Search form

- Find Stories

- For Journalists

Image credit: Getty Images

The power of language: How words shape people, culture

Speaking, writing and reading are integral to everyday life, where language is the primary tool for expression and communication. Studying how people use language – what words and phrases they unconsciously choose and combine – can help us better understand ourselves and why we behave the way we do.

Linguistics scholars seek to determine what is unique and universal about the language we use, how it is acquired and the ways it changes over time. They consider language as a cultural, social and psychological phenomenon.

“Understanding why and how languages differ tells about the range of what is human,” said Dan Jurafsky , the Jackson Eli Reynolds Professor in Humanities and chair of the Department of Linguistics in the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford . “Discovering what’s universal about languages can help us understand the core of our humanity.”

The stories below represent some of the ways linguists have investigated many aspects of language, including its semantics and syntax, phonetics and phonology, and its social, psychological and computational aspects.

Understanding stereotypes

Stanford linguists and psychologists study how language is interpreted by people. Even the slightest differences in language use can correspond with biased beliefs of the speakers, according to research.

One study showed that a relatively harmless sentence, such as “girls are as good as boys at math,” can subtly perpetuate sexist stereotypes. Because of the statement’s grammatical structure, it implies that being good at math is more common or natural for boys than girls, the researchers said.

Language can play a big role in how we and others perceive the world, and linguists work to discover what words and phrases can influence us, unknowingly.

How well-meaning statements can spread stereotypes unintentionally

New Stanford research shows that sentences that frame one gender as the standard for the other can unintentionally perpetuate biases.

Algorithms reveal changes in stereotypes

New Stanford research shows that, over the past century, linguistic changes in gender and ethnic stereotypes correlated with major social movements and demographic changes in the U.S. Census data.

Exploring what an interruption is in conversation

Stanford doctoral candidate Katherine Hilton found that people perceive interruptions in conversation differently, and those perceptions differ depending on the listener’s own conversational style as well as gender.

Cops speak less respectfully to black community members

Professors Jennifer Eberhardt and Dan Jurafsky, along with other Stanford researchers, detected racial disparities in police officers’ speech after analyzing more than 100 hours of body camera footage from Oakland Police.

How other languages inform our own

People speak roughly 7,000 languages worldwide. Although there is a lot in common among languages, each one is unique, both in its structure and in the way it reflects the culture of the people who speak it.

Jurafsky said it’s important to study languages other than our own and how they develop over time because it can help scholars understand what lies at the foundation of humans’ unique way of communicating with one another.

“All this research can help us discover what it means to be human,” Jurafsky said.

Stanford PhD student documents indigenous language of Papua New Guinea

Fifth-year PhD student Kate Lindsey recently returned to the United States after a year of documenting an obscure language indigenous to the South Pacific nation.

Students explore Esperanto across Europe

In a research project spanning eight countries, two Stanford students search for Esperanto, a constructed language, against the backdrop of European populism.

Chris Manning: How computers are learning to understand language

A computer scientist discusses the evolution of computational linguistics and where it’s headed next.

Stanford research explores novel perspectives on the evolution of Spanish

Using digital tools and literature to explore the evolution of the Spanish language, Stanford researcher Cuauhtémoc García-García reveals a new historical perspective on linguistic changes in Latin America and Spain.

Language as a lens into behavior

Linguists analyze how certain speech patterns correspond to particular behaviors, including how language can impact people’s buying decisions or influence their social media use.

For example, in one research paper, a group of Stanford researchers examined the differences in how Republicans and Democrats express themselves online to better understand how a polarization of beliefs can occur on social media.

“We live in a very polarized time,” Jurafsky said. “Understanding what different groups of people say and why is the first step in determining how we can help bring people together.”

Analyzing the tweets of Republicans and Democrats

New research by Dora Demszky and colleagues examined how Republicans and Democrats express themselves online in an attempt to understand how polarization of beliefs occurs on social media.

Examining bilingual behavior of children at Texas preschool

A Stanford senior studied a group of bilingual children at a Spanish immersion preschool in Texas to understand how they distinguished between their two languages.

Predicting sales of online products from advertising language

Stanford linguist Dan Jurafsky and colleagues have found that products in Japan sell better if their advertising includes polite language and words that invoke cultural traditions or authority.

Language can help the elderly cope with the challenges of aging, says Stanford professor

By examining conversations of elderly Japanese women, linguist Yoshiko Matsumoto uncovers language techniques that help people move past traumatic events and regain a sense of normalcy.

Relationship Between Language and Culture Essay

Introduction, what is culture, relationship between language and culture, role of language in cultural diversity, reference list.

How does culture influence language? An essay isn’t enough to answer this question in detail. The purpose of the paper is to clearly highlight the issue of intercultural communication with reference to language and identity.

Language and culture are intertwined. One cannot define or identify cultural orientations without citing variations in how we speak and write. Thus, to explore the relationship between language and culture, this essay will start by defining the terms separately.

Culture describes variations in values, beliefs, as well as differences in the way people behave (DeVito 2007). Culture encompasses everything that a social group develops or produces.

Element of culture are not genetically transmitted and as such, they have to be passed down from one generation the next through communication. This explains why it is easy to adopt a certain language depending on the shared beliefs, attitudes and values.

The existence of different cultures can be explained using the cultural relativism approach which stipulates that although cultures tend to vary, none is superior to the other (DeVito 2007).

Learning of cultural values can be done through enculturation whereby individuals learn the culture of their birth. Alternatively, one can be acculturated into a culture that is divergent from their basic culture (DeVito 2007).

Language is the verbal channel of communication by articulating words that an individual is conversant with. This is aimed at relaying information. In other words, it is the expression of one’s culture verbally (Jandt 2009).

Language is the first element that helps an individual to distinguish the cultural orientations of individuals. Through language, we are able to differentiate between for example, a Chinese national and a Briton. The main functions of language are generally for information purposes and for the establishment of relationships.

Different cultures perceive the use of language differently. Whereas an American regards it as a useful communication tool, a Chinese will use their language to relay their feelings and to establish relationships.

It is through such variances of language that different cultures have placed on the usage of their language show the link between the two study variables (Jandt 2009).

Intercultural communication refers to communication between people from different cultural backgrounds. Due to the differences in cultures, there is a high probability that a message will be misunderstood and distorted.

Difference in languages leads to challenges in the interpretation of for example, politeness, acts of speech and interaction management. Normally, differences in languages lead to impediments in understanding. This is due to the difference in perception in as far as values are concerned.

Language shapes our lines of thought and as such, it is the core element that shapes how people perceive the world. The way people communicate is largely due to their cultures of origin. Language increases the rate of ethnocentrism in individuals thus furthering their self-centeredness in culture.

As a result, they are less responsive to the different means of communication that are not similar to their own values and beliefs (McGregor eta al 2007).

Language further heightens the aspect of accelerating cultural differences as it openly showcases the variations in communication. In turn, this view tends to impede negatively on intercultural efforts, thereby having a negative impact on the communication between individuals of different cultural orientations.

There is need for individuals to evaluate the usage of language in order to effectively interpret the shared meanings that are meant to be communicated. It is important therefore that individuals from a multi cultural context look at each other beyond their differences in order to enable effective communication.

DeVito, J A. (2006) Human communication the basic course, 10 th edition. Boston, Mass: Pearson / Allyn and Bacon.

Jandt, F E. (2007) An introduction to intercultural communication: identities in global community . Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.

Mohan, T, McGregor, M T, Saunders, H & Archee, S. (2008) Communicating as a professional . Sydney, Australia: Cengage Learning.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 29). Relationship Between Language and Culture Essay. https://ivypanda.com/essays/relationship-between-language-and-culture/

"Relationship Between Language and Culture Essay." IvyPanda , 29 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/relationship-between-language-and-culture/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Relationship Between Language and Culture Essay'. 29 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Relationship Between Language and Culture Essay." October 29, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/relationship-between-language-and-culture/.

1. IvyPanda . "Relationship Between Language and Culture Essay." October 29, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/relationship-between-language-and-culture/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Relationship Between Language and Culture Essay." October 29, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/relationship-between-language-and-culture/.

- Britons and Their National and Factual Identity

- Cultural Issues in Walker's “The Color Purple”

- Hillary Clinton: Furthering Political Agenda Through Feminism

- Culture and Communication

- Gender and Politeness

- Politeness Strategies Between Native and Non-native Speakers inthe Context of Brown & Levinson Politeness Theory

- The Concept of Politeness in the Cross-Cultural Communication

- Hmong Americans and Traditional Practices of Healing

- Foolishness: Psychological Perspective

- Relationship Between Ethnocentrism and Intercultural Communication

- Appropriation of Black Culture Life by Whites

- Cultural Differences: Individualism vs. Collectivism

- Americanization of Russia and its Impact on Young Generation

- Smoking Culture in Society

- The Main Distinctions of Popular Culture and Its Growth

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3.4 Language, Society, and Culture

Learning objectives.

- Discuss some of the social norms that guide conversational interaction.

- Identify some of the ways in which language varies based on cultural context.

- Explain the role that accommodation and code-switching play in communication.

- Discuss cultural bias in relation to specific cultural identities.

Society and culture influence the words that we speak, and the words that we speak influence society and culture. Such a cyclical relationship can be difficult to understand, but many of the examples throughout this chapter and examples from our own lives help illustrate this point. One of the best ways to learn about society, culture, and language is to seek out opportunities to go beyond our typical comfort zones. Studying abroad, for example, brings many challenges that can turn into valuable lessons. The following example of such a lesson comes from my friend who studied abroad in Vienna, Austria.

Although English used to employ formal ( thou , thee ) and informal pronouns ( you ), today you can be used when speaking to a professor, a parent, or a casual acquaintance. Other languages still have social norms and rules about who is to be referred to informally and formally. My friend, as was typical in the German language, referred to his professor with the formal pronoun Sie but used the informal pronoun Du with his fellow students since they were peers. When the professor invited some of the American exchange students to dinner, they didn’t know they were about to participate in a cultural ritual that would change the way they spoke to their professor from that night on. Their professor informed them that they were going to duzen , which meant they were going to now be able to refer to her with the informal pronoun—an honor and sign of closeness for the American students. As they went around the table, each student introduced himself or herself to the professor using the formal pronoun, locked arms with her and drank (similar to the champagne toast ritual at some wedding ceremonies), and reintroduced himself or herself using the informal pronoun. For the rest of the semester, the American students still respectfully referred to the professor with her title, which translated to “Mrs. Doctor,” but used informal pronouns, even in class, while the other students not included in the ceremony had to continue using the formal. Given that we do not use formal and informal pronouns in English anymore, there is no equivalent ritual to the German duzen , but as we will learn next, there are many rituals in English that may be just as foreign to someone else.

Language and Social Context

We arrive at meaning through conversational interaction, which follows many social norms and rules. As we’ve already learned, rules are explicitly stated conventions (“Look at me when I’m talking to you.”) and norms are implicit (saying you’ve got to leave before you actually do to politely initiate the end to a conversation). To help conversations function meaningfully, we have learned social norms and internalized them to such an extent that we do not often consciously enact them. Instead, we rely on routines and roles (as determined by social forces) to help us proceed with verbal interaction, which also helps determine how a conversation will unfold. Our various social roles influence meaning and how we speak. For example, a person may say, “As a longtime member of this community…” or “As a first-generation college student…” Such statements cue others into the personal and social context from which we are speaking, which helps them better interpret our meaning.

One social norm that structures our communication is turn taking. People need to feel like they are contributing something to an interaction, so turn taking is a central part of how conversations play out (Crystal, 2005). Although we sometimes talk at the same time as others or interrupt them, there are numerous verbal and nonverbal cues, almost like a dance, that are exchanged between speakers that let people know when their turn will begin or end. Conversations do not always neatly progress from beginning to end with shared understanding along the way. There is a back and forth that is often verbally managed through rephrasing (“Let me try that again,”) and clarification (“Does that make sense?”) (Crystal, 2005)

We also have certain units of speech that facilitate turn taking. Adjacency pairs are related communication structures that come one after the other (adjacent to each other) in an interaction (Crystal, 2005). For example, questions are followed by answers, greetings are followed by responses, compliments are followed by a thank you, and informative comments are followed by an acknowledgment. These are the skeletal components that make up our verbal interactions, and they are largely social in that they facilitate our interactions. When these sequences don’t work out, confusion, miscommunication, or frustration may result, as you can see in the following sequences:

Travis: “How are you?”

Wanda: “Did someone tell you I’m sick?”

Darrell: “I just wanted to let you know the meeting has been moved to three o’clock.”

Leigh: “I had cake for breakfast this morning.”

Some conversational elements are highly scripted or ritualized, especially the beginning and end of an exchange and topic changes (Crystal, 2005). Conversations often begin with a standard greeting and then proceed to “safe” exchanges about things in the immediate field of experience of the communicators (a comment on the weather or noting something going on in the scene). At this point, once the ice is broken, people can move on to other more content-specific exchanges. Once conversing, before we can initiate a topic change, it is a social norm that we let the current topic being discussed play itself out or continue until the person who introduced the topic seems satisfied. We then usually try to find a relevant tie-in or segue that acknowledges the previous topic, in turn acknowledging the speaker, before actually moving on. Changing the topic without following such social conventions might indicate to the other person that you were not listening or are simply rude.

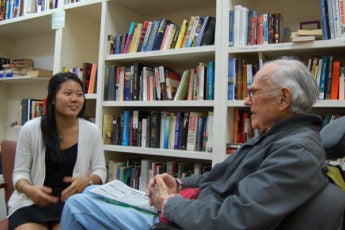

Social norms influence how conversations start and end and how speakers take turns to keep the conversation going.

Felipe Cabrera – conversation – CC BY 2.0.

Ending a conversation is similarly complex. I’m sure we’ve all been in a situation where we are “trapped” in a conversation that we need or want to get out of. Just walking away or ending a conversation without engaging in socially acceptable “leave-taking behaviors” would be considered a breach of social norms. Topic changes are often places where people can leave a conversation, but it is still routine for us to give a special reason for leaving, often in an apologetic tone (whether we mean it or not). Generally though, conversations come to an end through the cooperation of both people, as they offer and recognize typical signals that a topic area has been satisfactorily covered or that one or both people need to leave. It is customary in the United States for people to say they have to leave before they actually do and for that statement to be dismissed or ignored by the other person until additional leave-taking behaviors are enacted. When such cooperation is lacking, an awkward silence or abrupt ending can result, and as we’ve already learned, US Americans are not big fans of silence. Silence is not viewed the same way in other cultures, which leads us to our discussion of cultural context.

Language and Cultural Context

Culture isn’t solely determined by a person’s native language or nationality. It’s true that languages vary by country and region and that the language we speak influences our realities, but even people who speak the same language experience cultural differences because of their various intersecting cultural identities and personal experiences. We have a tendency to view our language as a whole more favorably than other languages. Although people may make persuasive arguments regarding which languages are more pleasing to the ear or difficult or easy to learn than others, no one language enables speakers to communicate more effectively than another (McCornack, 2007).

From birth we are socialized into our various cultural identities. As with the social context, this acculturation process is a combination of explicit and implicit lessons. A child in Colombia, which is considered a more collectivist country in which people value group membership and cohesion over individualism, may not be explicitly told, “You are a member of a collectivistic culture, so you should care more about the family and community than yourself.” This cultural value would be transmitted through daily actions and through language use. Just as babies acquire knowledge of language practices at an astonishing rate in their first two years of life, so do they acquire cultural knowledge and values that are embedded in those language practices. At nine months old, it is possible to distinguish babies based on their language. Even at this early stage of development, when most babies are babbling and just learning to recognize but not wholly reproduce verbal interaction patterns, a Colombian baby would sound different from a Brazilian baby, even though neither would actually be using words from their native languages of Spanish and Portuguese (Crystal, 2005).

The actual language we speak plays an important role in shaping our reality. Comparing languages, we can see differences in how we are able to talk about the world. In English, we have the words grandfather and grandmother , but no single word that distinguishes between a maternal grandfather and a paternal grandfather. But in Swedish, there’s a specific word for each grandparent: morfar is mother’s father, farfar is father’s father, farmor is father’s mother, and mormor is mother’s mother (Crystal, 2005). In this example, we can see that the words available to us, based on the language we speak, influence how we talk about the world due to differences in and limitations of vocabulary. The notion that language shapes our view of reality and our cultural patterns is best represented by the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. Although some scholars argue that our reality is determined by our language, we will take a more qualified view and presume that language plays a central role in influencing our realities but doesn’t determine them (Martin & Nakayama, 2010).

Culturally influenced differences in language and meaning can lead to some interesting encounters, ranging from awkward to informative to disastrous. In terms of awkwardness, you have likely heard stories of companies that failed to exhibit communication competence in their naming and/or advertising of products in another language. For example, in Taiwan, Pepsi used the slogan “Come Alive with Pepsi” only to later find out that when translated it meant, “Pepsi brings your ancestors back from the dead” (Kwintessential Limited, 2012). Similarly, American Motors introduced a new car called the Matador to the Puerto Rico market only to learn that Matador means “killer,” which wasn’t very comforting to potential buyers (Kwintessential, 2012). At a more informative level, the words we use to give positive reinforcement are culturally relative. In the United States and England, parents commonly positively and negatively reinforce their child’s behavior by saying, “Good girl” or “Good boy.” There isn’t an equivalent for such a phrase in other European languages, so the usage in only these two countries has been traced back to the puritan influence on beliefs about good and bad behavior (Wierzbicka, 2004). In terms of disastrous consequences, one of the most publicized and deadliest cross-cultural business mistakes occurred in India in 1984. Union Carbide, an American company, controlled a plant used to make pesticides. The company underestimated the amount of cross-cultural training that would be needed to allow the local workers, many of whom were not familiar with the technology or language/jargon used in the instructions for plant operations to do their jobs. This lack of competent communication led to a gas leak that immediately killed more than two thousand people and over time led to more than five hundred thousand injuries (Varma, 2012).

Accents and Dialects

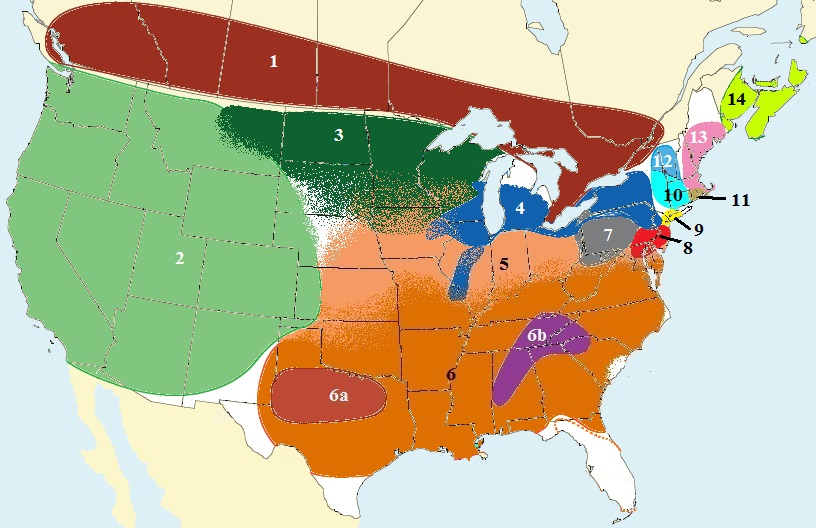

The documentary American Tongues , although dated at this point, is still a fascinating look at the rich tapestry of accents and dialects that makes up American English. Dialects are versions of languages that have distinct words, grammar, and pronunciation. Accents are distinct styles of pronunciation (Lustig & Koester, 2006). There can be multiple accents within one dialect. For example, people in the Appalachian Mountains of the eastern United States speak a dialect of American English that is characterized by remnants of the linguistic styles of Europeans who settled the area a couple hundred years earlier. Even though they speak this similar dialect, a person in Kentucky could still have an accent that is distinguishable from a person in western North Carolina.

American English has several dialects that vary based on region, class, and ancestry.

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY-SA 4.0.

Dialects and accents can vary by region, class, or ancestry, and they influence the impressions that we make of others. When I moved to Colorado from North Carolina, I was met with a very strange look when I used the word buggy to refer to a shopping cart. Research shows that people tend to think more positively about others who speak with a dialect similar to their own and think more negatively about people who speak differently. Of course, many people think they speak normally and perceive others to have an accent or dialect. Although dialects include the use of different words and phrases, it’s the tone of voice that often creates the strongest impression. For example, a person who speaks with a Southern accent may perceive a New Englander’s accent to be grating, harsh, or rude because the pitch is more nasal and the rate faster. Conversely, a New Englander may perceive a Southerner’s accent to be syrupy and slow, leading to an impression that the person speaking is uneducated.

Customs and Norms

Social norms are culturally relative. The words used in politeness rituals in one culture can mean something completely different in another. For example, thank you in American English acknowledges receiving something (a gift, a favor, a compliment), in British English it can mean “yes” similar to American English’s yes, please , and in French merci can mean “no” as in “no, thank you” (Crystal, 2005). Additionally, what is considered a powerful language style varies from culture to culture. Confrontational language, such as swearing, can be seen as powerful in Western cultures, even though it violates some language taboos, but would be seen as immature and weak in Japan (Wetzel, 1988).

Gender also affects how we use language, but not to the extent that most people think. Although there is a widespread belief that men are more likely to communicate in a clear and straightforward way and women are more likely to communicate in an emotional and indirect way, a meta-analysis of research findings from more than two hundred studies found only small differences in the personal disclosures of men and women (Dindia & Allen, 1992). Men and women’s levels of disclosure are even more similar when engaging in cross-gender communication, meaning men and woman are more similar when speaking to each other than when men speak to men or women speak to women. This could be due to the internalized pressure to speak about the other gender in socially sanctioned ways, in essence reinforcing the stereotypes when speaking to the same gender but challenging them in cross-gender encounters. Researchers also dispelled the belief that men interrupt more than women do, finding that men and women interrupt each other with similar frequency in cross-gender encounters (Dindia, 1987). These findings, which state that men and women communicate more similarly during cross-gender encounters and then communicate in more stereotypical ways in same-gender encounters, can be explained with communication accommodation theory.

Communication Accommodation and Code-Switching

Communication accommodation theory is a theory that explores why and how people modify their communication to fit situational, social, cultural, and relational contexts (Giles, Taylor, & Bourhis, 1973). Within communication accommodation, conversational partners may use convergence , meaning a person makes his or her communication more like another person’s. People who are accommodating in their communication style are seen as more competent, which illustrates the benefits of communicative flexibility. In order to be flexible, of course, people have to be aware of and monitor their own and others’ communication patterns. Conversely, conversational partners may use divergence , meaning a person uses communication to emphasize the differences between his or her conversational partner and his or herself.

Convergence and divergence can take place within the same conversation and may be used by one or both conversational partners. Convergence functions to make others feel at ease, to increase understanding, and to enhance social bonds. Divergence may be used to intentionally make another person feel unwelcome or perhaps to highlight a personal, group, or cultural identity. For example, African American women use certain verbal communication patterns when communicating with other African American women as a way to highlight their racial identity and create group solidarity. In situations where multiple races interact, the women usually don’t use those same patterns, instead accommodating the language patterns of the larger group. While communication accommodation might involve anything from adjusting how fast or slow you talk to how long you speak during each turn, code-switching refers to changes in accent, dialect, or language (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). There are many reasons that people might code-switch. Regarding accents, some people hire vocal coaches or speech-language pathologists to help them alter their accent. If a Southern person thinks their accent is leading others to form unfavorable impressions, they can consciously change their accent with much practice and effort. Once their ability to speak without their Southern accent is honed, they may be able to switch very quickly between their native accent when speaking with friends and family and their modified accent when speaking in professional settings.

People who work or live in multilingual settings may engage in code-switching several times a day.

Eltpics – Welsh – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Additionally, people who work or live in multilingual settings may code-switch many times throughout the day, or even within a single conversation. Increasing outsourcing and globalization have produced heightened pressures for code-switching. Call center workers in India have faced strong negative reactions from British and American customers who insist on “speaking to someone who speaks English.” Although many Indians learn English in schools as a result of British colonization, their accents prove to be off-putting to people who want to get their cable package changed or book an airline ticket. Now some Indian call center workers are going through intense training to be able to code-switch and accommodate the speaking style of their customers. What is being called the “Anglo-Americanization of India” entails “accent-neutralization,” lessons on American culture (using things like Sex and the City DVDs), and the use of Anglo-American-sounding names like Sean and Peggy (Pal, 2004). As our interactions continue to occur in more multinational contexts, the expectations for code-switching and accommodation are sure to increase. It is important for us to consider the intersection of culture and power and think critically about the ways in which expectations for code-switching may be based on cultural biases.

Language and Cultural Bias

In the previous example about code-switching and communication accommodation in Indian call centers, the move toward accent neutralization is a response to the “racist abuse” these workers receive from customers (Nadeem, 2012). Anger in Western countries about job losses and economic uncertainty has increased the amount of racially targeted verbal attacks on international call center employees. It was recently reported that more call center workers are now quitting their jobs as a result of the verbal abuse and that 25 percent of workers who have recently quit say such abuse was a major source of stress (Gentleman, 2005). Such verbal attacks are not new; they represent a common but negative way that cultural bias explicitly manifests in our language use.

Cultural bias is a skewed way of viewing or talking about a group that is typically negative. Bias has a way of creeping into our daily language use, often under our awareness. Culturally biased language can make reference to one or more cultural identities, including race, gender, age, sexual orientation, and ability. There are other sociocultural identities that can be the subject of biased language, but we will focus our discussion on these five. Much biased language is based on stereotypes and myths that influence the words we use. Bias is both intentional and unintentional, but as we’ve already discussed, we have to be accountable for what we say even if we didn’t “intend” a particular meaning—remember, meaning is generated; it doesn’t exist inside our thoughts or words. We will discuss specific ways in which cultural bias manifests in our language and ways to become more aware of bias. Becoming aware of and addressing cultural bias is not the same thing as engaging in “political correctness.” Political correctness takes awareness to the extreme but doesn’t do much to address cultural bias aside from make people feel like they are walking on eggshells. That kind of pressure can lead people to avoid discussions about cultural identities or avoid people with different cultural identities. Our goal is not to eliminate all cultural bias from verbal communication or to never offend anyone, intentionally or otherwise. Instead, we will continue to use guidelines for ethical communication that we have already discussed and strive to increase our competence. The following discussion also focuses on bias rather than preferred terminology or outright discriminatory language, which will be addressed more in Chapter 8 “Culture and Communication” , which discusses culture and communication.

People sometimes use euphemisms for race that illustrate bias because the terms are usually implicitly compared to the dominant group (Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 2010). For example, referring to a person as “urban” or a neighborhood as “inner city” can be an accurate descriptor, but when such words are used as a substitute for racial identity, they illustrate cultural biases that equate certain races with cities and poverty. Using adjectives like articulate or well-dressed in statements like “My black coworker is articulate” reinforces negative stereotypes even though these words are typically viewed as positive. Terms like nonwhite set up whiteness as the norm, which implies that white people are the norm against which all other races should be compared. Biased language also reduces the diversity within certain racial groups—for example, referring to anyone who looks like they are of Asian descent as Chinese or everyone who “looks” Latino/a as Mexicans. Some people with racial identities other than white, including people who are multiracial, use the label person/people of color to indicate solidarity among groups, but it is likely that they still prefer a more specific label when referring to an individual or referencing a specific racial group.

Language has a tendency to exaggerate perceived and stereotypical differences between men and women. The use of the term opposite sex presumes that men and women are opposites, like positive and negative poles of a magnet, which is obviously not true or men and women wouldn’t be able to have successful interactions or relationships. A term like other gender doesn’t presume opposites and acknowledges that male and female identities and communication are more influenced by gender, which is the social and cultural meanings and norms associated with males and females, than sex, which is the physiology and genetic makeup of a male and female. One key to avoiding gendered bias in language is to avoid the generic use of he when referring to something relevant to males and females. Instead, you can informally use a gender-neutral pronoun like they or their or you can use his or her (Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 2010). When giving a series of examples, you can alternate usage of masculine and feminine pronouns, switching with each example. We have lasting gendered associations with certain occupations that have tended to be male or female dominated, which erase the presence of both genders. Other words reflect the general masculine bias present in English. The following word pairs show the gender-biased term followed by an unbiased term: waitress/server, chairman / chair or chairperson, mankind/people, cameraman / camera operator, mailman / postal worker, sportsmanship / fair play. Common language practices also tend to infantilize women but not men, when, for example, women are referred to as chicks , girls , or babes . Since there is no linguistic equivalent that indicates the marital status of men before their name, using Ms. instead of Miss or Mrs. helps reduce bias.

Language that includes age bias can be directed toward older or younger people. Descriptions of younger people often presume recklessness or inexperience, while those of older people presume frailty or disconnection. The term elderly generally refers to people over sixty-five, but it has connotations of weakness, which isn’t accurate because there are plenty of people over sixty-five who are stronger and more athletic than people in their twenties and thirties. Even though it’s generic, older people doesn’t really have negative implications. More specific words that describe groups of older people include grandmothers/grandfathers (even though they can be fairly young too), retirees , or people over sixty-five (Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 2010). Referring to people over the age of eighteen as boys or girls isn’t typically viewed as appropriate.

Age bias can appear in language directed toward younger or older people.

Davide Mauro – Old and young – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Sexual Orientation

Discussions of sexual and affectional orientation range from everyday conversations to contentious political and personal debates. The negative stereotypes that have been associated with homosexuality, including deviance, mental illness, and criminal behavior, continue to influence our language use (American Psychological Association, 2012). Terminology related to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and asexual (LGBTQA+) people can be confusing, so let’s spend some time raise our awareness about preferred labels. First, sexual orientation is the term preferred to sexual preference . Preference suggests a voluntary choice, as in someone has a preference for cheddar or American cheese, which doesn’t reflect the experience of most LGBTQA+ people or research findings that show sexuality is more complex. You may also see affectional orientation included with sexual orientation because it acknowledges that LGBTQA+ relationships, like heterosexual relationships, are about intimacy and closeness (affection) that is not just sexually based. Most people also prefer the labels gay , lesbian , or bisexual to homosexual , which is clinical and doesn’t so much refer to an identity as a sex act. Language regarding romantic relationships contains bias when heterosexuality is assumed. Keep in mind that individuals are not allowed to marry someone of the same gender in most states in the United States. For example, if you ask a gay man who has been in a committed partnership for ten years if he is “married or single,” how should he answer that question? Comments comparing LGBTQA+ people to “normal” people, although possibly intended to be positive, reinforces the stereotype that LGBTQA+ people are abnormal. Don’t presume you can identify a person’s sexual orientation by looking at them or talking to them. Don’t assume that LGBTQA+ people will “come out” to you. Given that many LGBTQA+ people have faced and continue to face regular discrimination, they may be cautious about disclosing their identities. However, using gender neutral terminology like partner and avoiding other biased language mentioned previously may create a climate in which a LGBTQA+ person feels comfortable disclosing his or her sexual orientation identity. Conversely, the casual use of phrases like that’s gay to mean “that’s stupid” may create an environment in which LGBTQA+ people do not feel comfortable. Even though people don’t often use the phrase to actually refer to sexual orientation, campaigns like “ThinkB4YouSpeak.com” try to educate people about the power that language has and how we should all be more conscious of the words we use.

People with disabilities make up a diverse group that has increasingly come to be viewed as a cultural/social identity group. People without disabilities are often referred to as able-bodied . As with sexual orientation, comparing people with disabilities to “normal” people implies that there is an agreed-on definition of what “normal” is and that people with disabilities are “abnormal.” Disability is also preferred to the word handicap . Just because someone is disabled doesn’t mean he or she is also handicapped. The environment around them rather than their disability often handicaps people with disabilities (Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 2010). Ignoring the environment as the source of a handicap and placing it on the person fits into a pattern of reducing people with disabilities to their disability—for example, calling someone a paraplegic instead of a person with paraplegia. In many cases, as with sexual orientation, race, age, and gender, verbally marking a person as disabled isn’t relevant and doesn’t need spotlighting. Language used in conjunction with disabilities also tends to portray people as victims of their disability and paint pictures of their lives as gloomy, dreadful, or painful. Such descriptors are often generalizations or completely inaccurate.

“Getting Critical”

Hate Speech

Hate is a term that has many different meanings and can be used to communicate teasing, mild annoyance, or anger. The term hate , as it relates to hate speech, has a much more complex and serious meaning. Hate refers to extreme negative beliefs and feelings toward a group or member of a group because of their race, gender, religion, sexual orientation, or ability (Waltman & Haas, 2011). We can get a better understanding of the intensity of hate by distinguishing it from anger, which is an emotion that we experience much more regularly. First, anger is directed toward an individual, while hate is directed toward a social or cultural group. Second, anger doesn’t prevent a person from having sympathy for the target of his or her anger, but hate erases sympathy for the target. Third, anger is usually the result of personal insult or injury, but hate can exist and grow even with no direct interaction with the target. Fourth, anger isn’t an emotion that people typically find pleasure in, while hatred can create feelings of self-righteousness and superiority that lead to pleasure. Last, anger is an emotion that usually dissipates as time passes, eventually going away, while hate can endure for much longer (Waltman & Haas, 2011). Hate speech is a verbal manifestation of this intense emotional and mental state.

Hate speech is usually used by people who have a polarized view of their own group (the in-group) and another group (the out-group). Hate speech is then used to intimidate people in the out-group and to motivate and influence members of the in-group. Hate speech often promotes hate-based violence and is also used to solidify in-group identification and attract new members (Waltman & Haas, 2011). Perpetrators of hate speech often engage in totalizing, which means they define a person or a group based on one quality or characteristic, ignoring all others. A Lebanese American may be the target of hate speech because the perpetrators reduce him to a Muslim—whether he actually is Muslim or not would be irrelevant. Grouping all Middle Eastern- or Arab-looking people together is a dehumanizing activity that is typical to hate speech.

Incidents of hate speech and hate crimes have increased over the past fifteen years. Hate crimes, in particular, have gotten more attention due to the passage of more laws against hate crimes and the increased amount of tracking by various levels of law enforcement. The Internet has also made it easier for hate groups to organize and spread their hateful messages. As these changes have taken place over the past fifteen years, there has been much discussion about hate speech and its legal and constitutional implications. While hate crimes resulting in damage to a person or property are regularly prosecuted, it is sometimes argued that hate speech that doesn’t result in such damage is protected under the US Constitution’s First Amendment, which guarantees free speech. Just recently, in 2011, the Supreme Court found in the Snyder v. Phelps case that speech and actions of the members of the Westboro Baptist Church, who regularly protest the funerals of American soldiers with signs reading things like “Thank God for Dead Soldiers” and “Fag Sin = 9/11,” were protected and not criminal. Chief Justice Roberts wrote in the decision, “We cannot react to [the Snyder family’s] pain by punishing the speaker. As a nation we have chosen a different course—to protect even hurtful speech on public issues to ensure that we do not stifle public debate” (Exploring Constitutional Conflicts, 2012).

- Do you think the First Amendment of the Constitution, guaranteeing free speech to US citizens, should protect hate speech? Why or why not?

- Visit the Southern Poverty Law Center’s “Hate Map” (Southern Poverty Law Center, 2012) (http://www.splcenter.org/get-informed/hate-map) to see what hate groups they have identified in your state. Are you surprised by the number/nature of the groups listed in your state? Briefly describe a group that you didn’t know about and identify the target of its hate and the reasons it gives for its hate speech.

Key Takeaways

- Getting integrated: Social context influences the ways in which we use language, and we have been socialized to follow implicit social rules like those that guide the flow of conversations, including how we start and end our interactions and how we change topics. The way we use language changes as we shift among academic, professional, personal, and civic contexts.

- The language that we speak influences our cultural identities and our social realities. We internalize norms and rules that help us function in our own culture but that can lead to misunderstanding when used in other cultural contexts.

- We can adapt to different cultural contexts by purposely changing our communication. Communication accommodation theory explains that people may adapt their communication to be more similar to or different from others based on various contexts.

- We should become aware of how our verbal communication reveals biases toward various cultural identities based on race, gender, age, sexual orientation, and ability.

- Recall a conversation that became awkward when you or the other person deviated from the social norms that manage conversation flow. Was the awkwardness at the beginning, end, or during a topic change? After reviewing some of the common norms discussed in the chapter, what do you think was the source of the awkwardness?

- Describe an accent or a dialect that you find pleasing/interesting. Describe an accent/dialect that you do not find pleasing/interesting. Why do you think you evaluate one positively and the other negatively?

- Review how cultural bias relates to the five cultural identities discussed earlier. Identify something you learned about bias related to one of these identities that you didn’t know before. What can you do now to be more aware of how verbal communication can reinforce cultural biases?

American Psychological Association, “Supplemental Material: Writing Clearly and Concisely,” accessed June 7, 2012, http://www.apastyle.org/manual/supplement/redirects/pubman-ch03.13.aspx .

Crystal, D., How Language Works: How Babies Babble, Words Change Meaning, and Languages Live or Die (Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2005), 155.

Dindia, K., “The Effect of Sex of Subject and Sex of Partner on Interruptions,” Human Communication Research 13, no. 3 (1987): 345–71.

Dindia, K. and Mike Allen, “Sex Differences in Self-Disclosure: A Meta Analysis,” Psychological Bulletin 112, no. 1 (1992): 106–24.

Exploring Constitutional Conflicts , “Regulation of Fighting Words and Hate Speech,” accessed June 7, 2012, http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/conlaw/hatespeech.htm .

Gentleman, A., “Indiana Call Staff Quit over Abuse on the Line,” The Guardian , May 28, 2005, accessed June 7, 2012, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2005/may/29/india.ameliagentleman .

Giles, H., Donald M. Taylor, and Richard Bourhis, “Toward a Theory of Interpersonal Accommodation through Language: Some Canadian Data,” Language and Society 2, no. 2 (1973): 177–92.

Kwintessential Limited , “Results of Poor Cross Cultural Awareness,” accessed June 7, 2012, http://www.kwintessential.co.uk/cultural-services/articles/Results of Poor Cross Cultural Awareness.html .

Lustig, M. W. and Jolene Koester, Intercultural Competence: Interpersonal Communication across Cultures , 2nd ed. (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2006), 199–200.

Martin, J. N. and Thomas K. Nakayama, Intercultural Communication in Contexts , 5th ed. (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill, 2010), 222–24.

McCornack, S., Reflect and Relate: An Introduction to Interpersonal Communication (Boston, MA: Bedford/St Martin’s, 2007), 224–25.

Nadeem, S., “Accent Neutralisation and a Crisis of Identity in India’s Call Centres,” The Guardian , February 9, 2011, accessed June 7, 2012, http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/feb/09/india-call-centres-accent-neutralisation .

Pal, A., “Indian by Day, American by Night,” The Progressive , August 2004, accessed June 7, 2012, http://www.progressive.org/mag_pal0804 .

Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 6th ed. (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2010), 71–76.

Southern Poverty Law Center , “Hate Map,” accessed June 7, 2012, http://www.splcenter.org/get-informed/hate-map.

Varma, S., “Arbitrary? 92% of All Injuries Termed Minor,” The Times of India , June 20, 2010, accessed June 7, 2012, http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2010-06-20/india/28309628_1_injuries-gases-cases .

Waltman, M. and John Haas, The Communication of Hate (New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing, 2011), 33.

Wetzel, P. J., “Are ‘Powerless’ Communication Strategies the Japanese Norm?” Language in Society 17, no. 4 (1988): 555–64.

Wierzbicka, A., “The English Expressions Good Boy and Good Girl and Cultural Models of Child Rearing,” Culture and Psychology 10, no. 3 (2004): 251–78.

Communication in the Real World Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.1: Language and Culture

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 54515

- Butte College

How do you communicate? How do you think? We use language as a system to create and exchange meaning with one another, and the types of words we use influence both our perceptions and others interpretation of our meanings. Language is one of the more conspicuous expressions of culture. As such, the role of language is central to our understanding of intercultural communication.

The Study of Language

Linguistics is the study of language and its structure. Linguistics deals with the study of particular languages and the search for general properties common to all languages. It also includes explorations into language variations (i.e. dialects), how languages change over time, how language is stored and processed in the brain, and how children learn language. The study of linguistics is an important part of intercultural communication. Areas of research for linguists include phonetics (the study of the production, acoustics, and hearing speech sounds), phonology (the patterning of sounds), morphology (the patterning of words), syntax (the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), and pragmatics (language in context). When you study linguistics, you gain insight into one of the most fundamental parts of being human—the ability to communicate. You can understand how language works, how it is used, plus how it is developed and changes over time. Since language is universal to all human interactions, the knowledge attained through linguistics is fundamental to understanding cultures.

World Languages

Languages differ in a number of ways. Not all languages, for example, have a written form. Those that do use a variety of writing systems. Russian uses the Cyrillic alphabet, while Hindi uses Devanagari. Chinese has a particularly ancient and rich written language, with many thousands of pictographic characters. Because of the complexity and variety of Chinese characters, there is a simplified equivalent called Pinyin, which enables Chinese characters to be referenced using the Latin alphabet. This is of particular usefulness in electronic communication. The arrival of touch-enabled smartphones has been of great benefit to languages with alternative writing systems such as Chinese or Arabic (Godwin-Jones, 2017d). Smartphones and word processors can now support writing systems that write right to left such as Hebrew.

Sample text in Korean (Hangeul)

모든 인간은 태어날 때부터 자유로우며 그 존엄과 권리에 있어 동등하다. 인간은 천부척으로 이성과 양싱을 부여받았으며 서로 형첸개의 청신으로 헹동하여야 한다.

Translation:

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Languages evolve over time. Historical linguists trace these changes and describe how languages relate to one another. Language families group languages together, according to similarities in vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation. Languages within a same family derive from a common ancestor, called a proto-language (Nowak & Krakauer, 1999). Membership in a given family is determined through comparative linguistics , i.e., studying and comparing the characteristics of the languages in question. Linguists use the metaphor of a family tree to depict the relationships among languages. One of the largest families is Indo-European , with more than 4000 languages or dialects represented. Indo-European languages include Spanish, English, Hindi/Urdu, Portuguese, Bengali, Russian, and Punjabi, each with over 100 million speakers, followed by German, French and Persian. Nearly half the human population speaks an Indo-European language as a first language (Skirgård, 2017). How the languages are related can be shown in the similar terms for "mother" (see sidebar).

Mother in Indo-European languages

- Sanskrit matar

- Greek mater

Some regions have particularly rich linguistic traditions, such as is the case for Africa and India. In India, there are not only Indo-European languages spoken (Hindi, Punjabi), but also languages from other families such as Dravidian (Telugu, Tamil), Austroasiatic, Sino-Tibetan, Tai-Kadai, and a few other minor language families. Papua/New Guinea has a particularly rich vareity of languages; with over 850 languages, it is the most linguistically diverse place on earth. In such cultures, most people are multilingual, often speaking 3 or more languages, along with a lingua franca - a common denominator -, such as Swahili in parts of Africa, English in India, or Tok Pisin, an English-based creole, in New Guinea.

There are languages which do not belong to families, known as language isolates (Campbell, 2010). Well-known examples include Basque, a language spoken in the border area between France and Spain, and Korean. Language isolates tend to develop in geographical isolation, separated from other regions, for example, through mountain ranges or the sea. In some cases, geographical features such as dense forests may result in different dialects or even languages spoken in areas which are actually quite close to one another. A dialect refers to a variety of a language that is used by particular group of speakers, defined normally regionally, but could be related to social class or ethnicity as well. Dialects are closely related to one another and normally mutually intelligible.

Language Is Arbitrary and Symbolic

Words, by themselves, do not have any inherent meaning. Humans give meaning to them, and their meanings change across time. For example, there is no inherent, logical connection between "cat" or (or the German Katze or Chinese猫) and the feline animal. We negotiate the meaning of the word “kat,” and define it, through visual images or dialog, in order to communicate with our audience.

Words have two types of meanings: denotative and connotative . Attention to both is necessary to reduce the possibility of misinterpretation. The denotative meaning is the common meaning, often found in the dictionary. The connotative meaning is often not found in the dictionary but in the community of users itself. It can involve an emotional association with a word, positive or negative, and can be individual or collective, but is not universal. An example of this could be the term “rugged individualism” which comes from “rugged” or capable of withstanding rough handling and “individualism” or being independent and self-reliant. In the United States, describing someone in this way would have a positive connotation, but for people from a collectivistic orientation, it might be the opposite.

Language Evolves

Many people view language as fixed, but in fact, language constantly changes. As time passes and technology changes, people add new words to their language, repurpose old ones, and discard archaic ones. New additions to American English in the last few decades include blog , sexting , and selfie . Repurposed additions to American English include cyberbullying , tweet , and app (from application). Whereas affright , cannonade , and fain are becoming extinct in modern American English. Other times, speakers of a language borrow words and phrases from other languages and incorporate them into their own. Wisconsin, Oregon, and Wyoming were all borrowed from Native American languages. Typhoon is from Mandarin Chinese, and influenza is from Italian.

Language Shapes Our Thought

What would your life be like if you had been raised in a country other than the one where you grew up? Or suppose you had been born male instead of female, or vice versa. You would have learned another set of customs, values, traditions, other language patterns, and ways of communicating. You would be a different person who communicated in different ways. The link between language and culture and the idea that language shapes how we think about our world was famously described in the work of Benjamin Whorf and Edward Sapir. The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis postulates that your native language has a profound influence on how you see the world, that you perceive reality in the context of the language you have available to describe it. According to Sapir (1929), "The 'real world' is to a large extent unconsciously built up on the language habits of the group. The world in which different societies live are distinct worlds, not merely the same world with different labels attached" (p. 162). From this perspective, all language use – from the words we use to describe objects to the way sentences are structured – is tied closely to the culture in which it is spoken. In 1940, Whorf wrote:

The background linguistic system (in other words, the grammar) of each language is not merely a reproducing instrument for voicing ideas but rather is itself the shaper of ideas, the program and guide for people's mental activity, for their analysis of impressions, for their synthesis of their mental stock in trade. Formulation of ideas is not an independent process, strictly rational in the old sense, but is part of a particular grammar and differs, from slightly to greatly, among different grammars...We dissect nature along lines laid down by our native languages (p. 231).

Whorf studied native American languages such as Hopi and was struck by differences to English which pointed to different ways of viewing the world, for example, how the Hopi language has no present, past, or future tense verbs. Instead, it divides the world into what Whorf called the manifested and unmanifest domains. The manifested domain deals with the physical universe, including the present, the immediate past and future; the verb system uses the same basic structure for all of them. The unmanifest domain involves the remote past and the future, as well as the world of desires, thought, and life forces. The set of verb forms dealing with this domain are consistent for all of these areas, and are different from the manifested ones. Also, there are no words for hours, minutes, or days of the week.

Taken to its extreme, this kind of linguistic determinism would prevent native speakers of different languages from having the same thoughts or sharing a worldview. This idea suggests that we cannot conceive of that for which we lack a vocabulary or that language quite literally defines the boundaries of our thinking. More widely accepted today is the concept of linguistic relativity , meaning that language shapes our views of the world but is not an absolute determiner of how or what we think. After all, translation is in fact possible, and bilingualism exists, both of which phenomena should be problematic in a strict interpretation of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. It is also the case that many cultures are multilingual, with children growing up exposed to multiple languages.

- Linguistic determinism: language controls thought in culture.

- Linguistic relativity: language influences thought in culture, and therefore differences among languages cause differences in the thoughts of their speakers. Hua (2014), p. 176

No matter what linguistic theory one may hold to be valid, there is little argument that the vocabulary of a language does in fact reflect important aspects of everyday life. Linguist Anna Wierzbicka (2013) provides interesting examples of expressions from the Australian aboriginal language of Warlpiri:

- japi — "entrance to sugar ant’s nest"

- laja — "hole or burrow of lizard"

- kuyu — "meat; meated animal" [including edible birds, but not other birds]

- karnpi — "fat under the skin of emu"

- papapapa-ma — "to make the sound of a male emu calling to its chicks"

- yulu — "limp, relaxed—of slain kangaroo whose hindleg have been broken (in preparation for cooking)"

From a Warlpiri speaker’s point of view, these single words point to important features of the environment, as potential sources of shelter and food, but there are no corresponding words in European languages or in most other languages. Wierzbicka comments:

As these examples illustrate, the words of a language reflect the speakers’ special interests. For the speakers of a particular language, their words "fit the world" as they see it—but how they see it depends, to some extent, on what they want to see and what they pay attention to. This is true also of European languages, and English is no exception, either. The conviction that the words of our native language fit the world as it really is, is deeply rooted in the thinking of many people, particularly those who have never been forced to move, existentially, from one language into another and to leave the certainties of their home language (p. 6).

Learning a second language leads one early on to appreciate the fact that there may not be a one-to-one correspondence between words in one language and those in another. While the dictionary definitions (denotation) may be the same, the actual usage in any given context (connotation) may be quite different. The word amigo in Spanish is the equivalent of the word friend in English, but the relationships described by that word can be quite different. During my travels in Guatemala, I experienced " hola amigo, " as a common greeting, even among strangers. Just as in English, a Facebook "friend" is quite different from a childhood "friend". The German word Bier , refers as does the English "beer", to an alcoholic drink made from barley, hops, and water. In a German context, the word is used to describe an everyday drink commonly consumed with meals or in other social situations. In the American English context, usage of the word, "beer," immediately brings to the fore its status as alcohol, thus a beverage that is strictly regulated and its consumption restricted.

Differences in available words to describe everyday phenomena is immediately evident when one compares languages or examines vocabulary used in particular situations. That might include a specific small culture, such as dog lovers or sailing enthusiasts, for example, who use a much more extensive vocabulary to describe, respectively, dog breeds or parts of a ship, than would be familiar to most people, no matter whether they are native speakers of the language or not. Sometimes, a special language is developed by a group, sometimes labeled a jargon , which often references a specialized technical language. A related term is an argot , a kind of secret language designed to exclude outsiders, such as the language used by criminal gangs.

Less immediately evident than vocabulary differences in comparing languages are differences in grammatical structures. If, for example, a language has different personal pronouns for direct address, such as the informal tu in French and the formal vous , both meaning ‘you’, that distinction is a reflection of one aspect of the culture. It indicates that there is a built-in awareness and significance to social differentiation and that a more formal level of language use is available. Native speakers of English may have difficulty in learning how to use the different forms of address in French, or as they exist in other languages such as German or Spanish. Speakers of American English, in particular, are inclined towards informal modes of address, moving to a first-name basis as soon as possible. Using informal address inappropriately can cause considerable social friction. It takes a good deal of language socialization to acquire this kind of pragmatic ability, that is to say, sufficient exposure to the forms being used correctly. While native speakers of English may deplore the formality of vous or its equivalent in other languages, in cultures where these distinctions exist, they provide a valuable device for maintaining relational distance when desired, for clearly distinguishing friends from acquaintances, and for preserving social harmony in institutional settings. Expanding on this notion, Students of Korean learn early on in their studies that there is not just a distinction between familiar and formal "you", as exists in many languages, but that the code of respect and politeness of Korean culture dictates different vocabulary, intonation, and speech patterns depending on one's relationship to the addressee. This can extend to nonverbal conventions as well, such as bowing or increasing personal space.

Contributors and Attributions

Language and Culture in Context: A Primer on Intercultural Communication , by Robert Godwin-Jones. Provided by LibreTexts. License: CC-BY-NC

Intercultural Communication for the Community College , by Karen Krumrey-Fulks. Provided by LibreTexts. License: CC-BY-NC-SA

Perspectives: An Open Invitation to Cultural Anthropology , by Brown, McIlwraith & Gonzalez. Provided by LibreTexts. License CC-BY-NC.

Does Language Influence Culture?

Lost in Translation:

New cognitive research suggests that language profoundly influences the way people see the world; a different sense of blame in Japanese and Spanish.

By Lera Boroditsky

Do the languages we speak shape the way we think? Do they merely express thoughts, or do the structures in languages (without our knowledge or consent) shape the very thoughts we wish to express?

Take "Humpty Dumpty sat on a..." Even this snippet of a nursery rhyme reveals how much languages can differ from one another. In English, we have to mark the verb for tense; in this case, we say "sat" rather than "sit." In Indonesian you need not (in fact, you can't) change the verb to mark tense.

In Russian, you would have to mark tense and also gender, changing the verb if Mrs. Dumpty did the sitting. You would also have to decide if the sitting event was completed or not. If our ovoid hero sat on the wall for the entire time he was meant to, it would be a different form of the verb than if, say, he had a great fall.

In Turkish, you would have to include in the verb how you acquired this information. For example, if you saw the chubby fellow on the wall with your own eyes, you'd use one form of the verb, but if you had simply read or heard about it, you'd use a different form.

Do English, Indonesian, Russian and Turkish speakers end up attending to, understanding, and remembering their experiences differently simply because they speak different languages?

These questions touch on all the major controversies in the study of mind, with important implications for politics, law and religion. Yet very little empirical work had been done on these questions until recently. The idea that language might shape thought was for a long time considered untestable at best and more often simply crazy and wrong. Now, a flurry of new cognitive science research is showing that in fact, language does profoundly influence how we see the world.

The question of whether languages shape the way we think goes back centuries; Charlemagne proclaimed that "to have a second language is to have a second soul." But the idea went out of favor with scientists when Noam Chomsky's theories of language gained popularity in the 1960s and '70s. Dr. Chomsky proposed that there is a universal grammar for all human languages—essentially, that languages don't really differ from one another in significant ways. And because languages didn't differ from one another, the theory went, it made no sense to ask whether linguistic differences led to differences in thinking.

The search for linguistic universals yielded interesting data on languages, but after decades of work, not a single proposed universal has withstood scrutiny. Instead, as linguists probed deeper into the world's languages (7,000 or so, only a fraction of them analyzed), innumerable unpredictable differences emerged.

Of course, just because people talk differently doesn't necessarily mean they think differently. In the past decade, cognitive scientists have begun to measure not just how people talk, but also how they think, asking whether our understanding of even such fundamental domains of experience as space, time and causality could be constructed by language.

For example, in Pormpuraaw, a remote Aboriginal community in Australia, the indigenous languages don't use terms like "left" and "right." Instead, everything is talked about in terms of absolute cardinal directions (north, south, east, west), which means you say things like, "There's an ant on your southwest leg." To say hello in Pormpuraaw, one asks, "Where are you going?", and an appropriate response might be, "A long way to the south-southwest. How about you?" If you don't know which way is which, you literally can't get past hello.

About a third of the world's languages (spoken in all kinds of physical environments) rely on absolute directions for space. As a result of this constant linguistic training, speakers of such languages are remarkably good at staying oriented and keeping track of where they are, even in unfamiliar landscapes. They perform navigational feats scientists once thought were beyond human capabilities. This is a big difference, a fundamentally different way of conceptualizing space, trained by language.

Differences in how people think about space don't end there. People rely on their spatial knowledge to build many other more complex or abstract representations including time, number, musical pitch, kinship relations, morality and emotions. So if Pormpuraawans think differently about space, do they also think differently about other things, like time?

To find out, my colleague Alice Gaby and I traveled to Australia and gave Pormpuraawans sets of pictures that showed temporal progressions (for example, pictures of a man at different ages, or a crocodile growing, or a banana being eaten). Their job was to arrange the shuffled photos on the ground to show the correct temporal order. We tested each person in two separate sittings, each time facing in a different cardinal direction. When asked to do this, English speakers arrange time from left to right. Hebrew speakers do it from right to left (because Hebrew is written from right to left).

Pormpuraawans, we found, arranged time from east to west. That is, seated facing south, time went left to right. When facing north, right to left. When facing east, toward the body, and so on. Of course, we never told any of our participants which direction they faced. The Pormpuraawans not only knew that already, but they also spontaneously used this spatial orientation to construct their representations of time. And many other ways to organize time exist in the world's languages. In Mandarin, the future can be below and the past above. In Aymara, spoken in South America, the future is behind and the past in front.

In addition to space and time, languages also shape how we understand causality. For example, English likes to describe events in terms of agents doing things. English speakers tend to say things like "John broke the vase" even for accidents. Speakers of Spanish or Japanese would be more likely to say "the vase broke itself." Such differences between languages have profound consequences for how their speakers understand events, construct notions of causality and agency, what they remember as eyewitnesses and how much they blame and punish others.

In studies conducted by Caitlin Fausey at Stanford, speakers of English, Spanish and Japanese watched videos of two people popping balloons, breaking eggs and spilling drinks either intentionally or accidentally. Later everyone got a surprise memory test: For each event, can you remember who did it? She discovered a striking cross-linguistic difference in eyewitness memory. Spanish and Japanese speakers did not remember the agents of accidental events as well as did English speakers. Mind you, they remembered the agents of intentional events (for which their language would mention the agent) just fine. But for accidental events, when one wouldn't normally mention the agent in Spanish or Japanese, they didn't encode or remember the agent as well.

In another study, English speakers watched the video of Janet Jackson's infamous "wardrobe malfunction" (a wonderful nonagentive coinage introduced into the English language by Justin Timberlake), accompanied by one of two written reports. The reports were identical except in the last sentence where one used the agentive phrase "ripped the costume" while the other said "the costume ripped." Even though everyone watched the same video and witnessed the ripping with their own eyes, language mattered. Not only did people who read "ripped the costume" blame Justin Timberlake more, they also levied a whopping 53% more in fines.

Beyond space, time and causality, patterns in language have been shown to shape many other domains of thought. Russian speakers, who make an extra distinction between light and dark blues in their language, are better able to visually discriminate shades of blue. The Piraha, a tribe in the Amazon in Brazil, whose language eschews number words in favor of terms like few and many, are not able to keep track of exact quantities. And Shakespeare, it turns out, was wrong about roses: Roses by many other names (as told to blindfolded subjects) do not smell as sweet.

Patterns in language offer a window on a culture's dispositions and priorities. For example, English sentence structures focus on agents, and in our criminal-justice system, justice has been done when we've found the transgressor and punished him or her accordingly (rather than finding the victims and restituting appropriately, an alternative approach to justice). So does the language shape cultural values, or does the influence go the other way, or both?