Literature Syntheis 101

How To Synthesise The Existing Research (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | August 2023

One of the most common mistakes that students make when writing a literature review is that they err on the side of describing the existing literature rather than providing a critical synthesis of it. In this post, we’ll unpack what exactly synthesis means and show you how to craft a strong literature synthesis using practical examples.

This post is based on our popular online course, Literature Review Bootcamp . In the course, we walk you through the full process of developing a literature review, step by step. If it’s your first time writing a literature review, you definitely want to use this link to get 50% off the course (limited-time offer).

Overview: Literature Synthesis

- What exactly does “synthesis” mean?

- Aspect 1: Agreement

- Aspect 2: Disagreement

- Aspect 3: Key theories

- Aspect 4: Contexts

- Aspect 5: Methodologies

- Bringing it all together

What does “synthesis” actually mean?

As a starting point, let’s quickly define what exactly we mean when we use the term “synthesis” within the context of a literature review.

Simply put, literature synthesis means going beyond just describing what everyone has said and found. Instead, synthesis is about bringing together all the information from various sources to present a cohesive assessment of the current state of knowledge in relation to your study’s research aims and questions .

Put another way, a good synthesis tells the reader exactly where the current research is “at” in terms of the topic you’re interested in – specifically, what’s known , what’s not , and where there’s a need for more research .

So, how do you go about doing this?

Well, there’s no “one right way” when it comes to literature synthesis, but we’ve found that it’s particularly useful to ask yourself five key questions when you’re working on your literature review. Having done so, you can then address them more articulately within your actual write up. So, let’s take a look at each of these questions.

1. Points Of Agreement

The first question that you need to ask yourself is: “Overall, what things seem to be agreed upon by the vast majority of the literature?”

For example, if your research aim is to identify which factors contribute toward job satisfaction, you’ll need to identify which factors are broadly agreed upon and “settled” within the literature. Naturally, there may at times be some lone contrarian that has a radical viewpoint , but, provided that the vast majority of researchers are in agreement, you can put these random outliers to the side. That is, of course, unless your research aims to explore a contrarian viewpoint and there’s a clear justification for doing so.

Identifying what’s broadly agreed upon is an essential starting point for synthesising the literature, because you generally don’t want (or need) to reinvent the wheel or run down a road investigating something that is already well established . So, addressing this question first lays a foundation of “settled” knowledge.

Need a helping hand?

2. Points Of Disagreement

Related to the previous point, but on the other end of the spectrum, is the equally important question: “Where do the disagreements lie?” .

In other words, which things are not well agreed upon by current researchers? It’s important to clarify here that by disagreement, we don’t mean that researchers are (necessarily) fighting over it – just that there are relatively mixed findings within the empirical research , with no firm consensus amongst researchers.

This is a really important question to address as these “disagreements” will often set the stage for the research gap(s). In other words, they provide clues regarding potential opportunities for further research, which your study can then (hopefully) contribute toward filling. If you’re not familiar with the concept of a research gap, be sure to check out our explainer video covering exactly that .

3. Key Theories

The next question you need to ask yourself is: “Which key theories seem to be coming up repeatedly?” .

Within most research spaces, you’ll find that you keep running into a handful of key theories that are referred to over and over again. Apart from identifying these theories, you’ll also need to think about how they’re connected to each other. Specifically, you need to ask yourself:

- Are they all covering the same ground or do they have different focal points or underlying assumptions ?

- Do some of them feed into each other and if so, is there an opportunity to integrate them into a more cohesive theory?

- Do some of them pull in different directions ? If so, why might this be?

- Do all of the theories define the key concepts and variables in the same way, or is there some disconnect? If so, what’s the impact of this ?

Simply put, you’ll need to pay careful attention to the key theories in your research area, as they will need to feature within your theoretical framework , which will form a critical component within your final literature review. This will set the foundation for your entire study, so it’s essential that you be critical in this area of your literature synthesis.

If this sounds a bit fluffy, don’t worry. We deep dive into the theoretical framework (as well as the conceptual framework) and look at practical examples in Literature Review Bootcamp . If you’d like to learn more, take advantage of our limited-time offer to get 60% off the standard price.

4. Contexts

The next question that you need to address in your literature synthesis is an important one, and that is: “Which contexts have (and have not) been covered by the existing research?” .

For example, sticking with our earlier hypothetical topic (factors that impact job satisfaction), you may find that most of the research has focused on white-collar , management-level staff within a primarily Western context, but little has been done on blue-collar workers in an Eastern context. Given the significant socio-cultural differences between these two groups, this is an important observation, as it could present a contextual research gap .

In practical terms, this means that you’ll need to carefully assess the context of each piece of literature that you’re engaging with, especially the empirical research (i.e., studies that have collected and analysed real-world data). Ideally, you should keep notes regarding the context of each study in some sort of catalogue or sheet, so that you can easily make sense of this before you start the writing phase. If you’d like, our free literature catalogue worksheet is a great tool for this task.

5. Methodological Approaches

Last but certainly not least, you need to ask yourself the question: “What types of research methodologies have (and haven’t) been used?”

For example, you might find that most studies have approached the topic using qualitative methods such as interviews and thematic analysis. Alternatively, you might find that most studies have used quantitative methods such as online surveys and statistical analysis.

But why does this matter?

Well, it can run in one of two potential directions . If you find that the vast majority of studies use a specific methodological approach, this could provide you with a firm foundation on which to base your own study’s methodology . In other words, you can use the methodologies of similar studies to inform (and justify) your own study’s research design .

On the other hand, you might argue that the lack of diverse methodological approaches presents a research gap , and therefore your study could contribute toward filling that gap by taking a different approach. For example, taking a qualitative approach to a research area that is typically approached quantitatively. Of course, if you’re going to go against the methodological grain, you’ll need to provide a strong justification for why your proposed approach makes sense. Nevertheless, it is something worth at least considering.

Regardless of which route you opt for, you need to pay careful attention to the methodologies used in the relevant studies and provide at least some discussion about this in your write-up. Again, it’s useful to keep track of this on some sort of spreadsheet or catalogue as you digest each article, so consider grabbing a copy of our free literature catalogue if you don’t have anything in place.

Bringing It All Together

Alright, so we’ve looked at five important questions that you need to ask (and answer) to help you develop a strong synthesis within your literature review. To recap, these are:

- Which things are broadly agreed upon within the current research?

- Which things are the subject of disagreement (or at least, present mixed findings)?

- Which theories seem to be central to your research topic and how do they relate or compare to each other?

- Which contexts have (and haven’t) been covered?

- Which methodological approaches are most common?

Importantly, you’re not just asking yourself these questions for the sake of asking them – they’re not just a reflection exercise. You need to weave your answers to them into your actual literature review when you write it up. How exactly you do this will vary from project to project depending on the structure you opt for, but you’ll still need to address them within your literature review, whichever route you go.

The best approach is to spend some time actually writing out your answers to these questions, as opposed to just thinking about them in your head. Putting your thoughts onto paper really helps you flesh out your thinking . As you do this, don’t just write down the answers – instead, think about what they mean in terms of the research gap you’ll present , as well as the methodological approach you’ll take . Your literature synthesis needs to lay the groundwork for these two things, so it’s essential that you link all of it together in your mind, and of course, on paper.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling Udemy Course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

excellent , thank you

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- University of Oregon Libraries

- Research Guides

How to Write a Literature Review

- 6. Synthesize

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Reading Journal Articles

- Does it Describe a Literature Review?

