Overview – The Definition of Knowledge

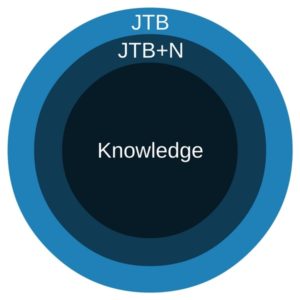

The definition of knowledge is one of the oldest questions of philosophy. Plato’s answer, that knowledge is justified true belief , stood for thousands of years – until a 1963 philosophy paper by philosopher Edmund Gettier challenged this definition.

Gettier described two scenarios – now known as Gettier cases – where an individual has a justified true belief but that is not knowledge.

Since Gettier’s challenge to the justified true belief definition, various alternative accounts of knowledge have been proposed. The goal of these accounts is to define ‘knowledge’ in a way that rules out Gettier cases whilst still capturing all instances of what we consider to be knowledge.

A Level philosophy looks at 5 definitions of knowledge :

- Justified true belief (the tripartite definition)

- JTB + No false lemmas

Reliabilism

Virtue epistemology, infallibilism.

It’s important to first distinguish the kind of knowledge we’re discussing here. Broadly, there are three kinds of knowledge:

- Ability: knowledge how – e.g. “I know how to ride a bike”

- Acquaintance: knowledge of – e.g. “I know Fred well”

- Propositional: knowledge that – e.g. “I know that London is the capital of England”

When we talk about the definition of knowledge, we are talking about the definition of propositional knowledge specifically.

Justified True Belief

The tripartite definition.

In Theaetetus , Plato argues that knowledge is “true belief accompanied by a rational account”. This got simplified to:

‘Justified true belief’ is known as the tripartite definition of knowledge.

Necessary and sufficient conditions

The name of the game in defining ‘knowledge’ is to provide necessary and sufficient conditions.

For example, ‘unmarried’ and ‘man’ are both necessary to be a ‘bachelor’ because if you don’t meet both these conditions you’re not a bachelor. Further, being an ‘unmarried man’ is sufficient to be a ‘bachelor’ because everything that meets these conditions is a bachelor. So, ‘unmarried man’ is a good definition of ‘bachelor’ because it provides both the necessary and sufficient conditions of that term.

The correct definition of ‘knowledge’ will work the same way. Firstly, we can argue that ‘justified’, ‘true’, and ‘belief’ are all necessary for knowledge.

For example, you can’t know something if it isn’t true . If someone said, “I know that the moon is made of green cheese” you wouldn’t consider that knowledge because it isn’t true.

Similarly, you can’t know something you don’t believe. It just wouldn’t make sense, for example, to say “I know today is Monday but I don’t believe today is Monday.”

And finally, justification . Suppose someone asks you if you know how many moons Pluto has. You have no interest in astronomy but just have a strong feeling about the number 5 because it’s your lucky number or whatever. You’d be right – Pluto does indeed have 5 moons – but it seems a bit of a stretch to say you knew Pluto has 5 moons. Your true belief “Pluto has 5 moons” is not properly justified and so would not count as knowledge.

So, ‘justified’, ‘true’, and ‘belief’ may each be necessary for knowledge. But are these conditions sufficient? If ‘justified true belief’ is also a sufficient definition of knowledge, then everything that is a justified true belief will be knowledge. However, this is challenged by Gettier cases .

Problem: Gettier cases

Gettier’s paper describes two scenarios where an individual has a justified true belief that is not knowledge. Both scenarios describe a belief that fails to count as knowledge because the justified belief is only true as a result of luck .

Gettier case 1

- Smith and Jones are interviewing for the same job

- Smith hears the interviewer say “I’m going to give Jones the job”

- Smith also sees Jones count 10 coins from his pocket

- Smith thus forms the belief that “the man who will get the job has 10 coins in his pocket”

- But Smith gets the job, not Jones

- Then Smith looks in his pocket and, by coincidence, he also has 10 coins in his pocket

Smith’s belief “the man who will get the job has 10 coins in his pocket” is:

- Justified: he hears the interviewer say Jones will get the job and he sees that Jones has 10 coins in his pocket

- True: the man who gets the job (Smith) does indeed have 10 coins in his pocket

This shows that the tripartite definition of knowledge is not sufficient : you can have a justified true belief that is not knowledge.

Gettier case 2

Gettier’s second example relies on the logical principle of disjunction introduction (or, more simply, addition ).

Disjunction introduction says that if you have a true statement and add “or some other statement” then the full statement (i.e. “true statement or some other statement”) is also true.

For example: “London is the capital of England” is true. And so the statement “either London is the capital of England or the moon is made of green cheese” is also true, because London is the capital of England. Even though the second part (“the moon is made of green cheese”) is false, the overall statement is true because the or means only one part has to be true (in this case “London is the capital of England”).

Gettier’s second example is as follows:

- Smith has a justified belief that “Jones owns a Ford”

- So, using the principle of disjunctive introduction above, Smith can form the further justified belief that “Either Jones owns a Ford or Brown is in Barcelona”

- Smith thinks his belief that “Either Jones owns a Ford or Brown is in Barcelona” is true because the first condition is true (i.e. that Jones owns a Ford)

- But it turns out that Jones does not own a Ford

- However, by sheer coincidence, Brown is in Barcelona

So, Smith’s belief that “Either Jones owns a Ford or Brown is in Barcelona” is:

- True: “Either Jones owns a Ford or Brown is in Barcelona” turns out to be true. But Smith thought it was true because of the first condition (Jones owns a Ford) whereas it turns out it is true because of the second condition (Brown is in Barcelona)

- Justified: The original belief “Jones owns a Ford” is justified, and so disjunction introduction means that the second belief “Either Jones owns a Ford or Brown is in Barcelona” is also justified.

But despite being a justified true belief, it is wrong to say that Smith’s belief counts as knowledge, because it was just luck that led to him being correct.

This again shows that the tripartite definition of knowledge is not sufficient .

Alternative definitions of knowledge

Gettier cases are a devastating problem for the tripartite definition of knowledge .

In response, philosophers have tried to come up with new definitions of knowledge that avoid Gettier cases.

Generally, these new definitions seek to refine the justification condition of the tripartite definition. True and belief remain unchanged.

JTB + no false lemmas

The no false lemmas definition of knowledge aims to strengthen the justification condition of the tripartite definition.

It says that James has knowledge of P if:

- James believes that P

- James’s belief is justified

- James did not infer that P from anything false

So, basically, it adds an extra condition to the tripartite definition . It says knowledge is justified true belief + that is not inferred from anything false (a false lemma).

This avoids the problems of Gettier cases because Smith’s belief “the man who will get the job has 10 coins in his pocket” is inferred from the false lemma “Jones will get the job” .

- The tripartite definition says Smith’s belief is knowledge, even though it isn’t

- The no false lemmas response says Smith’s belief is not knowledge, which is correct.

So, in this instance, the no false lemmas definition appears to be a more accurate account of knowledge than the tripartite view: it avoids saying Gettier cases count as knowledge.

Problem: fake barn county

However, the no false lemmas definition of knowledge faces a similar problem: the fake barn county situation:

- In ‘fake barn county’, the locals create fake barns that look identical to real barns

- Henry is driving through fake barn county, but he doesn’t know the locals do this

- These beliefs are not knowledge , because they are not true – the barns are fake

- This time the belief is true

- It’s also justified by his visual perception of the barn

- And it’s not inferred from anything false.

According to the no false lemmas definition, Henry’s belief is knowledge.

But this shows that the no false lemmas definition must be false. Henry’s belief is clearly not knowledge – he’s just lucky in this instance.

