- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

The Healing Power of Music

Music therapy is increasingly used to help patients cope with stress and promote healing.

By Richard Schiffman

“Focus on the sound of the instrument,” Andrew Rossetti, a licensed music therapist and researcher said as he strummed hypnotic chords on a Spanish-style classical guitar. “Close your eyes. Think of a place where you feel safe and comfortable.”

Music therapy was the last thing that Julia Justo, a graphic artist who immigrated to New York from Argentina, expected when she went to Mount Sinai Beth Israel Union Square Clinic for treatment for cancer in 2016. But it quickly calmed her fears about the radiation therapy she needed to go through, which was causing her severe anxiety.

“I felt the difference right away, I was much more relaxed,” she said.

Ms. Justo, who has been free of cancer for over four years, continued to visit the hospital every week before the onset of the pandemic to work with Mr. Rossetti, whose gentle guitar riffs and visualization exercises helped her deal with ongoing challenges, like getting a good night’s sleep. Nowadays they keep in touch mostly by email.

The healing power of music — lauded by philosophers from Aristotle and Pythagoras to Pete Seeger — is now being validated by medical research. It is used in targeted treatments for asthma, autism, depression and more, including brain disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy and stroke.

Live music has made its way into some surprising venues, including oncology waiting rooms to calm patients as they wait for radiation and chemotherapy. It also greets newborns in some neonatal intensive care units and comforts the dying in hospice.

While musical therapies are rarely stand-alone treatments, they are increasingly used as adjuncts to other forms of medical treatment. They help people cope with their stress and mobilize their body’s own capacity to heal.

“Patients in hospitals are always having things done to them,” Mr. Rossetti explained. “With music therapy, we are giving them resources that they can use to self-regulate, to feel grounded and calmer. We are enabling them to actively participate in their own care.”

Even in the coronavirus pandemic, Mr. Rossetti has continued to perform live music for patients. He says that he’s seen increases in acute anxiety since the onset of the pandemic, making musical interventions, if anything, even more impactful than they were before the crisis.

Mount Sinai has also recently expanded its music therapy program to include work with the medical staff, many of whom are suffering from post-traumatic stress from months of dealing with Covid, with live performances offered during their lunch hour.

It’s not just a mood booster. A growing body of research suggests that music played in a therapeutic setting has measurable medical benefits.

“Those who undergo the therapy seem to need less anxiety medicine, and sometimes surprisingly get along without it,” said Dr. Jerry T. Liu, assistant professor of radiation oncology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

A review of 400 research papers conducted by Daniel J. Levitin at McGill University in 2013 concluded that “listening to music was more effective than prescription drugs in reducing anxiety prior to surgery.”

“Music takes patients to a familiar home base within themselves. It relaxes them without side effects,” said Dr. Manjeet Chadha, the director of radiation oncology at Mount Sinai Downtown in New York.

It can also help people deal with longstanding phobias. Mr. Rossetti remembers one patient who had been pinned under concrete rubble at Ground Zero on 9/11. The woman, who years later was being treated for breast cancer, was terrified by the thermoplastic restraining device placed over her chest during radiation and which reawakened her feelings of being entrapped.

“Daily music therapy helped her to process the trauma and her huge fear of claustrophobia and successfully complete the treatment,” Mr. Rossetti recalled.

Some hospitals have introduced prerecorded programs that patients can listen to with headphones. At Mount Sinai Beth Israel, the music is generally performed live using a wide array of instruments including drums, pianos and flutes, with the performers being careful to maintain appropriate social distance.

“We modify what we play according to the patient’s breath and heart rate,” said Joanne Loewy, the founding director of the hospital’s Louis Armstrong Center for Music & Medicine. “Our goal is to anchor the person, to keep their mind connected to the body as they go through these challenging treatments.”

Dr. Loewy has pioneered techniques that use several unusual instruments like a Gato Box, which simulates the rhythms of the mother’s heartbeat, and an Ocean Disc, which mimics the whooshing sounds in the womb to help premature babies and their parents relax during their stay in noisy neonatal intensive care units.

Dr. Dave Bosanquet, a vascular surgeon at the Royal Gwent Hospital in Newport, Wales, says that music has become much more common in operating rooms in England in recent years with the spread of bluetooth speakers. Prerecorded music not only helps surgical patients relax, he says, it also helps surgeons focus on their task. He recommends classical music, which “evokes mental vigilance” and lacks distracting lyrics, but cautions that it “should only be played during low or average stress procedures” and not during complex operations, which demand a sharper focus.

Music has also been used successfully to support recovery after surgery. A study published in The Lancet in 2015 reported that music reduced postoperative pain and anxiety and lessened the need for anti-anxiety drugs. Curiously, they also found that music was effective even when patients were under general anesthesia.

None of this surprises Edie Elkan, a 75-year-old harpist who argues there are few places in the health care system that would not benefit from the addition of music. The first time she played her instrument in a hospital was for her husband when he was on life support after undergoing emergency surgery.

“The hospital said that I couldn’t go into the room with my harp, but I insisted,” she said. As she played the harp for him, his vital signs, which had been dangerously low, returned to normal. “The hospital staff swung the door open and said, ‘You need to play for everyone.’”

Ms. Elkan took these instructions to heart. After she searched for two years for a hospital that would pay for the program, the Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital in Hamilton, N.J., signed on, allowing her to set up a music school on their premises and play for patients at all stages in their hospitalization.

Ms. Elkan and her students have played for over a hundred thousand patients in 11 hospitals that have hosted them since her organization, Bedside Harp, was started in 2002.

In the months since the pandemic began, the harp players have been serenading patients at the entrance to the hospital, as well as holding special therapeutic sessions for the staff outdoors. They hope to resume playing indoors later this spring.

For some patients being greeted at the hospital door by ethereal harp music can be a shocking experience.

Recently, one woman in her mid-70s turned back questioningly to the driver when she stepped out of the van to a medley of familiar tunes like “Beauty and the Beast” and “Over the Rainbow” being played by a harpist, Susan Rosenstein. “That’s her job,” the driver responded, “to put a smile on your face.”

While Ms. Elkan says that it is hard to scientifically assess the impact — “How do you put a number on the value of someone smiling who has not smiled in six months?”— studies suggest that harp therapy helps calm stress and put both patients and hospital staff members at ease.

Ms. Elkan is quick to point out that she is not doing music therapy, whose practitioners need to complete a five-year course of study during which they are trained in psychology and aspects of medicine.

“Music therapists have specific clinical objectives,” she said. “We work intuitively — there’s no goal but to calm, soothe and give people hope.”

“When we come onto a unit, we remind people to exhale,” Ms. Elkan said. “Everyone is kind of holding their breath, especially in the E.R. and the I.C.U. When we come in, we dial down the stress level several decibels.”

Ms. Elkan’s harp can do more than just soothe emotions, says Ted Taylor, who directs pastoral care at the hospital. It can offer spiritual comfort to people who are at a uniquely vulnerable moment in their lives.

“There is something mysterious that we can’t quantify,” Mr. Taylor, a Quaker, said. “I call it soul medicine. Her harp can touch that deep place that connects all of us as human beings.”

Essay on Music Has the Power to Heal

Students are often asked to write an essay on Music Has the Power to Heal in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Music Has the Power to Heal

The healing power of music.

Music is like a magical potion that can heal our minds. It has the ability to touch our souls, evoke emotions, and even alleviate pain. When we are sad, happy tunes can lift our spirits. Similarly, soothing music can calm us when we are stressed.

Music and Physical Health

Studies have shown that music can help in physical recovery too. It can lower heart rate, blood pressure, and even reduce pain in patients. Music therapy is becoming a popular part of treatment in hospitals.