- 1. Identify the Question

- 2. Review Discipline Styles

- Searching Article Databases

- Finding Full-Text of an Article

- Citation Chaining

- When to Stop Searching

- 4. Manage Your References

- 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

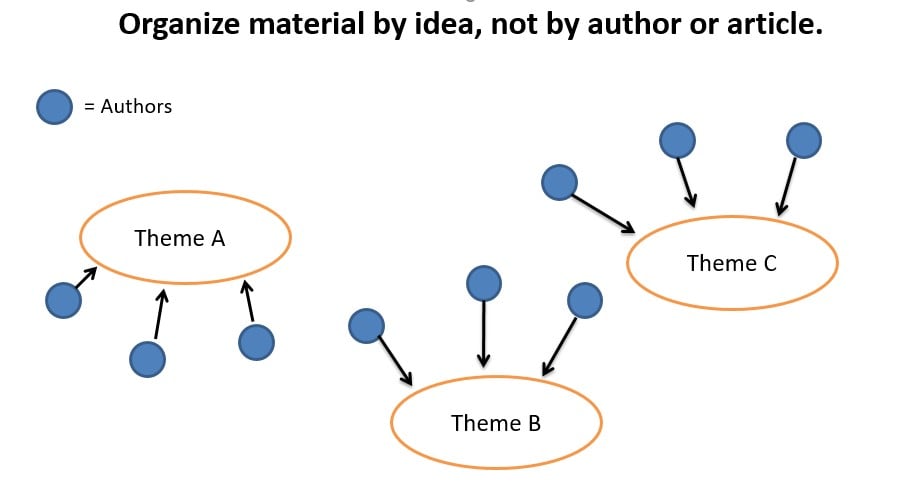

Synthesis Visualization

Synthesis matrix example.

- 7. Write a Literature Review

- Synthesis Worksheet

About Synthesis

Approaches to synthesis.

You can sort the literature in various ways, for example:

How to Begin?

Read your sources carefully and find the main idea(s) of each source

Look for similarities in your sources – which sources are talking about the same main ideas? (for example, sources that discuss the historical background on your topic)

Use the worksheet (above) or synthesis matrix (below) to get organized

This work can be messy. Don't worry if you have to go through a few iterations of the worksheet or matrix as you work on your lit review!

Four Examples of Student Writing

In the four examples below, only ONE shows a good example of synthesis: the fourth column, or Student D . For a web accessible version, click the link below the image.

Long description of "Four Examples of Student Writing" for web accessibility

- Download a copy of the "Four Examples of Student Writing" chart

Click on the example to view the pdf.

From Jennifer Lim

- << Previous: 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

- Next: 7. Write a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Jan 10, 2024 4:46 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.uoregon.edu/litreview

Contact Us Library Accessibility UO Libraries Privacy Notices and Procedures

1501 Kincaid Street Eugene, OR 97403 P: 541-346-3053 F: 541-346-3485

- Visit us on Facebook

- Visit us on Twitter

- Visit us on Youtube

- Visit us on Instagram

- Report a Concern

- Nondiscrimination and Title IX

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Find People

The Sheridan Libraries

- Write a Literature Review

- Sheridan Libraries

- Find This link opens in a new window

- Evaluate This link opens in a new window

Get Organized

- Lit Review Prep Use this template to help you evaluate your sources, create article summaries for an annotated bibliography, and a synthesis matrix for your lit review outline.

Synthesize your Information

Synthesize: combine separate elements to form a whole.

Synthesis Matrix

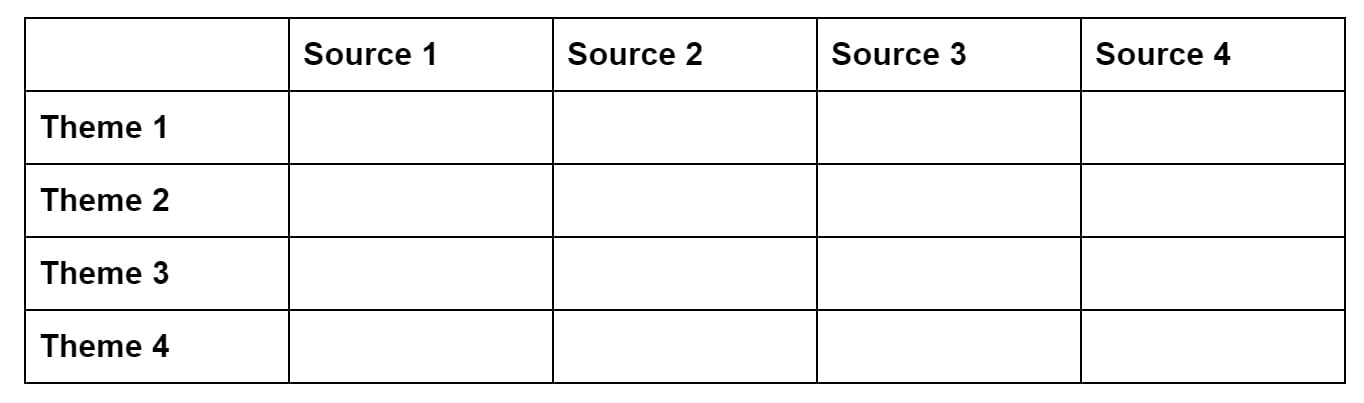

A synthesis matrix helps you record the main points of each source and document how sources relate to each other.

After summarizing and evaluating your sources, arrange them in a matrix or use a citation manager to help you see how they relate to each other and apply to each of your themes or variables.

By arranging your sources by theme or variable, you can see how your sources relate to each other, and can start thinking about how you weave them together to create a narrative.

- Step-by-Step Approach

- Example Matrix from NSCU

- Matrix Template

- << Previous: Summarize

- Next: Integrate >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 10:25 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.jhu.edu/lit-review

Encyclopedia of Evidence in Pharmaceutical Public Health and Health Services Research in Pharmacy pp 1–15 Cite as

Methodological Approaches to Literature Review

- Dennis Thomas 2 ,

- Elida Zairina 3 &

- Johnson George 4

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 09 May 2023

436 Accesses

The literature review can serve various functions in the contexts of education and research. It aids in identifying knowledge gaps, informing research methodology, and developing a theoretical framework during the planning stages of a research study or project, as well as reporting of review findings in the context of the existing literature. This chapter discusses the methodological approaches to conducting a literature review and offers an overview of different types of reviews. There are various types of reviews, including narrative reviews, scoping reviews, and systematic reviews with reporting strategies such as meta-analysis and meta-synthesis. Review authors should consider the scope of the literature review when selecting a type and method. Being focused is essential for a successful review; however, this must be balanced against the relevance of the review to a broad audience.

- Literature review

- Systematic review

- Meta-analysis

- Scoping review

- Research methodology

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Akobeng AK. Principles of evidence based medicine. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(8):837–40.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Alharbi A, Stevenson M. Refining Boolean queries to identify relevant studies for systematic review updates. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(11):1658–66.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Article Google Scholar

Aromataris E MZE. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. 2020.

Google Scholar

Aromataris E, Pearson A. The systematic review: an overview. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(3):53–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Aromataris E, Riitano D. Constructing a search strategy and searching for evidence. A guide to the literature search for a systematic review. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(5):49–56.

Babineau J. Product review: covidence (systematic review software). J Canad Health Libr Assoc Canada. 2014;35(2):68–71.

Baker JD. The purpose, process, and methods of writing a literature review. AORN J. 2016;103(3):265–9.

Bastian H, Glasziou P, Chalmers I. Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLoS Med. 2010;7(9):e1000326.

Bramer WM, Rethlefsen ML, Kleijnen J, Franco OH. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: a prospective exploratory study. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):1–12.

Brown D. A review of the PubMed PICO tool: using evidence-based practice in health education. Health Promot Pract. 2020;21(4):496–8.

Cargo M, Harris J, Pantoja T, et al. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series – paper 4: methods for assessing evidence on intervention implementation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:59–69.

Cook DJ, Mulrow CD, Haynes RB. Systematic reviews: synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(5):376–80.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Counsell C. Formulating questions and locating primary studies for inclusion in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(5):380–7.

Cummings SR, Browner WS, Hulley SB. Conceiving the research question and developing the study plan. In: Cummings SR, Browner WS, Hulley SB, editors. Designing Clinical Research: An Epidemiological Approach. 4th ed. Philadelphia (PA): P Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. p. 14–22.

Eriksen MB, Frandsen TF. The impact of patient, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) as a search strategy tool on literature search quality: a systematic review. JMLA. 2018;106(4):420.

Ferrari R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Writing. 2015;24(4):230–5.

Flemming K, Booth A, Hannes K, Cargo M, Noyes J. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series – paper 6: reporting guidelines for qualitative, implementation, and process evaluation evidence syntheses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:79–85.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med. 2006;5(3):101–17.

Gregory AT, Denniss AR. An introduction to writing narrative and systematic reviews; tasks, tips and traps for aspiring authors. Heart Lung Circ. 2018;27(7):893–8.

Harden A, Thomas J, Cargo M, et al. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series – paper 5: methods for integrating qualitative and implementation evidence within intervention effectiveness reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:70–8.

Harris JL, Booth A, Cargo M, et al. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series – paper 2: methods for question formulation, searching, and protocol development for qualitative evidence synthesis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:39–48.

Higgins J, Thomas J. In: Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3, updated February 2022). Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.: Cochrane; 2022.

International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO). Available from https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ .

Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G. Five steps to conducting a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2003;96(3):118–21.

Landhuis E. Scientific literature: information overload. Nature. 2016;535(7612):457–8.

Lockwood C, Porritt K, Munn Z, Rittenmeyer L, Salmond S, Bjerrum M, Loveday H, Carrier J, Stannard D. Chapter 2: Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global . https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-03 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Lorenzetti DL, Topfer L-A, Dennett L, Clement F. Value of databases other than medline for rapid health technology assessments. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2014;30(2):173–8.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for (SR) and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;6:264–9.

Mulrow CD. Systematic reviews: rationale for systematic reviews. BMJ. 1994;309(6954):597–9.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.

Munthe-Kaas HM, Glenton C, Booth A, Noyes J, Lewin S. Systematic mapping of existing tools to appraise methodological strengths and limitations of qualitative research: first stage in the development of the CAMELOT tool. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):1–13.

Murphy CM. Writing an effective review article. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8(2):89–90.

NHMRC. Guidelines for guidelines: assessing risk of bias. Available at https://nhmrc.gov.au/guidelinesforguidelines/develop/assessing-risk-bias . Last published 29 August 2019. Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

Noyes J, Booth A, Cargo M, et al. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series – paper 1: introduction. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018b;97:35–8.

Noyes J, Booth A, Flemming K, et al. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series – paper 3: methods for assessing methodological limitations, data extraction and synthesis, and confidence in synthesized qualitative findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018a;97:49–58.

Noyes J, Booth A, Moore G, Flemming K, Tunçalp Ö, Shakibazadeh E. Synthesising quantitative and qualitative evidence to inform guidelines on complex interventions: clarifying the purposes, designs and outlining some methods. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(Suppl 1):e000893.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Healthcare. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Polanin JR, Pigott TD, Espelage DL, Grotpeter JK. Best practice guidelines for abstract screening large-evidence systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Res Synth Methods. 2019;10(3):330–42.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(1):1–7.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. Brit Med J. 2017;358

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Br Med J. 2016;355

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12.

Tawfik GM, Dila KAS, Mohamed MYF, et al. A step by step guide for conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis with simulation data. Trop Med Health. 2019;47(1):1–9.

The Critical Appraisal Program. Critical appraisal skills program. Available at https://casp-uk.net/ . 2022. Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

The University of Melbourne. Writing a literature review in Research Techniques 2022. Available at https://students.unimelb.edu.au/academic-skills/explore-our-resources/research-techniques/reviewing-the-literature . Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

The Writing Center University of Winconsin-Madison. Learn how to write a literature review in The Writer’s Handbook – Academic Professional Writing. 2022. Available at https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/reviewofliterature/ . Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

Thompson SG, Sharp SJ. Explaining heterogeneity in meta-analysis: a comparison of methods. Stat Med. 1999;18(20):2693–708.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16(1):15.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Yoneoka D, Henmi M. Clinical heterogeneity in random-effect meta-analysis: between-study boundary estimate problem. Stat Med. 2019;38(21):4131–45.

Yuan Y, Hunt RH. Systematic reviews: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(5):1086–92.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre of Excellence in Treatable Traits, College of Health, Medicine and Wellbeing, University of Newcastle, Hunter Medical Research Institute Asthma and Breathing Programme, Newcastle, NSW, Australia

Dennis Thomas

Department of Pharmacy Practice, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

Elida Zairina

Centre for Medicine Use and Safety, Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Monash University, Parkville, VIC, Australia

Johnson George

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Johnson George .

Section Editor information

College of Pharmacy, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar

Derek Charles Stewart

Department of Pharmacy, University of Huddersfield, Huddersfield, United Kingdom

Zaheer-Ud-Din Babar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Thomas, D., Zairina, E., George, J. (2023). Methodological Approaches to Literature Review. In: Encyclopedia of Evidence in Pharmaceutical Public Health and Health Services Research in Pharmacy. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50247-8_57-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50247-8_57-1

Received : 22 February 2023

Accepted : 22 February 2023

Published : 09 May 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-50247-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-50247-8

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Biomedicine and Life Sciences Reference Module Biomedical and Life Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Holiday opening hours

Opening hours for our libraries and Library Chat have been adjusted over the Easter holidays. Please check our library opening hours page before you visit.

Which review is that? A guide to review types.

- Which review is that?

- Review Comparison Chart

- Decision Tool

- Critical Review

- Integrative Review

- Narrative Review

- State of the Art Review

- Narrative Summary

- Systematic Review

- Meta-analysis

- Comparative Effectiveness Review

- Diagnostic Systematic Review

- Network Meta-analysis

- Prognostic Review

- Psychometric Review

- Review of Economic Evaluations

- Systematic Review of Epidemiology Studies

- Living Systematic Reviews

- Umbrella Review

- Review of Reviews

- Rapid Review

- Rapid Evidence Assessment

- Rapid Realist Review

- Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

- Qualitative Interpretive Meta-synthesis

- Qualitative Meta-synthesis

- Qualitative Research Synthesis

- Framework Synthesis - Best-fit Framework Synthesis

- Meta-aggregation

- Meta-ethnography

- Meta-interpretation

- Meta-narrative Review

- Meta-summary

- Thematic Synthesis

- Mixed Methods Synthesis

- Narrative Synthesis

- Bayesian Meta-analysis

- EPPI-Centre Review

Critical Interpretive Synthesis

- Realist Synthesis - Realist Review

- Scoping Review

- Mapping Review

- Systematised Review

- Concept Synthesis

- Expert Opinion - Policy Review

- Technology Assessment Review

- Methodological Review

- Systematic Search and Review

"Critical interpretive synthesis involves an iterative approach to refining the research question and searching and selecting from the literature (using theoretical sampling) and defining and applying codes and categories. It also has a particular approach to appraising quality, using relevance – i.e. likely contribution to theory development – rather than methodological characteristics as a means of determining the 'quality' of individual papers" (Barnett-Page et al, 2009).

Further Reading/Resources

Chalmiers, M. A., Karaki, F., Muriki, M., Mody, S., Chen, A., & de Bocanegra, H. T. (2021). Refugee women's experiences with contraceptive care after resettlement in high-income countries: A Critical Interpretive Synthesis. Contraception . Full Text

References Barnett-Page, E., & Thomas, J. (2009). Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC medical research methodology , 9 (1), 1-11. Full Text

- << Previous: EPPI-Centre Review

- Next: Realist Synthesis - Realist Review >>

- Last Updated: Mar 5, 2024 1:14 PM

- URL: https://unimelb.libguides.com/whichreview

Library Guides

Literature reviews: synthesis.

- Criticality

Synthesise Information

So, how can you create paragraphs within your literature review that demonstrates your knowledge of the scholarship that has been done in your field of study?

You will need to present a synthesis of the texts you read.

Doug Specht, Senior Lecturer at the Westminster School of Media and Communication, explains synthesis for us in the following video:

Synthesising Texts

What is synthesis?

Synthesis is an important element of academic writing, demonstrating comprehension, analysis, evaluation and original creation.

With synthesis you extract content from different sources to create an original text. While paraphrase and summary maintain the structure of the given source(s), with synthesis you create a new structure.

The sources will provide different perspectives and evidence on a topic. They will be put together when agreeing, contrasted when disagreeing. The sources must be referenced.

Perfect your synthesis by showing the flow of your reasoning, expressing critical evaluation of the sources and drawing conclusions.

When you synthesise think of "using strategic thinking to resolve a problem requiring the integration of diverse pieces of information around a structuring theme" (Mateos and Sole 2009, p448).

Synthesis is a complex activity, which requires a high degree of comprehension and active engagement with the subject. As you progress in higher education, so increase the expectations on your abilities to synthesise.

How to synthesise in a literature review:

Identify themes/issues you'd like to discuss in the literature review. Think of an outline.

Read the literature and identify these themes/issues.

Critically analyse the texts asking: how does the text I'm reading relate to the other texts I've read on the same topic? Is it in agreement? Does it differ in its perspective? Is it stronger or weaker? How does it differ (could be scope, methods, year of publication etc.). Draw your conclusions on the state of the literature on the topic.

Start writing your literature review, structuring it according to the outline you planned.

Put together sources stating the same point; contrast sources presenting counter-arguments or different points.

Present your critical analysis.

Always provide the references.

The best synthesis requires a "recursive process" whereby you read the source texts, identify relevant parts, take notes, produce drafts, re-read the source texts, revise your text, re-write... (Mateos and Sole, 2009).

What is good synthesis?

The quality of your synthesis can be assessed considering the following (Mateos and Sole, 2009, p439):

Integration and connection of the information from the source texts around a structuring theme.

Selection of ideas necessary for producing the synthesis.

Appropriateness of the interpretation.

Elaboration of the content.

Example of Synthesis

Original texts (fictitious):

Synthesis:

Animal experimentation is a subject of heated debate. Some argue that painful experiments should be banned. Indeed it has been demonstrated that such experiments make animals suffer physically and psychologically (Chowdhury 2012; Panatta and Hudson 2016). On the other hand, it has been argued that animal experimentation can save human lives and reduce harm on humans (Smith 2008). This argument is only valid for toxicological testing, not for tests that, for example, merely improve the efficacy of a cosmetic (Turner 2015). It can be suggested that animal experimentation should be regulated to only allow toxicological risk assessment, and the suffering to the animals should be minimised.

Bibliography

Mateos, M. and Sole, I. (2009). Synthesising Information from various texts: A Study of Procedures and Products at Different Educational Levels. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 24 (4), 435-451. Available from https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03178760 [Accessed 29 June 2021].

- << Previous: Structure

- Next: Criticality >>

- Last Updated: Nov 18, 2023 10:56 PM

- URL: https://libguides.westminster.ac.uk/literature-reviews

CONNECT WITH US

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

Online Guide to Writing and Research

Thinking strategies and writing patterns, explore more of umgc.

- Online Guide to Writing

Critical Strategies and Writing

One of the basic academic writing activities is researching your topic and what others have said about it. Your goal should be to draw thoughts, observations, and claims about your topic from your research. We call this process of drawing from multiple sources “ synthesis .” Click on the accordion items below for more information.

Definition, Use, and Sample Synthesis

Synthesis defined.

Synthesis Emerges from Analysis

Synthesis emerges from analytical activities we discussed on the previous page: comparative analysis and analysis for cause and effect . For example, to communicate where scholars agree and where they disagree, one must analyze their work for similarities and differences. Also crucial for understanding scholarly discourse is understanding how a particular work of scholarship shapes the scholarship of others, causing them to head in new directions.

When Should Synthesis Be Used?

When to Use Synthesis

Many college assignments require synthesis. A literature review, for example, requires that you make explanatory claims regarding a body of research. These should go beyond summary (mere description) to provide helpful characterizations that aid in understanding. Literature reviews can stand on their own, but often they are a part of a research paper, and research papers are where you will probably use synthesis most often.

The purpose of a research paper is to derive meaning from a body of information collected through research. It is your job, as the writer, to communicate that meaning to your readers. Doing this requires that you develop an informed and educated opinion of what your research suggests about your subject. Communicating this opinion requires synthesis.

Sample Synthesis

In 1655, an embassy of Dutch Jews led by Rabbi Menassah ben Israel traveled to London to meet with the Commonwealth’s new Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell. The informal “Readmission” of Jews—who had been expelled from England by royal edict in 1290—resulting from the Whitehall conference was once hailed as a high point in the history of toleration. Yet in recent years, scholars have increasingly challenged the progressive nature of this event, both in its substance and its motivation (Kaplan 2007; Katznelson 2010; Walsham 2006) . “Toleration” in this case, as in many others, did not entail religious freedom or civic equality; Jews in England were granted legal residency and permitted to worship privately, but citizenship, public worship, and the printing of anything that “opposeth the Christian religion” remained off the cards. As for its motivation, Edward Whalley’s twofold argument was representative: the Jews “will bring in much wealth into this Commonwealth: and where wee both pray for theyre conversion and beleeve it shal be, I knowe not why wee shold deny the means” (Marshall 2006, 381–82)

(Bejan, 2015, p. 1103).

The author of the above passage, Teresa Bejan, has synthesized the work of a number of other scholars (Kaplan, Katznelson, Walsham, and Marshall) to situate her argument. Note how not all of these scholars are directly quoted, but they are cited because their work forms the basis of Bejan's work.

Key Takeaways

- Synthesizing allows you to carry an argument or stance you adopt within a paper in your own words, based on conclusions you have come to about the topic.

- Synthesizing contributes to confidence about your stance and topic.

Mailing Address: 3501 University Blvd. East, Adelphi, MD 20783 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . © 2022 UMGC. All links to external sites were verified at the time of publication. UMGC is not responsible for the validity or integrity of information located at external sites.

Table of Contents: Online Guide to Writing

Chapter 1: College Writing

How Does College Writing Differ from Workplace Writing?

What Is College Writing?

Why So Much Emphasis on Writing?

Chapter 2: The Writing Process

Doing Exploratory Research

Getting from Notes to Your Draft

Introduction

Prewriting - Techniques to Get Started - Mining Your Intuition

Prewriting: Targeting Your Audience

Prewriting: Techniques to Get Started

Prewriting: Understanding Your Assignment

Rewriting: Being Your Own Critic

Rewriting: Creating a Revision Strategy

Rewriting: Getting Feedback

Rewriting: The Final Draft

Techniques to Get Started - Outlining

Techniques to Get Started - Using Systematic Techniques

Thesis Statement and Controlling Idea

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Freewriting

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Summarizing Your Ideas

Writing: Outlining What You Will Write

Chapter 3: Thinking Strategies

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone: Style Through Vocabulary and Diction

Critical Strategies and Writing: Analysis

Critical Strategies and Writing: Evaluation

Critical Strategies and Writing: Persuasion

Critical Strategies and Writing: Synthesis

Developing a Paper Using Strategies

Kinds of Assignments You Will Write

Patterns for Presenting Information

Patterns for Presenting Information: Critiques

Patterns for Presenting Information: Discussing Raw Data

Patterns for Presenting Information: General-to-Specific Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Problem-Cause-Solution Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Specific-to-General Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Summaries and Abstracts

Supporting with Research and Examples

Writing Essay Examinations

Writing Essay Examinations: Make Your Answer Relevant and Complete

Writing Essay Examinations: Organize Thinking Before Writing

Writing Essay Examinations: Read and Understand the Question

Chapter 4: The Research Process

Planning and Writing a Research Paper

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Ask a Research Question

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Cite Sources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Collect Evidence

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Decide Your Point of View, or Role, for Your Research

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Draw Conclusions

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Find a Topic and Get an Overview

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Manage Your Resources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Outline

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Survey the Literature

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Work Your Sources into Your Research Writing

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Human Resources

Research Resources: What Are Research Resources?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Electronic Resources

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Print Resources

Structuring the Research Paper: Formal Research Structure

Structuring the Research Paper: Informal Research Structure

The Nature of Research

The Research Assignment: How Should Research Sources Be Evaluated?

The Research Assignment: When Is Research Needed?

The Research Assignment: Why Perform Research?

Chapter 5: Academic Integrity

Academic Integrity

Giving Credit to Sources

Giving Credit to Sources: Copyright Laws

Giving Credit to Sources: Documentation

Giving Credit to Sources: Style Guides

Integrating Sources

Practicing Academic Integrity

Practicing Academic Integrity: Keeping Accurate Records

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Paraphrasing Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Quoting Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Summarizing Your Sources

Types of Documentation

Types of Documentation: Bibliographies and Source Lists

Types of Documentation: Citing World Wide Web Sources

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - APA Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - CSE/CBE Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - Chicago Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - MLA Style

Types of Documentation: Note Citations

Chapter 6: Using Library Resources

Finding Library Resources

Chapter 7: Assessing Your Writing

How Is Writing Graded?

How Is Writing Graded?: A General Assessment Tool

The Draft Stage

The Draft Stage: The First Draft

The Draft Stage: The Revision Process and the Final Draft

The Draft Stage: Using Feedback

The Research Stage

Using Assessment to Improve Your Writing

Chapter 8: Other Frequently Assigned Papers

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Article and Book Reviews

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Reaction Papers

Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Adapting the Argument Structure

Writing Arguments: Purposes of Argument

Writing Arguments: References to Consult for Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Anticipate Active Opposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Determine Your Organization

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Develop Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Introduce Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - State Your Thesis or Proposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Write Your Conclusion

Writing Arguments: Types of Argument

Appendix A: Books to Help Improve Your Writing

Dictionaries

General Style Manuals

Researching on the Internet

Special Style Manuals

Writing Handbooks

Appendix B: Collaborative Writing and Peer Reviewing

Collaborative Writing: Assignments to Accompany the Group Project

Collaborative Writing: Informal Progress Report

Collaborative Writing: Issues to Resolve

Collaborative Writing: Methodology

Collaborative Writing: Peer Evaluation

Collaborative Writing: Tasks of Collaborative Writing Group Members

Collaborative Writing: Writing Plan

General Introduction

Peer Reviewing

Appendix C: Developing an Improvement Plan

Working with Your Instructor’s Comments and Grades

Appendix D: Writing Plan and Project Schedule

Devising a Writing Project Plan and Schedule

Reviewing Your Plan with Others

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

- Synthesizing Sources | Examples & Synthesis Matrix

Synthesizing Sources | Examples & Synthesis Matrix

Published on July 4, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on May 31, 2023.

Synthesizing sources involves combining the work of other scholars to provide new insights. It’s a way of integrating sources that helps situate your work in relation to existing research.

Synthesizing sources involves more than just summarizing . You must emphasize how each source contributes to current debates, highlighting points of (dis)agreement and putting the sources in conversation with each other.

You might synthesize sources in your literature review to give an overview of the field or throughout your research paper when you want to position your work in relation to existing research.

Table of contents

Example of synthesizing sources, how to synthesize sources, synthesis matrix, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about synthesizing sources.

Let’s take a look at an example where sources are not properly synthesized, and then see what can be done to improve it.

This paragraph provides no context for the information and does not explain the relationships between the sources described. It also doesn’t analyze the sources or consider gaps in existing research.

Research on the barriers to second language acquisition has primarily focused on age-related difficulties. Building on Lenneberg’s (1967) theory of a critical period of language acquisition, Johnson and Newport (1988) tested Lenneberg’s idea in the context of second language acquisition. Their research seemed to confirm that young learners acquire a second language more easily than older learners. Recent research has considered other potential barriers to language acquisition. Schepens, van Hout, and van der Slik (2022) have revealed that the difficulties of learning a second language at an older age are compounded by dissimilarity between a learner’s first language and the language they aim to acquire. Further research needs to be carried out to determine whether the difficulty faced by adult monoglot speakers is also faced by adults who acquired a second language during the “critical period.”

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

To synthesize sources, group them around a specific theme or point of contention.

As you read sources, ask:

- What questions or ideas recur? Do the sources focus on the same points, or do they look at the issue from different angles?

- How does each source relate to others? Does it confirm or challenge the findings of past research?

