- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

10.3G: Finding Patient Zero and Tracking Diseases

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 11612

The index case is identified in epidemiology studies by tracking down the infected patients to try to determine how the disease originated.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the concept of patient zero or the index case

- The index or primary case is the initial patient in the population of an epidemiological investigation. It may indicate the source of the disease, the possible spread, and which reservoir holds the disease in-between outbreaks.

- In the early years of the AIDS epidemic, there was controversy about a so-called Patient Zero, who was the basis of a complex transmission scenario.

- Other prominent “Patient Zeroes” include Typhoid Mary.

- “Patient Zero” : A term used to refer to the index case in the spread of HIV in North America.

- epidemiology : The branch of a science dealing with the spread and control of diseases, computer viruses, concepts, etc., throughout populations or systems.

The index or primary case is the initial patient in the population of an epidemiological investigation. The index case may indicate the source of the disease, the possible spread, and which reservoir holds the disease in-between outbreaks. The index case is the first patient that indicates the existence of an outbreak. Earlier cases may be found and are labeled primary, secondary, tertiary, etc.

“Patient Zero” was used to refer to the index case in the spread of HIV in North America. The index case is identified in epidemiology studies by tracking down the infected patients to try to determine how the disease originated.

For example, in the early years of the AIDS epidemic there was controversy about a so-called Patient Zero, who was the basis of a complex transmission scenario. This epidemiological study showed how Patient Zero had infected multiple partners with HIV, and they in turn transmitted it to others and rapidly spread the virus to locations all over the world.

The CDC identified Gaëtan Dugas as the first person to bring HIV from Africa to the United States and to introduce it to gay bathhouses. Dugas was a flight attendant who was sexually promiscuous in several North American cities. He was vilified for several years as a “mass spreader” of HIV, and seen as the original source of the HIV epidemic among homosexual men. Later, the study’s methodology and conclusions representation were repudiated.

A 2007 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences claimed that, based on the results of genetic analysis, current North American strains of HIV probably moved from Africa to Haiti and then entered the United States around 1969, probably through a single immigrant. However, the immigrant died in St. Louis, Missouri of complications from AIDS in 1969, and most likely became infected in the 1950s, so there were prior carriers of HIV strains in North America.

In the eboloa outbreak of 2014, the Patient Zero was identified as a two year-old boy in Guinea who died on Dec. 2, 2013 of Ebolavirus during the fruitbat migration. His sister and mother and grandmother then died. Visitors from other villages came to pay their respects and tragically carried the virus back with them. As of November 2014, about 5,500 people had died of Ebolavirus.

Typhoid Mary

Other prominent “Patient Zeroes” include Typhoid Mary. She was the first person in the United States identified as an asymptomatic carrier of the pathogen associated with typhoid fever. She was presumed to have infected some 51 people, three of whom died, over the course of her career as a cook. She was forcibly isolated twice by public health authorities and died after a total of nearly three decades in isolation.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

- Curation and Revision. Provided by : Boundless.com. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SPECIFIC ATTRIBUTION

- cystic fibrosis. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/cystic_fibrosis . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Risk factors for tuberculosis. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk_factors_for_tuberculosis . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Immunodeficiency. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Immunodeficiency . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Urinary tract infection. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Urinary_tract_infection . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cystic fibrosis. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Cystic_fibrosis . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Infectious disease. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Infectious_disease . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Immunosuppression. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Immunosuppression . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Influenza. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Influenza . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chronic granulomatous disease. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Chronic%20granulomatous%20disease . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Influenza Seasonal Risk Areas. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:In...Risk_Areas.svg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Acute infection. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Acute_infection%23Primary_and_secondary . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Window period. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Window_period . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Prodrome. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Prodrome . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Convalescence. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Convalescence . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Incubation period. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Incubation_period . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- clinical latency. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/clinical%20latency . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- viral latency. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/viral%20latency . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- subclinical. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/subclinical . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tuberculosis symptoms. Provided by : Wikimedia. Located at : commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi...s_symptoms.png . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Epidemic. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Epidemic . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Natural reservoir. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural_reservoir . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- pandemic. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/pandemic . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by : Boundless Learning. Located at : www.boundless.com//microbiology/definition/propagated-outbreak . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by : Boundless Learning. Located at : www.boundless.com//microbiology/definition/common-source-outbreak . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Spread of Swine Flu in Europe. Provided by : Wikimedia. Located at : commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi..._in_Europe.svg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Infection. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Infection . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- aerosolized. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/aerosolized . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- vector. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/vector . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- fomite. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/fomite . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Influenza Seasonal Risk Areas. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Influenza_Seasonal_Risk_Areas.svg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tuberculosis symptoms. Provided by : Wikimedia. Located at : commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tuberculosis_symptoms.png . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- OCD handwash. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:OCD_handwash.jpg . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Optimal virulence. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Optimal_virulence . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Virulence. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Virulence . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Epidemiology. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Epidemiology . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ecological competence. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecological_competence . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- ecological competence. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/ecological%20competence . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- virulence. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/virulence . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- zoonose. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/zoonose . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Spread of Swine Flu in Europe. Provided by : Wikimedia. Located at : commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spread_of_Swine_Flu_in_Europe.svg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Spread-Of-The-Black-Death. Provided by : Wikimedia. Located at : commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi...lack-Death.gif . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Biosafety level. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Biosafety_level . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Biological hazards. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Biological_hazards . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- biohazards. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/biohazards . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Biohazard symbol. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bi...ard_symbol.svg . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Biosafety level 4 hazmat suit. Provided by : Wikimedia. Located at : commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi...azmat_suit.jpg . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Mary Mallon. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Mallon . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Index case. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Index_case . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Gau00ebtan Dugas. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ga%C3%ABtan_Dugas . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- epidemiology. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/epidemiology . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Patient Zero. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Patient%20Zero . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Spread-Of-The-Black-Death. Provided by : Wikimedia. Located at : commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spread-Of-The-Black-Death.gif . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Typhoid carrier polluting food - a poster. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ty...-_a_poster.jpg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Publications

