Browser does not support script.

- Getting started

- Career progression

- Teachers and careers advisors

- Employment advisors

Case studies

Watch their stories - crg homecare.

Meet Molly, Connor and Ella Phoebe - they tell us what it's like working in the rewarding world of adult social care and supporting people like Martin, who describes the impact their support has had in helping him to live an independent life. These videos were created in collaboration with CRG Homecare .

Meet our carers - Curado

Meet Kimberly, Connar, Ada, Augustine, Juliana and Gloria, who discuss working in mental health care and share their tips and advice for others interested in a career in adult social care. This video was created by Curardo , who specialise in making a difference in the lives of people with mental health needs.

Direct care roles

These roles involve directly working with people who need care and support

Positive behaviour support assistant, Clara Burfutt

Clara supports adults with mental health conditions who also have behaviour that challenges.

Mental health support worker, Darren Sewell

Darren supports two people with mental health conditions in a small care home.

Management roles

Care supervisor, emma stowell.

Emma supervises a team who provide care to people in their own home.

Senior Care Assistant, Luke Britton

Luke works in a residential home for older people and is responsible for ensuring his shift runs smoothly.

Assistant manager, Aiste Trimakaite

Aiste supports with the management of a care home for people with mental health conditions.

Operational Lead, Adam Skerritt

Adam is responsible for the day to day running of the children and young people’s services in his local council.

New Projects Manager, Andrea Wiggins

Andrea works in a team who set up special services for people with learning disabilities and/ or autism.

Locality Manager, Chris Hocking

Chris manages a team of 30 care workers who go out and provide care in people’s homes.

Intervenor Service Manager, Deb O’Shea

Deb manages a team who support people with sight and hearing impairments, ensuring they get the services they need.

Registered Manager, Linda Douglas

Linda works for a domiciliary care provider and she supports a team with induction, supervision and training.

Registered Manager, Linda Pitt

Linda works in a care home for older people and is responsible for the day to day running of the home.

Home Care Manager, Liz Ingham

Liz works for her local council and assesses people who need care and support in their own home.

Managing Director, Michelle Apostol

Michelle is responsible for ensuring the organisation and its staff deliver high quality care.

Team Manager, Mike Maden

Mike manages three residential care homes for people with learning disabilities including organising activities for residents.

Head of Care Services, Nicola Taylor

Nicola is part of a development team who are building a new care service to support people with dementia.

Cluster Manager, Sally Gibbons

Sally manages a team of care workers who offer care, outreach and supported living services in the community.

Deputy Manager, Sophie Layton

Sophie supports the manager of a care home for people with learning disabilities with the day to day running.

Founder and Manager, Chris McGowan

Chris is the founder of a care agency who connect self-employed carers with people who need care and support at home .

Other social care roles

Support coordinator, julie king.

Julie works in a supported housing scheme and is responsible for the wellbeing and safety of residents who live there.

Team Leader and Moving and Handling Trainer, Nicola Pullen

Nicola has taken on additional responsibilities in her role to deliver moving and handling training to other staff.

Training Manager, Adrian Muir

Adrian organises and delivers training for care workers. He also runs induction sessions for new workers and thinks of new ways to run training.

Independent Living Advisor, Martin Hayden

Martin provides support and advice to people who need care and support to help them access the services they need.

Office Manager, Julie Allen

Julie’s office role covers a range of tasks including training and supervision, interviews, sorting out wages and creating care plans.

Payroll Officer, Charlotte Truslove

Charlotte supports people who employ their own care and support to manage their finances and pay their carers.

Sales and Marketing Manager, Mike Allistone

Mike is responsible for promoting seven care services to potential customers.

Tenancy Sustainment Officer, Georgina Towers

Georgina visits vulnerable people in the community to help them remain their homes.

Independent Living Coordinator, Simon Ward

Simon supports disabled people to access the right services to help them live more independently.

Learning and Development Manager, Gemma Tomkinsmith

Gemma organises and delivers learning and training to ensure staff have the right skills and knowledge.

HR and Care Manager, Melissa Hall

Melissa works for a care agency and is responsible for recruiting self-employed carers.

Learning and Development Manager, Carol Glanfield

Carol identifies training needs, organises and delivers high quality training to ensure her colleagues have the knowledge and skills they need to deliver high quality care.

Regulated roles

Occupational therapist, penny marks-billson.

Penny supports people who have just left hospital or are at risk of going into hospital to help them live at home.

Occupational Therapist, Hanna Munro

Hanna supports six care homes with fall prevention, wheelchair and seating assessments, daily living equipment and rehabilitation.

Social Worker, Jane Haywood

Jane supports older people when they come out of hospital, and also coaches and mentors a social work team.

Mental Capacity Act (MCA)

Information, guidance, and accredited training for care and health staff to support, protect and empower people who may lack capacity.

Introducing the MCA

Why the MCA matters to everyone working in care, health, housing and other sectors.

MCA in practice

Guidance on assessing capacity and supporting decision making.

MCA training

Accredited training, open or tailored courses, plus free learning resources.

Liberty Protection Safeguards

Guidance and updates on the implementation of Liberty Protection Safeguards.

Deprivation of Liberty

Guidance on understanding and managing DoLS.

Independent Mental Capacity Advocate

Understanding the role of mental capacity advocates.

National Mental Capacity Forum

The National Mental Capacity Forum is a joint Ministry of Justice and Department of Health and Social Care initiative. Its purpose is to advocate at a national level for the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA).

Social Work Practice with Carers

Case Study 1: Eve

Download the whole case study as a PDF file

Eve is a carer for her father, who has early stage vascular dementia and numerous health problems. She has two children: a son, Matt, who is 17 and has Crohn’s disease, and a daughter, Joanne, who is 15.

This case study considers issues around being a ‘ sandwich carer’ – that is, caring for both a parent and a child – maintaining employment and working with a whole family including family group conferences, as well as the impact of dementia and the role of assistive technology .

When you have looked at the materials for the case study and considered these topics, you can use the critical reflection tool and the action planning tool to consider your own practice.

- One-page profile

- Support plan

Transcript (.pdf, 61KB)

Name : Eve Davies

Gender : Female

Ethnicity : White British

Download resource as a PDF file

First language : English

Religion : None

Eve lives in a town. She has two children, a son, Matt, who is 17 and has Crohn’s disease, and a daughter, Joanne, who is 15. Eve’s mother died four years ago, and her father, Geoff, lives close by. Geoff has early stage vascular dementia and numerous health problems relating to a heart attack he had two years ago. Eve works part time in an administration role at a local college. She has lost contact with her friends and lost touch with her hobbies (swimming and singing in a choir) because she has prioritised her family.

Matt is at college studying for his A levels. He is frustrated that his illness is interfering with all aspects of his life. Joanne is becoming more withdrawn and resentful as an increasing amount of Eve’s time is taken up with other family members. Geoff has started to neglect himself at home, and is finding it more difficult to carry out daily tasks. Following a social care assessment, he has a befriending service stop by every week and a homecare team each morning to check he’s ok and supervise his medication, which Eve sets up for them. The care agency have reported that there’s a possibility Geoff has been accessing his medication and taking it. Geoff remains adamant that he is fine, and with Eve’s support he can manage.

Eve is feeling stressed and isolated. She wants to increase her working hours for financial reasons, but is unable to as she needs to be available for Geoff. Eve is having problems with sleeping and feels generally run down, and recently has been suffering from stomach pain and nausea. She says that she feels ‘withdrawn from normal life.’ She tried attending a carers’ group but found that listening to other carers’ problems highlighted her own. Instead, she sometimes uses an online forum at night when everyone else is asleep.

