Child Marriage Essay

500 words child marriage essay.

Child Marriage continues to be a prevalent practice in many parts of the world . Even though the world is evolving at a fast pace, there are some regions that can’t seem to move on with times. What’s sad is the dark reality of child marriage which is not considered often. Child marriage is basically the formal or informal marriage of a child with or without their consent, under the age of 18. In most cases, the boy or man is older than the girl. Through a child marriage essay, we will throw light on this social issue.

Causes and Impact of Child Marriage

Child marriage is no less than exploitation of right. In almost all places, the child must be 18 years and above to get married. Thus, marrying off the child before the age is exploiting their right.

One of the most common causes of child marriage is the tradition which has been in practice for a long time. In many places, ever since a girl is born, they consider her to be someone else’s property.

Similarly, the elders wish to work out their family’s expansion so they marry off the youngsters to characterize their status. Most importantly, poor people practice child marriage to get rid of their loans, taxes, dowry and more.

The impact of child marriage can be life-changing for children, especially girls. The household responsibilities fall on the children. They are not mentally or physically ready for it, yet it falls on them.

While people expect the minor boys to bear the financial responsibilities, the girls are expected to look after the house and family. Their freedom to learn and play is taken away.

Further, their health is also put at risk due to the contraction of sexually transmitted diseases like HIV and more. Especially the girls who get pregnant at a young age, it becomes harmful for the mother as well as the baby.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

How to End Child Marriage

Ending child marriage is the need of the hour. In order to end this social evil, everyone from individuals to world leaders must challenge the traditional norms. Moreover, we must do away with ideas that reinforce that girls are inferior to boys.

We must empower the children, especially girls, to become their own agents of change. To achieve this, they must get access to quality education and allow them to complete their studies so they can lead an independent life later on.

Safe spaces are important for children to be able to express themselves and make their voices heard. Thus, it is essential to remove all forms of gender discrimination to ensure everyone is given equal value and protection.

Conclusion of Child Marriage Essay

To sum it up, a marriage must be a sacred union between mature individuals and not an illogical institution which compromises with the future of our children. The problem must be solved at the grassroots level beginning with ending poverty and lack of education. This way, people will learn better and do better.

FAQ on Child Marriage Essay

Question 1: What are the causes of child marriage?

Answer 1: The causes of child marriages include poverty, dowry, cultural traditions, religious and social pressures, illiteracy, and supposed incapability of women to work for money.

Question 2: How can we end child marriage?

Answer 2: To end child marriage we must also raise awareness about this issue and educate both parents and kids. Further, we must encourage them to be independent first and then search for a partner only after attaining a specific age. Laws should be introduced to tackle this social issue.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Essay on Child Marriage

Students are often asked to write an essay on Child Marriage in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Child Marriage

Introduction.

Child marriage is a global issue where a child, usually under 18 years, is married off. This practice affects both girls and boys but it’s more prevalent among girls.

Causes of Child Marriage

Many factors contribute to child marriage. Poverty, cultural traditions, and lack of education often drive families to marry off their children at a young age.

Consequences

Child marriage has severe consequences. It often leads to early pregnancies, health risks, and limits opportunities for education and career growth.

To end child marriage, we need to focus on education, enforce laws against it, and change societal attitudes.

Also check:

- 10 Lines on Child Marriage

250 Words Essay on Child Marriage

Child marriage, a deeply entrenched social issue, is a practice that involves the marriage of one or both parties before they reach the age of 18. Globally, it is considered a violation of human rights, yet it continues to persist in many societies due to a complex interplay of socio-economic and cultural factors.

The roots of child marriage are multifaceted. Poverty is a significant driver, with families marrying off young daughters to reduce their economic burden. Traditional norms and gender stereotypes also play a role, perpetuating the belief that a girl’s value lies in her ability to become a wife and mother. Furthermore, in some societies, child marriage is used as a strategy to strengthen familial ties or secure political alliances.

Consequences of Child Marriage

The consequences of child marriage are profound and far-reaching. It often results in early pregnancy, posing substantial health risks to young girls whose bodies are not yet mature enough for childbirth. It also hinders girls’ education and personal development, limiting their opportunities and perpetuating cycles of poverty.

Efforts to Combat Child Marriage

Efforts to combat child marriage span from local to global levels. They encompass law enforcement, advocacy for girls’ education, and initiatives to empower girls. However, for these efforts to be effective, it is crucial to address the underlying socio-economic factors that give rise to child marriage.

Child marriage is a complex issue that requires comprehensive, multi-faceted approaches to eradicate. By promoting education, gender equality, and economic stability, societies can help ensure that every child is afforded the right to a safe and fulfilling childhood.

500 Words Essay on Child Marriage

Child marriage, a prevalent practice in many cultures and societies, is a complex issue that infringes upon the rights and development of children, particularly girls. It is a deep-rooted practice, often perpetuated by poverty, gender inequality, traditions, and lack of education. This essay delves into the implications, causes, and potential solutions to child marriage.

The Implications of Child Marriage

Child marriage poses significant risks to the physical, psychological, and emotional well-being of children. It often leads to early pregnancies, which present health risks for both the mother and the child. Moreover, child brides are more likely to experience domestic violence and are less likely to receive proper education. This practice also perpetuates the cycle of poverty, as child brides are less likely to contribute economically to their communities.

Underlying Causes

The causes of child marriage are multifaceted and deeply entrenched in societal norms and structures. Poverty is a significant factor, with families marrying off their daughters to lessen financial burdens. Gender inequality also plays a crucial role, with girls often valued less in societies, leading to their early marriage. Additionally, traditional beliefs and lack of education contribute to the persistence of this practice.

Legislation and Its Limitations

Many countries have enacted laws to prevent child marriage, setting the minimum age for marriage at 18. However, the enforcement of these laws often proves challenging due to societal norms and lack of awareness. Moreover, in some societies, legal loopholes allow child marriage to continue under the guise of cultural or religious practices.

Addressing Child Marriage

Addressing child marriage requires a multifaceted approach. Education is a powerful tool in this regard. Empowering girls through education can help them understand their rights and resist early marriage. Furthermore, educating communities about the detrimental effects of child marriage can foster change in societal attitudes.

Economic empowerment is also crucial. By providing families with financial stability, the economic incentive for child marriage decreases. Social protection measures, such as cash transfers, can help achieve this.

Lastly, legal measures need to be strengthened. Laws against child marriage should be enforced strictly, and legal loopholes need to be addressed.

Child marriage is a violation of children’s rights and a practice that hampers societal development. While it is deeply entrenched in many societies, a combination of education, economic empowerment, and legal measures can help combat this practice. It is crucial for all stakeholders, including governments, NGOs, and communities, to work together to end child marriage and ensure a better future for all children.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Arranged Marriage

- Essay on Army Officer

- Essay on Army Man

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Child Rights Resource centre

Ending child marriage: evidence hub.

Child, early, forced marriage and unions are a violation of human rights that disproportionately affects adolescent girls. Child marriage is a form and cause of gender-based violence that has profound and life-changing impacts on children, their families and subsequent generations. Married girls are denied the freedom to make critical decisions about their own lives. They are disproportionately at risk of an early end to their education, social isolation, ongoing exposure to violence and the risks of death and disability associated with adolescent pregnancy. Around 12 million girls are married every year, 2 million before their 15th birthday. As a child rights organisation dedicated to ensuring all children have an equal opportunity to survive, learn, and live free from violence, Save the Children recognises that urgent action is required to prevent and respond to child, early, forced marriage and unions around the world. Save the Children is committed to advocating for and with girls, supporting child participation and researching best practice on what works to end child marriage. Take a look at our resources on our Ending Child Marriage Evidence Hub.

