Tier 3: Offer the National DPP Lifestyle Change Program

‹ View Table of Contents

Many pharmacies already offer preventive care services like immunizations and smoking cessation clinics. The National DPP provides an opportunity to expand pharmacy-based preventive care services to improve health outcomes for patients. Joining this program will also allow pharmacies to build referral networks with primary care providers and health care organizations in their communities.

How Can Delivering the National DPP Lifestyle Change Program Benefit Pharmacies?

- Applying for CDC recognition is free. Once a pharmacy’s application is accepted, it will receive pending recognition and be listed on the CDC website as part of a nationwide community of organizations working to prevent type 2 diabetes among people at risk.

- A growing number of employers and insurers, both public and private, are reimbursing for the National DPP LCP. Most insurers require CDC recognition and reimburse using a pay-for-performance model. In 2018, the program became available to eligible Medicare beneficiaries as a covered service.

- The National DPP can provide learning and professional growth opportunities for the pharmacy workforce. For example, pharmacy staff members are well positioned to serve as Lifestyle Coaches because they are familiar with patient care and motivational interviewing techniques.

- NCPA can provide information and resources to help organizations deliver the National DPP LCP.

How Can Pharmacies Become CDC-Recognized Delivery Organizations?

If a pharmacy decides to deliver the National DPP LCP, it will need to submit an application to become a CDC-recognized delivery organization. See Table 3 for an outline of this process. For more detailed information, see the DPRP Standards . To learn more about delivering the National DPP LCP, go to the National DPP CSC website.

Examples of how schools of pharmacy are currently working to expand access to and delivery of the National DPP LCP include the following:

- The University of North Carolina’s Eshelman School of Pharmacy embedded the National DPP into its curriculum to prepare students for when they are placed in pharmacies during their clinical rotations. This training helps increase prediabetes screening, testing, and referrals to local National DPP LCP classes.

- The Southwestern Oklahoma State University College of Pharmacy developed a course based on the National DPP LCP to train students as Lifestyle Coaches. The course also pairs fourth-year pharmacy students with CDC-recognized organizations to support program participants in communities with limited resources in Oklahoma.

- The Wilkes University Nesbitt School of Pharmacy created an elective course for students to train as National DPP Lifestyle Coaches. The school then matched students with local, independent pharmacies through an elective experiential rotation to support and lead implementation of the LCP. Other students partnered with pharmacies across the state to support National DPP LCP classes.

a Evaluation for these requirements based on all participants attending at least 3 sessions during months 1 to 6 and whose time from first session to last session is at least 9 months. At least 5 participants per submission who meet this criterion are required for evaluation.

b All Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program beneficiaries must have a blood glucose test for eligibility.

What Is an Umbrella Hub Arrangement?

To help expand the reach of the National DPP, CDC supports umbrella hub arrangements (UHAs) to connect community organizations with health care payment systems. This connection allows organizations to seek timely, sustainable reimbursement for the National DPP LCP. Each UHA is created by an umbrella hub organization and includes subsidiaries and a billing platform for submitting claims.

UHAs can reduce the administrative burden for CDC-recognized organizations by:

- Aggregating DPRP data.

- Sharing CDC recognition status.

- Operating as an MDPP supplier.

- Helping community organizations (such as pharmacies) receive reimbursement more quickly than organizations that submit claims outside of a UHA.

- Helping expand the reach and sustainability of National DPP LCPs.

For more information about UHAs, see the National DPP Coverage Toolkit . See a Tier 3 case study below.

School of Pharmacy Modifies Curriculum to Improve Access to the National DPP Lifestyle Change Program

In 2019, a community-minded developer built a grocery store in a low-income food desert in Richmond, Virginia. The developer recognized that the neighborhood would also benefit from a community education center that focused on healthy lifestyles. The Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Health Hub was created to meet this need and included service offerings from multiple university departments.

To support these efforts, the VCU School of Pharmacy drew on its past experience providing diabetes education and type 2 diabetes prevention classes to people with limited access to clinical or community resources. The school partnered with the VCU Health Dietetic Internship Program to offer the National DPP LCP. Teams of dietetic interns and pharmacy residents lead weekly classes, as well as grocery store tours, cooking classes, and physical education programs.

Tier 3 in Action: Offer the National DPP LCP

VCU also adapted its Health Promotion and Communication in Pharmacy Practice course to include elements of the National DPP Lifestyle Coach training. This mandatory first-year course in VCU’s PharmD program already contained much of the required content, such as motivational interviewing, social determinants of health, health literacy, communication with older adults, and smoking cessation.

Merging the two curricula helped students understand how the healthy lifestyle content applies in the real world. Students also received their National DPP Lifestyle Coach designation at the end of the semester.

Feedback from the first class of 102 students indicated that the program had met its goals. More Lifestyle Coaches were trained, which helped expand access to the National DPP LCP. Students were paired with individual participants to provide experiential learning for the students and improve program retention.

Keys to Success

From 2019 to 2022, the program reported that:

- 356 Lifestyle Coaches were trained.

- 90 community members

- 298 pounds were lost.

- After pairing students with participants, retention doubled from the first cohort to the fourth cohort.

To ensure the success and sustainability of its efforts, the VCU School of Pharmacy:

- Integrated Lifestyle Coach training into its PharmD core curriculum.

- Created an interprofessional partnership with VCU’s dietetic internship program to lead the National DPP LCP.

- Paired pharmacy students with participants to serve as individual Lifestyle Coaches between sessions, to increase retention.

- Expanded National DPP LCP capacity by training pharmacy students to serve as Lifestyle Coaches.

Pharmacy Guide Pages

- Why Should You Participate?

- Tier 1: Promote Awareness of Prediabetes and the National DPP Among Patients at Risk

- Tier 2: Screen, Test, Refer, and Enroll Patients

- › Tier 3: Offer the National DPP Lifestyle Change Program

- How to Sustain Your Program

To receive email updates about the National Diabetes Prevention Program (National DPP) enter your email address:

- Diabetes Home

- State, Local, and National Partner Diabetes Programs

- National Diabetes Prevention Program

- Native Diabetes Wellness Program

- Chronic Kidney Disease

- Vision Health Initiative

- Heart Disease and Stroke

- Overweight & Obesity

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- Скидки дня

- Справка и помощь

- Адрес доставки Идет загрузка... Ошибка: повторите попытку ОК

- Продажи

- Список отслеживания Развернуть список отслеживаемых товаров Идет загрузка... Войдите в систему , чтобы просмотреть свои сведения о пользователе

- Краткий обзор

- Недавно просмотренные

- Ставки/предложения

- Список отслеживания

- История покупок

- Купить опять

- Объявления о товарах

- Сохраненные запросы поиска

- Сохраненные продавцы

- Сообщения

- Уведомление

- Развернуть корзину Идет загрузка... Произошла ошибка. Чтобы узнать подробнее, посмотрите корзину.

Oops! Looks like we're having trouble connecting to our server.

Refresh your browser window to try again.

Product Identifiers

- Publisher Corwin Press

- ISBN-10 1412953316

- ISBN-13 9781412953313

- eBay Product ID (ePID) 72739443

Product Key Features

- Author Kathleen M. Mcnamara

- Publication Name Tier 3 of the Rti Model : Problem Solving Through a Case Study Approach

- Format Trade Paperback

- Language English

- Publication Year 2009

- Type Textbook

- Number of Pages 248 Pages

- Item Length 10in

- Item Height 0.6in

- Item Width 7in

- Item Weight 8.2 Oz

Additional Product Features

- Lc Classification Number Lc4802.T54 2009

- Reviews SThis book provides a timely and crucial resource for school psychologists who seek to use best practices in responsive intervention. It shows each step of tier 3 case study methods and how they relate to all other aspects of RTI., This book offers critical, practical, coherent, comprehensive, and researched-based information for schools and districts implementing an RTI framework of intervention. It is a map for a seamless process of support for school psychologists and school teams providing tiered interventions to increase student achievement., 'eoeThis book offers critical, practical, coherent, comprehensive, and research-based information for schools and districts implementing an RTI framework of intervention. It maps a seamless process of support that enables school psychologists and school teams to provide tiered interventions to increase student achievement.'e�, eoeThis book offers critical, practical, coherent, comprehensive, and research-based information for schools and districts implementing an RTI framework of intervention. It maps a seamless process of support that enables school psychologists and school teams to provide tiered interventions to increase student achievement.e, 'eoeThis book provides a timely and crucial resource for school psychologists who seek to use best practices in responsive intervention. It shows each step of tier 3 case study methods and how they relate to all other aspects of RTI.'e�, eoeThis is a GREAT book. Comprehensive, easy to understand for psychologists. Great attitude about the processe"positive, helpful.e, eoeThis book provides a timely and crucial resource for school psychologists who seek to use best practices in responsive intervention. It shows each step of tier 3 case study methods and how they relate to all other aspects of RTI.e, The case studies are relevant and incorporate the key elements of collaborative problem solving, data-based decision making, logical linkage between the stages, and fidelity of case study procedures. This is an excellent resource for educators. Highly Recommended., This is a GREAT book. Comprehensive, easy to understand for psychologists. Great attitude about the process-positive, helpful., 'eoeThis is a GREAT book. Comprehensive, easy to understand for psychologists. Great attitude about the process'e"positive, helpful.'e�, This is a GREAT book. Comprehensive, easy to understand for psychologists. Great attitude about the process--positive, helpful., This book offers critical, practical, coherent, comprehensive, and research-based information for schools and districts implementing an RTI framework of intervention. It maps a seamless process of support that enables school psychologists and school teams to provide tiered interventions to increase student achievement., SThis book offers critical, practical, coherent, comprehensive, and research-based information for schools and districts implementing an RTI framework of intervention. It maps a seamless process of support that enables school psychologists and school teams to provide tiered interventions to increase student achievement., This book provides a timely and crucial resource for school psychologists who seek to use best practices in responsive intervention. It shows each step of tier 3 case study methods and how they relate to all other aspects of RTI., SThis is a GREAT book. Comprehensive, easy to understand for psychologists. Great attitude about the process-positive, helpful.

- Table of Content PrefaceAcknowledgmentsAbout the Authors1. Introduction to RTI and the Case Study Model Context and History The Response to Intervention Process The Case Study Model and Prereferral Intervention Summary2. Assessment Principles and Practices Assessment Methods Assessment at Tier 1 Assessment at Tier 2 Assessing Behavior Summary3. Facilitating Response to Intervention in Schools School Psychologist as Systems Change Agent Evaluating the System Goal Setting RTI Implementation Summary4. Problem Identification Tier 1 Tier 2 Tier 3 Behavioral Definition of the Problem Problem Certification: Establishing the Severity of the Discrepancy Between Actual and Expected Performance Formulating Intervention Goals Planning Data-Collection Activities for Baseline Measurement and Progress Monitoring Assessment of Factors Related to the Problem Summary5. Problem Analysis Generating Hypotheses Primary and Secondary Dependent Variables Types of Hypotheses Intervention Selection Hypothesis Testing Summary6. Single-Case Design Single-Case Design and Hypothesis Testing Single-Case Design and Progress Monitoring Choosing a Single-Case Design Summary7. Intervention Selecting Research-Based Interventions Intervention Integrity Linking Interventions to Hypotheses Characteristics of Effective Academic Interventions Characteristics of Effective Behavioral Interventions Targets of Intervention Summary8. Evaluating Case Study Outcomes Visual Analysis Conducting Visual Analyses Magnitude of Change Choosing, Calculating, and Interpreting Effect Sizes Quality of the Outcome: Goal-Attainment Scaling Choosing Evaluation Methods and Judging Outcomes Summary9. Using the Case Study to Determine Special Education Eligibility Disability Versus Eligibility Determination Responsiveness Versus Resistance Using Case Study Information for Special Education Eligibility Determination RTI and Specific Learning Disabilities Decision Making in Eligibility Determination Technical Adequacy of Decision-Making Practices Eligibility Decisions Summary10. Program Evaluation Case Study Structure Case Study Rubric Case Study: Morgan Case Study: Reggie Evaluation of School Psychology Services and Programs Case Study Fidelity Intervention Integrity Magnitude of Change Goal-Attainment Scaling SummaryReferencesIndex

- Copyright Date 2010

- Topic Decision-Making & Problem Solving, Special Education / General, Special Education / Learning Disabilities

- Lccn 2009-019910

- Dewey Decimal 371.9

- Intended Audience Scholarly & Professional

- Dewey Edition 22

- Illustrated Yes

- Genre Education

You are here

Tier 3 of the RTI Model Problem Solving Through a Case Study Approach

- Sawyer Hunley - University of Dayton, USA

- Kathy McNamara - Cleveland State University, Cleveland, Ohio, Cleveland State University, USA

- Description

"This book offers critical, practical, coherent, comprehensive, and research-based information for schools and districts implementing an RTI framework of intervention. It maps a seamless process of support that enables school psychologists and school teams to provide tiered interventions to increase student achievement." —Jane Wagmeister, Director of Curriculum, Instruction, and Continuous Improvement, RTI Co-Chair Task Force Ventura County Office of Education Identify students' learning needs and make appropriate decisions regarding instruction and intervention!

Response to Intervention (RTI) is a three-tiered framework that helps all students by providing targeted interventions at increasing levels of intensity. This detailed guide to tier 3 of the RTI model provides school psychologists and RTI teams with a case study approach to conducting intensive, comprehensive student evaluations.

With step-by-step guidelines for Grades K–12, this resource demonstrates how to develop a specific case study for students who are struggling in the general classroom. Focusing exclusively on the third tier, the book:

- Provides guidance on problem identification and analysis, progress monitoring, selection of research-based interventions, and evaluation of case study outcomes

- Addresses both academic and behavioral challenges, including mental health issues

- Shows how school psychologists can collaborate with other members of the RTI team

- Provides tools for assessment and for tracking progress

Tier 3 of the RTI Model guides school psychologists through the involved, in-depth process of building a case study that identifies student needs and helps educators determine the best way to educate students with learning challenges.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

“This book provides a timely and crucial resource for school psychologists who seek to use best practices in responsive intervention. It shows each step of tier 3 case study methods and how they relate to all other aspects of RTI.”

“This book offers critical, practical, coherent, comprehensive, and research-based information for schools and districts implementing an RTI framework of intervention. It maps a seamless process of support that enables school psychologists and school teams to provide tiered interventions to increase student achievement.”

“This is a GREAT book. Comprehensive, easy to understand for psychologists. Great attitude about the process—positive, helpful.”

"The case studies are relevant and incorporate the key elements of collaborative problem solving, data-based decision making, logical linkage between the stages, and fidelity of case study procedures. This is an excellent resource for educators. Highly Recommended."

Preview this book

Sample materials & chapters.

Hunley_Tier_3_Preface

Hunley_Tier_3_Chapter_1

For instructors

Select a purchasing option.

This title is also available on SAGE Knowledge , the ultimate social sciences online library. If your library doesn’t have access, ask your librarian to start a trial .

- Open access

- Published: 26 April 2024

Clinician and staff experiences with frustrated patients during an electronic health record transition: a qualitative case study

- Sherry L. Ball 1 ,

- Bo Kim 2 , 3 ,

- Sarah L. Cutrona 4 , 5 ,

- Brianne K. Molloy-Paolillo 4 ,

- Ellen Ahlness 6 ,

- Megan Moldestad 6 ,

- George Sayre 6 , 7 &

- Seppo T. Rinne 2 , 8

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 535 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Electronic health record (EHR) transitions are known to be highly disruptive, can drastically impact clinician and staff experiences, and may influence patients’ experiences using the electronic patient portal. Clinicians and staff can gain insights into patient experiences and be influenced by what they see and hear from patients. Through the lens of an emergency preparedness framework, we examined clinician and staff reactions to and perceptions of their patients’ experiences with the portal during an EHR transition at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).

This qualitative case study was situated within a larger multi-methods evaluation of the EHR transition. We conducted a total of 122 interviews with 30 clinicians and staff across disciplines at the initial VA EHR transition site before, immediately after, and up to 12 months after go-live (September 2020-November 2021). Interview transcripts were coded using a priori and emergent codes. The coded text segments relevant to patient experience and clinician interactions with patients were extracted and analyzed to identify themes. For each theme, recommendations were defined based on each stage of an emergency preparedness framework (mitigate, prepare, respond, recover).

In post-go-live interviews participants expressed concerns about the reliability of communicating with their patients via secure messaging within the new EHR portal. Participants felt ill-equipped to field patients’ questions and frustrations navigating the new portal. Participants learned that patients experienced difficulties learning to use and accessing the portal; when unsuccessful, some had difficulties obtaining medication refills via the portal and used the call center as an alternative. However, long telephone wait times provoked patients to walk into the clinic for care, often frustrated and without an appointment. Patients needing increased in-person attention heightened participants’ daily workload and their concern for patients’ well-being. Recommendations for each theme fit within a stage of the emergency preparedness framework.

Conclusions

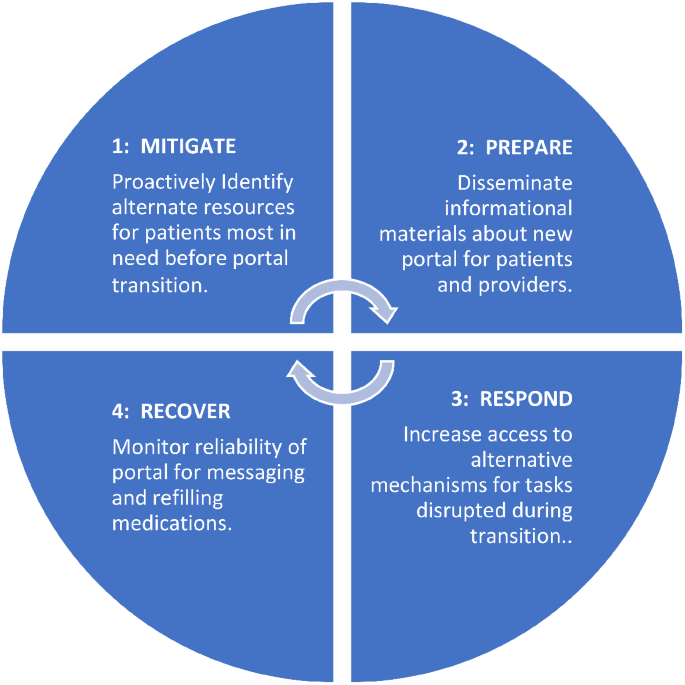

Application of an emergency preparedness framework to EHR transitions could help address the concerns raised by the participants, (1) mitigating disruptions by identifying at-risk patients before the transition, (2) preparing end-users by disseminating patient-centered informational resources, (3) responding by building capacity for disrupted services, and (4) recovering by monitoring integrity of the new portal function.

Peer Review reports

Electronic health record (EHR) transitions present significant challenges for healthcare clinicians and staff. These transitions require adjustments in care delivery and may threaten care quality and value. It is critical that healthcare organizations undergoing these changes learn from others who have undergone similar transitions [ 1 , 2 ]. However, the current literature lacks adequate guidance on navigating EHR transitions, especially as they relate to how clinicians and staff interact with patients [ 3 ].

Embedded within EHRs, patient portals facilitate complete, accurate, timely, and unambiguous exchange of information between patients and healthcare workers [ 4 , 5 ]. These portals have become indispensable for completing routine out-of-office-visit tasks, such as medication refills, communicating laboratory results, and addressing patient questions [ 6 ]. In 2003, the VA launched their version of a patient portal, myHealtheVet [ 7 ] and by 2017 69% of Veterans enrolled in healthcare at the VA had registered to access the patient portal [ 8 ]. Similar to other electronic portals, this system allows Veterans to review test results, see upcoming appointments, and communicate privately and securely with their healthcare providers.

EHR transitions can introduce disruptions to patient portal communication that may compromise portal reliability, impacting patient and clinician satisfaction, patients’ active involvement in self-management, and ultimately health outcomes [ 9 ]. During an EHR transition, patients can expect reductions in access to care even when clinician capacity and IT support are increased. Patients will likely need for more assistance navigating the patient portal including and using the portal to communicate with their providers [ 10 ]. Staff must be prepared and understand how the changes in the EHR will affect patients and safeguards must be in place to monitor systems for potential risks to patient safety. Building the capacity to respond to emerging system glitches and identified changes must be included in any transition plan. Although portal disruptions are likely to occur when a new EHR is implemented, we know little about how these disruptions impact healthcare workers’ interactions and care delivery to patients [ 11 , 12 ].

Due to an urgency to raise awareness and promote resolution of these patient portal issues,, we utilized existing data from the first EHR transition site for the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)’s enterprise-wide transition. We focused on end users’ responses to the question “How Veterans were affected by the transition?”. We used qualitative methods to begin to understand how provider and patient interactions were affected during and by the EHR transition. We explored the impact of the EHR transition on patients through healthcare workers’ vicarious and direct experiences with patients. Due to the high level of disruption in care delivery we draw on insights from an emergency preparedness framework [ 13 ] to generate a set of recommendations to improve healthcare workers’ experiences during EHR transitions. The emergency preparedness framework includes 4 phases of an iterative cycle that include: (1) building capacity to mitigate issues, (2) preparing for the inevitable onset of issues, (3) responding to issues as they emerge, and (4) strategies to recover from any damage incurred.

In early 2020, the VA embarked on an EHR transition from a homegrown, legacy EHR system, developed by VA clinicians and used since the 1990s, to a new commercial system by the Oracle-Cerner Corporation. The primary objectives of this transition were to standardize care and improve interoperability between VA Medical Centers nationwide and the Department of Defense (DoD). Spanning over a decade, this transition plan is scheduled to roll out to all VA medical centers and outpatient clinics.

In this manuscript, we present data from the Mann-Grandstaff VA Medical Center in Spokane, WA, VA’s first EHR transition site. The study uses qualitative methods with clinician and staff interviews as part of a larger multi-method evaluation of the EHR transition. Our overarching goal is to identify and share recommendations to improve VA’s EHR transition efforts; rather than be guided by a theoretical framework our study design including the interview guides [ 14 , 15 ] were based primarily on what was being experienced. An experienced team of ten qualitative methodologists and analysts conducted the study.

This evaluation was designated as non-research/quality improvement work by the VA Bedford Healthcare System Institutional Review Board deeming it exempt from needing an informed consent. Study materials, including interview guides with verbal consent procedures, were reviewed and approved by labor unions and by the VA Bedford Healthcare System Institutional Review Board; all methods were carried out in accordance with local and national VA guidelines and regulations.

Interview guides and an outline of the data collection plans were reviewed and approved by relevant national unions before beginning recruitment.

Recruitment

Recruitment began in July 2020, before the first site implemented the new EHR. Prior to collecting data, we met with site leadership to get buy-in and support for the study, understand local context, determine how the site was approaching the transition, and to obtain the names of clinicians and staff for potential interviews. All potential participants were invited by email to participate in a one-hour voluntary interview conducted on Microsoft Teams® about their experiences with this transition; we used snowball sampling during interviews to expand the pool of interviewees. Verbal permission for audio recording of interviews was obtained immediately prior to the interview. Interview participants were informed that they could skip any questions, pause or stop the recording, and stop the interview at any time and were invited to ask questions before beginning the interview.

Most participants were interviewed at multiple timepoints; these included pre-implementation interviews, brief check-ins, and post-implementation interviews (Table 1 ). At the end of the pre-implementation interview, participants were invited to participate in 3–4 additional, shorter (15–20 min), check-in interviews where information about any changes in the transition process, context, or experience could be discussed. Most initial interviewees, in addition to three new participants, participated in post-implementation interviews (35–60 min; approximately 2–3 months and 10–12 months after the implementation) to reflect on the entire transition process.

Data collection

Experienced qualitative interviewers included PhD trained qualitative methodologist and masters level qualitative analysts (JB, SB, AC, EK, MM, GS) conducted individual interviews with clinicians and staff, aligning to a semi-structured interview guide with follow-up probes using the participant’s words to elicit rich responses grounded in the data [ 16 ]. The guide was designed to inform ongoing efforts to improve the rollout of the new EHR. Six main categories were covered in our interview guides, including (1) attitudes toward the new software, (2) information communicated about the transition, (3) training and education, (4) resources, (5) prior experience with EHRs, and (6) prior experiences with EHR transitions. After piloting the interview guide with a clinician, initial interviews were completed between September and October 2020 and averaged ∼ 45 min in duration. Two-month and one-year post-implementation interview guides included an additional question, “Has the Cerner transition affected Vets?”; data presented here largely draw from responses to this question. Check-ins (October 2020– December 2020) took ∼ 15 min; two-month post-implementation interviews (December 2020– January 2021) and one-year post-implementation interviews (October 2020 - November 2021) took ∼ 45 min. Audio recordings of all interviews were professionally transcribed. To ensure consistency and relationship building, participants were scheduled with the same interviewer for the initial and subsequent interviews whenever feasible (i.e., check-ins and post-implementation interviews). Immediately following each interview, interviewers completed a debrief form where highlights and general reflections were noted.

Throughout the data collection process, interviewers met weekly with the entire qualitative team and the project principal investigators to discuss the recruitment process, interview guide development, and reflections on data collection. To provide timely feedback to leadership within the VA, a matrix analysis [ 17 ] was conducted concurrently with data collection using the following domains: training, roles, barriers, and facilitators. Based on these domains, the team developed categories and subcategories, which formed the foundation of an extensive codebook.

Data analysis

All interviewers also coded the data. We used inductive and deductive content analysis [ 18 ]. Interview transcripts were coded in ATLAS.ti qualitative data analysis software (version 9). A priori codes and categories (based on the overall larger project aims and interview guide questions) and emergent codes and categories were developed to capture concepts that did not fit existing codes or categories [ 18 ]. Codes related to patient experience and clinician interactions with patients were extracted and analyzed using qualitative content analysis to identify themes [ 18 ]. Themes were organized according to their fit within the discrete stages of an emergency preparedness framework to generate recommendations for future rollout. In total, we examined data from 111 interviews with 24 VA clinicians and staff (excluding the initial 11 stakeholder meetings (from the 122 total interviews) that were primarily for stakeholder engagement). We focused on participants’ responses related to their experiences interacting with patients during the EHR transition.

Exemplar quotes primarily came from participants’ responses to the question, “Has the Cerner transition affected Vets?” and addressed issues stemming from use of the patient portal. This included both clinicians’ direct experiences with the portal and indirect experiences when they heard from patients about disruptions when using the portal. We identified four themes related to clinicians’ and staff members’ reported experiences: (1) stress associated with the unreliability of routine portal functions and inaccurate migrated information; (2) concern about patients’ ability to learn to use a new portal (especially older patients and special populations); (3) frustration with apparent inadequate dissemination of patient informational materials along with their own lack of time and resources to educate patients on use of the new portal; and (4) burden of additional tasks on top of their daily workload when patients needed increased in-person attention due to issues with the portal.

