s role in the house and family prevented their ability to advance feminist ideals. To counteract the power of the church’s sex-based hierarchy, Stanton produced an influential work called The Woman’s Bible , in which she argued for equality using biblical references. This helped to provide religious justification, at least for some, for emerging feminism in the period. Furthermore, the National Woman Suffrage Association became a prominent organization, and in 1869, John Allen Campbell, the governor of Wyoming, became the first governor to grant women the right to vote (“What Was”). And when women replaced men in factories during the First World War, many realized that women did have equal skills to men. In Canada, women won the right to vote in most provinces during the war. In 1921, Agnes Macphail became the first woman in Canada elected to Parliament.

In the US, women had to wait a bit longer. Feminist organizations lobbied indefatigably and eventually convinced Congress that women should have the right to vote. Finally, in 1920, women won the right to vote across the United States. While the process itself was contentious, featuring hunger strikes and even mob violence, the gradual acceptance of women as voters can be considered the culminating success of first-wave feminism.

“The Progressive Era” took place in the 1930s; women’s social and political activism grew, and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt advocated for the appointment of women to positions within the administration. Her cause was further advanced during the Second World War when, again, women had to take over the work enlisted men were forced to abandon. After the war, however, North America saw a new emphasis on domesticity. When the soldiers returned, women were almost uniformly fired and forced back into their duties of domestic chores and child-raising (Bisignani). Second-wave feminism was a reaction to this post-war obsession with the ideal of the contented housewife and suburban domesticity, a lifestyle that often isolated women and severely limited their choices and opportunities.

Feminism’s second wave truly began in the early 1960s and focused not just on legal barriers to civil equality but also examined social inequalities. Second-wave feminists sought to change discriminatory policies on sexuality and sexual identity; marriage and child-rearing; workplace environment; reproductive rights; and violence against women. They formed local, regional, and federal government groups on behalf of women, resulting in human rights and women’s equality becoming a growing part of the North American political agenda. Finally, they created new, more positive images of women in both pop culture and the media to fight the negative stereotypes commonly in circulation, primarily that of the “happy housewife.”

The second wave of feminism included many landmark moments. In the 1960s, many government health agencies approved the oral contraceptive pill, and in 1963, the Equal Pay Act was passed in the US. In 1968, Coretta Scott King assumed leadership of the African-American civil rights movement and expanded the platform to include women’s rights. This led to Shirley Chisholm becoming the first African-American woman elected to Congress. In 1972, the passage of Title IX ensured equal funding for women’s opportunities in education, and the first women’s studies program in the US opened at San Diego State University. Perhaps the greatest achievement of the second wave came in 1973, when the Roe v. Wade case resulted in women’s access to safe and legal abortion (Bisignani).

Third-wave feminism began in the 1990s and still exists today (Demarco). There are many different outlets and angles of feminism now, but the most important values of the third wave include gender equality, identity, language, sex positivity, breaking the glass ceiling, body positivity, ending violence against women, fixing the media’s image of women, and environmentalism.

Third-wave feminists assert that there is no universal identity for women; women come from every religion, nationality, culture, and sexual preference. Different forms of media such as fashion magazines, newspapers, and television favour white, young, slender women, a fact which negatively impacts all women and results in body anxiety. To combat this anxiety, modern feminists have fought for body positivity, quashing the opinions of those who believe that overweight people are lazy and unhealthy. Feminists want society’s view of women to expand, to recognize, for example, that it is possible to be beautiful enough to be a model, but also smart enough to be an astronaut or a CEO. But considering that, in 2017, only 18 out of 500 Fortune CEOs and 22 out of 197 global heads of state were women, it is clear that third-wave feminism has not yet removed the glass ceiling (Demarco).

The emerging fourth wavers speak in terms of “intersectionality,” whereby women’s oppression can only fully be understood in the context of marginalization of other groups, who are victims of racism, ageism, classism, and homophobia (Demarco). Among the third wave’s bequests is the importance of inclusion; in the fourth wave, the internet takes inclusion further by levelling hierarchies. The appeal of the fourth wave is that there is a place in it for everyone. The academic and theoretical apparatus are now well-honed and ready to support new broad-based activism in the home, in the workplace, on the streets, and online.

