Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Department of English

First-Year Writing Program

Classroom activities.

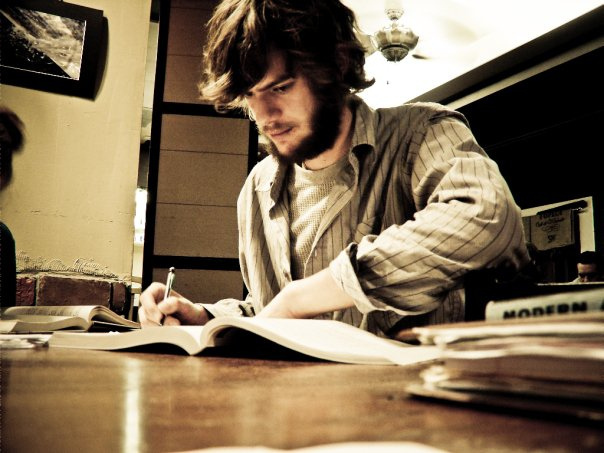

UConn first-year writing (FYW) courses teach students how to write and share their work through project-based learning.

Our courses emphasize collaboration and discovery. During class, students make progress toward an ongoing academic project. They consult with their instructors and receive feedback from their peers. Classroom activities also introduce students to important concepts and skills needed to complete their project, such as:

- Working with texts.

- Citing sources.

- Contextualizing ideas.

- Revising and reflecting.

- Presenting academic work to diverse audiences.

Because student projects provide the central focus of our courses, instructors should spend most class sessions working with students on their writing.

Below are examples of ways to promote student work and sample activities that instructors can use in their courses.

Ways to Feature Student Work

Most class sessions should provide students with time to write and work on projects. Students should also practice giving and receiving constructive feedback by engaging with their instructors and peers.

Here are some examples of how to feature student work during class:

- Circulate drafts in process or portions of drafts in any number of ways.

- Ask students to characterize, frame, or situate each other’s work.

- Build things together in a shared online space (e.g., a course bibliography document; an annotation or glossary of key terms; a HuskyCT blog or discussion thread exploring potential extensions of the texts).

- Have students post drafts as discussion threads and assign a peer review process for group members.

- Build time for peer review in and outside of class (through email or course management software).

- Help students build “affinity networks” or writing groups around similar projects.

- Feature a particular project from one student to help work through a problem or issue.

- Share reflective writing and process notes.

- Assign cover letters, informal presentations, formal presentations, or remediation projects (putting the larger project into a new context).

When students do individual or group work in class, block time afterward for the whole class to come together to reflect on the work they completed. To avoid having students simply list what they discussed or found, it may be useful to structure that time as informal presentations or to have groups upload their findings/work to a common digital workspace.

Examples of Class Activities

Below are sample in-class activities, organized by topic, that instructors can use in their classes. Instructors are welcome to use these activities to facilitate writing and group work and to meet the day’s specific learning outcomes.

Working With Difficult Texts

Unpacking difficult passages.

Prepare a handout with difficult passages from the text, or have students identify difficult passages in the reading. Assign students to different groups based on a particular passage. In groups, have students trace how a term or concept is used in a particular passage and in the text as a whole. They should pull specific quotes that help them back up their understanding. Groups should use the textual evidence as a means to begin “translating” the passages. Afterward, they should go back to the text and reflect on why the author(s) used a specific term or concept in the text.

Visually Mapping a Text

A variation of this activity is to have students map the key terms visually. Together in groups, students should map and link key terms used by the author. Maps might not (and perhaps should not) be linear — students are encouraged to see the many ways the terms seem to interact in the text. Afterward, groups can compare maps to add lines or connections that they may not have noticed previously.

Exploring the Uses of a Text

Current, past, or future contexts.

Depending on your course inquiry and assignments, you may want students to consider how class readings can apply to and work in relation to different contexts, especially in the beginning stages of a larger assignment. Your specific learning goals will help determine which context will make most sense for your class to explore.

Current Context : Choose a current issue or have students work together to find a current issue that relates to your course inquiry and the text. Choose yourself or have students select key terms or concepts from the reading to help them examine or analyze the issue. Students will need to conduct research on the issue in groups. Then, on their own, in writing, students should draw connections between the text and issue.

Past Context : Ask students to bring a laptop or tablet to class, or divide them into groups (at least one student in each group should have a laptop). Using their devices, students explore the socio historical context of the reading in order to consider how it might have affected the text’s rhetoric (or vice versa).

Future Context : Have students consider how the text might be useful for future conflicts, issues, or developments in society or academia. The future context may be best paired with either the current or past contexts to demonstrate the development of ideas or movements over time. Students should explore self- or group-generated questions through individual writing, then discuss or otherwise share their ideas.

What’s Missing?

In small groups, students brainstorm for situations or concepts that the reading doesn’t seem to account for and why or how that situation or concept might be important to include or discuss in the conversation. The class makes a list of these various missing pieces, and then students individually reflect on how these choices reflect the priorities and rhetorical strategies of the author. What do their choices reveal about their aims?

What Is This Text? Who Is This Author?

Any assigned text can be accompanied with a small research component designed to help students place the text in a larger context. If you assign a text by Judith Butler, for example, students could be assigned roles to establish this context. One set of students could research Butler the person; another set could say more about what her influential writings are (and what they seek to do); a third set of students could trace the reception and influence of these texts. Based on this research, have students reflect in writing on the significance of these contexts and what these findings demonstrate about academic writing and this specific conversation. Next, use the contexts explored as a jumping-off point for students to begin exploring their next assignment.

Information Literacy and Handling Sources

Citation trail.

One way to begin the conversation about Information Literacy (InfoLit) and how to use sources effectively is to ask students to explore how other writers use sources. Working with the texts used in class, invite students to choose, in groups, one of the works that the author has cited. Have students locate that source, read it (in its entirety if it’s short or just the relevant section if it’s long).

After reading the source, ask students to free write on the source’s main idea, what kind of source it is, and why the author used it. Then, in groups, have students discuss how the author of the class text used the source and how the source is contributing to the class text’s author’s main claims.

After facilitating a brief class discussion of the groups’ findings, have students reflect, individually in writing, on the different ways a writer can use sources and how such choices can inform their own writing.

InfoLit Through Terms, Search Engines, and Databases

As a class, have students brainstorm a research question that engages with the next essay prompt. Afterward, have students brainstorm the kind of sources that may be useful for exploring said question, the fields that may already discussing or provide insight on the topic (like specific news sources or subject specific databases). Then, for each kind of source or each discipline, have students brainstorm key terms and discuss why certain terms are more useful than others in certain searches. After the list has been made, have students determine where to look for this information. From this point, you can decide whether to proceed with the search as a class or to have students to break into groups to explore different terms, search engines, and databases.

You may want to engage your students in a conversation about research questions before this activity or in a prior class period. Students will likely not be sure how to craft meaningful research questions. Be sure that you build in moments for students to reflect in writing on what the activity means for their own research processes.

Documenting the Research Process

As a take-home assignment, have students take screenshots of their research process for a larger project (including pictures of the key terms they use, the search results, the articles they select, etc.) or record their research process. Students can either save the images on their computer or print them (whichever is more convenient). If they took a video, ask them to bring in their computer with the video. In class, have students map out the process—from where they began to where they ended. It may be best to do this on large sheets of paper, index cards, or construction paper. As they map out the process, have students make connections through a freewrite between the choices they made (e.g., how one term led to a new term, how they followed several hyperlinks and where that led them). Once they have finished their map/web and their freewrite, have students pair up and talk through their process and connections. In pairs, students should help each other identify gaps in their research and brainstorm new terms, websites, databases, etc., to explore. At the end, have students write out a research plan for the next portion of their assignment.

Annotated Bibliography

Have students bring an annotated bibliography and the original sources to class. It’s important to stress that this research often includes a lot of excess—simply choosing the first hit is often not the right match for a research project. Have students write about the choices they made in selecting their sources and reflect on how these sources contribute to their developing projects.

An alternative or add-on to this activity is to make students’ in-class work multimodal. With their annotated bibliographies, have students use either Prezi or construction paper and string to create a web that represents connections between sources. Students can address these questions: How do the sources talk to each other? How do they agree or disagree or qualify each other’s discussions? After students create their webs, have them reflect on the gaps that seem to exist in their web or identify the outlying sources that no longer work in their developing projects.

Depending on your course, you may want to make the annotated bibliography a collaborative project, where students contribute the sources they have found to a class archive that other students are encouraged to draw on in their writing projects. Google Docs (or a similar technology) can enable your class to create a “living” bibliography that each student can alter, add to, and improve throughout the semester.

Using Sources

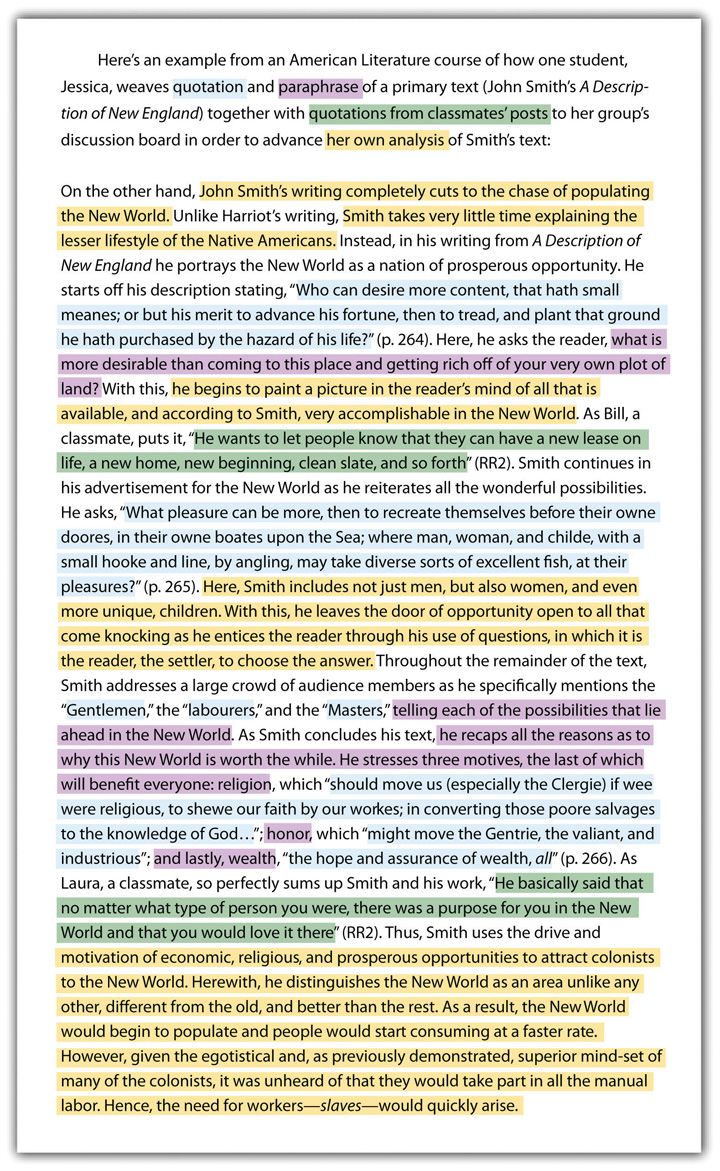

Working with other voices.

Have students highlight all the material borrowed or quoted from another source (including their own previous projects) in their essays in one color, and in a different color highlight all the places where they respond to or analyze those passages. Then ask them to evaluate their use of other voices—or trade papers and discuss with a partner. Are the passages adequately unpacked, explained, and analyzed? Is the reader left hanging? Are there more quotations than the students’ own words? How does the student build on and revise or drop things they wrote about in the previous assignment?

This activity could work well alongside a discussion of the difference between summary and analysis.

Outside View

Have students pass their essays around in groups. Each student should choose at least one quotation in their peer’s paper and answer the following questions: Do you know where the quote is from? Does the writer describe how or why the quote is useful for considering something interesting or troubling about their project? Is the quote integrated into the discussion of the paragraph? Afterward, students can return their papers to the original writer, and students can spend five to ten minutes revising their use of that quote.

Exploring Structure

Reverse outline.

Have students create a reverse outline of a reading, thinking about questions like: Where is the agenda, the method, and the evidence? Is the argument linear? Does the reading present a compelling argument or an interesting idea? Students can do this work individually, in groups, or together as a class. They can also identify what work each paragraph of a challenging section is doing in the author’s argument (beyond what each paragraph is saying). For instance, is a paragraph introducing a key term or idea? Illustrating a key point of evidence?

Be sure to give students time to reflect on what they have discovered through the reverse outline and how it can apply to their own writing. You may want to give them an in-class writing activity that asks them to take their own draft and model it after the essay and reflect on how the new structure influences the content and purpose of their draft.

Mapping the Text

Using the whiteboard, blank paper, or colored construction paper, have students, in groups, create a visual map of the text that they read for class. Encourage them to make design choices that reflect the author’s purpose in the text. Students can then discuss the choices the writer made in response to a specific audience or conversation.

Introduction Workshop

Project (or copy and distribute) a student’s introduction to the class and have students write what in the introduction is helpful for them as readers and what they might still need information on (for instance, if the required texts for the assignment haven’t been introduced). Have them restate the author’s project in their own words. Afterward, students should gather in groups to discuss various strategies for addressing potential issues that may have arisen, and then the whole class can discuss approaches to revision.

Also, before looking at student writing, you might have students consider introductions from the assigned readings, especially if you’re asking students to write in a similar genre. Discussing the readings can then serve as a jumping-off point for looking at student work.

Collaborative Revision

Revision can be one of the toughest aspects of writing for students to fully grasp and take advantage of. Extensively working with revising in class to demonstrate what effective revision can look like helps students to understand that revision is more than simply correcting grammar and word choice. At any stage in the drafting process, working on revision with the entire class can help students conceptualize how revising can be done effectively. Depending on your class and its needs, you may either want to pre-select students whose essays best exemplify an issue the majority of the class is grappling with or have students volunteer their work themselves. If you pre-select students, you’re most likely going to gear your discussion toward a particular issue that the sample drafts exemplify. Self-volunteered drafts may engage several different issues. As students look at the samples, have them think about how the project might be supported with texts from the class, how it contributes new knowledge, and how the writer might move forward in the essay. It may be helpful to have the student identify a specific location where they’re having trouble. As you go about your discussion, you will be modeling ways of responding to texts in peer review. Be sure to make that explicit to the students.

Topic-Specific Workshop

After reading a round of student drafts, you may find that there are common challenges that students are working through. These common issues can be the basis of in-class workshops to help students navigate these particular challenges. Below are two examples, but there are many other writing challenges to work with in class.

Transitions : Some students may be listing their major points in the body of the paper rather than developing a project; consequently, you might call on a student volunteer, or project two anonymous paragraphs from a student paper, to examine how one paragraph moves to the next. Ask students how the two paragraphs might be related and, in groups, have them rewrite the ends and beginnings of the two paragraphs so as to make explicit how the ideas in the paragraphs build on and relate to one another. Have each group present their revisions and discuss their strategies.

In-Text Citations/Using Sources : Using sources effectively in a text is a challenge for many students. Students must not only cite information correctly, but also integrate the quote into their own language and consider how the quote is working with their argument. You may first want to examine an assigned text and, as a whole class or in smaller groups, analyze the author’s use of quotations and other outside sources. Try to push students to decipher the different ways that sources can be used to support a point (using a text like Joseph Harris’s or FYW’s webpage Why Quote? can give students a vocabulary or starting point for discussion). From here, get a volunteer from class (or choose a student ahead of time) and project or distribute a paragraph from their essay. As a class, discuss how the writer could revise their quotations and citations. Then, have students turn to their own texts and work on the way that they use sources in their projects.

Paired Read-Alouds

Pair students and have them read each other’s paper aloud. Paired read-alouds can be used at different points in the drafting process for different purposes. With a rough draft, you can ask: Does the new set of eyes see more places to push the project further? Are there places where the evidence is unclear? Where might more textual support be needed? At a more polished stage, read-alouds can highlight fluency, sentence structure, and grammatical errors.

Useful for working through difficult readings, reverse outlines are also beneficial to students during drafting. Have students reverse outline their own papers, identifying the individual aims and rhetorical moves of each paragraph, and then have them reflect on what they have noticed. Or have students swap papers and reverse outline their peers’ papers, and then return the papers to their original authors. The students could also reflect on what they notice from their peers’ rendering of their projects. In any case, at the end of the activity, give students time to write about and reflect on what the reverse outline has revealed to them about their work and how they’ll use it to move forward with their draft.

For a more multimodal approach, students can create their reverse outlines using Prezi, construction paper, or the like.

Creating Revision Plans from Feedback

Students don’t always know what to do with comments after they receive your feedback or feedback from peers, so it might be useful to build in time for them to prioritize and plan. Have students look at a sample paper with comments first; then engage them in a discussion of how to prioritize and use feedback. Afterward, give them the opportunity to reflect on their own feedback and write a revision plan.

If you’re doing a portfolio in your course or wish for students to document their writing process, you may want to collect and respond to their revision plans or stress that they keep track of these documents.

Writing About Their Own Writing

At any stage in the writing process, ask your students to reflect on the writing that they have done so far, using the following prompts for in-class, informal, ungraded writing: What personal investment do you have in this issue? Why does your argument matter? What counter-interpretations might work against your emerging claims? What are you struggling with most as you approach the draft? How does the way you are writing aid (or complicate) your answers to these first questions? If you choose to, you can discuss these writings as a class or in small groups.

Representing the Writing Process

Have students use markers, pencils, Play-Doh, pipe cleaners—check out the art cart in the First-Year Writing Program office—to draw, make, or sculpt a representation of a certain part of the writing process (perhaps right after students have completed an assignment). Afterward, give them a few minutes to write about their representation. In small groups, students can share their various processes. Doing so allows students to unpack what approaches and strategies worked—it also gives them a chance to see how others approached a similar task.

Creative Synthesis

Near the end of the semester, have students read over their major essays and extract one or two “keywords” or important themes from each. (For instance, if a student wrote an essay about capitalist values in Maus, one keyword from that essay might be “capitalism,” or “homo economicus.”) In a new document, have students write their lists of keywords at the top of the page. They should then write a brief story in class that touches on each of these themes.

It’s not necessary to use the word itself—so, if one keyword is “masculinity,” the student doesn’t actually have to say “masculinity” somewhere in the story, so long as the idea is present. For example, if a student’s keywords were “capitalism,” “dystopia,” and “masculinity,” the student might write a story about a young man in a dystopian society who, in order to prove his masculinity and support his paralyzed father, has to engage in gladiatorial combat. Maybe this gladiatorial combat is televised, with pauses in the fighting for advertisements for men’s deodorant, etc.

“One-Minute Papers”

At the end of a class session, you can ask your students to write short responses to questions like: What is the one big idea or new insight you’ve taken from today’s class? What is still confusing for you? This will help students practice metacognition by allowing them to consider what in their thinking has changed and what remains a challenge for them moving forward.

Writing Across Technology

Key terms and infographics.

Students can mine a text for key terms and concepts in groups. After discussing the terms and concepts in a larger group, the small groups can then use Piktochart or Canva to create an infographic to help explain how a specific term is being used in a text. This exercise can be framed with the following question: Assuming that your audience is future students in this class, how can you visually explain how the author is using [a particular key term]?

Critical and Creative Captioning

Practice using captioning software for videos, such as with YouTube or Amara. Students can consider how captioning functions rhetorically and depends on concepts of audience, context, and purpose. This activity can be used as students work on their own videos (such as a Concept in 60 video), or students can work in groups to caption sections of a short video in class. (Movie trailers often work pretty well here.)

Cover Design

Ask students to use the design concepts from The Academic Writer to analyze the design of a visual text—a book cover works well. After evaluating the effectiveness of the design choices in the text, let students work in groups to propose alternative covers. This can be done on computers (using software like Word, PowerPoint, GIMP, or Illustrator) or with paper and markers. Students can then present their designs (explaining why these designs are effective) and vote on the elements they’d like to include in a reprint of the text.

Electronic Discussion

If all students have access to bring-your-own personal technology (laptops, smartphones, or other mobile devices with internet access), discussions can become hybrid spaces with the use of online platforms. Allowing students to participate in discussions through technology can help second-language writers, students who are shy, and students with disabilities—and can, in fact, help all students contribute in more thoughtful ways, because writing an answer allows for more time to think. The platform being used can be projected, giving everyone easy access to responses. The instructor can choose to read these responses aloud to focus and direct the discussion or ask students to take a couple of moments to quietly compose responses to spark new avenues of inquiry.

Screencasting the Writing Process

Have students use a program like Kaltura or PowerPoint to screencast their writing as they work through a draft at home. Once they have turned in the essay, have students bring the video to class to watch individually. As they watch their videos, have them describe what’s happening and take notes on what they’re noticing about how they write. Afterward, have them discuss in groups what they noticed. After the discussion, have students review their notes and reflect on what went well and what could be worked on as they proceed in their next assignment.

Recorded Elevator Pitches

Sometimes students work through ideas best when they talk about them aloud. When they’re early in the writing or research process, have them pitch their developing ideas to each other in a minute or less and use their smartphones to record their pitch. At the end of the pitch, peers should provide feedback. As students move on to the next partner, they should incorporate the previous partner’s feedback (or make revisions based on their own observations). At the end, have students listen to their pitches and reflect on what changed from one pitch to the next.

3.9 Writing

Where Are You Now?

Assess your present knowledge and attitudes.

Where Do You Want to Go?

Think about how you answered the questions above. Be honest with yourself. On a scale of 1 to 10, how would you rate your level of confidence and your attitude about writing?

In the following list, circle the three areas you see as most important to your improvement as a writer:

- Using time effectively

- Using sources effectively and appropriately

- Understanding instructors’ expectations

- Citing sources in the proper form

- Being productive with brainstorming and other prewriting activities

- Sharing my work in drafts and accepting feedback

- Organizing ideas clearly and transitioning between ideas

- Understanding the difference between proofreading and revision

- Developing ideas fully

- Drafting and redrafting in response to criticism

- Using correct sentence mechanics (grammar, punctuation, etc.)

- Using Web sites, reference books, and campus resources

- Developing an academic “voice”

Think about the three things you chose: Why did you choose them? Have you had certain kinds of writing difficulties in the past? Consider what you hope to learn here.

__________________________________________________________________

How to Get There

Here’s what we’ll work on in this chapter:

- Understanding why writing is vital to your success in college

- Learning how writing in college differs from writing in high school

- Understanding how a writing class differs (and doesn’t differ) from other classes with assigned writing

- Knowing what instructors in college expect of you as a writer

- Knowing what different types of assignments are most common in college

- Using the writing process to achieve your best work

- Identifying common errors and become a better editor of your own work

- Responding to an instructor’s feedback on your work in progress and on your final paper

- Using sources appropriately and avoiding plagiarism

- Writing an in-class essay, for an online course, and in group writing projects

The Importance of Writing

Writing is one of the key skills all successful students must acquire. You might think your main job in a history class is to learn facts about events. So you read your textbook and take notes on important dates, names, causes, and so on. But however important these details are to your instructor, they don’t mean much if you can’t explain them in writing. Even if you remember the facts well and believe you understand their meaning completely, if you can’t express your understanding by communicating it—in college that almost always means in writing—then as far as others may know, you don’t have an understanding at all. In a way, then, learning history is learning to write about history. Think about it. Great historians don’t just know facts and ideas. Great historians use their writing skills to share their facts and ideas effectively with others.

History is just one example. Consider a lab course—a class that’s as much hands-on as any in college. At some point, you’ll be asked to write a step-by-step report on an experiment you have run. The quality of your lab work will not show if you cannot describe that work and state your findings well in writing. Even though many instructors in courses other than English classes may not comment directly on your writing, their judgment of your understanding will still be mostly based on what you write. This means that in all your courses, not just your English courses, instructors expect good writing.

In college courses, writing is how ideas are exchanged, from scholars to students and from students back to scholars. While the grade in some courses may be based mostly on class participation, oral reports, or multiple-choice exams, writing is by far the single most important form of instruction and assessment. Instructors expect you to learn by writing, and they will grade you on the basis of your writing.

If you find that a scary thought, take heart! By paying attention to your writing and learning and practicing basic skills, even those who never thought of themselves as good writers can succeed in college writing. As with other college skills, getting off to a good start is mostly a matter of being motivated and developing a confident attitude that you can do it.

As a form of communication, writing is different from oral communication in several ways. Instructors expect writing to be well thought out and organized and to explain ideas fully. In oral communication, the listener can ask for clarification, but in written work, everything must be clear within the writing itself. Guidelines for oral presentations are provided in Chapter 7 “Interacting with Instructors and Classes” .

Note: Most college students take a writing course their first year, often in the first term. Even if you are not required to take such a class, it’s a good idea for all students to learn more about college writing. This short chapter cannot cover even a small amount of what you will learn in a full writing course. Our goal here is to introduce some important writing principles, if you’re not yet familiar with them, or to remind you of things you may have already learned in a writing course. As with all advice, always pay the most attention to what your instructor says—the terms of a specific assignment may overrule a tip given here!

Learning Objectives

- Define “academic writing.”

- Identify key differences between writing in college and writing in high school or on the job.

- Identify different types of papers that are commonly assigned.

- Describe what instructors expect from student writing.

Academic writing refers to writing produced in a college environment. Often this is writing that responds to other writing—to the ideas or controversies that you’ll read about. While this definition sounds simple, academic writing may be very different from other types of writing you have done in the past. Often college students begin to understand what academic writing really means only after they receive negative feedback on their work. To become a strong writer in college, you need to achieve a clear sense of two things:

- The academic environment

- The kinds of writing you’ll be doing in that environment

Differences between High School and College Writing

Students who struggle with writing in college often conclude that their high school teachers were too easy or that their college instructors are too hard. In most cases, neither explanation is fully accurate or fair. A student having difficulty with college writing usually just hasn’t yet made the transition from high school writing to college writing. That shouldn’t be surprising, for many beginning college students do not even know that there is a transition to be made.

In high school, most students think of writing as the subject of English classes. Few teachers in other courses give much feedback on student writing; many do not even assign writing. This says more about high school than about the quality of teachers or about writing itself. High school teachers typically teach five courses a day and often more than 150 students. Those students often have a very wide range of backgrounds and skill levels.

Thus many high school English instructors focus on specific, limited goals. For example, they may teach the “five paragraph essay” as the right way to organize a paper because they want to give every student some idea of an essay’s basic structure. They may give assignments on stories and poems because their own college background involved literature and literary analysis. In classes other than English, many high school teachers must focus on an established body of information and may judge students using tests that measure only how much of this information they acquire. Often writing itself is not directly addressed in such classes.

This does not mean that students don’t learn a great deal in high school, but it’s easy to see why some students think that writing is important only in English classes. Many students also believe an academic essay must be five paragraphs long or that “school writing” is usually literary analysis.

Think about how college differs from high school. In many colleges, the instructors teach fewer classes and have fewer students. In addition, while college students have highly diverse backgrounds, the skills of college students are less variable than in an average high school class. In addition, college instructors are specialists in the fields they teach, as you recall from Chapter 7 “Interacting with Instructors and Classes” . College instructors may design their courses in unique ways, and they may teach about specialized subjects. For all of these reasons, college instructors are much more likely than high school teachers to

- assign writing,

- respond in detail to student writing,

- ask questions that cannot be dealt with easily in a fixed form like a five-paragraph essay.

Your transition to college writing could be even more dramatic. The kind of writing you have done in the past may not translate at all into the kind of writing required in college. For example, you may at first struggle with having to write about very different kinds of topics, using different approaches. You may have learned only one kind of writing genre (a kind of approach or organization) and now find you need to master other types of writing as well.

What Kinds of Papers Are Commonly Assigned in College Classes?

Think about the topic “gender roles”—referring to expectations about differences in how men and women act. You might study gender roles in an anthropology class, a film class, or a psychology class. The topic itself may overlap from one class to another, but you would not write about this subject in the same way in these different classes. For example, in an anthropology class, you might be asked to describe how men and women of a particular culture divide important duties. In a film class, you may be asked to analyze how a scene portrays gender roles enacted by the film’s characters. In a psychology course, you might be asked to summarize the results of an experiment involving gender roles or compare and contrast the findings of two related research projects.

It would be simplistic to say that there are three, or four, or ten, or any number of types of academic writing that have unique characteristics, shapes, and styles. Every assignment in every course is unique in some ways, so don’t think of writing as a fixed form you need to learn. On the other hand, there are certain writing approaches that do involve different kinds of writing. An approach is the way you go about meeting the writing goals for the assignment. The approach is usually signaled by the words instructors use in their assignments.

When you first get a writing assignment, pay attention first to keywords for how to approach the writing. These will also suggest how you may structure and develop your paper. Look for terms like these in the assignment:

- Summarize. To restate in your own words the main point or points of another’s work.

- Define. To describe, explore, or characterize a keyword, idea, or phenomenon.

- Classify. To group individual items by their shared characteristics, separate from other groups of items.

- Compare/contrast. To explore significant likenesses and differences between two or more subjects.

- Analyze. To break something, a phenomenon, or an idea into its parts and explain how those parts fit or work together.

- Argue. To state a claim and support it with reasons and evidence.

- Synthesize. To pull together varied pieces or ideas from two or more sources.

Note how this list is similar to the words used in examination questions that involve writing. (See Table 6.1 “Words to Watch for in Essay Questions” in Chapter 6 “Preparing for and Taking Tests” , Section 6.4 “The Secrets of the Q and A’s” .) This overlap is not a coincidence—essay exams are an abbreviated form of academic writing such as a class paper.

Sometimes the keywords listed don’t actually appear in the written assignment, but they are usually implied by the questions given in the assignment. “What,” “why,” and “how” are common question words that require a certain kind of response. Look back at the keywords listed and think about which approaches relate to “what,” “why,” and “how” questions.

- “What” questions usually prompt the writing of summaries, definitions, classifications, and sometimes compare-and-contrast essays. For example, “ What does Jones see as the main elements of Huey Long’s populist appeal?” or “ What happened when you heated the chemical solution?”

- “Why” and “how” questions typically prompt analysis, argument, and synthesis essays. For example, “ Why did Huey Long’s brand of populism gain force so quickly?” or “ Why did the solution respond the way it did to heat?”

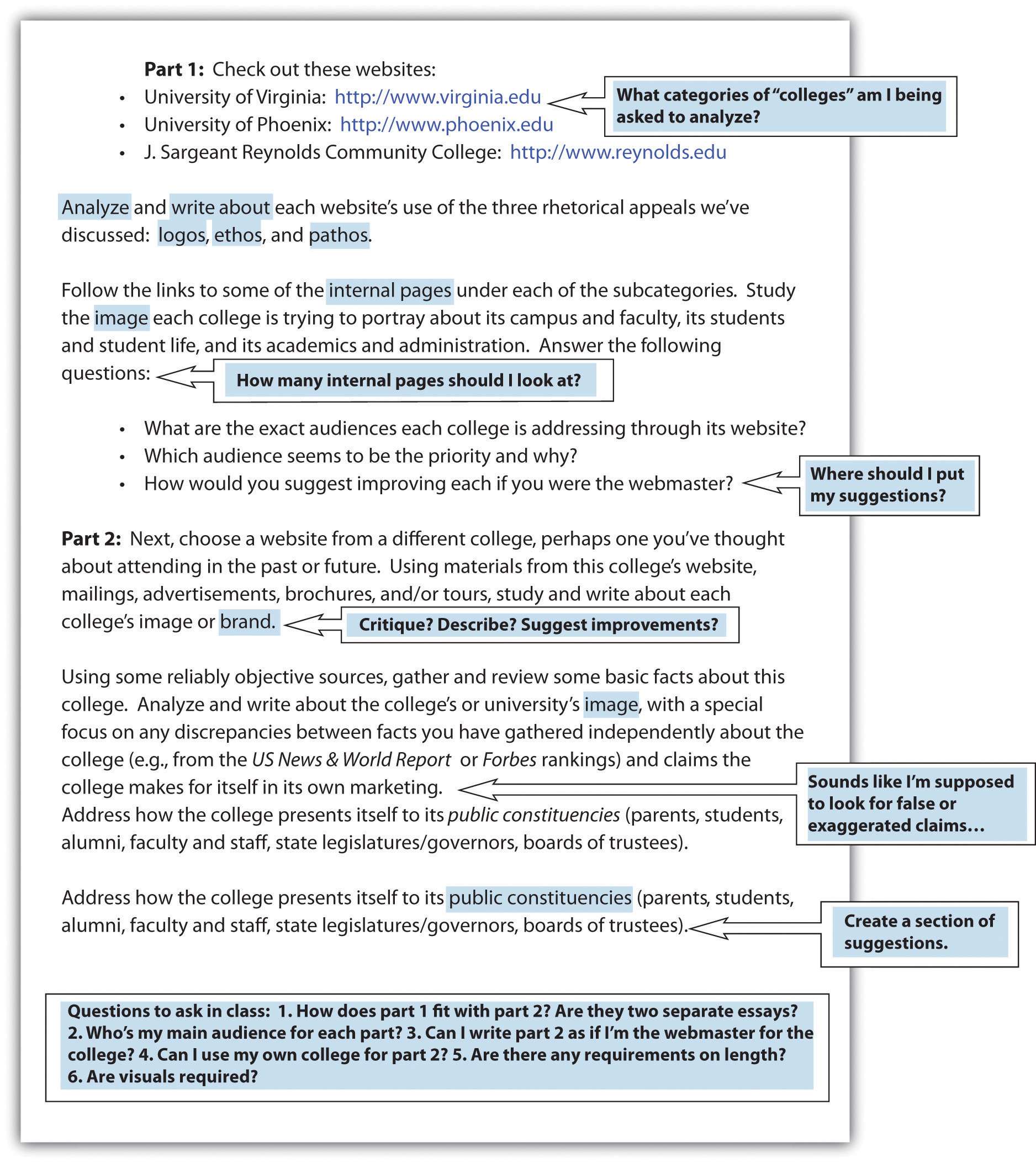

Successful academic writing starts with recognizing what the instructor is requesting, or what you are required to do. So pay close attention to the assignment. Sometimes the essential information about an assignment is conveyed through class discussions, however, so be sure to listen for the keywords that will help you understand what the instructor expects. If you feel the assignment does not give you a sense of direction, seek clarification. Ask questions that will lead to helpful answers. For example, here’s a short and very vague assignment:

Discuss the perspectives on religion of Rousseau, Bentham, and Marx. Papers should be four to five pages in length.

Faced with an assignment like this, you could ask about the scope (or focus) of the assignment:

- Which of the assigned readings should I concentrate on?

- Should I read other works by these authors that haven’t been assigned in class?

- Should I do research to see what scholars think about the way these philosophers view religion?

- Do you want me to pay equal attention to each of the three philosophers?

You can also ask about the approach the instructor would like you to take. You can use the keywords the instructor may not have used in the assignment:

- Should I just summarize the positions of these three thinkers, or should I compare and contrast their views?

- Do you want me to argue a specific point about the way these philosophers approach religion?

- Would it be OK if I classified the ways these philosophers think about religion?

Never just complain about a vague assignment. It is fine to ask questions like these. Such questions will likely engage your instructor in a productive discussion with you.

Key Takeaways

- Writing is crucial to college success because it is the single most important means of evaluation.

- Writing in college is not limited to the kinds of assignments commonly required in high school English classes.

- Writers in college must pay close attention to the terms of an assignment.

- If an assignment is not clear, seek clarification from the instructor.

Checkpoint Exercises

What kind(s) of writing have you practiced most in your recent past?

____________________________________________________________________

Name two things that make academic writing in college different from writing in high school.

Explain how the word “what” asks for a different kind of paper than the word “why.”

- Describe how a writing class can help you succeed in other courses.

- Define what instructors expect of a college student’s writing.

- Explain why learning to write is an ongoing task.

- Understand writing as a process.

- Develop productive prewriting and revision strategies.

- Distinguish between revision and editing.

- Access and use available resources.

- Understand how to integrate research in your writing.

- Define plagiarism.

Students are usually required to take at least one writing course in their first year of college. That course is often crucial for your success in college. But a writing course can help you only if you recognize how it connects to your other work in college. If you approach your writing course merely as another hoop you need to jump through, you may miss out on the main message: writing is vital to your academic success at every step toward your degree.

What Do Instructors Really Want?

Some instructors may say they have no particular expectations for student papers. This is partly true. College instructors do not usually have one right answer in mind or one right approach to take when they assign a paper topic. They expect you to engage in critical thinking and decide for yourself what you are saying and how to say it. But in other ways college instructors do have expectations, and it is important to understand them. Some expectations involve mastering the material or demonstrating critical thinking. Other expectations involve specific writing skills. Most college instructors expect certain characteristics in student writing. Here are general principles you should follow when writing essays or student “papers.” (Some may not be appropriate for specific formats such as lab reports.)

Title the paper to identify your topic. This may sound obvious, but it needs to be said. Some students think of a paper as an exercise and write something like “Assignment 2: History 101” on the title page. Such a title gives no idea about how you are approaching the assignment or your topic. Your title should prepare your reader for what your paper is about or what you will argue. (With essays, always consider your reader as an educated adult interested in your topic. An essay is not a letter written to your instructor.) Compare the following:

Incorrect: Assignment 2: History 101

Correct: Why the New World Was Not “New”

It is obvious which of these two titles begins to prepare your reader for the paper itself. Similarly, don’t make your title the same as the title of a work you are writing about. Instead, be sure your title signals an aspect of the work you are focusing on:

Incorrect: Catcher in the Rye

Correct: Family Relationships in Catcher in the Rye

Address the terms of the assignment. Again, pay particular attention to words in the assignment that signal a preferred approach. If the instructor asks you to “argue” a point, be sure to make a statement that actually expresses your idea about the topic. Then follow that statement with your reasons and evidence in support of the statement. Look for any signals that will help you focus or limit your approach. Since no paper can cover everything about a complex topic, what is it that your instructor wants you to cover?

Finally, pay attention to the little things. For example, if the assignment specifies “5 to 6 pages in length,” write a five- to six-page paper. Don’t try to stretch a short paper longer by enlarging the font (12 points is standard) or making your margins bigger than the normal one inch (or as specified by the instructor). If the assignment is due at the beginning of class on Monday, have it ready then or before. Do not assume you can negotiate a revised due date.

In your introduction, define your topic and establish your approach or sense of purpose. Think of your introduction as an extension of your title. Instructors (like all readers) appreciate feeling oriented by a clear opening. They appreciate knowing that you have a purpose for your topic—that you have a reason for writing the paper. If they feel they’ve just been dropped into the middle of a paper, they may miss important ideas. They may not make connections you want them to make.

Build from a thesis or a clearly stated sense of purpose. Many college assignments require you to make some form of an argument. To do that, you generally start with a statement that needs to be supported and build from there. Your thesis is that statement; it is a guiding assertion for the paper. Be clear in your own mind of the difference between your topic and your thesis. The topic is what your paper is about; the thesis is what you argue about the topic. Some assignments do not require an explicit argument and thesis, but even then you should make clear at the beginning your main emphasis, your purpose, or your most important idea.

Develop ideas patiently. You might, like many students, worry about boring your reader with too much detail or information. But college instructors will not be bored by carefully explained ideas, well-selected examples, and relevant details. College instructors, after all, are professionally devoted to their subjects. If your sociology instructor asks you to write about youth crime in rural areas, you can be sure he or she is interested in that subject.

In some respects, how you develop your paper is the most crucial part of the assignment. You’ll win the day with detailed explanations and well-presented evidence—not big generalizations. For example, anyone can write something broad (and bland) like “The constitutional separation of church and state is a good thing for America”—but what do you really mean by that? Specifically? Are you talking about banning “Christmas trees” from government property—or calling them “holiday trees” instead? Are you arguing for eliminating the tax-free status of religious organizations? Are you saying that American laws should never be based on moral values? The more you really dig into your topic—the more time you spend thinking about the specifics of what you really want to argue and developing specific examples and reasons for your argument—the more developed your paper will be. It will also be much more interesting to your instructor as the reader. Remember, those grand generalizations we all like to make (“America is the land of the free”) actually don’t mean much at all until we develop the idea in specifics. (Free to do what? No laws? No restrictions like speed limits? Freedom not to pay any taxes? Free food for all? What do you really mean when you say American is the land of the “free”?)

Integrate—do not just “plug in”—quotations, graphs, and illustrations . As you outline or sketch out your material, you will think things like “this quotation can go here” or “I can put that graph there.” Remember that a quotation, graph, or illustration does not make a point for you. You make the point first and then use such material to help back it up. Using a quotation, a graph, or an illustration involves more than simply sticking it into the paper. Always lead into such material. Make sure the reader understands why you are using it and how it fits in at that place in your presentation.

Build clear transitions at the beginning of every paragraph to link from one idea to another. A good paper is more than a list of good ideas. It should also show how the ideas fit together. As you write the first sentence of any paragraph, have a clear sense of what the prior paragraph was about. Think of the first sentence in any paragraph as a kind of bridge for the reader from what came before.

Document your sources appropriately. If your paper involves research of any kind, indicate clearly the use you make of outside sources. If you have used those sources well, there is no reason to hide them. Careful research and the thoughtful application of the ideas and evidence of others is part of what college instructors value. (We address specifics about documentation later on.)

Carefully edit your paper. College instructors assume you will take the time to edit and proofread your essay. A misspelled word or an incomplete sentence may signal a lack of concern on your part. It may not seem fair to make a harsh judgment about your seriousness based on little errors, but in all writing, impressions count. Since it is often hard to find small errors in our own writing, always print out a draft well before you need to turn it in. Ask a classmate or a friend to review it and mark any word or sentence that seems “off” in any way. Although you should certainly use a spell-checker, don’t assume it can catch everything. A spell-checker cannot tell if you have the right word. For example, these words are commonly misused or mixed up:

- there, their, they’re

- effect, affect

- complement, compliment

Your spell-checker can’t help with these. You also can’t trust what a “grammar checker” (like the one built into the Microsoft Word spell-checker) tells you—computers are still a long way from being able to fix your writing for you!

Turn in a clean hard copy. Some instructors accept or even prefer digital papers, but do not assume this. Most instructors want a paper copy and most definitely do not want to do the printing themselves. Present your paper in a professional (and unfussy) way, using a staple or paper clip on the left top to hold the pages together (unless the instructor specifies otherwise). Never bring your paper to class and ask the instructor, “Do you have a stapler?” Similarly, do not put your paper in a plastic binder unless the instructor asks you to.

The Writing Process

Writing instructors distinguish between process and product . The expectations described here all involve the “product” you turn in on the due date. Although you should keep in mind what your product will look like, writing is more involved with how you get to that goal. “Process” concerns how you work to actually write a paper. What do you actually do to get started? How do you organize your ideas? Why do you make changes along the way as you write? Thinking of writing as a process is important because writing is actually a complex activity. Even professional writers rarely sit down at a keyboard and write out an article beginning to end without stopping along the way to revise portions they have drafted, to move ideas around, or to revise their opening and thesis. Professionals and students alike often say they only realized what they wanted to say after they started to write. This is why many instructors see writing as a way to learn. Many writing instructors ask you to submit a draft for review before submitting a final paper. To roughly paraphrase a famous poem, you learn by doing what you have to do.

How Can I Make the Process Work for Me?

No single set of steps automatically works best for everyone when writing a paper, but writers have found a number of steps helpful. Your job is to try out ways that your instructor suggests and discover what works for you. As you’ll see in the following list, the process starts before you write a word. Generally there are three stages in the writing process:

- Preparing before drafting (thinking, brainstorming, planning, reading, researching, outlining, sketching, etc.)—sometimes called “prewriting” (although you are usually still writing something at this stage, even if only jotting notes)

- Writing the draft

- Revising and editing

Involved in these three stages are a number of separate tasks—and that’s where you need to figure out what works best for you.

Because writing is hard, procrastination is easy. Don’t let yourself put off the task. Use the time management strategies described in Chapter 2 “Staying Motivated, Organized, and On Track” . One good approach is to schedule shorter time periods over a series of days—rather than trying to sit down for one long period to accomplish a lot. (Even professional writers can write only so much at a time.) Try the following strategies to get started:

- Discuss what you read, see, and hear. Talking with others about your ideas is a good way to begin to achieve clarity. Listening to others helps you understand what points need special attention. Discussion also helps writers realize that their own ideas are often best presented in relation to the ideas of others.

- Use e-mail to carry on discussions in writing. An e-mail exchange with a classmate or your instructor might be the first step toward putting words on a page.

- Brainstorm. Jot down your thoughts as they come to mind. Just write away, not worrying at first about how those ideas fit together. (This is often called “free writing.”) Once you’ve written a number of notes or short blocks of sentences, pause and read them over. Take note of anything that stands out as particularly important to you. Also consider how parts of your scattered notes might eventually fit together or how they might end up in a sequence in the paper you’ll get to later on.

- Keep a journal in which you respond to your assigned readings. Set aside twenty minutes or so three times a week to summarize important texts. Go beyond just summarizing: talk back about what you have been reading or apply the reading to your own experience. See Chapter 5 “Reading to Learn” for more tips on taking notes about your readings.

- Ask and respond in writing to “what,” “why,” and “how” questions . Good questions prompt productive writing sessions. Again, “what” questions will lead to descriptions or summaries; “why” and “how” questions will lead you to analyses and explanations. Construct your own “what,” “why,” and “how” questions and then start answering them.

- In your notes, respond directly to what others have written or said about a topic you are interested in. Most academic writing engages the ideas of others. Academic writing carries on a conversation among people interested in the field. By thinking of how your ideas relate to those of others, you can clarify your sense of purpose and sometimes even discover a way to write your introduction.

All of these steps and actions so far are “prewriting” actions. Again, almost no one just sits down and starts writing a paper at the beginning—at least not a successful paper! These prewriting steps help you get going in the right direction. Once you are ready to start drafting your essay, keep moving forward in these ways:

- Write a short statement of intent or outline your paper before your first draft. Such a road map can be very useful, but don’t assume you’ll always be able to stick with your first plan. Once you start writing, you may discover a need for changes in the substance or order of things in your essay. Such discoveries don’t mean you made “mistakes” in the outline. They simply mean you are involved in a process that cannot be completely scripted in advance.

- Write down on a card or a separate sheet of paper what you see as your paper’s main point or thesis. As you draft your essay, look back at that thesis statement. Are you staying on track? Or are you discovering that you need to change your main point or thesis? From time to time, check the development of your ideas against what you started out saying you would do. Revise as needed and move forward.

- Reverse outline your paper. Outlining is usually a beginning point, a road map for the task ahead. But many writers find that outlining what they have already written in a draft helps them see more clearly how their ideas fit or do not fit together. Outlining in this way can reveal trouble spots that are harder to see in a full draft. Once you see those trouble spots, effective revision becomes possible.

- Don’t obsess over detail when writing the draft. Remember, you have time for revising and editing later on. Now is the time to test out the plan you’ve made and see how your ideas develop. The last things in the world you want to worry about now are the little things like grammar and punctuation—spend your time developing your material, knowing you can fix the details later.

- Read your draft aloud. Hearing your own writing often helps you see it more plainly. A gap or an inconsistency in an argument that you simply do not see in a silent reading becomes evident when you give voice to the text. You may also catch sentence-level mistakes by reading your paper aloud.

What’s the Difference between Revising and Editing?

Some students think of a draft as something that they need only “correct” after writing. They assume their first effort to do the assignment resulted in something that needs only surface attention. This is a big mistake. A good writer does not write fast. Good writers know that the task is complicated enough to demand some patience. “Revision” rather than “correction” suggests seeing again in a new light generated by all the thought that went into the first draft. Revising a draft usually involves significant changes including the following:

- Making organizational changes like the reordering of paragraphs (don’t forget that new transitions will be needed when you move paragraphs)

- Clarifying the thesis or adjustments between the thesis and supporting points that follow

- Cutting material that is unnecessary or irrelevant

- Adding new points to strengthen or clarify the presentation

Editing and proofreading are the last steps following revision. Correcting a sentence early on may not be the best use of your time since you may cut the sentence entirely. Editing and proofreading are focused, late-stage activities for style and correctness. They are important final parts of the writing process, but they should not be confused with revision itself. Editing and proofreading a draft involve these steps:

- Careful spell-checking. This includes checking the spelling of names.

- Attention to sentence-level issues. Be especially attentive to sentence boundaries, subject-verb agreement, punctuation, and pronoun referents. You can also attend at this stage to matters of style.

Remember to get started on a writing assignment early so that you complete the first draft well before the due date, allowing you needed time for genuine revision and careful editing.

What If I Need Help with Writing?

Writing is hard work. Most colleges provide resources that can help you from the early stages of an assignment through to the completion of an essay. Your first resource may be a writing class. Most students are encouraged or required to enroll in a writing class in their first term, and it’s a good idea for everyone. Use everything you learn there about drafting and revising in all your courses.

Tutoring services. Most colleges have a tutoring service that focuses primarily on student writing. Look up and visit your tutoring center early in the term to learn what service is offered. Specifically check on the following:

- Do you have to register in advance for help? If so, is there a registration deadline?

- Are appointments required or encouraged, or can you just drop in?

- Are regular standing appointments with the same tutor encouraged?

- Are a limited number of sessions allowed per term?

- Are small group workshops offered in addition to individual appointments?

- Are specialists available for help with students who have learned English as a second language?

Three points about writing tutors are crucial:

- Writing tutors are there for all student writers—not just for weak or inexperienced writers. Writing in college is supposed to be a challenge. Some students make writing even harder by thinking that good writers work in isolation. But writing is a social act. A good paper should engage others.

- Tutors are not there for you to “correct” sentence-level problems or polish your finished draft. They will help you identify and understand sentence-level problems so that you can achieve greater control over your writing. But their more important goals often are to address larger concerns like the paper’s organization, the fullness of its development, and the clarity of its argument. So don’t make your first appointment the day before a paper is due, because you may need more time to revise after discussing the paper with a tutor.

- Tutors cannot help you if you do not do your part. Tutors respond only to what you say and write; they cannot enable you to magically jump past the thinking an assignment requires. So do some thinking about the assignment before your meeting and be sure to bring relevant materials with you. For example, bring the paper assignment. You might also bring the course syllabus and perhaps even the required textbook. Most importantly, bring any writing you’ve done in response to the assignment (an outline, a thesis statement, a draft, an introductory paragraph). If you want to get help from a tutor, you need to give the tutor something to work with.

Teaching assistants and instructors. In a large class, you may have both a course instructor and a teaching assistant (TA). Seek help from either or both as you draft your essay. Some instructors offer only limited help. They may not, for example, have time to respond to a complete draft of your essay. But even a brief response to a drafted introduction or to a question can be tremendously valuable. Remember that most TAs and instructors want to help you learn. View them along with tutors as part of a team that works with you to achieve academic success. Remember the tips you learned in Chapter 7 “Interacting with Instructors and Classes” for interacting well with your instructors.

Writing Web sites and writing handbooks. Many writing Web sites and handbooks can help you along every step of the way, especially in the late stages of your work. You’ll find lessons on style as well as information about language conventions and “correctness.” Not only should you use the handbook your composition instructor assigns in a writing class, but you should not sell that book back at the end of the term. You will need it again for future writing. For more help, become familiar with a good Web site for student writers. There are many, but one we recommend is maintained by the Dartmouth College Writing Center at http://www.dartmouth.edu/~writing/materials/student/index.html .

Plagiarism—and How to Avoid It

Plagiarism is the unacknowledged use of material from a source. At the most obvious level, plagiarism involves using someone else’s words and ideas as if they were your own. There’s not much to say about copying another person’s work: it’s cheating, pure and simple. But plagiarism is not always so simple. Notice that our definition of plagiarism involves “words and ideas.” Let’s break that down a little further.

Words. Copying the words of another is clearly wrong. If you use another’s words, those words must be in quotation marks, and you must tell your reader where those words came from. But it is not enough to make a few surface changes in wording. You can’t just change some words and call the material yours; close, extended paraphrase is not acceptable. For example, compare the two passages that follow. The first comes from Murder Most Foul , a book by Karen Halttunen on changing ideas about murder in nineteenth-century America; the second is a close paraphrase of the same passage:

The new murder narratives were overwhelmingly secular works, written by a diverse array of printers, hack writers, sentimental poets, lawyers, and even murderers themselves, who were displacing the clergy as the dominant interpreters of the crime. The murder stories that were developing were almost always secular works that were written by many different sorts of people. Printers, hack writers, poets, attorneys, and sometimes even the criminals themselves were writing murder stories. They were the new interpreters of the crime, replacing religious leaders who had held that role before.

It is easy to see that the writer of the second version has closely followed the ideas and even echoed some words of the original. This is a serious form of plagiarism. Even if this writer were to acknowledge the author, there would still be a problem. To simply cite the source at the end would not excuse using so much of the original source.

Ideas. Ideas are also a form of intellectual property. Consider this third version of the previous passage:

At one time, religious leaders shaped the way the public thought about murder. But in nineteenth-century America, this changed. Society’s attitudes were influenced more and more by secular writers.

This version summarizes the original. That is, it states the main idea in compressed form in language that does not come from the original. But it could still be seen as plagiarism if the source is not cited. This example probably makes you wonder if you can write anything without citing a source. To help you sort out what ideas need to be cited and what not, think about these principles:

Common knowledge. There is no need to cite common knowledge . Common knowledge does not mean knowledge everyone has. It means knowledge that everyone can easily access. For example, most people do not know the date of George Washington’s death, but everyone can easily find that information. If the information or idea can be found in multiple sources and the information or idea remains constant from source to source, it can be considered common knowledge. This is one reason so much research is usually done for college writing—the more sources you read, the more easily you can sort out what is common knowledge: if you see an uncited idea in multiple sources, then you can feel secure that idea is common knowledge.

Distinct contributions. One does need to cite ideas that are distinct contributions . A distinct contribution need not be a discovery from the work of one person. It need only be an insight that is not commonly expressed (not found in multiple sources) and not universally agreed upon.

Disputable figures. Always remember that numbers are only as good as the sources they come from. If you use numbers like attendance figures, unemployment rates, or demographic profiles—or any statistics at all—always cite your source of those numbers. If your instructor does not know the source you used, you will not get much credit for the information you have collected.

Everything said previously about using sources applies to all forms of sources. Some students mistakenly believe that material from the Web, for example, need not be cited. Or that an idea from an instructor’s lecture is automatically common property. You must evaluate all sources in the same way and cite them as necessary.

Forms of Citation

You should generally check with your instructors about their preferred form of citation when you write papers for courses. No one standard is used in all academic papers. You can learn about the three major forms or styles used in most any college writing handbook and on many Web sites for college writers:

- The Modern Language Association (MLA) system of citation is widely used but is most commonly adopted in humanities courses, particularly literature courses.

- The American Psychological Association (APA) system of citation is most common in the social sciences.

- The Chicago Manual of Style is widely used but perhaps most commonly in history courses.

Many college departments have their own style guides, which may be based on one of the above. Your instructor should refer you to his or her preferred guide, but be sure to ask if you have not been given explicit direction.

Checklists for Revision and Editing

When you revise…

When you edit…

- A writing course is central to all students’ success in many of their future courses.

- Writing is a process that involves a number of steps; the product will not be good if one does not allow time for the process.

- Seek feedback from classmates, tutors, and instructors during the writing process.

- Revision is not the same thing as editing.

- Many resources are available to college writers.

- Words and ideas from sources must be documented in a form recommended by the instructor.

Checkpoint Exercise

For each of the following statements, circle T for true or F for false:

Learning Objective

Understand the special demands of specific writing situations, including the following:

- Writing in-class essays

- Writing with others in a group project

- Writing in an online class

Everything about college writing so far in this chapter applies in most college writing assignments. Some particular situations, however, deserve special attention. These include writing in-class essays, group writing projects, and writing in an online course.

Writing In-Class Essays

You might well think the whole writing process goes out the window when you have to write an in-class essay. After all, you don’t have much time to spend on the essay. You certainly don’t have time for an extensive revision of a complete draft. You also don’t have the opportunity to seek feedback at any stage along the way. Nonetheless, the best writers of in-class essays bring as much of the writing process as they can into an essay exam situation. Follow these guidelines:

- Prepare for writing in class by making writing a regular part of your study routine. Students who write down their responses to readings throughout a term have a huge advantage over students who think they can study by just reading the material closely. Writing is a way to build better writing, as well as a great way to study and think about the course material. Don’t wait until the exam period to start writing about things you have been studying throughout the term.

- Read the exam prompt or assignment very carefully before you begin to respond. Note keywords in the exam prompt. For example, if the exam assignment asks for an argument, be sure to structure your essay as an argument. Also look for ways the instructor has limited the scope of your response. Focus on what is highlighted in the exam question itself. See Chapter 6 “Preparing for and Taking Tests” for more tips for exam writing.

- Jot notes and sketch out a list of key points you want to cover before you jump into writing. If you have time, you might even draft an opening paragraph on a piece of scratch paper before committing yourself to a particular response. Too often, students begin writing before they have thought about the whole task before them. When that happens, you might find that you can’t develop your ideas as fully or as coherently as you need to. Students who take the time to plan actually write longer in-class essays than those who begin writing their answers right after they have read the assignment. Take as much as a fourth of the total exam period to plan.

- Use a consistent approach for in-class exams. Students who begin in-class exams with a plan that they have used successfully in the past are better able to control the pressure of the in-class exam. Students who feel they need to discover a new approach for each exam are far more likely to panic and freeze.

- Keep track of the time. Some instructors signal the passing of time during the exam period, but do not count on that help. While you shouldn’t compulsively check the time every minute or two, look at your watch now and then.

- Save a few minutes at the end of the session for quick review of what you’ve written and for making small changes you note as necessary.

A special issue in in-class exams concerns handwriting. Some instructors now allow students to write in-class exams on laptops, but the old-fashioned blue book is still the standard in many classes. For students used to writing on a keyboard, this can be a problem. Be sure you don’t let poor handwriting hurt you. Your instructor will have many exams to read. Be courteous. Write as clearly as you can.

Group Writing Projects

College instructors sometimes assign group writing projects. The terms of these assignments vary greatly. Sometimes the instructor specifies roles for each member of the group, but often it’s part of the group’s tasks to define everyone’s role. Follow these guidelines:

- Get off to an early start and meet regularly through the process.

- Sort out your roles as soon as you can. You might divide the work in sections and then meet to pull those sections together. But you might also think more in terms of the specific strengths and interests each of you bring to the project. For example, if one group member is an experienced researcher, that person might gather and annotate materials for the assignment. You might also assign tasks that relate to the stages of the writing process. For example, one person for one meeting might construct a series of questions or a list of points to be addressed, to start a discussion about possible directions for the first draft. Another student might take a first pass at shaping the group’s ideas in a rough draft. And so on. Remember that whatever you do, you cannot likely keep each person’s work separate from the work of others. There will be and probably should be significant overlap if you are to eventually pull together a successful project.

- Be a good citizen. This is the most important point of all. If you are assigned a group project, you should want to be an active part of the group’s work. Never try to ride on the skills of others or let others do more than their fair share. Don’t let any lack of confidence you may feel as a writer keep you from doing your share. One of the great things about a group project is that you can learn from others. Another great thing is that you will learn more about your own strengths that others value.

- Complete a draft early so that you can collectively review, revise, and finally edit together.

- See the section on group presentations in Chapter 7 “Interacting with Instructors and Classes” , Section 7.4 “Public Speaking and Class Presentations” for additional tips.

Writing in Online Courses

Online instruction is becoming more and more common. All the principles discussed in this chapter apply also in online writing—and many aspects are even more important in an online course. In most online courses, almost everything depends on written communication. Discussion is generally written rather than spoken. Questions and clarifications take shape in writing. Feedback on assignments is given in writing. To succeed in online writing, apply the same writing process as fully and thoughtfully as with an essay or paper for any course.

- Even in in-class essays, using an abbreviated writing process approach helps produce more successful writing.

- Group writing projects require careful coordination of roles and cooperative stages but can greatly help students learn how to improve their writing.

- Writing for an online course puts your writing skills to the ultimate test, when almost everything your instructor knows about your learning must be demonstrated through your writing.

List three ways in which a process approach can help you write an in-class essay.

Describe what you see as a strength you could bring to a group writing project.

Explain ways in which writing in an online course emphasizes the social dimension of writing.

Chapter Takeaways

Successful writers in all contexts think of writing as

- a means to learn,

- a social act.

- Paying close attention to the terms of the assignment is essential for understanding the writing approach the instructor expects and for shaping the essay.

- Using the writing process maximizes the mental processes involved in thinking and writing. Take the time to explore prewriting strategies before drafting an essay in order to discover your ideas and how best to shape and communicate them.

- Avoid the temptation, after writing a draft, to consider the essay “done.” Revision is almost always needed, involving more significant changes than just quick corrections and editing.

- Virtually all college writing builds on the ideas of others; this is a significant part of the educational experience. In your writing, be sure you always make it clear in your phrasing and use of citations which ideas are your own or common knowledge and which come from other sources.