- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

SocialEntrepreneurship →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

Undergrad Combines Engineering, Entrepreneurship to Advance Education

- by Katherine Panaligan

- May 01, 2024

For Gautham Pandian, a computer science and engineering junior in the College of Engineering at the University of California, Davis, engineering is about education and using technology to solve problems.

"The stories of innovators who used technology to create solutions and shape the future sparked my interest in engineering," said Pandian. "Engineering, to me, represents a discipline where creativity meets practicality, offering a path to directly impact society through innovation."

A long-term engineering project that Pandian is most proud of is Tallyrus, a web application that uses artificial intelligence to analyze and grade student papers. He co-founded the app and startup about a year ago with fellow UC Davis student Ashwin Chembu .

Pandian experienced the tediousness of grading first-hand while working as a tutor for over six years, where he often encountered challenges in grading which delayed the feedback students received. Recognizing the issue, Pandian decided to use his knowledge of software development to design a solution.

The web-based app utilizes natural language processing to analyze student essays, offering swift, detailed and consistent feedback for educators to use in their review process. Pandian hopes this modernization of grading proves to be an efficient and effective answer to this tedious necessity of teaching.

"Providing in-depth analysis and feedback quickly is challenging for teachers due to the sheer volume of papers they must handle," Pandian said. "We designed Tallyrus for students to receive comprehensive feedback [from their teachers] as quickly as possible, allowing students to learn and improve without this typical delay."

The team is steadily advancing the platform. Pandian's team took first place in the 2024 Student Creativity Empowerment and Entrepreneurship Slug Tank, a pitch competition at UC Santa Cruz. Tallyrus also recently took first place in the student division of the 2024 Startup Challenge Monterey Bay, a program by the CSU Monterey Bay College of Business.

Right now, the team is refining the Tallyrus platform's understanding of nuance and context and its adaptability to different writing subjects and grading rubrics.

Pandian believes that the atmosphere of innovation at UC Davis will help him strengthen his skills and develop Tallyrus further.

For Pandian, a major draw to UC Davis and the College of Engineering was the Student Startup Center , which provides resources for students developing products and businesses. Uniting entrepreneurship and engineering, the center allows Pandian to become involved in a community dedicated to innovation and supporting students.

"The opportunity to immerse myself in an environment that encourages taking academic learning beyond the classroom and applying it to real-world entrepreneurial ventures was exactly what I was looking for," Pandian said.

He currently participates in PLASMA , a 12-week accelerator program at the Student Startup Center that offers students educational and networking opportunities with mentors, industry leaders and other entrepreneurs.

Pandian is also part of the UC Davis branch of the AI Student Collective, a student organization focused on education about artificial intelligence. In the collective's education center, he teaches high school students about AI and its practical applications.

Off campus, he interns at IBM as a backend software developer where he is able to apply his technical skills to solve practical engineering issues.

Through his endeavors in engineering and entrepreneurship, helping people learn and solve problems motivates Pandian to continue innovating.

"Seeing our projects work in the real world is the kind of impact that makes all the hard work worth it."

Learn more about Tallyrus

Primary Category

- Open access

- Published: 18 April 2024

Research ethics and artificial intelligence for global health: perspectives from the global forum on bioethics in research

- James Shaw 1 , 13 ,

- Joseph Ali 2 , 3 ,

- Caesar A. Atuire 4 , 5 ,

- Phaik Yeong Cheah 6 ,

- Armando Guio Español 7 ,

- Judy Wawira Gichoya 8 ,

- Adrienne Hunt 9 ,

- Daudi Jjingo 10 ,

- Katherine Littler 9 ,

- Daniela Paolotti 11 &

- Effy Vayena 12

BMC Medical Ethics volume 25 , Article number: 46 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1145 Accesses

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

The ethical governance of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in health care and public health continues to be an urgent issue for attention in policy, research, and practice. In this paper we report on central themes related to challenges and strategies for promoting ethics in research involving AI in global health, arising from the Global Forum on Bioethics in Research (GFBR), held in Cape Town, South Africa in November 2022.

The GFBR is an annual meeting organized by the World Health Organization and supported by the Wellcome Trust, the US National Institutes of Health, the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the South African MRC. The forum aims to bring together ethicists, researchers, policymakers, research ethics committee members and other actors to engage with challenges and opportunities specifically related to research ethics. In 2022 the focus of the GFBR was “Ethics of AI in Global Health Research”. The forum consisted of 6 case study presentations, 16 governance presentations, and a series of small group and large group discussions. A total of 87 participants attended the forum from 31 countries around the world, representing disciplines of bioethics, AI, health policy, health professional practice, research funding, and bioinformatics. In this paper, we highlight central insights arising from GFBR 2022.

We describe the significance of four thematic insights arising from the forum: (1) Appropriateness of building AI, (2) Transferability of AI systems, (3) Accountability for AI decision-making and outcomes, and (4) Individual consent. We then describe eight recommendations for governance leaders to enhance the ethical governance of AI in global health research, addressing issues such as AI impact assessments, environmental values, and fair partnerships.

Conclusions

The 2022 Global Forum on Bioethics in Research illustrated several innovations in ethical governance of AI for global health research, as well as several areas in need of urgent attention internationally. This summary is intended to inform international and domestic efforts to strengthen research ethics and support the evolution of governance leadership to meet the demands of AI in global health research.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The ethical governance of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in health care and public health continues to be an urgent issue for attention in policy, research, and practice [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Beyond the growing number of AI applications being implemented in health care, capabilities of AI models such as Large Language Models (LLMs) expand the potential reach and significance of AI technologies across health-related fields [ 4 , 5 ]. Discussion about effective, ethical governance of AI technologies has spanned a range of governance approaches, including government regulation, organizational decision-making, professional self-regulation, and research ethics review [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. In this paper, we report on central themes related to challenges and strategies for promoting ethics in research involving AI in global health research, arising from the Global Forum on Bioethics in Research (GFBR), held in Cape Town, South Africa in November 2022. Although applications of AI for research, health care, and public health are diverse and advancing rapidly, the insights generated at the forum remain highly relevant from a global health perspective. After summarizing important context for work in this domain, we highlight categories of ethical issues emphasized at the forum for attention from a research ethics perspective internationally. We then outline strategies proposed for research, innovation, and governance to support more ethical AI for global health.

In this paper, we adopt the definition of AI systems provided by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) as our starting point. Their definition states that an AI system is “a machine-based system that can, for a given set of human-defined objectives, make predictions, recommendations, or decisions influencing real or virtual environments. AI systems are designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy” [ 9 ]. The conceptualization of an algorithm as helping to constitute an AI system, along with hardware, other elements of software, and a particular context of use, illustrates the wide variety of ways in which AI can be applied. We have found it useful to differentiate applications of AI in research as those classified as “AI systems for discovery” and “AI systems for intervention”. An AI system for discovery is one that is intended to generate new knowledge, for example in drug discovery or public health research in which researchers are seeking potential targets for intervention, innovation, or further research. An AI system for intervention is one that directly contributes to enacting an intervention in a particular context, for example informing decision-making at the point of care or assisting with accuracy in a surgical procedure.