Eve was recently referred by her GP for a carer’s assessment. You have been out to see her twice and talked to her children. You have completed the assessment and support plan with her.

Back to Summary

What others like and admire about me

Good mum (mostly!)

I’m very organised

People can count on me

I help people out

I’m a good singer

What is important to me

My kids – I want them to be happy

Family time

Dad staying at home – I promised Mum

My job – people I work with

Health – exercise, sleep!

Just to know I’m not on my own

How best to support me

Listen to me and include me in your network

A bit of ‘me time’ to breathe – see friends, swimming, choir

Be honest about what you can do and do what you say you will

Don’t lumber your problems on me when there’s nothing I can do

Talk to me about me, not just about caring

Let me know who to contact

Don’t give me loads of information

Emails not phone please

Don’t arrange meetings when I’m at work

Help me plan so I can do everything!

Date chronology completed 15 February 2016

Date shared with person 15 February 2016

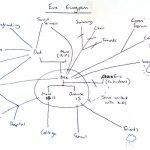

Eve’s Ecogram

Name Eve Davies

Address 1 Fir Avenue, Moreton, ZZ1 Z11

Telephone 012345 123456

Email [email protected]

Gender Female

Date of birth 15.2.1974 Age 42

Ethnicity White British

First language English

Religion None

GP Dr Tailor, Parkside Surgery

How would you like us to contact you?

Do you need any support with communication?

About the person/ people I care for

My relationship to this person Daughter

Name Geoff Davies

Address 1 Pine Avenue, Moreton, ZZ1 Z22

Telephone 012345 234567

Gender Male

Date of birth 8.1.1943 Age 73

Religion Baptised C of E

Please tell us about any existing support the person you care for already has in place. This could be home care, visits or support from a community, district or community psychiatric nurse, attending any community groups or day centres, attending any training or adult learning courses, or support from friends and neighbours.

Home care every morning for medication and check up

Befriending service 2 hours a week

My relationship to this person Mother

Name Matt Sanderson

Address 1 Fir Avenue, Moreton, ZZ1 Z22

Date of birth 26.7.1998 Age 17

Goes to college (doing A levels)

GP and nurse at the surgery

Consultant at the hospital

The things I do as a carer to give support

Please use the space below to tell us about the things you do as a carer (including the emotional and practical support you provide such as personal care, preparing meals, supporting the person you care for to stay safe, motivating and re-assuring them, dealing with their medication and / or their finances).

Dad has early stage vascular dementia and numerous health problems relating to a heart attack he had two years ago. He has started to neglect himself at home, and is finding it more and more difficult to carry out daily tasks. He gets confused with cooking or tasks like making a meal. Sometimes Dad has trouble remembering words and this makes him feel cross. On occasion he does experience short bursts of sudden confusion, which can be frightening for other family members.

Following a social care assessment, he has a befriending service stop by every week and a homecare team each morning to check he’s ok and supervise his medication.

This is what I do for Dad:

- Preparing Dad’s medication for the day – setting out in reminder containers

- Greeting care workers in the morning

- Remind Dad about having a wash

- Leave lunch in fridge

- Remind Dad about appointments

- Visit in the evening and cook dinner

- Sort out problems with the care agency

- Do shopping, cleaning, laundry

- Collect medication

- Check for medical appointments/ reviews

- Take Dad to appointments

- Sort out Dad’s mail – pay bills

- Fix things round the house

- Sort out extra care if Matt is in hospital

Matt has Crohn’s disease. He is at college studying for his A levels. He is doing well but his illness does interfere with his life and he can get frustrated about this. He wants good grades to be able to become a journalist and move abroad. It is embarrassing for him that he has to frequently rush to the toilet, and occasionally he is incontinent. Matt has regular relapses. This causes him to lose a lot of weight and he has been in hospital three times in the last year and missed college.

This is what I do for Matt:

- In the morning, make special lunch and ensure that he has his emergency bag (extra clothing, wipes, plastic bag and air freshener)

- Remind him about his weekly blood test appointment.

- Extra washing

- Help with homework

- Transporting Matt to hospital/GP/nurse appointments.

I also look after my daughter Joanne who is 15.

How my caring role impacts on my life

Please use the space below to tell us about the impact your caring role has on your life.

Like all working mums I have a lot on. As I have had to do more for Dad, it has got more difficult to juggle family chores and work.

I want to increase my working hours for financial reasons but I don’t see how I can at the moment, as Dad’s care needs are increasing and I need to be available for him. I’ve had to take some flexible working hours recently to cover last minute changes in arrangements for Dad’s care. I frequently have to take phone calls at work about care arrangements. I am concerned that I won’t be able to keep working and we need the money.

I’m worried that Dad isn’t eating properly. The care agency have reported that the medication audit has shown that Dad might have been taking his medication at the wrong times. Dad doesn’t want to talk about longer term planning and making advanced decisions. He does not want any more social care provision in the house. This really worries me particularly as Dad will need more help as time goes on. Also if Dad suddenly needed a lot more help or I was unwell then I am not sure how we would manage.

I want Matt to be able to manage his illness better so that he is happier and able to do the things he wants. As I have had to spend more time with Dad and Matt, my daughter Joanne has become more distant. She finds it difficult that we need to work around what Matt needs, for example for meals. Joanne has always been helpful but has become more withdrawn and resentful. She has started to hang around with older teenagers, and I’m worried they might be ‘leading her astray’. She has had a few letters from school mentioning poor attendance and a drop in her grades. I feel like I don’t have time at the moment to be a good mum.

I’m having problems with sleeping and feel generally run down, and recently I have had to see the GP about stomach pain and nausea, which she thinks is to do with stress. I feel like I don’t have any time now to just breathe and am withdrawing from normal life. I don’t currently have time to exercise – I used to swim, or to sing in the choir. I’ve also lost contact with friends so I feel quite isolated.

What supports me as a carer?

Please use the space below to tell us about what helps you in your caring role.

I sometimes go on an online carers’ forum at night when everyone else is asleep and that’s quite helpful. I did try attending a carers’ group but it got me down listening to other people’s problems.

Work gives me a bit of a break from caring and my boss has so far been quite supportive with flexible working though I don’t want to push it.

Matt’s nurse at the GP surgery has been really helpful with information and support. Matt gets on with her well.

My feelings and choices about caring

Please use the space below to tell us about how you are feeling and if you would like to change anything about your caring role and your life.

It’s my choice to care for my family and I want to keep on doing that, and be a good mum and a good daughter.

If I knew that Dad was getting the care he needs and that we had a plan for the future then I would manage much better.

At the moment I’m feeling stressed and quite overwhelmed. There’s always something else to sort out. I feel like I don’t have anyone to support me. I miss my Mum and worry about whether I’m looking after my Dad as well as she did.

I want to know my family is ok. I don’t want to stop looking after my kids and my Dad.

I want to be able to manage my different roles at home and at work, and to do things well.

I want to have more time with my children and we want more time as a family.

I would love to increase my hours at work.

I’d like to start swimming and join the choir again. I’d like to see friends sometimes.

I do need more sleep.

Information, advice and support

Let us know what advice or information you feel would help you and what sort of support you think would be beneficial to you in your caring role.

Someone to talk to Dad about getting the care he needs – particularly to ensure he takes the right medication and that he eats enough.

