Dark background

Light background

Text only mode

Critical and Reflective Practice in Education

ISSN 2040-4735 (online)

Critical and Reflective Practice in Education is an open-access, peer reviewed, electronic journal produced by Plymouth Marjon University. The aim of the journal is to provide a forum for the dissemination of work by researchers, practitioners and students in all forms of Education, thereby encouraging critical debate among the Education community as a whole. In particular, the journal aims to be accessible to, and supportive of, those new to research and publication.

Executive editor: Sean MacBlain .

Email [email protected]

The journal welcomes the following kinds of contributions:

- Reflective or commentary papers that provide critical literature reviews, discussions of current topics or future directions, opinions, reflections on practice, or comments to published work.

- Curriculum papers that describe new materials developed for different aspects of education or related work.

- Teaching and learning papers, describing new teaching methods or pedagogies developed for courses or other target populations.

- Empirical research papers, presenting and analysing data to answer a specific research question or test a hypothesis.

- Theoretical research papers, describing new theories and philosophies in education, developed to fill a theoretical or philosophical gap.

Please download the instructions for authors (below) for further guidance. Authors considering writing for the journal are welcome to contact the editors to discuss their ideas.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- CBE Life Sci Educ

- v.22(2); Summer 2023

- PMC10228263

Reflective Practices in Education: A Primer for Practitioners

Haleigh machost.

1 Department of Chemistry, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia 22903

Marilyne Stains

Associated data.

Reflective practices in education are widely advocated for and have become important components of professional reviews. The advantages of reflective practices are many; however, the literature often focuses on the benefits to students, rather than the benefits for the educators themselves. Additionally, the extant literature concerning reflective practices in education is laden with conflicting terminology and complex studies, which can inhibit educators’ understanding of reflective practices and prevent their adoption. As such, this Essay serves as a primer for educators beginning reflective practices. It briefly describes the benefits to educators and different classifications and modalities of reflection and examines some of the challenges that educators may encounter.

INTRODUCTION

“Reflection” has become a buzzword in academia and has vast array of implications across fields, disciplines, and subdisciplines. When considering reflection about teaching practices, John Dewey, a psychologist and philosopher who was heavily influential in educational reform, provides a relevant description: reflection is ‘‘the active, persistent and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it and the further conclusions to which it tends” ( Dewey, 1933 , p. 9). The act of reflection in this context is meant to indicate a process , with Dewey highlighting the necessity of active thinking when encountering obstacles and problems. In less philosophical phrasing, reflection entails considering past or present experiences, learning from the outcomes observed, and planning how to better approach similar situations in the future. Consequently, Dewey suggests that educators embark on a journey of continual improvement when engaging in reflective practices. This is in stark contrast to how reflection is used in higher education. For many educators, the only time they engage in reflection is when they are asked to write documents that are used to evaluate whether they should be promoted, receive a raise, or be granted tenure. Reflection, within an evaluation framework, can be counterproductive and prevent meaningful reflections due to perceptions of judgment ( Brookfield, 2017 ).

This gap may result from the particular adaptation of reflections by some academics. The origin of reflective practices lies not in the realm of academia, but rather in professional training. It is often traced back to Donald Schön’s instrumental 1983 work The Reflective Practitioner , which, while aimed at his target audience of nonacademic professionals, has become foundational for reflective practices in teaching ( Munby and Russell, 1989 ).

In the varied topography of professional practice, there is a high, hard ground where practitioners can make effective use of research-based theory and technique, and there is a swampy lowland where situations are confusing “messes” incapable of technical solution. The difficulty is that the problems of the high ground, however great their technical interest, are often relatively unimportant to clients or to the larger society, while in the swamp are the problems of greatest human concern. ( Schön, 1983 , p. 42)

Schön’s work on the education of various professionals gained traction, as he diverged from common norms of the time. In particular, he disagreed with separating knowledge and research from practice, and methods from results ( Schön, 1983 ; Newman, 1999 ). In doing so, he advocated for practical as well as technical knowledge, enabling professionals to develop greater competency in the real-world situations they encounter. Research in the ensuing decades focused on both gaining evidence for the effectiveness of reflective practices ( Dervent, 2015 ; Zahid and Khanam, 2019 ) and understanding the obstacles that can prevent reflective practices from being adopted ( Davis, 2003 ; Sturtevant and Wheeler, 2019 ).

This Essay is not intended to provide a comprehensive review of this work for use by education researchers; rather, the goal of this Essay is to provide a guide, grounded in this literature, to inform beginning reflective practitioners about the benefits of reflections, the different types of reflections that one can engage in, practical advice for engaging in reflective practices, and the potential challenges and corresponding solutions when engaging in reflective practices. It is also intended as a resource for professional development facilitators who are interested in infusing reflective practice within their professional development programs.

WHY SHOULD I ENGAGE IN REFLECTIVE PRACTICES?

Perhaps the best place to begin when discussing reflective practices is with the question “Why do people do it?” It is common to conceptualize reflection about teaching situations as a way to help “fix” any problems or issues that present themselves ( Brookfield, 2017 ). However, this view is counterproductive to the overarching goal of reflective practices—to continually improve one’s own efficacy and abilities as an educator. Similar to how there is always a new, more efficient invention to be made, there is always room for improvement by even the most experienced and well-loved educators. People choose to be educators for any number of personal reasons, but often the grounding desire is to help inform, mentor, or guide the next generation. With such a far-reaching aim, educators face many obstacles, and reflective practices are one tool to help mitigate them.

Classrooms are an ever-changing environment. The students change, and with that comes new generational experiences and viewpoints. Updates to technology provide new opportunities for engaging with students and exploring their understanding. New curricula and pedagogical standards from professional organizations, institutions, or departments can fundamentally alter the modes of instruction and the concepts and skills being taught. As described by Brookfield, reflection can act as a “gyroscope,” helping educators stay balanced amid a changing environment ( 2017 , p. 81). Through the process of reflection, practitioners focus on what drives them to teach and their guiding principles, which define how they interact with both their students and their peers. Furthermore, reflective practitioners are deliberately cognizant of the reasoning behind their actions, enabling them to act with more confidence when faced with a sudden or difficult situation ( Brookfield, 2017 ). In this way, reflection can help guide educators through the challenging times they may experience in their careers.

One such obstacle is imposter syndrome, which is all too familiar for many educators ( Brems et al. , 1994 ; Parkman, 2016 ; Collins et al. , 2020 ). It is a sense that, despite all efforts put in—the knowledge gained, the relationships formed, and the lives changed—what one does is never enough and one does not belong. These feelings often lead to a fear of being “discovered as a fraud or non-deserving professional, despite their demonstrated talent and achievements” ( Chrousos and Mentis, 2020 , p. 749). A part of reflective practices that is often overlooked is the consideration of everything that goes well . While it is true that reflective practitioners are aware of areas for improvement in their teaching, it is also true that they acknowledge, celebrate, and learn from good things that happen in their classrooms and in their interactions with students and peers. As such, they are more consciously aware of their victories, even if those victories happen to be small ( Brookfield, 2017 ). That is not to say that reflective practices are a cure-all for those dealing with imposter syndrome, but reflections can be a reminder that their efforts are paying off and that someone, whether it be students, peers, or even the practitioner themselves, is benefiting from their actions. Furthermore, reflecting on difficult situations has the potential for individuals to realize the extent of their influence ( Brookfield, 2017 ).

In a similar vein, reflective practices can help educators realize when certain expectations or cultural norms are out of their direct ability to address. For example, educators cannot be expected to tackle systemic issues such as racism, sexism, and ableism alone. Institutions must complement educators’ efforts through, for example, establishment of support systems for students excluded because of their ethnicity or race and the implementation of data-driven systems, which can inform the institutions’ and educators’ practices. Thus, through reflections, educators can avoid “self-laceration” ( Brookfield, 2017 , p. 86) and feelings of failure when the problems experienced are multifaceted.

In addition to alleviating “self-laceration,” developing reflective practice and reflective practitioners has been identified as one of four dominant change strategies in the literature ( Henderson et al. , 2011 ). Specifically, developing reflective practitioners is identified as a strategy that empowers individual educators to enact change ( Henderson et al. , 2011 ). One avenue for such change comes with identifying practices that are harmful to students. Reflecting on teaching experiences and student interactions can allow educators to focus on things such as whether an explanatory metaphor is accessible to different types of students in the class (e.g., domestic and international students), if any particular group of students do not work well together, and whether the curriculum is accessible for students from varied educational and cultural backgrounds. Thus, through the process of reflection, educators grow in their ability to help their students on a course level, and they are better positioned to advocate on their students’ behalf when making curricular decisions on a departmental or institutional level.