No one is sure how feminism will progress from here. The movement has always included many political, social and intellectual ideologies, each with its own tensions, points and counterpoints. But the fact that each wave has been chaotic, multi-valanced, and disconcerted is cause for optimism; it is a sign that the movement continues to thrive.

Works Cited

Bisignani, Dana. “ Feminism’s Second Wave .” The Gender Press , 27 Jan. 2015, https://genderpressing.wordpress.com/2015/01/27/feminisms-second-wave-2/. Accessed 25 March 2019.

Demarco, April. “ What Is Third Wave Feminist Movement? ” Viva Media , 17 March 2018, https://viva.media/what-is-third-wave-feminist-movement. Accessed 26 March 2019.

Montgomery, Landon. “ The True Definition Of Feminism .” The Odyssey , 8 March 2016, https://www.theodysseyonline.com/the-true-definition-of-feminism. Accessed 27 March 2019.

“ What Was the First Wave Feminist Movement? ” Daily History , 19 Jan. 2019, https://dailyhistory.org/What_was_the_First_Wave_Feminist_Movement%3F. Accessed 28 March 2019.

On Feminism

Study Questions

Respond to these questions in writing, in small group discussion, or both.

- “On Feminism” is an extended definition essay, but it has qualities of what other rhetorical modes explained in this chapter?

- What are the main differences between first- and second-wave feminism?

- What are the main differences between third- and fourth-wave feminism?

- Respond to the conclusions the author offers in her final paragraph. Do you agree with what she writes?

- In academic writing assignments, paragraphs should be unified, coherent, and well-developed. Analyze two body paragraphs from this essay, commenting on the qualities of effective paragraphs they illustrate.

Writing Assignment

Write an extended definition of approximately 750 words on one of the following terms: Marxism, irony (in literature), recession (in economics), pentathlon (as Olympic sport), dressage, algorithm, neutral zone trap, cryptocurrency. You may also select your own topic or one provided by your teacher.

Composition and Literature Copyright © 2019 by James Sexton and Derek Soles is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Try our Favorite AI tools

Intimate app.

All the spells inside the aiwizard spellbook, including Essay Expander are going to be powered by the $WIZM (wizard mana) token.

Click here to find out more.

Essay Expander - aiwizard spellbook

Instructions.

Ready to reach that elusive word count? Paste your essay into the text box below. Once you're set, click "Expand Essay" to allow our AI Essay Expander to work its magic. Your expanded essay will appear in moments, ready for submission or further editing.

Follow @aiwizard_ai on X

Introducing the Essay Expander, a scholarly spell from the aiwizard spellbook that addresses the age-old issue of falling short on word count. Utilizing AI essay expander algorithms, this tool takes your input and embellishes your essay with meaningful content to meet the desired word count. Just paste your essay, hit the "Expand Essay" button, and presto—your essay is instantly expanded without diluting its quality. Perfect for students, writers, and professionals alike, the Essay Expander is the ultimate solution for how to expand an essay effortlessly.

Essay Expander FAQ

What is the essay expander, how much does the essay expander cost, how do i use the essay expander, what are the benefits of using the essay expander.

What is an Essay?

10 May, 2020

11 minutes read

Author: Tomas White

Well, beyond a jumble of words usually around 2,000 words or so - what is an essay, exactly? Whether you’re taking English, sociology, history, biology, art, or a speech class, it’s likely you’ll have to write an essay or two. So how is an essay different than a research paper or a review? Let’s find out!

Defining the Term – What is an Essay?

The essay is a written piece that is designed to present an idea, propose an argument, express the emotion or initiate debate. It is a tool that is used to present writer’s ideas in a non-fictional way. Multiple applications of this type of writing go way beyond, providing political manifestos and art criticism as well as personal observations and reflections of the author.

An essay can be as short as 500 words, it can also be 5000 words or more. However, most essays fall somewhere around 1000 to 3000 words ; this word range provides the writer enough space to thoroughly develop an argument and work to convince the reader of the author’s perspective regarding a particular issue. The topics of essays are boundless: they can range from the best form of government to the benefits of eating peppermint leaves daily. As a professional provider of custom writing, our service has helped thousands of customers to turn in essays in various forms and disciplines.

Origins of the Essay

Over the course of more than six centuries essays were used to question assumptions, argue trivial opinions and to initiate global discussions. Let’s have a closer look into historical progress and various applications of this literary phenomenon to find out exactly what it is.