Reliabilism says James knows that P if:

- James’s belief that P is caused by a reliable method

A reliable method is one that produces a high percentage of true beliefs.

So, if you have good eyesight, it’s likely that your eyesight would constitute a reliable method of forming true beliefs. If you have an accurate memory, it’s likely your memory would also be a reliable method for forming true beliefs. If a website is consistent in reporting the truth, that website would also count as a reliable method.

But if you form a belief through an unreliable method – for example by simply guessing or using a biased source – then it would not count as knowledge even if the resultant belief is true.

Children and Animals

An advantage of reliabilism is that it allows for young children and animals to have knowledge. Typically, we attribute knowledge to young children and animals. For example, it seems perfectly sensible to say that a seagull knows where to find food or that a baby knows when its mother is speaking.

However, pretty much all the other definitions of knowledge considered here imply that animals and young children can not have knowledge. For example, a seagull or a baby can’t justify its beliefs and so justified true belief rules out seagulls and young babies from having knowledge. Similarly, if virtue epistemology is the correct definition, it is hard to see how a seagull or a newly born baby could possess intellectual virtues of care about forming true beliefs and thus possess knowledge.

However, both young children and animals are capable of forming beliefs via reliable processes, e.g. their eyesight, and so according to reliabilism are capable of possessing knowledge.

You can argue against reliabilism using the same fake barn county argument above : Henry’s true belief that “there’s a barn” is caused by a reliable process – his visual perception. Reliabilism would thus (incorrectly) say that Henry knows “there’s a barn” even though his belief is only true as a result of luck.

There are several forms of virtue epistemology (we will look at two), but common to all virtue epistemology definitions of knowledge is a link between a belief and intellectual virtues . Intellectual virtues are somewhat analogous to the sort of moral virtues considered in Aristotle’s virtue theory in moral philosophy . However, instead of being concerned with moral good, intellectual virtues are about epistemic good. For example, an intellectually virtuous person would have traits such as being rational, caring about what’s true, and a good memory.

Linda Zagzebski: What is Knowledge?

Formula for creating gettier-style cases.

Philosopher Linda Zagzebski argues that definitions of knowledge of the kind we have looked at so far (i.e. ‘true belief + some third condition ’) will always fall victim to Gettier-style cases. She provides a formula for constructing such Gettier cases to defeat these definitions:

- E.g. Henry’s belief “there’s a barn” when he is looking at the fake barns

- E.g. Henry’s belief “there’s a barn” when he is looking at the one real barn

- In the second case, the belief will still fit the definition (‘true belief + some third condition ’) because it’s basically the same as the first case

- But the second case won’t be knowledge, because it’s only true due to luck

Zagzebski argues that this formula will always provide a means to defeat any definition of knowledge that takes the form ‘true belief + some third condition’ (whether that third condition is justification , formed by a reliable process , or whatever).

The reason for this is that truth and the third condition are simply added together, but not linked ( the belief is not apt , to use Sosa’s terminology ). The fact that truth and the third condition are not linked leaves a gap where lucky cases can incorrectly fit the definition.

Zagzebski’s definition of knowledge

The issues resulting from the gap between truth and the third condition motivate Zagzebski to do away with the ‘truth’ condition altogether. Instead, Zagzebski’s analysis of knowledge is that James knows that P if:

- James’s belief that P arises from an act of intellectual virtue

However, in Zagzebski’s analysis of knowledge, the ‘truth’ of the belief is kind of implied by the idea of an act of intellectual virtues. This can be shown by drawing a comparison with moral virtue :

An act of moral virtue is one where the actor both intends to do good and achieves that goal. For example, intending to help an old lady across the road but killing her in the process is not an act of moral virtue because it doesn’t achieve a virtuous goal (despite the virtuous intent). Likewise, helping the old lady across the road because you think she will give you money is not an act of moral virtue – even though it succeeds in achieving a virtuous goal – because your intentions aren’t good.

Intellectual virtue is similar: You must both have the correct motivation (e.g. you want to find the truth) and succeed as a result of that virtue (i.e. your belief turns out to be true because you acted virtuously).

Virtues motivate us to pursue what is good. In the case of knowledge, good knowledge is also true. Secondly, virtues enable us to achieve our goals (in the same way a virtuous i.e. good knife enables you to cut) and so intellectual virtues would enable you to reliably form true beliefs.

Sosa’s virtue epistemology

Another virtue epistemology approach to knowledge is Ernest Sosa’s definition of apt belief .

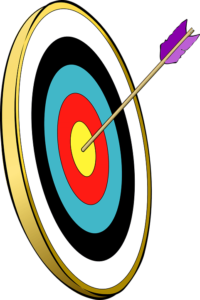

Sosa uses the following analogy to argue that knowledge, like a virtuous shot in archery, has the following three properties: Accuracy , adroitness , and aptness .

Returning to the fake barn county example , Sosa’s virtue epistemology could (correctly) say Henry’s belief “there’s a barn” in fake barn county would not qualify as knowledge – despite being true and formed by a reliable method – because it is not apt . Yes, Henry’s belief is accurate (i.e. true) and adroit (i.e. Henry has good eyesight etc.), but he only formed the true belief as a result of luck, not because he used his intellectual virtues.

Problem: children and animals

As mentioned in more detail in the reliabilism section above , a potential criticism of virtue epistemology is that it appears to rule out the possibility of young children or babies possessing knowledge, despite the fact that they arguably can know many things.

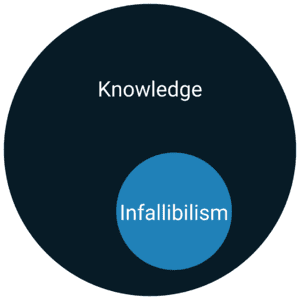

Infallibilism argues that for a belief to count as knowledge , it must be true and justified in such a way as to make it certain .

So, even though Smith has good reasons for his beliefs in the Gettier case , they’re not good enough to provide certainty . Certainty, to philosophers like Descartes, means the impossibility of doubt .

In the Gettier case, Smith might have misheard the interviewer say he was going to give Jones the job. Or, even more extreme, Smith might be a brain in a vat and Jones may not even exist! Either of these scenarios – however unlikely – raise the possibility of doubt.

Problem: too strict

So, infallibilism correctly says Smith’s belief in the Gettier case does not count as knowledge.

But it also says pretty much everything fails to qualify as knowledge!

“I know that water boils at 100 ° c” – can this be doubted? Of course it can! Your science teachers might have been lying to you, you might have misread your thermometer, you might be a brain in a vat and there’s no such thing as water!

So, whereas Gettier cases show the tripartite definition to set the bar too low for knowledge, infallibilism sets the bar way too high – barely anything can be known! In other words, we can argue that certainty is not a necessary condition of knowledge.

Knowledge from Perception>>>

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.3: The Concept of Knowledge

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 22243

- Jeffery L. Johnson

- Portland State University via Portland State University Library

So when a man gets hold of the true notion of something without an account, his mind does truly think of it, but he does not know it, for if he cannot give and receive an account of a thing, one has no knowledge of that thing. But when he has also got hold of an account, all this becomes possible to him and he is fully equipped with knowledge.

