How to Do a Task Analysis Like a Pro

Task analysis is one of the cornerstones of instructional design. But what is it, really? The name says a lot: you analyze a task, step by step, to document how that task is completed.

At first glance, this seems like a straightforward thing. But even the easiest tasks can be quite complex. Things you do every day might seem simple when you first think about them. But what happens when you eliminate internalized or assumed knowledge?

Take sending an email. Easy, right? Maybe four or five steps?

- Click the New Mail icon

- Enter a Recipient

- Enter a Subject

- Enter your email text

But what about carbon copy or blind carbon copy recipients? What if you need to attach an invoice or picture? What app do you use to create the email in the first place (or are you sending from Gmail in your browser)? For that matter, from which device are you sending the email?

Suddenly that “simple” task is a set of processes, organized by device, operating system, and application, with various subtasks along the way accounting for mailing list complexities and the purpose of your email. As I was writing this I came up with about a dozen different variations, all of which would need to be closely analyzed and broken down precisely.

Even the most average task has a lot behind it.

This is why understanding how to do a task analysis is so important to becoming a successful instructional designer. When instructional designers create training, they’re teaching the learner how to accomplish something. Task analysis helps you focus on what they’re going to do and how they’ll do it (don’t worry so much about the why ; that comes later).

The easiest way to illustrate the process is with an example. Let’s say you work at a midsize media company and your boss asks you to complete a task analysis on how the company’s social media manager does her job. They want this documented for training purposes for future hires. That means you’ll need to:

- Identify the task to analyze

- Break down the task into subtasks

- Identify steps in subtasks

Let’s take a closer look at each of these steps.

Step 1: Identify the Task to Analyze

Tasks are the duties carried out by someone on the job. The social media manager carries out a lot of duties, so you need to be able to break them down into broad activities (aka tasks!) and focus on them one at a time. Don’t worry about all the little things that make up the task; we’ll get to that in a second. Here we’re looking to paint with broad strokes.

One of the social media manager’s tasks is to add new content to social media sites every morning. Your tasks should describe what a person does on the job and must start with an action verb.

So, in this case, the first task to analyze is “Add new content to social media.”

Step 2: Break Down the Task into Subtasks

Once you identify the task, you need to identify the subtasks, the smaller processes that make up the larger task. Remember in the email example above where I mentioned attachments and carbon-copying recipients? That’s the kind of thing you capture here. These should also be brief and start with an action verb.

Continuing the social media manager example, you need to find out the subtasks of adding new content to social media. You can figure this out by talking to or observing the social media manager. Through this process, you discover that the subtasks for adding new content to social media are:

- Check the editorial calendar

- Add new content to Twitter

You’re making good progress! You can now move on to Step 3.

Step 3: Identify Steps in Subtasks

Now it’s time to get into the nitty-gritty. You’ve identified the task and broken it down into subtasks. The final step, then, is to identify and list the steps for each subtask.

Do this by breaking down all of the subtasks into specific step-by-step, chronological actions. The key here is to use a “Goldilocks” approach to detail: not too much and not too little. Use just the right amount so learners can follow the instructions easily. Again, as with tasks and subtasks, your steps need to start with an action verb.

So, putting everything together from steps 1 and 2 and then breaking the subtasks into steps, your final task analysis would look like this;

1. Adding new content to social media

1.1 Check the editorial calendar

1.1.1 Navigate to the calendar webpage

1.1.2 Click today’s date

1.1.3 Click newest article title to open article

1.1.4 Click inside article URL bar

1.1.5 Copy URL for article to clipboard

1.1.6 Highlight title text of article

1.1.7 Copy the title text to clipboard

1.1.8 Close the calendar

1.2 Add new content to Twitter

1.2.1 Navigate to Twitter account

1.2.2 Log in to Twitter account

1.2.3 Click Tweet button

1.2.4 Paste article title from clipboard

1.2.5 Paste article URL from clipboard

1.2.6 Click Tweet button to publish

There are several ways to approach task analysis. It’s a fine art deciding how far down the rabbit hole you need to go with detail. Instructional designers can debate for hours whether saying “log in” is enough or if that needs to be broken down further into “enter user name,” “enter password,” and “click the login button.” Again, it all comes down to figuring out how much detail is just right for your audience.

Wrapping Up

That’s it! As you can see, while creating a task analysis boils down to “just” three steps, there are a lot of nuanced decisions to make along the way. Remember the Goldilocks Rule and always consider your audience and the seriousness of the subject matter when deciding just how nitpicky you need your task analysis to be. After all, there’s a marked difference between how much detail a learner needs when they’re learning how to perform brain surgery versus filling out their timecard.

Do you have any do’s and don’ts of your own for completing a successful task analysis? If you do, please leave a comment below. We love to hear your feedback!

Follow us on Twitter and come back to E-learning Heroes regularly for more helpful advice on everything related to e-learning.

Related Content

Top 3 types of e-learning analysis, 5 tips to improve your technical writing skills.

The One Thing You Need to Do to Organize Training Content: Task Analysis

20 comments.

- Christine Hounsham

- Akhila Vasan

- Jacinta Nelligan

- David Mayor

- Alexander Salas

- Nicole Legault

- Chris Purvis

- Jerrie Paniri

- Chris Janzen

Years ago, long before I ever even considered that I might possibly be an ID, my English professor assigned us a paper to write a set of directions for a task of our choosing that could be successfully executed by anyone who could read English. Coincidentally, like Jerrie, I chose making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, but for my part because I was lazy and wanted to pick a task for which it would be very easy to write the steps. Two days later I had a paper that was just shy of three pages (it was an English class, and we had to write it in prose, not instructional format), and a much deeper understanding of how much unconscious knowledge and experience we rely on to perform what we consider to be the simplest of tasks. I've never forgotten the lesson I got from writing that paper, an... Expand

- Caroline Smith

- David Kolmer

- Djuana Lamb

- Brock Lenser

- John Maical

Task analysis is a systematic process used to understand a task or activity in detail. It involves breaking down a complex task into smaller, manageable steps to identify the specific skills and knowledge required. Here's a guide on how to perform a task analysis like a pro: 1. Define the Task: Clearly define the task you want to analyze. Be specific about the goals and objectives. 2. Identify the Users: Determine who will be performing the task. Consider their background, skills, and knowledge. 3. Break Down the Task: Divide the task into smaller, manageable steps. Start with the overall goal and then break it down into subtasks. 4. Sequence the Steps: Arrange the steps in a logical order. Consider dependencies between steps and how they contribute to the overall task. 5. Gathe... Expand

- Abigail ava

Task Analysis: The Foundation for Successfully Teaching Life Skills

A Well Written Task Analysis Will Help Students Gain Independence

- Applied Behavior Analysis

- Behavior Management

- Lesson Plans

- Math Strategies

- Reading & Writing

- Social Skills

- Inclusion Strategies

- Individual Education Plans

- Becoming A Teacher

- Assessments & Tests

- Elementary Education

- Secondary Education

- Homeschooling

- M.Ed., Special Education, West Chester University

- B.A., Elementary Education, University of Pittsburgh

A task analysis is a fundamental tool for teaching life skills. It is how a specific life skill task will be introduced and taught. The choice of forward or backward chaining will depend on how the task analysis is written.

A good task analysis consists of a written list of the discrete steps required to complete a task, such as brushing teeth, mopping a floor, or setting a table. The task analysis is not meant to be given to the child but is used by the teacher and staff supporting the student in learning the task in question.

Customize Task Analysis for Student Needs

Students with strong language and cognitive skills will need fewer steps in a task analysis than a student with a more disabling condition. Students with good skills could respond to the step "Pull pants up," while a student without strong language skills may need that task broken down into steps: 1) Grasp pants on the sides at the student's knees with thumbs inside the waistband. 2) Pull the elastic out so that it will go over the student's hips. 3) Remove thumbs from waistband. 4) Adjust if necessary.

A task analysis is also helpful as well for writing an IEP goal. When stating how performance will be measured, you can write: When given a task analysis of 10 steps for sweeping the floor, Robert will complete 8 of 10 steps (80%) with two or fewer prompts per step.

A task analysis needs to be written in a way that many adults, not just teachers but parents, classroom aides , and even typical peers, can understand it. It need not be great literature, but it does need to be explicit and use terms that will easily be understood by multiple people.

Example Task Analysis: Brushing Teeth

- Student removes toothbrush from toothbrush case

- Student turns on water and wets bristles.

- Student unscrews toothpaste and squeezes 3/4 inches of paste onto bristles.

- Student opens mouth and brushes up and down on upper teeth.

- Student rinses his teeth with water from a cup.

- Student opens mouth and brushes up and down on lower teeth.

- Student brushes the tongue vigorously with toothpaste.

- Student replaces toothpaste cap and places toothpaste and brush in toothbrush case.

Example Task Analysis: Putting on a Tee Shirt

- Student chooses a shirt from the drawer. Student checks to be sure the label is inside.

- Student lays the shirt on the bed with the front down. Students checks to see that the label is near the student.

- Student slips hands into the two sides of the shirt to the shoulders.

- Student pulls head through the collar.

- Student slides right and then left arm through the armholes.

Keep in mind that, prior to setting goals for the task to be completed, it is advisable to test this task analysis using the child, to see if he or she is physically able to perform each part of the task. Different students have different skills.