Stress associated with the unreliability of routine portal functions and inaccurate migrated information

One participant described the portal changes as, “It’s our biggest stress, it’s the patients’ biggest stress… the vets are definitely frustrated; the clinicians are; so I would hope that would mean that behind the scenes somebody is working on it” (P5, check-in).

Participants expressed significant frustration when they encountered veterans who were suddenly unable to communicate with them using routine secure messaging. These experiences left them wondering whether messages sent to patients were received.

Those that use our secure messaging, which has now changed to My VA Health, or whatever it’s called, [have] difficulty navigating that. Some are able to get in and send the message. When we reply to them, they may or may not get the reply. Which I’ve actually asked one of our patients, ‘Did you get the reply that we took care of this?’ And he was like, ‘No, I did not (P11, 2-months post)

Participants learned that some patients were unable to send secure messages to their care team because the portal contained inaccurate or outdated appointment and primary site information.

I’ve heard people say that the appointments aren’t accurate in there… veterans who have said, ‘yeah, it shows I’m registered,’ and when they go into the new messaging system, it says they are part of a VA that they haven’t gone to in years, and that’s the only area they can message to, they can’t message to the [site] VA, even though that’s where they’ve actively being seen for a while now. (P20, 2-months post)

After the EHR transition, participants noted that obtaining medications through the portal, which was once a routine task, became unreliable. They expressed concern around patients’ ability to obtain their medications through the portal, primarily due to challenges with portal usability and incomplete migration of medication lists from the former to the new EHR.

I think it’s been negative, unfortunately. I try to stay optimistic when I talk to [patients], but they all seem to be all having continued difficulty with their medications, trying to properly reorder and get medications seems to still be a real hassle for them. (P17, one-year post) …the medications, their med list just didn’t transfer over into that list [preventing their ability to refill their medications]. (P13, 2-months post)

Concern about patients’ ability to learn to use a new portal

Clinicians and staff expressed concerns around veterans’ ability to access, learn, and navigate a new portal system. Clinicians noted that even veterans who were adept at using the prior electronic portal or other technologies also faced difficulties using the new portal.

They can’t figure out [the new portal], 99% of them that used to use our [old] portal, the electronic secure messaging or emailing between the team, they just can’t use [the new one]. It’s not functioning. (P13, one-year post) Apparently, there’s a link they have to click on to make the new format work for them, and that’s been confusing for them. But I still am having a lot of them tell me, I had somebody recently, who’s very tech savvy, and he couldn’t figure it out, just how to message us. I know they’re still really struggling with that. (P5, 2-months post) And it does seem like the My Vet [my VA Health, new portal], that used to be MyHealtheVet [prior portal], logging on and getting onto that still remains really challenging for a large number of veterans. Like they’re still just unable to do it. So, I do think that, I mean I want to say that there’s positive things, but really, I struggle (P17, one-year post)

Participants recognized difficulties with the new system and expressed empathy for the veterans struggling to access the portal.

I think that a lot of us, individually, that work here, I think we have more compassion for our veterans, because they’re coming in and they can’t even get onto their portal website. (P24, one-year post)

Participants acknowledged that learning a new system may be especially difficult for older veterans or those with less technology experience.

But, you know, veterans, the general population of them are older, in general. So, their technologic skills are limited, and they got used to a system and now they have to change to a new one. (P13, 2-months post) So, for our more elderly veterans who barely turn on the computer, they’re not getting to this new portal. (P8, check in) And you know, I do keep in mind that this is a group of people who aren’t always technologically advanced, so small things, when it’s not normal to them, stymie them.(P13, one-year post)

Concerns were heightened for veterans who were more dependent on the portal as a key element in their care due to specific challenges. One participant pointed out that there may be populations of patients with special circumstances who depend more heavily on the prior portal, MyHealtheVet.

I have veterans from [specific region], that’s the way they communicate. Hearing impaired people can’t hear on the phone, the robocall thing, it doesn’t work, so they use MyHealtheVet. Well, if that goes away, how is that being communicated to the veteran? Ok? (P18, Check-in)

Frustration with inadequate dissemination of information to veterans about EHR transition and use of new portal

Participants were concerned about poor information dissemination to patients about how to access the new portal. During medical encounters, participants often heard from patients about their frustrations accessing the new portal. Participants noted that they could only give their patients a phone number to call for help using the new system but otherwise lacked the knowledge and the time to help them resolve new portal issues. Some clinicians specifically mentioned feeling ill-equipped to handle their patients’ needs for assistance with the new portal. These experiences exacerbated clinician stress during the transition.

Our veterans were using the MyHealtheVet messaging portal, and when our new system went up, it transitioned to My VA Health, but that wasn’t really communicated to the veterans very well. So, what happened was they would go into their MyHealtheVet like they had been doing for all of these years, to go in and request their medications, and when they pulled it up it’d show that they were assigned to a clinician in [a different state], that they have no active medications. Everything was just messed up. And they didn’t know why because there was no alert or notification that things would be changing. (P8, check in) I field all-day frustration from the veterans. And I love my job, I’m not leaving here even as frustrated as I am, because I’m here for them, not to, I’m here to serve the veterans and I have to advocate for them, and I know it will get better, it can’t stay like this. But I constantly field their frustrations.… So, I give them the 1-800 number to a Cerner help desk that helps with that, and I’ve had multiple [instances of] feedback that it didn’t help. (P13, one-year post) And [the patients are] frequently asking me things about their medication [within the portal], when, you know, I can’t help them with that. So, I have to send them back up to the front desk to try to figure out their medications. (P17, one-year post)

Veteran frustration and the burden of additional tasks due to issues with the portal

Clinicians reported that veterans expressed frustration with alternatives to the portal, including long call center wait times. Some veterans chose to walk into the clinic without an appointment rather than wait on the phone. Clinicians noted an increase in walk-ins by frustrated veterans, which placed added workload on clinics that were not staffed to handle the increase in walk-ins.

It’s been kind of clunky also with trying to get that [new portal] transitioned. And then that’s created more walk-ins here, because one, the vets get frustrated with the phone part of it, and then MyHealtheVet (prior portal) not [working], so they end up walking [into the clinic without an appointment]. (P19, check-in) In terms of messages, they can’t necessarily find the clinician they want to message. We had a veteran who came in recently who wanted to talk to their Rheumatologist, and it’s like, yeah, I typed in their name, and nothing came up. So, they have to try calling or coming in. (P20, 2-months post)

In summary, participants described the new patient portal as a source of stress for both themselves and their patients.

In addition to their own direct experience using a new EHR to communicate with their patients, clinicians and staff can be affected by perceptions of their patients’ experiences during an EHR transition [ 19 ]. At this first VA site to transition to the new EHR, clinicians and staff shared their concerns about their patients’ experiences using the portal. They were particularly troubled by unreliability of the secure messaging system and challenges patients faced learning to use the new system without proper instruction. Moreover, clinicians were alarmed to hear about patients having to make in-person visits– especially unplanned (i.e., walk in) ones– due to challenges with the new portal. Each of these issues needs to be addressed to ensure veteran satisfaction. However, the only solution participants could offer to frustrated patients was the telephone number to the help desk, leaving them with no clear knowledge of a solution strategy or a timeline for resolution of the issues.

We propose applying emergency preparedness actions to future EHR rollouts: mitigate, prepare, respond, and recover (Fig. 1 ) [ 13 ]. By applying these actions, patient portal disruptions may be alleviated and patients’ communication with their clinicians and access to care can be maintained. For example, issues stemming from a disruption in the portal may be mitigated by first identifying and understanding which patients typically use the portal and how they use it. Sites can use this information to prepare for the transition by disseminating instructional materials to staff and patients on how to access the new portal, targeting the most common and critical portal uses. Sites can respond to any expected and emerging portal disruptions by increasing access to alternative mechanisms for tasks disrupted by and typically completed within the portal. After the transition, recovery can begin by testing and demonstrating the accuracy and reliability of functions in the new portal. These actions directly address reported clinician concerns and can help maintain patient-clinician communication, and access to care.

The emergency preparedness framework was applied. This framework includes 4 actions: (1) mitigate, (2) prepare, (3) respond, and (4) recover. These actions can be repeated. Recommendations for how each action (1–4) can be applied to a portal transition are included in each blue quadrant of the circle

Sites could mitigate issues by first understanding which patients will be most affected by the transition, such as those who rely heavily on secure messaging. Reliable use of secure messaging within the VA facilitates positive patient-clinician relationships by providing a mechanism for efficient between-visit communication [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. During the EHR transition, clinicians and staff became concerned about the well-being of patients from whom they weren’t receiving messages and those who depended on the portal to complete certain tasks. Since secure messaging is often initiated by patients to clinicians [ 23 ], clinicians will likely be unaware that messages are being missed. Understanding how and which patients currently use the portal and anticipating potential portal needs is a first step toward mitigating potential issues.

Despite efforts to inform Veterans of the EHR transition and patient portal [ 24 ] including information sent to a Veteran by email, direct mail, postings on VA websites, and a town hall, our findings agree with those of Fix and colleagues [ 10 ] and suggest that many Veterans were unprepared for the transition. Our findings suggest that end users heard that more is needed to improve the dissemination of knowledge about the transition and how to navigate the new patient portal to both VA employees and the patients they serve.

Preparations for the transition should prioritize providing VA clinicians and staff with updated information and resources on how to access and use the new portal [ 25 ]. VA clinicians deliver quality care to veterans and many VA employees are proud to serve the nation’s veterans and willing to go the extra mile to support their patients’ needs [ 26 ]. In this study, participants expressed feeling unprepared to assist or even respond to their patients’ questions and concerns about using the new portal. This unpreparedness contributed to increased clinician and staff stress, as they felt ill-equipped to help their patients with portal issues. Such experiences can negatively affect the patient-clinician relationship. Preparing clinicians and patients about an upcoming transition, including technical support for clinicians and patients, may help minimize these potential issues [ 10 , 27 ]. Specialized training about an impending transition, along with detailed instructions on how to gain access to the new system, and a dedicated portal helpline may be necessary to help patients better navigate the transition [ 23 , 28 ].

In addition to a dedicated helpline, our recommendations include responding to potential changes in needed veteran services during the transition. In our study, participants observed more veteran walk-ins due to challenges with the patient portal. Health systems need to anticipate and address this demand by expanding access to in-person services and fortifying other communication channels. For example, sites could use nurses to staff a walk-in clinic to handle increases in walk-in traffic and increase call center capacity to handle increases in telephone calls [ 29 ]. Increased use of walk-in clinics have received heightened attention as a promising strategy for meeting healthcare demands during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 30 ] and can potentially be adapted for meeting care-related needs during an EHR transition. These strategies can fill a gap in communication between clinicians and their patients while patients are learning to access and navigate a new electronic portal.

Finally, there is a need for a recovery mechanism to restore confidence in the reliability of the EHR and the well-being of clinicians and staff. Healthcare workers are experiencing unprecedented levels of stress [ 31 ]. A plan must be in place to improve and monitor the accuracy of data migrated, populated, and processed within the new system [ 2 ]. Knowing that portal function is monitored could help ease clinician and staff concerns and mitigate stress related to the transition.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, data collection relied on voluntary participation, which may introduce self-selection response bias. Second, this work was completed at one VA medical center that was the first site in the larger enterprise-wide transition, and experiences at other VAs or healthcare systems might differ substantially. Third, we did not interview veterans and relied entirely on secondhand accounts of patient experiences with the patient portal. Future research should include interviews with veterans during the transition and compare veteran and VA employee experiences.

Despite a current delay in the deployment of the new EHR at additional VA medical centers, findings from this study offer timely lessons that can ensure clinicians and staff are equipped to navigate challenges during the transition. The strategies presented in this paper could help maintain patient-clinician communication and improve veteran experience. Guided by the emergency preparedness framework, recommended strategies to address issues presented here include alerting those patients most affected by the EHR transition, being prepared to address patients’ concerns, increasing staffing for the help desk and walk-in care clinics, and monitoring the accuracy and reliability of the portal to provide assurance to healthcare workers that patients’ needs are being met. These strategies can inform change management at other VA medical centers that will soon undergo EHR transition and may have implications for other healthcare systems undergoing patient portal changes. Further work is needed to directly examine the perspectives of veterans using the portals, as well as the perspectives of both staff and patients in the growing number of healthcare systems beyond VA that are preparing for an EHR-to-EHR transition.

Data availability

Deidentified data analyzed for this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Electronic health record

Department of Veterans Affairs

VA Medical Centers

Department of Defense

Huang C, Koppel R, McGreevey JD 3rd, Craven CK, Schreiber R. Transitions from one Electronic Health record to another: challenges, pitfalls, and recommendations. Appl Clin Inf. 2020;11(5):742–54.

Article Google Scholar

Penrod LE. Electronic Health Record Transition considerations. PM R. 2017;9(5S):S13–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Cogan AM, Haltom TM, Shimada SL, Davila JA, McGinn BP, Fix GM. Understanding patients’ experiences during transitions from one electronic health record to another: a scoping review. PEC Innov. 2024;4:100258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecinn.2024.100258 . PMID: 38327990; PMCID: PMC10847675.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Powell KR. Patient-perceived facilitators of and barriers to Electronic Portal Use: a systematic review. Comput Inf Nurs. 2017;35(11):565–73.

Google Scholar

Wilson-Stronks A, Lee KK, Cordero CL, et al. One size does not fit all: meeting the Health Care needs of diverse populations. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2008.

Carini E, Villani L, Pezzullo AM, Gentili A, Barbara A, Ricciardi W, Boccia S. The Impact of Digital Patient Portals on Health outcomes, System Efficiency, and patient attitudes: updated systematic literature review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(9):e26189.

Home -. My HealtheVet - My HealtheVet (va.gov).

Nazi KM, Turvey CL, Klein DM, Hogan TP. A decade of veteran voices: examining patient Portal Enhancements through the Lens of user-centered design. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(7):e10413. https://doi.org/10.2196/10413 .

Tapuria A, Porat T, Kalra D, Dsouza G, Xiaohui S, Curcin V. Impact of patient access to their electronic health record: systematic review. Inf Health Soc Care. 2021;46:2.

Fix GM, Haltom TM, Cogan AM, et al. Understanding patients’ preferences and experiences during an Electronic Health Record Transition. J GEN INTERN MED. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08338-6 .

Monturo C, Brockway C, Ginev A. Electronic Health Record Transition: the patient experience. CIN: Computers Inf Nurs. 2022;40:1.

Tian D, Hoehner CM, Woeltje KF, Luong L, Lane MA. Disrupted and restored patient experience with transition to New Electronic Health Record System. J Patient Exp. 2021;18:8.

Emergency management programs for healthcare facilities. the four phases of emergency management. US Department of Homeland Security website: https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=765520 . Accessed 28 Aug 2023.

Ahlness EA, Orlander J, Brunner J, Cutrona SL, Kim B, Molloy-Paolillo BK, Rinne ST, Rucci J, Sayre G, Anderson E. Everything’s so Role-Specific: VA Employee Perspectives’ on Electronic Health Record (EHR) transition implications for roles and responsibilities. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(Suppl 4):991–8. Epub 2023 Oct 5. PMID: 37798577; PMCID: PMC10593626.

Rucci JM, Ball S, Brunner J, Moldestad M, Cutrona SL, Sayre G, Rinne S. Like one long battle: employee perspectives of the simultaneous impact of COVID-19 and an Electronic Health Record Transition. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(Suppl 4):1040–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08284-3 . Epub 2023 Oct 5. PMID: 37798583; PMCID: PMC10593661.

Sayre G, Young J. Beyond open-ended questions: purposeful interview guide development to elicit rich, trustworthy data [videorecording]. Seattle (WA): VA Health Services Research & Development HSR&D Cyberseminars; 2018.

Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2002;12:6855–66.

Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:1107–15.

Haun JN, Lind JD, Shimada SL, Simon SR. Evaluating Secure Messaging from the veteran perspective: informing the adoption and sustained use of a patient-driven communication platform. Ann Anthropol Pract. 2013;372:57–74.

Kittler AF, Carlson GL, Harris C, Lippincott M, Pizziferri L, Volk LA, et al. Primary care physician attitudes toward using a secure web-based portal designed to facilitate electronic communication with patients. Inf Prim Care. 2004;123:129–38.

Shimada SL, Petrakis BA, Rothendler JA, Zirkle M, Zhao S, Feng H, Fix GM, Ozkaynak M, Martin T, Johnson SA, Tulu B, Gordon HS, Simon SR, Woods SS. An analysis of patient-provider secure messaging at two Veterans Health Administration medical centers: message content and resolution through secure messaging. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 2017;24:5.

Jha AK, Perlin JB, Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Effect of the transformation of the Veterans Affairs Health Care System on the quality of care. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:22.

McAlearney AS, Walker DM, Gaughan A, Moffatt-Bruce S, Huerta TR. Helping patients be better patients: a qualitative study of perceptions about Inpatient Portal Use. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26:9.

https://www.myhealth.va.gov/mhv-portal-web/transitioning-to-my-va-health-learn-more .

Beagley L. Educating patients: understanding barriers, learning styles, and teaching techniques. J Perianesth Nurs. 2011;26:5.

Moldestad M, Stryczek KC, Haverhals L, Kenney R, Lee M, Ball S, et al. Competing demands: Scheduling challenges in being veteran-centric in the setting of Health System initiatives to Improve Access. Mil Med. 2021;186:11–2.

Adusumalli J, Bhagra A, Vitek S, Clark SD, Chon TY. Stress management in staff supporting electronic health record transitions: a novel approach. Explore (NY). 2021;17:6.

Heponiemi T, Gluschkoff K, Vehko T, Kaihlanen AM, Saranto K, Nissinen S, et al. Electronic Health Record implementations and Insufficient Training Endanger nurses’ Well-being: cross-sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23:12e27096.

Laurant M, van der Biezen M, Wijers N, Watananirun K, Kontopantelis E, van Vught AJ. Nurses as substitutes for doctors in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 201;7(7):CD001271.

Elnahal S, Kadakia KT, Gondi S, How, U.S. Health systems Can Build Capacity to Handle Demand Surges. Harvard Business Review. 2021. https://hbr.org/2021/10/how-u-s-health-systems-can-build-capacity-to-handle-demand-surges/ Accessed 25 Nov 2022.

George RE, Lowe WA. Well-being and uncertainty in health care practice. Clin Teach. 2019;16:4.

Download references

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and thank members of the EMPIRIC Evaluation qualitative and supporting team for their contributions to this work including Ellen Ahlness, PhD, Julian Brunner, PhD, Adena Cohen-Bearak, MPH, M.Ed, Leah Cubanski, BA, Christine Firestone, Bo Kim, PhD, Megan Moldestad, MS, and Rachel Smith. We greatly appreciate the staff at the Mann-Grandstaff VA Medical Center and associated community-based outpatient clinics for generously sharing of their time and experiences participating in this study during this challenging time.

The “EHRM Partnership Integrating Rapid Cycle Evaluation to Improve Cerner Implementation (EMPIRIC)” (PEC 20–168) work was supported by funding from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research & Development Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) (PEC 20–168). The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Veterans Health Administration, Veterans Affairs, or any participating health agency or funder.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

VA Northeast Ohio Healthcare System, 10701 East Blvd., Research Service 151, 44106, Cleveland, OH, USA

Sherry L. Ball

Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research, VA Boston Healthcare System, Boston, MA, USA

Bo Kim & Seppo T. Rinne

Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research, VA Bedford Healthcare System, Bedford, MA, USA

Sarah L. Cutrona & Brianne K. Molloy-Paolillo

Division of Health Informatics & Implementation Science, Department of Population and Quantitative Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA

Sarah L. Cutrona

Seattle-Denver Center of Innovation for Veteran-Centered and Value-Driven Care, VHA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, WA, USA

Ellen Ahlness, Megan Moldestad & George Sayre

University of Washington School of Public Health, Seattle, WA, USA

George Sayre

Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hannover, NH, USA

Seppo T. Rinne

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

S.R. designed the larger study. G.S. was the qualitative methodologist who led the qualitative team. S.B., E.A., and M.M. created the interview guides and completed the interviews; Data analysis, data interpretation, and the initial manuscript draft were completed by S.B. and B.K. S.C. and B.M. worked with the qualitative team to finalize the analysis and edit and finalize the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sherry L. Ball .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This evaluation was designated as non-research/quality improvement by the VA Bedford Healthcare System Institutional Review Board. All methods were carried out in accordance with local and national VA guidelines and regulations for quality improvement activities. This study included virtual interviews with participants via MS Teams. Employees volunteered to participate in interviews and verbal consent was obtained to record interviews. Study materials, including interview guides with verbal consent procedures, were reviewed and approved by labor unions and determined as non-research by the VA Bedford Healthcare System Institutional Review Board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Prior presentations

