- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Journal of Public Health

- About the Faculty of Public Health of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom

- Editorial Board

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Adapting to the culture of ‘new normal’: an emerging response to COVID-19

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Jeff Clyde G Corpuz, Adapting to the culture of ‘new normal’: an emerging response to COVID-19, Journal of Public Health , Volume 43, Issue 2, June 2021, Pages e344–e345, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab057

- Permissions Icon Permissions

A year after COVID-19 pandemic has emerged, we have suddenly been forced to adapt to the ‘new normal’: work-from-home setting, parents home-schooling their children in a new blended learning setting, lockdown and quarantine, and the mandatory wearing of face mask and face shields in public. For many, 2020 has already been earmarked as ‘the worst’ year in the 21st century. Ripples from the current situation have spread into the personal, social, economic and spiritual spheres. Is this new normal really new or is it a reiteration of the old? A recent correspondence published in this journal rightly pointed out the involvement of a ‘supportive’ government, ‘creative’ church and an ‘adaptive’ public in the so-called culture. However, I argue that adapting to the ‘new normal’ can greatly affect the future. I would carefully suggest that we examine the context and the location of culture in which adaptations are needed.

To live in the world is to adapt constantly. A year after COVID-19 pandemic has emerged, we have suddenly been forced to adapt to the ‘new normal’: work-from-home setting, parents home-schooling their children in a new blended learning setting, lockdown and quarantine, and the mandatory wearing of face mask and face shields in public. For many, 2020 has already been earmarked as ‘the worst’ year in the 21st century. 1 Ripples from the current situation have spread into the personal, social, economic and spiritual spheres. Is this new normal really new or is it a reiteration of the old? A recent correspondence published in this journal rightly pointed out the involvement of a ‘supportive’ government, ‘creative’ church and an ‘adaptive’ public in the so-called culture. 2 However, I argue that adapting to the ‘new normal’ can greatly affect the future. I would carefully suggest that we examine the context and the location of culture in which adaptations are needed.

The term ‘new normal’ first appeared during the 2008 financial crisis to refer to the dramatic economic, cultural and social transformations that caused precariousness and social unrest, impacting collective perceptions and individual lifestyles. 3 This term has been used again during the COVID-19 pandemic to point out how it has transformed essential aspects of human life. Cultural theorists argue that there is an interplay between culture and both personal feelings (powerlessness) and information consumption (conspiracy theories) during times of crisis. 4 Nonetheless, it is up to us to adapt to the challenges of current pandemic and similar crises, and whether we respond positively or negatively can greatly affect our personal and social lives. Indeed, there are many lessons we can learn from this crisis that can be used in building a better society. How we open to change will depend our capacity to adapt, to manage resilience in the face of adversity, flexibility and creativity without forcing us to make changes. As long as the world has not found a safe and effective vaccine, we may have to adjust to a new normal as people get back to work, school and a more normal life. As such, ‘we have reached the end of the beginning. New conventions, rituals, images and narratives will no doubt emerge, so there will be more work for cultural sociology before we get to the beginning of the end’. 5

Now, a year after COVID-19, we are starting to see a way to restore health, economies and societies together despite the new coronavirus strain. In the face of global crisis, we need to improvise, adapt and overcome. The new normal is still emerging, so I think that our immediate focus should be to tackle the complex problems that have emerged from the pandemic by highlighting resilience, recovery and restructuring (the new three Rs). The World Health Organization states that ‘recognizing that the virus will be with us for a long time, governments should also use this opportunity to invest in health systems, which can benefit all populations beyond COVID-19, as well as prepare for future public health emergencies’. 6 There may be little to gain from the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is important that the public should keep in mind that no one is being left behind. When the COVID-19 pandemic is over, the best of our new normal will survive to enrich our lives and our work in the future.

No funding was received for this paper.

UNESCO . A year after coronavirus: an inclusive ‘new normal’. https://en.unesco.org/news/year-after-coronavirus-inclusive-new-normal . (12 February 2021, date last accessed) .

Cordero DA . To stop or not to stop ‘culture’: determining the essential behavior of the government, church and public in fighting against COVID-19 . J Public Health (Oxf) 2021 . doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdab026 .

Google Scholar

El-Erian MA . Navigating the New Normal in Industrial Countries . Washington, D.C. : International Monetary Fund , 2010 .