—PLATO1

Definitions and Word Games

Suppose that we are concerned with the question of economic justice—the fact that a few are ridiculously wealthy, while many are pitifully poor. We might convene an academic conference to discuss the issue and suggest some sort of coherent social policy. Economists might tell us about how income distribution is empirically related to national productivity. Political scientists might tell something about relative tax rates and the amount of government services. Sociologists could address the social effects of long-term poverty. Historians could give us some sense of whether the problem is better or worse than it was a hundred years ago. It would not be at all surprising if a philosopher contributed a paper on the meaning of economic justice. In one way, such a contribution seems necessary and foundational. After all, how can we reasonably construct some social policy aimed at greater economic justice if we are not crystal clear as to what we mean by this concept? In another light, however, the philosopher’s contribution seems frivolous and even counterproductive. If there is wide agreement that there is a problem that needs to be solved, the philosopher’s concern with long-dead thinkers such as Plato, Adam Smith, and Marx may strike us as an irresponsible waste of time and intellectual energy. To carry this example just a bit further, suppose the philosopher’s paper offers a definition of economic justice that suggests some kind of tension with other widely held values and social policies and goes so far as to suggest that we will never have a concept of economic justice that everyone will feel comfortable with. Now the philosopher’s concern with theory and the definition of terms may strike us as subversive. It may be difficult and controversial to articulate a theory about the nature of economic justice that everyone will agree with. Nevertheless, we know injustice when we see it. And to suggest that we spend our time defining terms and teasing out subtle philosophical arguments rather than offering constructive solutions to the obvious problems that plague our society is both dangerous and immoral. But all this is quite unfair. No sane philosopher is going to suggest that we spend all our time and energy in academic theoretical pursuits. Obviously, there are crises that call for immediate action, and we all recognize the need to make decisions on less than perfect information. But there is also a need for abstract theoretical work. It does seem crazy to propose significant social changes that will affect all of us without some kind of clear understanding of what we are trying to bring about. Pausing to reflect on the nature of economic justice—defining our terms, as they say—may be worthwhile even in a time of some urgency.

Please excuse the above digression. I have included it because I believe that many beginning students see much of traditional epistemology in the same uncharitable light that our philosopher was portrayed. Every reader of this book is a mature speaker of English. The verb to know and the abstract noun knowledge are fairly normal words within the English language. Obviously, we must know what they mean. We will discover, however, that it proves exceedingly difficult to articulate a clear and coherent definition, or theory, of knowledge.

The Myth of Definition

This chapter discusses the prospects for offering a helpful analysis, or definition, of the concept of knowledge. As a starting point, we need to take a little time dispelling a common misunderstanding about the importance of definition in everyday contexts, as well as philosophical contexts. It is widely believed that people do not know the meaning of the words they use—they do not know what they are talking about—unless they can provide adequate definitions for all those words. This is simply a mistaken view of meaning.

Someone can be an excellent athlete—a hitter in baseball, for example—yet be a very poor coach or teacher of how to hit. Surprisingly, perhaps, others can be mediocre hitters but turn into outstanding hitting coaches. The reason these things are possible is that there is all the difference in the world between doing something and describing, or explaining, how to do something. Think for a moment about those things that you are most skilled at doing—shooting free throws, playing a musical instrument, riding a bicycle, and so on. How confident would you be that you could teach someone else how to be skillful at these activities? Could you write a manual for them on how to do any one of these?

Speaking a language is much more like hitting a baseball than being a good hitting coach. Language is a skillful activity that human beings master with remarkable facility in ways that philosophers, psychologists, and linguists are only beginning to appreciate. I can safely assume that any reader of this book is an accomplished enough user of English that you know full well the meaning of almost every word that philosophers have spent a great deal of time and energy trying to analyze or define. You all know the meaning of terms such as beauty , justice , and knowledge because you can use sentences such as the following to communicate with other English speakers.

- 1. That’s a beautiful painting.

- 2. Simple justice demands that all the kids get to play.

- 3. You don’t really know that the Dodgers will win the pennant; you just hope they will.

All this is important because it is so easy to forget in the middle of philosophical battles. We are going to analyze the concept of knowledge in this chapter. We will see that this task is difficult, controversial, and perhaps in the end, impossible to complete satisfactorily. This doesn’t mean for a second that you or the great minds of Western philosophy do not know how to use words such as know and knowledge for the purposes of clear communication.

The Need for Conceptual Clarity

Although I stand 100 percent behind what I said previously, this doesn’t mean that careful conceptual analysis is not important. People sometimes make remarkable claims about knowledge. We have just seen how the skeptic can put together plausible and disturbing arguments that we know next to nothing. The arguments of the last chapter are classical examples of the sorts of intellectual concerns that occupy the attention of professional philosophers. Disputes about knowledge are not limited to philosophers, however. We often hear that modern scientists do not know that evolution by natural selection is true. Many claim that it is only a “theory.” This is sometimes backed up with an argument. Science, so this line of thinking goes, is only concerned with what can be directly observed or proved with laboratory experiments. But evolution, it is sometimes claimed, cannot be directly observed, both because it is too slow of a process and because the most interesting observations would have needed to take place in a time before there were human observers. Furthermore, creationists claim that no controlled laboratory experiment can prove that evolution is true.

If we are to make any progress in understanding, let alone resolving, these kinds of intellectual disputes, we are going to need to be much clearer in our own minds as to what counts as knowledge. I claim to know that I am at my computer composing this chapter. The skeptic tells me I don’t know this after all; it might only be a dream. I am quite sure that I know that natural selection is true. Creationists claim that I don’t and that my “faith” in the theory is no different from religious belief. How can we possibly hope to make progress toward resolving these disputes without some fairly specific agreement as to what counts as genuine knowledge?

For some, the kind of conceptual analysis in which we engage in this chapter can be fun and exciting in its own right. Most of you, however, should see it as a necessary means to an end. I assume most of you care about whether scientists know what they are talking about. If you are like I am, you think they probably do. But to really feel confident about this, you need to have some answers to the philosophical skeptic who says it might all be a dream and the procedural skeptic who argues from a specific model of scientific knowledge to doubt about things such as evolution and climate change. To answer either of these skeptics productively, you need some agreement about the nature of knowledge.

Knowledge and Belief

Human beings seem to be a very credulous species; we believe an amazing variety of things. Our ancestors believed in witches, that the earth was flat, and in the divine right of kings. People today believe that their futures are foretold in horoscopes, that good writing can be accomplished in first drafts, and that their favorite sports team will finally get it together. From the perspective of history, it is easy to find countless beliefs that we sincerely held that strike us as foolish, dangerous, and immoral. But of course, not all beliefs fit into this category.

Other things we don’t merely believe, we know. I, of course, believe that I am a philosophy professor, a one-time softball player, and a husband to a beautiful woman. But I don’t just believe these things, I know them. The distinction between belief and knowledge is not like the one between being a sibling and being an only child—it is not an exclusive, either/or difference. It is rather like the distinction between an automobile and a convertible. To be a convertible is to be a special kind of automobile. As logicians put it, being an automobile is a necessary condition of being a convertible. Not all automobiles are convertibles, but all convertibles are automobiles.

Traditional models, or definitions, of knowledge have attempted to articulate a list of necessary conditions that are jointly sufficient for having genuine knowledge. The abstract noun knowledge is kind of artificial. I think we will do better to use the more familiar verb. Our observations about knowing and believing suggest the first entry on our list of necessary conditions:

There is a fairly common way of talking that seems to call this into question. Suppose we have a friend who is headed for heartache partly because he refuses to take seriously the obvious evidence of his lover’s infidelity. We might say, “Jake knows that she’s untrue, but he can’t bring himself to believe it.” Or perhaps we have a colleague who is foolishly refusing to take heed of medical symptoms: “Sarah knows something is wrong but just won’t believe it.” How seriously should we take the claim that both Jake and Sarah have knowledge but lack belief? Not very.

