- Open access

- Published: 20 June 2023

A qualitative quantitative mixed methods study of domestic violence against women

- Mina Shayestefar 1 ,

- Mohadese Saffari 1 ,

- Razieh Gholamhosseinzadeh 2 ,

- Monir Nobahar 3 , 4 ,

- Majid Mirmohammadkhani 4 ,

- Seyed Hossein Shahcheragh 5 &

- Zahra Khosravi 6

BMC Women's Health volume 23 , Article number: 322 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

6912 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Violence against women is one of the most widespread, persistent and detrimental violations of human rights in today’s world, which has not been reported in most cases due to impunity, silence, stigma and shame, even in the age of social communication. Domestic violence against women harms individuals, families, and society. The objective of this study was to investigate the prevalence and experiences of domestic violence against women in Semnan.

This study was conducted as mixed research (cross-sectional descriptive and phenomenological qualitative methods) to investigate domestic violence against women, and some related factors (quantitative) and experiences of such violence (qualitative) simultaneously in Semnan. In quantitative study, cluster sampling was conducted based on the areas covered by health centers from married women living in Semnan since March 2021 to March 2022 using Domestic Violence Questionnaire. Then, the obtained data were analyzed by descriptive and inferential statistics. In qualitative study by phenomenological approach and purposive sampling until data saturation, 9 women were selected who had referred to the counseling units of Semnan health centers due to domestic violence, since March 2021 to March 2022 and in-depth and semi-structured interviews were conducted. The conducted interviews were analyzed using Colaizzi’s 7-step method.

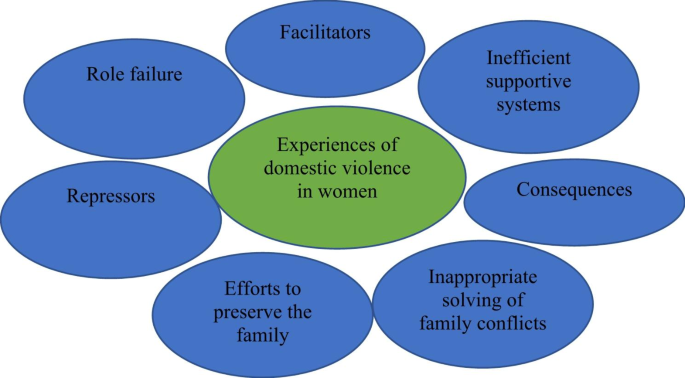

In qualitative study, seven themes were found including “Facilitators”, “Role failure”, “Repressors”, “Efforts to preserve the family”, “Inappropriate solving of family conflicts”, “Consequences”, and “Inefficient supportive systems”. In quantitative study, the variables of age, age difference and number of years of marriage had a positive and significant relationship, and the variable of the number of children had a negative and significant relationship with the total score and all fields of the questionnaire (p < 0.05). Also, increasing the level of female education and income both independently showed a significant relationship with increasing the score of violence.

Conclusions

Some of the variables of violence against women are known and the need for prevention and plans to take action before their occurrence is well felt. Also, supportive mechanisms with objective and taboo-breaking results should be implemented to minimize harm to women, and their children and families seriously.

Peer Review reports

Violence against women by husbands (physical, sexual and psychological violence) is one of the basic problems of public health and violation of women’s human rights. It is estimated that 35% of women and almost one out of every three women aged 15–49 experience physical or sexual violence by their spouse or non-spouse sexual violence in their lifetime [ 1 ]. This is a nationwide public health issue, and nearly every healthcare worker will encounter a patient who has suffered from some type of domestic or family violence. Unfortunately, different forms of family violence are often interconnected. The “cycle of abuse” frequently persists from children who witness it to their adult relationships, and ultimately to the care of the elderly [ 2 ]. This violence includes a range of physical, sexual and psychological actions, control, threats, aggression, abuse, and rape [ 3 ].

Violence against women is one of the most widespread, persistent, and detrimental violations of human rights in today’s world, which has not been reported in most cases due to impunity, silence, stigma and shame, even in the age of social communication [ 3 ]. In the United States of America, more than one in three women (35.6%) experience rape, physical violence, and intimate partner violence (IPV) during their lifetime. Compared to men, women are nearly twice as likely (13.8% vs. 24.3%) to experience severe physical violence such as choking, burns, and threats with knives or guns [ 4 ]. The higher prevalence of violence against women can be due to the situational deprivation of women in patriarchal societies [ 5 ]. The prevalence of domestic violence in Iran reported 22.9%. The maximum of prevalence estimated in Tehran and Zahedan, respectively [ 6 ]. Currently, Iran has high levels of violence against women, and the provinces with the highest rates of unemployment and poverty also have the highest levels of violence against women [ 7 ].

Domestic violence against women harms individuals, families, and society [ 8 ]. Violence against women leads to physical, sexual, psychological harm or suffering, including threats, coercion and arbitrary deprivation of their freedom in public and private life. Also, such violence is associated with harmful effects on women’s sexual reproductive health, including sexually transmitted infection such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), abortion, unsafe childbirth, and risky sexual behaviors [ 9 ]. There are high levels of psychological, sexual and physical domestic abuse among pregnant women [ 10 ]. Also, women with postpartum depression are significantly more likely to experience domestic violence during pregnancy [ 11 ].

Prompt attention to women’s health and rights at all levels is necessary, which reduces this problem and its risk factors [ 12 ]. Because women prefer to remain silent about domestic violence and there is a need to introduce immediate prevention programs to end domestic violence [ 13 ]. violence against women, which is an important public health problem, and concerns about human rights require careful study and the application of appropriate policies [ 14 ]. Also, the efforts to change the circumstances in which women face domestic violence remain significantly insufficient [ 15 ]. Given that few clear studies on violence against women and at the same time interviews with these people regarding their life experiences are available, the authors attempted to planning this research aims to investigate the prevalence and experiences of domestic violence against women in Semnan with the research question of “What is the prevalence of domestic violence against women in Semnan, and what are their experiences of such violence?”, so that their results can be used in part of the future planning in the health system of the society.

This study is a combination of cross-sectional and phenomenology studies in order to investigate the amount of domestic violence against women and some related factors (quantitative) and their experience of this violence (qualitative) simultaneously in the Semnan city. This study has been approved by the ethics committee of Semnan University of Medical Sciences with ethic code of IR.SEMUMS.REC.1397.182. The researcher introduced herself to the research participants, explained the purpose of the study, and then obtained informed written consent. It was assured to the research units that the collected information will be anonymous and kept confidential. The participants were informed that participation in the study was entirely voluntary, so they can withdraw from the study at any time with confidence. The participants were notified that more than one interview session may be necessary. To increase the trustworthiness of the study, Guba and Lincoln’s criteria for rigor, including credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability [ 16 ], were applied throughout the research process. The COREQ checklist was used to assess the present study quality. The researchers used observational notes for reflexivity and it preserved in all phases of this qualitative research process.

