Daring Leadership Institute: a groundbreaking partnership that amplifies Brené Brown's empirically based, courage-building curriculum with BetterUp’s human transformation platform.

What is Coaching?

Types of Coaching

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Find your coach

-1.png)

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

How to write a speech that your audience remembers

Whether in a work meeting or at an investor panel, you might give a speech at some point. And no matter how excited you are about the opportunity, the experience can be nerve-wracking .

But feeling butterflies doesn’t mean you can’t give a great speech. With the proper preparation and a clear outline, apprehensive public speakers and natural wordsmiths alike can write and present a compelling message. Here’s how to write a good speech you’ll be proud to deliver.

What is good speech writing?

Good speech writing is the art of crafting words and ideas into a compelling, coherent, and memorable message that resonates with the audience. Here are some key elements of great speech writing:

- It begins with clearly understanding the speech's purpose and the audience it seeks to engage.

- A well-written speech clearly conveys its central message, ensuring that the audience understands and retains the key points.

- It is structured thoughtfully, with a captivating opening, a well-organized body, and a conclusion that reinforces the main message.

- Good speech writing embraces the power of engaging content, weaving in stories, examples, and relatable anecdotes to connect with the audience on both intellectual and emotional levels.

Ultimately, it is the combination of these elements, along with the authenticity and delivery of the speaker , that transforms words on a page into a powerful and impactful spoken narrative.

What makes a good speech?

A great speech includes several key qualities, but three fundamental elements make a speech truly effective:

Clarity and purpose

Remembering the audience, cohesive structure.

While other important factors make a speech a home run, these three elements are essential for writing an effective speech.

The main elements of a good speech

The main elements of a speech typically include:

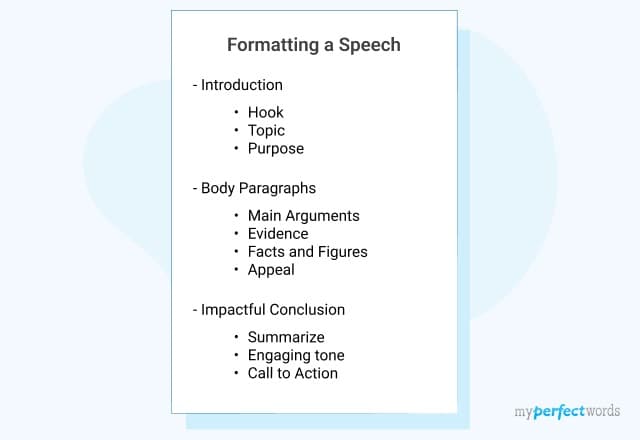

- Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your speech and grabs the audience's attention. It should include a hook or attention-grabbing opening, introduce the topic, and provide an overview of what will be covered.

- Opening/captivating statement: This is a strong statement that immediately engages the audience and creates curiosity about the speech topics.

- Thesis statement/central idea: The thesis statement or central idea is a concise statement that summarizes the main point or argument of your speech. It serves as a roadmap for the audience to understand what your speech is about.

- Body: The body of the speech is where you elaborate on your main points or arguments. Each point is typically supported by evidence, examples, statistics, or anecdotes. The body should be organized logically and coherently, with smooth transitions between the main points.

- Supporting evidence: This includes facts, data, research findings, expert opinions, or personal stories that support and strengthen your main points. Well-chosen and credible evidence enhances the persuasive power of your speech.

- Transitions: Transitions are phrases or statements that connect different parts of your speech, guiding the audience from one idea to the next. Effective transitions signal the shifts in topics or ideas and help maintain a smooth flow throughout the speech.

- Counterarguments and rebuttals (if applicable): If your speech involves addressing opposing viewpoints or counterarguments, you should acknowledge and address them. Presenting counterarguments makes your speech more persuasive and demonstrates critical thinking.

- Conclusion: The conclusion is the final part of your speech and should bring your message to a satisfying close. Summarize your main points, restate your thesis statement, and leave the audience with a memorable closing thought or call to action.

- Closing statement: This is the final statement that leaves a lasting impression and reinforces the main message of your speech. It can be a call to action, a thought-provoking question, a powerful quote, or a memorable anecdote.

- Delivery and presentation: How you deliver your speech is also an essential element to consider. Pay attention to your tone, body language, eye contact , voice modulation, and timing. Practice and rehearse your speech, and try using the 7-38-55 rule to ensure confident and effective delivery.

While the order and emphasis of these elements may vary depending on the type of speech and audience, these elements provide a framework for organizing and delivering a successful speech.

How to structure a good speech

You know what message you want to transmit, who you’re delivering it to, and even how you want to say it. But you need to know how to start, develop, and close a speech before writing it.

Think of a speech like an essay. It should have an introduction, conclusion, and body sections in between. This places ideas in a logical order that the audience can better understand and follow them. Learning how to make a speech with an outline gives your storytelling the scaffolding it needs to get its point across.

Here’s a general speech structure to guide your writing process:

- Explanation 1

- Explanation 2

- Explanation 3

How to write a compelling speech opener

Some research shows that engaged audiences pay attention for only 15 to 20 minutes at a time. Other estimates are even lower, citing that people stop listening intently in fewer than 10 minutes . If you make a good first impression at the beginning of your speech, you have a better chance of interesting your audience through the middle when attention spans fade.

Implementing the INTRO model can help grab and keep your audience’s attention as soon as you start speaking. This acronym stands for interest, need, timing, roadmap, and objectives, and it represents the key points you should hit in an opening.

Here’s what to include for each of these points:

- Interest : Introduce yourself or your topic concisely and speak with confidence . Write a compelling opening statement using relevant data or an anecdote that the audience can relate to.

- Needs : The audience is listening to you because they have something to learn. If you’re pitching a new app idea to a panel of investors, those potential partners want to discover more about your product and what they can earn from it. Read the room and gently remind them of the purpose of your speech.

- Timing : When appropriate, let your audience know how long you’ll speak. This lets listeners set expectations and keep tabs on their own attention span. If a weary audience member knows you’ll talk for 40 minutes, they can better manage their energy as that time goes on.

- Routemap : Give a brief overview of the three main points you’ll cover in your speech. If an audience member’s attention starts to drop off and they miss a few sentences, they can more easily get their bearings if they know the general outline of the presentation.

- Objectives : Tell the audience what you hope to achieve, encouraging them to listen to the end for the payout.

Writing the middle of a speech

The body of your speech is the most information-dense section. Facts, visual aids, PowerPoints — all this information meets an audience with a waning attention span. Sticking to the speech structure gives your message focus and keeps you from going off track, making everything you say as useful as possible.

Limit the middle of your speech to three points, and support them with no more than three explanations. Following this model organizes your thoughts and prevents you from offering more information than the audience can retain.

Using this section of the speech to make your presentation interactive can add interest and engage your audience. Try including a video or demonstration to break the monotony. A quick poll or survey also keeps the audience on their toes.

Wrapping the speech up

To you, restating your points at the end can feel repetitive and dull. You’ve practiced countless times and heard it all before. But repetition aids memory and learning , helping your audience retain what you’ve told them. Use your speech’s conclusion to summarize the main points with a few short sentences.

Try to end on a memorable note, like posing a motivational quote or a thoughtful question the audience can contemplate once they leave. In proposal or pitch-style speeches, consider landing on a call to action (CTA) that invites your audience to take the next step.