Jake sees the obvious signs and has his moments of doubt. Sarah too. If they didn’t, we wouldn’t be inclined to say they knew. It is, of course, possible for people to be perversely dense. People can be totally oblivious to things that are perfectly obvious to others. Connie may genuinely believe that her lover is totally faithful despite the lame excuses and the lipstick on his collar. But we would never be tempted to say Connie knows this, though perhaps she should. When we use the “knows but doesn’t believe” idiom, we are getting at something interesting about Jake and Sarah. They seem to be engaging in what philosophers call self-deception. This is an important issue in both philosophy and psychology but really says nothing about how to define knowledge.

I take it to be settled that knowledge implies some kind of genuine conviction or intellectual confidence. Thus the first necessary condition of knowledge turns out to be relatively secure, uncontroversial, and philosophically straightforward. Would that we could say the same about the conditions to follow.

The Search for the Truth

You are the district attorney, and you’ve got a great case. The defendant is the kind of lowlife that society needs to do something about. You’ve got the goods on him too, lots of physical evidence, a clear motive, and witnesses. The case will be an easy one to try, and it will be a feather in your cap to be the one who put him away. You just “know” that the slime ball’s guilty. There’s only one problem with this scenario; the guy didn’t do it. It does not matter how sincere your belief is nor how good the evidence seems to be—if what you thought you knew turns out to be false, it’s back to the drawing board. Truth is an absolute precondition for knowledge. Unfortunately, truth is a philosophical mess.

Contemporary philosophy is about as far from consensus about the nature of truth as any issue in the field. Some believe that truth is correspondence with reality. Others believe that it is coherence with other widely held beliefs. Yet others claim that the assertion that “snow is white is true” is just a fancy way of saying that “snow is white.” All these theories of truth have plausible arguments in their defense, and all suffer from serious conceptual problems. Professional philosophy doesn’t know what truth is. I don’t know what it is either, but I will nevertheless say a little more about truth toward the end of this book.

In spite of all the confusion about the nature of truth, however, the relationship between truth and knowledge is as clear as could be. The only beliefs that we have that are viable candidates for being knowledge are those that are true. The surest way to defeat someone’s claim that they know something is to show that what they claim to know is false. This suggests a work-around epistemological definition of truth:

Admittedly, this is a pretty trivial definition. It does, however, have the advantage of separating philosophical disputes about the nature of truth from the noncontroversial connection between truth and knowledge.

Thus truth supplies a second necessary condition for knowledge. We can expand our evolving model of knowledge as follows:

Epistemic Justification

Perhaps we already have all that we need. The concept of knowledge seems both subjective and objective. To believe something is to be in a certain cognitive state that individual “subjects” find themselves in or fail to find themselves in. For that belief to be true (or not-false) it must be dependent on things entirely independent of those subjects—the way things “objectively” are. Condition i takes care of the subjective element, and ii covers the objective. What more do we need?

I have been hoping for a raise. Unfortunately, my latest evaluation left a lot to be desired, and the state’s budget looks pretty bleak. Forever the optimist, I continue to think the best. I woke up yesterday and as I was having my morning coffee I glanced at my horoscope. The entry for Pisces was way cool: “You will receive something long overdue and well deserved. All the signs are positive.” My raise! What could be clearer? I went to work with a smile on my face absolutely confident that I would get the good news. And I did! The governor decided that all state employees should get a modest salary adjustment, and that afternoon, we were all formally notified.

The two conditions for knowledge are satisfied. Johnson believes that he will get a raise, and it is true that he will get a raise. Does he therefore know that he will get a raise? Most of us would be very reluctant to say he possesses knowledge. What he believes turns out to be true but merely by coincidence or good luck. The subjective element of belief and the objective element of truth seem much too tenuously connected. What seems to be missing is some reason or evidence in support of my belief. Sure, the horoscope is a reason in the sense of providing a psychological explanation for why I happen to have this belief. But it’s such a poor reason—it’s so unreliable—that we attribute the belief’s truth to good fortune and not the strength of the reason.

Epistemologists have adopted the idiom of normative obligation to get at the stronger connection between belief and truth that is required for genuine knowledge. You are entitled to claim knowledge, according to this way of thinking about things, only if your belief is justified —that is, just in case you have very good reason for thinking it is true. Thus on the so-called standard analysis of knowledge a third necessary condition of knowledge, one that completes the package and makes it jointly sufficient, is the justification condition.

What Does It Take to Be Justified?

We have seen how skeptics can produce a formidable battery of arguments designed to show that we are never completely justified in believing anything. The problem concerns the connection between truth and justification. The only standard that completely eliminates the possibility of our beliefs being held in error is one of self-evidence or certainty. But as the Cartesian project has convinced most of us, epistemological certainty is unattainable. This means that whatever model of knowledge is finally endorsed will be committed to some sort of epistemic fallibility. This is not that serious a worry for most natural or social scientists but does run counter to the dominant tradition in Western epistemology.

Self-evidence and certainty may have set unrealistically high standards for knowledge, but these epistemic standards had the superficial appearance of being clear and identifiable. Models of knowledge that substitute criteria for epistemic justification must be prepared to state some new criterion for distinguishing unfounded belief from a promising theory and from established knowledge. The contemporary literature offers many intriguing possibilities—some highly formal and some quite commonsensical—but none that have won anything approaching consensus.

I suggest that we understand the idea of epistemic justification in terms of evidence. The things that we know are those true beliefs for which we have very, very, very good evidence—what a lawyer calls proof beyond a reasonable doubt. Good evidence is something that we are all familiar with and something that we can learn to reliably spot. I will be offering in the chapters to follow a model of—or a kind of formula for testing for—good evidence. I hope to convince you that this model captures almost everything we care about when we assess the quality of a person’s evidence or for that matter, their claims to knowledge.

Let’s transform the standard analysis of knowledge in light of all this into the following:

An Unsolved Problem

If you were reading very carefully, you may have noticed a slight difference in the way I stated the standard analysis of knowledge at the end of preceding section and the section immediately before that one. You are all smart enough to see the obvious change in condition iii , but can you find the other difference? The way the philosophic tradition has defined knowledge is to articulate necessary and sufficient conditions for knowing something. The standard analysis of knowledge claims that the three necessary conditions are, taken together, sufficient for knowing something. In my statement of a “transformed” analysis, I wimped out a bit. I claimed that my three conditions were all necessary—that’s what the “only if” signifies—but I left it open whether the three conditions were sufficient. Here’s why.

Consider the following little thought experiment. My wife and I have spent the last hour collaborating on our special spaghetti sauce. Just as we are getting ready to serve dinner, we discover that we are out of Parmesan cheese. We divide responsibilities—she will toss the salad and serve dinner; I’ll make the emergency run to the store. While at the store, I meet a colleague doing research in contemporary epistemology—she wants an example of knowledge. I suggest that I know there is a spaghetti dinner sitting on our dining room table right now. And as luck would have it, it’s true that a spaghetti dinner is on the table. I believe it, it’s true, and I’m justified in believing it. All is well. Well, maybe not. After I left, our German shepherd, Guido, got rambunctious and knocked the pot of simmering spaghetti sauce on the dirty kitchen floor. My wife considered violence against the dog, but before anything could happen, a neighbor arrived with a pot of leftover spaghetti sauce, announcing that she was leaving on vacation and it would surely spoil before she returned. Thus the spaghetti sauce that made my knowledge claim true is unconnected to the spaghetti sauce that provided the justification for my belief. It is odd in the extreme to claim that I had knowledge of the pot of spaghetti sitting on my table. It is pure serendipity that my belief turned out to be true.