- Conferences & Events

- Professional Learning

- Science Standards

- Awards & Competitions

- Daily Do Lesson Plans

- Free Resources

- American Rescue Plan

- For Preservice Teachers

- NCCSTS Case Collection

- Partner Jobs in Education

- Interactive eBooks+

- Digital Catalog

- Regional Product Representatives

- e-Newsletters

- Bestselling Books

- Latest Books

- Popular Book Series

- Prospective Authors

- Web Seminars

- Exhibits & Sponsorship

- Conference Reviewers

- National Conference • Denver 24

- Leaders Institute 2024

- National Conference • New Orleans 24

- Submit a Proposal

- Latest Resources

- Professional Learning Units & Courses

- For Districts

- Online Course Providers

- Schools & Districts

- College Professors & Students

- The Standards

- Teachers and Admin

- eCYBERMISSION

- Toshiba/NSTA ExploraVision

- Junior Science & Humanities Symposium

- Teaching Awards

- Climate Change

- Earth & Space Science

- New Science Teachers

- Early Childhood

- Middle School

- High School

- Postsecondary

- Informal Education

- Journal Articles

- Lesson Plans

- e-newsletters

- Science & Children

- Science Scope

- The Science Teacher

- Journal of College Sci. Teaching

- Connected Science Learning

- NSTA Reports

- Next-Gen Navigator

- Science Update

- Teacher Tip Tuesday

- Trans. Sci. Learning

MyNSTA Community

- My Collections

Patient Zero

The Origins, Risks, and Prevention of Emerging Diseases

By Andrew E. Lyman-Buttler

Share Start a Discussion

Emerging diseases and potential pandemics make the news nearly every year. Students (and everyone else) may wonder where new infectious diseases come from, how scientists assess the risk of a pandemic, and how we might go about preventing one. This case study uses a PowerPoint presentation to explore these questions by focusing on HIV, a pandemic that began as an emerging disease. The storyline progresses backwards through time as scientists attempt to unravel the origins of a new, mysterious plague. Much of the case relies on audio excerpts from an episode produced by Radiolab, an acclaimed radio show that explores a variety of topics in science and culture (www. radiolab.org). Students use graphics, animations, and sound clips presented in the PowerPoint slides to discuss several sets of questions. The case is suitable for a wide range of high school and college introductory biology courses, as well as undergraduate microbiology, ethics, and public health courses.

Download Case

Date Posted

- Explain how the molecular clock can act as a "tape measure" of evolution.

- Describe how emergent diseases can spread into human populations.

- Evaluate the effects of social and cultural factors in the transmission and understanding of disease.

- Explain how the molecular biology of HIV allows it to infect target cells.

- Outline the steps of the HIV reproductive cycle.

- Discuss the mechanisms of viral recombination, and explain its role in the emergence of new diseases.

- Describe one strategy for the prevention of new pandemics.

Virus; AIDS; acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; HIV; human immunodeficiency virus; infectious disease; viral infection; emerging disease; recombination; evolution; molecular clock; pandemic

Subject Headings

EDUCATIONAL LEVEL

High school, Undergraduate lower division

TOPICAL AREAS

Ethics, History of science, Social issues

TYPE/METHODS

Teaching Notes & Answer Key

Teaching notes.

Case teaching notes are protected and access to them is limited to paid subscribed instructors. To become a paid subscriber, purchase a subscription here .

Teaching notes are intended to help teachers select and adopt a case. They typically include a summary of the case, teaching objectives, information about the intended audience, details about how the case may be taught, and a list of references and resources.

Download Notes

Answer Keys are protected and access to them is limited to paid subscribed instructors. To become a paid subscriber, purchase a subscription here .

Download Answer Key

Materials & Media

Supplemental materials.

The supplemental material below may be used with this case study:

You may also like

Web Seminar

Join us on Thursday, June 13, 2024, from 7:00 PM to 8:00 PM ET, to learn about the science and technology of firefighting. Wildfires have become an e...

Join us on Thursday, October 10, 2024, from 7:00 to 8:00 PM ET, for a Science Update web seminar presented by NOAA about climate science and marine sa...

- Brain Development

- Childhood & Adolescence

- Diet & Lifestyle

- Emotions, Stress & Anxiety

- Learning & Memory

- Thinking & Awareness

- Alzheimer's & Dementia

- Childhood Disorders

- Immune System Disorders

- Mental Health

- Neurodegenerative Disorders

- Infectious Disease

- Neurological Disorders A-Z

- Body Systems

- Cells & Circuits

- Genes & Molecules

- The Arts & the Brain

- Law, Economics & Ethics

- Neuroscience in the News

- Supporting Research

- Tech & the Brain

- Animals in Research

- BRAIN Initiative

- Meet the Researcher

- Neuro-technologies

- Tools & Techniques

Core Concepts

- For Educators

- Ask an Expert

- The Brain Facts Book

Patient Zero: What We Learned from H.M.

- Published 16 May 2013

- Author Dwayne Godwin

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Memory is our most prized human treasure. It defines our sense of self, and our ability to navigate the world. It defines our relationships with others – for good or ill – and is so important to survival that our gilled ancestors bear the secret of memory etched in their DNA. If you asked someone over 50 to name the things they most fear about getting older, losing one’s memory would be near the top of that list. There is so much worry over Alzheimer’s disease, the memory thief, that it is easy to forget that our modern understanding of memory is still quite young, less than one, very special lifespan.

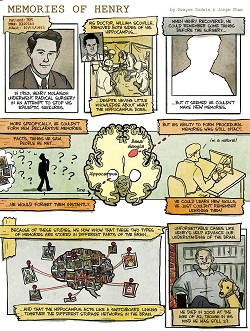

Meet the Patient Zero of memory disorders, H.M.

H.M. was the pseudonym of Henry Molaison, a man who was destined to change the way we think about the brain. Permanent Present Tense: The Unforgettable Life of the Amnesic Patient H.M. is a touching, comprehensive view of his life through the eyes of a researcher who also, in a sense, became part of his family.

The prologue opens with a conversation between the author, Suzanne Corkin, and Molaison in 1992. It reads a bit like a first meeting of two strangers, but then Corkin reveals a jarring truth: this meeting was one of many similar encounters they’d had over 30 years.

By now, if you’re interested in learning and memory you probably know the basics of Henry Molaison’s story. He had epilepsy from an early age that was thought to be acquired through head trauma from a bike accident (though apparently family members also had epilepsy). His surgeon, William B. Scoville (who in a remarkable twist, was a childhood neighbor of Suzanne Corkin) removed Henry’s hippocampus and amygdala in both hemispheres of his brain, in an attempt to control his seizures.

The results of the surgery are legendary. While Henry’s seizures were controlled, he suffered a type of profound anterograde amnesia that prevented him from encoding new memories, but spared certain details of his life leading up to the surgery. Henry would have no memory of those he worked with from day to day, or of new information he might encounter. The book’s title, “Permanent Present Tense”, describes his zen-like existence within the thirty or so seconds around the present moment, which was the limit of Henry’s short term memory.

If this book were a movie or video game, it would be said to be full of “Easter eggs”. There are vignettes and bits of unexpected information that add rich historical context to the state of knowledge in Molaison’s time. These include a digression on the history of neurosurgery, including the gruesome history of lobotomies and the advances brought to the field of neurosurgery by Wilder Penfield. In many ways, H.M.’s legend is a product of a unique scientific lineage – Scoville owed much to Penfield, who in turn trained under Charles Sherrington (he who gave “synapse” to the neuroscience lexicon), and Brenda Milner, who trained under Donald Hebb (who spawned our current notion of activity-dependent plasticity, embodied by the phrase, “cells that fire together wire together”).

The book also reminds us that H.M. was not the first amnesic patient produced through neurosurgical interventions to treat intractable epilepsy, but he was by far the most studied. The book conveys a sense of wonder at the accomplishments of scientists and physicians, charting terra incognita with scalpels, electrical probes and psychological test batteries.

Corkin recounts Henry Molaison’s early life, including key events - like a childhood plane ride that Henry remembered after his surgery - with gentle but thorough prose. Some of these details come from personal conversations with Henry, while others are the result of careful reporting and research.