Today’s modern word “essay” can trace its roots back to the French “essayer” which translates closely to mean “to attempt” . This is an apt name for this writing form because the essay’s ultimate purpose is to attempt to convince the audience of something. An essay’s topic can range broadly and include everything from the best of Shakespeare’s plays to the joys of April.

The essay comes in many shapes and sizes; it can focus on a personal experience or a purely academic exploration of a topic. Essays are classified as a subjective writing form because while they include expository elements, they can rely on personal narratives to support the writer’s viewpoint. The essay genre includes a diverse array of academic writings ranging from literary criticism to meditations on the natural world. Most typically, the essay exists as a shorter writing form; essays are rarely the length of a novel. However, several historic examples, such as John Locke’s seminal work “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding” just shows that a well-organized essay can be as long as a novel.

The Essay in Literature

The essay enjoys a long and renowned history in literature. They first began gaining in popularity in the early 16 th century, and their popularity has continued today both with original writers and ghost writers. Many readers prefer this short form in which the writer seems to speak directly to the reader, presenting a particular claim and working to defend it through a variety of means. Not sure if you’ve ever read a great essay? You wouldn’t believe how many pieces of literature are actually nothing less than essays, or evolved into more complex structures from the essay. Check out this list of literary favorites:

- The Book of My Lives by Aleksandar Hemon

- Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin

- Against Interpretation by Susan Sontag

- High-Tide in Tucson: Essays from Now and Never by Barbara Kingsolver

- Slouching Toward Bethlehem by Joan Didion

- Naked by David Sedaris

- Walden; or, Life in the Woods by Henry David Thoreau

Pretty much as long as writers have had something to say, they’ve created essays to communicate their viewpoint on pretty much any topic you can think of!

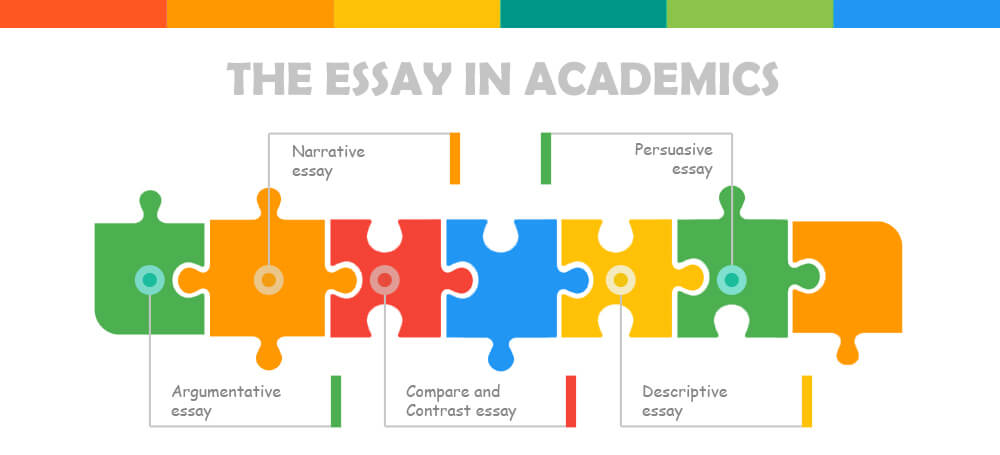

The Essay in Academics

Not only are students required to read a variety of essays during their academic education, but they will likely be required to write several different kinds of essays throughout their scholastic career. Don’t love to write? Then consider working with a ghost essay writer ! While all essays require an introduction, body paragraphs in support of the argumentative thesis statement, and a conclusion, academic essays can take several different formats in the way they approach a topic. Common essays required in high school, college, and post-graduate classes include:

Five paragraph essay

This is the most common type of a formal essay. The type of paper that students are usually exposed to when they first hear about the concept of the essay itself. It follows easy outline structure – an opening introduction paragraph; three body paragraphs to expand the thesis; and conclusion to sum it up.

Argumentative essay

These essays are commonly assigned to explore a controversial issue. The goal is to identify the major positions on either side and work to support the side the writer agrees with while refuting the opposing side’s potential arguments.

Compare and Contrast essay

This essay compares two items, such as two poems, and works to identify similarities and differences, discussing the strength and weaknesses of each. This essay can focus on more than just two items, however. The point of this essay is to reveal new connections the reader may not have considered previously.