Photo: Tom Merilion - Overseas aid saves lives

New Research, Tools and Guidance

2 resources

Child Marriage in Humanitarian Crises: Girls and parents speak out on risk and protective factors, decision-making, and solutions

2021 · Human Rights Center at the University of California, Berkeley

Child Marriage is a well-recognized global phenomenon, which may disproportionately impact girls in humanitarian crisis and displacement, such as armed conflict or nature... View Full Abstract

82 pages pdf (16.6 MiB)

Gender & Power (GAP) Analysis Guidance

2021 · Save the Children

Save the Children’s Gender and Power (GAP) Analysis Guidance is an essential tool to examine, understand, and address discrimination and inequality that prevent children, their... View Full Abstract

174 pages PDF (5.5 MiB)

Child Marriage Action Research Series

Toward an End to Child Marriage: Lessons from research and practice in development and humanitarian sectors

2018 · Save the Children International

While child marriage has been on the decline recent decades, there is a growing concern for its increased prevalence in crisis situations during conflict and natural disasters. The... View Full Abstract

94 pages pdf (8.7 MiB)

Global Girlhood Reports

Global Girlhood Report 2021: Girls’ Rights in Crisis

2021 · Save the Children International

From its outset, the COVID-19 pandemic was more than a devastating global health emergency. Crises—including climate change-driven disasters, past epidemics such as Ebola and Zika... View Full Abstract

PDF (1.4 MiB)

The Global Girlhood Report 2020: How COVID-19 is putting progress in peril

2020 · Save the Children International

2020 was supposed to be a once-in-a-generation opportunity for women and girls. The year when governments, businesses, organisations, and individuals came together to develop a... View Full Abstract

49 pages pdf (3.4 MiB)

National and Regional Reports

4 resources

State of the Nigerian Girl: An incisive diagnosis of child marriage in Nigeria

This report confirms our previous analysis that child marriage is both a cause and result of poor education of girls in Nigeria, with 10+ million out-of-school children in the... View Full Abstract

78 pages pdf (4.6 MiB)

Pan-African Girlhood Report 2020: How COVID-19 is putting progress in peril

In Africa, the Protocol to the African Charter on the Rights of Women in Africa (known as ‘the Maputo Protocol’) was adopted on 11 July 2003 to ensure and advance African Women’s... View Full Abstract

28 pages pdf (16.7 MiB)

Married by Exception: Child marriage policies in the Middle East and North Africa

Legal and policy measures that prevent and prohibit child marriage are a key approach to protecting girls from being married before they are ready. To better understand how... View Full Abstract

47 pages pdf (9.5 MiB)

Ending Child Marriage in West Africa: Enhancing policy implementation and budgeting, Sierra Leone and Niger

This budget analysis report was created to assess progress on policy implementation and funding for ending child marriage (ECM) in two West African countries, Niger and Sierra... View Full Abstract

46 pages pdf (2.6 MiB)

9 resources

Spotlight Series: Ending child marriage for gender equality

Gender-based violence against girls: Ending child marriage and accelerating progress for gender equalitySave the Children’s Spotlight series is a collection of country briefings to... View Full Abstract

5 pages PDF (736.2 KiB)

Lead Like a Girl: Ensuring adolescent girls’ meaningful participation in decision-making processes

Adolescent girls have the right to participate in decision-making for matters that affect their lives and their communities, and nearly every country in the world has committed to... View Full Abstract

12 pages pdf (274.5 KiB)

Ending Child Marriage: Child marriage laws and their limitations

2017 · Save the Children International

While many legal restrictions have been employed to address child marriage globally, as many as 7.5 million girls are married illegally each year. This has a profound impact on the... View Full Abstract

12 pages pdf (2.5 MiB)

Experiences of Early Pregnancy among Displaced Female Youth in South Sudan

2022 · Feinstein International Center, Tufts University

This briefing paper follows the lives of displaced female youth in South Sudan that had unintended pregnancies under the age of 18. This paper explores the circumstances leading to... View Full Abstract

18 pages PDF (482.5 KiB)

Life after Marriage: An analysis of the experiences of conflict-affected female youth who married under age 18 in South Sudan and the Kurdistan region of Iraq

This briefing paper examines the experiences of life after marriage for female youth who married under the age of 18 in South Sudan and the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. This paper... View Full Abstract

18 pages PDF (932.3 KiB)

Perspectives on Early Marriage: The voices of female youth in Iraqi Kurdistan and South Sudan who married under age 18

This briefing paper focuses on the decision-making processes that led displaced female youth to marry as minors in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and South Sudan, based on the actual... View Full Abstract

24 pages PDF (1.3 MiB)

Circumscribed Lives: Separated, divorced, and widowed female youth in South Sudan and the Kurdistan region of Iraq

This briefing paper follows the lives of female youth that married as minors and later became separated, divorced or widowed. Authors underscore the unique vulnerabilities and... View Full Abstract

25 pages PDF (989.1 KiB)

The Cost of Being Female: Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) of displaced female youth in South Sudan and the Kurdistan region of Iraq

This briefing paper outlines the general situation of displaced female youth—unmarried, married, divorced, and widowed from a mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) lens.... View Full Abstract

30 pages PDF (998.0 KiB)

“Education is Like Light. The Opposite is Darkness.”: Education and female youth in displacement in South Sudan and the Kurdistan region of Iraq

This briefing paper analyses education for female youth in the context of displacement, particularly the influence of gender norms, community perceptions, and family attitudes on... View Full Abstract

17 pages PDF (423.7 KiB)

By: Save the Childrens Resource Centre

Last updated: 2024-03-1

- Open access

- Published: 14 February 2022

The health consequences of child marriage: a systematic review of the evidence

- Suiqiong Fan 1 &

- Alissa Koski 1 , 2

BMC Public Health volume 22 , Article number: 309 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

33k Accesses

29 Citations

19 Altmetric

Metrics details

Child marriage, defined as marriage before 18 years of age, is a violation of human rights and a marker of gender inequality. Growing attention to this issue on the global development agenda also reflects concerns that it may negatively impact health. We conducted a systematic review to synthesize existing research on the consequences of child marriage on health and to assess the risk of bias in this body of literature.

Methods and findings

We searched databases focused on biomedicine and global health for studies that estimated the effect of marrying before the age of 18 on any physical or mental health outcome or health behaviour. We identified 58 eligible articles, nearly all of which relied on cross-sectional data sources from sub-Saharan Africa or South Asia. The most studied health outcomes were indicators of fertility and fertility control, maternal health care, and intimate partner violence. All studies were at serious to critical risk of bias. Research consistently found that women who marry before the age of 18 begin having children at earlier ages and give birth to a larger number of children when compared to those who marry at 18 or later, but whether these outcomes were desired was not considered. Across studies, women who married as children were also consistently less likely to give birth in health care facilities or with assistance from skilled providers. Studies also uniformly concluded that child marriage increases the likelihood of experiencing physical violence from an intimate partner. However, research in many other domains, including use of contraception, unwanted pregnancy, and sexual violence came to divergent conclusions and challenge some common narratives regarding child marriage.

Conclusions

There are many reasons to be concerned about child marriage. However, evidence that child marriage causes the health outcomes described in this review is severely limited. There is more heterogeneity in the results of these studies than is often recognized. For these reasons, greater caution is warranted when discussing the potential impact of child marriage on health. We provide suggestions for avoiding common biases and improving the strength of the evidence on this subject.

Trial registration

The protocol of this systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020182652) in May 2020.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Marriage before the age of 18, often referred to as child marriage, is a violation of human rights that hinders educational attainment and literacy and may increase the likelihood of living in poverty in adulthood [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Girls are far more likely to marry than boys, and these consequences contribute to existing gender gaps in educational outcomes in some settings [ 6 , 7 ]. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals list child marriage as an indicator of gender inequality and call for an end to the practice by the year 2030 [ 8 ]. Child marriage remains ongoing throughout much of the world despite intensifying efforts to eliminate it [ 9 ].

In addition to its consequences on education, growing attention to child marriage as a global development issue also seems to reflect increasing consideration of its potential impacts on population health. Multinational organizations including the World Bank, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) include the potential for harmful consequences on health among the foremost concerns regarding this practice [ 2 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]. These organizations highlight relationships between child marriage and early childbearing [ 11 , 12 , 13 ], obstetric complications [ 12 , 13 ], violence [ 2 , 12 ], and sexually transmitted infections [ 12 ], among other adverse outcomes.