The book is an accessible master class in learning and memory, with details and key milestones culled from Corkin’s decades of experience as a memory researcher. The details are not so burdensome as to be esoteric, nor so simple as to be trivial. The book gives only a brief overview of the growing field of knowledge about the cellular mechanisms supporting learning and memory (which might be lost on a casual reader), but this is wisely offset by the details of functional anatomy gleaned from Henry and other patients, and a solid explanation of how we encode, store and retrieve memories.

A light, scholarly tone is maintained throughout the book, but it occasionally brushes up against the deeply personal. It’s difficult to hear Henry’s story and not wonder (or actually, worry) about how it was to live as Henry lived, trapped in the moment. Corkin is reassuring on this point:

“When we consider how much of the anxiety and pain of daily life stems from attending to our long-term memories and worrying about and planning for the future, we can appreciate why Henry lived much of his life with little stress…in the simplicity of a world bounded by thirty seconds.”[p. 75].

In other words, the very thing that might cause Henry to fret about his condition was missing. Henry’s tragedy, it seems, is in the mind of the beholder. Another interesting passage concerns Henry’s moods – which were usually happy and content, but could occasionally be sad or uneasy. This is interesting given the removal during his surgery of a major part of his emotional processing circuitry of the brain, called the amygdala.

Henry Molaison’s anterograde amnesia was practically absolute. However, something not often noted is that he would occasionally surprise those studying him by recalling something he should not be able to remember - for example, colored pictures, or details of celebrities he had heard about after his surgery. Corkin reasons that a bit of spared medial temporal lobe may explain these moments.

Henry was amnesic, but he was not without memory. Through careful behavioral testing, various types of memory function could be uncovered, including recognition memory for having seen images that could persist for months. Corkin suggests that this “memory for the familiar” may have been of some comfort as he navigated what would have otherwise been a confusing experience of reality. New technologies like computers, for example, could be incorporated into his view of the world and did not appear to be jarring to him as would be expected if his capacity for recognizing the familiar did not exist.

Another key discovery from Henry was the finding that he had retained the ability to form non-declarative memories, which took the form of improvement in motor skills. This separate memory system depended on regions of the basal ganglia and motor cortex, which were spared in Henry’s surgery. Testing could improve his performance in the motor task, but his impaired declarative memory system didn’t allow him to remember taking the tests – he could be surprised by his own improvement. Along with his simple recognition memory, motor memory helped smooth challenges Henry faced as he aged, such as learning to use a walker.

Other forms of memory in which Henry showed improvement were in picture completion, where he was able to identify a picture from fragments over a series of sessions, and priming, where previously presented words could prime recognition on presenting fragments of the words. And while Henry is best known for anterograde amnesia, and is sometimes portrayed as having intact memories of things and events before the surgery, he also possessed a partial retrograde amnesia, especially for autobiographical events that happened two years before the surgery - he had only fragmented memories from before that two year window.

Did Henry Molaison have a sense of self? While his was not a fully integrated personality, he possessed “beliefs, desires and values” and seemed capable of a full set of emotions – even without his amygdalae. His view of his own appearance did not seem to cause him distress, even though his estimate of his own age could vary widely. His impairment prevented him from formulating future plans. His basic decency shines through the narrative.

Henry died in 2008 at the age of 82. His brain was scanned postmortem, and extracted for further anatomical analysis . Coming full circle from one of his remaining childhood memories of his first ride, Corkin describes her last wistful goodbye to Henry’s brain as it was conveyed by his final plane ride back to the west coast, where his brain was sliced up into thin sections for new studies. Perhaps the most documented and studied research subject in neuroscience continues to provide vast amounts of data to further our knowledge.

Henry once remarked about his testing, of which he never seemed to become bored since he carried little from one session to the next: “It’s a funny thing – you just live and learn.” He then went on to provide a poignant turn in the familiar phrase: “I’m living, and you’re learning.”

Though he’s no longer living, we’re still learning from Henry.

Permanent Present Tense is a rare look at an amazing mind, whose study formed the basis of our modern science of memory.

Corkin, Suzanne. Permanent Present Tense: The Unforgettable Life of the Amnesic Patient, H.M. (Basic Books) May 14, 2013 | ISBN-10: 0465031595 | ISBN-13: 978-0465031597

Update 6/7/2013: NPR interview with Suzanne Corkin on H.M .

Update 1/30/2014: Report on anatomical and histological findings from Henry Molaison: Postmortem examination of patient H.M.’s brain based on histological sectioning and digital 3D reconstruction . J Annese, NM Schenker-Ahmed, H Bartsch, P Maechler, C Sheh, N Thomas, J Kayano, A Ghatan, N Bresler, MP Frosch, R Klaming & S Corkin. Nature Communications 5, Article number: 3122

Update 7/6/2016: Statement on informed consent transmitted to me by Suzanne Corkin

About the Author

Dwayne Godwin

Dwayne Godwin is a Professor of Neurobiology and Neurology at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine, where he studies epilepsy, sensory processing, withdrawal and PTSD. He coauthors a comic strip on brain topics for Scientific American Mind .

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In Learning & Memory

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org

Ask An Expert

Ask a neuroscientist your questions about the brain.

Submit a Question

BrainFacts Book

Download a copy of the newest edition of the book, Brain Facts: A Primer on the Brain and Nervous System.

A beginner's guide to the brain and nervous system.

SUPPORTING PARTNERS

- Privacy Policy

- Accessibility Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Manage Cookies

Some pages on this website provide links that require Adobe Reader to view.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 26 October 2016

HIV’s Patient Zero exonerated

- Sara Reardon

Nature ( 2016 ) Cite this article

1883 Accesses

447 Altmetric

Metrics details

This article has been updated

A study clarifies when HIV entered the United States and dispels the myth that one man instigated the AIDS epidemic in North America.

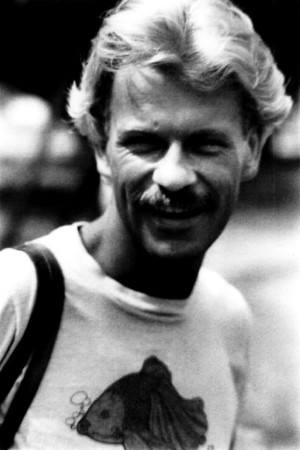

In 1982, sociologist William Darrow and his colleagues at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) travelled from Georgia to California to investigate an explosion in cases of Kaposi’s sarcoma, a type of skin cancer, among gay men. Darrow suspected that the cancer-causing agent — later shown to be a complication of HIV infection — was sexually transmitted, but lacked proof. His breakthrough came one day in April when three men from three different counties told Darrow that they had had sex with the same person: a French Canadian airline steward named Gaétan Dugas.

CDC researchers tracked down Dugas in New York City, where he was being treated for Kaposi’s sarcoma. With his cooperation, the scientists definitively linked HIV and sexual activity 1 . They referred to Dugas as 'Patient Zero' in their study, and because of a misunderstanding by journalists and the public, the flight attendant became known as the person who brought HIV to the United States. Dugas and his family were vilified for years 2 .