A lot of contemporary epistemology has been concerned with ruling out these kinds of “Guido” cases (actually, they are called Gettier examples, after the philosopher who first made them famous). Many philosophers have suggested that some fourth or fifth or sixth and so on condition must be added to our analysis of knowledge. I am not sure whether I personally agree. To be on the safe side, however, I will be content with the above transformed analysis. The epistemic action in this little book will focus on condition iii anyway. What the heck is it to have evidence or good evidence or exceedingly good evidence for something?

- 1. What is the myth of definition? Does it show that the traditional philosophical quest of defining terms (analyzing them) is unnecessary? Why, or why not?

- 2. Explain why having a true belief that something is the case is not good enough for claiming to know that it is the case.

- 3. What does the “Guido” example show us about knowledge?

Here’s something I claim to know: climate change (global warming) is very real and very dangerous. How would the epistemological skeptic respond to this? Given the view of knowledge defended in this chapter, what would need to be true if my knowledge claim is correct?

1. Plato, “Theatetus,” in Plato: The Collected Dialogues , trans. F. M. Cornford (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1961), 909.

- September 22, 2011

The Knowledge Problem

Studying knowledge is one of those perennial topics—like the nature of matter in the hard sciences—that philosophy has been refining since before the time of Plato. The discipline, epistemology, comes from two Greek words episteme (επιστημη) which means knowledge and logos (λογος) which means a word or reason. Epistemology literally means to reason about knowledge. Epistemologists study what makes up knowledge, what kinds of things can we know, what are the limits to what we can know, and even if it’s possible to actually know anything at all.

Coming up with a definition of knowledge has proven difficult but we’ll take a look at a few attempts and examine the challenges we face in doing so. We’ll look at how prominent philosophers have wrestled with the topic and how postmodernists provide a different viewpoint on the problem of knowledge. We’ll also survey some modern work being done in psychology and philosophy that can help us understand the practical problems with navigating the enormous amounts of information we have at our disposal and how we can avoid problems in the way we come to know things.

Do We Know Stuff?

In order to answer that question, you probably have to have some idea what the term “know” means. If I asked, “Have you seen the flibbertijibbet at the fair today?” I’d guess you wouldn’t know how to answer. You’d probably start by asking me what a flibbertijibbet is. But most adults tend not to ask what knowledge is before they can evaluate whether they have it or not. We just claim to know stuff and most of us, I suspect, are pretty comfortable with that. There are lots of reasons for this but the most likely is that we have picked up a definition over time and have a general sense of what the term means. Many of us would probably say knowledge that something is true involves:

- Certainty – it’s hard if not impossible to deny

- Evidence – it has to based on something

- Practicality – it has to actually work in the real world

- Broad agreement – lots of people have to agree it’s true

But if you think about it, each of these has problems. For example, what would you claim to know that you would also say you are certain of? Let’s suppose you’re not intoxicated, high, or in some other way in your “right” mind and conclude that you know you’re reading an article on the internet. You might go further and claim that denying it would be crazy. Isn’t it at least possible that you’re dreaming or that you’re in something like the Matrix and everything you see is an illusion? Before you say such a thing is absurd and only those who were unable to make the varsity football team would even consider such questions, can you be sure you’re not being tricked? After all, if you are in the Matrix, the robots that created the Matrix would making be making you believe you are not in the Matrix and that you’re certain you aren’t.

What about the “broad agreement” criterion? The problem with this one is that many things we might claim to know are not, and could not be, broadly agreed upon. Suppose you are experiencing a pain in your arm. The pain is very strong and intense. You might tell your doctor that you know you’re in pain. Unfortunately though, only you can claim to know that (and as an added problem, you don’t appear to have any evidence for it either—you just feel the pain). So at least on the surface, it seems you know things that don’t have broad agreement by others.

These problems and many others are what intrigue philosophers and are what make coming up with a definition of knowledge challenging. Since it’s hard to nail down a definition, it also makes it hard to answer the question “what do you know?”

What is Knowledge?

As with many topics in philosophy, a broadly-agreed-upon definition is difficult. But philosophers have been attempting to construct one for centuries. Over the years, a trend has developed in the philosophical literature and a definition has emerged that has such wide agreement it has come to be known as the “standard definition.” While agreement with the definition isn’t universal, it can serve as a solid starting point for studying knowledge.

The definition involves three conditions and philosophers say that when a person meets these three conditions, she can say she knows something to be true. Take a statement of fact: The Seattle Mariners have never won a world series.  On the standard definition, a person knows this fact if:

- The person believes the statement to be true

- The statement is in fact true

- The person is justified in believing the statement to be true

The bolded terms earmark the three conditions that must be met and because of those terms, the definition is also called the “tripartite” (three part) definition or “JTB” for short. Many many books have been written on each of the three terms so I can only briefly summarize here what is going on in each. I will say up front though that epistemologists spend most of their time on the third condition.

First, beliefs are things people have. Beliefs aren’t like rocks or rowboats where you come across them while strolling along the beach. They’re in your head and generally are viewed as just the way you hold the world (or some aspect of the world) to be. If you believe that the Mariners never won a world series, you just accept it is as true that the Mariners really never won a world series. Notice that accepting that something is true implies that what you accept could be wrong. In other words, it implies that what you think about the world may not match up with the way the world really is. This implies that there is a distinction between belief and truth . There are some philosophers—notably postmodernists and existentialists—who think such a distinction can’t be made which we’ll examine more below. But in general, philosophers claim that belief is in our heads and truth is about the way the world is. In practical terms, you can generally figure out what you or someone else believes by examining behavior. People will generally act according to what they really believe rather than what they say they believe—despite what Dylan says .

Something is true if the world really is that way. Truth is not in your head but is “out there.” The statement, “The Mariners have never won a world series” is true if the Mariners have never won a world series. The first part of that sentence is in quotes on purpose. The phrase in quotes signifies a statement we might make about the world and the second, unquoted phrase is supposed to describe the way the world actually is. The reason philosophers write truth statements this way is to give sense to the idea that a statement about the world could be wrong or, more accurately, false (philosophers refer to the part in quotes as a statement or proposition ). Perhaps you can now see why beliefs are different than truth statements. When you believe something, you hold that or accept that a statement or proposition is true. It could be false that’s why your belief may not “match up” with the way the world really is. For more on what truth is, see the Philosophy News article, “ What is Truth? ”

Justification

If the seed of knowledge is belief, what turns belief into knowledge? This is where justification (sometimes called ‘warrant’) comes in. A person knows something if they’re justified in believing it to be true (and, of course, it actually is true). There are dozens of competing theories of justification. It’s sometimes easier to describe when a belief isn’t justified than when it is. In general, philosophers agree that a person isn’t justified if their belief is:

- a product of wishful thinking (I really wish you would love me so I believe you love me)

- a product of fear or guilt (you’re terrified of death and so form the belief in an afterlife)

- formed in the wrong way (you travel to an area you know nothing about, see a white spot 500 yards away and conclude it’s a sheep)

- a product of dumb luck or guesswork (you randomly form the belief that the next person you meet will have hazel eyes and it turns out that the next person you meet has hazel eyes)

Because beliefs come in all shapes and sizes and it’s hard to find a single theory of justification that can account for everything we would want to claim to know. You might be justified in believing that the sun is roughly 93 million miles from the earth much differently than you would be justified in believing God exists or that you have a minor back pain. Even so, justification is a critical element in any theory of knowledge and is the focus of many a philosophical thought.

People-centered Knowledge

You might notice that the description above puts the focus of knowing on the individual. Philosophers talk of individual persons being justified and not the ideas or concepts themselves being justified. This means that what may count as knowledge for you may not count as knowledge for me. Suppose you study economics and you learn principles in the field to some depth. Based on what you learn, you come to believe that psychological attitudes have just as much of a role to play in economic flourishing or deprivation as the political environment that creates economic policy. Suppose also that I have not studied economics all that much but I do know that I’d like more money in my pocket. You and I may have very different beliefs about economics and our beliefs might be justified in very different ways. What you know may not be something I know even though we have the same evidence and arguments in front of us.