We undertook this systematic review to synthesize the results of existing research regarding the impact of child marriage on the health of persons who marry before the age of 18. We evaluated the range of health outcomes that have been studied and the geographic distribution of those studies. We also assessed the risk of bias in individual studies and the likelihood that their results reflect causal relationships.

We searched three databases for literature on the relationship between child marriage and health: MEDLINE, Embase, and Ovid Global Health. These databases were chosen because they focus on biomedicine and human health. We aimed to include as broad a range of health outcomes as possible and focusing our search within these databases allowed us to avoid defining specific health outcomes within our search terms. Instead, we searched for studies of child marriage within these databases. This approach made our search terms more concise and the range of outcomes more inclusive. Specific search terms used for each database are included in Supplementary File 1 . We registered our protocol with PROSPERO (CRD42020182652) in May 2020 and conducted our database searches shortly afterward.

We also searched Google Scholar to identify relevant grey literature. Haddaway et al. [ 14 ] found that the majority of grey literature tends to appear within the first 200 citations returned by Google Scholar and recommend focusing on the first 200-300 records. We followed this recommendation and evaluated the first 300 records returned, as sorted by relevance. Search terms used in Google Scholar are also included in Supplementary File 1 . We reviewed the bibliographies of all included studies in an effort to identify any relevant citations not picked up through searches of the databases described above. The search strategy was developed with assistance from a research librarian at McGill University.

Citations returned from searches of all four databases were imported into EndNote X9 and duplicate citations removed [ 15 ]. We transferred all unique citations into Rayyan to facilitate the review process [ 16 ]. A single reviewer (SF) examined the title and abstract of each unique citation for eligibility according to pre-defined criteria specified in the registered protocol. Articles were brought forward for full-text review if they described etiologic studies that used quantitative methods to estimate the effect of child marriage on one or more health outcomes. We defined child marriage as formal or informal union prior to the age of 18. If the title and abstract did not specify the age thresholds used to define child marriage, they were brought forward for full-text review. For example, abstracts that referred to the effect of adolescent or teen marriage without explicitly stating how those exposures were defined were brought forward. Eligible health outcomes included physical or mental health disorders or symptoms of those disorders, as well as health behaviours. Eligible health behaviours included actions like smoking or dietary habits as well as health care seeking, such as prenatal care. We restricted our review to studies in which outcomes were measured at the individual level and to those that measured the effect of child marriage on the individuals married; studies that examined the effect of age at marriage on the offspring of the persons who married were excluded. Studies written in English, French or Chinese were eligible for inclusion.

We excluded studies that used solely qualitative methods and quantitative studies that relied exclusively on hypothesis testing to indicate differences between groups. For example, studies that used chi-squared tests to indicate whether the distribution of some characteristic differed between persons married before the age of 18 and those married at older ages were excluded, even if the authors seemed to interpret their results as causal, because such testing does not result in a comparative effect measure (e.g., a risk difference or an odds ratio) and does not account for potential biases. We also excluded studies in which persons who married before the age of 18 were incorporated into a larger aggregate age category, making the effect of child marriage unidentifiable. For example, comparisons of outcomes among persons who married between 15 and 19 years of age with those who married between 20 and 24 years of age were not eligible for inclusion. Conference presentations and abstracts were also excluded.

Both authors read the full text of each article brought forward from the title and abstract review and independently judged their eligibility according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria described above. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. The following information was extracted from each included study: authors, title, year of publication, the language of publication, country/region in which the study was conducted, study design, study population, sample size, data sources, statistical methods, outcomes, and results.

Risk of bias assessment

We assessed the risk of bias within each included study using the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies - of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool developed by members of the Cochrane Bias Methods Group and the Cochrane Non-Randomised Studies Methods Group [ 17 ]. ROBINS-I is designed to evaluate the risk of bias in non-randomized studies by considering how closely the study’s design and methods approximate an ideal randomized trial. To illustrate, in a hypothetical cluster-randomized trial to estimate the causal effect of child marriage on a specified health outcome, the treatment or intervention would be marriage before the age of 18 years. All children in a specific area (a region, a state, a community, etc.) would be randomized at a very young age to one of two treatment groups: those randomized to the intervention would marry at some point prior to their 18th birthdays (a = 1), while those randomized to the control group would marry on their 18th birthday or any later age (a = 0). All children would then be followed up over a period of time sufficient to observe the specified outcome of interest. In the ideal randomized trial, all persons would adhere to their assigned treatment (i.e., remain married) and would remain in the study until follow-up was complete. After the follow-up period, the probability of the outcome among those assigned to a = 1 would be compared with the same probability among those assigned to a = 0. Under these conditions, we could expect that there would be no differences between those children who married before the age of 18 and those who married afterward aside from age at marriage. As a result, if the probability of the outcome among those randomly assigned to marry as children differed from the probability among those randomly assigned to marry after their 18th birthdays, one could interpret that difference as the causal effect of child marriage [ 18 ].

Of course, a randomized trial like this would be unethical and could never actually be conducted. Researchers interested in the effects of child marriage on health must rely on non-randomized study designs to estimate the causal effect of interest. Without the benefit of randomization, it becomes challenging to identify the causal effect of child marriage because those who marry as children are different from those who marry at later ages in many ways. For example, girls who marry before the age of 18 come from poorer households and from communities with greater gender inequality, on average, compared to those who marry at later ages. These differences are likely to affect their health through causal pathways other than age at marriage, such as the experience of violence or limited ability to access education or health care. This means that a naïve comparison of health outcomes between those who marry as children and those who marry as adults is likely to mix up the consequences of age at marriage with the consequences of childhood poverty and gender inequality.

The ROBINS-I tool requires assessors to carefully consider the potential for multiple sources of bias including confounding, inappropriate selection of participants into the study (i.e., selection bias), mishandling of missing data, and problems with the measurement of exposures and outcomes (i.e., information bias). The potential for bias in each domain is assessed through a series of signaling questions and a summary judgement of low, moderate, serious, or critical risk of bias is then made within each domain. A cross-domain judgement of the risk of bias for the entire study is made based on the risk within each individual domain. Both authors independently assessed the risk of bias in each included study. Disagreements in any single domain or across domains were resolved by discussion.

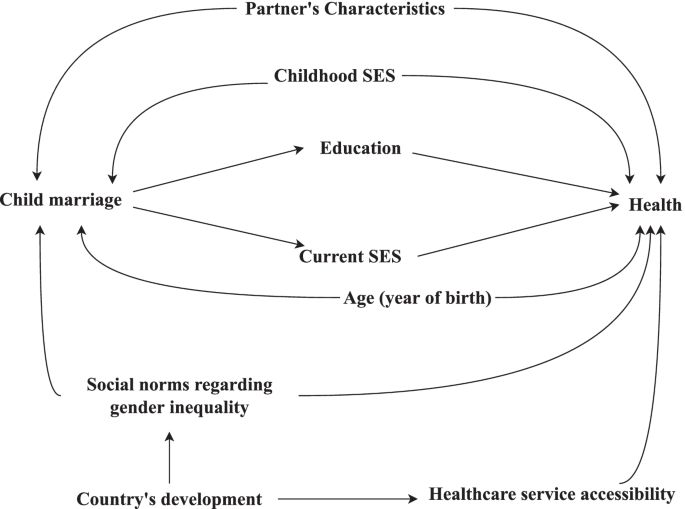

We identified a set of variables likely to confound estimates of the effect of child marriage on a wide range of health outcomes in advance to facilitate assessment of bias in this domain. These variables and their relationships to child marriage and health, broadly defined, are illustrated in the simplified Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) in Fig. 1 . The prevalence of child marriage has fallen over time in many countries, which means that the likelihood of marrying before the age of 18 differs across birth cohorts [ 6 , 19 ]. As discussed above, childhood socioeconomic conditions and gender inequality may lead to child marriage. They may also influence health later in life through a variety of causal pathways. We also considered spousal characteristics a source of confounding because the presence of an available spouse may drive child marriage. For example, a potential husband willing to pay a bride price for a young wife may motivate a family to marry a girl child. The same characteristics of the spouse that may motivate the marriage, such as his age, wealth, and attitudes regarding gender equity, may influence the married child’s health later in life through mechanisms like controlling behaviour. In studies that use pooled data from across multiple regions or countries, it is also important to control for confounding by country/regional-level variables that affect both the probability of child marriage and health. The DAG also illustrates our assumption that the effects of child marriage on health are often mediated through educational attainment and socioeconomic conditions after marriage.