How to write a good speech

If public speaking gives you the jitters, you’re not alone. Roughly 80% of the population feels nervous before giving a speech, and another 10% percent experiences intense anxiety and sometimes even panic.

The fear of failure can cause procrastination and can cause you to put off your speechwriting process until the last minute. Finding the right words takes time and preparation, and if you’re already feeling nervous, starting from a blank page might seem even harder.

But putting in the effort despite your stress is worth it. Presenting a speech you worked hard on fosters authenticity and connects you to the subject matter, which can help your audience understand your points better. Human connection is all about honesty and vulnerability, and if you want to connect to the people you’re speaking to, they should see that in you.

1. Identify your objectives and target audience

Before diving into the writing process, find healthy coping strategies to help you stop worrying . Then you can define your speech’s purpose, think about your target audience, and start identifying your objectives. Here are some questions to ask yourself and ground your thinking :

- What purpose do I want my speech to achieve?

- What would it mean to me if I achieved the speech’s purpose?

- What audience am I writing for?

- What do I know about my audience?

- What values do I want to transmit?

- If the audience remembers one take-home message, what should it be?

- What do I want my audience to feel, think, or do after I finish speaking?

- What parts of my message could be confusing and require further explanation?

2. Know your audience

Understanding your audience is crucial for tailoring your speech effectively. Consider the demographics of your audience, their interests, and their expectations. For instance, if you're addressing a group of healthcare professionals, you'll want to use medical terminology and data that resonate with them. Conversely, if your audience is a group of young students, you'd adjust your content to be more relatable to their experiences and interests.

3. Choose a clear message

Your message should be the central idea that you want your audience to take away from your speech. Let's say you're giving a speech on climate change. Your clear message might be something like, "Individual actions can make a significant impact on mitigating climate change." Throughout your speech, all your points and examples should support this central message, reinforcing it for your audience.

4. Structure your speech

Organizing your speech properly keeps your audience engaged and helps them follow your ideas. The introduction should grab your audience's attention and introduce the topic. For example, if you're discussing space exploration, you could start with a fascinating fact about a recent space mission. In the body, you'd present your main points logically, such as the history of space exploration, its scientific significance, and future prospects. Finally, in the conclusion, you'd summarize your key points and reiterate the importance of space exploration in advancing human knowledge.

5. Use engaging content for clarity

Engaging content includes stories, anecdotes, statistics, and examples that illustrate your main points. For instance, if you're giving a speech about the importance of reading, you might share a personal story about how a particular book changed your perspective. You could also include statistics on the benefits of reading, such as improved cognitive abilities and empathy.

6. Maintain clarity and simplicity

It's essential to communicate your ideas clearly. Avoid using overly technical jargon or complex language that might confuse your audience. For example, if you're discussing a medical breakthrough with a non-medical audience, explain complex terms in simple, understandable language.

7. Practice and rehearse

Practice is key to delivering a great speech. Rehearse multiple times to refine your delivery, timing, and tone. Consider using a mirror or recording yourself to observe your body language and gestures. For instance, if you're giving a motivational speech, practice your gestures and expressions to convey enthusiasm and confidence.

8. Consider nonverbal communication

Your body language, tone of voice, and gestures should align with your message . If you're delivering a speech on leadership, maintain strong eye contact to convey authority and connection with your audience. A steady pace and varied tone can also enhance your speech's impact.

9. Engage your audience

Engaging your audience keeps them interested and attentive. Encourage interaction by asking thought-provoking questions or sharing relatable anecdotes. If you're giving a speech on teamwork, ask the audience to recall a time when teamwork led to a successful outcome, fostering engagement and connection.

10. Prepare for Q&A

Anticipate potential questions or objections your audience might have and prepare concise, well-informed responses. If you're delivering a speech on a controversial topic, such as healthcare reform, be ready to address common concerns, like the impact on healthcare costs or access to services, during the Q&A session.

By following these steps and incorporating examples that align with your specific speech topic and purpose, you can craft and deliver a compelling and impactful speech that resonates with your audience.

Tools for writing a great speech

There are several helpful tools available for speechwriting, both technological and communication-related. Here are a few examples:

- Word processing software: Tools like Microsoft Word, Google Docs, or other word processors provide a user-friendly environment for writing and editing speeches. They offer features like spell-checking, grammar correction, formatting options, and easy revision tracking.

- Presentation software: Software such as Microsoft PowerPoint or Google Slides is useful when creating visual aids to accompany your speech. These tools allow you to create engaging slideshows with text, images, charts, and videos to enhance your presentation.

- Speechwriting Templates: Online platforms or software offer pre-designed templates specifically for speechwriting. These templates provide guidance on structuring your speech and may include prompts for different sections like introductions, main points, and conclusions.

- Rhetorical devices and figures of speech: Rhetorical tools such as metaphors, similes, alliteration, and parallelism can add impact and persuasion to your speech. Resources like books, websites, or academic papers detailing various rhetorical devices can help you incorporate them effectively.

- Speechwriting apps: Mobile apps designed specifically for speechwriting can be helpful in organizing your thoughts, creating outlines, and composing a speech. These apps often provide features like voice recording, note-taking, and virtual prompts to keep you on track.

- Grammar and style checkers: Online tools or plugins like Grammarly or Hemingway Editor help improve the clarity and readability of your speech by checking for grammar, spelling, and style errors. They provide suggestions for sentence structure, word choice, and overall tone.

- Thesaurus and dictionary: Online or offline resources such as thesauruses and dictionaries help expand your vocabulary and find alternative words or phrases to express your ideas more effectively. They can also clarify meanings or provide context for unfamiliar terms.

- Online speechwriting communities: Joining online forums or communities focused on speechwriting can be beneficial for getting feedback, sharing ideas, and learning from experienced speechwriters. It's an opportunity to connect with like-minded individuals and improve your public speaking skills through collaboration.

Remember, while these tools can assist in the speechwriting process, it's essential to use them thoughtfully and adapt them to your specific needs and style. The most important aspect of speechwriting remains the creativity, authenticity, and connection with your audience that you bring to your speech.

5 tips for writing a speech

Behind every great speech is an excellent idea and a speaker who refined it. But a successful speech is about more than the initial words on the page, and there are a few more things you can do to help it land.

Here are five more tips for writing and practicing your speech:

1. Structure first, write second

If you start the writing process before organizing your thoughts, you may have to re-order, cut, and scrap the sentences you worked hard on. Save yourself some time by using a speech structure, like the one above, to order your talking points first. This can also help you identify unclear points or moments that disrupt your flow.

2. Do your homework

Data strengthens your argument with a scientific edge. Research your topic with an eye for attention-grabbing statistics, or look for findings you can use to support each point. If you’re pitching a product or service, pull information from company metrics that demonstrate past or potential successes.

Audience members will likely have questions, so learn all talking points inside and out. If you tell investors that your product will provide 12% returns, for example, come prepared with projections that support that statement.

3. Sound like yourself

Memorable speakers have distinct voices. Think of Martin Luther King Jr’s urgent, inspiring timbre or Oprah’s empathetic, personal tone . Establish your voice — one that aligns with your personality and values — and stick with it. If you’re a motivational speaker, keep your tone upbeat to inspire your audience . If you’re the CEO of a startup, try sounding assured but approachable.