Google Preview

Alexander JC , Smith P . COVID-19 and symbolic action: global pandemic as code, narrative, and cultural performance . Am J Cult Sociol 2020 ; 8 : 263 – 9 .

Biddlestone M , Green R , Douglas KM . Cultural orientation, power, belief in conspiracy theories, and intentions to reduce the spread of COVID-19 . Br J Soc Psychol 2020 ; 59 ( 3 ): 663 – 73 .

World Health Organization . From the “new normal” to a “new future”: A sustainable response to COVID-19. 13 October 2020 . https: // www.who.int/westernpacific/news/commentaries/detail-hq/from-the-new-normal-to-a-new-future-a-sustainable-response-to-covid-19 . (12 February 2021, date last accessed) .

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1741-3850

- Print ISSN 1741-3842

- Copyright © 2024 Faculty of Public Health

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Advertisement

Teaching in the Age of Covid-19—The New Normal

- Testimonials

- Published: 14 September 2022

- Volume 4 , pages 877–1015, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Petar Jandrić ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6464-4142 1 , 2 ,

- Ana Fuentes Martinez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1748-8837 3 ,

- Charles Reitz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7087-086X 4 ,

- Liz Jackson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5626-596X 5 ,

- Dennis Grauslund ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5391-1551 6 ,

- David Hayes 7 ,

- Happiness Onesmo Lukoko 8 ,

- Michael Hogan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6227-0530 9 ,

- Peter Mozelius 10 ,

- Janine Aldous Arantes ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0301-5780 11 ,

- Paul Levinson 12 ,

- Jānis John Ozoliņš ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8819-2526 13 , 14 ,

- James D. Kirylo 15 ,

- Paul R. Carr 16 ,

- Nina Hood ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1798-7385 17 ,

- Marek Tesar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7771-2880 17 ,

- Sean Sturm ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4011-7898 17 ,

- Sandra Abegglen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1582-9394 18 ,

- Tom Burns ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1280-0104 19 ,

- Sandra Sinfield ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0484-7623 19 ,

- Georgina Tuari Stewart ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8832-2415 20 ,

- Juha Suoranta ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5206-0115 21 ,

- Jimmy Jaldemark ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7140-8407 22 ,

- Ulrika Gustafsson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9215-6413 23 ,

- Lilia D. Monzó 24 ,

- Ivana Batarelo Kokić ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8830-6252 25 ,

- Jimmy Ezekiel Kihwele 26 ,

- Jake Wright ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1299-6725 27 ,

- Pallavi Kishore 28 ,

- Paul Alexander Stewart ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6906-8236 29 ,

- Susan M. Bridges ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8325-8397 30 ,

- Mikkel Lodahl ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5750-8927 31 ,

- Peter Bryant ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5667-8633 32 ,

- Kulpreet Kaur ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8028-7889 33 ,

- Stephanie Hollings ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8813-1173 34 ,

- James Benedict Brown ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8917-4565 35 ,

- Anne Steketee ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8595-7909 36 ,

- Paul Prinsloo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1838-540X 37 ,

- Moses Kayode Hazzan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2933-5798 38 ,

- Michael Jopling ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2720-5650 39 ,

- Julia Mañero ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2721-6947 40 ,

- Andrew Gibbons ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0847-5639 41 ,

- Sarah Pfohl 42 ,

- Niklas Humble 43 ,

- Jacob Davidsen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5240-9452 44 ,

- Derek R. Ford 45 ,

- Navreeti Sharma 46 ,

- Kevin Stockbridge ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3859-943X 24 ,

- Olli Pyyhtinen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8522-2515 47 ,

- Carlos Escaño ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8018-2347 40 ,

- Charlotte Achieng-Evensen 24 ,

- Jennifer Rose ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8946-6530 48 ,

- Jones Irwin 49 ,

- Richa Shukla 33 ,

- Suzanne SooHoo 24 ,

- Ian Truelove ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4001-2204 50 ,

- Rachel Buchanan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3594-1110 51 ,

- Shreya Urvashi 52 ,

- E. Jayne White ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1467-8125 53 ,

- Rene Novak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6136-6418 54 ,

- Thomas Ryberg ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1049-8239 55 ,

- Sonja Arndt ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0778-1850 56 ,

- Bridgette Redder 57 ,

- Mousumi Mukherjee ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9251-9165 58 ,

- Blessing Funmi Komolafe ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3248-0681 59 ,

- Madhav Mallya 60 ,

- Nesta Devine ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2535-8570 61 ,

- Sahar D. Sattarzadeh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3487-7455 62 , 63 &

- Sarah Hayes ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8633-0155 39

8483 Accesses

22 Citations

13 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Petar Jandrić , Zagreb , Croatia , 20 June

[Updated biography.] Petar Jandrić is a Professor at the Zagreb University of Applied Sciences, Croatia, and Visiting Professor at the University of Wolverhampton, UK. He is founding editor-in-chief of Postdigital Science and Education journal and book series Footnote 1 . Petar is 45 years old and lives in Zagreb, Croatia.

The ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19’ Trilogy

In 2020, Postdigital Science and Education published ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19’ (Jandrić et al. 2020 ) which is a collection of short testimonies and workspace photographs submitted in the first half of 2020.

In numbers, the collection consists of 81 textual testimonies and 80 workspace photographs submitted by 84 authors from 19 countries: USA (13), UK (11), China (9), India (7), Australia (7), New Zealand (7), Denmark (6), Sweden (6), Croatia (5), Canada (2), Spain (2), Nigeria (2), Finland (2), Ireland (2), Malta (1), Tanzania (1), Malaysia (1), Latvia (1) and South Africa (1). (Jandrić et al. 2020 : 1070)

In 2021, Postdigital Science and Education published a sequel titled ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19—One Year Later’ (Jandrić et al. 2021a ) which is a collection of short testimonies and workspace photographs submitted in the first half of 2021.

In numbers, the one-year-later collection consists of 74 textual testimonies and 74 workspace photographs submitted by 77 authors from 20 countries: USA (14), UK (7), China (3), India (7), Australia (6), New Zealand (8), Denmark (5), Sweden (6), Croatia (3), Canada (4), Spain (2), Nigeria (1), Finland (2), Ireland (2), Malta (1), Tanzania (2), Malaysia (1), Latvia (1), South Africa (1) and Germany (1). (Jandrić et al. 2021a : 1073)

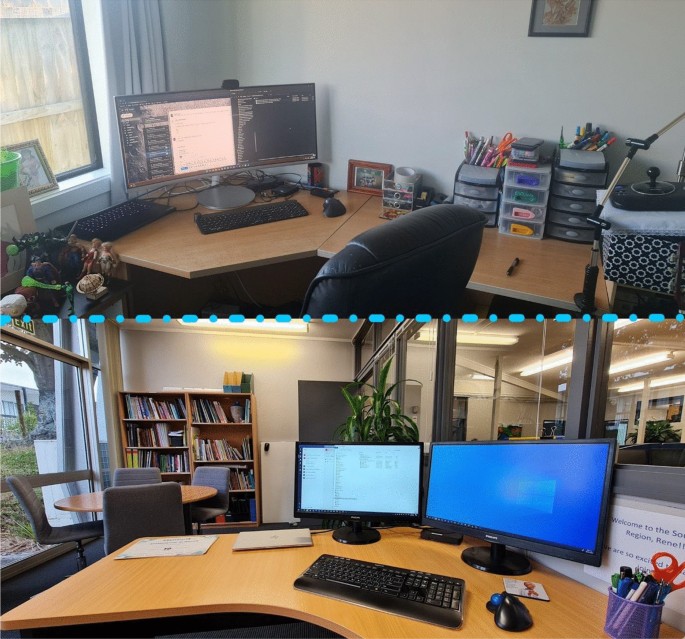

This collection, titled ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19—The New Normal’, is a collection of short testimonies and workspace photographs submitted in the first half of 2022. In numbers, the collection consists of 67 textual testimonies and 65 workspace photographs submitted by 69 authors from 19 countries: USA (13), New Zealand (8), India (7), Sweden (6), UK (6), Australia (5), Denmark (4), Canada (3), China (2), Croatia (2), Finland (2), Ireland (2), Nigeria (2), Tanzania (2), Brazil (1), Germany (1), Latvia (1), Spain (1) and South Africa (1). Some contributors have submitted unchanged biographies; others have experienced various life changes and sent us updates Footnote 2 . Some contributors have told us that their workspaces have remained the same; others submitted images of their new or upgraded workspaces. Footnote 3

Taken together, ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19’ (Jandrić et al. 2020 ), ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19—One Year Later’ (Jandrić et al. 2021a ) and ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19—The New Normal’ make a trilogy consisting of ca 140,000 words and 219 images presented in more than 500 pages.