Music and Mental Well-being

Music can also improve our mental well-being. It can help reduce anxiety and depression, boost mood, and improve focus. It’s a wonderful tool for healing and overall health.

250 Words Essay on Music Has the Power to Heal

Music, an art form that transcends boundaries and cultures, has a profound influence on our emotions and body. It is an omnipresent force, often overlooked for its therapeutic potential. The healing power of music is a topic of increasing interest within the scientific community.

Music’s Impact on the Brain

Music’s healing power is rooted in its direct impact on the brain, stimulating emotional responses and activating neural pathways. Researchers have discovered that music can trigger the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with feelings of pleasure and reward. This reaction can help alleviate symptoms of mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety.

Music Therapy

Music therapy, an emerging field, harnesses the power of music for therapeutic purposes. It has shown promising results in treating a range of conditions, from Alzheimer’s disease to stroke recovery. By engaging patients in singing, rhythm playing, and movement, music therapy can stimulate cognitive functions, improve motor skills, and reduce stress.

Music and Physical Healing

Beyond its psychological effects, music has also been found to aid physical healing. Studies have shown that listening to music can lower blood pressure, decrease heart rate, and reduce stress hormones, contributing to faster physical recovery.

Music’s power to heal is a testament to the intricate connection between art and science. As we continue to unravel the complexities of the human brain, the role of music as a healing tool will likely become even more significant. This understanding can pave the way for innovative therapeutic approaches, blurring the lines between art, science, and medicine.

500 Words Essay on Music Has the Power to Heal

The power of music: a healing agent.

Music, a universal language, transcends geographical boundaries, cultural differences, and socio-economic disparities. It is an art form that evokes deep emotions, stimulates the mind, and has the phenomenal power to heal.

The Science Behind Music and Healing

The healing power of music is not just a subjective experience; it is backed by scientific evidence. Neuroscientists have discovered that listening to music stimulates various parts of the brain, including areas responsible for emotions, cognition, and physical coordination. This stimulation can lead to the release of endorphins, the body’s natural painkillers, promoting a sense of well-being and happiness.

Music therapy, a growing field in healthcare, utilizes this power of music to help patients recover from illnesses and improve their quality of life. It has been found effective in managing stress, improving memory, and alleviating pain in patients with chronic conditions.

Music as a Therapeutic Tool

Music therapy employs a range of interventions, from listening to and performing music to composing songs. These activities are designed to address specific therapeutic goals, such as improving motor skills, enhancing communication, and promoting emotional expression.

For instance, in stroke rehabilitation, rhythm and melody can help retrain the brain and improve motor function. Alzheimer’s patients may regain lost memories when familiar tunes stimulate recall. In mental health settings, music therapy can provide an outlet for expressing feelings that might be difficult to articulate in words.

Music and Emotional Healing

Music also plays a pivotal role in emotional healing. It can serve as a cathartic release, allowing individuals to express their feelings and emotions that might otherwise remain suppressed. This emotional release can alleviate symptoms of depression and anxiety, leading to improved mental health.

Moreover, music can create a sense of connectedness. Group music therapy sessions, for example, can foster a sense of community and belonging, combating feelings of isolation and loneliness.

Music: A Non-Invasive Healing Modality

One of the significant advantages of music as a healing tool is its non-invasive nature. It does not require any medical procedures or medications, making it a safe and accessible option for many people. Moreover, it can be tailored to individual preferences, ensuring a personalized healing experience.

In conclusion, music is a potent tool for healing. Its ability to stimulate the brain, evoke emotions, and connect people makes it an effective therapeutic intervention. As the field of music therapy continues to evolve, the healing power of music is likely to become an increasingly integral part of healthcare. Whether it’s a melody that lifts our spirits or a rhythm that soothes our souls, music indeed has the power to heal.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Importance of Music

- Essay on Say No to Junk Food

- Essay on Effects of Junk Food

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Alzheimer's disease & dementia

- Arthritis & Rheumatism

- Attention deficit disorders

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Biomedical technology

- Diseases, Conditions, Syndromes

- Endocrinology & Metabolism

- Gastroenterology

- Gerontology & Geriatrics

- Health informatics

- Inflammatory disorders

- Medical economics

- Medical research

- Medications

- Neuroscience

- Obstetrics & gynaecology

- Oncology & Cancer

- Ophthalmology

- Overweight & Obesity

- Parkinson's & Movement disorders

- Psychology & Psychiatry

- Radiology & Imaging

- Sleep disorders

- Sports medicine & Kinesiology

- Vaccination

- Breast cancer

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Colon cancer

- Coronary artery disease

- Heart attack

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- Kidney disease

- Lung cancer

- Multiple sclerosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Ovarian cancer

- Post traumatic stress disorder

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Schizophrenia

- Skin cancer

- Type 2 diabetes

- Full List »

share this!

November 15, 2023

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

written by researcher(s)

How music heals us, even when it's sad—new study of musical therapy led by a neuroscientist

by Leigh Riby, The Conversation

When I hear Shania Twain's " You're Still The One ," it takes me back to when I was 15, playing on my Dad's PC. I was tidying up the mess after he had tried to [take his own life]. He'd been listening to her album, and I played it as I tidied up. Whenever I hear the song, I'm taken back—the sadness and anger comes flooding back.

There is a renewed fascination with the memory-stimulating and healing powers of music . This resurgence can primarily be attributed to recent breakthroughs in neuroscientific research, which have substantiated music's therapeutic properties such as emotional regulation and brain re-engagement. This has led to a growing integration of music therapy with conventional mental health treatments.

Such musical interventions have already been shown to help people with cancer , chronic pain and depression . The debilitating consequences of stress, such as elevated blood pressure and muscle tension, can also be alleviated through the power of music .

As both a longtime music fan and neuroscientist, I believe music has a special status among all the arts in terms of the breadth and depth of its impact on people. One critical aspect is its powers of autobiographical memory retrieval —encouraging often highly personal recollections of past experiences. We can all recount an instance where a tune transports us back in time, rekindling recollections and often imbuing them with a range of powerful emotions.

But enhanced recollection can also occur in dementia patients, for whom the transformative impact of music therapy sometimes opens a floodgate of memories—from cherished childhood experiences and the aromas and tastes of a mother's kitchen, to lazy summer afternoons spent with family or the atmosphere and energy of a music festival.

One remarkable example is a widely shared video made by the Asociación Música para Despertar , which is thought to feature the Spanish-Cuban ballerina Martha González Saldaña (though there has been some controversy about her identity). The music of Swan Lake by Tchaikovsky appears to reactivate cherished memories and even motor responses in this former prima ballerina, who is moved to rehearse some of her former dance motions on camera.

In our laboratory at Northumbria University, we aim to harness these recent neuroscience advances to deepen our understanding of the intricate connection between music, the brain and mental well-being. We want to answer specific questions such as why sad or bittersweet music plays a unique therapeutic role for some people, and which parts of the brain it "touches" compared with happier compositions.

Advanced research tools such as high-density electroencephalogram (EEG) monitors enable us to record how the brain regions "talk" to each other in real-time as someone listens to a song or symphony. These regions are stimulated by different aspects of the music, from its emotional content to its melodic structure, its lyrics to its rhythmic patterns.

Of course, everyone's response to music is deeply personal, so our research also necessitates getting our study participants to describe how a particular piece of music makes them feel—including its ability to encourage profound introspection and evoke meaningful memories.

Ludwig van Beethoven once proclaimed: "Music is the one incorporeal entrance into the higher world of knowledge which comprehends mankind, but which mankind cannot comprehend." With the help of neuroscience, we hope to help change that.

A brief history of music therapy

Music's ancient origins predate aspects of language and rational thinking. Its roots can be traced back to the Paleolithic Era more than 10,000 years ago, when early humans used it for communication and emotional expression. Archaeological finds include ancient bone flutes and percussion instruments made from bones and stones, as well as markings noting the most accoustically resonant place within a cave and even paintings depicting musical gatherings.

