How To Write The Results/Findings Chapter

For quantitative studies (dissertations & theses).

By: Derek Jansen (MBA). Expert Reviewed By: Kerryn Warren (PhD) | July 2021

So, you’ve completed your quantitative data analysis and it’s time to report on your findings. But where do you start? In this post, we’ll walk you through the results chapter (also called the findings or analysis chapter), step by step, so that you can craft this section of your dissertation or thesis with confidence. If you’re looking for information regarding the results chapter for qualitative studies, you can find that here .

Overview: Quantitative Results Chapter

- What exactly the results/findings/analysis chapter is

- What you need to include in your results chapter

- How to structure your results chapter

- A few tips and tricks for writing top-notch chapter

What exactly is the results chapter?

The results chapter (also referred to as the findings or analysis chapter) is one of the most important chapters of your dissertation or thesis because it shows the reader what you’ve found in terms of the quantitative data you’ve collected. It presents the data using a clear text narrative, supported by tables, graphs and charts. In doing so, it also highlights any potential issues (such as outliers or unusual findings) you’ve come across.

But how’s that different from the discussion chapter?

Well, in the results chapter, you only present your statistical findings. Only the numbers, so to speak – no more, no less. Contrasted to this, in the discussion chapter , you interpret your findings and link them to prior research (i.e. your literature review), as well as your research objectives and research questions . In other words, the results chapter presents and describes the data, while the discussion chapter interprets the data.

Let’s look at an example.

In your results chapter, you may have a plot that shows how respondents to a survey responded: the numbers of respondents per category, for instance. You may also state whether this supports a hypothesis by using a p-value from a statistical test. But it is only in the discussion chapter where you will say why this is relevant or how it compares with the literature or the broader picture. So, in your results chapter, make sure that you don’t present anything other than the hard facts – this is not the place for subjectivity.

It’s worth mentioning that some universities prefer you to combine the results and discussion chapters. Even so, it is good practice to separate the results and discussion elements within the chapter, as this ensures your findings are fully described. Typically, though, the results and discussion chapters are split up in quantitative studies. If you’re unsure, chat with your research supervisor or chair to find out what their preference is.

What should you include in the results chapter?

Following your analysis, it’s likely you’ll have far more data than are necessary to include in your chapter. In all likelihood, you’ll have a mountain of SPSS or R output data, and it’s your job to decide what’s most relevant. You’ll need to cut through the noise and focus on the data that matters.

This doesn’t mean that those analyses were a waste of time – on the contrary, those analyses ensure that you have a good understanding of your dataset and how to interpret it. However, that doesn’t mean your reader or examiner needs to see the 165 histograms you created! Relevance is key.

How do I decide what’s relevant?

At this point, it can be difficult to strike a balance between what is and isn’t important. But the most important thing is to ensure your results reflect and align with the purpose of your study . So, you need to revisit your research aims, objectives and research questions and use these as a litmus test for relevance. Make sure that you refer back to these constantly when writing up your chapter so that you stay on track.

As a general guide, your results chapter will typically include the following:

- Some demographic data about your sample

- Reliability tests (if you used measurement scales)

- Descriptive statistics

- Inferential statistics (if your research objectives and questions require these)

- Hypothesis tests (again, if your research objectives and questions require these)

We’ll discuss each of these points in more detail in the next section.

Importantly, your results chapter needs to lay the foundation for your discussion chapter . This means that, in your results chapter, you need to include all the data that you will use as the basis for your interpretation in the discussion chapter.

For example, if you plan to highlight the strong relationship between Variable X and Variable Y in your discussion chapter, you need to present the respective analysis in your results chapter – perhaps a correlation or regression analysis.

Need a helping hand?

How do I write the results chapter?

There are multiple steps involved in writing up the results chapter for your quantitative research. The exact number of steps applicable to you will vary from study to study and will depend on the nature of the research aims, objectives and research questions . However, we’ll outline the generic steps below.

Step 1 – Revisit your research questions

The first step in writing your results chapter is to revisit your research objectives and research questions . These will be (or at least, should be!) the driving force behind your results and discussion chapters, so you need to review them and then ask yourself which statistical analyses and tests (from your mountain of data) would specifically help you address these . For each research objective and research question, list the specific piece (or pieces) of analysis that address it.

At this stage, it’s also useful to think about the key points that you want to raise in your discussion chapter and note these down so that you have a clear reminder of which data points and analyses you want to highlight in the results chapter. Again, list your points and then list the specific piece of analysis that addresses each point.

Next, you should draw up a rough outline of how you plan to structure your chapter . Which analyses and statistical tests will you present and in what order? We’ll discuss the “standard structure” in more detail later, but it’s worth mentioning now that it’s always useful to draw up a rough outline before you start writing (this advice applies to any chapter).

Step 2 – Craft an overview introduction

As with all chapters in your dissertation or thesis, you should start your quantitative results chapter by providing a brief overview of what you’ll do in the chapter and why . For example, you’d explain that you will start by presenting demographic data to understand the representativeness of the sample, before moving onto X, Y and Z.

This section shouldn’t be lengthy – a paragraph or two maximum. Also, it’s a good idea to weave the research questions into this section so that there’s a golden thread that runs through the document.

Step 3 – Present the sample demographic data

The first set of data that you’ll present is an overview of the sample demographics – in other words, the demographics of your respondents.

For example:

- What age range are they?

- How is gender distributed?

- How is ethnicity distributed?

- What areas do the participants live in?

The purpose of this is to assess how representative the sample is of the broader population. This is important for the sake of the generalisability of the results. If your sample is not representative of the population, you will not be able to generalise your findings. This is not necessarily the end of the world, but it is a limitation you’ll need to acknowledge.

Of course, to make this representativeness assessment, you’ll need to have a clear view of the demographics of the population. So, make sure that you design your survey to capture the correct demographic information that you will compare your sample to.

But what if I’m not interested in generalisability?

Well, even if your purpose is not necessarily to extrapolate your findings to the broader population, understanding your sample will allow you to interpret your findings appropriately, considering who responded. In other words, it will help you contextualise your findings . For example, if 80% of your sample was aged over 65, this may be a significant contextual factor to consider when interpreting the data. Therefore, it’s important to understand and present the demographic data.

Step 4 – Review composite measures and the data “shape”.

Before you undertake any statistical analysis, you’ll need to do some checks to ensure that your data are suitable for the analysis methods and techniques you plan to use. If you try to analyse data that doesn’t meet the assumptions of a specific statistical technique, your results will be largely meaningless. Therefore, you may need to show that the methods and techniques you’ll use are “allowed”.

Most commonly, there are two areas you need to pay attention to:

#1: Composite measures

The first is when you have multiple scale-based measures that combine to capture one construct – this is called a composite measure . For example, you may have four Likert scale-based measures that (should) all measure the same thing, but in different ways. In other words, in a survey, these four scales should all receive similar ratings. This is called “ internal consistency ”.

Internal consistency is not guaranteed though (especially if you developed the measures yourself), so you need to assess the reliability of each composite measure using a test. Typically, Cronbach’s Alpha is a common test used to assess internal consistency – i.e., to show that the items you’re combining are more or less saying the same thing. A high alpha score means that your measure is internally consistent. A low alpha score means you may need to consider scrapping one or more of the measures.

