Now Available on Whatsapp:

+1 (888) 687-4420

Online 24/7

- College Essay

- Argumentative Essay

- Expository Essay

- Narrative Essay

- Descriptive Essay

- Scholarship Essay

- Admission Essay

- Reflective Essay

- Nursing Essay

- Economics Essay

Assignments

- Term Papers

- Research Papers

- Case Studies

- Dissertation

- Presentation

- Editing Help

- Cheap Essay Writing

- How to Order

Persuasive Essay Guide

Persuasive Essay About Covid19

How to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid19 | Examples & Tips

14 min read

People also read

A Comprehensive Guide to Writing an Effective Persuasive Essay

A Catalogue of 300 Best Persuasive Essay Topics for Students

Persuasive Essay Outline - A Complete Guide

30+ Persuasive Essay Examples To Get You Started

Read Excellent Examples of Persuasive Essay About Gun Control

How To Write A Persuasive Essay On Abortion

Learn to Write a Persuasive Essay About Business With 5 Best Examples

Check Out 14 Persuasive Essays About Online Education Examples

Persuasive Essay About Smoking - Making a Powerful Argument with Examples

Are you looking to write a persuasive essay about the Covid-19 pandemic?

Writing a compelling and informative essay about this global crisis can be challenging. It requires researching the latest information, understanding the facts, and presenting your argument persuasively.

But don’t worry! with some guidance from experts, you’ll be able to write an effective and persuasive essay about Covid-19.

In this blog post, we’ll outline the basics of writing a persuasive essay . We’ll provide clear examples, helpful tips, and essential information for crafting your own persuasive piece on Covid-19.

Read on to get started on your essay.

- 1. Steps to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

- 2. Examples of Persuasive Essay About COVID-19

- 3. Examples of Persuasive Essay About COVID-19 Vaccine

- 4. Examples of Persuasive Essay About COVID-19 Integration

- 5. Examples of Argumentative Essay About Covid 19

- 6. Examples of Persuasive Speeches About Covid-19

- 7. Tips to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

- 8. Common Topics for a Persuasive Essay on COVID-19

Steps to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Here are the steps to help you write a persuasive essay on this topic, along with an example essay:

Step 1: Choose a Specific Thesis Statement

Your thesis statement should clearly state your position on a specific aspect of COVID-19. It should be debatable and clear. For example:

Step 2: Research and Gather Information

Collect reliable and up-to-date information from reputable sources to support your thesis statement. This may include statistics, expert opinions, and scientific studies. For instance:

- COVID-19 vaccination effectiveness data

- Information on vaccine mandates in different countries

- Expert statements from health organizations like the WHO or CDC

Step 3: Outline Your Essay

Create a clear and organized outline to structure your essay. A persuasive essay typically follows this structure:

- Introduction

- Background Information

- Body Paragraphs (with supporting evidence)

- Counterarguments (addressing opposing views)

Step 4: Write the Introduction

In the introduction, grab your reader's attention and present your thesis statement. For example:

Step 5: Provide Background Information

Offer context and background information to help your readers understand the issue better. For instance:

Step 6: Develop Body Paragraphs

Each body paragraph should present a single point or piece of evidence that supports your thesis statement. Use clear topic sentences , evidence, and analysis. Here's an example:

Step 7: Address Counterarguments

Acknowledge opposing viewpoints and refute them with strong counterarguments. This demonstrates that you've considered different perspectives. For example:

Step 8: Write the Conclusion

Summarize your main points and restate your thesis statement in the conclusion. End with a strong call to action or thought-provoking statement. For instance:

Step 9: Revise and Proofread

Edit your essay for clarity, coherence, grammar, and spelling errors. Ensure that your argument flows logically.

Step 10: Cite Your Sources

Include proper citations and a bibliography page to give credit to your sources.

Remember to adjust your approach and arguments based on your target audience and the specific angle you want to take in your persuasive essay about COVID-19.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About COVID-19

When writing a persuasive essay about the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s important to consider how you want to present your argument. To help you get started, here are some example essays for you to read:

Here is another example explaining How COVID-19 has changed our lives essay:

Let’s look at another sample essay:

Check out some more PDF examples below:

Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Pandemic

Sample Of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 In The Philippines - Example

If you're in search of a compelling persuasive essay on business, don't miss out on our “ persuasive essay about business ” blog!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About COVID-19 Vaccine

Covid19 vaccines are one of the ways to prevent the spread of COVID-19, but they have been a source of controversy. Different sides argue about the benefits or dangers of the new vaccines. Whatever your point of view is, writing a persuasive essay about it is a good way of organizing your thoughts and persuading others.

A persuasive essay about the COVID-19 vaccine could consider the benefits of getting vaccinated as well as the potential side effects.

Below are some examples of persuasive essays on getting vaccinated for Covid-19.

Covid19 Vaccine Persuasive Essay

Persuasive Essay on Covid Vaccines

Interested in thought-provoking discussions on abortion? Read our persuasive essay about abortion blog to eplore arguments!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About COVID-19 Integration

Covid19 has drastically changed the way people interact in schools, markets, and workplaces. In short, it has affected all aspects of life. However, people have started to learn to live with Covid19.

Writing a persuasive essay about it shouldn't be stressful. Read the sample essay below to get an idea for your own essay about Covid19 integration.

Persuasive Essay About Working From Home During Covid19

Searching for the topic of Online Education? Our persuasive essay about online education is a must-read.

Examples of Argumentative Essay About Covid 19

Covid-19 has been an ever-evolving issue, with new developments and discoveries being made on a daily basis.

Writing an argumentative essay about such an issue is both interesting and challenging. It allows you to evaluate different aspects of the pandemic, as well as consider potential solutions.

Here are some examples of argumentative essays on Covid19.

Argumentative Essay About Covid19 Sample

Argumentative Essay About Covid19 With Introduction Body and Conclusion

Looking for a persuasive take on the topic of smoking? You'll find it all related arguments in out Persuasive Essay About Smoking blog!

Examples of Persuasive Speeches About Covid-19

Do you need to prepare a speech about Covid19 and need examples? We have them for you!

Persuasive speeches about Covid-19 can provide the audience with valuable insights on how to best handle the pandemic. They can be used to advocate for specific changes in policies or simply raise awareness about the virus.

Check out some examples of persuasive speeches on Covid-19:

Persuasive Speech About Covid-19 Example

Persuasive Speech About Vaccine For Covid-19

You can also read persuasive essay examples on other topics to master your persuasive techniques!

Tips to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Writing a persuasive essay about COVID-19 requires a thoughtful approach to present your arguments effectively.

Here are some tips to help you craft a compelling persuasive essay on this topic:

- Choose a Specific Angle: Narrow your focus to a specific aspect of COVID-19, like vaccination or public health measures.

- Provide Credible Sources: Support your arguments with reliable sources like scientific studies and government reports.

- Use Persuasive Language: Employ ethos, pathos, and logos , and use vivid examples to make your points relatable.

- Organize Your Essay: Create a solid persuasive essay outline and ensure a logical flow, with each paragraph focusing on a single point.

- Emphasize Benefits: Highlight how your suggestions can improve public health, safety, or well-being.

- Use Visuals: Incorporate graphs, charts, and statistics to reinforce your arguments.