- Chaining Forward and Chaining Backwards

- Hand Over Hand Prompting for Children With Disabilities

- Ideas for Teaching Life Skills in and out of the Classroom

- Teaching Life Skills in the Classroom

- A Dental Health Activity With Eggshells and Soda

- Personal Hygiene in Space: How it Works

- How to Successfully Teach English One-to-One

- Egg in Vinegar: A Dental Health Activity

- Gradual Release of Responsibility Creates Independent Learners

- Chunking: Breaking Tasks into Manageable Parts

- Dental Health Printables

- A Comprehensive History of Dentistry and Dental Care

- Functional Skills: Skills to Help Special Education Students Gain Independence

- IEP Goals for Progress Monitoring

- Writing a Lesson Plan: Independent Practice

- How to Set Up Classroom Learning Centers

Conducting Task Analysis

- First Online: 30 November 2018

Cite this chapter

- Chwee Beng Lee 4

724 Accesses

In instructional design, task analysis is one of the most critical components in which learning goals, objectives, types of tasks and requirements to perform the specific tasks are identified. In this chapter, we provide an overview of task analysis and discuss the most relevant task analysis methods with concrete examples. A s we focus on high-stakes learning environments and argue for the centrality of problem solving, we specifically discuss case-based reasoning and critical incident/critical decision methods that are highly relevant to problem solving.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Aamodt, A., & Plaza, E. (1994). Case-based reasoning: Foundational issues, methodological variations, and system approaches. Artificial Intelligence Communications, 7 , 39–59.

Google Scholar

Berkow, S., Virkstis, K., Stewart, J., & Conway, L. (2009). Assessing new graduate nurse performance. Nurse Educator, 34 , 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NNE.0000343405.90362.15

Article Google Scholar

Birks, M., James, A., Chung, C., Cant, R., & Davis, J. (2014). The teaching of physical assessment skills in pre-registration nursing programmes in Australia: Issues for nursing education. Collegian, 21 , 245–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2013.05.001

Brown, A., & Green, T. (2016). The essential of instructional design: Connecting fundamental principles with process and practice . New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1097/1001.NNE.0000343405.0000390362.0000343415

Book Google Scholar

Burns, P., & Poster, E. (2008). Competency development in new registered nurse graduates: Closing the gap between education and practice. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 39 , 67–73. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20080201-03

Crandall, B., Klein, G., & Hoffman, R. R. (2006). Working minds: A practitioner’s guide to cognitive task analysis . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hoffmann, R., & Militello, L. (2008). Perspectives on cognitive task analysis: Historical origins and modern communication of practice . New York: Taylor & Francis.

Jonassen, D., Strobel, Y., & Lee, C. B. (2006). Everyday problem solving in engineering: Lessons for educators. Journal of Engineering Education, 95 , 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2006.tb00885.x

Jonassen, D. H., Tessmer, M., & Hannum, W. H. (1999). Task analysis methods for instructional design . Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kolodner, J. (1993). Case-based reasoning . San Mateo, CA: Morgan-Kaufman.

Lee, C. B., Qi, J., & Rooney P. (2015). Capturing and assessing the experience of experiential learning: Understanding teaching and learning in a behaviourally challenging context . Western Sydney University. ISBN:978–1–74108-430-6.

Morrison, G. R., Ross, S. M., & Kemp, J. E. (2004). Designing effective instruction (4th ed.). New York: Wiley.

Riggle, J., Wadman, M., McCrory, B., Lowndes, B., Heald, E., Cartsens, P., et al. (2014). Task analysis method for procedural training curriculum development. Perspectives on Medical Education, 3 , 204–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-013-0100-1

Smith, P. L., & Ragan, T. J. (2005). Instructional design (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia

Chwee Beng Lee

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Chwee Beng Lee .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Lee, C.B. (2019). Conducting Task Analysis. In: Instructional Design Principles for High-Stakes Problem-Solving Environments. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-2808-4_10

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-2808-4_10

Published : 30 November 2018

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-13-2807-7

Online ISBN : 978-981-13-2808-4

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

How to Conduct a Task Analysis (With Examples)

Apr 16, 2024

Creating a to-do list and using a daily task tracker can go a long way toward helping you and your team get things done. But identifying and delegating tasks is only one part of the process. Performing a task analysis can help you refine the purpose of your task, break your task down into subtasks, and improve productivity and efficiency.

Team leaders in nearly any industry can perform a task analysis as a way to optimize internal practices, improve the customer experience, or even to assist employees with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) . Let’s take a look at what a task analysis is, how to perform a task analysis, and some real-world task analysis examples.

What Is Task Analysis?

Task analysis is the process of identifying the purpose and components of a complex task and breaking it down into smaller steps. Rather than trying to teach a new skill or process all at once, the purpose of task analysis is to separate it into individual steps that can be followed in a logical sequence.

The principles of task analysis can be used in product design and industrial engineering. It provides a method to better understand the way a customer uses a product and to design more user-friendly workflows. Forward and backward chaining can even be applied to systems that use artificial intelligence (AI) to make data-driven decisions and solve problems.

You’ll often see principles of task analysis applied to special education settings, which can inform employers who have employees with disabilities. For example, applied behavior analysis (ABA) is a type of therapy that uses task analysis to teach complex skills to children with autism spectrum disorder or other developmental disabilities.

In ABA therapy, practitioners use techniques like forward chaining to break down a task into a sequence of discrete steps. A related approach, discrete trial training (DTT) , can be used for teaching students everything from motor skills to daily living skills.

Types of Task Analysis

When using task analysis to plan a project or develop a new product, you can choose from one of two forms: cognitive and hierarchical. A cognitive task analysis is useful for tasks that require critical thinking or decision-making, while a hierarchical task analysis can be used for processes with a consistent structure or workflow.

Here’s how these two types of task analysis differ.

Cognitive task analysis

Let’s say you’re developing a new piece of software and you want to better understand how your customers will interact with the user interface. Rather than tell them how to perform a task, you simply give them a goal and watch how they achieve it.

Since different users will complete the task in a different way, you can use this analysis to identify pain points or understand how a customer’s knowledge and mindset inform their approach to completing the task.

Hierarchical task analysis

A hierarchical task analysis is one in which the process is fixed. In other words, you give the user a set of specific steps and watch how they perform each step of the task. You may discover that some steps are unnecessary or don’t serve the overall goal.

A hierarchical task analysis can be used to determine how long it takes to perform the total task process, and which steps can be eliminated with task automation .

How to Perform a Task Analysis in 4 Steps

The steps to conducting a task analysis will vary depending on whether you’re analyzing an internal process, a UX workflow, or a social or academic skill. But you can use these five steps to break down nearly any type of task and perform a task analysis as part of team project management or your own self-management process .

1. Define your goal

Start by defining the overall goal or task process that you want to analyze. This could be as simple as “Create a new user account and buy a product” or as in-depth as “ Run a post-mortem meeting and send out meeting minutes to everyone who attended.” The more specific your goal, the more useful your task analysis will be.

2. Create a list of subtasks

Next, break your higher-level task down into manageable steps. The idea is to create a list of all the subtasks that go into performing the task, even those that you might take for granted. You never know which tasks are slowing the whole process down.

For example, if you’re testing a new app, the first step might be “Turn on your phone” and the last step might be “Turn off your phone.”

3. Make a flowchart or diagram

A process flow chart or workflow diagram can help you determine which type of analysis to perform. Is your workflow a linear process with a series of discrete tasks that need to be completed in a specific order? Consider performing a hierarchical task analysis to find steps that you can automate or eliminate.

Is it more of a “choose your own adventure” in which different users will complete the task in a different way? Conduct a cognitive task analysis to identify pain points and prerequisites based on how different categories of users complete the task.

4. Analyze the task

Now, you can run through the process and pay attention to the length, frequency, and difficulty of each subtask. Were there any steps that you missed or that took longer than expected to complete? If another user performed the task, did they have the skills and knowledge necessary to complete the entire process?

You can use this information to make changes to the product or process, create more accurate documentation, or improve your training or onboarding practices.

3 Task Analysis Examples

The principles of task analysis can be applied to a wide range of scenarios, so let’s take a look at a few examples of task analysis in the real world.

Task analysis in UX design

In UX design, a task analysis may take the form of a focus group or usability testing. If you’ve just designed a new app, you might want to see how easy it is for customers to download the app and sign up for a new account. The process might look like this:

- Go to the App Store

- Search for the app

- Download the app

- Open the app

- Select “Create account”

- Enter your email address

- Verify your email address

- Choose a username and password

Upon conducting a task analysis, you determine that Step 7, “Verify your email address,” actually consists of multiple subtasks, such as opening up an email app. You decide to move this step later in the process to avoid disrupting the workflow.

Task analysis in project management

As a project manager, it’s important to know how your team members are spending their time so you can improve productivity and team accountability . Let’s say you want to find ways to delegate tasks more efficiently by using task automation. You come up with a list of the steps you usually follow to delegate tasks:

- Document action items during team meetings

- Add action items to your task manager

- Create a description for each task

- Assign each task to a team member

- Attach a due date to each task

- Send out a reminder email

After performing a task analysis, you determine that you don’t actually have to do any of these steps manually. You can use an AI task manager like Anchor AI to identify and delegate action items, attach due dates, and send out reminders automatically.

Task analysis for learning disabilities

In employment settings, a task analysis can be used to help employees with learning disabilities who otherwise struggle to complete tasks. One study found that individuals with intellectual disabilities were able to complete office tasks like scanning, copying, and shredding when they were broken down into steps like:

- Pick up documents from folder

- Open the scanner cover

- Place documents face-down on the scanner

- Close the scanner cover

- Press “Scan”

- Remove documents

- Return documents to the folder

Employees with learning disabilities may benefit from similarly specific instructions for other daily tasks, such as using time management tools or a password manager.

