ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Job satisfaction, organizational commitment and job involvement: the mediating role of job involvement.

- Department of Industrial Engineering and Management, Faculty of Technical Sciences, University of Novi Sad, Novi Sad, Serbia

We conducted an empirical study aimed at identifying and quantifying the relationship between work characteristics, organizational commitment, job satisfaction, job involvement and organizational policies and procedures in the transition economy of Serbia, South Eastern Europe. The study, which included 566 persons, employed by 8 companies, revealed that existing models of work motivation need to be adapted to fit the empirical data, resulting in a revised research model elaborated in the paper. In the proposed model, job involvement partially mediates the effect of job satisfaction on organizational commitment. Job satisfaction in Serbia is affected by work characteristics but, contrary to many studies conducted in developed economies, organizational policies and procedures do not seem significantly affect employee satisfaction.

1. Introduction

In the current climate of turbulent changes, companies have begun to realize that the employees represent their most valuable asset ( Glen, 2006 ; Govaerts et al., 2011 ; Fulmer and Ployhart, 2014 ; Vomberg et al., 2015 ; Millar et al., 2017 ). Satisfied and motivated employees are imperative for contemporary business and a key factor that separates successful companies from the alternative. When considering job satisfaction and work motivation in general, of particular interest are the distinctive traits of these concepts in transition economies.

Serbia is a country that finds itself at the center of the South East region of Europe (SEE), which is still in the state of transition. Here transition refers to the generally accepted concept, which implies economic and political changes introduced by former socialist countries in Europe and beyond (e.g., China) after the years of economic stagnation and recession in the 1980's, in the attempt to move their economy from centralized to market-oriented principles ( Ratkovic-Njegovan and Grubic-Nesic, 2015 ). Serbia exemplifies many of the problems faced by the SEE region as a whole, but also faces a number of problems uniquely related to the legacy of its past. Due to international economic sanctions, the country was isolated for most of the 1990s, and NATO air strikes, related to the Kosovo conflict and carried out in 1999, caused significant damage to the industry and economy. Transitioning to democracy in October 2000, Serbia embarked on a period of economic recovery, helped by the introduction of long overdue reforms, major inflows of foreign investment and substantial assistance from international funding institutions and others in the international community. However, the growth model on which Serbia and other SEE countries relied between 2001 and 2008, being based mainly on rapid capital inflows, a credit-fueled domestic demand boom and high current account deficit (above 20% of GDP in 2008), was not accompanied by the necessary progress in structural and institutional reforms to make this model sustainable ( Uvalic, 2013 ). The central issue of the transition process in Serbia and other such countries is privatization of public enterprises, which in Serbia ran slowly and with a number of interruptions, failures and restarts ( Radun et al., 2015 ). The process led the Serbian industry into a state of industrial collapse, i.e., deindustrialization. Today there are less than 400,000 employees working in the industry in Serbia and the overall unemployment rate exceeds 26% ( Milisavljevic et al., 2013 ). The average growth of Serbia's GDP in the last 5 years was very low, at 0.6% per year, but has reached 2.7% in 2016 ( GDP, 2017 ). The structure of the GDP by sector in 2015 was: services 60.5%, industry 31.4%, and agriculture 8.2% ( Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, 2017 ).

Taking into account the specific adversities faced by businesses in Serbia, we formulated two main research questions as a starting point for the analysis of the problem of work motivation in Serbia:

1. To what extent are the previously developed models of work motivation (such as the model of Locke and Latham, 2004 ) applicable to the transition economy and business practices in Serbia?

2. What is the nature of the relationships between different segments of work motivation (job satisfaction, organizational commitment, job involvement and work characteristics)?

The Hawthorn experiment, conducted in early 1930s ( Mayo, 1933 ), spurred the interest of organizational behavior researchers into the problem of work motivation. Although Hawthorn focused mainly on the problems of increasing the productivity and the effects of supervision, incentives and the changing work conditions, his study had significant repercussions on the research of work motivation. All modern theories of work motivation stem from his study.

Building on his work, Maslow (1943) published his Hierarchy of Needs theory, which remains to this day the most cited and well known of all work motivation theories according to Denhardt et al. (2012) . Maslow's theory is a content-based theory , belonging to a group of approaches which also includes the ERG Theory by Alderfer (1969) , the Achievement Motivation Theory, Motivation-Hygiene Theory and the Role Motivation Theory.

These theories focus on attempting to uncover what the needs and motives that cause people to act in a certain way, within the organization, are. They do not concern themselves with the process humans use to fulfill their needs, but attempt to identify variables which influence this fulfillment. Thus, these theories are often referred to as individual theories , as they ignore the organizational aspects of work motivation, such as job characteristics or working environment, but concentrate on the individual and the influence of an individual's needs on work motivation.

The approach is contrasted by the process theories of work motivation, which take the view that the concept of needs is not enough to explain the studied phenomenon and include expectations, values, perception, as important aspects needed to explain why people behave in certain ways and why they are willing to invest effort to achieve their goals. The process theories include: Theory of Work and Motivation ( Vroom, 1964 ), Goal Setting Theory ( Locke, 1968 ), Equity Theory ( Adams, 1963 ), as well as the The Porter-Lawler Model ( Porter and Lawler, 1968 ).

Each of these theories has its limitations and, while they do not contradict each other, they focus on different aspects of the motivation process. This is the reason why lately they have been several attempts to create an integrated theory of work motivation, which would encompass all the relevant elements of different basic theories and explain most processes taking place within the domain of work motivation, the process of motivation, as well as employee expectations ( Donovan, 2001 ; Mitchell and Daniels, 2002 ; Locke and Latham, 2004 ). One of the most influential integrated theories is the theory proposed by Locke and Latham (2004) , which represents the basis for the study presented in this paper.

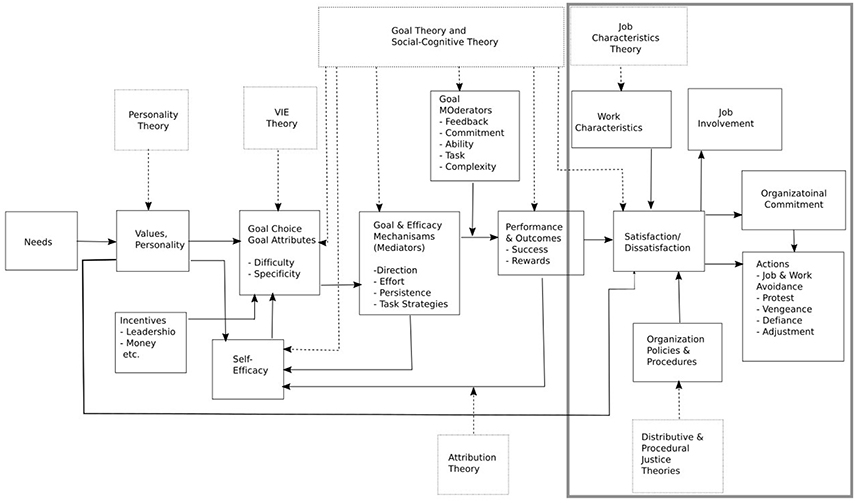

The model of Locke and Latham is show in Figure 1 . As the figure shows, it includes individual needs, values and motive, as well as personality. Incorporating the theory of expectations, the goal-setting theory and the social-cognitive theory, it focuses on goal setting, goals themselves and self-efficiency. Performance, by way of achievements and rewards, affects job satisfaction. The model defines relations between different constructs and, in particular, that job satisfaction is affected by the job characteristics and organizational policy and procedures and that it, in turn, affects organizational commitment and job involvement. Locke and Latham suggested that the theory they proposed needs more stringent empirical validation. In the study presented here, we take a closer look at the part of their theory which addresses the relationship between job satisfaction, involvement and organizational commitment. The results of the empirical study conducted in industrial systems suggest that this part of the model needs to be improved to reflect the mediating role of job involvement in the process through which job satisfaction influences organizational commitment.

Figure 1 . Diagram of the Latham and Locke model. The frame on the right indicates the part of the model the current study focuses on.

Job satisfaction is one of the most researched phenomena in the domain of human resource management and organizational behavior. It is commonly defined as a “pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of oneś job or job experiences” ( Schneider and Snyder, 1975 ; Locke, 1976 ). Job satisfaction is a key element of work motivation, which is a fundamental determinant of one's behavior in an organization.

Organizational commitment, on the other hand, represents the degree to which the employees identify with the organization in which they work, how engaged they are in the organization and whether they are ready leave it ( Greenberg and Baron, 2008 ). Several studies have demonstrated that there is a strong connection between organizational commitment, job satisfaction and fluctuation ( Porter et al., 1974 ), as well as that people who are more committed to an organization are less likely to leave their job. Organizational commitment can be thought of as an extension of job satisfaction, as it deals with the positive attitude that an employee has, not toward her own job, but toward the organization. The emotions, however, are much stronger in the case of organizational commitment and it is characterized by the attachment of the employee to the organization and readiness to make sacrifices for the organization.

The link between job satisfaction and organizational commitment has been researched relatively frequently ( Mathieu and Zajac, 1990 ; Martin and Bennett, 1996 ; Meyer et al., 2002 ; Falkenburg and Schyns, 2007 ; Moynihan and Pandey, 2007 ; Morrow, 2011 ). The research consensus is that the link exists, but there is controversy about the direction of the relationship. Some research supports the hypothesis that job satisfaction predicts organizational commitment ( Stevens et al., 1978 ; Angle and Perry, 1983 ; Williams and Hazer, 1986 ; Tsai and Huang, 2008 ; Yang and Chang, 2008 ; Yücel, 2012 ; Valaei et al., 2016 ), as is the case in the study presented in this paper. Other studies suggest that the organizational commitment is an antecedent to job satisfaction ( Price and Mueller, 1981 ; Bateman and Strasser, 1984 ; Curry et al., 1986 ; Vandenberg and Lance, 1992 ).

In our study, job involvement represents a type of attitude toward work and is usually defined as the degree to which one identifies psychologically with one's work, i.e., how much importance one places on their work. A distinction should be made between work involvement and job involvement. Work involvement is conditioned by the process of early socialization and relates to the values one has wrt. work and its benefits, while job involvement relates to the current job and is conditioned with the one's current employment situation and to what extent it meets one's needs ( Brown, 1996 ).

2.1. Research Method

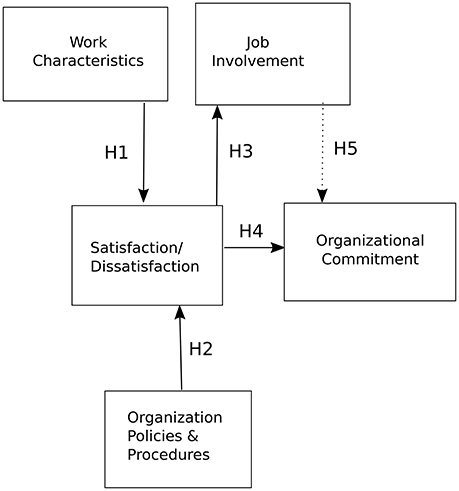

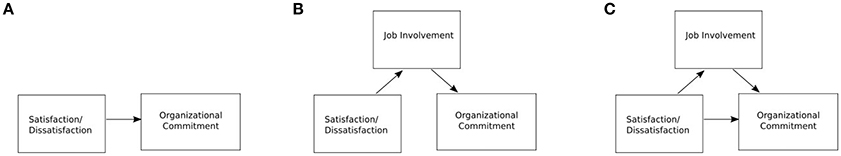

Based on the relevant literature, the results of recent studies and the model proposed by Locke and Latham (2004) , we designed a conceptual model shown in Figure 2 . The model was then used to formulate the following hypotheses:

H0 - Work motivation factors, such as organizational commitment, job involvement, job satisfaction and work characteristics, represent interlinked significant indicators of work motivation in the organizations examined.

H1 - Work characteristics will have a positive relationship with job satisfaction.

H2 - Organizational policies and procedures will have a positive relationship with job satisfaction.

H3 - Job satisfaction will have a positive relationship with job involvement.

H4 - Job satisfaction will have a positive relationship with organizational commitment.

H5 - Job involvement will have a mediating role between job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Figure 2 . The research model.

2.2. Participants

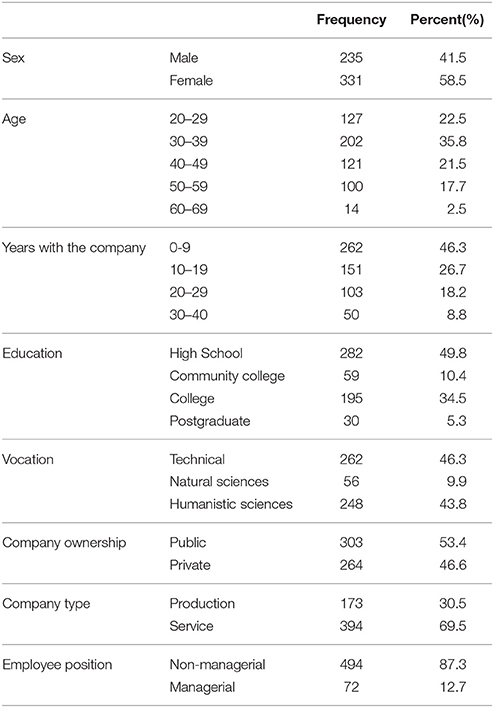

For the purpose of this study, 125 organizations from the Serbian Chamber of Commerce database ( www.stat.gov.rs ) were randomly selected to take part in this study. Each organization was contacted and an invitation letter was sent. Eight companies expressed a desire to take part and provided contact details for 700 of their employees. The questionnaire distribution process was conducted according to Dillman's approach ( Dillman, 2011 ). Thus, the initial questionnaire dissemination process was followed by a series of follow-up email reminders, if required. After a 2-month period, out of 625 received, 566 responses were valid. Therefore, the study included 566 persons, 235 males (42%) and 331 women (58%) employed by 8 companies located in Serbia, Eastern Europe.

The sample encompassed staff from both public (53%) and private (47%) companies in manufacturing (31%) and service (69%) industries. The companies were of varied size and had between 150 and 6,500 employees, 3 of them (37.5%) medium-sized (<250 employees) and 5 (62.5%) large enterprises.

For the sake of representativeness, the sample consisted of respondents across different categories of: age, years of work service and education. The age of the individuals was between 20 and 62 years of age and we divided them into 5 categories as shown in Table 1 . The table provides the number of persons per category and the relative size of the category wrt. to the whole sample. In the same table, a similar breakdown is shown in terms of years a person spent with the company, their education and the type of the position they occupy within the company (managerial or not).

Table 1 . Data sample characteristics.

2.3. Ethics Statement

The study was carried out in accordance with the Law on Personal Data Protection of the Republic of Serbia and the Codex of Professional Ethics of the University of Novi Sad. The relevant ethics committee is the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Technical Sciences of the University of Novi Sad.

All participants took part voluntarily and were free to fill in the questionnaire or not.

The questionnaire included a cover sheet explaining the aim of the research, ways in which the data will be used and the anonymous nature of the survey.

2.4. Measures

This study is based on a self reported questionnaire as a research instrument.

The questionnaire was developed in line with previous empirical findings, theoretical foundations and relevant literature recommendations ( Brayfield and Rothe, 1951 ; Weiss et al., 1967 ; Mowday et al., 1979 ; Kanungo, 1982 ; Fields, 2002 ). We then conducted a face validity check. Based on the results, some minor corrections were made, in accordance with the recommendations provided by university professors. After that, the pilot test was conducted with 2 companies. Managers from each of these companies were asked to assess the questionnaire. Generally, there were not any major complaints. Most of the questions were meaningful, clearly written and understandable. The final research instrument contained 86 items. For acquiring respondents' subjective estimates, a five-point Likert scale was used.

The questionnaire took about 30 min to fill in. It consisted of: 10 general demographic questions, 20 questions from the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ), 15 questions from the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ), 10 questions from the Job Involvement Questionnaire (JIQ), 18 questions of the Brayfield-Rothe Job Satisfaction Scale (JSS), 6 questions of the Job Diagnostic Survey (JDS) and 7 additional original questions related to the rules and procedures within the organization.

The Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ), 20 items short form ( Weiss et al., 1967 ), was used to gather data about job satisfaction of participants. The MSQ – short version items, are rated on 5-points Likert scale (1 very dissatisfied with this aspect of my job, and 5 – very satisfied with this aspect of my job) with two subscales measuring intrinsic and extrinsic job satisfaction.

Organizational commitment was measured using The Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ). It is a 15-item scale developed by Mowday, Steers and Porter ( Mowday et al., 1979 ) and uses a 5-point Likert type response format, with 3 factors that can describe this commitment: willingness to exert effort, desire to maintain membership in the organization, and acceptance of organizational values.

The most commonly used measure of job involvement has been the Job Involvement Questionnaire (JIQ, Kanungo, 1982 ), 10-items scale designed to assess how participants feel toward their present job. The response scale on a 5-point scale varied between “strongly disagree/not applicable to me” to “strongly agree/fully applicable”.

The Brayfield and Rothe's 18-item Job Satisfaction Index (JSI, Brayfield and Rothe, 1951 ) was used to measure overall job satisfaction, operationalized on five-point Likert scale.

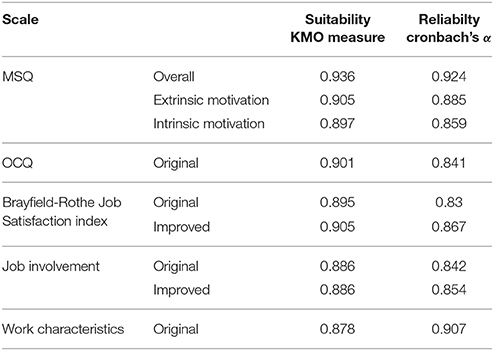

Psychometric analysis conducted showed that all the questionnaires were adequately reliable (Cronbach alpha > 0.7). The suitability of the data for factor analysis has been confirmed using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Test (see Table 2 ).

Table 2 . Basic psychometric characteristics of the instruments.

For further analysis we used summary scores for the different scales. Job satisfaction was represented with the overall score of MSQ, as the data analysis revealed a strong connection between the extrinsic and intrinsic motivators. The overall score on the OCQ was used as a measure of organizational commitment, while the score on JDS was used to reflect job characteristics. The JSS and JIQ scales have been modified, by eliminating a few questions, in order to improve reliability and suitability for factor analysis.

Statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS software. The SPSS Amos structural equation modeling software was used to create the Structural Equation Models (SEMs).

The data was first checked for outliers using box-plot analysis. The only outliers identified were related to the years of employment, but these seem to be consistent to what is expected in practice in Serbia, so no observations needed to be removed from the dataset.

3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

Although research dimensions were empirically validated and confirmed in several prior studies, to the best of our knowledge, the empirical confirmation of the research instrument (i.e., questionnaire) and its constituents in the case of Serbia and South-Eastern Europe is quite scarce. Furthermore, the conditions in which previous studies were conducted could vary between research populations. Also, such differences could affect the structure of the research concepts. Thus, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted in order to empirically validate the structure of research dimensions and to test the research instrument, within the context of the research population of South-Eastern Europe and Serbia.

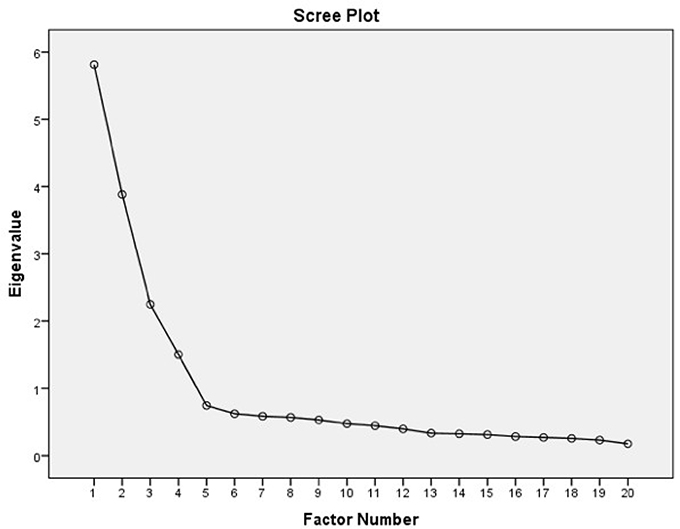

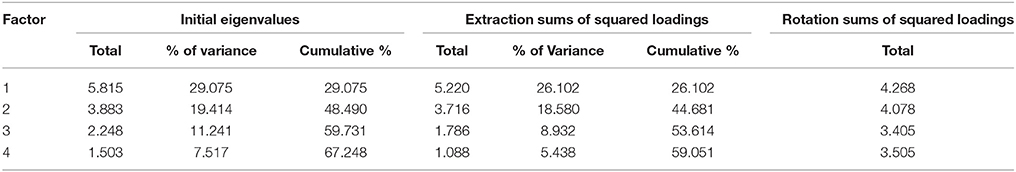

Using the maximum likelihood method we identified four factors, which account for 67% of the variance present in the data. The scree plot of the results of the analysis is shown in Figure 3 . As the figure shows, we retained the factors above the inflection point.

Figure 3 . Scree plot of the EFA results.

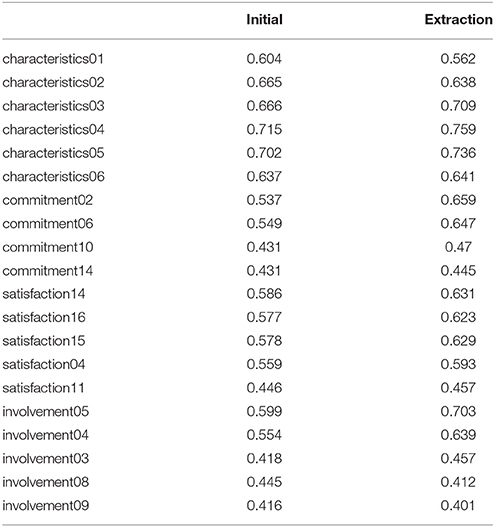

The communalities for the variables loading into the factors are shown in Table 3 and the questions corresponding to our variables are listed in Table 4 . Initial communalities are estimates of the proportion of variance in each variable accounted for by all components (factors) identified, while the extraction communalities refer to the part of the variance explained by the four factors extracted. The model explains more of the variance then the initial factors, for all but the last variable.

Table 3 . Communalities.

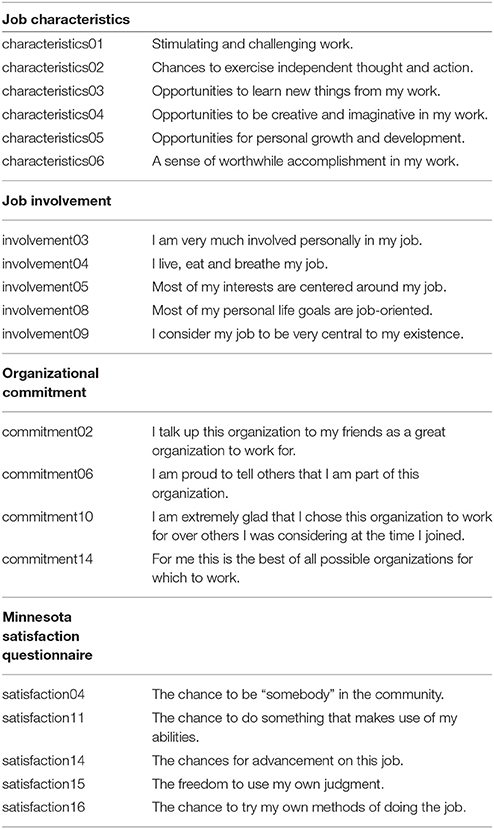

Table 4 . Questions that build our constructs.

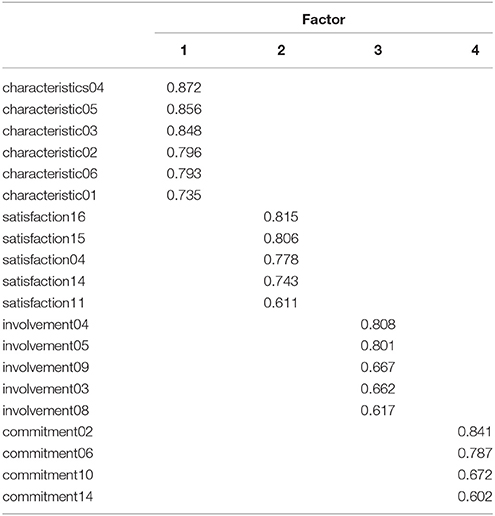

More detailed results of the EFA for the four factors, are shown in Table 5 . The unique loadings of specific items measured with the different questions in the questionnaire on the factors identified are shown in the pattern matrix (Table 6 ). As the table shows, each factor is loaded into by items that were designed to measure a specific construct and there are no cross-loadings. The first factor corresponds to job characteristics, second to job satisfaction, third to job involvement and the final to organizational commitment. The correlation between the factors is relatively low and shown in Table 7 .

Table 5 . Total variance explained by the dominant factors.

Table 6 . Pattern matrix for the factors identified.

Table 7 . Factor correlation matrix.

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

In the next part of our analysis we used Structural Equation Modeling to validate and improve a part of the model proposed by Locke and Latham (2004) that focuses on work characteristics, job satisfaction, organizational commitment and job involvement.

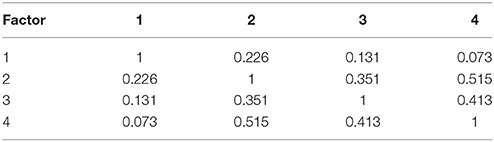

Although the EFA suggest the existence of four, not five, dominant factors in the model, diverging from the model proposed by Locke and Latham (2004) , in our initial experiments we used their original model, shown in Figure 4A , taking into account also organizational policies and procedures.

Figure 4 . The evolution of our model (the path coefficients are standardized): (A) the initial model based on Locke and Latham (2004) , (B) no partial mediation, and (C) partial mediation introduced.

In this (default) model, the only independent variable are the job characteristics. The standardized regression coefficients shown in Figure 4A (we show standardized coefficients throughout Figure 4 ) indicate that the relationship between the satisfaction and organizational commitment seems to be stronger (standard coefficient value of 0.54) than the one between satisfaction and involvement (standard coefficient value of 0.37). The effect of job characteristics and policies and procedures on the employee satisfaction seems to be balanced (standard coefficient values of 0.31 and 0.30, respectively).

The default model does not fit our data well. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) for this model is 0.759, the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) is 0.598, while the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) is 0.192.

A more detailed analysis of the model revealed that it could indeed (as the EFA suggests) be improved by eliminating the organizational policies and procedures variable, as it has a high residual covariance with job involvement (−3.071) and organizational commitment (−4.934).

We therefore propose to eliminate the “Organizational policies and procedures” variable from the model. Dropping the variable resulted in an improved model shown in Figure 4B . The improved model fits the data better, but the fit is still not good ( RMSEA = 0.125, CFI = 0.915 and TLI = 0.830).

We then hypothesized that job involvement influences organizational commitment, yielding the final model tested in this study (Figure 4C ). This model turned out to be the one that fits our data very well ( RMSEA = 0.000, CFI = 1 and TLI = 1.015).

4. Mediation Analysis

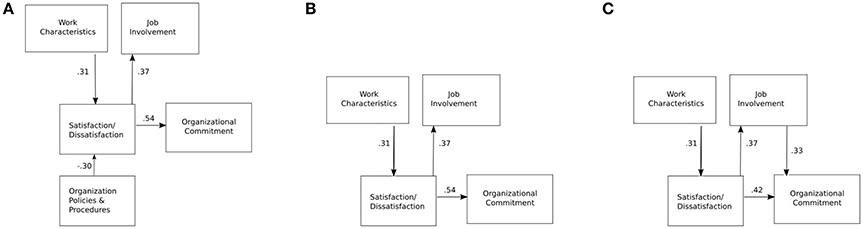

In the final part of the study we conducted the mediation analysis, to understand the relationship between job satisfaction, job involvement and organizational commitment. We used bootstrapping, based on 5000 samples and the confidence interval of 95%.

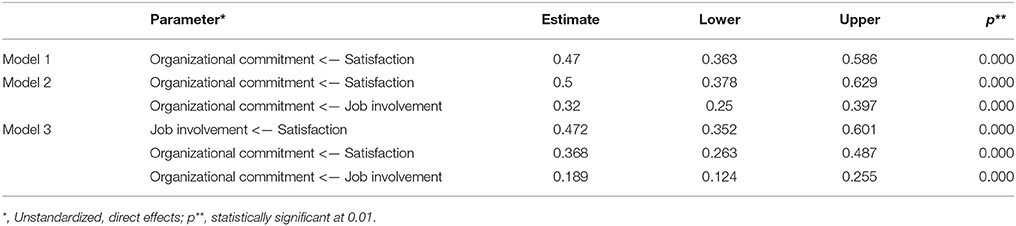

We started with a model that contains just one relation between satisfaction and commitment (Figure 5A ), then tested for full mediation (Figure 5B ) and finally partial mediation as indicated in out proposed model (Figure 5C ). The unstandardized, direct effect regression weights and the p -values obtained in these experiments are shown in Table 8 . As the p -values show, all the connections in our three models are significant and that they remain so throughout the evolution of the model. Therefore, job involvement mediates the influence of satisfaction on organizational commitment, but this is a partial mediation and a major part of the effect of satisfaction on the organizational commitment is achieved directly.

Figure 5 . Mediation analysis models. (A) , Model 1; (B) , Model 2; (C) , Model 3.

Table 8 . Mediation analysis regression weights.

5. Discussion

We conducted an empirical study aimed at exploring the relationship between employee satisfaction, job involvement, organizational commitment, work characteristics and organizational policies and procedures.

Based on the relevant scientific literature, recent studies in the area and the integrative model of work motivation of Locke and Latham (2004) , we have formulated an initial conceptual model for our research and hypothesized the connections between the relevant variables. The initial model has been improved iteratively, with the goal of increasing its fit to the empirical data collected in the study.

Starting from the model proposed by Locke and Latham (2004) we determined that their model does not fit our experimental data well and that we observe a connection between job involvement that is not present in their model. In addition, our data does not support the hypothesis that organizational procedures and policies affect employee satisfaction in the organizations considered. As a result we propose a 4 factor model shown in Figure 4C for the relationship between the concepts of work characteristics, employee satisfaction, job involvement and organizational commitment.

We analyzed the results of the study based on 1 general and 5 specific hypotheses. The research confirms that there is a link between work characteristics and job satisfaction (H1), but that it is weak, suggesting that a dominant effect of the material factors of motivation exists.

We have also determined that there is a connection between the rules and procedures variable (H2) and the rest of the variables, indicating that it should be considered in future studies, but that the constructs need to be operationalized better.

The third specific hypothesis (H3) that job satisfaction has a positive relationship with job involvement has been confirmed and we have observed that extrinsic work motivation has a stronger effect than intrinsic, which can be explained by low wages and insufficient funds for everyday life. Other research has confirmed this link ( Govender and Parumasur, 2010 ) and showed that most of the employee motivation dimensions have significant links with the dimensions of job involvement (9 out of 10 pairs).

The fourth specific hypothesis (H4 - Job satisfaction will have a positive relationship with organizational commitment) has also been confirmed and we can conclude that a positive relationship exists, which is in line with recent research in this area. The subscale focused on identification with the organization is strongly connected with both intrinsic and extrinsic factors of job satisfaction, but this cannot be said for the subscale focused on organizational attachment. Our research supports the existence of a weak connection between job satisfaction and organizational attachment, both when intrinsic and extrinsic satisfaction is considered as a motivator. A study of work motivation and organizational commitment conducted in Bulgaria (Serbia's neighbor) showed that extrinsic factors are key sources of organizational commitment ( Roe et al., 2000 ), as well as that job involvement and the chances for the fulfillment o higher-order needs pay a very important part in the motivation of the employees.

One of the reasons for such a result can be the economic situation in Serbia, which has a severely detrimental effect on work motivation. The transition and economic crisis is accompanied by the shrinking purchasing power of the population, higher unemployment rates and a rising disparity in the salary levels, all of which causes the adjustment of the behavior of the employees to these conditions. Under the economic conditions that exist in Serbia it is to be expected that the individuals will put more value on the salary and advancement prospects than on the opportunities for growth and development, which do not present a direct financial benefit.

The research did not reveal any differences with respect to the sex of the participants, regardless of the variable considered. Other research has not reached a consensus on the matter, as a part of the studies suggests that there are differences in job involvement between men and women ( Lodahl and Kejnar, 1965 ; Hall and Mansfield, 1975 ; Rabinowitz and Hall, 1977 ; Saal, 1978 ).

Regarding the ownership of the organizations examined, the research revealed statistically significant differences between the employees working in public and private companies, i.e., that the participants working in the private sector scores significantly higher on every variable except work characteristics, meaning that they are more committed to work, more involved and more satisfied.

In addition, we have determined that there are statistically significant differences when it comes to the position of the employees in the organization's hierarchy, i.e., whether they occupy a managerial or a non-managerial position. The study shows that managers have higher scores for organizational attachment, organizational commitment, intrinsic motivators, extrinsic motivators, job satisfaction and job involvement. We can, therefore, conclude that the managers are more satisfied with their work in general and that they are more committed to the organization than other employees. This can be explained by the fact that, due to the nature of the work they do, they are able to make decisions, they have a more varied job and have better material and non-material rewards. A more detailed analysis of the commitment of the managers, focused on identifying if we are dealing with normative, continuous or affective commitment would provide more insight into the structure and nature of the relationship between the organization and the individual.

Considering the type of the company (manufacturing or service) our study showed that the participants working in manufacturing companies are the ones who identify more with the company, are more committed to the company, more satisfied with their work and more involved.

Our study also identified a significant difference with respect to the vocation of the participants, showing that those with training in humanistic sciences awarded most positive scores to the characteristics of their work, while the opposite was true for those of technical vocations.

The part of our analysis focused on the age of the participants revealed that there is a statistically significant connection between the age and job satisfaction, where the older the employee, the less satisfied he/she is with their job and cares less about the characteristics of work. A reason for such a result could again be found in the economic situation of Serbia and the high unemployment rate (over 20%), causing the younger people to be satisfied with the simple fact that they managed to get a job, rather than being satisfied with the job itself. Another reason could be the difference in the perception of desires and possibilities that exists between the younger and older employees.

The years with the company are negatively linked with employee satisfaction, as well as job characteristics, which is in line with the effect discussed in the previous paragraph, as those with more time spent in the company are less satisfied with their job and care less about the characteristics of their work.

Considering the level of education of the participants, our study showed that the more educated the employees are, the less involved they are in their work and that they seem to care more about the characteristics of their work.

Our research showed that links exist between all the variables studied and that the weakest of these links is between work characteristics and other constructs. Of those, the weakest link in turn is the link between the work characteristics and the subscale of organizational commitment related to the identification with the organization. Thus, we can conclude that work characteristics do not exhibit a significant influence on whether and to what extent the employee will identify with the organization in which he/she works, i.e., whether he/she will be committed to the organization.

A moderate to strong connection exists between organizational commitment and job satisfaction, which is in line with the results of numerous previous studies ( Currivan, 1999 ; Meyer et al., 2002 ; Malhotra and Mukherjee, 2004 ; Saari and Judge, 2004 ; Chen, 2007 ; Falkenburg and Schyns, 2007 ; Moynihan and Pandey, 2007 ; Getahun et al., 2008 ; Colakoglu et al., 2010 ; Yücel, 2012 ; Fu and Deshpande, 2014 ).

Our study confirms the existence of a strong connection between job satisfaction and job involvement ( Moynihan and Pandey, 2007 ; Wegge et al., 2007 ; Griffin et al., 2010 ; Raymond and Mjoli, 2013 ; Zopiatis et al., 2014 ). Many studies have been carried out in an attempt to examine and define the relationship between job involvement and organizational commitment. Our results are in line with previous studies, which diverge only on the strength of the connection, ranging from moderate to strong ( Blau and Boal, 1989 ; Brewer and Lok, 1995 ; Sjöberg and Sverke, 2000 ; Brooks and Swailes, 2002 ; Toga, 2011 ). Our study provides more evidence for the existence of such a relationship, which is moderately strong. Such a relationship does not exist in the integrative model of Locke and Latham (2004) , which served as a starting point for this study.

In addition, we have determined that job involvement has a mediating role between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Job involvement mediates the influence of satisfaction on organizational commitment, but this is a partial mediation and a major part of the effect of satisfaction on the organizational commitment is achieved directly.

The construct related to organizational policies and procedures seems not to have significant bearing on employee satisfaction, based on the data collected. Two plausible explanations exist for this. The first is the fact that this was the only construct in our study for which a suitable standard questionnaire could not be found, so one had to be constructed specifically, meaning that the construct should be operationalized better in future studies and that this represents the limitation of our study. The other is the fact that in Serbia, as in most transition economies, the lack of suitable institutional and legislative framework at the national level is often accompanied with lax, not clearly defined and even less adhered-to business policies and procedures. In such a state of affairs, the employees seldom have a relatively clear idea of what the policies and procedures of their organization are and are unable to evaluate them with respect to those of other organizations, making this construct very hard to measure. At the same time it can be argued that, in such a situation, the policies and procedures are not perceived by the employees as a significant factor of their organizational behavior and indeed do not affect their work motivation. Whatever the reason, the relationship of policies and procedures to the other variables of work motivation within the transition economies merits further investigation.

Author Contributions

JĆ and SM designed the study. JĆ collected the data and conducted the bulk of the research. MD and DĆ conducted the statistical analysis and modeling. All authors took part in the manuscript writing, led by JĆ and DĆ.

The research leading to these results has received funding from the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2012-2016/ under REA grant agreement n° 295220.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Adams, J. S. (1963). Towards an understanding of inequity. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 67:422.

Google Scholar

Alderfer, C. P. (1969). An empirical test of a new theory of human needs. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 4, 142–175. doi: 10.1016/0030-5073(69)90004-X

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Angle, H. L., and Perry, J. L. (1983). Organizational commitment: individual and organizational influences. Work Occupat. 10, 123–146. doi: 10.1177/0730888483010002001

Bateman, T. S., and Strasser, S. (1984). A longitudinal analysis of the antecedents of organizational commitment. Acad. Manag. J. 27, 95–112. doi: 10.2307/255959

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Blau, G., and Boal, K. (1989). Using job involvement and organizational commitment interactively to predict turnover. J. Manag. 15, 115–127. doi: 10.1177/014920638901500110

Brayfield, A. H., and Rothe, H. F. (1951). An index of job satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 35:307.

Brewer, A. M., and Lok, P. (1995). Managerial strategy and nursing commitment in australian hospitals. J. Adv. Nurs. 21, 789–799. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.21040789.x

Brooks, I., and Swailes, S. (2002). Analysis of the relationship between nurse influences over flexible working and commitment to nursing. J. Adv. Nurs. 38, 117–126. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02155.x

Brown, S. P. (1996). A meta-analysis and review of organizational research on job involvement. Psychol. Bull. 120, 235–255. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.2.235

Chen, Y.-J. (2007). Relationships among service orientation, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment in the international tourist hotel industry. J. Amer. Acad. Business 11, 71–82.

Colakoglu, U., Culha, O., and Atay, H. (2010). The effects of perceived organisational support on employees'affective outcomes: evidence from the hotel industry. Tourism Hospital. Manag. 16, 125–150.

Currivan, D. B. (1999). The causal order of job satisfaction and organizational commitment in models of employee turnover. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 9, 495–524. doi: 10.1016/S1053-4822(99)00031-5

Curry, J. P., Wakefield, D. S., Price, J. L., and Mueller, C. W. (1986). On the causal ordering of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Acad. Manag. J. 29, 847–858. doi: 10.2307/255951

Denhardt, R. B., Denhardt, J. V., and Aristigueta, M. P. (2012). Managing Human Behavior in Public and Nonprofit Organizations . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Dillman, D. A. (2011). Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method–2007 Update with New Internet, Visual, and Mixed-Mode Guide . New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Donovan, J. J. (2001). Work motivation. Handb. Indust. Work Organ. Psychol. 2, 53–76. doi: 10.4135/9781848608368.n4

Falkenburg, K., and Schyns, B. (2007). Work satisfaction, organizational commitment and withdrawal behaviours. Manag. Res. News 30, 708–723. doi: 10.1108/01409170710823430

Fields, D. L. (2002). Taking the Measure of Work: A Guide to Validated Scales for Organizational Research and Diagnosis . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Fu, W., and Deshpande, S. P. (2014). The impact of caring climate, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment on job performance of employees in a china's insurance company. J. Business Ethics 124, 339–349. doi: 10.1007/s10551-013-1876-y

Fulmer, I. S., and Ployhart, R. E. (2014). “Our most important asset” a multidisciplinary/multilevel review of human capital valuation for research and practice. J. Manag. 40, 161–192.

GDP (2017). GDP Growth . Available online at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?end=2016&locations=RS&start=1996&view=chart (Accessed December 14, 2017).

Getahun, S., Sims, B., and Hummer, D. (2008). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment among probation and parole officers: a case study. Professional Issues Crim. Just. 3, 1–16.

Glen, C. (2006). Key skills retention and motivation: the war for talent still rages and retention is the high ground. Indust. Commer. Train. 38, 37–45. doi: 10.1108/00197850610646034

Govaerts, N., Kyndt, E., Dochy, F., and Baert, H. (2011). Influence of learning and working climate on the retention of talented employees. J. Workplace Learn. 23, 35–55. doi: 10.1108/13665621111097245

Govender, S., and Parumasur, S. B. (2010). The relationship between employee motivation and job involvement. South Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 13, 237–253. doi: 10.4102/sajems.v13i3.102

Greenberg, J., and Baron, R. A. (2008). Behavior in Organizations: Understanding and Managing the Human Side of Work. Upper saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Griffin, M. L., Hogan, N. L., Lambert, E. G., Tucker-Gail, K. A., and Baker, D. N. (2010). Job involvement, job stress, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment and the burnout of correctional staff. Crim. Just. Behav. 37, 239–255. doi: 10.1177/0093854809351682

Hall, D. T., and Mansfield, R. (1975). Relationships of age and seniority with career variables of engineers and scientists. J. Appl. Psychol. 60:201.

Kanungo, R. N. (1982). Measurement of job and work involvement. J. Appl. Psychol. 67:341.

Locke, E. A. (1976). “The nature and causes of job satisfaction,” in Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology , ed M. D. Dunnette (Chicago, IL: Rand McNally), 1297–1349.

Locke, E. A. (1968). Toward a theory of task motivation and incentives. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 3, 157–189. doi: 10.1016/0030-5073(68)90004-4

Locke, E. A., and Latham, G. P. (2004). What should we do about motivation theory? Six recommendations for the twenty-first century. Acad. Manag. Rev. 29, 388–403. doi: 10.5465/AMR.2004.13670974

Lodahl, T. M., and Kejnar, M. (1965). The definition and measurement of job involvement. J. Appl. Psychol. 49:24.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Malhotra, N., and Mukherjee, A. (2004). The relative influence of organisational commitment and job satisfaction on service quality of customer-contact employees in banking call centres. J. Serv. Market. 18, 162–174. doi: 10.1108/08876040410536477

Martin, C. L., and Bennett, N. (1996). The role of justice judgments in explaining the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Group Organ. Manag. 21, 84–104. doi: 10.1177/1059601196211005

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 50:370.

Mathieu, J. E., and Zajac, D. M. (1990). A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychol. Bull. 108:171.

Mayo, E. (1933). The Human Problems of an Industrial Organization . New York, NY: McMillan.

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., and Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: a meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 61, 20–52. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

Milisavljevic, S., Mitrovic, S., and Konja, V. (2013). “Serbian reindustrialization as a chance for better tomorrow opportunities and threats from customers perspective,” in Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference “Deindustrialization: Phenomena, Consequences” (Novi Sad: Faculty of Technical Sciences), 173–182.

Millar, C. C. J. M., Chen, S., and Waller, L. (2017). Leadership, knowledge and people in knowledge-intensive organisations: implications for HRM theory and practice. Int. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 28, 261–275. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2016.1244919

Mitchell, T. R., and Daniels, D. (2002). “Motivation,” in Handbook of Psychology , Vol. 12, eds W. Borman, D. Ilgen, and R. Klimoski (New York, NY: Wiley), 225–254. doi: 10.1002/0471264385.wei1210

Morrow, P. C. (2011). Managing organizational commitment: insights from longitudinal research. J. Vocat. Behav. 79, 18–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.12.008

Mowday, R. T., Steers, R. M., and Porter, L. W. (1979). The measurement of organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 14, 224–247. doi: 10.1016/0001-8791(79)90072-1

Moynihan, D. P., and Pandey, S. K. (2007). Finding workable levers over work motivation: comparing job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment. Admin. Soc. 39, 803–832. doi: 10.1177/0095399707305546

Porter, L. W., and Lawler, E. E. (1968). Management Attitudes and Performance . Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin Company.

Porter, L. W., Steers, R. M., Mowday, R. T., and Boulian, P. V. (1974). Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. J. Appl. Psychol. 59:603.

Price, J. L., and Mueller, C. W. (1981). A causal model of turnover for nurses. Acad. Manag. J. 24, 543–565. doi: 10.2307/255574

Rabinowitz, S., and Hall, D. T. (1977). Organizational research on job involvement. Psychol. Bull. 84:265.

Radun, V., Dragic, R., and Curcic, R. (2015). “Transition, institutions and neoinstitutionalism,” in Institutional Assumptions about Socio-Economic Dynamics in East and Central Europe-Proceedings , Vol. 1 (Novi Sad), 91–106.

Ratkovic-Njegovan, B., and Grubic-Nesic, L. (2015). “Transition, institutions and neoinstitutionalism,” in Institutional Assumptions about Socio-Economic Dynamics in East and Central Europe-Proceedings , Vol. 1 (Novi Sad), 107–122.

Raymond, T., and Mjoli, T. (2013). The relationship between job involvement, job satisfaction and organizational commitment among lower-level employees at a motor-car manufacturing company in East London, South Africa. J. Business Econ. Manag. 6, 25–35.

Roe, R., Zinovieva, I., Dienes, E., and Ten Horn, L. (2000). A comparison of work motivation in bulgaria, hungary, and the netherlands: test of a model. Appl. Psychol. 49, 658–687. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00039

Saal, F. E. (1978). Job involvement: a multivariate approach. J. Appl. Psychol. 63:53.

Saari, L. M., and Judge, T. A. (2004). Employee attitudes and job satisfaction. Hum. Resour. Manag. 43, 395–407. doi: 10.1002/hrm.20032

Schneider, B., and Snyder, R. A. (1975). Some relationships between job satisfaction and organization climate. J. Appl. Psychol. 60:318.

Sjöberg, A., and Sverke, M. (2000). The interactive effect of job involvement and organizational commitment on job turnover revisited: a note on the mediating role of turnover intention. Scand. J. Psychol. 41, 247–252. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00194

Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia (2017). Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Serbia . Belgrade.

Stevens, J. M., Beyer, J. M., and Trice, H. M. (1978). Assessing personal, role, and organizational predictors of managerial commitment. Acad. Manag. J. 21, 380–396. doi: 10.2307/255721

Toga, R. (2011). The Relationship between Job Involvement, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment Among Lower-Level Employees at Mercedes Benz South Africa . Doctoral dissertation, University of Fort Hare.

Tsai, M.-T., and Huang, C.-C. (2008). The relationship among ethical climate types, facets of job satisfaction, and the three components of organizational commitment: a study of nurses in Taiwan. J. Business Ethics 80, 565–581. doi: 10.1007/s10551-007-9455-8

Uvalic, M. (2013). “Why has serbia not been a frontrunner?,” in Handbook of the Economics and Political Economy of Transition , eds P. Hare and G. Turley (London; New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis), 365–375.

Valaei, N., Valaei, N., Rezaei, S., and Rezaei, S. (2016). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment: an empirical investigation among ICT-SMEs. Manag. Res. Rev. 39, 1663–1694. doi: 10.1108/MRR-09-2015-0216

Vandenberg, R. J., and Lance, C. E. (1992). Examining the causal order of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. J. Manag. 18, 153–167. doi: 10.1177/014920639201800110

Vomberg, A., Homburg, C., and Bornemann, T. (2015). Talented people and strong brands: the contribution of human capital and brand equity to firm value. Strat. Manag. J. 36, 2122–2131. doi: 10.1002/smj.2328

Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and Motivation . Oxford, UK: Wiley.

Wegge, J., Schmidt, K.-H., Parkes, C., and Dick, R. (2007). Taking a sickie: job satisfaction and job involvement as interactive predictors of absenteeism in a public organization. J. Occupat. Organ. Psychol. 80, 77–89. doi: 10.1348/096317906X99371

Weiss, D. J., Dawis, R. V., and England, G. W. (1967). Manual for the minnesota satisfaction questionnaire. Minnesota Stud. Vocat. Rehabil . 22.

Williams, L. J., and Hazer, J. T. (1986). Antecedents and consequences of satisfaction and commitment in turnover models: a reanalysis using latent variable structural equation methods. J. Appl. Psychol. 71:219.

Yang, F.-H., and Chang, C.-C. (2008). Emotional labour, job satisfaction and organizational commitment amongst clinical nurses: a questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 45, 879–887. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.02.001

Yücel, İ. (2012). Examining the relationships among job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention: an empirical study. Int. J. Business Manag. 7:44. doi: 10.5539/ijbm.v7n20p44

CrossRef Full Text

Zopiatis, A., Constanti, P., and Theocharous, A. L. (2014). Job involvement, commitment, satisfaction and turnover: evidence from hotel employees in cyprus. Tourism Manag. 41, 129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2013.09.013

Keywords: work, job, satisfaction, involvement, employee, commitment, organizational, behavior

Citation: Ćulibrk J, Delić M, Mitrović S and Ćulibrk D (2018) Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment and Job Involvement: The Mediating Role of Job Involvement. Front. Psychol . 9:132. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00132

Received: 07 November 2017; Accepted: 29 January 2018; Published: 16 February 2018.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2018 Ćulibrk, Delić, Mitrović and Ćulibrk. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Milan Delić, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IResearchNet

Job Involvement

Job involvement refers to a state of psychological identification with work—or the degree to which a job is central to a person’s identity. From an organizational perspective, it has been regarded as the key to unlocking employee motivation and increasing productivity. From an individual perspective, job involvement constitutes a key to motivation, performance, personal growth, and satisfaction in the workplace. Job involvement contributes importantly to organizational effectiveness, productivity, and morale by engaging employees deeply in their work and making it a meaningful and fulfilling experience. People become involved in their jobs when they perceive in them the potential for satisfying salient psychological needs (e.g., for growth, achievement, meaning, recognition, and security).

Job involvement enhances individuals’ work performance by motivating them to exert greater effort and use their creativity to solve problems and work intelligently. Job involvement and the benefits that flow from it result partly from personality and characteristics of the individual and partly from organizational context, job design, and supervisory behavior. Individuals who possess certain personality traits (e.g., internal locus of control, need for achievement, work ethic endorsement) are likely to be predisposed to become job involved. On the other hand, situational factors such as job design, organizational and psychological climate, and management style all have important influences on employee job involvement. Job design factors appear to have a stronger influence on job involvement for individuals who have a stronger drive to satisfying higher-order psychological needs (i.e., higher-order need strength).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code, profile of the job-involved individual.

Based on a systematic review of the voluminous research on job involvement, a profile of the personal characteristics of highly job-involved individuals emerges. In terms of personality traits, job-involved people tend to be high in both internal motivation and self-esteem and to subscribe to a work ethic consistent with the view that the experience of work has value as an end in itself. In terms of demographics, however, job involvement does not depend on age, gender, education, length of service to the organization, or salary.

Job-involved individuals find work meaningful and challenging, work at complex tasks employing a variety of skills, and see complete units of work through to their completion. They participate in the setting of performance standards and maintain positive relationships with supervisors who provide them with ample performance feedback. Beyond commitment to the immediate job, job-involved people are also strongly committed to work in general and career achievement and advancement.

People who are high in job involvement typically experience high job satisfaction, especially with the content of the work, which they find intrinsically satisfying. Their job satisfaction prevails even when their supervisor lacks consideration or is uncommunicative or autocratic. Job-involved individuals tend to have strong affective ties to the organization and, as a result, are less likely than others to consider leaving it.

In general, job involvement does not appear to entail systematic negative side effects, such as psychological, social, or physical maladies resulting from strong identification with one’s job. Stress, anxiety, somatic health complaints, and work-family conflict do not appear to be systematically related to job involvement. On the other hand, job-involved individuals do not appear to be more satisfied with life in general than less job-involved individuals or especially likely to be highly involved in other activities outside of work.

Means of Fostering Job Involvement

As this profile of job-involved individuals suggests, promoting job involvement effectively can constitute a key to competitive advantage in the marketplace for organizations. Research suggests two closely related types of organizational factors that tend to promote job involvement and motivate effort toward achievement of organizational goals: psychological climate and human resource policies and practices.

Psychological Climate

Psychological climate refers to the manner in which organizational environments are perceived by their employees. More specifically, it refers to the way employees interpret features of the environment in relation to their own goals, values, and concerns for personal well-being. Two dimensions of psychological climate that have been strongly linked to job involvement are psychological safety and meaningfulness. Employees tend to perceive their work environment as conducive to the attainment of their needs and goals to the extent that they experience it as being psychologically safe and meaningful. Employee perceptions of the workplace as being psychologically safe and meaningful tend to be strongly and positively correlated, and both are strongly linked to job involvement and employee effort.

Psychological safety . Perceptions of the work environment as psychologically safe are rooted in three elements: supportive management, role clarity, and self-expression. A supportive management style allows employees to strive and possibly fail without fear of reprisals. It gives employees control over the methods they use to perform their work and allows them to bring their creativity to bear on work problems. Clear expectations and predictable, consistent work norms promote psychological safety and job involvement. And when employees feel free to express aspects of their individuality at work, they are likely to internalize the work role, personalize it, and treat it as a core aspect of the self-concept.

Meaningfulness . Employees perceive their work environment as psychologically meaningful when they regard it as challenging, worthwhile, and rewarding. Individuals find their work particularly meaningful when they have a clear sense of the contribution it makes toward the attainment of organizational goals. Similarly, the perceived meaningfulness of work increases to the extent that employees perceive their work as challenging and conducive to learning and attainment of mastery. Also, receiving recognition and rewards commensurate with one’s contributions tends to increase perceived meaningfulness of work.

Human Resource Policies and Practices

Human resource policies and practices are closely related to psychological climate and have important effects on job involvement, productivity, and organizational performance. Whereas psychological climate relates to individuals’ perceptions of how the organizational environment affects their own goals, status, and well-being, human resource practices represent concrete policies and actions of the organization with respect to their employees. Research by Jeffrey Pfeffer and Mark Huselid indicates the following human resources practices as keys to high employee involvement motivation and performance:

Hiring selectively . Individuals differ in the values and attitudes they hold and express, as well as on a great variety of other characteristics. The companies that are most successful in promoting job involvement tend to attract rich pools of job applicants, from which they are able to select those who best reflect the goals and values of the organization. In essence, they endeavor to select the small proportion of applicants with the greatest predisposition to be highly job-involved, motivated, and productive.

Training . Firms that effectively promote job involvement tend to do an unusually thorough job of training employees. In these companies, training is ongoing and continuous and not limited to initial training and orientation to the organization.

Rewarding contingently and well . Companies that foster job involvement generally pay employees well and let them share in gains and profits made by the organization. This is true even of highly cost-conscious organizations that realize that employee productivity is a key driver of cost reduction. A contingent element of employee compensation contributes to employee identification with the goals and fortunes of the organization.

Reducing status differences . A greater sense of teamwork and collective spirit in the organization results from minimizing status differences between executives and other employees. When executives forgo outsized compensation packages and conspicuous displays of status, employees lower in the hierarchy are able to identify more closely with them and, through them, with the organization.

Self-managed teams . Self-managed work teams incorporate and leverage an important motivational principle: that people identify closely with their peers and feel obligated to them by social norms and reciprocity. This means that some employees who might shirk in a hierarchical structure will not do so in the context of self-managed teams. Firms that foster high employee involvement often structure all work tasks as teamwork.

Sharing information . Employees are likely to identify to a greater extent with their work and organization when the organization freely shares information about its operations and performance. This information sharing highlights for employees their personal stake in the organization and gives them metrics by which they may steer their efforts in pursuit of organizational goals.

Job involvement—the extent to which individuals identify with their jobs and consider them central to their identities—constitutes a key to individual effort, motivation, performance, and satisfaction, as well as to organizational performance. Job involvement results from differences in individual predispositions and also from organizational characteristics, supervisory behavior, and job design characteristics. Thus, organizations can promote job involvement by selecting the right people, fostering a conducive psychological climate, and incorporating human practices and policies supportive of high employee job involvement. Such practices can hold the key to sustainable competitive advantage.

References:

- Brown, S. P. (1996). A meta-analysis and review of organizational research on job involvement. Psychological Bulletin, 120, 235-255.

- Brown, S. P., & Leigh, T. W. (1996). A new look at psychological climate and its relationship to job involvement, effort, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 358-368.

- Huselid, M. A. (1995). The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 645-672.

- Kanungo, R. N. (1982). Measurement of job and work involvement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67, 341-349.

- Pfeffer, J. (1998). The human equation. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Reeve, C. L., & Smith, C. S. (2001). Refining Lodahl and Kejner’s Job Involvement Scale with a convergent evidence approach: Applying multiple methods to multiple samples. Organizational Research Methods, 4, 91-111.

- Work Motivation

Comparative investigations of aftersintering of UO 2 fuel pellets

- Theory and Processes of Formation and Sintering of Powdered Materials

- Published: 06 May 2010

- Volume 51 , pages 173–176, ( 2010 )

Cite this article

- V. V. Basov 1

23 Accesses

Explore all metrics

The basic parameters of comparative tests of UO 2 fuel pellets produced by the technology of powder metallurgy for aftersinterability using their repeated thermal treatment (aftersintering) in different gas media, namely, with and without humidification, are presented. The results of an evaluation of the level of aftersinterability of these pellets by different procedures is presented, they are analyzed, and a substantiation of the expediency of using this operation manual for evaluating afersintering without the humidification of the gas medium developed at the OAO Machine Building Works (MSZ), Elektrostal’, Moscow oblast, is presented.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Fuel pellets based on uranium dioxide and alloyed with nanodispersed additives of Al(OH)3 and TiO2

V. S. Panov, V. Yu. Lopatin, … V. V. Martynov

Effects of Dual Oxidizers on the Properties of Composite Solid Rocket Propellants

Development Background and Research Progress of UN-U3Si2 Composite Fuel

An Acceptable Model and Related Statistical Methods for the Analysis of Fuel Densification , US Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Regulatory Guide 1.126.1978.

Freshley, M.D., Brite, D.M., Daniel, I.L., and Hart, P.E., J. Nucl. Mater , 1976, vol. 62, pp. 138–166.

Article CAS ADS Google Scholar

Radford, K. and Pope, I., J. Nucl. Mater , 1977, vol. 64, pp. 289–299.

Radford, K., et al., US Patent 4430276, 1984.

Basov, V.V., Metodika provedeniya ispytanii tabletok is dioksida urana na “dospekaemost’ “ (Procedure for Performance of the Tests of the Pellets made of Uranium Dioxide for Aftersinterability), Electrostal’: PO MSZ, 1994.

Google Scholar

Bakhteev, A.N., Opredelenie termicheskoi stabil’nosti geometricheskikh razmerov toplivnykh tabletok tipa “V” i “R”: Metodika vypolneniya izmerenii (Determination of Thermal Stability of Geometric Sizes for Fuel Pellets of Types “V” and “R”: Procedure of Carrying out the Measurements), Moscow: VNIINM, 1992.

Basov, V.V., Opredelenie kharacteristik termicheskoi stabil’nosti toplivnykh tabletok tipov “R”, “R-E”, “V”: Metodika (tekhnologicheskaya instruktsiya) (Determination of Characteristics of Thermal Stability of Fuel Pellets of Types “R”, “R-E”, and “V”: Procedure (Technological Instruction), Electrostal’: OAO MSZ, 1999.

Kotel’nikov, R.B., Bashlykov, S.N., Kashtanov, A.I., et al., Vysokotemperaturnoe yadernoe toplivo (HighTemperature Nuclear Fuel), Moscow: Metallurgiya, 1978.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

OAO Machine Building Works, ul. K. Marksa 12, Elektrostal’, Moscow oblast, 144001, Russia

V. V. Basov

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Additional information

Original Russian Text © V.V. Basov, 2009, published in Izvestiya VUZ. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional’nye Pokrytiya, 2009, No. 3, pp. 27–30.