So the subjective nature of knowledge partly is based on the idea that beliefs are things that individuals have and those beliefs are justified or not justified. When you think about it, that makes sense. You may have more evidence or different experiences than I have and so you may believe things I don’t or may have evidence for something that I don’t have. The bottom line is that “universal knowledge” – something everybody knows—may be very hard to come by. Truth, if it exists, isn’t like this. Truth is universal. It’s our access to it that may differ widely.

Rene Descartes and the Search for Universal Knowledge

A lot of people are uncomfortable with the idea that there isn’t universal knowledge. Philosopher Rene Descartes (pronounced day-cart) was one of them. When he was a young man, he was taught a bunch of stuff by his parents, teachers, priests and other authorities. As he came of age, he, like many of us, started to discover that much of what he was taught either was false or was highly questionable. At the very least, he found he couldn’t have the certainty that many of his educators had. While many of us get that, deal with it, and move on, Descartes was deeply troubled by this.

One day, he decided to tackle the problem. He hid himself away in a cabin and attempted to doubt everything of which he could not be certain. Since it wasn’t practical to doubt every belief he had, Descartes decided that it would be sufficient to subject the foundations of his belief system to doubt and the rest of the structure will “crumble of its own accord.” He first considers the things he came to believe by way of the five senses. For most of us these are pretty stable items but Descartes found that it was rather easy to doubt their truth. The biggest problem is that sometimes the senses can be deceptive. And after all, could he be certain he wasn’t insane or dreaming when he saw that book or tasted that honey? So while they might be fairly reliable, the senses don’t provide us with certainty—which is what Descartes was after.

Unfortunately, this left Descartes with no where to turn. He found that he could be skeptical about everything and was unable to find a certain foundation for knowledge. But then he hit upon something that changed modern epistemology. He discovered that there was one thing he couldn’t doubt: the fact that he was a thinking thing. In order to doubt it, he would have to think. He reasoned that it’s not possible to doubt something without thinking about the fact that you’re doubting. If he was thinking then he must be a thinking thing and so he found that it was impossible to doubt that he was a thinking being.

This seemingly small but significant truth led to his most famous contribution to Western thought: cogito ergo sum (I think, therefore I am). Some mistakenly think that Descartes was implying with this idea that he thinks himself into existence. But that wasn’t his point at all. He was making a claim about knowledge. Really what Descartes was saying is: I think, therefore I know that I am.

The story doesn’t end here for Descartes but for the rest of it, I refer you to the reading list below to dig deeper. The story of Descartes is meant to illustrate the depth of the problems of epistemology and how difficult and rare certainty is, if certainty is possible—there are plenty of philosophers who think either that Descartes’ project failed or that he created a whole new set of problems that are even more intractable than the one he set out to solve.

Postmodernism and Knowledge

Postmodern epistemology is a growing area of study and is relatively new on the scene compared with definitions that have come out of the analytic tradition in philosophy. Generally, though, it means taking a specific, skeptical attitude towards certainty, and a subjective view of belief and knowledge. Postmodernists see truth as much more fluid than classical (or modernist) epistemologists. Using the terms we learned above, they reject the idea that we can ever be fully justified in holding that our beliefs line up with the way the world actually is. We can’t know that we know.

Perspective at the Center

In order to have certainty, postmodernists claim, we would need to be able to “stand outside” our own beliefs and look at our beliefs and the world without any mental lenses or perspective . It’s similar to wondering what it would be like to watch ourselves meeting someone for the first time? We can’t do it. We can watch the event of the meeting on a video but the experience of meeting can only be had by us. We have that experience only from “inside” our minds and bodies. Since its not possible to stand outside our minds, all the parts that make up our minds influence our view on what is true. Our intellectual and social background, our biases, our moods, our genetics, other beliefs we have, our likes and dislikes, our passions (we can put all these under the label of our “cognitive structure”) all influence how we perceive what is true about the world. Further, say the postmodernists, it’s not possible to set aside these influences or lenses. We can reduce the intensity here and there and come to recognize biases and adjust for them for sure. But it’s not possible to completely shed all our lenses which color our view of things and so it’s not possible to be certain that we’re getting at some truth “out there.”

Many have called out what seems to be a problem with the postmodernist approach. Notice that as soon as a postmodernist makes a claim about the truth and knowledge they seem to be making a truth statement! If all beliefs are seen through a lens, how do we know the postmodernists beliefs are “correct?” That’s a good question and the postmodernist might respond by saying, “We don’t!” But then, why believe it? Because of this obvious problem, many postmodernists attempt to simply live with postmodernist “attitudes” towards epistemology and avoid saying that they’re making claims that would fit into traditional categories. We have to change our perspective to understand the claims.

Community Agreement

To be sure, Postmodernists do tend to act like the rest of us when it comes to interacting with the world. They drive cars, fly in airplanes, make computer programs, and write books. But how is this possible if they take such a fluid view of knowledge? Postmodernists don’t eschew truth in general. They reject the idea that any one person’s beliefs about it can be certain. Rather, they claim that truth emerges through community agreement. Suppose scientists are attempting to determine whether the planet is warming and that humans are the cause. This is a complex question and a postmodernist might say that if the majority of scientists agree that the earth is warming and that humans are the cause, then that’s true. Notice that the criteria for “truth” is that scientists agree . To use the taxonomy above, this would be the “justification condition.” So we might say that postmodernists accept the first and third conditions of the tripartite view but reject the second condition: the idea that there is a truth that beliefs need to align to a truth outside our minds.

When you think about it, a lot of what we would call “facts” are determined in just this way. For many years, scientists believed in a substance called “phlogiston.” Phlogiston was stuff that existed in certain substances (like wood and metal) and when those substances were burned, more phlogiston was added to the substance. Phlogiston was believed to have negative weight, that’s why things got lighter when they burned. That theory has since been rejected and replace by more sophisticated views involving oxygen and oxidation.

So, was the phlogiston theory true? The modernist would claim it wasn’t because it has since been shown to be false. It’s false now and was false then even though scientists believed it was true. Beliefs about phlogiston didn’t line up with the way the world really is, so it was false. But the postmodernist might say that phlogiston theory was true for the scientists that believed it. We now have other theories that are true. But phlogiston theory was no less true then than oxygen theory is now. Further, they might add, how do we know that oxygen theory is really the truth ? Oxygen theory might be supplanted some day as well but that doesn’t make it any less true today.

Knowledge and the Mental Life

As you might expect, philosophers are not the only ones interested in how knowledge works. Psychologists, social scientists, cognitive scientists and neuroscientists have been interested in this topic as well and, with the growth of the field of artificial intelligence, even computer scientists have gotten into the game. In this section, we’ll look at how work being done in psychology and behavioral science can inform our understanding of how human knowing works.