Streamline Task Management With Anchor AI

Performing a task analysis is a way of breaking down complex tasks into smaller steps so you can better understand how they all fit together. It’s used in workplaces, learning environments, and other settings to standardize processes, streamline workflows, and even teach social skills. You can use a task analysis to optimize internal processes or customer-facing workflows and eliminate unnecessary tasks altogether.

Anchor AI makes it easy to identify tasks and break them down into manageable steps with Max, your AI project manager. Simply invite Anchor AI to your next team meeting and Max will identify action items and delegate tasks automatically. Or, Ask Max for deeper insights into how specific tasks align with your overall project goals.

Sign up today to try it out for yourself and streamline task and project management!

Ready to shed the busy work?

Let Max 10x your grind so you can focus on the gold.

No credit card required. Free forever.

See what's included.

Feel the power of a personal AI project manager.

Investor inquiries

PR inquiries

General inquiries

Copyright ©2023 Anchor AI. All rights reserved.

Privacy policy

Terms and conditions

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Global Cognition

What is cognitive task analysis.

by Winston Sieck updated September 20, 2021

Cognitive Task Analysis helps you unpack the thought processes of experts, so you can teach them to others.

Have you ever needed to train novices to perform well on a real-world task or job that’s complex and poorly understood?

Some of your experienced people do it well. But you don’t have a clear understanding of how they do it.

You can observe the experts’ behavior. But that only gets you so far, especially when the tasks are complex. To really understand, you need to know what’s going on inside their heads .

You need to figure out what they know and how they think. You need access to their interpretations, their goals, the ways they frame problems and decisions, as well as the thought processes they employ to work through them.

Cognitive Task Analysis (CTA) is a family of psychological research methods for uncovering and representing what people know and how they think. CTA extends traditional task analysis to tap into the mental processes that underlie observable behavior, and reveal the cognitive skills and strategies needed to effectively tackle challenging situations.

At Global Cognition, we primarily apply cognitive task analysis to inform instruction focused on higher order thinking skills. This application is similar to the use of behavioral interviews to identify competencies in human resources research. However, CTA has also been used to design human-computer interfaces and other technological systems. There are numerous ways that cognitive task analysis can help boost performance in complex work settings. For example, CTA has provided significant input into our cultural competence modeling efforts.

What does a cognitive task analysis look like?

At this point in time, it really depends on the researchers conducting the analysis. As I mentioned above, CTA represents a family of methods. And it’s not a small family. In an overview chapter on cognitive task analysis, Richard Clark of the University of Southern California and his colleagues noted that there are currently over 100 types of CTA methods in use.

Regardless of the specific technique, CTA typically consists of several broad phases that the family holds in common:

Background preparation – getting familiar with the domain and population of interest. Reading through any existing manuals, doctrine, and holding informal discussions are common ways to start getting up to speed in the problem area.

Elicitation of knowledge – using one or more specific techniques to draw out the tacit knowledge and thought processes of experts. More on this below.

Analysis of qualitative data – sifting through the mass of data, usually in the form of transcripts of the experts’ verbal reports. Identifying decisions, cues, goals, strategies, concepts, and other elements of thought.

Knowledge representation – assembling those thought elements into a readily digestible format for understanding and communication. Usually, this means creating tables, charts, or diagrams that clearly represent the experts’ knowledge.

Design & develop applications – creating instruction, decision aids, or other applications using the newly constructed model of the experts’ knowledge as a starting point for ideation and design.

Knowledge Elicitation

To go a bit deeper into CTA methods, let’s take a look at one specific approach for eliciting knowledge, the critical decision method. First described by Beth Crandall, Gary Klein, and colleagues at Klein Associates, this is an interview technique for eliciting critical incidents to unpack the intuitive decision making of experts.

We’ll focus on this knowledge elicitation method because it distinguishes cognitive task analysis from other psychological research methods. Unlike the focus of many self-report survey methods, no one asks you to rate your opinions in a critical incident interview. And, this approach doesn’t lead you to assess your own personality, skills, or competence.

Instead, the idea of the critical decision method is to get experienced professionals to describe some of the toughest challenges they faced. By using carefully crafted probes, the CTA interviewer teases out how these people assessed situations and made decisions in critical moments of their experience.

So, how does the critical decision method work?

First, the CTA interviewer guides the subject-matter expert to identify a relevant incident. Next, the participant tells their whole story, without interruption. They are asked to recount the events in their entirety.

Then, the interviewer combs back over key points in the story several times to get the subject-matter expert to elaborate them. As they visit and revisit narrow slices of the experience, the interviewer and participant establish the critical decisions that were made, where understanding changed, and other turning points during the episode. The interviewer asks targeted questions to uncover the factors and cues noticed, goals adopted, and strategies used to resolve the incident.

Once the original story is fully fleshed out, the interviewer might ask hypothetical, “what if” questions to get a sense of anticipated outcomes that were never realized and trade-offs that were made.

Unlike the last monotonous phone survey you took, critical incident interviewers are not asking questions in lock-step fashion. Instead, they keep some flexibility to probe on aspects of a lived experience that make the most sense in the moment.

This semi-structured approach makes the critical decision method a fairly difficult interview to conduct. It takes some study and practice to learn how to execute it well. It’s also common for two interviewers to conduct the session together.

In the end, the interview produces a rich description of a critical incident and the cognition used to tackle it. In addition to observable details about the situation and behaviors, the cognitive task analysis interviewer dredges up information about the tacit knowledge, goal structures, and judgment and decision processes underlying the readily observable actions taken.

Cognitive Task Analysis for Instructional Design

These critical incidents, along with the decision points, cues, and strategies provide experience-based information that can be taught to novices.

One CTA, for example, uncovered the initial cues that experienced paramedics used to identify heart attack victims before they were fully symptomatic. These cues included changes in skin tone, the temperature of their skin, the state of their breathing and the patient’s mental state. Once they were identified, instructional materials were developed to teach new paramedics to recognize these subtle cues.

In addition to informing learning objectives, critical incidents provide a solid basis for creating informed, realistic scenario-based exercises. Along with providing a highly engaging instructional method, such exercises can expose learners to a variety of the tough situations they may encounter, and clue them in to the difficult decisions they’ll have to make. Further, they enable learners to practice the higher order thinking skills they’ll need to successfully work through challenging problems.

In all, using an expert’s knowledge, skills, procedures, and methods, locked inside incidents they have experienced, to design training materials can yield better decision-making processes for everyone.

Image Credit: johnhain

Clark, R., Feldon, D., Van Merrienboer, J. J. G., Yates, K., & Early, S. (2008). Cognitive task analysis. Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology . 577-593.

Hoffman, R. R., Crandall, B., & Shadbolt, N. (1998). Use of the critical decision method to elicit expert knowledge: A case study in the methodology of cognitive task analysis. Human factors , 40 (2), 254-276.

Study Smarter

Build your study skills with thinker academy.

About Winston Sieck

Dr. Winston Sieck is a cognitive psychologist working to advance the development of thinking skills. He is founder and president of Global Cognition, and director of Thinker Academy .

- Save Your Ammo

- Publications

GC Blog Topics

- Culture & Communication

- Thinking & Deciding

- Learning Skills

- Learning Science

Online Courses

- Thinker Academy

- Study Skills Course

- For Parents

- For Teachers

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

- Getting to IRCA

- What to Do If You Suspect Autism

- Learn the Signs. Act Early

- How and Where to Obtain a Diagnosis/Assessment

- After the Diagnosis: A Resource for Families Whose Child is Newly Diagnosed

- For Adolescents and Adults: After You Receive the Diagnosis of an Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Introducing Your Child to the Diagnosis of Autism

- Diagnostic Criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Diagnostic Criteria for Social (Pragmatic) Communication Disorder

- Indiana Autism Spectrum Disorder Needs Assessment

- Online Offerings

- Training and Coaching

- Individual Consultations

- School District Support

- Reporter E-Newsletter

- Applied Behavior Analysis

- Communication

- Educational Programming

- General Information

- Mental Health

- Self Help and Medical

- Social and Leisure

- Articles Written by Adria Nassim

- Articles by Temple Grandin

- Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA)

- Early Intervention

- Self-Help and Medical

- IRCA Short Clips

- Work Systems: Examples from TEACCH® Training

- Structured Tasks: Examples from TEACCH® Training

- Schedules: Examples from TEACCH® Training

- Holidays and Celebrations

- Health and Personal Care

- Behavior and Emotions

- After the Diagnosis

- Frustration

- Making Requests

- Trying New Foods

- Using Visual Supports

- Financial Resources

- Groups and Activities

- State Resources

- Materials Request

- COVID-19 Visuals and Social Narratives

- Family Support Webinars

- Foundations of Structured Teaching: A 3-day Hands-on Workshop

- Paraprofessional Training Modules

- Comprehensive Programming for Students Across the Autism Spectrum Training

- Workshops with Dr. Brenda Smith Myles

- Workshops with Dr. Kathleen Quill

- First Responder Training

- IRCA Briefs

Indiana Institute on Disability and Community

Indiana Resource Center for Autism

Applied behavior analysis: the role of task analysis and chaining.