Directed acyclic graph illustrating assumed causal relationships between child marriage and a wide range of health outcomes

We synthesized results narratively. Included studies considered a wide range of health outcomes, as intended given our search strategy. We found it most intuitive and pragmatic to synthesize results within broad outcome categories, such as the effects of child marriage on contraceptive use, on maternal health care, and on mental health. These categories emerged from the data and were not pre-specified. Meta-analyses were not conducted because the studies examined a wide range of health outcomes that were measured in different ways. The serious risk of bias in all included studies, discussed below, also made quantitative synthesis inappropriate.

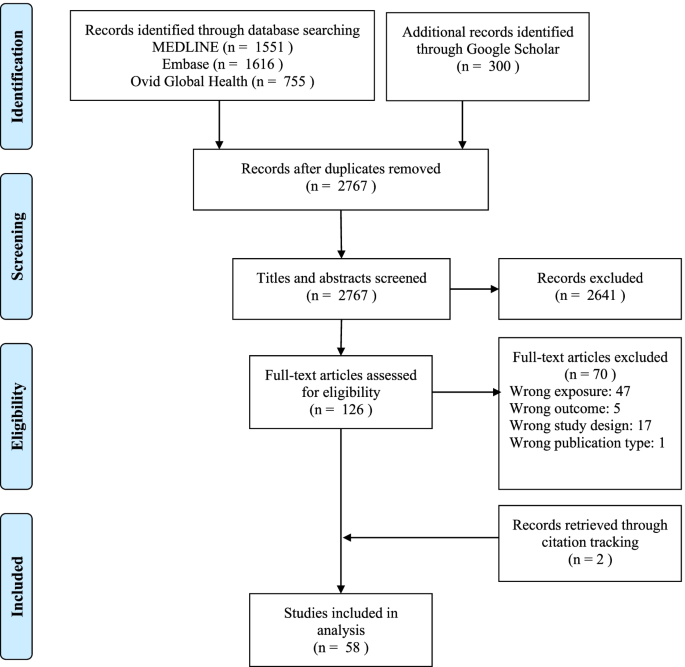

Our search strategy returned a total of 2767 unique records from MEDLINE, Embase, Ovid Global Health and Google Scholar, as shown in Fig. 2 . After title and abstracting screening, the full text of 126 articles was reviewed. Fifty-six of these studies met our inclusion criteria and two additional eligible studies were identified through citation tracking, for a total of 58 included articles.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the process used to identify eligible studies

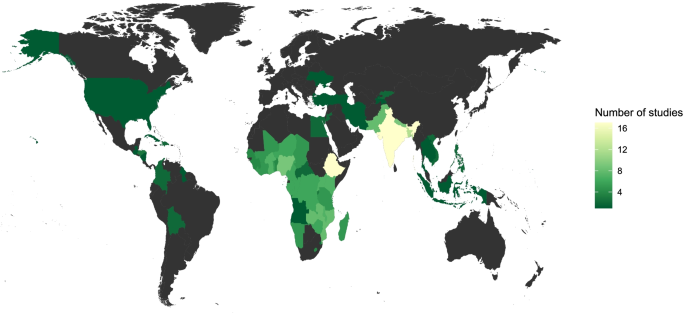

Selected characteristics of all 58 studies included in our review are presented in Table 1 . These studies were published between 1989 and 2020 but the vast majority ( n = 55, 95%) were published in 2010 or later and more than half ( n = 31, 53%) were published between 2016 and 2020, which reflects the relatively recent rise of child marriage on global health and development agendas. Included studies were based in 70 countries across the globe, as illustrated in Fig. 3 . Nearly all studies, 57 of 58, were based in low- and middle-income countries according to World Bank classifications [ 20 ]; the single exception was a study based in the United States [ 21 ]. The geographic distribution of studies included in our review was heavily focused in South Asia ( n = 30, 52%) and Sub-Saharan Africa ( n = 27, 47%), which is perhaps unsurprising given that countries in these regions have some of the highest rates of child marriage in the world [ 9 ]. However, more than half of the studies included in our review were based in just three countries: India ( n = 13), Bangladesh ( n = 8) and Ethiopia ( n = 11). Studies from regions other than South Asia or Sub-Saharan Africa were nearly all included in a handful of studies that analyzed survey data from multiple countries simultaneously [ 22 , 23 , 24 ].

Nearly all included studies, 55 of 58 (95%), were based on the analysis of cross-sectional survey data. More than half ( n = 34, 59%) relied on data from a single source, the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), or their precursor, the World Fertility Surveys (WFS).

Geographic distribution of included studies

Bias assessment

All studies included in our review were determined to be at serious or critical risk of bias based on assessment using ROBINS-I. The summary risk of bias assessment for each study is listed in Table 1 ; risk of bias within each ROBINS-I domain in each study is detailed in Supplementary File 2 . Confounding was the most prevalent concern. Every study was deemed to be at serious to critical risk of bias in this domain, most often because of failure to account for important sources of confounding and inappropriate adjustment for variables affected by age at marriage that are on the causal pathway. Cross-sectional surveys like the DHS often do not collect information necessary to control for confounding. Failure to control for major sources of confounding like childhood poverty and gender inequality may result in overestimation of the harmful effects of child marriage. The second common source of bias was adjustment for variables measured after marriage that are likely on the causal pathway between age at marriage and the health outcomes being studied. To illustrate, the authors of many studies included in this review acknowledged that age at marriage may dictate how long a girl stays in school and that her educational attainment may subsequently influence a wide range of health outcomes. Unfortunately, they then adjusted for educational attainment in regression analyses. This will very likely result in biased estimates because educational attainment was measured after marriage and is more likely to be a mediator than a confounder (Fig. 1 ) [ 79 , 80 ]. Adjusting for it may remove some of the effect of child marriage on health and lead to underestimates of effect. Given that these two issues may bias results in different directions, predicting the net direction of confounding within studies is challenging. Other sources of bias also affected many of the studies in this review, including selection and measurement biases. Few authors discussed the potential influence of bias on their estimates or their conclusions.

The health consequences of child marriage

Studies included in our review estimated the effect of child marriage on a variety of health outcomes. The most common outcomes were measures of reproductive health, such as fertility and fertility control, maternal health care utilization, intimate partner violence, mental health, and nutritional status. The following paragraphs synthesize the literature in each of these categories. In light of the serious risk of bias in all included studies, we interpreted these results with a high degree of caution. We assessed the direction of effect measures, meaning whether the study found that child marriage increased or decreased the probability of experiencing the outcome, and the consistency of directionality across studies within each outcome category. We also assessed the precision of effect measures by evaluating the width of confidence intervals surrounding those measures. We did not interpret the magnitude of the effect estimates from individual studies due to the risk of bias.