But an analysis of HIV using decades-old blood serum samples exonerates the French Canadian, who died in 1984. The paper 3 , published on 26 October in Nature , shows that the virus had been circulating in North America since at least 1970, and that the disease arrived on the continent through the Caribbean from Africa .

Richard McKay, a historian at the University of Cambridge, UK, and study co-author, says that scientists have always questioned the idea of a single Patient Zero, because some evidence suggested that the virus entered North America several times.

A team led by McKay and evolutionary biologist Michael Worobey at the University of Arizona in Tucson wanted a clearer picture of HIV’s arrival. So the team collected more than 2,000 serum samples that health clinics had collected from gay men in 1978 and 1979 while testing for hepatitis B. The researchers found enough genetic traces of HIV that they could sequence in three samples from San Francisco and five from New York City.

Earlier arrival

When scientists examined those genetic sequences in detail, they found them to be similar to HIV strains present in the Caribbean, particularly Haiti, in the early 1970s. However, the strains were different from one another, suggesting the virus had already been circulating and mutating in San Francisco and New York City since about 1970.

Furthermore, Worobey’s analysis of Dugas’ own blood showed that the HIV strain that killed him didn’t match the others. “There's just no indication that he was anything other than one of many people who were already infected before the disease was noticed,” Worobey says.

The latest study shows how easy it is to jump to conclusions about a virus that does not immediately cause disease, says Beatrice Hahn, a microbiologist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Researchers in the 1980s had not yet discovered HIV’s long incubation period: it can stay in the body for ten years on average before making a person ill. The many symptoms associated with AIDS also made it difficult to diagnose.

A devastating understanding

“The history of diseases has always been, in part, that someone needs to be blamed,” says Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Disease in Bethesda, Maryland. In the 1980s, it was particularly easy for the public to direct their anger toward a 'promiscuous' gay man .

Dugas was key to researchers’ efforts to understand HIV , and “there is something more than a little wrong with what has happened in terms of the popular imagination”, Worobey says. Randy Shilts' 1987 book, And the Band Played On , which suggested that the flight attendant deliberately spread the disease, was particularly damning.

Dugas did still spread the disease, says a physician who treated him for Kaposi's sarcoma. He continued to have unprotected sex until he was too ill, citing the lack of hard evidence that he could spread the ”gay cancer”, says Friedman-Kien.

Many gay men at the time resisted the idea that unprotected sex spread HIV, says the dermatologist. “It was a very difficult thing — because they had fought so much for sexual freedom and for recognition and acceptance — to be told that every gay man is potentially a carrier of this terrible disease.”

The study is a lesson in how scientifically and ethically difficult it can be to identify a 'patient zero', says McKay. Dugas’ story emphasizes that HIV was “not just a retrovirus undergoing change in some timeless void”, he adds. The quest for scientific understanding of the disease had a very real impact on the man and his family.

Change history

27 october 2016.

The story originally said that Dugas was unlikely to be sexually active as a teenager, and attributed this to McKay. In fact, McKay did not say this. The story has been changed to reflect this.

Auerbach, D. M., Darrow, W. W., Jaffe, H. W. & Curran, J. W. Am. J. Med. 76 , 487–492 (1984).

Article CAS Google Scholar

McKay, R. Bull. Hist. Med. 88 , 161–194 (2014).

Article Google Scholar

Worobey, M. et al. Nature http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature19827 (2016).

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Additional information

Read the related Editorial: ' How researchers cleared the name of HIV Patient Zero '

Related audio

When hiv arrived in north america, related links, related links in nature research.

How researchers cleared the name of HIV Patient Zero 2016-Oct-26

South Africa ushers in a new era for HIV 2016-Jul-13

Homophobia and HIV research: Under siege 2014-May-14

HIV's history traced 2003-May-20

Related external links

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Reardon, S. HIV’s Patient Zero exonerated. Nature (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2016.20877

Download citation

Published : 26 October 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2016.20877

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Hist Cienc Saude Manguinhos

- v.30(Suppl 1); 2023

- PMC10546979

Language: English | Spanish

Creating Peru’s patient zero: pandemic narratives through traditional and social media

Creando el paciente cero de perú: narrativas sobre la pandemia a través de los medios de comunicación tradicionales y sociales, alejandra ruiz-león.

i Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta GA , USA, ude.hcetag@lrA PhD Candidate, Georgia Institute of Technology. Atlanta – GA – USA [email protected]

During the covid-19 pandemic, authorities, journalists, and the public used the term patient zero to refer to the first diagnosed patient. However, experts describe the term as imprecise because it equates the first infected patient with the first identified one. Although the term’s inaccuracy, patients zero became relevant actors and sources of information during the pandemic. This was the case with the Peruvian patient zero, who had public media participation and opened his Instagram to establish a communication channel with the public. Despite knowing the term’s inaccuracy, he felt responsible for the audience and sought to give his testimony. The Peruvian case shows how patients zero respond to the public interest and establish their agency through traditional and social media.

El coronavirus hizo que autoridades, periodistas y público designaran “paciente cero” al primer diagnosticado, aunque los especialistas calificaran al término como impreciso por equiparar el primer paciente infectado con el primero identificado. A pesar de esa inexactitud, pacientes cero se tornaron actores y fuentes de información relevante durante la pandemia. Fue el caso del paciente cero peruano, que participó en los medios de comunicación y abrió su Instagram para establecer un canal con el público. Conociendo la inexactitud del término, asimismo trató de dar su testimonio para aclarar la audiencia. El caso peruano muestra cómo pacientes cero responden al interés público y establecen sus acciones mediante los medios tradicionales y sociales.

On May 31, 2021, Peruvian President Francisco Sagasti announced the results of an independent study conducted by Peruvian scientists and health authorities that revealed the confirmed number of covid-19 deaths in the country since the beginning of the pandemic (Chávez, 31 May 2021). The new death toll shown in the study placed Peru at the top of the list of the most affected countries per capita, with the loss of more than 184,000 Peruvians. The report became news, both internationally and domestically. For Peruvians, it confirmed the widespread suspicion that the actual number of deaths exceeded the official data provided by the government (Perú es…, 1 June 2021). For international observers, the report prompted questions as to whether their reports and official data accurately captured the impact of the pandemic.

New information, such as the updated official death toll in Peru, calls for an analysis of the successes and failures in responses to the pandemic, which does not yet have an end date. As Marco Cueto (2022) reflects on Salud en emergencia, historical research of the events that happened during the covid-19 pandemic allows us to analyze the social process that shaped the pandemic, such as the establishment of insufficient policies or how the authorities feed the audiences with false promises or incomplete information. One area of interest in the history of medicine is how the first days of the pandemic developed, which scholars see as critical to understanding the pandemic’s progression. This paper focuses on the patient zero figure during the early days of covid-19 pandemic in Peru and how media and authorities used the term to identify the country’s first person who tested positive for coronavirus.