Definition essay

This essay has a sole purpose – defining a term or a concept in as much detail as possible. Sounds pretty simple, right? Well, not quite. The most important part of the process is picking up the word. Before zooming it up under the microscope, make sure to choose something roomy so you can define it under multiple angles. The definition essay outline will reflect those angles and scopes.

Descriptive essay

Perhaps the most fun to write, this essay focuses on describing its subject using all five of the senses. The writer aims to fully describe the topic; for example, a descriptive essay could aim to describe the ocean to someone who’s never seen it or the job of a teacher. Descriptive essays rely heavily on detail and the paragraphs can be organized by sense.

Illustration essay

The purpose of this essay is to describe an idea, occasion or a concept with the help of clear and vocal examples. “Illustration” itself is handled in the body paragraphs section. Each of the statements, presented in the essay needs to be supported with several examples. Illustration essay helps the author to connect with his audience by breaking the barriers with real-life examples – clear and indisputable.

Informative Essay

Being one the basic essay types, the informative essay is as easy as it sounds from a technical standpoint. High school is where students usually encounter with informative essay first time. The purpose of this paper is to describe an idea, concept or any other abstract subject with the help of proper research and a generous amount of storytelling.

Narrative essay

This type of essay focuses on describing a certain event or experience, most often chronologically. It could be a historic event or an ordinary day or month in a regular person’s life. Narrative essay proclaims a free approach to writing it, therefore it does not always require conventional attributes, like the outline. The narrative itself typically unfolds through a personal lens, and is thus considered to be a subjective form of writing.

Persuasive essay

The purpose of the persuasive essay is to provide the audience with a 360-view on the concept idea or certain topic – to persuade the reader to adopt a certain viewpoint. The viewpoints can range widely from why visiting the dentist is important to why dogs make the best pets to why blue is the best color. Strong, persuasive language is a defining characteristic of this essay type.

The Essay in Art

Several other artistic mediums have adopted the essay as a means of communicating with their audience. In the visual arts, such as painting or sculpting, the rough sketches of the final product are sometimes deemed essays. Likewise, directors may opt to create a film essay which is similar to a documentary in that it offers a personal reflection on a relevant issue. Finally, photographers often create photographic essays in which they use a series of photographs to tell a story, similar to a narrative or a descriptive essay.

Drawing the line – question answered

“What is an Essay?” is quite a polarizing question. On one hand, it can easily be answered in a couple of words. On the other, it is surely the most profound and self-established type of content there ever was. Going back through the history of the last five-six centuries helps us understand where did it come from and how it is being applied ever since.

If you must write an essay, follow these five important steps to works towards earning the “A” you want:

- Understand and review the kind of essay you must write

- Brainstorm your argument

- Find research from reliable sources to support your perspective

- Cite all sources parenthetically within the paper and on the Works Cited page

- Follow all grammatical rules

Generally speaking, when you must write any type of essay, start sooner rather than later! Don’t procrastinate – give yourself time to develop your perspective and work on crafting a unique and original approach to the topic. Remember: it’s always a good idea to have another set of eyes (or three) look over your essay before handing in the final draft to your teacher or professor. Don’t trust your fellow classmates? Consider hiring an editor or a ghostwriter to help out!

If you are still unsure on whether you can cope with your task – you are in the right place to get help. HandMadeWriting is the perfect answer to the question “Who can write my essay?”

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

- Content Expander

Paragraph Expander helps you expand paragraph into well-structured, engaging content while maintaining the authenticity of the original content.

