- Our Mission

Making Learning Relevant With Case Studies

The open-ended problems presented in case studies give students work that feels connected to their lives.

To prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet, we need to teach them how to be great problem solvers so that they’ll be ready for anything. One way to do this is by teaching content and skills using real-world case studies, a learning model that’s focused on reflection during the problem-solving process. It’s similar to project-based learning, but PBL is more focused on students creating a product.

Case studies have been used for years by businesses, law and medical schools, physicians on rounds, and artists critiquing work. Like other forms of problem-based learning, case studies can be accessible for every age group, both in one subject and in interdisciplinary work.

You can get started with case studies by tackling relatable questions like these with your students:

- How can we limit food waste in the cafeteria?

- How can we get our school to recycle and compost waste? (Or, if you want to be more complex, how can our school reduce its carbon footprint?)

- How can we improve school attendance?

- How can we reduce the number of people who get sick at school during cold and flu season?

Addressing questions like these leads students to identify topics they need to learn more about. In researching the first question, for example, students may see that they need to research food chains and nutrition. Students often ask, reasonably, why they need to learn something, or when they’ll use their knowledge in the future. Learning is most successful for students when the content and skills they’re studying are relevant, and case studies offer one way to create that sense of relevance.

Teaching With Case Studies

Ultimately, a case study is simply an interesting problem with many correct answers. What does case study work look like in classrooms? Teachers generally start by having students read the case or watch a video that summarizes the case. Students then work in small groups or individually to solve the case study. Teachers set milestones defining what students should accomplish to help them manage their time.

During the case study learning process, student assessment of learning should be focused on reflection. Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick’s Learning and Leading With Habits of Mind gives several examples of what this reflection can look like in a classroom:

Journaling: At the end of each work period, have students write an entry summarizing what they worked on, what worked well, what didn’t, and why. Sentence starters and clear rubrics or guidelines will help students be successful. At the end of a case study project, as Costa and Kallick write, it’s helpful to have students “select significant learnings, envision how they could apply these learnings to future situations, and commit to an action plan to consciously modify their behaviors.”

Interviews: While working on a case study, students can interview each other about their progress and learning. Teachers can interview students individually or in small groups to assess their learning process and their progress.

Student discussion: Discussions can be unstructured—students can talk about what they worked on that day in a think-pair-share or as a full class—or structured, using Socratic seminars or fishbowl discussions. If your class is tackling a case study in small groups, create a second set of small groups with a representative from each of the case study groups so that the groups can share their learning.

4 Tips for Setting Up a Case Study

1. Identify a problem to investigate: This should be something accessible and relevant to students’ lives. The problem should also be challenging and complex enough to yield multiple solutions with many layers.

2. Give context: Think of this step as a movie preview or book summary. Hook the learners to help them understand just enough about the problem to want to learn more.

3. Have a clear rubric: Giving structure to your definition of quality group work and products will lead to stronger end products. You may be able to have your learners help build these definitions.

4. Provide structures for presenting solutions: The amount of scaffolding you build in depends on your students’ skill level and development. A case study product can be something like several pieces of evidence of students collaborating to solve the case study, and ultimately presenting their solution with a detailed slide deck or an essay—you can scaffold this by providing specified headings for the sections of the essay.

Problem-Based Teaching Resources

There are many high-quality, peer-reviewed resources that are open source and easily accessible online.

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science at the University at Buffalo built an online collection of more than 800 cases that cover topics ranging from biochemistry to economics. There are resources for middle and high school students.

- Models of Excellence , a project maintained by EL Education and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has examples of great problem- and project-based tasks—and corresponding exemplary student work—for grades pre-K to 12.

- The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning at Purdue University is an open-source journal that publishes examples of problem-based learning in K–12 and post-secondary classrooms.

- The Tech Edvocate has a list of websites and tools related to problem-based learning.

In their book Problems as Possibilities , Linda Torp and Sara Sage write that at the elementary school level, students particularly appreciate how they feel that they are taken seriously when solving case studies. At the middle school level, “researchers stress the importance of relating middle school curriculum to issues of student concern and interest.” And high schoolers, they write, find the case study method “beneficial in preparing them for their future.”

Center for Teaching

Case studies.

Print Version

Case studies are stories that are used as a teaching tool to show the application of a theory or concept to real situations. Dependent on the goal they are meant to fulfill, cases can be fact-driven and deductive where there is a correct answer, or they can be context driven where multiple solutions are possible. Various disciplines have employed case studies, including humanities, social sciences, sciences, engineering, law, business, and medicine. Good cases generally have the following features: they tell a good story, are recent, include dialogue, create empathy with the main characters, are relevant to the reader, serve a teaching function, require a dilemma to be solved, and have generality.

Instructors can create their own cases or can find cases that already exist. The following are some things to keep in mind when creating a case:

- What do you want students to learn from the discussion of the case?

- What do they already know that applies to the case?

- What are the issues that may be raised in discussion?

- How will the case and discussion be introduced?

- What preparation is expected of students? (Do they need to read the case ahead of time? Do research? Write anything?)

- What directions do you need to provide students regarding what they are supposed to do and accomplish?

- Do you need to divide students into groups or will they discuss as the whole class?

- Are you going to use role-playing or facilitators or record keepers? If so, how?

- What are the opening questions?

- How much time is needed for students to discuss the case?

- What concepts are to be applied/extracted during the discussion?

- How will you evaluate students?

To find other cases that already exist, try the following websites:

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science , University of Buffalo. SUNY-Buffalo maintains this set of links to other case studies on the web in disciplines ranging from engineering and ethics to sociology and business

- A Journal of Teaching Cases in Public Administration and Public Policy , University of Washington

For more information:

- World Association for Case Method Research and Application

Book Review : Teaching and the Case Method , 3rd ed., vols. 1 and 2, by Louis Barnes, C. Roland (Chris) Christensen, and Abby Hansen. Harvard Business School Press, 1994; 333 pp. (vol 1), 412 pp. (vol 2).

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

Do Your Students Know How to Analyze a Case—Really?

Explore more.

- Case Teaching

- Student Engagement

J ust as actors, athletes, and musicians spend thousands of hours practicing their craft, business students benefit from practicing their critical-thinking and decision-making skills. Students, however, often have limited exposure to real-world problem-solving scenarios; they need more opportunities to practice tackling tough business problems and deciding on—and executing—the best solutions.

To ensure students have ample opportunity to develop these critical-thinking and decision-making skills, we believe business faculty should shift from teaching mostly principles and ideas to mostly applications and practices. And in doing so, they should emphasize the case method, which simulates real-world management challenges and opportunities for students.

To help educators facilitate this shift and help students get the most out of case-based learning, we have developed a framework for analyzing cases. We call it PACADI (Problem, Alternatives, Criteria, Analysis, Decision, Implementation); it can improve learning outcomes by helping students better solve and analyze business problems, make decisions, and develop and implement strategy. Here, we’ll explain why we developed this framework, how it works, and what makes it an effective learning tool.

The Case for Cases: Helping Students Think Critically

Business students must develop critical-thinking and analytical skills, which are essential to their ability to make good decisions in functional areas such as marketing, finance, operations, and information technology, as well as to understand the relationships among these functions. For example, the decisions a marketing manager must make include strategic planning (segments, products, and channels); execution (digital messaging, media, branding, budgets, and pricing); and operations (integrated communications and technologies), as well as how to implement decisions across functional areas.

Faculty can use many types of cases to help students develop these skills. These include the prototypical “paper cases”; live cases , which feature guest lecturers such as entrepreneurs or corporate leaders and on-site visits; and multimedia cases , which immerse students into real situations. Most cases feature an explicit or implicit decision that a protagonist—whether it is an individual, a group, or an organization—must make.

For students new to learning by the case method—and even for those with case experience—some common issues can emerge; these issues can sometimes be a barrier for educators looking to ensure the best possible outcomes in their case classrooms. Unsure of how to dig into case analysis on their own, students may turn to the internet or rely on former students for “answers” to assigned cases. Or, when assigned to provide answers to assignment questions in teams, students might take a divide-and-conquer approach but not take the time to regroup and provide answers that are consistent with one other.

To help address these issues, which we commonly experienced in our classes, we wanted to provide our students with a more structured approach for how they analyze cases—and to really think about making decisions from the protagonists’ point of view. We developed the PACADI framework to address this need.

PACADI: A Six-Step Decision-Making Approach

The PACADI framework is a six-step decision-making approach that can be used in lieu of traditional end-of-case questions. It offers a structured, integrated, and iterative process that requires students to analyze case information, apply business concepts to derive valuable insights, and develop recommendations based on these insights.

Prior to beginning a PACADI assessment, which we’ll outline here, students should first prepare a two-paragraph summary—a situation analysis—that highlights the key case facts. Then, we task students with providing a five-page PACADI case analysis (excluding appendices) based on the following six steps.

Step 1: Problem definition. What is the major challenge, problem, opportunity, or decision that has to be made? If there is more than one problem, choose the most important one. Often when solving the key problem, other issues will surface and be addressed. The problem statement may be framed as a question; for example, How can brand X improve market share among millennials in Canada? Usually the problem statement has to be re-written several times during the analysis of a case as students peel back the layers of symptoms or causation.

Step 2: Alternatives. Identify in detail the strategic alternatives to address the problem; three to five options generally work best. Alternatives should be mutually exclusive, realistic, creative, and feasible given the constraints of the situation. Doing nothing or delaying the decision to a later date are not considered acceptable alternatives.

Step 3: Criteria. What are the key decision criteria that will guide decision-making? In a marketing course, for example, these may include relevant marketing criteria such as segmentation, positioning, advertising and sales, distribution, and pricing. Financial criteria useful in evaluating the alternatives should be included—for example, income statement variables, customer lifetime value, payback, etc. Students must discuss their rationale for selecting the decision criteria and the weights and importance for each factor.

Step 4: Analysis. Provide an in-depth analysis of each alternative based on the criteria chosen in step three. Decision tables using criteria as columns and alternatives as rows can be helpful. The pros and cons of the various choices as well as the short- and long-term implications of each may be evaluated. Best, worst, and most likely scenarios can also be insightful.

Step 5: Decision. Students propose their solution to the problem. This decision is justified based on an in-depth analysis. Explain why the recommendation made is the best fit for the criteria.

Step 6: Implementation plan. Sound business decisions may fail due to poor execution. To enhance the likeliness of a successful project outcome, students describe the key steps (activities) to implement the recommendation, timetable, projected costs, expected competitive reaction, success metrics, and risks in the plan.

“Students note that using the PACADI framework yields ‘aha moments’—they learned something surprising in the case that led them to think differently about the problem and their proposed solution.”

PACADI’s Benefits: Meaningfully and Thoughtfully Applying Business Concepts

The PACADI framework covers all of the major elements of business decision-making, including implementation, which is often overlooked. By stepping through the whole framework, students apply relevant business concepts and solve management problems via a systematic, comprehensive approach; they’re far less likely to surface piecemeal responses.

As students explore each part of the framework, they may realize that they need to make changes to a previous step. For instance, when working on implementation, students may realize that the alternative they selected cannot be executed or will not be profitable, and thus need to rethink their decision. Or, they may discover that the criteria need to be revised since the list of decision factors they identified is incomplete (for example, the factors may explain key marketing concerns but fail to address relevant financial considerations) or is unrealistic (for example, they suggest a 25 percent increase in revenues without proposing an increased promotional budget).

In addition, the PACADI framework can be used alongside quantitative assignments, in-class exercises, and business and management simulations. The structured, multi-step decision framework encourages careful and sequential analysis to solve business problems. Incorporating PACADI as an overarching decision-making method across different projects will ultimately help students achieve desired learning outcomes. As a practical “beyond-the-classroom” tool, the PACADI framework is not a contrived course assignment; it reflects the decision-making approach that managers, executives, and entrepreneurs exercise daily. Case analysis introduces students to the real-world process of making business decisions quickly and correctly, often with limited information. This framework supplies an organized and disciplined process that students can readily defend in writing and in class discussions.

PACADI in Action: An Example

Here’s an example of how students used the PACADI framework for a recent case analysis on CVS, a large North American drugstore chain.

The CVS Prescription for Customer Value*

PACADI Stage

Summary Response

How should CVS Health evolve from the “drugstore of your neighborhood” to the “drugstore of your future”?

Alternatives

A1. Kaizen (continuous improvement)

A2. Product development

A3. Market development

A4. Personalization (micro-targeting)

Criteria (include weights)

C1. Customer value: service, quality, image, and price (40%)

C2. Customer obsession (20%)

C3. Growth through related businesses (20%)

C4. Customer retention and customer lifetime value (20%)

Each alternative was analyzed by each criterion using a Customer Value Assessment Tool

Alternative 4 (A4): Personalization was selected. This is operationalized via: segmentation—move toward segment-of-1 marketing; geodemographics and lifestyle emphasis; predictive data analysis; relationship marketing; people, principles, and supply chain management; and exceptional customer service.

Implementation

Partner with leading medical school

Curbside pick-up

Pet pharmacy

E-newsletter for customers and employees

Employee incentive program

CVS beauty days

Expand to Latin America and Caribbean

Healthier/happier corner

Holiday toy drives/community outreach

*Source: A. Weinstein, Y. Rodriguez, K. Sims, R. Vergara, “The CVS Prescription for Superior Customer Value—A Case Study,” Back to the Future: Revisiting the Foundations of Marketing from Society for Marketing Advances, West Palm Beach, FL (November 2, 2018).

Results of Using the PACADI Framework

When faculty members at our respective institutions at Nova Southeastern University (NSU) and the University of North Carolina Wilmington have used the PACADI framework, our classes have been more structured and engaging. Students vigorously debate each element of their decision and note that this framework yields an “aha moment”—they learned something surprising in the case that led them to think differently about the problem and their proposed solution.

These lively discussions enhance individual and collective learning. As one external metric of this improvement, we have observed a 2.5 percent increase in student case grade performance at NSU since this framework was introduced.

Tips to Get Started

The PACADI approach works well in in-person, online, and hybrid courses. This is particularly important as more universities have moved to remote learning options. Because students have varied educational and cultural backgrounds, work experience, and familiarity with case analysis, we recommend that faculty members have students work on their first case using this new framework in small teams (two or three students). Additional analyses should then be solo efforts.

To use PACADI effectively in your classroom, we suggest the following:

Advise your students that your course will stress critical thinking and decision-making skills, not just course concepts and theory.

Use a varied mix of case studies. As marketing professors, we often address consumer and business markets; goods, services, and digital commerce; domestic and global business; and small and large companies in a single MBA course.

As a starting point, provide a short explanation (about 20 to 30 minutes) of the PACADI framework with a focus on the conceptual elements. You can deliver this face to face or through videoconferencing.

Give students an opportunity to practice the case analysis methodology via an ungraded sample case study. Designate groups of five to seven students to discuss the case and the six steps in breakout sessions (in class or via Zoom).

Ensure case analyses are weighted heavily as a grading component. We suggest 30–50 percent of the overall course grade.

Once cases are graded, debrief with the class on what they did right and areas needing improvement (30- to 40-minute in-person or Zoom session).

Encourage faculty teams that teach common courses to build appropriate instructional materials, grading rubrics, videos, sample cases, and teaching notes.

When selecting case studies, we have found that the best ones for PACADI analyses are about 15 pages long and revolve around a focal management decision. This length provides adequate depth yet is not protracted. Some of our tested and favorite marketing cases include Brand W , Hubspot , Kraft Foods Canada , TRSB(A) , and Whiskey & Cheddar .

Art Weinstein , Ph.D., is a professor of marketing at Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, Florida. He has published more than 80 scholarly articles and papers and eight books on customer-focused marketing strategy. His latest book is Superior Customer Value—Finding and Keeping Customers in the Now Economy . Dr. Weinstein has consulted for many leading technology and service companies.

Herbert V. Brotspies , D.B.A., is an adjunct professor of marketing at Nova Southeastern University. He has over 30 years’ experience as a vice president in marketing, strategic planning, and acquisitions for Fortune 50 consumer products companies working in the United States and internationally. His research interests include return on marketing investment, consumer behavior, business-to-business strategy, and strategic planning.

John T. Gironda , Ph.D., is an assistant professor of marketing at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. His research has been published in Industrial Marketing Management, Psychology & Marketing , and Journal of Marketing Management . He has also presented at major marketing conferences including the American Marketing Association, Academy of Marketing Science, and Society for Marketing Advances.

Related Articles

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

- Board of Directors

- National Advisory Board

- OUR RESOURCES

- OUR STORIES

- Our Newsletters

Case Study Compilation

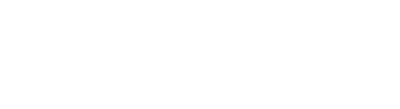

The SEL Integration Approach Case Study Compilation was developed with and for educators who work in a K-12 school setting, including teachers, paraprofessionals, counselors, SEL Directors, teacher leaders, & school principals, to provide examples of practice related to three questions:

- What does it mean to focus on social-emotional development and the creation of positive learning environments?

- How can educators integrate their approaches to social, emotional, and academic development?

- What does it look, sound, and feel like when SEL is effectively embedded into all elements of the school day?

When read one at a time, the case studies offer snapshots of social-emotional learning in action; they describe daily routines, activities, and teachable moments within short vignettes. When read together, the case studies provide a unique picture of what it takes for a school to integrate social, emotional, and academic learning across grade levels, content areas, and other unique contexts.

The Case Study Compilation includes:

- Eleven case studies: Each case study highlights educator ‘moves’ and strategies to embed social-emotional skills, mindsets, and competencies throughout the school day and within academics. They each conclude with a reflection prompt that challenges readers to examine their own practice. The case studies are written from several different perspectives, including teachers in the classroom and in distance learning environments, a school counselor, and district leaders.

- Reflection Guide for Professional Learning: The Reflection Guide offers an entry point for educators to think critically about their work with youth in order to strengthen their practice. School leaders or other partners may choose to use this Reflection Guide in a variety of contexts, including coaching conversations and staff professional development sessions.

View our accompanying Quick Reference Guide , Companion Guides , and Educator & School Leader Self-Reflection Tools .

“We must resist thinking in siloed terms when it comes to social-emotional learning (SEL), academics, and equity. Rather, these elements of our work as educators and partners go hand in hand.”

HEAD & HEART, TransformEd & ANet

Get the Latest Updates

© Copyright 2020 Transforming Education. All content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

Transforming Education is a registered 501(c)3 based in Boston, Massachusetts

Recent Tweet

Take action.

The Center for Global Studies

Sample case studies, page table of contents, case study #1.

Sophia A. McClennen

Cultural Connections for Younger Students: A Party for a Japanese Refugee

On Friday, March 11, 2011 an earthquake hit Japan and caused a series of Tsunami waves. It was the largest earthquake in the history of Japan and it caused a lot of damage. Homes were lost, people were hurt, and many had to find other places to stay since the places where they lived were no longer safe. Some Japanese families even had to move to other countries, at least temporarily. Your teacher has just told you that a little girl from Japan will be coming soon to join your class at your school. Her name is Bachiko, which means “happy child” in Japanese. She is moving to State College with her parents and younger brother.

Your teacher tells you that the first day she will be in class will be May 5. In Japan May 5 is children’s day and the whole country celebrates children and their mothers. But for Bachiko May 5 is even more special since it is also her birthday. Since she will be here the class thinks that you should all plan a celebration for her. She won’t know anyone here yet. She won’t have any friends yet. And, even though she speaks some English, she is more comfortable speaking Japanese. You want to help her celebrate Children’s Day and her birthday and you also want to help her feel welcome since she will probably be missing her home very much. You want to make sure that the party includes some of the sorts of things that kids do in Japan. How can you plan the party? How can you help her celebrate her special day?

Global Knowledge/Global Empathy:

Asking the right questions:.

Begin by asking questions that help your students connect with Bachiko’s story. Ask them to think of holidays they celebrate that they would miss if they had to go to a different country during that time of year.

Ask them to think of how they would feel if they had to be far from home for their birthday. What sorts of things would they miss? What sorts of things would they be able to do in a new place?

Adjusting the conversation based on the maturity of the class, talk about the challenges to Bachiko of having to move to a new place. Ask them about what they think of moving and what sorts of challenges moving brings—compare moving to another place in the country where you currently live to moving to a new country.

Talk about natural disasters. Ask them if there are times when they feel scared of them and discuss ways for them to reduce their fears. Talk about how they happen all over the globe. Make sure not to let them think that they only happen in places like Japan.

Gathering information:

Brainstorm with the class the sort of information they need in order to plan the party (solve the problem). Create a list of things that the class needs to learn to be able to do this.

Create a list of things that the kids need to learn about Japanese culture. Ask the kids to think of any Japanese culture that they already know of (sushi, animation, pokemon, origami, etc.). Ask them to consider whether their experience of these cultural items might be different from how Bachiko and her friends experience them.

Depending on the class—consider teaching more about earthquakes, tsunamis, and other natural disasters. Use this as a chance to balance learning about sciences with learning compassion for those that are affected by these events. Consider talking about Katrina or other US natural disasters (tornadoes) so that they don’t think these things only happen to others.

Imagining a way to address the problem:

Once you have begun to gather materials and information that can help the class imagine the party that they would like to throw, have them begin to describe what they want to do for the party. Do they need to make origami, kites, etc? What foods? Music? What other activities? Help them imagine all of these things.

Then ask them to imagine the party and think of how they would like to tell a story about it. Asking them to be the storytellers of this will help encourage their imagination and empathy. (While possibly throwing the party would be a fun idea—it might not be the best learning activity and could be difficult to do). Do they want to write a story about Bachiko and the party? Do they want to create a cartoon/animated version? Do they want to make a series of pictures? Consider whether you want them to work in groups or individually or in some combination. Group work is generally helpful for these types of projects. Maybe you make a few groups and let each one decide between a story, pictures, an origami play, etc… There are lots of options.

When the students have their projects complete have them present them to the class. Then have the whole class talk about the strengths and weaknesses of their projects. What do they think Bachiko would have liked most? What might have been hard for her? What parts were fun for them to plan? What parts were hard? The idea here is to make it clear that they have done good work, that they imagined a way to help someone else, but that it would not be possible to “fix” the situation. Bachiko would surely be a bit sad—but their party would also surely really help. And the more the party made her feel welcome, the more of a success it would be.

Next ask the class to engage in some sort of fundraising or other project to help the kids in Japan. Now, when they do this, they will feel much more connected to the communities they are trying to help.

Assessment:

There should always be some assessment with these projects. It is possible to determine how well students gathered information, whether they asked good questions, and whether they could appreciate the limits to their work as well as its strengths.

Asks students to imagine a direct connection with a young Japanese earthquake victim—which creates a greater link. Makes the crisis in Japan more real.

Asks them to imagine themselves in a similar situation—this will deter othering (the idea that this situation would only happen to others).

Gives them an opportunity to learn more about Japan through their own interest in solving a problem.

Risks making them feel sorry for Bachiko in a way that might make her seem helpless. You can teach in ways that confront this tendency.

Risks developing a negative stereotype of Japan—since it could seem like a country that suffers disasters and needs our help. You can teach in ways that confront this tendency by not allowing them to describe Japan in negative terms.

Adaptations:

This case study could be adjusted to describe a child from almost any other nation that had to suddenly move to your school district. The possibilities are limitless.

Web resources:

- Teaching Kids About Earthquakes, Tsunamis, and Japan Through Online Resources

- Talking to kids about the Earthquake

- The Science of Earthquakes (for kids)

- Kids web Japan

- Japan for kids

Case Study #2

Environmental connections for middle school age students: global sustainability and the brazilian amazon.

Your name is Jorge, you are 13, and you are from Brazil. You live in the Amazon in a community of Seringueiros— Seringueiro is the Portuguese word for “rubber tapper.” Rubber tapping has been a traditional way of life for many people living in the Amazon forest since the start of the century. A cut is made in the side of a rubber tree then the rubber is harvested. Later the tree heals and the rubber tapper sells the rubber to buy things they need. Life as a seringueiro is not easy. It is difficult to make money selling the rubber and many in these communities struggle to make a good life. Lately, though, it has gotten worse.

Jorge’s family and his community have just learned that a logging company plans to cut down the trees that they use to get rubber. Jorge’s parents are tired of fighting the logging company and they are thinking of moving to the city. But Jorge has heard stories that life in the city would be even harder for them and he doesn’t want to leave the forest. Instead, he wants to think of a way to protect the trees that his family needs for rubber. He wants to work to find a way to allow his community to continue living in harmony with nature. He thinks that he will hate living in the city and he wants to continue living in the ways that his community has for decades.

Jorge realizes that saving the trees for rubber tappers probably won’t convince the Brazilian government to protect them. Native Americans throughout the hemisphere have seen their lands taken away and their way of life threatened for centuries—and very few people have come to their defense. But he thinks that maybe he can get attention to saving his community’s trees if he reminds the public of the importance of the plant life in the Amazon. He also thinks that he has a greater chance of getting attention to his community’s problem if he links with other kids his age from other parts of the world.

He thinks that if they work together they can make a difference. He thinks that if kids from various places draw attention to this problem, and if he gets help from environmentalists, he can convince the Brazilian government to protect the lands.

The Amazon rainforest is one of the world’s greatest natural resources. Its many plants recycle carbon dioxide into oxygen, and some call it “Lungs of our Planet” since 20% of earth oxygen is produced by the Amazon rainforest. Even though environmentalists and government policies forced the world to give more attention to the rain forest, deforestation continues to be a major problem. Predications show that if nothing is done to stop the destruction of rainforest that half our remaining rain forests will be gone by the year 2025 and by 2060 there will be no rain forests remaining.

Not only does the Amazon provide oxygen, it is the home to a great variety of plant life that holds the potential to help solve many medical problems. Protecting this biodiversity is also of great importance. The plants in the Amazon could help us discover the next cure for cancer or for other diseases. The oxygen produced in the Amazon helps people all over the world to breathe.

Put yourself in the place of Jorge and imagine how he might solve this problem. How can he get help protecting the trees his family needs? Should he start an environmental activism campaign? How could

he do that? He will need to connect with others outside his community. Could you imagine ways that your own school might help him? Design a strategy to help Jorge protect the rainforest.

Begin by asking questions that help your students connect with Jorge’s story. Ask them to think of what they would do if a company was taking over the lands they lived on.

Ask them to think about the value of protecting traditional ways of life. Does their family have traditions that sometimes seem threatened based on the way that society has changed? And how are their experiences related to those of Jorge, whose community has a very traditional way of living? Does Jorge have a right to have that way of life protected? Do we have an obligation to help protect it?

Ask them to think about how hard it will be for Jorge to get attention to his cause. What are the challenges he faces? How can Jorge connect his cause to the lives of people living outside the rain forest? The rainforest is important to everyone’s heath—but few people know that or care. How can that change?

Talk about environmental issues. Ask them about what they do to help conserve the planet’s resources. Ask them to think about how environmental issues link people across the globe. Ask them to think about the sorts of communities that tend to be most threatened by things like deforestation. Are their problems exacerbated by having a less publicly recognized voice? Also ask them to think about how hard it is to get people to change the way that they live—even when they know that some of their habits are bad for the planet.

Talk about sustainability. Jorge’s community as a sustainable connection to the land. It does not take in a way that causes damage or limits regeneration. What are some ways that our students can live a sustainable life? How can we learn from communities like Jorge’s? What gets lost if those communities cease to exist?

Brainstorm with the class the sort of information they need in order to help Jorge. They need to learn about rubber tapping, the Amazon, deforestation, environmental activism, sustainability. Create a list of things that the class needs to learn to be able to do this.

Create a list of things that the kids need to learn about Brazilian Native American culture. Ask them to think of things that they know about Native Americans in the United States and then ask them to think of way that these communities face similar challenges across the Americas.

Ask them to think about how the crisis in the Amazon links to environmental crises in the United States. Do they know about the Marellus Shale story? How might that story be similar to that of Jorge’s?

Once you have begun to gather materials and information that can help the class imagine Jorge’s situation, have them begin to describe a plan for Jorge. How can Jorge gain support? He can’t do it alone—so who would be good to help him? What sorts of information does he need to present to get supporters for this? How can he best connect with people outside of his community? Help them imagine all of these things.

Next have them implement a campaign to save the rainforest where Jorge lives. Consider whether you want them to work in groups or individually or in some combination. Group work is generally helpful for these types of projects. Do they want to do posters, hold events, make a movie, write a book, get articles in newspapers, host a website, etc….? How can they best get attention for the cause? There are lots of options.

When the students have their project concepts complete have them present them to the class. They do not need to actually make the posters, websites, etc…they just need to describe them and create an example. Then have the whole class talk about the strengths and weaknesses of their projects. What parts of Jorge’s action plan were fun for them to work on? What parts were hard? The idea here is to make it clear that they have done good work, that they imagined a way to help someone else, but that it would not be possible to “fix” the situation.

The class should then discuss the merits of each of the ideas that the teams came up with –and they could follow through on creating some resources that exemplified some of the approaches the class thought worked best.

Next ask the class to engage in some sort of project to raise awareness for an environmental issue—especially one linked to protecting forests. Ask them to consider a project to advance sustainable living.

Asks students to imagine a direct connection with a Brazilian Native American—which creates a greater link. Makes the social and environmental crisis more real.

Asks them to imagine themselves in a similar situation—this will deter othering.

Gives them an opportunity to learn more about the Amazon and Brazilians through their own interest in solving a problem.

Risks making them feel sorry for Jorge in a way that might make him seem helpless. You can teach in ways that confront this tendency.

Risks developing a negative stereotype of Brazil—since it could seem like the Brazilian government doesn’t care about the Amazon or the rubber tappers. You can teach in ways that confront this tendency by not allowing them to describe Brazil in negative terms and by reminding them of how this problem has global examples.

This case study could be adjusted to describe an environmental conflict from another region. The possibilities are limitless.

- Amazon rubber tappers news

- Amazon rainforest

Case Study #3

The impact of war on children for high school age students: landmines in angola.

Mia is 16 years old and she is from Angola. Last week her brother, Nelson, was playing soccer with friends when he chased after the ball and went on lands that they are warned never to step on. He was too busy chasing the ball to pay attention to the rule. As he crossed over into the dangerous territory he heard a click, then an explosion. He had stepped on a land mine. He was rushed to a hospital where Mia and her family went to see him. Once they arrived they learned that Nelson had lost both legs in the explosion. Nelson is now one of the more than 100,000 Angolans who have lost a limb to landmines.

Angola suffered a civil war that ended in 1994, but, even though the war ended that year, the effects of it are still in place. There are estimates of between 10 and 20 landmines in Angola which is equal to approximately 1-2 landmines per inhabitant. As mentioned, over 100,000 Angolans have lost a limb due to a landmine and 120 Angolans die from a landmine explosion every month. But the negative effects of landmines on the population go beyond injuries: the threat of landmines restricts the ability of people to move about their country, to farm, to find clean water, to go to school, and –as in Nelson’s case—to play games like soccer. Women and children are most threatened by landmines and children represent 49% of the landmine injuries in Angola. During the Soviet war in Afghanistan during the 1980s the Soviets used landmines that looked to children like toys. Many were killed trying to pick them up. Even though the UN passed a moratorium on landmines in 1993, there is still no international consensus on banning the use of landmines. Currently there are 20 mines laid for each one removed.

Landmines only cost about $3 to make, but they cost about $1,000 each to remove. Mia has watched her community suffer life with landmines for too long. She wants to work to change this problem, but she realizes that the cost of removing landmines is very high. She knows that anti-landmine groups help to de-mine areas, but she doesn’t want to wait for help from others, she thinks her community needs to learn more about how to de-mine. She has another problem, too, she has learned that landmines continue to be used and she wants to work to stop the use of landmines in other countries. There are over 110 million landmines (and millions of other explosive devices) in 68 nations today. She wants to work to stop the future placement of more mines.

Put yourself in the place of Mia and imagine how she might solve this problem. How can she get help de-mining her community? Should she attempt to get de-miners to her area or she should work to see if some of the members of her community could learn de-mining techniques? How could she do that? She also wants to raise awareness about landmines globally so that this practice can stop. Can you imagine a project with your school that could help her in that goal? Design a strategy to help Mia stop landmine damage.

Begin by asking questions that help students connect with Mia’s story. Ask them to think of what they would do if a sibling or cousin or friend was hurt in this way.

Ask them to think about the impact of war on children. The case of landmines is a clear example of how current military techniques often target civilian populations and they do so through devices that can be left and that do not require military personnel to maintain. How has that changed the nature of war? Should there be a ban on landmines? What would be some good ways to advance this cause? It might be useful to review the Geneva Conventions with students since they are war guidelines that create protections for civilians.

A further issue is the way that the landmines cause Mia’s community to depend on others. De- mining is complex work and it takes a lot of training. Most of the time de-mining crews will come to a community, work, then leave. What are the challenges to changing that process and giving more local communities these skills and the equipment needed to perform them safely? Similarly some believe that the 12 nations that participated in Angola’s Civil War by providing the mines should also be responsible for getting rid of them. Who should get rid of the mines? What are some ways that the community can be an active part of this process?

Ask students to think about how hard it will be for Mia to get attention to her cause. What are the challenges she faces? How can Mia connect her cause to the lives of people living outside of Angola or Africa? What would it take to get people living in the United States to care about Mia’s situation? The US is home to more than 15 landmine producers. Should efforts be made to shut down their operations?

Ask them to think about the long term effects of war on communities. A number of nations in the world have been engaged in long term conflicts, with children that have lived their whole lives during military conflict. How does that influence the lives of children? How does that affect a community’s ability to prosper? What will happen to kids like Nelson as they grow up?

Brainstorm with the class the sort of information they need in order to help Mia. They need to learn about landmines, the politics of de-mining, the current efforts to ban landmines, and the human rights of children in a time of war. Create a list of things that the class needs to learn to be able to do this.

Create a list of things that the students need to learn about Angolan society and history. In order to appreciate Mia’s situation it is important that students empathize with her without seeing her as a helpless victim. What happened during the Civil War? Why did the United States and the Soviet Union get involved? How was their involvement a result of Cold War dynamics? Teach students about the idea of proxy wars and ask them to think about the political implications such wars have on the nations where the wars are waged.

Ask them to think about how the landmine crisis is a geopolitical problem that is not just limited to Angola. Have the class learn about the use of landmines in other countries and ask them to think about how landmines play a role in contemporary military conflicts.

Once you have begun to gather materials and information that can help the class imagine Mia’s situation, have them begin to describe a plan for Mia. How can Mia gain support? How can Mia

help her community and get help? She can’t do it alone—so who would be good to help her? What sorts of information does she need to present to get supporters for her cause? How can she best connect with people outside of her community? Help them imagine all of these things.

Next have them implement a campaign to get resources to de-mine the area where Mia lives and/or to assist the international anti-landmine project. Consider whether you want them to work in groups or individually or in some combination. Group work is generally helpful for these types of projects. Do they want to do posters, hold events, make a movie, write a book, get articles in newspapers, host a website, etc….? How can they best get attention for the cause?

There are lots of options.

When the students have their project concepts complete have them present them to the class. They do not need to actually make the posters, websites, etc…they just need to describe them, include examples, and possibly write up a report. The amount of actual materials they provide can be adjusted based on time and resources.

Then have the whole class talk about the strengths and weaknesses of their projects. What parts of Mia’s action plan were easier to solve? What parts were harder? The idea here is to make it clear that they have done good work, that they imagined a way to help someone else, but that it would not be possible to “fix” the situation. Nelson won’t get his legs back, but possibly this project could save another boy.

The class should then discuss the merits of each of the ideas that the teams came up with –and they could follow through on creating some resources that exemplified some of the approaches the class thought worked best. Having open conversations with the class about the pros and cons of each project teaches students to appreciate that complex problems require complex solutions.

Next ask the class to engage in some sort of project to raise awareness of the damages caused by landmines. Ask them to consider a project to advance efforts to ban landmines and/or to support de-mining in Angola.

Asks students to imagine a direct connection with an Angolan—which creates a greater link. Makes the social and political crisis more real.

Gives them an opportunity to learn more about landmines, the effects of war on children, and Angola through their own interest in solving a problem.

Teaches them to appreciate the complexity of these types of problems and the fact that they do not have easy solutions. Teaches them that it is important to work to solve problems even when these can’t be easily fixed.

Risks making them feel sorry for Mia and Nelson in a way that might make them seem helpless. You can teach in ways that confront this tendency.

Risks developing a negative stereotype of Angola—since the history of the prolonged Civil War could make it seem like Angola is not capable of peaceful rule. You can teach in ways that confront this tendency by not allowing them to describe Angola in negative terms and by reminding them of how the Civil War was not simply fought by Angolans: it was indicative of Cold War struggles and the legacy of Angola’s history as a colony of Portugal.

This case study could be adjusted to describe a military conflict from another region—the key is to focus on the effects to children of war, since that link is likely to draw more empathy. There are many possibilities.

- Angola’s landmines

- Landmines a deadly inheritance

- BBC: Angola’s Landmine legacy

- International Campaign to Ban Landmines

- Effects on Children of Landmines

- Utility Menu

ff79ef2fa7dffef14d5b27c4d8e7b38c

- Submit A Case

Complete List of Case Studies

Search for a case.

- Assessment (6)

- Civics (14)

- College (3)

- Curriculum (13)

- Democracy (3)

- District Leaders (7)

- Elementary School (5)

- High School (11)

- International (9)

- Middle School (5)

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Case Studies in 21st Century School Administration Addressing Challenges for Educational Leadership

- David L. Gray - University of South Alabama, USA

- Agnes E. Smith - University of South Alabama, USA

- Description

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

Provides a wealth of information about school leadership through very relevant and timely cases.

Excellent realistic portrayal of school issues

- Presents thought-provoking case studies based on actual events relating to the knowledge and skills instructional leaders must demonstrate when balancing the needs of stakeholders

- Provides a matrix in which cases are correlated to the ISLLC Standards and key issues are highlighted

- Offers a "Guide to Using Case Studies" that helps guide students in their analysis of the types of educational problems they are most likely to face

- Introduces students to specific challenges that will help them practice their decision-making, communication, resource management, and interpersonal relations skills

Sample Materials & Chapters

Case 13 - Poor Evaluations for a Teacher

Case 21 - Every Day Counts

Case 22 - Illegal Drugs at School

For instructors

Select a purchasing option.

This title is also available on SAGE Knowledge , the ultimate social sciences online library. If your library doesn’t have access, ask your librarian to start a trial .

Student Case Study

Delving into student case studies offers invaluable insights into educational methodologies and student behaviors. This guide, complete with detailed case study examples , is designed to help educators, researchers, and students understand the nuances of creating and analyzing case studies in an educational context. By exploring various case study examples, you will gain the tools and knowledge necessary to effectively interpret and apply these studies, enhancing both teaching and learning experiences in diverse academic settings.

What is a Student Case Study? – Meaning A student case study is an in-depth analysis of a student or a group of students to understand various educational, psychological, or social aspects. It involves collecting detailed information through observations, interviews, and reviewing records, to form a comprehensive picture. The goal of a case study analysis is to unravel the complexities of real-life situations that students encounter, making it a valuable tool in educational research. In a case study summary, key findings are presented, often leading to actionable insights. Educators and researchers use these studies to develop strategies for improving learning environments. Additionally, a case study essay allows students to demonstrate their understanding by discussing the analysis and implications of the case study, fostering critical thinking and analytical skills.

Download Student Case Study Bundle

Schools especially those that offers degree in medicine, law, public policy and public health teaches students to learn how to conduct a case study. Some students say they love case studies . For what reason? Case studies offer real world challenges. They help in preparing the students how to deal with their future careers. They are considered to be the vehicle for theories and concepts that enables you to be good at giving detailed discussions and even debates. Case studies are useful not just in the field of education, but also in adhering to the arising issues in business, politics and other organizations.

Student Case Study Format

Case Study Title : Clear and descriptive title reflecting the focus of the case study. Student’s Name : Name of the student the case study is about. Prepared by : Name of the person or group preparing the case study. School Name : Name of the school or educational institution. Date : Date of completion or submission.

Introduction

Background Information : Briefly describe the student’s background, including age, grade level, and relevant personal or academic history. Purpose of the Case Study : State the reason for conducting this case study, such as understanding a particular behavior, learning difficulty, or achievement.

Case Description

Situation or Challenge : Detail the specific situation, challenge, or condition that the student is facing. Observations and Evidence : Include observations from teachers, parents, or the students themselves, along with any relevant academic or behavioral records.

Problem Analysis : Analyze the situation or challenge, identifying potential causes or contributing factors. Impact on Learning : Discuss how the situation affects the student’s learning or behavior in school.

Intervention Strategies

Action Taken : Describe any interventions or strategies implemented to address the situation. This could include educational plans, counseling, or specific teaching strategies. Results of Intervention : Detail the outcome of these interventions, including any changes in the student’s behavior or academic performance.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Summary of Findings : Summarize the key insights gained from the case study. Recommendations : Offer suggestions for future actions or strategies to further support the student. This might include recommendations for teachers, parents, or the student themselves.

Best Example of Student Case Study

Overcoming Reading Challenges: A Case Study of Emily Clark, Grade 3 Prepared by: Laura Simmons, Special Education Teacher Sunset Elementary School Date: May 12, 2024 Emily Clark, an 8-year-old student in the third grade at Sunset Elementary School, has been facing significant challenges with reading and comprehension since the first grade. Known for her enthusiasm and creativity, Emily’s struggles with reading tasks have been persistent and noticeable. The primary purpose of this case study is to analyze Emily’s reading difficulties, implement targeted interventions, and assess their effectiveness. Emily exhibits difficulty in decoding words, reading fluently, and understanding text, as observed by her teachers since first grade. Her reluctance to read aloud and frustration with reading tasks have been consistently noted. Assessments indicate that her reading level is significantly below the expected standard for her grade. Parental feedback has also highlighted Emily’s struggles with reading-related homework. Analysis of Emily’s situation suggests a potential learning disability in reading, possibly dyslexia. This is evidenced by her consistent difficulty with word recognition and comprehension. These challenges have impacted not only her reading skills but also her confidence and participation in class activities, especially those involving reading. To address these challenges, an individualized education plan (IEP) was developed. This included specialized reading instruction focusing on phonemic awareness and decoding skills, multisensory learning approaches, and regular sessions with a reading specialist. Over a period of six months, Emily demonstrated significant improvements. She engaged more confidently in reading activities, and her reading assessment scores showed notable progress. In conclusion, the intervention strategies implemented for Emily have been effective. Her case highlights the importance of early identification and the implementation of tailored educational strategies for students with similar challenges. It is recommended that Emily continues to receive specialized instruction and regular monitoring. Adjustments to her IEP should be made as necessary to ensure ongoing progress. Additionally, fostering a positive reading environment at home is also recommended.

18+ Student Case Study Examples

1. student case study.

2. College Student Case Study

3. Student Case Study in the Classroom

Free Download

4. Student Case Study Format Template

- Google Docs

Size: 153 KB

5. Sample Student Case Study Example

stu.westga.edu

Size: 241 KB

6. Education Case Study Examples for Students

ceedar.education.ufl.edu

Size: 129 KB

7. Graduate Student Case Study Example

educate.bankstreet.edu

8. Student Profile Case Study Example

wholeschooling.net

Size: 51 KB

9. Short Student Case Study Example

files.eric.ed.gov

Size: 192 KB

10. High School Student Case Study Example

educationforatoz.com

Size: 135 KB

11. Student Research Case Study Example

Size: 67 KB

12. Classroom Case Study Examples

Size: 149 KB

13. Case Study of a Student

14. Sample Student Assignment Case Study Example

oise.utoronto.ca

Size: 43 KB

15. College Student Case Study Example

Size: 221 KB

16. Basic Student Case Study Example

Size: 206 KB

17. Free Student Impact Case Study Example

Size: 140 KB

18. Student Case Study in DOC Example

old.sjsu.edu

Size: 12 KB

19. Case Study Of a Student with Anxiety

Size: 178 KB

Case Study Definition

A case study is defined as a research methodology that allows you to conduct an intensive study about a particular person, group of people, community, or some unit in which the researcher could provide an in-depth data in relation to the variables. Case studies can examine a phenomena in the natural setting. This increases your ability to understand why the subjects act such. You may be able to describe how this method allows every researcher to take a specific topic to narrow it down making it into a manageable research question. The researcher gain an in-depth understanding about the subject matter through collecting qualitative research and quantitative research datasets about the phenomenon.

Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies

If a researcher is interested to study about a phenomenon, he or she will be assigned to a single-case study that will allow him or her to gain an understanding about the phenomenon. Multiple-case study would allow a researcher to understand the case as a group through comparing them based on the embedded similarities and differences. However, the volume of data in case studies will be difficult to organize and the process of analysis and strategies needs to be carefully decided upon. Reporting of findings could also be challenging at times especially when you are ought to follow for word limits.

Example of Case Study

Nurses’ pediatric pain management practices.

One of the authors of this paper (AT) has used a case study approach to explore nurses’ pediatric pain management practices. This involved collecting several datasets:

Observational data to gain a picture about actual pain management practices.

Questionnaire data about nurses’ knowledge about pediatric pain management practices and how well they felt they managed pain in children.

Questionnaire data about how critical nurses perceived pain management tasks to be.

These datasets were analyzed separately and then compared and demonstrated that nurses’ level of theoretical did not impact on the quality of their pain management practices. Nor did individual nurse’s perceptions of how critical a task was effect the likelihood of them carrying out this task in practice. There was also a difference in self-reported and observed practices; actual (observed) practices did not confirm to best practice guidelines, whereas self-reported practices tended to.

How do you Write a Case Study for Students?

1. choose an interesting and relevant topic:.

Select a topic that is relevant to your course and interesting to your audience. It should be specific and focused, allowing for in-depth analysis.

2. Conduct Thorough Research :

Gather information from reputable sources such as books, scholarly articles, interviews, and reliable websites. Ensure you have a good understanding of the topic before proceeding.

3. Identify the Problem or Research Question:

Clearly define the problem or research question your case study aims to address. Be specific about the issues you want to explore and analyze.

4. Introduce the Case:

Provide background information about the subject, including relevant historical, social, or organizational context. Explain why the case is important and what makes it unique.

5. Describe the Methods Used:

Explain the methods you used to collect data. This could include interviews, surveys, observations, or analysis of existing documents. Justify your choice of methods.

6. Present the Findings:

Present the data and findings in a clear and organized manner. Use charts, graphs, and tables if applicable. Include direct quotes from interviews or other sources to support your points.

7. Analytical Interpretation:

Analyze the data and discuss the patterns, trends, or relationships you observed. Relate your findings back to the research question. Use relevant theories or concepts to support your analysis.

8. Discuss Limitations:

Acknowledge any limitations in your study, such as constraints in data collection or research methods. Addressing limitations shows a critical awareness of your study’s scope.

9. Propose Solutions or Recommendations:

If your case study revolves around a problem, propose practical solutions or recommendations based on your analysis. Support your suggestions with evidence from your findings.

10. Write a Conclusion:

Summarize the key points of your case study. Restate the importance of the topic and your findings. Discuss the implications of your study for the broader field.

What are the objectives of a Student Case Study?

1. learning and understanding:.

- To deepen students’ understanding of a particular concept, theory, or topic within their field of study.

- To provide real-world context and practical applications for theoretical knowledge.

2. Problem-Solving Skills:

- To enhance students’ critical thinking and problem-solving abilities by analyzing complex issues or scenarios.

- To encourage students to apply their knowledge to real-life situations and develop solutions.

3. Research and Analysis:

- To develop research skills, including data collection, data analysis , and the ability to draw meaningful conclusions from information.

- To improve analytical skills in interpreting data and making evidence-based decisions.

4. Communication Skills:

- To improve written and oral communication skills by requiring students to present their findings in a clear, organized, and coherent manner.

- To enhance the ability to communicate complex ideas effectively to both academic and non-academic audiences.

5. Ethical Considerations:

To promote awareness of ethical issues related to research and decision-making, such as participant rights, privacy, and responsible conduct.

6. Interdisciplinary Learning:

To encourage cross-disciplinary or interdisciplinary thinking, allowing students to apply knowledge from multiple areas to address a problem or issue.

7. Professional Development:

- To prepare students for future careers by exposing them to real-world situations and challenges they may encounter in their chosen profession.

- To develop professional skills, such as teamwork, time management, and project management.

8. Reflection and Self-Assessment:

- To prompt students to reflect on their learning and evaluate their strengths and weaknesses in research and analysis.

- To foster self-assessment and a commitment to ongoing improvement.

9. Promoting Innovation:

- To inspire creativity and innovation in finding solutions to complex problems or challenges.

- To encourage students to think outside the box and explore new approaches.

10. Building a Portfolio:

To provide students with tangible evidence of their academic and problem-solving abilities that can be included in their academic or professional portfolios.

What are the Elements of a Case Study?

A case study typically includes an introduction, background information, presentation of the main issue or problem, analysis, solutions or interventions, and a conclusion. It often incorporates supporting data and references.

How Long is a Case Study?

The length of a case study can vary, but it generally ranges from 500 to 1500 words. This length allows for a detailed examination of the subject while maintaining conciseness and focus.

How Big Should a Case Study Be?

The size of a case study should be sufficient to comprehensively cover the topic, typically around 2 to 5 pages. This size allows for depth in analysis while remaining concise and readable.

What Makes a Good Case Study?

A good case study is clear, concise, and well-structured, focusing on a relevant and interesting issue. It should offer insightful analysis, practical solutions, and demonstrate real-world applications or implications.

Case studies bring people into the real world to allow themselves engage in different fields such as in business examples, politics, health related aspect where each individuals could find an avenue to make difficult decisions. It serves to provide framework for analysis and evaluation of the different societal issues. This is one of the best way to focus on what really matters, to discuss about issues and to know what can we do about it.

AI Generator

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Education Case Study Examples for Students

Graduate Student Case Study Example

Student Profile Case Study Example

High School Student Case Study Example

Student Research Case Study Example

Top 40 Most Popular Case Studies of 2021

Two cases about Hertz claimed top spots in 2021's Top 40 Most Popular Case Studies

Two cases on the uses of debt and equity at Hertz claimed top spots in the CRDT’s (Case Research and Development Team) 2021 top 40 review of cases.

Hertz (A) took the top spot. The case details the financial structure of the rental car company through the end of 2019. Hertz (B), which ranked third in CRDT’s list, describes the company’s struggles during the early part of the COVID pandemic and its eventual need to enter Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

The success of the Hertz cases was unprecedented for the top 40 list. Usually, cases take a number of years to gain popularity, but the Hertz cases claimed top spots in their first year of release. Hertz (A) also became the first ‘cooked’ case to top the annual review, as all of the other winners had been web-based ‘raw’ cases.

Besides introducing students to the complicated financing required to maintain an enormous fleet of cars, the Hertz cases also expanded the diversity of case protagonists. Kathyrn Marinello was the CEO of Hertz during this period and the CFO, Jamere Jackson is black.

Sandwiched between the two Hertz cases, Coffee 2016, a perennial best seller, finished second. “Glory, Glory, Man United!” a case about an English football team’s IPO made a surprise move to number four. Cases on search fund boards, the future of malls, Norway’s Sovereign Wealth fund, Prodigy Finance, the Mayo Clinic, and Cadbury rounded out the top ten.

Other year-end data for 2021 showed:

- Online “raw” case usage remained steady as compared to 2020 with over 35K users from 170 countries and all 50 U.S. states interacting with 196 cases.

- Fifty four percent of raw case users came from outside the U.S..

- The Yale School of Management (SOM) case study directory pages received over 160K page views from 177 countries with approximately a third originating in India followed by the U.S. and the Philippines.

- Twenty-six of the cases in the list are raw cases.

- A third of the cases feature a woman protagonist.

- Orders for Yale SOM case studies increased by almost 50% compared to 2020.

- The top 40 cases were supervised by 19 different Yale SOM faculty members, several supervising multiple cases.

CRDT compiled the Top 40 list by combining data from its case store, Google Analytics, and other measures of interest and adoption.

All of this year’s Top 40 cases are available for purchase from the Yale Management Media store .

And the Top 40 cases studies of 2021 are:

1. Hertz Global Holdings (A): Uses of Debt and Equity

2. Coffee 2016

3. Hertz Global Holdings (B): Uses of Debt and Equity 2020

4. Glory, Glory Man United!

5. Search Fund Company Boards: How CEOs Can Build Boards to Help Them Thrive

6. The Future of Malls: Was Decline Inevitable?

7. Strategy for Norway's Pension Fund Global

8. Prodigy Finance

9. Design at Mayo

10. Cadbury

11. City Hospital Emergency Room

13. Volkswagen

14. Marina Bay Sands

15. Shake Shack IPO

16. Mastercard

17. Netflix

18. Ant Financial

19. AXA: Creating the New CR Metrics

20. IBM Corporate Service Corps

21. Business Leadership in South Africa's 1994 Reforms

22. Alternative Meat Industry

23. Children's Premier

24. Khalil Tawil and Umi (A)

25. Palm Oil 2016

26. Teach For All: Designing a Global Network

27. What's Next? Search Fund Entrepreneurs Reflect on Life After Exit

28. Searching for a Search Fund Structure: A Student Takes a Tour of Various Options

30. Project Sammaan

31. Commonfund ESG

32. Polaroid

33. Connecticut Green Bank 2018: After the Raid

34. FieldFresh Foods

35. The Alibaba Group

36. 360 State Street: Real Options

37. Herman Miller

38. AgBiome

39. Nathan Cummings Foundation

40. Toyota 2010

Case Study: Mergen V. Westside Community School

This essay about the case of Mergens v. Westside Community Schools explores the legal battle surrounding students’ rights to form religious clubs in public schools. It follows the story of Bridget Mergens, a high school student who challenged school policies restricting her from establishing a Christian club. Ultimately, the Supreme Court ruled in Mergens’ favor, affirming students’ rights to express their religious beliefs on school grounds. The case sparked nationwide discussions on the intersection of religious freedom and public education, leaving a lasting impact on school policies and practices across the country.

How it works

The legal saga of Mergens v. Westside Community Schools unveils a riveting narrative at the crossroads of religious liberties and public education. Bridget Mergens, a spirited high school student from Nebraska, ignited a firestorm when she sought to establish a Christian club at her school. Yet, her aspirations were met with resistance from school officials citing concerns about constitutional boundaries.

The case catapulted into the legal arena, with Mergens and her family steadfast in their pursuit of justice. Their battle cry echoed through the halls of the Supreme Court, where in 1990, the justices delivered a resounding verdict in favor of Mergens.

In a momentous 8-1 decision, the Court affirmed the rights of students to form religious clubs on public school grounds, citing the protections enshrined in the Equal Access Act of 1984.

Justice Anthony Kennedy’s eloquent prose, resonating with the echoes of constitutional principles, underscored the significance of Mergens’ victory. His words echoed through the annals of legal history, reaffirming the fundamental tenets of free speech and freedom of religion in the public sphere. The ruling became a beacon of hope for students nationwide, empowering them to embrace their religious identities without fear of discrimination or censorship.

The ripple effects of Mergens’ triumph reverberated across the educational landscape, prompting schools to reevaluate their policies and practices. In the wake of the decision, a wave of inclusivity swept through school corridors, as administrators endeavored to create environments that honored the diversity of religious beliefs among their student body.

Yet, beyond the legal minutiae, Mergens v. Westside Community Schools stands as a testament to the indomitable spirit of a young woman who dared to challenge the status quo. Bridget Mergens’ courage and determination serve as a reminder that even the smallest voice can spark seismic change and shape the trajectory of history.

In conclusion, Mergens v. Westside Community Schools is more than just a legal precedent—it is a testament to the enduring struggle for religious freedom in the public sphere. Through Mergens’ unwavering resolve and the Supreme Court’s landmark decision, students across America have been empowered to embrace their religious identities and express their beliefs without fear of reprisal. As we reflect on this pivotal moment in our nation’s history, we are reminded of the enduring power of individuals to champion their rights and reshape the fabric of society

Cite this page

Case Study: Mergen V. Westside Community School. (2024, Apr 29). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/case-study-mergen-v-westside-community-school/

"Case Study: Mergen V. Westside Community School." PapersOwl.com , 29 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/case-study-mergen-v-westside-community-school/