Cohort Studies: Design, Analysis, and Reporting

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH.

- PMID: 32658655

- DOI: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.014

Cohort studies are types of observational studies in which a cohort, or a group of individuals sharing some characteristic, are followed up over time, and outcomes are measured at one or more time points. Cohort studies can be classified as prospective or retrospective studies, and they have several advantages and disadvantages. This article reviews the essential characteristics of cohort studies and includes recommendations on the design, statistical analysis, and reporting of cohort studies in respiratory and critical care medicine. Tools are provided for researchers and reviewers.

Keywords: bias; cohort studies; confounding; prospective; retrospective.

Copyright © 2020 American College of Chest Physicians. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Cohort Studies*

- Data Interpretation, Statistical

- Guidelines as Topic

- Research Design / statistics & numerical data*

Prospective Cohort Study Design: Definition & Examples

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

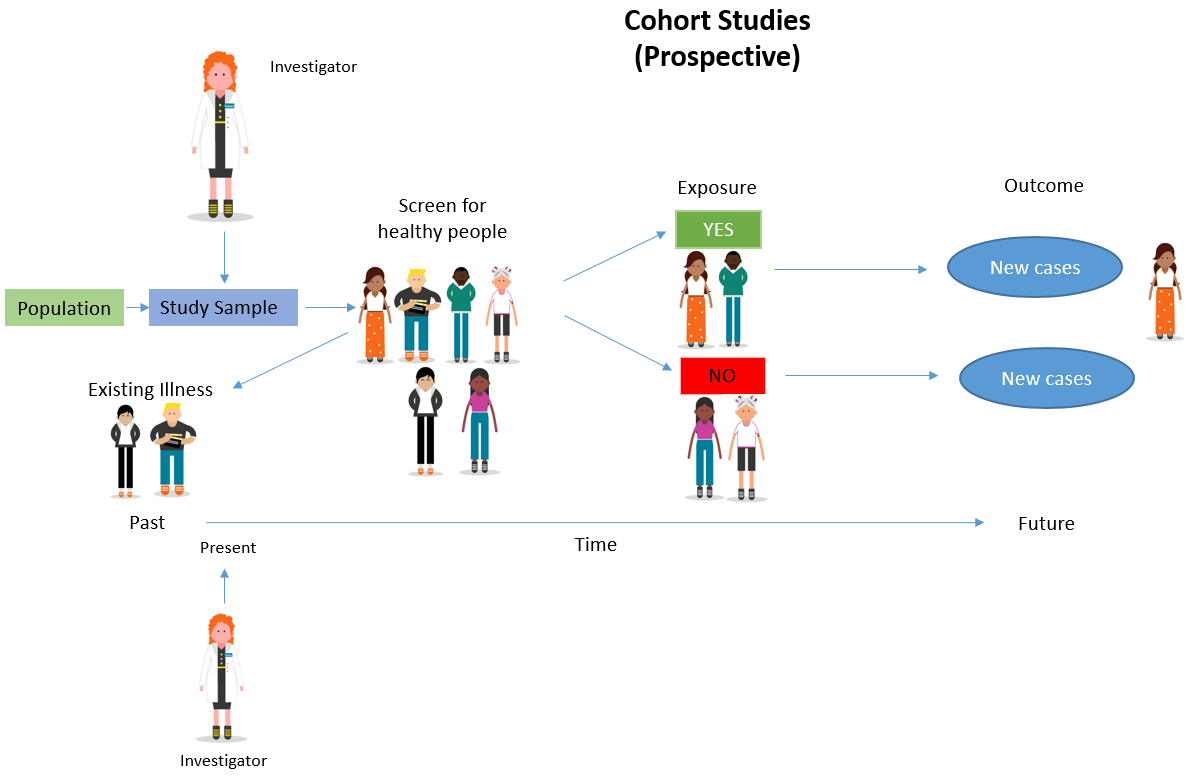

A prospective study, sometimes called a prospective cohort study, is a type of longitudinal study where researchers will follow and observe a group of subjects over a period of time to gather information and record the development of outcomes.

The participants in a prospective study are selected based on specific criteria and are often free from the outcome of interest at the beginning of the study. Data on exposures and potential confounding factors are collected at regular intervals throughout the study period.

By following the participants prospectively, researchers can establish a temporal relationship between exposures and outcomes, providing valuable insights into the causality of the observed associations.

This study design allows for the examination of multiple outcomes and the investigation of various exposure levels, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing health and disease.

How it Works

Participants are enrolled in the study before they develop the outcome or disease in question and then are observed as it evolves to see who develops the outcome and who does not.

Cohort studies are observational, so researchers will follow the subjects without manipulating any variables or interfering with their environment.

Similar to retrospective studies , prospective studies are beneficial for medical researchers, specifically in the field of epidemiology, as scientists can watch the development of a disease and compare the risk factors among subjects.

Before any appearance of the disease is investigated, medical professionals will identify a cohort, observe the target participants over time, and collect data at regular intervals.

Weeks, months, or years later, depending on the duration of the study design, the researchers will examine any factors that differed between the individuals who developed the condition and those who did not.

They can then determine if an association exists between an exposure and an outcome and even identify disease progression and relative risk.

Determine cause-and-effect relationships

Because researchers study groups of people before they develop an illness, they can discover potential cause-and-effect relationships between certain behaviors and the development of a disease.

Multiple diseases and conditions can be studied at the same time

Prospective cohort studies enable researchers to study causes of disease and identify multiple risk factors associated with a single exposure. These studies can also reveal links between diseases and risk factors.

Can measure a continuously changing relationship between exposure and outcome

Because prospective cohort studies are longitudinal, researchers can study changes in levels of exposure over time and any changes in outcome, providing a deeper understanding of the dynamic relationship between exposure and outcome.

Limitations

Time consuming and expensive.

Prospective studies usually require multiple months or years before researchers can identify a disease’s causes or discover significant results.

Because of this, they are often more expensive than other types of studies. Recruiting and enrolling participants is another added cost and time commitment.

Requires large subject pool

Prospective cohort studies require large sample sizes in order for any relationships or patterns to be meaningful. Researchers are unable to generate results if there is not enough data.

- Framingham Heart Study: Studied the effects of diet, exercise, and medications on the development of hypertensive or arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease in residents of the city of Framingham, Massachusetts.

- Caerphilly Heart Disease Study: Examined relationships between a wide range of social, lifestyle, dietary, and other factors with incident vascular disease.

- The Million Women Study: Analyzed data from more than one million women aged 50 and over to understand the effects of hormone replacement therapy use on women’s health.

- Nurses’ Health Study: Studied the effects of diet, exercise, and medications on the development of hypertensive or arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

- Sleep-Disordered Breathing and Mortality: Determined whether sleep-disordered breathing and its sequelae of intermittent hypoxemia and recurrent arousals are associated with mortality in a community sample of adults aged 40 years or older (Punjabi et al., 2009)

Frequently Asked Questions

1. what does it mean when an observational study is prospective.

A prospective observational study is a type of research where investigators select a group of subjects and observe them over a certain period.

The researchers collect data on the subjects’ exposure to certain risk factors or interventions and then track the outcomes. This type of study is often used to study the effects of suspected risk factors that cannot be controlled experimentally.

2. What is the primary difference between a randomized clinical trial and a prospective cohort study?

In a retrospective study, the subjects have already experienced the outcome of interest or developed the disease before the start of the study.

The researchers then look back in time to identify a cohort of subjects before they had developed the disease and use existing data, such as medical records, to discover any patterns.

In a prospective study, on the other hand, the investigators will design the study, recruit subjects, and collect baseline data on all subjects before any of them have developed the outcomes of interest.

The subjects are followed and observed over a period of time to gather information and record the development of outcomes.

3. What is the primary difference between a randomized clinical trial and a prospective cohort study?

In randomized clinical trials , the researchers control the experiment, whereas prospective cohort studies are purely observational, so researchers will observe subjects without manipulating any variables or interfering with their environment.

Researchers in randomized clinical trials will randomly divide participants into groups, either an experimental group or a control group.

However, in prospective cohort studies, researchers will identify a cohort and observe the target participants as a whole to examine any factors that differ between the individuals who develop the condition and those who do not.

Euser, A. M., Zoccali, C., Jager, K. J., & Dekker, F. W. (2009). Cohort studies: prospective versus retrospective. Nephron. Clinical practice, 113(3), c214–c217. https://doi.org/10.1159/000235241

Hariton, E., & Locascio, J. J. (2018). Randomised controlled trials – the gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: randomised controlled trials. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology, 125(13), 1716. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15199

Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis-2 Study Group de Mutsert Renée r. de_mutsert@ lumc. nl Grootendorst Diana C Boeschoten Elisabeth W Brandts Hans van Manen Jeannette G Krediet Raymond T Dekker Friedo W. (2009). Subjective global assessment of nutritional status is strongly associated with mortality in chronic dialysis patients. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 89(3), 787-793.

Punjabi, N. M., Caffo, B. S., Goodwin, J. L., Gottlieb, D. J., Newman, A. B., O”Connor, G. T., Rapoport, D. M., Redline, S., Resnick, H. E., Robbins, J. A., Shahar, E., Unruh, M. L., & Samet, J. M. (2009). Sleep-disordered breathing and mortality: a prospective cohort study. PLoS medicine, 6(8), e1000132. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000132

Ranganathan, P., & Aggarwal, R. (2018). Study designs: Part 1 – An overview and classification. Perspectives in clinical research, 9(4), 184–186.

Song, J. W., & Chung, K. C. (2010). Observational studies: cohort and case-control studies. Plastic and reconstructive surgery, 126(6), 2234–2242. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f44abc.

Further Information

- Euser, A. M., Zoccali, C., Jager, K. J., & Dekker, F. W. (2009). Cohort studies: prospective versus retrospective. Nephron Clinical Practice, 113(3), c214-c217.

- Design of Prospective Studies

- Hammoudeh, S., Gadelhaq, W., & Janahi, I. (2018). Prospective cohort studies in medical research (pp. 11-28). IntechOpen.

- Nabi, H., Kivimaki, M., De Vogli, R., Marmot, M. G., & Singh-Manoux, A. (2008). Positive and negative affect and risk of coronary heart disease: Whitehall II prospective cohort study. Bmj, 337.

- Bramsen, I., Dirkzwager, A. J., & Van der Ploeg, H. M. (2000). Predeployment personality traits and exposure to trauma as predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms: A prospective study of former peacekeepers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(7), 1115-1119.

Quantitative study designs: Cohort Studies

Quantitative study designs.

- Introduction

- Cohort Studies

- Randomised Controlled Trial

- Case Control

- Cross-Sectional Studies

- Study Designs Home

Cohort Study

Did you know that the majority of people will develop a diagnosable mental illness whilst only a minority will experience enduring mental health? Or that groups of people at risk of having high blood pressure and other related health issues by the age of 38 can be identified in childhood? Or that a poor credit rating can be indicative of a person’s health status?

These findings (and more) have come out of a large cohort study started in 1972 by researchers at the University of Otago in New Zealand. This study is known as The Dunedin Study and it has followed the lives of 1037 babies born between 1 April 1972 and 31 March 1973 since their birth. The study is now in its fifth decade and has produced over 1200 publications and reports, many of which have helped inform policy makers in New Zealand and overseas.

In Introduction to Study Designs, we learnt that there are many different study design types and that these are divided into two categories: Experimental and Observational. Cohort Studies are a type of observational study.

What is a Cohort Study design?

- Cohort studies are longitudinal, observational studies, which investigate predictive risk factors and health outcomes.

- They differ from clinical trials, in that no intervention, treatment, or exposure is administered to the participants. The factors of interest to researchers already exist in the study group under investigation.

- Study participants are observed over a period of time. The incidence of disease in the exposed group is compared with the incidence of disease in the unexposed group.

- Because of the observational nature of cohort studies they can only find correlation between a risk factor and disease rather than the cause.

Cohort studies are useful if:

- There is a persuasive hypothesis linking an exposure to an outcome.

- The time between exposure and outcome is not too long (adding to the study costs and increasing the risk of participant attrition).

- The outcome is not too rare.

The stages of a Cohort Study

- A cohort study starts with the selection of a group of participants (known as a ‘cohort’) sourced from the same population, who must be free of the outcome under investigation but have the potential to develop that outcome.

- The participants must be identical, having common characteristics except for their exposure status.

- The participants are divided into two groups – the first group is the ‘exposure’ group, the second group is free of the exposure.

Types of Cohort Studies

There are two types of cohort studies: Prospective and Retrospective .

How Cohort Studies are carried out

Adapted from: Cohort Studies: A brief overview by Terry Shaneyfelt [video] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FRasHsoORj0)

Which clinical questions does this study design best answer?

What are the advantages and disadvantages to consider when using a cohort study, what does a strong cohort study look like.

- The aim of the study is clearly stated.

- It is clear how the sample population was sourced, including inclusion and exclusion criteria, with justification provided for the sample size. The sample group accurately reflects the population from which it is drawn.

- Loss of participants to follow up are stated and explanations provided.

- The control group is clearly described, including the selection methodology, whether they were from the same sample population, whether randomised or matched to minimise bias and confounding.

- It is clearly stated whether the study was blinded or not, i.e. whether the investigators were aware of how the subject and control groups were allocated.

- The methodology was rigorously adhered to.

- Involves the use of valid measurements (recognised by peers) as well as appropriate statistical tests.

- The conclusions are logically drawn from the results – the study demonstrates what it says it has demonstrated.

- Includes a clear description of the data, including accessibility and availability.

What are the pitfalls to look for?

- Confounding factors within the sample groups may be difficult to identify and control for, thus influencing the results.

- Participants may move between exposure/non-exposure categories or not properly comply with methodology requirements.

- Being in the study may influence participants’ behaviour.

- Too many participants may drop out, thus rendering the results invalid.

Critical appraisal tools

To assist with the critical appraisal of a cohort study here are some useful tools that can be applied.

Critical appraisal checklist for cohort studies (JBI)

CASP appraisal checklist for cohort studies

Real World Examples

Bell, A.F., Rubin, L.H., Davis, J.M., Golding, J., Adejumo, O.A. & Carter, C.S. (2018). The birth experience and subsequent maternal caregiving attitudes and behavior: A birth cohort study . Archives of Women’s Mental Health .

Dykxhoorn, J., Hatcher, S., Roy-Gagnon, M.H., & Colman, I. (2017). Early life predictors of adolescent suicidal thoughts and adverse outcomes in two population-based cohort studies . PLoS ONE , 12(8).

Feeley, N., Hayton, B., Gold, I. & Zelkowitz, P. (2017). A comparative prospective cohort study of women following childbirth: Mothers of low birthweight infants at risk for elevated PTSD symptoms . Journal of Psychosomatic Research , 101, 24–30.

Forman, J.P., Stampfer, M.J. & Curhan, G.C. (2009). Diet and lifestyle risk factors associated with incident hypertension in women . JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association , 302(4), 401–411.

Suarez, E. (2002). Prognosis and outcome of first-episode psychoses in Hawai’i: Results of the 15-year follow-up of the Honolulu cohort of the WHO international study of schizophrenia . ProQuest Information & Learning, Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering , 63(3-B), 1577.

Young, J.T., Heffernan, E., Borschmann, R., Ogloff, J.R.P., Spittal, M.J., Kouyoumdjian, F.G., Preen, D.B., Butler, A., Brophy, L., Crilly, J. & Kinner, S.A. (2018). Dual diagnosis of mental illness and substance use disorder and injury in adults recently released from prison: a prospective cohort study . The Lancet. Public Health , 3(5), e237–e248.

References and Further Reading

Greenhalgh, T. (2014). How to Read a Paper : The Basics of Evidence-Based Medicine , John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, Somerset, United Kingdom.

Hoffmann, T. a., Bennett, S. P., & Mar, C. D. (2017). Evidence-Based Practice Across the Health Professions (Third edition. ed.): Elsevier.

Song, J.W. & Chung, K.C. (2010). Observational studies: cohort and case-control studies . Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery , 126(6), 2234-42.

Mann, C.J. (2003). Observational research methods. Research design II: cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies . Emergency Medicine Journal , 20(1), 54-60.

- << Previous: Introduction

- Next: Randomised Controlled Trial >>

- Last Updated: Feb 29, 2024 4:49 PM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/quantitative-study-designs

Study Design 101: Cohort Study

- Case Report

- Case Control Study

- Cohort Study

- Randomized Controlled Trial

- Practice Guideline

- Systematic Review

- Meta-Analysis

- Helpful Formulas

- Finding Specific Study Types

A study design where one or more samples (called cohorts) are followed prospectively and subsequent status evaluations with respect to a disease or outcome are conducted to determine which initial participants exposure characteristics (risk factors) are associated with it. As the study is conducted, outcome from participants in each cohort is measured and relationships with specific characteristics determined

- Subjects in cohorts can be matched, which limits the influence of confounding variables

- Standardization of criteria/outcome is possible

- Easier and cheaper than a randomized controlled trial (RCT)

Disadvantages

- Cohorts can be difficult to identify due to confounding variables

- No randomization, which means that imbalances in patient characteristics could exist

- Blinding/masking is difficult

- Outcome of interest could take time to occur

Design pitfalls to look out for

The cohorts need to be chosen from separate, but similar, populations.

How many differences are there between the control cohort and the experiment cohort? Will those differences cloud the study outcomes?

Fictitious Example

A cohort study was designed to assess the impact of sun exposure on skin damage in beach volleyball players. During a weekend tournament, players from one team wore waterproof, SPF 35 sunscreen, while players from the other team did not wear any sunscreen. At the end of the volleyball tournament players' skin from both teams was analyzed for texture, sun damage, and burns. Comparisons of skin damage were then made based on the use of sunscreen. The analysis showed a significant difference between the cohorts in terms of the skin damage.

Real-life Examples

Hoepner, L., Whyatt, R., Widen, E., Hassoun, A., Oberfield, S., Mueller, N., ... Rundle, A. (2016). Bisphenol A and Adiposity in an Inner-City Birth Cohort. Environmental Health Perspectives, 124 (10), 1644-1650. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP205

This longitudinal cohort study looked at whether exposure to bisphenol A (BPA) early in life affects obesity levels in children later in life. Positive associations were found between prenatal BPA concentrations in urine and increased fat mass index, percent body fat, and waist circumference at age seven.

Lao, X., Liu, X., Deng, H., Chan, T., Ho, K., Wang, F., ... Yeoh, E. (2018). Sleep Quality, Sleep Duration, and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study With 60,586 Adults. Journal Of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 14 (1), 109-117. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.6894

This prospective cohort study explored "the joint effects of sleep quality and sleep duration on the development of coronary heart disease." The study included 60,586 participants and an association was shown between increased risk of coronary heart disease and individuals who experienced short sleep duration and poor sleep quality. Long sleep duration did not demonstrate a significant association.

Related Formulas

- Relative Risk

Related Terms

A group that shares the same characteristics among its members (population).

Confounding Variables

Variables that cause/prevent an outcome from occurring outside of or along with the variable being studied. These variables render it difficult or impossible to distinguish the relationship between the variable and outcome being studied).

Population Bias/Volunteer Bias

A sample may be skewed by those who are selected or self-selected into a study. If only certain portions of a population are considered in the selection process, the results of a study may have poor validity.

Prospective Study

A study that moves forward in time, or that the outcomes are being observed as they occur, as opposed to a retrospective study, which looks back on outcomes that have already taken place.

Now test yourself!

1. In a cohort study, an exposure is assessed and then participants are followed prospectively to observe whether they develop the outcome.

a) True b) False

2. Cohort Studies generally look at which of the following?

a) Determining the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic methods b) Identifying patient characteristics or risk factors associated with a disease or outcome c) Variations among the clinical manifestations of patients with a disease d) The impact of blinding or masking a study population

Evidence Pyramid - Navigation

- Meta- Analysis

- Case Reports

- << Previous: Case Control Study

- Next: Randomized Controlled Trial >>

- Last Updated: Sep 25, 2023 10:59 AM

- URL: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/studydesign101

- Himmelfarb Intranet

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

- 2300 Eye St., NW, Washington, DC 20037

- Phone: (202) 994-2850

- [email protected]

- https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu

Widespread recessive effects on common diseases in a cohort of 44,000 British Pakistanis and Bangladeshis with high autozygosity

- Find this author on Google Scholar

- Find this author on PubMed

- Search for this author on this site

- ORCID record for Teng Hiang Heng

- For correspondence: [email protected] [email protected]

- ORCID record for Mark J Daly

- ORCID record for Henrike Heyne

- ORCID record for David A. van Heel

- Info/History

- Supplementary material

- Preview PDF

Genetic association studies have focused on testing additive models in cohorts with European ancestry. Little is known about recessive effects on common diseases, specifically for non-European ancestry. Genes & Health is a cohort of British Pakistani and Bangladeshi individuals with elevated rates of consanguinity and endogamy, making it suitable to study recessive effects. We imputed variants into 44,190 genotyped individuals, using two imputation panels: a set of 4,982 whole-exome-sequences from within the cohort, and the TOPMed-r2 panel. We performed association testing with 898 diseases from electronic health records. We identified 185 independent loci that reached standard genome-wide significance (p<5×10 −8 ) under the recessive model and had p-values more significant than under the additive model. 140 loci demonstrated nominally-significant (p<0.05) dominance deviation p-values, confirming a recessive association pattern. Sixteen loci in three clusters were significant at a Bonferroni threshold accounting for multiple phenotypes tested (p<5.5×10 −12 ). In FinnGen, we replicated 44% of the expected number of Bonferroni-significant loci we were powered to replicate, at least one from each cluster, including an intronic variant in PNPLA3 (rs66812091) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, a previously reported additive association. We present novel evidence suggesting that the association is recessive instead (OR=1.3, recessive p=2×10 −12 , additive p=2×10 −11 , dominance deviation p=3×10 −2 , FinnGen recessive OR=1.3 and p=6×10 −12 ). We identified a novel protective recessive association between a missense variant in SGLT4 (rs61746559), a sodium-glucose transporter with a possible role in the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, and hypertension (OR=0.2, p=3×10 −8 , dominance deviation p=7×10 −6 ). These results motivate interrogating recessive effects on common diseases more widely.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

Competing Interest Statement

The authors have declared no competing interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded in part by Wellcome (grant no. 220540/Z/20/A, Wellcome Sanger Institute Quinquennial Review 2021–2026). For the purpose of open access, the authors have applied a CC–BY public copyright licence to any author accepted manuscript version arising from this submission. Genes & Health is/has recently been core–funded by Wellcome (WT102627, WT210561), the Medical Research Council (UK) (M009017, MR/X009777/1, MR/X009920/1), Higher Education Funding Council for England Catalyst, Barts Charity (845/1796), Health Data Research UK (for London substantive site), and research delivery support from the NHS National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network (North Thames). Genes & Health is/has recently been funded by Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Genomics PLC; and a Life Sciences Industry Consortium of Astra Zeneca PLC, Bristol–Myers Squibb Company, GlaxoSmithKline Research and Development Limited, Maze Therapeutics Inc, Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, Novo Nordisk A/S, Pfizer Inc, Takeda Development Centre Americas Inc. T. H. Heng is supported by the Agency for Science, Technology, and Research (A∗STAR) National Science Scholarship. The FinnGen project is funded by two grants from Business Finland (HUS 4685/31/2016 and UH 4386/31/2016) and the following industry partners: AbbVie Inc., AstraZeneca UK Ltd, Biogen MA Inc., Bristol Myers Squibb (and Celgene Corporation & Celgene International II Sarl), Genentech Inc., Merck Sharp & Dohme LCC, Pfizer Inc., GlaxoSmithKline Intellectual Property Development Ltd., Sanofi US Services Inc., Maze Therapeutics Inc., Janssen Biotech Inc, Novartis Pharma AG, and Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH.

Author Declarations

I confirm all relevant ethical guidelines have been followed, and any necessary IRB and/or ethics committee approvals have been obtained.

The details of the IRB/oversight body that provided approval or exemption for the research described are given below:

The London South East NRES Committee of the Health Research Authority gave ethical approval for the G&H work (14/LO/1240, dated 16 September 2014). The Coordinating Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa (HUS) gave ethical approval for the FinnGen work (Nr HUS/990/2017).

I confirm that all necessary patient/participant consent has been obtained and the appropriate institutional forms have been archived, and that any patient/participant/sample identifiers included were not known to anyone (e.g., hospital staff, patients or participants themselves) outside the research group so cannot be used to identify individuals.

I understand that all clinical trials and any other prospective interventional studies must be registered with an ICMJE-approved registry, such as ClinicalTrials.gov. I confirm that any such study reported in the manuscript has been registered and the trial registration ID is provided (note: if posting a prospective study registered retrospectively, please provide a statement in the trial ID field explaining why the study was not registered in advance).

I have followed all appropriate research reporting guidelines, such as any relevant EQUATOR Network research reporting checklist(s) and other pertinent material, if applicable.

Data and code availability

G&H data is available for analysis in a secure Trusted Research Environment. Application can be made to the G&H executive: https://www.genesandhealth.org/research/scientists-using-genes-health-scientific-research

Information on how to access FinnGen data can be found here: https://www.finngen.fi/en/access_results

Software used in the data analysis are publicly available and have been cited. Code written to run these algorithms is available upon reasonable request to the authors.

View the discussion thread.

Supplementary Material

Thank you for your interest in spreading the word about medRxiv.

NOTE: Your email address is requested solely to identify you as the sender of this article.

Citation Manager Formats

- EndNote (tagged)

- EndNote 8 (xml)

- RefWorks Tagged

- Ref Manager

- Tweet Widget

- Facebook Like

- Google Plus One

Subject Area

- Genetic and Genomic Medicine

- Addiction Medicine (316)

- Allergy and Immunology (619)

- Anesthesia (160)

- Cardiovascular Medicine (2277)

- Dentistry and Oral Medicine (279)

- Dermatology (201)

- Emergency Medicine (370)

- Endocrinology (including Diabetes Mellitus and Metabolic Disease) (802)

- Epidemiology (11582)

- Forensic Medicine (10)

- Gastroenterology (679)

- Genetic and Genomic Medicine (3590)

- Geriatric Medicine (337)

- Health Economics (618)

- Health Informatics (2308)

- Health Policy (914)

- Health Systems and Quality Improvement (864)

- Hematology (335)

- HIV/AIDS (753)

- Infectious Diseases (except HIV/AIDS) (13162)

- Intensive Care and Critical Care Medicine (757)

- Medical Education (359)

- Medical Ethics (100)

- Nephrology (389)

- Neurology (3354)

- Nursing (191)

- Nutrition (507)

- Obstetrics and Gynecology (651)

- Occupational and Environmental Health (647)

- Oncology (1759)

- Ophthalmology (525)

- Orthopedics (209)

- Otolaryngology (284)

- Pain Medicine (223)

- Palliative Medicine (66)

- Pathology (439)

- Pediatrics (1007)

- Pharmacology and Therapeutics (422)

- Primary Care Research (406)

- Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology (3065)

- Public and Global Health (5996)

- Radiology and Imaging (1224)

- Rehabilitation Medicine and Physical Therapy (715)

- Respiratory Medicine (811)

- Rheumatology (367)

- Sexual and Reproductive Health (353)

- Sports Medicine (316)

- Surgery (388)

- Toxicology (50)

- Transplantation (171)

- Urology (142)

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples

What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples

Published on June 7, 2021 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023 by Pritha Bhandari.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall research objectives and approach

- Whether you’ll rely on primary research or secondary research

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research objectives and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research design.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities—start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed-methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types.

- Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships

- Descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analyzing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study—plants, animals, organizations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

- Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalize your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study , your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalize to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question .

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviors, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews .

Observation methods

Observational studies allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviors or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what kinds of data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected—for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are high in reliability and validity.

Operationalization

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalization means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in—for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced, while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method , you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample—by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method , it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method , how will you avoid research bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organizing and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymize and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well-organized will save time when it comes to analyzing it. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings (high replicability ).

On its own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyze the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarize your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarize your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analyzing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question . It defines your overall approach and determines how you will collect and analyze data.

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims, that you collect high-quality data, and that you use the right kind of analysis to answer your questions, utilizing credible sources . This allows you to draw valid , trustworthy conclusions.

Quantitative research designs can be divided into two main categories:

- Correlational and descriptive designs are used to investigate characteristics, averages, trends, and associations between variables.

- Experimental and quasi-experimental designs are used to test causal relationships .

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible. Common types of qualitative design include case study , ethnography , and grounded theory designs.

The priorities of a research design can vary depending on the field, but you usually have to specify:

- Your research questions and/or hypotheses

- Your overall approach (e.g., qualitative or quantitative )

- The type of design you’re using (e.g., a survey , experiment , or case study )

- Your data collection methods (e.g., questionnaires , observations)

- Your data collection procedures (e.g., operationalization , timing and data management)

- Your data analysis methods (e.g., statistical tests or thematic analysis )

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population . Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research. For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

In statistics, sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population.

Operationalization means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioral avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalize the variables that you want to measure.

A research project is an academic, scientific, or professional undertaking to answer a research question . Research projects can take many forms, such as qualitative or quantitative , descriptive , longitudinal , experimental , or correlational . What kind of research approach you choose will depend on your topic.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 8, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, guide to experimental design | overview, steps, & examples, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, ethical considerations in research | types & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Perspect Clin Res

- v.9(4); Oct-Dec 2018

Study designs: Part 1 – An overview and classification

Priya ranganathan.

Department of Anaesthesiology, Tata Memorial Centre, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Rakesh Aggarwal

1 Department of Gastroenterology, Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India

There are several types of research study designs, each with its inherent strengths and flaws. The study design used to answer a particular research question depends on the nature of the question and the availability of resources. In this article, which is the first part of a series on “study designs,” we provide an overview of research study designs and their classification. The subsequent articles will focus on individual designs.

INTRODUCTION

Research study design is a framework, or the set of methods and procedures used to collect and analyze data on variables specified in a particular research problem.

Research study designs are of many types, each with its advantages and limitations. The type of study design used to answer a particular research question is determined by the nature of question, the goal of research, and the availability of resources. Since the design of a study can affect the validity of its results, it is important to understand the different types of study designs and their strengths and limitations.

There are some terms that are used frequently while classifying study designs which are described in the following sections.

A variable represents a measurable attribute that varies across study units, for example, individual participants in a study, or at times even when measured in an individual person over time. Some examples of variables include age, sex, weight, height, health status, alive/dead, diseased/healthy, annual income, smoking yes/no, and treated/untreated.

Exposure (or intervention) and outcome variables

A large proportion of research studies assess the relationship between two variables. Here, the question is whether one variable is associated with or responsible for change in the value of the other variable. Exposure (or intervention) refers to the risk factor whose effect is being studied. It is also referred to as the independent or the predictor variable. The outcome (or predicted or dependent) variable develops as a consequence of the exposure (or intervention). Typically, the term “exposure” is used when the “causative” variable is naturally determined (as in observational studies – examples include age, sex, smoking, and educational status), and the term “intervention” is preferred where the researcher assigns some or all participants to receive a particular treatment for the purpose of the study (experimental studies – e.g., administration of a drug). If a drug had been started in some individuals but not in the others, before the study started, this counts as exposure, and not as intervention – since the drug was not started specifically for the study.

Observational versus interventional (or experimental) studies

Observational studies are those where the researcher is documenting a naturally occurring relationship between the exposure and the outcome that he/she is studying. The researcher does not do any active intervention in any individual, and the exposure has already been decided naturally or by some other factor. For example, looking at the incidence of lung cancer in smokers versus nonsmokers, or comparing the antenatal dietary habits of mothers with normal and low-birth babies. In these studies, the investigator did not play any role in determining the smoking or dietary habit in individuals.

For an exposure to determine the outcome, it must precede the latter. Any variable that occurs simultaneously with or following the outcome cannot be causative, and hence is not considered as an “exposure.”

Observational studies can be either descriptive (nonanalytical) or analytical (inferential) – this is discussed later in this article.

Interventional studies are experiments where the researcher actively performs an intervention in some or all members of a group of participants. This intervention could take many forms – for example, administration of a drug or vaccine, performance of a diagnostic or therapeutic procedure, and introduction of an educational tool. For example, a study could randomly assign persons to receive aspirin or placebo for a specific duration and assess the effect on the risk of developing cerebrovascular events.

Descriptive versus analytical studies

Descriptive (or nonanalytical) studies, as the name suggests, merely try to describe the data on one or more characteristics of a group of individuals. These do not try to answer questions or establish relationships between variables. Examples of descriptive studies include case reports, case series, and cross-sectional surveys (please note that cross-sectional surveys may be analytical studies as well – this will be discussed in the next article in this series). Examples of descriptive studies include a survey of dietary habits among pregnant women or a case series of patients with an unusual reaction to a drug.

Analytical studies attempt to test a hypothesis and establish causal relationships between variables. In these studies, the researcher assesses the effect of an exposure (or intervention) on an outcome. As described earlier, analytical studies can be observational (if the exposure is naturally determined) or interventional (if the researcher actively administers the intervention).

Directionality of study designs

Based on the direction of inquiry, study designs may be classified as forward-direction or backward-direction. In forward-direction studies, the researcher starts with determining the exposure to a risk factor and then assesses whether the outcome occurs at a future time point. This design is known as a cohort study. For example, a researcher can follow a group of smokers and a group of nonsmokers to determine the incidence of lung cancer in each. In backward-direction studies, the researcher begins by determining whether the outcome is present (cases vs. noncases [also called controls]) and then traces the presence of prior exposure to a risk factor. These are known as case–control studies. For example, a researcher identifies a group of normal-weight babies and a group of low-birth weight babies and then asks the mothers about their dietary habits during the index pregnancy.

Prospective versus retrospective study designs

The terms “prospective” and “retrospective” refer to the timing of the research in relation to the development of the outcome. In retrospective studies, the outcome of interest has already occurred (or not occurred – e.g., in controls) in each individual by the time s/he is enrolled, and the data are collected either from records or by asking participants to recall exposures. There is no follow-up of participants. By contrast, in prospective studies, the outcome (and sometimes even the exposure or intervention) has not occurred when the study starts and participants are followed up over a period of time to determine the occurrence of outcomes. Typically, most cohort studies are prospective studies (though there may be retrospective cohorts), whereas case–control studies are retrospective studies. An interventional study has to be, by definition, a prospective study since the investigator determines the exposure for each study participant and then follows them to observe outcomes.

The terms “prospective” versus “retrospective” studies can be confusing. Let us think of an investigator who starts a case–control study. To him/her, the process of enrolling cases and controls over a period of several months appears prospective. Hence, the use of these terms is best avoided. Or, at the very least, one must be clear that the terms relate to work flow for each individual study participant, and not to the study as a whole.

Classification of study designs

Figure 1 depicts a simple classification of research study designs. The Centre for Evidence-based Medicine has put forward a useful three-point algorithm which can help determine the design of a research study from its methods section:[ 1 ]

Classification of research study designs

- Does the study describe the characteristics of a sample or does it attempt to analyze (or draw inferences about) the relationship between two variables? – If no, then it is a descriptive study, and if yes, it is an analytical (inferential) study

- If analytical, did the investigator determine the exposure? – If no, it is an observational study, and if yes, it is an experimental study

- If observational, when was the outcome determined? – at the start of the study (case–control study), at the end of a period of follow-up (cohort study), or simultaneously (cross sectional).

In the next few pieces in the series, we will discuss various study designs in greater detail.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Cohort studies are a type of observational study that can be qualitative or quantitative in nature. They can be used to conduct both exploratory research and explanatory research depending on the research topic. In prospective cohort studies, data is collected over time to compare the occurrence of the outcome of interest in those who were ...

Examined from the perspective of research design, cohort studies are empirical because they collect and examine data. They are sample-based because a group of individuals is studied. ... As an example of a prospective cohort study, pregnant women can be recruited across the course of two years; relevant participant and gestational data can be ...

One famous example of a cohort study is the Nurses' Health Study. This was a large, long-running analysis of female health that began in 1976. ... Observational research methods. Research design ...

The cohort study design is an excellent method to understand an outcome or the natural history of a disease or condition in an identified study population ( Mann, 2012; Song & Chung, 2010 ). Since participants do not have the outcome or disease at study entry, the temporal causality between exposure and outcome (s) can be assessed using this ...

A prospective cohort study is a type of longitudinal research where a group of individuals sharing a common characteristic (cohort) is followed over time to observe and measure outcomes, often to investigate the effect of suspected risk factors. In a prospective study, the investigators will design the study, recruit subjects, and collect ...

It is a type of nonexperimental or observational study design. The term "cohort" refers to a group of people who have been included in a study by an event that is based on the definition decided by the researcher. For example, a cohort of people born in Mumbai in the year 1980. This will be called a "birth cohort.".

A study design where one or more samples (called cohorts) are followed prospectively and subsequent status evaluations with respect to a disease or outcome are conducted to determine which initial participants exposure characteristics (risk factors) are associated with it. As the study is conducted, outcome from participants in each cohort is ...

Abstract. Cohort studies are types of observational studies in which a cohort, or a group of individuals sharing some characteristic, are followed up over time, and outcomes are measured at one or more time points. Cohort studies can be classified as prospective or retrospective studies, and they have several advantages and disadvantages.

This design determines whether exposure to a risk factor affects an outcome. Cohort studies are a type of longitudinal study because they track the same set of subjects over time. For example, if researchers hypothesize that exposure to a chemical increases skin cancer, they can form a cohort based on exposure to that chemical.

A cohort is a group of individuals that share a common exposure or experience over a similar time period. Cohort studies are commonly used in medical practice because they offer a high level of evidence, provide useful data and offer flexibility in terms of their structure. They are a type of observational study, where a group of individuals is ...

Design, Analysis, and Reporting. Cohort studies are types of observational studies in which a cohort, or a group of individuals sharing some characteristic, are followed up over time, and outcomes are measured at one or more time points. Cohort studies can be classified as prospective or retrospective studies, and they have several advantages ...

Examined from the perspective of research design, cohort studies are empirical because they collect and examine data. They are sample-based because a group of individuals is studied. ... As an example of a prospective cohort study, pregnant women can be recruited across the course of two years; relevant participant and gestational data can be ...

research design, cohort studies are empir-ical because they collect and examine data. They are sample-based because a group of individuals is studied. They are always longitudinal because there is a follow-up, but can be prospectively HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Andrade C. Research Design: Cohort Studies. Indian J Psychol Med. 2022;44(2):189-191.

Cohort studies can be either prospective or retrospective. The type of cohort study is determined by the outcome status. If the outcome has not occurred at the start of the study, then it is a prospective study; if the outcome has already occurred, then it is a retrospective study. 4 Figure 1 presents a graphical representation of the designs of prospective and retrospective cohort studies.

Despite the ease of conducting cohort studies and the research value of such studies, few centers with long-term research goals conduct such studies. This article provides easy-to-understand practical guidance on how to start and run a cohort study. Key words: Cohort study, research design, schizophrenia A n earlier article1 in this series ex-

Prospective cohort studies require large sample sizes in order for any relationships or patterns to be meaningful. Researchers are unable to generate results if there is not enough data. ... E., & Locascio, J. J. (2018). Randomised controlled trials - the gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: randomised controlled trials ...

Example: In a retrospective cohort study researchers used previously collected data to investigate whether there was an association between birth experience and subsequent maternal care-giving attitudes and behaviour over a 12-month period ... Observational research methods. Research design II: cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies ...

A study design where one or more samples (called cohorts) are followed prospectively and subsequent status evaluations with respect to a disease or outcome are conducted to determine which initial participants exposure characteristics (risk factors) are associated with it. As the study is conducted, outcome from participants in each cohort is ...

Design. In a case-control study, a number of cases and noncases (controls) are identified, and the occurrence of one or more prior exposures is compared between groups to evaluate drug-outcome associations ( Figure 1 ). A case-control study runs in reverse relative to a cohort study. 21 As such, study inception occurs when a patient ...

Genetic association studies have focused on testing additive models in cohorts with European ancestry. Little is known about recessive effects on common diseases, specifically for non-European ancestry. Genes & Health is a cohort of British Pakistani and Bangladeshi individuals with elevated rates of consanguinity and endogamy, making it suitable to study recessive effects. We imputed variants ...

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about: Your overall research objectives and approach. Whether you'll rely on primary research or secondary research. Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects. Your data collection methods.

Research study design is a framework, or the set of methods and procedures used to collect and analyze data on variables specified in a particular research problem. Research study designs are of many types, each with its advantages and limitations. ... This design is known as a cohort study. For example, a researcher can follow a group of ...