Qualitative method

Based on the phenomenological approach and with the purposeful sampling method, nine women who had referred to the counseling units of healthcare centers in Semnan city due to domestic violence in February 2021 to March 2022 were participated in the present study. The inclusion criteria for the study included marriage, a history of visiting a health center consultant due to domestic violence, and consent to participate in the study and unwillingness to participate in the study was the exclusion criteria. Each participant invited to the study by a telephone conversation about study aims and researcher information. The interviews place selected through agreement of the participant and the researcher and a place with the least environmental disturbance. Before starting each interview, the informed consent and all of the ethical considerations, including the purpose of the research, voluntary participation, confidentiality of the information were completely explained and they were asked to sign the written consent form. The participants were interviewed by depth, semi-structured and face-to-face interviews based on the main research question. Interviews were conducted by a female health services researcher with a background in nursing (M.Sh.). Data collection was continued until the data saturation and no new data appeared. Only the participants and the researcher were present during the interviews. All interviews were recorded by a MP3 Player by permission of the participants before starting. Interviews were not repeated. No additional field notes were taken during or after the interview.

The age range of the participants was from 38 to 55 years and their average age was 40 years. The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in table below (Table 1 ).

Five interviews in the courtyards of healthcare centers, 2 interviews in the park, and 2 interviews at the participants’ homes were conducted. The duration of the interviews varied from 45 min to one hour. The main research question was “What is your experience about domestic violence?“. According to the research progress some other questions were asked in line with the main question of the research.

The conducted interviews were analyzed by using the 7 steps Colizzi’s method [ 17 ]. In order to empathize with the participants, each interview was read several times and transcribed. Then two researchers (M.Sh. and M.N.) extracted the phrases that were directly related to the phenomenon of domestic violence against women independently and distinguished from other sentences by underlining them. Then these codes were organized into thematic clusters and the formulated concepts were sorted into specific thematic categories.

In the final stage, in order to make the data reliable, the researcher again referred to 2 participants and checked their agreement with their perceptions of the content. Also, possible important contents were discussed and clarified, and in this way, agreement and approval of the samples was obtained.

Quantitative method

The cross-sectional study was implemented from February 2021 to March 2022 with cluster sampling of married women in areas of 3 healthcare centers in Semnan city. Those participants who were married and agreed with the written and verbal informed consent about the ethical considerations were included to the study. The questionnaire was completed by the participants in paper and online form.

The instrument was the standard questionnaire of domestic violence against women by Mohseni Tabrizi et al. [ 18 ]. In the questionnaire, questions 1–10, 11–36, 37–65 and 66–71 related to sociodemographic information, types of spousal abuse (psychological, economical, physical and sexual violence), patriarchal beliefs and traditions and family upbringing and learning violence, respectively. In total, this questionnaire has 71 items.

The scoring of the questionnaire has two parts and the answers to them are based on the Likert scale. Questions 11–36 and 66–71 are answered with always [ 4 ] to never (0) and questions 37–65 with completely agree [ 4 ] to completely disagree (0). The minimum and maximum score is 0 and 300, respectively. The total score of 0–60, 61–120 and higher than 121 demonstrates low, moderate and severe domestic violence against women, respectively [ 18 ].

In the study by Tabrizi et al., to evaluate the validity and reliability of this questionnaire, researchers tried to measure the face validity of the scale by the previous research. Those items and questions which their accuracies were confirmed by social science professors and experts used in the research, finally. The total Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.183, which confirmed that the reliability of the questions and items of the questionnaire is sufficient [ 18 ].

Descriptive data were reported using mean, standard deviation, frequency and percentage. Then, to measure the relationship between the variables, χ2 and Pearson tests also variance and regression analysis were performed. All analysis were performed by using SPSS version 26 and the significance level was considered as p < 0.05.

Qualitative results

According to the third step of Colaizzi’s 7-step method, the researcher attempted to conceptualize and formulate the extracted meanings. In this step, the primary codes were extracted from the important sentences related to the phenomenon of violence against women, which were marked by underlining, which are shown below as examples of this stage and coding.

The primary code of indifference to the father’s role was extracted from the following sentences. This is indifference in the role of the father in front of the children.

“Some time ago, I told him that our daughter is single-sided deaf. She has a doctor’s appointment; I have to take her to the doctor. He said that I don’t have money to give you. He doesn’t force himself to make money anyway” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“He didn’t value his own children. He didn’t think about his older children” (p 4, 54 yrs).

The primary code extracted here included lack of commitment in the role of head of the household. This is irresponsibility towards the family and meeting their needs.

“My husband was fired from work after 10 years due to disorder and laziness. Since then, he has not found a suitable job. Every time he went to work, he was fired after a month because of laziness” (p 7, 55 yrs).

“In the evening, he used to get dressed and go out, and he didn’t come back until late. Some nights, I was so afraid of being alone that I put a knife under my pillow when I slept” (p 2, 33 yrs).

A total of 246 primary codes were extracted from the interviews in the third step. In the fourth step, the researchers put the formulated concepts (primary codes) into 85 specific sub-categories.

Twenty-three categories were extracted from 85 sub-categories. In the sixth step, the concepts of the fifth step were integrated and formed seven themes (Table 2 ).

These themes included “Facilitators”, “Role failure”, “Repressors”, “Efforts to preserve the family”, “Inappropriate solving of family conflicts”, “Consequences”, and “Inefficient supportive systems” (Fig. 1 ).

Themes of domestic violence against women

Some of the statements of the participants on the theme of “ Facilitators” are listed below:

Husband’s criminal record

“He got his death sentence for drugs. But, at last it was ended for 10 years” (p 4, 54 yrs).

Inappropriate age for marriage

“At the age of thirteen, I married a boy who was 25 years old” (p 8, 25 yrs).

“My first husband obeyed her parents. I was 12–13 years old” (p 3, 32 yrs).

“I couldn’t do anything. I was humiliated” (p 1, 38 yrs).

“A bridegroom came. The mother was against. She said, I am young. My older sister is not married yet, but I was eager to get married. I don’t know, maybe my father’s house was boring for me” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“My parents used to argue badly. They blamed each other and I always wanted to run away from these arguments. I didn’t have the patience to talk to mom or dad and calm them down” (p 5, 39 yrs).

Overdependence

“My husband’s parents don’t stop interfering, but my husband doesn’t say anything because he is a student of his father. My husband is self-employed and works with his father on a truck” (p 8, 25 yrs).

“Every time I argue with my husband because of lack of money, my mother-in-law supported her son and brought him up very spoiled and lazy” (p 7, 55 yrs).

Bitter memories

“After three years, my mother married her friend with my uncle’s insistence and went to Shiraz. But, his condition was that she did not have the right to bring his daughter with her. In fact, my mother also got married out of necessity” (p 8, 25 yrs).

Some of their other statements related to “ Role failure” are mentioned below:

Lack of commitment to different roles

“I got angry several times and went to my father’s house because of my husband’s bad financial status and the fact that he doesn’t feel responsible to work and always says that he cannot find a job” (p 6, 48 yrs).

“I saw that he does not want to change in any way” (p 4, 54 yrs).

“No matter how kind I am, it does not work” (p 1, 38 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding “ Repressors” are listed below:

Fear and silence

“My mother always forced me to continue living with my husband. Finally, my father had been poor. She all said that you didn’t listen to me when you wanted to get married, so you don’t have the right to get angry and come to me, I’m miserable enough” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“Because I suffered a lot in my first marital life. I was very humiliated. I said I would be fine with that. To be kind” (p1, 38 yrs).

“Well, I tell myself that he gets angry sometimes” (p 3, 32 yrs).

Shame from society

“I don’t want my daughter-in-law to know. She is not a relative” (p 4, 54 yrs).