Some help with planning Dad’s care in case there is a crisis, and to plan ahead for what he will need in the future.

Someone to check on Dad when I’m at work.

A break – just to be free without interruptions.

Some back-up so that I am not always on call.

Someone to talk to about how to manage all of this.

Someone for Joanne to talk to if she wants to.

Someone to support Matt to manage his illness so he can achieve his aims.

To be used by social care assessors to consider and record measures which can be taken to assist the carer with their caring role to reduce the significant impact of any needs. This should include networks of support, community services and the persons own strengths. To be eligible the carer must have significant difficulty achieving 1 or more outcomes without support; it is the assessors’ professional judgement that unless this need is met there will be a significant impact on the carer’s wellbeing. Social care funding will only be made available to meet eligible outcomes that cannot be met in any other way, i.e. social care funding is only available to meet unmet eligible needs

Date assessment completed 15 February 2016

Social care assessor conclusion

Eve is providing significant support to her father and her two children, one of whom has Crohn’s disease. Eve also works part-time. Eve’s father has some support from home care and a befriending service. Her son has support from health services. Eve is very organised, and juggles chores and work well. However, she says that she is starting to feel increasingly stressed and this is having an impact on her health. She is also quite isolated and has no time at present to have a break from caring. Eve would like to continue supporting her family and increase her working hours, as well as having some time for her own interests. It is important to Eve that her father remains at home and is safe, and that her children are happy. Eve would benefit from support to enable her to manage the demands on her, and to have some time for herself. She would also benefit from some emotional support for her and for her family. This will enable her to continue as a carer and to improve her health and wellbeing.

Eligibility decision Eligible for support

What’s happening next Create support plan

Carry out assessment for Mr Geoff Davies

Completed by

Organisation

Signing this form (for carer)

Please ensure you read the statement below in bold, then sign and date the form.

I understand that completing this form will lead to a computer record being made which will be treated confidentially. The council will hold this information for the purpose of providing information, advice and support to meet my needs. To be able to do this the information may be shared with relevant NHS Agencies and providers of carers’ services. This will also help reduce the number of times I am asked for the same information.

If I have given details about someone else, I will make sure that they know about this.

I understand that the information I provide on this form will only be shared as allowed by the Data Protection Act.

Date of birth 15.2.1974 Age 42

Support plan completed by

Support Plan

Date of support plan: 15 February 2016

This plan will be reviewed on: 15 February 2017

Signing this form

Eve has given consent to share this support plan with Mr Davies. This support plan will link into his assessment.

Sandwich caring

The Care Act places a duty on local authorities to assess adult carers, including parent carers of disabled and other children in need, before the child they care for turns 18, so that they have the information they need to plan for their future. Guidance, advocating a whole family approach, is available to social workers (LGA 2015, SCIE 2015, ADASS/ADCS 2011).

- Carers UK (2012) Sandwich caring

- Circle (2018) Supporting carers to work and care

- Think Local Act Personal (2017) Supporting working carers

- Mumsnet for the Care Quality Commission August (2014) Care Quality Commission: Sandwich Generation Survey Summary Report

- Institute for Public Policy Research (2013) The sandwich generation: older women balancing work and care

- Carers UK (2014) Carers at breaking point

- Blog: Impact of cuts

Carers’ employment

Research shows that both emotional and practical support from social workers are valuable, for example when looking at what was valued by the mothers of transition-age children with mental illness (Gerten and Hensley 2014) and by men as caregivers to the elderly (Collins 2014).

- Skills for Care (2013) Balancing work and care

- Carers UK (2015) Caring and isolation in the workplace

- Carers UK (2014) The case for care leave

- Carers UK (2014) Supporting employees who are caring for someone with dementia

- Carers UK (2013) Supporting working carers

- NIHR (2014) Improving employment opportunities for carers: identifying and sharing good practice

- Department of Health (2015) Pilots to understand how to support carers to stay in paid employment

- Tool 1: Support for carers in employment

Life course and whole family approaches

The whole family approach is a strong theme in the research (LGA 2015) along with relationship based practice (SCIE 2016, Cooper 2015, Wilson et al 2011, Ruch et al 2010). Family group conferencing, along with mediation as whole family approaches, were found to have particular applicability to adult safeguarding social work. (SCIE 2012).

- Beth Johnson Foundation (2014) A life course approach to promoting positive ageing

- SCIE (2012) At a glance 62: Safeguarding adults: Mediation and family group conferences

- Hobbs A and Alonzi A (2013) Mediation and family group conferences in adult safeguarding, Journal of Adult Protection, 15(2) , pp.69-84

- Carers Trust Whole family approach – practice examples

- Tool 2: Family group conferences

Assistive technology

Evidence points to the need for social work teams are to have good information about the support available to carers. National materials offer a valuable resource to social workers seeking to research how to work with their clients and their carers which can be supplemented locally and from the active contributions of the ‘online’ community (Young Sam Oh 2015).

- SCIE (2010) At a glance 24: Ethical issues in the use of telecare

- Carers UK and Tunstall (2013) Potential for Change: Transforming public awareness and demand for health and care technology

- Carers UK and Tunstall (2012) Carers and telecare

- Carers UK (2012) Future care: Care and technology in the 21st century

- SCIE (2010) Telecare videos

- Tool 3: Ethics of assistive technology

Research suggests an assets or strengths based approach to social work support with the person and their family and/or network of support. The Manual for good social work practice (DH 2015) uses a timeline as a model that can underpin how the social worker supports and intervenes, from early preventative measures through various stages of loss towards end-of-life. Three critical points on the timeline – diagnosis, taking up active caring and the decline of the person’s capacity – are identified. It is important for social workers to assess the carers needs, sustain the carers own identity, develop and maintain their network of support and resources, and access financial and legal advice.

- SCIE Dementia Gateway Department of Health (2015) TCSW (2015) A manual for good social work practice: Supporting adults who have dementia , The College of Social Work

- Carers Trust (2014) The Triangle of Care: Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice for Dementia Care

- Carers Trust (2013) A Road Less Rocky – Supporting Carers of People with Dementia

- Alzheimer’s Research UK (2015) Dementia in the family: the impact on carers

- Tool 4: Triangle of care – self-assessment for dementia professionals Carers Trust (2014) The Triangle of Care: Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice for Dementia Care (Page 22 Self-assessment tool for organisations)

Tool 1: Support for Carers in Employment

You can use this tool with carers to think about what would support someone to manage work and caring responsibilities.

This tool is based on research about what helps carers who are working (Carers UK (2015) Caring and isolation in the workplace).

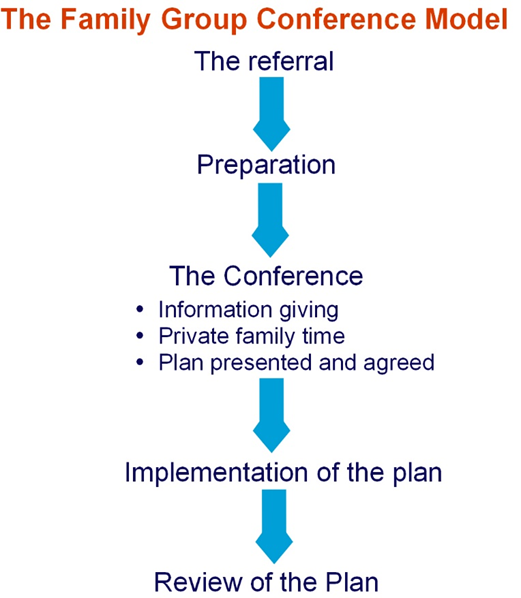

Tool 2: Family Group Conference

This tool sets out the process for a Family Group Conference. You can use it to plan and hold a conference.