Thus far, we’ve looked at the structure of knowledge once beliefs are formed. Many thinkers are interested how belief formation itself is involved our perception of what we think we know. Put another way, we may form a belief that something is true but the way our minds formed that belief has a big impact on why we think we know it. The science is uncovering that, in many cases, the process of forming the belief went wrong somewhere and our minds have actually tricked us into believing its true. These mental tricks may be based on good evolutionary principles: they are (or at least were at some point in our past) conducive to survival. But we may not be aware of this trickery and be entirely convinced that we formed the belief in the right way and so have knowledge. The broad term used for this phenomenon is “cognitive bias” and mental biases have a significant influence over how we form beliefs and our perception of the beliefs we form. 1

Wired for Bias

A cognitive bias is a typically unconscious “mental trick” our minds play that lead us to form beliefs that may be false or that are directed towards some facts and leaving out others such that these beliefs align to other things we believe, promote mental safety, or provide grounds for justifying sticking to to a set of goals that we want to achieve. Put more simply, mental biases cause us to form false beliefs about ourselves and the world. The fact that our minds do this is not necessarily intentional or malevolent and, in many cases, the outcomes of these false beliefs can be positive for the person that holds them. But epistemologists (and ethicists) argue that ends don’t always justify the means when it comes to belief formation. As a general rule, we want to form true beliefs in the “right” way.

Ernest Becker in his important Pulitzer Prize winning book The Denial of Death attempts to get at the psychology behind why we form the beliefs we do. He also explores why we may be closed off to alternative viewpoints and why we tend to become apologists (defenders) of the viewpoints we hold. One of his arguments is that we as humans build an ego ( in the Freudian sense; what he calls “character armor”) out of the beliefs we hold and those beliefs tend to give us meaning and they are strengthened when more people hold the same viewpoint. In a particularly searing passage, he writes:

Each person thinks that he has the formula for triumphing over life’s limitations and knows with authority what it means to be a man [N.B. by ‘man’ Becker means ‘human’ and uses masculine pronouns as that was common practice when he wrote the book], and he usually tries to win a following for his particular patent. Today we know that people try so hard to win converts for their point of view because it is more than merely an outlook on life: it is an immortality formula. . . in matters of immortality everyone has the same self-righteous conviction. The thing seems perverse because each diametrically opposed view is put forth with the same maddening certainty; and authorities who are equally unimpeachable hold opposite views! (Becker, Ernest. The Denial of Death, pp. 255-256. Free Press.)

In other words, being convinced that our viewpoint is correct and winning converts to that viewpoint is how we establish ourselves as persons of meaning and significance and this inclination is deeply engrained in our psychological equipment. This not only is why biases are so prevalent but why they’re difficult to detect. We are, argues Becker and others, wired towards bias. Jonathan Haidt agrees and go so far as to say that reason and logic is not only the cure but a core part of the wiring that causes the phenomenon.

Anyone who values truth should stop worshipping reason. We all need to take a cold hard look at the evidence and see reasoning for what it is. The French cognitive scientists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber recently reviewed the vast research literature on motivated reasoning (in social psychology) and on the biases and errors of reasoning (in cognitive psychology). They concluded that most of the bizarre and depressing research findings make perfect sense once you see reasoning as having evolved not to help us find truth but to help us engage in arguments, persuasion, and manipulation in the context of discussions with other people. (Haidt, Jonathan. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion (p. 104). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.)

Biases and Belief Formation

Research in social science and psychology are uncovering myriad ways in which our minds play these mental tricks. For example, Daniel Kahneman discusses the impact emotional priming has on the formation of a subsequent idea. In one study, when participants were asked about happiness as it related to their romantic experiences, those that had a lot of dates in the past would report that they were happy about their life while those that had no dates reported being lonely, isolated, and rejected. But then when they subsequently were asked about their happiness in general, they imposed the context of their dating happiness to their happiness in general regardless of how good or bad the rest of their lives seemed to be going. If a person would have rated their overall happiness as “very happy” when asked questions about general happiness only, they might rate their overall happiness as “somewhat happy” if they were asked questions about their romantic happiness just prior and their romantic happiness was more negative than positive.

This type of priming can significantly impact how we view what is true. Being asked if we need more gun control or whether we should regulate fatty foods will change right after a local shooting right or after someone suffers a heart scare. The same situation will have two different responses by the same person depending on whether he or she was primed or not. Jonathan Haidt relates similar examples.

Psychologists now have file cabinets full of findings on ‘motivated reasoning,’ showing the many tricks people use to reach the conclusions they want to reach. When subjects are told that an intelligence test gave them a low score, they choose to read articles criticizing (rather than supporting) the validity of IQ tests. When people read a (fictitious) scientific study that reports a link between caffeine consumption and breast cancer, women who are heavy coffee drinkers find more flaws in the study than do men and less caffeinated women. (Haidt, p. 98)

There are many other biases that influence our thinking. When we ask the question, “what is knowledge?” this research has to be a part of how we answer the question. Biases and their influence would fall under the broad category of the justification condition we looked at earlier and the research should inform how we view how beliefs are justified. Justification is not merely the application of a philosophical formula. There are a host of psychological and social influences that are play when we seek to justify a belief and turn it into knowledge. 2 We can also see how this research lends credence to the philosophical position of postmodernists. At the very least, even if we hold that we can get past our biases and get “more nearer to the truth,” we at least have good reason to be careful about the things we assert as true and adopt a tentative stance towards the truth of our beliefs.

In a day when “fake news” is a big concern and the amount of information for which we’re responsible grows each day, how we justify the beliefs we hold becomes a even more important enterprise. I’ll use a final quote from Haidt to conclude this section:

And now that we all have access to search engines on our cell phones, we can call up a team of supportive scientists for almost any conclusion twenty-four hours a day. Whatever you want to believe about the causes of global warming or whether a fetus can feel pain, just Google your belief. You’ll find partisan websites summarizing and sometimes distorting relevant scientific studies. Science is a smorgasbord, and Google will guide you to the study that’s right for you. (Haidt, pp. 99-100)

Making Knowledge Practical

Well most of us aren’t like Descartes. We actually have lives and don’t want to spend time trying to figure out if we’re the cruel joke of some clandestine mad scientist. But we actually do actually care about this topic whether we “know” it or not. A bit of reflection exposes just how important having a solid view of knowledge actually is and spending some focused time thinking more deeply about knowledge can actually help us get better at knowing.

Really, knowledge is a the root of many (dare I say most) challenges we face in a given day. Once you get past basic survival (though even things as basic as finding enough food and shelter involves challenges related to knowledge), we’re confronted with knowledge issues on almost every front. Knowledge questions range from larger, more weighty questions like figuring out who our real friends are, what to do with our career, or how to spend our time, what politician to vote for, how to spend or invest our money, or should we be religious or not, to more mundane ones like which gear to buy for our hobby, how to solve a dispute between the kids, where to go for dinner, or which book to read in your free time. We make knowledge decisions all day, every day and some of those decisions deeply impact our lives and the lives of those around us.

So all these decisions we make about factors that effect the way we and others live are grounded in our view of knowledge—our epistemology . Unfortunately few spend enough time thinking about the root of their decisions and many make knowledge choices based on how they were raised (my mom always voted Republican so I will), what’s easiest (if I don’t believe in God, I’ll be shunned by my friends and family), or just good, old fashioned laziness. But of all the things to spend time on, it seems thinking about how we come to know things should be at the top of the list given the central role it plays in just about everything we do.

Updated January, 2018: Removed dated material and general clean up; added section on cognitive biases. Updated March, 2014: Removed reference to dated events; removed section on thought experiment; added section on Postmodernism; minor formatting changes

- While many thinkers have written on cognitive biases in one form or another, Jonathan Haidt in his book The Righteous Mind and Daniel Kahneman in his book Thinking Fast and Slow have done seminal work to systemize and provide hard data around how the mind operates when it comes to belief formation and biases. There is much more work to be done for sure but these books, part philosophy, part psychology, part social science, provide the foundation for further study in this area. The field of study already is large and growing so I can only provide a thumbnail sketch of the influence of how belief formation is influenced by our mind and other factors. I refer the reader to the source material on this topic for further study (see reading list below). ↩

- For a strategy on how we can adjust for these natural biases that our minds seem wired to create, see the Philosophy News article, “ How to Argue With People ”. I also recommend Carol Dweck’s excellent book Mindset . ↩

For Further Reading

- Epistemology: Classic Problems and Contemporary Responses (Elements of Philosophy) by Laurence BonJour. One of the better introductions to the theory of knowledge. Written at the college level, this book should be accessible for most readers but have a good philosophical dictionary on hand.