By: Dr. Cathy Pratt, BCBA-D, Director, Indiana Resource Center for Autism and Lisa Steward, MA, BCBA, Director, Indiana Behavior Analysis Academy

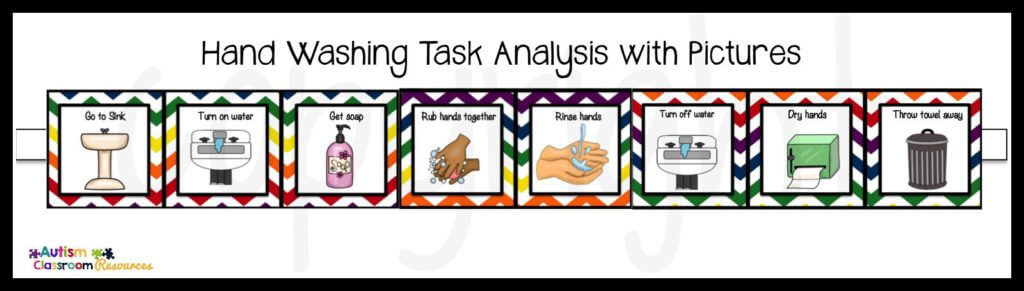

A task analysis is used to break complex tasks into a sequence of smaller steps or actions. For some individuals on the autism spectrum, even simple tasks can present complex challenges. Having an understanding of all the steps involved for a particular task can assist in identifying any steps that may need extra instruction and will help teach the task in a logical progression. A task analysis is developed using one of four methods. First, competent individuals who have demonstrated expertise can be observed and steps documented. A second method is to consult experts or professional organizations with this expertise in validating the steps of a required task. The third method involves those who are teaching the skill to perform the task themselves and document steps. This may lead to a greater understanding of all steps involved. The final approach is simply trial and error in which an initial task analysis is generated and then refined through field tests (Cooper, Heron, Howard, 2020).

As task analyses are developed, it is important to remember the skill level of the person, the age, communication and processing abilities, and prior experiences in performing the task. When considering these factors, task analyses may need to be individualized. For those on the autism spectrum, also remember their tendency toward literal interpretation of language. For example, students who have been told to put the peanut butter on the bread when making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich have literally just placed the entire jar on the bread. It is important that all steps are operationally defined. Below are two examples of task analyses.

Putting a Coat On

- Pick up the coat by the collar (the inside of the coat should be facing you)

- Place your right arm in the right sleeve hole

- Push your arm through until you can see your hand at the other end

- Reach behind with your left hand

- Place your arm in the left sleeve hole

- Move your arm through until you see your hand at the other end

- Pull the coat together in the front

- Zip the coat

Washing Hands

- Turn on right faucet

- Turn on left faucet

- Place hands under water

- Dispense soap

- Rub palms to count of 5

- Rub back of left hand to count of 5

- Rub back of right hand to count of 5

- Turn off water

- Take paper towel

- Dry hands to count of 5

- Throw paper towel away

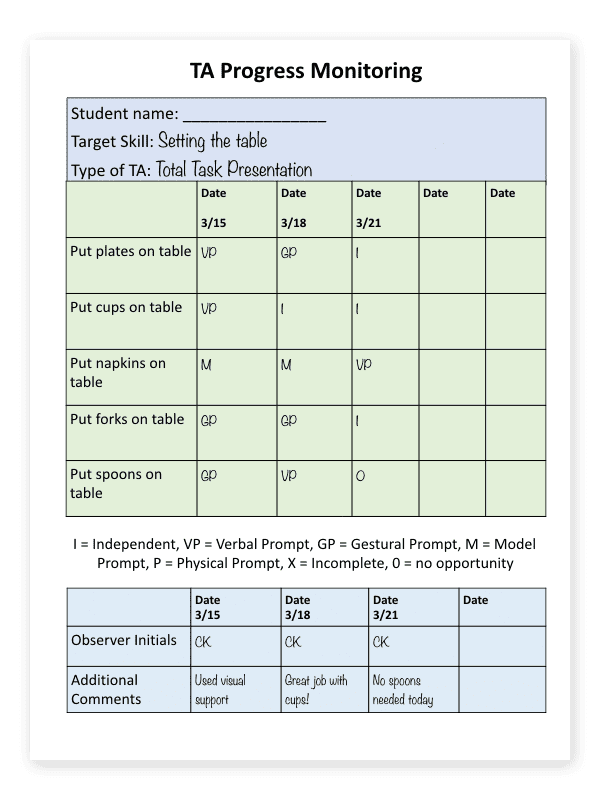

Skills taught using a task analysis (TA) include daily living skills such as brushing teeth, bathing, dressing, making a meal, and performing a variety of household chores. Task analysis can also be used in teaching students to perform tasks at school such as eating in the cafeteria, morning routines, completing and turning in assignments, and other tasks. Task analysis is also useful in desensitization programs such as tolerating haircuts, having teeth cleaned, and tolerating buzzers or loud environments. Remember that tasks we perceive as simple may be complex for those on the spectrum.

Again, the number of steps involved and the wording used will differ dependent on the individual. Determining the steps to a TA as well as the starting point for an individual often requires collecting baseline data, and/or examining the individual’s ability to complete any or all of the required steps. Assessing the individual’s level of mastery can occur in one of two ways. Single-opportunity data involves collecting information on each step correctly performed in the task analysis. Once a mistake is made, data collection stops and no further steps are examined. In multiple opportunity data collection, progress is documented on each step regardless of whether the performance was correct or not. This provides insight into those steps the student can perform and where additional training or support is needed. Remember that once implementation begins, the TA may need to be revised to address any additional needs.

Once a task analysis is developed, chaining procedures are used to teach the task. Forward chaining involves teaching the sequence beginning with the first step. Typically, the learner does not move onto the second step until the first step is mastered. In backward chaining, the sequence is taught beginning with the last step. And again, the previous step is not taught until the final step is learned. One final strategy is total task teaching. Using this strategy, the entire skill is taught and support is provided or accommodations made for steps that are problematic. Each of these strategies has benefits. In forward chaining, the individual learns the logical sequence of a task from beginning to end. In backward chaining, the individual immediately understands the benefit of performing the task. In total task training, the individual is able to learn the entire routine without interruptions. In addition, they are able to independently complete any steps that have been previously mastered.

Regardless of the strategy chosen, data has to be collected to document successful completion of the entire routine and progress on individual steps. How an individual progresses through the steps of the task analysis and what strategies are used have to be determined via data collection.

Cooper, J.O., Heron, T.E, and Heward, W.L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis (3rd Edition). Pearson Education, Inc.

Pratt, C. & Steward, L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis: The role of task analysis and chaining. https://www.iidc.indiana.edu/irca/articles/applied-behavior-analysis.html .

2810 E Discovery Parkway Bloomington IN 47408 812-855-6508 812-855-9630 (fax) Sitemap

Director: Rebecca S. Martínez, Ph.D., HSPP

Sign Up for Our Newsletter

The IRCA Reporter is filled with useful information for individuals, families and professionals.

About the Center

💻 Upcoming Live Webinar With Cofounder John Hollingsworth | Thursday, 5/16 at 1 PM PDT | Learn More

- Staff Portal

- Consultant Portal

Toll Free 1-800-495-1550

Local 559-834-2449

- Articles & Books

- Explicit Direct Instruction

- Student Engagement

- Checking for Understanding

- ELD Instruction

- About Our Company

- DataWORKS as an EMO

- About Our Professional Development

- English Learner PD

- Schedule a Webinar

- EDI and Hattie’s Visible Learning

- Classroom Strategy

EDI Activates 18 of the Top 30 Influences on Student Achievement, As Measured by Hattie

John Hattie, a professor of education from Australia and New Zealand, published Visible Learning in 2009 (with additional books in 2012 and 2015). The purpose of his research was to identify what works and what doesn’t in education in statistical terms. It was a groundbreaking analysis because, for the first time, educational methods could be compared in terms of effectiveness. The Times Educational Supplement called Hattie’s research “the holy grail of education.”

In reviewing Hattie’s descriptions of educational influences, Dataworks has found that Explicit Direct Instruction (EDI), which was developed by Hollingsworth and Ybarra as a collection of research-based teaching strategies for design and delivery of lessons, actually activates 18 of top 30 effects (out of 195 total). That means the EDI approach to education is a useful system for making learning visible, according to Hattie’s research.

Effect Size

Hattie analyzed 900+ meta-studies of educational programs and procedures, and came up with an “effect size” for each of 195 “influences” on learning (138 in 2009 and 150 in 2012). The range is from 0 to 1.62, with the larger effect being more valuable. Hattie found that .40 was the “hinge point” of usefulness.

Hattie said, “There is no fixed recipe for ensuring that teaching has the maximum possible effect on student learning, and no set of principles apply to all learning for all students. But there are practices that we know are effective and many practices that we know are not.” He concluded that if teachers are using practices that have a less than .40 effect, then it “may mean that teachers need to modify or dramatically change their theories of action.”

Visible Learning and Teaching

Hattie says “visible teaching and learning occurs when there is deliberate practice aimed at attaining mastery of the goal, when there is feedback given and sought, and when there are active, passionate, and engaging people (teacher, students, peers) participating in the act of learning.” Mansell (2008) describes this “holy grail” of education as “improvement in the level of interaction between pupils and teachers.”

Implications for Schools

Furthermore, Sebastian Waack from Edkimo, who writes the Visible Learning blog, says Hattie’s research has two main implications for teachers and schools. “ First, teachers are the central aspect of successful learning in schools. Second, Hattie’s results suggest that school reform should concentrate on what is going on in the classroom and not on structural reforms.” This supports the EDI mission of focusing on instructional excellence in the classroom.

Following are the specific ways that EDI correlates with Hattie’s top influences on learning. The effect size and year of publication are noted in the text for each influence .

Summary of How EDI Uses Top Effects of Hattie Research

Details of how edi uses top effects of hattie research, author: mike neer.

Mike has served as editor and curriculum researcher for DataWORKS since 2010. Previously, he taught English in middle school, high schools, and colleges in Illinois, Puerto Rico, and California. He has edited national trade magazines and presented seminars nationwide for businesses and non-profit organizations. He believes words are a powerful educational tool for reporting, reflecting, and revealing.

Related posts

Using Task Analysis to Teach Daily Living Skills

Educational Consultant

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Task analysis is used to break down complex skills into manageable, discrete steps. Students learn the individual steps in sequence in order to master the overall skill. Task analysis can be easy to use as it often requires few materials, can be inexpensive and can be used in a variety of settings. Most importantly, it supports students who have difficulty with executive functioning skills like sequencing, working memory and attention.

Start to think beyond academics and imagine the impact that task analysis can have in supporting your students’ daily living skills. Sequence the steps for hygiene activities like handwashing, toothbrushing or toileting. Provide supports for steps involved in household chores like dusting, cleaning the bedroom, clearing the table or picking up toys. Teach complex tasks in the kitchen like making a sandwich, putting away groceries and setting the table.

Planning for Task Analysis

Have a concrete goal in mind by clearly defining the expected behavior . Rather than simply saying that your student will wash their hands, it is helpful to explicitly state that your student will wash their hands with soap for 20 seconds and dry their hands when finished.

Before teaching the skill, ensure that each individual step is identified and put in the correct sequence. It can be helpful to perform the skill yourself, or observe another adult performing the skill, and record each individual step. For example, to develop a task analysis for washing dishes, start with the step of turning on the water. Complete and record each individual step, being careful not to leave out any detail.

As part of the planning process, take time to observe your student completing the target skill . This will give you a clear idea of what level and types of support to provide for each step of the task. It may also highlight any routines that your student has already developed around this activity as well as reveal areas of strength.

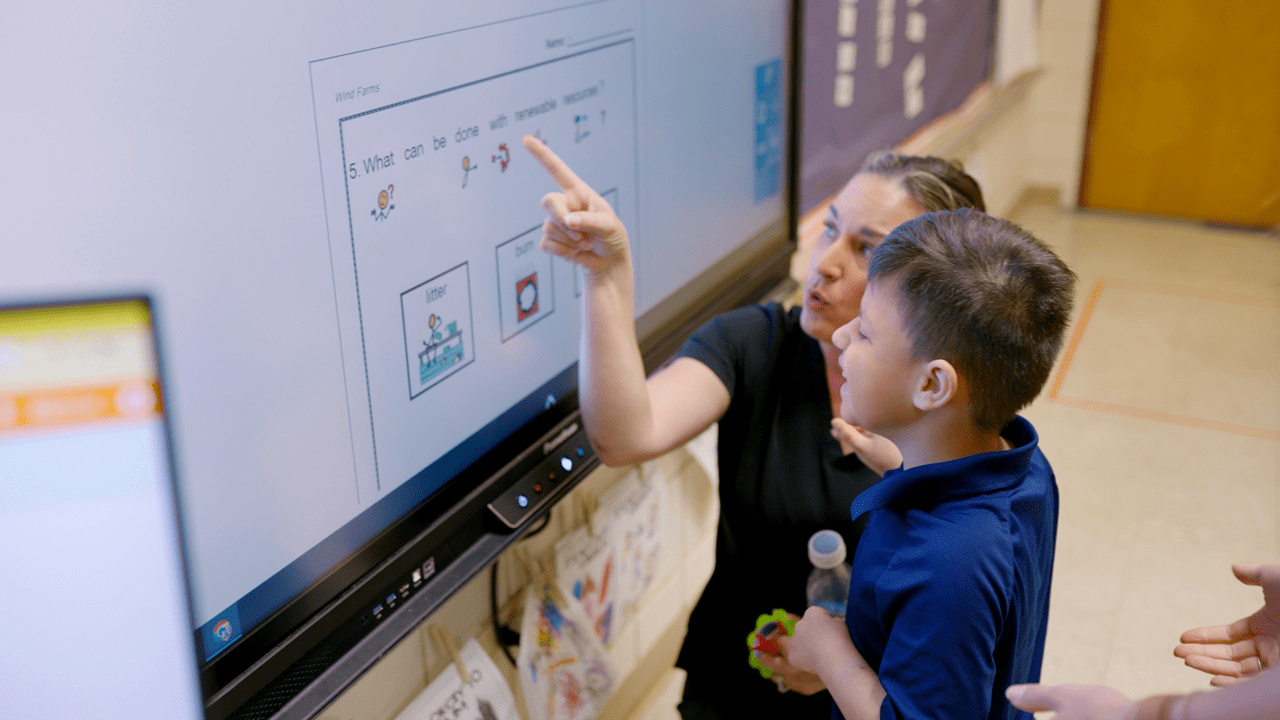

Once you have identified each step and observed your student engaging in the activity, think about how best to present the task analysis to your student. Line drawings or photographs like those in decision trees may be helpful to support some students. A written checklist might be appropriate for others. Even video modeling can be meaningful and appropriate for some students. Consider your student’s level of learning to determine the best presentation.

Tips for Implementing Task Analysis

Forward Chaining

Start by teaching and reinforcing the first step in the chain. Then support your student’s completion of the remaining steps by starting with the least amount of prompting necessary to help your student complete the step successfully. Again, an initial observation of your student’s skill can provide some insight into what level of support is appropriate. Once the first step is mastered (i.e., once your student can independently complete the first step), teach and reinforce the second step while continuing to support the steps that follow.

Backward Chaining

Start by teaching and reinforcing the last step in the chain as you provide a model and support for all steps prior to the last. As the last step is mastered, move backward in the sequence by teaching and reinforcing the second-to-last step. Backward chaining lets your student end every teaching session with success and positive reinforcement.

Total Task Presentation

Present all steps of the sequence at one time. Teach and reinforce each step of the process. This allows your student to learn a complete routine and understand the expectations of the full task from the start.

Task analysis is most effective when paired with a positive reinforcement . As your student performs an individual step or completes the total task (as described above), reinforce their behavior. Consider what reinforcers are motivating and meaningful to your student. This could be verbal praise, a high five or a small token. Keep it simple, and be sure that the selected reinforcer is effective for your student.

In addition to reinforcement, use task analysis in combination with other evidence-based practices. Various levels of prompting can support your student’s learning. Video modeling and visual supports, such as social narratives and decision trees , may also be used to clarify expectations and increase understanding of the skill being taught.

Monitor Your Intervention

Consider the Skill Itself

Has it been clearly defined? Is it truly measurable? Without these characteristics, student progress is difficult to accurately monitor. Also revisit your student’s skill level. Are the prerequisite skills truly present? Is the skill aligned with the IEP and achievable as it is written?

Look Closely at the Task Analysis

Is the skill completely task analyzed? Is there a step missing? Be sure that every step of the sequence is a discrete skill, and not a series of steps collapsed into one.

Review Implementation

If other team members are also teaching this skill, be sure that everyone is using the same chaining method for using task analysis. A thorough task analysis will support consistent implementation as well. Ensure that additional supports (video models, social narratives, visual supports, etc.) are being used in the same way each time.

Reconsider the Positive Reinforcement

If your student is showing a lack of progress, interest or engagement, it may be necessary to find a more effective way to reinforce the skill.

Task analysis can effectively be used to teach daily living skills by breaking down tasks into manageable parts. With thoughtful planning, consistent implementation and careful monitoring, you can support your student’s growth in this area.

About the Author

Becky Dees is an Educational Consultant who specializes in Autism Spectrum Disorder. She has worked as an autism clinician, an educational coach, and a special education trainer. Becky currently works with the autism group in research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Becky received her degree in psychology from UNC‑Chapel Hill.

You might also like...

Video: ULS in a Fresno, CA Classroom

Get Excited for Summer & These Updates!

ExcitED Preparing for End of Year and ESY

- Try & Buy

- Get a Quote

- Request a Trial

- Schedule a Demo

- Try some Samples

Select your role to sign in.

If you're signing into a trial, please select Teacher/Admin .

Teacher/Admin

How can we help you.

Ready to try or buy?

Contact Sales

Need product support?

Contact Customer Care

The Edvocate

- Lynch Educational Consulting

- Dr. Lynch’s Personal Website

- Write For Us

- The Tech Edvocate Product Guide

- The Edvocate Podcast

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Assistive Technology

- Best PreK-12 Schools in America

- Child Development

- Classroom Management

- Early Childhood

- EdTech & Innovation

- Education Leadership

- First Year Teachers

- Gifted and Talented Education

- Special Education

- Parental Involvement

- Policy & Reform

- Best Colleges and Universities

- Best College and University Programs

- HBCU’s

- Higher Education EdTech

- Higher Education

- International Education

- The Awards Process

- Finalists and Winners of The 2023 Tech Edvocate Awards

- Award Seals

- GPA Calculator for College

- GPA Calculator for High School

- Cumulative GPA Calculator

- Grade Calculator

- Weighted Grade Calculator

- Final Grade Calculator

- The Tech Edvocate

- AI Powered Personal Tutor

Teaching Students About the Coaching Legends of the Steelers: A Lesson in Dedication, Leadership, and Success

Teaching students about the tim donaghy scandal – learning from history, teaching students about kevin costner’s age: a unique approach to understanding hollywood’s history, teaching students about sonny landham: a journey through the life of a hollywood icon, teaching students about the summer olympics, teaching students about princess margaret’s death: an educational approach, teaching students about michael cole: an insightful approach to understanding a renowned journalist, college minor: everything you need to know, 14 fascinating teacher interview questions for principals, tips for success if you have a master’s degree and can’t find a job, what are the 4 components of task analysis.

Task analysis is a process in which broad goals are broken down into small objectives or parts and sequenced for instruction. Task analysis is the process of developing a training sequence by breaking down a task into small steps that a child can master more easily. Tasks, skills, assignments, or jobs in the classroom become manageable for all children, which allows them to participate fully in the teaching and learning process.

In early childhood settings, teachers focus task analysis on activities necessary for successful participation in the environment. Four ways to develop the steps needed for a task analysis include watching a master, self-monitoring, brainstorming, and goal analysis. Early childhood teachers can use each of these approaches to identify and record the 4 incremental steps:

–Watching a master: To know how to help children walk the balance beam, watch someone who is doing this task well.

–Self-monitoring: To know how to help children make a paper-mache turkey, review the steps that you follow in accomplishing the task.

–Brainstorming: To know how to help children plan a garden in a school plot, ask all the children to give you ideas

–Goal analysis: To know how to help children develop conflict resolution strategies, review the observable and nonobservable aspects of this task, and identify ways to see how it is accomplished.

It is important to remember that the number of steps in a task analysis depends upon the functioning level of the child as well as the nature of the task. I hope you enjoyed this brief explanation of task analysis and its 4 components. If you have anything that you would add to the article, please leave it in the comments below.

To help teachers further understand the components of task analysis and how it can be used in the classroom, below we have an included an informational video that was compiled by professors at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Concepts and Strategies for Serving the Whole ...

12 activities that teachers can use to ....

Matthew Lynch

Related articles more from author.

Why Verbal Comprehension is Essential to Academic Success

Raising a Narcissistic Child

Here’s why kids fall behind in science

How to Help College Students Develop More Grit

Expressive and Receptive Language Disorders: What are They?

What to Expect: Age 13

The Radiant Spectrum

Task Analysis in Special Education: How to Deconstruct a Task

- September 15, 2022 April 11, 2024

As educators, we often go through the process of deconstructing a task by breaking down a complex skill into smaller steps so that students are able to learn the skill gradually, and easily. This process is known as Task Analysis and is especially crucial when teaching students with special needs.

We typically learn in two ways, explicitly and implicitly. Explicit learning is the intentional experience of acquiring a skill or knowledge, while implicit learning is the process of learning without conscious and deliberate awareness, such as learning how to talk and eat. Our students with special needs benefit more from explicit teaching and learning because they often face challenges acquiring skills implicitly due to the need for contextual understanding, communication skills, and so on.

For explicit teaching and learning to be effective, it is important to have a thorough understanding of the skill through task analysis.

Task Analysis involves a series of thought processes:

1. Goal Selection: Know exactly what it is that you want to teach

Be clear and specific about the goal or the skill that you want to teach. Avoid having too many sub-goals.

- Negative example: Play a complete song.

- Positive example: Press keys on the piano by following the alphabets shown on a flashcard or music score.

2. Identify any prerequisite skills, if any

In our earlier example of teaching the sequence of piano keys, some of the prerequisite skills will include:

- Literacy skills of alphabets and/or colours

- Matching skills of alphabets and/or colours

- Visual referencing skills in top-down and/or left-right motion

- Motor skill of only using one finger to press the key, or to imitate an action

Prerequisite skills are important because these skills help to make the learning more feasible and increase the possibility of successfully performing the new skill.

3. Write a list of all the steps needed to complete the skill you want to teach

A skill can be completed in a single step, or in a series of sequential steps. It is thus helpful that we list down all the steps needed to complete the skill we want to teach. With this, the Task Analysis becomes more detailed and effective. Let’s take the above goal and list down the steps needed.

Goal: Press keys on the piano by following the alphabets shown on a flashcard or music score.

The keys steps needed to complete this task are:

- Look up at the flashed alphabet.

- Process and retain the information in the learner’s working memory.

- Look down at the piano keys.

- Find the corresponding key by scanning past non-target keys.

- Identify and stop at the target key.

- Aim and press with one finger.

4. Identify which steps your child can do and which he/she cannot yet do

The next step will be to know the current skill level of your learner by identifying which steps the learner can do, and which the learner cannot. Assume the learner has the following challenges:

- Not consistent in visual referencing skill of looking up and down repeatedly.

- Unable to focus and scan more than 4 keys at one time.

- Often mistakes Letter G for C and vice versa.

This means that this learner will have challenges in completing Steps 3, 4, and 5 in the above Task Analysis.

5. Isolate any gap skills, if needed, and teach them first

The steps in which the learner cannot do or has challenges in are known as gap skills . After identifying the gap skills, take time to isolate the skills, teach them, and bridge them. This process takes time. For example, looking at the gap skills in the above example:

- Visual Referencing Skill:

This is an abstract skill that takes time to build. It is unlikely that the learner can learn and master this in a couple of weeks. Therefore, to bridge this, the teacher should intentionally provide opportunities for top-down visual referencing across activities and settings, such as taking a toy from a shelf above and keeping them back on top, or sorting activities whereby one item is on top, and one is at the bottom.

- Working Memory Stamina

This is also another skill that takes time to build. Teaching it across settings and activities will be more effective and efficient.

This is a skill that can be taught together with the target skill. Since the learner mistakes G for C and vice versa, and is unable to scan more than 4 keys at any one time, reduce the sequencing to CDEF or FGAB such that there is only either C or G in the target sequence. Once the learner is more confident, isolate C and G so that the learner learns to differentiate the two before the full sequence is introduced again.

Once the gap skills are bridged, the likelihood of the learner performing the target skill will increase vastly.

6. Determine the strategy to be used when completing the target skill, with or without gap skills

At this stage, the learner might still have some gap skills to work on, but the teacher decides to move on to teaching the actual target skill. There are generally three strategies to use:

- Backward Chaining

As the name suggests, Backward Chaining involves the teacher helping the student complete all the steps in the front, leaving only the last step for the learner to do. This also means that the teacher focuses on the last step in the teaching process. The teacher then slowly moves to teach the step before the last until the learner is able to complete all the steps.

- Forward Chaining

This is the opposite of Backward Chaining. The teacher starts teaching from the first step and then moves on chronologically.

- Total Chaining

This strategy involves the learner in all the steps and the teacher teaches all the steps to the learner with prompts. The learner is learning all the steps.

It is common to have tried all three strategies before the teacher is able to decide which one works best, so do not be afraid to evaluate and change your mind halfway!

7. Develop a systematic teaching plan, implement, assess and evaluate the progress

After you decide on your teaching strategy, you can then plan and start the actual teaching. Do remember to assess and evaluate the learner’s progress regularly so as to make the learning effective!

Task Analysis may be a long and daunting process at the beginning. However, the more you do it, the better you get at it. In fact, we are practising the steps of Task Analysis as we write this article for you! Practice more and you will soon see how useful it is.

Interested in more tips on teaching to children with special needs? You can read about the importance and features of a good classroom set-up here !

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Special Educator Academy

Free resources, what you need to know about task analysis and why you should use it.

Sharing is caring!

Returning to the Effective Interventions in Applied Behavior Analysis series , I wanted to talk a little about the use of task analysis and why it’s important. For more information on how we use task analyses, check out this post on using shaping and this one on using chaining .

Everyone in special education has probably heard about task analysis. It’s a decidedly unexciting topic in some ways, but it so critical to systematic instruction that we have to address it. In addition, there is a lot of misinformation flying around out there so hopefully this will address just what you need to know about them.

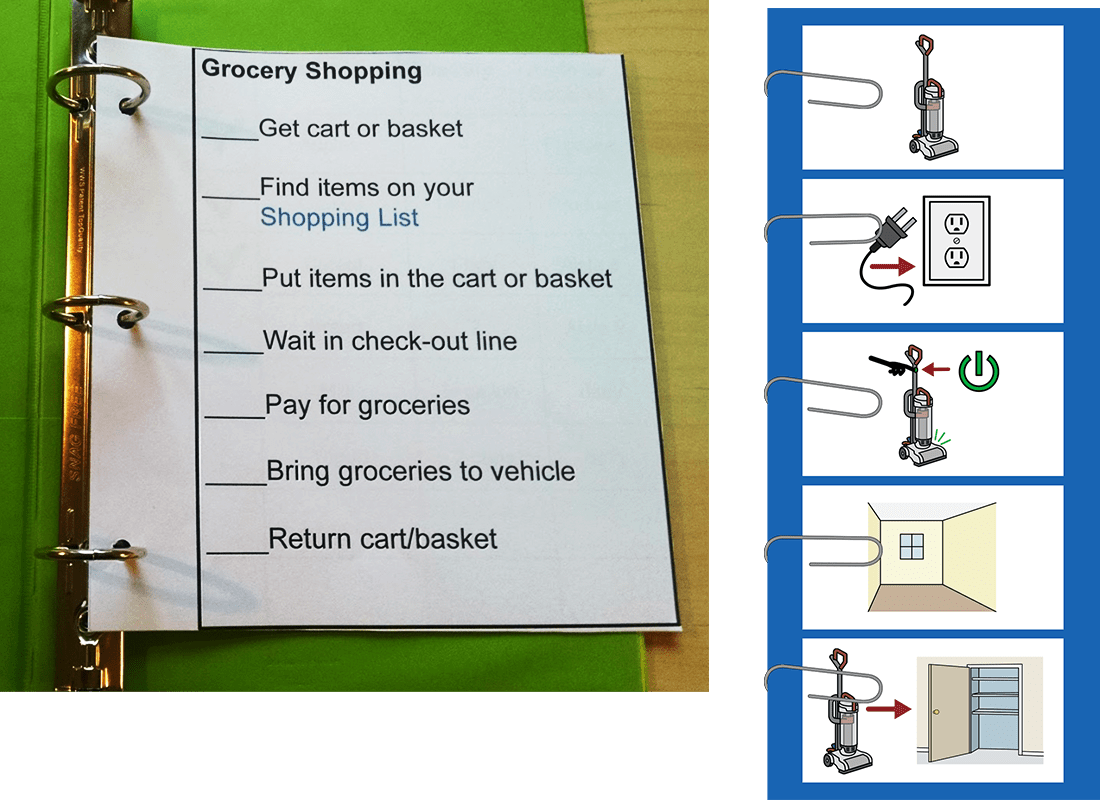

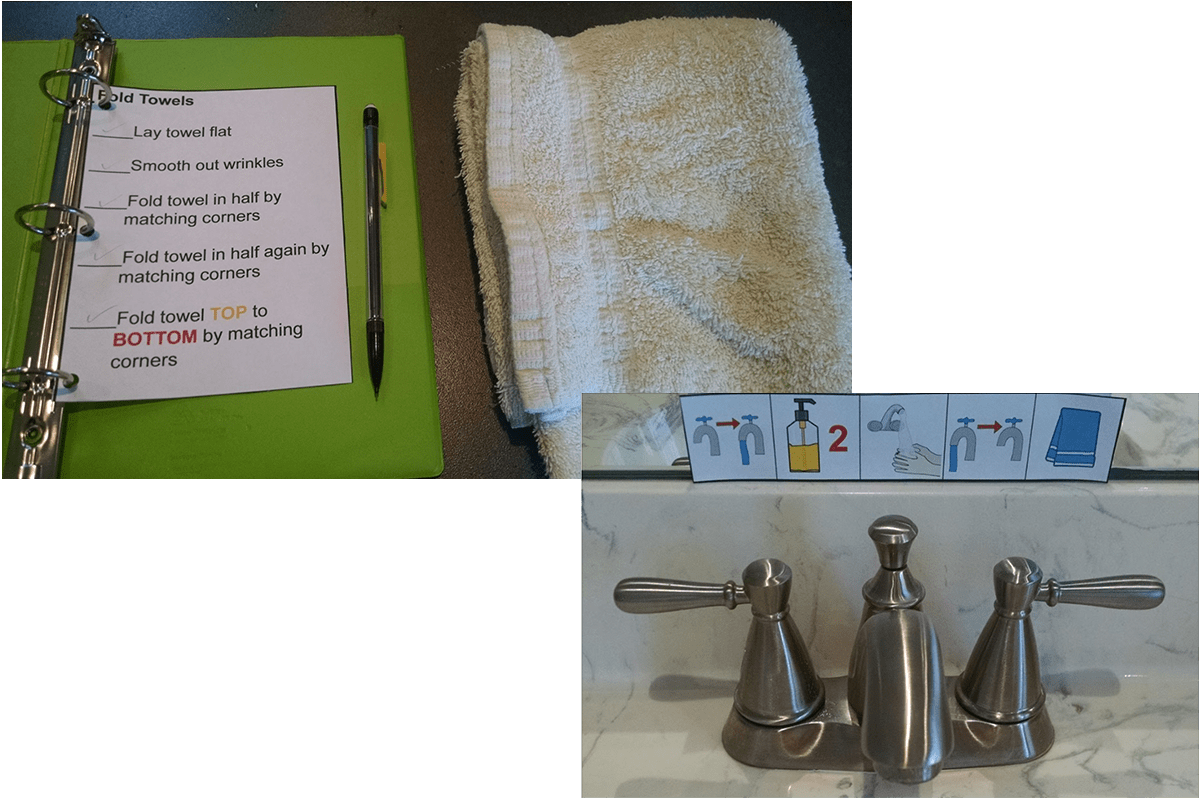

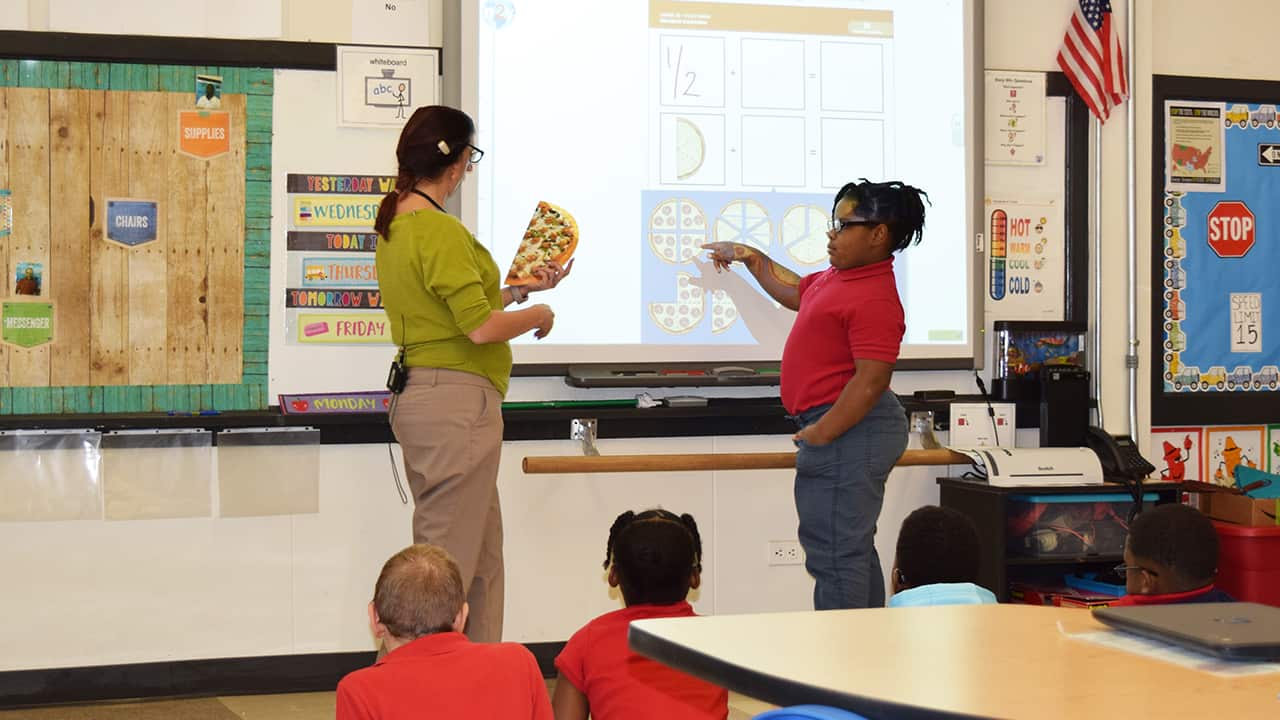

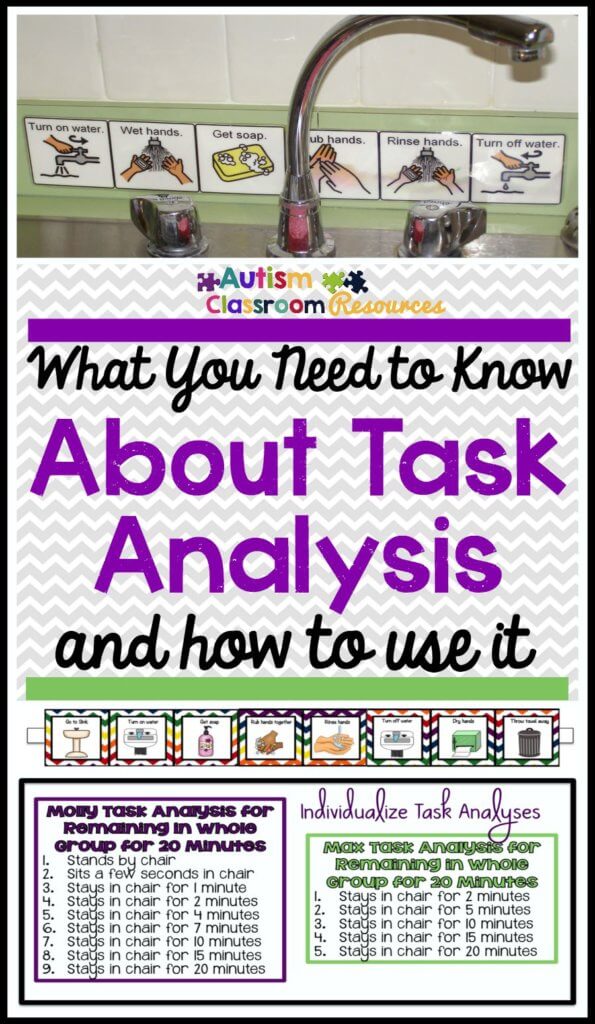

We are told to use them frequently in the classroom to break skills down into smaller components. So, we set up steps, like we do for some of our mini-schedules like the one below for washing hands . Sometimes task analyses have visuals to support them and sometimes they are just written out for the staff.

What is a task analysis?

So if you aren’t familiar with the jargon, what does task analysis mean? The National Professional Development Center found task analysis to be an evidence-based practice, which interests me because I don’t think that behavioral task analysis is actually an intervention. I see the task analysis process as part of other interventions. A task analysis is simply a set of steps that need to be completed to reach a specific goals. There are basically two different ways to break down a skill. You can break it down by the steps in a sequence to complete the task. The hand washing task analysis does that. In this type of task analysis you have to complete one step to be ready for the next. For instance, you have to turn on the water to get your hands wet. This type of task analysis is typically used with chaining which will be the topic of our next post.

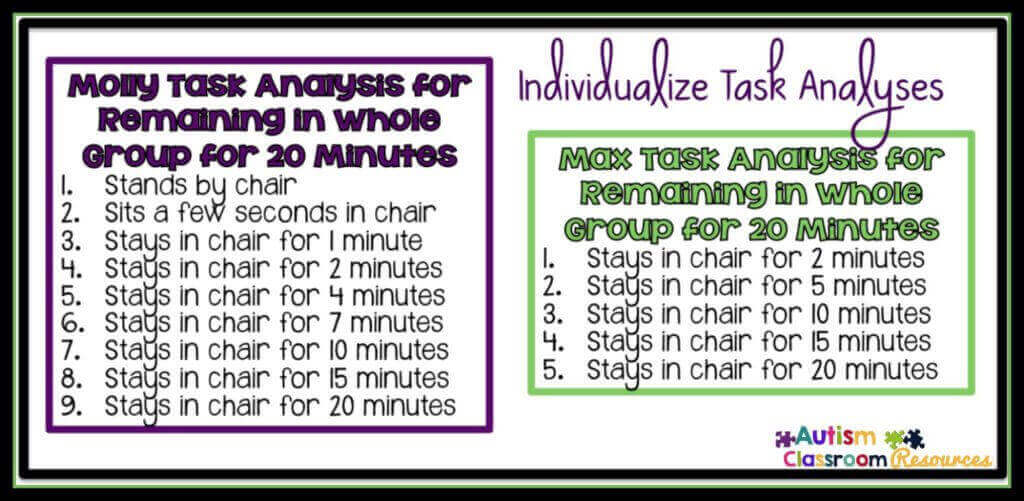

You can also have a task analysis that breaks skills down into smaller chunks, like increasing time. A task analysis for remaining in a group might do that like the examples at the bottom of the picture above. In this type of task analysis, each step replaces the one that comes before it. So, when you sit for 5 minutes, that includes all the steps that come before. This type of task analysis is usually used with shaping, which I will talk about in 2 weeks.

Why Do I Need a Task Analysis?

So if a task analysis is just breaking skills down into smaller skills, you probably do it all the time. Conducting a task analysis isn’t a very time-consuming process.

But, why is using a specific task analysis that is established for a student important? Below are 3 reasons to answer that question.

1. Consistency

In order to assure that everyone is teaching a skill in the same way, breaking it down into the same steps is critical. I am willing to bet that if you ask parents, paraprofessionals or even your significant other how they brush their teeth, you will find some variation in the order of the steps. Your significant other doesn’t put the cap back on the toothpaste. You keep the water running while you brush your teeth while your paraprofessional turns it off to conserve water until she is ready to rinse. My point is that we all have individual differences in the steps of completing simple, everyday tasks. Now, imagine that you are a student who is having difficulty learning to brush his teeth. If you show me one way and prompt me through the steps, and then the parapro shows me another way and prompts me through her steps, and my mom shows me a third way, I’m going to be pretty confused. It’s the beginning of the year and we all need a laugh, so here’s a great video example of why it’s important. Archie and Michael can’t even agree on how to put on shoes and socks. Imagine if they both tried to teach one of our students to put theirs on (no, I would not recommend doing this)–how confused would that student be?

Take Away Point: Writing down a task analysis assures that everyone follows the same steps and teaches the student the same way. Then your instruction is much less confusing and more efficient. 2. Tailor It To The Student

Students need task analyses that are tailored to their needs. I love starting with standard ones, so I don’t have to reinvent the wheel, but then adjusting them to meet the needs of this student. Here’s why the individualization is so important. If your steps are too large for the student, he or she may not make it to the next step and will stall out. For instance, if you are teaching Molly to stay in a group activity for 20 minutes and your task analysis jumps from 5 minutes (that she can currently stay) to 10 minutes, she might never be successful at jumping to 10 minutes and won’t progress. She might do better if we went to 7 minutes next and then 9 minutes. On the other hand, for Max, if we were teaching the same skill and we had him stay in the group for 5 minutes, then 7 minutes and then 9 minutes it might take a very long time when he could have made the jump straight to 10 minutes. Each student is different and we have to figure out how to individualize their steps based on their past data. Is it taking too long to master a step? Step it down to a smaller step. Is he mastering steps really quickly? Make the steps bigger.

3. It is the Basis for Systematic Instruction

Breaking skills down is a critical component of discrete trial programming as well as teaching life skills and other chaining and shaping applications. Discrete trial programs are made up of smaller steps that lead to a larger goal. Learn 1 letter, then 2, then 3? That’s a shaping task analysis. Our research shows us that it’s important to break skills down for students with autism in order to eliminate extraneous variables that might mess up their learning. Teaching systematically is the key to success with any student and especially any student in special education. It’s also key for some of our students to be able to show progress. While it’s not exciting to say that a student has mastered 4 of the 8 steps of tying his shoes, it better than being able to say AGAIN that he can’t tie his shoes–assuming he had no steps mastered earlier in the year. It’s slow progress, but it’s progress.

So, how do you use task analyses in your classroom and why do you think they are important? Are there questions you have about task analyses or teaching strategies that use them? Please share them in the comments and I will try to address them. In the meantime, I’ll be back next Thursday to talk about ways to make your instruction using task analyses more efficient.

- Read more about: Curriculum & Instructional Activities , Effective Interventions in ABA

You might also like...

![task analysis education Summer resources to help survive the end of the year in special education [picture-interactive books with summer themes]](https://autismclassroomresources.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/SUMMER-RESOURCES-ROUNDUP-FEATURE-8528-768x768.jpg)

Summer Resources That Will Help You Survive the End of the Year

How to Effectively and Efficiently Teach Telling Time: Hands-On Learning in Action for Special Education

How To Provide Effective Whole Group Instruction in Special Education?

Valentines Day Activities for Special Education from Preschool to Life Skills-Free Download

Unlock unlimited access to our free resource library.

Welcome to an exclusive collection designed just for you!

Our library is packed with carefully curated printable resources and videos tailored to make your journey as a special educator or homeschooling family smoother and more productive.

COMMENTS

A task analysis is a sequenced list of the subtasks or steps that make up a task (Moyer and Dardig 1978 ). A task analysis can be useful when teaching others how to complete a skill that has multiple steps (e.g., hand washing, zipping a coat). For children who struggle to learn skills through typical classroom instruction, task analyses can be ...

Task analysis is an evidence-based practice that promotes independence and instruction in inclusive settings. Although task analysis has an extensive history in the field of special education, recent research extends the application to both teachers and students, a pro-active approach, and promotes self-monitoring.

Strategies for task analysis in special education. Educational Psychology, 16(2), 155-170. National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders Module: Task Analysis Task Analysis: Overview Page 3 of 3 National Professional Development Center 10/2010 Cooper, J., Heron, T., & Heward, W. (1987). Applied Behavior Analysis. ...

Task analysis is the process of breaking a skill down into smaller, more manageable components. Once a task analysis is complete, it can be used to teach learners with ... Using the learner's Individual Education Plan (IEP)/Individual Family Service Plan (IFSP) goals, teachers/practitioners should identify the skill that the learner needs to

So, putting everything together from steps 1 and 2 and then breaking the subtasks into steps, your final task analysis would look like this; 1. Adding new content to social media. 1.1 Check the editorial calendar. 1.1.1 Navigate to the calendar webpage. 1.1.2 Click today's date.

Many educators find task analysis a useful strategy for teaching students to complete multi-step tasks or skills. This evidence-based practice can be a helpful tool in planning individualized education program (IEP) goals and for instruction as well. It is a proven strategy for targeting academics and a variety of skills: self-help and adaptive, language and communication, and motor.

A task analysis is a fundamental tool for teaching life skills. It is how a specific life skill task will be introduced and taught. The choice of forward or backward chaining will depend on how the task analysis is written. A good task analysis consists of a written list of the discrete steps required to complete a task, such as brushing teeth ...

Task analysis is the complete study and breakdown of how a user successfully completes a task, including all physical and cognitive steps needed. It involves observing an individual to learn the knowledge, thought processes, and ability necessary to achieve a set goal. For example, a website designer may perform a task analysis to see the ...

Task analysis ensures that learning goals and objectives are defined and describes the types of tasks and specific skills/knowledge needed to perform the tasks. It also determines the sequencing of the tasks to be performed, the selection and design of appropriate instructional strategies, types of scaffolding and meaningful assessments and ...

Task analysis is also used in education. It is a model that is applied to classroom tasks to discover which curriculum components are well matched to the capabilities of students with learning disabilities and which task modification might be necessary. It discovers which tasks a person hasn't mastered, and the information processing demands of ...

Verify your email address. Choose a username and password. Upon conducting a task analysis, you determine that Step 7, "Verify your email address," actually consists of multiple subtasks, such as opening up an email app. You decide to move this step later in the process to avoid disrupting the workflow.

The primary purpose of task analysis is to learn things like: How someone accomplishes their goals. The specific steps that someone takes to complete a task. The individual experience and skills that someone brings to completing a task. How the environment affects the person conducting the task. The person's mood and thoughts about the task.