Music in the subsequent Neolithic Era went through significant development within permanent settlements across the world. Excavations have revealed various musical instruments including harps and complex percussion instruments, highlighting music's growing importance in religious ceremonies and social gatherings during this period—alongside the emergence of rudimentary forms of music notation, evident in clay tablets from ancient Mesopotamia in western Asia.

Ancient Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle both recognized music's central role in the human experience. Plato outlined the power of music as a pleasurable and healing stimulus, stating: "Music is a moral law. It gives soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination." More practically, Aristotle suggested that: "Music has the power of forming the character, and should therefore be introduced into the education of the young."

Throughout history, many cultures have embraced the healing powers of music. Ancient Egyptians incorporated music into their religious ceremonies, considering it a therapeutic force. Native American tribes, such as the Navajo, used music and dance in their healing rituals, relying on drumming and chanting to promote physical and spiritual well-being. In traditional Chinese medicine, specific musical tones and rhythms were believed to balance the body's energy (qi) and enhance health.

During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the Christian church was pivotal in popularizing "music for the masses". Congregational hymn singing allowed worshippers to engage in communal music during church services. This shared musical expression was a powerful medium for religious devotion and teaching, bridging the gap for a largely non-literate population to connect with their faith through melody and lyrics. Communal singing is not only a cultural and religious tradition, but it has also been recognized as a therapeutic experience .

In the 18th and 19th centuries, early investigations into the human nervous system paralleled the emergence of music therapy as a field of study. Pioneers such as American physician Benjamin Rush , a signatory of the US Declaration of Independence in 1776, recognized the therapeutic potential of music to improve mental health.

Soon afterwards, figures such as Samuel Mathews (one of Rush's students) began conducting experiments exploring music's effects on the nervous system , laying the foundation for modern music therapy. This early work provided the springboard for E. Thayer Gaston , known as the "father of music therapy", to promote it as a legitimate discipline in the US. These developments inspired similar endeavors in the UK, where Mary Priestley made significant contributions to the development of music therapy as a respected field.

The insights gained from these early explorations have continued to influence psychologists and neuroscientists ever since—including the late, great neurologist and best-selling author Oliver Sacks, who observed that: "Music can lift us out of depression or move us to tears. It is a remedy, a tonic, orange juice for the ear."

The 'Mozart effect'

Music was my profession, but it was also a special and deeply personal pursuit … Most importantly, it gave me a way to cope with life's challenges, learning to channel my feelings and express them safely. Music taught me how to take my thoughts, both the pleasant and the painful ones, and turn them into something beautiful.

Studying and understanding all the brain mechanisms involved in listening to music, and its effects, requires more than just neuroscientists. Our diverse team includes music experts such as Dimana Kardzhieva (quoted above), who started playing the piano aged five and went on to study at the National School of Music in Sofia, Bulgaria. Now a cognitive psychologist, her combined understanding of music and cognitive processes helps us delve into the complex mechanisms through which music affects (and soothes) our minds. A neuroscientist alone might fall short in this endeavor.

The starting point of our research was the so-called "Mozart effect"—the suggestion that exposure to intricate musical compositions, especially classical pieces, stimulates brain activity and ultimately enhances cognitive abilities . While there have been subsequent mixed findings as to whether the Mozart effect is real , due to the different methods employed by researchers over the years, this work has nonetheless triggered significant advances in our understanding of music's effect on the brain.

In the original 1993 study by Frances Rauscher and colleagues , participants experienced enhancement in spatial reasoning ability after just ten minutes of listening to Mozart's Sonata for Two Pianos in D.

In our 1997 study , which used Beethoven's second symphony and rock guitarist Steve Vai's instrumental track For the Love of God , we found similar direct effects in our listeners—as measured both by EEG activity associated with attention levels and the release of the hormone dopamine (the brain's messenger for feelings of joy, satisfaction and the reinforcement of specific actions). Our research found that classical music in particular enhances attention to how we process the world around us, regardless of one's musical expertise or preferences.

The beauty of EEG methodology lies in its capacity to track brain processes with millisecond accuracy—allowing us to distinguish unconscious neural responses from conscious ones. When we repeatedly showed simple shapes to a person, we found that classical music sped up their early (pre-300 millisecond) processing of these stimuli. Other music did not have the same effect—and nor did our subjects' prior knowledge of, or liking for, classical music. For example, both professional rock and classical musicians who took part in our study improved their automatic, unconscious cognitive processes while listening to classical music.

But we also found indirect effects related to arousal. When people immerse themselves in the music they personally enjoy, they experience a dramatic shift in their alertness and mood. This phenomenon shares similarities with the increased cognitive performance often linked to other enjoyable experiences.

In a further study, we explored the particular influence of " program music "—the term for instrumental music that "carries some extramusical meaning", and which is said to possess a remarkable ability to engage memory, imagination and self-reflection. When our participants listened to Antonio Vivaldi's Four Seasons, they reported experiencing a vivid representation of the changing seasons through the music—including those who were unfamiliar with these concertos. Our study concluded, for example, that:

"Spring—particularly the well-recognized, vibrant, emotive and uplifting first movement—had the ability to enhance mental alertness and brain measures of attention and memory."

What's going on inside our brain?

Music's emotional and therapeutic qualities are highly related to the release of neurochemicals. A number of these are associated with happiness, including oxytocin, serotonin and endorphins. However, dopamine is central to the enhancing properties of music.

It triggers the release of dopamine in regions of the brain devoted to reward and pleasure , generating sensations of joy and euphoria akin to the impact of other pleasurable activities such as eating or having sex. But unlike these activities, which have clear value related to survival and reproduction, the evolutionary advantage of music is less obvious.

Its strong social function is acknowledged as the main factor behind music's development and preservation in human communities. So, this protective quality may explain why it taps into the same neural mechanisms as other pleasurable activities.

The brain's reward system consists of interconnected regions, with the nucleus accumbens serving as its powerhouse. It is situated deep within the subcortical region, and its location hints at its significant involvement in emotion processing, given its proximity to other key regions related to this.

When we engage with music, whether playing or listening, the nucleus accumbens responds to its pleasurable aspects by triggering the release of dopamine. This process, known as the dopamine reward pathway, is critical for experiencing and reinforcing positive emotions such as the feelings of happiness, joy or excitement that music can bring.

We are still learning about the full impact of music on different parts of the brain, as Jonathan Smallwood, professor of psychology at Queen's University, Ontario, explains:

"Music can be complicated to understand from a neuroscience perspective. A piece of music encompasses many domains that are typically studied in isolation—such as auditory function, emotion, language and meaning."

That said, we can see how music's effect on the brain extends beyond mere pleasure. The amygdala , a region of the brain renowned for its involvement in emotion, generates and regulates emotional responses to music, from the heartwarming nostalgia of a familiar melody to the exhilarating excitement of a crescendoing symphony or the spine-tingling fear of an eerie, haunting tune.

Research has also demonstrated that, when stimulated by music, these regions can encourage us to have autobiographical memories that elicit positive self-reflection that makes us feel better—as we saw in the video of former ballerina Martha González Saldaña.

Our own research points to the hippocampus , crucial for memory formation, as the part of the brain that stores music-related memories and associations. Simultaneously, the prefrontal cortex , responsible for higher cognitive functions, closely collaborates with the hippocampus to retrieve these musical memories and assess their autobiographical significance. During music listening, this interplay between the brain's memory and emotion centers creates a powerful and unique experience, elevating music to a distinctive and pleasurable stimulus.