- Browse all Apps

- Acronym Generator

- Active to Passive Voice Converter

- AI Answer Generator

- AI Essay Generator

- AI Letter Generator

- AI Product Roadmap Generator

- AI Content & Copy Generator

- Amazon Ad Headline Generator

- Amazon Product Bullet Points Generator

- Amazon Product Title Generator

- Article Rewriter

- Author Bio Generator

- Blog Heading Expander

- Blog Outline Generator

- Blog Ideas Generator

- Blog Insights Generator

- Blog Introduction Generator

- Blog Post Generator

- Blog Section Writer

- Blog Title Alternatives Generator

- Blog Title Generator

- Bullet Points Generator

- Bullet Points to Paragraph Generator

- AI Case Study Generator

- AI Case Study Title Generator

- Checklists Ideas Generator

- Compelling Bullet Points Generator

- Conclusion Generator

- Content Idea Generator

- Content Readability Improver

- Content Tone Changer

- Courses Ideas Generator

- eBay Ad Headline Generator

- eBay Product Bullet Points Generator

- eBay Product Description Generator

- eBay Product Title Generator

- Ebooks Ideas Generator

- Editorial Calendar Generator

- Essay Title Generator

- Etsy Ad Headline Generator

- Etsy Product Bullet Points Generator

- Etsy Product Description Generator

- Etsy Product Title Generator

- First to Third Person Converter

- Flipkart Ad Headline Generator

- Flipkart Product Bullet Points Generator

- Flipkart Product Description Generator

- Flipkart Product Title Generator

- Headline Generator - 100% Free AI Tool

- Headline Intro Generator

- Hook Generator

- Local Services Description Generator

- Negative Keyword List Generator

- Pain Agitate Solution Generator

- Paragraph Generator

- Paragraph Shredder

- Paraphrasing Tool (Paraphraser)

- Passive to Active Voice Converter

- Personal Bio Generator (Profile Bio)

- Poll Question and Answers Generator

- Post and Caption Ideas Generator

- Product or Service Generator

- Product Review Generator

- Sentence Rewriter

- Subheadings Generator

- AI Summarizing Tool: Summary Generator

- Synopsis Generator

- Text Extender

- Video Marketing Strategy Generator

- Add Emoji to Text

- Amazon Product Description Generator

- Baby Name Generator: Find the Unique Baby Names

- Chat Message Reply Writer

- Course Description Generator

- Course Name Generator

- Email Subject Line Generator

- Email Writer & Generator

- Excel Formula Generator

- FAQs Generator

- Fitness Exercise & Workout Generator

- Grammar Checker

- Image Generator

- Restaurant Review Generator

- Song Lyrics Generator

- Story Plot Generator

- Storyteller | Storymaker

- Text Rewriter

- What to do?

