- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Grammar Coach ™

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

Advertisement

[ rep-ri- zent ]

verb (used with object)

In this painting the cat represents evil and the bird, good.

Synonyms: exemplify

to represent musical sounds by notes.

He represents the company in Boston.

to represent one's government in a foreign country.

He represents Chicago's third Congressional district.

The painting represents him as a man 22 years old.

Synonyms: delineate

- to present or picture to the mind.

- to present in words; set forth; describe; state.

The article represented the dictator as a benevolent despot.

- to set forth clearly or earnestly with a view to influencing opinion or action or making protest.

- to present, produce, or perform, as on a stage.

Synonyms: portray

a genus represented by two species.

The llama of the New World represents the camel of the Old World.

verb (used without object)

- to protest; make representations against.

The gang members always represent when they see one another.

/ ˌrɛprɪˈzɛnt /

our tent represents home to us when we go camping

- to act as a substitute or proxy (for)

an MP represents his constituency

letters represent the sounds of speech

romanticism in music is represented by Beethoven

- to present an image of through the medium of a picture or sculpture; portray

- to bring clearly before the mind

- to set forth in words; state or explain

he represented her as a saint

- to act out the part of on stage; portray

- to perform or produce (a play); stage

Discover More

Derived forms.

- ˌrepreˌsentaˈbility , noun

- ˌrepreˈsentable , adjective

Other Words From

- repre·senta·ble adjective

- repre·senta·bili·ty noun

- nonrep·re·senta·ble adjective

- prerep·re·sent verb (used with object)

- unrep·re·senta·ble adjective

Word History and Origins

Origin of represent 1

Example Sentences

A second round of more than 30 grants is in the works, representing over $2 million more.

Heliocene represents the moment when another life form figured out a way to tap into the potential of the sun, and adopts a name for our epoch that better centers humans within the spheres that hold us.

The suit was filed by the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press attorneys, who are representing the Blade in the case.

He said the city manager invited him to be on a review panel in October to represent the LGBTQ community in Oceanside but hasn’t heard back on details.

Each column represents a different castle, while each row is a strategy, with the strongest performers on top and the weakest on the bottom.

More to the point, Huckabee has a natural appeal to a party that has come to represent the bulk of working class white voters.

Republicans loathe public sector unions—unless they represent cops or firefighters.

This year will represent the 20th anniversary of the first Running of the Santas.

For example, 51 percent of North Carolinians voted that year for a Democrat to represent them in Congress.

In their elitism and sense of entitlement, they represent much of what liberals are supposed to despise.

Little girls perhaps represent the attractive function of adornment: they like to be thought pretty.

A child's attempt to represent a man appears commonly to begin by drawing a sort of circle for the front view of the head.

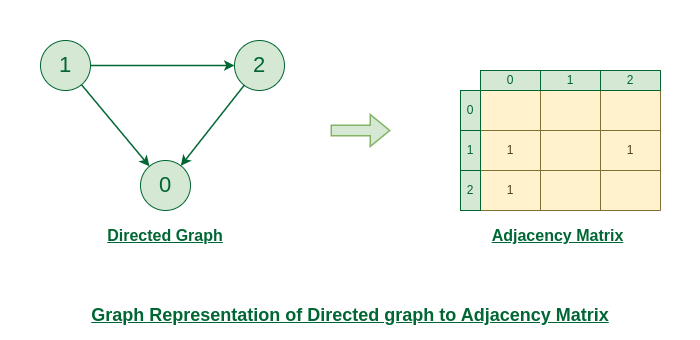

The arrows represent the flow of money from each of these four categories to the others.

In the diagram the horizontal arrows represent such mere banking operations, not true circulation.

On the other hand, the arrows along the sides of the triangle represent actual circulation.

Related Words

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of represent

(Entry 1 of 2)

transitive verb

intransitive verb

Definition of re-present (Entry 2 of 2)

- characterize

Examples of represent in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'represent.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Middle English, from Anglo-French representer , from Latin repraesentare , from re- + praesentare to present

14th century, in the meaning defined at transitive sense 1

1564, in the meaning defined above

Dictionary Entries Near represent

reprehensory

Cite this Entry

“Represent.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/represent. Accessed 27 Apr. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of represent, legal definition, legal definition of represent, more from merriam-webster on represent.

Nglish: Translation of represent for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of represent for Arabic Speakers

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

More commonly misspelled words, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, how to use accents and diacritical marks, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - apr. 26, 9 superb owl words, 'gaslighting,' 'woke,' 'democracy,' and other top lookups, 10 words for lesser-known games and sports, your favorite band is in the dictionary, games & quizzes.

Words and phrases

Personal account.

- Access or purchase personal subscriptions

- Get our newsletter

- Save searches

- Set display preferences

Institutional access

Sign in with library card

Sign in with username / password

Recommend to your librarian

Institutional account management

Sign in as administrator on Oxford Academic

representation noun 1

- Hide all quotations

What does the noun representation mean?

There are 19 meanings listed in OED's entry for the noun representation , three of which are labelled obsolete. See ‘Meaning & use’ for definitions, usage, and quotation evidence.

representation has developed meanings and uses in subjects including

How common is the noun representation ?

How is the noun representation pronounced, british english, u.s. english, where does the noun representation come from.

Earliest known use

Middle English

The earliest known use of the noun representation is in the Middle English period (1150—1500).

OED's earliest evidence for representation is from around 1450, in St. Elizabeth of Spalbeck .

representation is of multiple origins. Either (i) a borrowing from French. Or (ii) a borrowing from Latin.

Etymons: French representation ; Latin repraesentātiōn- , repraesentātiō .

Nearby entries

- reprehensory, adj. 1576–1825

- repremiation, n. 1611

- represent, n. a1500–1635

- represent, v.¹ c1390–

- re-present, v.² 1564–

- representable, adj. & n. 1630–

- representamen, n. 1677–

- representance, n. 1565–

- representant, n. 1622–

- representant, adj. 1851–82

- representation, n.¹ c1450–

- re-presentation, n.² 1805–

- representational, adj. 1850–

- representationalism, n. 1846–

- representationalist, adj. & n. 1846–

- representationary, adj. 1856–

- representationism, n. 1842–

- representationist, n. & adj. 1842–

- representation theory, n. 1928–

- representative, adj. & n. a1475–

- representative fraction, n. 1860–

Thank you for visiting Oxford English Dictionary

To continue reading, please sign in below or purchase a subscription. After purchasing, please sign in below to access the content.

Meaning & use

Pronunciation, compounds & derived words, entry history for representation, n.¹.

representation, n.¹ was revised in December 2009.

representation, n.¹ was last modified in March 2024.

oed.com is a living text, updated every three months. Modifications may include:

- further revisions to definitions, pronunciation, etymology, headwords, variant spellings, quotations, and dates;

- new senses, phrases, and quotations.

Revisions and additions of this kind were last incorporated into representation, n.¹ in March 2024.

Earlier versions of this entry were published in:

OED First Edition (1906)

- Find out more

OED Second Edition (1989)

- View representation in OED Second Edition

Please submit your feedback for representation, n.¹

Please include your email address if you are happy to be contacted about your feedback. OUP will not use this email address for any other purpose.

Citation details

Factsheet for representation, n.¹, browse entry.

Definition of 'representation'

- representation

Video: pronunciation of representation

representation in American English

Representation in british english, examples of 'representation' in a sentence representation, related word partners representation, trends of representation.

View usage over: Since Exist Last 10 years Last 50 years Last 100 years Last 300 years

In other languages representation

- American English : representation / rɛprɪzɛnˈteɪʃən /

- Brazilian Portuguese : representação

- Chinese : 代表

- European Spanish : representación

- French : représentation

- German : Vertretung

- Italian : rappresentanza

- Japanese : 代表

- Korean : 대표

- European Portuguese : representação

- Spanish : representación

- Thai : การมีตัวแทน

Browse alphabetically representation

- represent value

- representamen

- representant

- representation of reality

- representational

- representational painting

- All ENGLISH words that begin with 'R'

Related terms of representation

- ensure representation

- equal representation

- exact representation

- fair representation

- false representation

- View more related words

Quick word challenge

Quiz Review

Score: 0 / 5

Wordle Helper

Scrabble Tools

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Political Representation

The concept of political representation is misleadingly simple: everyone seems to know what it is, yet few can agree on any particular definition. In fact, there is an extensive literature that offers many different definitions of this elusive concept. [Classic treatments of the concept of political representations within this literature include Pennock and Chapman 1968; Pitkin, 1967 and Schwartz, 1988.] Hanna Pitkin (1967) provides, perhaps, one of the most straightforward definitions: to represent is simply to “make present again.” On this definition, political representation is the activity of making citizens’ voices, opinions, and perspectives “present” in public policy making processes. Political representation occurs when political actors speak, advocate, symbolize, and act on the behalf of others in the political arena. In short, political representation is a kind of political assistance. This seemingly straightforward definition, however, is not adequate as it stands. For it leaves the concept of political representation underspecified. Indeed, as we will see, the concept of political representation has multiple and competing dimensions: our common understanding of political representation is one that contains different, and conflicting, conceptions of how political representatives should represent and so holds representatives to standards that are mutually incompatible. In leaving these dimensions underspecified, this definition fails to capture this paradoxical character of the concept.

This encyclopedia entry has three main goals. The first is to provide a general overview of the meaning of political representation, identifying the key components of this concept. The second is to highlight several important advances that have been made by the contemporary literature on political representation. These advances point to new forms of political representation, ones that are not limited to the relationship between formal representatives and their constituents. The third goal is to reveal several persistent problems with theories of political representation and thereby to propose some future areas of research.

1.1 Delegate vs. Trustee

1.2 pitkin’s four views of representation, 2. changing political realities and changing concepts of political representation, 3. contemporary advances, 4. future areas of study, a. general discussions of representation, b. arguments against representation, c. non-electoral forms of representation, d. representation and electoral design, e. representation and accountability, f. descriptive representation, other internet resources, related entries, 1. key components of political representation.

Political representation, on almost any account, will exhibit the following five components:

- some party that is representing (the representative, an organization, movement, state agency, etc.);

- some party that is being represented (the constituents, the clients, etc.);

- something that is being represented (opinions, perspectives, interests, discourses, etc.); and

- a setting within which the activity of representation is taking place (the political context).

- something that is being left out (the opinions, interests, and perspectives not voiced).

Theories of political representation often begin by specifying the terms for the first four components. For instance, democratic theorists often limit the types of representatives being discussed to formal representatives — that is, to representatives who hold elected offices. One reason that the concept of representation remains elusive is that theories of representation often apply only to particular kinds of political actors within a particular context. How individuals represent an electoral district is treated as distinct from how social movements, judicial bodies, or informal organizations represent. Consequently, it is unclear how different forms of representation relate to each other. Andrew Rehfeld (2006) has offered a general theory of representation which simply identifies representation by reference to a relevant audience accepting a person as its representative. One consequence of Rehfeld’s general approach to representation is that it allows for undemocratic cases of representation.

However, Rehfeld’s general theory of representation does not specify what representative do or should do in order to be recognized as a representative. And what exactly representatives do has been a hotly contested issue. In particular, a controversy has raged over whether representatives should act as delegates or trustees .

Historically, the theoretical literature on political representation has focused on whether representatives should act as delegates or as trustees . Representatives who are delegates simply follow the expressed preferences of their constituents. James Madison (1787–8) describes representative government as “the delegation of the government...to a small number of citizens elected by the rest.” Madison recognized that “Enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm.” Consequently, Madison suggests having a diverse and large population as a way to decrease the problems with bad representation. In other words, the preferences of the represented can partially safeguard against the problems of faction.

In contrast, trustees are representatives who follow their own understanding of the best action to pursue. Edmund Burke (1790) is famous for arguing that

Parliament is not a congress of ambassadors from different and hostile interests, which interest each must maintain, as an agent and advocate, against other agents and advocates; but Parliament is a deliberative assembly of one nation, with one interest, that of the whole… You choose a member, indeed; but when you have chosen him he is not a member of Bristol, but he is a member of Parliament (115).

The delegate and the trustee conception of political representation place competing and contradictory demands on the behavior of representatives. [For a discussion of the similarities and differences between Madison’s and Burke’s conception of representation, see Pitkin 1967, 191–192.] Delegate conceptions of representation require representatives to follow their constituents’ preferences, while trustee conceptions require representatives to follow their own judgment about the proper course of action. Any adequate theory of representation must grapple with these contradictory demands.

Famously, Hanna Pitkin argues that theorists should not try to reconcile the paradoxical nature of the concept of representation. Rather, they should aim to preserve this paradox by recommending that citizens safeguard the autonomy of both the representative and of those being represented. The autonomy of the representative is preserved by allowing them to make decisions based on his or her understanding of the represented’s interests (the trustee conception of representation). The autonomy of those being represented is preserved by having the preferences of the represented influence evaluations of representatives (the delegate conception of representation). Representatives must act in ways that safeguard the capacity of the represented to authorize and to hold their representatives accountable and uphold the capacity of the representative to act independently of the wishes of the represented.

Objective interests are the key for determining whether the autonomy of representative and the autonomy of the represented have been breached. However, Pitkin never adequately specifies how we are to identify constituents’ objective interests. At points, she implies that constituents should have some say in what are their objective interests, but ultimately she merely shifts her focus away from this paradox to the recommendation that representatives should be evaluated on the basis of the reasons they give for disobeying the preferences of their constituents. For Pitkin, assessments about representatives will depend on the issue at hand and the political environment in which a representative acts. To understand the multiple and conflicting standards within the concept of representation is to reveal the futility of holding all representatives to some fixed set of guidelines. In this way, Pitkin concludes that standards for evaluating representatives defy generalizations. Moreover, individuals, especially democratic citizens, are likely to disagree deeply about what representatives should be doing.

Pitkin offers one of the most comprehensive discussions of the concept of political representation, attending to its contradictory character in her The Concept of Representation . This classic discussion of the concept of representation is one of the most influential and oft-cited works in the literature on political representation. (For a discussion of her influence, see Dovi 2016). Adopting a Wittgensteinian approach to language, Pitkin maintains that in order to understand the concept of political representation, one must consider the different ways in which the term is used. Each of these different uses of the term provides a different view of the concept. Pitkin compares the concept of representation to “ a rather complicated, convoluted, three–dimensional structure in the middle of a dark enclosure.” Political theorists provide “flash-bulb photographs of the structure taken from different angles” [1967, 10]. More specifically, political theorists have provided four main views of the concept of representation. Unfortunately, Pitkin never explains how these different views of political representation fit together. At times, she implies that the concept of representation is unified. At other times, she emphasizes the conflicts between these different views, e.g. how descriptive representation is opposed to accountability. Drawing on her flash-bulb metaphor, Pitkin argues that one must know the context in which the concept of representation is placed in order to determine its meaning. For Pitkin, the contemporary usage of the term “representation” can signficantly change its meaning.

For Pitkin, disagreements about representation can be partially reconciled by clarifying which view of representation is being invoked. Pitkin identifies at least four different views of representation: formalistic representation, descriptive representation, symbolic representation, and substantive representation. (For a brief description of each of these views, see chart below.) Each view provides a different approach for examining representation. The different views of representation can also provide different standards for assessing representatives. So disagreements about what representatives ought to be doing are aggravated by the fact that people adopt the wrong view of representation or misapply the standards of representation. Pitkin has in many ways set the terms of contemporary discussions about representation by providing this schematic overview of the concept of political representation.

1. Formalistic Representation : Brief Description . The institutional arrangements that precede and initiate representation. Formal representation has two dimensions: authorization and accountability. Main Research Question . What is the institutional position of a representative? Implicit Standards for Evaluating Representatives . None. ( Authorization ): Brief Description . The means by which a representative obtains his or her standing, status, position or office. Main Research Questions . What is the process by which a representative gains power (e.g., elections) and what are the ways in which a representative can enforce his or her decisions? Implicit Standards for Evaluating Representatives . No standards for assessing how well a representative behaves. One can merely assess whether a representative legitimately holds his or her position. pdf include--> ( Accountability ): Brief Description . The ability of constituents to punish their representative for failing to act in accordance with their wishes (e.g. voting an elected official out of office) or the responsiveness of the representative to the constituents. Main Research Question . What are the sanctioning mechanisms available to constituents? Is the representative responsive towards his or her constituents’ preferences? Implicit Standards for Evaluating Representatives . No standards for assessing how well a representative behaves. One can merely determine whether a representative can be sanctioned or has been responsive.

Brief Description . The ways that a representative “stands for” the represented — that is, the meaning that a representative has for those being represented.

Main Research Question . What kind of response is invoked by the representative in those being represented?

Implicit Standards for Evaluating Representatives . Representatives are assessed by the degree of acceptance that the representative has among the represented.

Brief Description . The extent to which a representative resembles those being represented.

Main Research Question . Does the representative look like, have common interests with, or share certain experiences with the represented?

Implicit Standards for Evaluating Representatives . Assess the representative by the accuracy of the resemblance between the representative and the represented.

Brief Description . The activity of representatives—that is, the actions taken on behalf of, in the interest of, as an agent of, and as a substitute for the represented.

Main Research Question . Does the representative advance the policy preferences that serve the interests of the represented?

Implicit Standards for Evaluating Representatives . Assess a representative by the extent to which policy outcomes advanced by a representative serve “the best interests” of their constituents.

One cannot overestimate the extent to which Pitkin has shaped contemporary understandings of political representation, especially among political scientists. For example, her claim that descriptive representation opposes accountability is often the starting point for contemporary discussions about whether marginalized groups need representatives from their groups.

Similarly, Pitkin’s conclusions about the paradoxical nature of political representation support the tendency among contemporary theorists and political scientists to focus on formal procedures of authorization and accountability (formalistic representation). In particular, there has been a lot of theoretical attention paid to the proper design of representative institutions (e.g. Amy 1996; Barber, 2001; Christiano 1996; Guinier 1994). This focus is certainly understandable, since one way to resolve the disputes about what representatives should be doing is to “let the people decide.” In other words, establishing fair procedures for reconciling conflicts provides democratic citizens one way to settle conflicts about the proper behavior of representatives. In this way, theoretical discussions of political representation tend to depict political representation as primarily a principal-agent relationship. The emphasis on elections also explains why discussions about the concept of political representation frequently collapse into discussions of democracy. Political representation is understood as a way of 1) establishing the legitimacy of democratic institutions and 2) creating institutional incentives for governments to be responsive to citizens.

David Plotke (1997) has noted that this emphasis on mechanisms of authorization and accountability was especially useful in the context of the Cold War. For this understanding of political representation (specifically, its demarcation from participatory democracy) was useful for distinguishing Western democracies from Communist countries. Those political systems that held competitive elections were considered to be democratic (Schumpeter 1976). Plotke questions whether such a distinction continues to be useful. Plotke recommends that we broaden the scope of our understanding of political representation to encompass interest representation and thereby return to debating what is the proper activity of representatives. Plotke’s insight into why traditional understandings of political representation resonated prior to the end of the Cold War suggests that modern understandings of political representation are to some extent contingent on political realities. For this reason, those who attempt to define political representation should recognize how changing political realities can affect contemporary understandings of political representation. Again, following Pitkin, ideas about political representation appear contingent on existing political practices of representation. Our understandings of representation are inextricably shaped by the manner in which people are currently being represented. For an informative discussion of the history of representation, see Monica Brito Vieira and David Runican’s Representation .

As mentioned earlier, theoretical discussions of political representation have focused mainly on the formal procedures of authorization and accountability within nation states, that is, on what Pitkin called formalistic representation. However, such a focus is no longer satisfactory due to international and domestic political transformations. [For an extensive discussion of international and domestic transformations, see Mark Warren and Dario Castioglione (2004).] Increasingly international, transnational and non-governmental actors play an important role in advancing public policies on behalf of democratic citizens—that is, acting as representatives for those citizens. Such actors “speak for,” “act for” and can even “stand for” individuals within a nation-state. It is no longer desirable to limit one’s understanding of political representation to elected officials within the nation-state. After all, increasingly state “contract out” important responsibilities to non-state actors, e.g. environmental regulation. As a result, elected officials do not necessarily possess “the capacity to act,” the capacity that Pitkin uses to identify who is a representative. So, as the powers of nation-state have been disseminated to international and transnational actors, elected representatives are not necessarily the agents who determine how policies are implemented. Given these changes, the traditional focus of political representation, that is, on elections within nation-states, is insufficient for understanding how public policies are being made and implemented. The complexity of modern representative processes and the multiple locations of political power suggest that contemporary notions of accountability are inadequate. Grant and Keohane (2005) have recently updated notions of accountability, suggesting that the scope of political representation needs to be expanded in order to reflect contemporary realities in the international arena. Michael Saward (2009) has proposed an innovative type of criteria that should be used for evaluating non-elective representative claims. John Dryzek and Simon Niemayer (2008) has proposed an alternative conception of representation, what he calls discursive representation, to reflect the fact that transnational actors represent discourses, not real people. By discourses, they mean “a set of categories and concepts embodying specific assumptions, judgments, contentions, dispositions, and capabilities.” The concept of discursive representation can potentially redeem the promise of deliberative democracy when the deliberative participation of all affected by a collective decision is infeasible.

Domestic transformations also reveal the need to update contemporary understandings of political representation. Associational life — social movements, interest groups, and civic associations—is increasingly recognized as important for the survival of representative democracies. The extent to which interest groups write public policies or play a central role in implementing and regulating policies is the extent to which the division between formal and informal representation has been blurred. The fluid relationship between the career paths of formal and informal representatives also suggests that contemporary realities do not justify focusing mainly on formal representatives. Mark Warren’s concept of citizen representatives (2008) opens up a theoretical framework for exploring how citizens represent themselves and serve in representative capacities.

Given these changes, it is necessary to revisit our conceptual understanding of political representation, specifically of democratic representation. For as Jane Mansbridge has recently noted, normative understandings of representation have not kept up with recent empirical research and contemporary democratic practices. In her important article “Rethinking Representation” Mansbridge identifies four forms of representation in modern democracies: promissory, anticipatory, gyroscopic and surrogacy. Promissory representation is a form of representation in which representatives are to be evaluated by the promises they make to constituents during campaigns. Promissory representation strongly resembles Pitkin’s discussion of formalistic representation. For both are primarily concerned with the ways that constituents give their consent to the authority of a representative. Drawing on recent empirical work, Mansbridge argues for the existence of three additional forms of representation. In anticipatory representation, representatives focus on what they think their constituents will reward in the next election and not on what they promised during the campaign of the previous election. Thus, anticipatory representation challenges those who understand accountability as primarily a retrospective activity. In gyroscopic representation, representatives “look within” to derive from their own experience conceptions of interest and principles to serve as a basis for their action. Finally, surrogate representation occurs when a legislator represents constituents outside of their districts. For Mansbridge, each of these different forms of representation generates a different normative criterion by which representatives should be assessed. All four forms of representation, then, are ways that democratic citizens can be legitimately represented within a democratic regime. Yet none of the latter three forms representation operates through the formal mechanisms of authorization and accountability. Recently, Mansbridge (2009) has gone further by suggesting that political science has focused too much on the sanctions model of accountability and that another model, what she calls the selection model, can be more effective at soliciting the desired behavior from representatives. According to Mansbridge, a sanction model of accountability presumes that the representative has different interests from the represented and that the represented should not only monitor but reward the good representative and punish the bad. In contrast, the selection model of accountability presumes that representatives have self-motivated and exogenous reasons for carrying out the represented’s wishes. In this way, Mansbridge broadens our understanding of accountability to allow for good representation to occur outside of formal sanctioning mechanisms.

Mansbridge’s rethinking of the meaning of representation holds an important insight for contemporary discussions of democratic representation. By specifying the different forms of representation within a democratic polity, Mansbridge teaches us that we should refer to the multiple forms of democratic representation. Democratic representation should not be conceived as a monolithic concept. Moreover, what is abundantly clear is that democratic representation should no longer be treated as consisting simply in a relationship between elected officials and constituents within her voting district. Political representation should no longer be understood as a simple principal-agent relationship. Andrew Rehfeld has gone farther, maintaining that political representation should no longer be territorially based. In other words, Rehfeld (2005) argues that constituencies, e.g. electoral districts, should not be constructed based on where citizens live.

Lisa Disch (2011) also complicates our understanding of democratic representation as a principal-agent relationship by uncovering a dilemma that arises between expectations of democratic responsiveness to constituents and recent empirical findings regarding the context dependency of individual constituents’ preferences. In response to this dilemma, Disch proposes a mobilization conception of political representation and develops a systemic understanding of reflexivity as the measure of its legitimacy.

By far, one of the most important shifts in the literature on representation has been the “constructivist turn.” Constructivist approaches to representation emphasize the representative’s role in creating and framing the identities and claims of the represented. Here Michael Saward’s The Representative Claim is exemplary. For Saward, representation entails a series of relationships: “A maker of representations (M) puts forward a subject (S) which stands for an object (O) which is related to a referent (R) and is offered to an audience (A)” (2006, 302). Instead of presuming a pre-existing set of interests of the represented that representatives “bring into” the political arena, Saward stresses how representative claim-making is a “deeply culturally inflected practice.” Saward explicitly denies that theorists can know what are the interests of the represented. For this reason, the represented should have the ultimate say in judging the claims of the representative. The task of the representative is to create claims that will resonate with appropriate audiences.

Saward therefore does not evaluate representatives by the extent to which they advance the preferences or interests of the represented. Instead he focuses on the institutional and collective conditions in which claim-making takes place. The constructivist turn examines the conditions for claim-making, not the activities of particular representatives.

Saward’s “constructivist turn” has generated a new research direction for both political theorists and empirical scientists. For example, Lisa Disch (2015) considers whether the constructivist turn is a “normative dead” end, that is, whether the epistemological commitments of constructivism that deny the ability to identify interests will undermine the normative commitments to democratic politics. Disch offers an alternative approach, what she calls “the citizen standpoint”. This standpoint does not mean taking at face value whomever or whatever citizens regard as representing them. Rather, it is “an epistemological and political achievement that does not exist spontaneously but develops out of the activism of political movements together with the critical theories and transformative empirical research to which they give rise” (2015, 493). (For other critical engagements with Saward’s work, see Schaap et al, 2012 and Nässtrom, 2011).

There have been a number of important advances in theorizing the concept of political representation. In particular, these advances call into question the traditional way of thinking of political representation as a principal-agent relationship. Most notably, Melissa Williams’ recent work has recommended reenvisioning the activity of representation in light of the experiences of historically disadvantaged groups. In particular, she recommends understanding representation as “mediation.” In particular, Williams (1998, 8) identifies three different dimensions of political life that representatives must “mediate:” the dynamics of legislative decision-making, the nature of legislator-constituent relations, and the basis for aggregating citizens into representable constituencies. She explains each aspect by using a corresponding theme (voice, trust, and memory) and by drawing on the experiences of marginalized groups in the United States. For example, drawing on the experiences of American women trying to gain equal citizenship, Williams argues that historically disadvantaged groups need a “voice” in legislative decision-making. The “heavily deliberative” quality of legislative institutions requires the presence of individuals who have direct access to historically excluded perspectives.

In addition, Williams explains how representatives need to mediate the representative-constituent relationship in order to build “trust.” For Williams, trust is the cornerstone for democratic accountability. Relying on the experiences of African-Americans, Williams shows the consistent patterns of betrayal of African-Americans by privileged white citizens that give them good reason for distrusting white representatives and the institutions themselves. For Williams, relationships of distrust can be “at least partially mended if the disadvantaged group is represented by its own members”(1998, 14). Finally, representation involves mediating how groups are defined. The boundaries of groups according to Williams are partially established by past experiences — what Williams calls “memory.” Having certain shared patterns of marginalization justifies certain institutional mechanisms to guarantee presence.

Williams offers her understanding of representation as mediation as a supplement to what she regards as the traditional conception of liberal representation. Williams identifies two strands in liberal representation. The first strand she describes as the “ideal of fair representation as an outcome of free and open elections in which every citizen has an equally weighted vote” (1998, 57). The second strand is interest-group pluralism, which Williams describes as the “theory of the organization of shared social interests with the purpose of securing the equitable representation … of those groups in public policies” ( ibid .). Together, the two strands provide a coherent approach for achieving fair representation, but the traditional conception of liberal representation as made up of simply these two strands is inadequate. In particular, Williams criticizes the traditional conception of liberal representation for failing to take into account the injustices experienced by marginalized groups in the United States. Thus, Williams expands accounts of political representation beyond the question of institutional design and thus, in effect, challenges those who understand representation as simply a matter of formal procedures of authorization and accountability.

Another way of reenvisioning representation was offered by Nadia Urbinati (2000, 2002). Urbinati argues for understanding representation as advocacy. For Urbinati, the point of representation should not be the aggregation of interests, but the preservation of disagreements necessary for preserving liberty. Urbinati identifies two main features of advocacy: 1) the representative’s passionate link to the electors’ cause and 2) the representative’s relative autonomy of judgment. Urbinati emphasizes the importance of the former for motivating representatives to deliberate with each other and their constituents. For Urbinati the benefit of conceptualizing representation as advocacy is that it improves our understanding of deliberative democracy. In particular, it avoids a common mistake made by many contemporary deliberative democrats: focusing on the formal procedures of deliberation at the expense of examining the sources of inequality within civil society, e.g. the family. One benefit of Urbinati’s understanding of representation is its emphasis on the importance of opinion and consent formation. In particular, her agonistic conception of representation highlights the importance of disagreements and rhetoric to the procedures, practices, and ethos of democracy. Her account expands the scope of theoretical discussions of representation away from formal procedures of authorization to the deliberative and expressive dimensions of representative institutions. In this way, her agonistic understanding of representation provides a theoretical tool to those who wish to explain how non-state actors “represent.”

Other conceptual advancements have helped clarify the meaning of particular aspects of representation. For instance, Andrew Rehfeld (2009) has argued that we need to disaggregate the delegate/trustee distinction. Rehfeld highlights how representatives can be delegates and trustees in at least three different ways. For this reason, we should replace the traditional delegate/trustee distinction with three distinctions (aims, source of judgment, and responsiveness). By collapsing these three different ways of being delegates and trustees, political theorists and political scientists overlook the ways in which representatives are often partial delegates and partial trustees.

Other political theorists have asked us to rethink central aspects of our understanding of democratic representation. In Inclusion and Democracy Iris Marion Young asks us to rethink the importance of descriptive representation. Young stresses that attempts to include more voices in the political arena can suppress other voices. She illustrates this point using the example of a Latino representative who might inadvertently represent straight Latinos at the expense of gay and lesbian Latinos (1986, 350). For Young, the suppression of differences is a problem for all representation (1986, 351). Representatives of large districts or of small communities must negotiate the difficulty of one person representing many. Because such a difficulty is constitutive of representation, it is unreasonable to assume that representation should be characterized by a “relationship of identity.” The legitimacy of a representative is not primarily a function of his or her similarities to the represented. For Young, the representative should not be treated as a substitute for the represented. Consequently, Young recommends reconceptualizing representation as a differentiated relationship (2000, 125–127; 1986, 357). There are two main benefits of Young’s understanding of representation. First, her understanding of representation encourages us to recognize the diversity of those being represented. Second, her analysis of representation emphasizes the importance of recognizing how representative institutions include as well as they exclude. Democratic citizens need to remain vigilant about the ways in which providing representation for some groups comes at the expense of excluding others. Building on Young’s insight, Suzanne Dovi (2009) has argued that we should not conceptualize representation simply in terms of how we bring marginalized groups into democratic politics; rather, democratic representation can require limiting the influence of overrepresented privileged groups.

Moreover, based on this way of understanding political representation, Young provides an alterative account of democratic representation. Specifically, she envisions democratic representation as a dynamic process, one that moves between moments of authorization and moments of accountability (2000, 129). It is the movement between these moments that makes the process “democratic.” This fluidity allows citizens to authorize their representatives and for traces of that authorization to be evident in what the representatives do and how representatives are held accountable. The appropriateness of any given representative is therefore partially dependent on future behavior as well as on his or her past relationships. For this reason, Young maintains that evaluation of this process must be continuously “deferred.” We must assess representation dynamically, that is, assess the whole ongoing processes of authorization and accountability of representatives. Young’s discussion of the dynamic of representation emphasizes the ways in which evaluations of representatives are incomplete, needing to incorporate the extent to which democratic citizens need to suspend their evaluations of representatives and the extent to which representatives can face unanticipated issues.

Another insight about democratic representation that comes from the literature on descriptive representation is the importance of contingencies. Here the work of Jane Mansbridge on descriptive representation has been particularly influential. Mansbridge recommends that we evaluate descriptive representatives by contexts and certain functions. More specifically, Mansbridge (1999, 628) focuses on four functions and their related contexts in which disadvantaged groups would want to be represented by someone who belongs to their group. Those four functions are “(1) adequate communication in contexts of mistrust, (2) innovative thinking in contexts of uncrystallized, not fully articulated, interests, … (3) creating a social meaning of ‘ability to rule’ for members of a group in historical contexts where the ability has been seriously questioned and (4) increasing the polity’s de facto legitimacy in contexts of past discrimination.” For Mansbridge, descriptive representatives are needed when marginalized groups distrust members of relatively more privileged groups and when marginalized groups possess political preferences that have not been fully formed. The need for descriptive representation is contingent on certain functions.

Mansbridge’s insight about the contingency of descriptive representation suggests that at some point descriptive representatives might not be necessary. However, she doesn’t specify how we are to know if interests have become crystallized or trust has formed to the point that the need for descriptive representation would be obsolete. Thus, Mansbridge’s discussion of descriptive representation suggests that standards for evaluating representatives are fluid and flexible. For an interesting discussion of the problems with unified or fixed standards for evaluating Latino representatives, see Christina Beltran’s The Trouble with Unity .

Mansbridge’s discussion of descriptive representation points to another trend within the literature on political representation — namely, the trend to derive normative accounts of representation from the representative’s function. Russell Hardin (2004) captured this trend most clearly in his position that “if we wish to assess the morality of elected officials, we must understand their function as our representatives and then infer how they can fulfill this function.” For Hardin, only an empirical explanation of the role of a representative is necessary for determining what a representative should be doing. Following Hardin, Suzanne Dovi (2007) identifies three democratic standards for evaluating the performance of representatives: those of fair-mindedness, critical trust building, and good gate-keeping. In Ruling Passions , Andrew Sabl (2002) links the proper behavior of representatives to their particular office. In particular, Sabl focuses on three offices: senator, organizer and activist. He argues that the same standards should not be used to evaluate these different offices. Rather, each office is responsible for promoting democratic constancy, what Sabl understands as “the effective pursuit of interest.” Sabl (2002) and Hardin (2004) exemplify the trend to tie the standards for evaluating political representatives to the activity and office of those representatives.

There are three persistent problems associated with political representation. Each of these problems identifies a future area of investigation. The first problem is the proper institutional design for representative institutions within democratic polities. The theoretical literature on political representation has paid a lot of attention to the institutional design of democracies. More specifically, political theorists have recommended everything from proportional representation (e.g. Guinier, 1994 and Christiano, 1996) to citizen juries (Fishkin, 1995). However, with the growing number of democratic states, we are likely to witness more variation among the different forms of political representation. In particular, it is important to be aware of how non-democratic and hybrid regimes can adopt representative institutions to consolidate their power over their citizens. There is likely to be much debate about the advantages and disadvantages of adopting representative institutions.

This leads to a second future line of inquiry — ways in which democratic citizens can be marginalized by representative institutions. This problem is articulated most clearly by Young’s discussion of the difficulties arising from one person representing many. Young suggests that representative institutions can include the opinions, perspectives and interests of some citizens at the expense of marginalizing the opinions, perspectives and interests of others. Hence, a problem with institutional reforms aimed at increasing the representation of historically disadvantaged groups is that such reforms can and often do decrease the responsiveness of representatives. For instance, the creation of black districts has created safe zones for black elected officials so that they are less accountable to their constituents. Any decrease in accountability is especially worrisome given the ways citizens are vulnerable to their representatives. Thus, one future line of research is examining the ways that representative institutions marginalize the interests, opinions and perspectives of democratic citizens.

In particular, it is necessary for to acknowledge the biases of representative institutions. While E. E. Schattschneider (1960) has long noted the class bias of representative institutions, there is little discussion of how to improve the political representation of the disaffected — that is, the political representation of those citizens who do not have the will, the time, or political resources to participate in politics. The absence of such a discussion is particularly apparent in the literature on descriptive representation, the area that is most concerned with disadvantaged citizens. Anne Phillips (1995) raises the problems with the representation of the poor, e.g. the inability to define class, however, she argues for issues of class to be integrated into a politics of presence. Few theorists have taken up Phillip’s gauntlet and articulated how this integration of class and a politics of presence is to be done. Of course, some have recognized the ways in which interest groups, associations, and individual representatives can betray the least well off (e.g. Strolovitch, 2004). And some (Dovi, 2003) have argued that descriptive representatives need to be selected based on their relationship to citizens who have been unjustly excluded and marginalized by democratic politics. However, it is unclear how to counteract the class bias that pervades domestic and international representative institutions. It is necessary to specify the conditions under which certain groups within a democratic polity require enhanced representation. Recent empirical literature has suggested that the benefits of having descriptive representatives is by no means straightforward (Gay, 2002).

A third and final area of research involves the relationship between representation and democracy. Historically, representation was considered to be in opposition with democracy [See Dahl (1989) for a historical overview of the concept of representation]. When compared to the direct forms of democracy found in the ancient city-states, notably Athens, representative institutions appear to be poor substitutes for the ways that citizens actively ruled themselves. Barber (1984) has famously argued that representative institutions were opposed to strong democracy. In contrast, almost everyone now agrees that democratic political institutions are representative ones.

Bernard Manin (1997)reminds us that the Athenian Assembly, which often exemplifies direct forms of democracy, had only limited powers. According to Manin, the practice of selecting magistrates by lottery is what separates representative democracies from so-called direct democracies. Consequently, Manin argues that the methods of selecting public officials are crucial to understanding what makes representative governments democratic. He identifies four principles distinctive of representative government: 1) Those who govern are appointed by election at regular intervals; 2) The decision-making of those who govern retains a degree of independence from the wishes of the electorate; 3) Those who are governed may give expression to their opinions and political wishes without these being subject to the control of those who govern; and 4) Public decisions undergo the trial of debate (6). For Manin, historical democratic practices hold important lessons for determining whether representative institutions are democratic.

While it is clear that representative institutions are vital institutional components of democratic institutions, much more needs to be said about the meaning of democratic representation. In particular, it is important not to presume that all acts of representation are equally democratic. After all, not all acts of representation within a representative democracy are necessarily instances of democratic representation. Henry Richardson (2002) has explored the undemocratic ways that members of the bureaucracy can represent citizens. [For a more detailed discussion of non-democratic forms of representation, see Apter (1968). Michael Saward (2008) also discusses how existing systems of political representation do not necessarily serve democracy.] Similarly, it is unclear whether a representative who actively seeks to dismantle democratic institutions is representing democratically. Does democratic representation require representatives to advance the preferences of democratic citizens or does it require a commitment to democratic institutions? At this point, answers to such questions are unclear. What is certain is that democratic citizens are likely to disagree about what constitutes democratic representation.

One popular approach to addressing the different and conflicting standards used to evaluate representatives within democratic polities, is to simply equate multiple standards with democratic ones. More specifically, it is argued that democratic standards are pluralistic, accommodating the different standards possessed and used by democratic citizens. Theorists who adopt this approach fail to specify the proper relationship among these standards. For instance, it is unclear how the standards that Mansbridge identifies in the four different forms of representation should relate to each other. Does it matter if promissory forms of representation are replaced by surrogate forms of representation? A similar omission can be found in Pitkin: although Pitkin specifies there is a unified relationship among the different views of representation, she never describes how the different views interact. This omission reflects the lacunae in the literature about how formalistic representation relates to descriptive and substantive representation. Without such a specification, it is not apparent how citizens can determine if they have adequate powers of authorization and accountability.

Currently, it is not clear exactly what makes any given form of representation consistent, let alone consonant, with democratic representation. Is it the synergy among different forms or should we examine descriptive representation in isolation to determine the ways that it can undermine or enhance democratic representation? One tendency is to equate democratic representation simply with the existence of fluid and multiple standards. While it is true that the fact of pluralism provides justification for democratic institutions as Christiano (1996) has argued, it should no longer presumed that all forms of representation are democratic since the actions of representatives can be used to dissolve or weaken democratic institutions. The final research area is to articulate the relationship between different forms of representation and ways that these forms can undermine democratic representation.

- Andeweg, Rudy B., and Jacques J.A. Thomassen, 2005. “Modes of Political Representation: Toward a new typology,” Legislative Studies Quarterly , 30(4): 507–528.

- Ankersmit, Franklin Rudolph, 2002. Political Representation , Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Alcoff, Linda, 1991. “The Problem of Speaking for Others,” Cultural Critique , Winter: 5–32.

- Alonso, Sonia, John Keane, and Wolfgang Merkel (eds.), 2011. The Future of Representative Democracy , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Beitz, Charles, 1989. Political Equality , Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Chapter 6 is on ‘Representation’]

- Burke, Edmund, 1790 [1968]. Reflections on the Revolution in France , London: Penguin Books.

- Dahl, Robert A., 1989. Democracy and Its Critics , New Haven: Yale University.

- Disch, Lisa, 2015. “The Constructivist Turn in Democratic Representation: A Normative Dead-End?,” Constellations , 22(4): 487–499.

- Dovi, Suzanne, 2007. The Good Representative , New York: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing.

- Downs, Anthony, 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy , New York: Harper.

- Dryzek, John and Simon Niemeyer, 2008. “Discursive Representation,” American Political Science Review , 102(4): 481–493.

- Hardin, Russell, 2004. “Representing Ignorance,” Social Philosophy and Policy , 21: 76–99.

- Lublin, David, 1999. The Paradox of Representation: Racial Gerrymandering and Minority Interests in Congress , Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Madison, James, Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, 1787–8 [1987]. The Federalist Papers , Isaac Kramnick (ed.), Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Mansbridge, Jane, 2003. “Rethinking Representation,” American Political Science Review , 97(4): 515–28.

- Manin, Bernard, 1997. The Principles of Representative Government , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nässtrom, Sofia, 2011. “Where is the representative turn going?” European journal of political theory, , 10(4): 501–510.

- Pennock, J. Roland and John Chapman (eds.), 1968. Representation , New York: Atherton Press.

- Pitkin, Hanna Fenichel, 1967. The Concept of Representation , Berkeley: University of California.

- Plotke, David, 1997. “Representation is Democracy,” Constellations , 4: 19–34.

- Rehfeld, Andrew, 2005. The Concept of Constituency: Political Representation, Democratic Legitimacy and Institutional Design , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- –––, 2006. “Towards a General Theory of Political Representation,” The Journal of Politics , 68: 1–21.

- Rosenstone, Steven and John Hansen, 1993. Mobilization, Participation, and Democracy in America , New York: MacMillian Publishing Company.

- Runciman, David, 2007. “The Paradox of Political Representation,” Journal of Political Philosophy , 15: 93–114.

- Saward, Michael, 2014. “Shape-shifting representation”. American Political Science Review , 108(4): 723–736.

- –––, 2010. The Representative Claim , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- –––, 2008. “Representation and democracy: revisions and possibilities,” Sociology compass , 2(3): 1000–1013.

- –––, 2006. “The representative claim”. Contemporary political theory , 5(3): 297–318.

- Sabl, Andrew, 2002. Ruling Passions: Political Offices and Democratic Ethics , Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Schaap, Andrew, Thompson, Simon, Disch, Lisa, Castiglione, Dario and Saward, Michael, 2012. “Critical exchange on Michael Saward’s The Representative Claim,” Contemporary Political Theory , 11(1): 109–127.

- Schattschneider, E. E., 1960. The Semisovereign People , New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Schumpeter, Joseph, 1976. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy , London: Allen and Unwin.

- Schwartz, Nancy, 1988. The Blue Guitar: Political Representation and Community , Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Shapiro, Ian, Susan C. Stokes, Elisabeth Jean Wood and Alexander S. Kirshner (eds.), 2009. Political Representation , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Urbinati, Nadia, 2000. “Representation as Advocacy: A Study of Democratic Deliberation,” Political Theory , 28: 258–786.

- Urbinati, Nadia and Mark Warren, 2008. “The Concept of Representation in Contemporary Democratic Theory,” Annual Review of Political Science , 11: 387–412

- Vieira, Monica and David Runciman, 2008. Representation , Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Vieira, Monica (ed.), 2017. Reclaiming Representation: Contemporary Advances in the Theory of Political Representation , New York: Routledge Press.

- Warren, Mark and Dario Castiglione, 2004. “The Transformation of Democratic Representation,” Democracy and Society , 2(1): 5–22.

- Barber, Benjamin, 1984. Strong Democracy , Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

- Dryzek, John, 1996. “Political Inclusion and the Dynamics of Democratization,” American Political Science Review , 90 (September): 475–487.

- Pateman, Carole, 1970. Participation and Democratic Theory , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rousseau, Jean Jacques, 1762, The Social Contract , Judith Masters and Roger Masters (trans.), New York: St. Martins Press, 1978.

- Saward, Michael, 2008. “Representation and Democracy: Revisions and Possibilities,” Sociology Compass , 2: 1000–1013.

- Apter, David, 1968. “Notes for a Theory of Nondemocratic Representation,” in Nomos X , Chapter 19, pp. 278–317.

- Brown, Mark, 2006. “Survey Article: Citizen Panels and the Concept of Representation,” Journal of Political Philosophy , 14: 203–225.

- Cohen, Joshua and Joel Rogers, 1995. Associations and Democracy (The Real Utopias Project: Volume 1), Erik Olin Wright (ed.), London: Verso.

- Dalton, Russell J., and Martin P. Wattenberg (eds.), 2002. Parties without partisans: Political change in advanced industrial democracies , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Montanaro, L., 2012. “The Democratic Legitimacy of Self-appointed Representatives,” The Journal of Politics , 74(4): 1094–1107.

- Ryden, David K., 1996. Representation in Crisis: The Constitution, Interest Groups, and Political Parties , Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Truman, David, 1951. The Governmental Process , New York: Knopf.

- Saward, Michael, 2009. “ Authorisation and Authenticity: Representation and the Unelected,” Journal of Political Philosophy , 17: 1–22.

- Steunenberg, Bernard and J. J. A.Thomassen, 2002. The European Parliament : Moving Toward Democracy in the EU , Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Schmitter, Philippe, 2000. “Representation,” in How to democratize the European Union and Why Bother? , Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, Ch. 3. pp. 53–74.

- Street, John, 2004. “Celebrity politicians: popular culture and political representation,” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations , 6(4): 435–452.

- Strolovitch, Dara Z., 2007. Affirmative Advocacy: Race, Class, and Gender in Interest Group Politics , Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Tormey, S., 2012. “Occupy Wall Street: From representation to post-representation,” Journal of Critical Globalisation Studies , 5: 132–137.

- Richardson, Henry, 2002. “Representative government,” in Democratic Autonomy , Oxford: Oxford University Press, Ch. 14, pp. 193–202

- Runciman, David, 2010. “Hobbes’s Theory of Representation: anti-democratic or protodemoratic,” in Political Representation , Ian Shapiro, Susan C. Stokes, Elisabeth Jean Wood, and Alexander Kirshner (eds.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Warren, Mark, 2001. Democracy and Association , Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- –––, 2008. “Citizen Representatives,” in Designing Deliberative Democracy: The British ColumbiaCitizens’ Assembly , Mark Warren and Hilary Pearse (eds.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 50–69.

- Warren, Mark and Dario Castiglione, 2004. “The Transformation of Democratic Representation,” Democracy and Society , 2(I): 5, 20–22.

- Amy, Douglas, 1996. Real Choices/New Voices: The Case for Proportional Elections in the United States , New York: Columbia University Press.

- Barber, Kathleen, 2001. A Right to Representation: Proportional Election Systems for the 21 st Century , Columbia: Ohio University Press.

- Canon, David, 1999. Race, Redistricting, and Representation: The Unintended Consequences of Black Majority Districts , Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Christiano, Thomas, 1996. The Rule of the Many , Boulder: Westview Press.

- Cotta, Maurizio and Heinrich Best (eds.), 2007. Democratic Representation in Europe Diversity, Change, and Convergence , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Guinier, Lani, 1994. The Tyranny of the Majority: Fundamental Fairness in Representative Democracy , New York: Free Press.

- Przworksi, Adam, Susan C. Stokes, and Bernard Manin (eds.), 1999. Democracy, Accountability, and Representation , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thompson, Dennis, 2002. Just Elections , Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Jacobs, Lawrence R. and Robert Y. Shapiro, 2000. Politicians Don’t Pander: Political Manipulation and the Loss of Democratic Responsiveness , Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Grant, Ruth and Robert O. Keohane, 2005. “Accountability and Abuses of Power in World Politics,” American Political Science Review , 99 (February): 29–44.

- Mansbridge, Jane, 2004. “Representation Revisited: Introduction to the Case Against Electoral Accountability,” Democracy and Society , 2(I): 12–13.

- –––, 2009. “A Selection Model of Representation,” Journal of Political Philosophy , 17(4): 369–398.

- Pettit, Philip, 2010. “Representation, Responsive and Indicative,” Constellations , 17(3): 426–434.

- Fishkin, John, 1995. The Voice of the People: Public Opinion and Democracy , New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Gutmann, Amy and Dennis Thompson, 2004. Why Deliberative Democracy? , Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hibbing, John and Elizabeth Theiss-Morse, 2002. Stealth Democracy , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Saward, Michael (ed.), 2000. Democratic Innovation: Deliberation, Representation and Association , London: Routledge.

- Severs, E., 2010. “Representation As Claims-Making. Quid Responsiveness?” Representation , 46(4): 411–423.

- Williams, Melissa, 2000. “The Uneasy Alliance of Group Representation and Deliberative Democracy,” in Citizenship in Diverse Societies , W. Kymlicka and Wayne Norman (eds.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, Ch 5. pp. 124–153.

- Young, Iris Marion, 1999. “Justice, Inclusion, and Deliberative Democracy” in Deliberative Politics , Stephen Macedo (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University.

- Bentran, Cristina, 2010. The Trouble with Unity: Latino Politics and the Creation of Identity , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Celis, Karen, Sarah Childs, Johanna Kantola and Mona Lena Krook, 2008, “Rethinking Women’s Substantive Representation,” Representation , 44(2): 99–110.

- Childs Sarah, 2008. Women and British Party Politics: Descriptive, Substantive and Symbolic Representation , London: Routledge.

- Dovi, Suzanne, 2002. “Preferable Descriptive Representatives: Or Will Just Any Woman, Black, or Latino Do?,” American Political Science Review , 96: 745–754.

- –––, 2007. “Theorizing Women’s Representation in the United States?,” Politics and Gender , 3(3): 297–319. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X07000281

- –––, 2009. “In Praise of Exclusion,” Journal of Politics , 71 (3): 1172–1186.

- –––, 2016. “Measuring Representation: Rethinking the Role of Exclusion” Political Representation , Marc Bühlmann and Jan Fivaz (eds.), London: Routledge.

- Fenno, Richard F., 2003. Going Home: Black Representatives and Their Constituents , Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Gay, Claudine, 2002. “Spirals of Trust?,” American Journal of Political Science , 4: 717–32.

- Gould, Carol, 1996. “Diversity and Democracy: Representing Differences,” in Democracy and Difference: Contesting the Boundaries of the Political , Seyla Benhabib (ed.), Princeton: Princeton University, pp. 171–186.

- Htun, Mala, 2004. “Is Gender like Ethnicity? The Political Representation of Identity Groups,” Perspectives on Politics , 2: 439–458.

- Mansbridge, Jane, 1999. “Should Blacks Represent Blacks and Women Represent Women? A Contingent ‘Yes’,” The Journal of Politics , 61: 628–57.

- –––, 2003. “Rethinking Representation,” American Political Science Review , 97: 515–528.

- Phillips, Anne, 1995. Politics of Presence , New York: Clarendon.

- –––, 1998. “Democracy and Representation: Or, Why Should It Matter Who Our Representatives Are?,” in Feminism and Politics , Oxford: Oxford University. pp. 224–240.

- Pitkin, Hanna, 1967. The Concept of Representation , Los Angeles: University of Press.

- Sapiro, Virginia, 1981. “When are Interests Interesting?,” American Political Science Review , 75 (September): 701–721.

- Strolovitch, Dara Z., 2004. “Affirmative Representation,” Democracy and Society , 2: 3–5.

- Swain, Carol M., 1993. Black Faces, Black Interests: The Representation of African Americans in Congress , Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

- Thomas, Sue, 1991. “The Impact of Women on State Legislative Policies,” Journal of Politics , 53 (November): 958–976.

- –––, 1994. How Women Legislate , New York: Oxford University Press.

- Weldon, S. Laurel, 2002. “Beyond Bodies: Institutional Sources of Representation for Women in Democratic Policymaking,” Journal of Politics , 64(4): 1153–1174.

- Williams, Melissa, 1998. Voice, Trust, and Memory: Marginalized Groups and the Failings of Liberal Representation , Princeton, NJ: Princeton University.

- Young, Iris Marion, 1986. “Deferring Group Representation,” Nomos: Group Rights , Will Kymlicka and Ian Shapiro (eds.), New York: New York University Press, pp. 349–376.

- –––, 1990. Justice and the Politics of Difference , Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

- –––, 2000. Inclusion and Democracy , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

G. Democratic Representation

- Castiglione, D., 2015. “Trajectories and Transformations of the Democratic Representative System”. Global Policy , 6(S1): 8–16.

- Disch, Lisa, 2011. “Toward a Mobilization Conception of Democratic Representation,” American Political Science Review , 105(1): 100–114.

- –––, 2012. “Democratic representation and the constituency paradox,” Perspectives on Politics , 10(3): 599–616.

- –––, 2016. “Hanna Pitkin, The Concept of Representation,” The Oxford Handbook of Classics in Contemporary Political Theory , Jacob Levy (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198717133.013.24

- Mansbridge, Jane, 2003. “Rethinking Representation,” American Political Science Review , 97: 515–528.

- Näsström, Sofia, 2006. “Representative democracy as tautology: Ankersmit and Lefort on representation,” European Journal of Political Theory , 5(3): 321–342.

- Urbinati, Nadia, 2011. “Political Representation as Democratic Process,” Redescriptions (Yearbook of Political Thought and Conceptual History: Volume 10), Kari Palonen (ed.), Helsinki: Transaction Publishers.

How to cite this entry . Preview the PDF version of this entry at the Friends of the SEP Society . Look up topics and thinkers related to this entry at the Internet Philosophy Ontology Project (InPhO). Enhanced bibliography for this entry at PhilPapers , with links to its database.

- FairVote Program for Representative Government

- Proportional Representation Library , provides readings proportional representation elections created by Prof. Douglas J. Amy, Dept. of Politics, Mount Holyoke College

- Representation , an essay by Ann Marie Baldonado on the Postcolonial Studies website at Emory University.

- Representation: John Locke, Second Treatise, §§ 157–58 , in The Founders’ Constitution at the University of Chicago Press

- Popular Basis of Political Authority: David Hume, Of the Original Contract , in The Founders’ Constitution at the University of Chicago Press

Burke, Edmund | democracy

Copyright © 2018 by Suzanne Dovi < sdovi @ email . arizona . edu >

- Accessibility

Support SEP

Mirror sites.

View this site from another server:

- Info about mirror sites

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is copyright © 2023 by The Metaphysics Research Lab , Department of Philosophy, Stanford University

Library of Congress Catalog Data: ISSN 1095-5054

What is Representational Art? (Explained with Examples)

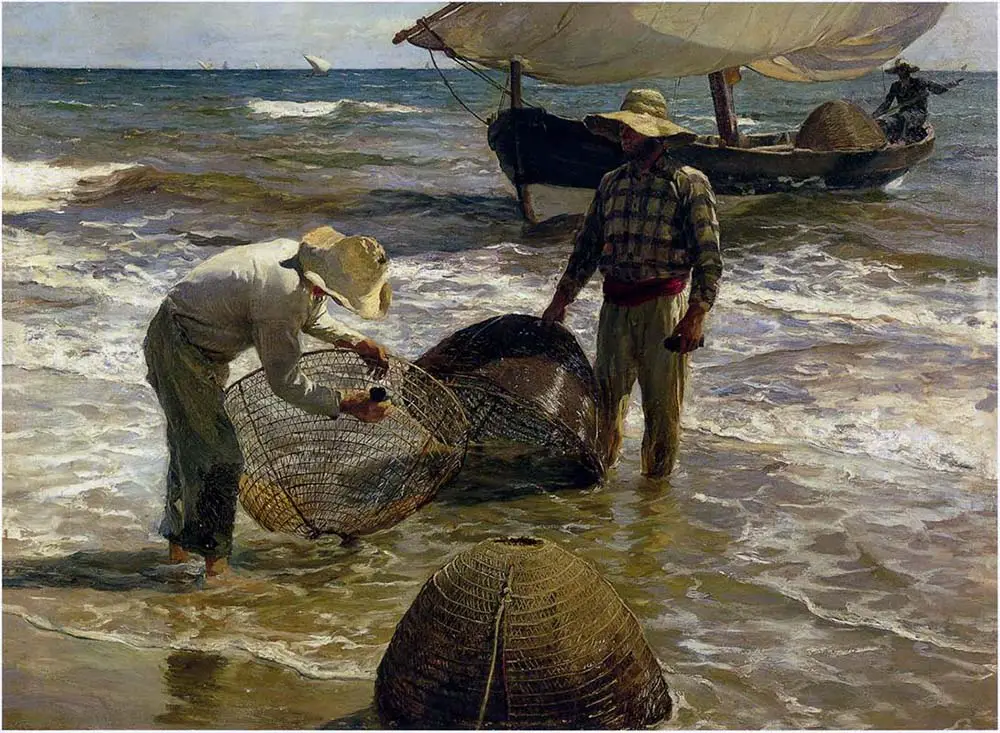

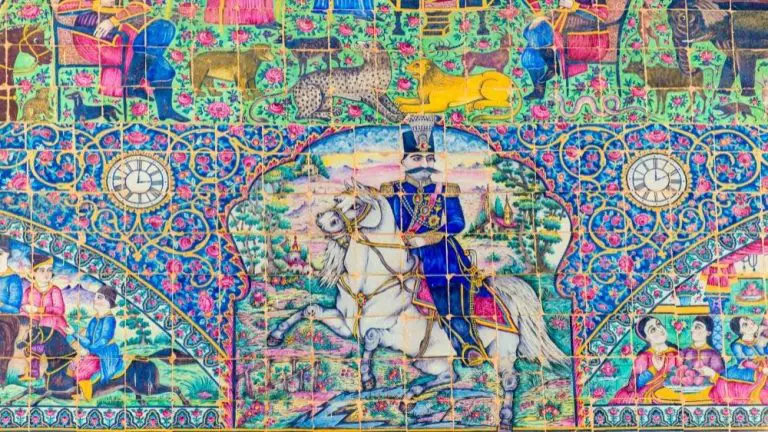

When you look at an artwork, the first thing that crosses your mind is how attractive or unattractive the art is. While some artwork simply expresses aesthetic beauty, other artworks aim to pass a message or represent real situations. The latter type of art is known as representational art.

Representational arts are artworks that depict real situations. The sources of inspiration for a representational work are generally real objects, people, or scenes. For instance, the painting of a cat is considered to be representational art because it describes a real-world subject.

Keep reading to learn more about representational art including its history, its importance in the art world, and some of the styles most well-known artists.

Table of Contents

Definition Of Representational Art

(This article may contain affiliate links and I may earn a commission if you make a purchase)

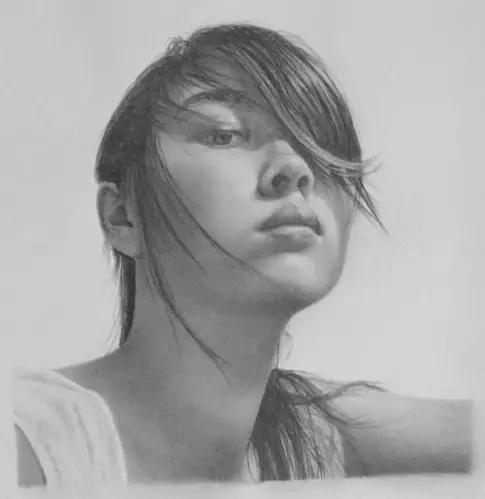

A representational artwork contains a real image or object that individuals can easily identify. Therefore, the artist aims at using a skillful technique to give the visual art an appropriate touch of realism.

Some representational artworks fuse abstract art with reality, but this doesn’t make it less of representational art. In other words, some representational artworks could depict real objects in a realistic way, but that is not required.

For instance, a representational artist can paint a flower using characteristics that anyone can identify as a flower’s, but then the artist adds other abstract elements to its environment. These elements are things you would never find in the environment of a flower which also diminishes the concept of reality.

But, provided that it still has the basic elements related to something real, it is still considered a form of representational art.

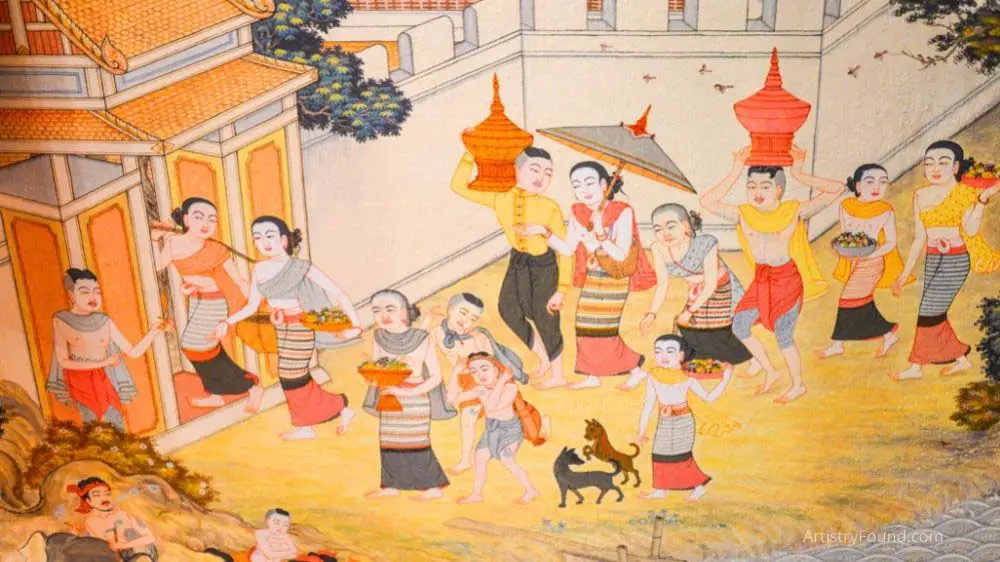

Representational pieces usually contain seascapes, landscapes, portraits, and still-life figures. Aside from these, representational arts represent scenes from everyday life and history.

Note #1 : Sometimes, Representational Art is referred to as Figurative Art even though it doesn’t have to contain figures.

Note #2 : Nonrepresentational art would be artwork that doesn’t portray anything that is real. In other words, the art work doesn’t attempt to illustrate a person, place, or object as in conceptual art. See artist Piet Mondrian’s Kunstmuseum Den Haag as an example.

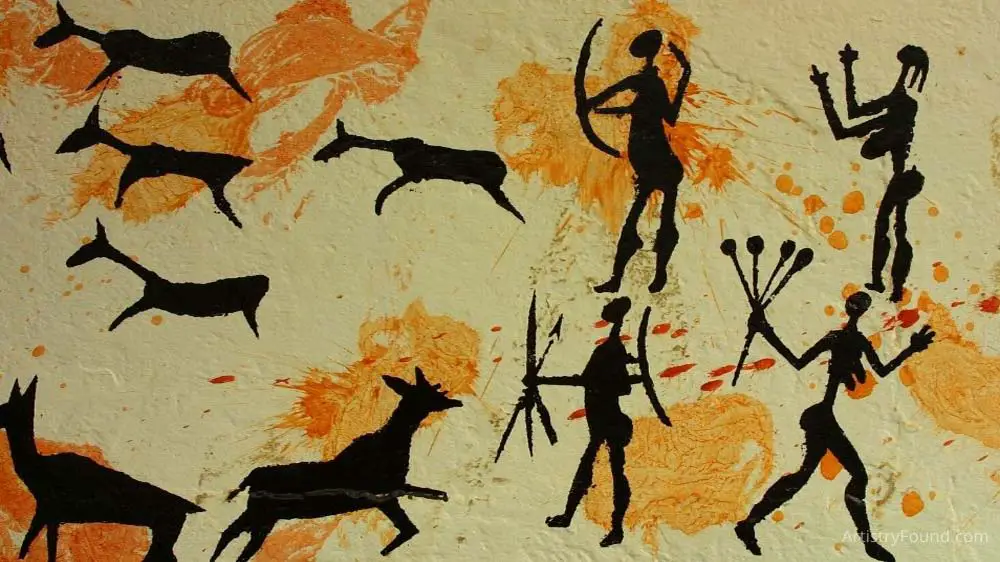

A Brief History Of Representational Art

Representational arts are some of the oldest surviving artworks in the world. These works date back to cave paintings from over 40,000 years ago. Another example is The Venus of Willendorf , which dates back to more than 25,000 years ago.