The Family Group Conference process

Stage 1: The referral

Whether or not a family group conference takes place is a decision made by the family. Under no circumstances can a family be made or forced to have a family group conference.

Once a referral for a family group conference is made, there will need to be a co-ordinator to liaise with the family.

The co-ordinator helps the family to plan the meeting and chair the meeting. The co-ordinator is different from the referrer and acts as a neutral person. The co-ordinator will not influence the family to make a particular decision but will help them to think about the decisions that need to be made. Families should be offered the opportunity to request a co-ordinator who suitably reflects their ethnicity, language, religion or gender, and the family’s request should be accommodated wherever possible.

Stage 2: Preparation

The co-ordinator organises the meeting in conjunction with the family members and other members of the network. This can include close friends.

- The co-ordinator discusses with the person with care and support needs how they can be helped to participate in the conference and whether they would like a supporter or advocate at the meeting . The supporter/advocate will then meet with them in preparation for the meeting.

- The co-ordinator meets with members of the family network, discusses worries or concerns, including how the family group conference will be conducted, and encourages them to attend.

- the wellbeing concerns which need to be considered at the family group conference. This includes identifying any bottom line about what can, and, importantly, cannot be agreed as part of the plan from the agency’s perspective.

- services that could help.

- The co-ordinator negotiates the date, time and venue for the conference, sends out invitations and makes the necessary practical arrangements.

Stage 3: The conference

The family group conference follows three distinct stages.

a) Information giving

This part of the meeting is chaired by the co-ordinator. They will make sure that everyone is introduced, that everyone present understands the purpose and process of the family group conference and agrees how the meeting will be conducted including, if felt helpful by those present, explicit ground rules. The service providers give information to the family about:

- the reason for the conference;

- information they hold that will assist the family to make the plan;

- information about resources and support they are able to provide;

- any wellbeing concerns that will affect what can be agreed in the plan; and

- what action will be taken if the family cannot make a plan or the plan is not agreed.

The family members may also provide information, ask for clarification or raise questions.

b) Private family time

Agency staff and the co-ordinator are not present during this part of the conference. Family members have time to talk among themselves and come up with a plan that addresses concerns raised. They will identify resources and support which are required from agencies, as well as within the family, to make the plan work.

c) Plan and agreement

When the family has made their plan, the referrer and the co-ordinator meet with the family to discuss and agree the plan including resources.

It is the referrer’s responsibility to agree the plan of action and it is important that this happens on the day of the conference. It should be presumed that the plan must be agreed unless it puts anyone at risk of significant harm. Any reasons for not accepting the plan must be made clear immediately and the family should be given the opportunity to respond to the concerns and change or add to the plan.

It is important to ensure that everyone involved has a clear understanding of what is decided and that their views are understood.

Resources are discussed and agreed with the agency concerned, and it is important that, at this point, timescales and names of those responsible for any tasks are clarified. Contingency plans, monitoring arrangements and how to review the plan also need to be agreed.

The co-ordinator should distribute the plan to family members involved and to the social worker and other information givers/relevant professionals.

1.3.5 Stage Three: Implementation of the Plan

It is essential that everybody involved implements their parts of the plan within agreed timescales and communicate and addresses any problems that arise.

1.3.6 Stage Four: Review of the plan

There should be a clear process for reviewing the implementation of the plan. A review family group conference or other meeting should be offered to the family so they can consider how the plan is working, and to make adjustments or change the plan if necessary.

This information is based largely on the Family Rights Group’s Family Group Conference Process

Tool 3: Ethics of using assistive technology

This tool highlights the ethical issues of using assistive technology. You can use it to consider when assistive technology would be beneficial for someone, and to reflect on the benefits and drawbacks of it more generally.

What are the ethical issues about using assistive technology (AT) to support carers?

This tool is based on SCIE At a glance 24: Ethical issues in the use of telecare

Download The Triangle of Care as a PDF file

The Triangle of Care Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice in Mental Health Care in England

The Triangle of Care is a therapeutic alliance between service user, staff member and carer that promotes safety, supports recovery and sustains wellbeing…

- Equal opportunities

- Complaints procedure

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookie policy

- Accessibility

Hull Adult Social Care APPP

Case Studies

These case studies have been taken from the Care and Support Statutory Guidance (Department of Health and Social Care) . They should be read in conjunction with the relevant chapter.

Preventing, Reducing or Delaying Needs

Market shaping and commissioning of adult care and support, assessment and eligibility, independent advocacy, deferred payment agreements, care and support planning, personal budgets, direct payments.

Review of Care and Support Planning

Safeguarding

Integration, cooperation and partnerships.

Transition to Adult Care and Support

Delegation of Local Authority Functions

Ordinary residence, cross border placements, case study: linkage programme.

The LinkAge programme aims to promote and enhance the lives of older people (55+ years old) through a range of activities, from walking groups to coffee mornings, through a number of older people-led ‘hubs’ across the city. The main aim is to bring those people that feel socially isolated and lonely into their local communities. In an evaluation of a new hub there was significant improvement on a friendship scale with scores moving from people feeling isolated or with a low level of social support at the beginning of the hub to very or highly socially connected at follow up.

Eileen (85) said:

“I look forward to Fridays each week and enjoy the social aspect of the club too.”

“If it wasn’t for LinkAge I don’t quite know what would have happened. It’s made life bearable, well more than bearable, it’s made it life.”

Case Study: Older man living alone

An older man lives alone with some support from his daughter who works full-time. He needs occasional personal care to remain living independently with dignity, and it is likely that these needs will increase. He has lost contact with family and friends following his wife’s death and rarely goes out without support from his daughter who is restricted to taking him out at weekends because of work commitments.

An assessment would consider all of his needs, including those currently being met by his daughter, along with the outcomes he wishes to achieve. A separate carer’s assessment offered to his daughter (or a combined assessment if both father and daughter agreed) would establish the daughter’s willingness and ability to care and continue to care and how best to promote her own wellbeing, for example by having regard to the outcomes she wishes to achieve. This joint assessment would look at issues such as the possible impact on the daughter of supporting her father while in full-time employment as well as the father’s isolation, ability to connect with others or be an active citizen.

Community groups, voluntary organisations, and buddying services could support the father to reduce the social isolation that he may be feeling and maximise opportunities to look after his own health and wellbeing and participate in local community activities. This, in turn could lessen the impact of caring on his daughter and enable her to continue to support her father effectively alongside paid employment. Such support can be identified/suggested alongside other, perhaps more formal services to meet personal care needs, and can be an effective way of promoting wellbeing. In this example, the aspects of wellbeing relating to social wellbeing and family relationships might be promoted.

Case Study: Derby City Council’s Customer Journey

Derby City Council used co-production to develop clear and easy to use customer information to support their customer journey for self-directed support. Information that has been produced includes an assessment form, support planning tools for people using services, customer leaflets and a staff handbook. A small project team held discussions and workshops to identify information that needed improving to be clearer and suggestions for improvement, e.g. a new assessment form. Staff working in adult social care assessment teams had training on how to make best use of the new suite of information.

The inclusive approach taken to re-designing the information took longer than an internally managed process, but has resulted in better information, informed people using services and bringing their own perspective and experience. The co-production approach led to the development of key principles which can be used in other areas of communication. The approach is being continued.