- Call to Action: End your essay conclusion with a strong call to action, encouraging readers to take a specific step.

- Revise and Edit: Proofread for grammar, spelling, and clarity, ensuring smooth writing flow.

- Seek Feedback: Have someone else review your essay for valuable insights and improvements.

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Common Topics for a Persuasive Essay on COVID-19

Here are some persuasive essay topics on COVID-19:

- The Importance of Vaccination Mandates for COVID-19 Control

- Balancing Public Health and Personal Freedom During a Pandemic

- The Economic Impact of Lockdowns vs. Public Health Benefits

- The Role of Misinformation in Fueling Vaccine Hesitancy

- Remote Learning vs. In-Person Education: What's Best for Students?

- The Ethics of Vaccine Distribution: Prioritizing Vulnerable Populations

- The Mental Health Crisis Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic

- The Long-Term Effects of COVID-19 on Healthcare Systems

- Global Cooperation vs. Vaccine Nationalism in Fighting the Pandemic

- The Future of Telemedicine: Expanding Healthcare Access Post-COVID-19

In search of more inspiring topics for your next persuasive essay? Our persuasive essay topics blog has plenty of ideas!

To sum it up,

You’ve explored great sample essays and picked up some useful tips. You now have the tools you need to write a persuasive essay about Covid-19. So don’t let doubts hold you back—start writing!

If you’re feeling stuck or need a bit of extra help, don’t worry! MyPerfectWords.com offers a professional persuasive essay writing service that can assist you. Our experienced essay writers are ready to help you craft a well-structured, insightful paper on Covid-19.

Just place your “ do my essay for me ” request today, and let us take care of the rest!

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a good title for a covid-19 essay.

A good title for a COVID-19 essay should be clear, engaging, and reflective of the essay's content. Examples include:

- "The Impact of COVID-19 on Global Health"

- "How COVID-19 Has Transformed Our Daily Lives"

- "COVID-19: Lessons Learned and Future Implications"

How do I write an informative essay about COVID-19?

To write an informative essay about COVID-19, follow these steps:

- Choose a specific focus: Select a particular aspect of COVID-19, such as its transmission, symptoms, or vaccines.

- Research thoroughly: Gather information from credible sources like scientific journals and official health organizations.

- Organize your content: Structure your essay with an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

- Present facts clearly: Use clear, concise language to convey information accurately.

- Include visuals: Use charts or graphs to illustrate data and make your essay more engaging.

How do I write an expository essay about COVID-19?

To write an expository essay about COVID-19, follow these steps:

- Select a clear topic: Focus on a specific question or issue related to COVID-19.

- Conduct thorough research: Use reliable sources to gather information.

- Create an outline: Organize your essay with an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

- Explain the topic: Use facts and examples to explain the chosen aspect of COVID-19 in detail.

- Maintain objectivity: Present information in a neutral and unbiased manner.

- Edit and revise: Proofread your essay for clarity, coherence, and accuracy.

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Caleb S. has been providing writing services for over five years and has a Masters degree from Oxford University. He is an expert in his craft and takes great pride in helping students achieve their academic goals. Caleb is a dedicated professional who always puts his clients first.

Struggling With Your Paper?

Get a custom paper written at

With a FREE Turnitin report, and a 100% money-back guarantee

LIMITED TIME ONLY!

Keep reading

OFFER EXPIRES SOON!

How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2025 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

How to make a college list.

Cole Claybourn Nov. 6, 2024

Weighing LSAT Test Prep Options

Gabriel Kuris Nov. 4, 2024

Data Privacy Tips for College Students

Cole Claybourn Nov. 4, 2024

Preparing for Your First Job Post-Grad

Sarah Wood Oct. 31, 2024

5 Ways to Decrease Medical School Costs

Anayat Durrani Oct. 31, 2024

Graduate School with Student Loan Debt

A.R. Cabral Oct. 31, 2024

Colleges With Dog Mascots

Helen Lewis Oct. 31, 2024

15 Scholarships to Help Pay for College

Cole Claybourn and Alison Murtagh Oct. 29, 2024

Questions for Med School Social Events

Rachel Rizal Oct. 29, 2024

Schools for International Students

Sarah Wood Oct. 29, 2024

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 June 2021

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: an overview of systematic reviews

- Israel Júnior Borges do Nascimento 1 , 2 ,

- Dónal P. O’Mathúna 3 , 4 ,

- Thilo Caspar von Groote 5 ,

- Hebatullah Mohamed Abdulazeem 6 ,

- Ishanka Weerasekara 7 , 8 ,

- Ana Marusic 9 ,

- Livia Puljak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8467-6061 10 ,

- Vinicius Tassoni Civile 11 ,

- Irena Zakarija-Grkovic 9 ,

- Tina Poklepovic Pericic 9 ,

- Alvaro Nagib Atallah 11 ,

- Santino Filoso 12 ,

- Nicola Luigi Bragazzi 13 &

- Milena Soriano Marcolino 1

On behalf of the International Network of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (InterNetCOVID-19)

BMC Infectious Diseases volume 21 , Article number: 525 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

38 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

Navigating the rapidly growing body of scientific literature on the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is challenging, and ongoing critical appraisal of this output is essential. We aimed to summarize and critically appraise systematic reviews of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in humans that were available at the beginning of the pandemic.

Nine databases (Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, Web of Sciences, PDQ-Evidence, WHO’s Global Research, LILACS, and Epistemonikos) were searched from December 1, 2019, to March 24, 2020. Systematic reviews analyzing primary studies of COVID-19 were included. Two authors independently undertook screening, selection, extraction (data on clinical symptoms, prevalence, pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, diagnostic test assessment, laboratory, and radiological findings), and quality assessment (AMSTAR 2). A meta-analysis was performed of the prevalence of clinical outcomes.

Eighteen systematic reviews were included; one was empty (did not identify any relevant study). Using AMSTAR 2, confidence in the results of all 18 reviews was rated as “critically low”. Identified symptoms of COVID-19 were (range values of point estimates): fever (82–95%), cough with or without sputum (58–72%), dyspnea (26–59%), myalgia or muscle fatigue (29–51%), sore throat (10–13%), headache (8–12%) and gastrointestinal complaints (5–9%). Severe symptoms were more common in men. Elevated C-reactive protein and lactate dehydrogenase, and slightly elevated aspartate and alanine aminotransferase, were commonly described. Thrombocytopenia and elevated levels of procalcitonin and cardiac troponin I were associated with severe disease. A frequent finding on chest imaging was uni- or bilateral multilobar ground-glass opacity. A single review investigated the impact of medication (chloroquine) but found no verifiable clinical data. All-cause mortality ranged from 0.3 to 13.9%.

Conclusions

In this overview of systematic reviews, we analyzed evidence from the first 18 systematic reviews that were published after the emergence of COVID-19. However, confidence in the results of all reviews was “critically low”. Thus, systematic reviews that were published early on in the pandemic were of questionable usefulness. Even during public health emergencies, studies and systematic reviews should adhere to established methodological standards.

Peer Review reports

The spread of the “Severe Acute Respiratory Coronavirus 2” (SARS-CoV-2), the causal agent of COVID-19, was characterized as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2020 and has triggered an international public health emergency [ 1 ]. The numbers of confirmed cases and deaths due to COVID-19 are rapidly escalating, counting in millions [ 2 ], causing massive economic strain, and escalating healthcare and public health expenses [ 3 , 4 ].

The research community has responded by publishing an impressive number of scientific reports related to COVID-19. The world was alerted to the new disease at the beginning of 2020 [ 1 ], and by mid-March 2020, more than 2000 articles had been published on COVID-19 in scholarly journals, with 25% of them containing original data [ 5 ]. The living map of COVID-19 evidence, curated by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre), contained more than 40,000 records by February 2021 [ 6 ]. More than 100,000 records on PubMed were labeled as “SARS-CoV-2 literature, sequence, and clinical content” by February 2021 [ 7 ].

Due to publication speed, the research community has voiced concerns regarding the quality and reproducibility of evidence produced during the COVID-19 pandemic, warning of the potential damaging approach of “publish first, retract later” [ 8 ]. It appears that these concerns are not unfounded, as it has been reported that COVID-19 articles were overrepresented in the pool of retracted articles in 2020 [ 9 ]. These concerns about inadequate evidence are of major importance because they can lead to poor clinical practice and inappropriate policies [ 10 ].

Systematic reviews are a cornerstone of today’s evidence-informed decision-making. By synthesizing all relevant evidence regarding a particular topic, systematic reviews reflect the current scientific knowledge. Systematic reviews are considered to be at the highest level in the hierarchy of evidence and should be used to make informed decisions. However, with high numbers of systematic reviews of different scope and methodological quality being published, overviews of multiple systematic reviews that assess their methodological quality are essential [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. An overview of systematic reviews helps identify and organize the literature and highlights areas of priority in decision-making.

In this overview of systematic reviews, we aimed to summarize and critically appraise systematic reviews of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in humans that were available at the beginning of the pandemic.

Methodology

Research question.

This overview’s primary objective was to summarize and critically appraise systematic reviews that assessed any type of primary clinical data from patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Our research question was purposefully broad because we wanted to analyze as many systematic reviews as possible that were available early following the COVID-19 outbreak.

Study design

We conducted an overview of systematic reviews. The idea for this overview originated in a protocol for a systematic review submitted to PROSPERO (CRD42020170623), which indicated a plan to conduct an overview.

Overviews of systematic reviews use explicit and systematic methods for searching and identifying multiple systematic reviews addressing related research questions in the same field to extract and analyze evidence across important outcomes. Overviews of systematic reviews are in principle similar to systematic reviews of interventions, but the unit of analysis is a systematic review [ 14 , 15 , 16 ].

We used the overview methodology instead of other evidence synthesis methods to allow us to collate and appraise multiple systematic reviews on this topic, and to extract and analyze their results across relevant topics [ 17 ]. The overview and meta-analysis of systematic reviews allowed us to investigate the methodological quality of included studies, summarize results, and identify specific areas of available or limited evidence, thereby strengthening the current understanding of this novel disease and guiding future research [ 13 ].

A reporting guideline for overviews of reviews is currently under development, i.e., Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews (PRIOR) [ 18 ]. As the PRIOR checklist is still not published, this study was reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009 statement [ 19 ]. The methodology used in this review was adapted from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and also followed established methodological considerations for analyzing existing systematic reviews [ 14 ].

Approval of a research ethics committee was not necessary as the study analyzed only publicly available articles.

Eligibility criteria

Systematic reviews were included if they analyzed primary data from patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 as confirmed by RT-PCR or another pre-specified diagnostic technique. Eligible reviews covered all topics related to COVID-19 including, but not limited to, those that reported clinical symptoms, diagnostic methods, therapeutic interventions, laboratory findings, or radiological results. Both full manuscripts and abbreviated versions, such as letters, were eligible.

No restrictions were imposed on the design of the primary studies included within the systematic reviews, the last search date, whether the review included meta-analyses or language. Reviews related to SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses were eligible, but from those reviews, we analyzed only data related to SARS-CoV-2.

No consensus definition exists for a systematic review [ 20 ], and debates continue about the defining characteristics of a systematic review [ 21 ]. Cochrane’s guidance for overviews of reviews recommends setting pre-established criteria for making decisions around inclusion [ 14 ]. That is supported by a recent scoping review about guidance for overviews of systematic reviews [ 22 ].

Thus, for this study, we defined a systematic review as a research report which searched for primary research studies on a specific topic using an explicit search strategy, had a detailed description of the methods with explicit inclusion criteria provided, and provided a summary of the included studies either in narrative or quantitative format (such as a meta-analysis). Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews were considered eligible for inclusion, with or without meta-analysis, and regardless of the study design, language restriction and methodology of the included primary studies. To be eligible for inclusion, reviews had to be clearly analyzing data related to SARS-CoV-2 (associated or not with other viruses). We excluded narrative reviews without those characteristics as these are less likely to be replicable and are more prone to bias.

Scoping reviews and rapid reviews were eligible for inclusion in this overview if they met our pre-defined inclusion criteria noted above. We included reviews that addressed SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses if they reported separate data regarding SARS-CoV-2.

Information sources

Nine databases were searched for eligible records published between December 1, 2019, and March 24, 2020: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews via Cochrane Library, PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Web of Sciences, LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature), PDQ-Evidence, WHO’s Global Research on Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19), and Epistemonikos.

The comprehensive search strategy for each database is provided in Additional file 1 and was designed and conducted in collaboration with an information specialist. All retrieved records were primarily processed in EndNote, where duplicates were removed, and records were then imported into the Covidence platform [ 23 ]. In addition to database searches, we screened reference lists of reviews included after screening records retrieved via databases.

Study selection

All searches, screening of titles and abstracts, and record selection, were performed independently by two investigators using the Covidence platform [ 23 ]. Articles deemed potentially eligible were retrieved for full-text screening carried out independently by two investigators. Discrepancies at all stages were resolved by consensus. During the screening, records published in languages other than English were translated by a native/fluent speaker.

Data collection process

We custom designed a data extraction table for this study, which was piloted by two authors independently. Data extraction was performed independently by two authors. Conflicts were resolved by consensus or by consulting a third researcher.

We extracted the following data: article identification data (authors’ name and journal of publication), search period, number of databases searched, population or settings considered, main results and outcomes observed, and number of participants. From Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA), we extracted journal rank (quartile) and Journal Impact Factor (JIF).

We categorized the following as primary outcomes: all-cause mortality, need for and length of mechanical ventilation, length of hospitalization (in days), admission to intensive care unit (yes/no), and length of stay in the intensive care unit.

The following outcomes were categorized as exploratory: diagnostic methods used for detection of the virus, male to female ratio, clinical symptoms, pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, laboratory findings (full blood count, liver enzymes, C-reactive protein, d-dimer, albumin, lipid profile, serum electrolytes, blood vitamin levels, glucose levels, and any other important biomarkers), and radiological findings (using radiography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging or ultrasound).

We also collected data on reporting guidelines and requirements for the publication of systematic reviews and meta-analyses from journal websites where included reviews were published.

Quality assessment in individual reviews

Two researchers independently assessed the reviews’ quality using the “A MeaSurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews 2 (AMSTAR 2)”. We acknowledge that the AMSTAR 2 was created as “a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomized or non-randomized studies of healthcare interventions, or both” [ 24 ]. However, since AMSTAR 2 was designed for systematic reviews of intervention trials, and we included additional types of systematic reviews, we adjusted some AMSTAR 2 ratings and reported these in Additional file 2 .

Adherence to each item was rated as follows: yes, partial yes, no, or not applicable (such as when a meta-analysis was not conducted). The overall confidence in the results of the review is rated as “critically low”, “low”, “moderate” or “high”, according to the AMSTAR 2 guidance based on seven critical domains, which are items 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15 as defined by AMSTAR 2 authors [ 24 ]. We reported our adherence ratings for transparency of our decision with accompanying explanations, for each item, in each included review.

One of the included systematic reviews was conducted by some members of this author team [ 25 ]. This review was initially assessed independently by two authors who were not co-authors of that review to prevent the risk of bias in assessing this study.

Synthesis of results

For data synthesis, we prepared a table summarizing each systematic review. Graphs illustrating the mortality rate and clinical symptoms were created. We then prepared a narrative summary of the methods, findings, study strengths, and limitations.

For analysis of the prevalence of clinical outcomes, we extracted data on the number of events and the total number of patients to perform proportional meta-analysis using RStudio© software, with the “meta” package (version 4.9–6), using the “metaprop” function for reviews that did not perform a meta-analysis, excluding case studies because of the absence of variance. For reviews that did not perform a meta-analysis, we presented pooled results of proportions with their respective confidence intervals (95%) by the inverse variance method with a random-effects model, using the DerSimonian-Laird estimator for τ 2 . We adjusted data using Freeman-Tukey double arcosen transformation. Confidence intervals were calculated using the Clopper-Pearson method for individual studies. We created forest plots using the RStudio© software, with the “metafor” package (version 2.1–0) and “forest” function.

Managing overlapping systematic reviews

Some of the included systematic reviews that address the same or similar research questions may include the same primary studies in overviews. Including such overlapping reviews may introduce bias when outcome data from the same primary study are included in the analyses of an overview multiple times. Thus, in summaries of evidence, multiple-counting of the same outcome data will give data from some primary studies too much influence [ 14 ]. In this overview, we did not exclude overlapping systematic reviews because, according to Cochrane’s guidance, it may be appropriate to include all relevant reviews’ results if the purpose of the overview is to present and describe the current body of evidence on a topic [ 14 ]. To avoid any bias in summary estimates associated with overlapping reviews, we generated forest plots showing data from individual systematic reviews, but the results were not pooled because some primary studies were included in multiple reviews.

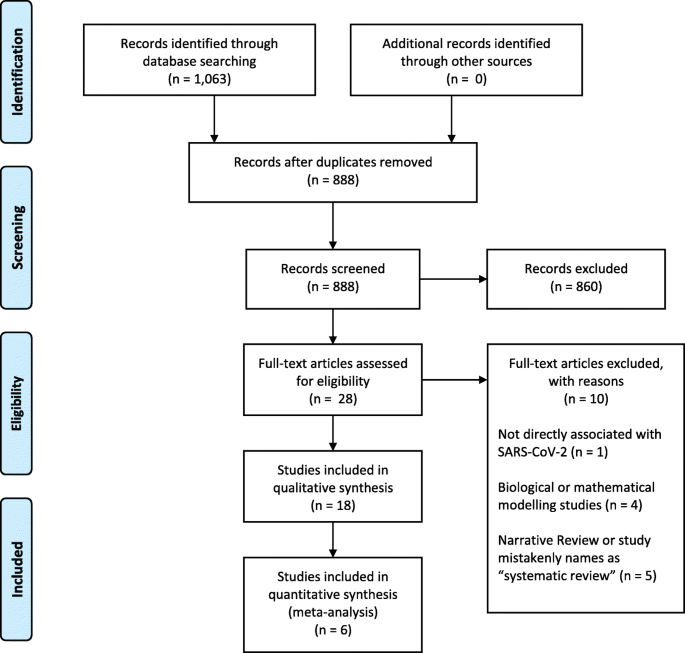

Our search retrieved 1063 publications, of which 175 were duplicates. Most publications were excluded after the title and abstract analysis ( n = 860). Among the 28 studies selected for full-text screening, 10 were excluded for the reasons described in Additional file 3 , and 18 were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1 ) [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ]. Reference list screening did not retrieve any additional systematic reviews.

PRISMA flow diagram

Characteristics of included reviews

Summary features of 18 systematic reviews are presented in Table 1 . They were published in 14 different journals. Only four of these journals had specific requirements for systematic reviews (with or without meta-analysis): European Journal of Internal Medicine, Journal of Clinical Medicine, Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Clinical Research in Cardiology . Two journals reported that they published only invited reviews ( Journal of Medical Virology and Clinica Chimica Acta ). Three systematic reviews in our study were published as letters; one was labeled as a scoping review and another as a rapid review (Table 2 ).

All reviews were published in English, in first quartile (Q1) journals, with JIF ranging from 1.692 to 6.062. One review was empty, meaning that its search did not identify any relevant studies; i.e., no primary studies were included [ 36 ]. The remaining 17 reviews included 269 unique studies; the majority ( N = 211; 78%) were included in only a single review included in our study (range: 1 to 12). Primary studies included in the reviews were published between December 2019 and March 18, 2020, and comprised case reports, case series, cohorts, and other observational studies. We found only one review that included randomized clinical trials [ 38 ]. In the included reviews, systematic literature searches were performed from 2019 (entire year) up to March 9, 2020. Ten systematic reviews included meta-analyses. The list of primary studies found in the included systematic reviews is shown in Additional file 4 , as well as the number of reviews in which each primary study was included.

Population and study designs

Most of the reviews analyzed data from patients with COVID-19 who developed pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), or any other correlated complication. One review aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of using surgical masks on preventing transmission of the virus [ 36 ], one review was focused on pediatric patients [ 34 ], and one review investigated COVID-19 in pregnant women [ 37 ]. Most reviews assessed clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, or radiological results.

Systematic review findings

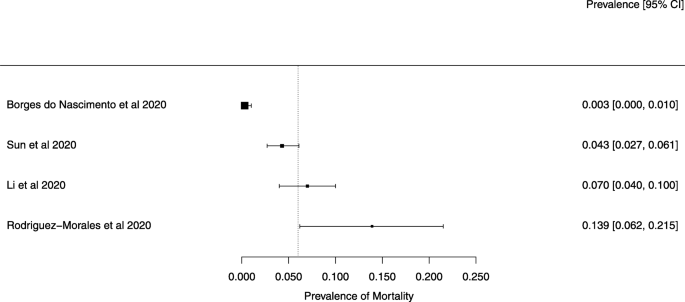

The summary of findings from individual reviews is shown in Table 2 . Overall, all-cause mortality ranged from 0.3 to 13.9% (Fig. 2 ).

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of mortality

Clinical symptoms

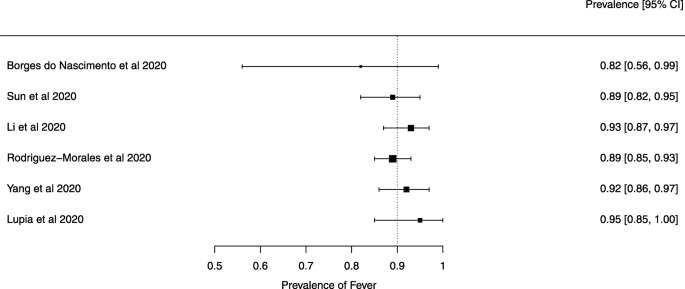

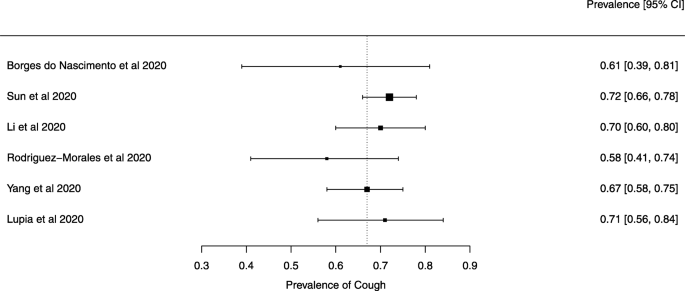

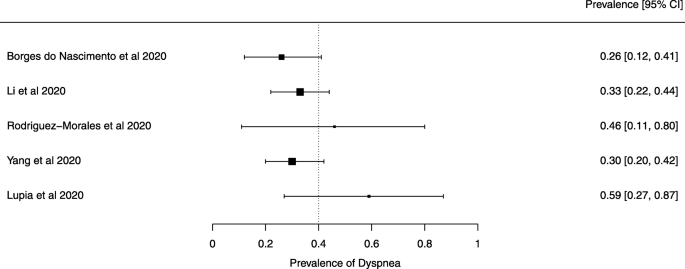

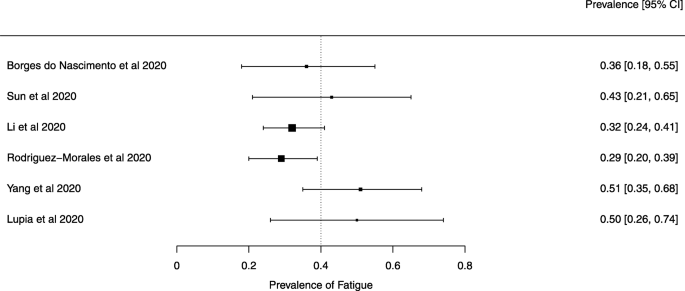

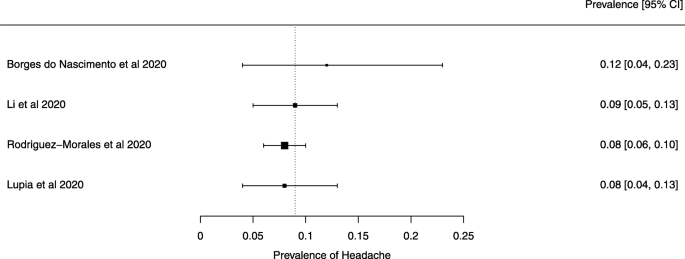

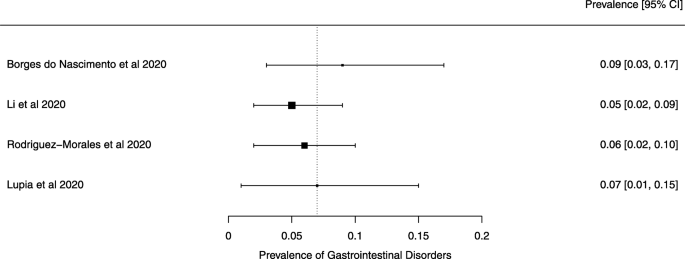

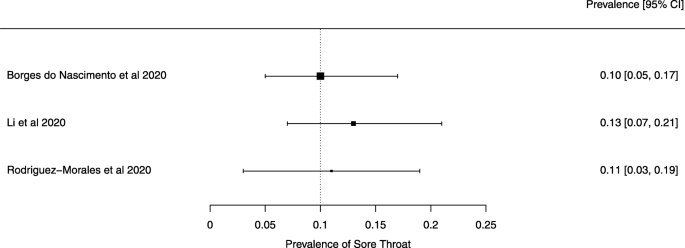

Seven reviews described the main clinical manifestations of COVID-19 [ 26 , 28 , 29 , 34 , 35 , 39 , 41 ]. Three of them provided only a narrative discussion of symptoms [ 26 , 34 , 35 ]. In the reviews that performed a statistical analysis of the incidence of different clinical symptoms, symptoms in patients with COVID-19 were (range values of point estimates): fever (82–95%), cough with or without sputum (58–72%), dyspnea (26–59%), myalgia or muscle fatigue (29–51%), sore throat (10–13%), headache (8–12%), gastrointestinal disorders, such as diarrhea, nausea or vomiting (5.0–9.0%), and others (including, in one study only: dizziness 12.1%) (Figs. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 and 9 ). Three reviews assessed cough with and without sputum together; only one review assessed sputum production itself (28.5%).

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of fever

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of cough

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of dyspnea

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of fatigue or myalgia

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of headache

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of gastrointestinal disorders

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of sore throat

Diagnostic aspects

Three reviews described methodologies, protocols, and tools used for establishing the diagnosis of COVID-19 [ 26 , 34 , 38 ]. The use of respiratory swabs (nasal or pharyngeal) or blood specimens to assess the presence of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid using RT-PCR assays was the most commonly used diagnostic method mentioned in the included studies. These diagnostic tests have been widely used, but their precise sensitivity and specificity remain unknown. One review included a Chinese study with clinical diagnosis with no confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection (patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 if they presented with at least two symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, together with laboratory and chest radiography abnormalities) [ 34 ].

Therapeutic possibilities

Pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions (supportive therapies) used in treating patients with COVID-19 were reported in five reviews [ 25 , 27 , 34 , 35 , 38 ]. Antivirals used empirically for COVID-19 treatment were reported in seven reviews [ 25 , 27 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 41 ]; most commonly used were protease inhibitors (lopinavir, ritonavir, darunavir), nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (tenofovir), nucleotide analogs (remdesivir, galidesivir, ganciclovir), and neuraminidase inhibitors (oseltamivir). Umifenovir, a membrane fusion inhibitor, was investigated in two studies [ 25 , 35 ]. Possible supportive interventions analyzed were different types of oxygen supplementation and breathing support (invasive or non-invasive ventilation) [ 25 ]. The use of antibiotics, both empirically and to treat secondary pneumonia, was reported in six studies [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 34 , 35 , 38 ]. One review specifically assessed evidence on the efficacy and safety of the anti-malaria drug chloroquine [ 27 ]. It identified 23 ongoing trials investigating the potential of chloroquine as a therapeutic option for COVID-19, but no verifiable clinical outcomes data. The use of mesenchymal stem cells, antifungals, and glucocorticoids were described in four reviews [ 25 , 34 , 35 , 38 ].

Laboratory and radiological findings

Of the 18 reviews included in this overview, eight analyzed laboratory parameters in patients with COVID-19 [ 25 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 39 ]; elevated C-reactive protein levels, associated with lymphocytopenia, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, as well as slightly elevated aspartate and alanine aminotransferase (AST, ALT) were commonly described in those eight reviews. Lippi et al. assessed cardiac troponin I (cTnI) [ 25 ], procalcitonin [ 32 ], and platelet count [ 33 ] in COVID-19 patients. Elevated levels of procalcitonin [ 32 ] and cTnI [ 30 ] were more likely to be associated with a severe disease course (requiring intensive care unit admission and intubation). Furthermore, thrombocytopenia was frequently observed in patients with complicated COVID-19 infections [ 33 ].

Chest imaging (chest radiography and/or computed tomography) features were assessed in six reviews, all of which described a frequent pattern of local or bilateral multilobar ground-glass opacity [ 25 , 34 , 35 , 39 , 40 , 41 ]. Those six reviews showed that septal thickening, bronchiectasis, pleural and cardiac effusions, halo signs, and pneumothorax were observed in patients suffering from COVID-19.

Quality of evidence in individual systematic reviews

Table 3 shows the detailed results of the quality assessment of 18 systematic reviews, including the assessment of individual items and summary assessment. A detailed explanation for each decision in each review is available in Additional file 5 .

Using AMSTAR 2 criteria, confidence in the results of all 18 reviews was rated as “critically low” (Table 3 ). Common methodological drawbacks were: omission of prospective protocol submission or publication; use of inappropriate search strategy: lack of independent and dual literature screening and data-extraction (or methodology unclear); absence of an explanation for heterogeneity among the studies included; lack of reasons for study exclusion (or rationale unclear).

Risk of bias assessment, based on a reported methodological tool, and quality of evidence appraisal, in line with the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) method, were reported only in one review [ 25 ]. Five reviews presented a table summarizing bias, using various risk of bias tools [ 25 , 29 , 39 , 40 , 41 ]. One review analyzed “study quality” [ 37 ]. One review mentioned the risk of bias assessment in the methodology but did not provide any related analysis [ 28 ].

This overview of systematic reviews analyzed the first 18 systematic reviews published after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, up to March 24, 2020, with primary studies involving more than 60,000 patients. Using AMSTAR-2, we judged that our confidence in all those reviews was “critically low”. Ten reviews included meta-analyses. The reviews presented data on clinical manifestations, laboratory and radiological findings, and interventions. We found no systematic reviews on the utility of diagnostic tests.

Symptoms were reported in seven reviews; most of the patients had a fever, cough, dyspnea, myalgia or muscle fatigue, and gastrointestinal disorders such as diarrhea, nausea, or vomiting. Olfactory dysfunction (anosmia or dysosmia) has been described in patients infected with COVID-19 [ 43 ]; however, this was not reported in any of the reviews included in this overview. During the SARS outbreak in 2002, there were reports of impairment of the sense of smell associated with the disease [ 44 , 45 ].

The reported mortality rates ranged from 0.3 to 14% in the included reviews. Mortality estimates are influenced by the transmissibility rate (basic reproduction number), availability of diagnostic tools, notification policies, asymptomatic presentations of the disease, resources for disease prevention and control, and treatment facilities; variability in the mortality rate fits the pattern of emerging infectious diseases [ 46 ]. Furthermore, the reported cases did not consider asymptomatic cases, mild cases where individuals have not sought medical treatment, and the fact that many countries had limited access to diagnostic tests or have implemented testing policies later than the others. Considering the lack of reviews assessing diagnostic testing (sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of RT-PCT or immunoglobulin tests), and the preponderance of studies that assessed only symptomatic individuals, considerable imprecision around the calculated mortality rates existed in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Few reviews included treatment data. Those reviews described studies considered to be at a very low level of evidence: usually small, retrospective studies with very heterogeneous populations. Seven reviews analyzed laboratory parameters; those reviews could have been useful for clinicians who attend patients suspected of COVID-19 in emergency services worldwide, such as assessing which patients need to be reassessed more frequently.

All systematic reviews scored poorly on the AMSTAR 2 critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews. Most of the original studies included in the reviews were case series and case reports, impacting the quality of evidence. Such evidence has major implications for clinical practice and the use of these reviews in evidence-based practice and policy. Clinicians, patients, and policymakers can only have the highest confidence in systematic review findings if high-quality systematic review methodologies are employed. The urgent need for information during a pandemic does not justify poor quality reporting.

We acknowledge that there are numerous challenges associated with analyzing COVID-19 data during a pandemic [ 47 ]. High-quality evidence syntheses are needed for decision-making, but each type of evidence syntheses is associated with its inherent challenges.

The creation of classic systematic reviews requires considerable time and effort; with massive research output, they quickly become outdated, and preparing updated versions also requires considerable time. A recent study showed that updates of non-Cochrane systematic reviews are published a median of 5 years after the publication of the previous version [ 48 ].

Authors may register a review and then abandon it [ 49 ], but the existence of a public record that is not updated may lead other authors to believe that the review is still ongoing. A quarter of Cochrane review protocols remains unpublished as completed systematic reviews 8 years after protocol publication [ 50 ].

Rapid reviews can be used to summarize the evidence, but they involve methodological sacrifices and simplifications to produce information promptly, with inconsistent methodological approaches [ 51 ]. However, rapid reviews are justified in times of public health emergencies, and even Cochrane has resorted to publishing rapid reviews in response to the COVID-19 crisis [ 52 ]. Rapid reviews were eligible for inclusion in this overview, but only one of the 18 reviews included in this study was labeled as a rapid review.

Ideally, COVID-19 evidence would be continually summarized in a series of high-quality living systematic reviews, types of evidence synthesis defined as “ a systematic review which is continually updated, incorporating relevant new evidence as it becomes available ” [ 53 ]. However, conducting living systematic reviews requires considerable resources, calling into question the sustainability of such evidence synthesis over long periods [ 54 ].

Research reports about COVID-19 will contribute to research waste if they are poorly designed, poorly reported, or simply not necessary. In principle, systematic reviews should help reduce research waste as they usually provide recommendations for further research that is needed or may advise that sufficient evidence exists on a particular topic [ 55 ]. However, systematic reviews can also contribute to growing research waste when they are not needed, or poorly conducted and reported. Our present study clearly shows that most of the systematic reviews that were published early on in the COVID-19 pandemic could be categorized as research waste, as our confidence in their results is critically low.

Our study has some limitations. One is that for AMSTAR 2 assessment we relied on information available in publications; we did not attempt to contact study authors for clarifications or additional data. In three reviews, the methodological quality appraisal was challenging because they were published as letters, or labeled as rapid communications. As a result, various details about their review process were not included, leading to AMSTAR 2 questions being answered as “not reported”, resulting in low confidence scores. Full manuscripts might have provided additional information that could have led to higher confidence in the results. In other words, low scores could reflect incomplete reporting, not necessarily low-quality review methods. To make their review available more rapidly and more concisely, the authors may have omitted methodological details. A general issue during a crisis is that speed and completeness must be balanced. However, maintaining high standards requires proper resourcing and commitment to ensure that the users of systematic reviews can have high confidence in the results.

Furthermore, we used adjusted AMSTAR 2 scoring, as the tool was designed for critical appraisal of reviews of interventions. Some reviews may have received lower scores than actually warranted in spite of these adjustments.

Another limitation of our study may be the inclusion of multiple overlapping reviews, as some included reviews included the same primary studies. According to the Cochrane Handbook, including overlapping reviews may be appropriate when the review’s aim is “ to present and describe the current body of systematic review evidence on a topic ” [ 12 ], which was our aim. To avoid bias with summarizing evidence from overlapping reviews, we presented the forest plots without summary estimates. The forest plots serve to inform readers about the effect sizes for outcomes that were reported in each review.

Several authors from this study have contributed to one of the reviews identified [ 25 ]. To reduce the risk of any bias, two authors who did not co-author the review in question initially assessed its quality and limitations.

Finally, we note that the systematic reviews included in our overview may have had issues that our analysis did not identify because we did not analyze their primary studies to verify the accuracy of the data and information they presented. We give two examples to substantiate this possibility. Lovato et al. wrote a commentary on the review of Sun et al. [ 41 ], in which they criticized the authors’ conclusion that sore throat is rare in COVID-19 patients [ 56 ]. Lovato et al. highlighted that multiple studies included in Sun et al. did not accurately describe participants’ clinical presentations, warning that only three studies clearly reported data on sore throat [ 56 ].

In another example, Leung [ 57 ] warned about the review of Li, L.Q. et al. [ 29 ]: “ it is possible that this statistic was computed using overlapped samples, therefore some patients were double counted ”. Li et al. responded to Leung that it is uncertain whether the data overlapped, as they used data from published articles and did not have access to the original data; they also reported that they requested original data and that they plan to re-do their analyses once they receive them; they also urged readers to treat the data with caution [ 58 ]. This points to the evolving nature of evidence during a crisis.

Our study’s strength is that this overview adds to the current knowledge by providing a comprehensive summary of all the evidence synthesis about COVID-19 available early after the onset of the pandemic. This overview followed strict methodological criteria, including a comprehensive and sensitive search strategy and a standard tool for methodological appraisal of systematic reviews.

In conclusion, in this overview of systematic reviews, we analyzed evidence from the first 18 systematic reviews that were published after the emergence of COVID-19. However, confidence in the results of all the reviews was “critically low”. Thus, systematic reviews that were published early on in the pandemic could be categorized as research waste. Even during public health emergencies, studies and systematic reviews should adhere to established methodological standards to provide patients, clinicians, and decision-makers trustworthy evidence.

Availability of data and materials

All data collected and analyzed within this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

World Health Organization. Timeline - COVID-19: Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-06-2020-covidtimeline . Accessed 1 June 2021.

COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). Available at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html . Accessed 1 June 2021.

Anzai A, Kobayashi T, Linton NM, Kinoshita R, Hayashi K, Suzuki A, et al. Assessing the Impact of Reduced Travel on Exportation Dynamics of Novel Coronavirus Infection (COVID-19). J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):601.

Chinazzi M, Davis JT, Ajelli M, Gioannini C, Litvinova M, Merler S, et al. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science. 2020;368(6489):395–400. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba9757 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fidahic M, Nujic D, Runjic R, Civljak M, Markotic F, Lovric Makaric Z, et al. Research methodology and characteristics of journal articles with original data, preprint articles and registered clinical trial protocols about COVID-19. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20(1):161. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-020-01047-2 .

EPPI Centre . COVID-19: a living systematic map of the evidence. Available at: http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Projects/DepartmentofHealthandSocialCare/Publishedreviews/COVID-19Livingsystematicmapoftheevidence/tabid/3765/Default.aspx . Accessed 1 June 2021.

NCBI SARS-CoV-2 Resources. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sars-cov-2/ . Accessed 1 June 2021.

Gustot T. Quality and reproducibility during the COVID-19 pandemic. JHEP Rep. 2020;2(4):100141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100141 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kodvanj, I., et al., Publishing of COVID-19 Preprints in Peer-reviewed Journals, Preprinting Trends, Public Discussion and Quality Issues. Preprint article. bioRxiv 2020.11.23.394577; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.23.394577 .

Dobler CC. Poor quality research and clinical practice during COVID-19. Breathe (Sheff). 2020;16(2):200112. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.0112-2020 .

Article Google Scholar

Bastian H, Glasziou P, Chalmers I. Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLoS Med. 2010;7(9):e1000326. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000326 .

Lunny C, Brennan SE, McDonald S, McKenzie JE. Toward a comprehensive evidence map of overview of systematic review methods: paper 1-purpose, eligibility, search and data extraction. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):231. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0617-1 .

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Becker LA, Pieper D, Hartling L. Chapter V: Overviews of Reviews. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane. 2020. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane. 2020; Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Newton AS, Scott SD, Hartling L. The impact of different inclusion decisions on the comprehensiveness and complexity of overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0914-3 .

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Newton AS, Scott SD, Hartling L. A decision tool to help researchers make decisions about including systematic reviews in overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0768-8 .

Hunt H, Pollock A, Campbell P, Estcourt L, Brunton G. An introduction to overviews of reviews: planning a relevant research question and objective for an overview. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0695-8 .

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Pieper D, Tricco AC, Gates M, Gates A, et al. Preferred reporting items for overviews of reviews (PRIOR): a protocol for development of a reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):335. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1252-9 .

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Open Med. 2009;3(3):e123–30.

Krnic Martinic M, Pieper D, Glatt A, Puljak L. Definition of a systematic review used in overviews of systematic reviews, meta-epidemiological studies and textbooks. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):203. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0855-0 .

Puljak L. If there is only one author or only one database was searched, a study should not be called a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;91:4–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.08.002 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gates M, Gates A, Guitard S, Pollock M, Hartling L. Guidance for overviews of reviews continues to accumulate, but important challenges remain: a scoping review. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):254. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01509-0 .

Covidence - systematic review software. Available at: https://www.covidence.org/ . Accessed 1 June 2021.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008.

Borges do Nascimento IJ, et al. Novel Coronavirus Infection (COVID-19) in Humans: A Scoping Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):941.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Adhikari SP, Meng S, Wu YJ, Mao YP, Ye RX, Wang QZ, et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-020-00646-x .

Cortegiani A, Ingoglia G, Ippolito M, Giarratano A, Einav S. A systematic review on the efficacy and safety of chloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19. J Crit Care. 2020;57:279–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.03.005 .

Li B, Yang J, Zhao F, Zhi L, Wang X, Liu L, et al. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin Res Cardiol. 2020;109(5):531–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-020-01626-9 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Li LQ, Huang T, Wang YQ, Wang ZP, Liang Y, Huang TB, et al. COVID-19 patients’ clinical characteristics, discharge rate, and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):577–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25757 .

Lippi G, Lavie CJ, Sanchis-Gomar F. Cardiac troponin I in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): evidence from a meta-analysis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63(3):390–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2020.03.001 .

Lippi G, Henry BM. Active smoking is not associated with severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Eur J Intern Med. 2020;75:107–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2020.03.014 .

Lippi G, Plebani M. Procalcitonin in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;505:190–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.004 .

Lippi G, Plebani M, Henry BM. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;506:145–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022 .

Ludvigsson JF. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(6):1088–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15270 .

Lupia T, Scabini S, Mornese Pinna S, di Perri G, de Rosa FG, Corcione S. 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak: a new challenge. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;21:22–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2020.02.021 .

Marasinghe, K.M., A systematic review investigating the effectiveness of face mask use in limiting the spread of COVID-19 among medically not diagnosed individuals: shedding light on current recommendations provided to individuals not medically diagnosed with COVID-19. Research Square. Preprint article. doi : https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-16701/v1 . 2020 .

Mullins E, Evans D, Viner RM, O’Brien P, Morris E. Coronavirus in pregnancy and delivery: rapid review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;55(5):586–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.22014 .

Pang J, Wang MX, Ang IYH, Tan SHX, Lewis RF, Chen JIP, et al. Potential Rapid Diagnostics, Vaccine and Therapeutics for 2019 Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV): a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3):623.

Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, Villamizar-Peña R, Holguin-Rivera Y, Escalera-Antezana JP, et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;34:101623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101623 .

Salehi S, Abedi A, Balakrishnan S, Gholamrezanezhad A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review of imaging findings in 919 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;215(1):87–93. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.20.23034 .

Sun P, Qie S, Liu Z, Ren J, Li K, Xi J. Clinical characteristics of hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: a single arm meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):612–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25735 .

Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, Pu K, Chen Z, Guo Q, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:91–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017 .

Bassetti M, Vena A, Giacobbe DR. The novel Chinese coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infections: challenges for fighting the storm. Eur J Clin Investig. 2020;50(3):e13209. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.13209 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Hwang CS. Olfactory neuropathy in severe acute respiratory syndrome: report of a case. Acta Neurol Taiwanica. 2006;15(1):26–8.

Google Scholar

Suzuki M, Saito K, Min WP, Vladau C, Toida K, Itoh H, et al. Identification of viruses in patients with postviral olfactory dysfunction. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(2):272–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlg.0000249922.37381.1e .

Rajgor DD, Lee MH, Archuleta S, Bagdasarian N, Quek SC. The many estimates of the COVID-19 case fatality rate. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):776–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30244-9 .

Wolkewitz M, Puljak L. Methodological challenges of analysing COVID-19 data during the pandemic. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20(1):81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-020-00972-6 .

Rombey T, Lochner V, Puljak L, Könsgen N, Mathes T, Pieper D. Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of non-Cochrane updates of systematic reviews: a cross-sectional study. Res Synth Methods. 2020;11(3):471–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1409 .

Runjic E, Rombey T, Pieper D, Puljak L. Half of systematic reviews about pain registered in PROSPERO were not published and the majority had inaccurate status. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;116:114–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.08.010 .

Runjic E, Behmen D, Pieper D, Mathes T, Tricco AC, Moher D, et al. Following Cochrane review protocols to completion 10 years later: a retrospective cohort study and author survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;111:41–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.03.006 .

Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, Strifler L, Ghassemi M, Ivory J, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):224. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0465-6 .

COVID-19 Rapid Reviews: Cochrane’s response so far. Available at: https://training.cochrane.org/resource/covid-19-rapid-reviews-cochrane-response-so-far . Accessed 1 June 2021.

Cochrane. Living systematic reviews. Available at: https://community.cochrane.org/review-production/production-resources/living-systematic-reviews . Accessed 1 June 2021.

Millard T, Synnot A, Elliott J, Green S, McDonald S, Turner T. Feasibility and acceptability of living systematic reviews: results from a mixed-methods evaluation. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):325. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1248-5 .

Babic A, Poklepovic Pericic T, Pieper D, Puljak L. How to decide whether a systematic review is stable and not in need of updating: analysis of Cochrane reviews. Res Synth Methods. 2020;11(6):884–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1451 .

Lovato A, Rossettini G, de Filippis C. Sore throat in COVID-19: comment on “clinical characteristics of hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: a single arm meta-analysis”. J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):714–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25815 .

Leung C. Comment on Li et al: COVID-19 patients’ clinical characteristics, discharge rate, and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(9):1431–2. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25912 .

Li LQ, Huang T, Wang YQ, Wang ZP, Liang Y, Huang TB, et al. Response to Char’s comment: comment on Li et al: COVID-19 patients’ clinical characteristics, discharge rate, and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(9):1433. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25924 .

Download references

Acknowledgments

We thank Catherine Henderson DPhil from Swanscoe Communications for pro bono medical writing and editing support. We acknowledge support from the Covidence Team, specifically Anneliese Arno. We thank the whole International Network of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (InterNetCOVID-19) for their commitment and involvement. Members of the InterNetCOVID-19 are listed in Additional file 6 . We thank Pavel Cerny and Roger Crosthwaite for guiding the team supervisor (IJBN) on human resources management.

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University Hospital and School of Medicine, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil

Israel Júnior Borges do Nascimento & Milena Soriano Marcolino

Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA

Israel Júnior Borges do Nascimento

Helene Fuld Health Trust National Institute for Evidence-based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare, College of Nursing, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA

Dónal P. O’Mathúna

School of Nursing, Psychotherapy and Community Health, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

Department of Anesthesiology, Intensive Care and Pain Medicine, University of Münster, Münster, Germany

Thilo Caspar von Groote

Department of Sport and Health Science, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany

Hebatullah Mohamed Abdulazeem

School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Health and Medicine, The University of Newcastle, Callaghan, Australia

Ishanka Weerasekara

Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka

Cochrane Croatia, University of Split, School of Medicine, Split, Croatia

Ana Marusic, Irena Zakarija-Grkovic & Tina Poklepovic Pericic

Center for Evidence-Based Medicine and Health Care, Catholic University of Croatia, Ilica 242, 10000, Zagreb, Croatia

Livia Puljak

Cochrane Brazil, Evidence-Based Health Program, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Vinicius Tassoni Civile & Alvaro Nagib Atallah

Yorkville University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada

Santino Filoso

Laboratory for Industrial and Applied Mathematics (LIAM), Department of Mathematics and Statistics, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Nicola Luigi Bragazzi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

IJBN conceived the research idea and worked as a project coordinator. DPOM, TCVG, HMA, IW, AM, LP, VTC, IZG, TPP, ANA, SF, NLB and MSM were involved in data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and initial draft writing. All authors revised the manuscript critically for the content. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Livia Puljak .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not required as data was based on published studies.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: appendix 1..

Search strategies used in the study.

Additional file 2: Appendix 2.

Adjusted scoring of AMSTAR 2 used in this study for systematic reviews of studies that did not analyze interventions.

Additional file 3: Appendix 3.

List of excluded studies, with reasons.

Additional file 4: Appendix 4.

Table of overlapping studies, containing the list of primary studies included, their visual overlap in individual systematic reviews, and the number in how many reviews each primary study was included.

Additional file 5: Appendix 5.

A detailed explanation of AMSTAR scoring for each item in each review.

Additional file 6: Appendix 6.

List of members and affiliates of International Network of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (InterNetCOVID-19).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Borges do Nascimento, I.J., O’Mathúna, D.P., von Groote, T.C. et al. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: an overview of systematic reviews. BMC Infect Dis 21 , 525 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06214-4

Download citation

Received : 12 April 2020

Accepted : 19 May 2021

Published : 04 June 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06214-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Coronavirus

- Evidence-based medicine

- Infectious diseases

BMC Infectious Diseases

ISSN: 1471-2334

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Now is the time for a 'great reset'

In every crisis, there is an opportunity Image: Space Uptopian/Unsplash