Food of West Bengal- Delectable Bengali Cuisines That You Must Try!

1. aloo potol posto.

2. Ilish Macher Jhol

5. Mutton Biryani

6. Aam Pora Shorbot

7. Tangra Macher Jhol

8. Alur Dom

10. Chholar Dal

11. Lau Ghonto

12. Mochar Ghonto

13. Kosha Mangsho

14. Mishti Doi

15. Patishapta

This post was published by Anindita Pal

Share this post on social media Facebook Twitter

West Bengal Travel Packages

Compare quotes from upto 3 travel agents for free

Darjeeling and Pelling Tour Package - Tiger Hill

7-day adventure in darjeeling, kalimpong, and d..., dooars & kalimpong tour package with jungle safari, 5 nights sikkim tour package: gangtok, pelling ..., sikkim bhutan bike trip - an adventurous journe..., darjeeling kalimpong tour package, related articles.

Food & Drink

28 Bengali Sweets That You Must Try At Least Once

Art & Culture

West Bengal Dress - Traditional Dress of West Bengal That Are Every Collector's Pride!

Culture of West Bengal

Airports in West Bengal

Sightseeing

West Bengal: The Sweetest Part of India

Fairs & Festivals

Durga Puja 2024 - One Month Gap Between Mahalaya and Shashti

A Colourful Guide to Basanta Utsav in Santiniketan

Historical & Heritage

Ruhr of India - The Hidden Minerals of Damodar Valley

Cyclone Amphan Left Devastation Behind in West Bengal & Odisha - These Pictures Are Proof

North Bengal : A Photographic Journey #TWC

Wildlife & Nature

National Parks in West Bengal For The Wildlife Enthusiasts

Hill Stations

Beautiful Hill Stations In West Bengal For A Summer Getaway

Heritage & Architecture

Top Historical Places in West Bengal

Beaches & Islands

Best Beaches in West Bengal That Every Traveller Should Visit

Trekking in West Bengal For A Thrilling Bengal Adventure

Top Religious Places in West Bengal

Top Places near rivers & lakes in West Bengal

Comments on this post

Top places in west bengal.

Get the best offers on Travel Packages

Compare package quotes from top travel agents

Compare upto 3 quotes for free

- India (+91)

*Final prices will be shared by our partner agents based on your requirements.

Log in to your account

Welcome to holidify.

Forget Password?

Share this page

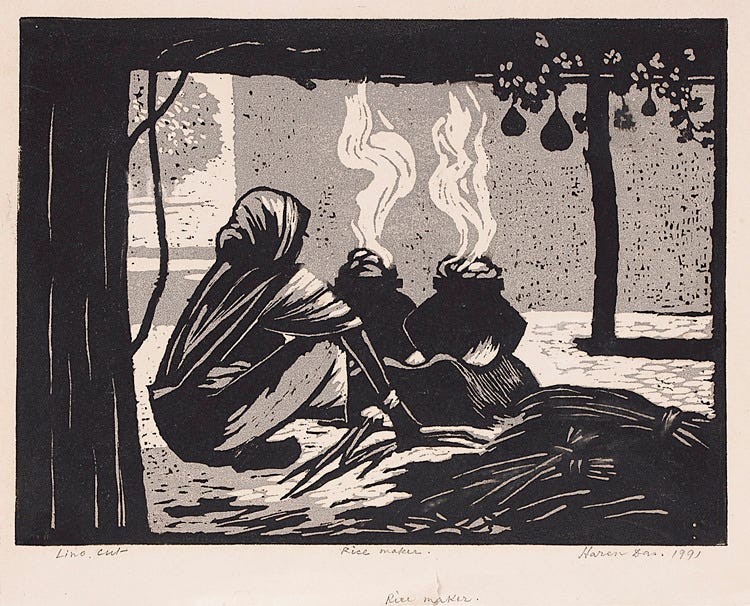

The Evolution of the Bengali Cuisine: From Local Delights to International Delicacies

Words by shiuli sural.

Welcome to the Brown History Newsletter. If you’re enjoying this labour of love, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your contribution would help pay the writers and illustrators and support this weekly publication. If you like to submit a writing piece, please send me a pitch by email at [email protected]. Don’t forget to check out our SHOP and our PODCAST . You can also follow us on Instagram and Twitter .

The Evolution of the Bengali Cuisine: From Local Delights to International Delicacies by Shiuli Sural

If we talk about Bengal, we talk about food. This unique cuisine has made its mark so strongly across the globe that a conversation about the region inevitably means a conversation about its food. Today I’m going to tell you a story – of my food, my home. You’re probably thinking this is a tale of maach-bhaat , kosha mangsho and sondesh but Bengali food is much more than these touristy dishes.

