How to write an undergraduate university dissertation

Writing a dissertation is a daunting task, but these tips will help you prepare for all the common challenges students face before deadline day.

Grace McCabe

Writing a dissertation is one of the most challenging aspects of university. However, it is the chance for students to demonstrate what they have learned during their degree and to explore a topic in depth.

In this article, we look at 10 top tips for writing a successful dissertation and break down how to write each section of a dissertation in detail.

10 tips for writing an undergraduate dissertation

1. Select an engaging topic Choose a subject that aligns with your interests and allows you to showcase the skills and knowledge you have acquired through your degree.

2. Research your supervisor Undergraduate students will often be assigned a supervisor based on their research specialisms. Do some research on your supervisor and make sure that they align with your dissertation goals.

3. Understand the dissertation structure Familiarise yourself with the structure (introduction, review of existing research, methodology, findings, results and conclusion). This will vary based on your subject.

4. Write a schedule As soon as you have finalised your topic and looked over the deadline, create a rough plan of how much work you have to do and create mini-deadlines along the way to make sure don’t find yourself having to write your entire dissertation in the final few weeks.

5. Determine requirements Ensure that you know which format your dissertation should be presented in. Check the word count and the referencing style.

6. Organise references from the beginning Maintain an alphabetically arranged reference list or bibliography in the designated style as you do your reading. This will make it a lot easier to finalise your references at the end.

7. Create a detailed plan Once you have done your initial research and have an idea of the shape your dissertation will take, write a detailed essay plan outlining your research questions, SMART objectives and dissertation structure.

8. Keep a dissertation journal Track your progress, record your research and your reading, and document challenges. This will be helpful as you discuss your work with your supervisor and organise your notes.

9. Schedule regular check-ins with your supervisor Make sure you stay in touch with your supervisor throughout the process, scheduling regular meetings and keeping good notes so you can update them on your progress.

10. Employ effective proofreading techniques Ask friends and family to help you proofread your work or use different fonts to help make the text look different. This will help you check for missing sections, grammatical mistakes and typos.

What is a dissertation?

A dissertation is a long piece of academic writing or a research project that you have to write as part of your undergraduate university degree.

It’s usually a long essay in which you explore your chosen topic, present your ideas and show that you understand and can apply what you’ve learned during your studies. Informally, the terms “dissertation” and “thesis” are often used interchangeably.

How do I select a dissertation topic?

First, choose a topic that you find interesting. You will be working on your dissertation for several months, so finding a research topic that you are passionate about and that demonstrates your strength in your subject is best. You want your topic to show all the skills you have developed during your degree. It would be a bonus if you can link your work to your chosen career path, but it’s not necessary.

Second, begin by exploring relevant literature in your field, including academic journals, books and articles. This will help you identify gaps in existing knowledge and areas that may need further exploration. You may not be able to think of a truly original piece of research, but it’s always good to know what has already been written about your chosen topic.

Consider the practical aspects of your chosen topic, ensuring that it is possible within the time frame and available resources. Assess the availability of data, research materials and the overall practicality of conducting the research.

When picking a dissertation topic, you also want to try to choose something that adds new ideas or perspectives to what’s already known in your field. As you narrow your focus, remember that a more targeted approach usually leads to a dissertation that’s easier to manage and has a bigger impact. Be ready to change your plans based on feedback and new information you discover during your research.

How to work with your dissertation supervisor?

Your supervisor is there to provide guidance on your chosen topic, direct your research efforts, and offer assistance and suggestions when you have queries. It’s crucial to establish a comfortable and open line of communication with them throughout the process. Their knowledge can greatly benefit your work. Keep them informed about your progress, seek their advice, and don’t hesitate to ask questions.

1. Keep them updated Regularly tell your supervisor how your work is going and if you’re having any problems. You can do this through emails, meetings or progress reports.

2. Plan meetings Schedule regular meetings with your supervisor. These can be in person or online. These are your time to discuss your progress and ask for help.

3. Share your writing Give your supervisor parts of your writing or an outline. This helps them see what you’re thinking so they can advise you on how to develop it.

5. Ask specific questions When you need help, ask specific questions instead of general ones. This makes it easier for your supervisor to help you.

6. Listen to feedback Be open to what your supervisor says. If they suggest changes, try to make them. It makes your dissertation better and shows you can work together.

7. Talk about problems If something is hard or you’re worried, talk to your supervisor about it. They can give you advice or tell you where to find help.

8. Take charge Be responsible for your work. Let your supervisor know if your plans change, and don’t wait if you need help urgently.

Remember, talking openly with your supervisor helps you both understand each other better, improves your dissertation and ensures that you get the support you need.

How to write a successful research piece at university How to choose a topic for your dissertation Tips for writing a convincing thesis

How do I plan my dissertation?

It’s important to start with a detailed plan that will serve as your road map throughout the entire process of writing your dissertation. As Jumana Labib, a master’s student at the University of Manchester studying digital media, culture and society, suggests: “Pace yourself – definitely don’t leave the entire thing for the last few days or weeks.”

Decide what your research question or questions will be for your chosen topic.

Break that down into smaller SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound) objectives.

Speak to your supervisor about any overlooked areas.

Create a breakdown of chapters using the structure listed below (for example, a methodology chapter).

Define objectives, key points and evidence for each chapter.

Define your research approach (qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods).

Outline your research methods and analysis techniques.

Develop a timeline with regular moments for review and feedback.

Allocate time for revision, editing and breaks.

Consider any ethical considerations related to your research.

Stay organised and add to your references and bibliography throughout the process.

Remain flexible to possible reviews or changes as you go along.

A well thought-out plan not only makes the writing process more manageable but also increases the likelihood of producing a high-quality piece of research.

How to structure a dissertation?

The structure can depend on your field of study, but this is a rough outline for science and social science dissertations:

Introduce your topic.

Complete a source or literature review.

Describe your research methodology (including the methods for gathering and filtering information, analysis techniques, materials, tools or resources used, limitations of your method, and any considerations of reliability).

Summarise your findings.

Discuss the results and what they mean.

Conclude your point and explain how your work contributes to your field.

On the other hand, humanities and arts dissertations often take the form of an extended essay. This involves constructing an argument or exploring a particular theory or analysis through the analysis of primary and secondary sources. Your essay will be structured through chapters arranged around themes or case studies.

All dissertations include a title page, an abstract and a reference list. Some may also need a table of contents at the beginning. Always check with your university department for its dissertation guidelines, and check with your supervisor as you begin to plan your structure to ensure that you have the right layout.

How long is an undergraduate dissertation?

The length of an undergraduate dissertation can vary depending on the specific guidelines provided by your university and your subject department. However, in many cases, undergraduate dissertations are typically about 8,000 to 12,000 words in length.

“Eat away at it; try to write for at least 30 minutes every day, even if it feels relatively unproductive to you in the moment,” Jumana advises.

How do I add references to my dissertation?

References are the section of your dissertation where you acknowledge the sources you have quoted or referred to in your writing. It’s a way of supporting your ideas, evidencing what research you have used and avoiding plagiarism (claiming someone else’s work as your own), and giving credit to the original authors.

Referencing typically includes in-text citations and a reference list or bibliography with full source details. Different referencing styles exist, such as Harvard, APA and MLA, each favoured in specific fields. Your university will tell you the preferred style.

Using tools and guides provided by universities can make the referencing process more manageable, but be sure they are approved by your university before using any.

How do I write a bibliography or list my references for my dissertation?

The requirement of a bibliography depends on the style of referencing you need to use. Styles such as OSCOLA or Chicago may not require a separate bibliography. In these styles, full source information is often incorporated into footnotes throughout the piece, doing away with the need for a separate bibliography section.

Typically, reference lists or bibliographies are organised alphabetically based on the author’s last name. They usually include essential details about each source, providing a quick overview for readers who want more information. Some styles ask that you include references that you didn’t use in your final piece as they were still a part of the overall research.

It is important to maintain this list as soon as you start your research. As you complete your research, you can add more sources to your bibliography to ensure that you have a comprehensive list throughout the dissertation process.

How to proofread an undergraduate dissertation?

Throughout your dissertation writing, attention to detail will be your greatest asset. The best way to avoid making mistakes is to continuously proofread and edit your work.

Proofreading is a great way to catch any missing sections, grammatical errors or typos. There are many tips to help you proofread:

Ask someone to read your piece and highlight any mistakes they find.

Change the font so you notice any mistakes.

Format your piece as you go, headings and sections will make it easier to spot any problems.

Separate editing and proofreading. Editing is your chance to rewrite sections, add more detail or change any points. Proofreading should be where you get into the final touches, really polish what you have and make sure it’s ready to be submitted.

Stick to your citation style and make sure every resource listed in your dissertation is cited in the reference list or bibliography.

How to write a conclusion for my dissertation?

Writing a dissertation conclusion is your chance to leave the reader impressed by your work.

Start by summarising your findings, highlighting your key points and the outcome of your research. Refer back to the original research question or hypotheses to provide context to your conclusion.

You can then delve into whether you achieved the goals you set at the beginning and reflect on whether your research addressed the topic as expected. Make sure you link your findings to existing literature or sources you have included throughout your work and how your own research could contribute to your field.

Be honest about any limitations or issues you faced during your research and consider any questions that went unanswered that you would consider in the future. Make sure that your conclusion is clear and concise, and sum up the overall impact and importance of your work.

Remember, keep the tone confident and authoritative, avoiding the introduction of new information. This should simply be a summary of everything you have already said throughout the dissertation.

You may also like

.css-185owts{overflow:hidden;max-height:54px;text-indent:0px;} How to use digital advisers to improve academic writing

How to deal with exam stress

Seeta Bhardwa

5 revision techniques to help you ace exam season (plus 7 more unusual approaches)

Register free and enjoy extra benefits

How Long is a Dissertation

How Long is a Dissertation? Concrete Answers

An undergraduate dissertation usually falls within the range of 8,000 to 15,000 words, while a master's dissertation typically spans from 12,000 to 50,000 words. In contrast, a PhD thesis is typically of book length, ranging from 70,000 to 100,000 words.

Let’s unravel the mystery of how long should a dissertation be. If you’ve ever wondered about this, look no further. Our comprehensive guide delves into the nitty-gritty of dissertation lengths across diverse academic realms. Whether you're a budding grad student, an academic advisor, or just curious, we've got you covered.

From Master's to PhD programs, we decode the variations in length requirements and shed light on disciplinary disparities. In general, dissertations are 150 to 300 words. But factors influence the length of these daunting scholarly requirements! But fear not as we break it down for you.

We’ll unveil the secrets behind dissertation writing, from how they reflect the depth and breadth of research to offering invaluable tips for planning and writing. So, if you're ready to demystify the daunting dissertation journey, hop on board! Let's navigate the labyrinth of academia together and empower you to conquer your scholarly aspirations.

Institutional guidelines on dissertation length

You can think of institutional guidelines as purveyors of academic excellence. Ever wondered why schools impose specific requirements like "Chapter 1: The Introduction must be at least 35 pages long and no more than 50 pages"?

It's not just about arbitrary rules! However, it's about striking the perfect balance between guidance and practicality. These guidelines serve as guardrails, steering students like you towards scholarly success without overwhelming faculty with endless pages to peruse.

Moreover, credibility is key here! A mere 8-page literature review won't cut it in the realm of academia. But fear not, for most institutions provide dissertation templates, complete with essential headings to streamline the process.

And for those seeking a helping hand, a dissertation writing service like ours stands ready to assist, ensuring your masterpiece meets the lofty standards of academic rigor. So, embrace the guidelines, weave your narrative, and let your dissertation shine with scholarly prowess.

Variations in dissertation length across academic disciplines

Dissertation length varies significantly across academic disciplines due to differences in research methods, data presentation, and writing conventions. Here's a general overview of how dissertation length can differ by discipline:

- Humanities and Social Sciences: Dissertations in these fields tend to be longer because they often involve comprehensive literature reviews, detailed theoretical analyses, and extensive qualitative data. It's not uncommon for dissertations in history, literature, or sociology to exceed 200 pages.

- Sciences and Engineering: Dissertations in the sciences and engineering might be shorter in terms of page count but are dense with technical details, data, charts, and appendices. They often range between 100 to 200 pages. However, the length can vary significantly depending on the complexity of the work and the requirements of the specific program.

- Arts and Design: In creative disciplines, the dissertation might include a practical component (like a portfolio, exhibition, or performance) alongside a written thesis. The written component might be shorter, focusing on the conceptual and contextual analysis of the creative work, usually ranging from 40 to 80 pages.

- Professional Fields (Business, Education, etc.): Dissertations in professional fields such as business or education often focus on case studies, practical applications, and policy analysis. These dissertations can vary widely in length but often fall in the range of 100 to 200 pages.

Dissertations vary in length due to many factors, which shows the diverse nature of academic research. Disciplinary differences are significant, as each field may have distinct expectations regarding the depth and scope of the study.

The type of analysis conducted, whether qualitative, quantitative, or a combination of both, also impacts the length.

For instance, qualitative studies may involve extensive textual analysis, resulting in longer manuscripts, while quantitative studies may require detailed statistical analyses. Additionally, the specific area of research within a discipline can also affect the length, as certain topics may necessitate more:

- extensive literature reviews

- data collection (e.g., fieldwork, surveys, interviews, lab work)

- discussion sections

While the average length typically falls within the range of 150-300 pages, it's essential to recognize the nuanced factors contributing to variations in dissertation length. You must remain informed about the variables shaping your document's overall size and structure to deliver exemplary results.

Factors influencing the length of doctoral dissertations

Various factors determine the length of a dissertation, such as the specific guidelines set by universities, the type of research conducted, the extent of analysis required, and the presence of supplementary materials.

Several factors come into play when determining the ideal length of a dissertation. University guidelines set the tone, with institutions offering word count ranges typically between 8,000 to 15,000 words for undergraduates and masters and 75,000 to 100,000 words for PhD.

Yet, beyond these guidelines, the nature of your research holds sway.

Disciplines vary, with humanities favoring extensive literature reviews and scientific fields emphasizing methodological intricacies. Depth of analysis matters, too; a thorough exploration demands more space.

Balancing these elements ensures a well-rounded dissertation. So, as you embark on your scholarly journey, consider these factors carefully. By understanding them, you'll craft a dissertation that not only meets academic standards but also showcases your analytical prowess and depth of intelligence.

Length, components, and scholarly dedication

Many aspiring scholars think, "How long is a doctoral dissertation?" However, the answer isn't straightforward. Yes, length varies, but let's not forget to factor in a crucial element: time. And we know because many students have instructed us to “ write my dissertation !”

Remember, a dissertation isn't penned in one sitting. Rather, it often evolves from smaller academic chapters. This gradual process allows students to explore diverse topics before committing to a book-length project they're passionate about.

Beyond the central argument lie various components that contribute to the overall length. Take the literature review, for example—an essential segment that contextualizes the research by analyzing existing scholarship. Then there's the myriad of ancillary elements like the title page, acknowledgments, abstract, and appendix, each adding to the dissertation's page count.

It’s the accumulation of these parts that determines the length. So, while the answer may not be a precise number, it's crucial to acknowledge many elements that make up a doctoral dissertation. And for those embarking on this scholarly journey, we can help you conquer this challenge.

How Long is a Dissertation Chapter? Uncover the Mystery

When it comes to dissertation length, most grad students fret over how long each chapter should be. While there's no one-size-fits-all answer, there is a golden rule–chapters should be long enough to address the research question comprehensively.

Think quality over quantity! Ask any dissertation adviser, and they’ll say aiming to fill a predetermined number of pages shouldn’t be the goal. Rather, you must thoroughly explore your topic, conduct extensive research, and present your findings effectively.

Your writing style and the unique nature of your research also play pivotal roles. So, whether your chapter spans 50 pages or 150, ensure it's packed with substantive content that advances your study. Ultimately, it's not about hitting a page count but about delivering a high-quality scholarly contribution.

Writing an Excellent PhD Dissertation: Strategies and Tips

After you’re done pondering on how many pages should a dissertation be, you can move on with production. Wondering how to write a dissertation , here are some tips:

- Start with a significant research topic that inspires you and formulate a clear research question.

- Thoroughly review existing literature to contextualize your study.

- Develop a robust methodology and collect comprehensive data.

- Analyze findings meticulously and synthesize them effectively.

- Ensure logical flow throughout your writing, striving for clarity and coherence.

- Engage with other scholars, both peers and mentors, to refine your work.

- Maintain consistency in formatting and adhere to academic standards.

Remember, with meticulous planning and dedication, you'll produce a dissertation that makes you and your mentors proud.

How long is a PhD dissertation?: The Conundrum

Do you belong to the list of students who feel bewildered about PhD dissertation length? Many wonder because of the length’s variability across disciplines and institutions. The general ballpark figure for a completed doctoral dissertation is typically between 150 to 300 pages. Yet, this can vary widely depending on factors such as:

- field of study

- research methodology used

- individual institutional requirements

- guidelines of mentors

Although there's no one-size-fits-all answer, understanding these variables can help you navigate the ambiguity surrounding dissertation length. And with proper planning, you can create an impressive output.

Frequently asked questions

How to properly plan and prepare for a long dissertation .

Thinking about how long is a dissertation for PhD stops students on their track. It can indeed be overwhelming when you think of the amount of work involved. But with proper planning, you can crush your goals. Here are some helpful tips:

- Break down your work into manageable steps.

- Define your research question clearly and set realistic milestones.

- Create an outline to help you write. `

- Have a schedule for research, writing, and revisions.

- Stay organized with notes, citations, and references.

- Seek feedback from advisors and peers throughout the process.

Remember, embrace the challenges you face as opportunities for growth!

Are supporting materials counted in the dissertation word count?

Worried about how long is a dissertation paper and if yours will make the cut? Remember, appendices, tables, and figures, while essential, aren't factored into the word count. So, you can incorporate these supplementary elements without concerns about exceeding word limits.

If you’re pressed for time, you can buy dissertation online . Just ensure to give appropriate instructions so the final output adheres to your institution's formatting guidelines. With these supporting materials appropriately included, your dissertation will be comprehensive.

Are there different types of dissertations?

When asking how long are dissertations, one of the first things to consider is the field of study. Various types of dissertations exist, often shaped by research methodology. It can be quantitative to qualitative studies or triangulation (a blend of both).

Instead of worrying about the length, determine your research approach—whether it's primary or secondary, qualitative or quantitative. This decision significantly impacts the depth and breadth of your investigation, ultimately influencing the expected length of your dissertation. By aligning your research methods with your academic goals, you'll gain clarity on the scope of your writing project.

Another aspect of the length of the entire document is the type of thesis - be it an undergraduate thesis, masters thesis, or thesis for an advanced degree, most dissertations for academic programs are lengthy. The more advanced the degree, the longer the thesis usually is.

Are dissertations just for PhDs?

How many pages in a dissertation is something most students worry about. But is a dissertation just for doctoral candidates? In some countries, dissertations are exclusive to PhDs. However, for other countries, the term “dissertation” is interchangeable with "thesis." Why so?

Because both are research projects completed for undergraduate or postgraduate degrees. Keep in mind that whether you’re pursuing a bachelor's, an MA, or a doctorate, dissertation writing demonstrates your research skills and academic proficiency.

Your doctoral degree, just like your graduate degree from a graduate school, shows you can successfully navigate the research process, theoretical framework, and dissertation defense. Sure, the scope of research was less focused while you were a graduate student with a master's thesis. Nonetheless, it shows consistent work and dedication.

How many chapters in a dissertation?

Still mulling over how long does a dissertation have to be and how many chapters you must write? Dissertations usually consist of five to seven chapters. These typically cover the following:

- introduction

- literature review

- methodology

However, the structure can vary depending on your field of study and specific institutional guidelines. Each chapter plays a vital role, leading readers through your research journey, from laying the groundwork to presenting findings and drawing conclusions.

How do I find a reputable dissertation writer to help me?

Worried about how long are PhD dissertations? No need to worry. You can opt for professional help, and there’s no shame in that! Research for online platforms that specialize in academic writing services like our Studyfy team.

You can take a peek at our positive reviews and testimonials, showing our track record of delivering high-quality work. Choose a writer who possesses expertise in your field of study and can meet your specific requirements. Prioritize the following:

- clear communication

- appropriate instructions (from word count to deadlines)

- transparency regarding pricing

- upfront about revision policies.

By vetting potential writers and choosing a reputable service, you can secure the assistance of a reliable professional to guide you through the dissertation writing process.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

How to Write a Dissertation | A Guide to Structure & Content

A dissertation or thesis is a long piece of academic writing based on original research, submitted as part of an undergraduate or postgraduate degree.

The structure of a dissertation depends on your field, but it is usually divided into at least four or five chapters (including an introduction and conclusion chapter).

The most common dissertation structure in the sciences and social sciences includes:

- An introduction to your topic

- A literature review that surveys relevant sources

- An explanation of your methodology

- An overview of the results of your research

- A discussion of the results and their implications

- A conclusion that shows what your research has contributed

Dissertations in the humanities are often structured more like a long essay , building an argument by analysing primary and secondary sources . Instead of the standard structure outlined here, you might organise your chapters around different themes or case studies.

Other important elements of the dissertation include the title page , abstract , and reference list . If in doubt about how your dissertation should be structured, always check your department’s guidelines and consult with your supervisor.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Acknowledgements, table of contents, list of figures and tables, list of abbreviations, introduction, literature review / theoretical framework, methodology, reference list.

The very first page of your document contains your dissertation’s title, your name, department, institution, degree program, and submission date. Sometimes it also includes your student number, your supervisor’s name, and the university’s logo. Many programs have strict requirements for formatting the dissertation title page .

The title page is often used as cover when printing and binding your dissertation .

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

The acknowledgements section is usually optional, and gives space for you to thank everyone who helped you in writing your dissertation. This might include your supervisors, participants in your research, and friends or family who supported you.

The abstract is a short summary of your dissertation, usually about 150-300 words long. You should write it at the very end, when you’ve completed the rest of the dissertation. In the abstract, make sure to:

- State the main topic and aims of your research

- Describe the methods you used

- Summarise the main results

- State your conclusions

Although the abstract is very short, it’s the first part (and sometimes the only part) of your dissertation that people will read, so it’s important that you get it right. If you’re struggling to write a strong abstract, read our guide on how to write an abstract .

In the table of contents, list all of your chapters and subheadings and their page numbers. The dissertation contents page gives the reader an overview of your structure and helps easily navigate the document.

All parts of your dissertation should be included in the table of contents, including the appendices. You can generate a table of contents automatically in Word.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

If you have used a lot of tables and figures in your dissertation, you should itemise them in a numbered list . You can automatically generate this list using the Insert Caption feature in Word.

If you have used a lot of abbreviations in your dissertation, you can include them in an alphabetised list of abbreviations so that the reader can easily look up their meanings.

If you have used a lot of highly specialised terms that will not be familiar to your reader, it might be a good idea to include a glossary . List the terms alphabetically and explain each term with a brief description or definition.

In the introduction, you set up your dissertation’s topic, purpose, and relevance, and tell the reader what to expect in the rest of the dissertation. The introduction should:

- Establish your research topic , giving necessary background information to contextualise your work

- Narrow down the focus and define the scope of the research

- Discuss the state of existing research on the topic, showing your work’s relevance to a broader problem or debate

- Clearly state your objectives and research questions , and indicate how you will answer them

- Give an overview of your dissertation’s structure

Everything in the introduction should be clear, engaging, and relevant to your research. By the end, the reader should understand the what , why and how of your research. Not sure how? Read our guide on how to write a dissertation introduction .

Before you start on your research, you should have conducted a literature review to gain a thorough understanding of the academic work that already exists on your topic. This means:

- Collecting sources (e.g. books and journal articles) and selecting the most relevant ones

- Critically evaluating and analysing each source

- Drawing connections between them (e.g. themes, patterns, conflicts, gaps) to make an overall point

In the dissertation literature review chapter or section, you shouldn’t just summarise existing studies, but develop a coherent structure and argument that leads to a clear basis or justification for your own research. For example, it might aim to show how your research:

- Addresses a gap in the literature

- Takes a new theoretical or methodological approach to the topic

- Proposes a solution to an unresolved problem

- Advances a theoretical debate

- Builds on and strengthens existing knowledge with new data

The literature review often becomes the basis for a theoretical framework , in which you define and analyse the key theories, concepts and models that frame your research. In this section you can answer descriptive research questions about the relationship between concepts or variables.

The methodology chapter or section describes how you conducted your research, allowing your reader to assess its validity. You should generally include:

- The overall approach and type of research (e.g. qualitative, quantitative, experimental, ethnographic)

- Your methods of collecting data (e.g. interviews, surveys, archives)

- Details of where, when, and with whom the research took place

- Your methods of analysing data (e.g. statistical analysis, discourse analysis)

- Tools and materials you used (e.g. computer programs, lab equipment)

- A discussion of any obstacles you faced in conducting the research and how you overcame them

- An evaluation or justification of your methods

Your aim in the methodology is to accurately report what you did, as well as convincing the reader that this was the best approach to answering your research questions or objectives.

Next, you report the results of your research . You can structure this section around sub-questions, hypotheses, or topics. Only report results that are relevant to your objectives and research questions. In some disciplines, the results section is strictly separated from the discussion, while in others the two are combined.

For example, for qualitative methods like in-depth interviews, the presentation of the data will often be woven together with discussion and analysis, while in quantitative and experimental research, the results should be presented separately before you discuss their meaning. If you’re unsure, consult with your supervisor and look at sample dissertations to find out the best structure for your research.

In the results section it can often be helpful to include tables, graphs and charts. Think carefully about how best to present your data, and don’t include tables or figures that just repeat what you have written – they should provide extra information or usefully visualise the results in a way that adds value to your text.

Full versions of your data (such as interview transcripts) can be included as an appendix .

The discussion is where you explore the meaning and implications of your results in relation to your research questions. Here you should interpret the results in detail, discussing whether they met your expectations and how well they fit with the framework that you built in earlier chapters. If any of the results were unexpected, offer explanations for why this might be. It’s a good idea to consider alternative interpretations of your data and discuss any limitations that might have influenced the results.

The discussion should reference other scholarly work to show how your results fit with existing knowledge. You can also make recommendations for future research or practical action.

The dissertation conclusion should concisely answer the main research question, leaving the reader with a clear understanding of your central argument. Wrap up your dissertation with a final reflection on what you did and how you did it. The conclusion often also includes recommendations for research or practice.

In this section, it’s important to show how your findings contribute to knowledge in the field and why your research matters. What have you added to what was already known?

You must include full details of all sources that you have cited in a reference list (sometimes also called a works cited list or bibliography). It’s important to follow a consistent reference style . Each style has strict and specific requirements for how to format your sources in the reference list.

The most common styles used in UK universities are Harvard referencing and Vancouver referencing . Your department will often specify which referencing style you should use – for example, psychology students tend to use APA style , humanities students often use MHRA , and law students always use OSCOLA . M ake sure to check the requirements, and ask your supervisor if you’re unsure.

To save time creating the reference list and make sure your citations are correctly and consistently formatted, you can use our free APA Citation Generator .

Your dissertation itself should contain only essential information that directly contributes to answering your research question. Documents you have used that do not fit into the main body of your dissertation (such as interview transcripts, survey questions or tables with full figures) can be added as appendices .

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- What Is a Dissertation? | 5 Essential Questions to Get Started

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

- How to Write a Dissertation Proposal | A Step-by-Step Guide

More interesting articles

- Checklist: Writing a dissertation

- Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates

- Dissertation binding and printing

- Dissertation Table of Contents in Word | Instructions & Examples

- Dissertation title page

- Example Theoretical Framework of a Dissertation or Thesis

- Figure & Table Lists | Word Instructions, Template & Examples

- How to Choose a Dissertation Topic | 8 Steps to Follow

- How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Results Section | Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Conclusion

- How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Introduction

- How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

- How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

- List of Abbreviations | Example, Template & Best Practices

- Operationalisation | A Guide with Examples, Pros & Cons

- Prize-Winning Thesis and Dissertation Examples

- Relevance of Your Dissertation Topic | Criteria & Tips

- Research Paper Appendix | Example & Templates

- Thesis & Dissertation Acknowledgements | Tips & Examples

- Thesis & Dissertation Database Examples

- What is a Dissertation Preface? | Definition & Examples

- What is a Glossary? | Definition, Templates, & Examples

- What Is a Research Methodology? | Steps & Tips

- What is a Theoretical Framework? | A Step-by-Step Guide

- What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples

Dissertation Structure & Layout 101: How to structure your dissertation, thesis or research project.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Reviewed By: David Phair (PhD) | July 2019

So, you’ve got a decent understanding of what a dissertation is , you’ve chosen your topic and hopefully you’ve received approval for your research proposal . Awesome! Now its time to start the actual dissertation or thesis writing journey.

To craft a high-quality document, the very first thing you need to understand is dissertation structure . In this post, we’ll walk you through the generic dissertation structure and layout, step by step. We’ll start with the big picture, and then zoom into each chapter to briefly discuss the core contents. If you’re just starting out on your research journey, you should start with this post, which covers the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis .

*The Caveat *

In this post, we’ll be discussing a traditional dissertation/thesis structure and layout, which is generally used for social science research across universities, whether in the US, UK, Europe or Australia. However, some universities may have small variations on this structure (extra chapters, merged chapters, slightly different ordering, etc).

So, always check with your university if they have a prescribed structure or layout that they expect you to work with. If not, it’s safe to assume the structure we’ll discuss here is suitable. And even if they do have a prescribed structure, you’ll still get value from this post as we’ll explain the core contents of each section.

Overview: S tructuring a dissertation or thesis

- Acknowledgements page

- Abstract (or executive summary)

- Table of contents , list of figures and tables

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Literature review

- Chapter 3: Methodology

- Chapter 4: Results

- Chapter 5: Discussion

- Chapter 6: Conclusion

- Reference list

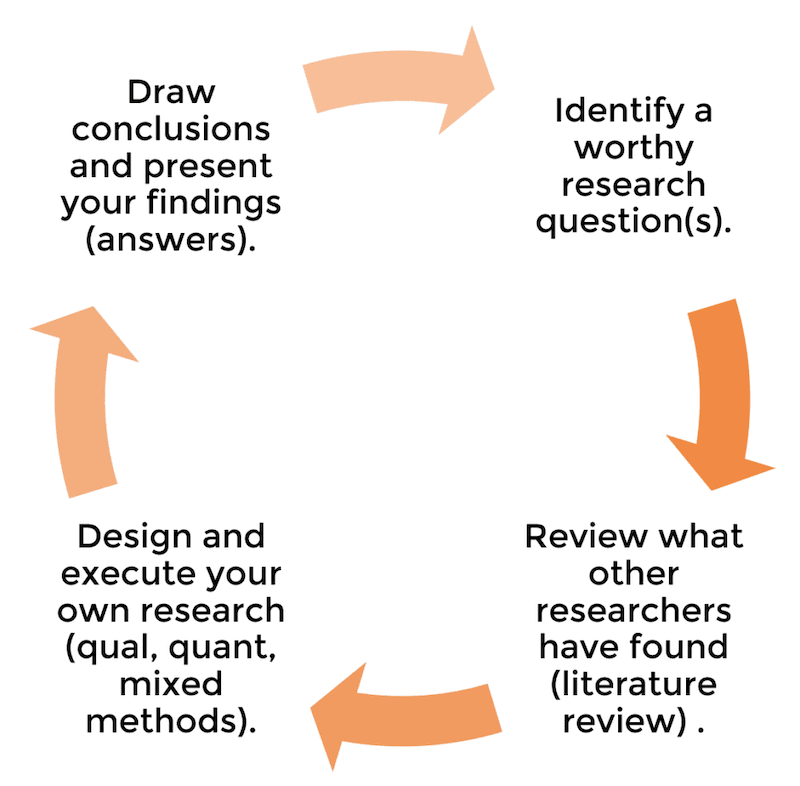

As I mentioned, some universities will have slight variations on this structure. For example, they want an additional “personal reflection chapter”, or they might prefer the results and discussion chapter to be merged into one. Regardless, the overarching flow will always be the same, as this flow reflects the research process , which we discussed here – i.e.:

- The introduction chapter presents the core research question and aims .

- The literature review chapter assesses what the current research says about this question.

- The methodology, results and discussion chapters go about undertaking new research about this question.

- The conclusion chapter (attempts to) answer the core research question .

In other words, the dissertation structure and layout reflect the research process of asking a well-defined question(s), investigating, and then answering the question – see below.

To restate that – the structure and layout of a dissertation reflect the flow of the overall research process . This is essential to understand, as each chapter will make a lot more sense if you “get” this concept. If you’re not familiar with the research process, read this post before going further.

Right. Now that we’ve covered the big picture, let’s dive a little deeper into the details of each section and chapter. Oh and by the way, you can also grab our free dissertation/thesis template here to help speed things up.

The title page of your dissertation is the very first impression the marker will get of your work, so it pays to invest some time thinking about your title. But what makes for a good title? A strong title needs to be 3 things:

- Succinct (not overly lengthy or verbose)

- Specific (not vague or ambiguous)

- Representative of the research you’re undertaking (clearly linked to your research questions)

Typically, a good title includes mention of the following:

- The broader area of the research (i.e. the overarching topic)

- The specific focus of your research (i.e. your specific context)

- Indication of research design (e.g. quantitative , qualitative , or mixed methods ).

For example:

A quantitative investigation [research design] into the antecedents of organisational trust [broader area] in the UK retail forex trading market [specific context/area of focus].

Again, some universities may have specific requirements regarding the format and structure of the title, so it’s worth double-checking expectations with your institution (if there’s no mention in the brief or study material).

Acknowledgements

This page provides you with an opportunity to say thank you to those who helped you along your research journey. Generally, it’s optional (and won’t count towards your marks), but it is academic best practice to include this.

So, who do you say thanks to? Well, there’s no prescribed requirements, but it’s common to mention the following people:

- Your dissertation supervisor or committee.

- Any professors, lecturers or academics that helped you understand the topic or methodologies.

- Any tutors, mentors or advisors.

- Your family and friends, especially spouse (for adult learners studying part-time).

There’s no need for lengthy rambling. Just state who you’re thankful to and for what (e.g. thank you to my supervisor, John Doe, for his endless patience and attentiveness) – be sincere. In terms of length, you should keep this to a page or less.

Abstract or executive summary

The dissertation abstract (or executive summary for some degrees) serves to provide the first-time reader (and marker or moderator) with a big-picture view of your research project. It should give them an understanding of the key insights and findings from the research, without them needing to read the rest of the report – in other words, it should be able to stand alone .

For it to stand alone, your abstract should cover the following key points (at a minimum):

- Your research questions and aims – what key question(s) did your research aim to answer?

- Your methodology – how did you go about investigating the topic and finding answers to your research question(s)?

- Your findings – following your own research, what did do you discover?

- Your conclusions – based on your findings, what conclusions did you draw? What answers did you find to your research question(s)?

So, in much the same way the dissertation structure mimics the research process, your abstract or executive summary should reflect the research process, from the initial stage of asking the original question to the final stage of answering that question.

In practical terms, it’s a good idea to write this section up last , once all your core chapters are complete. Otherwise, you’ll end up writing and rewriting this section multiple times (just wasting time). For a step by step guide on how to write a strong executive summary, check out this post .

Need a helping hand?

Table of contents

This section is straightforward. You’ll typically present your table of contents (TOC) first, followed by the two lists – figures and tables. I recommend that you use Microsoft Word’s automatic table of contents generator to generate your TOC. If you’re not familiar with this functionality, the video below explains it simply:

If you find that your table of contents is overly lengthy, consider removing one level of depth. Oftentimes, this can be done without detracting from the usefulness of the TOC.

Right, now that the “admin” sections are out of the way, its time to move on to your core chapters. These chapters are the heart of your dissertation and are where you’ll earn the marks. The first chapter is the introduction chapter – as you would expect, this is the time to introduce your research…

It’s important to understand that even though you’ve provided an overview of your research in your abstract, your introduction needs to be written as if the reader has not read that (remember, the abstract is essentially a standalone document). So, your introduction chapter needs to start from the very beginning, and should address the following questions:

- What will you be investigating (in plain-language, big picture-level)?

- Why is that worth investigating? How is it important to academia or business? How is it sufficiently original?

- What are your research aims and research question(s)? Note that the research questions can sometimes be presented at the end of the literature review (next chapter).

- What is the scope of your study? In other words, what will and won’t you cover ?

- How will you approach your research? In other words, what methodology will you adopt?

- How will you structure your dissertation? What are the core chapters and what will you do in each of them?

These are just the bare basic requirements for your intro chapter. Some universities will want additional bells and whistles in the intro chapter, so be sure to carefully read your brief or consult your research supervisor.

If done right, your introduction chapter will set a clear direction for the rest of your dissertation. Specifically, it will make it clear to the reader (and marker) exactly what you’ll be investigating, why that’s important, and how you’ll be going about the investigation. Conversely, if your introduction chapter leaves a first-time reader wondering what exactly you’ll be researching, you’ve still got some work to do.

Now that you’ve set a clear direction with your introduction chapter, the next step is the literature review . In this section, you will analyse the existing research (typically academic journal articles and high-quality industry publications), with a view to understanding the following questions:

- What does the literature currently say about the topic you’re investigating?

- Is the literature lacking or well established? Is it divided or in disagreement?

- How does your research fit into the bigger picture?

- How does your research contribute something original?

- How does the methodology of previous studies help you develop your own?

Depending on the nature of your study, you may also present a conceptual framework towards the end of your literature review, which you will then test in your actual research.

Again, some universities will want you to focus on some of these areas more than others, some will have additional or fewer requirements, and so on. Therefore, as always, its important to review your brief and/or discuss with your supervisor, so that you know exactly what’s expected of your literature review chapter.

Now that you’ve investigated the current state of knowledge in your literature review chapter and are familiar with the existing key theories, models and frameworks, its time to design your own research. Enter the methodology chapter – the most “science-ey” of the chapters…

In this chapter, you need to address two critical questions:

- Exactly HOW will you carry out your research (i.e. what is your intended research design)?

- Exactly WHY have you chosen to do things this way (i.e. how do you justify your design)?

Remember, the dissertation part of your degree is first and foremost about developing and demonstrating research skills . Therefore, the markers want to see that you know which methods to use, can clearly articulate why you’ve chosen then, and know how to deploy them effectively.

Importantly, this chapter requires detail – don’t hold back on the specifics. State exactly what you’ll be doing, with who, when, for how long, etc. Moreover, for every design choice you make, make sure you justify it.

In practice, you will likely end up coming back to this chapter once you’ve undertaken all your data collection and analysis, and revise it based on changes you made during the analysis phase. This is perfectly fine. Its natural for you to add an additional analysis technique, scrap an old one, etc based on where your data lead you. Of course, I’m talking about small changes here – not a fundamental switch from qualitative to quantitative, which will likely send your supervisor in a spin!

You’ve now collected your data and undertaken your analysis, whether qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods. In this chapter, you’ll present the raw results of your analysis . For example, in the case of a quant study, you’ll present the demographic data, descriptive statistics, inferential statistics , etc.

Typically, Chapter 4 is simply a presentation and description of the data, not a discussion of the meaning of the data. In other words, it’s descriptive, rather than analytical – the meaning is discussed in Chapter 5. However, some universities will want you to combine chapters 4 and 5, so that you both present and interpret the meaning of the data at the same time. Check with your institution what their preference is.

Now that you’ve presented the data analysis results, its time to interpret and analyse them. In other words, its time to discuss what they mean, especially in relation to your research question(s).

What you discuss here will depend largely on your chosen methodology. For example, if you’ve gone the quantitative route, you might discuss the relationships between variables . If you’ve gone the qualitative route, you might discuss key themes and the meanings thereof. It all depends on what your research design choices were.

Most importantly, you need to discuss your results in relation to your research questions and aims, as well as the existing literature. What do the results tell you about your research questions? Are they aligned with the existing research or at odds? If so, why might this be? Dig deep into your findings and explain what the findings suggest, in plain English.

The final chapter – you’ve made it! Now that you’ve discussed your interpretation of the results, its time to bring it back to the beginning with the conclusion chapter . In other words, its time to (attempt to) answer your original research question s (from way back in chapter 1). Clearly state what your conclusions are in terms of your research questions. This might feel a bit repetitive, as you would have touched on this in the previous chapter, but its important to bring the discussion full circle and explicitly state your answer(s) to the research question(s).

Next, you’ll typically discuss the implications of your findings . In other words, you’ve answered your research questions – but what does this mean for the real world (or even for academia)? What should now be done differently, given the new insight you’ve generated?

Lastly, you should discuss the limitations of your research, as well as what this means for future research in the area. No study is perfect, especially not a Masters-level. Discuss the shortcomings of your research. Perhaps your methodology was limited, perhaps your sample size was small or not representative, etc, etc. Don’t be afraid to critique your work – the markers want to see that you can identify the limitations of your work. This is a strength, not a weakness. Be brutal!

This marks the end of your core chapters – woohoo! From here on out, it’s pretty smooth sailing.

The reference list is straightforward. It should contain a list of all resources cited in your dissertation, in the required format, e.g. APA , Harvard, etc.

It’s essential that you use reference management software for your dissertation. Do NOT try handle your referencing manually – its far too error prone. On a reference list of multiple pages, you’re going to make mistake. To this end, I suggest considering either Mendeley or Zotero. Both are free and provide a very straightforward interface to ensure that your referencing is 100% on point. I’ve included a simple how-to video for the Mendeley software (my personal favourite) below:

Some universities may ask you to include a bibliography, as opposed to a reference list. These two things are not the same . A bibliography is similar to a reference list, except that it also includes resources which informed your thinking but were not directly cited in your dissertation. So, double-check your brief and make sure you use the right one.

The very last piece of the puzzle is the appendix or set of appendices. This is where you’ll include any supporting data and evidence. Importantly, supporting is the keyword here.

Your appendices should provide additional “nice to know”, depth-adding information, which is not critical to the core analysis. Appendices should not be used as a way to cut down word count (see this post which covers how to reduce word count ). In other words, don’t place content that is critical to the core analysis here, just to save word count. You will not earn marks on any content in the appendices, so don’t try to play the system!

Time to recap…

And there you have it – the traditional dissertation structure and layout, from A-Z. To recap, the core structure for a dissertation or thesis is (typically) as follows:

- Acknowledgments page

Most importantly, the core chapters should reflect the research process (asking, investigating and answering your research question). Moreover, the research question(s) should form the golden thread throughout your dissertation structure. Everything should revolve around the research questions, and as you’ve seen, they should form both the start point (i.e. introduction chapter) and the endpoint (i.e. conclusion chapter).

I hope this post has provided you with clarity about the traditional dissertation/thesis structure and layout. If you have any questions or comments, please leave a comment below, or feel free to get in touch with us. Also, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach Blog .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

36 Comments

many thanks i found it very useful

Glad to hear that, Arun. Good luck writing your dissertation.

Such clear practical logical advice. I very much needed to read this to keep me focused in stead of fretting.. Perfect now ready to start my research!

what about scientific fields like computer or engineering thesis what is the difference in the structure? thank you very much

Thanks so much this helped me a lot!

Very helpful and accessible. What I like most is how practical the advice is along with helpful tools/ links.

Thanks Ade!

Thank you so much sir.. It was really helpful..

You’re welcome!

Hi! How many words maximum should contain the abstract?

Thank you so much 😊 Find this at the right moment

You’re most welcome. Good luck with your dissertation.

best ever benefit i got on right time thank you

Many times Clarity and vision of destination of dissertation is what makes the difference between good ,average and great researchers the same way a great automobile driver is fast with clarity of address and Clear weather conditions .

I guess Great researcher = great ideas + knowledge + great and fast data collection and modeling + great writing + high clarity on all these

You have given immense clarity from start to end.

Morning. Where will I write the definitions of what I’m referring to in my report?

Thank you so much Derek, I was almost lost! Thanks a tonnnn! Have a great day!

Thanks ! so concise and valuable

This was very helpful. Clear and concise. I know exactly what to do now.

Thank you for allowing me to go through briefly. I hope to find time to continue.

Really useful to me. Thanks a thousand times

Very interesting! It will definitely set me and many more for success. highly recommended.

Thank you soo much sir, for the opportunity to express my skills

Usefull, thanks a lot. Really clear

Very nice and easy to understand. Thank you .

That was incredibly useful. Thanks Grad Coach Crew!

My stress level just dropped at least 15 points after watching this. Just starting my thesis for my grad program and I feel a lot more capable now! Thanks for such a clear and helpful video, Emma and the GradCoach team!

Do we need to mention the number of words the dissertation contains in the main document?

It depends on your university’s requirements, so it would be best to check with them 🙂

Such a helpful post to help me get started with structuring my masters dissertation, thank you!

Great video; I appreciate that helpful information

It is so necessary or avital course

This blog is very informative for my research. Thank you

Doctoral students are required to fill out the National Research Council’s Survey of Earned Doctorates

wow this is an amazing gain in my life

This is so good

How can i arrange my specific objectives in my dissertation?

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is A Literature Review (In A Dissertation Or Thesis) - Grad Coach - […] is to write the actual literature review chapter (this is usually the second chapter in a typical dissertation or…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Want to Get your Dissertation Accepted?

Discover how we've helped doctoral students complete their dissertations and advance their academic careers!

Join 200+ Graduated Students

Get Your Dissertation Accepted On Your Next Submission

Get customized coaching for:.

- Crafting your proposal,

- Collecting and analyzing your data, or

- Preparing your defense.

Trapped in dissertation revisions?

How long does it take to write a dissertation, published by steve tippins on july 11, 2019 july 11, 2019.

Last Updated on: 2nd February 2024, 05:00 am

How long does it take to write a dissertation? The most accurate (and least helpful) answer is, it depends. Since that’s probably not the answer you’re looking for, I’ll use the rest of the article to address the realities of how long it takes to write a dissertation.

How Long Does It Take to Write a Dissertation?

Based on my experience, writing your dissertation should take somewhere between 13-20 months. These are average numbers based upon the scores of doctoral students that I have worked with over the years, and they generally hold true.

I have seen people take less time and more time, but I believe that with concerted effort, the 13-20 month timeframe is reasonable.

“Based on my experience, writing your dissertation should take somewhere between 13-20 months.”

University Requirements

Once you hit the dissertation stage, some schools require a minimum number of hours in the dissertation area before you can graduate. Many schools require the equivalent of one year of dissertation credits to graduate.

So, even if you can finish your dissertation in three months, you will still have to pay for nine more months of dissertation credits before you can graduate. However, unless research and writing is your superpower, I wouldn’t worry about having to pay extra tuition.

But this requirement does offer some insight into how long it takes to write a dissertation. Based on this requirement, it’s reasonable to expect that writing your dissertation will take a year of more. This is consistent with my experience.

However, this timeframe is based on several assumptions. First, I am assuming that you are continually working towards finishing your dissertation. This means that no family emergencies, funding conundrums, or work issues get in the way of completing. Second, there are no major changes in your dissertation committee. Third, you will have access to the data that you need.

Assuming these assumptions hold true, this article should give you a general idea of how long it might take to write your dissertation.

How Long Does it Take to Write A Dissertation? Stage-By-Stage

Let’s break down each stage of the dissertation writing process and how long it takes.

Prospectus

This is the hardest one to judge, as this is where you lay the groundwork for the rest of your dissertation and get buy-in from committee members. Normally this takes from 3-6 months. Not all of this is writing time, though–much of it is spent refining your topic and your approach.

Why does this stage take so long? For many people, starting to express themselves using an academic voice can take time. This can hold up the review process as your committee members ask for writing-related revisions before they even get to evaluating the content. Don’t worry, once you learn the academic language things will start to flow more easily.

One common mistake students make is lack of specificity, both in their writing in general and in their topic focus.

Proposal (Chapters 1-3)

Chapter 1 is often an expansion of your Prospectus. However, you’ll be expected to develop your ideas more and have even more specificity on things like your research question and methodology, so don’t underestimate how long this chapter will take.

Chapter 2 can take some time as you will be digging deep into the literature but I think this can be done in 3-4 months. One caution, some people, and committees, like to start with Chapter 2 so that you are immersed in the literature before completing Chapters 1 and 3. Regardless of where you start, 3-4 months is a good estimate.

Chapter 3 requires an in-depth explanation of your methodology. I suggest working closely with your Chair on this one to avoid multiple submissions and revisions. Get clear on your methodology and make sure you and your chair are on the same page before you write, and continue to check in with your chair, if possible, throughout the process.

IRB Approval

While this step can be full of details and require several iterations it seems that allowing 2 months is sufficient. Most schools have an IRB form that must be submitted. To save time you can usually start filling out the form while your committee is reviewing your Proposal.

Collecting Data

This step varies a great deal. If you are using readily available secondary data this can take a week but if you are interviewing hard to get individuals or have trouble finding a sufficient number of people for your sample this can take 4 months or more. I think 1-4 months should be appropriate

Chapters 4 and 5

These two chapters are the easiest to write as in Chapter 4 you are reporting your results and in Chapter 5 you explain what the results mean. I believe that these two chapters can be written in 2 months.

Defense and Completion

You will need to defend your dissertation and then go through all of the university requirements to finalize the completion of your dissertation. I would allow 2 months for this process.

Variables That Affect How Long It Takes to Write A Dissertation

When students say something like, “I’m going to finish my dissertation in three months,” they likely aren’t considering all of the variables besides the actual writing. Even if you’re a fast writer, you’ll have to wait on your committee’s comments,

Timing Issues

Many schools have response times for committee members. This is important when looking at how long it takes to finish a dissertation. For example, it you have two committee members and they each get up to 2 weeks for a review, it can take up to a month to get a document reviewed, each time you submit. So, plan for these periods of time when thinking about how long that it will take you.

Addressing Comments

How long it takes to write your dissertation also depends on your ability to address your committee’s comments thoroughly. It’s not uncommon for a committee member to send a draft back several times, even if their comments were addressed adequately, because they notice new issues each time they read it. Save yourself considerable time by making sure you address their comments fully, thus avoiding unnecessary time waiting to hear the same feedback.

This is the biggest variable in the dissertation model. How dedicated are you to the process? How much actual time do you have? How many outside interests/requirements do you have? Are you easily distracted? How clean does your workspace need to be? (This may seem like a strange thing to discuss, but many people need to work in a clean space and can get very interested in cleaning if they have to write). Are you in a full-time program or in a part time program? Are you holding down a job? Do you have children?

All of these things will affect how much time you have to put into writing–or rather, how disciplined you need to be about making time to write.

One of the things that can influence how long it takes to write your dissertation is your committee. Choose your committee wisely. If you work under the assumption that the only good dissertation is a done dissertation, then you want a committee that will be helpful and not trying to prove themselves on your back. When you find a Chair that you can work with ask her/him which of their colleagues they work well with (it’s also worth finding out who they don’t work well with).

Find out how they like to receive material to review. Some members like to see pieces of chapters and some like to see completed documents. Once you know their preferences, you can efficiently submit what they want when they want it.

How Long Does it Take to Write a Dissertation? Summary

Barring unforeseen events, the normal time range for finishing a dissertation seems to be 13-19 months, which can be rounded to one to one and a half years. If you are proactive and efficient, you can usually be at the shorter end of the time range.

That means using downtime to do things like changing the tense of your approved Proposal from future tense to past tense and completing things like you Abstract and Acknowledgement sections before final approval.

I hope that you can be efficient in this process and finish as quickly as possible. Remember, “the only good dissertation is a done dissertation.”

On that note, I offer coaching services to help students through the dissertation writing process, as well as editing services for those who need help with their writing.

Steve Tippins

Steve Tippins, PhD, has thrived in academia for over thirty years. He continues to love teaching in addition to coaching recent PhD graduates as well as students writing their dissertations. Learn more about his dissertation coaching and career coaching services. Book a Free Consultation with Steve Tippins

Related Posts

Dissertation

Dissertation memes.

Sometimes you can’t dissertate anymore and you just need to meme. Don’t worry, I’ve got you. Here are some of my favorite dissertation memes that I’ve seen lately. My Favorite Dissertation Memes For when you Read more…

Surviving Post Dissertation Stress Disorder

The process of earning a doctorate can be long and stressful – and for some people, it can even be traumatic. This may be hard for those who haven’t been through a doctoral program to Read more…

PhD by Publication

PhD by publication, also known as “PhD by portfolio” or “PhD by published works,” is a relatively new route to completing your dissertation requirements for your doctoral degree. In the traditional dissertation route, you have Read more…

- Subject Guides

Academic writing: a practical guide

Dissertations.

- Academic writing

- The writing process

- Academic writing style

- Structure & cohesion

- Criticality in academic writing

- Working with evidence

- Referencing

- Assessment & feedback

- Reflective writing

- Examination writing

- Academic posters

- Feedback on Structure and Organisation

- Feedback on Argument, Analysis, and Critical Thinking

- Feedback on Writing Style and Clarity

- Feedback on Referencing and Research

- Feedback on Presentation and Proofreading

Dissertations are a part of many degree programmes, completed in the final year of undergraduate studies or the final months of a taught masters-level degree.

Introduction to dissertations

What is a dissertation.

A dissertation is usually a long-term project to produce a long-form piece of writing; think of it a little like an extended, structured assignment. In some subjects (typically the sciences), it might be called a project instead.

Work on an undergraduate dissertation is often spread out over the final year. For a masters dissertation, you'll start thinking about it early in your course and work on it throughout the year.

You might carry out your own original research, or base your dissertation on existing research literature or data sources - there are many possibilities.

What's different about a dissertation?

The main thing that sets a dissertation apart from your previous work is that it's an almost entirely independent project. You'll have some support from a supervisor, but you will spend a lot more time working on your own.

You'll also be working on your own topic that's different to your coursemate; you'll all produce a dissertation, but on different topics and, potentially, in very different ways.

Dissertations are also longer than a regular assignment, both in word count and the time that they take to complete. You'll usually have most of an academic year to work on one, and be required to produce thousands of words; that might seem like a lot, but both time and word count will disappear very quickly once you get started!

Find out more:

Key dissertation tools

Digital tools.

There are lots of tools, software and apps that can help you get through the dissertation process. Before you start, make sure you collect the key tools ready to:

- use your time efficiently

- organise yourself and your materials

- manage your writing

- be less stressed

Here's an overview of some useful tools:

Digital tools for your dissertation [Google Slides]

Setting up your document

Formatting and how you set up your document is also very important for a long piece of work like a dissertation, research project or thesis. Find tips and advice on our text processing guide:

University of York past Undergraduate and Masters dissertations

If you are a University of York student, you can access a selection of digitised undergraduate dissertations for certain subjects:

- History

- History of Art

- Social Policy and Social Work

The Library also has digitised Masters dissertations for the following subjects:

- Archaeology

- Centre for Eighteenth-Century Studies

- Centre for Medieval Studies

- Centre for Renaissance and Early Modern Studies

- Centre for Women's Studies

- English and Related Literature

- Health Sciences

- History of Art

- Hull York Medical School

- Language and Linguistic Science

- School for Business and Society

- School of Social and Political Sciences

Dissertation top tips

Many dissertations are structured into four key sections:

- introduction & literature review

There are many different types of dissertation, which don't all use this structure, so make sure you check your dissertation guidance. However, elements of these sections are common in all dissertation types.

Dissertations that are an extended literature review do not involve data collection, thus do not have a methods or result section. Instead they have chapters that explore concepts/theories and result in a conclusion section. Check your dissertation module handbook and all information given to see what your dissertation involves.

Introduction & literature review

The Introduction and Literature Review give the context for your dissertation:

- What topic did you investigate?

- What do we already know about this topic?

- What are your research questions and hypotheses?

Sometimes these are two separate sections, and sometimes the Literature Review is integrated into the Introduction. Check your guidelines to find out what you need to do.

Literature Review Top Tips [YouTube] | Literature Review Top Tips transcript [Google Doc]

The Method section tells the reader what you did and why.

- Include enough detail so that someone else could replicate your study.

- Visual elements can help present your method clearly. For example, summarise participant demographic data in a table or visualise the procedure in a diagram.

- Show critical analysis by justifying your choices. For example, why is your test/questionnaire/equipment appropriate for this study?

- If your study requires ethical approval, include these details in this section.

Methodology Top Tips [YouTube] | Methodology Top Tips transcript [Google Doc]

More resources to help you plan and write the methodology:

The Results tells us what you found out .