About this article

Basov, V.V. Comparative investigations of aftersintering of UO 2 fuel pellets. Russ. J. Non-ferrous Metals 51 , 173–176 (2010). https://doi.org/10.3103/S1067821210020185

Download citation

Published : 06 May 2010

Issue Date : April 2010

DOI : https://doi.org/10.3103/S1067821210020185

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- fuel pellets

- model of fuel compaction

- repeated thermal treatment

- aftersintering

- aftersinterability

- procedure of carrying out aftersintering

- aftersintering installation

- stoichiometric composition

- isothermal sintering

- thermal shrinkage

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS. A lock ( Lock Locked padlock ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

A Dear Colleague Letter (DCL) is an informal correspondence which is written by a Requesting Office and distributed to communities within a specific program area, to attract individuals eligible under a Visiting Scientist, Engineer, and Educator (VSEE) appointment, an Intergovernmental Personnel Act (IPA) assignment and/or a Federal Temporary appointment. These letters may be circulated in paper form through internal mail, distributed electronically using listservs or accessed through NSF.gov’s Career Page.

Science Advisor for Public Access (Program Director)

Application timeline, position summary.

The Office of Integrative Activities (OIA) within the Office of the Director at the National Science Foundation (NSF) announces a nationwide search to fill the Science Advisor for Public Access position. The position coordinates agency responses to federal public access mandates, oversees development of the NSF Public Access Repository, coordinates with other agencies via involvement in the NSTC and other cross-agency groups, and contributes to the NSF Knowledge Management activity.

Formal consideration of interested applications will begin immediately and continue until a selection is made.

OIA works across disciplinary boundaries to lead and coordinate strategic programs and opportunities that: advance research excellence and innovation; develop human and infrastructure capacity critical to the U.S. science and engineering enterprise; and promote engagement of scientists and engineers at all career stages and the personnel who support them.

For more information on the NSF Public Access Initiative, see: https://new.nsf.gov/public-access

Position Description

Serves as the primary representative and point of contact for the NSF Public Access Initiative and Open Science matters, in consultation with other concerned entities within the Foundation (e.g., Office of the Director, Office of General Counsel, etc.) and the members of the cross-agency Public Access and Open Science Working Group (PAOSWG). Creates and maintains linkages to other NSF units and other Federal agencies in pursuit of the overall NSF mission.

Works closely with the NSF Chief Information Officer staff on implementation and refinement of NSF's public access policies and systems (e.g., NSF-PAR, see: http://par.nsf.gov ). Provides oversight and direction to system developers at NSF and DOE in the collaborative development and maintenance of the subsystems comprising NSF-PAR.

Contributes to the NSF Knowledge Management activity (e.g., change management) and its work with internal, enterprise-wide policies.

Assists the Office of Legislative and Public Affairs (OLPA) in communicating NSF’s Public Access and Open Science goals to the range of research communities served by NSF.

Provides strategic and technical advice to the PAOSWG and the Office of the Director on policy development and implementation regarding public access to the outcomes of federally funded research, and other related science policy issues as they arise.

Analyzes and integrates scientific input and policy guidance from OMB, OSTP, Congress, the National Academy of Sciences, professional societies, the National Science Board, NSF policy groups, the Advisory Committee for Cyberinfrastructure, and other agencies and organizations into the Foundation’s plans for implementing public access and other science policy issues.

Advises OIA on advanced technology for knowledge management, including but not limited to taxonomy, ontology, machine learning, artificial intelligence, and semantic search.

Applies contemporary methods of organizing data, information, and knowledge to internal NSF information.

Provides leadership and support for the NSF Public Access Working Group. The NSF Public Access Working Group is charged with oversight of the implementation of the NSF Public Access Plan 2.0 (NSF 23-104, see: https://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2023/nsf23104/nsf23104.pdf ) and is comprised of senior leadership from across the Foundation.

Serves on or leads NSF-wide groups addressing public access and other policy issues. Serves on or leads teams of experts on interagency studies and, working with the Public Access working group and the Office of the Director, helps to coordinate NSF involvement in relevant interagency activities.

Working with the Office of the Director and other NSF leadership, works to coordinate with the international science community on public access (and related policy issues as they arise) with the appropriate units within NSF, and to facilitate NSF interaction/participation in international science policy bodies.

Represents NSF as appropriate on internal committees, interagency committees, at meetings of other Federal agencies, professional organizations, and universities; participating, providing advice, and drafting recommendations and reports representing the outcome of such meetings.

Prepares background papers, presentations, and reports for use by senior NSF leadership in discussions with the National Science Board and for hearings and congressional testimony, as needed. Initiates, conducts, and manages studies and analyses to assess the scientific and technological contributions of public access to the achievement of national goals and objectives, as needed.

Serves as liaison with other Federal agencies, particularly in interagency programs involving public access policy development and implementation, and conducts other duties as assigned.

Appointment options

The position recruited under this announcement will be filled under the following appointment option(s):

Intergovernmental Personnel Act (IPA) Assignment: Individuals eligible for an IPA assignment with a Federal agency include employees of State and local government agencies or institutions of higher education, Indian tribal governments, and other eligible organizations in instances where such assignments would be of mutual benefit to the organizations involved. Initial assignments under IPA provisions may be made for a period up to two years, with a possible extension for up to an additional two-year period. The individual remains an employee of the home institution and NSF provides the negotiated funding toward the assignee's salary and benefits. Initial IPA assignments are made for a one-year period and may be extended by mutual agreement.

Eligibility information

It is NSF policy that NSF personnel employed at or IPAs detailed to NSF are not permitted to participate in foreign government talent recruitment programs. Failure to comply with this NSF policy could result in disciplinary action up to and including removal from Federal Service or termination of an IPA assignment and referral to the Office of Inspector General. https://www.nsf.gov/careers/Definition-of-Foreign-Talent-HRM.pdf .

Applications will be accepted from U.S. Citizens. Recent changes in Federal Appropriations Law require Non-Citizens to meet certain eligibility criteria to be considered. Therefore, Non-Citizens must certify eligibility by signing and attaching this Citizenship Affidavit to their application. Non-Citizens who do not provide the affidavit at the time of application will not be considered eligible. Non-Citizens are not eligible for positions requiring a security clearance.

To ensure compliance with an applicable preliminary nationwide injunction, which may be supplemented, modified, or vacated, depending on the course of ongoing litigation, the Federal Government will take no action to implement or enforce the COVID-19 vaccination requirement pursuant to Executive Order 14043 on Requiring Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccination for Federal Employees. Federal agencies may request information regarding the vaccination status of selected applicants for the purposes of implementing other workplace safety protocols, such as protocols related to masking, physical distancing, testing, travel, and quarantine.

Qualifications

Candidates must have a Ph.D. in an appropriate field plus after award of the Ph.D., six or more years of successful research, research administration, and/or managerial experience pertinent to the position; OR a Master's degree in an appropriate field plus after award of the degree, eight or more years of successful research, research administration, and/or managerial experience pertinent to the position.

Knowledge of current and historical developments in federal public access policies and mandates is highly desirable, as is familiarity with scientific communication practices and research data practices. Candidates must be able to communicate and interact with senior science, engineering and managerial personnel throughout the Foundation, with other agencies, and the general science and engineering community, and are expected to know and diplomatically express the views and goals of the NSF on Public Access topics in many situations both within and outside of the National Science Foundation. Candidates must also be skilled and experienced in operating both independently and interdependently with others. Outstanding oral and writing skills and the capability to deal with a wide variety of materials, frequently changing venues, and tight deadlines is imperative.

How to apply

To apply, email the following (i) a cover letter outlining qualifications and interest in the position, and (ii) an up-to-date curriculum vitae, to [email protected] .

Media Monarchy

Moscow metro blasts: another fsb inside job.

“ The first explosion took place on a train after it had stopped in the Lubyanka station in central Moscow , close to the headquarters of Russia’s FSB security service, a spokeswoman for the Russian emergencies ministry told AFP .”

“ The first blast at the Lubyanka metro station killed 22 people and wounded 12 . The second at Park Kulturi station left 12 dead and 7 wounded ,” reported AFP . Russian Federal Security Service chief Alexander Bortnikov has already blamed Chechen rebels for the attack, an explanation slavishly accepted by western media outlets like the BBC who are already running feature articles about the history of terrorism in Russia that completely fail to mention the FSB’s direct role in almost every major attack to have taken place over the last 10 years .

Since the explanation that two female suicide bombers with explosives strapped to their bodies were responsible for the bombing has come directly from the FSB , past history means we can only treat the official story with the utmost suspicion.

The notorious Russian FSB has a documented history of staging false flag events in order to accomplish political agendas .

update: bombs kill 12 in russia’s dagestan region from cnn : Twelve people – nine of them police officers – were killed Wednesday when two bombs exploded in Russia’s southern republic of Dagestan , officials told CNN. Another 23 people, including 11 police officers, were hospitalized with wounds from the bombings, at least one of which was carried out by a suicide bomber, according to a spokesman for the Dagestan police and Vladimir Markin, a spokesman for the Investigative Committee in the Russian prosecutor general’s office. It happened two days after female suicide bombers killed at least 39 people on the Moscow metro .

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

An official website of the United States government