The mandate of the GFBR is to take a broad view of what constitutes research and its regulation in global health, with special attention to bioethics in Low- and Middle- Income Countries. AI as a group of technologies demands such a broad view. AI development for health occurs in a variety of environments, including universities and academic health sciences centers where research ethics review remains an important element of the governance of science and innovation internationally [ 10 , 11 ]. In these settings, research ethics committees (RECs; also known by different names such as Institutional Review Boards or IRBs) make decisions about the ethical appropriateness of projects proposed by researchers and other institutional members, ultimately determining whether a given project is allowed to proceed on ethical grounds [ 12 ].

However, research involving AI for health also takes place in large corporations and smaller scale start-ups, which in some jurisdictions fall outside the scope of research ethics regulation. In the domain of AI, the question of what constitutes research also becomes blurred. For example, is the development of an algorithm itself considered a part of the research process? Or only when that algorithm is tested under the formal constraints of a systematic research methodology? In this paper we take an inclusive view, in which AI development is included in the definition of research activity and within scope for our inquiry, regardless of the setting in which it takes place. This broad perspective characterizes the approach to “research ethics” we take in this paper, extending beyond the work of RECs to include the ethical analysis of the wide range of activities that constitute research as the generation of new knowledge and intervention in the world.

Ethical governance of AI in global health

The ethical governance of AI for global health has been widely discussed in recent years. The World Health Organization (WHO) released its guidelines on ethics and governance of AI for health in 2021, endorsing a set of six ethical principles and exploring the relevance of those principles through a variety of use cases. The WHO guidelines also provided an overview of AI governance, defining governance as covering “a range of steering and rule-making functions of governments and other decision-makers, including international health agencies, for the achievement of national health policy objectives conducive to universal health coverage.” (p. 81) The report usefully provided a series of recommendations related to governance of seven domains pertaining to AI for health: data, benefit sharing, the private sector, the public sector, regulation, policy observatories/model legislation, and global governance. The report acknowledges that much work is yet to be done to advance international cooperation on AI governance, especially related to prioritizing voices from Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) in global dialogue.

One important point emphasized in the WHO report that reinforces the broader literature on global governance of AI is the distribution of responsibility across a wide range of actors in the AI ecosystem. This is especially important to highlight when focused on research for global health, which is specifically about work that transcends national borders. Alami et al. (2020) discussed the unique risks raised by AI research in global health, ranging from the unavailability of data in many LMICs required to train locally relevant AI models to the capacity of health systems to absorb new AI technologies that demand the use of resources from elsewhere in the system. These observations illustrate the need to identify the unique issues posed by AI research for global health specifically, and the strategies that can be employed by all those implicated in AI governance to promote ethically responsible use of AI in global health research.

RECs and the regulation of research involving AI

RECs represent an important element of the governance of AI for global health research, and thus warrant further commentary as background to our paper. Despite the importance of RECs, foundational questions have been raised about their capabilities to accurately understand and address ethical issues raised by studies involving AI. Rahimzadeh et al. (2023) outlined how RECs in the United States are under-prepared to align with recent federal policy requiring that RECs review data sharing and management plans with attention to the unique ethical issues raised in AI research for health [ 13 ]. Similar research in South Africa identified variability in understanding of existing regulations and ethical issues associated with health-related big data sharing and management among research ethics committee members [ 14 , 15 ]. The effort to address harms accruing to groups or communities as opposed to individuals whose data are included in AI research has also been identified as a unique challenge for RECs [ 16 , 17 ]. Doerr and Meeder (2022) suggested that current regulatory frameworks for research ethics might actually prevent RECs from adequately addressing such issues, as they are deemed out of scope of REC review [ 16 ]. Furthermore, research in the United Kingdom and Canada has suggested that researchers using AI methods for health tend to distinguish between ethical issues and social impact of their research, adopting an overly narrow view of what constitutes ethical issues in their work [ 18 ].

The challenges for RECs in adequately addressing ethical issues in AI research for health care and public health exceed a straightforward survey of ethical considerations. As Ferretti et al. (2021) contend, some capabilities of RECs adequately cover certain issues in AI-based health research, such as the common occurrence of conflicts of interest where researchers who accept funds from commercial technology providers are implicitly incentivized to produce results that align with commercial interests [ 12 ]. However, some features of REC review require reform to adequately meet ethical needs. Ferretti et al. outlined weaknesses of RECs that are longstanding and those that are novel to AI-related projects, proposing a series of directions for development that are regulatory, procedural, and complementary to REC functionality. The work required on a global scale to update the REC function in response to the demands of research involving AI is substantial.

These issues take greater urgency in the context of global health [ 19 ]. Teixeira da Silva (2022) described the global practice of “ethics dumping”, where researchers from high income countries bring ethically contentious practices to RECs in low-income countries as a strategy to gain approval and move projects forward [ 20 ]. Although not yet systematically documented in AI research for health, risk of ethics dumping in AI research is high. Evidence is already emerging of practices of “health data colonialism”, in which AI researchers and developers from large organizations in high-income countries acquire data to build algorithms in LMICs to avoid stricter regulations [ 21 ]. This specific practice is part of a larger collection of practices that characterize health data colonialism, involving the broader exploitation of data and the populations they represent primarily for commercial gain [ 21 , 22 ]. As an additional complication, AI algorithms trained on data from high-income contexts are unlikely to apply in straightforward ways to LMIC settings [ 21 , 23 ]. In the context of global health, there is widespread acknowledgement about the need to not only enhance the knowledge base of REC members about AI-based methods internationally, but to acknowledge the broader shifts required to encourage their capabilities to more fully address these and other ethical issues associated with AI research for health [ 8 ].

Although RECs are an important part of the story of the ethical governance of AI for global health research, they are not the only part. The responsibilities of supra-national entities such as the World Health Organization, national governments, organizational leaders, commercial AI technology providers, health care professionals, and other groups continue to be worked out internationally. In this context of ongoing work, examining issues that demand attention and strategies to address them remains an urgent and valuable task.

The GFBR is an annual meeting organized by the World Health Organization and supported by the Wellcome Trust, the US National Institutes of Health, the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the South African MRC. The forum aims to bring together ethicists, researchers, policymakers, REC members and other actors to engage with challenges and opportunities specifically related to research ethics. Each year the GFBR meeting includes a series of case studies and keynotes presented in plenary format to an audience of approximately 100 people who have applied and been competitively selected to attend, along with small-group breakout discussions to advance thinking on related issues. The specific topic of the forum changes each year, with past topics including ethical issues in research with people living with mental health conditions (2021), genome editing (2019), and biobanking/data sharing (2018). The forum is intended to remain grounded in the practical challenges of engaging in research ethics, with special interest in low resource settings from a global health perspective. A post-meeting fellowship scheme is open to all LMIC participants, providing a unique opportunity to apply for funding to further explore and address the ethical challenges that are identified during the meeting.

In 2022, the focus of the GFBR was “Ethics of AI in Global Health Research”. The forum consisted of 6 case study presentations (both short and long form) reporting on specific initiatives related to research ethics and AI for health, and 16 governance presentations (both short and long form) reporting on actual approaches to governing AI in different country settings. A keynote presentation from Professor Effy Vayena addressed the topic of the broader context for AI ethics in a rapidly evolving field. A total of 87 participants attended the forum from 31 countries around the world, representing disciplines of bioethics, AI, health policy, health professional practice, research funding, and bioinformatics. The 2-day forum addressed a wide range of themes. The conference report provides a detailed overview of each of the specific topics addressed while a policy paper outlines the cross-cutting themes (both documents are available at the GFBR website: https://www.gfbr.global/past-meetings/16th-forum-cape-town-south-africa-29-30-november-2022/ ). As opposed to providing a detailed summary in this paper, we aim to briefly highlight central issues raised, solutions proposed, and the challenges facing the research ethics community in the years to come.

In this way, our primary aim in this paper is to present a synthesis of the challenges and opportunities raised at the GFBR meeting and in the planning process, followed by our reflections as a group of authors on their significance for governance leaders in the coming years. We acknowledge that the views represented at the meeting and in our results are a partial representation of the universe of views on this topic; however, the GFBR leadership invested a great deal of resources in convening a deeply diverse and thoughtful group of researchers and practitioners working on themes of bioethics related to AI for global health including those based in LMICs. We contend that it remains rare to convene such a strong group for an extended time and believe that many of the challenges and opportunities raised demand attention for more ethical futures of AI for health. Nonetheless, our results are primarily descriptive and are thus not explicitly grounded in a normative argument. We make effort in the Discussion section to contextualize our results by describing their significance and connecting them to broader efforts to reform global health research and practice.

Uniquely important ethical issues for AI in global health research

Presentations and group dialogue over the course of the forum raised several issues for consideration, and here we describe four overarching themes for the ethical governance of AI in global health research. Brief descriptions of each issue can be found in Table 1 . Reports referred to throughout the paper are available at the GFBR website provided above.

The first overarching thematic issue relates to the appropriateness of building AI technologies in response to health-related challenges in the first place. Case study presentations referred to initiatives where AI technologies were highly appropriate, such as in ear shape biometric identification to more accurately link electronic health care records to individual patients in Zambia (Alinani Simukanga). Although important ethical issues were raised with respect to privacy, trust, and community engagement in this initiative, the AI-based solution was appropriately matched to the challenge of accurately linking electronic records to specific patient identities. In contrast, forum participants raised questions about the appropriateness of an initiative using AI to improve the quality of handwashing practices in an acute care hospital in India (Niyoshi Shah), which led to gaming the algorithm. Overall, participants acknowledged the dangers of techno-solutionism, in which AI researchers and developers treat AI technologies as the most obvious solutions to problems that in actuality demand much more complex strategies to address [ 24 ]. However, forum participants agreed that RECs in different contexts have differing degrees of power to raise issues of the appropriateness of an AI-based intervention.

The second overarching thematic issue related to whether and how AI-based systems transfer from one national health context to another. One central issue raised by a number of case study presentations related to the challenges of validating an algorithm with data collected in a local environment. For example, one case study presentation described a project that would involve the collection of personally identifiable data for sensitive group identities, such as tribe, clan, or religion, in the jurisdictions involved (South Africa, Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda and the US; Gakii Masunga). Doing so would enable the team to ensure that those groups were adequately represented in the dataset to ensure the resulting algorithm was not biased against specific community groups when deployed in that context. However, some members of these communities might desire to be represented in the dataset, whereas others might not, illustrating the need to balance autonomy and inclusivity. It was also widely recognized that collecting these data is an immense challenge, particularly when historically oppressive practices have led to a low-trust environment for international organizations and the technologies they produce. It is important to note that in some countries such as South Africa and Rwanda, it is illegal to collect information such as race and tribal identities, re-emphasizing the importance for cultural awareness and avoiding “one size fits all” solutions.

The third overarching thematic issue is related to understanding accountabilities for both the impacts of AI technologies and governance decision-making regarding their use. Where global health research involving AI leads to longer-term harms that might fall outside the usual scope of issues considered by a REC, who is to be held accountable, and how? This question was raised as one that requires much further attention, with law being mixed internationally regarding the mechanisms available to hold researchers, innovators, and their institutions accountable over the longer term. However, it was recognized in breakout group discussion that many jurisdictions are developing strong data protection regimes related specifically to international collaboration for research involving health data. For example, Kenya’s Data Protection Act requires that any internationally funded projects have a local principal investigator who will hold accountability for how data are shared and used [ 25 ]. The issue of research partnerships with commercial entities was raised by many participants in the context of accountability, pointing toward the urgent need for clear principles related to strategies for engagement with commercial technology companies in global health research.

The fourth and final overarching thematic issue raised here is that of consent. The issue of consent was framed by the widely shared recognition that models of individual, explicit consent might not produce a supportive environment for AI innovation that relies on the secondary uses of health-related datasets to build AI algorithms. Given this recognition, approaches such as community oversight of health data uses were suggested as a potential solution. However, the details of implementing such community oversight mechanisms require much further attention, particularly given the unique perspectives on health data in different country settings in global health research. Furthermore, some uses of health data do continue to require consent. One case study of South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia and Uganda suggested that when health data are shared across borders, individual consent remains necessary when data is transferred from certain countries (Nezerith Cengiz). Broader clarity is necessary to support the ethical governance of health data uses for AI in global health research.

Recommendations for ethical governance of AI in global health research

Dialogue at the forum led to a range of suggestions for promoting ethical conduct of AI research for global health, related to the various roles of actors involved in the governance of AI research broadly defined. The strategies are written for actors we refer to as “governance leaders”, those people distributed throughout the AI for global health research ecosystem who are responsible for ensuring the ethical and socially responsible conduct of global health research involving AI (including researchers themselves). These include RECs, government regulators, health care leaders, health professionals, corporate social accountability officers, and others. Enacting these strategies would bolster the ethical governance of AI for global health more generally, enabling multiple actors to fulfill their roles related to governing research and development activities carried out across multiple organizations, including universities, academic health sciences centers, start-ups, and technology corporations. Specific suggestions are summarized in Table 2 .

First, forum participants suggested that governance leaders including RECs, should remain up to date on recent advances in the regulation of AI for health. Regulation of AI for health advances rapidly and takes on different forms in jurisdictions around the world. RECs play an important role in governance, but only a partial role; it was deemed important for RECs to acknowledge how they fit within a broader governance ecosystem in order to more effectively address the issues within their scope. Not only RECs but organizational leaders responsible for procurement, researchers, and commercial actors should all commit to efforts to remain up to date about the relevant approaches to regulating AI for health care and public health in jurisdictions internationally. In this way, governance can more adequately remain up to date with advances in regulation.

Second, forum participants suggested that governance leaders should focus on ethical governance of health data as a basis for ethical global health AI research. Health data are considered the foundation of AI development, being used to train AI algorithms for various uses [ 26 ]. By focusing on ethical governance of health data generation, sharing, and use, multiple actors will help to build an ethical foundation for AI development among global health researchers.

Third, forum participants believed that governance processes should incorporate AI impact assessments where appropriate. An AI impact assessment is the process of evaluating the potential effects, both positive and negative, of implementing an AI algorithm on individuals, society, and various stakeholders, generally over time frames specified in advance of implementation [ 27 ]. Although not all types of AI research in global health would warrant an AI impact assessment, this is especially relevant for those studies aiming to implement an AI system for intervention into health care or public health. Organizations such as RECs can use AI impact assessments to boost understanding of potential harms at the outset of a research project, encouraging researchers to more deeply consider potential harms in the development of their study.

Fourth, forum participants suggested that governance decisions should incorporate the use of environmental impact assessments, or at least the incorporation of environment values when assessing the potential impact of an AI system. An environmental impact assessment involves evaluating and anticipating the potential environmental effects of a proposed project to inform ethical decision-making that supports sustainability [ 28 ]. Although a relatively new consideration in research ethics conversations [ 29 ], the environmental impact of building technologies is a crucial consideration for the public health commitment to environmental sustainability. Governance leaders can use environmental impact assessments to boost understanding of potential environmental harms linked to AI research projects in global health over both the shorter and longer terms.

Fifth, forum participants suggested that governance leaders should require stronger transparency in the development of AI algorithms in global health research. Transparency was considered essential in the design and development of AI algorithms for global health to ensure ethical and accountable decision-making throughout the process. Furthermore, whether and how researchers have considered the unique contexts into which such algorithms may be deployed can be surfaced through stronger transparency, for example in describing what primary considerations were made at the outset of the project and which stakeholders were consulted along the way. Sharing information about data provenance and methods used in AI development will also enhance the trustworthiness of the AI-based research process.

Sixth, forum participants suggested that governance leaders can encourage or require community engagement at various points throughout an AI project. It was considered that engaging patients and communities is crucial in AI algorithm development to ensure that the technology aligns with community needs and values. However, participants acknowledged that this is not a straightforward process. Effective community engagement requires lengthy commitments to meeting with and hearing from diverse communities in a given setting, and demands a particular set of skills in communication and dialogue that are not possessed by all researchers. Encouraging AI researchers to begin this process early and build long-term partnerships with community members is a promising strategy to deepen community engagement in AI research for global health. One notable recommendation was that research funders have an opportunity to incentivize and enable community engagement with funds dedicated to these activities in AI research in global health.

Seventh, forum participants suggested that governance leaders can encourage researchers to build strong, fair partnerships between institutions and individuals across country settings. In a context of longstanding imbalances in geopolitical and economic power, fair partnerships in global health demand a priori commitments to share benefits related to advances in medical technologies, knowledge, and financial gains. Although enforcement of this point might be beyond the remit of RECs, commentary will encourage researchers to consider stronger, fairer partnerships in global health in the longer term.

Eighth, it became evident that it is necessary to explore new forms of regulatory experimentation given the complexity of regulating a technology of this nature. In addition, the health sector has a series of particularities that make it especially complicated to generate rules that have not been previously tested. Several participants highlighted the desire to promote spaces for experimentation such as regulatory sandboxes or innovation hubs in health. These spaces can have several benefits for addressing issues surrounding the regulation of AI in the health sector, such as: (i) increasing the capacities and knowledge of health authorities about this technology; (ii) identifying the major problems surrounding AI regulation in the health sector; (iii) establishing possibilities for exchange and learning with other authorities; (iv) promoting innovation and entrepreneurship in AI in health; and (vi) identifying the need to regulate AI in this sector and update other existing regulations.

Ninth and finally, forum participants believed that the capabilities of governance leaders need to evolve to better incorporate expertise related to AI in ways that make sense within a given jurisdiction. With respect to RECs, for example, it might not make sense for every REC to recruit a member with expertise in AI methods. Rather, it will make more sense in some jurisdictions to consult with members of the scientific community with expertise in AI when research protocols are submitted that demand such expertise. Furthermore, RECs and other approaches to research governance in jurisdictions around the world will need to evolve in order to adopt the suggestions outlined above, developing processes that apply specifically to the ethical governance of research using AI methods in global health.

Research involving the development and implementation of AI technologies continues to grow in global health, posing important challenges for ethical governance of AI in global health research around the world. In this paper we have summarized insights from the 2022 GFBR, focused specifically on issues in research ethics related to AI for global health research. We summarized four thematic challenges for governance related to AI in global health research and nine suggestions arising from presentations and dialogue at the forum. In this brief discussion section, we present an overarching observation about power imbalances that frames efforts to evolve the role of governance in global health research, and then outline two important opportunity areas as the field develops to meet the challenges of AI in global health research.

Dialogue about power is not unfamiliar in global health, especially given recent contributions exploring what it would mean to de-colonize global health research, funding, and practice [ 30 , 31 ]. Discussions of research ethics applied to AI research in global health contexts are deeply infused with power imbalances. The existing context of global health is one in which high-income countries primarily located in the “Global North” charitably invest in projects taking place primarily in the “Global South” while recouping knowledge, financial, and reputational benefits [ 32 ]. With respect to AI development in particular, recent examples of digital colonialism frame dialogue about global partnerships, raising attention to the role of large commercial entities and global financial capitalism in global health research [ 21 , 22 ]. Furthermore, the power of governance organizations such as RECs to intervene in the process of AI research in global health varies widely around the world, depending on the authorities assigned to them by domestic research governance policies. These observations frame the challenges outlined in our paper, highlighting the difficulties associated with making meaningful change in this field.

Despite these overarching challenges of the global health research context, there are clear strategies for progress in this domain. Firstly, AI innovation is rapidly evolving, which means approaches to the governance of AI for health are rapidly evolving too. Such rapid evolution presents an important opportunity for governance leaders to clarify their vision and influence over AI innovation in global health research, boosting the expertise, structure, and functionality required to meet the demands of research involving AI. Secondly, the research ethics community has strong international ties, linked to a global scholarly community that is committed to sharing insights and best practices around the world. This global community can be leveraged to coordinate efforts to produce advances in the capabilities and authorities of governance leaders to meaningfully govern AI research for global health given the challenges summarized in our paper.

Limitations

Our paper includes two specific limitations that we address explicitly here. First, it is still early in the lifetime of the development of applications of AI for use in global health, and as such, the global community has had limited opportunity to learn from experience. For example, there were many fewer case studies, which detail experiences with the actual implementation of an AI technology, submitted to GFBR 2022 for consideration than was expected. In contrast, there were many more governance reports submitted, which detail the processes and outputs of governance processes that anticipate the development and dissemination of AI technologies. This observation represents both a success and a challenge. It is a success that so many groups are engaging in anticipatory governance of AI technologies, exploring evidence of their likely impacts and governing technologies in novel and well-designed ways. It is a challenge that there is little experience to build upon of the successful implementation of AI technologies in ways that have limited harms while promoting innovation. Further experience with AI technologies in global health will contribute to revising and enhancing the challenges and recommendations we have outlined in our paper.

Second, global trends in the politics and economics of AI technologies are evolving rapidly. Although some nations are advancing detailed policy approaches to regulating AI more generally, including for uses in health care and public health, the impacts of corporate investments in AI and political responses related to governance remain to be seen. The excitement around large language models (LLMs) and large multimodal models (LMMs) has drawn deeper attention to the challenges of regulating AI in any general sense, opening dialogue about health sector-specific regulations. The direction of this global dialogue, strongly linked to high-profile corporate actors and multi-national governance institutions, will strongly influence the development of boundaries around what is possible for the ethical governance of AI for global health. We have written this paper at a point when these developments are proceeding rapidly, and as such, we acknowledge that our recommendations will need updating as the broader field evolves.

Ultimately, coordination and collaboration between many stakeholders in the research ethics ecosystem will be necessary to strengthen the ethical governance of AI in global health research. The 2022 GFBR illustrated several innovations in ethical governance of AI for global health research, as well as several areas in need of urgent attention internationally. This summary is intended to inform international and domestic efforts to strengthen research ethics and support the evolution of governance leadership to meet the demands of AI in global health research.

Data availability

All data and materials analyzed to produce this paper are available on the GFBR website: https://www.gfbr.global/past-meetings/16th-forum-cape-town-south-africa-29-30-november-2022/ .

Clark P, Kim J, Aphinyanaphongs Y, Marketing, Food US. Drug Administration Clearance of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Enabled Software in and as Medical devices: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2321792–2321792.

Article Google Scholar

Potnis KC, Ross JS, Aneja S, Gross CP, Richman IB. Artificial intelligence in breast cancer screening: evaluation of FDA device regulation and future recommendations. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(12):1306–12.

Siala H, Wang Y. SHIFTing artificial intelligence to be responsible in healthcare: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2022;296:114782.

Yang X, Chen A, PourNejatian N, Shin HC, Smith KE, Parisien C, et al. A large language model for electronic health records. NPJ Digit Med. 2022;5(1):194.

Meskó B, Topol EJ. The imperative for regulatory oversight of large language models (or generative AI) in healthcare. NPJ Digit Med. 2023;6(1):120.

Jobin A, Ienca M, Vayena E. The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nat Mach Intell. 2019;1(9):389–99.

Minssen T, Vayena E, Cohen IG. The challenges for Regulating Medical Use of ChatGPT and other large Language models. JAMA. 2023.

Ho CWL, Malpani R. Scaling up the research ethics framework for healthcare machine learning as global health ethics and governance. Am J Bioeth. 2022;22(5):36–8.

Yeung K. Recommendation of the council on artificial intelligence (OECD). Int Leg Mater. 2020;59(1):27–34.

Maddox TM, Rumsfeld JS, Payne PR. Questions for artificial intelligence in health care. JAMA. 2019;321(1):31–2.

Dzau VJ, Balatbat CA, Ellaissi WF. Revisiting academic health sciences systems a decade later: discovery to health to population to society. Lancet. 2021;398(10318):2300–4.

Ferretti A, Ienca M, Sheehan M, Blasimme A, Dove ES, Farsides B, et al. Ethics review of big data research: what should stay and what should be reformed? BMC Med Ethics. 2021;22(1):1–13.

Rahimzadeh V, Serpico K, Gelinas L. Institutional review boards need new skills to review data sharing and management plans. Nat Med. 2023;1–3.

Kling S, Singh S, Burgess TL, Nair G. The role of an ethics advisory committee in data science research in sub-saharan Africa. South Afr J Sci. 2023;119(5–6):1–3.

Google Scholar

Cengiz N, Kabanda SM, Esterhuizen TM, Moodley K. Exploring perspectives of research ethics committee members on the governance of big data in sub-saharan Africa. South Afr J Sci. 2023;119(5–6):1–9.

Doerr M, Meeder S. Big health data research and group harm: the scope of IRB review. Ethics Hum Res. 2022;44(4):34–8.

Ballantyne A, Stewart C. Big data and public-private partnerships in healthcare and research: the application of an ethics framework for big data in health and research. Asian Bioeth Rev. 2019;11(3):315–26.

Samuel G, Chubb J, Derrick G. Boundaries between research ethics and ethical research use in artificial intelligence health research. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2021;16(3):325–37.

Murphy K, Di Ruggiero E, Upshur R, Willison DJ, Malhotra N, Cai JC, et al. Artificial intelligence for good health: a scoping review of the ethics literature. BMC Med Ethics. 2021;22(1):1–17.

Teixeira da Silva JA. Handling ethics dumping and neo-colonial research: from the laboratory to the academic literature. J Bioethical Inq. 2022;19(3):433–43.

Ferryman K. The dangers of data colonialism in precision public health. Glob Policy. 2021;12:90–2.

Couldry N, Mejias UA. Data colonialism: rethinking big data’s relation to the contemporary subject. Telev New Media. 2019;20(4):336–49.

Organization WH. Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health: WHO guidance. 2021.

Metcalf J, Moss E. Owning ethics: corporate logics, silicon valley, and the institutionalization of ethics. Soc Res Int Q. 2019;86(2):449–76.

Data Protection Act - OFFICE OF THE DATA PROTECTION COMMISSIONER KENYA [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Sep 30]. https://www.odpc.go.ke/dpa-act/ .

Sharon T, Lucivero F. Introduction to the special theme: the expansion of the health data ecosystem–rethinking data ethics and governance. Big Data & Society. Volume 6. London, England: SAGE Publications Sage UK; 2019. p. 2053951719852969.

Reisman D, Schultz J, Crawford K, Whittaker M. Algorithmic impact assessments: a practical Framework for Public Agency. AI Now. 2018.

Morgan RK. Environmental impact assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 2012;30(1):5–14.

Samuel G, Richie C. Reimagining research ethics to include environmental sustainability: a principled approach, including a case study of data-driven health research. J Med Ethics. 2023;49(6):428–33.

Kwete X, Tang K, Chen L, Ren R, Chen Q, Wu Z, et al. Decolonizing global health: what should be the target of this movement and where does it lead us? Glob Health Res Policy. 2022;7(1):3.

Abimbola S, Asthana S, Montenegro C, Guinto RR, Jumbam DT, Louskieter L, et al. Addressing power asymmetries in global health: imperatives in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS Med. 2021;18(4):e1003604.

Benatar S. Politics, power, poverty and global health: systems and frames. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;5(10):599.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the outstanding contributions of the attendees of GFBR 2022 in Cape Town, South Africa. This paper is authored by members of the GFBR 2022 Planning Committee. We would like to acknowledge additional members Tamra Lysaght, National University of Singapore, and Niresh Bhagwandin, South African Medical Research Council, for their input during the planning stages and as reviewers of the applications to attend the Forum.

This work was supported by Wellcome [222525/Z/21/Z], the US National Institutes of Health, the UK Medical Research Council (part of UK Research and Innovation), and the South African Medical Research Council through funding to the Global Forum on Bioethics in Research.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Physical Therapy, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Berman Institute of Bioethics, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA

Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA

Department of Philosophy and Classics, University of Ghana, Legon-Accra, Ghana

Caesar A. Atuire

Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

Phaik Yeong Cheah

Berkman Klein Center, Harvard University, Bogotá, Colombia

Armando Guio Español

Department of Radiology and Informatics, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA

Judy Wawira Gichoya

Health Ethics & Governance Unit, Research for Health Department, Science Division, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Adrienne Hunt & Katherine Littler

African Center of Excellence in Bioinformatics and Data Intensive Science, Infectious Diseases Institute, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

Daudi Jjingo

ISI Foundation, Turin, Italy

Daniela Paolotti

Department of Health Sciences and Technology, ETH Zurich, Zürich, Switzerland

Effy Vayena

Joint Centre for Bioethics, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

JS led the writing, contributed to conceptualization and analysis, critically reviewed and provided feedback on drafts of this paper, and provided final approval of the paper. JA contributed to conceptualization and analysis, critically reviewed and provided feedback on drafts of this paper, and provided final approval of the paper. CA contributed to conceptualization and analysis, critically reviewed and provided feedback on drafts of this paper, and provided final approval of the paper. PYC contributed to conceptualization and analysis, critically reviewed and provided feedback on drafts of this paper, and provided final approval of the paper. AE contributed to conceptualization and analysis, critically reviewed and provided feedback on drafts of this paper, and provided final approval of the paper. JWG contributed to conceptualization and analysis, critically reviewed and provided feedback on drafts of this paper, and provided final approval of the paper. AH contributed to conceptualization and analysis, critically reviewed and provided feedback on drafts of this paper, and provided final approval of the paper. DJ contributed to conceptualization and analysis, critically reviewed and provided feedback on drafts of this paper, and provided final approval of the paper. KL contributed to conceptualization and analysis, critically reviewed and provided feedback on drafts of this paper, and provided final approval of the paper. DP contributed to conceptualization and analysis, critically reviewed and provided feedback on drafts of this paper, and provided final approval of the paper. EV contributed to conceptualization and analysis, critically reviewed and provided feedback on drafts of this paper, and provided final approval of the paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to James Shaw .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Shaw, J., Ali, J., Atuire, C.A. et al. Research ethics and artificial intelligence for global health: perspectives from the global forum on bioethics in research. BMC Med Ethics 25 , 46 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-024-01044-w

Download citation

Received : 31 October 2023

Accepted : 01 April 2024

Published : 18 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-024-01044-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Artificial intelligence

- Machine learning

- Research ethics

- Global health

BMC Medical Ethics

ISSN: 1472-6939

- General enquiries: [email protected]

The impact of entrepreneurship on economic, social and environmental welfare and its determinants: a systematic review

- Open access

- Published: 04 August 2020

- Volume 71 , pages 553–584, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Thomas Neumann ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7189-8159 1

87k Accesses

47 Citations

Explore all metrics

This paper presents a systematic review of (a) the impact of entrepreneurship on economic, social and environmental welfare and (b) the factors determining this impact. Research over the past 25 years shows that entrepreneurship is one cause of macroeconomic development, but that the relationship between entrepreneurship and welfare is very complex. The literature emphasizes that the generally positive impact of entrepreneurship depends on a variety of associated determinants which affect the degree of this impact. This paper seeks to contribute to the literature in three ways. First, it updates and extends existing literature reviews with the recently emerged research stream on developing countries, and incorporates studies analysing not only the impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth and welfare but also on social and environmental welfare. Second, it identifies and structures the current knowledge on the determinants of this impact. And third, it provides a roadmap for future research which targets the shortcomings of the existing empirical literature on this topic. The review of 102 publications reveals that the literature generally lacks research which (a) goes beyond the common measures of economic welfare, (b) examines the long-term impact of entrepreneurship and (c) focuses on emerging and developing countries. Regarding the determinants of the impact of entrepreneurship, the results highlight the need for empirical research which addresses both already investigated determinants which require more attention (e.g. survival, internationalisation, qualifications) and those which are currently only suspected of shaping the impact of entrepreneurship (e.g. firm performance, the entrepreneur’s socio-cultural background and motivations).

Similar content being viewed by others

Economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on entrepreneurship and small businesses

Artificial Intelligence and Economic Development: An Evolutionary Investigation and Systematic Review

Corporate entrepreneurship: a systematic literature review and future research agenda

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Entrepreneurship and its possible impact on the economy have been studied extensively during the past two decades but the research field still continues to develop and grow. The majority of studies from a variety of scientific disciplines have found empirical evidence for a significant positive macroeconomic impact of entrepreneurship (e.g. Atems and Shand 2018 ; Audretsch and Keilbach 2004a ; Fritsch and Mueller 2004 , 2008 ). However, several empirical studies show that the macroeconomic impact of entrepreneurship can also be negative under certain conditions (e.g. Carree and Thurik 2008 ; Andersson and Noseleit 2011 ; Fritsch and Mueller 2004 , 2008 ). Potential explanations for these contradictory results are to be found in the complex relationship between entrepreneurship and economic growth. Already some of the very first empirical studies on the macroeconomic impact of entrepreneurship showed that factors such as industrial affiliation (Fritsch 1996 ), the country’s level of development and the local density of business owners (Carree et al. 2002 ) significantly determine the impact of entrepreneurship. With more entrepreneurship datasets becoming available, researchers found evidence that only a small number of new firms such as particularly innovative new firms and firms with high-growth expectations create economic value and initiate Schumpeter’s process of ‘creative destruction’ (e.g. Szerb et al. 2018 ; Valliere and Peterson 2009 ; van Oort and Bosma 2013 ; Wong et al. 2005 ). However, over the past decade, researchers have identified a multitude of other relevant determinants (e.g. survival rates of new firms, institutional and cultural settings, motivations and qualifications of the entrepreneur), thereby drawing an increasingly complex web of interrelated determinants around the macroeconomic impact of entrepreneurship. This complexity combined with the fact that the research on determinants is scattered and mostly based on separate analyses of determinants leads to a number of hitherto unidentified research opportunities. In order to detect these opportunities and to exploit them in a targeted manner, a structured overview of the current knowledge on the determinants of the macroeconomic impact of entrepreneurship is required. In this context, a structured overview is not only essential for the scientific entrepreneurship community but also for politicians all over the world who need detailed information on the impact of entrepreneurship to promote the right types of entrepreneurship in the right situations.

To ensure that this information prepared for policy makers are truly comprehensive, it is essential that state-of-the-art research considers not only economic outcomes of entrepreneurship but also its social and environmental effects. This demand for a more holistic impact analyses is based on the call of economists who have been emphasizing since the 1970’s that economic development may is a significant part of welfare, but that social and environmental dimensions need to be considered as well (Daly et al. 1994 ; Meadows et al. 1972 ; Nordhaus and Tobin 1972 ). Tietenberg and Lewis ( 2012 , p. 553) summarised the economic, social and environmental effects in a holistic welfare definition and state that a “true measure of development would increase whenever we, as a nation or as a world, were better off and decrease whenever we were worse off”. This understatement is in line with many authors who recently highlighted the importance of entrepreneurship for social and environmental welfare (e.g. Alvarez and Barney 2014 ; Dhahri and Omri 2018 ; McMullen 2011 ). Entrepreneurship research has come to see entrepreneurs as a solution for social inequality and environmental degradation rather than a possible cause of them (Gast et al. 2017 ; Munoz and Cohen 2018 ; Terán-Yépez et al. 2020 ). This scientific consent of the past 50 years clearly illustrates how important it is that econometric research on entrepreneurship incorporates research on the economic as well as on the social and environmental impact of entrepreneurship. Footnote 1

Considering that the research on the macroeconomic impacts of entrepreneurship has been gaining increasing recognition over the last two decades and across a wide range of disciplines (Urbano et al. 2019a ), literature reviews must be conducted periodically to synthesize and reflect recent progress and to stimulate future research. Several high-quality reviews have already summarized the significant amount of research on the impact of entrepreneurship on the economy. Wennekers and Thurik ( 1999 ) were the first who discussed the link between entrepreneurship and economic growth in a narrative literature analysis. With their summary of the theoretical knowledge of that time and the first framework of the entrepreneurial impact the authors laid the groundwork for the following decade of empirical research on that matter. van Praag and Versloot ( 2007 ), extended that first review by systematically reviewing and evaluating the empirical findings of 57 articles published between 1995 and 2007. More precisely, the authors evaluated the various economic contributions of entrepreneurial firms, which have been defined by the authors as either employing fewer than 100 employees, being younger than 7 years or being new entrants into the market, relative to their counterparts. van Praag and Versloot ( 2007 ) thus made the first systematic attempt to distinguish the few new firms which are of economic relevance from the majority of meaningless new firms. Fritsch ( 2013 ), in a non-systematic monograph, exhaustively surveyed and assessed the then available knowledge on how new firms particularly effect regional development over time. Within this review, the author has established the term ‘determinants’ in the field of research on the impact of entrepreneurship and developed first suggestions on which factors may determine the impact of new firms. However, the author has not provided any empirical evidence for the effect of his proposed determinants. In contrast to these three literature reviews, the three most recent reviews also incorporated the latest findings from international studies and on developing countries. However, the three latest reviews all have a narrowly defined research focus. While Block et al. ( 2017 ; systematic literature review of 102 studies published between 2000 and 2015) analysed antecedents, behaviour and consequences of innovative entrepreneurship, Bjørnskov and Foss ( 2016 ; systematic literature review of 28 studies) and Urbano et al. ( 2019a ; systematic literature review of 104 studies published between 1992 and 2016) focused on the relationship between the institutional context, entrepreneurship and economic growth. Accordingly, all the existing reviews are either (1) already outdated, (2) mostly on highly developed countries or (3) focused on specific topics. Furthermore, none of these reviews provided (4) a structured overview on the empirical knowledge on the impact of entrepreneurship on the economy or (5) included research on the social and environmental impact of entrepreneurship.

This paper addresses these five shortcomings through a comprehensive and systematic review of empirical research into the impact of entrepreneurship on economic, Footnote 2 social and environmental welfare. The methodology of the review is based on the current knowledge of systematic reviews (e.g. Fayolle and Wright 2014 ; Fisch and Block 2018 ; Jones and Gatrell 2014 ; Tranfield et al. 2003 ), on narrative synthesis (e.g. Dixon-Woods et al. 2005 ; Jones and Gatrell 2014 ; Popay et al. 2006 ) and on recent examples of best practice (e.g. Jones et al. 2011 ; Urbano et al. 2019a ; van Praag and Versloot 2007 ). Using this approach, this paper aims to contribute to the literature on the impact of entrepreneurship on welfare in three ways. First, it updates and extends the existing literature reviews. More specifically, it follows recent research recommendations (e.g. Block et al. 2017 ; Fritsch 2013 ; Urbano et al. 2019a ) by incorporating the recent empirical stream of research on the impact of entrepreneurship in developing countries and research that goes beyond measures of common economic welfare. In practical terms, this means that this review not only considers measures of economic welfare (e.g. GDP, employment rates, innovative capacity), but also for social welfare (e.g. life expectancy, literacy rates, income inequality), for environmental welfare (e.g. CO 2 emissions, water pollution, soil quality) and for indicators which incorporate all three welfare dimensions (e.g. Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare, Genuine Progress Indicator). Second, this paper, as demanded in previous reviews (Fritsch 2013 ; Urbano et al. 2019a ), aims to provide a descriptive analysis of the factors determining the entrepreneurial impact by critically assessing (a) which determinants of the entrepreneurial impact have (b) what impact on (c) which measures of economic welfare. This paper thus represents the first comprehensive attempt to summarize and structure the empirical knowledge on the determinants of the impact of entrepreneurship. Finally, to encourage future research, this paper indicates shortcomings in the empirical research not only on the impact of entrepreneurship on economic, social and environmental welfare, but also on the described and structured determinants of this impact. It concludes with suggestions for future research avenues to close these research gaps.

To achieve these objectives, this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the methodological approach of the review. Sections 3.1 and 3.2 report the available empirical research into the impact of entrepreneurship on economic, social and environmental welfare. Section 3.3 summarizes the determinants of this impact and Sect. 4 presents a roadmap for future research. Section 5 discusses the limitations of this paper and provides a conclusion.

2 Methodology

In order to clarify not only the macroeconomic impact of entrepreneurship on economic welfare but also the determinants of this impact, this paper provides a broad-ranging systematic, evidence-based literature review including a narrative synthesis. According to Mulrow ( 1994 ), systematic reviews are particularly useful in identifying and evaluating a large volume of evidence published over a long period of time and have been frequently applied in recent state-of-the-art literature reviews (e.g. Li et al. 2020 ; Mochkabadi and Volkmann 2020 ; Urbano et al. 2019a ). The systematic literature review conducted in this paper employs a rather broad empirical definition of entrepreneurship which covers both the entrepreneur, who creates or discovers new businesses (Kirzner 1973 ; Schumpeter 1942 ) and the entrepreneurial firm itself. Entrepreneurship is understood here as new business activity, which includes entrepreneurs in the process of new firm creation as well as recently founded firms. Furthermore, although not necessarily associated with the formation of new firms, self-employed individuals and owner-managers are defined here as entrepreneurs as well. This general definition is consistent with the majority of empirical studies (e.g. Bosma et al. 2011 ; Fritsch and Schindele 2011 ; Mueller et al. 2008 ). The review process comprises three major steps, namely (1) data collection, (2) the selection of relevant studies and (3) data synthesis.

2.1 Data collection

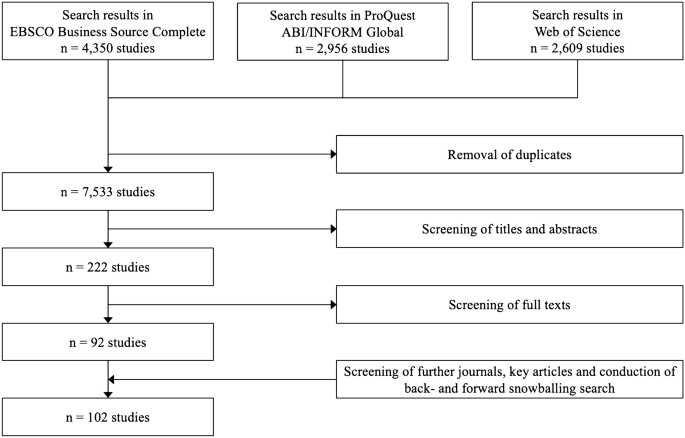

As a first step, to reduce bias and maintain objectivity in all stages of the review, a review panel was set up. The panel consists of the author, a professor and two doctoral students knowledgeable in this field of research. In order to obtain the most relevant terms for the systematic search, the suggestions of Tranfield et al. ( 2003 ) were followed and a number of scoping studies based on combinations of keywords related to the topic were performed. The insights from this initial search phase were used to further develop relevant search terms resulting in the Boolean search string presented in the online appendix. The number of selected search terms was intentionally rather broad to avoid overlooking potentially valuable studies. It included the most common terms and measures of entrepreneurship and of economic, social and environmental welfare. This search string was subsequently used to scan titles, abstracts, and enclosed keywords of studies in the electronic databases EBSCO Business Source Complete, ProQuest ABI/INFORM Global and Web of Science. These databases were selected, because they allow the application of complex search strings and cover an extensive range of scientific journals from a variety of different disciplines. In order to provide a quality threshold, only peer-reviewed journal articles were scanned, since they are considered as validated knowledge (Podsakoff et al. 2005 ; Ordanini et al. 2008 ). Unpublished papers, books, book chapters, conference papers and dissertations were omitted in the initial search. Furthermore, the search was restricted to studies written in English. The main search was conducted in May 2019 and updated once in December 2019. It yielded, after the removal of duplicates, an initial data set of n = 7533 studies.

In addition to the main search, three more steps were conducted to create an exhaustive sample. First, five journals of particular relevance for the discussion were manually searched. Footnote 3 Second, meta-studies and literature reviews on related topics were screened for additional studies. Footnote 4 And finally, based on the guidelines of Wohlin ( 2014 ), an iterative back- and forward snowballing approach was conducted. The whole process of data collection and selection and its results are summarized in Fig. 1 .

Systematic process of data collection and selection

2.2 Data selection and quality assessment

The studies collected during the main search were carefully reviewed to determine whether they were suitable for the objective of this paper. Titles, abstracts and, in doubtful cases, whole studies were checked against the following set of selection criteria.

Studies must analyse the macroeconomic impact of entrepreneurship by applying at least one economic, social or environmental welfare measure on an aggregated regional, national or global level.

Studies must employ definitions of entrepreneurship as discussed in the introduction of Sect. 2 . Studies that solely analysed the impact of small firms, intrapreneurship, corporate-entrepreneurship, institutional entrepreneurship, or entrepreneurial capital were excluded.

Studies must apply adequate quantitative methods to measure the impact of entrepreneurship. Studies that only discuss this matter theoretically, that follow a qualitative approach or that do not go beyond simple correlation techniques were excluded.

Studies must analyse spatial units, as they seem to be considerably better suited to analysing the impact of entrepreneurship (Fritsch 2013 ). Studies that are based on the analysis of industry units were excluded.

Studies must analyse long-term panel data or data on an adequately aggregated level to account for demographic, political and economic events. Studies that analysed single spatial units over a short period of time were excluded.

Due to the broadness of the search string, the main search yielded many studies which solely dealt with the microeconomic performance of new firms or which analyse how the local level of development determines the number of new firms. Studies which were not related to the research questions or did not meet all five selection criteria, were manually removed. This process of selection in the main search led to a total of n = 92 studies. The three additional search steps increased this number by n = 10, resulting in a final data set of n = 102 studies, including two high-quality book chapters which present empirical results of particular relevance to the paper’s objective (namely Stam et al. 2011 ; Verheul and van Stel 2010 ). When comparing the sample size with that of related literature reviews, it appears to be appropriate. Hence, even if the selected sample is not exhaustive, it is very likely to be representative of the relevant literature.

2.3 Data analysis

Given that research in this area employs a variety of measures of entrepreneurship and of economic welfare and is methodologically diverse, it was unfeasible to perform a meta-analysis. Instead, an integrative and evidence-driven narrative synthesis based on the guidelines established by Popay et al. ( 2006 ) was chosen to aggregate, combine and summarise the diverse set of studies. Narrative synthesis is considered particularly useful when, as in this case, research area is characterised by heterogeneous methods, samples, theories, etc. (Fayolle and Wright 2014 ).

Once the final set of studies had been identified, the characteristics and study findings were extracted by carefully reading the methods and results sections. To reduce research bias, a review-specific data-extraction form was employed. The extraction-form is based on the suggestions of Tranfield et al. ( 2003 ) and Higgins and Green ( 2008 ) and contains general information, details about the analysed samples, the applied measures of entrepreneurship and economic welfare, the applied econometric techniques as well as short summaries of the relevant findings and the identified microeconomic impact factors.

3 Results of the literature review

The main results of the literature review regarding the impact of entrepreneurship on economic, social and environmental welfare and the determinants of this impact are presented in Table 5 (see online appendix). The large number of gathered studies on impact of entrepreneurship (n = 102) as well as on its determinants (n = 51) attest to the fact that this field of research has already been studied in great detail. Most of the identified studies were published in high-quality management, economics, social science and environmental science journals. Table 1 illustrates that the main part of the cross-disciplinary scientific discussion, however, took place in the Journals Small Business Economics (24%) and Regional Studies (7%). The number of empirical studies published per year has increased over the last decade, indicating the topicality of the research field and the need for an updated review of the new knowledge.

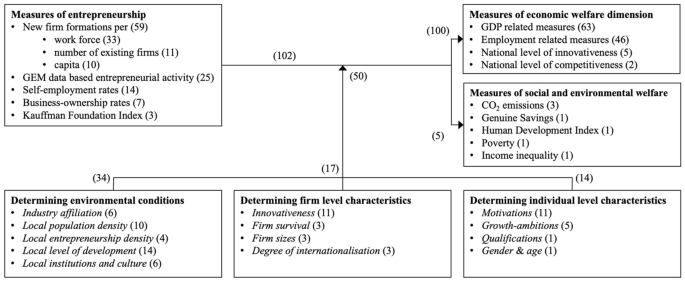

Figure 2 summarizes the statistics of the large amount of data gathered in Table 5 (see appendix) and illustrates the complexity of the research field. The left-hand-side lists the measures of entrepreneurship used in the analysed studies and shows how often they were applied. The most frequently applied measure of entrepreneurship is new firm formations either (a) per work force (labour market approach), (b) per number of existing firms (ecological approach) or (c) per capita. Another frequently applied measure of entrepreneurship is total early-stage entrepreneurial activity (TEA) based on data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (Reynolds et al. 2003 ) or its subgroups: necessity-driven entrepreneurial activity (NEA), opportunity-driven entrepreneurial activity (OEA), innovative entrepreneurial activity (IEA) and high-growth expectation entrepreneurial activity (HEA). Other authors estimated regional entrepreneurship using self-employment or business ownership rates. The Kauffman Foundation Index for entrepreneurial activity is used less frequently, as it is a specific measure of entrepreneurship for US regions.

Overview of applied measures of entrepreneurship and welfare, and analysed determinants. Note : the numbers in brackets represent the numbers of associated empirical studies

Regarding the right-hand-side of Fig. 2 , it is noticeable that the majority of authors analysed the impact of entrepreneurship on economic welfare, primarily on GDP, growth and employment-related measures. Far fewer studies analysed the impact on the economic measures of national competitiveness or innovativeness, e.g. the number of patent applications. In contrast to the clear research focus on economic welfare, only five studies were found which analysed the impact of entrepreneurship on environmental or social welfare. Although many common measures of social and environmental welfare (e.g. crime rates or ecological footprint) were explicitly included in the search string (see online Appendix), no studies could be found that analyse the impact of entrepreneurship on them.

Independent of the measures of entrepreneurship and welfare used, the reviewed studies test their relationship by applying a very heterogenous set of methods. With the availability of more and more cross-sectional data covering longer and high-frequency time-series, authors started to apply new econometric approaches such as pooled and panel data regressions, fixed effect models, and subsequently, dynamic panel data models. Most authors based their analyses on rather straightforward regression techniques.

Sections 3.1 and 3.2 discuss empirical knowledge relating to the impact of entrepreneurship on economic welfare as well as on social and environmental welfare. Section 3.3 deals with the empirical evidence on the factors which determine this impact of entrepreneurship (see the lower part of Fig. 2 ).

3.1 Impact of entrepreneurship on economic welfare

The analysed literature predominantly confirms the results of previous literature reviews and gives empirical evidence that new firm formations have a generally positive effect on regional development and economic performance. The relationship holds for all tested measures of entrepreneurship and is robust across a broad range of spatial and cultural contexts.

The impact does, however, differ over time. Fritsch and Mueller ( 2004 ) studied the time-lag structure of the impact of entrepreneurship by applying an Almon lag model of different polynomial orders in their study of 326 West German regions. Their results revealed that the impact of entrepreneurship follows a typical time-sequence: an S- or wave-shaped pattern which can be structured into three phases. Phase I is defined by a positive immediate increase of employment (direct effects of new capacities). After approximately 1 year, in phase II, this positive short-term impact becomes smaller, insignificant or even negative (displacement effects and market selection). Around year five, this medium-term impact becomes positive again and reaches a peak in year eight (supply-side and spill-over effects). This positive long-term effect of entrepreneurship on employment, which defines phase III, diminishes after a period of 10 years.