The pandemic in Peru technically started on the morning of March 6, 2020, when President Martín Vizcarra announced during a televised media conference that “the first case of coronavirus infection has been confirmed” (Presidente…, 6 mar. 2020). Other countries in the region, such as Chile and Argentina, had already reported coronavirus cases, making the identification of the first Peruvian patient only a matter of time and an expected sign to declare the onset of the pandemic. During the first days, the term patient zero was broadly used by politicians, journalists, experts, and even the first patient of covid-19, to refer to the first coronavirus case in the country. TV Perú, Peruvian public television, used the term patient zero from the first reports of the patient, mentioning that “patient zero revealed that he sought dismissal in the clinic up to three times” (Covid-19…, 9 Mar. 2020). Peruvian television announced the patient’s first interviews as “the testimony of the patient zero” (Día D, 9 Mar. 2020), and authorities such as the minister of Health used the term when announcing the patient’s discharge (Ministra…, 16 Mar. 2020).

The Peruvian case shows how covid-19 patients zero openly told their stories as the first persons identified as being infected with the novel coronavirus. Calling the first patient by the term “patient zero” preserved the person’s identity while informing the population of the start of the pandemic. Legal and moral practices prevented authorities and the media from revealing personal information that could identify the patients. As this paper will address, however, patients zero did not always remain anonymous and, in some cases, they participated in interviews, public health campaigns or even gained momentary fame.

The use of the term patient zero in disease outbreaks continues, despite medical experts stressing its lack of scientific accuracy and negative implications ( Giesecke, 2014 ; McKay, 1 Apr. 2020). Historians of medicine have studied how societal aspects shape medical events, stressing that social interpretations influence our understanding of a disease beyond scientific information and medical expertise. This paper builds on previous research on patients zero in diseases like aids, flu, and Ebola, among others ( Coltart et al., 2017 ; Marineli et al., 2013 ; McKay, 2017 ). When looking back to the actions that shaped the pandemic, historians should look for new ways patients establish their agency. Historians have previously used patients’ diaries to understand their perspectives, even if personal diaries can be considered subjective ( Condrau, 2007 ). Scholars should now look into social media as a platform that patients use to tell their side of the story and to control their narrative. Unlike traditional media, social media offers patients direct communication with the general public and provides a more direct connection with both positive and negative outcomes.

This research explores how social media has given patients zero new means for establishing their agency in situations where they have been under intense public scrutiny. Disciplines such as science communication, history of medicine, and ethics have studied the use of social media for patient advocacy (Househ, Borycki, Kushniruk, 2014). Social and traditional media became outlets for patients “to comfort the public with the hope that the virus would be controlled” ( Pascual Soler, 2021 , p.71). In the case of the Peruvian coronavirus patient zero, social media served as the primary platform to share information that was unique to that person but comforted the public when scientific certainty was scarce. However, for several reasons, social media has not always been the primary communication for patients zero in previous outbreaks. For example, in the case of aids, the patient zero did not participate in interviews as the media only knew his name after his death . In the case of the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the patient was a minor and, in earlier times, social media did not exist, as in the case of typhoid fever.

The concept of patient zero is used because it holds enough information for the audience to understand the relevance of this person’s testimony and potentially respond to questions that experts cannot answer. For example, the Peruvian patient zero explains how he knew he was possibly not the first Peruvian with coronavirus but rather the first one to be identified (Día D, 12 Apr. 2020). If he was not the first patient, there were already other patients, which indicates that the government’s actions were insufficient to contain the virus entry. The scientific research later confirmed the denominated patient zero’s suspicion that he was not the first person in Peru to be infected with the virus. Phylogenetic and epidemiological research made with samples from the first months of the pandemic shows multiple virus entries into Peru, confirming that not all cases came from patient zero ( Juscamayta-López et al., 2021 ; Padilla-Rojas et al., 6 Sep. 2020). Authorities and experts discussed this scenario; however, the ideas of the initial date of the pandemic and the existence of one introductory case prevailed.

The idea of a patient zero still holds meaning for society, making it appealing to provide information when scientific research cannot provide facts. The new ways that society has used the concept of patient zero during the covid-19 pandemic make this a relevant topic for historians of medicine and public health officials who need to assess the dimension of risk in using this term for pandemic communication. Focusing on the Peruvian case, we see how social narratives about the pandemic circulated on both traditional and social media. The latter offered patients zero new platforms to advocate for themselves and for audiences to acquire medical information beyond those provided by authorities and experts.

This research builds on different sources to understand the role of patients zero during the onset of the pandemic and how they established their agency after becoming a subject of interest. To do this, the essay draws on academic literature dealing with the social construction of the term patient zero and its role in previous outbreaks, as well as the work of historians of science on patient zero. The analysis includes Peruvian and international media, examining how newspapers and online information reflected the identification of the first case of coronavirus in different countries. Additionally, the essay analyzes the public communication of the “Peruvian patient zero,” including media appearances and social media publications, to show how narratives of heroism and national strength prevailed in journalists’ and authorities’ statements and how the patient’s agency was established through traditional and social media. Overall, the research analyzes the use of the term patient zero during the beginning of the covid-19 pandemic in Peru. It also shows how the image of the first patient was shaped by governmental authority’s statements, media coverage, and the patient’s agency established through traditional and social media.

The concept of patient zero

When a part of the general public uses a technical term, they may give it a new meaning, different from what experts use within their communities. Medical and scientific groups use technical terms to share information within their professional environments, and these terms relay specific information. However, expert communities cannot prevent technical jargon from being used in other ways by non-experts. The general public can use and adapt these terms. During the pandemic, technical words such as quarantine, inoculation, or contact tracing ceased to be used exclusively by professional groups as society included them as part of their daily language.

Communities also adopt new terms to describe medical situations, even when these terms do not have scientific meanings or medical experts do not use them. This was the case during the covid-19 pandemic with the term patient zero, which authorities and media used, while scientists avoided it because it is inaccurate. Experts stressed that during previous outbreaks, the term patient zero created adverse outcomes such as associating a disease with moral responsibilities or with minority groups (McKay, 1 Apr. 2020). During the covid-19 pandemic, journalists and laypeople continued to use the term because it held meaning for society and announced the onset of the pandemic. Understanding the term’s history and how it serves society is essential since the media and the public will likely use it in future disease outbreaks.

The term patient zero refers to the first person identified as a patient with a disease. The historian of medicine Richard McKay explains how the term is “often used interchangeably for three different scenarios: the first case noticed, the first case here, and the first case ever” (McKay, 1 Apr. 2020). For the scope of this paper, we will focus on the term’s first two interpretations. In Peru, media and authorities used the term patient zero to refer to the first person infected with the virus and the first Peruvian case. The two interpretations differ from “the first case ever,” meaning the first case in Wuhan, China, referring to the virus’s origin.

Epidemiologists discouraged media outlets from using the term patient zero because of its inaccuracy. Besides the different meanings of the term, another limitation is that the term does not differentiate between the first infected patient, the first symptomatic patient, and the first person identified as a patient. Moreover, the term gives the illusion that it is always possible to identify the first infected person when there might not be enough evidence to confirm the original patient contracting a disease. Instead, epidemiologists advocate for the terms “index case” and “primary case.” According to A Dictionary of Epidemiology , an index case refers to “the first case in a family or other defined group to come to the attention of the investigator” (Porta, 2016a, p.146). The primary case refers to “the individual who introduces the disease into the family or group under study. Not necessarily the first diagnosed case in a family or group” (Porta, 2016b, p.225).