#2: Data shape

The second matter that you should address early on in your results chapter is data shape. In other words, you need to assess whether the data in your set are symmetrical (i.e. normally distributed) or not, as this will directly impact what type of analyses you can use. For many common inferential tests such as T-tests or ANOVAs (we’ll discuss these a bit later), your data needs to be normally distributed. If it’s not, you’ll need to adjust your strategy and use alternative tests.

To assess the shape of the data, you’ll usually assess a variety of descriptive statistics (such as the mean, median and skewness), which is what we’ll look at next.

Step 5 – Present the descriptive statistics

Now that you’ve laid the foundation by discussing the representativeness of your sample, as well as the reliability of your measures and the shape of your data, you can get started with the actual statistical analysis. The first step is to present the descriptive statistics for your variables.

For scaled data, this usually includes statistics such as:

- The mean – this is simply the mathematical average of a range of numbers.

- The median – this is the midpoint in a range of numbers when the numbers are arranged in order.

- The mode – this is the most commonly repeated number in the data set.

- Standard deviation – this metric indicates how dispersed a range of numbers is. In other words, how close all the numbers are to the mean (the average).

- Skewness – this indicates how symmetrical a range of numbers is. In other words, do they tend to cluster into a smooth bell curve shape in the middle of the graph (this is called a normal or parametric distribution), or do they lean to the left or right (this is called a non-normal or non-parametric distribution).

- Kurtosis – this metric indicates whether the data are heavily or lightly-tailed, relative to the normal distribution. In other words, how peaked or flat the distribution is.

A large table that indicates all the above for multiple variables can be a very effective way to present your data economically. You can also use colour coding to help make the data more easily digestible.

For categorical data, where you show the percentage of people who chose or fit into a category, for instance, you can either just plain describe the percentages or numbers of people who responded to something or use graphs and charts (such as bar graphs and pie charts) to present your data in this section of the chapter.

When using figures, make sure that you label them simply and clearly , so that your reader can easily understand them. There’s nothing more frustrating than a graph that’s missing axis labels! Keep in mind that although you’ll be presenting charts and graphs, your text content needs to present a clear narrative that can stand on its own. In other words, don’t rely purely on your figures and tables to convey your key points: highlight the crucial trends and values in the text. Figures and tables should complement the writing, not carry it .

Depending on your research aims, objectives and research questions, you may stop your analysis at this point (i.e. descriptive statistics). However, if your study requires inferential statistics, then it’s time to deep dive into those .

Step 6 – Present the inferential statistics

Inferential statistics are used to make generalisations about a population , whereas descriptive statistics focus purely on the sample . Inferential statistical techniques, broadly speaking, can be broken down into two groups .

First, there are those that compare measurements between groups , such as t-tests (which measure differences between two groups) and ANOVAs (which measure differences between multiple groups). Second, there are techniques that assess the relationships between variables , such as correlation analysis and regression analysis. Within each of these, some tests can be used for normally distributed (parametric) data and some tests are designed specifically for use on non-parametric data.

There are a seemingly endless number of tests that you can use to crunch your data, so it’s easy to run down a rabbit hole and end up with piles of test data. Ultimately, the most important thing is to make sure that you adopt the tests and techniques that allow you to achieve your research objectives and answer your research questions .

In this section of the results chapter, you should try to make use of figures and visual components as effectively as possible. For example, if you present a correlation table, use colour coding to highlight the significance of the correlation values, or scatterplots to visually demonstrate what the trend is. The easier you make it for your reader to digest your findings, the more effectively you’ll be able to make your arguments in the next chapter.

Step 7 – Test your hypotheses

If your study requires it, the next stage is hypothesis testing. A hypothesis is a statement , often indicating a difference between groups or relationship between variables, that can be supported or rejected by a statistical test. However, not all studies will involve hypotheses (again, it depends on the research objectives), so don’t feel like you “must” present and test hypotheses just because you’re undertaking quantitative research.

The basic process for hypothesis testing is as follows:

- Specify your null hypothesis (for example, “The chemical psilocybin has no effect on time perception).

- Specify your alternative hypothesis (e.g., “The chemical psilocybin has an effect on time perception)

- Set your significance level (this is usually 0.05)

- Calculate your statistics and find your p-value (e.g., p=0.01)

- Draw your conclusions (e.g., “The chemical psilocybin does have an effect on time perception”)

Finally, if the aim of your study is to develop and test a conceptual framework , this is the time to present it, following the testing of your hypotheses. While you don’t need to develop or discuss these findings further in the results chapter, indicating whether the tests (and their p-values) support or reject the hypotheses is crucial.

Step 8 – Provide a chapter summary

To wrap up your results chapter and transition to the discussion chapter, you should provide a brief summary of the key findings . “Brief” is the keyword here – much like the chapter introduction, this shouldn’t be lengthy – a paragraph or two maximum. Highlight the findings most relevant to your research objectives and research questions, and wrap it up.

Some final thoughts, tips and tricks

Now that you’ve got the essentials down, here are a few tips and tricks to make your quantitative results chapter shine:

- When writing your results chapter, report your findings in the past tense . You’re talking about what you’ve found in your data, not what you are currently looking for or trying to find.

- Structure your results chapter systematically and sequentially . If you had two experiments where findings from the one generated inputs into the other, report on them in order.

- Make your own tables and graphs rather than copying and pasting them from statistical analysis programmes like SPSS. Check out the DataIsBeautiful reddit for some inspiration.

- Once you’re done writing, review your work to make sure that you have provided enough information to answer your research questions , but also that you didn’t include superfluous information.

If you’ve got any questions about writing up the quantitative results chapter, please leave a comment below. If you’d like 1-on-1 assistance with your quantitative analysis and discussion, check out our hands-on coaching service , or book a free consultation with a friendly coach.

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

Thank you. I will try my best to write my results.

Awesome content 👏🏾

this was great explaination

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Quantitative Data Analysis

9 Presenting the Results of Quantitative Analysis

Mikaila Mariel Lemonik Arthur

This chapter provides an overview of how to present the results of quantitative analysis, in particular how to create effective tables for displaying quantitative results and how to write quantitative research papers that effectively communicate the methods used and findings of quantitative analysis.

Writing the Quantitative Paper

Standard quantitative social science papers follow a specific format. They begin with a title page that includes a descriptive title, the author(s)’ name(s), and a 100 to 200 word abstract that summarizes the paper. Next is an introduction that makes clear the paper’s research question, details why this question is important, and previews what the paper will do. After that comes a literature review, which ends with a summary of the research question(s) and/or hypotheses. A methods section, which explains the source of data, sample, and variables and quantitative techniques used, follows. Many analysts will include a short discussion of their descriptive statistics in the methods section. A findings section details the findings of the analysis, supported by a variety of tables, and in some cases graphs, all of which are explained in the text. Some quantitative papers, especially those using more complex techniques, will include equations. Many papers follow the findings section with a discussion section, which provides an interpretation of the results in light of both the prior literature and theory presented in the literature review and the research questions/hypotheses. A conclusion ends the body of the paper. This conclusion should summarize the findings, answering the research questions and stating whether any hypotheses were supported, partially supported, or not supported. Limitations of the research are detailed. Papers typically include suggestions for future research, and where relevant, some papers include policy implications. After the body of the paper comes the works cited; some papers also have an Appendix that includes additional tables and figures that did not fit into the body of the paper or additional methodological details. While this basic format is similar for papers regardless of the type of data they utilize, there are specific concerns relating to quantitative research in terms of the methods and findings that will be discussed here.