In each year, the collection has suffered the loss of 6–7 testimonies. Fluctuating between 18 and 20, the number of covered countries has remained fairly constant. The inevitable loss of testimonies was caused predominantly by technical issues such as the loss of contact evidenced by auto-reply messages saying that email accounts are no longer active. Yet the collection is large enough to sustain such losses and allows a longitudinal tracking of 3 years of Covid experiences in about 82 percent of contributors.

Making Sense of the Trilogy

Since the very beginning of our work on the trilogy, we tried to make sense of it. Early articles that discuss the collection directly include ‘Writing the History of the Present’ (Jandrić and Hayes 2020 ) and ‘The Postdigital Challenge of Pandemic Education’ (Jandrić 2020a ). The collection is also explicitly addressed in two Postdigital Science and Education editorials: ‘The Day After Covid-19’ (Jandrić 2020b ) and ‘The Voice of the Pandemic Generation’ (Jandrić 2021a ). We mentioned the collection in many other works yet citing all those would be too abundant.

Probably the deepest attempt at making sense of this material is ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19—A Longitudinal Study’ (Jandrić et al. 2021b ). This article arrives at a few important conclusions worth repeating. This trilogy is important because theory is a powerful anti-pandemic practice and a location for healing. The presented narratives can be read as personal positionality statements, as artwork and as data. Whilst the trilogy is an important historical document, the data-narrato-logy methodology, developed for holistic reading of narratives in these and other ways, can be used for active shaping of our present and future ‘new normal’. Therefore, the trilogy is an important source of information that can be used for development of theories, practices, politics, and policies.

By now, the trilogy has already had a strong direct impact into the global research community. A brief citation analysis shows that currently published articles have been well cited in many different contexts and across all continents. Whilst it is hard to say what the trilogy has inspired in people we do not know, I will now briefly outline ways in which this collection has inspired my own work, the work of some of my closest friends and collaborators, and the work of the Postdigital Science and Education community.

As a graduate of Physics, I never gave much thought to biology. Yet when the early 2020 testimonies started arriving to my Inbox, I felt that we needed to explore it further. I connected with friends and colleagues who had a long-standing interest in these themes and started to explore various aspects of the relationships between biology, information and society (Jandrić 2021b ).

With Michael Peters and Peter McLaren, we published ‘Viral modernity? epidemics, infodemics and the ‘bioinformational’ paradigm’ (Peters et al. 2020a ) and ‘A Viral Theory of Post-Truth’ (Peters et al. 2020b ). With Michael Peters and Sarah Hayes, we further published ‘Biodigital Philosophy, Technological Convergence, and New Knowledge Ecologies’ (Peters et al. 2021a ), ‘Postdigital-Biodigital: An Emerging Configuration’ (Peters et al. 2021b ), ‘Biodigital Technologies and the Bioeconomy: The Global New Green Deal?’ (Peters et al. 2021c ), ‘Revisiting the Concept of the “Edited Collection”: Bioinformational Philosophy and Postdigital Knowledge Ecologies ’ (Peters et al. 2021d ). With Derek Ford, we published ‘Postdigital Ecopedagogies: Genealogies, Contradictions, and Possible Futures’ (Jandrić and Ford 2020 ). Finally, we engaged the community and produced two edited books with over 30 chapters: Bioinformational Philosophy and Postdigital Knowledge Ecologies (Peters et al. 2022 ) and Postdigital Ecopedagogies : Genealogies , Contradictions , and Possible Futures (Jandrić and Ford 2022 ).

Of course, the community has published many more articles and chapters that can be represented in this already borderline self-indulgent list. We also held some dedicated events in places from O.P. Jindal Global University in India to the University of Wolverhampton in the UK. Yet this list is not aimed at providing a detailed account of our writings or activities; it is here to outline some direct and indirect bifurcations developed from the collection, as well and some ideas and personal connections, to show the extent of the collection’s wider impact.

What Is Next?

The ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19’ trilogy is a testament of three specific historical moments. Written at the heat of the first wave of the pandemic, ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19’ (Jandrić et al. 2020 ) is marked by looming emotions such as uncertainty, fear and hope; workspaces are improvised dinner tables, bedrooms and closets. ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19—One Year Later’ (Jandrić et al. 2021a ) shows the first signs of fatigue and normalization. Emotions are deeper; workspaces are tidier and more ergonomic. In ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19—The New Normal’ people are sick and tired of the pandemic; disappointed that the new normal is so surprisingly like the old one. New challenges emerge (such as the war in Ukraine); workspaces go back to pre-pandemic classrooms, airports and so on. The main message from ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19—The New Normal’ is abundantly clear—the time to develop the new normal is now.