The cuisine of Bengal originated and evolved in the Bengal region - the Eastern part of the Indian subcontinent which includes Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and Assam's Barak Valley. This culinary style truly represents its diverse geographical setting. The staple foods, rice and fish, come from the traditionally renowned fertile agrarian plains and the seemingly inexhaustible rivers along the coasts of Southeastern India. The celebrated sweets of Bengal are mostly made using milk, ghee and butter, the result of dairy farming in the region. This remarkable landscape constitutes more than 222 million people, each household with its own recipe for each dish, reflecting an incredible amount of culinary expertise. The story of the cuisine of Bengal involves the complex and intricate interplay of heritage and diversity, religion and region, westernization and traditionality.

Around 5,000 years ago, rice emerged as a staple calorie resource as paddy cultivation came to Bengal from Southeast Asia. According to a government report from the 1940s, 3500 from the required 3600 calories for survival came from the consumption of rice. The rivers of the region brought seafood, especially fish, into the evolution of the cuisine. Rice and fish are still a very popular and common meal, hence the phrase “ Maache-Bhaate-Bangali ” which translates to “fish and rice make a Bengali”. Dal (lentils), another major staple, is mentioned in Bengali texts from the 15th century onwards. The text Mangalkavyas mentions different types of dals.

This post is for paid subscribers

National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

A taste of West Bengal, from curries to Kolkata street food

In the northeast Indian state — and particularly its capital, Kolkata — street food reigns supreme

There’s a Bengali expression, ‘ami machh bhat Bangali’, which means ‘I’m a typical Bengali who eats fish and rice’. Located in the Ganges River Delta, Bengal, a historical region between modern-day Bangladesh and India, is perfectly suited to rice cultivation. As for the ‘fishy’ element, fishing was a primary activity here, and in the northeast Indian state of West Bengal, fish is said to represent prosperity.

Various cultures have left an imprint on the cuisine of Bengal. The Nawab and Mughal dynasties introduced marinated meat, as well as the use of saffron and ghee. These flavours found their way into dishes such as biryani, korma and Kolkata’s renowned street foods, including kati rolls — flatbreads wrapped around various fillings and chutneys. They also introduced milk, cardamom and sugar to their desserts, and today, West Bengal is known for its array of sweets.

Arrivals from Europe brought their cuisines, too. The Christian community introduced the ritual of tea, while baking became widespread after the arrival of the British, as did chops and pound cakes. From the 18th century onwards, West Bengal became home to large numbers of Marwaris (a Rajasthani ethnic group) and Chinese people; the former introduced a range of vegetarian dishes, while the latter spiced up Cantonese dishes with hot sauces and chillies, with the likes of chilli chicken and chow mein becoming favourites in the state.

Bengali cuisine is packed with colour. During Durga Puja, West Bengal’s biggest festival, the goddess Durga is offered a bright yellow khichdi (a preparation of rice and daal) accompanied by various vegetable curries made without onion and garlic. But whether it’s the contrasting shades in the fruit and vegetable markets or the jars of yellow turmeric and pink rock salt that line home kitchens, you can expect vibrant hues all year round.

Three West Bengali dishes to try

1. Kati roll A fresh paratha flatbread fried on one side and filled with charred chicken and sliced onions. It’s drizzled with tomato sauce, chilli sauce and a dash of lime, rolled up and served hot.

2. Shorshe maach White fish fried with turmeric and salt, then simmered in a paste of mustard seeds and chillies. Served with steamed white rice, it’s a common dish in most households and restaurants.

3. Puchka Also known as panipuri, this beloved street snack is a thin, crispy puffed sphere filled with spiced potato and tangy tamarind water. A puchkawala makes these fresh, one by one, and they should be eaten whole.

For the young explorer

Related topics.

- FOOD CULTURE

- STREET FOODS

- FOOD TOURISM

- FOOD HISTORY

- CULTURAL TOURISM

You May Also Like

Why Jeonju is the best place to eat in South Korea

A taste of Hong Kong, the home of Cantonese food

Where to find the best pizza and street food in Naples

Özlem Warren on why Turkish food is great for vegetarians

From Flaounes to Magiritsa: Must-Try Greek Easter dishes

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Defining Bengali Cuisine: The Culinary Difference Between West Bengal and Bangladesh

- First Online: 19 May 2023

Cite this chapter

- Pinaki Dasgupta ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3230-694X 3

126 Accesses

1 Citations

Food is said to be a great redeemer. The Harappan civilization (3300 BCE-1800 BCE) and the first traces of urbanization gave insights into how food was cultivated and explored. Later, as the Vedic period set in 1600 BCE and onwards, agriculture evolved, and new kinds of food (grains, plants, seeds) were discovered. Norms were laid for society on how to eat, what to eat and when to eat. The Vedas and Upanishads of the period documented them for times to come. Buddhism and Jainism, which emerged during this period, also laid down rules and regulations on food and its consumption. The advent of the Mahajanpadas came into form during the 600 BCE and saw much of the strictures laid in the Vedic era being followed. Agriculture evolved and as kings and nobility came into a more structured form, food accordingly aligned to their taste and style. Perhaps with the Mughals and the Sultanate (1200CE–1858CE), food underwent major transformations in terms of the kind of ingredients used, style of cooking, and approach to cooking. The influence of the colonial era on the food of Bengal has left a lasting impression, along with the Mughlai cuisine. Today, the food of West Bengal and Bangladesh are different in terms of approach to cooking. The base ingredients and the spices remain the same. The demographic nature of Bangladesh and the demographic heterogeneity of West Bengal means that the kind of food and the range is diversified.

