Netflix Change Management Case Study

Netflix is one of the world’s leading internet television networks with over 100 million members in 190 countries. It has a wide variety of award-winning original programming, documentaries, TV shows and feature films.

Netflix offers a subscription services to its users to watch all its content online. Now Netflix is producing its own content and also adding quality content of other producers for its users. It has become one of the popular online video streaming web portals and been on first top 50 websites globally.

But Netflix transformed itself and it embraced change with ever changing technology and business market.

What is Netflix successfully change story? How it happened and what challenges it faced to cope with change?

For this questions, we are presenting here Netflix change management case study.

This case study will explore how Netflix has successfully managed change in the past and present. It will also provide recommendations for other businesses on how to approach change management.

The story of Netflix change management

Netflix is a streaming service for movies and TV shows. It has a library of over 200,000 titles that you can watch on your phone, tablet, computer, or TV. You can also download shows to watch offline. Netflix offers a variety of plans, including a basic plan that starts at $7.99/month and a premium plan that starts at $11.99/month.

Netflix was founded in 1997 by Reed Hastings and Marc Randolph. They started the company with the intention of offering a DVD-by-mail service. In 2007, they introduced streaming, which allowed instant streaming of TV shows and movies on your computer. In 2013, they introduced the concept of ” binge watching” with the release of House of Cards, which all episodes of the first season were released at once so that viewers could watch them all in one sitting. In 2015, they launched their own production company, Netflix Originals, which produces movies and TV shows that are only available on Netflix.

Netflix has undergone several changes since it was founded. The most notable change was the introduction of streaming in 2007, which changed the way people watched TV and movies.

Netflix made two big changes since its started business. First, it introduced the subscription option in 1999 to store DVD rental. This option allows users to rent unlimited DVD rental without late fees. It was a drastic change in the business model of Netflix.

The second big change was happened in 2007, when it launched an online video streaming service. It was a highly disruptive change which completely revolutionalized the concept of watching movies and Tv shows online. Consumers also welcomed this change because this change was the need of time. Because everyone was using smartphone, laptops and computers and trend of going to cinema to watch a movie was on decline. Netflix also used social media and present its content to reach out their customers.

Netflix’s Change Management Process

Netflix’s change management process is a model for other organizations to follow. The company has a dedicated team that is responsible for managing change. This team works closely with Netflix’s engineers and product managers to ensure that changes are made in a controlled and safe manner. Netflix has also implemented a series of mechanisms to help prevent and mitigate the impact of changes. For example, all changes are assessed for risk before they are implemented. Netflix also conducts regular post-change reviews to identify any issues that may have arisen from the change. As a result of these measures, Netflix has been able to successfully manage change while minimizing disruptions to its business.

How Netflix manages organizational change forces

There are many factors that affect organizational change . But primarily these are two broad forces of organizational change: a) external and b)internal. Among the external forces there were rapid changes in technology, globalisation, social media etc. These all external factors led to organizational change at Netflix. .For instance, people’s expectation and behaviour, likes and dislikes in terms of watching content was changing due to new technology. New tools, techniques were also affecting business of movies watching and TV shows. But Netflix managed all those forces of change and responded in a big way to meet expectations of its consumers.

There were also internal forces of organizational change like new skills of employees and employees expectations, need of change in work environment, cost of business model etc. Netflix taken all these factors into consideration before going to execute change. And that’s the reason behind their successfully implementation of change.

How Netflix Uses Data to Drive Change

Netflix’s data team is made up of over 800 people, including statisticians, analysts, and engineers. Their mission is simple: “to help Netflix understand its business and the world.” To do this, they collect and process tons of data every day. This data comes from a variety of sources, including things like clickstream data (what you watch and when you watch it), surveys, social media activity, third-party research, and more.

Once all this data is collected, it’s organized and stored in a massive data warehouse. This is where things start to get really interesting. The team then uses a combination of qualitative analysis (looking at the meaning behind the numbers) and quantitative analysis (using statistical models to draw conclusions) to glean insights from the data. These insights are then used to inform everything from what new shows to green-light to which actors should star in them.

For example, let’s say the team notices that a lot of people who watch Stranger Things also tend to watch You. They might then use this information to suggest Stranger Things to people who haven’t watched it yet or recommend You to people who have finished Stranger Things and are looking for something similar. This is just one small example of how Netflix uses data to drive change within its business.

It’s clear that data plays a big role in everything Netflix does. From deciding which new shows to produce to suggesting content for individual users, data is at the heart of the company’s decision-making process. And as our watching habits continue to be tracked and analyzed, we can expect even more personalized recommendations and a more tailored streaming experience overall.

Learning from drastic changes

In order to maintain a successful business, it is important to occasionally review your company’s methods and make changes where necessary. This is especially true in today’s ever-changing marketplace. Netflix, a leading provider of streaming video content, knows this well. In 2011, the company made a drastic change to its business model that upset many of its customers. However, thanks to careful planning and execution, the change was ultimately successful and resulted in increased profits for the company.

The introduction of drastic changes can be a difficult process, but with proper planning and execution, it can be successful. Netflix provides a great example of how to successfully navigate a major change. By carefully considering the needs of its customers and taking the time to properly execute its plans, the company was able to weather the storm and come out stronger than ever before.

Final Words

Netflix is a great example of change management. Business organizations can learn from Netflix change management case study to keep up with the latest changes and trends. Netflix has been successful in managing change by using data to drive their decisions. There are multiple lessons for other business entities that how Netflix capitalised on its human resources and rightly understood needs of modern-day customers.

About The Author

Tahir Abbas

Related posts.

5 Pillars of Sustainable Organizational Change

Reasons for Organizational Restructuring

Organizational Restructuring Communication to Staff

Change Management

Whether balancing budgets, reorganizing an agency, or implementing social programs, public sector leaders frequently encounter the complexity of change. The teaching cases in this section allow students to discuss outcomes and engage in problem solving in situations where protagonists wish to enact change or must guide their colleagues or constituents through change that is already occurring.

Charting a Course for Boston: Organizing for Change

Publication Date: March 5, 2024

Boston Mayor-elect Michelle Wu was elected on the promise of systemic change. Four days after her November 2021 victory—and just eleven days before taking office—she considered how to get started delivering on her sweeping agenda. Wu...

Mayor Curtatone’s Culture of Curiosity: Building Data Capabilities at Somerville City Hall Epilogue

Publication Date: February 21, 2024

This epilogue accompanies HKS Case 2255.0. A practitioner guide, HKS Case 2255.4, accompanies this case. For sixteen years, longer than any mayor in the city’s history, Mayor Joseph Curtatone has led his hometown of Somerville,...

Mayor Curtatone’s Culture of Curiosity: Building Data Capabilities at Somerville City Hall Practitioner Guide

This practitioner guide accompanies HKS Case 2255.0. An epilogue, HKS Case 2255.1, follows this case. For sixteen years, longer than any mayor in the city’s history, Mayor Joseph Curtatone has led his hometown of Somerville,...

Mayoral Transitions: How Three Mayors Stepped into the Role, in Their Own Words

Publication Date: February 29, 2024

New mayors face distinct challenges as they assume office. In these vignettes depicting three types of mayoral transitions, explore how new leaders can make the most of their first one hundred days by asserting their authority and...