The effect of child marriage on the number and timing of births

Eleven studies estimated the effect of child marriage on the number of children born, though this outcome was not consistently measured. Some studies estimated the effect of child marriage on the odds of having given birth to any children [ 34 , 50 , 63 ], the odds of having three or more children [ 24 , 46 , 50 , 63 , 75 ], four or more children [ 34 ], five or more children [ 37 , 69 ], or a continuous measure of the total number of children ever born [ 24 , 25 , 30 , 46 , 54 ]. The age ranges of the people included in these studies also differed, leading to variation in the time frame over which these births could have occurred. Child marriage was correlated with higher fertility in nearly all studies regardless of how the outcome was defined. The only exception was a study from Ethiopia that found no effect [ 30 ]. Ten of these studies focused on fertility exclusively among women. Misunas et al. [ 24 ] focused on men and came to similar conclusions: child marriage increased the odds that men aged 20-29 had fathered three or more children and increased the average number of children fathered by the ages of 40-49 [ 24 ].

A second commonly examined outcome was the likelihood of giving birth within the first year of marriage. Four studies based on data from South Asia [ 39 , 46 , 50 , 63 ] and one study based on pooled data from multiple countries in Africa [ 75 ] examined this outcome. Three of these studies [ 46 , 50 , 75 ] reported that marriage before the age of 18 decreased the odds of giving birth within the first year of marriage. The remaining two [ 39 , 63 ] did not find any evidence of a relationship between child marriage and this outcome.

We also identified five studies that estimated the effect of child marriage on the likelihood of giving birth before a specified age, often referred to as early, teen, or adolescent pregnancy [ 23 , 26 , 31 , 32 , 34 ]. Three of these studies found that child marriage increased the odds of giving birth before the age of 20 [ 26 , 31 , 32 ], the other two reported that child marriage increased the odds of giving birth before the age of 18 [ 23 , 34 ]. Two studies also estimated the effect of child marriage on mean age at first birth and found that those who married before the age of 18 gave birth for the first time at younger ages, on average, than those who married at older ages [ 32 , 46 ].

Collectively, this evidence indicates that women who marry as children often begin having children of their own at earlier ages when compared to their peers who marry after their 18th birthdays, and that they tend to have a larger number of children over their lifetimes. This is not surprising, given that marriage changes sexual behavior in ways that increase the risk of pregnancy. Essentially, girls who marry at earlier ages spend a longer time at risk of pregnancy than those who marry later.

The effect of child marriage on birth intervals

The World Health Organization recommends an interval of at least 24 months between a live birth and a subsequent pregnancy to reduce the risk of poor maternal health outcomes [ 81 ]. Five studies included in our review estimated the effect of child marriage on the likelihood of repeated childbirths in less than two years [ 39 , 50 , 62 , 63 , 75 ]. All five used samples of women between the ages of 20 and 24 who were included in DHS. A sixth study based on a small cross-sectional sample of women aged 15-49 from Ethiopia estimated the effect on repeated childbirth in less than three years [ 27 ]. These studies came to different conclusions. Two studies by the same author reported that child marriage increased the odds of repeated childbirth within two years in India [ 62 , 63 ] but another study based on the same data source found that women who married as children were less likely to have two births within a two-year period than those who married at older ages [ 39 ]. There were also differences in the results of research from Pakistan: one study reported that child marriage made it more likely that women would have two births within two years [ 50 ] while another found no evidence that child marriage influenced this outcome [ 39 ]. Child marriage protected against short birth intervals in Nepal [ 39 ] and in an analysis of data from 34 African countries [ 75 ]. There was no evidence that child marriage influence the likelihood of short birth intervals in Bangladesh [ 39 ].

These results, which range from harmful to protective effects, indicate that child marriage is not clearly or consistently correlated with short birth intervals.

Child marriage, unwanted or mistimed pregnancy, and pregnancy termination

Seven studies estimated the effect of child marriage on the likelihood of experiencing a mistimed or unwanted pregnancy [ 39 , 46 , 47 , 50 , 62 , 63 , 75 ]. All seven were based on analyses of DHS data. The DHS typically asks women whether pregnancies were wanted at the time they occurred, wanted later (i.e., mistimed), or not wanted. Interestingly, six of the seven studies that examined this outcome reduced these categorical responses into a binary measure: women were categorized as having an unwanted pregnancy if they reported that they had a mistimed pregnancy or if they became pregnant when they did not want any more children [ 39 , 46 , 50 , 62 , 63 , 75 ]. The rationale for doing this was not explained in any of the studies. The remaining study [ 47 ] only categorized instances in which a woman became pregnant at a time when she did not want any more children as unwanted.

Estimates of the effect of child marriage on this outcome are mixed. A study from 34 countries in Africa reported that child marriage protected against mistimed/unwanted pregnancies [ 75 ]. Studies from India, Pakistan, and Nepal concluded that child marriage increased the odds of experiencing mistimed/unwanted pregnancy [ 39 , 50 ]. Three studies from Bangladesh came to different conclusions. One found no relationship between child marriage and this outcome [ 39 ] while another reported that child marriage increased the odds of mistimed/unwanted pregnancy [ 46 ]. The third used a different definition of the outcome and found that marriage before the age of 15 was positively associated with unwanted pregnancy (mistimed pregnancies were treated as wanted) but no evidence that marriage between the ages of 15 and 17 affected the likelihood of unwanted pregnancy [ 47 ].

Three of these studies also estimated the effect of child marriage on the likelihood of experiencing two or more mistimed or unwanted pregnancies [ 39 , 62 , 63 ]. Godha et al. reported a large effect of child marriage on having multiple mistimed/unwanted pregnancies in India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan but results were inconclusive in Nepal [ 39 ]. Two studies by the same author reported that child marriage increased the odds of having multiple mistimed/unwanted pregnancies in India [ 62 , 63 ].

We identified eight studies of the effect of child marriage on pregnancy outcomes [ 39 , 47 , 48 , 50 , 57 , 63 , 66 , 75 ]. Six of these relied on the DHS, which typically asks female respondents, “Have you ever had a pregnancy that miscarried, was aborted, or ended in a stillbirth?” [ 82 ]. The wording of this question makes it impossible to examine these outcomes separately. As a result, most studies based on the DHS used a composite outcome that grouped these three events despite differences in their intendedness. Five studies based on the DHS concluded that child marriage increased the odds of having a pregnancy end in either miscarriage, abortion, or stillbirth [ 39 , 48 , 50 , 63 , 75 ]. Exceptionally, the 2007 Bangladesh DHS asked a yes or no question regarding whether a woman had ever terminated a pregnancy. Using responses to this question, Kamal reported that marriage before the age of 15 was correlated with higher odds of termination but no evidence that marriage between 15 and 17 years of age influenced this outcome [ 47 ].

Two studies from India used other cross-sectional data sources and defined their outcomes differently. Santhya et al. used a combined outcome of miscarriage and stillbirth and found that child marriage increased the likelihood of experiencing either of these birth outcomes. [ 66 ]. Paul considered stillbirth and miscarriage separately. Marriage before the age of 15 increased the odds of stillbirth and miscarriage, but marriage between the ages of 15-17 was no less risky in this regard than marriage at 18 or later [ 57 ].

Child marriage and contraceptive use

Fifteen of the studies included in our review estimated the effect of child marriage on various aspects of contraceptive use [ 23 , 24 , 32 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 43 , 46 , 53 , 56 , 62 , 63 , 65 , 66 , 75 ]. All were based on cross-sectional data and thirteen used data from the DHS.

Of these fifteen studies, eight estimated the effect of child marriage on the likelihood that women were using contraception at the time the surveys were conducted [ 32 , 39 , 40 , 46 , 53 , 62 , 63 , 65 ]. As with other outcomes, results were mixed. Child marriage reportedly increased the likelihood of using modern contraception in India and Bangladesh [ 39 ]. Results from Pakistan and Nepal indicate that the same may be true in those countries but the estimates were imprecise [ 39 ]. A second study from Nepal concluded that child marriage led to lower odds of using modern contraception [ 65 ]. The two studies from Nepal used different samples of women, which may partially explain the differences in their results. A study based on pooled data from 18 African countries found that child marriage was correlated with a lower likelihood of using modern contraception [ 53 ]. However, results varied markedly between countries and across geographic regions; in some, child marriage appeared to increase the likelihood of using modern contraception [ 53 ]. In Ghana, de Groot et al. found that child marriage was not correlated with the odds of using any form of contraception or with the use of modern contraceptives [ 32 ].