The term patient zero is less precise than the terms index case and primary case because it ignores the possibility that the patient that introduced a disease into a group might not be the one identified by authorities. This is one reason the term patient zero is disadvantageous for technical communication. For the community, it provides a sense of security about the starting date of the pandemic and the efficiency of case surveillance, even when this information is undetermined. The terms index case and primary case acknowledge that the first captured patient might not be the first infected patient, which is a probable scenario in an outbreak. The correct term to describe the Peruvian patient zero should have been index case because investigators identified him as the first.

The covid-19 particularities make the term patient zero more complex because patients could be symptomatic or asymptomatic. When using the term patient zero, there is an interest in differentiating between sick and healthy people, referred to as the process of becoming a patient ( Porter, 1985 ). Covid-19 asymptomatic patients do not show symptoms and are only considered sick with a positive test. Moreover, the notion of asymptomatic patients was uncommon at the pandemic’s beginnings (Schuetz et al., 17 Dec. 2020). Hospitals tested patients only after they developed symptoms or revealed a history of travel to a country with communal virus transmission (WHO, 2020). The patients zero who sought diagnosis had to contact the authorities because the progression of the disease was unknown, and the focus was on tracing the patient’s close contacts.

The history of the term patient zero helps us understand the flaws of this concept and why its use during the pandemic was problematic. In the book Patient zero and the making of the AIDS epidemic , McKay (2017 , p.28) details the creation of the concept in 1980, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) monitored the first cases of aids in the United States. The CDC used the label “Patient O,” where the O referred to a patient “Out of California,” with no zero, as it would later be known. The term patient zero was not born to signal the first patient but rather the location of one patient from a cluster of cases in California. McKay explains how the media used the concept to create curiosity, not for scientific objectives. The journalist Randy Shilts was one of those responsible for amplifying this concept by promoting the image of hunting for the person that supposedly brought the virus to the United States. Shilts embarked on a professional and personal search, revealing the identity of Gaëtan Dugas, who became wrongly known as the patient zero in the North American aids epidemic (McKay, 2017). The term gained additional connotations through the years; as McKay (1 Apr. 2020) expressed, the term denotes a sense of urgency and resembles military terms such as “hour zero” or “ground zero.”

Society gives meanings to specific terms, such as patient zero, in complex situations like epidemics. Paula Treichler coined the term “epidemics of significations” to illustrate how in medical situations, society awards meanings to terms that influence societal understanding and approaches to medical conditions ( McKay, 2017 , p.5; Treichler, 1987 ). These concepts result from co-production, where scientists, doctors, journalists, and audiences create and use new words with purposes beyond the expert’s use. For example, the term patient zero originated to designate the location of a group of patients. However, it changed its meaning when the “o” was misinterpreted for “0,” which led to the interest in identifying aids’s primary case. Then the social meaning of the concept became more representative than its historical meaning.

Although the term patient zero started during the aids epidemic in North America, this was not the first time scientists and media focused on the first known cases of a disease. The most well-known patient zero case, or correctly, an index case, was Mary Mallon, known as Typhoid Mary, whom doctors identified as a super spreader of typhoid fever. In Mallon’s case, the term healthy carrier added a medical component and a moral one. She was stigmatized and portrayed as irresponsible for making others sick, as well as for being a woman immigrant who could not understand the scientific rationale behind the measures taken to seclude her from society ( Marineli et al., 2013 ). There has also been an interest in identifying the patient zero in more recent epidemics, as is the case of the Ebola outbreak in 2014-2016, where scientists used the patient’s DNA sequences to trace the primary case, Emile Ouamouno, a two-year-old from Guinea ( Coltart et al., 2017 ).

The media and communications from experts also affect how the public perceives patients zero. In Peru, doctors described the first aids patients as irresponsible, shaping the social understanding of the disease and impacting the access to diagnosis for fear of being identified ( Lan Ninamango, 2021 ). Similarly, during the cholera epidemic of the 1990s, public health interventions focused on personal responsibility instead of the lack of infrastructure that promoted the spread of the disease ( Cueto, 1997 ). In these cases, the public saw the patients’ responsibility as crucial for their survival, and doctors and authorities supported and spread these narratives.

Even when the term patient zero gave a sense of security and control, many historians and public health experts indicated the risks of misusing this term, calling it toxic and inappropriate, based on the stigma and shame experienced by patients in previous pandemics (McKay, 1 Apr. 2020). However, this did not limit the use of the term during the covid-19 pandemic. Moreover, people might continue to use the term in future epidemics. Understanding the past and future use of the term patient zero is essential, particularly in how these patients establish their agency when interacting with broader audiences.

Coronavirus patients zero in the news

During the last weeks of 2019, news outlets worldwide began to cover the appearance of a new respiratory virus in China. The virus became a global event when virtually every country detected coronavirus patients inside their territories. Authorities and media channels had the opportunity to prepare for the virus’s arrival by coordinating public health strategies and communicating prevention narratives. During the first months of 2020, countries such as Peru took measures to delay the virus’s circulation and contain the first cases to avoid the communal spread of the virus (Perú, Jan. 2020). Many countries followed a zero-case approach at the beginning of the pandemic to limit the spread and reach zero cases, a strategy that only a handful of countries continued in 2022 (Marshall, 3 May 2022).

There was a growing interest in identifying the patient zero from each location or country as the coronavirus spread worldwide. The coverage of patient zero in different countries shared a common interest in showing the patient’s experiences. The risk of these approaches was prioritizing the patient’s capacity to follow the rules instead of the lack of medical infrastructure that influenced the patient’s outcomes. The interviews with patients zero responded to social narratives of national pride, medical advantages, and other ideas promoted by governments and authorities. A common discourse was to interpret the pandemic as a war against an invisible enemy, where the patients zero became part of the heroes that helped us survive the pandemic with their work and example ( Pascual Soler, 2021 ).

In the case of the first patient ever, we see how the lack of a person identified as an index patient fueled critics of the Chinese government and led to disinformation, misinformation, and racist claims toward Asians (Wang, Santos, 2022). The lack of information regarding China’s patient zero contributed to the aura of conspiracy and uncertainty regarding the pandemic’s origins (Worobey, 3 Dec. 2021). While the first coronavirus patient ever remained unknown, other countries rushed to identify their first patients.

Two cases of patients zero with several media appearances were the denominated Italian and New York patients zero. The first identified coronavirus case in Italy was Mattia Maestri, a 38 years-old man from the country’s northern region. Media reports described him as a middle-class working person, representative of Italians, who had not traveled abroad but was infected and spent some time in hospital. He described himself as a messenger of positivism and social awareness with a moral duty to his community. He later became a symbol of national resilience, participating in public health campaigns, raising funds for patients and being described as exemplary (Politi, 16 Sep. 2022). In New York, the media coverage of patient zero replicated similar narratives of heroism and personal responsibilities. The patient zero from New York gave an interview accompanied by his family. The media described him as a working person, dedicated to his family, who lived in the New York suburbs, and as someone who had no contact with foreign visitors. In the interview, the media showed his family bonds as crucial for his recovery (Brody, 5 Mar. 2021). Like the Italian patient zero, the press portrayed the New York patient as an exemplary citizen concerned for others’ health and committed to controlling the pandemic.