- Where do the sources agree or disagree?

Once you have a clear idea of how each source positions itself, put them in conversation with each other. Analyze and interpret their points of agreement and disagreement. This displays the relationships among sources and creates a sense of coherence.

Consider both implicit and explicit (dis)agreements. Whether one source specifically refutes another or just happens to come to different conclusions without specifically engaging with it, you can mention it in your synthesis either way.

Synthesize your sources using:

- Topic sentences to introduce the relationship between the sources

- Signal phrases to attribute ideas to their authors

- Transition words and phrases to link together different ideas

To more easily determine the similarities and dissimilarities among your sources, you can create a visual representation of their main ideas with a synthesis matrix . This is a tool that you can use when researching and writing your paper, not a part of the final text.

In a synthesis matrix, each column represents one source, and each row represents a common theme or idea among the sources. In the relevant rows, fill in a short summary of how the source treats each theme or topic.

This helps you to clearly see the commonalities or points of divergence among your sources. You can then synthesize these sources in your work by explaining their relationship.

If you want to know more about ChatGPT, AI tools , citation , and plagiarism , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- ChatGPT vs human editor

- ChatGPT citations

- Is ChatGPT trustworthy?

- Using ChatGPT for your studies

- What is ChatGPT?

- Chicago style

- Paraphrasing

Plagiarism

- Types of plagiarism

- Self-plagiarism

- Avoiding plagiarism

- Academic integrity

- Consequences of plagiarism

- Common knowledge

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

Synthesizing sources means comparing and contrasting the work of other scholars to provide new insights.

It involves analyzing and interpreting the points of agreement and disagreement among sources.

You might synthesize sources in your literature review to give an overview of the field of research or throughout your paper when you want to contribute something new to existing research.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

Topic sentences help keep your writing focused and guide the reader through your argument.

In an essay or paper , each paragraph should focus on a single idea. By stating the main idea in the topic sentence, you clarify what the paragraph is about for both yourself and your reader.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, May 31). Synthesizing Sources | Examples & Synthesis Matrix. Scribbr. Retrieved April 1, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/synthesizing-sources/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, signal phrases | definition, explanation & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, how to find sources | scholarly articles, books, etc., "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

How to Synthesize Written Information from Multiple Sources

Shona McCombes

Content Manager

B.A., English Literature, University of Glasgow

Shona McCombes is the content manager at Scribbr, Netherlands.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

When you write a literature review or essay, you have to go beyond just summarizing the articles you’ve read – you need to synthesize the literature to show how it all fits together (and how your own research fits in).

Synthesizing simply means combining. Instead of summarizing the main points of each source in turn, you put together the ideas and findings of multiple sources in order to make an overall point.

At the most basic level, this involves looking for similarities and differences between your sources. Your synthesis should show the reader where the sources overlap and where they diverge.

Unsynthesized Example

Franz (2008) studied undergraduate online students. He looked at 17 females and 18 males and found that none of them liked APA. According to Franz, the evidence suggested that all students are reluctant to learn citations style. Perez (2010) also studies undergraduate students. She looked at 42 females and 50 males and found that males were significantly more inclined to use citation software ( p < .05). Findings suggest that females might graduate sooner. Goldstein (2012) looked at British undergraduates. Among a sample of 50, all females, all confident in their abilities to cite and were eager to write their dissertations.

Synthesized Example

Studies of undergraduate students reveal conflicting conclusions regarding relationships between advanced scholarly study and citation efficacy. Although Franz (2008) found that no participants enjoyed learning citation style, Goldstein (2012) determined in a larger study that all participants watched felt comfortable citing sources, suggesting that variables among participant and control group populations must be examined more closely. Although Perez (2010) expanded on Franz’s original study with a larger, more diverse sample…

Step 1: Organize your sources

After collecting the relevant literature, you’ve got a lot of information to work through, and no clear idea of how it all fits together.

Before you can start writing, you need to organize your notes in a way that allows you to see the relationships between sources.

One way to begin synthesizing the literature is to put your notes into a table. Depending on your topic and the type of literature you’re dealing with, there are a couple of different ways you can organize this.

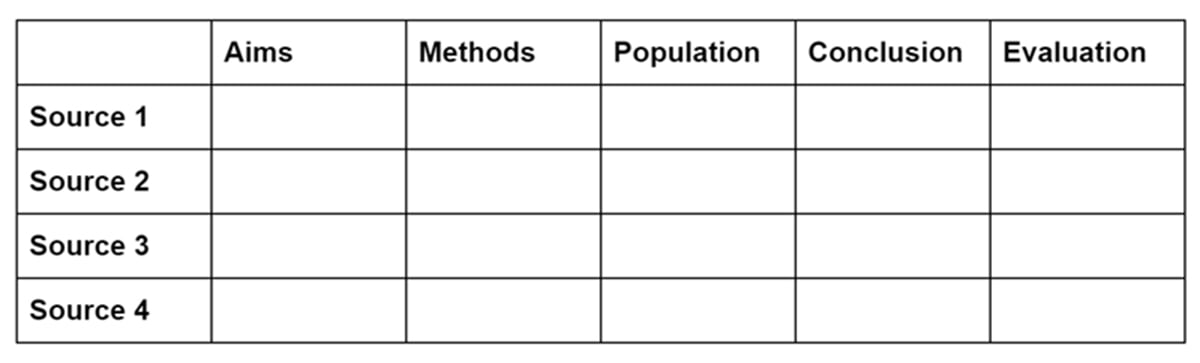

Summary table

A summary table collates the key points of each source under consistent headings. This is a good approach if your sources tend to have a similar structure – for instance, if they’re all empirical papers.

Each row in the table lists one source, and each column identifies a specific part of the source. You can decide which headings to include based on what’s most relevant to the literature you’re dealing with.

For example, you might include columns for things like aims, methods, variables, population, sample size, and conclusion.

For each study, you briefly summarize each of these aspects. You can also include columns for your own evaluation and analysis.

The summary table gives you a quick overview of the key points of each source. This allows you to group sources by relevant similarities, as well as noticing important differences or contradictions in their findings.

Synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix is useful when your sources are more varied in their purpose and structure – for example, when you’re dealing with books and essays making various different arguments about a topic.

Each column in the table lists one source. Each row is labeled with a specific concept, topic or theme that recurs across all or most of the sources.

Then, for each source, you summarize the main points or arguments related to the theme.

The purposes of the table is to identify the common points that connect the sources, as well as identifying points where they diverge or disagree.

Step 2: Outline your structure

Now you should have a clear overview of the main connections and differences between the sources you’ve read. Next, you need to decide how you’ll group them together and the order in which you’ll discuss them.

For shorter papers, your outline can just identify the focus of each paragraph; for longer papers, you might want to divide it into sections with headings.

There are a few different approaches you can take to help you structure your synthesis.

If your sources cover a broad time period, and you found patterns in how researchers approached the topic over time, you can organize your discussion chronologically .

That doesn’t mean you just summarize each paper in chronological order; instead, you should group articles into time periods and identify what they have in common, as well as signalling important turning points or developments in the literature.

If the literature covers various different topics, you can organize it thematically .

That means that each paragraph or section focuses on a specific theme and explains how that theme is approached in the literature.

Source Used with Permission: The Chicago School

If you’re drawing on literature from various different fields or they use a wide variety of research methods, you can organize your sources methodologically .

That means grouping together studies based on the type of research they did and discussing the findings that emerged from each method.

If your topic involves a debate between different schools of thought, you can organize it theoretically .

That means comparing the different theories that have been developed and grouping together papers based on the position or perspective they take on the topic, as well as evaluating which arguments are most convincing.

Step 3: Write paragraphs with topic sentences

What sets a synthesis apart from a summary is that it combines various sources. The easiest way to think about this is that each paragraph should discuss a few different sources, and you should be able to condense the overall point of the paragraph into one sentence.

This is called a topic sentence , and it usually appears at the start of the paragraph. The topic sentence signals what the whole paragraph is about; every sentence in the paragraph should be clearly related to it.

A topic sentence can be a simple summary of the paragraph’s content:

“Early research on [x] focused heavily on [y].”

For an effective synthesis, you can use topic sentences to link back to the previous paragraph, highlighting a point of debate or critique:

“Several scholars have pointed out the flaws in this approach.” “While recent research has attempted to address the problem, many of these studies have methodological flaws that limit their validity.”

By using topic sentences, you can ensure that your paragraphs are coherent and clearly show the connections between the articles you are discussing.

As you write your paragraphs, avoid quoting directly from sources: use your own words to explain the commonalities and differences that you found in the literature.

Don’t try to cover every single point from every single source – the key to synthesizing is to extract the most important and relevant information and combine it to give your reader an overall picture of the state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 4: Revise, edit and proofread

Like any other piece of academic writing, synthesizing literature doesn’t happen all in one go – it involves redrafting, revising, editing and proofreading your work.

Checklist for Synthesis

- Do I introduce the paragraph with a clear, focused topic sentence?

- Do I discuss more than one source in the paragraph?

- Do I mention only the most relevant findings, rather than describing every part of the studies?

- Do I discuss the similarities or differences between the sources, rather than summarizing each source in turn?

- Do I put the findings or arguments of the sources in my own words?

- Is the paragraph organized around a single idea?

- Is the paragraph directly relevant to my research question or topic?

- Is there a logical transition from this paragraph to the next one?

Further Information

How to Synthesise: a Step-by-Step Approach

Help…I”ve Been Asked to Synthesize!

Learn how to Synthesise (combine information from sources)

How to write a Psychology Essay

- Technical advance

- Open access

- Published: 26 July 2006

Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups

- Mary Dixon-Woods 1 ,

- Debbie Cavers 2 ,

- Shona Agarwal 3 ,

- Ellen Annandale 4 ,

- Antony Arthur 5 ,

- Janet Harvey 6 ,

- Ron Hsu 1 ,

- Savita Katbamna 7 ,

- Richard Olsen 7 ,

- Lucy Smith 1 ,

- Richard Riley 1 &

- Alex J Sutton 1

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 6 , Article number: 35 ( 2006 ) Cite this article

105k Accesses

1058 Citations

49 Altmetric

Metrics details

Conventional systematic review techniques have limitations when the aim of a review is to construct a critical analysis of a complex body of literature. This article offers a reflexive account of an attempt to conduct an interpretive review of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups in the UK

This project involved the development and use of the method of Critical Interpretive Synthesis (CIS). This approach is sensitised to the processes of conventional systematic review methodology and draws on recent advances in methods for interpretive synthesis.

Many analyses of equity of access have rested on measures of utilisation of health services, but these are problematic both methodologically and conceptually. A more useful means of understanding access is offered by the synthetic construct of candidacy. Candidacy describes how people's eligibility for healthcare is determined between themselves and health services. It is a continually negotiated property of individuals, subject to multiple influences arising both from people and their social contexts and from macro-level influences on allocation of resources and configuration of services. Health services are continually constituting and seeking to define the appropriate objects of medical attention and intervention, while at the same time people are engaged in constituting and defining what they understand to be the appropriate objects of medical attention and intervention. Access represents a dynamic interplay between these simultaneous, iterative and mutually reinforcing processes. By attending to how vulnerabilities arise in relation to candidacy, the phenomenon of access can be better understood, and more appropriate recommendations made for policy, practice and future research.

By innovating with existing methods for interpretive synthesis, it was possible to produce not only new methods for conducting what we have termed critical interpretive synthesis, but also a new theoretical conceptualisation of access to healthcare. This theoretical account of access is distinct from models already extant in the literature, and is the result of combining diverse constructs and evidence into a coherent whole. Both the method and the model should be evaluated in other contexts.

Peer Review reports

Like many areas of healthcare practice and policy, the literature on access to healthcare is large, diverse, and complex. It includes empirical work using both qualitative and quantitative methods; editorial comment and theoretical work; case studies; evaluative, epidemiological, trial, descriptive, sociological, psychological, management, and economics papers, as well as policy documents and political statements. "Access" itself has not been consistently defined or operationalised across the field. There are substantial adjunct literatures, including those on quality in healthcare, priority-setting, and patient satisfaction. A review of the area would be of most benefit if it were to produce a "mid-range" theoretical account of the evidence and existing theory that is neither so abstract that it lacks empirical applicability nor so specific that its explanatory scope is limited.

In this paper, we suggest that conventional systematic review methodology is ill-suited to the challenges that conducting such a review would pose, and describe the development of a new form of review which we term "Critical Interpretive Synthesis" (CIS). This approach draws is sensitised to the range of issues involved in conducting reviews that conventional systematic review methodology has identified, but draws on a distinctive tradition of qualitative inquiry, including recent interpretive approaches to review [ 1 ]. We suggest that that using CIS to synthesise a diverse body of evidence enables the generation of theory with strong explanatory power. We illustrate this briefly using an example based on synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare in the UK by socio-economically disadvantaged people.

Aggregative and interpretive reviews

Conventional systematic review developed as a specific methodology for searching for, appraising, and synthesising findings of primary studies [ 2 ]. It offers a way of systematising, rationalising, and making more explicit the processes of review, and has demonstrated considerable benefits in synthesising certain forms of evidence where the aim is to test theories, perhaps especially about "what works". It is more limited when the aim, as here, is to include many different forms of evidence with the aim of generating theory [ 3 ]. Conventional systematic review methods are thus better suited to the production of aggregative rather than interpretive syntheses.

This distinction between aggregative and interpretive syntheses, noted by Noblit and Hare in their ground-breaking book on meta-ethnography[ 1 ] allows a useful (though necessarily crude) categorisation of two principal approaches to conducting reviews [ 4 ]. Aggregative reviews are concerned with assembling and pooling data, may use techniques such as meta-analysis, and require a basic comparability between phenomena so that the data can be aggregated for analysis. Their defining characteristics are a focus on summarising data , and an assumption that the concepts (or variables) under which those data are to be summarised are largely secure and well specified. Key concepts are defined at an early stage in the review and form the categories under which the data from empirical studies are to be summarised.