Ball S, Kim B, Moldestad M, Molloy-Paolillo B, Cubanski L, Cutrona S, Sayre G, and Rinne S. (2022, June). Electronic Health Record Transition: Providers’ Experiences with Frustrated Patients. Poster presentation at the 2022 AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting. June 2022.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ball, S.L., Kim, B., Cutrona, S.L. et al. Clinician and staff experiences with frustrated patients during an electronic health record transition: a qualitative case study. BMC Health Serv Res 24 , 535 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-10974-5

Download citation

Received : 29 August 2023

Accepted : 09 April 2024

Published : 26 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-10974-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- EHR transition

- Patient experience

- Clinician experience

- Qualitative analysis

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

TIER 3 Interview Preparation. Key Points to Note. Interview Preparation. Energy! We need to be able to picture you with a bullhorn, getting hundreds of associates fired up to impact customers during peak season. Amazon is a data and metric driven company. You should keep your focus on the question asked and make sure your answer is tangible.

Assume associates work a ten (10) hour shift COMPLETE RESPONSES ON NEXT PAGE Tier 3 Case Study B Response Sheet Directions: After reading through the scenario on the previous page, please mplete the following problem. During your interview, the interviewers will ask you questions about your responses. Please take thenext ten (10) minutes to ...

A3). The current process takes 10 minutes where placing and delivering the order takes 2 minutes, selecting the bread takes 15 seconds, adding the meat to the sandwich takes 90 seconds, adding the vegetables and toppings takes 2 minutes, toasting the sandwich takes 2 minutes and 45 seconds, wrapping the sandwich takes 1 minute and delivering ...

Tier 3 Case Study: Collaboration is Key in Mitigation Planning Jeff Everett, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, Oregon . The information below is an accompaniment to the case study presented in the second half of Broadcast #1. This information describes in more detail the bank of curtailment hours concept

Tier 3 Instruction Within a Response to Intervention Framework "The biggest advantage is [helping] kids as soon ... Case Study: Data-Based Decision Making in Action Teachers at impson lementar chool use the lowchart on the folloin pae to assist the sitease team in main instructional ecisions ase on ata

study applications of the Tier 3 ... it has explicit representation of all EU member states, analyses for the 11 EU countries chosen as case ENV.C.1/SER/2007/0019 Restricted - Commercial ...

The information in this document is an accompaniment to the case study presented in the second half of the first Land-based Wind Energy Guidelines training broadcast (broadcast #1). This information describes in more detail the bank of curtailment hours concept and how those hours may be applied from our real-world project example.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

level (Tier 3), the selection of an appropriate and effective intervention requires in-depth study of factors contributing to or maintaining the child'sperformancedeficit.Thisprocess—alongwithprocedurestomon - itor and judge the success of interventions—is implemented in the form of a case study. CONTEXT AND HISTORY

Tier 3 Case Study B Response... Engineering & Technology. Industrial Engineering. Operations Management. Answered step-by-step. Solved by verified expert. Related Answered Questions. Q This assignment builds on the class example in complexity, but all the concepts apply. You are a business analyst mapp.

Case study of 3-Tier Architecture. What is Three-Tier Architecture? Three-tier architecture, as the name indicates, is hierarchical software architecture with three distinct, independent tiers or layers. Three-tier architecture is comprised of the following tiers: presentation, business and data access, in that order, and each tier has a ...

See a Tier 3 case study below. Case Study School of Pharmacy Modifies Curriculum to Improve Access to the National DPP Lifestyle Change Program. In 2019, a community-minded developer built a grocery store in a low-income food desert in Richmond, Virginia. The developer recognized that the neighborhood would also benefit from a community ...

It shows each step of tier 3 case study methods and how they relate to all other aspects of RTI.e, The case studies are relevant and incorporate the key elements of collaborative problem solving, data-based decision making, logical linkage between the stages, and fidelity of case study procedures. This is an excellent resource for educators.

Expect 3-6 total questions from each interviewer and 2+ follow up questions on each behavioral questions. That was what I experienced for an AM interview recently. Also, search the internal "Inside Amazon" for "Interview" and it should pull up the interview questions bank. 1. Share.

This detailed guide to tier 3 of the RTI model provides school psychologists and RTI teams with a case study approach to conducting intensive, comprehensive student evaluations. With step-by-step guidelines for Grades K-12, this resource demonstrates how to develop a specific case study for students who are struggling in the general classroom.

study would examine the relationship between an intervention and a relevant outcome. Tier 3 and educational technology use in schools. Information from Tier 4 activities (e.g., review of existing evidence) can be used to develop a Tier 3 study plan for using and evaluating educational technologies in schools. To build Tier 3 evidence,

outcome, along with Tiers 1 and 2, is for the student to achieve Tier 1 proficiency levels. Tier 3 Case Study . Using a task-specific CBM, the teacher found that the student continued to make computational errors due to his lack of conceptual understanding of finding a common denominator. The math coach suggested utilizing a representation that

example of Tier 3, special education instruction is a special education teacher collaboratively teaching reading to an inclusive classroom where students with disabilities receive intensive ... case study; (b) experimental study; (c) focus group; (d); survey; or (e) meta-analysis. Finally, the researchers coded the remaining articles for RTI

This detailed guide to tier 3 of the RTI model provides school psychologists and RTI teams with a case study approach to conducting intensive, comprehensive student evaluations. With step-by-step guidelines for Grades K-12, this resource demonstrates how to develop a specific case study for students who are struggling in the general classroom.

This qualitative case study was situated within a larger multi-methods evaluation of the EHR transition. We conducted a total of 122 interviews with 30 clinicians and staff across disciplines at the initial VA EHR transition site before, immediately after, and up to 12 months after go-live (September 2020-November 2021). ...

COMPLETE RESPONSES ON NEYT DACE Tier 3 Case Study B Response Sheet Directions: After reading through the scenario on the previous page, please complete the following problem. During your interview, the interviewers will ask you questions about your responses. Please take the next ten (10) minutes to complete the questions below.

Visit our website at http://www.pattan.netThis session will provide an overview of Tier 3 problem-solving associated with early reading difficulties and disa...

Bayonet786. • 4 yr. ago. Being studying in tier 3 college (ECE branch), I would say, its worth doing engineering only if done from a atleast tier 2 college. I seriously regret doing btech in tier 3 college. Its not worth the money and hassle ( in my college, you will only find retards playing PUBG all the time, nothing else).