However, not all media portrayals of patients zero were positive. One of the most notable case was a Vietnamese socialite, referred to as fashion’s patient zero (Friedman, 11 Mar. 2020). In March 2020, she participated in European fashion shows before knowing she was infected. The audience saw her as irresponsible for spreading the virus, and she received attacks on her social media, forcing her to close her channel (#BAZAARTalks, 31 May 2020). These attacks referred to her wealthy status and Asian identity, which were part of a larger trend of racism towards Asians during the pandemic.

In Peru, the media also reported xenophobic attacks against Asian communities. Ragas and Palma note how these communities were not subject to violent attacks in Peru, as was seen in the United States. In Peru, xenophobic attacks were limited to messages replicated by small radical groups rather than the general population or authorities. According to Ragas and Palma (2022), the collaboration of the Chinese government in controlling the pandemic was seen in Peru as positive and may have helped to limit the attacks on Asian communities.

Social aspects influenced how the media portrayed patient zero. Gender, age, ethnicity, and social status of the patients were frequently included in their media participation and influenced how audiences perceived patients zero. McKay explains that minorities are at risk of being portrayed as irresponsible because they are “judged to have disobeyed community standards” (McKay, 1 Apr. 2020). Even when the identity of patients zero was unknown, as in China, there was still an interest in identifying them to gain more knowledge on how the pandemic began (Calisher et al., 7 Mar. 2020).

Peruvian media covered the first covid-19 cases outside China with a sense of urgency, reporting on how health agencies in Europe and South America had identified positive cases and how Peru was preparing for the virus’s arrival (El Coronavirus…, 4 Mar. 2020). Time was running out before confirming the first case in Peru, and the hunt for patient zero had begun. National newspapers such as La Republica featured headlines such as “Coronavirus every time closer to Peru” (El Coronavirus..., 4 Mar. 2020). The government also made several media appearances, with the minister of Health announcing the government’s covid-19 containment plan (Elizabeth…, 3 Mar. 2020).

Finding the Peruvian patient zero

The news from international patients zero created an environment of expectation in Peru, where people saw the arrival of the coronavirus as inevitable. The government responded with the publication of its covid-19 protocols, and the media followed with information about the virus. The public expected the announcement of the first patient; however, nobody could predict the virus’s impact in the following months. The public interest in patient zero focused on his/her correct detection and the development of his/her infection since the public would measure the virus’s severity based on this, even when each person responds differently to the virus.

Identifying the first covid-19 patient in Peru changed the government’s response to the virus. As the historian Jorge Lossio details, the government’s first strategy was to prevent the entrance of the virus. To pursue this goal, they purchased covid-19 tests and screened passengers traveling to Peru for coronavirus symptoms, such as fever and coughing. After the first case, the government’s response redirected to “prevent exponential spread, inform the population about the coronavirus and improve hospital infrastructure” (Lossio, 2021, p.582). In the following days, the president announced strict measures such as closing schools, suspending flights, and a national lockdown that extended over a period of a hundred days.

The government’s rapid response and advancements in health infrastructure initially gave the public hope that the country could control the pandemic. Before the pandemic, experts recognized Peru for its economic growth and progress on global development goals, such as universal health coverage. These improvements were insufficient to overcome the institutional fragmentation of the Peruvian health system, and disparities in access to healthcare became more pronounced during the pandemic ( Gianella et al., 2020 ). As the pandemic progressed, the healthcare system collapsed, making it impossible to provide adequate treatment for all patients, resulting in a high number of deaths (Gianella, Gideon, Romero, 3 Apr. 2021).

The first news of potential cases was in January 2020, when Peruvian media reported two suspicious cases of coronavirus involving Chinese visitors (Ministra…, 27 Ene. 2020). Only a few countries had identified coronavirus cases at that time, which limited the information on procedures and testing methods. First, three visitors from Wuhan and their Peruvian translator presented symptoms associated with the coronavirus, but public health officials and doctors reported that they did not have covid-19. The news did not specify if they tested explicitly for the novel coronavirus. Two other Chinese tourists presented symptoms while visiting Cusco, but they did not come from Wuhan, which was one of the required characteristics to signal someone as a covid-19 patient at the time. The news mentioned a negative laboratory test but did not specify if sensitive coronavirus tests were then available (Cusco..., 30 Ene. 2020). More than two years after doctors identified these potential index cases, it is impossible to confirm whether these visitors were positive for the coronavirus. However, this shows how limited the detection protocols were in January 2020. During that time, Latin American authorities and the public did not see the virus as an immediate threat. They saw news from China as distant, which was reflected in the lack of follow-up in media coverage of these patients. However, from January to March, when the president announced the first confirmed Peruvian covid-19 case, the situation, and public perception of it, had changed dramatically since neighboring countries had already identified covid-19 patients and because cases were growing worldwide.

Peruvians woke up on March 6, 2020, to a presidential emergency message. Martin Vizcarra, president of Peru, announced that the National Institute of Health (Instituto Nacional de Salud, INS) identified the first coronavirus patient in Peru, and health authorities followed the mandated protocols. Vizcarra described patient zero as “a young man of 25 years old that had a history of travel to Europe” (Presidente…, 6 Mar. 2020). The president did not disclose his name or any identifiable information because legal regulations prevented it. In a later interview, the patient zero said that the president’s message aired before the health authorities confirmed that he was positive for the coronavirus. The details shared by the president were enough for patient zero to recognize himself as the first case (Día D, 12 Apr. 2020).

The public identification of the Peruvian patient zero sparked interest from more than just epidemiologists. The general public and authorities wanted to know patient zero’s traveling schedule, and close contacts, among other information that might offer a greater understanding of the virus. As a result, many of his personal details were shared even though they did not relate to the coronavirus. For example, without sharing his name, the minister of Health disclosed that he was a commercial pilot and had been in Europe for his vacations, not for work. This is irrelevant, since the virus could have infected him regardless of the motive of his travel. Latam Airlines, the Peruvian patient zero’s employer, responded by clarifying that he did not travel as part of his work activities (Latam…, 6 mar. 2020). With this statement, the company sought to separate itself from the patient zero and assure passengers that the infection had not occurred on their planes. Yet, Latam could neither confirm nor deny that this was the case.

The Peruvian patient zero gave his first anonymous interview on the Sunday primetime news show Día D conducted by the journalist Pamela Vértiz on March 8, 2020. During the interview, the journalist called him “Pedro,” a fake name to preserve his privacy. The journalist assured the audience that she was interviewing him with “the needed reservation” (Día D, 9 Mar. 2020), appealing to the potential moral and legal consequences of exposing a patient’s name on national television. During the interview, “Pedro” was referred to as the covid-19 patient zero of Peru, and he explained how he became the first detected patient. The patient described visiting several European countries and having symptoms after arriving in Peru. Given these circumstances, he could not conclude if he got sick abroad or once he arrived. The journalist explained that the patient visited a private clinic three times, but on every occasion he was incorrectly diagnosed with a common cold. “Pedro” stressed that he received a correct diagnosis only after he contacted the INS. The INS sent a team to his house to collect a sample, and after his positive diagnosis, they provided him with medical guidance. The patient refused to name the clinic and doctors that misdiagnosed him; moreover, he aimed to inform the population that they had to be persistent if they suspected a covid-19 infection. The journalist emphasized this idea, which presented patient zero as a responsible and concerned citizen who went above and beyond to get the correct diagnosis when others might not have done so.

During the March 8 interview, the journalist Pamela Vértiz did not mention that she knew the patient zero personally. She revealed this information during a later non-anonymous interview with the patient on April 12 (Día D, 12 Apr. 2020). Their relationship explains how the journalist could get an exclusive interview with the patient when the authorities had not disclosed his identity to the media. In both interviews, the media portrayed him as a responsible person who had reached out to the authorities even when doctors dismissed him. The fact that she knew him personally might have affected how the narrative about him was constructed and, by extension, how the public perceived him.

Although the first interview with the patient zero portrayed him as concerned about the spread of the virus, many members of the public rejected this portrayal. They criticized him even without knowing his identity. Día D reposted the interview of March 8 on their social media, where people reacted to his testimony. Some perceived him as responsible for reaching out to authorities and following instructions. Nevertheless, many viewed him as irresponsible for traveling to Europe in the first place, when the virus was known to be circulating there. A comment on Día D ’s Facebook responds to the interview’s framing of the patient zero as a hero: “It is not an act of heroism to tell that he irresponsibly traveled to Peru from places where he had been exposed to the virus” (Neyra Schenone, 9 Mar. 2020). Other users defended him from such criticisms saying, “The young man is helping by providing information about the virus at the risk of revealing his identity” (Sherly, 10 Mar. 2020).

The public viewed patient zero’s socioeconomic status as relevant because it offered information on how he got infected and later recovered. Despite the anonymity of the patient’s first interview, the audience recognized him as young and upper class. A comment read, “the coronavirus came to our country because of the people with money, because the poor do not travel anywhere … rich people are to blame” (Arcentales, 10 Mar. 2020). After his negative test, the authorities showed him as an example of how patients would experience and recover from the coronavirus. The minister of Health called him a model patient who showed that “most cases will pass as a mild respiratory infection” (Ministra…, 16 Mar. 2020). The patient zero’s experience was not representative of the experiences of many coronavirus patients. He had access to medical support, the health authorities closely monitored him (Jochamowitz, León, 2021), and he had the financial means to stay home while recovering.

Social media was a space for the audience’s comments and reactions, and where narratives about the pandemic were built and shared. While individual reactions to the pandemic may be limited to personal networks, social media can amplify opinions to larger audiences. On these platforms, people engaged in conversations about the pandemic’s impacts and were exposed to narratives that traditional media may not have covered. For example, while traditional media may not have commented on the socioeconomic status of Peru’s patient zero, this topic was a recurrent subject of discussion on social media as people interpreted it as a factor in the patient’s infection and recovery.

The Peruvian patient zero went beyond giving anonymous interviews with the media to share his testimony. He also established a direct communication channel with the audience by opening his Instagram account to give a public statement and updates on his health status after testing negative for the coronavirus multiple times. In his first publication, he used Instagram Stories, which disappeared after twenty-four hours but were later saved in his main profile (Zevallos, s.d.). Because Instagram Stories do not support the direct sharing of publications, the public had to take screenshots and tag the patient zero’s account to quote him. The audience could message him directly even though Instagram Stories do not support public comments. Since he used his personal account, the public saw his previous publications, which included photos of his family and friends. The publications about the coronavirus quickly became viral, and many Instagram users shared them, which put attention on his profile.

The patient zero reinforced his status as a person of interest as he shared his personal experience of being the first identified coronavirus patient in Peru on his Instagram account. He self-identified as the patient zero, acknowledging the significance of this term for both him and the public, who quickly recognized the value of his testimony. His publication titled “ quédate en casa ” (stay at home, in English) was the Peruvian government’s slogan for the coronavirus campaign. The publications started with “Hi, I am Luis Felipe, the case 0 of coronavirus in Peru.” They included detailed information about his trip to Europe, his symptoms, details of his infected relatives, the medicines that doctors prescribed, and the names of the doctors who treated him, among other information. He said people should not use his publication to self-medicate since he was not prescribing these medicines, just sharing his experience. He also stressed the importance of isolation to limit the spread of the virus and follow the government’s protocol. Finally, he posted a negative result of the molecular coronavirus test and concluded that he had beaten covid-19.

The public’s interest in patient zero was extensive and long-lived, continuing throughout the pandemic and impacting those around him. The public was also interested in his family and the doctors who treated him while he was sick. In later posts, he included a video of his seven-year-old nephew, who had previously tested positive for coronavirus, asking people to stay home. The patient zero also posted about his grandparents and how they survived the coronavirus despite being at higher risk because of their age. Although the publications had more than two thousand likes, the public could not comment on the Instagram posts because the comments were disabled, a common strategy when social media users expect an adverse reaction. On his social media, the patient zero introduced doctor Ramos, an infectious diseases physician from the Ministry of Health who was part of the covid-19 team. Doctor Ramos used his social media to share information about the virus while collaborating with traditional media (Ramos Correa, s.d.). In 2021, doctor Ramos died during the second wave of the coronavirus in Peru. The media reported his death as the “doctor who treated covid-19 ‘patient zero’” (Redacción EC, 17 Mar. 2021), demonstrating that more than a year after the first coronavirus case in Peru, the news recognized the doctor by his relationship with patient zero.

Patient zero received many negative comments on social media, but he considered them part of his responsibility to help inform the public. It is undetermined how many people saw his posts and reached out to him privately, as he disabled public comments. His Instagram posts related to the coronavirus had thousands of likes, and his profile gained more than ten thousand followers in March 2020. In an interview with Día D , he explains that he had to close his Instagram account due to the influx of hate comments. The negative comments affected his well-being and mental health, but he still saw it as his responsibility to provide information and guidance to the public. He tried to empathize with the audience and referred to his “self-esteem” as the reason he overcame the criticism. He also recognized that the negative attention would have affected others more severely (Día D, 12 Apr. 2020).

The journalists and patient zero acknowledged the term “patient zero” presented limitations, yet they continued to use the term in their communication. The Peruvian patient zero experienced a contradictory scenario, where he recognized himself as patient zero, assuming a self-imposed responsibility while acknowledging potential previous cases. In the April 12 interview, the patient and his family acknowledged the possibility that he was not the index case, as there may have been multiple introductions of the virus before his diagnosis. The interview also featured an epidemiologist’s testimony stating that “he is the patient zero that was captured by personal choice,” meaning that it was highly likely that he was not the index case. The interview ends with a final commentary from the program’s host, who said that “patient zero stood in the spotlight to give the warning signal that we were facing a virus still under study and with no vaccine in sight” (Día D, 12 Apr. 2020).