Two other studies investigated the effect of child marriage on the use of any method of contraception, including those not classified as modern [ 40 , 46 ]. Marriage prior to the age of 15 led to lower odds of contraceptive use in Rwanda, but there was no indication that those who married between 15 and 17 years of age were any more or less likely to use contraception than those who married at older ages [ 40 ]. In Bangladesh, women who married as children were more likely to be using some form of contraception at the time of the survey than those who married at the age of 18 or older [ 46 ]. In yet another iteration of this outcome, Yaya [ 75 ] reported that women who married as children were more likely to have ever used modern contraception. A single study estimated the effect of child marriage among men on the likelihood that they were using modern contraception [ 24 ]. In five of ten countries studied, child marriage was not related to modern contraceptive use. In two (Honduras and Nepal), child marriage seemed to slightly increase the odds of contraceptive use, but it decreased the likelihood in Madagascar [ 24 ].

A second outcome that has received particular focus is whether a woman used contraception before her first pregnancy. All four studies that examined the effect of child marriage on this outcome were based on data from South Asia [ 39 , 56 , 63 , 66 ] and concluded that marrying as a child decreased the likelihood that a woman used contraception prior to her first pregnancy [ 39 , 56 , 63 , 66 ]. The authors of these studies frequently interpreted their results as an indicator of uncontrolled fertility that may place girls and their children at risk of poor health outcomes [ 39 , 56 , 63 ]. However, this relationship is more challenging to interpret because the outcome variables used did not capture whether pregnancies were desired shortly after marriage or the outcomes of those pregnancies.

Four studies estimated the impact of child marriage on the likelihood that a woman had an unmet need for contraception [ 23 , 32 , 41 , 43 ]. This outcome was conceptually defined as a woman who is sexually active but not using contraception and who reports a desire to delay the next birth (a need for spacing), have no more births (a need for limiting), or a combination of the two. Once again, conclusions differ between studies. Using pooled DHS data from 47 countries, Kidman and Heymann found that marrying as a child increased the likelihood that women had an unmet need for contraception to either space or limit births [ 23 ]. An analysis of DHS data from Ethiopia found that women who married as children were less likely to have an unmet need for spacing and less likely to have an unmet need for limiting births compared to women who married at older ages [ 41 ]. In Zambia, child marriage was correlated with a greater unmet need for spacing and for limiting [ 43 ]. In Ghana, de Groot et al. found that child marriage was not correlated with an unmet need for limiting [ 32 ]. These studies all used different samples, which may partially explain the differences in their results.

Child marriage and use of maternal health care

Nine of the studies included in our review estimated the effect of child marriage on the use of health care during pregnancy, at the time of delivery, and during the post-partum period, which we collectively refer to as maternal health care [ 33 , 39 , 49 , 53 , 58 , 62 , 66 , 67 , 74 ].

Studies of prenatal care defined their outcomes as the receipt of at least one prenatal checkup [ 49 , 62 ], the receipt of four or more prenatal checkups [ 49 , 58 , 67 ], or a count of the total number of prenatal checkups received [ 39 , 53 ]. Once again, results within countries come to different conclusions. In Nepal, one study found that women who married as children were less likely to receive four or more prenatal checkups [ 67 ] while another found no evidence that child marriage influenced this outcome [ 39 ]. A study from India found no indication that child marriage affected prenatal care [ 39 ] but two others concluded that child marriage decreased the likelihood of receiving at least one checkup and of receiving at least four checkups [ 58 , 62 ]. In one study from Pakistan, women who married as children were less likely to receive any prenatal care than those who married at older ages, but there was no difference in the likelihood of receiving four or more checkups [ 49 ]. A separate study from the same country reported that child marriage had no effect on the number of prenatal care checkups [ 39 ]. The effect of child marriage on the number of prenatal care visits varied between geographic regions in Africa. In some, child marriage appeared correlated with a decrease the number of visits while in others there was no effect [ 53 ].

Compared to other outcomes, the results of studies that estimated the impact of child marriage on the likelihood of delivering in a health care facility were remarkably consistent. Across geographic locations, all seven studies that examined this outcome concluded that child marriage reduced the likelihood of delivery in a health care facility [ 39 , 49 , 53 , 58 , 66 , 67 , 74 ]. Six of the same studies also found that women who married as children were less likely to have a skilled health care provider present during delivery [ 39 , 49 , 53 , 58 , 67 , 74 ].

Only two studies considered post-natal care [ 58 , 67 ]. One reported that child marriage led to lower likelihood of a post-natal checkup within 42 days of delivery in India [ 66 ] while the other found a lower likelihood of a checkup within 24 h of delivery in Nepal [ 75 ].

Child marriage and intimate partner violence

Sixteen studies estimated the effect of child marriage on the likelihood of experiencing intimate partner violence [ 22 , 23 , 29 , 35 , 38 , 42 , 51 , 53 , 55 , 60 , 62 , 64 , 66 , 70 , 71 , 77 ]. Fifteen of these studies were based on cross-sectional data [ 22 , 23 , 29 , 35 , 38 , 42 , 51 , 53 , 55 , 60 , 62 , 64 , 66 , 70 , 71 ] and eight (50%) were based on the DHS [ 22 , 23 , 51 , 53 , 60 , 62 , 64 , 70 ]. The DHS measures intimate partner violence by asking female respondents a series of questions regarding their experience of specific acts. For example, physical violence is assessed by asking women whether they have been slapped, kicked, or pushed, among other actions. Sexual violence is assessed by asking whether the respondent’s husband has forced her to have sex or perform sex acts when she did not want to. Emotional violence is measured by asking whether her spouse has humiliated or threatened her [ 83 ]. Studies based on data from sources other than the DHS tended to use the same or very similar questions to measure the experience of violence.

Physical violence was the most frequently examined outcome but was measured over different time frames across studies. Some estimated the likelihood of ever having experienced physical violence from a husband or partner while others considered only the year prior to the survey. Still, others focused on the 3 months prior to the survey [ 35 ], the 9 months between survey waves [ 77 ], or during pregnancy [ 38 ]. Regardless of the time period during which violence was measured, the conclusions of these studies were fairly consistent: nearly all reported that marrying as a child increased the likelihood of experiencing physical violence [ 22 , 38 , 51 , 55 , 60 , 64 , 66 , 71 , 77 ]. A study from Ethiopia found no indication that child marriage had an effect on this outcome but it considered a relatively short time period of 3 months [ 35 ].

Estimates of the effect of child marriage on the experience of sexual violence were much less consistent. Two studies from India came to conflicting conclusions. Raj et al. found that child marriage did not increase the likelihood of experiencing sexual violence at any point or in the year prior to the 2005-06 National Family Health Survey [ 64 ]. However, a study by Santhya et al. based on survey data collected from five Indian states between 2006 and 2008 found that child marriage did increase the likelihood of ever experiencing sexual violence [ 66 ]. Studies from Bangladesh and Ghana reported that women who married as children were no more or less likely to experience sexual violence than those who married at later ages [ 60 , 71 ]. Two studies that pooled DHS data across multiple countries also found mixed results [ 22 , 53 ]. Olamijuwon used data from 18 African countries and found that child marriage increased the odds of experiencing sexual violence in Central, East, and Southern Africa, but there was no evidence of a statistical relationship in West Africa [ 53 ]. Kidman used DHS data from 34 countries across the globe and reported that child marriage seemed to increase the odds of experiencing sexual violence in the year prior to the surveys in all included geographic regions except Europe and Central Asia [ 22 ]. Erulkar found that women who married as children in Ethiopia were more likely to report that their first sexual experience was forced [ 35 ].

Only two studies, one from Pakistan and one from Ghana, considered emotional violence as a stand-alone outcome. Both concluded the child marriage led to an increase in the likelihood of ever experiencing emotional violence from an intimate partner [ 51 , 71 ].

Five studies considered only combined outcomes that mixed indicators of physical and sexual violence [ 62 , 70 ], or physical, sexual, and emotional violence [ 23 , 29 , 42 ]. All of these found that child marriage was associated with increased reporting of these composite measures of violence, but some results were sensitive to the sample used and were inconsistent across locations [ 70 ]. Hong Le et al. considered whether child marriage affected the likelihood of violence among boys but was underpowered to detect any effect [ 42 ].

Child marriage and mental health

Five of the studies included in our review estimated the effect of child marriage on various aspects of mental health. These studies relied on cross-sectional data collected from Ghana, Iran, Ethiopia, Niger and the United States [ 21 , 32 , 36 , 44 , 45 ]. Women in the United States who married before the age of 18 were more likely to report experiencing a wide range of mood, anxiety, and other psychiatric disorders in adulthood when compared to those who married at later ages [ 21 ]. The authors of a small study from a single county in Iran found that women who married as children reported more depressive symptoms than those who married at the age of 18 or older [ 36 ]. John, Edmeades, and Murithi examined the relationship between child marriage and multiple domains of psychological well-being in Niger and Ethiopia [ 44 ]. The authors found that marriage before the age of 16 was correlated with poorer overall psychological well-being, but no evidence that marriage between the ages of 16 and 17 was associated with poorer outcomes when compared to women who married at the age of 18 or later [ 44 ]. In Ghana, child marriage seemed to protect against measures of stress. The Ghanaian study also found no indication of differences in levels of social support between women who married before the age of 18 and those who married after their 18th birthdays, though these odds ratio estimates were very imprecise [ 32 ].

Child marriage and nutritional status

Six studies included in our review estimated the effect of child marriage on indicators of nutritional status [ 28 , 34 , 52 , 61 , 76 , 78 ]. Four focused exclusively on pregnant women. Two studies from Ethiopia examined the relationship between child marriage and mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) [ 52 , 76 ]. One reported that pregnant women who married before the age of 18 were more likely to have an MUAC less than 22 cm, often interpreted as a marker of undernutrition [ 84 , 85 ], compared to those who married later on [ 52 ]. The other found that marrying before the age of 15 increased the likelihood of MUAC <22 cm but no evidence that marrying between the ages of 15 and 17 affected this outcome [ 76 ]. A third study from Ethiopia reported that child marriage led to an increase in the prevalence of Vitamin A deficiency among pregnant or recently post-partum women [ 28 ].

Two other studies focused on women who were not pregnant and used body mass index (BMI) as the indicator of nutritional status [ 34 , 78 ]. Their results diverge. Yusuf et al. found that women in Nigeria who married as children were more likely to have a BMI less than 18.5, frequently interpreted as underweight among adults. However, in a study of 35 African countries, Efevbera et al. reported that child marriage was protective against being underweight (BMI<18.5) [ 44 ]. Interestingly, the authors of these studies offered plausible explanations for effects in either direction. Efevbera et al. hypothesize that girls who marry as children may gain access to more plentiful food at an earlier age and that repeated pregnancies during adolescence might result in greater weight gain relative to those who marry at later ages [ 34 ]. In contrast, Nigatu et al. note that repeat pregnancies in quick succession may have a detrimental impact on cumulative nutritional status [ 52 ]. This suggests that the mechanisms through which age at marriage may affect subsequent nutritional status have not been thoroughly considered.

Other health consequences of child marriage

A few of the studies included in our review examined outcomes other than those discussed above. We note them briefly here. A case-control study from India reported that women diagnosed with cervical cancer were more likely to have been married before the age of 18 [ 72 ]. A large, pooled analysis of DHS data from 47 countries reported that child marriage was associated with symptoms of sexually transmitted infections [ 23 ]. A small, cross-sectional study from a single Indian state found no evidence that child marriage led to an increase in the odds of obstetric fistula [ 68 ]. A third study from India examined the effect of child marriage on the odds of experiencing at least one complication during pregnancy, delivery, or within two months after delivery [ 57 ]. Marriage before the age of 15 seemed to increase the likelihood of pregnancy complications, but there was no evidence of an effect for marriage between 15 and 17 years. Child marriage was not associated with delivery complications, but was associated with postnatal complications [ 57 ]. A study from Ghana found no indication that child marriage influenced the likelihood of self-reported poor health, of being ill in the two weeks prior to the survey, or of having a health insurance card but did report that child marriage increased the odds of having difficulty with activities of daily living, such as bending or walking [ 32 ].

Our systematic review synthesized research on the health consequences of marrying before the age of 18. Studies almost uniformly found that women who married before the age of 18 began having children of their own at earlier ages and gave birth to more children over the course of their reproductive lives when compared to those who married at the age of 18 or later. Whether these outcomes, considered alone, are harmful to health is not clear. Though there are many reasons to be concerned about adolescent childbearing, none of the studies of the effect of child marriage on the timing of births considered whether those pregnancies were planned or desired or whether they resulted in obstetric complications or maternal morbidity or mortality [ 23 , 26 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 39 , 46 , 50 , 63 , 75 ]. Similarly, having multiple births, especially at short intervals, may increase the risk of obstetric complications and subsequent morbidity or mortality. However, studies that compared the number of children born to women who married before the age of 18 with the number born to those who married at later ages also did not measure whether those pregnancies were planned or whether they led to harm [ 24 , 25 , 30 , 34 , 37 , 46 , 50 , 54 , 63 , 69 , 75 ]. Rather, studies seemed to assume that these are negative outcomes without directly measuring intentions or harms.

A separate set of studies that estimated the effect of child marriage on the experience of mistimed or unwanted pregnancies came to divergent conclusions: some found that child marriage increased the likelihood of these outcomes but others found that child marriage protected against them or had no effect. Studies of whether child marriage affected the likelihood of obstetric complications, miscarriage or stillbirth did not consider maternal age when those events occurred [ 39 , 47 , 48 , 50 , 57 , 63 , 66 , 75 ]. Moreover, the fact that child marriage corresponds with a larger number of pregnancies means that girls who married prior to the age of 18 had more opportunities to experience these events compared to those who married later; this was not discussed in any of the studies we identified.

The results of studies in other outcome domains are very mixed and challenge some common narratives regarding child marriage. To illustrate, studies included in this review came to conflicting conclusions regarding whether child marriage increases or decreases the use of modern contraception, the likelihood of giving birth within the first year of marriage, and the likelihood of repeated childbirth within two years. Conclusions regarding mistimed and unwanted pregnancies were also mixed, as noted above. Collectively, these results suggest that child marriage is not uniformly characterized by an inability to control the number or timing of births and suggests that a more cautious approach to discussions of agency within these marriages is warranted, at least regarding fertility and fertility control.

Across studies, women who married as children were less likely to give birth in a health care facility or with assistance from a skilled health care provider. These findings raise concerns about access to emergency obstetric care and subsequent birth outcomes for both mother and child. However, we found only one study that estimated the effect of child marriage on the likelihood of complications during pregnancy, delivery, and the postpartum period [ 57 ] and consideration of the consequences for the infants born was beyond the scope of this review. This statistical relationship could be confounded by lack of access due to geographic distance. Child marriage is more common in rural areas, where health care facilities and skilled health care providers may be more spread out. It may also be a function of gender inequality, which may manifest as an inability to seek care without permission. Future research should consider the potential for confounding by these and other variables and investigate whether place modifies this relationship.

Child marriage could plausibly affect many aspects of maternal and reproductive health through complex causal pathways. However, most of the studies included in our review did not discuss causal mechanisms in detail, which may have hindered their ability to identify and account for various sources of bias. More thorough consideration and discussion of these mechanisms would strengthen the theoretical underpinnings of this body of literature and help mitigate biases. For example, use of Directed Acyclic Graphs to illustrate assumed causal relationships would help to clarify the causal pathways being studied and identify sources of bias [ 86 ].