In the methods section, researchers clearly describe the methods they used to obtain and analyze the data for their research. When relying on data collected specifically for a given paper, researchers will need to discuss the sample and data collection; in most cases, though, quantitative research relies on pre-existing datasets. In these cases, researchers need to provide information about the dataset, including the source of the data, the time it was collected, the population, and the sample size. Regardless of the source of the data, researchers need to be clear about which variables they are using in their research and any transformations or manipulations of those variables. They also need to explain the specific quantitative techniques that they are using in their analysis; if different techniques are used to test different hypotheses, this should be made clear. In some cases, publications will require that papers be submitted along with any code that was used to produce the analysis (in SPSS terms, the syntax files), which more advanced researchers will usually have on hand. In many cases, basic descriptive statistics are presented in tabular form and explained within the methods section.

The findings sections of quantitative papers are organized around explaining the results as shown in tables and figures. Not all results are depicted in tables and figures—some minor or null findings will simply be referenced—but tables and figures should be produced for all findings to be discussed at any length. If there are too many tables and figures, some can be moved to an appendix after the body of the text and referred to in the text (e.g. “See Table 12 in Appendix A”).

Discussions of the findings should not simply restate the contents of the table. Rather, they should explain and interpret it for readers, and they should do so in light of the hypothesis or hypotheses that are being tested. Conclusions—discussions of whether the hypothesis or hypotheses are supported or not supported—should wait for the conclusion of the paper.

Creating Effective Tables

When creating tables to display the results of quantitative analysis, the most important goals are to create tables that are clear and concise but that also meet standard conventions in the field. This means, first of all, paring down the volume of information produced in the statistical output to just include the information most necessary for interpreting the results, but doing so in keeping with standard table conventions. It also means making tables that are well-formatted and designed, so that readers can understand what the tables are saying without struggling to find information. For example, tables (as well as figures such as graphs) need clear captions; they are typically numbered and referred to by number in the text. Columns and rows should have clear headings. Depending on the content of the table, formatting tools may need to be used to set off header rows/columns and/or total rows/columns; cell-merging tools may be necessary; and shading may be important in tables with many rows or columns.

Here, you will find some instructions for creating tables of results from descriptive, crosstabulation, correlation, and regression analysis that are clear, concise, and meet normal standards for data display in social science. In addition, after the instructions for creating tables, you will find an example of how a paper incorporating each table might describe that table in the text.

Descriptive Statistics

When presenting the results of descriptive statistics, we create one table with columns for each type of descriptive statistic and rows for each variable. Note, of course, that depending on level of measurement only certain descriptive statistics are appropriate for a given variable, so there may be many cells in the table marked with an — to show that this statistic is not calculated for this variable. So, consider the set of descriptive statistics below, for occupational prestige, age, highest degree earned, and whether the respondent was born in this country.

To display these descriptive statistics in a paper, one might create a table like Table 2. Note that for discrete variables, we use the value label in the table, not the value.

If we were then to discuss our descriptive statistics in a quantitative paper, we might write something like this (note that we do not need to repeat every single detail from the table, as readers can peruse the table themselves):

This analysis relies on four variables from the 2021 General Social Survey: occupational prestige score, age, highest degree earned, and whether the respondent was born in the United States. Descriptive statistics for all four variables are shown in Table 2. The median occupational prestige score is 47, with a range from 16 to 80. 50% of respondents had occupational prestige scores scores between 35 and 59. The median age of respondents is 53, with a range from 18 to 89. 50% of respondents are between ages 37 and 66. Both variables have little skew. Highest degree earned ranges from less than high school to a graduate degree; the median respondent has earned an associate’s degree, while the modal response (given by 39.8% of the respondents) is a high school degree. 88.8% of respondents were born in the United States.

Crosstabulation

When presenting the results of a crosstabulation, we simplify the table so that it highlights the most important information—the column percentages—and include the significance and association below the table. Consider the SPSS output below.

Table 4 shows how a table suitable for include in a paper might look if created from the SPSS output in Table 3. Note that we use asterisks to indicate the significance level of the results: * means p < 0.05; ** means p < 0.01; *** means p < 0.001; and no stars mean p > 0.05 (and thus that the result is not significant). Also note than N is the abbreviation for the number of respondents.

If we were going to discuss the results of this crosstabulation in a quantitative research paper, the discussion might look like this:

A crosstabulation of respondent’s class identification and their highest degree earned, with class identification as the independent variable, is significant, with a Spearman correlation of 0.419, as shown in Table 4. Among lower class and working class respondents, more than 50% had earned a high school degree. Less than 20% of poor respondents and less than 40% of working-class respondents had earned more than a high school degree. In contrast, the majority of middle class and upper class respondents had earned at least a bachelor’s degree. In fact, 50% of upper class respondents had earned a graduate degree.

Correlation

When presenting a correlating matrix, one of the most important things to note is that we only present half the table so as not to include duplicated results. Think of the line through the table where empty cells exist to represent the correlation between a variable and itself, and include only the triangle of data either above or below that line of cells. Consider the output in Table 5.

Table 6 shows what the contents of Table 5 might look like when a table is constructed in a fashion suitable for publication.

If we were to discuss the results of this bivariate correlation analysis in a quantitative paper, the discussion might look like this:

Bivariate correlations were run among variables measuring age, occupational prestige, the highest year of school respondents completed, and family income in constant 1986 dollars, as shown in Table 6. Correlations between age and highest year of school completed and between age and family income are not significant. All other correlations are positive and significant at the p<0.001 level. The correlation between age and occupational prestige is weak; the correlations between income and occupational prestige and between income and educational attainment are moderate, and the correlation between education and occupational prestige is strong.

To present the results of a regression, we create one table that includes all of the key information from the multiple tables of SPSS output. This includes the R 2 and significance of the regression, either the B or the beta values (different analysts have different preferences here) for each variable, and the standard error and significance of each variable. Consider the SPSS output in Table 7.

The regression output in shown in Table 7 contains a lot of information. We do not include all of this information when making tables suitable for publication. As can be seen in Table 8, we include the Beta (or the B), the standard error, and the significance asterisk for each variable; the R 2 and significance for the overall regression; the degrees of freedom (which tells readers the sample size or N); and the constant; along with the key to p/significance values.

If we were to discuss the results of this regression in a quantitative paper, the results might look like this:

Table 8 shows the results of a regression in which age, occupational prestige, and highest year of school completed are the independent variables and family income is the dependent variable. The regression results are significant, and all of the independent variables taken together explain 15.6% of the variance in family income. Age is not a significant predictor of income, while occupational prestige and educational attainment are. Educational attainment has a larger effect on family income than does occupational prestige. For every year of additional education attained, family income goes up on average by $3,988.545; for every one-unit increase in occupational prestige score, family income goes up on average by $522.887. [1]

- Choose two discrete variables and three continuous variables from a dataset of your choice. Produce appropriate descriptive statistics on all five of the variables and create a table of the results suitable for inclusion in a paper.

- Using the two discrete variables you have chosen, produce an appropriate crosstabulation, with significance and measure of association. Create a table of the results suitable for inclusion in a paper.

- Using the three continuous variables you have chosen, produce a correlation matrix. Create a table of the results suitable for inclusion in a paper.

- Using the three continuous variables you have chosen, produce a multivariate linear regression. Create a table of the results suitable for inclusion in a paper.

- Write a methods section describing the dataset, analytical methods, and variables you utilized in questions 1, 2, 3, and 4 and explaining the results of your descriptive analysis.

- Write a findings section explaining the results of the analyses you performed in questions 2, 3, and 4.

- Note that the actual numberical increase comes from the B values, which are shown in the SPSS output in Table 7 but not in the reformatted Table 8. ↵

Social Data Analysis Copyright © 2021 by Mikaila Mariel Lemonik Arthur is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods

What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods

Published on June 12, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Quantitative research is the process of collecting and analyzing numerical data. It can be used to find patterns and averages, make predictions, test causal relationships, and generalize results to wider populations.

Quantitative research is the opposite of qualitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio).

Quantitative research is widely used in the natural and social sciences: biology, chemistry, psychology, economics, sociology, marketing, etc.

- What is the demographic makeup of Singapore in 2020?

- How has the average temperature changed globally over the last century?

- Does environmental pollution affect the prevalence of honey bees?

- Does working from home increase productivity for people with long commutes?

Table of contents

Quantitative research methods, quantitative data analysis, advantages of quantitative research, disadvantages of quantitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about quantitative research.

You can use quantitative research methods for descriptive, correlational or experimental research.

- In descriptive research , you simply seek an overall summary of your study variables.

- In correlational research , you investigate relationships between your study variables.

- In experimental research , you systematically examine whether there is a cause-and-effect relationship between variables.

Correlational and experimental research can both be used to formally test hypotheses , or predictions, using statistics. The results may be generalized to broader populations based on the sampling method used.

To collect quantitative data, you will often need to use operational definitions that translate abstract concepts (e.g., mood) into observable and quantifiable measures (e.g., self-ratings of feelings and energy levels).

Note that quantitative research is at risk for certain research biases , including information bias , omitted variable bias , sampling bias , or selection bias . Be sure that you’re aware of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data to prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once data is collected, you may need to process it before it can be analyzed. For example, survey and test data may need to be transformed from words to numbers. Then, you can use statistical analysis to answer your research questions .

Descriptive statistics will give you a summary of your data and include measures of averages and variability. You can also use graphs, scatter plots and frequency tables to visualize your data and check for any trends or outliers.

Using inferential statistics , you can make predictions or generalizations based on your data. You can test your hypothesis or use your sample data to estimate the population parameter .

First, you use descriptive statistics to get a summary of the data. You find the mean (average) and the mode (most frequent rating) of procrastination of the two groups, and plot the data to see if there are any outliers.

You can also assess the reliability and validity of your data collection methods to indicate how consistently and accurately your methods actually measured what you wanted them to.

Quantitative research is often used to standardize data collection and generalize findings . Strengths of this approach include:

- Replication

Repeating the study is possible because of standardized data collection protocols and tangible definitions of abstract concepts.

- Direct comparisons of results

The study can be reproduced in other cultural settings, times or with different groups of participants. Results can be compared statistically.

- Large samples

Data from large samples can be processed and analyzed using reliable and consistent procedures through quantitative data analysis.

- Hypothesis testing

Using formalized and established hypothesis testing procedures means that you have to carefully consider and report your research variables, predictions, data collection and testing methods before coming to a conclusion.

Despite the benefits of quantitative research, it is sometimes inadequate in explaining complex research topics. Its limitations include:

- Superficiality

Using precise and restrictive operational definitions may inadequately represent complex concepts. For example, the concept of mood may be represented with just a number in quantitative research, but explained with elaboration in qualitative research.

- Narrow focus

Predetermined variables and measurement procedures can mean that you ignore other relevant observations.

- Structural bias

Despite standardized procedures, structural biases can still affect quantitative research. Missing data , imprecise measurements or inappropriate sampling methods are biases that can lead to the wrong conclusions.

- Lack of context

Quantitative research often uses unnatural settings like laboratories or fails to consider historical and cultural contexts that may affect data collection and results.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

Operationalization means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioral avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalize the variables that you want to measure.

Reliability and validity are both about how well a method measures something:

- Reliability refers to the consistency of a measure (whether the results can be reproduced under the same conditions).

- Validity refers to the accuracy of a measure (whether the results really do represent what they are supposed to measure).

If you are doing experimental research, you also have to consider the internal and external validity of your experiment.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved April 1, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/quantitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, descriptive statistics | definitions, types, examples, inferential statistics | an easy introduction & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Make a Successful Research Presentation

Turning a research paper into a visual presentation is difficult; there are pitfalls, and navigating the path to a brief, informative presentation takes time and practice. As a TA for GEO/WRI 201: Methods in Data Analysis & Scientific Writing this past fall, I saw how this process works from an instructor’s standpoint. I’ve presented my own research before, but helping others present theirs taught me a bit more about the process. Here are some tips I learned that may help you with your next research presentation:

More is more

In general, your presentation will always benefit from more practice, more feedback, and more revision. By practicing in front of friends, you can get comfortable with presenting your work while receiving feedback. It is hard to know how to revise your presentation if you never practice. If you are presenting to a general audience, getting feedback from someone outside of your discipline is crucial. Terms and ideas that seem intuitive to you may be completely foreign to someone else, and your well-crafted presentation could fall flat.

Less is more

Limit the scope of your presentation, the number of slides, and the text on each slide. In my experience, text works well for organizing slides, orienting the audience to key terms, and annotating important figures–not for explaining complex ideas. Having fewer slides is usually better as well. In general, about one slide per minute of presentation is an appropriate budget. Too many slides is usually a sign that your topic is too broad.

Limit the scope of your presentation

Don’t present your paper. Presentations are usually around 10 min long. You will not have time to explain all of the research you did in a semester (or a year!) in such a short span of time. Instead, focus on the highlight(s). Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

You will not have time to explain all of the research you did. Instead, focus on the highlights. Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

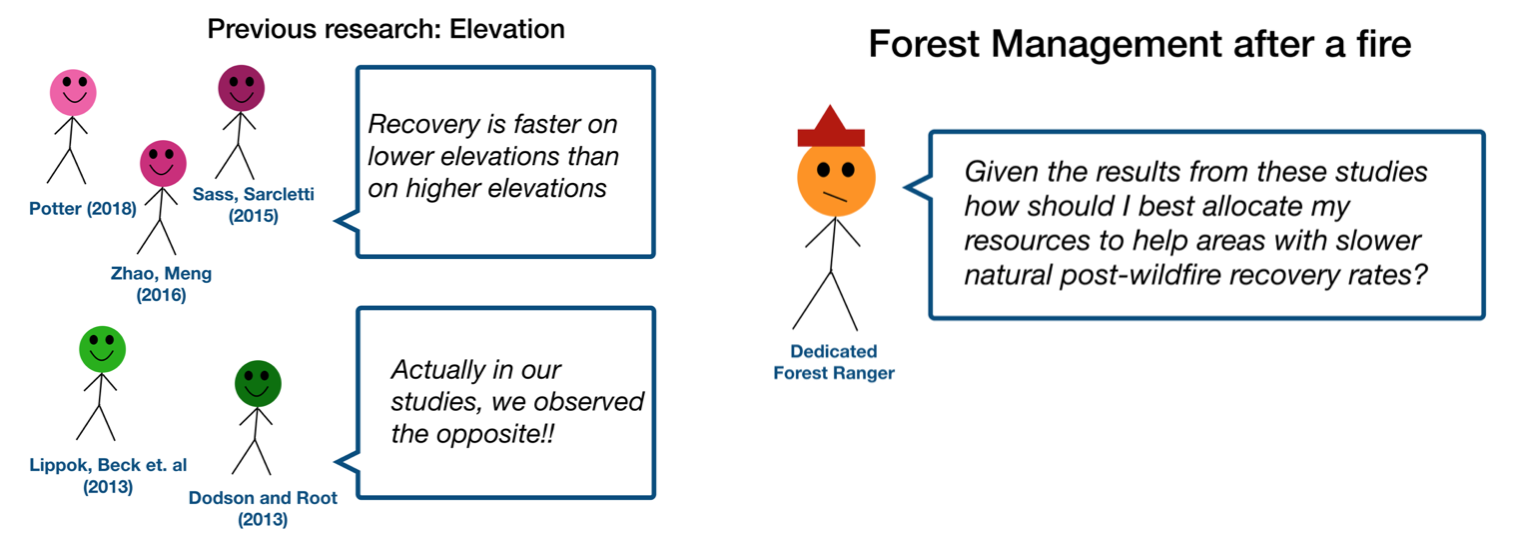

Craft a compelling research narrative

After identifying the focused research question, walk your audience through your research as if it were a story. Presentations with strong narrative arcs are clear, captivating, and compelling.

- Introduction (exposition — rising action)

Orient the audience and draw them in by demonstrating the relevance and importance of your research story with strong global motive. Provide them with the necessary vocabulary and background knowledge to understand the plot of your story. Introduce the key studies (characters) relevant in your story and build tension and conflict with scholarly and data motive. By the end of your introduction, your audience should clearly understand your research question and be dying to know how you resolve the tension built through motive.

- Methods (rising action)

The methods section should transition smoothly and logically from the introduction. Beware of presenting your methods in a boring, arc-killing, ‘this is what I did.’ Focus on the details that set your story apart from the stories other people have already told. Keep the audience interested by clearly motivating your decisions based on your original research question or the tension built in your introduction.

- Results (climax)

Less is usually more here. Only present results which are clearly related to the focused research question you are presenting. Make sure you explain the results clearly so that your audience understands what your research found. This is the peak of tension in your narrative arc, so don’t undercut it by quickly clicking through to your discussion.

- Discussion (falling action)

By now your audience should be dying for a satisfying resolution. Here is where you contextualize your results and begin resolving the tension between past research. Be thorough. If you have too many conflicts left unresolved, or you don’t have enough time to present all of the resolutions, you probably need to further narrow the scope of your presentation.

- Conclusion (denouement)

Return back to your initial research question and motive, resolving any final conflicts and tying up loose ends. Leave the audience with a clear resolution of your focus research question, and use unresolved tension to set up potential sequels (i.e. further research).

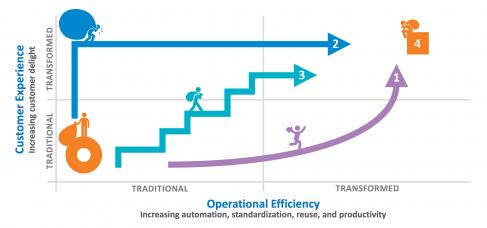

Use your medium to enhance the narrative

Visual presentations should be dominated by clear, intentional graphics. Subtle animation in key moments (usually during the results or discussion) can add drama to the narrative arc and make conflict resolutions more satisfying. You are narrating a story written in images, videos, cartoons, and graphs. While your paper is mostly text, with graphics to highlight crucial points, your slides should be the opposite. Adapting to the new medium may require you to create or acquire far more graphics than you included in your paper, but it is necessary to create an engaging presentation.

The most important thing you can do for your presentation is to practice and revise. Bother your friends, your roommates, TAs–anybody who will sit down and listen to your work. Beyond that, think about presentations you have found compelling and try to incorporate some of those elements into your own. Remember you want your work to be comprehensible; you aren’t creating experts in 10 minutes. Above all, try to stay passionate about what you did and why. You put the time in, so show your audience that it’s worth it.

For more insight into research presentations, check out these past PCUR posts written by Emma and Ellie .

— Alec Getraer, Natural Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Korean Med Sci

- v.37(16); 2022 Apr 25

A Practical Guide to Writing Quantitative and Qualitative Research Questions and Hypotheses in Scholarly Articles

Edward barroga.

1 Department of General Education, Graduate School of Nursing Science, St. Luke’s International University, Tokyo, Japan.

Glafera Janet Matanguihan

2 Department of Biological Sciences, Messiah University, Mechanicsburg, PA, USA.

The development of research questions and the subsequent hypotheses are prerequisites to defining the main research purpose and specific objectives of a study. Consequently, these objectives determine the study design and research outcome. The development of research questions is a process based on knowledge of current trends, cutting-edge studies, and technological advances in the research field. Excellent research questions are focused and require a comprehensive literature search and in-depth understanding of the problem being investigated. Initially, research questions may be written as descriptive questions which could be developed into inferential questions. These questions must be specific and concise to provide a clear foundation for developing hypotheses. Hypotheses are more formal predictions about the research outcomes. These specify the possible results that may or may not be expected regarding the relationship between groups. Thus, research questions and hypotheses clarify the main purpose and specific objectives of the study, which in turn dictate the design of the study, its direction, and outcome. Studies developed from good research questions and hypotheses will have trustworthy outcomes with wide-ranging social and health implications.

INTRODUCTION

Scientific research is usually initiated by posing evidenced-based research questions which are then explicitly restated as hypotheses. 1 , 2 The hypotheses provide directions to guide the study, solutions, explanations, and expected results. 3 , 4 Both research questions and hypotheses are essentially formulated based on conventional theories and real-world processes, which allow the inception of novel studies and the ethical testing of ideas. 5 , 6

It is crucial to have knowledge of both quantitative and qualitative research 2 as both types of research involve writing research questions and hypotheses. 7 However, these crucial elements of research are sometimes overlooked; if not overlooked, then framed without the forethought and meticulous attention it needs. Planning and careful consideration are needed when developing quantitative or qualitative research, particularly when conceptualizing research questions and hypotheses. 4

There is a continuing need to support researchers in the creation of innovative research questions and hypotheses, as well as for journal articles that carefully review these elements. 1 When research questions and hypotheses are not carefully thought of, unethical studies and poor outcomes usually ensue. Carefully formulated research questions and hypotheses define well-founded objectives, which in turn determine the appropriate design, course, and outcome of the study. This article then aims to discuss in detail the various aspects of crafting research questions and hypotheses, with the goal of guiding researchers as they develop their own. Examples from the authors and peer-reviewed scientific articles in the healthcare field are provided to illustrate key points.

DEFINITIONS AND RELATIONSHIP OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

A research question is what a study aims to answer after data analysis and interpretation. The answer is written in length in the discussion section of the paper. Thus, the research question gives a preview of the different parts and variables of the study meant to address the problem posed in the research question. 1 An excellent research question clarifies the research writing while facilitating understanding of the research topic, objective, scope, and limitations of the study. 5

On the other hand, a research hypothesis is an educated statement of an expected outcome. This statement is based on background research and current knowledge. 8 , 9 The research hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a new phenomenon 10 or a formal statement on the expected relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable. 3 , 11 It provides a tentative answer to the research question to be tested or explored. 4

Hypotheses employ reasoning to predict a theory-based outcome. 10 These can also be developed from theories by focusing on components of theories that have not yet been observed. 10 The validity of hypotheses is often based on the testability of the prediction made in a reproducible experiment. 8

Conversely, hypotheses can also be rephrased as research questions. Several hypotheses based on existing theories and knowledge may be needed to answer a research question. Developing ethical research questions and hypotheses creates a research design that has logical relationships among variables. These relationships serve as a solid foundation for the conduct of the study. 4 , 11 Haphazardly constructed research questions can result in poorly formulated hypotheses and improper study designs, leading to unreliable results. Thus, the formulations of relevant research questions and verifiable hypotheses are crucial when beginning research. 12

CHARACTERISTICS OF GOOD RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Excellent research questions are specific and focused. These integrate collective data and observations to confirm or refute the subsequent hypotheses. Well-constructed hypotheses are based on previous reports and verify the research context. These are realistic, in-depth, sufficiently complex, and reproducible. More importantly, these hypotheses can be addressed and tested. 13

There are several characteristics of well-developed hypotheses. Good hypotheses are 1) empirically testable 7 , 10 , 11 , 13 ; 2) backed by preliminary evidence 9 ; 3) testable by ethical research 7 , 9 ; 4) based on original ideas 9 ; 5) have evidenced-based logical reasoning 10 ; and 6) can be predicted. 11 Good hypotheses can infer ethical and positive implications, indicating the presence of a relationship or effect relevant to the research theme. 7 , 11 These are initially developed from a general theory and branch into specific hypotheses by deductive reasoning. In the absence of a theory to base the hypotheses, inductive reasoning based on specific observations or findings form more general hypotheses. 10

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions and hypotheses are developed according to the type of research, which can be broadly classified into quantitative and qualitative research. We provide a summary of the types of research questions and hypotheses under quantitative and qualitative research categories in Table 1 .

Research questions in quantitative research

In quantitative research, research questions inquire about the relationships among variables being investigated and are usually framed at the start of the study. These are precise and typically linked to the subject population, dependent and independent variables, and research design. 1 Research questions may also attempt to describe the behavior of a population in relation to one or more variables, or describe the characteristics of variables to be measured ( descriptive research questions ). 1 , 5 , 14 These questions may also aim to discover differences between groups within the context of an outcome variable ( comparative research questions ), 1 , 5 , 14 or elucidate trends and interactions among variables ( relationship research questions ). 1 , 5 We provide examples of descriptive, comparative, and relationship research questions in quantitative research in Table 2 .

Hypotheses in quantitative research

In quantitative research, hypotheses predict the expected relationships among variables. 15 Relationships among variables that can be predicted include 1) between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable ( simple hypothesis ) or 2) between two or more independent and dependent variables ( complex hypothesis ). 4 , 11 Hypotheses may also specify the expected direction to be followed and imply an intellectual commitment to a particular outcome ( directional hypothesis ) 4 . On the other hand, hypotheses may not predict the exact direction and are used in the absence of a theory, or when findings contradict previous studies ( non-directional hypothesis ). 4 In addition, hypotheses can 1) define interdependency between variables ( associative hypothesis ), 4 2) propose an effect on the dependent variable from manipulation of the independent variable ( causal hypothesis ), 4 3) state a negative relationship between two variables ( null hypothesis ), 4 , 11 , 15 4) replace the working hypothesis if rejected ( alternative hypothesis ), 15 explain the relationship of phenomena to possibly generate a theory ( working hypothesis ), 11 5) involve quantifiable variables that can be tested statistically ( statistical hypothesis ), 11 6) or express a relationship whose interlinks can be verified logically ( logical hypothesis ). 11 We provide examples of simple, complex, directional, non-directional, associative, causal, null, alternative, working, statistical, and logical hypotheses in quantitative research, as well as the definition of quantitative hypothesis-testing research in Table 3 .

Research questions in qualitative research

Unlike research questions in quantitative research, research questions in qualitative research are usually continuously reviewed and reformulated. The central question and associated subquestions are stated more than the hypotheses. 15 The central question broadly explores a complex set of factors surrounding the central phenomenon, aiming to present the varied perspectives of participants. 15

There are varied goals for which qualitative research questions are developed. These questions can function in several ways, such as to 1) identify and describe existing conditions ( contextual research question s); 2) describe a phenomenon ( descriptive research questions ); 3) assess the effectiveness of existing methods, protocols, theories, or procedures ( evaluation research questions ); 4) examine a phenomenon or analyze the reasons or relationships between subjects or phenomena ( explanatory research questions ); or 5) focus on unknown aspects of a particular topic ( exploratory research questions ). 5 In addition, some qualitative research questions provide new ideas for the development of theories and actions ( generative research questions ) or advance specific ideologies of a position ( ideological research questions ). 1 Other qualitative research questions may build on a body of existing literature and become working guidelines ( ethnographic research questions ). Research questions may also be broadly stated without specific reference to the existing literature or a typology of questions ( phenomenological research questions ), may be directed towards generating a theory of some process ( grounded theory questions ), or may address a description of the case and the emerging themes ( qualitative case study questions ). 15 We provide examples of contextual, descriptive, evaluation, explanatory, exploratory, generative, ideological, ethnographic, phenomenological, grounded theory, and qualitative case study research questions in qualitative research in Table 4 , and the definition of qualitative hypothesis-generating research in Table 5 .

Qualitative studies usually pose at least one central research question and several subquestions starting with How or What . These research questions use exploratory verbs such as explore or describe . These also focus on one central phenomenon of interest, and may mention the participants and research site. 15

Hypotheses in qualitative research

Hypotheses in qualitative research are stated in the form of a clear statement concerning the problem to be investigated. Unlike in quantitative research where hypotheses are usually developed to be tested, qualitative research can lead to both hypothesis-testing and hypothesis-generating outcomes. 2 When studies require both quantitative and qualitative research questions, this suggests an integrative process between both research methods wherein a single mixed-methods research question can be developed. 1

FRAMEWORKS FOR DEVELOPING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions followed by hypotheses should be developed before the start of the study. 1 , 12 , 14 It is crucial to develop feasible research questions on a topic that is interesting to both the researcher and the scientific community. This can be achieved by a meticulous review of previous and current studies to establish a novel topic. Specific areas are subsequently focused on to generate ethical research questions. The relevance of the research questions is evaluated in terms of clarity of the resulting data, specificity of the methodology, objectivity of the outcome, depth of the research, and impact of the study. 1 , 5 These aspects constitute the FINER criteria (i.e., Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, and Relevant). 1 Clarity and effectiveness are achieved if research questions meet the FINER criteria. In addition to the FINER criteria, Ratan et al. described focus, complexity, novelty, feasibility, and measurability for evaluating the effectiveness of research questions. 14

The PICOT and PEO frameworks are also used when developing research questions. 1 The following elements are addressed in these frameworks, PICOT: P-population/patients/problem, I-intervention or indicator being studied, C-comparison group, O-outcome of interest, and T-timeframe of the study; PEO: P-population being studied, E-exposure to preexisting conditions, and O-outcome of interest. 1 Research questions are also considered good if these meet the “FINERMAPS” framework: Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, Relevant, Manageable, Appropriate, Potential value/publishable, and Systematic. 14

As we indicated earlier, research questions and hypotheses that are not carefully formulated result in unethical studies or poor outcomes. To illustrate this, we provide some examples of ambiguous research question and hypotheses that result in unclear and weak research objectives in quantitative research ( Table 6 ) 16 and qualitative research ( Table 7 ) 17 , and how to transform these ambiguous research question(s) and hypothesis(es) into clear and good statements.

a These statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

b These statements are direct quotes from Higashihara and Horiuchi. 16

a This statement is a direct quote from Shimoda et al. 17

The other statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

CONSTRUCTING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

To construct effective research questions and hypotheses, it is very important to 1) clarify the background and 2) identify the research problem at the outset of the research, within a specific timeframe. 9 Then, 3) review or conduct preliminary research to collect all available knowledge about the possible research questions by studying theories and previous studies. 18 Afterwards, 4) construct research questions to investigate the research problem. Identify variables to be accessed from the research questions 4 and make operational definitions of constructs from the research problem and questions. Thereafter, 5) construct specific deductive or inductive predictions in the form of hypotheses. 4 Finally, 6) state the study aims . This general flow for constructing effective research questions and hypotheses prior to conducting research is shown in Fig. 1 .

Research questions are used more frequently in qualitative research than objectives or hypotheses. 3 These questions seek to discover, understand, explore or describe experiences by asking “What” or “How.” The questions are open-ended to elicit a description rather than to relate variables or compare groups. The questions are continually reviewed, reformulated, and changed during the qualitative study. 3 Research questions are also used more frequently in survey projects than hypotheses in experiments in quantitative research to compare variables and their relationships.

Hypotheses are constructed based on the variables identified and as an if-then statement, following the template, ‘If a specific action is taken, then a certain outcome is expected.’ At this stage, some ideas regarding expectations from the research to be conducted must be drawn. 18 Then, the variables to be manipulated (independent) and influenced (dependent) are defined. 4 Thereafter, the hypothesis is stated and refined, and reproducible data tailored to the hypothesis are identified, collected, and analyzed. 4 The hypotheses must be testable and specific, 18 and should describe the variables and their relationships, the specific group being studied, and the predicted research outcome. 18 Hypotheses construction involves a testable proposition to be deduced from theory, and independent and dependent variables to be separated and measured separately. 3 Therefore, good hypotheses must be based on good research questions constructed at the start of a study or trial. 12

In summary, research questions are constructed after establishing the background of the study. Hypotheses are then developed based on the research questions. Thus, it is crucial to have excellent research questions to generate superior hypotheses. In turn, these would determine the research objectives and the design of the study, and ultimately, the outcome of the research. 12 Algorithms for building research questions and hypotheses are shown in Fig. 2 for quantitative research and in Fig. 3 for qualitative research.

EXAMPLES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS FROM PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Descriptive research question (quantitative research)

- - Presents research variables to be assessed (distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes)

- “BACKGROUND: Since COVID-19 was identified, its clinical and biological heterogeneity has been recognized. Identifying COVID-19 phenotypes might help guide basic, clinical, and translational research efforts.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Does the clinical spectrum of patients with COVID-19 contain distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes? ” 19

- EXAMPLE 2. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Shows interactions between dependent variable (static postural control) and independent variable (peripheral visual field loss)

- “Background: Integration of visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive sensations contributes to postural control. People with peripheral visual field loss have serious postural instability. However, the directional specificity of postural stability and sensory reweighting caused by gradual peripheral visual field loss remain unclear.

- Research question: What are the effects of peripheral visual field loss on static postural control ?” 20

- EXAMPLE 3. Comparative research question (quantitative research)

- - Clarifies the difference among groups with an outcome variable (patients enrolled in COMPERA with moderate PH or severe PH in COPD) and another group without the outcome variable (patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH))

- “BACKGROUND: Pulmonary hypertension (PH) in COPD is a poorly investigated clinical condition.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Which factors determine the outcome of PH in COPD?

- STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS: We analyzed the characteristics and outcome of patients enrolled in the Comparative, Prospective Registry of Newly Initiated Therapies for Pulmonary Hypertension (COMPERA) with moderate or severe PH in COPD as defined during the 6th PH World Symposium who received medical therapy for PH and compared them with patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) .” 21

- EXAMPLE 4. Exploratory research question (qualitative research)

- - Explores areas that have not been fully investigated (perspectives of families and children who receive care in clinic-based child obesity treatment) to have a deeper understanding of the research problem

- “Problem: Interventions for children with obesity lead to only modest improvements in BMI and long-term outcomes, and data are limited on the perspectives of families of children with obesity in clinic-based treatment. This scoping review seeks to answer the question: What is known about the perspectives of families and children who receive care in clinic-based child obesity treatment? This review aims to explore the scope of perspectives reported by families of children with obesity who have received individualized outpatient clinic-based obesity treatment.” 22

- EXAMPLE 5. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Defines interactions between dependent variable (use of ankle strategies) and independent variable (changes in muscle tone)

- “Background: To maintain an upright standing posture against external disturbances, the human body mainly employs two types of postural control strategies: “ankle strategy” and “hip strategy.” While it has been reported that the magnitude of the disturbance alters the use of postural control strategies, it has not been elucidated how the level of muscle tone, one of the crucial parameters of bodily function, determines the use of each strategy. We have previously confirmed using forward dynamics simulations of human musculoskeletal models that an increased muscle tone promotes the use of ankle strategies. The objective of the present study was to experimentally evaluate a hypothesis: an increased muscle tone promotes the use of ankle strategies. Research question: Do changes in the muscle tone affect the use of ankle strategies ?” 23

EXAMPLES OF HYPOTHESES IN PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Working hypothesis (quantitative research)

- - A hypothesis that is initially accepted for further research to produce a feasible theory

- “As fever may have benefit in shortening the duration of viral illness, it is plausible to hypothesize that the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen may be hindering the benefits of a fever response when taken during the early stages of COVID-19 illness .” 24

- “In conclusion, it is plausible to hypothesize that the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen may be hindering the benefits of a fever response . The difference in perceived safety of these agents in COVID-19 illness could be related to the more potent efficacy to reduce fever with ibuprofen compared to acetaminophen. Compelling data on the benefit of fever warrant further research and review to determine when to treat or withhold ibuprofen for early stage fever for COVID-19 and other related viral illnesses .” 24

- EXAMPLE 2. Exploratory hypothesis (qualitative research)

- - Explores particular areas deeper to clarify subjective experience and develop a formal hypothesis potentially testable in a future quantitative approach

- “We hypothesized that when thinking about a past experience of help-seeking, a self distancing prompt would cause increased help-seeking intentions and more favorable help-seeking outcome expectations .” 25

- “Conclusion

- Although a priori hypotheses were not supported, further research is warranted as results indicate the potential for using self-distancing approaches to increasing help-seeking among some people with depressive symptomatology.” 25

- EXAMPLE 3. Hypothesis-generating research to establish a framework for hypothesis testing (qualitative research)

- “We hypothesize that compassionate care is beneficial for patients (better outcomes), healthcare systems and payers (lower costs), and healthcare providers (lower burnout). ” 26

- Compassionomics is the branch of knowledge and scientific study of the effects of compassionate healthcare. Our main hypotheses are that compassionate healthcare is beneficial for (1) patients, by improving clinical outcomes, (2) healthcare systems and payers, by supporting financial sustainability, and (3) HCPs, by lowering burnout and promoting resilience and well-being. The purpose of this paper is to establish a scientific framework for testing the hypotheses above . If these hypotheses are confirmed through rigorous research, compassionomics will belong in the science of evidence-based medicine, with major implications for all healthcare domains.” 26

- EXAMPLE 4. Statistical hypothesis (quantitative research)

- - An assumption is made about the relationship among several population characteristics ( gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults with ADHD ). Validity is tested by statistical experiment or analysis ( chi-square test, Students t-test, and logistic regression analysis)

- “Our research investigated gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults with ADHD in a Japanese clinical sample. Due to unique Japanese cultural ideals and expectations of women's behavior that are in opposition to ADHD symptoms, we hypothesized that women with ADHD experience more difficulties and present more dysfunctions than men . We tested the following hypotheses: first, women with ADHD have more comorbidities than men with ADHD; second, women with ADHD experience more social hardships than men, such as having less full-time employment and being more likely to be divorced.” 27

- “Statistical Analysis

- ( text omitted ) Between-gender comparisons were made using the chi-squared test for categorical variables and Students t-test for continuous variables…( text omitted ). A logistic regression analysis was performed for employment status, marital status, and comorbidity to evaluate the independent effects of gender on these dependent variables.” 27

EXAMPLES OF HYPOTHESIS AS WRITTEN IN PUBLISHED ARTICLES IN RELATION TO OTHER PARTS

- EXAMPLE 1. Background, hypotheses, and aims are provided

- “Pregnant women need skilled care during pregnancy and childbirth, but that skilled care is often delayed in some countries …( text omitted ). The focused antenatal care (FANC) model of WHO recommends that nurses provide information or counseling to all pregnant women …( text omitted ). Job aids are visual support materials that provide the right kind of information using graphics and words in a simple and yet effective manner. When nurses are not highly trained or have many work details to attend to, these job aids can serve as a content reminder for the nurses and can be used for educating their patients (Jennings, Yebadokpo, Affo, & Agbogbe, 2010) ( text omitted ). Importantly, additional evidence is needed to confirm how job aids can further improve the quality of ANC counseling by health workers in maternal care …( text omitted )” 28

- “ This has led us to hypothesize that the quality of ANC counseling would be better if supported by job aids. Consequently, a better quality of ANC counseling is expected to produce higher levels of awareness concerning the danger signs of pregnancy and a more favorable impression of the caring behavior of nurses .” 28

- “This study aimed to examine the differences in the responses of pregnant women to a job aid-supported intervention during ANC visit in terms of 1) their understanding of the danger signs of pregnancy and 2) their impression of the caring behaviors of nurses to pregnant women in rural Tanzania.” 28

- EXAMPLE 2. Background, hypotheses, and aims are provided

- “We conducted a two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate and compare changes in salivary cortisol and oxytocin levels of first-time pregnant women between experimental and control groups. The women in the experimental group touched and held an infant for 30 min (experimental intervention protocol), whereas those in the control group watched a DVD movie of an infant (control intervention protocol). The primary outcome was salivary cortisol level and the secondary outcome was salivary oxytocin level.” 29

- “ We hypothesize that at 30 min after touching and holding an infant, the salivary cortisol level will significantly decrease and the salivary oxytocin level will increase in the experimental group compared with the control group .” 29

- EXAMPLE 3. Background, aim, and hypothesis are provided

- “In countries where the maternal mortality ratio remains high, antenatal education to increase Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness (BPCR) is considered one of the top priorities [1]. BPCR includes birth plans during the antenatal period, such as the birthplace, birth attendant, transportation, health facility for complications, expenses, and birth materials, as well as family coordination to achieve such birth plans. In Tanzania, although increasing, only about half of all pregnant women attend an antenatal clinic more than four times [4]. Moreover, the information provided during antenatal care (ANC) is insufficient. In the resource-poor settings, antenatal group education is a potential approach because of the limited time for individual counseling at antenatal clinics.” 30

- “This study aimed to evaluate an antenatal group education program among pregnant women and their families with respect to birth-preparedness and maternal and infant outcomes in rural villages of Tanzania.” 30

- “ The study hypothesis was if Tanzanian pregnant women and their families received a family-oriented antenatal group education, they would (1) have a higher level of BPCR, (2) attend antenatal clinic four or more times, (3) give birth in a health facility, (4) have less complications of women at birth, and (5) have less complications and deaths of infants than those who did not receive the education .” 30

Research questions and hypotheses are crucial components to any type of research, whether quantitative or qualitative. These questions should be developed at the very beginning of the study. Excellent research questions lead to superior hypotheses, which, like a compass, set the direction of research, and can often determine the successful conduct of the study. Many research studies have floundered because the development of research questions and subsequent hypotheses was not given the thought and meticulous attention needed. The development of research questions and hypotheses is an iterative process based on extensive knowledge of the literature and insightful grasp of the knowledge gap. Focused, concise, and specific research questions provide a strong foundation for constructing hypotheses which serve as formal predictions about the research outcomes. Research questions and hypotheses are crucial elements of research that should not be overlooked. They should be carefully thought of and constructed when planning research. This avoids unethical studies and poor outcomes by defining well-founded objectives that determine the design, course, and outcome of the study.

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions:

- Conceptualization: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Methodology: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Writing - original draft: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Writing - review & editing: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

Principles of Social Research Methodology pp 257–260 Cite as