An additional part of reflection is gathering feedback to enable a holistic view of one’s teaching practices. When feedback is given by a trusted peer, this invaluable information can guide chosen teaching methods and ways of explaining new information. When feedback is given by students and that feedback is then acted upon, it demonstrates to the students that their opinions and experiences are taken seriously and fosters a more trusting environment ( Brookfield, 2017 ). Furthermore, when discrepancies arise between the intention of the teacher and the interpretation of the students, reflection also aids practitioners in verbalizing their reasoning. Through reflection, educators would need to consider past experiences, prior knowledge, and beliefs that led to their actions. As such, reflective practitioners are able to have honest and informed discussions with their students who may be confused or unhappy with a particular decision. Explaining this to students not only models the practice of continuous inquiry and of considering one’s actions, but it also allows students to understand the rationale behind decisions they may not personally agree with, fostering a more productive student–teacher relationship ( Brookfield, 2017 ).

WHAT ARE THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF REFLECTION?

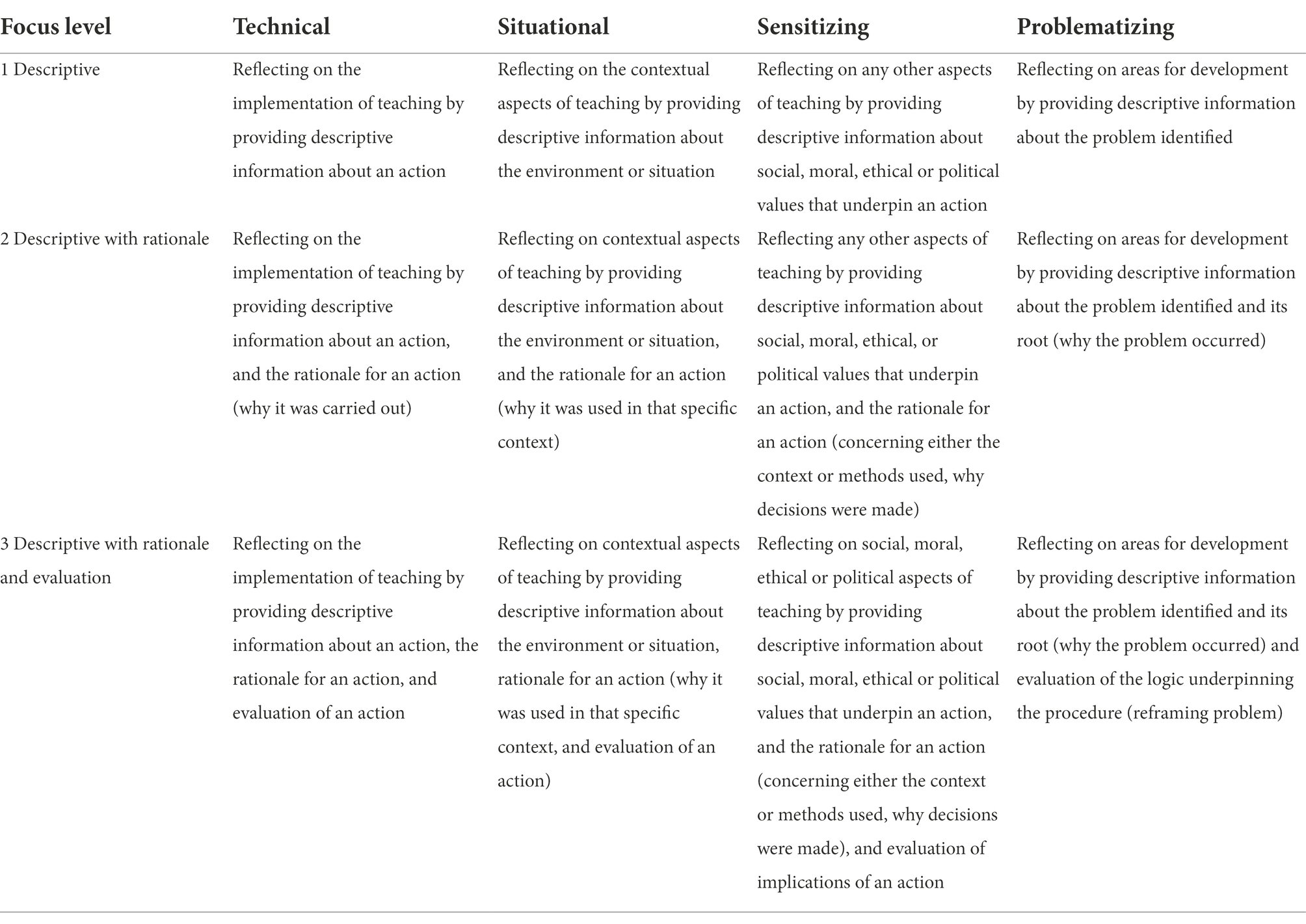

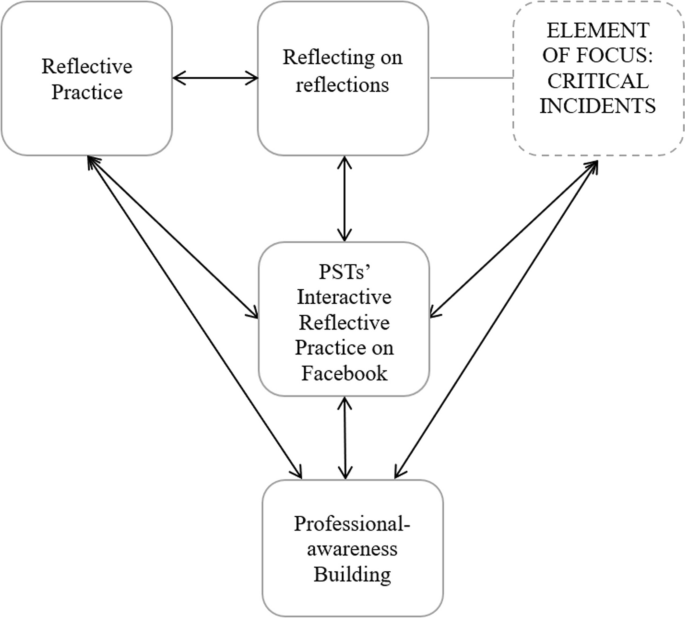

This section aims to summarize and clarify the different ways reflection has been conceptualized in the literature ( Table 1 ). Specifically, reflections have been described based on their timing, depth, and content. Notably, practitioners of reflective practices must utilize multiple types of reflection in order to more effectively improve different aspects of their teaching ( Griffiths and Tann, 1992 ).

The various conceptualizations and associated types of reflections along with examples of guiding questions

Time-Dependent

To understand the time-dependent conceptualization of reflection, we return to Schön (1983 ). He defines two particular concepts—“reflection-in-action” and “reflection-on-action”—which are delineated based on the time that the reflection takes place. Reflection-in-action is characterized as practitioners reflecting while simultaneously completing the relevant action. Reflection-on-action encompasses a practitioner reflecting on a past action, analyzing the different influences, and carefully considering the observed or potential outcomes. Reflection-in-action is perceived as more difficult due to the multiple factors that teachers have to consider at once while also ensuring that the lesson carries on.

Later work built on this initial description of time-dependent reflections. In particular, Loughran renamed the original two timings to make them more intuitive and added one time point ( Loughran, 2002a ). The three categories include: “anticipatory,” “contemporaneous,” and “retrospective,” wherein actions taken, or to be taken, are contemplated before, during, and after an educating experience, respectively. It should be noted that both Loughran’s and Schön’s models are able to function in tandem with the depth- or content-based understandings of reflections, which are described in the next sections.

Depth of Reflections

Conceptualizing reflection in terms of depth has a long history in the literature (see Section 5.1 in the Supplemental Material for a historical view of the depth-based model of reflections). Thankfully, Larrivee (2008a) designed a depth-classification system that encompasses an array of terminologies and explanations pre-existing in the literature. This classification includes a progression in reflective practices across four levels: “pre-reflection,” “surface,” “pedagogical,” and “critical reflection.”