- Facebook Bio Generator

- Facebook Group Post Comment Generator

- Facebook Group Post Generator

- Facebook Hashtag Generator

- Facebook Poll Questions Generator

- Facebook Post Comment Generator

- Facebook Post Generator

- Hacker News Post Comment Generator

- Hacker News Post Generator

- Hashtag Generator

- IndieHackers Post Generator

- IndieHackers Post Comment Generator

- Instagram Bio Generator

- Instagram Caption Generator

- Instagram Hashtag Generator

- Instagram Reels Ideas Generator

- Instagram Reel Script Generator

- Instagram Threads Bio Generator

- Instagram (meta) Threads Generator

- LinkedIn Hashtag Generator

- LinkedIn Poll Questions Generator

- Linkedin Summary Generator

- LinkedIn Experience Description Generator

- Linkedin Headline Generator

- LinkedIn Post Comment Generator

- LinkedIn Post Generator

- LinkedIn Recommendation Generator

- Pinterest Bio Generator

- Pinterest Board Name Generator

- Pinterest Description Generator

- Pinterest Hashtag Generator

- Poem Generator

- Quora Answer Generator

- Quora Questions Generator

- Reddit Post Generator

- Social Media Content Calendar Generator

- TikTok Bio Generator

- TikTok Caption Generator

- TikTok Content Ideas Generator

- TikTok Hashtag Generator

- TikTok Script Generator

- TikTok Ads Generator

- Tweet Generator AI Tool

- Tweet Ideas Generator

- Tweet Reply Generator

- Twitter Bio Generator

- Twitter Hashtag Generator

- Twitter Poll Questions Generator

- Whatsapp Campaign Template

- YouTube Channel Name Generator

- Youtube Hashtag Generator

- Youtube Shorts Ideas Generator

- Youtube Shorts Script Generator

- YouTube Tags Generator

- YouTube Title Generator

- YouTube Video Script Generator

- About Us Page Generator

- Advertisement Script Generator

- Advertising Campaign Generator

- AI Email Newsletter Generator

- AI SWOT Analysis Generator

- AIDA Generator

- Before After Bridge Copy Generator

- Buyer Challenges Generator

- Buyer Persona Generator

- Call to Action Generator

- Content Brief Generator

- Content Calendar Generator

- Digital Marketing Strategy Generator

- Elevator Pitch Generator

- Email Campaign Template

- Podcast Episode Title Generator AI Tool

- Facebook Ads Generator

- Feature Advantage Benefit Generator

- Feature to Benefit Converter

- Glossary Generator

- Go To Market Strategy Generator

- Google Ad Headline Generator

- AI Google Ads Copy Generator

- AI Google Sheets Formula Generator

- Identify Popular Questions

- Landing Page and Website Copies Generator

- Lead Magnet Generator

- LinkedIn Ad Generator

- Listicle Generator

- Marketing Plan Generator

- Marketing Segmentation Generator

- AI Podcast Name Generator Tool

- Podcast Questions Generator

- Customer Persona Generator

- Press Release Ideas Generator

- Press Release Quote Generator

- Press release Writer

- Product Launch Checklist Generator

- Product Name Generator

- AI Q&A Generator

- Questions and Answers Generator

- Reply to Reviews and Messages Generator

- Slide Decks Ideas Generator

- Slideshare presentations Ideas Generator

- SMS Campaign Template

- Survey Question Generator

- Talking Points Generator

- Twitter Ads Generator

- Youtube Channel Description Generator

- Youtube Video Description Generator

- Youtube Video Ideas Generator

- Webinar Title Generator

- Webinars Ideas Generator

- Whitepapers Ideas Generator

- YouTube Video Topic Ideas Generator

- Keyword Research Strategies Generator

- Keywords Extractor

- Keywords Generator

- Long Tail Keyword Generator

- Meta Description Generator

- SEO Meta Title Generator

- Sales & Cold Calling Script Generator

- Content Comparison Generator

- AI Follow-Up Email Generator

- Icebreaker Generator

- LinkedIn Connection Request Generator

- LinkedIn Followup Message Generator

- LinkedIn Inmail Generator

- LinkedIn Message Generator

- Pain Point Generator

- Proposal Generator

- Sales Qualifying Questions Generator

- AI Sales Email Generator

- Sales Pitch Deck Generator

- Voice Message Generator

- Closing Ticket Response Writer

- Request for Testimonial Email Generator

- Support Ticket Auto Reply Writer

- AI Support Ticket Explainer

- Support Ticket Reply Writer

- Ticket Resolution Delay Response Writer

- Billing Reminder Email Writer

- Customer Contract Summarizer

- Customer QBR Presentation Writer

- Business Meeting Summary Generator

- Monthly Product Newsletter Writer

- Product Questions for Customer Generator

- Business Name Generator

- Business idea pitch generator

- Business ideas generator

- Company Slogan Generator

- Core Values Generator

- Domain Name Generator

- Event Description generator

- Event ideas generator

- Metaphor Generator

- Micro SaaS ideas Generator

- Project Plan Generator

- Startup ideas Generator

- Vision and Mission Generator

- Product Description Generator AI Tool

- Product Description with Bullet Points Generator

- SMS and Notifications Generator

- Tagline and Headline Generator

- Testimonial and Review Generator

- Value Prop Generator

- Informative

- Inspirational

- English (US)

- English (UK) Premium

- English (Australia) Premium

- English (Canada) Premium

- English (India) Premium

- English (Singapore) Premium

- English (New Zealand) Premium

- English (South Africa) Premium

- Spanish (Spain) Premium

- Spanish (Mexico) Premium

- Spanish (United States) Premium

- Arabic (Saudi Arabia)

- Arabic (Egypt) Premium

- Arabic (United Arab Emirates) Premium

- Arabic (Kuwait) Premium

- Arabic (Bahrain) Premium

- Arabic (Qatar) Premium

- Arabic (Oman) Premium

- Arabic (Jordan) Premium

- Arabic (Lebanon) Premium

- Danish (Denmark) Premium

- German (Germany)

- German (Switzerland) Premium

- German (Austria) Premium

- French (France)

- French (Canada) Premium

- French (Switzerland) Premium

- French (Belgium) Premium

- Italian (Italy)

- Italian (Switzerland) Premium

- Dutch (Netherlands) Premium

- Dutch (Belgium) Premium

- Russian (Russia)

- Portuguese (Portugal)

- Portuguese (Brazil) Premium

- Chinese (China) Premium

- Chinese (Taiwan) Premium

- Chinese (Hong Kong) Premium

- Chinese (Singapore) Premium

- Korean (South Korea) Premium

- Japanese (Japan)

- Finnish (Finland) Premium

- Greek (Greece) Premium