Case Study: Midland Heart’s Reablement Service

At 82, Beryl was diagnosed with stomach cancer and admitted to hospital. As a result of a major operation, she now has a permanent colostomy bag. After only a month Beryl was successfully discharged from hospital to her own home with a reablement package from Leicester City Council and support from the housing association, Midland Heart, to help her regain her independence.

If Beryl had not received this support, she would have been discharged to a more costly care home. The reablement service ensured that Beryl’s home was suitably adapted for her return, which allowed a speedy discharge and avoided the need for institutional care. The support service has assisted her attendance at medical appointments with her GP and monitored the impact of her medication.

Case Study: Mr A, living alone at home

Mr A is a 91 year old man who lives alone with his dog in his house. He is usually independent, is a passionate cook and enjoys socialising. He drives a car. Whilst out walking his dog he suffered a stroke, he fell, causing a fractured neck of femur. He was admitted to hospital and underwent surgery for a hip replacement which meant he had to follow hip precautions for 6 weeks.

The stroke had left him with slight left-sided weakness and problems with concentration, sequencing and attention. He was transferred to a community hospital for rehabilitation where the physiotherapists (PTs) and occupational therapists (OTs) worked on mobility, transfers, personal care following hip precautions, stair climbing and kitchen tasks. Cognitive screens were completed and the OTs targeted their input on helping improve concentration, sequencing and attention.

Mr A was discharged, independently mobile using a frame, independent transferring using equipment and stair climbing with supervision. He was discharged home with 4 calls per day from BEST plus (Bradford Enablement Support Team). Joint sessions between the PTs and OTs and BEST plus were completed to work on the following:

- practising walking safely indoors using 2 walking sticks

- increase hip strength through exercises

- to be safe and independent washing and dressing

- to be safe and independent preparing hot drinks and simple snacks and transport safely using trolley

The above goals were achieved and new goals were set in consultation with Mr A:

- to be safe and independent walking outdoors using 2 sticks

- to be safe and independent bathing using bath lift

- to be safe and independent preparing hot meals from scratch

- to be safe and independent completing shopping using Access bus

- to be safe and independent walking dog short distances using 4 wheeled walker.

After 6 weeks of continued BEST plus input in Mr A’s home, he was able to achieve all of his goals and all Social Services input was withdrawn. Aspects of Mr A’s wellbeing have been promoted including physical wellbeing, social wellbeing, and control over day-to-day life.

Example: Ensuring provision of appropriate services

Young people move from children’s to adult care and support or providing support for situations where young carers become adults

For instance, many young people with learning disabilities leave full-time education at around this age and require new forms of care and support to live independently thereafter. Ensuring that services are made available to meet those needs is better for the quality of life of the young person in question. This could include things such as employment support, training, developing friendships or advice on housing options. It is equally important to think about ways of supporting carers at this time: some parent carers need extra support to juggle caring and paid work after their child leaves full time education. Loss of paid employment can have a significant impact on the carer’s wellbeing and self-esteem as well as a significant impact on the family’s financial circumstances. Similar issues can affect young carers. Taking a whole family approach to care and support planning that sets out a ‘five-day offer’ or appropriate supported living options for a young person, and support for a carer to manage an increased caring role (that allows them to stay in paid work if they wish to do so) can help families manage the transition and save money by avoiding unwanted out-of-county placements.

Case Study: Facilitating the market

Warwickshire Council’s Market Position Statement for Older People identified a significant growth in the number of people living with dementia in the county, coupled with a declining trend in the number of people accessing traditional day services in the previous 4 to 5 years. Day services provide stimulation for the person living with dementia as well as a break for the person’s carer.

Following this the Council undertook a full review of Dementia Community Support. This included evaluating the role of services funded by the NHS and the Council and also those provided directly by the voluntary and community sector.

The Council held an engagement event to establish what customers and carers want dementia Community Support services to look like and deliver. This identified the gaps between supply and demand in more detail and at a local level. The event also gathered information from providers and voluntary and community groups about the challenges of delivering services. Providers identified commissioning models which promote strong and stable service delivery whilst still allowing flexible responses to meet individual needs as particularly useful. As a result of this activity, the Council procured a new service model for Dementia Community Support. The model will include information and advice, community services, building-based respite and specialist support.

Case Study 1: John (eligible)

John is 32 and has been referred by his mother for an assessment, who is concerned for John and his future. John is unemployed and lives with his mother and she is getting to an age where she realises that she might not be able to provide the same level of care and support for her son as she has done so far. John is able to manage his own personal care, but his mother does all the housework for both of them. John feels increasingly isolated and will not leave the house without his mother. It is important to John that he is intellectually stimulated and there is a chess club nearby which he would like to join, but John does not feel confident about this due to his anxiety in social situations.

Adult on the autistic spectrum.

John has severe difficulties socialising and co-operating with other people.

He only has transactional exchanges and cannot maintain eye contact. John knows that others feel uneasy around him, and spends a lot of his time alone. As a result, John is unable to achieve the following outcomes: Developing and maintaining family or other personal relationships and making use of necessary facilities and services in the community.

Impact on wellbeing

John is too anxious to initiate developing friendships on his own although he would like to and he feels lonely and depressed most of the time. His nervousness also affects his ability to take advantage of facilities in the community, which could help him feel less lonely. Feeling anxious and lonely has a significant impact on his wellbeing

Decision: Eligible

Next actions.

John’s local authority thinks John’s needs are eligible. Both John and the local authority agree that the most effective way of meeting John’s needs is to develop his confidence to join the chess club. John uses his personal budget to pay for a support worker to accompany him to an autism social skills group, and to the chess club and to travel with him on the bus to get there.

John’s local authority notes that John’s mother could need support too and offers her a carer’s assessment.

Case study 2: Dave (not eligible)

Dave is 32 and has been referred by his mother for an assessment, who is concerned for Dave and his future. Dave lives with his mother and she is getting to an age where she realises that she might not be able to provide the same level of care and support for her son as she has done so far.

Dave is able to manage his own personal care, but his mother does all the housework for both of them. Dave also works, but would like to get a job that is a better match for his intellectual abilities as his current job does not make the most of his numerical skills. Dave’s social contact is mainly online because he feels more comfortable communicating this way and he spends a lot of time in his room on his computer.

Dave struggles severely in social situations leading to difficulties accessing work and cooperating with other people. He only has transactional exchanges with others and cannot maintain eye contact. Dave knows that others feel uneasy around him and spends a lot of his time alone.

Dave is not in ideal employment, but has access to and is engaged in work. This has some impact on his wellbeing but not to a significant extent.

Dave prefers to socialise with people online. It emerges from conversations with Dave that he has access to those personal relationships that he considers essential. Dave is contributing to society, has contact with others, is in employment and is able to look after himself.

Decision: Not Eligible

Dave has difficulties doing some of the things that many other people would think should be a natural part of daily living and he is unable to participate in recreational activities in a conventional sense. Those aspects of his wellbeing that are affected by the needs caused by his autism are not so significantly affected that Dave’s overall wellbeing is at risk.

The local authority decides that Dave’s needs are not eligible, because they do not have a significant effect on his wellbeing despite his mother’s concerns.

The local authority records Dave’s assessment and sends him a copy. They include information about a local autism support group. Dave’s local authority notes that Dave’s mother could well need support and offers her a carer’s assessment.