During the pre-reflection stage, educators do not engage in reflections. They are functioning in “survival mode” ( Larrivee, 2008a , p. 350; Campoy, 2010 , p. 17), reacting automatically to situations without considering alternatives and the impacts on the students ( Larrivee, 2008a ; Campoy, 2010 ). At this stage, educators may feel little agency, consider themselves the victims of coincidental circumstances, or attribute the ownership of problems to others such as their students, rather than themselves ( Larrivee, 2008a ; Campoy, 2010 ). They are unlikely to question the status quo, thereby failing to consider and adapt to the needs of the various learners in their classrooms ( Larrivee, 2008a ; Campoy, 2010 ). While the description of educators at this level is non-ideal, educators at the pre-reflection level are not ill intended. However, the pre-reflective level is present among practitioners, as evidenced in a 2015 study investigating 140 English as a Foreign Language educators and a 2010 analysis of collected student reflections ( Campoy, 2010 ; Ansarin et al. , 2015 ). The presence of pre-reflective educators is also readily apparent in the authors’ ongoing research. As such, being aware of the pre-reflection stage is necessary for beginning practitioners, and this knowledge is perhaps most useful for designers of professional development programs.

The first true level of reflection is surface reflection. At this level, educators are concerned about achieving a specific goal, such as high scores on standardized tests. However, these goals are only approached through conforming to departmental norms, evidence from their own experiences, or otherwise well-established practices ( Larrivee, 2008a ). In other words, educators at this level question whether the specific pedagogical practices will achieve their goals, but they do not consider any new or nontraditional pedagogical practices or question the current educational policies ( Campoy, 2010 ). Educators’ reflections are grounded in personal assumptions and influenced by individuals’ unexamined beliefs and unconscious biases.

At the pedagogical level, educators “reflect on educational goals, the theories underlying approaches, and the connections between theoretical principles and practice.” ( Larrivee, 2008a , p. 343). At this level, educators also consider their own belief systems and how those systems relate to their practices and explore the problem from different perspectives. A representative scenario at this level includes: teachers contemplating their various teaching methods and considering their observed outcomes in student comprehension, alternative viewpoints, and also the current evidence-based research in education. Subsequently, they alter (or maintain) their previous teaching practices to benefit the students. In doing so, more consideration is given to possible factors than in surface reflection. This category is quite broad due to the various definitions present in the literature ( Larrivee, 2008a ). However, there is a common emphasis on the theory behind teaching practices, ensuring that practice matches theory, and the student outcomes of enacted teaching practices ( Larrivee, 2008a ).

The last level of reflection categorized by Larrivee is critical reflection, wherein educators consider the ethical, moral, and political ramifications of who they are and what they are teaching to their students ( Larrivee, 2008a ). An approachable way of thinking about critical reflection is that the practitioners are challenging their assumptions about what is taught and how students learn. In doing so, educators evaluate their own views, assertions, and assumptions about teaching, with attention paid to how such beliefs impact students both as learners and as individuals ( Larrivee, 2005 , 2008b ). Through practicing critical reflection, societal issues that affect teaching can be uncovered, personal views become evidence based rather than grounded in assumptions, and educators are better able to help a diverse student population.

Larrivee used this classification to create a tool for measuring the reflectivity of teachers (see Section 4.1 of the Supplemental Material).

Content of Reflections

The third type of reflection is one in which what is being reflected on is the defining feature. One such example is Valli’s five types of reflection ( 1997 ): “technical reflection,” “reflection-in and on-action,” “deliberative reflection,” “personalistic reflection,” and “critical reflection.” Note that Valli’s conceptions of the two types of reflection—reflection-in and on-action, and critical reflection—are congruent with the descriptions provided in the Time-Dependent and Depth sections of this Essay , respectively, and will thus not be detailed in this section.

In a technical reflection, educators evaluate their instructional practices in light of the findings from the research on teaching and learning ( Valli, 1997 ). The quality of this type of reflection is based on the educators’ knowledge of this body of work and the extent to which their teaching practices adhere to it. For example, educators would consider whether they are providing enough opportunities for their students to explain their reasoning to one another during class. This type of reflection does not focus on broader topics such as the structure and content of the curriculum or issues of equity.

Deliberative reflection encompasses “a whole range of teaching concerns, including students, the curriculum, instructional strategies, the rules and organization of the classroom” ( Valli, 1997 , p. 75). In this case, “deliberative” comes from the practitioners having to debate various external viewpoints and perspectives or research that maybe be in opposition. As such, they have an internal deliberation when deciding on the best actions for their specific teaching situations. The quality of the reflection is based on the educators’ ability to evaluate the various perspectives and provide sound reasoning for their decisions.

Personalistic reflection involves educators’ personal growth as well as the individual relationships they have with their students. Educators engaged in this type of reflection thoughtfully explore the relationships between their personal and professional goals and consider the various facets of students’ lives with the overarching aim of providing the best experience. The quality of the reflection is based on an educator’s ability to empathize.

To manage the limitations of each type of reflections, Valli recommended that reflective practitioners not focus solely on a specific type of reflection, but rather engage with multiple types of reflections, as each addresses different questions. It is important to note that some types of reflections may be prerequisite to others and that some may be more important than others; for example, Valli stated that critical reflections are more valuable than technical reflections, as they address the important issues of justice. The order of Valli’s types of reflection provided in Table 1 reflects her judgment on the importance of the questions that each type of reflection addresses.

HOW CAN I ENGAGE IN REFLECTION?

Larrivee suggested that there is not a prescribed strategy to becoming a reflective practitioner but that there are three practices that are necessary: 1) carving time out for reflection, 2) constantly problem solving, and 3) questioning the status quo ( Larrivee, 2000 ). This section of the Essay provides a buffet of topics for consideration and methods of organization that support these three practices. This section is intended to assist educators in identifying their preferred mode of reflection and to provide ideas for professional development facilitators to explicitly infuse reflective practices in their programs.

For educators who are new to reflective practices, it is useful to view the methods presented as “transforming what we are already doing, first and foremost by becoming more aware of ourselves, others, and the world within which we live” ( Rodgers and Laboskey, 2016 , p. 101) rather than as a complete reformation of current methods.

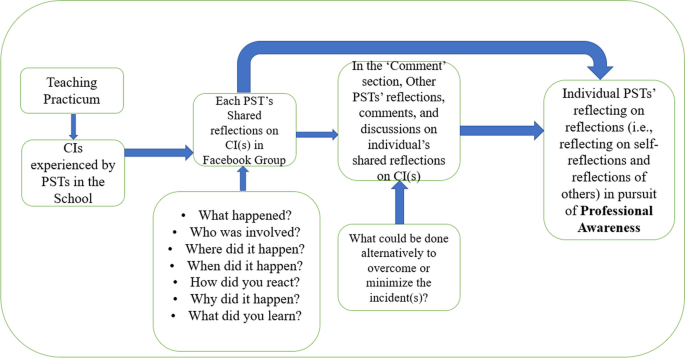

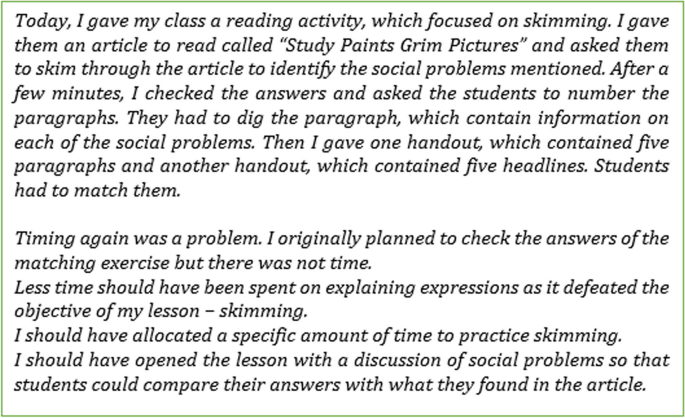

Focus of the Reflection: Critical Incident

When practicing reflection, a critical incident may be identified or presented in order to ignite the initial reflection or to foster deeper thought by practitioners ( Tripp, 2011 ). Critical incidents are particular situations that become the focus of reflections. Farrell described critical incidents in education as unplanned events that hold the potential to highlight misconceptions and foster greater and newer understanding about teaching and learning ( 2008 ). These can be situations ranging from students not understanding a foundational concept from a previous course to considering how to navigate the analysis of a data set that includes cultural background and socioeconomic status.

Critical incidents are used, because meaningful reflection is often a result of educators experiencing a problem or some form of cognitive dissonance concerning teaching practices and approaches to their students ( Lee, 2005 ). Therefore, it is most effective to combine techniques, which are outlined later in this section, with a critical incident to force practitioners into a new and difficult positions relating to education. Larrivee details that a sense of “uncertainty, dissonance, dilemma, problem, or conflict” is extremely valuable to personal reflection and growth ( 2008b , p. 93). Thus, unsettling experiences encourage changes to action far more than reflecting on typical teaching/learning interactions. This is an inherently uncomfortable experience for the practitioner, as feelings of self-doubt, uncertainty, anger, and self- or peer-rejection can come to the surface ( Larrivee, 2008b ). Yet, it is when educators are in an uncomfortable position that they are best able to challenge their learned assertions about what they are teaching and how they are supporting their students’ learning. This requires a conscious effort on the part of the educator. Humans tend to function automatically based on their past experiences and ingrained beliefs. This results in certain aspects of events being ignored while others become the driving force behind reactions. In a sense, humans have a “filter system” that can unconsciously eliminate the most effective course of action; this results in humans functioning in a cycle in which current, unquestioned beliefs determine which data and experiences are given attention ( Larrivee, 2000 , p. 295).

Critical incidents highlight any dissonance present in one’s actions, enabling practitioners to tackle social, ethical, political, and pedagogical issues that may be systemic to their departments, their fields, or their cultures. Critical incidents foster critical reflection (under the depth- and content-based models) even in novice teachers ( Pultorak, 1996 ; Griffin, 2003 ). It is because of the difficulty and uncertainty posed by critical incidents that they are widely promoted as an invaluable aspect of reflective practices in education. Therefore, the analysis of critical incidents, whether they are case studies or theoretical examples, has been used in educating both pre-service ( Griffin, 2003 ; Harrison and Lee, 2011 ) and current educators ( Benoit, 2013 ).

Scaffoldings Promoting Reflections

Once a critical incident has been identified, the next step is structuring the reflection itself. Several scaffolding models exist in the literature and are described in Section 3 of the Supplemental Material. As reflections are inherently personal, educators should use the scaffolding that works best for them. Two scaffoldings that have been found to be useful in developing reflective practices are Bain’s 5R and Gibbs’s reflective cycle.

Bain et al. (2002) created the 5R framework to support the development of pre-service teachers into reflective practitioners. The framework includes the following five steps ( Bain et al. , 2002 ):

- Reporting involves considering a particular experience and the contextual factors that surround it.

- Responding is when the individual practitioners verbalize their feelings, thoughts, and other reactions that they had in response to the situation.

- Relating is defined as teachers making connections between what occurred recently and their previously obtained knowledge and skill base.

- Reasoning then encourages the practitioners to consider the foundational concepts and theories, as well as other factors that they believe to be significant, in an effort to understand why a certain outcome was achieved or observed.

- Finally, reconstructing is when the teachers take their explanations and uses them to guide future teaching methods, either to encourage a similar result or to foster a different outcome.

This framework facilitates an understanding of what is meant by and required for reflective practices. For a full explanation of Bain’s scaffolding and associated resources, see Sections 1.2 and 3.3 in the Supplemental Material.

A popular scaffolding for promoting reflective practices is the reflective learning cycle described by Gibbs (1988) . This cycle for reflection has been extensively applied in teacher preparation programs and training of health professionals ( Husebø et al. , 2015 ; Ardian et al. , 2019 ; Markkanen et al. , 2020 ). The cycle consists of six stages:

- Description: The practitioner first describes the situation to be reflected on in detail.

- Feelings: The practitioner then explores their feelings and thoughts processes during the situation.

- Evaluation: The practitioner identifies what went well and what went wrong.

- Analysis: The practitioner makes sense of the situation by exploring why certain things went well while others did not.

- Conclusions: The practitioner summarizes what they learned from their analysis of the situation.

- Personal action plans: The practitioner develops a plan for what they would do in a similar situation in the future and what other steps they need to take based on what they learn (e.g., gain some new skills or knowledge).

For a full explanation of Gibbs’s scaffolding and associated resources, see Sections 1.3 and 3.4 in the Supplemental Material.

We see these two models as complementary and have formulated a proposed scaffolding for reflection by combining the two models. In Table 2 , we provide a short description of each step and examples of reflective statements. The full scaffolding is provided in Section 3.6 of the Supplemental Material.

Proposed scaffolds for engaging in reflective practices a

a An expanded version is provided in Section 3.6 of the Supplemental Material.

Even with the many benefits of these scaffolds, educators must keep in mind the different aspects and levels of reflection that should be considered. Especially when striving for higher levels of reflection, the cultural, historical, and political contexts must be considered in conjunction with teaching practices for such complex topics to affect change ( Campoy, 2010 ). For instance, if equity and effectiveness of methods are not contemplated, there is no direct thought about how to then improve those aspects of practice.

Modalities for Reflections

The different scaffolds can be implemented in a wide variety of practices ( Table 3 ). Of all the various methods of reflection, reflective writing is perhaps the most often taught method, and evidence has shown that it is a deeply personal practice ( Greiman and Covington, 2007 ). Unfortunately, many do not continue with reflective writing after a seminar or course has concluded ( Jindal‐Snape and Holmes, 2009 ). This may be due to the concern of time required for the physical act of writing. In fact, one of the essential practices for engaging in effective reflections is creating a space and time for personal, solitary reflection ( Larrivee, 2000 ); this is partially due to the involvement of “feelings of frustration, insecurity, and rejection” as “taking solitary time helps teachers come to accept that such feelings are a natural part of the change process” while being in a safe environment ( Larrivee, 2000 , p. 297). It is important to note that reflective writing is not limited to physically writing in a journal or typing into a private document; placing such a limitation may contribute to the practice being dropped, whereas a push for different forms of reflection will keep educators in practice ( Dyment and O'Connell, 2014 ). Reflective writings can include documents such as case notes ( Jindal‐Snape and Holmes, 2009 ), reviewing detailed lesson plans ( Posthuma, 2012 ), and even blogging ( Alirio Insuasty and Zambrano Castillo, 2010 ; van Wyk, 2013 ; Garza and Smith, 2015 ).

Common methods to engage in reflective practices

The creation of a blog or other online medium can help foster reflection. In addition to fostering reflection via the act of writing on an individual level, this online form of reflective writing has several advantages. One such benefit is the readily facilitated communication and collaboration between peers, either through directly commenting on a blog post or through blog group discussions ( Alirio Insuasty and Zambrano Castillo, 2010 ; van Wyk, 2013 ; Garza and Smith, 2015 ). “The challenge and support gained through the collaborative process is important for helping clarify beliefs and in gaining the courage to pursue beliefs” ( Larrivee, 2008b , p. 95). By allowing other teachers to comment on published journal entries, a mediator role can be filled by someone who has the desired expertise but may be geographically distant. By this same logic, blogs have the great potential to aid teachers who themselves are geographically isolated.

Verbal reflections through video journaling (vlogs) follows the same general methods as writing. This method has the potential to be less time intensive ( Clarke, 2009 ), which may lower one of the barriers facing practitioners. Greiman and Covington (2007) identified verbal reflection as one of the three preferred modalities of reflection by student teachers. By recording their verbal contemplations and reflections, practitioners can review their old thoughts about different course materials, enabling them to adjust their actions based on reflections made when observations were fresh in their mind. Students learning reflective practices also noted that recorded videos convey people’s emotions and body language—reaching a complexity that is not achievable with plain text or audio ( Clarke, 2009 ).

If writing or video journaling is not appealing, another method to facilitate reflective practices is that of making video recordings of teaching experiences in vivo. This differs from vlogs, which are recorded after the teaching experiences. A small longitudinal qualitative study indicated that the video recordings allowed participants to be less self-critical and to identify effective strategies they were employing ( Jindal‐Snape and Holmes, 2009 ). Additionally, beginning teachers found the most value in videotaping their teaching as compared with electronic portfolios and online discussions ( Romano and Schwartz, 2005 ). By recording their teaching practices, practitioners can use a number of clearly outlined self- and peer-assessments, as detailed in Section 4 of the Supplemental Material. However, it should be noted that all three technology-driven methods used in the study by Romano and Schwartz (2005) were helpful for the participants, and as reflective practices are inherently personal, many methods should be considered by practitioners new to purposeful reflection.

Group efforts, such as group discussions or community meetings, can foster reflective thinking, thereby encouraging reflective practices. “The checks and balances of peers’ and critical friends’ perspectives can help developing teachers recognize when they may be devaluing information or using self-confirming reasoning, weighing evidence with a predisposition to confirm a belief or theory, rather than considering alternative theories that are equally plausible” ( Larrivee, 2008b , p. 94). These benefits are essential to help educators reach the higher levels of reflection (i.e., pedagogical reflection and critical reflection), as it can be difficult to think of completely new viewpoints on one’s own, especially when educators are considering the needs of diverse students yet only have their own experiences to draw upon. Henderson et. al . (2011) review of the literature found that successful reports of developing reflective practitioners as a strategy for change had two commonalities. One of these was the presence of either a community where experiences are shared ( Gess-Newsome et al. , 2003 ; Henderson et al. , 2011 ) or of an additional participant providing feedback to the educator ( Penny and Coe, 2004 ; McShannon and Hynes, 2005 ; Henderson et al. , 2011 ). The second commonality was the presence of support by a change agent ( Hubball et al. , 2005 ; Henderson et al. , 2011 ), which is far more context reliant.

Even in the absence of change agent support, peer observation can be implemented as a tool for establishing sound reflective practices. This can be accomplished through informal observations followed by an honest discussion. It is vital for the correct mindset to be adopted during such a mediation session, as the point of reflection is in assessing the extent to which practitioners’ methods allow them to achieve their goals for student learning. This cannot be done in an environment where constructive feedback is seen as a personal critique. For example, it was found that peers who simply accepted one another’s practices out of fear of damaging their relationships did not benefit from peer observation and feedback ( Manouchehri, 2001 ); however, an initially resistant observer was able to provide valuable feedback after being prompted by the other participant ( Manouchehri, 2001 ). One approach to ensure the feedback promotes reflections is for the observer and participant to meet beforehand and have a conversation about areas on which to focus feedback. The follow-up conversation focuses first on these areas and can be expanded afterward to other aspects of the teaching that the observer noticed. Observation protocols (provided in Section 4.2 in the Supplemental Material) can also be employed in these settings to facilitate the focus of the reflection.

For those interested in assessing their own or another’s reflection, Section 4 in the Supplemental Material will be helpful, as it highlights different tools that have been shown to be effective and are adaptable to different situations.

WHAT BARRIERS MIGHT I FACE?

It is typical for educators who are introducing new practices in their teaching to experience challenges both at the personal and contextual levels ( Sturtevant and Wheeler, 2019 ). In this section, we address the personal and contextual barriers that one may encounter when engaging in reflective practices and provide advice and recommendations to help address these barriers. We also aim to highlight that the difficulties faced are commonly shared by practitioners embarking on the complex journey of becoming reflective educators.

Personal Barriers

Professional development facilitators who are interested in supporting their participants’ growth as reflective practitioners will need to consider: 1) the misunderstandings that practitioners may have about reflections and 2) the need to clearly articulate the purpose and nature of reflective practices. Simply asking practitioners to reflect will not lead to desirable results ( Loughran, 2002b ). Even if the rationale and intent is communicated, there is also the pitfall of oversimplification. Practitioners may stop before the high levels of reflection (e.g., critical reflection) are reached due to a lack of in-depth understanding of reflective practices ( Thompson and Pascal, 2012 ). Even if the goals are understood and practitioners intend to evaluate their teaching practices on the critical level, there can still be confusion about what reflective practices require from practitioners. The theory of reflective practices may be grasped, but it is not adequately integrated into how practitioners approach teaching ( Thompson and Pascal, 2012 ). We hope that this Essay and associated Supplemental Material provide a meaningful resource to help alleviate this challenge.

A concern often raised is that the level of critical reflection is not being reached ( Ostorga, 2006 ; Larrivee, 2008a ). Considering the impacts that student–teacher interactions have on students beyond the classroom is always a crucial part of being an educator. In terms of practicality, situations being considered may not be conducive to this type of reflection. Consider an educator who, after a formative assessment, realizes that students, regardless of ethnicity, nationality, or gender, did not grasp a foundational topic that is required for the rest of the course. In such a case, it is prudent to consider how the information was taught and to change instructional methods to adhere to research-based educational practices. If the information was presented in a lecture-only setting, implementing aspects of engagement, exploration, and elaboration on the subject by the students can increase understanding ( Eisenkraft, 2003 ). If the only interactions were student–teacher based and all work was completed individually, the incorporation of student groups could result in a deeper understanding of the material by having students act as teachers or by presenting students with alternative way of approaching problems (e.g., Michaelsen et al. , 1996 ). Both of these instructional changes are examples that can result from pedagogical reflection and are likely to have a positive impact on the students. As such, educators who practice any level of reflection should be applauded. The perseverance and dedication of practitioners cannot be undervalued, even if their circumstances lead to fewer instances of critical reflection. We suggest that communities of practice such as faculty learning communities, scholarship of teaching and learning organizations, or professional development programs are excellent avenues to support educators ( Baker et al. , 2014 ; Bathgate et al. , 2019 ; Yik et al. , 2022a , b ), including in the development of knowledge and skills required to reach critical reflections. For example, facilitators of these communities and programs can intentionally develop scaffolding and exercises wherein participants consider whether the deadlines and nature of assignments are equitable to all students in their courses. Professional development facilitators are strongly encouraged to be explicit about the benefits to individual practitioners concomitantly with the benefits to students (see Section 2 in the Supplemental Material), as benefits to practitioners are too often ignored yet comprise a large portion of the reasoning behind reflective practices.

At a practitioner’s level, the time requirement for participating in reflective practices is viewed as a major obstacle, and it would be disingenuous to discount this extensive barrier ( Greiman and Covington, 2007 ). Reflective practices do take time, especially when done well and with depth. However, we argue that engagement in reflective practice early on can help educators become more effective with the limited time they do have ( Brookfield, 2017 ). As educators engage in reflective practices, they become more aware of their reasoning, their teaching practices, the effectiveness of said practices, and whether their actions are providing them with the outcomes they desire ( Thompson and Pascal, 2012 ). Therefore, they are able to quickly and effectively troubleshoot challenges they encounter, increasing the learning experiences for their students. Finally, we argue that the consistent engagement in reflective practices can significantly facilitate and expedite the writing of documents necessary for annual evaluations and promotions. These documents often require a statement in which educators must evaluate their instructional strategies and their impact on students. A reflective practitioner would have a trail of documents that can easily be leveraged to write such statement.

Contextual Factors

Environmental influences have the potential to bring reflective practices to a grinding halt. A paradigm shift that must occur to foster reflective teacher: that of changing the teacher’s role from a knowledge expert to a “pedagogic expert” ( Day, 1993 ). As with any change of this magnitude, support is necessary across all levels of implementation and practitioners to facilitate positive change. Cole (1997) made two observations that encapsulate how institutions can prevent the implementation of reflective practices: first, many educators who engage in reflective practices do so secretly. Second, reflections are not valued in academic communities despite surface-level promotions for such teaching practices; institutions promote evidence-based teaching practices, including reflection, yet instructors’ abilities as educators do not largely factor into promotions, raises, and tenure ( Brownell and Tanner, 2012 ; Johnson et al. , 2018 ). The desire for educators to focus on their teaching can become superficial, with grants and publications mattering more than the results of student–teacher interactions ( Cole, 1997 ; Michael, 2007 ).

Even when teaching itself is valued, the act of changing teaching methods can be resisted and have consequences. Larrivee’s (2000) statement exemplifies this persistent issue:

Critically reflective teachers also need to develop measures of tactical astuteness that will enable them to take a contrary stand and not have their voices dismissed. One way to keep from committing cultural suicide is to build prior alliances both within and outside the institution by taking on tasks that demonstrate school loyalty and build a reputation of commitment. Against a history of organizational contributions, a teacher is better positioned to challenge current practices and is less readily discounted. (p. 298)

The notion that damage control must be a part of practicing reflective teaching is indicative of a system that is historically opposed to the implementation of critical reflection ( Larrivee, 2000 ). We view this as disheartening, as the goal of teaching should be to best educate one’s students. Even as reflective practices in teaching are slowly becoming more mainstream, contextual and on-site influences still have a profound impact on how teachers approach their profession ( Smagorinsky, 2015 ). There must be a widespread, internal push for change within departments and institutions for reflective practices to be easily and readily adopted.

The adoption of reflective practices must be done in a way that does not negate its benefits. For example, Galea (2012) highlights the negative effects of routinizing or systematizing this extremely individual and circumstance-based method (e.g., identification of specific areas to focus on, standardized timing and frequency of reflections). In doing so, the systems that purportedly support teachers using reflection remove their ability to think of creative solutions, limit their ability to develop as teachers, and can prevent an adequate response to how the students are functioning in the learning environment ( Tan, 2008 ). Effective reflection can be stifled when reflections are part of educators’ evaluations for contract renewal, funding opportunities, and promotions and tenure. Reflective practices are inherently vulnerable, as they involve both being critical of oneself and taking responsibility for personal actions ( Larrivee, 2008b ). Being open about areas for improvement is extremely difficult when it has such potential negative impacts on one’s career. However, embarking on honest reflection privately, or with trusted peers and mentors, can be done separately from what is presented for evaluation. We argue that reflections can support the writing of documents to be considered for evaluation, as these documents often request the educators to describe the evolution of their teaching and its impact on students. Throughout course terms, reflections conducted privately can provide concreate ideas for how to frame an evaluation document. We argue that administrators, department chairs, and members of tenure committees should be explicit with their educators about the advantages of reflective practices in preparing evaluative documents focused on teaching.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Reflective practices are widely advocated for in academic circles, and many teaching courses and seminars include information regarding different methods of reflection. This short introduction intends to provide interested educators with a platform to begin reflective practices. Common methods presented may appeal to an array of educators, and various self- and peer-assessment tools are highlighted in Section 4 in the Supplemental Material. Reflective practices are a process and a time- and energy-intensive, but extremely valuable tool for educators when implemented with fidelity. Therefore, reflection is vital for efficacy as an educator and a requirement for educators to advance their lifelong journeys as learners.

To conclude, we thought the simple metaphor provided by Thomas Farrell best encapsulates our thoughts on reflective practices within the context of teaching: Reflective practices are “a compass of sorts to guide teachers when they may be seeking direction as to what they are doing in their classrooms. The metaphor of reflection as a compass enables teachers to stop, look, and discover where they are at that moment and then decide where they want to go (professionally) in the future” ( Farrell, 2012 , p. 7).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We would like to thank Annika Kraft, Jherian Mitchell-Jones, Emily Kable, Dr. Emily Atieh, Dr. Brandon Yik, Dr. Ying Wang, and Dr. Lu Shi for their constructive feedback on previous versions of this article. This material is based upon work supported by NSF 2142045. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

- Alirio Insuasty, E., Zambrano Castillo, L. C. (2010). Exploring reflective teaching through informed journal keeping and blog group discussion in the teaching practicum . Profile Issues in Teachers Professional Development , 12 ( 2 ), 87–105. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ansarin, A. A., Farrokhi, F., Rahmani, M. (2015). Iranian EFL teachers’ reflection levels: The role of gender, experience, and qualifications . Asian Journal of Applied Linguistics , 2 ( 2 ), 140–155. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ardian, P., Hariyati, R. T. S., Afifah, E. (2019). Correlation between implementation case reflection discussion based on the Graham Gibbs Cycle and nurses’ critical thinking skills . Enfermeria Clinica , 29 , 588–593. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bain, J., Ballantyne, R., Mills, C., Lester, N. (2002). Reflecting on practice: Student teachers’ perspectives . Flaxton, QLD, Australia: Post Pressed. [ Google Scholar ]

- Baker, L. A., Chakraverty, D., Columbus, L., Feig, A. L., Jenks, W. S., Pilarz, M., Wesemann, J. L. (2014). Cottrell Scholars Collaborative New Faculty Workshop: Professional development for new chemistry faculty and initial assessment of its efficacy . Journal of Chemical Education , 91 ( 11 ), 1874–1881. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bathgate, M. E., Aragón, O. R., Cavanagh, A. J., Frederick, J., Graham, M. J. (2019). Supports: A key factor in faculty implementation of evidence-based teaching . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 18 ( 2 ), ar22. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Benoit, A. (2013). Learning from the inside out: A narrative study of college teacher development [Doctoral Dissertation, Lesley University] . Graduate School of Education. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/education_dissertations/29

- Brems, C., Baldwin, M. R., Davis, L., Namyniuk, L. (1994). The imposter syndrome as related to teaching evaluations and advising relationships of university faculty members . Journal of Higher Education , 65 ( 2 ), 183–193. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brookfield, S. D. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher . Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brownell, S. E., Tanner, K. D. (2012). Barriers to faculty pedagogical change: Lack of training, time, incentives, and … tensions with professional identity? CBE—Life Sciences Education , 11 ( 4 ), 339–346. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Campoy, R. (2010). Reflective thinking and educational solutions: Clarifying what teacher educators are attempting to accomplish . SRATE Journal , 19 ( 2 ), 15–22. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chrousos, G. P., Mentis, A.-F. A. (2020). Imposter syndrome threatens diversity . Science , 367 ( 6479 ), 749–750. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clarke, L. (2009). Video reflections in initial teacher education . British Journal of Educational Technology , 40 ( 5 ), 959–961. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cole, A. L. (1997). Impediments to reflective practice: Toward a new agenda for research on teaching . Teachers and Teaching , 3 ( 1 ), 7–27. [ Google Scholar ]

- Collins, K. H., Price, E. F., Hanson, L., Neaves, D. (2020). Consequences of stereotype threat and imposter syndrome: The personal journey from Stem-practitioner to Stem-educator for four women of color . Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education , 19 ( 4 ), 10. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis, M. (2003). Barriers to reflective practice: The changing nature of higher education . Active Learning in Higher Education , 4 ( 3 ), 243–255. [ Google Scholar ]

- Day, C. (1993). Reflection: A necessary but not sufficient condition for professional development . British Educational Research Journal , 19 ( 1 ), 83–93. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dervent, F. (2015). The effect of reflective thinking on the teaching practices of preservice physical education teachers . Issues in Educational Research , 25 ( 3 ), 260–275. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dewey, J. (1933). How we think . Chelmsford, MA: Courier Corporation. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dyment, J. E., O'Connell, T. S. (2014). When the ink runs dry: Implications for theory and practice when educators stop keeping reflective journals . Innovative Higher Education , 39 ( 5 ), 417–429. [ Google Scholar ]

- Eisenkraft, A. (2003). Expanding the 5 E model: A purposed 7 E model emphasizes “transfer of learning” and the importance of eliciting prior understanding . Science Teacher , 70 ( 6 ), 56–59. [ Google Scholar ]

- Farrell, T. S. (2008). Critical incidents in ELT initial teacher training . ELT Journal , 62 ( 1 ), 3–10. [ Google Scholar ]

- Farrell, T. S. (2012). Reflecting on reflective practice: (Re) visiting Dewey and Schon . TESOL Journal , 3 ( 1 ), 7–16. [ Google Scholar ]

- Galea, S. (2012). Reflecting reflective practice . Educational Philosophy and Theory , 44 ( 3 ), 245–258. [ Google Scholar ]

- Garza, R., Smith, S. F. (2015). Pre-service teachers’ blog reflections: Illuminating their growth and development . Cogent Education , 2 ( 1 ), 1066550. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gess-Newsome, J., Southerland, S. A., Johnston, A., Woodbury, S. (2003). Educational reform, personal practical theories, and dissatisfaction: The anatomy of change in college science teaching . American Educational Research Journal , 40 ( 3 ), 731–767. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods . London, England: Further Education Unit. [ Google Scholar ]

- Greiman, B., Covington, H. (2007). Reflective thinking and journal writing: Examining student teachers; perceptions of preferred reflective modality, journal writing outcomes, and journal structure . Career and Technical Education Research , 32 ( 2 ), 115–139. [ Google Scholar ]

- Griffin, M. L. (2003). Using critical incidents to promote and assess reflective thinking in preservice teachers . Reflective Practice , 4 ( 2 ), 207–220. [ Google Scholar ]

- Griffiths, M., Tann, S. (1992). Using reflective practice to link personal and public theories . Journal of Education for Teaching , 18 ( 1 ), 69–84. [ Google Scholar ]

- Harrison, J. K., Lee, R. (2011). Exploring the use of critical incident analysis and the professional learning conversation in an initial teacher education programme . Journal of Education for Teaching , 37 ( 2 ), 199–217. [ Google Scholar ]

- Henderson, C., Beach, A., Finkelstein, N. (2011). Facilitating change in undergraduate STEM instructional practices: An analytic review of the literature . Journal of Research in Science Teaching , 48 ( 8 ), 952–984. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hubball, H., Collins, J., Pratt, D. (2005). Enhancing reflective teaching practices: Implications for faculty development programs . Canadian Journal of Higher Education , 35 ( 3 ), 57–81. [ Google Scholar ]

- Husebø, S. E., O'Regan, S., Nestel, D. (2015). Reflective practice and its role in simulation . Clinical Simulation in Nursing , 11 ( 8 ), 368–375. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jindal-Snape, D., Holmes, E. A. (2009). A longitudinal study exploring perspectives of participants regarding reflective practice during their transition from higher education to professional practice . Reflective Practice , 10 ( 2 ), 219–232. [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson, E., Keller, R., Fukawa-Connelly, T. (2018). Results from a survey of abstract algebra instructors across the United States: Understanding the choice to (not) lecture . International Journal of Research in Undergraduate Mathematics Education , 4 , 254–285. [ Google Scholar ]

- Larrivee, B. (2000). Transforming teaching practice: Becoming the critically reflective teacher . Reflective Practice , 1 ( 3 ), 293–306. https://doi.org/doi: 10.1080/14623940020025561 [ Google Scholar ]

- Larrivee, B. (2005). Authentic classroom management: Creating a learning community and building reflective practice . Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [ Google Scholar ]

- Larrivee, B. (2008a). Development of a tool to assess teachers’ level of reflective practice . Reflective Practice , 9 ( 3 ), 341–360. 10.1080/14623940802207451 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Larrivee, B. (2008b). Meeting the challenge of preparing reflective practitioners . New Educator , 4 ( 2 ), 87–106. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee, H.-J. (2005). Understanding and assessing preservice teachers’ reflective thinking . Teaching and Teacher Education , 21 ( 6 ), 699–715. [ Google Scholar ]

- Loughran, J. J. (2002a). Developing reflective practice: Learning about teaching and learning through modelling . London, UK: Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Loughran, J. J. (2002b). Effective reflective practice: In search of meaning in learning about teaching . Journal of Teacher Education , 53 ( 1 ), 33–43. [ Google Scholar ]

- Manouchehri, A. (2001). Collegial interaction and reflective practice . Action in Teacher Education , 22 ( 4 ), 86–97. [ Google Scholar ]

- Markkanen, P., Välimäki, M., Anttila, M., Kuuskorpi, M. (2020). A reflective cycle: Understanding challenging situations in a school setting . Educational Research , 62 ( 1 ), 46–62. [ Google Scholar ]

- McShannon, J., Hynes, P. (2005). Student achievement and retention: Can professional development programs help faculty GRASP it? Journal of Faculty Development , 20 ( 2 ), 87–93. [ Google Scholar ]

- Michael, J. (2007). Faculty perceptions about barriers to active learning . College Teaching , 55 ( 2 ), 42–47. [ Google Scholar ]

- Michaelsen, L. K., Fink, L. D., Black, R. H. (1996). What every faculty developer needs to know about learning groups . To Improve the Academy , 15 ( 1 ), 31–57. [ Google Scholar ]

- Munby, H., Russell, T. (1989). Educating the reflective teacher: An essay review of two books by Donald Schon . Journal of Curriculum Studies , 21 ( 1 ), 71–80. [ Google Scholar ]

- Newman, S. (1999). Constructing and critiquing reflective practice . Educational Action Research , 7 ( 1 ), 145–163. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ostorga, A. N. (2006). Developing teachers who are reflective practitioners: A complex process . Issues in Teacher Education , 15 ( 2 ), 5–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Parkman, A. (2016). The imposter phenomenon in higher education: Incidence and impact . Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice , 16 ( 1 ), 51. [ Google Scholar ]

- Penny, A. R., Coe, R. (2004). Effectiveness of consultation on student ratings feedback: A meta-analysis . Review of Educational Research , 74 ( 2 ), 215–253. [ Google Scholar ]

- Posthuma, B. (2012). Mathematics teachers’ reflective practice within the context of adapted lesson study . Pythagoras , 33 ( 3 ), 1–9. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pultorak, E. G. (1996). Following the developmental process of reflection in novice teachers: Three years of investigation . Journal of Teacher Education , 47 ( 4 ), 283–291. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodgers, C., Laboskey, V. K. (2016). Reflective practice . International Handbook of Teacher Education , 2 , 71–104. [ Google Scholar ]

- Romano, M., Schwartz, J. (2005). Exploring technology as a tool for eliciting and encouraging beginning teacher reflection . Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education , 5 ( 2 ), 149–168. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action . New York, NY: Basic Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Smagorinsky, P. (2015). The role of reflection in developing eupraxis in learning to teach English . Pedagogies: An International Journal , 10 ( 4 ), 285–308. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sturtevant, H., Wheeler, L. (2019). The STEM Faculty Instructional Barriers and Identity Survey (FIBIS): Development and exploratory results . International Journal of STEM Education , 6 ( 1 ), 1–22. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tan, C. (2008). Improving schools through reflection for teachers: Lessons from Singapore . School Effectiveness and School Improvement , 19 ( 2 ), 225–238. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thompson, N., Pascal, J. (2012). Developing critically reflective practice . Reflective Practice , 13 ( 2 ), 311–325. 10.1080/14623943.2012.657795 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tripp, D. (2011). Critical incidents in teaching (classic edition): Developing professional judgement . London, England: Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Valli, L. (1997). Listening to other voices: A description of teacher reflection in the United States . Peabody Journal of Education , 72 ( 1 ), 67–88. [ Google Scholar ]

- van Wyk, M. M. (2013). Using blogs as a means of enhancing reflective teaching practice in open distance learning ecologies . Africa Education Review , 10 ( Suppl 1 ), S47–S62. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yik, B. J., Raker, J. R., Apkarian, N., Stains, M., Henderson, C., Dancy, M. H., Johnson, E. (2022a). Association of malleable factors with adoption of research-based instructional strategies in introductory chemistry, mathematics, and physics . Frontiers in Education , 7 , 1016415. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yik, B. J., Raker, J. R., Apkarian, N., Stains, M., Henderson, C., Dancy, M. H., Johnson, E. (2022b). Evaluating the impact of malleable factors on percent time lecturing in gateway chemistry, mathematics, and physics courses . International Journal of STEM Education , 9 ( 1 ), 1–23. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zahid, M., Khanam, A. (2019). Effect of Reflective Teaching Practices on the Performance of Prospective Teachers . Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology—TOJET , 18 ( 1 ), 32–43. [ Google Scholar ]

- Skip to content

- Skip to search

- Staff portal (Inside the department)

- Student portal

- Key links for students

Other users

- Forgot password

Notifications

{{item.title}}, my essentials, ask for help, contact edconnect, directory a to z, how to guides, teacher standards and accreditation, reflective practice, what does the research say.

Effective teachers continually reflect on and improve, the way they do things, but reflection is not a natural process for all teachers. Some teachers think that the toolkit is enough.

Biggs (2003) eloquently highlights that a toolkit will not necessarily lead to excellence in teaching:

Learning new techniques for teaching is like the fish that provides a meal for today; reflective practice is the net that provides the meal for the rest of one's life.

Reflective practitioners take an inquiry stance in that they actively search for understanding, and are always open to further investigation.

Timperley, Wiseman and Fung reinforced the fact that teachers need to be constantly updating and improving their practice, and engaging in lifelong learning:

It is important, therefore, for teachers to continually update and expand their professional knowledge base and to improve or revise their practices so as to meet the learning needs of their increasingly diverse students… The ever-changing knowledge base in our society means that a teaching force that uses yesterday’s professional knowledge to prepare today’s students for tomorrow’s society can no longer be tolerated.

The advantages of reflective practice

Reflective practice attitudes, reflective practice attributes, the modes of reflection.

Reflective practice provides a means for teachers to improve their practice to effectively meet the learning needs of their students. Brookfield succinctly describes the advantages of reflective practice to teachers as:

- It helps teachers to take informed actions that can be justified and explained to others and that can be used to guide further action.

- It allows teachers to adjust and respond to issues.

- It helps teachers to become aware of their underlying beliefs and assumptions about learning and teaching.

- It helps teachers promote a positive learning environment.

- It allows teachers to consciously develop a repertoire of relevant and context-specific strategies and techniques.

- It helps teachers locate their teaching in the broader institutional, social and political context and to appreciate that many factors influence student learning.

Dewey was the first to describe the 3 attitudes that form the basis of reflective practice, namely:

- open-mindedness - a willingness to consider new evidence as it occurs and to admit the possibility of error. It involves being open to other points of view, appreciating that there are many ways of looking at a particular situation or event and staying open to changing one’s own viewpoint. Part of open-mindedness is being able to let go of needing to be right or wanting to win.

- responsibility - the careful consideration of the consequences of one’s actions, especially as they affect students. It is the willingness to acknowledge that whatever one chooses to do (for example decisions about curriculum, instruction, assessment, organisation, management) will impact the lives of students in both foreseen and unforeseen ways.

- wholeheartedness - a commitment to seek every opportunity to learn and a belief that one can always learn something new.

Larivee further identified the attributes of practitioners who have these attitudes (open-minded, responsible and wholehearted) saying these practitioners:

- reflect on and learn from experience

- engage in ongoing inquiry

- solicit feedback

- remain open to alternative perspectives

- assume responsibility for their own learning

- take action to align with new knowledge and understandings

- observe themselves in the process of thinking

- are committed to continuous improvement in practice

- strive to align behaviour with values and beliefs

- seek to discover what is true.

Essential modes of, and lenses for, reflection.

Reflective practice is undertaken not just to revisit the past but to guide future action. Reflective practitioners use all 4 of the essential modes of reflection:

- Reflection-in-action is taking note of thinking and actions as they are occurring and making immediate adjustments as events unfold. Re-evaluation occurs on the spot.

- Reflection-on-action is looking back on and learning from experience or action in order to affect future action. Reflecting after an event is probably the most frequently used form of reflection.

- Reflection-for-action involves analysing practices with the purpose of taking action to change (Killion and Todnem). It includes reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action. This type of reflection is proactive in nature. Often called 'closing the gap' reflection, it focuses on closing the gap between what is and what might be.

- Reflection-within is inquiring about personal purposes, intentions and feelings. Teachers might question what is working well, what's keeping them from taking action, what's keeping their perspective limited, or why they reacted in a particular way. This is very similar to self-reflection.

The lenses for reflection

Additionally, within each mode of reflection, it's useful to reflect through various lenses. Brookfield suggests using the following 4 lenses for reflection.

The autobiographical lens (self)

The autobiographical lens, or self-reflection, is the foundation of critical reflection. It requires teachers to stand back from an experience and view it more objectively. This lens allows teachers to become aware of aspects of their pedagogy that are effective or that may need adjustment or strengthening.

The student lens

This lens allows teachers to view their practice from students’ perspectives and is often a consistently surprising element for teachers. Both self-reflection and engaging with student feedback may reveal aspects of teaching practice that need adjustment.

The colleague lens

While good teachers will engage with the first two lenses, excellent teachers may also look to peers for mentoring, advice and feedback. Engaging with colleagues and hearing their perspectives allows teachers to check, reframe, and broaden theories of practice, and to consider new ideas and approaches. It also makes teachers aware that many of the challenges in teaching are common, which can be profoundly reassuring.

The theoretical lens (literature and research)

The fourth lens found in theoretical literature fosters critically reflective teaching. An engagement with both colleagues and scholarly literature supports teachers and also clarifies the contexts in which they teach. The theoretical literature extends understanding and appreciation of learning and teaching practices, and helps teachers to see the links between their personal development path and the broader educational context.

In summary, reflective practice incorporates reflection in, on and for action as well as a reflection within.

Seeking information from various lenses serves to further strengthen reflective practice.

Use the Reflective practice questions to support reflection in action. The questions use the 4 modes of reflection and a variety of lenses.

- Australian Institute of Teaching and School Leadership. (2014) Learning from practice - workbook series.

- Biggs, J. (2003) Teaching for Quality Learning at University: What the Student Does (2nd ed.) Berkshire: SRHE & Open University Press.

- NSW Education Standards Authority Australian Professional Standards for Teachers.

- Brookfield, S. 1995 Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Dewey, J. 1938 Logic: The Theory of Inquiry New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Killion, J. & Todnem, G (1991) ?A process of personal theory building? Educational Leadership, 48(6).

- Larrivee, B. (2006) An Educator?s Guide to Teacher Reflection, Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Timperley, H. Wiseman, J. Fung, I. (2003) The Sustainability of Professional Development in Literacy, Part 2. Final report to the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Education, Wellington New Zealand.

Visit the department's Beginning Teacher information hub

Join the department's beginning teacher support network on yammer.

- Deakin University

- Learning and Teaching

Critical reflection for assessments and practice

- Critical reflection

Critical reflection for assessments and practice: Critical reflection

- Reflective practice

- How to reflect

- Critical reflection writing

- Recount and reflect

What is critical reflection?

"We don't see things as they are, we see them as we are".

Anais Nin - Seduction of the Minotour (1961)

Critical reflection can be defined in different ways but at core it's an extension of critical thinking. It involves learning from everyday experiences and situations. You need to ask questions of yourself and about your actions to better understand why things happened.

Critical reflection is active not passive

Critical reflection is active personal learning and development where you take time to engage with your thoughts, feelings and experiences. It helps us examine the past, look at the present and then apply learnings to future experiences or actions.

Critical reflection is also focused on a central question, “Can I articulate the doing that is shaped by the knowing.” What this means is that critical reflection and reflective practice are tied together. You can use critical reflection as a tool to analyse your reflections more critically which allows you to evaluate , inform and continually change your practice .

Critical reflection: think, feel, and do

The events, experiences or interactions you choose to critically reflect on can be either positive or negative. They may be an interesting interaction or an everyday occurrence.

No matter what it is, when you are critically reflecting it is a good idea to think about how the experience, event or interaction made you:

And what you can do to change your practice.

What you think, feel and do as a result of critical reflective learning will shape the what, how and why of future behaviours, actions and work.

Critical reflection: what influences your practice

Critical reflection also means thinking about why you make certain choices in your practice. Sometimes this may feel uncomfortable because it can highlight your assumptions, biases, views and behaviours. But it is important to take the time to think about how your own experiences influence your study, your work and your life in general. This involves you recognising how your perspectives and values influence the decisions you make.

Click on the plus (+) icons beneath each thought bubble to view some example assumptions that may influence practice.

Scaffolded approach to think, feel, and do in your practice

There is quite a bit to keep in mind with using critical reflective to shape your practice. Making critical reflection part of your everyday is easier if you have a framework to refer to.

This critical reflection and reflective practice framework is a handy resource for you to keep. Download the framework and use it as a prompt when doing critical reflective assessments at uni or as part of developing reflective practice in your work.

DOWNLOAD FRAMEWORK (PDF, 1MB)

Critical reflection includes research and evidence-base

Why you need to use academic literature in critical reflections can be hard to understand as you may feel that you don’t need to draw on other sources when discussing your own experiences. Critical reflections involve both personal perspective and theory = the need to use academic literature.

Personal plus theory underpins reflective practice

Keep in mind that when you are at university there is an expectation that you support the points you make by referring to information from relevant, credible sources.

You also need to think about how theories can influence and inform your practice. Reflective practice relies on evidence, with research informing your reflection and what changes to practice you intend to put into play. This means you will need to use academic literature to support what you are saying in your reflection.

Learn more about including literature in your writing. Deakin’s academic skills guide on Using Sources will help you weave academic literature into your critical reflection assessments. It’s focused on supporting evidence in your writing.

- << Previous: Reflective practice

- Next: How to reflect >>

- Last Updated: Mar 15, 2024 4:53 PM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/critical-reflection-guide

Embracing Reflection for Enhanced Education

- Author: Responsive Learning

- Publishing Editor: Krista Miller

- 3 minute read

- April 23, 2024

In the heart of San Antonio, Texas, Martin Silverman brings to life an approach that is transforming educational landscapes. With a career spanning four decades, Silverman introduces us to the Reflective Practice Model, a vital tool for educators and school leaders striving for excellence. This isn’t just about teaching; it’s about evolving, reflecting, and pushing the boundaries of traditional education to new heights, particularly in challenging socioeconomic environments.

Unveiling the Reflective Practice Model

The Reflective Practice Model stands as a testament to the power of introspection in the educational realm. It champions the idea that to truly enhance our schools and the learning experiences within them, we must take a step back to examine and refine our teaching methodologies. “In my experience, I have found that practice is less looked at in PLC than products,” Silverman says, shedding light on the critical shift from product to process that this model advocates. Here are some key insights:

- The Reflective Practice Model encourages a deep dive into teaching methodologies for continuous improvement.

- It shifts the focus from end results to the processes that lead to educational success.

- Silverman’s vast experience underscores the model’s efficacy in diverse educational settings.

With these insights in hand, let’s explore the foundational elements that make the Reflective Practice Model a catalyst for educational transformation.

Building Blocks for Success

Before diving into the specifics of the model, it’s pivotal to grasp the principles guiding this reflective journey. These principles extend beyond mere theory; they are practical, actionable, and form the cornerstone of fostering a culture of continuous improvement. Consider these essential elements: