Importance of Exercise Essay

500 words essay on exercise essay.

Exercise is basically any physical activity that we perform on a repetitive basis for relaxing our body and taking away all the mental stress. It is important to do regular exercise. When you do this on a daily basis, you become fit both physically and mentally. Moreover, not exercising daily can make a person susceptible to different diseases. Thus, just like eating food daily, we must also exercise daily. The importance of exercise essay will throw more light on it.

Importance of Exercise

Exercising is most essential for proper health and fitness. Moreover, it is essential for every sphere of life. Especially today’s youth need to exercise more than ever. It is because the junk food they consume every day can hamper their quality of life.

If you are not healthy, you cannot lead a happy life and won’t be able to contribute to the expansion of society. Thus, one needs to exercise to beat all these problems. But, it is not just about the youth but also about every member of the society.

These days, physical activities take places in colleges more than often. The professionals are called to the campus for organizing physical exercises. Thus, it is a great opportunity for everyone who wishes to do it.

Just like exercise is important for college kids, it is also essential for office workers. The desk job requires the person to sit at the desk for long hours without breaks. This gives rise to a very unhealthy lifestyle.

They get a limited amount of exercise as they just sit all day then come back home and sleep. Therefore, it is essential to exercise to adopt a healthy lifestyle that can also prevent any damaging diseases .

Benefits of Exercise

Exercise has a lot of benefits in today’s world. First of all, it helps in maintaining your weight. Moreover, it also helps you reduce weight if you are overweight. It is because you burn calories when you exercise.

Further, it helps in developing your muscles. Thus, the rate of your body will increases which helps to burn calories. Moreover, it also helps in improving the oxygen level and blood flow of the body.

When you exercise daily, your brain cells will release frequently. This helps in producing cells in the hippocampus. Moreover, it is the part of the brain which helps to learn and control memory.

The concentration level in your body will improve which will ultimately lower the danger of disease like Alzheimer’s. In addition, you can also reduce the strain on your heart through exercise. Finally, it controls the blood sugar levels of your body so it helps to prevent or delay diabetes.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Conclusion of Importance of Exercise Essay

In order to live life healthily, it is essential to exercise for mental and physical development. Thus, exercise is important for the overall growth of a person. It is essential to maintain a balance between work, rest and activities. So, make sure to exercise daily.

FAQ of Importance of Exercise Essay

Question 1: What is the importance of exercise?

Answer 1: Exercise helps people lose weight and lower the risk of some diseases. When you exercise daily, you lower the risk of developing some diseases like obesity, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and more. It also helps to keep your body at a healthy weight.

Question 2: Why is exercising important for students?

Answer 2: Exercising is important for students because it helps students to enhance their cardiorespiratory fitness and build strong bones and muscles. In addition, it also controls weight and reduces the symptoms of anxiety and depression. Further, it can also reduce the risk of health conditions like heart diseases and more.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

Exercise: 7 benefits of regular physical activity.

You know exercise is good for you, but do you know how good? From boosting your mood to improving your sex life, find out how exercise can improve your life.

Want to feel better, have more energy and even add years to your life? Just exercise.

The health benefits of regular exercise and physical activity are hard to ignore. Everyone benefits from exercise, no matter their age, sex or physical ability.

Need more convincing to get moving? Check out these seven ways that exercise can lead to a happier, healthier you.

1. Exercise controls weight

Exercise can help prevent excess weight gain or help you keep off lost weight. When you take part in physical activity, you burn calories. The more intense the activity, the more calories you burn.

Regular trips to the gym are great, but don't worry if you can't find a large chunk of time to exercise every day. Any amount of activity is better than none. To gain the benefits of exercise, just get more active throughout your day. For example, take the stairs instead of the elevator or rev up your household chores. Consistency is key.

2. Exercise combats health conditions and diseases

Worried about heart disease? Hoping to prevent high blood pressure? No matter what your current weight is, being active boosts high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, the "good" cholesterol, and it decreases unhealthy triglycerides. This one-two punch keeps your blood flowing smoothly, which lowers your risk of heart and blood vessel, called cardiovascular, diseases.

Regular exercise helps prevent or manage many health problems and concerns, including:

- Metabolic syndrome.

- High blood pressure.

- Type 2 diabetes.

- Depression.

- Many types of cancer.

It also can help improve cognitive function and helps lower the risk of death from all causes.

3. Exercise improves mood

Need an emotional lift? Or need to lower stress after a stressful day? A gym session or brisk walk can help. Physical activity stimulates many brain chemicals that may leave you feeling happier, more relaxed and less anxious.

You also may feel better about your appearance and yourself when you exercise regularly, which can boost your confidence and improve your self-esteem.

4. Exercise boosts energy

Winded by grocery shopping or household chores? Regular physical activity can improve your muscle strength and boost your endurance.

Exercise sends oxygen and nutrients to your tissues and helps your cardiovascular system work more efficiently. And when your heart and lung health improve, you have more energy to tackle daily chores.

5. Exercise promotes better sleep

Struggling to snooze? Regular physical activity can help you fall asleep faster, get better sleep and deepen your sleep. Just don't exercise too close to bedtime, or you may be too energized to go to sleep.

6. Exercise puts the spark back into your sex life

Do you feel too tired or too out of shape to enjoy physical intimacy? Regular physical activity can improve energy levels and give you more confidence about your physical appearance, which may boost your sex life.

But there's even more to it than that. Regular physical activity may enhance arousal for women. And men who exercise regularly are less likely to have problems with erectile dysfunction than are men who don't exercise.

7. Exercise can be fun — and social!

Exercise and physical activity can be fun. They give you a chance to unwind, enjoy the outdoors or simply do activities that make you happy. Physical activity also can help you connect with family or friends in a fun social setting.

So take a dance class, hit the hiking trails or join a soccer team. Find a physical activity you enjoy, and just do it. Bored? Try something new, or do something with friends or family.

Exercise to feel better and have fun

Exercise and physical activity are great ways to feel better, boost your health and have fun. For most healthy adults, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends these exercise guidelines:

Aerobic activity. Get at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity. Or get at least 75 minutes of vigorous aerobic activity a week. You also can get an equal combination of moderate and vigorous activity. Aim to spread out this exercise over a few days or more in a week.

For even more health benefits, the guidelines suggest getting 300 minutes a week or more of moderate aerobic activity. Exercising this much may help with weight loss or keeping off lost weight. But even small amounts of physical activity can be helpful. Being active for short periods of time during the day can add up and have health benefits.

- Strength training. Do strength training exercises for all major muscle groups at least two times a week. One set of each exercise is enough for health and fitness benefits. Use a weight or resistance level heavy enough to tire your muscles after about 12 to 15 repetitions.

Moderate aerobic exercise includes activities such as brisk walking, biking, swimming and mowing the lawn.

Vigorous aerobic exercise includes activities such as running, swimming laps, heavy yardwork and aerobic dancing.

You can do strength training by using weight machines or free weights, your own body weight, heavy bags, or resistance bands. You also can use resistance paddles in the water or do activities such as rock climbing.

If you want to lose weight, keep off lost weight or meet specific fitness goals, you may need to exercise more.

Remember to check with a health care professional before starting a new exercise program, especially if you have any concerns about your fitness or haven't exercised for a long time. Also check with a health care professional if you have chronic health problems, such as heart disease, diabetes or arthritis.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- AskMayoExpert. Physical activity (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2021.

- Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2nd ed. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/our-work/physical-activity/current-guidelines. Accessed June 25, 2021.

- Peterson DM. The benefits and risk of aerobic exercise. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed June 24, 2021.

- Maseroli E, et al. Physical activity and female sexual dysfunction: A lot helps, but not too much. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2021; doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.04.004.

- Allen MS. Physical activity as an adjunct treatment for erectile dysfunction. Nature Reviews: Urology. 2019; doi:10.1038/s41585-019-0210-6.

- Tips for starting physical activity. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/tips-get-active/tips-starting-physical-activity. Accessed June 25, 2021.

- Laskowski ER (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. June 16, 2021.

Products and Services

- Mayo Clinic Sports Medicine

- A Book: The Mayo Clinic Diet Bundle

- A Book: Live Younger Longer

- Available Health Products from Mayo Clinic Store

- Available Solutions under FSA/HSA Coverage from Mayo Clinic Store

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Book of Home Remedies

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on High Blood Pressure

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- The Mayo Clinic Diet Online

- Balance exercises

- Blood Doping

- Can I exercise if I have atopic dermatitis?

- Core exercises

- Exercise and chronic disease

- Exercise and illness

- Stress relief

- Exercising with arthritis

- Fitness ball exercises videos

- Fitness program

- Fitness training routine

- Hate to exercise? Try these tips

- Hockey Flywheel

- How fit are you?

- Marathon and the Heat

- BMI and waist circumference calculator

- Mayo Clinic Minute: How to hit your target heart rate

- Staying active with Crohn's disease

- Strength training: How-to video collection

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

- Exercise 7 benefits of regular physical activity

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Physical Exercises and Their Health Benefits Essay

Exercises that include physical activities are very essential to both body and mental health of human beings. In fact this is one of the areas where many studies have been conducted by scholars from different parts of the world to show that exercise is essential to all people regardless of their age, sex and occupation. Healthcare givers also recommend that patients with chronic sicknesses should do some workouts to facilitate their healing. According to the recent studies on the importance of exercise to human beings, it is evident that people have begun to realize the need for doing exercise. In fact people from different parts of the world participate in various exercises and other physical activity in order to keep fit and remain healthy. This paper highlights some of the major importance of workouts to our bodies and why people should do exercises.

One of the major benefits of exercise is that it helps in maintaining a healthy body weight. Cases of people being overweight are common in the modern society due to people shying away from physical activities and desire for junk food. Change of lifestyles has made many people to be overweight and this comes with health complications. Participating in physical activity burns calories and this promotes weight loss. Exercises also help in maintaining weight loss among those working on how to lose some of their body weight.

Exercise makes an individual stronger and boosts the body energy. Some people are very weak to an extent that they are heavily fatigued by simple duties such as doing shopping or doing basic domestic chores. Regular exercise improves bone and muscle strength and give gives the body endurance to tiring activities. When you participate in regular workouts, oxygen and other necessary nutrients are delivered to the lungs, heart and other vital body organs to ensure that they are functioning well. Consequently, a person is able to do simple routine tasks without getting easily exhausted.

Exercise also improves moods and looks. Studies show that people who do not participate in any physical activities and workouts are mostly in bad moods and gloomy. Ordinarily, people get involved in some activities that may lower their moods and exercise helps in improving moods and maintain the charming appearance. Simple workouts stimulate the brain to release some chemicals that make an individual feel happy and relaxed. This also improves the facial looks therefore raising self-esteem and confidence. For those who want to keep fit and maintain certain body looks such as models, sports people and celebrities, exercise helps in achieving the desired physical body appearances.

Exercise is also believed to promote good sleeping habits. Sometimes it becomes difficult to fall asleep or to remain asleep especially after a busy day. Regular exercise can help in promoting better sleep and ensure that it is a continuous one. To the married people, sex life is important and cannot be taken for granted. However, this has become a major challenge to the modern couples because many people retire to their beds feeling too tired to participate in physical intimacy. Exercise makes helps in maintaining a positive sex life and it promotes arousal for both women and men. Studies show that regular physical activity helps men to overcome erectile dysfunction making sex life more enjoyable.

Exercise is also paramount for maintaining better health. Regular workouts improve the immune system and this reduces the chances of getting sick. However, it is worth noting that over exercising can destroy the body immune system. Additionally, regular exercise reduces stress thereby contributing to a healthy living. Regular workouts take the body and mind from the stressing activities and this relieves the body the weight of the stress. The energy used in handling stress is therefore used for other productive processes of the body. Some people suffer from poor digestion and metabolism especially the elderly ones. Exercise helps in ensuring that digestion and absorption of food in the body take place as well. Workouts also increase the rate of metabolisms and the end result is good health. For those doing trainings such as weight lifting and muscle builders, workouts promotes muscle buildup and helps in changing the body shape to the desired body shape. Regular exercise also improves the body stamina and enhances flexibility and stability. Workouts stretch the body and ensure a good posture. This is vital for body stability and it also prevents early body aging. It also reduces the chances of getting easily injured when doing routine duties.

Generally, it is evident that exercise is good for both our mental and body health. It is also worth noting that exercise is enjoyable and can be used to bring people close to their friends. Physical activity is fun and it gives people an opportunity to participate in things that make them happy. Participating in a dance class or soccer club is very enjoyable and makes you to feel relaxed. However it is important for the people with special health conditions to ensure that they have consulted their healthcare for advice on the best workouts to avoid more harm to their body.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, August 21). Physical Exercises and Their Health Benefits. https://ivypanda.com/essays/physical-exercises-and-their-health-benefits/

"Physical Exercises and Their Health Benefits." IvyPanda , 21 Aug. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/physical-exercises-and-their-health-benefits/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Physical Exercises and Their Health Benefits'. 21 August.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Physical Exercises and Their Health Benefits." August 21, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/physical-exercises-and-their-health-benefits/.

1. IvyPanda . "Physical Exercises and Their Health Benefits." August 21, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/physical-exercises-and-their-health-benefits/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Physical Exercises and Their Health Benefits." August 21, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/physical-exercises-and-their-health-benefits/.

- Aerobic and Anaerobic Workouts Comparison

- Daily Workouts App Evaluation

- Work Out and Stay Healthy: Persuading Classmates

- The Problem of Falling Asleep

- Endurance Training Programs in Soldiers and Athletes

- Weight Training: Principles and Recommendations

- Physical Fitness Training Programs for Athletes

- Muay Thai and Kickboxing Promotion in the UAE

- Market Outcomes for Resistance Bands

- The Governmental Healthcare Program and Patient Behavior

- The Benefit of Personal Fitness

- Obesity and Benefits of Exercising

- Wellness Goal: Diets and Exercises for Gaining Lean Body Mass

- Impacts of the Regular Exercise on the Human Life Quality

- Yoga for Depression and Anxiety

Physical Activity Is Good for the Mind and the Body

Health and Well-Being Matter is the monthly blog of the Director of the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Everyone has their own way to “recharge” their sense of well-being — something that makes them feel good physically, emotionally, and spiritually even if they aren’t consciously aware of it. Personally, I know that few things can improve my day as quickly as a walk around the block or even just getting up from my desk and doing some push-ups. A hike through the woods is ideal when I can make it happen. But that’s me. It’s not simply that I enjoy these activities but also that they literally make me feel better and clear my mind.

Mental health and physical health are closely connected. No kidding — what’s good for the body is often good for the mind. Knowing what you can do physically that has this effect for you will change your day and your life.

Physical activity has many well-established mental health benefits. These are published in the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans and include improved brain health and cognitive function (the ability to think, if you will), a reduced risk of anxiety and depression, and improved sleep and overall quality of life. Although not a cure-all, increasing physical activity directly contributes to improved mental health and better overall health and well-being.

Learning how to routinely manage stress and getting screened for depression are simply good prevention practices. Awareness is especially critical at this time of year when disruptions to healthy habits and choices can be more likely and more jarring. Shorter days and colder temperatures have a way of interrupting routines — as do the holidays, with both their joys and their stresses. When the plentiful sunshine and clear skies of temperate months give way to unpredictable weather, less daylight, and festive gatherings, it may happen unconsciously or seem natural to be distracted from being as physically active. However, that tendency is precisely why it’s so important that we are ever more mindful of our physical and emotional health — and how we can maintain both — during this time of year.

Roughly half of all people in the United States will be diagnosed with a mental health disorder at some point in their lifetime, with anxiety and anxiety disorders being the most common. Major depression, another of the most common mental health disorders, is also a leading cause of disability for middle-aged adults. Compounding all of this, mental health disorders like depression and anxiety can affect people’s ability to take part in health-promoting behaviors, including physical activity. In addition, physical health problems can contribute to mental health problems and make it harder for people to get treatment for mental health disorders.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the need to take care of our physical and emotional health to light even more so these past 2 years. Recently, the U.S. Surgeon General highlighted how the pandemic has exacerbated the mental health crisis in youth .

The good news is that even small amounts of physical activity can immediately reduce symptoms of anxiety in adults and older adults. Depression has also shown to be responsive to physical activity. Research suggests that increased physical activity, of any kind, can improve depression symptoms experienced by people across the lifespan. Engaging in regular physical activity has also been shown to reduce the risk of developing depression in children and adults.

Though the seasons and our life circumstances may change, our basic needs do not. Just as we shift from shorts to coats or fresh summer fruits and vegetables to heartier fall food choices, so too must we shift our seasonal approach to how we stay physically active. Some of that is simply adapting to conditions: bundling up for a walk, wearing the appropriate shoes, or playing in the snow with the kids instead of playing soccer in the grass.

Sometimes there’s a bit more creativity involved. Often this means finding ways to simplify activity or make it more accessible. For example, it may not be possible to get to the gym or even take a walk due to weather or any number of reasons. In those instances, other options include adding new types of movement — such as impromptu dance parties at home — or doing a few household chores (yes, it all counts as physical activity).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I built a makeshift gym in my garage as an alternative to driving back and forth to the gym several miles from home. That has not only saved me time and money but also afforded me the opportunity to get 15 to 45 minutes of muscle-strengthening physical activity in at odd times of the day.

For more ideas on how to get active — on any day — or for help finding the motivation to get started, check out this Move Your Way® video .

The point to remember is that no matter the approach, the Physical Activity Guidelines recommend that adults get at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity (anything that gets your heart beating faster) each week and at least 2 days per week of muscle-strengthening activity (anything that makes your muscles work harder than usual). Youth need 60 minutes or more of physical activity each day. Preschool-aged children ages 3 to 5 years need to be active throughout the day — with adult caregivers encouraging active play — to enhance growth and development. Striving toward these goals and then continuing to get physical activity, in some shape or form, contributes to better health outcomes both immediately and over the long term.

For youth, sports offer additional avenues to more physical activity and improved mental health. Youth who participate in sports may enjoy psychosocial health benefits beyond the benefits they gain from other forms of leisure-time physical activity. Psychological health benefits include higher levels of perceived competence, confidence, and self-esteem — not to mention the benefits of team building, leadership, and resilience, which are important skills to apply on the field and throughout life. Research has also shown that youth sports participants have a reduced risk of suicide and suicidal thoughts and tendencies. Additionally, team sports participation during adolescence may lead to better mental health outcomes in adulthood (e.g., less anxiety and depression) for people exposed to adverse childhood experiences. In addition to the physical and mental health benefits, sports can be just plain fun.

Physical activity’s implications for significant positive effects on mental health and social well-being are enormous, impacting every facet of life. In fact, because of this national imperative, the presidential executive order that re-established the President’s Council on Sports, Fitness & Nutrition explicitly seeks to “expand national awareness of the importance of mental health as it pertains to physical fitness and nutrition.” While physical activity is not a substitute for mental health treatment when needed and it’s not the answer to certain mental health challenges, it does play a significant role in our emotional and cognitive well-being.

No matter how we choose to be active during the holiday season — or any season — every effort to move counts toward achieving recommended physical activity goals and will have positive impacts on both the mind and the body. Along with preventing diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, and the additional risks associated with these comorbidities, physical activity’s positive effect on mental health is yet another important reason to be active and Move Your Way .

As for me… I think it’s time for a walk. Happy and healthy holidays, everyone!

Yours in health, Paul

Paul Reed, MD Rear Admiral, U.S. Public Health Service Deputy Assistant Secretary for Health Director, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by ODPHP or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

Benefits of Physical Activity

Obesity and Excess Weight Increase Risk of Severe Illness; Racial and Ethnic Disparities Persist

Food Assistance and Food Systems Resources

Immediate Benefits

Weight management, reduce your health risk, strengthen your bones and muscles, improve your ability to do daily activities and prevent falls, increase your chances of living longer, manage chronic health conditions & disabilities.

Regular physical activity is one of the most important things you can do for your health. Being physically active can improve your brain health , help manage weight , reduce the risk of disease , strengthen bones and muscles , and improve your ability to do everyday activities .

Adults who sit less and do any amount of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity gain some health benefits. Only a few lifestyle choices have as large an impact on your health as physical activity.

Everyone can experience the health benefits of physical activity – age, abilities, ethnicity, shape, or size do not matter.

Some benefits of physical activity on brain health [PDF-14.4MB] happen right after a session of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Benefits include improved thinking or cognition for children 6 to 13 years of age and reduced short-term feelings of anxiety for adults. Regular physical activity can help keep your thinking, learning, and judgment skills sharp as you age. It can also reduce your risk of depression and anxiety and help you sleep better.

Both eating patterns and physical activity routines play a critical role in weight management. You gain weight when you consume more calories through eating and drinking than the amount of calories you burn , including those burned during physical activity.

To maintain your weight: Work your way up to 150 minutes a week of moderate physical activity, which could include dancing or yard work. You could achieve the goal of 150 minutes a week with 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week.

People vary greatly in how much physical activity they need for weight management. You may need to be more active than others to reach or maintain a healthy weight.

To lose weight and keep it off: You will need a high amount of physical activity unless you also adjust your eating patterns and reduce the amount of calories you’re eating and drinking. Getting to and staying at a healthy weight requires both regular physical activity and healthy eating.

See more information about:

- Getting started with weight loss .

- Getting started with physical activity .

- Improving your eating patterns .

Learn more about the health benefits of physical activity for children, adults, and adults age 65 and older.

See these tips on getting started.

The good news [PDF-14.5MB] is that moderate physical activity , such as brisk walking, is generally safe for most people .

Cardiovascular Disease

Heart disease and stroke are two leading causes of death in the United States. Getting at least 150 minutes a week of moderate physical activity can put you at a lower risk for these diseases. You can reduce your risk even further with more physical activity. Regular physical activity can also lower your blood pressure and improve your cholesterol levels.

Type 2 Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome

Regular physical activity can reduce your risk of developing type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is some combination of too much fat around the waist, high blood pressure, low high-density lipoproteins (HDL) cholesterol, high triglycerides, or high blood sugar. People start to see benefits at levels from physical activity even without meeting the recommendations for 150 minutes a week of moderate physical activity. Additional amounts of physical activity seem to lower risk even more.

Infectious Diseases

Physical activity may help reduce the risk of serious outcomes from infectious diseases, including COVID-19, the flu, and pneumonia. For example:

- People who do little or no physical activity are more likely to get very sick from COVID-19 than those who are physically active. A CDC systematic review [PDF-931KB] found that physical activity is associated with a decrease in COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths, while inactivity increases that risk.

- People who are more active may be less likely to die from flu or pneumonia. A CDC study found that adults who meet the aerobic and muscle-strengthening physical activity guidelines are about half as likely to die from flu and pneumonia as adults who meet neither guideline.

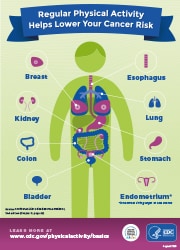

Some Cancers

Being physically active lowers your risk for developing several common cancers . Adults who participate in greater amounts of physical activity have reduced risks of developing cancers of the:

- Colon (proximal and distal)

- Endometrium

- Esophagus (adenocarcinoma)

- Stomach (cardia and non-cardia adenocarcinoma)

If you are a cancer survivor, getting regular physical activity not only helps give you a better quality of life, but also improves your physical fitness.

Learn more about Physical Activity and Cancer

As you age, it’s important to protect your bones, joints, and muscles – they support your body and help you move. Keeping bones, joints, and muscles healthy can help ensure that you’re able to do your daily activities and be physically active.

Muscle-strengthening activities like lifting weights can help you increase or maintain your muscle mass and strength. This is important for older adults who experience reduced muscle mass and muscle strength with aging. Slowly increasing the amount of weight and number of repetitions you do as part of muscle strengthening activities will give you even more benefits, no matter your age.

Everyday activities include climbing stairs, grocery shopping, or playing with your grandchildren. Being unable to do everyday activities is called a functional limitation. Physically active middle-aged or older adults have a lower risk of functional limitations than people who are inactive.

For older adults, doing a variety of physical activity improves physical function and decreases the risk of falls or injury from a fall . Include physical activities such as aerobic, muscle strengthening, and balance training. Multicomponent physical activity can be done at home or in a community setting as part of a structured program.

Hip fracture is a serious health condition that can result from a fall. Breaking a hip have life-changing negative effects, especially if you’re an older adult. Physically active people have a lower risk of hip fracture than inactive people.

See physical activity recommendations for different groups, including:

- Children age 3-5 .

- Children and adolescents age 6-17 .

- Adults age 18-64 .

- Adults 65 and older .

- Adults with chronic health conditions and disabilities .

- Healthy pregnant and postpartum women .

An estimated 110,000 deaths per year could be prevented if US adults ages 40 and older increased their moderate-to-vigorous physical activity by a small amount. Even 10 minutes more a day would make a difference.

Taking more steps a day also helps lower the risk of premature death from all causes. For adults younger than 60, the risk of premature death leveled off at about 8,000 to 10,000 steps per day. For adults 60 and older, the risk of premature death leveled off at about 6,000 to 8,000 steps per day.

Regular physical activity can help people manage existing chronic conditions and disabilities. For example, regular physical activity can:

- Reduce pain and improve function, mood, and quality of life for adults with arthritis.

- Help control blood sugar levels and lower risk of heart disease and nerve damage for people with type 2 diabetes.

- Health Benefits Associated with Physical Activity for People with Chronic Conditions and Disabilities [PDF-14.4MB]

- Key Recommendations for Adults with Chronic Conditions and Disabilities [PDF-14.4MB]

Active People, Healthy Nation SM is a CDC initiative to help people be more physically active.

Sign up today!

To receive email updates about this topic, enter your email address.

- Physical Activity

- Overweight & Obesity

- Healthy Weight, Nutrition, and Physical Activity

- Breastfeeding

- Micronutrient Malnutrition

- State and Local Programs

- Physical Activity for Arthritis

- Diabetes — Get Active

- Physical Activity for People with Disabilities

- Prevent Heart Disease

- Healthy Schools – Promoting Healthy Behaviors

- Healthy Aging

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Physical Exercise — The Importance of Exercise for a Healthy Lifestyle

The Importance of Exercise for a Healthy Lifestyle

- Categories: Healthy Lifestyle Physical Exercise

About this sample

Words: 638 |

Published: Mar 16, 2024

Words: 638 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Impact on physical health, impact on mental health, barriers to exercise.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 886 words

2 pages / 1117 words

4 pages / 1771 words

1 pages / 578 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Physical Exercise

Easterlin, M. C., Chung, P. J., & Leng, M. (2023). Association of Team Sports Participation With Long-term Mental Health Outcomes Among Individuals Exposed to Adverse Childhood Experiences. JAMA Pediatrics.National Public Radio. [...]

High blood pressure is a significant health concern affecting adults worldwide. This quantitative essay employs a research investigation approach to examine the effects of physical activity on blood pressure levels in adults. [...]

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Mental disorders affect one in four people. Retrieved from https://www.harpersbazaar.com/uk/beauty/fitness-wellbeing/a28917865/the-mental-health-benefits-of-boxing/

In this essay on the benefits of exercise, we will explore the multitude of advantages that regular physical activity can offer. Exercise is not merely a means to improve physical appearance; it is a powerful tool that can [...]

My physical goals include increasing my fitness levels as well as weight loss. I would like to work on strengthening my body through gym and yoga whilst also embarking on a cardio routine that will mainly include running and [...]

What do you feel after exercise? Exercise is the cheapest and most useful tool for not only stress, but for many other things. For me, when I exercise, I get a feeling of comfort and relaxation. My whole body changes into a more [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

How Exercise Strengthens Your Brain

Physical activity improves cognitive and mental health in all sorts of ways. Here’s why, and how to reap the benefits.

By Dana G. Smith

Growing up in the Netherlands, Henriette van Praag had always been active, playing sports and riding her bike to school every day. Then, in the late-1990s, while working as a staff scientist at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego, she discovered that exercise can spur the growth of new brain cells in mature mice. After that, her approach to exercise changed.

“I started to take it more seriously,” said Dr. van Praag, now an associate professor of biomedical science at Florida Atlantic University. Today, that involves doing CrossFit and running five or six miles several days a week.

Whether exercise can cause new neurons to grow in adult humans — a feat previously thought impossible, and a tantalizing prospect to treat neurodegenerative diseases — is still up for debate . But even if it’s not possible, physical activity is excellent for your brain, improving mood and cognition through “a plethora” of cellular changes, Dr. van Praag said.

What are some of the benefits, specifically?

Exercise offers short-term boosts in cognition. Studies show that immediately after a bout of physical activity, people perform better on tests of working memory and other executive functions . This may be in part because movement increases the release of neurotransmitters in the brain, most notably epinephrine and norepinephrine.

“These kinds of molecules are needed for paying attention to information,” said Marc Roig, an associate professor in the School of Physical and Occupational Therapy at McGill University. Attention is essential for working memory and executive functioning, he added.

The neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin are also released with exercise, which is thought to be a main reason people often feel so good after going for a run or a long bike ride.

The brain benefits really start to emerge, though, when we work out consistently over time. Studies show that people who work out several times a week have higher cognitive test scores, on average, than people who are more sedentary. Other research has found that a person’s cognition tends to improve after participating in a new aerobic exercise program for several months.

Dr. Roig added the caveat that the effects on cognition aren’t huge, and not everyone improves to the same degree. “You cannot acquire a super memory just because you exercised,” he said.

Physical activity also benefits mood . People who work out regularly report having better mental health than people who are sedentary. And exercise programs can be effective at treating people’s depression, leading some psychiatrists and therapists to prescribe physical activity. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendation of 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity or 75 minutes of vigorous aerobic activity per week is a good benchmark.

Perhaps most remarkable, exercise offers protection against neurodegenerative diseases. “Physical activity is one of the health behaviors that’s shown to be the most beneficial for cognitive function and reducing risk of Alzheimer’s and dementia,” said Michelle Voss, an associate professor of psychological and brain sciences at the University of Iowa.

How does exercise do all that?

It starts with the muscles. When we work out, they release molecules that travel through the blood up to the brain. Some, like a hormone called irisin, have “neuroprotective” qualities and have been shown to be linked to the cognitive health benefits of exercise, said Christiane Wrann, an associate professor of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School who studies irisin . (Dr. Wrann is also a consultant for a pharmaceutical company, Aevum Therapeutics, hoping to harness irisin’s effects into a drug.)

Good blood flow is essential to obtain the benefits of physical activity. And conveniently, exercise improves circulation and stimulates the growth of new blood vessels in the brain. “It’s not just that there’s increased blood flow,” Dr. Voss said. “It’s that there’s a greater chance, then, for signaling molecules that are coming from the muscle to get delivered to the brain.”

Once these signals are in the brain, other chemicals are released locally. The star of the show is a hormone called brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or B.D.N.F., that is essential for neuron health and creating new connections — called synapses — between neurons. “It’s like a fertilizer for brain cells to recover from damage,” Dr. Voss said. “And also for synapses on nerve cells to connect with each other and sustain those connections.”

A greater number of blood vessels and connections between neurons can actually increase the size of different brain areas. This effect is especially noticeable in older adults because it can offset the loss of brain volume that happens with age. The hippocampus, an area important for memory and mood, is particularly affected. “We know that it shrinks with age,” Dr. Roig said. “And we know that if we exercise regularly, we can prevent this decline.”

Exercise’s effect on the hippocampus may be one way it helps protect against Alzheimer’s disease, which is associated with significant changes to that part of the brain. The same goes for depression; the hippocampus is smaller in people who are depressed, and effective treatments for depression , including medications and exercise, increase the size of the region.

What kind of exercise is best for your brain?

The experts emphasized that any exercise is good, and the type of activity doesn’t seem to matter, though most of the research has involved aerobic exercise. But, they added, higher-intensity workouts do appear to confer a bigger benefit for the brain.

Improving your overall cardiovascular fitness level also appears to be key. “It’s dose-dependent,” Dr. Wrann said. “The more you can improve your cardiorespiratory fitness, the better the benefits are.”

Like Dr. van Praag, Dr. Voss has incorporated her research into her life, making a concerted effort to engage in higher intensity exercise. For example, on busy days when she can’t fit in a full workout, she’ll seek out hills to bike up on her commute to work. “Even if it’s a little,” she said, “it’s still better than nothing.”

Dana G. Smith is a Times reporter covering personal health, particularly aging and brain health. More about Dana G. Smith

Let Us Help You Pick Your Next Workout

Looking for a new way to get moving we have plenty of options..

To develop a sustainable exercise habit, experts say it helps to tie your workout to something or someone .

Viral online exercise challenges might get you in shape in the short run, but they may not help you build sustainable healthy habits. Here’s what fitness fads get wrong .

Does it really matter how many steps you take each day? The quality of the steps you take might be just as important as the amount .

Is your workout really working for you? Take our quiz to find out .

To help you start moving, we tapped fitness pros for advice on setting realistic goals for exercising and actually enjoying yourself.

You need more than strength to age well — you also need power. Here’s how to measure how much you have and here’s how to increase yours .

Pick the Right Equipment With Wirecutter’s Recommendations

Want to build a home gym? These five things can help you transform your space into a fitness center.

Transform your upper-body workouts with a simple pull-up bar and an adjustable dumbbell set .

Choosing the best running shoes and running gear can be tricky. These tips make the process easier.

A comfortable sports bra can improve your overall workout experience. These are the best on the market .

Few things are more annoying than ill-fitting, hard-to-use headphones. Here are the best ones for the gym and for runners .

- Importance Of Exercises Essay

Importance of Exercise Essay

500+ words essay on the importance of exercise.

We all know that exercise is extremely important in our daily lives, but we may not know why or what exercise can do. It’s important to remember that we have evolved from nomadic ancestors who spent all their time moving around in search of food and shelter, travelling large distances on a daily basis. Our bodies are designed and have evolved to be regularly active. Over time, people may come across problems if they sit down all day at a desk or in front of the TV and minimise the amount of exercise they do. Exercise is a bodily movement performed in order to develop or maintain physical fitness and good health overall. Exercise leads to the physical exertion of sufficient intensity, duration and frequency to achieve or maintain vigour and health. This essay on the importance of exercise will help students become familiar with the several benefits of doing exercise regularly. They must go through this essay so as to get an idea of how to write essays on similar topics.

Need of Exercise

The human body is like a complex and delicate machine which comprises several small parts. A slight malfunction of one part leads to the breakdown of the machine. In a similar way, if such a situation arises in the human body, it also leads to malfunctioning of the body. Exercise is one of the healthy lifestyles which contributes to optimum health and quality of life. People who exercise regularly can reduce their risk of death. By doing exercise, active people increase their life expectancy by two years compared to inactive people. Regular exercise and good physical fitness enhance the quality of life in many ways. Physical fitness and exercise can help us to look good, feel good, and enjoy life. Moreover, exercise provides an enjoyable way to spend leisure time.

Exercise helps a person develop emotional balance and maintain a strong self-image. As people get older, exercise becomes more important. This is because, after the age of 30, the heart’s blood pumping capacity declines at a rate of about 8 per cent each decade. Exercise is also vital for a child’s overall development. Exercising helps to maintain a healthy weight by stoking our metabolism, utilizing and burning the extra calories.

Types of Exercise

There are three broad intensities of exercise:

1) Light exercise – Going for a walk is an example of light exercise. In this, the exerciser is able to talk while exercising.

2) Moderate exercise – Here, the exerciser feels slightly out of breath during the session. Examples could be walking briskly, cycling moderately or walking up a hill.

3) Vigorous exercise – While performing this exercise, the exerciser is panting during the activity. The exerciser feels his/her body being pushed much nearer its limit compared to the other two intensities. This could include running, cycling fast, and heavy-weight training.

Importance of Exercise

Regular exercise increases our fitness level and physical stamina. It plays a crucial role in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases. It can help with blood lipid abnormalities, diabetes and obesity. Moreover, it can help to reduce blood pressure. Regular exercise substantially reduces the risk of dying of coronary heart disease and eases the risk of stroke and colon cancer. People of all age groups benefit from exercising.

Exercise can be effective in improving the mental well-being of human beings. It relieves human stress and anxiety. When we come back from work or school, we feel exhausted after a whole day of work. If we can go out to have a walk or jog for at least 30 minutes, it makes us feel happy and relaxed. A number of studies have found that a lifestyle that includes exercise helps alleviate depression. Those who can maintain regular exercise will also reduce their chances of seeing a doctor. Without physical activity, the body’s muscles lose their strength, endurance and ability to function properly. Regular exercise keeps all parts of the body in continuous activity. It improves overall health and fitness, as well as decreases the risk of many chronic diseases. Therefore, physical exercise is very important in our life.

Exercise can play a significant role in keeping the individual, society, community and nation wealthy. If the citizens of a country are healthy, the country is sure to touch heights in every facet of life. The country’s healthy generation can achieve the highest marks in various fields and thereby enable their country to win laurels and glory at the international level. The first step is always the hardest. However, if we can overcome it, and exercise for 21 days continuously, it will be a new beginning for a healthy life.

Did you find the “Importance of Exercise essay” useful for improving your writing skills? Do let us know your view in the comment section. Keep Learning, and don’t forget to download the BYJU’S App for more interesting study videos.

Frequently Asked Questions on the Importance of Exercises Essay

What are the benefits of exercising regularly.

Regular exercise helps in the relaxation of the mind and body and keeps the body fit. It improves flexibility and blood circulation.

Which are some of the easy exercises that can be done at home?

Sit-ups, bicycle crunches, squats, lunges and planks are examples of easy exercises which can be done at home without the help of costly equipment.

Is cycling an effective form of exercise?

Cycling is a low-impact exercise and acts as a good muscle workout.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Counselling

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med

- v.8(7); 2018 Jul

Health Benefits of Exercise

Gregory n. ruegsegger.

1 Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri 65211

Frank W. Booth

2 Department of Medical Pharmacology and Physiology, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri 65211

3 Department of Nutrition and Exercise Physiology, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri 65211

4 Dalton Cardiovascular Research Center, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri 65211

Overwhelming evidence exists that lifelong exercise is associated with a longer health span, delaying the onset of 40 chronic conditions/diseases. What is beginning to be learned is the molecular mechanisms by which exercise sustains and improves quality of life. The current review begins with two short considerations. The first short presentation concerns the effects of endurance exercise training on cardiovascular fitness, and how it relates to improved health outcomes. The second short section contemplates emerging molecular connections from endurance training to mental health. Finally, approximately half of the remaining review concentrates on the relationships between type 2 diabetes, mitochondria, and endurance training. It is now clear that physical training is complex biology, invoking polygenic interactions within cells, tissues/organs, systems, with remarkable cross talk occurring among the former list.

The aim of this introduction is briefly to document facts that health benefits of physical activity predate its readers. In the 5th century BC, the ancient physician Hippocrates stated: “All parts of the body, if used in moderation and exercised in labors to which each is accustomed, become thereby healthy and well developed and age slowly; but if they are unused and left idle, they become liable to disease, defective in growth and age quickly.” However, by the 21st century, the belief in the value of exercise for health has faded so considerably, the lack of exercise now presents a major public health problem ( Fig. 1 ) ( Booth et al. 2012 ). Similarly, the lack of exercise was classified as an actual cause of chronic diseases and death ( Mokdad et al. 2004 ).

Simplistic overview of how physical activity can prevent the development of type 2 diabetes and one of its complications, cardiovascular disease. Physical inactivity is an actual cause of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and tens of other chronic conditions ( Table 1 ) via interaction with other factors (e.g., age, diet, gender, and genetics) to increase disease risk factors. This leads to chronic disease, reduced quality of life, and premature death. However, physical activity can prevent and, in some cases, treat disease progression associated with physical inactivity and other genetic and environmental factors.

Published in 1953, Jeremy N. Morris and colleagues conducted the first rigorous epidemiological study investigating physical activity and chronic disease risk, in which coronary heart disease (CHD) rates were increased in physically inactive bus drivers versus active conductors ( Morris et al. 1953 ). Since this pioneering report, a plethora of evidence shows that physical inactivity is associated with the development of 40 chronic diseases ( Table 1 ), including major noncommunicable diseases such as type 2 diabetes (T2D) and CHD, and as premature mortality ( Booth et al. 2012 ).

Worsening of 40 conditions caused by the lack of physical activity with growth, maturation, and aging throughout life span

The breadth of the list implies that a single molecular target will not substitute for appropriate daily physical activity to prevent the loss of all listed items.

In this review, we highlight the far-reaching health benefits of physical activity. However, note that the studies cited here represent only a fraction of the >100,000 studies showing positive associations between the terms “exercise” and “health.” In addition, we discuss how exercise promotes complex integrative responses that lead to multisystem responses to exercise, an underappreciated area of medical research. Finally, we consider how strategies that “mimic” parts of exercise training compare with physical exercise for their potential to combat metabolic disease.

EXERCISE IMPROVES CARDIORESPIRATORY FITNESS

There is arguably no measure more important for health than cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) (commonly measured by maximal oxygen uptake, VO 2max ) ( Blair et al. 1989 ). For example, Myers et al. (2002 ) showed that each 1 metabolic equivalent (1 MET) increase in exercise-test performance conferred a 12% improvement in survival, stating that “VO 2max is a more powerful predictor of mortality among men than other established risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD).” Low CRF is also well established as an independent risk factor of T2D ( Booth et al. 2002 ) and CVD morbidity and mortality ( Kodama et al. 2009 ; Gupta et al. 2011 ). Similarly, Kokkinos et al. (2010) reported that men who transitioned from having low to high CRF decreased their mortality risk by ∼50% over an 8-yr period, whereas men who transitioned from having high to low CRF increased their mortality risk by ∼50%.

Importantly then, from the above paragraph, physical activity and inactivity are major environmental modulators of CRF, increasing and decreasing it, respectively, often through independent pathways. Findings from rats selectively bred for high or low intrinsic aerobic capacity show that rats bred for high capacity, which are also more physically active, have 28%–42% increases in life span compared to low-capacity rats ( Koch et al. 2011 ). Endurance exercise is well recognized to improve CRF and cardiometabolic risk factors. Exercise improves numerous factors speculated to limit VO 2max including, but not restricted to, the capacity to transport oxygen (e.g., cardiac output), oxygen diffusion to working muscles (e.g., capillary density, membrane permeability, muscle myoglobin content), and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) generation (e.g., mitochondrial density, protein concentrations).

Data from the HERITAGE Family Study has provided some of the first knowledge of genes associated with VO 2max plasticity because of endurance-exercise training. Following 6 wk of cycling training at 70% of pretraining VO 2max , Timmons et al. (2010) performed messenger RNA (mRNA) expression microarray profiling to identify molecules potentially predicting VO 2max training responses, and then assessed these molecular predictors to determine whether DNA variants in these genes correlated with VO 2max training responses. This approach identified 29 mRNAs in skeletal muscle and 11 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that predicted ∼50% and ∼23%, respectively, of the variability in VO 2max plasticity following aerobic training ( Timmons et al. 2010 ). Intriguingly, pretraining levels of these mRNAs were greater in subjects that achieved greater increases in VO 2max following aerobic training, and of the 29 mRNAs, >90% were unchanged with aerobic training, suggesting that alternative exercise intervention paradigms or pharmacological strategies may be needed to improve VO 2max in individuals with a low responder profile for the identified predictor genes ( Timmons et al. 2010 ). Keller et al. (2011) found that, in response to endurance training, improvements in VO 2max were associated with effectively up-regulating proangiogenic gene networks and miRNAs influencing the transcription factor–directed networks for runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1), paired box gene 3 (PAC3), and sex-determining region Y box 9 (SOX9). Collectively, these results led the investigators to speculate that improvements in skeletal muscle oxygen sensing and angiogenesis are primary determinates in training responses in VO 2max ( Keller et al. 2011 ).

Clinically important concepts have emerged from the pioneering HERITAGE Family Study. One new clinical concept is that a threshold dose–response relationship influences the percentage of subjects responding with an increase in VO 2max to endurance training volumes (with volume being defined here as the product of intensity × duration), as previously published ( Slentz et al. 2005 , 2007 ). Ross et al. (2015) later extended the aforementioned Slentz et al. studies. After a 24-wk-long endurance training study ( Ross et al. 2015 ), percentages of women and men identified as nonresponders to the training (i.e., defined as not increasing their VO 2peak ) progressively fell inversely to a two stepwise progressive increase in endurance-exercise training volume, as described next. Thirty-nine percent (15 of 39) of training subjects did not increase their VO 2peak in response to the low-amount, low-intensity training; 18% (9 of 51) had no increase in VO 2peak in the group having high-amount, low-intensity training; and 0% (0 of 31) who underwent high-amount, high-intensity training did not increase their VO 2peak . A biological basis for the dose–response relationship in the previous sentence could be made from an analysis of interval training (IT) and IT/continuous-training studies published from 1965 to 2012 ( Bacon et al. 2013 ). A second older concept is being reinvigorated; Bacon et al. (2013) indicate that different endurance-exercise intensities and durations are needed for different systems in the body. They suggest that very short periods of high-intensity endurance-type exercise may be needed to reach a threshold for peripheral metabolic adaptations, but that longer training durations at lower intensities are required to see large changes in maximal cardiac output and VO 2max .

A comparable example exists for resistance training. Maximal resistance loads require a minimum of 2 min/per wk for each muscle group recruited by a specific maneuver to obtain a strength training adaptation [(8 contractions/set × 2 sec/contraction × 3 sets/day) × 2 days/wk) = 96 sec]. As of 2016, one opinion from Sarzynski et al. (2016) for the molecular mechanisms by which endurance exercise drives VO 2max include, but are not limited to, calcium signaling, energy sensing and partitioning, mitochondrial biogenesis, angiogenesis, immune functions, and regulation of autophagy and apoptosis.

Perhaps more importantly, lifelong aerobic exercise training preserves VO 2max into old age. CRF generally increases until early adulthood, then declines the remainder of life in sedentary humans ( Astrand 1956 ). The age-related decline in VO 2max is not trivial, as Schneider (2013) reported a ∼40% decline in healthy males and females spanning from 20 to 70 yr of age. However, cross-sectional data show that with lifelong aerobic exercise training, trained individuals often have the same VO 2max as a sedentary individual four decades younger ( Booth et al. 2012 ). Myers et al. (2002) found that low estimated VO 2max increases mortality 4.5-fold compared to high estimated VO 2max . They concluded, “Exercise capacity is a more powerful predictor of mortality among men than other established risk factors for cardiovascular disease.” Given the strong association between CRF, chronic disease, and mortality, we feel identifying the molecular transducers that cause age-related reductions in CRF may have profound implications for improving health span and delaying the onset of chronic disease. In two of our recent papers, transcriptomics was performed on the triceps muscle ( Toedebusch et al. 2016 ) and on the cardiac left ventricle ( Ruegsegger et al. 2017 ). We were addressing the question of what molecule initiates the beginning of the lifelong decline in aerobic capacity with aging. Aerobic capacity (VO 2max ) involves, at a minimum, the next systems/tissues, as oxygen travels through the mouth, airways, pulmonary membrane, pulmonary circulation, left heart, aorta/arteries/capillaries, and sarcoplasm/myoglobin to mitochondria. We allowed female rats access, or no access, to running wheels from 5 to 27 wk of age. Surprisingly, voluntary running had no effect on the delay in the beginning of the lifetime decrease in VO 2max . Our skeletal muscle transcriptomics elicited no molecular targets, whereas gene networks suggestive of influencing maximal stroke volume were identified in the left ventricle transcriptomics ( Ruegsegger et al. 2017 ).

Publications concerning the effects of exercise on the brain (from 54 to 216 papers listed on PubMed from 2007 to 2016) have increased 400%. In addition, a 2016 study ( Schuch et al. 2016 ) of three previous papers reported that humans with low- and moderate-CRF had 76% and 23%, respectively, increased risk of developing depression compared to high CRF in three publications. With this forming trend, the next section will consider exercise and brain health.