The effects of child marriage among boys have been almost entirely overlooked. Only 2 of the 58 studies included in this review considered boys or men and one of them was underpowered to generate informative estimates [ 42 ]. This intense focus on child marriage among girls reflects the gendered nature of the practice. However, a substantial proportion of boys also marry before the age of 18 in some countries [ 7 , 24 ] and further inquiry into the health consequences among boys is warranted.

The geographic distribution of research on child marriage and health is highly skewed. The focus on South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa may be justified since these regions have some of the highest rates of child marriage in the world. However, it is unclear why just three countries, India, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia, have received such focused attention while other countries in these regions have received very little. Child marriage is certainly ongoing in many other regions of the world that have received little or no research attention, including high-income countries [ 9 , 87 , 88 ].

The geographic distribution of these studies and the range of outcomes considered is clearly reflective of heavy reliance on the DHS. The DHS is appealing because it collects information on age at marriage that is comparable across settings and over time, data are readily accessible and of high quality, and samples are typically nationally representative. However, defaulting to this data source may also have restricted the range of outcomes studied. The DHS focuses primarily on reproductive health and our review included many studies of the effect of child marriage on fertility, contraceptive use, and intimate partner violence. Far less attention has been paid to other potential harms of child marriage that are not included in the surveys, such as indicators of mental health. Importantly, the DHS does not collect information on some of the strongest confounders of many relationships between child marriage and health, including childhood socioeconomic conditions and measures of gender equality. Other data sources will be necessary to increase the geographic scope of this body of research and to overcome some of the limitations inherent in the use of cross-sectional data to estimate causal effects.

All studies included in our review were at serious to critical risk of bias. Quantification of the net magnitude of different biases on the results of each study would have made the project untenable. Considering pervasive bias, we avoided interpreting the magnitude of reported estimates from individual studies and instead took only the directionality of the estimates at face value. This allowed us to assess the (in)consistency of conclusions within domains of health. However, it is entirely possible that bias could lead to a reversal of effects, i.e., estimating a positive effect when the true effect is negative or vice versa. The bias in these studies means that it is unclear whether any of the relationships described are causal.

Nearly all studies included in our review relied on cross-sectional data. There are severe limitations to using cross-sectional research designs to estimate causal effects, and more rigorous designs are needed to further our understanding of the consequences of child marriage. Quasi-experimental designs that more effectively mitigate confounding would strengthen this body of literature and have already been used to study the effect of child marriage on educational attainment and literacy. For example, Field and Ambrus and Sunder used age at menarche as an instrumental variable to study the effect of child marriage on these outcomes [ 3 , 4 ]. Encouragement trials that randomly assign exposure to interventions meant to prevent child marriage could also be used to estimate the effects of child marriage on health outcomes, though such trials are more resource intensive to conduct [ 89 ]. However, given that the DHS and other cross-sectional data sources will likely continue to be used to investigate these relationships, the use of quantitative bias analyses to examine how sensitive estimates are to various sources of bias would be an improvement [ 90 ].

There are several limitations to this systematic review. First, to capture as wide a range of health outcomes as possible, we searched databases focused on human health and biomedicine. Relevant studies from other academic disciplines such as economics and sociology may have been missed using this approach. Second, our search was conducted in English and all included studies were published in English. Eligible studies published in other languages may have been missed, which could influence our conclusions regarding the geographic distribution of research. Finally, as noted in the introduction, child marriage may have consequences beyond the domain of health. We focused our systematic review on the health consequences of child marriage in response to growing rhetoric regarding child marriage as a population health concern. Rigorous systematic reviews of the effect of child marriage on educational and economic outcomes would be a valuable addition to the literature.

Availability of data and materials

The PROSPERO protocol and the data extraction form are publicly available through the Open Science Foundation at https://osf.io/32mu7/ .

Abbreviations

Body Mass Index

Cross-Sectional

Directed Acyclic Graph

Demographic and Health Surveys

Mid-Upper Arm Circumference

Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies - of Interventions tool

Socio-Economic Status

United Nations Population Fund

United Nations Children’s Fund

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Recommendations for Action Against Child and Forced Marriages [Internet]. 2017. Report No.: UNICEF/UN05222/Dragaj. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Women/WRGS/CEFM/RecommendationsForActionEbook.pdf

UNICEF. Early marriage: a harmful traditional practice. New York: UNICEF; 2005.

Google Scholar

Field E, Ambrus A. Early Marriage, Age of Menarche, and Female Schooling Attainment in Bangladesh. J Polit Econ. 2008;116(5):881–930.

Sunder N. Marriage age, social status, and intergenerational effects in Uganda. Demography. 2019;56(6):2123–46.

Dahl GB. Early teen marriage and future poverty. Demography. 2010;47(3):30.

Article Google Scholar

Koski A, Clark S, Nandi A. Has child marriage declined in sub-Saharan Africa? An analysis of trends in 31 countries. Popul Dev Rev. 2017;43(1):7–29.

Gastón CM, Misunas C, Cappa C. Child marriage among boys: a global overview of available data. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2019;14(3):219–28.

United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2018. New York, NY; 2018.

Girls Not Brides. Child Marriage Atlas. [cited 2021 Jul 3]. Available from: https://atlas.girlsnotbrides.org/map/

UNICEF. Ending Child Marriage: Progress and Prospects. New York; 2014. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/media/files/Child_Marriage_Report_7_17_LR.pdf

Wodon Q. Child marriage: A persistent hurdle to health and prosperity. World Bank. 2015 [cited 2020 Jul 28]. Available from: https://blogs.worldbank.org/health/child-marriage-persistent-hurdle-health-and-prosperity

United Nations Population Fund. Marrying too young: end child marriage [Internet]. New York, NY: United Nations Population Fund; 2012 [cited 2020 Apr 27]. Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/shared/documents/publications/2012/MarryingTooYoung.pdf

UNICEF. Child Marriage. 2021 [cited 2020 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/protection/child-marriage

Haddaway NR, Collins AM, Coughlin D, Kirk S. The Role of Google Scholar in Evidence Reviews and Its Applicability to Grey Literature Searching. PLOS ONE. 2015;17(9):e0138237.

Clarivate Analytics. EndNote. 2019 [cited 2020 May 11]. Available from: https://endnote.com/

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016 [cited 2020 Apr 27];355. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/355/bmj.i4919

Hernán MA, Robins JM. Causal Inference: What If. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2020.

Male C, Wodon Q. Girls’ Education and Child Marriage in West and Central Africa: Trends, Impacts, Costs, and Solutions. Forum Soc Econ. 2018;47(2):262–74.

World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Aug 17]. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

Le Strat Y, Dubertret C, Le Foll B. Child marriage in the United States and its association with mental health in women. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3):524–30.

Kidman R. Child marriage and intimate partner violence: a comparative study of 34 countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;dyw225.

Kidman R, Heymann J. Prioritising action to accelerate gender equity and health for women and girls: Microdata analysis of 47 countries. Glob Public Health. 2018;13(11):1634–49.

Misunas C, Gastón CM, Cappa C. Child marriage among boys in high-prevalence countries: an analysis of sexual and reproductive health outcomes. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2019;19(1):25.

Agyei WKA, Mbamanya J. Determinants of cumulative fertility in Kenya. J Biosoc Sci. 1989;21(2):135–44.

Ali M, Alauddin S, Khatun MostF, Maniruzzaman Md, Islam SMS. Determinants of early age of mother at first birth in Bangladesh: a statistical analysis using a two-level multiple logistic regression model. J Public Health. 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 2]; Available from: http://link.springer.com/ https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01228-9

Ayane GB, Desta KW, Demissie BW, Assefa NA, Woldemariam EB. Suboptimal child spacing practice and its associated factors among women of child bearing age in Serbo town, JIMMA zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Contracept Reprod Med. 2019;4(1):4.

Baytekus A, Tariku A, Debie A. Clinical vitamin-A deficiency and associated factors among pregnant and lactating women in Northwest Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019 Dec;19(1):506.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar