- Subject Guides

Academic writing: a practical guide

- Academic writing

- The writing process

- Academic writing style

- Structure & cohesion

- Criticality in academic writing

- Working with evidence

- Referencing

- Assessment & feedback

- Dissertations

- Reflective writing

- Examination writing

- Academic posters

- Feedback on Structure and Organisation

- Feedback on Argument, Analysis, and Critical Thinking

- Feedback on Writing Style and Clarity

- Feedback on Referencing and Research

- Feedback on Presentation and Proofreading

Showing your understanding of a topic and the critical arguments that relate to it.

What are essays?

Most degree programmes include essays. They are the most common form of written assignment and so for most students, being good at essays is essential to gaining good marks, which lead to good grades, which lead to the degree classification desired. Essays are both a particular method of writing and a collection of sub-skills that students need to master during degree studies.

Find out more:

Essays: a Conceptual and Practical Guide [interactive tutorial] | Essays: a Conceptual and Practical Guide [Google Doc]

General essay writing

You have an essay to write... what next .

- Read the assessment brief carefully to find out what the essay is about, what you are required to do specifically. What instructions are you given (discuss, explain, explore)? What choices do you need to make?

- Work through the practical guide to essays above. This will help you to think about what an essay is and what is required of you.

- Look at the assignment writing process . How will you produce your essay?

- Make a plan for when, where, and how you will research, think, draft, and write your essay.

- Execute your plan .

- Finish early. Leave a couple of spare days at the end to edit and proofread .

- Hand it in and move on to the next challenge!

Features of essay writing

Essays vary lots between disciplines and specific tasks, but they share several features that are important to bear in mind.

- They are an argument towards a conclusion. The conclusion can be for or against a position, or just a narrative conclusion. All your writing and argumentation should lead to this conclusion.

- They have a reader. It is essential that you show the logic of your argument and the information it is based on to your reader.

- They are based on evidence . You must show this using both your referencing and also through interacting with the ideas and thinking found within the sources you use.

- They have a structure. You need to ensure your structure is logical and that it matches the expectations of your department. You should also ensure that the structure enables the reader to follow your argument easily.

- They have a word limit. 1000 words means 'be concise and make decisions about exactly what is important to include' whereas 3500 words means 'write in more depth, and show the reader a more complex and broad range of critical understanding'.

- They are part of a discipline/subject area, each of which has conventions . For example, Chemistry requires third person impersonal writing, whereas Women's Studies requires the voice (meaning experiential viewpoint) of the author in the writing.

Types of essay

Each essay task is different and consequently the information below is not designed to be a substitute for checking the information for your specific essay task. It is essential that you check the assessment brief, module handbook and programme handbook, as well as attend any lectures, seminars and webinars devoted to the essay you are working on.

Essays in each subject area belong to a faculty (science, social sciences, arts and Humanities). Essays within the same faculty tend to share some features of style, structure, language choice, and scholarly practices. Please click through to the section relevant to your faculty area and if you want to be curious, the other ones too!

Arts & Humanities essays

Arts and Humanities is a faculty that includes a huge range of subject areas, from Music to Philosophy. Study in the arts and humanities typically focuses on products of the human mind, like music, artistic endeavour, philosophical ideas, and literary productions. This means that essays in the arts and humanities are typically exploring ideas, or interpreting the products of thinking (such as music, art, literature).

There are a range of essay writing styles in arts and humanities, and each subject area has its own conventions and expectations, which are explained and built into modules within each degree programme. Typically, each essay explores an idea, using critical engagement with source material, to produce an argument.

There is typically more reliance on the interpretation of ideas and evidence by the student than in the sciences and social sciences. For the student, the challenge is to understand and control the ideas in each essay, producing a coherent and logical argument that fulfils the essay brief. As with all essays, careful structure, word choices, and language use are essential to succeeding.

Department-specific advice for essays in Arts and Humanities

Some departments provide web-based advice:

- English and Related Literature essay writing advice pages

- Philosophy essay writing advice pages

- Music Department 'House Style' guidance for essay writing

- Language and Linguistic Science style guide

If your department does not appear above, do ask your supervisor or other academic staff what specific guidance is available.

Key Features of Arts and Humanities essays

- They are based on evidence . It is important that ideas used in essays are derived from credible and usable sources to root your essay in the scholarly materials of the subject that you are writing about.

- There is usually a thesis statement. This appears towards the end of your introductory paragraph, concisely outlining the purpose and the main argument of the essay. It is short (once sentence), concise, and precise. Though the essay may have multiple sub-arguments, all must tie into the thesis statement. This means it is important to know, state and stick to the primary focus set out in your thesis statement.

- They require you to interpret evidence. It is unlikely that you will find a source that directly answers the essay question set. You will typically be required to interpret primary and secondary evidence. Primary evidence includes the manuscript of a novel, or a letter describing an historical event. Secondary evidence includes academic books and peer reviewed articles.

- They require you to apply ideas. Many essays will ask you to apply an abstract idea to a scenario, or interpretation of something. For example, you could be asked to apply a Marxist ideology upon Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights or Post-Colonialist theories upon Shakespeare's The Tempest.

- Essays vary greatly in terms of length, required depth of thinking and purpose. You must carefully read the assessment brief and any supporting materials provided to you. It is also important to complete formative tasks that prepare you for an essay, as these will help you to become use to the requirements of the summative essay.

- They must show criticality. When interpreting evidence, or applying ideas in your essay you must be aware that there is more than one possible understanding. Through exploring multiple sources and showing the limits and interconnectedness of ideas you show criticality. More information on criticality can be found on the Criticality page of this guide .

Example extract of an arts and humanities essay

Essay Title: Liturgical expression and national identity during the reign of Æthelred the Unready

This essay is from English studies and shows typical features of an arts and humanities essay. It is examining two ideas, namely 'national identity' and 'liturgical expression' and applying them both to a period of history. The essay does this by analysing linguistic choices, using interpretation from the literature base to create an argument that addresses the essay title.

It also has the feature of the student using sources of evidence to offer an interpretation that may disagree with some published sources. This use of evidence to create an argument that is novel to the student and requires interpretation of ideas is typical of arts and humanities writing. '"engla God", these liturgical verses themselves both signify and enact a ritualised unity with God.' is an example from the essay extract that shows the careful language choices used to create a concise and precise argument that clearly conveys complex thought to the reader from the author.

One way of thinking about a good arts and humanities essay is that it is like you are producing a garment from threads. The overall piece has a shape that people can recognise and understand, and each word, like each stitch, builds the whole piece slowly, whilst some key threads, like core ideas in your argument, run through the whole to hold it all together. It is the threading together of the strands of argument that determines the quality of the final essay, just as the threading of strands in a garment determine the quality of the final piece.

Good arts and humanities essay writing is...

- Based on evidence sources,

- built on the interpretation and application of ideas, evidence and theories,

- a clearly expressed, logical argument that addresses the essay question,

- carefully constructed to guide the reader in a logical path from the introduction to the conclusion,

- filled with carefully chosen language to precisely and accurately convey ideas and interpretations to the reader,

- built on rigorous, careful and close analysis of ideas,

- constructed using careful evaluation of the significance of each idea and concept used,

- readable, meaning it is clear and logical, using clearly understandable English,

- rewarded with high marks.

Common mistakes in arts and humanities essay writing

- Not answering the question posed. It is very easy to answer the question you wished had been asked, or drift away from the question during your writing. Keep checking back to the question to ensure you are still focussed and make a clear plan before writing.

- Moving beyond the evidence. You are required to interpret ideas and evidence that exist, this requires some application and novelty, but should not be making up new ideas/knowledge to make your argument work; your writing must be rooted in evidence.

- Using complex and long words where simpler word choices would convey meaning more clearly. Think of the reader.

- Leaving the reader to draw their own conclusion s, or requiring the reader to make assumptions. They must be able to see your thinking clearly on the page.

- Using lots of direct quotes . There are times when using quotes is important to detail lines from a novel for example, but you need to use them carefully and judiciously, so that most of your writing is based on your use of sources, for which you gain credit.

Social Science essays

Social Sciences, as the name suggests, can be thought of as an attempt to use a 'scientific method' to investigate social phenomena. There is a recognition that applying the strict rules of the level of proof required in science subjects is not appropriate when studying complex social phenomena. But, there is an expectation of as much rigour as is possible to achieve in each investigation.

Consequently, there is a huge variation in the types of essays that can be found within the social sciences. An essay based on the carbon dating of human remains within Archaeology is clearly very different from an essay based on the application of an ethical framework in Human Resources Management. The former is likely to be much more like a science essay, whilst the latter may edge towards a Philosophy essay, which is part of arts and humanities.

Key features of social science essays

- They are evidence-based. It is crucial to use the evidence in a way that shows you understand how significant the evidence used is.

- They require interpretation of evidence . By its nature, evidence in social sciences may be less definite than in sciences, and so interpretation is required. When you interpret evidence, this too must be based on evidence, rather than personal opinion or personal observation.

- They often require the application of abstract theories to real-world scenarios . The theories are 'clean and clear' and the real world is 'messy and unclear'; the skill of the student is to make plausible judgements. For example,

- The level of detail and breadth of knowledge that must be displayed varies greatly, depending on the length of the essay. 1000 word essays need concise wording and for the student to limit the breadth of knowledge displayed in order to achieve the depth needed for a high mark. Conversely, 5000 word essays require both breadth and depth of knowledge.

- They should show criticality. This means you need to show uncertainty in the theories and ideas used, and how ideas and theories interact with others. You should present counter-facts and counter-arguments and use the information in the literature base to reach supported conclusions and judgements.

Example extract of a social science essay

Essay Title: Who Gets What in Education and is that Fair?

Education in the western world has historically favoured men in the regard that women were essentially denied access to it for no other reason than their gender (Trueman,2016) and even though it would seem there is certainly “equality on paper” (Penny, 2010,p1.) when looking at statistics for achievement and gender, the reality is that the struggles facing anyone who does not identify as male require a little more effort to recognise. An excellent example of this can be found in the 2014 OECD report. In the UK women significantly outnumbered men in their application for university places- 376,860 women to 282,170 men (ICEF,2014)- but when observed closer men are applying for places at higher ranking universities and often studying in fields that will eventually allow them to earn better salaries. The same report praised women for the ability to combine their studies with family life and having higher aspirations than boys and therefore likely as being more determined to obtain degrees (ICEF, 2014), yet in reality women have very little choice about coping with the stressful burdens placed on them. The concepts of double burden and triple shift where women are expected to deal with housework and earning an income, or housework, raising children and earning an income (Einhorn, 1993) could in this case relate to the pressure for women to work hard at school to allow them to be able to provide for their families in future. Even women who do not necessarily have their own families or children to care for must face the double burden and triple shift phenomenon in the workplace, as women who work in the higher education sector almost always have the duty of a more pastoral and caring role of their students than male counterparts (Morley,1994).

Education is a social science subject. Some studies within it follow a scientific method of quantitative data collection, whilst others are more qualitative, and others still are more theoretical. In the case of this extract it is about gendered effects in university applications. This is an inevitably complex area to write about, intersecting as it does with social class, economic status, social norms, cultural history, political policy... To name but a few.

The essay is clearly based on evidence, which in places in numerical and in places is derived from previously written papers, such as 'triple shift where women are expected to deal with housework and earning an income, or housework, raising children and earning an income (Einhorn, 1993)', where the concept of triple shift is derived from the named paper. It is this interleaving of numerical and concrete facts with theoretical ideas that have been created and/or observed that is a typical feature in social sciences. In this case, the author has clearly shown the reader where the information is from and has 'controlled' the ideas to form a narrative that is plausible and evidence-based.

When compared to science writing, it can appear to be more wordy and this is largely due to the greater degree of interpretation that is required to use and synthesise complex ideas and concepts that have meanings that are more fluid and necessarily less precise than many scientific concepts.

Good social science essay writing is...

- filled with clearly articulated thinking from the mind of the author,

- well structured to guide the reader through the argument or narrative being created,

- focussed on answering the question or addressing the task presented,

- filled with carefully chosen evaluative language to tell the reader what is more and less significant,

- readable - sounds simple, but is difficult to achieve whilst remaining precise,

Common mistakes in social science essay writing

- Speculating beyond the limits of the evidence presented . It is important to limit your interpretation to that which is supported by existing evidence. This can be frustrating, but is essential.

- Using complex words where simpler ones will do. It is tempting to try to appear 'clever' by using 'big words', but in most cases, the simplest form of writing something is clearer. Your aim is to clearly communicate with the reader.

- Giving your personal opinion - this is rarely asked for or required.

- Not answering the question or fulfilling the task . This is possibly the most common error and largely comes from letting one's own ideas infect the essay writing process.

- Not being critical. You need to show the limits of the ideas used, how they interact, counter-arguments and include evaluation and analysis of the ideas involved. If you find yourself being descriptive, ask why.

- Using lots of direct quotes, particularly in first year writing . Quotes should be rare and used carefully because they are basically photocopying. Use your words to show you have understood the concepts involved.

Science essays

Science essays are precise, logical and strictly evidence-based pieces of writing. They employ cautious language to accurately convey the level of certainty within the scientific understanding that is being discussed and are strictly objective. This means that the author has to make the effort to really understand the meaning and significance of the science being discussed.

In a science essay, your aim is to summarise and critically evaluate existing knowledge in the field. If you're doing your own research and data collection, that will be written up in a report instead.

The skill of the student is to thread together the ideas and facts they have read in a logical order that addresses the task set. When judgements are made they must be justified against the strength and significance of the theories, findings, and ideas being used. Generally, the student should not be undertaking their own interpretation of the results and facts, but instead be using those of others to create a justifiable narrative.

Example extract of a science essay

Essay title: To what extent has Ungerleider and Mishkin’s notion of separate ‘what’ and ‘where’ pathways been vindicated by neuropsychological research?

Van Polanen & Davare (2015) showed that the dorsal stream and ventral streams are not strictly independent, but do interact with each other. Interactions between dorsal and ventral streams are important for controlling complex object-oriented hand movements, especially skilled grasp. Anatomical studies have reported the existence of direct connections between dorsal and ventral stream areas. These physiological interconnections appear to gradually more active as the precision demands of the grasp become higher.

However, cognition is a dynamic process, and a flexible interactive system is required to coordinate and modulate activity across cortical networks to enable the adaptation of processing to meet variable task demands. The clear division of the dorsal and ventral processing streams is artificial, resulting from experimental situations, which do not reflect processing within the natural environment (Weiller et al., 2011). Most successful execution of visual behaviours require the complex collaboration and seamless integration of processing between the two systems.

Cloutman (2013) had stated that dorsal and ventral streams can be functionally connected in three regards: (1) the independent processing account – where they remain separate but terminate on the same brain area, (2) the feedback account – where feedback loops from locations downstream on one pathway is constantly providing input to the other and (3) the continuous cross-talk account – where information is transferred to and from the system constantly when processing.

Indeed, the authors found that there were numerous anatomical cross-connections between the two pathways, most notably between inferior parietal and inferior temporal areas. For example, ventral regions TE and TEO have been found to have extensive connectivity with dorsal stream areas, demonstrating direct projections with areas including V3A, MT, MST, FST and LIP (Baizer et al., 1991; Disler et al., 1993).

The first obvious comment is that it is not going to win a prize for literary entertainment! The writing is what one might call 'dry'. This is because it is good scientific writing. It is clearly evidence-based, and is explaining complex interrelationships in a way that is clear, leaves little for the reader to assume and that uses carefully graded language to show the significance of each fact.

The language choices are carefully aligned with the strength of the evidence that is used. For example, 'have been found to have extensive interconnectivity' is graded to convey that many connections have been detailed in the evidence presented. Similarly, 'Most successful execution of visual behaviours require the complex collaboration' is graded carefully to convey meaning to the reader, derived from the evidence used. The sample displays many examples of controlled word choices that leave the reader in no doubt regarding the meaning they are to take from reading the piece. This concise, controlled, evidence-based and carefully considered writing is typical of that found in the science essays.

Good science essay writing is...

- evidence-based,

- cohesive due to language choices,

- well-structured to help the reader follow the ideas,

- carefully planned,

- filled with carefully chosen evaluative and analytical language,

- rewarded with high grades.

Common mistakes in science essay writing

- The most common mistake is a lack of accuracy in the language used to convey meaning. This can be due to inadequate reading or a lack of understanding of the subject matter, or alternatively, due to not giving sufficient care to word choice. 'Increased greatly' is different to 'increased', which is different again to 'increased significantly'; it is very important that you understand what you are writing about in enough detail that you can accurately convey an understanding of it accurately to the reader.

- Trying to put 'you' into the essay. It is highly unlikely that you will be required to refer to your own viewpoints, opinions or lived experience within scientific essay writing. Science is impersonal, it deals in fact, and so you are a third person, impersonal author who is interpreting and curating facts and knowledge into an essay that makes sense to the reader.

- Going beyond the facts. It is rare that you will be asked to speculate in a science essay. When you are, you will be asked to extrapolate from known understanding in the relevant literature. Stick to the facts and to their meaning and significance.

- Not placing understanding in context . Each scientific idea sits within a bigger discipline and interacts with other ideas. When you write about ideas, you need to acknowledge this, unless you are specifically told to only focus on one idea. An example would be genomics of viral pathogens, which is currently a much discussed area of activity. This sits within public health, virology, and genomics disciplines, to name a few. Depending on how it is to be written about, you may need to acknowledge one or more of these larger areas.

Using evidence in essays

Sources of evidence are at the heart of essay writing. You need sources that are both usable and credible, in the specific context of your essay.

A good starting point is often the materials used in the module your essay is attached to. You can then work outwards into the wider field of study as you develop your thinking, and seek to show critical analysis, critical evaluation and critical thought in your essay.

Discover more about using evidence in your assignments:

Structuring an essay

Clear structure is a key element of an effective essay. This requires careful thought and you to make choices about the order the reader needs the information to be in.

These resources contain advice and guides to help you structure your work:

You can use these templates to help develop the structure of your essay.

Go to File > Make a copy... to create your own version of the template that you can edit.

Structuring essay introductions

Play this tutorial in full screen

- Explain the different functions that can be fulfilled by an introduction.

- Provide examples of introductions from the Faculties of Social Sciences, Sciences, and Arts and Humanities.

- Evaluating your own introductions.

- Matching elements of an introduction to a description of their purpose.

- Highlighting where evidence is used to support elements of the introduction.

- Highlighting how introductions can make clear links to the essay question.

In this section, you will learn about the functions and key components of an essay introduction.

An introduction can fulfill the functions below. These often move from a broad overview of the topic in context to a narrow focus on the scope of the discussion, key terms and organisational structure.

Click on each function to reveal more.

- It can establish the overall topic and explain the relevance and significance of the essay question to that topic

- What is the topic?

- Why is the essay question worth exploring? Why is the essay worth reading?

- How is it relevant to wider / important / current debates in the field?

- It can briefly explain the background and context and define the scope of the discussion

- Is it helpful to mention some background, historical or broader factors to give the reader some context?

- Is the discussion set in a particular context (geographical; political; economic; social; historical; legal)?

- Does the essay question set a particular scope or are you going to narrow the scope of the discussion?

- It can highlight key concepts or ideas

- Are the key concepts or ideas contentious or open to interpretation?

- Will the key concepts need to be defined and explained?

- It can signpost the broad organisational structure of the essay

- Indicate what you will cover and a brief overview of the structure of your essay

- points made should be supported by evidence

- clear links should be made to the question

Note: Introductions may not cover all of these elements, and they may not be covered in this order.

Useful Link: See the University of Manchester’s Academic Phrasebank for useful key phrases to introduce work.

In this activity, you will review and evaluate introductions you have written, identifying areas for improvement.

Find some examples of introductions you have written for essays.

- Which of the features do they use?

- Are any elements missing?

- How might you improve them?

For the following tasks, you will be using an example introduction from one of the following three faculties. Select a faculty to use an introduction from a corresponding subject.

In this activity, you will look at examples of introductions, identifying key features and their purpose.

Here is an example question:

Sociology: Examine some of the factors that influence procrastination in individuals, exploring and evaluating their impact. Identify an area(s) for future research, justifying your choice.

And here is a sample introduction written for this question:

Procrastination is a complex concept which manifests itself in different types of behaviour yet is experienced by individuals universally. A useful definition of procrastination is ‘the voluntary delay of important, necessary, and intended action despite knowing there will be negative consequences for this delay’ (Ferrari and Tice, 2000, Sirois and Pychyl, 2013 cited in Sirois and Giguère, 2018). The influences on procrastination are multi-faceted, which makes their study incredibly challenging. Researchers are now producing a body of work dedicated to procrastination; including meta-analyses such as those by Varvaricheva (2010) and Smith (2015). Influences on procrastination can be considered in two categories, factors with external, environmental, sources and factors with internal sources due to individual differences. However, these external and environmental categories are not completely independent of one another and this essay will seek to explore the complexities of this interdependence. This essay will discuss how different factors influence individual procrastination, by first examining how gender, age and personality affect the procrastination trait under internal factors, before discussing the external factors; how task aversiveness, deadlines and the internet affect procrastination behavioural outcomes. This will be followed by a brief exploration of how the two interact. Finally there a number of gaps in the literature, which suggest avenues for future research.

Click on the Next arrow to match each section of this introduction with a description of its purpose.

Procrastination is a complex concept which manifests itself in different types of behaviour yet is experienced by individuals universally.

Signposts the broad organisational structure of the essay

Narrows the topic and explains its relevance or significance to current debates

Defines the scope of the discussion

Establishes the topic and explains its broad significance

Defines key concepts

That's not the right answer

Have another go.

Yes, that's the right answer!

A useful definition of procrastination is ‘the voluntary delay of important, necessary, and intended action despite knowing there will be negative consequences for this delay’ (Ferrari and Tice, 2000, Sirois and Pychyl, 2013 cited in Sirois and Giguère, 2018).

The influences on procrastination are multi-faceted, which makes their study incredibly challenging. Researchers are now producing a body of work dedicated to procrastination; including meta-analyses such as those by Varvaricheva (2010) and Smith (2015).

Influences on procrastination can be considered in two categories, factors with external, environmental, sources and factors with internal sources due to individual differences. However, these external and environmental categories are not completely independent of one another and this essay will seek to explore the complexities of this interdependence.

This essay will discuss how different factors influence individual procrastination, by first examining how gender, age and personality affect the procrastination trait under internal factors, before discussing the external factors; how task aversiveness, deadlines and the internet affect procrastination behavioural outcomes. This will be followed by a brief exploration of how the two interact. Finally there a number of gaps in the literature, which suggest avenues for future research.

In this activity, you will identify how introductions make links to the question.

Here is the question again:

Click to highlight the places where the introduction below links closely to the question.

Have another go. You can remove the highlighting on sections by clicking on them again.

Those are the parts of the introduction that link closely to the question.

In this activity, you will consider how introductions make use of supporting evidence.

- Define key concepts

- Establish the topic and explain its relevance or significance

Click to highlight the places where the introduction below supports points with evidence .

Those are the parts of the introduction that use evidence to support points.

Congratulations! You've made it through the introduction!

Click on the icon at the bottom to restart the tutorial.

Nursing: Drawing on your own experiences and understanding gained from the module readings, discuss and evaluate the values, attributes and behaviours of a good nurse.

The Nursing and Midwifery Council’s (NMC) (2015) Code states that a nurse must always put the care of patients first, be open and honest, and be empathic towards patients and their families. Student nurses are expected to demonstrate an understanding of the need for these key skills even at the interview stage and then gain the experiences to develop certain fundamental attributes, values and behaviours in order to advance through the stages of nursing. This assignment will highlight a variety of values, attributes and behaviours a good nurse should have, focusing on courage in particular. Views of courage from political, professional, and social perspectives will be considered, alongside a comparison between the attribute courage and a student nurse’s abilities. This will be demonstrated using observations from practice, appropriate theorists such as Sellman (2011), Lachman (2010) and philosophers including Aristotle and Ross (2011).

The Nursing and Midwifery Council’s (NMC) (2015) Code states that a nurse must always put the care of patients first, be open and honest, and be empathic towards patients and their families.

Explains the context to the discussion, with reference to the workplace

Defines the scope of the discussion by narrowing it

Defines relevant key concepts or ideas

Student nurses are expected to demonstrate an understanding of the need for these key skills even at the interview stage and then gain the experiences to develop certain fundamental attributes, values and behaviours in order to advance through the stages of nursing.

This assignment will highlight a variety of values, attributes and behaviours a good nurse should have, focusing on courage in particular.

Views of courage from political, professional, and social perspectives will be considered, alongside a comparison between the attribute courage and a student nurse’s abilities. This will be demonstrated using observations from practice, appropriate theorists such as Sellman (2011), Lachman (2010) and philosophers including Aristotle and Ross (2011).

- Define relevant key concepts or ideas

- Signpost the broad organisational structure of the essay, making a clear link to the question

Archaeology: Explain some of the ways in which Star Carr has been re-interpreted since the initial discovery in the 1940s. Briefly evaluate how the results of recent excavations further dramatically affect our understanding of this site.

Star Carr has become the ‘best known’ Mesolithic site in Britain (Conneller, 2007, 3), in part because of its high levels of artefact preservation due to waterlogging, as the site was once on the Eastern edge of the ancient Lake Flixton, close to a small peninsula (Taylor, 2007). First excavated by Grahame Clark in 1949-51, there was a further invasive investigation in 1985 and 1989, again in 2006-8, and 2010. An impressive haul of artefacts have been excavated over the years, including bone and antler tools, barbed points, flint tools and microliths, and enigmatic red deer frontlets (Milner et al., 2016). Since Clark’s first published report in 1954 there have been numerous re-examinations of the subject, including by Clark himself in 1974. Resulting interpretations of the site have been much debated; it has been classified as ‘in situ settlement, a refuse dump, and the result of culturally prescribed acts of deposition’ (Taylor et al., 2017). This discussion will explore the ways in which the site has been variously re-interpreted during this time period, and consider how more recent study of the site has prompted new perspectives.

Star Carr has become the ‘best known’ Mesolithic site in Britain (Conneller, 2007, 3), in part because of its high levels of artefact preservation due to waterlogging, as the site was once on the Eastern edge of the ancient Lake Flixton, close to a small peninsula (Taylor, 2007).

Explains the background to the discussion and its significance

Establishes the topic

Explains the scope of the topic and highlights key interpretations

First excavated by Grahame Clark in 1949-51, there was a further invasive investigation in 1985 and 1989, again in 2006-8, and 2010. An impressive haul of artefacts have been excavated over the years, including bone and antler tools, barbed points, flint tools and microliths, and enigmatic red deer frontlets (Milner et al., 2016).

Since Clark’s first published report in 1954 there have been numerous re-examinations of the subject, including by Clark himself in 1974. Resulting interpretations of the site have been much debated; it has been classified as ‘in situ settlement, a refuse dump, and the result of culturally prescribed acts of deposition’ (Taylor et al., 2017).

This discussion will explore the ways in which the site has been variously re-interpreted during this time period, and consider how more recent study of the site has prompted new perspectives.

- Establish the topic, explains the background and significance

- Explains the significance of the topic

- Highlights key interpretations

Structuring essay conclusions

In this section you will consider the different functions a conclusion can fulfil, look at examples of conclusions, and identify key features and their purpose.

A conclusion can fulfil the functions below. These often move from a narrow focus on the outcomes of the discussion to a broad view of the topic's relevance to the wider context.

Summary of the main points in relation to the question

- This might involve restating the scope of the discussion and clarifying if there any limitations of your discussion or of the evidence provided

- This may include synthesising the key arguments and weighing up the evidence

Arrive at a judgement or conclusion

- Having weighed up the evidence, come to a judgement about the strength of the arguments

Restate the relevance or significance of the topic to the wider context

- Make it clear why your conclusions - which are based on your discussion through the essay - are important or significant in relation to wider/current debates in the field

Make recommendations or indicate the direction for further study, if applicable

- Recommendations may be for further research or for practice/policy

- What further research/investigation would be necessary to overcome the limitations above?

- What are the implications of your findings for policy/practice?

Note: Conclusions may not cover all of these elements, and they may not be covered in this order.

- Clear links should be made to the question

- Do not make new points in the conclusion

Useful Link: See the University of Manchester’s Academic Phrasebank for useful key phrases to conclude work.

In this activity, you will look at an example conclusion, identifying key features and their purpose.

In this task, you will be using an example conclusion from one of the following three faculties. Select a faculty to use a conclusion from a corresponding subject.

And here is a sample conclusion written for the question:

In conclusion procrastination is a complex psychological phenomenon that is influenced by a number of factors, both internal and external. However it has a hugely multifaceted nature and the factors that influence it are not truly independent of one another. Character traits and the environmental impact on behaviour are interrelated; for example similar procrastination outcomes may arise from a highly conscientious individual in a distracting environment and an individual low in conscientiousness in a non-distracting setting. This means that future studies need to be very considered in their approach to separating, or controlling for, these factors. These further studies are important and urgently needed as the impact of procrastination on society is far-reaching. For instance: individuals delay contributing to a pension, meaning that old age may bring poverty for many; couples put off entering into formal contracts with each other, potentially increasing disputes over child custody and inheritance; and indeed women delay starting a family and increasing age leads to decreased fertility, thus leading to higher societal costs of providing assisted fertilisation. Furthermore one could expand the scope to include the effects on children of being born to older parents (such as risks of inherited genetic defects). These are themselves wide fields of study and are mentioned merely to illustrate the importance of further research. Until the nature of influences on procrastination is fully understood, our development of approaches to reduce procrastination is likely to be hindered.

Click on the Next arrow to match each section of the conclusion with a description of its purpose.

In conclusion procrastination is a complex psychological phenomenon that is influenced by a number of factors, both internal and external.

Synthesises the key arguments and weighs up the evidence

Indicates limitations

Restates the scope of the discussion

Indicates the direction and significance for further study

Summary of the main point in relation to the question

However it has a hugely multifaceted nature and the factors that influence it are not truly independent of one another.

Character traits and the environmental impact on behaviour are interrelated; for example similar procrastination outcomes may arise from a highly conscientious individual in a distracting environment and an individual low in conscientiousness in a non-distracting setting.

This means that future studies need to be very considered in their approach to separating, or controlling for, these factors. These further studies are important and urgently needed as the impact of procrastination on society is far-reaching. For instance: individuals delay contributing to a pension, meaning that old age may bring poverty for many; couples put off entering into formal contracts with each other, potentially increasing disputes over child custody and inheritance; and indeed women delay starting a family and increasing age leads to decreased fertility, thus leading to higher societal costs of providing assisted fertilisation. Furthermore one could expand the scope to include the effects on children of being born to older parents (such as risks of inherited genetic defects). These are themselves wide fields of study and are mentioned merely to illustrate the importance of further research.

Until the nature of influences on procrastination is fully understood, our development of approaches to reduce procrastination is likely to be hindered.

Opportunities for nurses to display courage occur every day, although it is at the nurse’s discretion whether they act courageously or not. As discussed in this assignment, courage is likewise an important attribute for a good nurse to possess and could be the difference between good and bad practice. It is significantly important that nurses speak up about bad practice to minimize potential harm to patients. However nurses do not need to raise concerns in order to be courageous, as nurses must act courageously every day. Professional bodies such as the RCN and NMC recognise that courage is important by highlighting this attribute in the RCN principles. The guidelines for raising concerns unite the attribute courage with the RCN’s principles of nursing practice by improving nurses’ awareness of how to raise concerns. Lachman’s (2010) CODE is an accessible model that modern nurses could use as a strategy to help them when raising concerns. Although students find it difficult to challenge more senior nursing professionals, they could also benefit from learning the acronym to help them as they progress through their career. For nursing students, courage could be seen as a learning development of the ability to confront their fear of personal emotional consequences from participating in what they believe to be the right action. On the whole a range of values, attributes and behaviours are needed in order to be a good nurse, including being caring, honest, compassionate, reliable and professional. These qualities are all important, but courage is an attribute that is widely overlooked for nurses to possess but vitally fundamental.

Opportunities for nurses to display courage occur every day, although it is at the nurse’s discretion whether they act courageously or not. As discussed in this assignment, courage is likewise an important attribute for a good nurse to possess and could be the difference between good and bad practice. It is significantly important that nurses speak up about bad practice to minimize potential harm to patients. However nurses do not need to raise concerns in order to be courageous, as nurses must act courageously every day.

Arrives at an overall judgement or conclusion

Make recommendations for practice

Professional bodies such as the RCN and NMC recognise that courage is important by highlighting this attribute in the RCN principles. The guidelines for raising concerns unite the attribute courage with the RCN’s principles of nursing practice by improving nurses’ awareness of how to raise concerns. Lachman’s (2010) CODE is an accessible model that modern nurses could use as a strategy to help them when raising concerns.

Although students find it difficult to challenge more senior nursing professionals, they could also benefit from learning the acronym to help them as they progress through their career. For nursing students, courage could be seen as a learning development of the ability to confront their fear of personal emotional consequences from participating in what they believe to be the right action.

On the whole a range of values, attributes and behaviours are needed in order to be a good nurse, including being caring, honest, compassionate, reliable and professional. These qualities are all important, but courage is an attribute that is widely overlooked for nurses to possess but vitally fundamental.

Star Carr is one of the most fascinating and informative Mesolithic sites in the world. What was once considered to be the occasional winter settlement of a group of hunter-gatherer families, now appears to be a site of year-round settlement occupied over centuries. Since its initial discovery and excavation in the late 1940s and early 1950s, a great deal of further data has been collected, altering interpretations made by the primary excavators who pioneered analysis of the site. What once was considered a typical textbook Mesolithic hunting encampment is now theorized to be a site of ritual importance. The site has produced unique findings such as a multitude of barbed points, twenty one antlered headdresses and the earliest known example of a permanent living structure in Britain. These factors will combine to immortalise the site, even when its potential for further research is thoroughly decayed, which tragically could be very soon (Taylor et al. 2010).

Star Carr is one of the most fascinating and informative Mesolithic sites in the world.

Synthesise the main points

Limitations and implications for future research

Restate the significance of the topic to the wider context

What was once considered to be the occasional winter settlement of a group of hunter-gatherer families, now appears to be a site of year-round settlement occupied over centuries. Since its initial discovery and excavation in the late 1940s and early 1950s, a great deal of further data has been collected, altering interpretations made by the primary excavators who pioneered analysis of the site. What once was considered a typical textbook Mesolithic hunting encampment is now theorized to be a site of ritual importance. The site has produced unique findings such as a multitude of barbed points, twenty one antlered headdresses and the earliest known example of a permanent living structure in Britain.

These factors will combine to immortalise the site, even when its potential for further research is thoroughly decayed, which tragically could be very soon (Taylor et al. 2010).

Congratulations! You've made it through the conclusion!

Click on the icon below to restart the tutorial.

Other support for essay writing

Online resources.

The general writing pages of this site offer guidance that can be applied to all types of writing, including essays. Also check your department guidance and VLE sites for tailored resources.

Other useful resources for essay writing:

Appointments and workshops

There is lots of support and advice for essay writing. This is likely to be in your department, and particularly from your academic supervisor and module tutors, but there is also central support, which you can access using the links below.

- << Previous: Types of academic writing

- Next: Reports >>

- Last Updated: Apr 3, 2024 4:02 PM

- URL: https://subjectguides.york.ac.uk/academic-writing

The Writing Guide

- The First Thing

- Step 1: Understanding the essay question

Identify task, content & limiting words in the essay question

Words, words, words..., academic writing webinar part 1.

- Step 2: Critical note-taking

- Step 3: Planning your assignment

- Step 4a: Effective writing

- Step 4b: Summarizing & paraphrasing

- Step 4c: Academic language

- Step 5: Editing and reviewing

- Getting started with research

- Working with keywords

- Evaluating sources

- Research file

- Reading Smarter

- Sample Essay

- What, why, where, when, who?

- Referencing styles

- Writing Resources

- Exams and Essay Questions

Essay topics contain key words that explain what information is required and how it is to be presented. Using the essay question below indentify task content & limiting words. Regardless of your topic or discipline, if you can identify these words in your essay topic, you can begin to consider what you will need to do to answer the question.

Task words : These are words that tell you what to do, for example “compare”, “discuss”, “critically evaluate”, “explain” etc.

Content words : These words in the essay topic will tell you which ideas and concepts should form the knowledge base of the assignment. Refer to subject specific dictionary or glossary.

Effective communication is considered a core skill in higher education and is usually conveyed through the medium of academic papers and essays. Discuss the process of writing academic essays and critically examine the importance of structure and content.

Before you scroll down to the next box, what can you unpack from this topic? What are you actually going to look for in a search tool like One Search? What are you supposed to do?

- Content Words

- Limiting Words

- Context Words

Task words are usually verbs and they tell you what to do to complete your assignment.

You need to identify these words, because you will need to follow these instructions to pass the assignment. As you research and write your assignment, check these words occasionally to make sure you are still doing what you have been asked to do.

Here are some definitions of different academic task words. Make sure you know exactly what you need to do for your assignment.

Don't try to use them in your research - they aren't things to find, only things to do.

The task words from our sample question are:

Effective communication is considered a core skill in higher education and is usually conveyed through the medium of academic papers and essays. Discuss the process of writing academic essays and critically examine the importance of structure and content.

- Discuss means to "consider and offer an interpretation or evaluation of something; or give a judgment on the value of arguments for and against something"

- Examine means to inspect something in detail and investigate the implications

So, you would need to give a short description of what essay writing is all about, and then offer an evaluation of the essay structure and the way it presents content.

- Task Words Here are some definitions of different academic task words. Make sure you know exactly what you need to do for your assignment.

The content words are the "meat" of the question - these are things you can research.

Effective communication is considered a core skill in higher education and is usually conveyed through the medium of academic papers and essays . Discuss the process of writing academic essays and critically examine the importance of structure and content .

You will often be asked to talk about "the role" something plays or "processes", "importance", "methods" or "implementations" - but you can't really research these things just by looking for those words.

You need to find the keywords - the most concrete concepts - and search for those. The information you find about the concrete terms will tell you about the "roles" and "methods", the "process" or the "importance", but they probably won't use those words exactly.

One of the core skills of academic research is learning to extrapolate : to find the connections in the information you can find that will help you answer the questions which don't have clear, cut-and-dry answers in the books and articles.

So, the core keywords/concepts to research are:

- "academic writing"

- "higher education"

- structure and content

Limiting words keep you focused on a particular area, and stop you from trying to research everything in the history of mankind.

They could limit you by:

- Time (you may be asked to focus on the last 5 years, or the late 20th Century, for example)

- Place (you may be asked to focus on Australia, or Queensland, or South-East Asia)

- People groups (such as "women over the age of 50" or "people from low socio-economic backgrounds" or "Australians of Asian descent")

- Extent (you are only to look at a particular area, or the details you believe are most relevant or appropriate).

In this example, you have two limits:

- "higher education" is the industry focus. This could be expanded to include the tertiary or university sector.

- Essays - we are concentrating on essay writing as the aspect of communication. Note that this is also a content word. There can be (and usually is) some crossover.

Sometimes it can help to add your own limits . With health sciences, you almost always limit your research to the last five or six years. Social sciences are not as strict with the date range but it's still a good idea to keep it recent. You could specifically look at the Australian context. You may decide to focus on the private sector within that industry.

With the question above you could limit yourself to only looking at first year university students.

Sometimes an assignment task will give you phrases or sentences that aren't part of the task at all: they exist to give you some context .

These can be ignored when you do your research, but you should read over them occasionally as you are writing your assignment. They help you know what the lecturer was thinking about (and wanted you to think about) when they set that task.

Effective communication is considered a core skill in higher education and is usually conveyed through the medium of academic papers and essays . Discuss the process of writing academic essays and critically examine the importance of structure and content.

You don't have to do anything with the first sentence of this question - but it does get you to think specifically about the "using essays to communicate knoweldge" - something that isn't mentioned in the task itself.

Obviously, whoever wrote the task wants you to think about the assignments as a form of writing and communication.

It is easy to get distracted and go off on tangents when doing your research . Use the context words to help you keep your focus where it should be.

- << Previous: Writing Process

- Next: Step 2: Critical note-taking >>

- Last Updated: Apr 26, 2024 9:33 AM

- URL: https://libguides.jcu.edu.au/writing

The writer of the academic essay aims to persuade readers of an idea based on evidence. The beginning of the essay is a crucial first step in this process. In order to engage readers and establish your authority, the beginning of your essay has to accomplish certain business. Your beginning should introduce the essay, focus it, and orient readers.

Introduce the Essay. The beginning lets your readers know what the essay is about, the topic . The essay's topic does not exist in a vacuum, however; part of letting readers know what your essay is about means establishing the essay's context , the frame within which you will approach your topic. For instance, in an essay about the First Amendment guarantee of freedom of speech, the context may be a particular legal theory about the speech right; it may be historical information concerning the writing of the amendment; it may be a contemporary dispute over flag burning; or it may be a question raised by the text itself. The point here is that, in establishing the essay's context, you are also limiting your topic. That is, you are framing an approach to your topic that necessarily eliminates other approaches. Thus, when you determine your context, you simultaneously narrow your topic and take a big step toward focusing your essay. Here's an example.

The paragraph goes on. But as you can see, Chopin's novel (the topic) is introduced in the context of the critical and moral controversy its publication engendered.

Focus the Essay. Beyond introducing your topic, your beginning must also let readers know what the central issue is. What question or problem will you be thinking about? You can pose a question that will lead to your idea (in which case, your idea will be the answer to your question), or you can make a thesis statement. Or you can do both: you can ask a question and immediately suggest the answer that your essay will argue. Here's an example from an essay about Memorial Hall.

The fullness of your idea will not emerge until your conclusion, but your beginning must clearly indicate the direction your idea will take, must set your essay on that road. And whether you focus your essay by posing a question, stating a thesis, or combining these approaches, by the end of your beginning, readers should know what you're writing about, and why —and why they might want to read on.

Orient Readers. Orienting readers, locating them in your discussion, means providing information and explanations wherever necessary for your readers' understanding. Orienting is important throughout your essay, but it is crucial in the beginning. Readers who don't have the information they need to follow your discussion will get lost and quit reading. (Your teachers, of course, will trudge on.) Supplying the necessary information to orient your readers may be as simple as answering the journalist's questions of who, what, where, when, how, and why. It may mean providing a brief overview of events or a summary of the text you'll be analyzing. If the source text is brief, such as the First Amendment, you might just quote it. If the text is well known, your summary, for most audiences, won't need to be more than an identifying phrase or two:

Often, however, you will want to summarize your source more fully so that readers can follow your analysis of it.

Questions of Length and Order. How long should the beginning be? The length should be proportionate to the length and complexity of the whole essay. For instance, if you're writing a five-page essay analyzing a single text, your beginning should be brief, no more than one or two paragraphs. On the other hand, it may take a couple of pages to set up a ten-page essay.

Does the business of the beginning have to be addressed in a particular order? No, but the order should be logical. Usually, for instance, the question or statement that focuses the essay comes at the end of the beginning, where it serves as the jumping-off point for the middle, or main body, of the essay. Topic and context are often intertwined, but the context may be established before the particular topic is introduced. In other words, the order in which you accomplish the business of the beginning is flexible and should be determined by your purpose.

Opening Strategies. There is still the further question of how to start. What makes a good opening? You can start with specific facts and information, a keynote quotation, a question, an anecdote, or an image. But whatever sort of opening you choose, it should be directly related to your focus. A snappy quotation that doesn't help establish the context for your essay or that later plays no part in your thinking will only mislead readers and blur your focus. Be as direct and specific as you can be. This means you should avoid two types of openings:

- The history-of-the-world (or long-distance) opening, which aims to establish a context for the essay by getting a long running start: "Ever since the dawn of civilized life, societies have struggled to reconcile the need for change with the need for order." What are we talking about here, political revolution or a new brand of soft drink? Get to it.

- The funnel opening (a variation on the same theme), which starts with something broad and general and "funnels" its way down to a specific topic. If your essay is an argument about state-mandated prayer in public schools, don't start by generalizing about religion; start with the specific topic at hand.

Remember. After working your way through the whole draft, testing your thinking against the evidence, perhaps changing direction or modifying the idea you started with, go back to your beginning and make sure it still provides a clear focus for the essay. Then clarify and sharpen your focus as needed. Clear, direct beginnings rarely present themselves ready-made; they must be written, and rewritten, into the sort of sharp-eyed clarity that engages readers and establishes your authority.

Copyright 1999, Patricia Kain, for the Writing Center at Harvard University

What is an Essay?

10 May, 2020

11 minutes read

Author: Tomas White

Well, beyond a jumble of words usually around 2,000 words or so - what is an essay, exactly? Whether you’re taking English, sociology, history, biology, art, or a speech class, it’s likely you’ll have to write an essay or two. So how is an essay different than a research paper or a review? Let’s find out!

Defining the Term – What is an Essay?

The essay is a written piece that is designed to present an idea, propose an argument, express the emotion or initiate debate. It is a tool that is used to present writer’s ideas in a non-fictional way. Multiple applications of this type of writing go way beyond, providing political manifestos and art criticism as well as personal observations and reflections of the author.

An essay can be as short as 500 words, it can also be 5000 words or more. However, most essays fall somewhere around 1000 to 3000 words ; this word range provides the writer enough space to thoroughly develop an argument and work to convince the reader of the author’s perspective regarding a particular issue. The topics of essays are boundless: they can range from the best form of government to the benefits of eating peppermint leaves daily. As a professional provider of custom writing, our service has helped thousands of customers to turn in essays in various forms and disciplines.

Origins of the Essay

Over the course of more than six centuries essays were used to question assumptions, argue trivial opinions and to initiate global discussions. Let’s have a closer look into historical progress and various applications of this literary phenomenon to find out exactly what it is.

Today’s modern word “essay” can trace its roots back to the French “essayer” which translates closely to mean “to attempt” . This is an apt name for this writing form because the essay’s ultimate purpose is to attempt to convince the audience of something. An essay’s topic can range broadly and include everything from the best of Shakespeare’s plays to the joys of April.

The essay comes in many shapes and sizes; it can focus on a personal experience or a purely academic exploration of a topic. Essays are classified as a subjective writing form because while they include expository elements, they can rely on personal narratives to support the writer’s viewpoint. The essay genre includes a diverse array of academic writings ranging from literary criticism to meditations on the natural world. Most typically, the essay exists as a shorter writing form; essays are rarely the length of a novel. However, several historic examples, such as John Locke’s seminal work “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding” just shows that a well-organized essay can be as long as a novel.

The Essay in Literature

The essay enjoys a long and renowned history in literature. They first began gaining in popularity in the early 16 th century, and their popularity has continued today both with original writers and ghost writers. Many readers prefer this short form in which the writer seems to speak directly to the reader, presenting a particular claim and working to defend it through a variety of means. Not sure if you’ve ever read a great essay? You wouldn’t believe how many pieces of literature are actually nothing less than essays, or evolved into more complex structures from the essay. Check out this list of literary favorites:

- The Book of My Lives by Aleksandar Hemon

- Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin

- Against Interpretation by Susan Sontag

- High-Tide in Tucson: Essays from Now and Never by Barbara Kingsolver

- Slouching Toward Bethlehem by Joan Didion

- Naked by David Sedaris

- Walden; or, Life in the Woods by Henry David Thoreau

Pretty much as long as writers have had something to say, they’ve created essays to communicate their viewpoint on pretty much any topic you can think of!

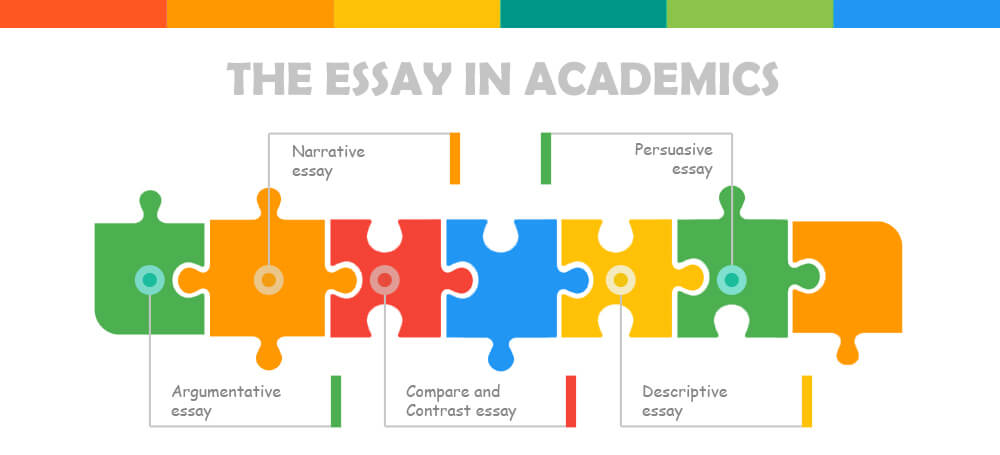

The Essay in Academics

Not only are students required to read a variety of essays during their academic education, but they will likely be required to write several different kinds of essays throughout their scholastic career. Don’t love to write? Then consider working with a ghost essay writer ! While all essays require an introduction, body paragraphs in support of the argumentative thesis statement, and a conclusion, academic essays can take several different formats in the way they approach a topic. Common essays required in high school, college, and post-graduate classes include:

Five paragraph essay

This is the most common type of a formal essay. The type of paper that students are usually exposed to when they first hear about the concept of the essay itself. It follows easy outline structure – an opening introduction paragraph; three body paragraphs to expand the thesis; and conclusion to sum it up.

Argumentative essay

These essays are commonly assigned to explore a controversial issue. The goal is to identify the major positions on either side and work to support the side the writer agrees with while refuting the opposing side’s potential arguments.

Compare and Contrast essay

This essay compares two items, such as two poems, and works to identify similarities and differences, discussing the strength and weaknesses of each. This essay can focus on more than just two items, however. The point of this essay is to reveal new connections the reader may not have considered previously.

Definition essay

This essay has a sole purpose – defining a term or a concept in as much detail as possible. Sounds pretty simple, right? Well, not quite. The most important part of the process is picking up the word. Before zooming it up under the microscope, make sure to choose something roomy so you can define it under multiple angles. The definition essay outline will reflect those angles and scopes.

Descriptive essay

Perhaps the most fun to write, this essay focuses on describing its subject using all five of the senses. The writer aims to fully describe the topic; for example, a descriptive essay could aim to describe the ocean to someone who’s never seen it or the job of a teacher. Descriptive essays rely heavily on detail and the paragraphs can be organized by sense.

Illustration essay

The purpose of this essay is to describe an idea, occasion or a concept with the help of clear and vocal examples. “Illustration” itself is handled in the body paragraphs section. Each of the statements, presented in the essay needs to be supported with several examples. Illustration essay helps the author to connect with his audience by breaking the barriers with real-life examples – clear and indisputable.

Informative Essay

Being one the basic essay types, the informative essay is as easy as it sounds from a technical standpoint. High school is where students usually encounter with informative essay first time. The purpose of this paper is to describe an idea, concept or any other abstract subject with the help of proper research and a generous amount of storytelling.

Narrative essay

This type of essay focuses on describing a certain event or experience, most often chronologically. It could be a historic event or an ordinary day or month in a regular person’s life. Narrative essay proclaims a free approach to writing it, therefore it does not always require conventional attributes, like the outline. The narrative itself typically unfolds through a personal lens, and is thus considered to be a subjective form of writing.

Persuasive essay

The purpose of the persuasive essay is to provide the audience with a 360-view on the concept idea or certain topic – to persuade the reader to adopt a certain viewpoint. The viewpoints can range widely from why visiting the dentist is important to why dogs make the best pets to why blue is the best color. Strong, persuasive language is a defining characteristic of this essay type.

The Essay in Art

Several other artistic mediums have adopted the essay as a means of communicating with their audience. In the visual arts, such as painting or sculpting, the rough sketches of the final product are sometimes deemed essays. Likewise, directors may opt to create a film essay which is similar to a documentary in that it offers a personal reflection on a relevant issue. Finally, photographers often create photographic essays in which they use a series of photographs to tell a story, similar to a narrative or a descriptive essay.

Drawing the line – question answered

“What is an Essay?” is quite a polarizing question. On one hand, it can easily be answered in a couple of words. On the other, it is surely the most profound and self-established type of content there ever was. Going back through the history of the last five-six centuries helps us understand where did it come from and how it is being applied ever since.

If you must write an essay, follow these five important steps to works towards earning the “A” you want:

- Understand and review the kind of essay you must write

- Brainstorm your argument

- Find research from reliable sources to support your perspective

- Cite all sources parenthetically within the paper and on the Works Cited page

- Follow all grammatical rules

Generally speaking, when you must write any type of essay, start sooner rather than later! Don’t procrastinate – give yourself time to develop your perspective and work on crafting a unique and original approach to the topic. Remember: it’s always a good idea to have another set of eyes (or three) look over your essay before handing in the final draft to your teacher or professor. Don’t trust your fellow classmates? Consider hiring an editor or a ghostwriter to help out!

If you are still unsure on whether you can cope with your task – you are in the right place to get help. HandMadeWriting is the perfect answer to the question “Who can write my essay?”

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

Understanding essay types

Introduction.

- Sample essays 1

- Sample essays 2

At university, you have to demonstrate the ability to write different types of essays. The aim of this unit is to study the style features of three main types of essays: expository, discussion and argumentative.

Although all university writing is essentially argumentative, most essays have elements of exposition, discussion and argument. A critical review or literature review , for example, may begin with a brief outline or summary of what the article or book is about and its relation to a particular field and the author's viewpoint, before discussing the weaknesses and strengths of the article.

At university, you do not just write your own opinion; your opinion is often an informed opinion , formed from reading and synthesising other people's opinions. You will then support your opinion or claims with evidence and relevant theory. At university, you do not just describe; you analyse, examine, explain, interpret, discuss, assess and evaluate.

In this unit, we will look at:

- some definitions of each essay type (expository, discussion, and argumentative)

- their characteristic features

- some sample essays

Definitions

While all academic essays have the same basic structure – they all begin with typical introductions, develop ideas in body paragraphs, and end with typical conclusions – there are variations in the style of delivery and organisation of the ideas to fit the purpose of the essay. You may find these broad dictionary meanings useful:

Sample discussion essays

The two sample discussion essays presented here represent varying degrees of discursive style. The first combines exposition with discussion; the second combines discussion with argument. Both essays demonstrate some basic principles of essay structure, including the construction of effective introductions, body paragraphs, and conclusions using the models explained in this unit.

Essay sample 1

Sample essay: Impact of iPods on the music retail industry and music consumption

The writing style has elements of exposition and argumentation. The tone is less assertive; the style is exploratory, but the discussion is built around a clear thesis or point of view stated in the introduction.

Answer the following questions:

Essay Sample 2: Language and Gender

This commentary on a literature review attempts to show how the writer of the review combines discussion with exposition, critical analysis and argumentative style (ie, concession and refutation). However, the annotations are not very easy to read; it might be useful to print out a hard copy to study it properly. At the end of the article, you can click on the original document without the comments.

Argumentative essays

Argumentative essays are about issues. They are written to support or refute (argue against) an opinion or claim in order to reach a decision. In terms of writing style, they are more forceful than a discursive essay, because they attempt to effect a change of opinion through reasoned discussion.

Some function words used in questions requiring argument include: Do you agree or disagree with ...? Should ...? Develop an argument for or againts this statement. Discuss the claim that .... To what extent do you agree or disagree with ...?

The language of argument

Academic arguments are characterised more by logical appeal than emotional appeal. If emotional appeal or language were used the writing would read more like a public speech or an oral debate than an academic argument. Avoid the following:

- subjective comments (eg, I believe ...)

- sweeping generalisations, absolute statements or exaggeration without solid evidence (eg, Everyone buys furniture from Trade Me .)