The author wishes to place on record his sincere gratitude to Sampada Kumar Dash, Research Fellow, IMI New Delhi for all the help and support during background research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Science and philosophy of Korea traditional foods (K-food)

What Belongs in the “Federal Diet”? Depictions of a National Cuisine in the Early American Republic

Definitions of hawaiian food: evidence of settler colonialism in selected cookbooks from the hawaiian islands (1896–2021).

Source Sen, Colleen Taylor. (2015). Feasts and Fasts: A History of Food in India . Reaktion Books.

Source ibid., 61.

Colombian exchange: The far-flung trading posts of the Portuguese and Spanish empires (Portugal was united with Spain between 1580 and 1640) became the hubs of a global exchange of fruit, vegetables, nuts and other plants between the western hemisphere, Africa, the Philippines, Oceania, and the Indian subcontinent

The piece has been taken from an article titled Bread and resistance in colonial Bengal by Mohd. Amar Alvi in Hypothesis: The recipe project (2022)—The aversion exhibited by upper-caste Hindus was predicated on a set of strong Brahmanical religious beliefs. In Hinduism, food can carry a plethora of diktats. It dictates your job, social status, whether you are “pure” or “polluted”, and whether you are entitled to enter a temple. The food one eats becomes the defining factor of one’s caste. One such way that upper-caste Hindus distinguish themselves from the lower ones is by denying the food touched or cooked by, the lower castes. A high-caste Hindu can only accept food or drink from a person of a similar rank. It must be rejected if the food is prepared or touched by a lower caste person. Therefore, accepting bread from Dalits’ hands would be polluting and profaning to savarnas (caste Hindus).

During the late 1800s, passengers took the East Bengal Express connecting the Gateway to the East, Calcutta, now Kolkata, with Goalondo, from where people took the ferry service on the Padma River to cross into the erstwhile East Bengal, now Bangladesh. From Goalondo Ghat people fanned out in different directions all over East Bengal and to the tea gardens of Assam or to Burma where there was a huge Bengali population. Sadly, the express train was discontinued in 1964 after the war, but one particular thing was not forgotten—the famous Goalondo fowl curry—this was served as the signature dish to the passengers travelling by the steamers that ferried from Goalondo Ghat. This is a light preparation of country chicken, cooked with basic spices by the boatmen who hailed from East Bengal and Chittagong.

Source https://www.thedailystar.net/lifestyle/spotlight/bangladesh-cuisine-part-i-delectable-and-diverse-1325551 (accessed on 31st October 2022).

Riaz is one of the top Bangladeshi food bloggers. He is active on several social media handles and can be found here on: https://www.youtube.com/c/AdnanFaruque .

BT- Bangladeshi Taka.

Use of the textile color in the bakery business or replacing ghee with dalda or even procuring sub standard inputs to cook.

Source https://www.thedailystar.net/business/news/restaurants-iftar-seasonsalvaged-food-delivery-platforms-1898902 (accessed 30th October 2022).

Source https://www.thedailystar.net/city/news/bleak-baishakh-restaurants-1892812 (accessed 30th October 2022).

Source https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/bengal-govt-to-extend-all-support-to-restaurant-sector-119070201470_1.html (accessed on 31st July 2022).

Achaya, K. T. (1994). Indian Food: Historical Companion . Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

Amin Al, M., Arefin, M. S., Sultana, N., Islam, M. R. (2021). Evaluating the Customers’ Dining Attitudes, E-satisfaction, and Continuance Intention Toward Mobile Food Ordering Apps (MFOAs): Evidence from Bangladesh. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 30 (2), 211–229.

Appadurai, A. (2007). Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value. In A. Appadurai (Ed.), The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective . Cambridge University Press.

Dey, S., & Maart, R. (2020). Decolonisation and Food: The Burden of Colonial Gastronomy—Stories from West Bengal. Alternation Special Edition, 33 , 290–329. Print ISSN 1023-1757; Electronic ISSN: 2519-5476; https://doi.org/10.29086/2519-5476/2020/sp33a12

Haldar, S. (2017). Bread, Biscuit and Fowl. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 78 , 660–667. Published by: Indian History Congress.

Ishani, C. (2017). A Palatable Journey through the Pages: Bengali Cookbooks and the “Ideal” Kitchen in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century, Global Food History, 3 (1), 24–39, https://doi.org/10.1080/20549547.2016.1256186

Article Google Scholar

Mitra, R. (2019). Eating Well in Uncle’s House: Bengali Culinary Practices in a Bucolic Calcutta/Kolkata in Amit Chaudhuri’s A Strange and Sublime Address. Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935).

Naumov, N., & Hassan, A. (2022). Gastronomic Tourism in Bangladesh: Opportunities and Challenges. In Hassan, A. (Ed.), Tourism in Bangladesh: Investment and Development Perspectives (pp. 165–176). Frankfurt: Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-1858-1_11

Ray, U. (2012, May). Eating ‘Modernity’: Changing Dietary Practices in Colonial Bengal. Modern Asian Studies, 46(3), 703–730. Cambridge University Press.

Ray, U. (2015). Culinary Culture in Colonial India—A Cosmopolitan Platter and the Middle-Class . Cambridge University Press.

Sen, C. T. (2015). Feasts and Fasts: A History of Food in India . Reaktion Books.

Sengupta, J. (2010). Nation on a Platter: the Culture and Politics of Food and Cuisine in Colonial Bengal. Modern Asian Studies, 44, 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X09990072

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Marketing Area, IMI, New Delhi, India

Pinaki Dasgupta

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Pinaki Dasgupta .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

International Management Institute, New Delhi, India

Arindam Banik

College of International Management, Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University, Beppu-shi, Oita, Japan

Munim Kumar Barai

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Dasgupta, P. (2023). Defining Bengali Cuisine: The Culinary Difference Between West Bengal and Bangladesh. In: Banik, A., Barai, M.K. (eds) Two Bengals. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-2185-0_11

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-2185-0_11

Published : 19 May 2023

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-99-2184-3

Online ISBN : 978-981-99-2185-0

eBook Packages : Economics and Finance Economics and Finance (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

A Curious Cuisine: Bengali Culinary Culture in Pre-modern Times

Somshankar Ray

Somshankar Ray is Assistant Professor,Department of History, Vidyasagar College for Women, Kolkata

The Proem : It is often said, half-jokingly, while others eat to live, the Bengalis live to eat. All Bengali rituals and festivities end up with one thing, hearty feasts involving an astonishing number of intricately prepared dishes. In this essay we try to analyse the development of Bengali cuisine in the early modern age, i.e., the 18th and early 19th centuries, an era when colonial influence was still not predominant. We focus primarily on the Indian state of West Bengal, and mainly discuss the history of cooked food.

The 18th and early 19th centuries are crucial phases in Bengal’s history, when Bengali culture emerged in many of its present aspects. Rooted to its indigenous elements, it was also heavily influenced by the Mughals and the Europeans who were prominent in Bengal by 1650. In the 18th century, the class of bhadralok , who would play a decisive role in Bengali society and culture from the 19th century, started taking shape (Ray 1994:128, Mullick 1910). [1] Members of this class were Hindus, mostly of high caste, literate, employed in the offices of Mughal officials and zamindars or teaching institutions, and cultivated the cosmopolitan Mughal culture. Also, Shakti worship, a typical feature of the Bengali Hindus, started becoming popular around this time. All these developments influenced the shaping of the culinary culture in pre-modern Bengal.

Bengali culture started taking a recognizable form from the 15th century. The food habits of the Bengali people between the 15th and 17th centuries can be inferred from contemporary literature such as the Mangal Kavyas and the Vaishnava texts. The Mangal Kavyas were poetic compositions about local deities which were very popular among rural masses. They played an important part in consolidating Hindu identity in medieval western Bengal. From sources like Manasamangal we come to know that the Bengalis freely consumed meat and wine. Wine was made from milk, coconut water, palmyra juice, sugarcane molasses and rice.

According to Narayan Deb’s Manasamangal , at the wedding of Behula 12 types of fish and 5 varieties of meat were cooked (Banerjee 1908:408). [2] In Ghanaram Chakravarti’s Dharmamangal we see that the kings entertained even the monks with meat (Ghosh 2003:16). [3] However, the influence of Sri Chaitanya transformed Bengali habits to a great extent. Sri Chaitanya and some of his associates appreciated good food but were strict vegetarians. Here one can cite an example of the menu of a Vaishnava feast where many vegetarian items were prepared:

Rice with ghee, shak, muger dal , mixed curry with patal, bori and other vegetables, fried fresh neem leaves, fried brinjal, bori and mocha ghanto (banana flower), coconut, dense milk, payes (sweetened rice with milk), banana, dahi (sweet curd), milk and dried rice ( chire ) etc.

Pratulchandra Gupta, Itihaser Golpo (1986:114)

Potato was still not a part of the Bengali diet, onions and garlic were also considered unfit for consumption. Influenced by Chaitanya’s way, many of the respectable Bengalis did not consume non-vegetarian food, even the Shaktas partook of mutton and fish only on specific occasions. However, they sometimes ate deer and lamb meat (Ray 1876:33). [4] This attitude persisted in the 18th and even in the 19th century. In water-body–dominated East Bengal, fish eating was more prevalent. According to Bijoy Gupta, a composer of Manasamangal, people there enjoyed diverse fish like kharsun , prawn, rui, chital, bain and shol . They were cooked with rich spices like green/red chilli paste and cumin. Turtle meat and eggs were also in demand (Banerjee and Das 1943).

The Transition : In the 18th century, we find some important changes in food habits of Bengali. A large number of sweets, both fried and made of posset or cottage cheese ( chhana ), entered the cuisine. Till the 16th century, Bengalis could not be termed connoisseurs of sweets as they were satisfied with simple dudh-chire (milk and flattened rice), dudh-lau (milk and gourd) and monda . Some country-made crude pulses ( mung) and coconut products were also available. Many attributed the sudden development of the sweet industry in Bengal to the Portuguese. It is impossible to think of Bengali food without sweets made of posset or cottage cheese; rossogolla , sandesh and chumchum are inseparable parts of Bengali culture. Actually, one cannot find any mention of cottage cheese in Bengali texts till the 16th century, as among the Hindus curdling the milk to make posset and cottage cheese was considered improper. Cottage cheese made in Portugal is almost identical with the Bengali version of cheese ( chhana ), so many credit the Portuguese with importing cottage cheese to Bengal. The Portuguese introduced three types of cheese in Bengal: cottage cheese, Bandel cheese and Dhakai paneer. However, one may attribute the improvement of Bengali confectionary in the 18th century to urbanization and the growth of a cosmopolitan urban culture. In this era, Murshidabad, Barddhaman, Bishnupur and Krishnanagar in western Bengal, along with Dhaka and Natore in eastern Bengal became major urban centres. Naturally, a landed and professional elite ( bhadralok ) populace grew up there which was not satisfied with simple country-made products and demanded more sophisticated food products. Later Bhabanicharan Banerjee noted how in the early 19th century urban centres such as Janai, Shantipur and Barddhaman were becoming well known for specific sweets like raskara, moa and ola .

Along with the Portuguese, another group of people who profoundly influenced Bengali culture were the Mughals. Before the Mughal conquest of 1576, Bengal was ruled by Muslim rulers of foreign origin who had no connection with Delhi, and therefore were susceptible to indigenous influences. However, after the Mughal victory, Bengal became a peripheral part of an all-India Empire and its regional identity was subsumed. The governors and their officials were inhabitants of north India and returned after their terms in Bengal. Hence they never became accultured. Influenced by them, many among the Bengali elite started practising north Indian customs and rituals (Banerjee and Das 1943:429). By the late 17th century we note the presence of a number of Mughal-influenced items in the Bengali repast. Bharatchandra Ray penned an authentic picture of the early 18th century Bengali life in his Annadamangal , which gave a list of dishes popular among the Bengalis. Here we find mention of turtle eggs fried with spices ( boda ) and sheek kababs (Ghosh n.d.) . Another writer Nehal Chand in his Paus Parban talked of kalia, kebab, kofta, korma , polau , dum and bhuna as Bengali favourites (Banerjee 2010[1966]:262). Meat cooked with onion, garlic and rich spices in Mughlai style became a part of the Bengali culture in the 18th century and continued till the early decades of the 19th century.

Iswar Gupta, the poet recorded the fascination for mutton among contemporary Bengalis (Samad 1991:165). [5] Around the same time the demand for better quality of fish was growing amongst the urbanized Bengalis. Bharatchandra lists bhetki, bacha, kalbos, pabda and ilish among the species of fish eaten by his contemporaries. Significantly, these names are not found in earlier, more rural poetic compositions. However, most of the Brahmins maintained some orthodoxy. On festive occasions they partook of luchi, kachuri , vegetable preparations like chhakka and shak bhaja , and a variety of sweets. Mutton was cooked in their kitchens in simple style, without garlic, onion or rich spices. An example of the elaborate meals which the zamindars or the landed elite consumed daily may be found in Byanjan Ratnakar , a classic cookbook compiled at the behest of Mahatapchand, the Maharaja of Barddhaman. This work was inspired by the recipes written down by Niyamat Khan, the chief cook of Emperor Shah Jahan. It listed 18 types of kebab and 19 types of kalia which were regularly gluttonized by the Barddhaman Rajas (Mullick 1910:379).

Thus we see that by the 18th century the mainstream Bengali cuisine with which we are familiar was gradually assuming recognizable shape. However, there were still some important differences with the present-day courses. Potatoes, cauliflower, cabbage were still not popular. Meat was not prepared during festive occasions like marriage and the thread-wearing ceremony ( upanayana ). Even other dishes were not cooked with salt, as food containing salt was considered contaminated. Salt was presented to the invitees in a separate container and they added it to their food according to need.

Among vegetables to be fried, brinjal and patal (pointed gourd) were still not popular, though pumpkin was. Among fruits, mango, jackfruit, banana, berry, tamarind, pomegranate, myrobalan, sugarcane, fig and date were found aplenty. Pineapple and papaya were products imported by the Portuguese from South America. Consumption of mangoes was made popular among the elite by the Mughal officials who promoted its cultivation in North India. Banana was a favourite within the Vaishnavas who partook of it along with milk and country sugar. Vaishnavas, being vegetarian, encouraged fruit consumption. Bengal was a fertile region, so even poor people had enough to eat. They consumed one meal every day which consisted of coarse rice, ghee, three types of vegetable dish, including pat shak and ghonto (mixed vegetable). The poor often immersed various vegetables and lemon in a water-filled pot through the night and consumed them the next day with salt. They also had the meat of hedgehog, mongoose and iguana. Another dish popular among them was muri (puffed rice), mixed with ghee, onion and green chilies. Sour curd was consumed to neutralize the hot flavour of green chilies.

The Localities – western Bengal: In this section we will look at the emergence of distinct savouries in some of the major localities in West Bengal. By the early 19th century the rarh region and the adjacent areas had developed a culinary pattern. The more affluent people partook of fine rice (processed with husk pedal), mung pulse with grated coconut, a variety of fish preparations like jhal and jhol , pickle, dahi and sandesh . Famiies with more limited means had rice, kalai dal (pulses), various dishes of locally cultivated vegetables, posto (poppy seed), ambal (liquid pickle) and fish. The dishes prepared here were lightly spiced and gently tasty. Barddhaman is a large and ancient district of Rarh which occupies the heartland of modern West Bengal. In older times, Barddhaman Bhukti and the Barddhaman Raj used to embrace a broader area including much of Hooghly, Howrah and Medinipur. The traditional specialities of Barddhaman consists of, along with rice, kalai dal , posto , bori (dried pulse ball) , kachu-kumror ghonto (mixed vegetable dish cooked with pumpkin and erom), machher ombol (fish chutney). Posto- chingri (prawn cooked with poppy seed juice) is a local delicacy. These items must have been in vogue from medieval times.

Among the sweets of the district, sitabhog and mihidana of Barddhaman proper and langcha of Shaktigarh have achieved almost international fame. However, they are of comparatively recent origin, and possibly became popular only in the late 19th century. Traditional sweets which go back to the 18th century include monda, batasa and kadma , all made of country sugar, chhana bora (cottage cheese balls) and coconut preparations (Chaudhuri 2010b).

Nadia district has an extremely rich cultural heritage. It is famous as the abode of Vaishnava scholars. So naturally Nadia has a glorious tradition of sweet making. Most of the famous sweetmeats of the district are made of cottage cheese and sugar. So it seems that they must have originated in the 18th century. The list includes well known dainties like sarpuria, sarbhaja , sartakti (all made of milk cream), along with dedomonda (made of cottage cheese and khejur gur or date juice syrup), nikhuti of Shantipur, chhanar jilapi of Muragacha and pantua of Ranaghat. All these are basically made of cottage cheese fried in ghee and dipped in sugar syrup. Late 19th-century preparations include variants of rossogolla and chumchum (Anonymous 1940:197) . The district of Murshidabad is famous for its Nawabi culture. However, apparently no independent cuisine could emerge here. The Muslim nobility of this place consumed biryani, kebabs, other meat dishes, raita , and firni. Among the sweetmeats of the place, only chhanabora deserves a special mention (Mitra 1948:932). This sweet assumed its familiar shape in the 18th century as Murshidabad became an urban centre. The nearby district of Maldah is distinguished for its pre-modern desserts like mohunbhog, khaja and rasakadamba , a primitive variant of rossogolla (Chandra 2004:298 ). Hooghly is a district neighbouring Barddhaman. This tract is unique because a number of European nations such as the French, the Dutch, the Portuguese, the Danes and even the Armenians and the Germans had their settlements there. Hooghly was also the home of many small principalities which were autonomous till the early 18th century, when they were swallowed up by the Barddhaman Raj. Naturally, the cultural tapestry of Hooghly is of colourful and complex design. Each major habitat has its own distinct savoury, such as monohora of Janai, k haichur of Dhaniakhali, sandesh of Guptipara, pantua of Jangipara, karakanda of Khanakul, jilapi of Kamarpur, rasakara of Gaurhati and gunpho sandesh of Srirampur (Chaudhuri 2011:15–16).

These are the preparations which developed in the 18th and early 19th century independently of Calcutta’s cosmopolitan urban milieu. Bankura too had its separate confectionery culture which emerged under the Malla Rajas of Bishnupur. The Malla Rajas became Vaishnava devotees from the 16th century. Then they actively encouraged the growth of a sweet-making industry based on milk products. It is said that the Rajas settled one milkman ( goala ) and a confectioner ( modok ) near each of the numerous Krishna temples that they constructed. Thus the art of sweet making boomed in Bishnupur during the 17th and early 18th centuries. The noted sweets which came into being then included mithai of chholar besan (gram flour) and ola made of dola Sugar. However, the pièce de résistance of Bishnupur is matichur, a smaller and more delicate version of bonde. No artificial color was added to this sweet (Chaudhuri 2010:196–97). Sadly, but inevitably, this sweetmeat, like many other country products, has disappeared with the advancement of industrial society based in Kolkata.

Eastern Bengal : Coming to Eastern Bengal, Dhaka the metropolis of the region, had developed a distinct food culture of its own by the early 19th century. It was famous for its amriti jilapi, malai, chhana , pranahara sandesh , pat kkhir wrapped in banana leaves, kkhir malpoa, sweet doi (curd), goja, khaja, lalmohan, nadankhara and bakharkhani sweetened breads (Bose 2004:34–35). Dhaka was a socio-culturally developed and naturally fertile area. So refined vegetarian and non-vegetarian cuisine could flourish here. Buddhadeb Bose, writer originally from Dhaka, wrote with nostalgia about the traditional delicacies of Dhaka which came into vogue by the early 19th century (Chaudhuri 2002:275). They included kachubata (erom paste) cooked with sarshe (mustard), dhanepata (coriander leaves) and coconut, kasundi (mustard sauce), khensari dal with saluk danta , gime bada with fried neem leaves. Women of Dhaka could cook easy-to-digest delicacies with even the skin of potatoes, pumkin and gourd. Among the fish preparations mourala fish with uchhe (bitter gourd), kacki fish crispy fried, koi in mustard oil with cauliflower, mung pulse soup with muro (head) of rohu fish, prawn in coconut sauce, spicy balls ( muittha) of chital fish, pabda fish with coriander and dried pulse balls ( bori ), magur fish cooked richly with onion, garlic and chillies and of course a large variety of hilsa dishes. Among the food products of Dhaka, fragrant kalojire rice and white, fine chire made from it were famous. Food was generally very cheap. However, the dishes of coastal Bengal which were coarser and influenced by the Burmese and the half caste Indo-Portuguese, often did not find favour with the mid-land Bengalis. Iswar Gupta, the poet, wrote a travelogue about various districts of Bengal. There he noted that the fish available at Chattagram were not fit for bhadralok consumption. They include shuntki (dried small fish), rotten prawns, laksha , topse and loitta . Owing to lack of communicaton, fresh products are not found in the markets. So the fish there were stale and costly. Sweets, clarified butter, jaggery and flour were of bad quality. So the Bengali bhadralok could not have any dining pleasure there. The only good point was that meat was available aplenty as chicken, goats, lambs and pigs could be procured easily. However Bengali bhadralok then did not appreciate meat (Majumdar 1979:17). He also made adverse remarks about Barisal-Bakharganj. He wrote that people there did not know how to cook. They mixed raw fish with oil, onion, garlic and other vegetables and prepared repulsive dishes like rasa . Crab and turtle meat cooked with grated coconut were considered delicacies. It seemed that the people of coastal Bengal had an inclination towards rice rather than flour products like roti . The food generally was hot and spicy, forming interesting contrast with that of Western Bengal. The other parts of Eastern Bengal also had distinct culinary culture. On festive occasions the people of Mymensingh prepared a number of dal (pulse soup) dishes. They included soup with bitter gourd, soup with vegetables and soup with muro (fish head). Sylhet was known for its lali treacle and sweets made of coconut. Even in the late 19th century sweets made of chhana like sandesh and rossogolla were not prepared there.

Signing off : Eighteenth-century Bengali cuisine went through some important modifications. During this time Bengal was in communication with the Mughals and the Europeans, Vaishnava and Shakta ideologies became more clearly defined, and increasing urbanization and the growth of urban culture was also significant. This led to a curious combination of culinary cultures developed in 18th century Bengal which is relevant to an extent even today.

Anonymous. 1940. Banglai Bhraman . Kolkata: Eastern Railway Publication.

Banerjee, Asitkumar. 2010[1966]. Bangla Sahityer Sampurna Itibritta . Kolkata: Modern Book Agency.

Banerjee, Brajen and Sajanikanta Das, ed. 1943. Bharatchandra Granthaboli . Kolkata: Bangiya Sahitya Parishat.

Banerjee, Kaliprasanna. 1908. Banglar Itihas: Nawabi Amal . Kolkata: Students Library.