Interpretive reviews, by contrast, see the essential tasks of synthesis as involving both induction and interpretation. Their primary concern is with the development of concepts and theories that integrate those concepts. An interpretive review will therefore avoid specifying concepts in advance of the synthesis. The interpretive analysis that yields the synthesis is conceptual in process and output. The product of the synthesis is not aggregations of data, but theory grounded in the studies included in the review. Although there is a tendency at present to conduct interpretive synthesis only of qualitative studies, it should in principle be possible and indeed desirable to conduct interpretive syntheses of all forms of evidence, since theory-building need not be based only on one form of evidence. Indeed, Glaser and Strauss [ 5 ] in their seminal text, included an (often forgotten) chapter on the use of quantitative data for theory-building.

Recent years have seen the emergence of a range of methods that draw on a more interpretive tradition, but these also have limitations when attempting a synthesis of a large and complex body of evidence. In general, the use to date of interpretive approaches to synthesis has been confined to the synthesis of qualitative research only [ 6 – 8 ]. Meta-ethnography, an approach in which there has been recent significant activity and innovation, has similarly been used solely to synthesise qualitative studies, and has typically been used only with small samples [ 9 – 11 ]. Few approaches have attempted to apply an interpretive approach to the whole corpus of evidence (regardless of study type) included in a review, and few have treated the literature they examine as itself an object of scrutiny, for example by questioning the ways in which the literature constructs its problematics, the nature of the assumptions on the literature draw, or what has influenced proposed solutions.

In this paper we offer a reflexive account of our attempt to conduct an interpretive synthesis of all types of evidence relevant to access to National Health Service (NHS) healthcare in the UK by potentially vulnerable groups. These groups had been defined at the outset by the funders of the project (the UK Department of Health Service Delivery and Organisation R&D Programme) as children, older people, members of minority ethnicities, men/women, and socio-economically disadvantaged people. We explain in particular our development of Critical Interpretive Synthesis as a method for conducting this review.

Formulating the review question

Conventional systematic review methodology [ 12 , 13 ] emphasises the need for review questions to be precisely formulated. A tightly focused research question allows the parameters of the review to be identified and the study selection criteria to be defined in advance, and in turn limits the amount of evidence required to address the review question.

This strategy is successful where the phenomenon of interest, the populations, interventions, and outcomes are all well specified – i.e. if the aim of the review is aggregative . For our project, it was neither possible nor desirable to specify in advance the precise review question, a priori definitions, or categories under which the data could be summarised, since one of its aims was to allow the definition of the phenomenon of access to emerge from our analysis of the literature [ 14 ]. This is not to say that we did not have a review question, only that it was not a specific hypothesis. Instead it was, as Greenhalgh and colleagues [ 15 ] describe, tentative, fuzzy and contested at the outset of the project. It did include a focus on equity and on how access, particularly for potentially vulnerable groups, can best be understood in the NHS, a health care system that is, unlike most in the world, free at the point of use.

The approach we used to further specify the review question was highly iterative, modifying the question in response to search results and findings from retrieved items. It treated, as Eakin and Mykhalovskiy [ 16 ] suggest, the question as a compass rather than an anchor, and as something that would not finally be settled until the end of the review. In the process of refining the question, we benefited from the multidisciplinary nature of our review team: this allowed a range of perspectives to be incorporated into the process, something that was also helpful and important in other elements of the review.

Searching the literature

A defining characteristic of conventional systematic review methodology is its use of explicit searching strategies, and its requirement that reviewers be able to give a clear account of how they searched for relevant evidence, such that the search methods can be reproduced. [ 2 ] Searching normally involves a range of strategies, but relies heavily on electronic bibliographic databases.

We piloted the use of a highly structured search strategy using protocol-driven searches across a range of electronic databases but, like Greenhalgh and Peacock [ 17 ] found that was this unsatisfactory. In particular, it risked missing relevant materials by failing to pick up papers that, while not ostensibly about "access", were nonetheless important to the aim of the review. We then developed a more organic process that fitted better with the emergent and exploratory nature of the review questions. This combined a number of strategies, including searching of electronic databases; searching websites; reference chaining; and contacts with experts. Crucially, we also used expertise within the team to identify relevant literature from adjacent fields not immediately or obviously relevant to the question of "access".

However, searching generated thousands of potentially relevant items – at one stage over 100,000 records. A literature of this size would clearly be unmanageable, and well exceed the capacity of the review team. We therefore redefined the aim of the searching phase. Rather than aiming for comprehensive identification and inclusion of all relevant literature, as would be required under conventional systematic review methodology, we saw the purpose of the searching phase as identifying potentially relevant papers to provide a sampling frame. Our sampling frame eventually totalled approximately 1,200 records.

Conventional systematic review methodology limits the number of papers to be included in a review by having tightly specified inclusion criteria for papers. Effectively, this strategy constructs the field to be known as having specific boundaries, defined as research that has specifically addressed the review question, used particular study designs and fulfilled the procedural requirements for the proper execution of these. Interpretive reviews might construct the field to be known rather differently, seeing the boundaries as more diffuse and ill-defined, as potentially overlapping with other fields, and as shifting as the review progresses. Nonetheless, there is a need to limit the number of papers to be included in an interpretive synthesis not least for practical reasons, including the time available. Sampling is also warranted theoretically, in that the focus in interpretive synthesis is on the development of concepts and theory rather than on exhaustive summary of all data. A number of authors [ 18 – 20 ] suggest drawing on the sampling techniques of primary qualitative research, including principles of theoretical sampling and theoretical saturation, when conducting a synthesis of qualitative literature.

For purposes of our synthesis, we used purposive sampling initially to select papers that were clearly concerned with aspects of access to healthcare, partly informed by an earlier scoping study [ 21 ] and later used theoretical sampling to add, test and elaborate the emerging analysis. Sampling therefore involved a constant dialectic process conducted concurrently with theory generation.

Determination of quality

Conventional systematic review methodology uses assessment of study quality in a number of ways. First, as indicated above, studies included in a review may be limited to particular study designs, often using a "hierarchy of evidence" approach that sees some designs (e.g. randomized controlled trials) as being more robust than others (e.g. case-control studies). Second, it is usual to devise broad inclusion criteria – for example adequate randomisation for RCTs – and to exclude studies that fail to meet these. Third, an appraisal of included studies, perhaps using a structured quality checklist, may be undertaken to allow sensitivity analyses aimed at assessing the effects of weaker papers.

Using this approach when confronted with a complex literature, including qualitative research, poses several challenges. No hierarchy of study designs exists for qualitative research. How or whether to appraise papers for inclusion in an interpretive reviews has received a great deal of attention, but there is little sign of an emergent consensus [ 22 ]. Some argue that formal appraisals of quality may not be necessary, and some argue that there is a risk of discounting important studies for the sake of "surface mistakes" [ 23 ]. Others propose that weak papers should be excluded from the review altogether, and several published syntheses of qualitative research have indeed used quality criteria to make decisions about excluding papers. [ 10 , 24 ]

We aimed to prioritise papers that appeared to be relevant, rather than particular study types or papers that met particular methodological standards. We might therefore be said to be prioritising "signal" (likely relevance) over "noise" (the inverse of methodological quality) [ 25 ]. We felt it important, for purposes of an interpretive review, that a low threshold be applied to maximise the inclusion and contribution of a wide variety of papers at the level of concepts . We therefore took a two-pronged approach to quality. First, we decided that only papers that were deemed to be fatally flawed would be excluded. Second, once in the review, the synthesis itself crucially involved judgements and interpretations of credibility and contribution, as we discuss later.