Some of the statements of the participants regarding the theme of “ Efforts to preserve the family” are listed below:

Hope and trust

“I always hope in God and I am patient” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Efforts for children

“My divorce took a month. We got a divorce. I forgave my dowry and took my children instead” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding the “ Inappropriate solving of family conflicts” are listed below:

Child-bearing thoughts

“My husband wanted to take me to a doctor to treat me. But my father-in-law refused and said that instead of doing this and spending money, marry again. Marriage in the clans was much easier than any other work” (p 8, 25 yrs).

Lack of effective communication

“I was nervous about him, but I didn’t say anything” (p 5, 39 yrs).

“Now I am satisfied with my life and thank God it is better to listen to people’s words. Now there is someone above me so that people don’t talk behind me” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding the “ Consequences” are listed below:

Harm to children

“My eldest daughter, who was about 7–8 years old, behaved differently. Oh, I was angry. My children are mentally depressed and argue” (p 5, 39 yrs).

After divorce

“Even though I got a divorce, my mother and I came to a remote area due to the fear of what my family would say” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Social harm

“I work at a retirement center for living expenses” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“I had to go to clean the houses” (p 5, 39 yrs).

Non-acceptance in the family

“The children’s relationship with their father became bad. Because every time they saw their father sitting at home smoking, they got angry” (p 7, 55 yrs).

Emotional harm

“When I look back, I regret why I was not careful in my choice” (p 7, 55 yrs).

“I felt very bad. For being married to a man who is not bound by the family and is capricious” (p 9, 36 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding “ Inefficient supportive systems” are listed below:

Inappropriate family support

“We didn’t have children. I was at my father’s house for about a month. After a month, when I came home, I saw that my husband had married again. I cried a lot that day. He said, God, I had to. I love you. My heart is broken, I have no one to share my words” (p 8, 25 yrs).

“My brother-in-law was like himself. His parents had also died. His sister did not listen at all” (p 4, 54 yrs).

“I didn’t have anyone and I was alone” (p 1, 38 yrs).

Inefficiency of social systems

“That day he argued with me, picked me up and threw me down some stairs in the middle of the yard. He came closer, sat on my stomach, grabbed my neck with both of his hands and wanted to strangle me. Until a long time later, I had kidney problems and my neck was bruised by her hand. Given that my aunt and her family were with us in a building, but she had no desire to testify and was afraid” (p 3, 32 yrs).

Undesired training and advice

“I told my mother, you just said no, how old I was? You never insisted on me and you didn’t listen to me that this man is not good for you” (p 9, 36 yrs).

Quantitative results

In the present study, 376 married women living in Semnan city participated in this study. The mean age of participants was 38.52 ± 10.38 years. The youngest participant was 18 and the oldest was 73 years old. The maximum age difference was 16 years. The years of marriage varied from one year to 40 years. Also, the number of children varied from no children to 7. The majority of them had 2 children (109, 29%). The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in the table below (Table 3 ).

The frequency distribution (number and percentage) of the participants in terms of the level of violence was as follows. 89 participants (23.7%) had experienced low violence, 59 participants (15.7%) had experienced moderate violence, and 228 participants (60.6%) had experienced severe violence.

Cronbach’s alpha for the reliability of the questionnaire was 0.988. The mean and standard deviation of the total score of the questionnaire was 143.60 ± 74.70 with a range of 3-244. The relationship between the total score of the questionnaire and its fields, and some demographic variables is summarized in the table below (Table 4 ).

As shown in the table above, the variables of age, age difference and number of years of marriage have a positive and significant relationship, and the variable of number of children has a negative and significant relationship with the total score and all fields of the questionnaire (p < 0.05). However, the variable of education level difference showed no significant relationship with the total score and any of the fields. Also, the highest average score is related to patriarchal beliefs compared to other fields.

The comparison of the average total scores separately according to each variable showed the significant average difference in the variables of the previous marriage history of the woman, the result of the previous marriage of the woman, the education of the woman, the education of the man, the income of the woman, the income of the man, and the physical disease of the man (p < 0.05).

In the regression model, two variables remained in the final model, indicating the relationship between the variables and violence score and the importance of these two variables. An increase in women’s education and income level both independently show a significant relationship with an increase in violence score (Table 5 ).

The results of analysis of variance to compare the scores of each field of violence in the subgroups of the participants also showed that the experience and result of the woman’s previous marriage has a significant relationship with physical violence and tradition and family upbringing, the experience of the man’s previous marriage has a significant relationship with patriarchal belief, the education level of the woman has a significant relationship with all fields and the level of education of the man has a significant relationship with all fields except tradition and family upbringing (p < 0.05).

According to the results of both quantitative and qualitative studies, variables such as the young age of the woman and a large age difference are very important factors leading to an increase in violence. At a younger age, girls are afraid of the stigma of society and family, and being forced to remain silent can lead to an increase in domestic violence. As Gandhi et al. (2021) stated in their study in the same field, a lower marriage age leads to many vulnerabilities in women. Early marriage is a global problem associated with a wide range of health and social consequences, including violence for adolescent girls and women [ 12 ]. Also, Ahmadi et al. (2017) found similar findings, reporting a significant association among IPV and women age ≤ 40 years [ 19 ].

Two others categories of “Facilitators” in the present study were “Husband’s criminal record” and “Overdependence” which had a sub-category of “Forced cohabitation”. Ahmadi et al. (2017) reported in their population-based study in Iran that husband’s addiction and rented-householders have a significant association with IPV [ 19 ].

The patriarchal beliefs, which are rooted in the tradition and culture of society and family upbringing, scored the highest in relation to domestic violence in this study. On the other hand, in qualitative study, “Normalcy” of men’s anger and harassment of women in society is one of the “Repressors” of women to express violence. In the quantitative study, the increase in the women’s education and income level were predictors of the increase in violence. Although domestic violence is more common in some sections of society, women with a wide range of ages, different levels of education, and at different levels of society face this problem, most of which are not reported. Bukuluki et al. (2021) showed that women who agreed that it is good for a man to control his partner were more likely to experience physical violence [ 20 ].

Domestic violence leads to “Consequences” such as “Harm to children”, “Emotional harm”, “Social harm” to women and even “Non-acceptance in their own family”. Because divorce is a taboo in Iranian culture and the fear of humiliating women forces them to remain silent against domestic violence. Balsarkar (2021) stated that the fear of violence can prevent women from continuing their studies, working or exercising their political rights [ 8 ]. Also, Walker-Descarte et al. (2021) recognized domestic violence as a type of child maltreatment, and these abusive behaviors are associated with mental and physical health consequences [ 21 ].

On the other hand and based on the “Lack of effective communication” category, ignoring the role of the counselor in solving family conflicts and challenges in the life of couples in the present study was expressed by women with reasons such as lack of knowledge and family resistance to counseling. Several pathologies are needed to investigate increased domestic violence in situations such as during women’s pregnancy or infertility. Because the use of counseling for couples as a suitable solution should be considered along with their life challenges. Lin et al. (2022) stated that pregnant women were exposed to domestic violence for low birth weight in full term delivery. Spouse violence screening in the perinatal health care system should be considered important, especially for women who have had full-term low birth weight infants [ 22 ].

Also, lack of knowledge and low level of education have been found as other factors of violence in this study, which is very prominent in both qualitative and quantitative studies. Because the social systems and information about the existing laws should be followed properly in society to act as a deterrent. Psychological training and especially anger control and resilience skills during education at a younger age for girls and boys should be included in educational materials to determine the positive results in society in the long term. Manouchehri et al. (2022) stated that it seems necessary to train men about the negative impact of domestic violence on the current and future status of the family [ 23 ]. Balsarkar (2021) also stated that men and women who have not had the opportunity to question gender roles, attitudes and beliefs cannot change such things. Women who are unaware of their rights cannot claim. Governments and organizations cannot adequately address these issues without access to standards, guidelines and tools [ 8 ]. Machado et al. (2021) also stated that gender socialization reinforces gender inequalities and affects the behavior of men and women. So, highlighting this problem in different fields, especially in primary health care services, is a way to prevent IPV against women [ 24 ].

There was a sub-category of “Inefficiency of social systems” in the participants experiences. Perhaps the reason for this is due to insufficient education and knowledge, or fear of seeking help. Holmes et al. (2022) suggested the importance of ascertaining strategies to improve victims’ experiences with the court, especially when victims’ requests are not met, to increase future engagement with the system [ 25 ]. Sigurdsson (2019) revealed that despite high prevalence numbers, IPV is still a hidden and underdiagnosed problem and neither general practitioner nor our communities are as well prepared as they should be [ 26 ]. Moreira and Pinto da Costa (2021) found that while victims of domestic violence often agree with mandatory reporting, various concerns are still expressed by both victims and healthcare professionals that require further attention and resolution [ 27 ]. It appears that legal and ethical issues in this regard require comprehensive evaluation from the perspectives of victims, their families, healthcare workers, and legal experts. By doing so, better practical solutions can be found to address domestic violence, leading to a downward trend in its occurrence.

Some of the variables of violence against women have been identified and emphasized in many studies, highlighting the necessity of policymaking and social pathology in society to prevent and use operational plans to take action before their occurrence. Breaking the taboo of domestic violence and promoting divorce as a viable solution after counseling to receive objective results should be implemented seriously to minimize harm to women, children, and their families.

Limitations

Domestic violence against women is an important issue in Iranian society that women resist showing and expressing, making researchers take a long-term process of sampling in both qualitative and quantitative studies. The location of the interview and the women’s fear of their husbands finding out about their participation in this study have been other challenges of the researchers, which, of course, they attempted to minimize by fully respecting ethical considerations. Despite the researchers’ efforts, their personal and professional experiences, as well as the studies reviewed in the literature review section, may have influenced the study results.

Data Availability

Data and materials will be available upon email to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

Intimate Partner Violence

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Organization WH. Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. World Health Organization; 2021.

Huecker MR, Malik A, King KC, Smock W. Kentucky Domestic Violence. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Ahmad Malik declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Kevin King declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: William Smock declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.: StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2023.

Gandhi A, Bhojani P, Balkawade N, Goswami S, Kotecha Munde B, Chugh A. Analysis of survey on violence against women and early marriage: Gyneaecologists’ perspective. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2021;71(Suppl 2):76–83.

Article Google Scholar

Sugg N. Intimate partner violence: prevalence, health consequences, and intervention. Med Clin. 2015;99(3):629–49.

Google Scholar

Abebe Abate B, Admassu Wossen B, Tilahun Degfie T. Determinants of intimate partner violence during pregnancy among married women in Abay Chomen district, western Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2016;16(1):1–8.

Adineh H, Almasi Z, Rad M, Zareban I, Moghaddam A. Prevalence of domestic violence against women in Iran: a systematic review. Epidemiol (Sunnyvale). 2016;6(276):2161–11651000276.

Pirnia B, Pirnia F, Pirnia K. Honour killings and violence against women in Iran during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):e60.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Balsarkar G. Summary of four recent studies on violence against women which obstetrician and gynaecologists should know. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2021;71:64–7.

Ellsberg M, Jansen HA, Heise L, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C. Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: an observational study. The lancet. 2008;371(9619):1165–72.

Chasweka R, Chimwaza A, Maluwa A. Isn’t pregnancy supposed to be a joyful time? A cross-sectional study on the types of domestic violence women experience during pregnancy in Malawi. Malawi Med journal: J Med Association Malawi. 2018;30(3):191–6.

Afshari P, Tadayon M, Abedi P, Yazdizadeh S. Prevalence and related factors of postpartum depression among reproductive aged women in Ahvaz. Iran Health care women Int. 2020;41(3):255–65.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gebrezgi BH, Badi MB, Cherkose EA, Weldehaweria NB. Factors associated with intimate partner physical violence among women attending antenatal care in Shire Endaselassie town, Tigray, northern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study, July 2015. Reproductive health. 2017;14:1–10.

Duran S, Eraslan ST. Violence against women: affecting factors and coping methods for women. J Pak Med Assoc. 2019;69(1):53–7.

PubMed Google Scholar

Devries KM, Mak JY, Garcia-Moreno C, Petzold M, Child JC, Falder G, et al. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science. 2013;340(6140):1527–8.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Mahapatro M, Kumar A. Domestic violence, women’s health, and the sustainable development goals: integrating global targets, India’s national policies, and local responses. J Public Health Policy. 2021;42(2):298–309.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry: sage; 1985.

Colaizzi PF. Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. 1978.

Mohseni Tabrizi A, Kaldi A, Javadianzadeh M. The study of domestic violence in Marrid Women Addmitted to Yazd Legal Medicine Organization and Welfare Organization. Tolooebehdasht. 2013;11(3):11–24.

Ahmadi R, Soleimani R, Jalali MM, Yousefnezhad A, Roshandel Rad M, Eskandari A. Association of intimate partner violence with sociodemographic factors in married women: a population-based study in Iran. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22(7):834–44.

Bukuluki P, Kisaakye P, Wandiembe SP, Musuya T, Letiyo E, Bazira D. An examination of physical violence against women and its justification in development settings in Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(9):e0255281.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Walker-Descartes I, Mineo M, Condado LV, Agrawal N. Domestic violence and its Effects on Women, Children, and families. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2021;68(2):455–64.

Lin C-H, Lin W-S, Chang H-Y, Wu S-I. Domestic violence against pregnant women is a potential risk factor for low birthweight in full-term neonates: a population-based retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(12):e0279469.

Manouchehri E, Ghavami V, Larki M, Saeidi M, Latifnejad Roudsari R. Domestic violence experienced by women with multiple sclerosis: a study from the North-East of Iran. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):1–14.

Machado DF, Castanheira ERL, Almeida MASd. Intersections between gender socialization and violence against women by the intimate partner. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2021;26:5003–12.

Holmes SC, Maxwell CD, Cattaneo LB, Bellucci BA, Sullivan TP. Criminal Protection orders among women victims of intimate Partner violence: Women’s Experiences of Court decisions, processes, and their willingness to Engage with the system in the future. J interpers Violence. 2022;37(17–18):Np16253–np76.

Sigurdsson EL. Domestic violence-are we up to the task? Scand J Prim Health Care. 2019;37(2):143–4.

Moreira DN, Pinto da Costa M. Should domestic violence be or not a public crime? J Public Health. 2021;43(4):833–8.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study appreciate the Deputy for Research and Technology of Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Social Determinants of Health Research Center of Semnan University of Medical Sciences and all the participants in this study.

Research deputy of Semnan University of Medical Sciences financially supported this project.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Allied Medical Sciences, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Mina Shayestefar & Mohadese Saffari

Amir Al Momenin Hospital, Social Security Organization, Ahvaz, Iran

Razieh Gholamhosseinzadeh

Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Monir Nobahar

Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Monir Nobahar & Majid Mirmohammadkhani

Clinical Research Development Unit, Kowsar Educational, Research and Therapeutic Hospital, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Seyed Hossein Shahcheragh

Student Research Committee, School of Allied Medical Sciences, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Zahra Khosravi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

M.Sh. contributed to the first conception and design of this research; M.Sh., Z.Kh., M.S., R.Gh. and S.H.Sh. contributed to collect data; M.N. and M.Sh. contributed to the analysis of the qualitative data; M.M. and M.Sh. contributed to the analysis of the quantitative data; M.SH., M.N. and M.M. contributed to the interpretation of the data; M.Sh., M.S. and S.H.Sh. wrote the manuscript. M.Sh. prepared the final version of manuscript for submission. All authors reviewed the manuscript meticulously and approved it. All names of the authors were listed in the title page.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mina Shayestefar .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This article is resulted from a research approved by the Vice Chancellor for Research of Semnan University of Medical Sciences with ethics code of IR.SEMUMS.REC.1397.182 in the Social Determinants of Health Research Center. The authors confirmed that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants accepted the participation in the present study. The researchers introduced themselves to the research units, explained the purpose of the research to them and then all participants signed the written informed consent. The research units were assured that the collected information was anonymous. The participant was informed that participating in the study was completely voluntary so that they can safely withdraw from the study at any time and also the availability of results upon their request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Shayestefar, M., Saffari, M., Gholamhosseinzadeh, R. et al. A qualitative quantitative mixed methods study of domestic violence against women. BMC Women's Health 23 , 322 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02483-0

Download citation

Received : 28 April 2023

Accepted : 14 June 2023

Published : 20 June 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02483-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Domestic violence

- Cross-sectional studies

- Qualitative research

BMC Women's Health

ISSN: 1472-6874

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Lauren Isaac, MSW

Domestic Violence in Families: Theory, Effects, and Intervention

If a person experiences trauma; specifically that of domestic violence, either directly or vicariously (indirectly) from a young age, they do not properly pass though the appropriate developmental stages. This will hinder their emotional growth—causing them to remain stuck in one particular stage. Therefore, this child will not develop and maintain a normal level of trust in his/her parents because they will not feel the appropriate amount of safety in their environment. This alone, will affect how the family members relate to one another from that point on and will put the child at a disadvantage because they will be unable to form healthy relationships with those outside the family system as well. Depending on the frequency, intensity, and duration of the violence, these effects may be life-altering, devastating, and last for many years to come.

A child who experiences this type of trauma at a young age, will not have an appropriately developed brain. This idea suggests that there will be significant differences between the brain of child who has grown up or is currently growing up in a loving, supportive, and caring environment, and the brain of a child who is witnessing domestic violence within their family system, causing them to experience constant fear and inconsistency; hence the inability to grow and thrive. This type of upbringing will cause the child to develop the sense that he/she is in constant danger; also known as the “fight or flight” response; meaning that they will be in a consistent state of hyper vigilance. It is well documented that the cycle of violence is a constant, causing patterns of violence to develop within the family over a period of generations.

Much of the client population we serve in the field of social work, have experienced or at least witnessed some form of violence whether it is indirectly within their neighborhood or directly from someone they know/love or watching someone they love be badly hurt, beaten, or killed. Becoming more knowledgeable of the effects that this trauma has on children and families developmentally as well as socio-emotionally allows us to provide a higher quality of care to our clients and their families.

One of those main ideas is the cycle of violence and what makes a victim consistently return to their abuser; the classic question. It has been relayed to me many times by various professional sources that it takes a woman 5 or 7 times of attempting to leave her abuser, before she will actually not return. (Yamawaki, Ochoa-Shipp, Pulsipher, Harlos & Swindler, 2012) Stemming from this idea, a child being brought up in this violent environment will not develop the same way as a child who is raised in a loving and nurturing environment. I decided I wanted to explore these differences in physical and psychosocial development as a result of experiencing vicarious or direct violence/trauma. I also wanted to look at the short-term as well as the long-term effects of domestic violence on the various family members, emotionally as well as behaviorally. There is quite a bit of speculation regarding the theories of domestic violence as well as the contributing factors and I think that learning more about those would benefit me greatly because I will obtain greater insight on where/how to identify and recognize domestic violence and its effects. Lastly, I believe that it’s vital especially in the social work profession, to possess current and up-to-date information about what services are currently in place and/or are being offered to help individuals and families in domestic violence situations or who have been in the past.

Domestic violence (DV) cuts across all age groups, social classes and travels beyond the extent of physical abuse. It includes emotional abuse including threats, isolation, extreme jealousy and humiliation, and sexual abuse as well. Whenever an individual is placed in a situation involving physical danger or when she is controlled by the threat or use of physical force, this is considered domestic abuse. Domestic violence generally occurs in cycles, requiring the social worker to be able to recognize it so that he/she can intervene appropriately. (“Ohio physicians’ domestic,” 1995) Many barriers exist to identifying DV. Many of these women are either reluctant or unable to get help for themselves and their children. Some may be held captive, while others may be lacking transportation or the financial means to acquire help. (Yamawaki, Ochoa-Shipp, Pulsipher, Harlos & Swindler, 2012)

A woman’s cultural, ethnic, or religious background may also influence her response to the abuse as well as her awareness of viable resources and options. (“Ohio physicians’ domestic,” 1995) In this profession, we are all aware of the immediate effects of DV such as physical injuries. Further research has also shown me that the abused spouse may experience chronic psychosomatic pain or pain due to diffuse trauma without visible evidence. The abused spouse and/or child may develop chronic post-traumatic stress disorder, other anxiety disorders, or depression. These conditions can be recognized by various symptoms including sleep and appetite disturbances, fatigue, decreased concentration, chronic headaches…etc. (“Ohio physicians’ domestic,” 1995) Battered women experiencing PTSD can become entangled in a myriad of symptoms such as avoidance, numbness, fear, and flashbacks; interrupting normal functioning and interfere with adapting coping mechanisms. (Basu, Malone, Levendosky & Dubay, 2009) Psychosomatic complaints are also detected with frequent visits to the physician’s office without evidence of any physiological problems. Suicide rates are also known to be higher in battered women than other women. (“Ohio physicians’ domestic,” 1995)

Some additional psychiatric problems related to the effects of DV include severe and ongoing depression, panic disorder, suicidal tendencies and substance abuse, which may hinder the battered spouse’s ability to appropriately assess her situation and take necessary action. Alcohol and/or drug use is frequently used to rationalize violent behavior. (“Ohio physicians’ domestic,” 1995) The family members affected as well as the abuser may insist that substance abuse is the problem and refuse to place the blame where it belongs. Stressful or violent relationships between adult partners can also lead to an increased sense of negativity in the parent-child dyad and exacerbate the negative effects of exposure; particularly for women with anxiety symptoms or diagnosis of PTSD. (Basu, Malone, Levendosky & Dubay, 2009) According to Systems Theory, a family can be thought of as a system, regarding each member as a subject, mutually influencing each other and displaying patterns and various developmental processes. (Robbins, Chatterjee & Canda, 2012)Each of these members of the family system has a certain level of autonomy and independence but is interdependent by the other subjects to a degree as well; meaning that what affects one family member affects another. (Robbins, Chatterjee & Canda, 2012)

Children are often a factor in the woman’s decision to remain in a violent relationship. An estimated 3.3 million to 10 million children are exposed to domestic violence in their home each year. (Richards, 2011)Children’s exposure to DV and the effects that this exposure can have has been increasingly recognized in recent years. Research even suggests that when a child does not directly witness DV, they may still be negatively affected. (Richards, 2011)The stereotypical view of a child who has witnessed DV between his/her parents is that they are “emotionally traumatized” by the event. There has been much controversy over what “witnessing” DV really means. Research indicates that witnessing DV can involve a broad range of incidents including: hearing the violence, being used as a physical weapon, being forced to watch/participate in the assault, being informed that they are to blame for the violence, being used as a hostage, defending a parent, and/or having to intervene or stop the violence from occurring. Literature also indicates that the aftermath effects for a child include having to see a parent with bruises, see a parent be arrested, having their own injuries and/or the becoming the “parentified” child. Most research conducted on the impacts of childhood exposure to domestic violence focus on the range of psychological and behavioral impacts including but not limited to depression, anxiety, trauma symptoms, increased aggression levels, anti-social behaviors, lower social competence, temperament issues, low self-esteem, dysregulated mood, loneliness and increased likelihood of substance abuse. (Richards, 2011)These children are also at higher risk for school difficulties such as peer conflict or impaired cognitive functioning. Teenage pregnancy, truancy, suicide attempts, and delinquency are also listed as impacts. Long-term physical impacts have rarely been documented, but one study done indicated that children from violent homes are found to have significantly higher heart rates than other children even post-abuse. (Moylan, Herrenkohl, Sousa, Tajima, Herrenkohl & Russo, 2009) Another study found that living in a violent home is a also an attributing factor to a range of serious health conditions as mentioned above such as depression and substance abuse. (Moylan, Herrenkohl, Sousa, Tajima, Herrenkohl & Russo, 2009) Studies have also indicated that children from violent homes may be more likely to exhibit attitudes and behaviors reflecting their childhood experiences witnessing DV. (Richards, 2011) Domestic violence increases a child’s risk for internalizing and externalizing these outcomes during their adolescence. (Moylan, Herrenkohl, Sousa, Tajima, Herrenkohl & Russo, 2009) Research indicates that females are 229% more likely to become victims of DV than their peers from non-violent homes. (Yamawaki, Ochoa-Shipp, Pulsipher, Harlos & Swindler, 2012) In males, the prominent effect of abuse direct or indirect victimization is hyper aggression; suggesting that boys who witness DV or who are somehow involved, are more likely than girl to identify with the aggressor thus eventually perpetuating the abuse on their spouse and/or child. This may justify their own use of violence and or cause them to carry violence-tolerant roles to their adult relationships. (Moylan, Herrenkohl, Sousa, Tajima, Herrenkohl & Russo, 2009)

Based on self-reports from survivors of domestic violence whom I have had the privilege to personally speak to in confidence, I have been able to obtain first-hand information about the effects and devastating impacts of DV. Most of these battered women report having permanent problems with attachment in their personal relationships involving a lack of trust, a lack of ability to soothe their child or to be soothed by another person, difficulty sleeping, self-harm, and a lack of empathy or over-involvement in the distress of others. One of these women explained to me that the DV she experienced at the hands of her ex-husband exacerbated her substance abuse problem; primarily alcoholism. Another woman stated “My son and I haven’t been able to sleep for weeks.” In the brief time spent with these women and their children, I observed an abundance of hypervigilance and inattention. Many of the children appeared to be in the “fight or flight” heightened sense of defensiveness on a consistent basis. A mother’s little boy explained to me that he could no longer trust any man around his mother and that he still has “nightmares about seeing her get beat up and have bruises.” In many of these self-reporting cases, both the mother and her children were exhibiting characteristics of PTSD. Abraham Maslow’s Transpersonal Theory of Self-Actualization and Self-Transcendence Hierarchy of Needs explains that there is an inherent tendency of people to express their innate potentials for love, creativity, and spirituality. According to Maslow, in order for an individual to self-actualize successfully, a nurturing environment, providing all basic needs and social support. A child who is exposed to domestic violence will be unable to establish survival, security, and a sense of being loved, not allowing him the ability to transcend to the higher levels of creativity and spirituality. (Moylan, Herrenkohl, Sousa, Tajima, Herrenkohl & Russo, 2009) These children often grow up and are still unable to move past the level of safety and physiological needs. Each woman that I spoke to across the board reported having selected or continuing to select abusive partners. This leads me to believe that domestic abuse can turn into a pattern. In other words, until the woman is ready to tackle her feelings at the source of her emotional void, she will continue to place herself and her children at risk.

While treating these children in their school environment, I have come to find out that many of their behavioral problems stemmed from feelings of insecure attachment and a lack of sense of safety. Many of them exhibited psychomotor agitation and remained in a consistent, intense emotional state. As I moved through treatment with them and often times their mothers, I came to realize that they were both very distrusting and the child would often have lost his/her ability to “play.” I found myself having to be very creative in play therapy activities with these children because they remained so guarded. Depending on the child’s personality, some of them would internalize these feelings, while others would externalize them. The children who internalized their feelings were quite introverted, rarely socialized with other kids, had a very low self-esteem and were very hypervigilent and sensitive. Externalized behaviors would manifest themselves in more off-task, non-compliant, and defiant/disruptive behaviors. I would usually give these children a diagnosis of Oppositional Defiant Disorder. Many of them had problems with attention and impulse control as well and were given Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. These families usually continued to struggle throughout the course of treatment. Due to many of the mothers’ fear of being alone, they would continue to associate with controlling men because that is what they were accustomed to. I always knew that my number one priority is to the safety and well-being of the child and would do my best to empower them and be consistent in treatment so that they would slowly realize that there are people you can trust. I was able to help a mother find a doctor for her and her son who prescribed her son medication for his ADHD. As a result, his behavior problems at school have greatly decreased and assisted him and his mother in mending their broken relationship. With patience, understanding and attunement, I was able to take most of the children at least one step further than where they started.

The intergenerational transmission of domestic violence has been one of the most commonly reported influences in DV during adulthood. Research conducted on this transmission of DV, further perpetuation the “cycle of violence” is based largely on Social Learning Theory. (McCluskey, 2010) This theory validates that observing violence in one’s home as a child creates ideas and norms about how, when, and toward whom aggression is appropriate. Early studies found a high frequency of violence in families from which the family of origin included domestically violent man/men. A national sample found that exposure to inter-parental spousal DV contributes to the probability for martial aggression for both men and women. (McCluskey, 2010) In aiding victims of domestic violence, the social worker must be able to identify the developmental origins of the client’s struggles and inner-conflicts. Based on an article written by a social work graduate student about her experience interning at a domestic violence shelter, one of her client’s early life was disrupted by an adverse social environment filled with unreliable sources of support and a lack of nurturance. This caused the woman to internally replicate a persistent and pervasive mistrust of others throughout her life, develop a terrible self- of herself as well as negative feelings regarding her external world. (McCluskey, 2010) She had become self-injurious, and she did not develop the ability to care for her children properly, stating that doing for them was “too overwhelming.” This woman’s early object relations have set the tone for her adult patterns of relating to others and her present-day conflicts. As explained in this student’s article, when object relations theory is applied to social work within the context of domestic violence, it illuminates the psychological aspects associated with early relational patterns. (McCluskey, 2010)

Erickson’s Psychosocial Stage 1- Trust versus Mistrust provides that during the years of early infancy, the child must develop a sense of trust for their caregiver. The experience of trauma; specifically domestic violence during this beginning stage, can lead to inadequate emotional development, causing this child to remain at this stage instead of passing through to the appropriate ongoing stages. If this trust is not gained at an early age, the child will grow up anticipating that the world will reflect danger and volatility and that people are not to be trusted. (McCluskey, 2010)

Psychological theories of DV perpetration analyze more individual factors including personality disorders, neurobiological/neuroanatomical factors, disordered or insecure attachment, cognitive distortions, and post-traumatic symptoms as previously stated. (Corvo, Dutton & Chen, 2008)Evidence suggests that violent husbands show more psychological distress, more tendencies to personality disorders, more attachment/dependency issues, a higher tendency towards anger and hostility and more alcohol problems than non-violent men. There is a much larger body of research that examines the relationship between psychological factors and DV in general. (Yamawaki, Ochoa-Shipp, Pulsipher, Harlos & Swindler, 2012)

It is well documented that one of the impacts of prolonged exposure to DV is a decrease in cognitive ability. (Corvo, Dutton & Chen, 2008)The brain stem to the frontal cortex is often negatively impacted. One area of particular importance is the association between frontal lobe deficits and DV. In general, frontal lobe deficits refer to compromised abilities to inhibit impulsivity or aggression or to redirect attention from repetitive behavior. Multi-disciplinary health and development studies have illustrated the factors most closely correlated with DV were associated with general criminal offending, a scope of mental health problems, academic failure, economic resource deficits, and early onset anti-social behavior. (Corvo, Dutton & Chen, 2008)

Attachment Theory suggests that an assaultive male’s violent outbursts may be a form of protest behavior directed at his attachment figure that may have rejected him and/or precipitated by perceived threats of separation or abandonment. (Robbins, Chatterjee & Canda, 2012) Thus, the central features of a fearful attachment pattern are anxiety and anger. Early life separation and loss were strongly correlated with adult DV perpetration as well as exposure to parental violence, validating that insecure attachment style is related to the dis-regulation of the negative flow of emotions in intimate relationships. (Moylan, Herrenkohl, Sousa, Tajima, Herrenkohl & Russo, 2009)

Most group interventions to treat the effects of domestic violence generally focus on male batterers whereas treatment groups for battered women and their children are rare. There are many potential benefits of these interventions for the women and their children such as increasing empowerment, decreasing feelings of isolation, developing interpersonal skills, increasing coping strategies and gaining knowledge of resources. A DV shelter can be the answer in the short-term aftermath of the abuse, as a temporary safe house for the woman and her children where all basic needs are met. While DV shelters often provide counseling and support services for battered women and their children, these programs are typically informal and lack empirical support. (Yamawaki, Ochoa-Shipp, Pulsipher, Harlos & Swindler, 2012) Group intervention for trauma survivors is common, victim-advocacy support groups, as well as Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and other CBT based interventions for both victims/families and their perpetrators. (Yamawaki, Ochoa-Shipp, Pulsipher, Harlos & Swindler, 2012)

The prevalence for minorities to be exposed to domestic violence is much higher than that of the general population. Underlying causes for this include the fact that they are more likely to be poor, allowing them less access to services, they have to endure more foster care changes as well as experience more cumulative effects of DV. (Swartz, 2012) Another statistic shows that more than half of minorities have a diagnosed mental illness, but 75% of them do not receive services within 12 months of receiving a child abuse/neglect investigation. (Swartz, 2012) Several studies conducted on the impact of coordinated community response to DV validate that minority populations are overrepresented in shelter populations; meaning that the current wave of interventions indicate little to no accommodation to the needs of racial minorities. (Swartz, 2012) Historically, the development of the DV shelter movement and community-based interventions emerged from predominantly Caucasian populations with an upper-middle class socioeconomic status. In many ways, the field of Social Work is still lacking culturally competent approaches consistent with creating an environment consistent for helping minority groups succeed in treatment. Studies show that increased cultural sensitivity and an individualized perspective integrating racial and ethnic background is suggested to promote understanding of culturally specific underpinnings of violence and aggression; particularly in the African American and Latino communities. (Swartz, 2012

The first step towards ending family violence is for the victims and their children to be able to engage with practitioners they can trust and whom they can confide in. In order for our profession to remain effective in our work with these vulnerable women and their children, it is essential that we provide culturally and gender-sensitive skills. The social worker often struggles to find a balance between ensuring the safety of the mother and child while simultaneously empowering the mother to do that herself. As far as future directions, I believe that more attention needs to be paid to preventative work. (Keeling & van Wormer, 2011) I think that women survivors of domestic violence can be an excellent source for engaging in DV advocacy leading to improved service provision and policy development. (Barner and Carney, 2011) It is suggesting that by embracing this approach, we can open the door to better engagement with these vulnerable individuals, striving together to ensure safety and increased ability to access service and support. (Barner and Carney, 2011) In terms of prevention, there definitely needs to be more inter-agency coordination when attending to the needs of women and their children. Funding for victim-based services is currently at an all-time low. A stronger need for community-based advocacy needs to be promoted, as well as flexibility in victim informed arrest, prosecution, sentencing, and intervention services. (Barner and Carney, 2011) Unfortunately, the system has become increasingly bureaucratic and punitive, causing women to continuously suffer in silence rather than seek the help that they need. (Keeling & van Wormer, 2011)

In social work practice, social workers and students of social work must continue to work for institutional change in making relationship building with women experiencing DV, a priority. Social work values related to the topic of DV are service (mental health treatment for domestic violence trauma), importance of human relationships (within the family system and larger social environment), dignity and worth of the person (each member of the family), social justice (domestic violence awareness and prevention), and competence (a social worker’s ability to serve this population objectively, professionally, and effectively). I believe the domestic violence training along with integrating policy and decision-making regarding DV services training into social work curriculum. Even for those who are most oppressed such as women, poverty-stricken individuals, those with mental illness, children, and other minorities, there is always an opportunity to act. In conjunction with the values of social work, we should always treat every person as an individual and respect their personal choices, including them in the implementation of their treatment/safety plans as well as continue to support them in obtaining professional and community support, contributing to their healing process.

Robbins, S. P., Chatterjee, P., & Canda, E. R. (2012). Contemporary human behavior theory: A critical perspective for social work . (3rd edition ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education Inc.

The Ohio State Medical Association, The Ohio Department of Human Services-Ohio Domestic Violence Advisory Committee. (1995). Ohio physicians’ domestic violence prevention project: Trust talk- break the silence, begin the cure

Barner, J. R., & Carney, M. M. (2011). Interventions for intimate partner violence: A historical review. Journal of Family Violence , (26), 235-244. doi: 10.1007/s10896-011-9359-3

Basu, A., Malone, J. C., Levendosky, A. A., & Dubay, S. (2009). Longitudinal treatment effectiveness outcomes of a group intervention for women and children exposed to domestic violence. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma , 2 , 90-105. doi: 10.1080/19361520902880715

Corvo, K., Dutton, D., & Chen, W. (2008). Toward evidence-based practice with domestic violence perpetrators. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma , 16 (2), doi: 10.1080/10926770801921246

Keeling, J., & van Wormer, K. (2011). Social worker interventions in situations of domestic violence: What we can learn from our survivors’ personal narratives?. British Journal of Social Work , (42), 1354-1370. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcr137

McCluskey, M. J. (2010). Psychoanalysis and domestic violence: Exploring the application of object relations theory in social work field placement. Clinical Social Work Journal , (38), 435-442. doi: 10.1007/s10615-010-0266-5

Moylan, C. A., Herrenkohl, T. I., Sousa, C., Tajima, E., Herrenkohl, R. C., & Russo, M. J. (2009). The effects of child abuse and exposure to domestic violence on adolescent internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Family Violence , (25), 53-63. doi: 10.1007/s10896-009-9269-9

Richards, K. (2011). Children’s exposure to domestic violence in Australia. Trends and Issues in crime and criminal justice , (419), 1-5.

Yamawaki, N., Ochoa-Shipp, M., Pulsipher, C., Harlos, A., & Swindler, S. (2012). Perceptions of domestic violence: The effects of domestic violence myths, victim’s relationship with her abuser, and the decision to return to her abuser. Journal of Interpersonal Violence , 27 (16), 3195-3212. doi: 10.1177/0886260512441253

In Christine Swartz PCC (Chair). Developmental trauma and its effects on children . (2012).

Our authors want to hear from you! Click to leave a comment

Related posts, subscribe to the sjs weekly newsletter, leave a reply cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Criminal Justice

IResearchNet

Academic Writing Services

Domestic violence theories.

There is no single causal factor related to domestic violence. Rather, scholars have concluded that there are numerous factors that contribute to domestic violence. Feminists found that women were beaten at the hands of their partners. Drawing on feminist theory, they helped explain the relationship between patriarchy and domestic violence. Researchers have examined other theoretical perspectives such as attachment theory, exchange theory, identity theory, the cycle of violence, social learning theory, and victim-blaming theory in explaining domestic violence.

Theories of Domestic Violence:

Attachment theory.

Attachment theory is a useful lens through which to understand perpetrator behavior. It explains how early childhood experiences have led to a particular way of experiencing close relationships. It also helps therapists to see how, depending on the attachment status of the client, interventions will need to be developed to address their specific needs and that cookie cutter approaches will not advance the profession. The attachment findings make it clear that domestic violence is not just a result of social conditioning; if anything, it is at least the interaction between psychological conditioning and the social context. Therefore, while social changes are necessary, violence will never stop as long as the psychological and biological factors are minimized or altogether ignored. Read more about Attachment Theory .

Cycle of Violence

Since the late 1970s, researchers and theorists have focused increased attention on the widespread problem of domestic violence in contemporary society. Research has shown that domestic violence cuts across racial, ethnic, religious, and socioeconomic lines. In particular, researchers have sought to identify the factors associated with intimate violence in an effort to develop theories explaining the causes of battering. One of the most widely cited theories in the domestic violence literature is Lenore Walker’s cycle of violence. According to Walker, the cycle of violence is characterized by three distinct phases which are repeated over and over again in the abusive relationship. As a result, domestic abuse rarely involves a single isolated incident of violence. Rather, the abuse becomes a repetitive pattern in the relationship. Read more about Cycle of Violence .

Exchange Theory

As with the general exchange theory, the key assumption of an exchange theory of family violence is that human interaction is guided by the pursuit of rewards and the avoidance of punishment and costs. Simply stated, individuals will use force and violence in their relationships with intimates and family members if they believe that the rewards of force and violence outweigh the costs of such behavior. A second assumption is that a person who supplies reward services to another obliges the other to fulfill a reciprocal obligation; and thus, the second individual must furnish benefits to the first (Blau 1964). Blau (1964) explains that if reciprocal exchange occurs, the interaction continues. However, if reciprocity is not received, the interaction will be broken off. Of course, family relations, including partner relations, parent–child relations, and sibling relations, are more complex and have a unique social structure compared with the exchanges that typically exist outside of the family. Read more about Exchange Theory .

Identity Theory

Identity theory provides an important avenue for theoretical development in domestic violence research because all behavior, including aggression, is rooted in issues of self and identity. To understand aggression, we need to understand the meanings individuals attribute to themselves in a situation, that is, their self-definitions or identities. In all interactions, the goal of individuals is to confirm their identities. When their identities are not confirmed, persons may control others in the situation to make them respond differently in order to confirm their identities. If control does not work, aggression may be used as a last resort to obtain control and, in turn, confirmation of identity. Thus, identity theory can help explain domestic violence by showing how a lack of identity confirmation at the individual level is tied to the control process and aggression at the interactive level. Read more about Identity Theory .

Social Learning Theory

Social learning theory is one of the most popular explanatory perspectives in the marital violence literature. Often conceptualized as the ‘‘cycle of violence’’ or ‘‘intergenerational transmission theory’’ when applied to the family, the theory states that people model behavior that they have been exposed to as children. Violence is learned through role models provided by the family (parents, siblings, relatives, and boyfriends/girlfriends), either directly or indirectly (i.e., witnessing violence), is reinforced in childhood, and continues in adulthood as a coping response to stress or as a method of conflict resolution. During childhood and adolescence, observations of how parents and significant others behave in intimate relationships provide an initial learning of behavioral alternatives which are ‘‘appropriate’’ for these relationships. Children infer rules or principles through repeated exposure to a particular style of parenting. If the family of origin handled stresses and frustrations with anger and aggression, the child who has grown up in such an environment is at greater risk for exhibiting those same behaviors, witnessed or experienced, as an adult. Gelles (1972) states that ‘‘not only does the family expose individuals to violence and techniques of violence, the family teaches approval for the use of violence.’’ Children learn that violence is acceptable within the home and is an effective method for solving problems or changing the behavior of others. Read more about Social Learning Theory .

Victim-Blaming Theory

Victim-blaming theory describes the practice of holding victims partly responsible for their misfortune. It represents the faulting of individuals who have endured the suffering of crimes, hardships, or other misfortunes with either part or whole responsibility for the event. Often, victim-blaming theories rely on the premise that individuals should recognize the dangers that exist in society and therefore should take the necessary precautions to maintain a certain level of safety. Those who do not take such precautions are perceived as blameworthy for their demise even if they have not acted carelessly. These perceptions in effect shift the culpability away from the perpetrator of the crime onto the victim. When discussing issues of family violence, violence against women, or sexual assault, one often hears victim-blaming statements such as, ‘‘Why didn’t she leave?’’ or ‘‘She was asking for it.’’ Within the context of family violence, victim blaming often includes condemnation of the victim for staying in an abusive relationship. Read more about Victim-Blaming Theory .

General Strain Theory

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 21 June 2023

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Kaitlyn B. Hoover 2

69 Accesses

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Agnew, R. (1992). Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology, 30 (1), 47–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1992.tb01093.x

Article Google Scholar

Agnew, R. (2001). Building on the foundation of general strain theory: Specifying the types of strain most likely to lead to crime and delinquency. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 38 (4), 319. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0022427801038004001

Agnew, R. (2006). Pressured into crime: An overview of general strain theory . Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

Agnew, R. (2011). Crime and time: The temporal patterning of causal variables. Theoretical Criminology, 15 (2), 115. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1362480609356671

Agnew, R. (2013). When criminal coping is likely: An extension of general strain theory. Deviant Behavior, 34 (8), 653–670. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2013.766529

Agnew, R., Matthews, S. K., Bucher, J., Welcher, A. N., & Keyes, C. (2008). Socioeconomic status, economic problems, and delinquency. Youth & Society, 40 (2), 159–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X08318119

Agnew, R., & White, H. R. (1992). An empirical test of general strain theory. Criminology, 30 (4), 475–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1992.tb01113.x