- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Research: How Cultural Differences Can Impact Global Teams

- Vasyl Taras,

- Dan Caprar,

- Alfredo Jiménez,

- Fabian Froese

And what managers can do to help their international teams succeed.

Diversity can be both a benefit and a challenge to virtual teams, especially those which are global. The authors unpack their recent research on how diversity works in remote teams, concluding that benefits and drawbacks can be explained by how teams manage the two facets of diversity: personal and contextual. They find that contextual diversity is key to aiding creativity, decision-making, and problem-solving, while personal diversity does not. In their study, teams with higher contextual diversity produced higher-quality consulting reports, and their solutions were more creative and innovative. When it comes to the quality of work, teams that were higher on contextual diversity performed better. Therefore, the potential challenges caused by personal diversity should be anticipated and managed, but the benefits of contextual diversity are likely to outweigh such challenges.

A recent survey of employees from 90 countries found that 89 percent of white-collar workers “at least occasionally” complete projects in global virtual teams (GVTs), where team members are dispersed around the planet and rely on online tools for communication. This is not surprising. In a globalized — not to mention socially distanced — world, online collaboration is indispensable for bringing people together.

- VT Vasyl Taras is an associate professor and the Director of the Master’s or Science in International Business program at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, USA. He is an associate editor of the Journal of International Management and the International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, and a founder of the X-Culture, an international business competition.

- DB Dan Baack is an expert in international marketing. Dan’s work focuses on how the processing of information or cultural models influences international business. He recently published the 2nd edition of his textbook, International Marketing, with Sage Publications. Beyond academic success, he is an active consultant and expert witness. He has testified at the state and federal level regarding marketing ethics.

- DC Dan Caprar is an Associate Professor at the University of Sydney Business School. His research, teaching, and consulting are focused on culture, identity, and leadership. Before completing his MBA and PhD as a Fulbright Scholar at the University of Iowa (USA), Dan worked in a range of consulting and managerial roles in business, NGOs, and government organizations in Romania, the UK, and the US.

- AJ Alfredo Jiménez is Associate Professor at KEDGE Business School (France). His research interests include internationalization, political risk, corruption, culture, and global virtual teams. He is a senior editor at the European Journal of International Management.

- FF Fabian Froese is Chair Professor of Human Resource Management and Asian Business at the University of Göttingen, Germany, and Editor-in-Chief of Asian Business & Management. He obtained a doctorate in International Management from the University of St. Gallen, Switzerland, and another doctorate in Sociology from Waseda University, Japan. His research interests lie in international human resource management and cross-cultural management.

Partner Center

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Hofstede's Six Cultural Dimensions—and Why They Matter

A psychological method for describing the differences between cultures

Cynthia Vinney, PhD is an expert in media psychology and a published scholar whose work has been published in peer-reviewed psychology journals.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/cynthiavinney-ec9442f2aae043bb90b1e7405288563a.jpeg)

d3sign/Moment/Getty Images

Who Is Geert Hofstede?

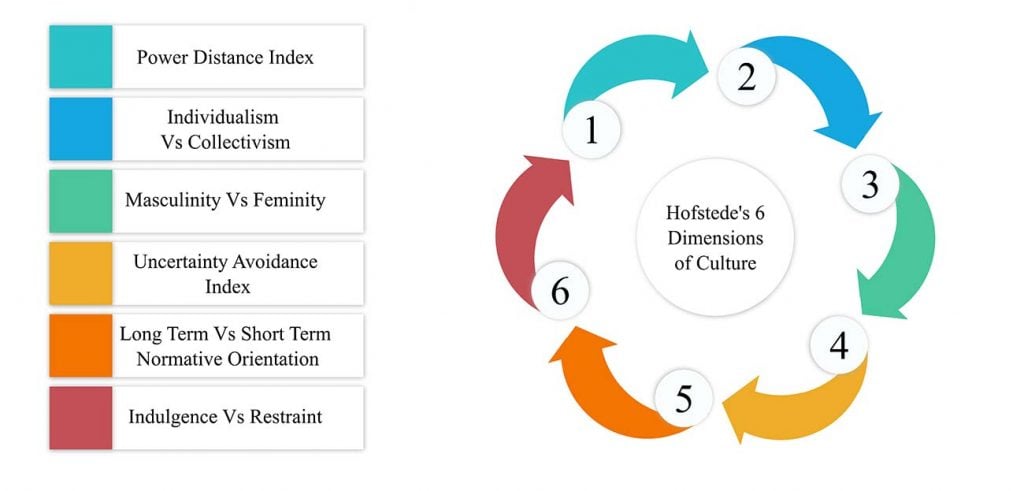

The six cultural dimensions.

- The Significance of Hofstede's Cultural Dimensions

Real-World Applications and Examples

Final thoughts.

The Cultural Dimensions Theory was developed by Geert Hofstede and his colleagues to explain the way different cultures impact the people who live in them. The study started as an examination of Hofstede’s colleagues across IBM’s offices around the world. At the time, he only included four dimensions in his theory, which he published in 1980: Power Distance, Individualism versus Collectivism, Masculinity versus Femininity, and Uncertainty Avoidance.

Then, with the help of Michael Harris Bond, a Canadian social psychologist working in Hong Kong, he added Long-term Orientation versus Short-Term Orientation in the 1980s. And in 2010, through his work with Michael Minkov, a Bulgarian linguist, Indulgence versus Restraint was added.

Let's dive into the six dimensions that make up the theory, their significance in psychology, and take a look at some real world examples.

Geert Hofstede was a social psychologist who was born in 1928 in the Netherlands. World War II, a defining event in his life, began when he was 12. He became an engineer during the years the country struggled to rebuild but soon became fascinated by the human's role in the system, and, therefore, decided to turn his attention to psychology.

He did a PhD in organizational behavior and landed a job at IBM International where he first started conducting his research on the company’s culture in the late 1960s. That led to his first book, 1980’s Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values , which was the beginning of cross-cultural psychology as a serious discipline.

Hofstede was named one of the 20 most influential business thinkers of the 20 th century by the Wall Street Journal and numerous universities have bestowed honorary doctorates on him. He died on February 12, 2020.

Hofstede’s research helps people understand the differences between world cultures along six dimensions. The dimensions are as follows:

Power Distance

This is the degree to which people in a society expect to be equal. Carl Nassar , PhD, LPC, a professional counselor in Denver, CO, had this to say about power distance. “There’s inequality in all cultures, but ask yourself: Are you in a culture where you’ve got a relatively equal distribution of power (a 'low power distance index') or a culture where the power is held by the few and dictated to the many (a 'high power distance index')?”

Low Power Distance cultures see inequality as needed sometimes, but their goal is for relationships to be as equal as possible. In High Power Distance cultures, on the other hand, inequality is the basis of society.

Individualism vs. Collectivism

This is the degree to which people focus on their groups. Individualistic societies, like the United States, strongly value personal achievement and focus on individual needs, whereas in collectivist societies, achievements and decisions are made with the group in mind.

“How focused is the culture on ‘I’ instead of on ‘we?’” says Nassar. “Do individuals look out for themselves (‘it’s every person for themselves’), or do we look out for each other (‘we’ll rise together and we’ll fall together’.)”

Masculinity vs. Femininity

This is the preference for masculine versus feminine traits in a society.

In Hofstede's theory, masculine traits include assertiveness, competitiveness, power, and material success, while feminine traits include nurturing relationships, a good quality of life, and caring for others.

As Nassar observes, “It’s no surprise to learn the [United States] has a low femininity score.” In masculine cultures, differences in gender roles are very dramatic, whereas in feminine cultures, the roles are fairly fluid.

Uncertainty Avoidance

This dimension deals with how much a society can cope with uncertainty of the future.

While every culture must deal with this, cultures with high uncertainty avoidance rely on their set rules and structures about the way things are done to deal with it, whereas those with low uncertainty avoidance are more relaxed.

As Nassar shares, this dimension boils down to, “Are you willing to take risks and deal with the anxiety this causes, or do you prefer to create structures that keep things organized but also reduce risk and opportunity?”

Long-Term vs. Short-Term Orientation

This dimension looks at the extent to which people are willing to forego short-term gains for future rewards, in particular, by emphasizing the virtues of persistence, saving, and thrift. On the opposite end of the spectrum is foregoing future rewards for short-term gains in the past or the present, with an emphasis on immediate gratification and quick results.

“The [United States], like its stock market,” Nassar says, “tends to be all about making it now and letting tomorrow take care of itself.” This makes the [United States] a culture with a short-term orientation.

Indulgence vs. Restraint

This dimension deals with how much your culture satisfies human needs or desires versus how much you hold back on your desires to satisfy societal norms. As Nassar puts it, “How’s your impulse control? Do you tend to go for instant gratification, or do you hold off, in part through social norms, deferring gratification…”

For instance, indulgent cultures tend to focus more on individual well-being and personal freedom, whereas happiness and freedom are not given the same level of importance in restrained cultures.

The Significance of Hofstede's Cultural Dimensions

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimension Theory continues to be the go-to theory for understanding cultures around the globe. As Alyssa Roberts, a practicing psychologist, researcher, and writer at Practical Psychology shares, “Hofstede’s research is so incredibly relevant to this day that it continues to be the basis for assessing how a culture behaves and what kind of cultural adaptation people from different countries need to undergo in order to fully adapt [to a new country].”

Hofstede’s theory can tell you a lot about the different cultures of the world by dividing them along these six dimensions.

The significance of the theory comes down to this: “For most of humanity’s 200,000 year history on this planet, we grew up in villages...,” Nassar says. “But, beginning some 20,000 years ago, and accelerating over the past 500 years, the collective village cultures of the earth were overrun by a consumer culture, a culture that abandoned the security we found with each other and replaced it with the security of individual fiscal wealth.

Hofstede’s dimensions ask the questions: Did a modern culture retain its village values? Did it instead embrace the consumer culture? Or did it walk a middle road?

Roberts has spent a lot of time in different places around the world, and that has driven home the value of Hofstede’s Six Cultural Dimensions. She’s provided examples of each dimension in action here:

- Power Distance can be very different between cultures. “In some Latin American countries, children are taught from a young age to use formal titles when addressing parents, teachers, or other authority figures,” Roberts says. “This ingrained hierarchy contrasts with Nordic cultures where children call teachers by their first names.”

- Individualism vs. Collectivism emerged for Roberts when she worked with immigrant families in the United States. “Those from collectivist societies like China prioritized family cohesion and group goals over individual pursuits. However, their American-born children tended to absorb more individualistic values causing intergenerational conflicts.”

- Masculinity vs. Femininity is seen in whether cultures are more equal or more traditional. As Roberts explains, “I counseled a couple struggling to adjust after moving from egalitarian Sweden to traditional India. The wife felt increasing constraints around appropriate 'feminine' roles contrasting with the overlapping gender roles in Scandinavia.”

- Uncertainty Avoidance is experienced by all cultures but some are more prone to take risks than others. “A Japanese exchange student experiencing intense homesickness and difficulty adapting to ambiguous college social norms [was evidence of this],” observes Roberts. “This reflected the security his uncertainty-avoidant native culture provided around social structures and rules.” And the lack of uncertainty-avoidant social norms he experienced at his new college.”

- Long-Term vs. Short-Term Orientation is the extent to which a culture prepares for the future. Above, Nassar provided one example of short-term orientation: the United States. Roberts provides another examples, “the forward-thinking mindset instilled in many Asian cultures,” which is oriented toward the long-term.

- Indulgence vs. Restraint is experienced in how much people are free to be themselves in public. For Roberts, this “underpinned an Egyptian client’s chronic stress. She found the German culture of strict social restraints and norms around fun-seeking to be at odds with the indulgent festivity permeating Egyptian social life.”

While these dimensions are a popular tool for cross-cultural psychologists and businesses, it’s important to remember that these dimensions are generalizations. Therefore, they may not describe everyone from a specific culture.

Nonetheless, Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Theory has stood the test of time to show the six dimensions that affect the ways people from different cultures interact.

Gerlach P, Eriksson K. Measuring cultural dimensions: External validity and internal consistency of Hofstede’s VSM 2013 scales . Front Psychol . 2021;12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.662604

Michael Harris Bond . Geert Hofstede .

Michael Minkov . Geert Hofstede .

Biography . Geert Hofstede .

Professional Life . Geert Hofstede: An Engineer's Odyssey .

Hofstede's Cultural Dimensions. Power Distance . Center for Global Engagement: James Madison University.

Hofstede's Cultural Dimensions. Individualism and Collectivism . Center for Global Engagement: James Madison University.

Worthy LD, Lavigne T, Romero F. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions . In: Culture and Psychology : MMOER; 2020.

Hofstede's Cultural Dimensions. Uncertainty Avoidance . Center for Global Engagement: James Madison University.

Hofstede's Cultural Dimensions. Indulgence versus Restraint . Center for Global Engagement: James Madison University.

By Cynthia Vinney, PhD Cynthia Vinney, PhD is an expert in media psychology and a published scholar whose work has been published in peer-reviewed psychology journals.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Interviews

- Research Curations

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- Submission Site

- Why Submit?

- About Journal of Consumer Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Cultural Differences (Autumn 2017)

Curator: Sharon Shavitt

Understanding the influence of cultural factors on consumer behavior is crucial because consumption and marketing are global phenomena, and efforts by firms to influence consumers often cross cultural boundaries. This has given rise to a burgeoning literature that examines many implications of cultural variability, including for brand management, consumer well-being, and charitable donations. The papers in this curation address these implications.

Most cross-cultural research investigates distinctions in individualism and collectivism (Hofstede 1984, 2001; Triandis 1995) or independent and interdependent self-construals (Markus and Kitayama 1991). Individualistic cultures, such as those in North America, foster an independent self-construal that casts the self as agentic and distinct from others. Collectivistic cultures, such as those in Asia, foster an interdependent self-construal that views the self as socially embedded and mutually obligated to others. Consumers with an independent self-construal tend to be approach motivated—their self-regulatory goals focus on promotion. In contrast, consumers with an interdependent self-construal tend to be avoidance motivated and focused on prevention ( Aaker and Lee 2001 ), as well as on maintaining adherence to norms through impulse control ( Zhang and Shrum 2009 ) and on attentiveness to social consensus ( Aaker and Maheswaran 1997 ).

Because cross-cultural consumer research is a mature and active subdiscipline, this curation highlights the last few years of research. The first three papers address new motivational and cognitive patterns associated with cultural self-construals. The next two papers address emerging themes regarding cultural views of power and inequality, and ways to leverage brands as cultural icons.

Read the full introduction

Pursuing Attainment versus Maintenance Goals: The Interplay of Self-Construal and Goal Type on Consumer Motivation Haiyang Yang Antonios Stamatogiannakis Amitava Chattopadhyay

This research examines how self-construal (i.e., independent vs. interdependent) and goal type (i.e., attainment vs. maintenance) are conceptually linked and jointly impact consumer behavior. The results of five experiments and one field study involving different operationalizations of self-construal and goal pursuit activities suggest that attainment (maintenance) goals can be more motivating for participants with a more independent (interdependent) self-construal and that differences in salient knowledge about pursuing the goals are one potential mechanism underlying this effect. This interaction effect was found within a single culture, between cultures, when self-construal was experimentally manipulated or measured, and when potential confounding factors like regulatory focus were controlled for. The effect was also found to impact consumer behavior in real life—self-construal, as reflected by the number of social ties consumers had, impacted the likelihood that they opted to reduce versus maintain their bodyweight. Further, after setting their goal, consumers who were more independent exhibited more (less)motivation, as measured by the amount of money they put at stake, when their goal was weight reduction (maintenance). These findings shed light on the relationship between self-construal and goal type, and offer insights, to both consumers and managers, on how to increase motivation for goal pursuit.

Read the Article

Cultivating Optimism: How to Frame Your Future during a Health Challenge Donnel A. Briley Melanie Rudd Jennifer Aaker

Research shows that optimism can positively impact health, but when and why people feel optimistic when confronting health challenges is less clear. Findings from six studies show that the frames people adopt when thinking about health challenges influence their optimism about overcoming those challenges, and that their culture moderates this effect. In cultures where the independent self is highly accessible, individuals adopting an initiator frame (how will I act, regardless of the situations I encounter?) were more optimistic than those adopting a responder frame (how will I react to the situations I encounter?); the converse occurred for individuals from cultures where the interdependent self is highly accessible. Moreover, mediation and moderation evidence revealed that this interactive effect of culture and frame on optimism was driven by people’s ability to easily imagine the recovery process. These effects held for distinct health challenges (cancer, diabetes, flood- related illness, traumatic injury) and across single-country and cross-country samples, and they impacted positive health outcomes and decisions ranging from anticipated energy, physical endurance, and willingness to take on more challenging physical therapy to intentions to get vaccinated, stick to a doctor-recommended diet, and undertake a physically strenuous vacation.

Cultural Differences in Brand Extension Evaluation: The Influence of Analytic versus Holistic Thinking Alokparna Basu Monga Deborah Roedder John

Consumers evaluate brand extensions by judging how well they fit with the parent brand. We examine this process across cultures. We predict that consumers from Eastern cultures, characterized by holistic thinking, perceive higher brand extension fit and evaluate brand extensions more favorably than do Western consumers, characterized by analytic thinking. Study 1 supports the existence of these cultural differences, with study 2 providing support for styles of thinking (analytic vs. holistic) as the drivers of cultural differences in brand extension evaluations.

Accepting Inequality Deters Responsibility: How Power Distance Decreases Charitable Behavior Karen Page Winterich Yinlong Zhang

Could power distance, which is the extent that inequality is expected and accepted, explain why some countries and consumers are more likely to engage in prosocial behavior, including donations of both money and time? This research proposes that higher power distance results in weaker perceptions of responsibility to aid others, which decreases charitable behavior. Both correlational and causal evidence is provided in a series of five studies that examine country-level power distance as well as individual and temporarily salient power distance belief. Consistent with the mediating role of perceived responsibility, results reveal that un- controllable needs and communal relationship norms are boundary conditions that overcome the negative effect of power distance on charitable behavior. These results explain differences in charitable giving across cultures and provide implications for nonprofit organizations soliciting donations.

Extending Culturally Symbolic Brands: A Blessing or a Curse? Carlos J. Torelli Rohini Ahluwalia

Results from four studies uncover a relatively automatic cultural congruency mechanism that can influence evaluations of culturally charged brand extensions, over- riding the impact of perceived fit on extension evaluations. Culturally congruent extensions (i.e., when both the brand and the extension category cue the same cultural schema) were evaluated more favorably than culturally neutral extensions, which in turn were evaluated more favorably than culturally incongruent ones (i.e., cue two different cultural schemas). The effects emerged with both moderate and low fit brand extensions, as well as for narrow and broad brands. However, they only emerged when both the brand and the product were culturally symbolic, likely to automatically activate a cultural schema but did not emerge for brands low in cultural symbolism. The effects were driven by the processing (dis)fluency generated by the simultaneous activation of the same (different) cultural schemas by the product and the brand.

Read all JCR Research Curations

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1537-5277

- Print ISSN 0093-5301

- Copyright © 2024 Journal of Consumer Research Inc.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IResearchNet

Cultural Differences

Cultural differences definition.

Cultural groups can differ widely in their beliefs about what is true, good, and efficient. The study of cultural differences combines perspectives in psychology and anthropology to understand a society’s signature pattern of beliefs, behavior, and social institutions and how these patterns compare and contrast to those of other cultural groups.

Cultural differences appear both between and within societies, for example, between Canadians and Japanese, and within the United States between Anglos and Latinos. Descriptions of cultural differences are made in context to the many similarities shared across human groups. Although a variety of attributes differ between cultures, there are also many similarities that exist across human societies. Moreover, even where there are differences between cultural groups, individual differences mean that not every person within a particular culture will have beliefs or exhibit behaviors that resemble predominant patterns in their society.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code, cultural differences context and focus.

Cultural Differences Background and History

Humans have long been interested in cultural differences. The first written accounts of cultural diversity appear as far back as the 4th century B.C.E.in Herodotus’ description of the unique beliefs and customs among the different cultural groups that traded along the shores of the Black Sea. However, it was not until around the 19th century C.E. that scholars began to conduct systematic studies of unique cultural beliefs and practices, such as Alexis de Tocqueville’s writings about the unique aspects of early American culture and Max Weber’s analysis of how religious ideologies developed in Northern Europe created cultural differences in beliefs about the meaning of work. About 100 years later, the field of cultural anthropology emerged with an exclusive focus on understanding the nature of cultural differences around the world. Today, psychological research has brought new understanding about the nature of cultural differences and similarities by combining an anthropological focus on culture with sophisticated experimental methods developed in social and cognitive psychology. This area of research within social psychology is referred to as cultural psychology.

Before psychologists began to study culture, it was often assumed that knowledge gained from psychological research conducted within one culture applied to all humans. This assumption about the universality of human psychology was challenged when researchers then tried to replicate studies in other cultures and found very different results for a number of important phenomena. For example, psychological experiments showing that people tend to exert less effort when working in a group versus alone showed an opposite pattern in East Asian societies. There, people tend to exert less effort when working alone compared to when working in a group. Further, studies conducted in India, and later in Japan, showed an opposite pattern to earlier research conducted in the United States—that people tend to overestimate the influence of personality and underestimate the influence of situational factors on behavior.

Cultural Differences Evidence

Three broad types of evidence have been used to demonstrate cultural differences. First, in-depth studies of single cultures have found a variety of culturally unique ways people think about and engage in interpersonal relations. For example, within Mexico, interpersonal relations are characterized by a sincere emphasis on proactively creating interpersonal harmony (i.e., simpatfa) even with strangers. In Japan and Korea, people also exhibit a heightened focus on interpersonal harmony. However, unlike Mexicans, the concern for harmony among the Japanese is more focused on relationships with one’s ingroup (e.g., friends, family), and it is sustained through a more passive, “don’t rock the boat” strategy. In the United States, the concern for interpersonal harmony differs for casual, social relationships versus work relationships. While it is common in the United States for individuals to create a pleasant and positive social dynamic across most settings, they show a tendency to attend less to interpersonal relations and overall level of harmony while in work settings. To provide evidence of these different relational styles across cultures, researchers have examined, for example, how members of these cultures convey information that could be embarrassing or disappointing to others. When talking with friends or social acquaintances, Americans and Koreans use indirect, subtle cues to avoid embarrassing others when conveying such bad news. However, when talking with someone in a work setting, Americans believe it is more appropriate to be direct even if the message contains bad news for the listener. In contrast, Koreans believe that at work it is even more important to use subtle communication that will convey the message but also save face for the listener. Thus, cultural differences in attention to interpersonal concerns can be more pronounced in some settings (e.g., work) than in other settings (e.g., party).

A second type of evidence comes from multinational surveys that have measured people’s values in every major continent, across hundreds of societies. In these survey studies, people are asked to rate how much they agree with statements like “It is important to be free to make one’s own decisions” and “People are defined by their connection to their social group.” This type of research shows that cultural groups fluctuate significantly in how much they value individual autonomy versus obligations to follow traditions; equality versus respect for differences in status; competition versus cooperation; and distinctions between ingroups and outgroups.

A third and compelling type of evidence for cultural differences is provided by cross-cultural experiments on the way people perceive and react to their social environment. When experimental studies present individuals from different cultures with the exact same situation, for example, a video of two people talking with each other during a workgroup meeting, very different interpretations and responses can emerge. In many Latin American cultures, people notice and remember how hard the individuals in the video are working and how well or poorly they are getting along interpersonally. In North American cultures, people tend to also notice how hard people are working but notice much less information about the level of interpersonal rapport.

There is evidence that cultural differences are the result of people’s experience living and participating in different sociocultural environments. Bicultural groups, for example, Chinese Canadians or Mexican Americans, often exhibit psychological patterns that are somewhere in between those found in their mother country (e.g., China or Mexico) and those in their new adopted culture (e.g., Canada or the United States). Experimental evidence also shows (in certain domains) significant cultural differences between different regions within a society, for example, between individuals from the northern versus southern United States. In relative terms, an insult to one’s honor is a fleeting annoyance for northerners, but a more serious affront to southerners, and although violence is generally no more tolerated among southerners than northerners, it is more likely to be considered justified when honor is at stake.

Cultural Differences Implications

Cultural differences have implications for virtually all areas of psychology. For example, cultural differences have been found in child-rearing practices (developmental psychology), the range of personality traits in a society (personality psychology), how people process information (cognitive psychology), effective treatments for mental disorders (clinical psychology), teacher-student interactions (educational psychology), motivational incentives important to workers (organizational psychology), and interpersonal styles (social psychology). Research in each of these areas provides knowledge about how cultures can differ and when they are likely to be more similar than different.

The existence of cultural differences has significant implications for people’s daily lives, whether at school, work, or any other setting in which people from diverse cultural backgrounds interact. It is important to recognize that diversity can mean much more than differences in ethnicity, race, or nationality; cultural diversity also includes sometimes subtle, yet important basic differences in the assumptions, beliefs, perceptions, and behavior that people from different cultures use to navigate their social world.

References:

- Markus, H., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224-253.

- Nisbett, R., Peng, K., Choi, I., & Norenzayan, A. (2001). Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychological Review, 108(2), 291-310.

- Sanchez-Burks, J., Nisbett, R., & Ybarra, O. (2000). Cultural styles, relational schemas and prejudice against outgroups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(2), 174-189.

- Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism and collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Theory & Examples

Charlotte Nickerson

Research Assistant at Harvard University

Undergraduate at Harvard University

Charlotte Nickerson is a student at Harvard University obsessed with the intersection of mental health, productivity, and design.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

- Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Theory, developed by Geert Hofstede, is a framework used to understand the differences in culture across countries.

- Hofstede’s initial six key dimensions include power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism-collectivism, masculinity-femininity, and short vs. long-term orientation. Later, researchers added restraint vs. indulgence to this list.

- The extent to which individual countries share key dimensions depends on a number of factors, such as shared language and geographical location.

- Hofstede’s cultural dimensions are widely used to understand etiquette and facilitate communication across cultures in areas ranging from business to diplomacy.

History and Overview

Hofstede’s cultural values or dimensions provide a framework through which sociologists can describe the effects of culture on the values of its members and how these values relate to the behavior of people who live within a culture.

Outside of sociology, Hofstede’s work is also applicable to fields such as cross-cultural psychology, international management, and cross-cultural communication.

The Dutch management researcher Geert Hofstede created the cultural dimensions theory in 1980 (Hofstede, 1980).

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions originate from a large survey that he conducted from the 1960s to 1970s that examined value differences among different divisions of IBM, a multinational computer manufacturing company.

This study encompassed over 100,000 employees from 50 countries across three regions. Hoftstede, using a specific statistical method called factor analysis, initially identified four value dimensions: individualism and collectivism, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, and masculinity and femininity.

Later research from Chinese sociologists identified a fifty-dimension, long-term, or short-term orientation (Bond, 1991).

Finally, a replication of Hofstede’s study, conducted across 93 separate countries, confirmed the existence of the five dimensions and identified a sixth known as indulgence and restraint (Hofstede & Minkov, 2010).

Cultural Dimensions

Geert Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory (1980) examined people’s values in the workplace and created differentiation along three dimensions: small/large power distance, strong/weak uncertainty avoidance, masculinity/femininity, and individualism/collectivism.

Power-Distance Index

The power distance index describes the extent to which the less powerful members of an organization or institution — such as a family — accept and expect that power is distributed unequally.

Although there is a certain degree of inequality in all societies, Hofstede notes that there is relatively more equality in some societies than in others.

Individuals in societies that have a high degree of power distance accept hierarchies where everyone has a place in a ranking without the need for justification.

Meanwhile, societies with low power distance seek to have an equal distribution of power. The implication of this is that cultures endorse and expect relations that are more consultative, democratic, or egalitarian.

In countries with low power distance index values, there tends to be more equality between parents and children, with parents more likely to accept it if children argue or “talk back” to authority.

In low power distance index workplaces, employers and managers are more likely to ask employees for input; in fact, those at the lower ends of the hierarchy expect to be asked for their input (Hofstede, 1980).

Meanwhile, in countries with high power distance, parents may expect children to obey without questioning their authority. Those of higher status may also regularly experience obvious displays of subordination and respect from subordinates.

Superiors and subordinates are unlikely to see each other as equals in the workplace, and employees assume that higher-ups will make decisions without asking them for input.

These major differences in how institutions operate make status more important in high power distance countries than low power distance ones (Hofstede, 1980).

Collectivism vs. Individualism

Individualism and collectivism, respectively, refer to the integration of individuals into groups.

Individualistic societies stress achievement and individual rights, focusing on the needs of oneself and one’s immediate family.

A person’s self-image in this category is defined as “I.”

In contrast, collectivist societies place greater importance on the goals and well-being of the group, with a person’s self-image in this category being more similar to a “We.”

Those from collectivist cultures tend to emphasize relationships and loyalty more than those from individualistic cultures.

They tend to belong to fewer groups but are defined more by their membership in them. Lastly, communication tends to be more direct in individualistic societies but more indirect in collectivistic ones (Hofstede, 1980).

Uncertainty Avoidance Index

The uncertainty avoidance dimension of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions addresses a society’s tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity.

This dimension reflects the extent to which members of a society attempt to cope with their anxiety by minimizing uncertainty. In its most simplified form, uncertainty avoidance refers to how threatening change is to a culture (Hofstede, 1980).

A high uncertainty avoidance index indicates a low tolerance for uncertainty, ambiguity, and risk-taking. Both the institutions and individuals within these societies seek to minimize the unknown through strict rules, regulations, and so forth.

People within these cultures also tend to be more emotional.

In contrast, those in low uncertainty avoidance cultures accept and feel comfortable in unstructured situations or changeable environments and try to have as few rules as possible. This means that people within these cultures tend to be more tolerant of change.

The unknown is more openly accepted, and less strict rules and regulations may ensue.

For example, a student may be more accepting of a teacher saying they do not know the answer to a question in a low uncertainty avoidance culture than in a high uncertainty avoidance one (Hofstede, 1980).

Femininity vs. Masculinity

Femininity vs. masculinity, also known as gender role differentiation, is yet another one of Hofstede’s six dimensions of national culture. This dimension looks at how much a society values traditional masculine and feminine roles.

A masculine society values assertiveness, courage, strength, and competition; a feminine society values cooperation, nurturing, and quality of life (Hofstede, 1980).

A high femininity score indicates that traditionally feminine gender roles are more important in that society; a low femininity score indicates that those roles are less important.

For example, a country with a high femininity score is likely to have better maternity leave policies and more affordable child care.

Meanwhile, a country with a low femininity score is likely to have more women in leadership positions and higher rates of female entrepreneurship (Hofstede, 1980).

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Orientation

The long-term and short-term orientation dimension refers to the degree to which cultures encourage delaying gratification or the material, social, and emotional needs of their members (Hofstede, 1980).

Societies with long-term orientations tend to focus on the future in a way that delays short-term success in favor of success in the long term.

These societies emphasize traits such as persistence, perseverance, thrift, saving, long-term growth, and the capacity for adaptation.

Short-term orientation in a society, in contrast, indicates a focus on the near future, involves delivering short-term success or gratification, and places a stronger emphasis on the present than the future.

The end result of this is an emphasis on quick results and respect for tradition. The values of a short-term society are related to the past and the present and can result in unrestrained spending, often in response to social or ecological pressure (Hofstede, 1980).

Restraint vs. Indulgence

Finally, the restraint and indulgence dimension considers the extent and tendency of a society to fulfill its desires.

That is to say, this dimension is a measure of societal impulse and desire control. High levels of indulgence indicate that society allows relatively free gratification and high levels of bon de vivre.

Meanwhile, restraint indicates that society tends to suppress the gratification of needs and regulate them through social norms.

For example, in a highly indulgent society, people may tend to spend more money on luxuries and enjoy more freedom when it comes to leisure time activities. In a restrained society, people are more likely to save money and focus on practical needs (Hofstede, 2011).

Correlations With Other Country’s Differences

Hofstede’s dimensions have been found to correlate with a variety of other country difference variables, including:

- geographical proximity,

- shared language,

- related historical background,

- similar religious beliefs and practices,

- common philosophical influences,

- and identical political systems (Hofstede, 2011).

For example, countries that share a border tend to have more similarities in culture than those that are further apart.

This is because people who live close to each other are more likely to interact with each other on a regular basis, which leads to a greater understanding and appreciation of each other’s cultures.

Similarly, countries that share a common language tend to have more similarities in culture than those that do not.

Those who speak the same language can communicate more easily with each other, which leads to a greater understanding and appreciation of each other’s cultures (Hofstede, 2011).

Finally, countries that have similar historical backgrounds tend to have more similarities in culture than those that do not.

People who share a common history are more likely to have similar values and beliefs, which leads, it has generally been theorized, to a greater understanding and appreciation of each other’s cultures.

Applications

Cultural difference awareness.

Geert Hofstede shed light on how cultural differences are still significant today in a world that is becoming more and more diverse.

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions can be used to help explain why certain behaviors are more or less common in different cultures.

For example, individualism vs. collectivism can help explain why some cultures place more emphasis on personal achievement than others. Masculinity vs. feminism could help explain why some cultures are more competitive than others.

And long-term vs. short-term orientation can help explain why some cultures focus more on the future than the present (Hofstede, 2011).

International communication and negotiation

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions can also be used to predict how people from different cultures will interact with each other.

For example, if two people from cultures with high levels of power distance meet, they may have difficulty communicating because they have different expectations about who should be in charge (Hofstede, 2011).

In Business

Finally, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions can be used to help businesses adapt their products and marketing to different cultures.

For example, if a company wants to sell its products in a country with a high collectivism score, it may need to design its packaging and advertising to appeal to groups rather than individuals.

Within a business, Hofstede’s framework can also help managers to understand why their employees behave the way they do.

For example, if a manager is having difficulty getting her employees to work together as a team, she may need to take into account that her employees come from cultures with different levels of collectivism (Hofstede, 2011).

Although the cultural value dimensions identified by Hofstede and others are useful ways to think about culture and study cultural psychology, the theory has been chronically questioned and critiqued.

Most of this criticism has been directed at the methodology of Hofstede’s original study.

Orr and Hauser (2008) note Hofstede’s questionnaire was not originally designed to measure culture but workplace satisfaction. Indeed, many of the conclusions are based on a small number of responses.

Although Hofstede administered 117,000 questionnaires, he used the results from 40 countries, only six of which had more than 1000 respondents.

This has led critics to question the representativeness of the original sample.

Furthermore, Hofstede conducted this study using the employees of a multinational corporation, who — especially when the study was conducted in the 1960s and 1970s — were overwhelmingly highly educated, mostly male, and performed so-called “white collar” work (McSweeney, 2002).

Hofstede’s theory has also been criticized for promoting a static view of culture that does not respond to the influences or changes of other cultures.

For example, as Hamden-Turner and Trompenaars (1997) have envisioned, the cultural influence of Western powers such as the United States has likely influenced a tide of individualism in the notoriously collectivist Japanese culture.

Nonetheless, Hofstede’s theory still has a few enduring strengths. As McSweeney (2002) notes, Hofstede’s work has “stimulated a great deal of cross-cultural research and provided a useful framework for the comparative study of cultures” (p. 83).

Additionally, as Orr and Hauser (2008) point out, Hofstede’s dimensions have been found to be correlated with actual behavior in cross-cultural studies, suggesting that it does hold some validity.

All in all, as McSweeney (2002) points out, Hofstede’s theory is a useful starting point for cultural analysis, but there have been many additional and more methodologically rigorous advances made in the last several decades.

Bond, M. H. (1991). Beyond the Chinese face: Insights from psychology . Oxford University Press, USA.

Hampden-Turner, C., & Trompenaars, F. (1997). Response to geert hofstede. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 21 (1), 149.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture and organizations. International studies of management & organization, 10 (4), 15-41.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online readings in psychology and culture, 2 (1), 2307-0919.

Hofstede, G., & Minkov, M. (2010). Long-versus short-term orientation: new perspectives. Asia Pacific Business Review, 16(4), 493-504.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s Consequences (Vol. Sage): Beverly Hills, CA.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the mind . London, England: McGraw-Hill.

McSweeney, B. (2002). The essentials of scholarship: A reply to Geert Hofstede. Human Relations, 55( 11), 1363-1372.

Orr, L. M., & Hauser, W. J. (2008). A re-inquiry of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions: A call for 21st century cross-cultural research. Marketing Management Journal, 18 (2), 1-19.

Further Information

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological review, 98(2), 224.

- Triandis, H. C. (1989). The self and social behavior in differing cultural contexts. Psychological review, 96(3), 506.

- Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological bulletin, 128(1), 3.

- Brewer, M. B., & Chen, Y. R. (2007). Where (who) are collectives in collectivism? Toward conceptual clarification of individualism and collectivism. Psychological review, 114(1), 133.

- Grossmann, I., & Santos, H. (2017). Individualistic culture.

Cultural Difference and Its Effects on User Research Methodologies

- Conference paper

- Cite this conference paper

- Jungjoo Lee 1 ,

- Thu-Trang Tran 1 &

- Kun-Pyo Lee 1

Part of the book series: Lecture Notes in Computer Science ((LNISA,volume 4559))

Included in the following conference series:

- International Conference on Usability and Internationalization

4770 Accesses

4 Citations

Various researches have proved that cultural differences affect the process and results of user research, emphasizing that should cultural attention be given in order to obtain sufficient results. After performing three experiment methods: probe, usability test, and focus group interview in the Netherlands and Korea, we discovered that productivity and effectiveness was poorer in Korea. The differences were found due to the contrary between cultures, strongly indicated by Hofstede’s cultural dimension Individualism vs. Collectivism. In addition, we have proved that the different factors made an impact on user research process and result. Based on the analysis, we compiled guidelines for each of the method when performing in Korea.

Download to read the full chapter text

Chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others.

The Influences of Culture on User Experience

ISO 9241-210 and Culture? – The Impact of Culture on the Standard Usability Engineering Process

Cross-Cultural Web Usability Model

- Cultural difference

- User research methodology

- User participatory study

- User research guidelines

Brown, P., Levinson, S.: Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1987)

Google Scholar

Hall, E.: Beyond Culture. Anchor Books Editions (1989)

Hall, M., et al.: Cultural Differences and Usability Evaluation: Individualistic and Collectivistic Participants Compared. Technical Communication, vol. 51 (2004)

Hofstede, G.: Culture and Organizations: Software of the Mind. McGraw-Hill International, The United Kingdom (1991)

Hofstede, G.: Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations across Nation, 2nd edn. Beverly Hills (2001)

Rijn, H., et al.: Three Factors for Contextmapping in East Asia: Trust, Control and Nunchi (2006)

Sanders, N.: Design for Experiencing: New Tools. In: Proceeding of the First International Conference on Design and Emotion (1999)

Ting-Toomey, S.: Intercultural Conflicts Styles. A Face-negotiation Theory. In: Kim, Y.Y., Gudykunst, W.B. (eds.) Theories in Intercultural Communication, Sage, Thousand Oaks (1998)

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Human-Centered Interaction Design Lab, Department of Industrial Design, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, 373-1 Guseong-dong, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon, 305-701, Republic of Korea

Jungjoo Lee, Thu-Trang Tran & Kun-Pyo Lee

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2007 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Lee, J., Tran, TT., Lee, KP. (2007). Cultural Difference and Its Effects on User Research Methodologies. In: Aykin, N. (eds) Usability and Internationalization. HCI and Culture. UI-HCII 2007. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 4559. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-73287-7_16

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-73287-7_16

Publisher Name : Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN : 978-3-540-73286-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-540-73287-7

eBook Packages : Computer Science Computer Science (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open

- v.7(5); 2019 May

Cultural Competence and Ethnic Diversity in Healthcare

Lakshmi nair.

From the * Albany Medical College, Albany, N.Y.

Oluwaseun A. Adetayo

† Division of Plastic Surgery, Albany Medical Center, Albany, N.Y.

Today’s model of healthcare has persistent challenges with cultural competency, and racial, gender, and ethnic disparities. Health is determined by many factors outside the traditional healthcare setting. These social determinants of health (SDH) include, but are not limited to, education, housing quality, and access to healthy foods. It has been proposed that racial and ethnic minorities have unfavorable SDH that contributes to their lack of access to healthcare. Additionally, African American, Hispanic, and Asian women have been shown to be less likely to proceed with breast reconstructive surgery post-mastectomy compared to Caucasian women. At the healthcare level, there is underrepresentation of cultural, gender, and ethnic diversity during training and in leadership. To serve the needs of a diverse population, it is imperative that the healthcare system take measures to improve cultural competence, as well as racial and ethnic diversity. Cultural competence is the ability to collaborate effectively with individuals from different cultures; and such competence improves health care experiences and outcomes. Measures to improve cultural competence and ethnic diversity will help alleviate healthcare disparities and improve health care outcomes in these patient populations. Efforts must begin early in the pipeline to attract qualified minorities and women to the field. The authors are not advocating for diversity for its own sake at the cost of merit or qualification, but rather, these efforts must evolve not only to attract, but also to retain and promote highly motivated and skilled women and minorities. At the trainee level, measures to educate residents and students through national conferences and their own institutions will help promote culturally appropriate health education to improve cultural competency. Various opportunities exist to improve cultural competency and healthcare diversity at the medical student, resident, attending, management, and leadership levels. In this article, the authors explore and discuss various measures to improve cultural competency as well as ethnic, racial, and gender diversity in healthcare.

By 2050, it is estimated that 50% of the US population will consist of minorities and unfortunately, today’s model of healthcare has been noted to have persistent racial and ethnic discrepancies. 1 Diverse populations require personalized approaches to meet their healthcare needs. Minorities have been shown to have decreased access to preventive care and treatment for chronic conditions which results in increased emergency room visits, graver health outcomes, and increased likelihood of developing cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and mental illness. 2 – 5

This disparity has been prominent in the field of plastic and reconstructive surgery. For example, Sharma et al. explains that there are significant racial disparities in breast reconstruction surgery. Specifically, African American, Hispanic, and Asian women are less likely to proceed with breast reconstructive surgery postmastectomy compared with White women. A study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database found that more African American women compared with White counterparts opted not to have immediate breast reconstruction after mastectomy, many stating they were unable to afford surgery. This discrepancy has been supported by future studies after Medicaid expansion and coverage. 1

Health is determined by many factors outside the traditional healthcare setting. These social determinants of health (SDH) include housing quality, access to healthy food, and education. 6 It has been proposed that racial and ethnic minorities have unfavorable SDH that contributes to their lack of access to healthcare. 6 Differences in healthcare treatment and outcomes among minorities persist even after adjusting for socioeconomic factors. 3 We hypothesize that lack of female and minority representation in the field of plastic surgery contributes to delayed healthcare and quality of outcomes in these populations. To be able to cater to these healthcare needs down the pipeline, it is critical that we begin efforts for attraction and retention of skilled female surgeons and minorities farther up in the pipeline chain. Although women compose half of all medical school graduates, only 14% of plastic surgeons and 32% of plastic surgery residents are women. 7

The senior author (O.A.A.) wrote a response to Drs. Butler, Britt, and Longaker regarding the scarcity of ethnic diversity in plastic surgery in 2010. At that time, as a Black female in plastic and reconstructive surgery, O.A.A. represented a mere 3.7% of plastic and reconstructive surgery residents and fellows. 8 It is astonishing that nearly a decade later we still face nearly identical statistics. It is imperative to prioritize diversity in plastic surgery so that by the next decade, we can make significant strides in narrowing this enormous disparity in representation. The authors are not advocating for diversity for its own sake at the cost of merit or qualification, but rather, that organizations and specialties initiate efforts to attract, retain, and promote highly motivated and skilled women and minorities.

Advocating for women and minorities in plastic surgery is one step in acknowledging and catering to various cultural differences. Culture is defined as a cumulative deposit of knowledge acquired by a group of people over the course of generations. 4 Cultural competence is the ability to collaborate effectually with individuals from different cultures, and such competence can help improve healthcare experience and outcomes. 3 , 4

Studies have identified limited national efforts to incorporate cultural competency in healthcare. 9 In a national study of organizational efforts to reduce physician racial and ethnic disparities, 53% of organizations surveyed had 0–1 activities to reduce disparities out of over 20 possible actions to reduce disparities. Some examples of these disparity-reducing activities include providing educational materials in a different language, providing online resources to educate physicians on cultural competence, and awards at national meetings to recognize efforts to reduce racial disparities. The membership size of the national physician organization surveyed and the presence of a health disparities committee were found to be positively associated with organizations with at least 1 disparity-reducing activity. Primary care organizations were more likely to participate in disparity-reducing activities and may serve as role models for other physician organizations to take initiative. 9

Various opportunities exist to improve cultural competency. One of such measures is via education of residents and students before they transition into attending roles. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has identified the importance of addressing cultural diversity as part of its professionalism competency, and the Alliance of Continuing Medical Education also devoted lectures at its national annual conference to cultural competency. 10 Such measures will help increase awareness in trainees and bridge the gap of competency as they transition from training to practice. Incorporating diversity training and cultural competence exercises at national plastic surgery meetings such as Plastic Surgery: The Meeting and AAPS with CME accreditation is a feasible way to incorporate this training. Additional efforts at the state and national level are also critical for advancing cultural competency, and some of these efforts are also underway. 6 , 10 For instance, the Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health developed “Think Cultural Health,” a resource center that offers users the ability to earn continuing education credits in cultural competency through online case-scenario-based training. 6 In addition, 5 states established legislature requiring or strongly recommending cultural competency training for physicians. 10 These implementation efforts will help in raising awareness to improve cultural competency and diversity in healthcare.

On the industry level, the lack of diversity in healthcare leadership is dramatic, with 98% of senior management in healthcare organizations being White. 4 This disparity in representation is similarly magnified when looking at minority representation in leadership roles within plastic surgery. Only 7% of department chiefs and chairs of plastic surgery are women. Improving representation of women and ethnic minorities in White-male dominated fields like plastic surgery has the potential to improve access to healthcare in minority populations. In fact, female leadership has even been associated with increased effectiveness. 11

Even when individuals from racially or ethnically under-represented populations attain high level executive positions, most earn lower salaries and are overrepresented in management positions serving indigent populations. 12 It is critical to address these gaps and disparities in healthcare. Some measures are being taken to attain culture competency via targeting upper-level executives to identify cultural competency as a high priority. 4 , 12 Others propose targeting cultural competence in healthcare at the root, namely medical education. Some of the problematic themes identified include lack of exposure and insufficient education and teaching curricula regarding diversity; unfortunately, cultural competence is often perceived as a low priority in an overloaded academic curriculum. 13

In the healthcare industry, efforts have been made to achieve cultural competence with the goal of providing culturally congruent care. 4 A review of culturally competent healthcare industry systems identified 5 interventions to improve cultural competence: (1) gear programs to recruit and retain diverse staff members, (2) cultural competency training for healthcare providers, (3) use of interpreter services to ensure individuals from different backgrounds can effectively communicate, (4) culturally appropriate health education materials to inform staff of different cultural backgrounds, and (5) provision of culturally specific healthcare settings. 14 Through increased awareness and by incorporating these interventions, culture competence can be improved in plastic surgery from bedside to the operating room.

Regrettably, there is a lack of literature linking culturally competent education to patient, professional, organizational outcomes. Horvat et al. created a 4-dimensional conceptual framework to assess intervention efficacy: educational content, pedagogical approach, structure of the intervention, and participant characteristics. It is essential that future studies follow methodologic rigor and reproducibility to best document progress. 15

An examination of 119 California hospitals revealed that nonprofit hospitals serve more diverse patient populations, are in more affluent and competitive markets, and exhibit higher cultural competency. It is argued that there will be a market incentive for implementing culturally competent programs as long as cultural competency is linked to better patient experiences. 16 Policymakers and institutions can capitalize on this and incorporate cultural competence practices into metrics for incentive payments. Additionally, enhancing public reporting on patient care and hospital quality will drive competition in the healthcare field and prompt organizations to aim for cultural competence. 16

Striving for ethnic diversity and cultural competency in plastic surgery is necessary to adequately care for an evolving and diverse patient population. It is imperative that plastic surgery departments adopt evidence-based practices to foster cultural competency including promoting recruitment of diverse healthcare-providers, the use of interpreter services, cultural competency training for healthcare team members, and distribution of information on cultural competency to hospital staff members. As population demographics change, plastic surgery departments must also evolve to suit the needs of a diverse array of modern patients.

Published online 16 May 2019.

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

Learn More Psychology

- Psychology Issues

Cultural Differences in Psychology

How cultural differences can affect our perception and behavior..

Permalink Print |

You might assume that a study in psychology, regardless of where it was undertaken, can be applied to our understanding of human nature as a whole - that, for example, the attachments formed between mother and baby are universal and will be the identical regardless of where a person lives.

However, this assumption has been challenged by those studying cross-cultural psychology, a field of research which analyses cultural biases in the way other research is carried out, and the influence of our society on the way we think and behave. Researchers have discovered that subtle differences between cultures mean that the findings of an experiment in the U.S. cannot necessarily be applied to our understanding of human behavior in a different culture, such as Japan, for instance.

In this article, we look at the challenges facing psychologists in producing experiments that accurately understand behavior across different cultures, and some interesting findings of psychological studies into cross-cultural differences.

Defining Culture

To understand psychological differences amongst cultures, we must first define what we refer to as "culture" and how this can differ from simply the "place" in which we live. In psychology, culture refers to a set of ideas and beliefs which give people sense of shared history and can guide our behavior within society. Culture manifests itself in our language, art, daily routines, religion and sense of morality, among other forms, and is passed down from generation to generation.

Of course, within each culture we often see the influence of other cultures, such as that of other European languages on the English vocabulary, along with wide cultural variations within each country. So, whilst cultures and their boundaries remain fluid, in the study of cross-cultural psychology, research often focuses the differences in cultures at national levels (e.g. between the US and Japan).

Individualism vs Collectivism

One of the key distinctions between national cultures, which can influence the choices that people make, is that of individualistic versus collectivist societies:

Individualistic Societies

Individualistic societies focus on needs of the individual person and encourage each person to strive to achieve their own potential, often in competition with, or sometimes to the detriment of, a person's peers. It emphasises the importance of self-reliance and give each individual the freedom to be oneself, nurturing the idea of self expression.

Many countries in the West, such as the US, UK and other Western European countries are widely considered to be individualistic societies.

Collectivistic Societies

In contrast to individualistic societies, collectivistic societies emphasize the importance of cooperation - working for the benefit of the collective - and assume that societies can only improve by a group effort amongst all members of the community.

Collectivistic behavior may see altruistic acts or favors being carried out without the expectation of a reward other than that which benefits society. For example, a person may work extra hours without additional reward to fix a well, knowing that it will help to satisfy their fellow villagers' need for water.

Collectivism is generally found in Eastern cultures - in countries such as Japan - and also in smaller groups such as Kibbutz farming communities in Israel, where each member works towards the town's collective goals.

- Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

Yet, many of these theories ignore the wider, environmental factors which affect an individual's behavior, one of which is the influence of the cultural experiences that a person lives through and which must also affect the behavior of people who interact with them. Is there a reason for culture being looked over in the mission to understand our thoughts and behavior?

Bias in Experiments

The development of psychology as a discipline in the West has inevitably lead to many studies and experiments being carried out in individualistic societies and often more specifically, at universities. Moreover, in 2010, Canadian psychologist Joseph Henrich and his colleagues identified that the participants of such studies tended to be W.E.I.R.D. - Western and Educated, and from Industrialised, Rich and Democratic countries ( Henrich et al, 2010 ). 2 This leads to the question of whether the findings of key psychological studies carry external validity outside not only the experimental situation, but whether they can be generalized to apply outside of the society and culture in which the studies were carried out.

Such criticism of psychology studies from a cross-cultural perspective has lead to researchers attempting to replicate experiments' findings in countries other than their original location. Yet this presents a second problem - is there an inherent cultural bias in the experimental methods used to observe behavior? For example, people in the U.S. have been found to interpret emotions using different facial features to those in other China, for example ( Jack, 2012 ). 3 This casts doubt on whether the same techniques can be reliably used to observe and record emotions in a US study as in an experiment carried out in another culture.

Cultural Differences in Relationships and Attachments

One groundbreaking area of research in psychology was that of interpersonal relationships, and the impact that social interactions as an infant have on a person later in life. Mary Ainsworth developed the Strange Situation test (Ainsworth and Bell, 1970) which built on the work of John Bowlby to demonstrate the different types of attachment to the caregiver that infants experience, including secure, anxious-resistant and anxious-avoidant attachments. 4 Such attachments have been widely recognised and are still used in understanding parent-child relationships today. However, in the Strange Situation test, Ainsworth's subjects were from middle class, Caucasian backgrounds - a demographic which struggles to represent the cultural makeup of the US, still less other countries.

Following numerous studies attempting to replicate Ainsworth's Strange Situation test in non-US cultures, a meta-analysis of the studies revealed that across individualistic and collectivistic cultures, secure attachments were the most common bond formed between parent and child ( Ijendoorn and Kroonenburg, 1988 ), as in the US study. 5 However, in the Western countries studied, the remaining attachments formed were primarily insecure-avoidant - infants showed limited anxiety when the caregiver left them, were relatively unphased by a stranger entering the room and took little comfort from the caregiver returning. By contrast, in Eastern cultures, the remaining attachments were mainly resistant avoidant - the infants became anxious when the caregiver left the room and in the presence of the stranger.

In another study, researchers in Detroit carried out a meta-analysis of studies into the effect that having children can have on couple's relationships. Dillon and Beechler (2010) found that in both individualistic and collectivistic cultures, relationships were reported to be impacted to some degree. However, the negative effect was more significant in individualistic societies. The researchers attributed this difference to the way in which the responsibility for childcare is often shared among different caregivers in Eastern societies, whereas in the West, the mother-child bond may be much stronger as infants tend to be cared for primarily by their mother. 6

Cultural differences in emotions

Relationships are not the only focus of study which have been observed to differ among cultures. As we have seen, the participants of studies in the US and China have been seen to use 'tells' - information gathered from facial expressions - differently when judging a person's emotional state. 2

Cultural differences with respect to emotional intelligence have also been identified in participants in a Japanese study, in which participants were shown cartoons of people displaying varying emotions, surrounded by people who either showed the same or a different emotion.

The researchers found that Japanese participants were more likely to evaluate the emotions of those surrounding the central person when trying to judge their emotion than Western participants did ( Masuda et al, 2008 ). 7 This indicates the influence of a collectivist culture in taking into account the emotions of the whole group, rather than focussing on an individual's emotional state.

Culture and measuring intelligence

Cross-cultural analyses of psychology studies has also had implications for the way levels of intelligence are measured among populations. We might believe that intelligence can be measured objectively, and in the West, the Intelligence Quotient (IQ) test is commonly used to quantify and compare people's intelligence. However, across different cultures, this does not always provide an accurate measurement. One study by Sernberg and Grigorenko (2004) , which took the view of intelligence as being a practical ability to survive, measured Kenyans' ability to identify the correct type of herbal medicine to use for infections - an essential skill in their environment. Researchers compared the participants' ability to their intelligence as measured by tests used to quantify intelligence by Western standards, including those evaluating vocabulary and cognitive skills.

The results of the two types of test - one culturally specific and one Western-orientated - had minimal correlation, showing that intelligence in one culture is not necessarily useful in another. 8

Designing better studies