Case Study – Carer: Deirdre (not eligible)

Deirdre is 58 and has been caring for her neighbour for the past 6 years. Deirdre has been coping with her caring responsibilities, which include checking in on her neighbour, doing her shopping and cleaning and helping her with the cooking every other day.

Deirdre works 20 hours a week at the local school, and she is also helping her daughter by picking up her grandchild after school. Deirdre’s son is concerned that she is taking on too much and notices that she is tired. Deirdre’s son persuades her to ask the local authority for a carer’s assessment.

Caring responsibilities

Neighbour with COPD.

Deirdre enjoys the variety that her working life and caring role provide. She would like to be able to spend more time with her grandchild in the afternoons, but recognises that there is a balance between doing this and caring for her neighbour. Deirdre’s needs impact on the following outcomes:

- carrying out caring responsibilities the carer has for a child

- engaging in recreational activities

Deirdre’s needs are impacting on a few outcomes.

Deirdre enjoys her caring responsibility for her grandchild and would like more free time. On the other hand, her caring roles are fulfilling so although Deirdre is tired at the end of the day, her local authority does not think her wellbeing is significantly affected.

The local authority decides that Deirdre is not eligible because her wellbeing is not significantly affected.

Next actions

The local authority recognises that Deirdre could do with some advice to help her manage her day so that she can find some time for herself and so she does not get tired. They advise on how she may reduce some of her tasks such as sitting down with her neighbour to order their food shopping online rather than carrying them home. They make contact with a local carers’ organisation and the local authority makes sure Deirdre is able to access it. The organisation is able to provide additional advice.

Case study – Carer: Sam (eligible)

Sam is 38 and cares for his mother who has early-stage dementia. Sam’s mother has telecare, but he still checks in on her daily, and does her shopping, cooking and laundry. Sam is a divorced father of 2 children, who live with him every other week. Sam works fulltime in an IT company and has come forward for an assessment as he is starting to feel unable to cope with his various responsibilities in the weeks when he looks after his children. Sam has made an arrangement with his employer that he can work longer hours on the weeks when the children are with their mother and fewer when he has the children.

Mother with early stage dementia.

Sam wants to spend more time with his children and for instance be able to free up an hour in the afternoon to help them with their homework, so it doesn’t have to be done in the evening when the children are tired. Sam’s needs impact on the following outcomes:

Sam’s responsibilities impact on a few important outcomes. Sam is starting to feel like he is failing as a parent and it affects the relationship he has with his children, his ex-wife, and his mother. He also worries that his ability to stay in work would be in jeopardy unless he receives support. Sam seems quite stressed and anxious.

The local authority decides that Sam’s fluctuating needs are eligible for support, because it perceives that they have a significant impact on his wellbeing. If the local authority supports Sam to maintain his current role, everyone is better off, because Sam can stay in employment, sustain his family relationships and provide security for his mother.

The local authority gives Sam a direct payment which he uses to pay for a care worker to come in for 3 days every other week to check on his mother and make her a meal. This gives Sam more time to spend with his children, doing homework with them and spending some more relaxed time with them.

The local authority directs Sam to a carers’ organisation which provides Sam with information about his rights at work and how to speak to his employers.

Case Study: Stephen who has an acquired brain injury

Stephen sustained a brain injury in a fall; he has completed 6 months in a specialist residential rehabilitation setting and the next step is an assessment of need for his continuing support.

Prior to this, the social worker telephones Stephen’s treating clinician who confirms that because of his brain injury, Stephen lacks insight into the effects this has had on him and he also has difficulty processing lots of information quickly – this is a common symptom of brain injury.

Therefore the social worker decides on an initial short meeting to determine Stephen’s needs and knows her first step will be to evaluate if Stephen has difficulty understanding and therefore being involved in the assessment process. If so, support could come from a carer, family member or friend or Mental Capacity Advocate, as she is aware lack of insight does not necessarily determine lack of capacity.

The social worker notes that Stephen is able to retain information about who she is and why she is meeting with him. He is articulate and can converse well about his plans for the future which includes detailed plans to meet up with friends and return to work again. However, a pre-assessment conversation with his mother, confirms that his friendship group has significantly diminished as his friends find it difficult to understand the differences in his behaviour since his fall and doubts whether he will be able to return to full-time employment. The social worker judges that because Stephen lacks insight into his personal relationships and future plans, he may well also have trouble estimating his true care and support needs. At this point the social worker decides that Stephen would have substantial difficulty in being fully involved in the rest of the assessment process and would therefore benefit from assistance.

Stephen is adamant that he wants to act and make decisions independently of his mother, though he is happy for her to inform the assessment process. The social worker decides that Stephen’s mother would not be an appropriate person under the Care Act to support his involvement in the needs assessment. The social worker talks to Stephen about how an independent advocate could help him make sure his views, beliefs, wishes and aspirations are taken into account in the assessment, and with his agreement, arranges for an independent advocate with specialist brain injury training to support him. The independent advocate meets Stephen but also talks to his mother to get a true picture of Stephen’s current needs and wishes and to ascertain the differences between how Stephen is now and prior to acquiring his brain injury. The social worker carries out the needs assessment with Stephen who is supported by his independent advocate, and with Stephen’s approval, input from his mother.

Case Study: Lynette, who has learning disabilities

Lynette, who has learning disabilities, lives in a care home. A support worker contacted the local authority because another resident, Fred, has come into Lynette’s room late at night shouting on several occasions and most recently was seen pushing her. A safeguarding enquiry is started and the local authority appoint an independent advocate to support Lynette as they are concerned that she cannot express herself easily. When interviewed by the social worker Lynette cannot describe what happened. The social worker and advocate agree that the advocate will help Lynette to communicate how she feels.

The advocate spends time with Lynette. She explains what is happening and communicates with Lynette about different people that she lives with, including using photos, finding out more about her feelings. Lynette appears to be generally happy around the house and when going out, but is very distressed when she sees Fred in person, or even when she sees a picture of him. The advocate makes clear to the Local Authority what Lynette has communicated.

The local authority finds that whilst there is no doubt that Fred did what was reported, he may have done so as a result of his own confusion and distress. They agree a proposal from the registered manager of the care home that alarms will be put on Fred’s door and staffing numbers increased to prevent a recurrence. The local authority agrees to review the situation after some weeks during which time the advocate stays in contact with Lynette in order to understand the impact of this decision on Lynette. The advocate finds that Lynette remains distressed by Fred’s presence. She is concerned that the measures in place are not sufficient and writes this in a report to the local authority detailing what Lynette has communicated about where she lives and about Fred. The local authority agrees to look at what further action may be needed which might include considering whether Lynette and Fred should continue to share accommodation.

The main aspect of wellbeing promoted is protection from abuse and neglect, but also personal dignity and emotional wellbeing. The local authority has also demonstrated its regard for Lynette’s views, wishes, feelings and beliefs.

Case study: Janice, who cares for her mother

Janice is 43 and cares for her mother Sheena who is 72 who has advanced Parkinson’s and increasing cognitive and communication difficulties. Janice cares for her mother in excess of 40 hours per week. Janice gave up work to care for her mother 5 years ago, and using her direct payment Sheena pays her daughter for 8 hours per week for care and support, including helping her with personal care, cooking meals and grocery shopping. Sheena preferred this to paying someone else – she prefers not to have strangers in the house and finds that others often do not understand her needs. As Janice is caring for her mother for many more hours than this, Janice has received a carers assessment and receives her own carers personal budget which she uses for breaks such as her weekly aerobics class which she finds helps her keep in touch with her friends, stay healthy, and deal with stress.

There is no-one else available to act as an appropriate individual to support Sheena in decision making. Both Sheena and Janice would be happy for Janice to take on this role. However, as Janice received a payment, she would not be regarded as an appropriate individual, though the guidance states that good practice should ensure Janice’s views are sought as Sheena has made clear that she wishes this to happen.

Case study: Jacinta, who has moderate learning disabilities

Jacinta is 26 and lives with her mother and father. She has 2 siblings aged 28 and 23 who have left the family home. Jacinta would also like to move to living more independently. Jacinta has moderate learning disabilities and finds it hard to retain information. Jacinta’s parents are very worried that she won’t be able to cope living in her own home and are against her doing so. In these circumstances Jacinta’s parents would not be ‘an appropriate person’ who could effectively represent and support her involvement.

Case study: Brian, who has advanced dementia

Brian is 84 and has advancing dementia. He lives alone in the house he owns. Brian has very limited mobility, has frequent falls and has difficulty in remembering to take medication and to eat. He has periods when he is confused and weighing up the longer term advantages and disadvantages of this care and support options, but has been judged to retain ‘capacity’ Brian says he feels very lonely. Social services are already providing some domiciliary care for which Brian is charged. The local authority is reviewing Brian’s care plan. Brian’s daughter and son in law who have had little contact with Brian over the past few years and will inherit the house are adamant that he can cope at home and does not need to go into a care home. In these circumstances, in addition to a lack of recent contact, there could be a conflict of interests and Brian’s relatives would not be ‘an appropriate person’.

Case study: Kate, who has profound and multiple learning disabilities

Kate has profound and multiple learning disabilities. She doesn’t use formal communication such as words or signs. She communicates using body language and facial expressions. In her assessment, Kate’s independent advocate supports her to show some film of her visiting a local market, enjoying the colours and sounds around her. In this way, Kate is able to show the assessor some of the things that are important to her.

Case Study: Lucille

Case study 1.

Lucille develops a need for a care home placement. She lives alone and is the sole owner of her home. Her home is valued at £165,000, and she has £15,000 in savings. Lucille meets the criteria governing eligibility for a deferred payment.

Case study 2

Lucille’s son Buster has been providing informal care and support to her, and has heard of the deferred payments scheme. When Lucille decides she may benefit from a care home placement, her son suggests they approach her local authority together for information and advice about deferred payment agreements.

Her local authority provides them both with a printed information sheet setting out further details on the authority’s deferred payment scheme, and also provides them with contact details of some national and local services who provide financial information and advice

Lucille is interested in renting her property whilst residing in a care home. The local authority has an existing housing advice service, so signposts Lucille to them for further advice on lettings. The local authority’s standard information sheet also includes information on how her rental income may be used to pay for her care and support.

Case study 3

Lucille decides to secure her deferred payment agreement with her house, which is worth £165,000. The amount of equity available will be the value of the property minus 10%, minus a further £14,250 (the lower capital limit).

£165,000 – £16,500 – £14,250 = £134,250

Therefore, her ‘equity limit’ for the total amount she could defer would consequently be £134,250, which would leave £30,750 in equity in her home.

Case study 4

Lucille identifies a care home placement that meets her care and support needs, costing £540 per week. She has an income provided by her pension of £230 per week. Lucille decides not to rent her home as she intends to sell it within the year.

Based on this provisional estimate of her care costs, Lucille would contribute £86 (230 –144) per week from her income, and her weekly deferral would be £454.

Case study 5

Lucille discusses her care home fees with the local authority. Based on the equity available in her home (£134,250, as set out in Case study 3 above), Lucille could afford her weekly deferral of £454 for around 5 years. Given an average length of stay in a care home care of 19.7 months (source: BUPA 2010, cited in Laing and Buisson 2012/13), the local authority deems her projected care costs to be sustainable.

Lucille enquires as to the cost of a room with a garden view. This would increase her weekly deferral to £525 which she could afford for around four and a half years. The local authority deems this to be sustainable, so agrees to Lucille’s requested top-up.

Case study 6:

For illustrative purposes, we have used an interest rate of 3.5%. After 6 months, Lucille receives her first statement. It confirms she has deferred a total of £13,900, including £110 in interest and £100 in administration fees.

At this point, the local authority revalues her property, and finds its value has increased to £170,000. Based on the amount deferred and her care costs, her equity would afford her just over 4 and a half more years’ care at this price.

Case study: Using discretionary powers to meet needs

Mrs Pascal, who is frail and elderly, was admitted to hospital after a fall. The hospital has established that Mrs Pascal currently has no care and support plan in place and made contact with the local authority to arrange a needs assessment. The local authority assesses that she has eligible needs which will be best met in a care home setting.

The local authority undertakes a financial assessment which finds that Mrs Pascal’s finances are above the limit for financial support from the local authority. The authority provides her with information and advice about her options. Mrs Pascal expresses extreme nervousness about seeking a placement on her own as she has struggled with managing her personal finances in recent times and does not have any family who are able to support her.

After a consultation, both Mrs Pascal and her local authority agree that support with arranging and managing a care placement would be beneficial for her wellbeing and would adequately meet her eligible needs. The authority arranges for Mrs Pascal to meet a trusted brokerage organisation which discusses her needs and arranges a contract with a care home on behalf of Mrs Pascal that she is very happy with.

Case Study: Miss S, who has fluctuating needs

Miss S has Multiple Sclerosis and requires a frame or wheelchair for mobility. Miss S suffers badly with fatigue, but for the majority of the time she feels able to cope with daily life with a small amount of care and support. However, during relapses she has been unable to sit up, walk or transfer, has lost the use of an arm or lost her vision completely. This can last for a few weeks, and happens 2 or 3 times a year; requiring 24 hour support for all daily activities.

In the past, Miss S was hospitalised during relapses as she was unable to cope at home. However, for the past 3 years, she has received a care and support package that include direct payments which allows her to save up one month’s worth of 24 hour care for when she needs it, and this is detailed in the care and support plan.

Miss S can now instantly access the extra support she needs without reassessment and has reassurance that she will be able to put plans in place to cope with any fluctuating needs. She has not been hospitalised since.

Example: Costs of direct payments 1

Andrew has chosen to meet his needs by receiving care and support from a PA. The local authority has a block contract with an agency which has been providing support to Andrew twice per week. Andrew would now like more flexibility in the times at which he receives support in order to better meet his needs by allowing him to undertake other activities and consider employment.

He therefore requests a direct payment so that he can make his own arrangements with another agency, which is happy to arrange a much more flexible and personalised service, providing Andrew with the same care worker on each occasion, and at a time that works best for him.

The cost to the local authority of the block contracted services is £13.50 per hour. However, the more flexible support costs £18 per hour (inclusive of other employment costs). The local authority therefore increases Andrew’s direct payment from £67.50 to £90 per week to allow him to continue to receive the care he requires. The solution through a direct payment delivers better outcomes for Andrew and therefore the additional cost is reasonable and seen as value for money as it may delay future needs developing.

The local authority also agrees it is more efficient for them to allow Andrew to arrange and commission the hours he wants to receive support and handle the invoicing himself.

Example: Costs of direct payments 2

Following George’s assessment of needs, the local authority work out an indicative personal budget of £135 per week, based on their block contract rate of £13.50 per hour as an indication of the potential costs to meet his needs.

During care planning, George states that he has a neighbour that has recently trained to become a personal assistant, and George indicates a preference to use a direct payment to employ the neighbour instead of an arranged service.

The local authority is satisfied that George will be able to manage the direct payment, and that he understands his responsibilities as an employer. George wants to pay the PA above the living wage and has provisionally agreed a hourly rate of £9 per hour. The local authority agrees to this as George agrees that it will meet his needs and outcomes. The final personal budget is adjusted to £110 per week which factors in the new hourly rate, plus an additional allowance for employment responsibilities (PAYE, NI, insurance etc.)

Examples: Using Individual Service Funds

Sally really enjoys dancing and night clubs and she needs support for this. Sally’s ISF arrangement with her provider has given her the flexibility to employ staff that also like to do this, and they are paid time and a half after 11:00pm. The ISF arrangement also allows Sally to convert ‘standard hours’ into ‘enhanced hours’, for example, 6 standard hours equals 4 enhanced hours. Sally can plan late nights out knowing what it ‘costs’ from her allocation of 24 standard hours support, which is calculated from her personal budget.

Brian’s ISF arrangement with his provider allows him to save up and then convert the hours of his support into money to purchase personal trainer time at a local gym. In addition to promoting wellbeing in the areas of emotional and social wellbeing and personal relationships, these arrangements also demonstrate the local authority’s regard for the importance of beginning with the assumption that an individual is best-placed to judge their own wellbeing.

Examples: Flexible use of a carer’s personal budget

Conor has been caring for his wife, who is in a wheelchair with ME and arthritis, for the last 9 years. He does all the cooking, driving and general household duties for their household. Conor received a personal budget which he requested in the form of a direct payment from his local authority for a laptop to enable him to be in more regular contact through Skype with family in the US. This now enables Conor to stay connected with family he cannot afford to fly and see. This family support helps Connor with his ongoing caring role.

Divya has 4 young children and provides care for her father who is nearing the end of his life. Her father receives a direct payment, which he used to pay a family member for a period of time to give his daughter a break from her caring role. Divya received a carers’ direct payment, which she uses for her children to attend summer play schemes so that she get some free time to meet with friends and socialise when the family member providers care to her father. This gives Divya regular breaks from caring which are important to the family unit.

Case Study: Making direct payments support accessible

Abdul is a deafblind man; to communicate he prefers to use Braille, Deafblind Manual and email. He directly employs several staff through direct payments. He receives payroll support from his local direct payments support service. Abdul suggested ways to make direct payments management accessible to him. He communicates with the support service mainly via email but they also use Typetalk.

At the end of the month, Abdul emails the support service with details of the hours that his staff have worked. The support service work out any deductions from pay (such as National Insurance and Income Tax) and email him to tell him how much he should pay the staff via cheque. They then send him pay slips to be given to staff. The envelope that the payslips are sent in has 2 staples in the corner so that he knows who the letter is from. The payslips themselves are labelled in Braille so that he knows which staff to give them to.

Each quarter, the support service tells him how much he needs to pay on behalf of his employees in National Insurance and Income Tax. The service also fills in quarterly Inland Revenue paperwork. At the end of the year, the support service sends relevant information to the council, so that they are aware of how the direct payments are being spent.

Abdul has taken on only some of the responsibilities of employing people; he has delegated some tasks to the support service. Control still remains with Abdul and confidentiality is maintained by using accessible labelling. In terms of the wellbeing principle, the local authority has promoted Abdul’s control over his day-to-day life.

Example: Reduced monitoring

Gina has a stable condition and has been successfully managing her direct payment for over 2 years. The local authority therefore decides to reduce monitoring to the lowest level due to the low perceived risk (while still complying with the required review in the Act and Regulations). Gina is now considered to have the skills and experience to manage on her own unless the local authority request otherwise or information suggested otherwise comes to the attention of the local authority.

Example: Direct payment to pay a family member for administration support

David has been using direct payments to meet his needs for some time, and has used private agencies to provide payroll and administration support, funded by a one-off annual payment as part of his personal budget allocation. David’s wife, Gill provides care for him and is increasingly becoming more hands-on in arranging multiple PAs to visit and other administrative tasks as David’s care needs have begun to fluctuate.

They jointly approach the local authority to request that Gill undertake the administration support instead of the agency as they want to take complete control of the payment and care arrangements so that they can best meet David’s fluctuating needs and ensure that appropriate care is organized.

The local authority considers that Gill would be able to manage this aspect of the payment, and jointly revises the care plan to detail the aspects of the payment, and what services Gill will undertake to the agreement of all concerned. The personal budget is also revised accordingly.

The family now has complete control of the payment, Gill is reimbursed for her time in supporting David with his direct payment and the local authority is able to make a saving in the one-off support allocation as there are no provider overheads to pay. In promoting David’s wellbeing, the local authority has demonstrated regard for the balance between promoting an individual’s wellbeing and that of people who are involved in caring for them. It has given Gill increased control in a way that David is comfortable with and supports.

Example: Direct payment paid to a family member where necessary

James has severe learning difficulties as well as various physical disabilities. He has serious trust issues and a unique way of communicating that only his family, through years of care as a child, can understand. The local authority agrees that using a direct payment to pay for care from his parents is necessary as it is the best way to meet James’s needs and outcomes.

Example: Direct payments for short-term residential care

Mrs. H has one week in a care home every 6 weeks. Because each week in a care home is more than 4 weeks a part, they are not added together. The cumulative total is only one week and the 4-week limit is never reached.

Peter has 3 weeks in a care home, 2 weeks at home and then another week in a care home. The 2 episodes of time in a care home are less than 4 weeks apart and so they are added together making 4 weeks in total. Peter cannot use his direct payments to purchase any more care home services within a 12-month period.

Example: Using a direct payment whilst in hospital

Peter is deafblind and is required to stay in hospital for an operation. Whilst the hospital pays for an interpreter for the medical interventions, Peter needs additional support to be able to move around the ward, and to communicate informally with staff and his family. The local authority and the NHS Trust agree that Peter’s communicator guide continues to support him in hospital, and is paid for via the direct payment, as it was when Peter was at home. Personal and medical care is provided by NHS staff but Peter’s communicator guide is on hand to provide specialist communication and guiding support to make his hospital stay is as comfortable as possible.

Example: Local authority provided service

Graham has a direct payment for the full amount of his personal budget allowance. He decides to use a local authority run day service on an infrequent basis and requests to pay for it with his direct payment so that he retains flexibility about when he attends. The local authority service is able to agree to this request and has systems already in place to take payments as self-funders often use the service. The authority advise Graham that if he wishes to use the day service on a frequent basis (i.e. once a week) it would be better to provide the service to him direct, and to reduce the direct payment amount accordingly.

Review of Care and Support Plans

Example: accepting a renewal request.

A local authority receives an email from a relative of an older person receiving care and support at home. The email provides details that the older person’s condition is deteriorating and supplies evidence of recent visits to the GP. The local authority therefore decides to review their care and support plan to ensure that it continues to meet their needs.

Example: Declining a renewal request

A local authority receives a phone call from Mr X. He is angry as he feels that he has needs that have not been identified in his care plan and requests a review of the plan. The authority has on a separate recent occasion reviewed his plan, when it came to the conclusion that no revision was necessary and informed Mr X of the decision and the reasons for it. Therefore, the local authority declines the request in this case and provides a written explanation to Mr X, informing him of an anticipated date of when it will be formally reviewing the plan together with information on its complaints procedure.

Case study: Two brothers with mild learning disabilities