- Belief, Justification, and Knowledge: An Introduction to Epistemology (Wadsworth Basic Issues in Philosophy Series) by Robert Audi. This book has been used as a text book in college courses on epistemology so may be a bit out of range for the general reader. However, it gives a good overview of many of the issues in the theory of knowledge and is a fine primer for anyone interested in the subject.

- The Theory of Knowledge: Classic and Contemporary Readings by Louis Pojman. Still one of the best books for primary source material. The edited articles have helpful introductions and Pojman covers a range of sources so the reader will get a good overview from many sides of the question. Written mainly as a textbook.

- The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window into Human Nature   by Steven Pinker. While not strictly a book about knowledge per se, Pinker’s book is fun, accessible, and a good resource for getting an overview of some contemporary work being done mainly in the hard sciences.

- The Selections From the Principles of Philosophy by René Descartes . A good place to start to hear from Descartes himself.

- Descartes’ Bones: A Skeletal History of the Conflict between Faith and Reason by Russell Shorto. This book is written as a history so it’s not strictly a philosophy tome. However, it gives the general reader some insight into what Descartes and his contemporaries were dealing with and is a fun read.

- On Bullshit by Harry Frankfurt. One get’s the sense that Frankfurt was being a bit tongue-in-cheek with the small, engaging tract. It’s more of a commentary on the social aspect of epistemology and worth reading for that reason alone. Makes a great gift!

- On Truth by Harry Frankfurt. Like On Bullshit but on truth.

- A Rulebook for Arguments by Anthony Weston. A handy reference for constructing logical arguments. This is a fine little book to have on your shelf regardless of what you do for a living.

- Warrant: The Current Debate   by Alvin Plantinga. Now over 25 years old, “current” in the title may seem anachronistic. Still, many of the issues Plantinga deals with are with us today and his narrative is sure to enlighten and prime the pump for further study.

- Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman. The book to begin a study on cognitive biases.

- The Righteous Mind by Jonathan Haidt. A solid book that dabbles in cognitive biases but also in why people form and hold beliefs and how to start a conversation about them.

- The Denial of Death by Ernest Becker. A neo (or is it post?) Freudian analysis of why we do what we do. Essential reading for better understanding why we form the beliefs we do.

- Mindset: The New Psychology of Success by Carol S. Dweck. The title reads like a self-help book but the content is actually solid and helpful for developing an approach to forming and sharing ideas.

More articles

What is Disagreement? – Part IV

This is Part 4 of a 4-part series on the academic, and specifically philosophical study of disagreement. In Part 1...

What is Disagreement? – Part III

This is Part 3 of a 4-part series on the academic, and specifically philosophical study of disagreement. In Part 1...

What is Disagreement? – Part II

This is Part 2 of a 4-part series on the academic, and specifically philosophical study of disagreement. In Part 1...

What is Disagreement?

This is Part 1 of a 4-part series on the academic, and specifically philosophical study of disagreement. In this series...

Rejecting the Anthropocene is a mistake

In the second of our two-part series, we go head-to-head on the Anthropocene, after the status of ‘Anthropocene’ was rejected...

East of Appomattox: Where Old Times Are Still Not Forgotten

One of the great joys of Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee is that when I am out hiking...

Forgiveness, Obligation, and Cultures of Domination: A Review of Myisha Cherry’s Failures of Forgiveness

Myisha Cherry has entitled her recent book Failures of Forgiveness: What We Get Wrong and How to Do Better. The...

philosophybits: “At one and the same time we must philosophize, laugh, and manage our household and…

philosophybits: “At one and the same time we must philosophize, laugh, and manage our household and other business, while never...

1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Philosophy, One Thousand Words at a Time

Epistemology, or Theory of Knowledge

Thomas Metcalf Category: Epistemology Word count: 999

Listen here

Many people think that they have a lot of knowledge. They also believe that other people sometimes know what they claim to know. But what is knowledge anyway? And how do we come to have it? Is it important that we have knowledge? If so, why?

The branch of philosophy that attempts to answer these and related questions is known as ‘epistemology’ or ‘theory of knowledge.’ [1]

1. What is Knowledge? [2]

One historically popular definition of ‘knowledge’ is the ‘JTB’ theory of knowledge: knowledge is j ustified, t rue b elief. [3] Most philosophers think that a belief must be true in order to count as knowledge. [4] Suppose that Smith is framed for a crime, and the evidence against Smith is overwhelming. But Smith is innocent. Does the jury know that Smith committed the crime ? No, because knowledge requires truth; the jury believed it, but they didn’t know it. [5]

Also, most philosophers think that the belief must be justified . We don’t normally consider a lucky guess to be knowledge. (If you flip a coin but don’t look at the result yet, and just find yourself believing that it’s Heads, and in fact it is Heads, we don’t think you knew that it was Heads.) Yet there is substantial debate about what justification is.

2. Analysis of Justification

What would be required to transform the lucky guess that the coin came up Heads into knowledge ? One standard answer is ‘justification.’ [6]

Intuitively, you would have to acquire good reason to believe that the coin came up Heads: for example, you look at the coin. [7] In general, theories of justification either say that the factors that justify your belief must be available within your own first-person, conscious experience, or that they don’t need to be. We call the former theories ‘internalist’ and the latter ‘externalist.’ [8]

For example, some internalists are evidentialists : roughly, they say that your justification depends on the evidence you have, for example the awareness of the image of a president’s head on a coin. And some externalists are reliabilists : roughly, they say that whether you are justified depends on whether your belief was formed by a reliable belief-forming mechanism, for example, the physical process of vision. For evidentialists, the evidence you have seems “internal” to your first-person awareness: it’s what you’re aware of. And whether the process that formed your belief is reliable seems “external” to your first-person awareness: you might not even have any beliefs about photons and how they work.

3. Sources of Knowledge and Evidence

We’ve thought about what it means to have justified beliefs. [9] But when our beliefs are in fact justified, what is the source or explanation of that justification?

Surely we get some justification from empirical observation : using our five senses, the tools of science, and introspection (looking inside your own mind, for example learning that you believe that 2+2=4). [10] This justification is ‘ a posteriori ’ or ‘empirical,’ for example, looking at the coin-toss result.

Maybe there is some knowledge that we acquire through intuition, definitions, or some other putative non -empirical evidence. We call this ‘ a priori ’ knowledge or justification: justified but independently of any particular empirical observation or awareness of the evidence or justification required. [11] I seem to know, just by thinking about it, that there can be no coins that are both square and circular; I don’t need to consult scientists. [12]

Roughly speaking, rationalists (about justification) believe that we have important, valuable a priori knowledge about the world, knowledge that’s not merely about the meanings of our words or concepts. Empiricists , in contrast, believe that all of our important knowledge of the world is empirical. [13]

Beyond this, feminist epistemologists have argued that one’s knowledge, and whether one is taken seriously as a knower, can depend on one’s particular social position, including one’s gender. [14] To the traditional list of sources of knowledge, we might add one’s standpoint and situation, and also add emotion. [15]

4. The Structure of Knowledge, Justification, and Inference

Normally, we think we can infer new beliefs from our existing beliefs: we believe some propositions, and on the basis of those beliefs, conclude that some other propositions are true.