Mayor Curtatone’s Culture of Curiosity: Building Data Capabilities at Somerville City Hall

For sixteen years, longer than any mayor in the city’s history, Mayor Joseph Curtatone has led his hometown of Somerville, Massachusetts. The case begins in January 2020 when the mayor is looking ahead at his recently won,...

Confronting Constraints: Shashi Verma & Transport for London Tackle a Tough Contract Sequel

Publication Date: December 19. 2023

This sequel accompanies HKS Case 2275.0, "Conflicting Constraints: Shashi Verma &Transport for London Tackle a Tough Contract." The case introduces Shashi Verma (MPP 97) in 2006, soon after he has received a plum appointment: Director...

Confronting Constraints: Shashi Verma & Transport for London Tackle a Tough Contract

The case introduces Shashi Verma (MPP 97) in 2006, soon after he has received a plum appointment: Director of Fares and Ticketing for London's super agency, Transport for London. The centerpiece of the agency's ticketing operation was the Oyster...

Shoring Up Child Protection in Massachusetts: Commissioner Spears & the Push to Go Fast

Publication Date: July 13, 2023

In January 2015, when incoming Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker chose Linda Spears as his new Commissioner of the Department of Children and Families, he was looking for a reformer. Following the grizzly death of a child under DCF...

Evelyn Diop

Publication Date: May 30, 2023

Evelyn is a seasoned nonprofit fundraising professional with roots in the corporate world, who thrives when faced with a strategic challenge. While she had been successfully leading change as a chief development officer (CDO) at...

Confronting the Unequal Toll of Highway Expansion: Oni Blair, LINK Houston, & the Texas I-45 Debate (A)

Publication Date: April 6, 2023

In this political strategy case, Oni K. Blair, newly appointed executive director of a Houston nonprofit advocating for more equitable transportation resources, faces a challenge: how to persuade a Texas state agency to substantially...

Confronting the Unequal Toll of Highway Expansion: Oni Blair, LINK Houston, & the Texas I-45 Debate (B)

Architect, Pilot, Scale, Improve: A Framework and Toolkit for Policy Implementation

Publication Date: May 12, 2021

Successful implementation is essential for achieving policymakers’ goals and must be considered during both design and delivery. The mission of this monograph is to provide you with a framework and set of tools to achieve success. The...

Related Expertise: Culture and Change Management , Business Strategy , Corporate Strategy

Five Case Studies of Transformation Excellence

November 03, 2014 By Lars Fæste , Jim Hemerling , Perry Keenan , and Martin Reeves

In a business environment characterized by greater volatility and more frequent disruptions, companies face a clear imperative: they must transform or fall behind. Yet most transformation efforts are highly complex initiatives that take years to implement. As a result, most fall short of their intended targets—in value, timing, or both. Based on client experience, The Boston Consulting Group has developed an approach to transformation that flips the odds in a company’s favor. What does that look like in the real world? Here are five company examples that show successful transformations, across a range of industries and locations.

VF’s Growth Transformation Creates Strong Value for Investors

Value creation is a powerful lens for identifying the initiatives that will have the greatest impact on a company’s transformation agenda and for understanding the potential value of the overall program for shareholders.

VF offers a compelling example of a company using a sharp focus on value creation to chart its transformation course. In the early 2000s, VF was a good company with strong management but limited organic growth. Its “jeanswear” and intimate-apparel businesses, although responsible for 80 percent of the company’s revenues, were mature, low-gross-margin segments. And the company’s cost-cutting initiatives were delivering diminishing returns. VF’s top line was essentially flat, at about $5 billion in annual revenues, with an unclear path to future growth. VF’s value creation had been driven by cost discipline and manufacturing efficiency, yet, to the frustration of management, VF had a lower valuation multiple than most of its peers.

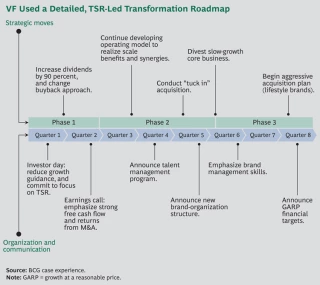

With BCG’s help, VF assessed its options and identified key levers to drive stronger and more-sustainable value creation. The result was a multiyear transformation comprising four components:

- A Strong Commitment to Value Creation as the Company’s Focus. Initially, VF cut back its growth guidance to signal to investors that it would not pursue growth opportunities at the expense of profitability. And as a sign of management’s commitment to balanced value creation, the company increased its dividend by 90 percent.

- Relentless Cost Management. VF built on its long-known operational excellence to develop an operating model focused on leveraging scale and synergies across its businesses through initiatives in sourcing, supply chain processes, and offshoring.

- A Major Transformation of the Portfolio. To help fund its journey, VF divested product lines worth about $1 billion in revenues, including its namesake intimate-apparel business. It used those resources to acquire nearly $2 billion worth of higher-growth, higher-margin brands, such as Vans, Nautica, and Reef. Overall, this shifted the balance of its portfolio from 70 percent low-growth heritage brands to 65 percent higher-growth lifestyle brands.

- The Creation of a High-Performance Culture. VF has created an ownership mind-set in its management ranks. More than 200 managers across all key businesses and regions received training in the underlying principles of value creation, and the performance of every brand and business is assessed in terms of its value contribution. In addition, VF strengthened its management bench through a dedicated talent-management program and selective high-profile hires. (For an illustration of VF’s transformation roadmap, see the exhibit.)

The results of VF’s TSR-led transformation are apparent. 1 1 For a detailed description of the VF journey, see the 2013 Value Creators Report, Unlocking New Sources of Value Creation , BCG report, September 2013. Notes: 1 For a detailed description of the VF journey, see the 2013 Value Creators Report, Unlocking New Sources of Value Creation , BCG report, September 2013. The company’s revenues have grown from $7 billion in 2008 to more than $11 billion in 2013 (and revenues are projected to top $17 billion by 2017). At the same time, profitability has improved substantially, highlighted by a gross margin of 48 percent as of mid-2014. The company’s stock price quadrupled from $15 per share in 2005 to more than $65 per share in September 2014, while paying about 2 percent a year in dividends. As a result, the company has ranked in the top quintile of the S&P 500 in terms of TSR over the past ten years.

A Consumer-Packaged-Goods Company Uses Several Levers to Fund Its Transformation Journey

A leading consumer-packaged-goods (CPG) player was struggling to respond to challenging market dynamics, particularly in the value-based segments and at the price points where it was strongest. The near- and medium-term forecasts looked even worse, with likely contractions in sales volume and potentially even in revenues. A comprehensive transformation effort was needed.

To fund the journey, the company looked at several cost-reduction initiatives, including logistics. Previously, the company had worked with a large number of logistics providers, causing it to miss out on scale efficiencies.

To improve, it bundled all transportation spending, across the entire network (both inbound to production facilities and out-bound to its various distribution channels), and opened it to bidding through a request-for-proposal process. As a result, the company was able to save 10 percent on logistics in the first 12 months—a very fast gain for what is essentially a commodity service.

Similarly, the company addressed its marketing-agency spending. A benchmark analysis revealed that the company had been paying rates well above the market average and getting fewer hours per full-time equivalent each year than the market standard. By getting both rates and hours in line, the company managed to save more than 10 percent on its agency spending—and those savings were immediately reinvested to enable the launch of what became a highly successful brand.

Next, the company pivoted to growth mode in order to win in the medium term. The measure with the biggest impact was pricing. The company operates in a category that is highly segmented across product lines and highly localized. Products that sell well in one region often do poorly in a neighboring state. Accordingly, it sought to de-average its pricing approach across locations, brands, and pack sizes, driving a 2 percent increase in EBIT.

Similarly, it analyzed trade promotion effectiveness by gathering and compiling data on the roughly 150,000 promotions that the company had run across channels, locations, brands, and pack sizes. The result was a 2 terabyte database tracking the historical performance of all promotions.

Using that information, the company could make smarter decisions about which promotions should be scrapped, which should be tweaked, and which should merit a greater push. The result was another 2 percent increase in EBIT. Critically, this was a clear capability that the company built up internally, with the objective of continually strengthening its trade-promotion performance over time, and that has continued to pay annual dividends.

Finally, the company launched a significant initiative in targeted distribution. Before the transformation, the company’s distributors made decisions regarding product stocking in independent retail locations that were largely intuitive. To improve its distribution, the company leveraged big data to analyze historical sales performance for segments, brands, and individual SKUs within a roughly ten-mile radius of that retail location. On the basis of that analysis, the company was able to identify the five SKUs likely to sell best that were currently not in a particular store. The company put this tool on a mobile platform and is in the process of rolling it out to the distributor base. (Currently, approximately 60 percent of distributors, representing about 80 percent of sales volume, are rolling it out.) Without any changes to the product lineup, that measure has driven a 4 percent jump in gross sales.

Throughout the process, management had a strong change-management effort in place. For example, senior leaders communicated the goals of the transformation to employees through town hall meetings. Cognizant of how stressful transformations can be for employees—particularly during the early efforts to fund the journey, which often emphasize cost reductions—the company aggressively talked about how those savings were being reinvested into the business to drive growth (for example, investments into the most effective trade promotions and the brands that showed the greatest sales-growth potential).

In the aggregate, the transformation led to a much stronger EBIT performance, with increases of nearly $100 million in fiscal 2013 and far more anticipated in 2014 and 2015. The company’s premium products now make up a much bigger part of the portfolio. And the company is better positioned to compete in its market.

A Leading Bank Uses a Lean Approach to Transform Its Target Operating Model

A leading bank in Europe is in the process of a multiyear transformation of its operating model. Prior to this effort, a benchmarking analysis found that the bank was lagging behind its peers in several aspects. Branch employees handled fewer customers and sold fewer new products, and back-office processing times for new products were slow. Customer feedback was poor, and rework rates were high, especially at the interface between the front and back offices. Activities that could have been managed centrally were handled at local levels, increasing complexity and cost. Harmonization across borders—albeit a challenge given that the bank operates in many countries—was limited. However, the benchmark also highlighted many strengths that provided a basis for further improvement, such as common platforms and efficient product-administration processes.

To address the gaps, the company set the design principles for a target operating model for its operations and launched a lean program to get there. Using an end-to-end process approach, all the bank’s activities were broken down into roughly 250 processes, covering everything that a customer could potentially experience. Each process was then optimized from end to end using lean tools. This approach breaks down silos and increases collaboration and transparency across both functions and organization layers.

Employees from different functions took an active role in the process improvements, participating in employee workshops in which they analyzed processes from the perspective of the customer. For a mortgage, the process was broken down into discrete steps, from the moment the customer walks into a branch or goes to the company website, until the house has changed owners. In the front office, the system was improved to strengthen management, including clear performance targets, preparation of branch managers for coaching roles, and training in root-cause problem solving. This new way of working and approaching problems has directly boosted both productivity and morale.

The bank is making sizable gains in performance as the program rolls through the organization. For example, front-office processing time for a mortgage has decreased by 33 percent and the bank can get a final answer to customers 36 percent faster. The call centers had a significant increase in first-call resolution. Even more important, customer satisfaction scores are increasing, and rework rates have been halved. For each process the bank revamps, it achieves a consistent 15 to 25 percent increase in productivity.

And the bank isn’t done yet. It is focusing on permanently embedding a change mind-set into the organization so that continuous improvement becomes the norm. This change capability will be essential as the bank continues on its transformation journey.

A German Health Insurer Transforms Itself to Better Serve Customers

Barmer GEK, Germany’s largest public health insurer, has a successful history spanning 130 years and has been named one of the top 100 brands in Germany. When its new CEO, Dr. Christoph Straub, took office in 2011, he quickly realized the need for action despite the company’s relatively good financial health. The company was still dealing with the postmerger integration of Barmer and GEK in 2010 and needed to adapt to a fast-changing and increasingly competitive market. It was losing ground to competitors in both market share and key financial benchmarks. Barmer GEK was suffering from overhead structures that kept it from delivering market-leading customer service and being cost efficient, even as competitors were improving their service offerings in a market where prices are fixed. Facing this fundamental challenge, Barmer GEK decided to launch a major transformation effort.

The goal of the transformation was to fundamentally improve the customer experience, with customer satisfaction as a benchmark of success. At the same time, Barmer GEK needed to improve its cost position and make tough choices to align its operations to better meet customer needs. As part of the first step in the transformation, the company launched a delayering program that streamlined management layers, leading to significant savings and notable side benefits including enhanced accountability, better decision making, and an increased customer focus. Delayering laid the path to win in the medium term through fundamental changes to the company’s business and operating model in order to set up the company for long-term success.

The company launched ambitious efforts to change the way things were traditionally done:

- A Better Client-Service Model. Barmer GEK is reducing the number of its branches by 50 percent, while transitioning to larger and more attractive service centers throughout Germany. More than 90 percent of customers will still be able to reach a service center within 20 minutes. To reach rural areas, mobile branches that can visit homes were created.

- Improved Customer Access. Because Barmer GEK wanted to make it easier for customers to access the company, it invested significantly in online services and full-service call centers. This led to a direct reduction in the number of customers who need to visit branches while maintaining high levels of customer satisfaction.

- Organization Simplification. A pillar of Barmer GEK’s transformation is the centralization and specialization of claim processing. By moving from 80 regional hubs to 40 specialized processing centers, the company is now using specialized administrators—who are more effective and efficient than under the old staffing model—and increased sharing of best practices.

Although Barmer GEK has strategically reduced its workforce in some areas—through proven concepts such as specialization and centralization of core processes—it has invested heavily in areas that are aligned with delivering value to the customer, increasing the number of customer-facing employees across the board. These changes have made Barmer GEK competitive on cost, with expected annual savings exceeding €300 million, as the company continues on its journey to deliver exceptional value to customers. Beyond being described in the German press as a “bold move,” the transformation has laid the groundwork for the successful future of the company.

Nokia’s Leader-Driven Transformation Reinvents the Company (Again)

We all remember Nokia as the company that once dominated the mobile-phone industry but subsequently had to exit that business. What is easily forgotten is that Nokia has radically and successfully reinvented itself several times in its 150-year history. This makes Nokia a prime example of a “serial transformer.”

In 2014, Nokia embarked on perhaps the most radical transformation in its history. During that year, Nokia had to make a radical choice: continue massively investing in its mobile-device business (its largest) or reinvent itself. The device business had been moving toward a difficult stalemate, generating dissatisfactory results and requiring increasing amounts of capital, which Nokia no longer had. At the same time, the company was in a 50-50 joint venture with Siemens—called Nokia Siemens Networks (NSN)—that sold networking equipment. NSN had been undergoing a massive turnaround and cost-reduction program, steadily improving its results.

When Microsoft expressed interest in taking over Nokia’s device business, Nokia chairman Risto Siilasmaa took the initiative. Over the course of six months, he and the executive team evaluated several alternatives and shaped a deal that would radically change Nokia’s trajectory: selling the mobile business to Microsoft. In parallel, Nokia CFO Timo Ihamuotila orchestrated another deal to buy out Siemens from the NSN joint venture, giving Nokia 100 percent control over the unit and forming the cash-generating core of the new Nokia. These deals have proved essential for Nokia to fund the journey. They were well-timed, well-executed moves at the right terms.

Right after these radical announcements, Nokia embarked on a strategy-led design period to win in the medium term with new people and a new organization, with Risto Siilasmaa as chairman and interim CEO. Nokia set up a new portfolio strategy, corporate structure, capital structure, robust business plans, and management team with president and CEO Rajeev Suri in charge. Nokia focused on delivering excellent operational results across its portfolio of three businesses while planning its next move: a leading position in technologies for a world in which everyone and everything will be connected.

Nokia’s share price has steadily climbed. Its enterprise value has grown 12-fold since bottoming out in July 2012. The company has returned billions of dollars of cash to its shareholders and is once again the most valuable company in Finland. The next few years will demonstrate how this chapter in Nokia’s 150-year history of serial transformation will again reinvent the company.

Managing Director & Senior Partner

San Francisco - Bay Area

Managing Director & Senior Partner, Chairman of the BCG Henderson Institute

ABOUT BOSTON CONSULTING GROUP

Boston Consulting Group partners with leaders in business and society to tackle their most important challenges and capture their greatest opportunities. BCG was the pioneer in business strategy when it was founded in 1963. Today, we work closely with clients to embrace a transformational approach aimed at benefiting all stakeholders—empowering organizations to grow, build sustainable competitive advantage, and drive positive societal impact.

Our diverse, global teams bring deep industry and functional expertise and a range of perspectives that question the status quo and spark change. BCG delivers solutions through leading-edge management consulting, technology and design, and corporate and digital ventures. We work in a uniquely collaborative model across the firm and throughout all levels of the client organization, fueled by the goal of helping our clients thrive and enabling them to make the world a better place.

© Boston Consulting Group 2024. All rights reserved.

For information or permission to reprint, please contact BCG at [email protected] . To find the latest BCG content and register to receive e-alerts on this topic or others, please visit bcg.com . Follow Boston Consulting Group on Facebook and X (formerly Twitter) .

Subscribe to our Business Transformation E-Alert.

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

LeadingChange →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

Thank you! We will contact you in the near future.

Thanks for your interest, we will get back to you shortly

- Change Management Tools

- Organizational Development

- Organizational Change

Home » Change Management » Amazon: The Ultimate Change Management Case Study

Amazon: The Ultimate Change Management Case Study

Amazon’s innovations have helped it become extremely successful, making it an excellent change management case study.

Since it was formed, Amazon has innovated across countless areas and industries, including:

- Warehouse automation

- The web server industry

- Streaming video and on-demand media

- Electronic books

Considering that Amazon started as an online bookstore, these accomplishments are quite impressive.

Examining Amazon as a change management highlights a few important business lessons:

- Innovation fuels success, especially in today’s digital economy

- Speed is the ultimate weapon

- Those who resist organizational change can easily get left behind

Below, we’ll examine some of Amazon’s changes … and hopefully discover a few reasons why it has become so successful.

Let’s get started.

Below are 10 ways Amazon has changed its business, transforming itself far beyond a mere online bookseller.

In no particular order…

1. Amazon Web Services

When Amazon Web Services (AWS) started out, most developers didn’t take it seriously.

A decade later, it was the go-to cloud server company in the world.

In fact, Bezos has even said that AWS was the biggest part of the company.

Since it has more capacity than its nearest 14 competitors combined, this shouldn’t come as a surprise.

2. Whole Foods

After acquiring Whole Foods , Amazon began making changes to the grocery store chain.

A few of these include:

- Adding Amazon products to the shelves

- Integrating Whole Foods and Amazon Prime

- Internal restructuring

Other programs include food delivery from Whole Foods, rewards for customers using Amazon credit cards, and discounts for Prime members.

3. Delivery

Amazon has drastically innovated product delivery.

For instance, customers with Prime memberships can enjoy free two-day delivery.

In certain cities , Prime members can also get free same-day or one-day delivery.

And with its drone delivery program on the horizon, customers may be able to receive orders in 30 minutes or less .

4. Warehouse Automation

Amazon warehouses have undergone major technological transformations.

Currently, Amazon warehouses uses robots to collect and transport many of its products.

In coming years, though, even more of the company’s 200,000+ warehouse workers could be replaced by robots .

In 2016 alone, it increased robot workers by 50% .

5. TV and Prime Video

Another innovation of the former bookseller is its foray into TV, movies, and video.

Amazon began by selling videos and DVDs. Now it streams, rents, and sells digital copies of videos.

On top of that, the company has joined YouTube, Netflix, and other tech giants by producing its own movies and TV shows.

6. Amazon in Other Countries

Change managers would also be interested in how Amazon adapts itself to other countries’ economies.

In India, for instance, Amazon has been forced to adopt unique measures.

These include:

- Using mom-n-pop stores as delivery locations

- Hiring bicycle or motorcycle couriers for last-mile deliveries

- Creating mobile tea carts that serve tea and teach business owners about e-commerce

These types of innovations are necessary to succeed in other countries.

Failure to adapt to these changes often proves disastrous, which is a major reason why Google China failed .

7. Amazon Go

Amazon isn’t just an online retailer … it has now opened up physical grocery stores.

However, as with all of its business ventures, it aims to disrupt, transform, and dominate retail grocery stores.

In this case, Amazon wants to create grocery stores with zero clerks .

Amazon Go is a venture that promises no checkout lines, no hassle, and ultra-convenience.

8. Kindle and E-Books

Everyone knows that Kindle has been one of Amazon’s biggest innovations.

This product has single-handedly revolutionized the book publishing industry.

For better or for worse, Kindle has changed the way books are read, sold, and distributed.

Some estimates have placed Kindle e-book revenue at over half a billion dollars per year.

9. Affiliate Marketing

Early on in Amazon’s career, it opened its doors to online sales associates.

Members of Amazon Associates can earn revenue by sending web visitors to the sales giant.

According to Amazon, there are over 900,000 global members – all working to promote the company’s products and online presence.

10. Blue Origin

Technically speaking, Blue Origin is a different company from Amazon.

However, it’s worth noting that Amazon and Jeff Bezos can hardly be separated.

Without the famous founder’s extreme drive and vision, Amazon wouldn’t be what it is today.

And without his willingness to innovate, he never would have founded Blue Origin.

Like Elon Musk’s SpaceX, Blue Origin literally aims for the stars.

Its mission and goal – “millions of people living and working in space.”

Conclusion: Amazon Proves that Change Drives Success

It’s safe to say that Amazon’s defining trait has been its willingness to change.

What started as an online bookstore has become a multi-industry behemoth.

It has crushed companies that don’t innovate … it has revolutionized several industries … and it shows no signs of slowing.

The biggest lesson from this change management case study?

Innovation and change drive success .

If you liked this article, you may also like:

Workplace diversity training: Effective training...

What is cultural change?

WalkMe Team

WalkMe spearheaded the Digital Adoption Platform (DAP) for associations to use the maximum capacity of their advanced resources. Utilizing man-made consciousness, AI, and context-oriented direction, WalkMe adds a powerful UI layer to raise the computerized proficiency, everything being equal.

Join the industry leaders in digital adoption

By clicking the button, you agree to the Terms and Conditions. Click Here to Read WalkMe's Privacy Policy

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Most Successful Approaches to Leading Organizational Change

- Deborah Rowland,

- Michael Thorley,

- Nicole Brauckmann

A closer look at four distinct ways to drive transformation.

When tasked with implementing large-scale organizational change, leaders often give too much attention to the what of change — such as a new organization strategy, operating model or acquisition integration — not the how — the particular way they will approach such changes. Such inattention to the how comes with the major risk that old routines will be used to get to new places. Any unquestioned, “default” approach to change may lead to a lot of busy action, but not genuine system transformation. Through their practice and research, the authors have identified the optimal ways to conceive, design, and implement successful organizational change.

Management of long-term, complex, large-scale change has a reputation of not delivering the anticipated benefits. A primary reason for this is that leaders generally fail to consider how to approach change in a way that matches their intent.

- Deborah Rowland is the co-author of Sustaining Change: Leadership That Works , Still Moving: How to Lead Mindful Change , and the Still Moving Field Guide: Change Vitality at Your Fingertips . She has personally led change at Shell, Gucci Group, BBC Worldwide, and PepsiCo and pioneered original research in the field, accepted as a paper at the 2016 Academy of Management and the 2019 European Academy of Management. Thinkers50 Radar named as one of the generation of management thinkers changing the world of business in 2017, and she’s on the 2021 HR Most Influential Thinker list. She is Cambridge University 1st Class Archaeology & Anthropology Graduate.

- Michael Thorley is a qualified accountant, psychotherapist, executive psychological coach, and coach supervisor integrating all modalities to create a unique approach. Combining his extensive experience of running P&L accounts and developing approaches that combine “hard”-edged and “softer”-edged management approaches, he works as a non-executive director and advisor to many different organizations across the world that wish to generate a new perspective on change.

- Nicole Brauckmann focuses on helping organizations and individuals create the conditions for successful emergent change to unfold. As an executive and consultant, she has worked to deliver large-scale complex change across different industries, including energy, engineering, financial services, media, and not-for profit. She holds a PhD at Faculty of Philosophy, Westfaelische Wilhelms University Muenster and spent several years on academic research and teaching at University of San Diego Business School.

Partner Center

JavaScript seems to be disabled in your browser. For the best experience on our site, be sure to turn on Javascript in your browser.

Hello! You are viewing this site in ${language} language. Is this correct?

Customer Success Stories

Elevate your success: Discover how our customers achieved remarkable results using our products.

Explore What’s Possible with Prosci and Our Solutions

Discover how organizations are utilizing Prosci to customize our methodologies, incorporate training seamlessly into their corporate cultures, and expand the implementation of change management within their organizations.

UVA Elevates Project Portfolio Management With Prosci Change Management

SoCalGas Builds a Change-Ready Organization With Prosci

Credit Union Creates a Culture of Change and Change Learning

Customer Stories: Real Sucess, Real Impact

Explore these inspiring tales of innovation, growth, and success from our valued customers. Learn how they harnessed our products and services to overcome challenges, drive transformation, and achieve extraordinary results.

- All Industries

- Business Process Outsourcing

- Credit Union

- Facility Management

- Financial Services

- Food and Beverages

- Higher Education

- Manufacturing

- Transportation

- All Solutions

- Advisory Services

- Change Management Certification Program

- Change Management Sponsor Briefing

- Leading Your Team Through Change

- ECM Boot Camp

- ECM eLearning License

- ECM License

- Delivering Project Results Workshop

- Train-the-Trainer Program

Organizational Change Management Boosts Project ROI at Sunflower Electric Power Corp.

Municipal Utility Builds CMO, Braces for ERP Implementation With Help From Prosci

Microsoft Investor Relations Delivers Flawless Earnings Release With Prosci

Insurance Provider Scales Change Management Program for Growth

Financial Services Leader Launches New Workday System, Prepares for Accelerated Change

Latin American Financial Firm Embraces Digital and Cultural Transformation

FAA Builds Change Capability to Tackle Complex Change

Academic Health System Leverages Change Management for Integration and Leadership Initiatives

Multinational Food Corporation Exceeds Expectations With SAP Implementation

Microsoft Increases Customer Adoption Rates With Prosci

Energy and Utility Company Builds Change-Ready Organization With Prosci

Multinational Logistics Company Enables Growth Through Change Capability

Transportation Organization Drives Sustainable Improvements With Prosci

Global Manufacturing Company Equips Managers and PMO With Change Competencies

SYKES Embraces Change Management to Ensure Success of Vital, Large-Scale Initiatives

IT Distributor Increases ROI with Change Capability

Global Bank Establishes Change Management as Core Capability

University Builds Change Capability to Help Execute New Strategic Plan

European Facility Management Group Successfully Launches New Division

Global Manufacturing Organization Embeds Change Management and Shifts Company Culture

Husky Uses the ADKAR Model to Achieve Project Results

Texas A&M Implements Workday

Danish Transport Company Advances Change Capability Globally

Testimonials from a Selection of Our Valued Clients

Gary Vansuch

Director of Process Improvement CDOT

Here at CDOT, we know that building and maintaining effective organizational change capability is crucial. Prosci’s approach is straightforward, research-based, and easy to use, and aligns with our strategic direction.

Mary Brackett

Senior Associate, Organizational Excellence University of Virgina

The practical nature of Prosci's approach to change management, along with the larger body of Prosci knowledge that's readily available to us, is paying tremendous dividends to the University of Virginia.

Chapter 21 - Organizational Change Management in SRE

- Table of Contents

- Foreword II

- 1. How SRE Relates to DevOps

- Part I - Foundations

- 2. Implementing SLOs

- 3. SLO Engineering Case Studies

- 4. Monitoring

- 5. Alerting on SLOs

- 6. Eliminating Toil

- 7. Simplicity

- Part II - Practices

- 9. Incident Response

- 10. Postmortem Culture: Learning from Failure

- 11. Managing Load

- 12. Introducing Non-Abstract Large System Design

- 13. Data Processing Pipelines

- 14. Configuration Design and Best Practices

- 15. Configuration Specifics

- 16. Canarying Releases

- Part III - Processes

- 17. Identifying and Recovering from Overload

- 18. SRE Engagement Model

- 19. SRE: Reaching Beyond Your Walls

- 20. SRE Team Lifecycles

- 21. Organizational Change Management in SRE

- Appendix A. Example SLO Document

- Appendix B. Example Error Budget Policy

- Appendix C. Results of Postmortem Analysis

- About the Editors

Organizational Change Management in SRE

By Alex Bramley, Ben Lutch, Michelle Duffy, and Nir Tarcic with Betsy Beyer

In the introduction to the first SRE Book , Ben Treynor Sloss describes SRE teams as “characterized by both rapid innovation and a large acceptance of change,” and specifies organizational change management as a core responsibility of an SRE team. This chapter examines how theory can apply in practice across SRE teams. After reviewing some key change management theories, we explore two case studies that demonstrate how different styles of change management have played out in concrete ways at Google.

Note that the term change management has two interpretations: organizational change management and change control. This chapter examines change management as a collective term for all approaches to preparing and supporting individuals, teams, and business units in making organizational change. We do not discuss this term within a project management context, where it may be used to refer to change control processes, such as change review or versioning.

SRE Embraces Change

More than 2,000 years ago, the Greek philosopher Heraclitus claimed change is the only constant. This axiom still holds true today—especially in regards to technology, and particularly in rapidly evolving internet and cloud sectors.

Product teams exist to build products, ship features, and delight customers. At Google, most change is fast-paced, following a “launch and iterate” approach. Executing on such change typically requires coordination across systems, products, and globally distributed teams. Site Reliability Engineers are frequently in the middle of this complicated and rapidly shifting landscape, responsible for balancing the risks inherent in change with product reliability and availability. Error budgets (see Implementing SLOs ) are a primary mechanism for achieving this balance.

Introduction to Change Management

Change management as an area of study and practice has grown since foundational work in the field by Kurt Lewin in the 1940s. Theories primarily focus on developing frameworks for managing organizational change. In-depth analysis of particular theories is beyond the scope of this book, but to contextualize them within the realm of SRE, we briefly describe some common theories and how each might be applicable in an SRE-type organization. While the formal processes implicit in these theoretical frameworks have not been applied by SRE at Google, considering SRE activities through the lens of these frameworks has helped us refine our approach to managing change. Following this discussion, we will introduce some case studies that demonstrate how elements of some of these theories apply to change management activities led by Google SRE.

Lewin’s Three-Stage Model

Kurt Lewin’s “unfreeze–change–freeze” model for managing change is the oldest of the relevant theories in this field. This simple three-stage model is a tool for managing process review and the resulting changes in group dynamics. Stage 1 entails persuading a group that change is necessary. Once they are amenable to the idea of change, Stage 2 executes that change. Finally, when the change is broadly complete, Stage 3 institutionalizes the new patterns of behavior and thought. The model’s core principle posits the group as the primary dynamic instrument, arguing that individual and group interactions should be examined as a system when the group is planning, executing, and completing any period of change. Accordingly, Lewin's work is most useful for planning organizational change at the macro level.

McKinsey’s 7-S Model

McKinsey’s seven S’s stand for structure, strategy, systems, skills, style, staff, and shared values. Similar to Lewin’s work, this framework is also a toolset for planned organizational change. While Lewin’s framework is generic, 7-S has an explicit goal of improving organizational effectiveness. Application of both theories begins with an analysis of current purpose and processes. However, 7-S also explicitly covers both business elements (structure, strategy, systems) and people-management elements (shared values, skills, style, staff). This model could be useful for a team considering change from a traditional systems administration focus to the more holistic Site Reliability Engineering approach.

Kotter’s Eight-Step Process for Leading Change

Time magazine named John P. Kotter’s 1996 book Leading Change (Harvard Business School Press) one of the Top 25 Most Influential Business Management Books of all time . Figure 21-1 depicts the eight steps in Kotter’s change management process.

Kotter’s process is particularly relevant to SRE teams and organizations, with one small exception: in many cases (e.g., the upcoming Waze case study), there’s no need to create a sense of urgency. SRE teams supporting products and systems with accelerating growth are frequently faced with urgent scaling, reliability, and operational challenges. The component systems are often owned by multiple development teams, which may span several organizational units; scaling issues may also require coordination with teams ranging from physical infrastructure to product management. Because SRE is often on the front line when problems occur, it is uniquely motivated to lead the change needed to ensure products are available 24/7/365. Much of SRE work (implicitly) embraces Kotter’s process to ensure the continued availability of supported products.

The Prosci ADKAR Model

The Prosci ADKAR model focuses on balancing both the business and people aspects of change management. ADKAR is an acronym for the goals individuals must achieve for successful organizational change: awareness, desire, knowledge, ability, and reinforcement.

In principle, ADKAR provides a useful, thoughtful, people-centric framework. However, its applicability to SRE is limited because operational responsibilities quite often impose considerable time constraints. Proceeding iteratively through ADKAR’s stages and providing the necessary training or coaching requires pacing and investment in communication, which are difficult to implement in the context of globally distributed, operationally focused teams. That said, Google has successfully used ADKAR-style processes for introducing and building support for high-level changes—for example, introducing global organizational change to the SRE management team while preserving local autonomy for implementation details.

Emotion-Based Models

The Bridges Transition Model describes people’s emotional reactions to change. While a useful management tool for people managers, it’s not a framework or process for change management. Similarly, the Kübler-Ross Change Curve describes ranges of emotions people may feel when faced with change. Developed from Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s research on death and dying, 1 it has been applied to understanding and anticipating employee reactions to organizational change. Both models can be useful in maintaining high employee productivity throughout periods of change, since unhappy people are rarely productive.

The Deming Cycle

Also known as the Plan-Do-Check-Act (or PDCA) Cycle, this process from statistician Edward W. Deming is commonly used in DevOps environments for process improvements—for example, adoption of continuous integration/continuous delivery techniques. It is not suited to organizational change management because it does not cover the human side of change, including motivations and leadership styles. Deming’s focus is to take existing processes (mechanical, automated, or workflow) and cyclically apply continuous improvements. The case studies we refer to in this chapter deal with larger, organizational changes where iteration is counterproductive: frequent, wrenching org-chart changes can sap employee confidence and negatively impact company culture.

How These Theories Apply to SRE

No change management model is universally applicable to every situation, so it’s not surprising that Google SRE hasn’t exclusively standardized on one model. That said, here’s how we like to think about applying these models to common change management scenarios in SRE:

- Kotter’s Eight-Step Process is a change management model for SRE teams who necessarily embrace change as a core responsibility.

- The Prosci ADKAR model is a framework that SRE management may want to consider to coordinate change across globally distributed teams.

- All individual SRE managers will benefit from familiarity with both the Bridges Transition Model and the Kübler-Ross Change Curve , which provide tools to support employees in times of organizational change.

Now that we’ve introduced the theories, let’s look at two case studies that show how change management has played out at Google.

Case Study 1: Scaling Waze—From Ad Hoc to Planned Change

Waze is a community-based navigation app acquired by Google in 2013. After the acquisition, Waze entered a period of significant growth in active users, engineering staff, and computing infrastructure, but continued to operate relatively autonomously within Google. The growth introduced many challenges, both technical and organizational.

Waze’s autonomy and startup ethos led them to meet these challenges with a grassroots technical response from small groups of engineers, rather than management-led, structured organizational change as implied by the formal models discussed in the previous section. Nevertheless, their approach to propagating changes throughout the organization and infrastructure significantly resembles Kotter’s model of change management. This case study examines how Kotter’s process (which we apply retroactively) aptly describes a sequence of technical and organizational challenges Waze faced as they grew post-acquisition.

The Messaging Queue: Replacing a System While Maintaining Reliability

Kotter’s model begins the cycle of change with a sense of urgency . Waze’s SRE team needed to act quickly and decisively when the reliability of Waze’s message queueing system regressed badly, leading to increasingly frequent and severe outages. As shown in Figure 21-2 , the message queueing system was critical to operations because every component of Waze (real time, geocoding, routing, etc.) used it to communicate with other components internally.

As throughput on the message queue grew significantly, the system simply couldn’t cope with the ever-increasing demands. SREs needed to manually intervene to preserve system stability at shorter and shorter intervals. At its worst, the entire Waze SRE team spent most of a two-week period firefighting 24/7, eventually resorting to restarting some components of the message queue hourly to keep messages flowing and tens of millions of users happy.

Because SRE was also responsible for building and releasing all of Waze’s software, this operational load had a noticeable impact on feature velocity—when SREs spent all of their time fighting fires, they hardly had time to support new feature rollouts. By highlighting the severity of the situation, engineers convinced Waze’s leadership to reevaluate priorities and dedicate some engineering time to reliability work. A guiding coalition of two SREs and a senior engineer came together to form a strategic vision of a future where SRE toil was no longer necessary to keep messages flowing. This small team evaluated off-the-shelf message queue products, but quickly decided that they could only meet Waze’s scaling and reliability requirements with a custom-built solution.

Developing this message queue in-house would be impossible without some way to maintain operations in the meantime. The coalition removed this barrier to action by enlisting a volunteer army of developers from the teams who used the current messaging queue. Each team reviewed the codebase for their service to identify ways to cut the volume of messages they published. Trimming unnecessary messages and rolling out a compression layer on top of the old queue reduced some load on the system. The team also gained some more operational breathing room by building a dedicated messaging queue for one particular component that was responsible for over 30% of system traffic. These measures yielded enough of a temporary operational reprieve to allow for a two-month window to assemble and test a prototype of the new messaging system.

Migrating a message queue system that handles tens of thousands of messages per second is a daunting task even without the pressure of imminent service meltdown. But gradually reducing the load on the old system would relieve some of this pressure, affording the team a longer time window to complete the migration. To this end, Waze SRE rebuilt the client libraries for the message queue so they could publish and receive messages using either or both systems, using a centralized control surface to switch the traffic over.

Once the new system was proven to work, SRE began the first phase of the migration: they identified some low-traffic, high-importance message flows for which messaging outages were catastrophic. For these flows, writing to both messaging systems would provide a backup path. A couple of near misses, where the backup path kept core Waze services operating while the old system faltered, provided the short-term wins that justified the initial investment.

Mass migration to the new system required SRE to work closely with the teams who use it. The team needed to figure out both how to best support their use cases and how to coordinate the traffic switch. As the SRE team automated the process of migrating traffic and the new system supported more use cases by default, the rate of migrations accelerated significantly .

Kotter’s change management process ends with instituting change . Eventually, with enough momentum behind the adoption of the new system, the SRE team could declare the old system deprecated and no longer supported. They migrated the last stragglers a few quarters later. Today, the new system handles more than 1000 times the load of the previous one, and requires little manual intervention from SREs for ongoing support and maintenance.

The Next Cycle of Change: Improving the Deployment Process

The process of change as a cycle was one of Kotter’s key insights. The cyclical nature of meaningful change is particularly apparent when it comes to the types of technical changes that face SRE. Eliminating one bottleneck in a system often highlights another one. As each change cycle is completed, the resulting improvements, standardization, and automation free up engineering time. Engineering teams now have the space to more closely examine their systems and identify more pain points, triggering the next cycle of change.

When Waze SRE could finally take a step back from firefighting problems related to the messaging system, a new bottleneck emerged, bringing with it a renewed sense of urgency : SRE’s sole ownership of releases was noticeably and seriously hindering development velocity. The manual nature of releases required a significant amount of SRE time. To exacerbate an already suboptimal situation, system components were large, and because releases were costly, they were relatively infrequent. As a result, each release represented a large delta, significantly increasing the possibility that a major defect would necessitate a rollback.

Improvements toward a better release process happened incrementally, as Waze SRE didn’t have a master plan from square one. To slim down system components so the team could iterate each more rapidly, one of the senior Waze developers created a framework for building microservices. This provided a standard “batteries included” platform that made it easy for the engineering organization to start breaking their components apart. SRE worked with this developer to include some reliability-focused features—for example, a common control surface and a set of behaviors that were amenable to automation. As a result, SRE could develop a suite of tools to manage the previously costly parts of the release process. One of these tools incentivized adoption by bundling all of the steps needed to create a new microservice with the framework.

These tools were quick-and-dirty at first—the initial prototypes were built by one SRE over the course of several days. As the team cleaved more microservices from their parent components, the value of the SRE-developed tools quickly became apparent to the wider organization. SRE was spending less time shepherding the slimmed-down components into production, and the new microservices were much less costly to release individually.

While the release process was already much improved, the proliferation of new microservices meant that SRE’s overall burden was still concerning. Engineering leadership was unwilling to assume responsibility for the release process until releases were less burdensome.

In response, a small coalition of SREs and developers sketched out a strategic vision to shift to a continuous deployment strategy using Spinnaker , an open source, multicloud, continuous delivery platform for building and executing deployment workflows. With the time saved by our bootstrap tooling, the team now was able to engineer this new system to enable one-click builds and deployments of hundreds or thousands of microservices. The new system was technically superior to the previous system in every way, but SRE still couldn’t persuade development teams to make the switch. This reluctance was driven by two factors: the obvious disincentive of having to push their own releases to production, plus change aversion driven by poor visibility into the release process.

Waze SRE tore down these barriers to adoption by showing how the new process added value. The team built a centralized dashboard that displayed the release status of binaries and a number of standard metrics exported by the microservice framework. Development teams could easily link their releases to changes in those metrics, which gave them confidence that deployments were successful. SRE worked closely with a few volunteer systems-oriented development teams to move services to Spinnaker. These wins proved that the new system could not only fulfill its requirements, but also add value beyond the original release process. At this point, engineering leadership set a goal for all teams to perform releases using the new Spinnaker deployment pipelines.

To facilitate the migration, Waze SRE provided organization-wide Spinnaker training sessions and consulting sessions for teams with complex requirements. When early adopters became familiar with the new system, their positive experiences sparked a chain reaction of accelerating adoption . They found the new process faster and less painful than waiting for SRE to push their releases. Now, engineers began to put pressure on dependencies that had not moved, as they were the impediment to faster development velocity—not the SRE team!

Today, more than 95% of Waze’s services use Spinnaker for continuous deployment, and changes can be pushed to production with very little human involvement. While Spinnaker isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution, configuring a release pipeline is trivial if a new service is built using the microservices framework, so new services have a strong incentive to standardize on this solution.

Lessons Learned

Waze’s experience in removing bottlenecks to technical change contains a number of useful lessons for other teams attempting engineering-led technical or organizational change. To begin with, change management theory is not a waste of time! Viewing this development and migration process through the lens of Kotter’s process demonstrates the model’s applicability. A more formal application of Kotter’s model at the time could have helped streamline and guide the process of change.

Change instigated from the grass roots requires close collaboration between SRE and development, as well as support from executive leadership. Creating a small, focused group with members from all parts of the organization—SRE, developers, and management—was key to the team’s success. A similar collaboration was vital to instituting the change. Over time, these ad hoc groups can and should evolve into more formal and structured cooperation, where SREs are automatically involved in design discussions and can advise on best practices for building and deploying robust applications in a production environment throughout the entire product lifecycle.

Incremental change is much easier to manage. Jumping straight to the “perfect” solution is too large a step to take all at once (not to mention probably infeasible if your system is about to collapse), and the concept of “perfect” will likely evolve as new information comes to light during the change process. An iterative approach can demonstrate early wins that help an organization buy into the vision of change and justify further investment. On the other hand, if early iterations don’t demonstrate value, you’ll waste less time and fewer resources when you inevitably abandon the change. Because incremental change doesn’t happen all at once, having a master plan is invaluable. Describe the goals in broad terms, be flexible, and ensure that each iteration moves toward them.

Finally, sometimes your current solutions can’t support the requirements of your strategic vision. Building something new has a large engineering cost, but can be worthwhile if the project pushes you out of a local maxima and enables long-term growth. As a thought experiment, figure out where bottlenecks might arise in your systems and tooling as your business and organization grow over the next few years. If you suspect any elements don’t scale horizontally, or have superlinear (or worse, exponential) growth with respect to a core business metric such as daily active users, you may need to consider redesigning or replacing them.

Waze’s development of a new in-house message queue system shows that it is possible for small groups of determined engineers to institute change that moves the needle toward greater service reliability. Mapping Kotter’s model onto the change shows that some consideration of change management strategy can help provide a formula for success even in small, engineering-led organizations. And, as the next case study also demonstrates, when changes promote standardizing technology and processes, the organization as a whole can reap considerable efficiency gains.

Case Study 2: Common Tooling Adoption in SRE

SREs are opinionated about the software they can and should use to manage production. Years of experience, observing what goes well and what doesn’t, and examining the past through the lens of the postmortem, have given SREs a deep background coupled with strong instincts. Specifying, building, and implementing software to automate this year’s job away is a core value in SRE. In particular, Google SRE recently focused our efforts on horizontal software. Adoption of the same solution by a critical mass of users and developers creates a virtuous cycle and reduces reinvention of wheels. Teams who otherwise might not interact share practices and policies that are automated using the same software.

This case study is based on an organizational evolution, not a response to a systems scaling or reliability issue (as discussed in the Waze case study). Hence, the Prosci ADKAR model (shown in Figure 21-3 ) is a better fit than Kotter’s model, as it recognizes both explicit organizational/people management characteristics and technical considerations during the change.

Problem Statement

A few years ago, Google SRE found itself using multiple independent software solutions for approximately the same problem across multiple problem spaces: monitoring, releases and rollouts, incident response, capacity management, and so on.

This end state arose in part because the people building tools for SRE were dissociated from their users and their requirements. The tool developers didn’t always have a current view of the problem statement or the overall production landscape—the production environment changes very rapidly and in new ways as new software, hardware, and use cases are brought to life almost daily. Additionally, the consumers of tools were varied, sometimes with orthogonal needs (“this rollout has to be fast; approximate is fine” versus “this rollout has to be 100% correct; okay for it to go slowly”).

As a result, none of these long-term projects fully addressed anyone’s needs, and each was characterized by varying levels of development effort, feature completeness, and ongoing support. Those waiting for the big use case—a nonspecific, singing-and-dancing solution of the future—waited a long time, got frustrated, and used their own software engineering skills to create their own niche solution. Those who had smaller, specific needs were loath to adopt a broader solution that wasn’t as tailored to them. The long-term, technical, and organizational benefits of more universal solutions were clear, but customers, services, and teams were not staffed or rewarded for waiting. To compound this scenario, requirements of both large and small customer teams changed over time.

What We Decided to Do

To scope this scenario as one concrete problem space, we asked ourselves: What if all Google SREs could use a common monitoring engine and set of dashboards, which were easy to use and supported a wide variety of use cases without requiring customization?

Likewise, we could extend this model of thinking to releases and rollouts, incident response, capacity management, and beyond. If the initial configuration of a product captured a wide representation of approaches to address the majority of our functional needs, our general and well-informed solutions would become inevitable over time. At some point, the critical mass of engineers who interact with production would outgrow whatever solution they were using and self-select to migrate to a common, well-supported set of tools and automation, abandoning their custom-built tools and their associated maintenance costs.

SRE at Google is fortunate that many of its engineers have software engineering backgrounds and experience. It seemed like a natural first step to encourage engineers who were experts and opinionated about specific problems—from load balancing to rollout tooling to incident management and response—to work as a virtual team, self-selected by a common long-term vision. These engineers would translate their vision into working, real software that would eventually be adopted across all of SRE, and then all of Google, as the basic functions of production.

To return to the ADKAR model for change management, the steps discussed so far—identifying a problem and acknowledging an opportunity—are textbook examples of ADKAR’s initiating awareness step. The Google SRE leadership team agreed on the need ( desire ) and had sufficient knowledge and ability to move to designing solutions fairly quickly.

Our first task was to converge upon a number of topics that we agreed were central, and that would benefit greatly from a consistent vision: to deliver solutions and adoption plans that fit most use cases. Starting from a list of 65+ proposed projects, we spent multiple months collecting customer requirements, verifying roadmaps, and performing market analysis, ultimately scoping our efforts toward a handful of vetted topics.

Our initial design created a virtual team of SRE experts around these topics. This virtual team would contribute a significant percentage of their time, around 80%, to these horizontal projects. The idea behind 80% time and a virtual team was to ensure we did not design or build solutions without constant contact with production. However, we (maybe predictably) discovered a few pain points with this approach:

- Coordinating a virtual team—whose focus was broken by being on-call regularly, across multiple time zones—was very difficult. There was a lot of state to be swapped between running a service and building a serious piece of software.

- Everything from gathering consensus to code reviews was affected by the lack of a central location and common time.

- Headcount for horizontal projects initially had to come from existing teams, who now had fewer engineering resources to tackle their own projects. Even at Google, there’s tension between delegating headcount to support the system as is versus delegating headcount to build future-looking infrastructure.

With enough data in hand, we realized we needed to redesign our approach, and settled on the more familiar centralized model. Most significantly, we removed the requirement that team members split their time 80/20 between project work and on-call duties. Most SRE software development is now done by small groups of senior engineers with plenty of on-call experience, but who are heads-down focused on building software based on those experiences. We also physically centralized many of these teams by recruiting or moving engineers. Small group (6–10 people) development is simply more efficient within one room (however, this argument doesn’t apply to all groups—for example, remote SRE teams). We can still meet our goal of collecting requirements and perspectives across the entire Google engineering organization via videoconference, email, and good old-fashioned travel.

So our evolution of design actually ended up in a familiar place—small, agile, mostly local, fast-moving teams—but with the added emphasis on selecting and building automation and tools for adoption by 60% of Google engineers (the figure we decided was a reasonable interpretation of the goal of “ almost everyone at Google”). Success means most of Google is using what SRE has built to manage their production environment.

The ADKAR model maps the implementation phase of the change project between the people-centric stages of knowledge and ability . This case study bears out that mapping. We had many engaged, talented, and knowledgeable engineers, but we were asking people who had been focused on SRE concerns to act like product software development engineers by focusing on customer requirements, product roadmaps, and delivery commitments. We needed to revisit the implementation of this change to enable engineers to demonstrate their abilities with respect to these new attributes.

Implementation: Monitoring

To return to the monitoring space mentioned in the previous section, Chapter 31 in the first SRE book described how Viceroy—Google SRE’s effort to create a single monitoring dashboard solution suitable for everyone—addressed the problem of disparate custom solutions. Several SRE teams worked together to create and run the initial iteration, and as Viceroy grew to become the de facto monitoring and dashboarding solution at Google, a dedicated centralized SRE development team assumed ownership of the project.

But even when the Viceroy framework united SRE under a common framework, there was a lot of duplicated effort as teams built complex custom dashboards specific to their services. While Viceroy provided a standard hosted method to design and build visual displays of data, it still required each team to decide what data to display and how to organize it.