Visual art, like paintings and sculptures, lacks music's temporal and multisensory engagement, diminishing its ability to form strong, lasting emotional-memory connections. Art may evoke emotions and memories but often remains rooted in the moment. Music—perhaps uniquely—forms enduring, emotionally charged memories that can be summoned with the replaying of a particular song years later.

Personal perspectives

Music therapy can change people's lives in profound ways. We have had the privilege of hearing many personal stories and reflections from our study participants, and even our researchers. In some cases, such as the memories of a father's attempted suicide elicited by Shania Twain's You're Still The One, these are profound and deeply personal accounts. They show us the power of music to help regulate emotions, even when the memories it triggers are negative and painful.

In the face of severe physical and emotional challenges, another participant in our study explained how they had felt an unexpected boost to their well-being from listening to a favorite track from their past—despite the apparently negative content of the song's title and lyrics:

"Exercise has been crucial for me post-stroke. In the midst of my rehab workout, feeling low and in pain, an old favorite, What Have I Done To Deserve This? by the Pet Shop Boys, gave me an instant boost. It not only lifted my spirits but sent my heart racing with excitement—I could feel the tingles of motivation coursing through my veins."

Music can serve as a cathartic outlet, a source of empowerment, allowing individuals to process and cope with their emotions while supplying solace and release. One participant described how a little-known tune from 1983 serves as a deliberate mood inducer—a tool to boost their well-being:

"Whenever I'm down or in need of a pick me up, I play Dolce Vita by Ryan Paris . It is like a magic button for generating positive emotions within myself—it always lifts me up in a matter of moments."

As each person has their own tastes and emotional connections with certain types of music, a personalized approach is essential when designing music therapy interventions, to ensure they resonate with individuals deeply. Even personal accounts from our researchers, such as this from Sam Fenwick, have proved fruitful in generating hypotheses for experimental work:

"If I had to pick a single song that really strikes a chord, it would be Alpenglow by Nightwish . This song gives me shivers. I can't help but sing along and every time I do, it brings tears to my eyes. When life is good, it triggers feelings of inner strength and reminds me of nature's beauty. When I feel low, it instills a sense of longing and loneliness, like I am trying to conquer my problems all alone when I could really use some support."

Stimulated by such observations, our latest investigation compares the effects of sad and happy music on people and their brains, in order to better understand the nature of these different emotional experiences. We have found that somber melodies can have particular therapeutic effects, offering listeners a special platform for emotional release and meaningful introspection.

Exploring the effects of happy and sad music

Drawing inspiration from studies on emotionally intense cinematic experiences, we recently published a study highlighting the effects of complex musical compositions, particularly Vivaldi's Four Seasons, on dopamine responses and emotional states. This was designed to help us understand how happy and sad music affects people in different ways.

One major challenge was how to measure our participants' dopamine levels non-invasively. Traditional functional brain imaging has been a common tool to track dopamine in response to music—for example, positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. However, this involves the injection of a radiotracer into the bloodstream, which attaches to dopamine receptors in the brain. Such a process also has limitations in terms of cost and availability.

In the field of psychology and dopamine research, one alternative, non-invasive approach involves studying how often people blink, and how the rate of blinking varies when different music is played.

Blinking is controlled by the basal ganglia , a brain region that regulates dopamine. Dopamine dysregulation in conditions such as Parkinson's disease can affect the regular blink rate. Studies have found that individuals with Parkinson's often exhibit reduced blink rates or increased variability in blink rates , compared with healthy individuals. These findings suggest that blink rate can serve as an indirect proxy indicator of dopamine release or impairment.

While blink rate may not provide the same level of precision as direct neurochemical measurements, it offers a practical and accessible proxy measure that can complement traditional imaging techniques. This alternative approach has shown promise in enhancing our understanding of dopamine's role in various cognitive and behavioral processes.

Our study revealed that the somber Winter movement elicited a particularly strong dopamine response, challenging our preconceived notions and shedding light on the interplay between music and emotions. Arguably you could have predicted a heightened response to the familiar and uplifting Spring concerto , but this was not the case.

Our approach extended beyond dopamine measurement to gain a comprehensive understanding of the effects of sad and happy music. We also used EEG network analysis to study how different regions of the brain communicate and synchronize their activity while listening to different music. For instance, regions associated with the appreciation of music, the triggering of positive emotions and the retrieval of rich personal memories may "talk" to each other. It is like watching a symphony of brain activity unfold, as individuals subjectively experienced a diverse range of musical stimuli.

In parallel, self-reports of subjective experiences gave us insights into the personal impact of each piece of music, including the timeframe of thoughts (past, present, or future), their focus (self or others), their form (images or words), and their emotional content. Categorizing these thoughts and emotions, and analyzing their correlation with brain data, can provide valuable information for future therapeutic interventions.

Our preliminary data reveals that happy music sparks present and future-oriented thoughts, positive emotions, and an outward focus on others. These thoughts were associated with heightened frontal brain activity and reduced posterior brain activity. In contrast, sad tunes caused self-focused reflection on past events, aligning with increased neural activity in brain areas tied to introspection and memory retrieval.

So why does sad music have the power to impact psychological well-being? The immersive experience of somber melodies provides a platform for emotional release and processing. By evoking deep emotions, sad music allows listeners to find solace, introspect, and effectively navigate their emotional states.

This understanding forms the basis for developing future targeted music therapy interventions that cater to people facing difficulties with emotional regulation, rumination and even depression. In other words, even sad music can be a tool for personal growth and reflection.

What music therapy can offer in the future

While not a panacea, music listening offers substantial therapeutic effects, potentially leading to increased adoption of music therapy sessions alongside traditional talk therapy. Integrating technology into music therapy, notably through emerging app-based services, is poised to transform how people access personalized, on-demand therapeutic music interventions, providing a convenient and effective avenue for self-improvement and well-being.

And looking even further ahead, artificial intelligence (AI) integration holds the potential to revolutionize music therapy. AI can dynamically adapt therapy interventions based on a person's evolving emotional responses. Imagine a therapy session that uses AI to select and adjust music in real-time, precisely tailored to the patient's emotional needs, creating a highly personalized and effective therapeutic experience. These innovations are poised to reshape the field of music therapy , unlocking its full therapeutic potential.

In addition, an emerging technology called neurofeedback has shown promise. Neurofeedback involves observing a person's EEG in real-time and teaching them how to regulate and improve their neural patterns. Combining this technology with music therapy could enable people to "map" the musical characteristics that are most beneficial for them, and thus understand how best to help themselves.

In each music therapy session, learning occurs while participants get feedback regarding the status of their brain activity. Optimal brain activity associated with well-being and also specific musical qualities—such as a piece's rhythm, tempo or melody—is learned over time. This innovative approach is being developed in our lab and elsewhere .

As with any form of therapy, recognizing the limitations and individual differences is paramount. However, there are compelling reasons to believe music therapy can lead to new breakthroughs. Recent strides in research methodologies , driven partly by our lab's contributions, have significantly deepened our understanding of how music can facilitate healing.

We are beginning to identify two core elements: emotional regulation , and the powerful link to personal autobiographical memories. Our ongoing research is concentrated on unraveling the intricate interactions between these essential elements and the specific brain regions responsible for the observed effects.

Of course, the impact of music therapy extends beyond these new developments in the neurosciences. The sheer pleasure of listening to music, the emotional connection it fosters, and the comfort it provides are qualities that go beyond what can be solely measured by scientific methods. Music deeply influences our basic emotions and experiences, transcending scientific measurement. It speaks to the core of our human experience, offering impacts that cannot easily be defined or documented.

Or, as one of our study participants so perfectly put it:

"Music is like that reliable friend who never lets me down. When I'm low, it lifts me up with its sweet melody. In chaos, it calms with a soothing rhythm. It's not just in my head; it's a soul-stirring [magic]. Music has no boundaries—one day it will effortlessly pick me up from the bottom, and the next it can enhance every single moment of the activity I'm engaged in."

Explore further

Feedback to editors

New study reveals how teens thrive online: Factors that shape digital success revealed

18 hours ago

New approach for developing cancer vaccines could make immunotherapies more effective in acute myeloid leukemia

May 3, 2024

Drug targeting RNA modifications shows promise for treating neuroblastoma

Researchers discover compounds produced by gut bacteria that can treat inflammation

A common type of fiber may trigger bowel inflammation

People with gas and propane stoves breathe more unhealthy nitrogen dioxide, study finds

Newly discovered mechanism of T-cell control can interfere with cancer immunotherapies

Scientists discover new immunosuppressive mechanism in brain cancer

Birdwatching can help students improve mental health, reduce distress

Doctors describe Texas dairy farm worker's case of bird flu

Related stories.

Focused listening study explores the healing charms of music

Oct 20, 2023

Our favorite bittersweet symphonies may help us deal better with physical pain

Oct 25, 2023

Music-induced emotions can be predicted from brain scans

Dec 28, 2020

Music evokes powerful positive emotions through personal memories

Dec 12, 2018

Imagined music and silence trigger similar brain activity

Aug 2, 2021

Watching music move through the brain

Sep 9, 2019

Recommended for you

Largest quantitative synthesis to date reveals what predicts human behavior and how to change it

Researchers find unexpected link between essential fats and insulin aggregation

Birds overcome brain damage to sing again

Genetics, not lack of oxygen, causes cerebral palsy in quarter of cases: Study

Let us know if there is a problem with our content.

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Medical Xpress in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

Logo Left Content

Logo Right Content

Stanford University School of Medicine blog

Recognition of the power of music in medicine is growing

As a cellist, I have experienced firsthand the restorative powers of music. From middle school through medical school, and as a surgeon and a leader of academic medical centers, playing the cello has always brought me joy and comfort. Its benefits have been particularly important to me during the pandemic, as music has served as a source of rejuvenation and resilience.

Beyond its well-known impacts on emotion and spirit, music also has a profound ability to support physical healing. Music therapy has proven effective in helping patients recover from stroke and brain injury and in managing Alzheimer's and dementia. A 2008 study published in Brain: A Journal of Neurology found that music helped people recovering from a stroke with verbal memory and maintaining focus. It also lessened depression and confusion.

Music is found in every culture, and our ability to create and interpret it is built into our anatomy. The human ear is tuned to the human voice, but its range is much greater. The frequency mothers use to communicate with their babies and the exaggerated tones and rhythms of baby talk are reflected in musical compositions.

For decades, before advances in brain imaging, the medical community saw music therapy's value purely in a support role, to foster relationships, help patients express themselves, promote emotional expression, or improve group sessions. Now, with our growing appreciation of the close link of our mental and physical health, these "softer" benefits are gaining recognition for their true importance.

Therapeutic benefits of music, dance and art

The complex and compelling concoction of melody, harmony, and rhythm activates many parts of the brain, areas that also handle language, memory, perception, cognition, and motor control functions. We use music and dance to treat patients with Parkinson's disease. The activity provides a trio of benefits: physical activity, social interaction, and mental stimulation. The profound impact of dance is the driving force behind the Stanford Neuroscience Health Center hosting a dance class led by a professional dancer specially trained in teaching dance for Parkinson's Disease.

Music therapists working at Stanford Children's Health see daily how their work helps patients -- and their families -- cope with anxiety and stress and manage pain. Yet it may be how the music provides comfort, on good days and bad, and even a measure of hope, that is just as important to healing.

This understanding served as a primary influence of Stanford Hospital 's design. The one-year-old facility -- filled with natural light and original works of art -- recognizes the need to heal the body, mind, and spirit. Multiple studies have shown that art can have positive impacts on blood pressure, anxiety, length of hospital stay, and other outcomes.

As a physician-scientist and a surgeon, my tendency and training send me to hard data, tests, and imaging. But I've learned over my career the importance of empathy and truly listening to understand what patients are feeling and, ultimately, the best course of action for their care.

Arts and humanities in medical education

Science teaches us the biological workings of the human body and the causes of disease, but the humanities help us make sense of illness and suffering, life and death. The arts enable us to more confidently navigate these waters and approach each patient with empathy and compassion. We must always remember that a disease is not the same as the experience of illness, and a patient is more than an ill person.

In the same vein, a doctor is much more than an expert in human anatomy. We have a number of innovative programs integrating the arts and humanities in medical education. Medicine and the Muse , a program within the Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics, benefits our entire Stanford Medicine community of clinicians, researchers, staff, and students by helping to restore perspective and bolster resilience in the face of intense stress.

I have particularly appreciated -- and enjoyed -- another program. Our pandemic-inspired virtual Stuck@Home concert series has allowed us to connect with our colleagues, share in their talents, and express ourselves in ways that would undoubtedly be more difficult during a teleconference. It has helped sustain our community. At a recent edition of this monthly concert series, I played the spiritual "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot." For me, the piece resonates so powerfully of hope, and it was my pleasure to share it with my colleagues.

Now I have a confession to make. I didn't always adore the cello. When I was 11, I wanted to play the trumpet. My parents thought otherwise. They suggested a string instrument. The school district had a cello to rent, and I've been playing ever since.

My parents were right. The cello was the better choice for me. At the time, I didn't realize how momentous that day was nor that I would be playing the cello 50 years later. In fostering in me a deep love and appreciation for music, the cello has been instrumental in creating the leader I am today.

Lloyd Minor , MD, is the Carl and Elizabeth Naumann dean of the Stanford School of Medicine and a professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery. This piece originally appeared on his LinkedIn page .

Image by agsandrew

Related posts

Life After Shelter In Place: Part I

Life After Shelter In Place: Part II

Popular posts.

Is an increase in penile length cause for concern?

Ask Me Anything: Everything to know about allergy season — and more

UW Health recently identified and investigated a security incident regarding select patients’ information. Learn more

- Find a Doctor

- Conditions & Services

- Locations & Clinics

- Patients & Families

- Refer a Patient

- Refill a prescription

- Price transparency

- Obtain medical records

- Clinical Trials

- Order flowers and gifts

- Volunteering

- Send a greeting card

- Make a donation

- Find a class or support group

- Priority OrthoCare

- Emergency & Urgent care

May 22, 2019

The healing power of music

Madison, Wis. — It’s been called many things – the universal language, a great healer, even a reflection of the divine. While there’s little doubt about the power of music, research now shows us just how powerful it can be.

“Across the history of time, music has been used in all cultures for healing and medicine,” said health psychologist Shilagh Mirgain , PhD. “Every culture has found the importance of creating and listening to music. Even Hippocrates believed music was deeply intertwined with the medical arts.”

Scientific evidence suggests that music can have a profound effect on individuals – from helping improve the recovery of motor and cognitive function in stroke patients, reducing symptoms of depression in patients suffering from dementia, even helping patients undergoing surgery to experience less pain and heal faster. And, of course, it can be therapeutic.

“Music therapy is an established form of therapy to help individuals address physical, emotional, cognitive and social needs,” said Mirgain. “Music helps reduce heart rate, lower blood pressure and cortisol in the body. It eases anxiety and can help improve mood."

Music is often in the background just about anywhere we go – whether at a restaurant or the store. But Mirgain offers some tips to help use music intentionally to relax, ease stress and even boost moods:

Be aware of the sound environment

Some restaurants use music as a way of subtly encouraging people to eat faster so there is greater turnover. If you’re looking for a location to have a meeting, or even a personal discussion that could be stressful, keep in mind that noisy environments featuring lively music can actually increase stress and tension.

Use it to boost your energy

On the other hand, when you need energy levels to be up – like when exercising, cleaning or even giving a presentation – upbeat music can give you the lift you need. Consider using music when you’re getting ready in the morning as a way to get your day off on the right beat.

Improve sleep

Listening to classical or relaxing music an hour before bedtime can help create a sense of relaxation and lead to improved sleep.

Calm road rage

Listening to music you enjoy can help you feel less frustrated with traffic and could even make you a safer driver.

Improve your mental game

Playing an instrument can actually help your brain function better. Faster reaction times, better long-term memory, even improved alertness are just a few of the ways playing music can help. Studies have also shown that children who learn to play music do better at math and have improved language skills.

Reduce medical anxiety

Feeling stressed about an upcoming medical procedure? Consider using music to calm those jitters. Put your ear buds in and listening to your favorite tunes while sitting in the waiting room can ease anticipatory anxiety before a medical procedure, such as a dental procedure, MRI or injection. Ask your health care provider if music is available to be played in the room during certain procedures, like a colonoscopy, mammogram or even a cavity filling. Using music in these situations distracts your mind, provides a positive experience and can improve your medical outcome.

March 1, 2015

12 min read

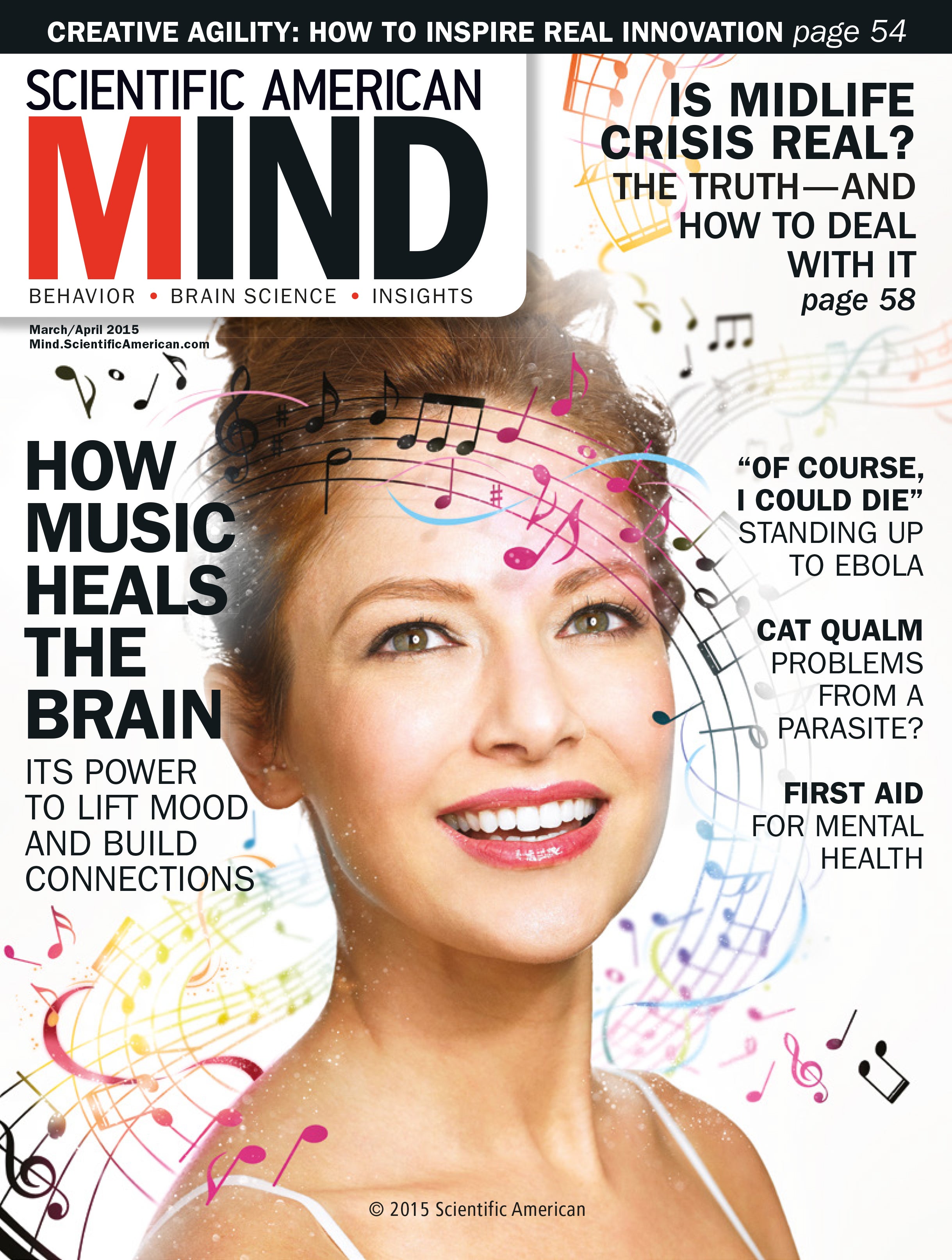

Music Can Heal the Brain

New therapies are using rhythm, beat and melody to help patients recover language, hearing, motion and emotion

By William Forde Thompson & Gottfried Schlaug

One day when Laurel was 11, she began to feel dizzy while playing with her twin sister and some friends in a park on Cape Cod. She sat down, and one of her friends asked her if she was okay. And then Laurel's memory went blank. A sudden blockage in a key blood vessel leading to the brain had caused a massive stroke. Blood could no longer reach regions crucial for language and communication, resulting in permanent damage. Laurel was still able to understand language, but she struggled to vocalize even a single word, and what she managed to say was often garbled or not what she had intended. Except when she sang .

Through a type of treatment called melodic intonation therapy, Laurel learned to draw on undamaged brain regions that moderate the rhythmic and tonal aspects of language, bypassing the speech pathways on the left side of her brain that were destroyed. In other words, she found her way back to language through music.

The therapeutic program that helped Laurel—like the others we focus on in our work as scientists and clinicians—is one of a new class of music-based treatments based directly on the biology of neurological impairment and recovery. These treatments aim to restore functions lost to injury or neurological disorders by enlisting healthy areas of the brain and sometimes even by reviving dysfunctional circuitry. As evidence accumulates about the effectiveness of these techniques, clinicians and therapists from a variety of fields have begun to incorporate them into their practices, most notably music therapists, who are at the intersection of music and health and important mediators of these interventions, as well as speech therapists and physical therapists. And among the beneficiaries are people diagnosed with stroke, autism, tinnitus, Parkinson's disease and dementia.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

As scientists learn more about the effect of music on cognitive and motor functions and mental states, they can tailor these therapies for each disorder, targeting specific brain injuries or dysfunctions. In Laurel's case, the treatments were designed to trigger, over time, the development of alternative neural pathways in healthy parts of the brain that would compensate for the lost pathways in the damaged language centers. But the ultimate aim was to help her recapture as much as she could of the world that had collapsed around her that day in the park.

Music as medicine

Across cultures and throughout history, music listening and music making have played a role in treating disorders of the mind and body. Egyptian frescoes from the fourth millennium b.c. appear to depict the use of music to enhance fertility in women. Shamans in the highland tropical forests of Peru use chanting as their primary tool for healing, and the Ashanti people of Ghana accompany healing ceremonies with drumming.

Much of the power of music-based treatment lies in its ability to meld numerous subtle benefits in a single, engaging package. Music is perhaps unrivaled by any other form of human expression in the range of its defining characteristics, from its melody and rhythm to its emotional and social nature. The treatments that take advantage of these attributes are rewarding, motivating, accessible and inexpensive, and basically free of side effects, too. The attractive quality of music also encourages patients to continue therapy over many weeks and months, improving the chance of lasting gains.

The view that music can be useful in treating neurological impairment gained some scientific heft in a landmark study published in 2008. Psychologist Teppo Särkämö of the University of Helsinki and his team recruited 60 patients who had suffered a stroke in the middle cerebral artery of one hemisphere. They split the patients into three groups: the first participated in daily sessions of music listening, the second listened to audiobooks every day and the third received no auditory treatment. Researchers observed the patients over two months. Those in the group that listened to music exhibited the greatest recovery in verbal memory and attention. And because listening to music appears to improve memory, the hope now is that active music making—singing, moving and synchronizing to a beat—might help restore additional skills, including speech and motor functions in stroke patients.

The singing cure

The variety of music-based treatment that Laurel received springs from a remarkable observation about people who have had a stroke. When a stroke affects areas of the brain that control speech, it can leave patients with a condition known as nonfluent aphasia, or an inability to speak fluently. And yet, as therapists over the years have noted, people with nonfluent aphasia can sometimes sing words they cannot otherwise say.

In the 1970s neurologist Martin Albert and speech pathologists Robert Sparks and Nancy Helm (now Helm-Estabrooks), then at a Veterans Administration hospital in Boston, recognized the therapeutic implications of this ability and developed a treatment called melodic intonation therapy in which singing is a central element. During a typical session, patients will sing words and short phrases set to a simple melody while tapping out each syllable with their left hand. The melody usually involves two notes, perhaps separated by a minor third (such as the first two notes of “Greensleeves”). For example, patients might sing the phrase “How are you?” in a simple up-and-down pattern, with the stressed syllable (“are”) assigned a higher pitch than the others. As the treatment progresses, the phrases get longer and the frequency of the vocalizations increases, perhaps from one syllable per second to two.

Each element of the treatment contributes to fluency by recruiting undamaged areas of the brain. The slow changes in the pitch of the voice engage areas associated with perception in the right hemisphere, which integrates sensory information over a longer interval than the left hemisphere does; as a consequence, it is particularly sensitive to slowly modulated sounds. The rhythmic tapping with the left hand, in turn, invokes a network in the right hemisphere that controls movements associated with the vocal apparatus. Benefits are often evident after even a single treatment session. But when performed intensively over months, melodic intonation therapy also produces long-term gains that appear to arise from changes in neural circuitry—the creation of alternative pathways or the strengthening of rudimentary ones in the brain. In effect, for patients with severe aphasia, singing trains structures and connections in the brain's right hemisphere to assume permanent responsibility for a task usually handled mostly by the left.

This theory has gained support in the past two decades from studies of stroke patients with nonfluent aphasia conducted by researchers around the world. In a study published in September 2014 by one of us (Schlaug) and his group at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, 11 patients received melodic intonation therapy; nine received no treatment. The patients who received therapy were able to string together more than twice as many appropriate words per minute in response to a question. That same group also showed structural changes, assessed through MRI, in a right-hemisphere network associated with vocalization. The laboratory is now conducting studies to compare the benefits of melodic intonation therapy with other forms of therapy for patients with aphasia.

Because melodic intonation therapy seemed to work by engaging the right hemisphere, researchers then surmised that electrical or magnetic stimulation of the region might boost the therapy's power. In two recent studies that we conducted with our collaborators—one in 2011 at Beth Israel Deaconess and Harvard and the other in 2014 at the ARC Center of Excellence in Cognition and Its Disorders in Sydney, Australia—researchers stimulated an area in the right hemisphere called the inferior frontal gyrus, which helps to connect sounds with the oral, facial and vocal movements that produce them. For many participants, combining melodic intonation therapy with noninvasive brain stimulation yielded improvements in speech fluency after only a few sessions.

The benefits of melodic intonation therapy were dramatic for Laurel (who was part of a study led by Schlaug). The stroke had destroyed much of her left hemisphere, including a region crucial for language production known as Broca's area. When she began therapy in 2008, she could not string together more than two or three words, and her speech was often ungrammatical, leaving her frustrated whenever she tried to communicate. Her treatment plan was intensive—an hour and a half a day for up to five days a week, with 75 sessions in all. By the end of the 15-week treatment period, she could speak in sentences of five to eight words, sometimes more. Over the next several years she treated herself at home using the techniques she learned during the sessions. Today, eight years after her stroke, Laurel spends some of her time as a motivational speaker, giving hope and support to fellow stroke survivors. Her speech is not quite perfect but remarkable nonetheless for someone whose stroke damaged so much of her left brain. Evaluation of the long-term benefits of combination therapy is next on researchers' agenda.

Music and motion

Music making can also help stroke survivors living with impaired motor skills. In a study published in 2007 neuropsychologist and music educator Sabine Schneider and neurologist Eckard Altenmueller, both then at the Hannover University of Music, Drama and Media in Germany, asked patients to use their movement-impaired hand to play melodies on the piano or tap out a rhythm on pitch-producing drum pads. Patients who engaged in this intervention, called music-supported training, showed greater improvement in the timing, precision and smoothness of fine motor skills than did patients who relied on conventional therapy. The researchers postulated that the gains resulted from an increase in connections between neurons of the sensorimotor and auditory regions.

Rhythm is the key to treatment of people with Parkinson's, which affects roughly one in 100 older than 60. Parkinson's arises from degeneration of cells in the midbrain that feed dopamine to the basal ganglia, an area involved in the initiation and smoothness of movements. The dopamine shortage in the region results in motor problems ranging from tremors and stiffness to difficulties in timing the movements associated with walking, facial expressions and speech.

Music with a strong beat can allay some of these symptoms by providing an audible rhythmic sequence that people can use to initiate and time their movements. Treatments include so-called rhythmic entrainment, which involves playing a stimulus like a metronome. In neurologist Oliver Sacks's 1973 book Awakenings , musical rhythm sometimes released individuals from their immobility, letting them dance or sing out unexpectedly.

The use of rhythm in motor therapy gained momentum in the 1990s, when musician, music therapist and neuroscientist Michael Thaut of Colorado State University and other researchers around the world demonstrated a technique called rhythmic auditory stimulation, or RAS, for people who had trouble walking, such as stroke and Parkinson's patients. A therapist will first ask patients to walk at a comfortable speed and then to an audible rhythm. Tempos that pushed patients slightly past their comfort zone yielded the greatest improvementsin velocity, cadence and stride length.

Despite these encouraging outcomes, the neural mechanisms that trigger improvements have been difficult to pin down. Imaging work suggests that during rhythmic auditory stimulation, neural control of motor behavior is rerouted around the basal ganglia; instead the brain stem serves as a relay station that sends auditory input to motor networks in the cerebellum, which governs coordination, and to other cortical regions that could help synchronize sound and motion.

Recovered memory

Fewer neurological disorders inspire greater fear than dementia, one of the most common diseases of the elderly. According to some estimates, 44 million people worldwide are living with dementia, a number expectedto reach 135 million by 2050. Alzheimer's disease, a neurodegenerative condition, accounts for more than 60 percent of the cases; multiple strokes can also cause so-called vascular dementia.

Music may be ideally suited to stimulating memory in people with dementia, helping them maintain a sense of self. Because music activates neural areas and pathways in several parts of the brain, the odds are greater that memories associated with music will survive disease. Music also stimulates normal emotional responses even in the face of general cognitive decline. In a 2009 study psychologist Lise Gagnon of the University of Sherbrooke in Quebec and her colleagues asked 12 individuals with Alzheimer's and 12 without it to judge the emotional connotations of various pieces of music. The Alzheimer's participants were just as accurate as the others despite significant impairments in different areas of judgment. Other research suggests that taking part in musical activities throughout life keeps the mind young and may even decrease the risk of developing dementia [see “ Everyone Can Gain from Making Music ”]; the continuous engagement of the parts of the brain that integrate senses and motion with the systems for emotions and rewards might prevent loss of neurons and synapses.

The type of therapy that individual dementia patients receive will vary, from receptive (listening) to active (dancing, singing, clapping). Music that the patient selects is most effective because the choice represents a connection to memory and self. The benefits vary, too, and tend to be short-term. But when the treatment does work, it reduces the feelings of agitation that lead to wandering and vocal outbursts and encourages cooperation and interaction with others. Music therapy can also help patients with dementia sleep better and can enhance their emotional well-being.

These emotional and social benefits are clear in the case of June, an 89-year-old woman from New Hampshire. June has severe, irreversible dementia and is cared for at home by her daughter (who described her mother's circumstances to a clinician in Thompson's lab). Throughout the day, June is mainly nonresponsive and sits with her head hanging low. She cannot talk or walk, and she is incontinent. Yet when her daughter sings to her, June comes alive. She bangs her hands on her legs, smiles widely and begins to laugh. June especially loves Christmas songs and may even blurt out a word or two. When listening to music, she can bang her leg in time with the beat.

Music on the spectrum

Perhaps the most fascinating interplay between music and the brain lies in the case files of people with autism spectrum disorder, a neurodevelopmental syndrome that occurs in 1 to 2 percent of children, most of whom are boys. Hallmarks of autism include impaired social interactions, repetitive behaviors and difficulties in communication. Indeed, up to 30 percent of people with autism cannot make the sounds of speech at all; many have limited vocabulary of any kind, including gesture.

One of the peculiarities of the neurobiology of autism is the overdevelopment of short-range brain connections. As an apparent consequence, children with autism tend to focus intensely on the fine details of sensory experience, such as the varying textures of different fabrics or the precise sound qualities emitted by appliances such as a refrigerator or an air conditioner. And this fascination with sound may account for the many anecdotal reports of children with autism who thoroughly enjoy making and learning music. A disproportionate number of children with autism spectrum disorder are musical savants, with extraordinary abilities in specialized areas, such as absolute pitch.

The positive response to music opens the way to treatments that can help children with autism engage in activities with other people, acquiring social, language and motor skills as they do. Music also activates areas of the brain that relate to social ways of thinking. When we listen to music, we often get a sense of the emotional states of the people who created it and those who are playing it. By encouraging children with autism to imagine these emotions, therapists can help them learn to think about other people and what they might be feeling.

Recently the Music and Neuroimaging Laboratory at Beth Israel Deaconess and Harvard (which Schlaug directs) developed a new technique called auditory-motor mapping training, or AMMT, for children whose autism has left them unable to speak. The treatments have two main components: intonation of words and phrases (changing the melodic pitch of one's voice) and tapping alternately with each hand on pitch-producing drums while singing or speaking words and phrases. In a proof-of-principle study, six completely nonverbal children took part in 40 sessions of this training over eight weeks. By the end, all were able to produce some speech sounds, and some were even able to voice meaningful and appropriate words during tasks that the therapy sessions had not covered. Most important, the children were still able to demonstrate their new skills eight weeks after the training sessions ended.

Quiet, please

Music-based treatments can also train the brain to tune out the phantom strains of tinnitus—the experience of noise or ringing in the ear in the absence of sound that affects roughly 20 percent of adults. Age-related hearing loss, exposure to loud sounds and circulatory system disorders can all bring on the condition, with symptoms ranging from buzzing or hissing in the ears to a continuous tone with a definable pitch. The sensation can cause serious distress and interfere with the ability to concentrate on other sounds and activities. There is no cure.

The past decade has seen a surge in understanding of the neurological basis of the disorder. In one view, cochlear damage (most likely caused by exposure to loud sounds) reduces the transmission of particular sound frequencies to the brain. To compensate for the loss, neuronal activity in the central auditory system changes, creating neural “noise,” perhaps by throwing off the balance between inhibition and excitation in the auditory cortex, leading to the perception of sounds that are not there. Also at play might be dysfunctional feedback to auditory brain regions from the limbic system, which is thought to serve as a noise-cancellation apparatus that identifies and inhibits irrelevant signals.

Music treatment seeks to counteract this dysfunction by inducing changes in the neural circuitry. For those with tonal tinnitus, one treatment involves listening to “notched music,” generated by digitally removing the frequency band that matches the tinnitus frequency. The notching—pioneered and proved effective by neurophysiologist Christo Pantev and his group at the University of Münster in Germany—might help reverse the imbalance in the auditory cortex, strenghtening the inhibition of the frequency band that might be the source of the phantom sound in the first place. Another approach involves playing a series of pitches to patients and then asking them to imitate the sequence vocally. As the patients refine their accuracy, they learn to disregard irrelevant auditory signals and focus on what they want to hear. In time, the stimulus of effortful attention might help the auditory cortex return to its normal physiological state.

For any novel therapy, enthusiasm can sometimes outpace the evidence, and researchers have rightly pointed out that the new music-based treatments must prove their efficacy against the more established therapies. But of all the techniques for addressing neurological disorders, music-based therapies seem unique in their capacity to tap into emotions, to help the brain find lost memories, to let patients resume their place in the world. We are only now beginning to understand the science behind the belief in the power of music to heal.

William Forde Thompson is a professor of psychology at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia, and a chief investigator at the ARC Center of Excellence in Cognition and Its Disorders there.

Gottfried Schlaug is an associate professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and is a leading researcher on plasticity in brain disorders and music-based treatments for neurological impairments.

- ✏️ Work Life

- 🧘 Learn Meditation More From This Category

- 🌺 Live Mindfully More From This Category

- 🌍 Find Meaning More From This Category

- 📲 Get Started

- Find Meaning

Healing Power of Music: How Does Music Affect Our Mental Health?

- Music’s Impact On Our Mental Health

How Do Different Types of Music Impact Our Mood?

A clinical perspective: music therapy.

- How Does Music Help Us Feel Better?

- Playing an Instrument is Like Making a New Friend

Music’s Impact On Our Mental Health

Music is a great part of our lives. Personally, I can’t even imagine a life without music because it brings me such joy and helps me communicate with myself in a totally different way. Let’s take a deeper look at how music positively impacts our mental health.

Let me start with the most known benefit of music: stress reduction. Research has shown that music has a positive impact on our autonomic nervous system, helping us manage stress and respond more constructively when in moments of stress. We know that there will be stressors present in our lives pretty much all the time. So, one thing we can do is try to understand these stressful situations so that we can learn to live with them rather than trying to eliminate them entirely. And this is where music can play a very important role. Listening to music can help us organize our thoughts and approach our problems with a balanced perspective. I find music very valuable because it’s often widely-accessible, making it easier to experience almost anywhere.

So many of us have had that moment when we put on our headphones and get lost in the music, alone with ourselves in a moment of reverie. But music can be a very powerful social tool as well, giving us many cues. For example, imagine that you’re invited to a social gathering. You enter the room full of people and begin to notice the music playing in the background. That music can give you an idea about the atmosphere even before we encounter people there. We can begin to understand whether this is a more dance-centered event, let’s say, or one wherein the music is meant to convey a vibe rather than be the focus. Going to a concert of our favorite singer and singing the same song together with thousands of people can be a very powerful feeling, right? Music can help us feel part of a community.

Additionally, music can help to motivate us. Many of us listen to music when we’re exercising and there’s a reason for that. Music can increase our performance and motivation in activities like training, running, etc. It can also help us use our time more efficiently. Maybe that means you say to yourself, “I’ll walk until the chorus,” or “I’ll row until the end of this song,” as a way to regulate your exercise using music.

Music impacts almost every part of our lives even including our quality of sleep . One study shows that a group of students who listened to classical music for 45 minutes before going to bed had better sleep quality compared to the group who didn’t listen to music.