Bose, Buddhadeb. 2004. Bhojon Shilpi Bangali . Kolkata: Bikalpo.

Chakraborti, Alok Kumar. 1989. Maharaja Krishnachandra o Tatkalin Bangasamaj . Kolkata: Mitram.

Chandra, Manoranjan. 2004. Mallabhum Bishnupur . Kolkata: Dey’s Publishers.

Chaudhuri, Kamal, ed. 2002. Brihattara Bakharganjer Itihas . Kolkata: Dey’s Publishers.

———. 2010a. Chattagramer Itihas . Kolkata: Dey’s Publishers.

———. 2010b. Murshidabader Itihas . Kolkata: Dey’s Publishers.

———. 2011. Dhaka-Bikrampur . Kolkata: Dey’s Publishers.

Ghosh, Baridbaran. N.d. ‘Menu’ in Sananda Magazine. Kolkata: Ananda Publishers.

Ghosh, Sudhangshu, ed. 2010. Manasamangal . Kolkata: Rajkrishna Pustakalaya.

Ghosh, Sudhangsuranjan, ed. 2003. Dharmamangal . Kolkata: Rajkrishna Pustakalaya.

Gupta, Pratul Chandra.1986. Itihaser Golpo . Kolkata: Ananda Publishers.

Majumdar, Lila. 1979. Rannar Boi . Kolkata: Ananda.

Mitra, Sudhir. 1948. Hughly Kahini . Kolkata: Sisir Publishers.

Mullick, Kumudnath. 1910. Nadia Kahini . Nadia.

Ray, Kartikeyachandra. 1876. Kshitishvamsabali Charita . Kolkata.

Ray, Rajatkanta. 1994. Palashir Sharajantra o Sekaler Samaj . Kolkata: Ananda Publishers.

Samad, Abdus.1991. Barddhaman Rajasrito Bangla Sahitya . Barddhaman.

[1] See also Banerjee and Das (1943), ‘Preface’; and Banerjee (1943), Chapters 12–14.

[2] Narayan Deb possibly composed his poem in the late 15th century. It was very popular in Mymensingh and Srihatta. So the food habits of those places find expression in his work. However, Manasamangal texts written by other authors also mention meat, fish and wine.

[3] Ghanaram composed his text in the early 18th century. He was an inhabitant of Barddhaman.

[4] For the formation of the recognizable Bengali Shakta ideology in the 18th century, see Chakraborty 1989 and Ghosh 2010. Bijoy Gupta composed his work in late 15th century. He was a resident of Barisal. However, many other unnamed authors added to this work in the later centuries. The earliest known manuscript of this work is dated 1695 CE.

[5] Banerjee in his magisterial survey mentioned Iswar Gupta as the last noted Bengali poet of the old school. Modernity was never significantly evident in his outlook.

More from Sahapedia

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Bengali cuisine is a culinary style from Bengal region in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent. Let’s take this short journey through traditional Bengali food & cuisine.

Bengali cuisine is the culinary style of Bengal, that comprises Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and Assam's Karimganj district. [1] The cuisine has been shaped by the region's diverse history and climate.

Bhavadeva Bhatta, in a text called Prayashcittaprakarana depicts some aspects of the Bengali cuisine. He describes how rice, fish, meat [4], different milk products, shak (varieties of spinach) [5], vegetables [6], and fruits [7] dominated Bengali eating culture at that time.

The mouth-watering Rosogullas, Chomchom, and Rasamalai, the super tasty Sorshe Ilish and Chingri Macher Malai Curry and but a few of the mouthwatering and tempting food of the highly illustrated and exquisite Bengali cuisine. Here are 15 Dishes of Bengali Food that you must try:

The most significant transformation of Bengali cuisine started from the late 18th century, as British rule expanded to Bengal. The Portuguese brought with them new food items like potato, chilli pepper, okra, tomato, cauliflower, cabbage, bread, cheese, jelly and biscuits.

Bengali cuisine is packed with colour. During Durga Puja, West Bengal’s biggest festival, the goddess Durga is offered a bright yellow khichdi (a preparation of rice and daal) accompanied by...

Let’s round-up some of the most popular Bengali foods. 1. Mangshor Jhol (Bengali Mutton Curry)

The influence of the colonial era on the food of Bengal has left a lasting impression, along with the Mughlai cuisine. Today, the food of West Bengal and Bangladesh are different in terms of approach to cooking. The base ingredients and the spices remain the same.

In this essay we try to analyse the development of Bengali cuisine in the early modern age, i.e., the 18th and early 19th centuries, an era when colonial influence was still not predominant. We focus primarily on the Indian state of West Bengal, and mainly discuss the history of cooked food.

The current study explores the roots, history and the current scenario of Bengali cuisine. The study also explores the traditional influence as well as cultural influence. The paper evaluates...