4. Practice

As you practice a speech, you become more confident , gain a better handle on the material, and learn the outline so well that unexpected questions are less likely to trip you up. Practice in front of a colleague or friend for honest feedback about what you could change, and speak in front of the mirror to tweak your nonverbal communication and body language .

5. Remember to breathe

When you’re stressed, you breathe more rapidly . It can be challenging to talk normally when you can’t regulate your breath. Before your presentation, try some mindful breathing exercises so that when the day comes, you already have strategies that will calm you down and remain present . This can also help you control your voice and avoid speaking too quickly.

How to ghostwrite a great speech for someone else

Ghostwriting a speech requires a unique set of skills, as you're essentially writing a piece that will be delivered by someone else. Here are some tips on how to effectively ghostwrite a speech:

- Understand the speaker's voice and style : Begin by thoroughly understanding the speaker's personality, speaking style, and preferences. This includes their tone, humor, and any personal anecdotes they may want to include.

- Interview the speaker : Have a detailed conversation with the speaker to gather information about their speech's purpose, target audience, key messages, and any specific points they want to emphasize. Ask for personal stories or examples they may want to include.

- Research thoroughly : Research the topic to ensure you have a strong foundation of knowledge. This helps you craft a well-informed and credible speech.

- Create an outline : Develop a clear outline that includes the introduction, main points, supporting evidence, and a conclusion. Share this outline with the speaker for their input and approval.

- Write in the speaker's voice : While crafting the speech, maintain the speaker's voice and style. Use language and phrasing that feel natural to them. If they have a particular way of expressing ideas, incorporate that into the speech.

- Craft a captivating opening : Begin the speech with a compelling opening that grabs the audience's attention. This could be a relevant quote, an interesting fact, a personal anecdote, or a thought-provoking question.

- Organize content logically : Ensure the speech flows logically, with each point building on the previous one. Use transitions to guide the audience from one idea to the next smoothly.

- Incorporate engaging stories and examples : Include anecdotes, stories, and real-life examples that illustrate key points and make the speech relatable and memorable.

- Edit and revise : Edit the speech carefully for clarity, grammar, and coherence. Ensure the speech is the right length and aligns with the speaker's time constraints.

- Seek feedback : Share drafts of the speech with the speaker for their feedback and revisions. They may have specific changes or additions they'd like to make.

- Practice delivery : If possible, work with the speaker on their delivery. Practice the speech together, allowing the speaker to become familiar with the content and your writing style.

- Maintain confidentiality : As a ghostwriter, it's essential to respect the confidentiality and anonymity of the work. Do not disclose that you wrote the speech unless you have the speaker's permission to do so.

- Be flexible : Be open to making changes and revisions as per the speaker's preferences. Your goal is to make them look good and effectively convey their message.

- Meet deadlines : Stick to agreed-upon deadlines for drafts and revisions. Punctuality and reliability are essential in ghostwriting.

- Provide support : Support the speaker during their preparation and rehearsal process. This can include helping with cue cards, speech notes, or any other materials they need.

Remember that successful ghostwriting is about capturing the essence of the speaker while delivering a well-structured and engaging speech. Collaboration, communication, and adaptability are key to achieving this.

Give your best speech yet

Learn how to make a speech that’ll hold an audience’s attention by structuring your thoughts and practicing frequently. Put the effort into writing and preparing your content, and aim to improve your breathing, eye contact , and body language as you practice. The more you work on your speech, the more confident you’ll become.

The energy you invest in writing an effective speech will help your audience remember and connect to every concept. Remember: some life-changing philosophies have come from good speeches, so give your words a chance to resonate with others. You might even change their thinking.

Understand Yourself Better:

Big 5 Personality Test

Elizabeth Perry, ACC

Elizabeth Perry is a Coach Community Manager at BetterUp. She uses strategic engagement strategies to cultivate a learning community across a global network of Coaches through in-person and virtual experiences, technology-enabled platforms, and strategic coaching industry partnerships. With over 3 years of coaching experience and a certification in transformative leadership and life coaching from Sofia University, Elizabeth leverages transpersonal psychology expertise to help coaches and clients gain awareness of their behavioral and thought patterns, discover their purpose and passions, and elevate their potential. She is a lifelong student of psychology, personal growth, and human potential as well as an ICF-certified ACC transpersonal life and leadership Coach.

How to not be nervous for a presentation — 13 tips that work (really!)

Use a personal swot analysis to discover your strengths and weaknesses, put out-of-office messages to work for you when you’re away, is being ego driven damaging your career being purpose-driven is better, how to send a reminder email that’s professional and effective, what’s a vocation 8 tips for finding yours, setting goals for 2024 to ring in the new year right, create a networking plan in 7 easy steps, 9 elevator pitch examples for making a strong first impression, how to write an executive summary in 10 steps, 18 effective strategies to improve your communication skills, 8 tips to improve your public speaking skills, the importance of good speech: 5 tips to be more articulate, how to pitch ideas: 8 tips to captivate any audience, how to give a good presentation that captivates any audience, anxious about meetings learn how to run a meeting with these 10 tips, writing an elevator pitch about yourself: a how-to plus tips, 6 presentation skills and how to improve them, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead™

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care®

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case studies

- ROI of BetterUp

- What is coaching?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Personal Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- BetterUp Briefing

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Write a Professional Speech

5-minute read

- 7th May 2022

At some point in your professional career, you may find yourself with the daunting task of writing a speech. However, armed with the right information on how to write an engaging, attention-grabbing speech, you can rest assured that you’ll deliver a truly memorable one. Check out our guide below on how to write a professional speech that will successfully communicate your message and leave your audience feeling like they’ve truly learned something.

1.Understand your audience

Knowing your target audience can help guide you along the writing process. Learn as much as possible about them and the event you’re planning to speak at. Keep these key points in mind when you’re writing your speech.

● Who are they?

● Why are they here?

● What do they hope to learn?

● How much do they already know about my topic?

● What am I hoping to teach them?

● What interests them about my topic?

2. Research your topic

Perform in-depth research and analysis of your topic.

● Consider all angles and aspects.

● Think about the various ways you can discuss and debate the subject.

● Keep in mind why you’re passionate about the topic and what you’re hoping to achieve by discussing it.

● Determine how you can use the information gathered to connect the dots for your audience.

● Look for examples or statistics that will resonate with your audience.

● Sift through the research to pick out the most important points for your audience.

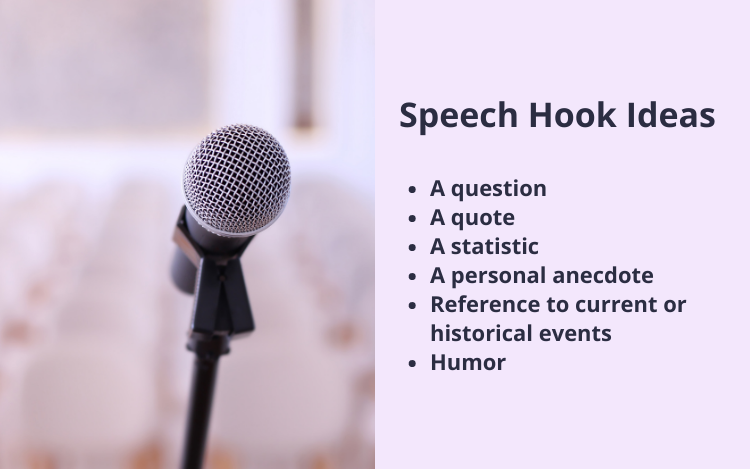

3. Create an opening hook

The first few minutes of your speech are paramount to its success. This is the moment when your audience truly pays attention and listens attentively.

● Start with a bold, persuasive opening statement that captures your audience’s attention.

● Ask a question to get them involved.

● Offer a shocking statistic or a powerful, well-known quote.

● Make a statement or rhetoric question and then pause for a moment, allowing them to grasp the gravity of what you’ve just said.

● Use a personal anecdote or life experience related to your topic to engage them.

4. Use an easy-to-grasp format

When you have the information you need, outline your speech in a way that your audience can easily follow.

● Start with what you plan to discuss in the speech.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● Go deeper into the details of the subject matter.

● Repeat what you’ve already mentioned in a few brief points.

● End with a strong statement that sums up what you were trying to achieve.

A typical structure should include:

● Introduction: Outline the main talking points of your speech.

● Body: Discuss these points in more detail, offer statistics, case studies, presentation aids, and other evidence to prove your theories.

● Conclusion: Wrap up your discussion with a bold message that leaves your audience feeling empowered, hopeful, and more knowledgeable about the topic.

5. Add some personality and humor

Remember to let your personality shine through. This speech is more than just words on a page. Allow the audience to feel your passion and vigor. Force them to think about the message you’re conveying.

● Share personal stories, fears, memories, or failures to help the audience relate to you as a person.

● Include some humor, jokes, puns, or limericks to give them a brief respite from the complex discussion.

● Offer well-known, popular, resounding quotes to help them acknowledge the significance of the topic.

5. Use anaphora for emphasis

Repetition is key in speeches. Realistically, you may lose your audience’s attention at times. By repeating key messages, they’ll be able to remember these vital takeaways despite drifting off somewhere in between. Anaphora allows you to repeat certain words or phrases in a clever, unique way that emphasizes your core message.

6. Keep it short and sweet

● Say what you need to in the shortest amount of time possible.

● You can’t realistically expect your audience to actively listen if you drone on and on.

● Provide clear, concise explanations and supporting examples or evidence.

7. Adopt presentation aids

People will quickly understand your message if you show them charts, tables, graphs, photos, or even regular household items .

8. Read it aloud

● This ensures you achieve a compelling tone of voice.

● It can also help you determine if the length is appropriate.

● Reading it aloud can also help you decide if you need to add more jokes, personal anecdotes, or even dramatic pauses and rhetoric questions.

9. End on a powerful note

End with a message that makes your reader feel inspired, motivated, and informed.

10. Proofread your speech

Finally, a well-researched speech riddled with errors, inconsistencies, and an ineffective tone of voice won’t help you achieve your ultimate goal – namely, to enlighten and educate your audience and have them walk away with the topic still playing on their mind. Have a friend or colleague read through your speech to highlight areas that require correction before you’re ready to present.

If you want to learn more about how we can help you write a powerful, resounding, and well-written speech, send us a free sample today.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

Free email newsletter template.

Promoting a brand means sharing valuable insights to connect more deeply with your audience, and...

6-minute read

How to Write a Nonprofit Grant Proposal

If you’re seeking funding to support your charitable endeavors as a nonprofit organization, you’ll need...

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Speak 2 Impress

No products in the cart.

Effective Speech Writing Format: A Comprehensive Guide and Examples

Staring at a blank page, trying to craft the perfect speech can feel like wandering in a maze without a map. It’s an experience many of us have faced, feeling that mix of frustration and determination.

My journey took a turn for the better when I joined Toastmasters International , where I uncovered valuable lessons on effective speech writing . In this blog post, I’m excited to share with you practical tips and real-life examples that will help you create captivating speeches .

Prepare to spark inspiration !

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways

- Crafting a speech starts with understanding its purpose , such as informing or persuading, and building a connection between the speaker and the audience.

- A clear structure with a captivating introduction , logical body, and strong conclusion makes speeches more engaging and easier for audiences to follow.

- Choosing impactful words and being authentic are key. Speakers should share personal stories in first person to build rapport.

- Rehearsing effectively involves practicing in parts, recording oneself, and getting feedback to improve delivery and body language.

- Different speech formats suit various academic levels and occasions, from simple storytelling for young learners to sophisticated arguments for college students.

Understanding the Speech Format

Understanding the Speech Format involves recognizing the purpose, structuring, word choice, and authenticity. It’s important to write in the first person and tailor towards effective communication.

Purpose of a speech

Every speech has a goal. I aim to inform, persuade, or move my audience emotionally. This guiding purpose shapes everything from the way I select my topic to how I deliver my words.

It’s about making an impact , leaving the audience with new knowledge , inspired feelings , or a changed perspective .

Crafting speeches is like building bridges between me and the listeners. My passion for the topic becomes clear as I talk about what matters to me and why it should matter to them too.

By focusing on this connection, I ensure that every word serves the speech’s main objective: to communicate effectively and make a lasting impression.

Importance of structuring a speech

Structuring a speech is essential for creating a clear and organized message . A well-structured speech helps to convey ideas in a logical sequence , making it easier for the audience to follow along.

It also ensures that key points are emphasized effectively, leading to better understanding and retention of the information being presented.

The structure sets the foundation for a successful speech, providing a roadmap that guides both the speaker and the audience through the presentation. By engaging in proper speech structuring techniques, speakers can build anticipation, maintain interest, and leave a lasting impact on their listeners.

Effective structure not only enhances the delivery but also adds credibility to your message.

Importance of word choice

Word choice is crucial when crafting a speech. The words I choose can either captivate the audience or leave them disengaged. By carefully selecting impactful and meaningful words , I can effectively convey my message to the audience.

Moreover, using precise language helps in clearly communicating my ideas and evoking emotions in the listeners. This not only enhances the overall impact of my speech but also ensures that my message resonates with the audience long after it’s delivered.

The selection of words plays an important role in how well your speech will be received by your audience. Each word has its own power and influence over the listener , so choosing them thoughtfully matters greatly!

The role of authenticity

Authenticity is crucial in speech writing . Being genuine and sincere can help you connect with your audience . When you speak from the heart , it’s easier for people to relate to your message.

Your passion for the topic shines through when you’re authentic, making your speech more engaging and impactful .

Writing in 1st person

As a beginner in public speaking , it’s important to write your speech from your own perspective. This means using “I” statements and sharing personal experiences or opinions to connect with the audience.

Being authentic and genuine allows you to build trust and credibility with your listeners, making your speech more impactful. When crafting your speech, think about what matters to you and why it’s important.

Use this passion to engage your audience and make a lasting impression.

Understanding how to write in the first person is crucial for building rapport with the audience . Sharing personal stories can help establish a connection and make your message more relatable.

By incorporating “I” statements, you can convey sincerity and authenticity in delivering your speech.

Tips for Writing a Successful Speech

Craft a captivating introduction to grab the audience’s attention and provide a compelling self-introduction, structuring your speech effectively for impact.

Self-introduction

Hi there, I’m Ryan Nelson . Born and raised in New York City , I used to struggle with public speaking too, especially during my time in graduate school. But after joining Toastmasters International and putting in a lot of practice, everything changed for me.

Now, I teach others how to speak confidently because I believe that stepping out of your comfort zone can lead to success.

Crafting an attention-grabbing opening statement

Crafting an attention-grabbing opening statement sets the stage for your speech. Your first words should hook the audience and make them want to listen. Start with a surprising fact or a thought-provoking question to grab their attention right from the beginning.

Use impactful words and vivid imagery to paint a picture in their minds. Remember , you only have one chance to make a first impression, so make it count. By captivating your audience from the start, you set yourself up for success throughout your speech.

To create an engaging opening statement, consider using storytelling techniques tailored towards connecting with your audience emotionally and intellectually . Effective public speaking involves not only expressing your topic clearly but also capturing the listeners’ curiosity right away with compelling content and delivery style.

Structuring the speech effectively

When crafting a speech, ensure it has a clear introduction, body, and conclusion to maintain the audience’s interest.

- Start with a compelling opening statement to grab the attention of your listeners.

- Organize your ideas logically in the body paragraphs to facilitate understanding and retention.

- Use transitional words or phrases to smoothly move from one point to another for coherence.

- Conclude the speech by summarizing the key points and providing a memorable closing statement that resonates with the audience.

- Rehearse your speech multiple times to ensure fluency and confidence in delivering it effectively.

Now, let’s move on to “Choosing impactful words” in our effective speech writing format.

Choosing impactful words

Transitioning from structuring the speech effectively to choosing impactful words is crucial. Every word counts in a speech, shaping its impact and resonance. The right words can captivate an audience , evoke emotions , and inspire action .

Therefore, it’s essential to meticulously select words that resonate with the audience’s values and emotions while conveying authenticity and passion for the topic. It’s all about connecting with your listeners on a profound level through carefully chosen language that resonates powerfully.

Being authentic and genuine

Transitioning from choosing impactful words to being authentic and genuine , let’s delve into the importance of speaking from the heart . It’s essential to be true to yourself when delivering a speech, showing genuine passion for your topic and connecting with your audience on a personal level.

Being authentic and genuine not only builds trust but also makes your speech more engaging and impactful. Remember, public speaking is about sharing your unique perspective in a sincere and truthful manner while maintaining an open and honest presence on stage.

Frequently Asked Questions about Speech Writing

– Why introduce ourselves in a speech?

– Tips for effective speech rehearsals ?

Why is it important to introduce ourselves?

Introducing ourselves at the beginning of a speech helps to build a connection with the audience. It creates a sense of familiarity and trust , making it easier for listeners to relate to what we have to say.

Sharing our background and experience also adds credibility to our message, showing that we are qualified to speak on the topic. Moreover, it sets the stage for open communication and engagement , paving the way for a more interactive and memorable speech experience.

It’s not just about sharing basic details – it’s about building rapport and establishing mutual understanding from the start.

How to rehearse a speech effectively?

When it comes to rehearsing a speech effectively, the key is practice . Start by breaking down your speech into smaller sections and practicing each part separately. Record yourself and listen back to identify areas for improvement.

Additionally, rehearse in front of a mirror or with a trusted friend for feedback. Ensure that your body language aligns with your message and rehearse emphasizing important points.

By doing so, you will gain confidence and deliver a polished speech .

What are some examples of effective speech writing formats for different academic levels and occasions?

As a public speaking beginner, here are some effective speech writing formats for different academic levels and occasions:

- Academic Levels :

- For Elementary School : Use simple language, storytelling, and interactive elements to engage young audiences.

- For High School : Incorporate persuasive techniques, logical arguments, and relatable examples to resonate with teenage audiences.

- For College : Employ well-researched content, critical thinking, and sophisticated language to address academic audiences.

- Occasions :

- Informative Speech : Provide clear explanations, factual evidence, and educational content when addressing informative topics or events.

- Persuasive Speech : Utilize strong arguments, emotional appeals, and compelling evidence to persuade the audience on a specific viewpoint or action.

- Special Events (e.g., Graduation) : Blend inspiration, personal experiences, and future aspirations to uplift and motivate the audience during celebratory occasions.

- Professional Settings :

- Business Presentations : Focus on data-driven insights, professional demeanor, and clear communication for corporate settings.

- Political Speeches : Utilize rhetorical devices, policy discussions, and public engagement strategies to convey political agendas effectively.

- Social Causes :

- Advocacy Speeches : Integrate powerful narratives, empathy-building stories, and calls to action for raising awareness about social issues.

- Charity Events : Emphasize compassion-driven messages, success stories of impact, and calls for community support in fundraising events.

- Cultural Celebrations :

- Multicultural Events : Embrace diversity through respectful language use, cultural appreciation statements, and inclusive messaging to honor various traditions.

Effective speech writing is a powerful skill . Let’s introduce Dr. Lisa Chang, a celebrated speech coach with over two decades of experience. Dr. Chang holds a Ph.D. in Communication from Harvard University and has helped thousands to master public speaking.

Dr. Chang speaks highly of studying and applying effective speech formats. She notes that the right structure can engage audiences deeply, making any topic memorable.

She also stresses ethical storytelling and authenticity in speeches. For her, clear, truthful presentations build trust with listeners.

For everyday use or special occasions, Dr. Chang suggests practicing speeches out loud and revising often for clarity and impact.

In assessing this guide against others, she praises its practical examples but reminds us to adapt advice to our unique style.

Dr. Chang believes this guide serves as an excellent tool for beginners eager to improve their public speaking skills.

Ryan Nelson is the founder of Speak2Impress, a platform dedicated to helping individuals master the art of public speaking. Despite having a crippling fear of public speaking for many years, Ryan overcame his anxiety through diligent practice and active participation in Toastmasters. Now residing in New York City, he is passionate about sharing his journey and techniques to empower others to speak with confidence and clarity.

Similar Posts

Crafting a Heartfelt Eulogy for Sisters: A Step-By-Step Guide

Crafting a eulogy for a sister is no easy task. Speaking from personal experience, navigating the sea of emotions, while…

10 Heartfelt Poems for Funeral Programs to Honor Your Loved Ones

Searching for the right words to honor a loved one who has passed can feel overwhelming. It’s a challenge many…

10 Effective Public Speaking Exercises for Practice and Improvement

Standing in front of a crowd used to send my heart racing. It felt like stepping onto a stage with…

Crafting a Meaningful Leaving Speech for Colleague: Examples and Tips

Crafting a farewell speech for a colleague can feel overwhelmingly challenging at times. In my own journey to find the…

Tips for Crafting an Unforgettable Speech for Your Christmas Party

Staring at a blank page, trying to come up with the perfect words for your Christmas party speech? Believe me,…

Sample Eulogy for Mother from Daughter: Honoring Her Legacy and Love

Crafting a eulogy for your mother feels like trying to scale an emotional Everest. I faced this daunting task myself…

Unsupported browser

This site was designed for modern browsers and tested with Internet Explorer version 10 and later.

It may not look or work correctly on your browser.

- Presentations

- Public Speaking

The Best Source for PowerPoint Templates (With Unlimited Use)

Before we dive into how to make a speech, let's look at a powerful tool that can help you design your presentation.

Envato Elements is a great place to find PowerPoint templates to use with your speech. These presentation templates are professionally designed to impress.

Envato Elements is an excellent value because you get unlimited access to digital elements once you become a subscriber. Envato Elements has more than just presentation templates . You get:

- stock images

- and much more

To become a subscriber, just sign up and pay a low monthly fee.

Sample Public Speaking Scenario

Here's a possible public speaking scenario:

You've just opened a small web design business in your town, and you join the town Chamber of Commerce. As a result, you're invited to give a short, five-minute presentation at the next Chamber of Commerce meeting.

Coming up with a public speaking speech for the scenario described above could be a challenge if you've never written or given a public speech before. Fortunately, there are some speech-writing steps that you can use that'll make speech writing easier.

Let's use this example and walk through the steps for writing a speech.

7 Steps for Writing a Speech

The steps for writing a speech for public speaking are like the steps for writing a presentation in general. But at each stage of the writing process, you need to keep your audience in mind:

1. Research Your Audience

Whenever you do any type of writing you need to consider who you're trying to reach with your writing. Speech writing is no different. The more you know about your target audience, the more effective your writing will be.

In the example above, you know that your audience is going to be the other members of the Chamber of Commerce. They're likely to be small business owners just like you are.

What to Do After You Research Your Audience:

Once you've defined your audience, you can gear your speech towards them. To do this, ask yourself questions like:

- What does this audience need?

- What problem can I solve for them?

- Is there anything else I need to consider about my listeners?

In the example we're using for this tutorial, most small businesses in your town fit one of the following three situations:

- They've got a website that works well.

- They've got a website, but the design is outdated or doesn't work well.

- They don't have a website.

2. Select a Topic

In this example your topic is already given. You've been invited to introduce your business. But you also know that the speech is going to be fairly short--only five minutes long.

While it's always a good idea to keep a speech focused, this is especially important for a short speech.

If I were writing the public speaking speech for the scenario we're working with, I'd narrow the topic down like this:

- Create a list of the strengths of my business.

- Compare the list of business strengths to the problems I observed with the other members' websites in the previous step.

- Focus my presentation on the areas where my business strengths meet weaknesses (needs) of other Chamber of Commerce members.

Let's say that I noticed that quite a few members of the chamber have websites that use outdated fonts, and the sites aren't mobile-friendly. Instead of listing everything my web design business could possibly do, I'd focus my short speech on those areas where I observed a need.

You can use a similar process to narrow the topic down any time you need to write a speech.

Avoid the temptation of trying to cover too much information. Most people are so overwhelmed by the sheer amount of new data they receive each day that they can't keep up with it all. Your listeners are more likely to remember your public speaking speech if it's tightly focused on one or two points.

3. Research Your Topic

In the example we've been going over, you probably don't need to do a lot of research. And you've already narrowed your topic down.

But some public speaking situations may require that that you cover a topic that you're less familiar with. For more detailed speech writing tips on how to study your subject (and other public speaking tips), review the tutorial:

.jpg)

4. Write Your Speech

Once you've completed the steps above, you're ready to write your speech. Here are some basic speech writing tips:

- Begin with an outline . To create a speech your audience will remember, you've got to be organized. An outline is one of the best ways to organize your thoughts.

- Use a conversational tone . Write your speech the way you would normally talk. Work in some small talk or humor, if appropriate.

- Use the speaker notes . Typically, speaker notes aren't seen by the audience. So, this is a good place to put reminders to yourself.

- Be specific . It's better to give examples or statistics to support a point than it is to make a vague statement.

- Use short sentences . It's likely you're not going to give your speech word for word anyway. Shorter sentences are easier to remember.

In this example scenario for the short speech we're preparing for the Chamber of Commerce, your outline could look something like this:

- Introduction . Give your name and the name of your business. (Show title slide of website home page with URL)

- Type of Business . Describe what you do in a sentence or two. (Show slide with bulleted list)

- Give example of a recent web design project . Emphasize areas that you know the other businesses need. (Show slides with examples)

- Conclusion. Let the audience know that you'd be happy to help with their web design needs. Offer to talk to anyone who's interested after the meeting. (Show closing slide that includes contact information)

- Give out handouts . Many presentation software packages allow you to print out your speech as a handout. For a networking-type presentation like the one in our example, this can be a good idea since it gives your listeners something to take with them that's got your contact information on it.

That simple speech format should be enough for the short speech in our example. If you find it's too short when you practice, you can always add more slides with examples.

If you've been asked to give a short speech, you can change the speech format above to fit your needs. If you're giving a longer speech, be sure to plan for audience breaks and question and answer sessions as you write.

5. Select a Presentation Tool

For most presentations, you'll want to use a professional presentation tool such as PowerPoint, Google Slides, or a similar package. A presentation tool allows you to add visual interest to your public speaking speech. Many of them allow you to add video or audio to further engage your audience.

If you don't already have a presentation tool, these tutorials can help you find the right one for your needs:

Once you've chosen a presentation tool, you're ready to choose a template for your presentation.

6. Select a Template and Finish

A presentation template controls the look and feel of your presentation. A good template design can make the difference between a memorable public speech with eye-catching graphics and a dull, forgettable talk.

You could design your own presentation template from scratch. But, if you've never designed a presentation template before, the result might look less than professional. And it could take a long time to get a good template. Plus, hiring a designer to create an original presentation template can be pricey.

A smart shortcut for most small business owners is to invest in a professional presentation template. They can customize it to fit with their branding and marketing materials. If you choose this option, you'll save time and money. Plus, with a professional presentation template you get a proven result.

You can find some great-looking presentation templates at Envato Elements or GraphicRiver . To browse through some example templates, look at these articles:

Even a short speech like the one we've been using as an example in this tutorial could benefit from a good tutorial. If you've never used a template before, these PowerPoint tutorials can help:

7. How to Make a Public Speech

Now that you've completed all the steps above, you're ready to give your speech. Before you give your speech publicly, though, there are a few things you should remember:

- Don't read your speech . If you can, memorize your speech. If you can't, it's okay to use note cards or even your outline--but don't read those either. Just refer to them if you get stuck.

- Practice . Practice helps you get more comfortable with your speech. It'll also help you determine how your speech fits into the time slot you've been allotted.

- Do use visual aids . Of course, your presentation template adds a visual element to your public speech. But if other visual aids work with your presentation, they can be helpful as well.

- Dress comfortably, but professionally . The key is to fit in. If you're not sure how others at your meeting will be dressed, contact the organizer and ask.

- Speak and stand naturally . It's normal to be a little nervous but try to act as naturally as you can. Even if you make a mistake, keep going. Your audience probably won't even notice.

- Be enthusiastic . Excitement is contagious. If you're excited about your topic, your audience will likely be excited too.

In the example we're using in this tutorial (and with many public speaking opportunities), it's important not to disappear at the end of the meeting. Stick around and be prepared to interact individually with members of the audience. Have answers to questions anyone might have about your speech. And be sure to bring a stack of business cards to pass out.

5 Quick Tips to Make a Good Speech Great (& More Memorable)

After reading about the basics, here are some more tips on how to write a great speech really stand out:

1. Have a Strong Opening

Start your speech with a strong opening by presenting surprising facts or statistics. You could even start with a funny story or grand idea.

Another way to start your speech is to open with a question to spark your audience’s curiosity. If you engage your audience early in your speech, they're more likely to pay attention throughout your speech.

2. Connect With Your Audience

You want a speech that'll be memorable. One way to make your speech memorable is to connect with your audience. Using metaphors and analogies help your audience to connect and remember. For example, people use one writing tool to put the speech's theme in a 15-20 word short poem or memorable paragraph, then build your speech around it.

3. Have a Clear Structure

When writing your speech, have a clear path and a destination. Otherwise, you could have a disorganized speech. Messy speeches are unprofessional and forgettable. While writing your speech, leave out unnecessary information. Too many unnecessary details can cause people to lose focus.

4. Repeat Important Information

A key to writing memorable speeches is to repeat key phrases, words, and themes. When writing your speech, always bring your points back to your main point or theme. Repetition helps people remember your speech and drives home the topic of your speech.

5. Have a Strong Closing

Since the last thing that your audience listened to what your closing, they'll remember your closing the most. So, if your closing is forgettable, it can make your speech forgettable. So, recap your speech and repeat essential facts that you want the audience to remember in your closing.

Five PowerPoint Presentation Templates (From Envato Elements - For 2022)

If you’re writing a speech for a presentation, save time by using a premium presentation template:

1. Toetiec PowerPoint Presentation

Toetic PowerPoint Presentation has 90 unique slides and 1800 total slides that you can easily add your information onto. There are ten light and dark versions that come with this template. Also included in this template are vector icons, elements, and maps.

2. Suflen Multipurpose Presentation

Suflen Multipurpose Presentation template has a professional design that can work for any presentation topic. This template comes with over 450 total slides. With this template, you've got five color themes to choose from. Also, this template comes with illustrations, graphics, and picture placeholders.

3. Virtually PowerPoint

Virtually PowerPoint template is a modern and minimal style presentation template. This template comes with over 50 slides. You can use this template for any presentation theme.

4. Amarish PowerPoint Template

Amarish PowerPoint Template comes with five color themes that allow you to choose the color you want. This template is another multipurpose template that can work for any purpose. Also, this template comes with over 150 total slides and infographics, illustrations, and graphics.

5. Qubica PowerPoint Template

Qubica PowerPoint Template comes with over 150 total slides and five premade color themes. Easily add images into your presentation template by dragging the image of your choice into the picture placeholder. Everything in this template is entirely editable.

Learn More About How to Write a Great Speech

Here are some other tutorials that provide more information on giving a speech:

Learn More About Making Great Presentations

Download The Complete Guide to Making Great Presentations eBook now for FREE with a subscription to the Tuts+ Business Newsletter. Get your ideas formed into a powerful presentation that'll move your audience!

Make Your Next Speech Your Best Ever!

You've just learned how to write a good public speaking speech. You've been given a sample speech format and plenty of other speech writing tips and resources on how to write a good speech. You've seen some templates that'll really make a PowerPoint stand out.

Now, it's up to you to write the best speech for your needs. Good luck!

Editorial Note: This post has been updated with contributions from Sarah Joy . Sarah is a freelance instructor for Envato Tuts+.

How To Write A Speech That Inspires You Audience: 13 Steps

Learn how to write a speech that will effectively reach your audience.

A good speech is a powerful tool. Effective speeches make people powerful, whether in the hands of a world leader trying to get people to believe their ideology or in the mouth of a teacher trying to inspire students. A well-written speech can lift the hearts of a nation in times of war, inspire people to action when complacency is commonplace, honor someone who has died, and even change a nation’s mind on a particular topic, which, in turn, can change history.

Excellent speech writing is a skill that you must learn. While public speaking may come naturally to some people, the sentence structure and nuances of a powerful speech are something you must learn if you are going to gain the audience’s attention.

So how can you learn how to write a speech? The writing process is a little different than the process you’d use to write a paper or essay, so here is a guide that can help.

Materials Needed

Step 1: define your purpose, step 2: determine your audience, step 3: start your research, step 4: choose the right length, step 5: create an outline, step 6: craft the introduction, step 7: write the body, step 8: use transitions, step 9: conclude your speech, step 10: add some spice, step 11. implement spoken language, step 12: edit your speech, step 13: read it out.

- Research materials

- Audience demographic information

Before you can write a speech, you must know the purpose of your speech. You can deliver many types of speeches, and the purpose will determine which one you are giving. While there may be more than these, here are some common types of speeches:

- Informative speech: An informative speech strives to educate the audience on a topic or message. This is the type of speech a teacher gives when delivering a lecture. “ First World Problems ” by Sarah Kwon is an excellent example of an informative speech.

- Entertaining speech: This speech strives to amuse the audience. These are typically short speeches with funny, personal stories woven in. A wedding guest giving a speech at a wedding may be an example of this type of speech.

- Demonstrative speech: This speech demonstrates how to do something to the audience. A company showing how to use a product is delivering this type of speech.

- Persuasive speech: This speech aims to persuade the audience of your particular opinion. Political speeches are commonly persuasive. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s famous “ I Have a Dream ” speech is an example of a persuasive speech, as it called the government to make changes that protected civil and economic rights.

- Oratorical speech: An oratory is a formal speech at an event like a funeral or graduation. The goal is to express an opinion and inspire the audience, but not necessarily to persuade.

- Motivational speech: These speeches inspire people to take action, such as to improve themselves or to feel better and happier. For example, a coach may deliver this kind of speech to his players during halftime to inspire them to win the game. Steve Jobs’ 2005 Stanford Commencement Address is an excellent example of a motivational speech.

- Eulogy: A Eulogy is a funeral speech. This speech is given to the mourners at someone’s funeral and talks about the excellent character rates of the person who died. “ Eulogy for Rosa Parks ” is a famous example of this type of speech given by Oprah Winfrey in 2015.

- Explanatory speech: This final speech type describes a situation or item. These speeches often have step-by-step instructions on how to do a particular thing.

Your audience members are an essential part of the speech writing process. Consider taking notes about your audience before you start writing your speech. You can even make a fake audience member you are writing toward as you prepare your speech. Even though they do not directly impact what you talk about, they should impact how you talk about it. Therefore, you must write your speech to reach that particular audience.

For example, if you are writing a speech for an audience that does not agree with you, you will need to bring more facts and figures to persuade them of your opinion. On the other hand, if you are writing a speech for an audience already on your side, you must encourage them to hold the line. To get to know your audience, consider factors like:

- Income level

- Pain points

- Questions they might ask

Before you outline or write your speech, you must know some facts about the big idea or speech topic. So perform some research, and take notes. See if you can find any new or surprising information in your research. If it was new and surprising, it also might be to your audience members. You can use this research to make the essential points of your piece.

Finally, know the required length of your speech. Speeches usually have time limits, not word count limits. You will need to know the desired length before you can start writing the speech, or you will end up with a speech that is too long or too short. The length of your speech will vary depending on where you are giving it and who your audience is.

Generally, a 20-minute speech is standard when delivering a speech to adults in a professional or academic setting. However, if you are a student who is preparing a speech for a classroom, you may be limited to three to five minutes. Sometimes speakers will get booked to take on a 60-minute session, but if you talk for 60 minutes, you will lose the attention of some of your audience members.

Remember, some of the most famous speeches in history are very short. President Abraham Lincoln’s “ Gettysburg Address ” was less than 300 words long and took less than two minutes to deliver. President Franklin Roosevelt’s “ Day of Infamy ” speech lasted less than 10 minutes. However, knowing your speech’s length can be challenging after you prepare it. Generally, a double-spaced page of writing will take about 90 seconds to speak. Thus, a 20-minute speech will take about 13 typed, double-spaced pages if you type out your entire speech.

Consider using a words-to-minutes calculator to determine how long your speech likely is. Remember that the average English speaker speaks 140 words a minute. You may get up to 170 words a minute if you speak fast. If your speech is slow, it may be as little as 110 words a minute.

Now you are ready to start writing. Before you write a speech, you must create an outline. Some public speakers will speak from an outline alone, while others will write their speech word-for-word. Both strategies can lead to a successful speech, but both also start with an outline. Your speech’s outline will follow this template:

- Introduction: Introduces your main idea and hooks the reader’s attention.

- Body: Covers two to three main points with transitions.

- Conclusion: Summarizes the speech’s points and drive home your main message.

As you fill in these areas, answer these questions: Who? What? Why? and How? This will ensure you cover all the essential elements your listeners need to hear to understand your topic. Next, make your outline as detailed as you can. Organize your research into points and subpoints. The more detail on your outline, the easier it will be to write the speech and deliver it confidently.

As you prepare your speech, your introduction is where you should spend the most time and think. You only have moments to capture your audience’s attention or see them zone out in front of you. However, if you do it right, you will cause them to turn to you for more information on the topic. In other words, the introduction to a speech may be the most memorable part, so it deserves your attention. Therefore, you must have three main parts:

- Hook: The hook is a rhetorical question, funny story, personal anecdote, or shocking statistic that grabs the listener’s attention and shows them why your speech is worth listening to.

- Thesis: This is your main idea or clear point.

- Road map: You will want to preview your speech outline in the introduction.

Here is an example of a good introduction for a persuasive speech from Jamie Oliver’s TED Talk about children and food:

“Sadly, in the next 18 minutes when I do our chat, four Americans that are alive will be dead from the food that they eat.”

This shocking statistic gets the audience’s attention immediately. In his speech, Oliver details why America’s food choices are so poor, how it affects them, and how we can teach children to do better.

Here is an example of an informative speech about pollution and what can be done about it. This introduction follows the template perfectly.

“I want you to close your eyes for a minute and picture a beautiful oceanfront. The sound of the waves crashing on the sand while seagulls fly overhead. Do you have it? Now I am going to say one word that will destroy that image: Pollution. What changed in your mental picture? Do you now see sea turtles with bottles on their head or piles of debris washing on shore? Marine pollution is a massive problem because plastic does not decompose. Not only does it use up many resources to create, but it rarely gets disposed of properly. We must protect our natural areas, like that beautiful beach. Today I am going to show you how destructive the effects of plastic can be, how it is managing our natural resources, and what steps we can take to improve the situation.”

Now you are ready to write the body of your speech. Draw from your research and flesh out the points stated in your introduction. As you create your body, use short sentences. People can’t listen as long as they can read, so short and sweet sentences are most effective. Continuing the theme of the marine pollution speech, consider this body paragraph.

“You might be thinking plastic isn’t a big deal. Let’s think for a minute that you’re at the beach drinking bottled water. According to “The Problem with Plastic,” an article by Hannah Elisbury, one out of every six plastic water bottles ends up in recycling. The rest become landfill fodder. Worse, many get dropped in nature. Perhaps you are packing up at the end of your beach trip and forget to grab your bottle. Maybe your kid is buried in the sand. Now it’s adding pollutants to the water. That water becomes part of the drinking water supply. It also becomes part of the fish you eat at your favorite seafood restaurant. Just one bottle has big consequences.”

As you write the body, don’t stress making every word perfect. You will revise it later. The main goal is to get your ideas on paper or screen. This body paragraph is effective for two reasons. First, the audience members likely use water bottles, which resonates with them. Second, she uses a resource and names it, which gives your work authority.

It would be best to use transitions to move from each speech section. This keeps the audience engaged and interested. In addition, the transitions should naturally merge into the next section of the speech without abruptness. To transition between points or ideas, use transition words. Some examples include:

- Coupled with

- Following this

- Additionally

- Comparatively

- Correspondingly

- Identically

- In contrast

- For example

You can also use sequence words, like first, second, third, etc., to give the idea of transition from one thought to the next. Make sure your speech has several transition words to drive it through to completion and to keep the audience engaged.

In his speech “ Their Finest Hour ,” Winston Churchill uses transitions well. Here is an excerpt from his conclusion:

“ But if we fail, then the whole world, including the United States, including all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new Dark Age made more sinister, perhaps more protracted, by the lights of perverted science. Therefore, let us brace ourselves to our duties and bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, “This was their finest hour.”

Notice that he uses “therefore,” “so,” and “but.” Each of these transition words effectively moves the speech along.

Your conclusion needs to restate your thesis but differently. It should personalize the speech to the audience, restate your main points and state any key takeaways. Finally, it should leave the audience with a thought to ponder.

Here are some practical ways to end a speech:

- Use a story

- Read a poem

- State an inspirational quote

- Summarize the main points

- Deliver a call to action

Here are some examples of fantastic conclusions:

- Here is an excellent example of a concluding statement for an inspirational graduation speech: “As you graduate, you will face great challenges, but you will also have great opportunities. By embracing all that you have learned here, you will meet them head-on. The best is yet to come!”

- A CEO that is trying to inspire his workforce might conclude a speech like this: “While the past year had challenges and difficulties, I saw you work through them and come out ahead. As we move into the next year, I am confident we will continue to excel. Let’s join hands, and together this can be the best year in company history!”

- In “T he Speech to Go to the Moon, ” President Kennedy concluded this way: “ Many years ago the great British explorer George Mallory, who was to die on Mount Everest, was asked why did he want to climb it. He said, “Because it is there. Well, space is there, and we’re going to climb it, and the moon and the planets are there, and new hopes for knowledge and peace are there. And, therefore, as we set sail we ask God’s blessing on the most hazardous and dangerous and greatest adventure on which man has ever embarked.” Many speechwriters say something like “in conclusion” or “that’s all I have for you today.” This is not necessary. Saying “in conclusion” could cause your audience to stop listening as they anticipate the end of the speech, and stating that you have said all you need to say is just unnecessary.

Now that you have the basic structure, you’re ready to add some spice to your speech. Remember, you aren’t reading a research essay. Instead, you are making an exciting and engaging spoken presentation. Here are some ideas:

- Consider giving your speech some rhythm. For example, change the wording, so it has a pace and cadence.

- Work to remove a passive voice from your sentences where possible. Active speaking is more powerful than passive.

- Use rhetorical questions throughout because they make the listener stop and think for a moment about what you are saying.

- Weave some quotes into your speech. Pulling famous words from other people will make your speech more interesting.

- Where possible, use personal stories. This helps your audience engage with you as the speaker while keeping the speech interesting.

You may not use all of these ideas in your speech, but find some that will work for the type of speech you plan to give. They will make it more exciting and help keep listeners engaged in what you are saying.

Writing a speech is not like writing a paper. While you want to sound educated with proper grammar , you need to write in the way you speak. For many people, this is much different from the way they write. Not only will you use short sentences, but you will also use:

- Familiar vocabulary: This is not the time to start adding scientific terminology to the mix or jargon for your industry that the audience won’t understand. Use familiar vocabulary.

- Transitions: Already discussed, but spoken language uses many transition words. Your speech should, too.

- Personal pronouns: “You” and “I” are acceptable in a speech but not in academic writing.

- Colloquialisms: Colloquialisms are perfectly acceptable in a speech, provided the audience would readily understand them.