EXERCISE IMPROVES MENTAL HEALTH

Many studies support physical activity as a noninvasive therapy for mental health improvements in cognition ( Beier et al. 2014 ; Bielak et al. 2014 ; Tian et al. 2014 ), depression ( Kratz et al. 2014 ; McKercher et al. 2014 ; Mura et al. 2014 ), anxiety ( Greenwood et al. 2012 ; Nishijima et al. 2013 ; Schoenfeld et al. 2013 ), neurodegenerative diseases (i.e., Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease) ( Bjerring and Arendt-Nielsen 1990 ; Mattson 2014 ), and drug addiction ( Zlebnik et al. 2012 ; Lynch et al. 2013 ; Peterson et al. 2014 ). In 1999, van Praag et al. (1999) showed the survival of newborn cells in the adult mouse dentate gyrus, a hippocampal region important for spatial recognition, is enhanced by voluntary wheel running. Similarly, spatial pattern separation and neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus are strongly correlated in 3-mo-old mice following 10 wk of voluntary wheel running ( Creer et al. 2010 ), and the development of new neurons in the dentate gyrus is coupled with the formation of new blood vessels ( Pereira et al. 2007 ). Many exercise-related improvements in cognitive function have been associated with local and systemic expression of growth factors in the hippocampus, notably, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) ( Neeper et al. 1995 ; Cotman and Berchtold 2002 ). BDNF promotes many developmental functions in the brain, including neuronal cell survival, differentiation, migration, dendritic arborization, and synaptic plasticity ( Park and Poo 2013 ). In rat hippocampus, regular exercise promotes a progressive increase in BDNF protein for up to at least 3 mo ( Berchtold et al. 2005 ). In an opposite manner, BDNF mRNA in the hippocampus is rapidly decreased by the cessation of wheel running, suggesting BDNF expression is tightly related to exercise volume ( Widenfalk et al. 1999 ).

Findings by Wrann et al. (2013) highlight one mechanism by which endurance exercise may up-regulate BDNF expression. To summarize, Wrann et al. (2013) noted that exercise increases the activity of the estrogen-related receptor α (ERRα)/peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) complex, in turn increasing levels of the exercise-secreted factor FNDC5 in skeletal muscle and the hippocampus, whose cleavage products provide beneficial effects in the hippocampus by increasing BDNF gene expression. While future research should determine whether the FNDC5 cleavage-product was produced locally in hippocampal neurons or was secreted into the circulation, this finding eloquently displays one mechanism responsible for brain health benefits following exercise. Similarly, work by van Praag and colleagues suggests that exercise or pharmacological activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in skeletal muscle enhances indices of learning and memory, neurogenesis, and gene expression related to mitochondrial function in the hippocampus ( Kobilo et al. 2011 , 2014 ; Guerrieri and van Praag 2015 ).

Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), is central to many exercise-induced adaptations in the brain. Like BDNF, physical activity increases circulatory IGF-1 levels and both exercise and infusion of IGF-1 increase BrdU + cell number and survivability in the hippocampus ( Trejo et al. 2001 ). Similarly, the protective effects of exercise on various brain lesions are nullified by anti-IGF-1 antibody ( Carro et al. 2001 ).

In 1979, Greist et al. (1979) provided evidence that running reduced depression symptoms similarly to psychotherapy. However, the precise mechanisms by which exercise prevents and/or treats depression remain largely unknown. Of the proposed mechanisms, increases in the availability of brain neurotransmitters and neurotrophic factors (e.g., BDNF, dopamine, glutamate, norepinephrine, serotonin) are perhaps the best studied. For example, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) activity, the rate-limiting enzyme in dopamine formation, in the striatum, an area of the brain's reward system, is increased following 7 days of treadmill running in an intensity-dependent manner ( Hattori et al. 1994 ). Voluntary wheel running is also highly rewarding in rats, and voluntary wheel running in rats lowers the motivation to self-administer cocaine, suggesting exercise may be a viable strategy in the fight against drug addiction ( Larson and Carroll 2005 ).

Similar to the above examples, secreted factors from skeletal muscle have been linked to the regulation of depression. Agudelo et al. (2014) showed that exercise training in mice and humans, and overexpression of skeletal muscle PGC-1α1, leads to robust increases in kynurenine amino transferase (KAT) expression in skeletal muscle, an enzyme whose activity protects from stress-induced increases in depression in the brain by converting kynurenine into kynurenic acid. Additionally, overexpression of PGC-1α1 in skeletal muscle left mice resistant to stress, as evaluated by various behavioral assays indicative of depression ( Agudelo et al. 2014 ). Simultaneously, they report gene expression related to synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus, such as BDNF and CamkII, were unaffected by chronic mild stress compared to wild-type mice. Collectively, these findings suggest exercise-induced increases in skeletal muscle PGC-1α1 may be an important regulator of KAT expression in skeletal muscle, which, via modulation in plasma kynurenine levels, may alleviate stress-induced depression and promote hippocampal neuronal plasticity.

TYPE 2 DIABETES, MITOCHONDRIA, AND EXERCISE

T2d predictions show a pandemic.

In a 2001 Diabetes Care article ( Boyle et al. 2001 ), investigators at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) predicted 29 million U.S. cases of T2D would be present in 2050. Unfortunately, the 2001 prediction of 29 million was reached in 2012! For 2012, the American Diabetes Association reported that 29 million Americans had diagnosed and undiagnosed T2D, which was 9% of the American population ( Dwyer-Lindgren et al. 2016 ). More rapid increases in T2D are now predicted by the CDC than in the previous estimate. The CDC now predicts a doubling or tripling in T2D in 2050. The tripling would mean that one out of three U.S. adults would have T2D in their lifetime by 2050 ( Boyle et al. 2010 ), which would be >100 million U.S. cases. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) reports T2D cases worldwide. In 2015, the IDF reported that 344 and 416 million North American (including Caribbean) and worldwide adults, respectively, had T2D. Furthermore, the IDF predicts for 2040 that 413 and 642 million, respectively, will have T2D. In sum, T2D is now pandemic, and the pandemic will increase in numbers without current apparent action within the general public.

Type 2 Diabetes Prevalence Is Based on a Strong Genetic Predisposition

The Framingham study found that T2D risk in offspring was 3.5-fold and sixfold higher for a single and two diabetic parent(s), respectively, as compared to nondiabetic offspring ( Meigs et al. 2000 ). Thus, T2D is gene-based.

Noncoding regions of the human genome contain >90% of the >100 variants associated with both T2D and related traits that were observed in genome-wide association studies ( Scott et al. 2016 ). Another 2016 paper ( Kwak and Park 2016 ) lists at least 75 independent genetic loci that are associated with T2D. Taken together, T2D is a complex genetic disease ( Scott et al. 2016 ).

Type 2 Diabetes Is Modulated by Lifestyle, with Exercise as the More Powerful Lifestyle Factor