It was great to meet all the authors, it was great to produce this material, yet it is my feeling that the ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19’ trilogy has arrived at its inevitable end. I do take note of Thomas Ryberg’s warning that ‘from popular culture we know that trilogies suddenly expand with prequels, sequels etc.’, and I will not make a firm promise to stop here. However, I would need a very good reason to start another sequel. Unless the world suffers another large pandemic outbreak, perhaps of a new variant of the virus, I cannot see the need to continue in this format. However, that does not mean that our work has ended.

Reading the complete trilogy, I can finally see the materialization of my early-2020 vision. ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19’ is a historical document, a good read, a hub for making new connections, a brewery of new ideas. It is an important source for development of new theories, practices, politics, and policies—or, in one phrase, a ‘new normal’. Now that the third and final part is published, I give my warmest thanks to all contributors and invite the scholarly community to actively use the ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19’ trilogy in shaping our present and future.

Call for Testimonies: Teaching in the Age of Covid-19—The New Normal

This is a verbatim transcript of the Call for Testimonies sent out on 29 March 2022 to all authors of ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19’ (Jandrić et al. 2020 ) and ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19—One Year Later’ (Jandrić et al. 2021a ).

On 17 March 2020, Postdigital Science and Education launched a call for testimonies about teaching and learning during very first Covid-19 lockdowns. The resulting article, ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19’ (attached), presents 81 written testimonies and 80 workspace photographs submitted by 84 authors from 19 countries.

On 17 March 2021, Postdigital Science and Education launched a call for a sequel article of testimonies about teaching and learning during very first Covid-19 lockdowns. The resulting article, ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19—1 Year Later’ (attached), consists of 74 textual testimonies and 76 workspace photographs submitted by 77 authors from 20 countries.

These two articles have been downloaded almost 100,000 times and have been cited more than 100 times. This shows their value as historical documents. Recent analyses, such as ‘Teaching in the Age of Covid-19—A Longitudinal Study’ (attached), also indicate their strong potential for educational research.

As the Covid-19 pandemic seems to wind down, pandemic experiences have entered the mainstream. They shape all educational research of today and arguably do not require special treatment. Yet, our unique series of pandemic testimonies provides a unique opportunity to longitudinally trace what happens to the same people over the years—and this opportunity should not be missed.

Today, we launch a call for final sequel: Teaching in the Age of Covid-19—The New Normal. In this sequel, we would like to hear about ways in which you—contributors to the previous articles—have established your own new normal. We hope that this will be the last iteration in this series of testimony articles. Unless the world faces another strong pandemic outburst, we would like to end the series with this last article. Your 500-word contributions should contain roughly the following:

Before you begin:

On top of your submission, please write your name, location and date of writing your submission in the following format: Petar Jandrić , Zagreb , Croatia , 1 June .

Please update your biography published in the original article. If you do not update your biography, we will reproduce last year’s one.

Then, please cover the following themes:

What is your experience of the return to your physical workplace/establishment of a new, blended work format?

Which main lessons did you (and your employer) draw from the pandemic experience?

Which main transformations have happened in your work and private life?

Which major challenges (professional, private, personal, family…) are you finding along the way?

What are your main feelings at the moment (stress, anxiety, excitement, happiness, calm…)? How are you coping with those feelings?

How has your thinking about the Covid-19 pandemic developed during the past year?

And, of course, anything else you would like to tell the world about your experience.

Last but not least, please send us a photo of your current workspace!

This Call is aimed only at co-authors of Teaching in the Age of Covid-19 and Teaching in the Age of Covid-19—1 Year Later articles! Please do not share this Call or invite new co-authors. Those of you who wrote collective replies, please try and replicate your original author setup.

Please write your ca 500-word response and return it, together with a photo of your current workspace, to Petar Jandrić, [email protected]. Responses will be collated into a collectively authored article and prepared for publication in Postdigital Science and Education, 4 (3), October.

Deadline for submitting your responses is 5 May 2022. Please contact Petar Jandrić for any questions.

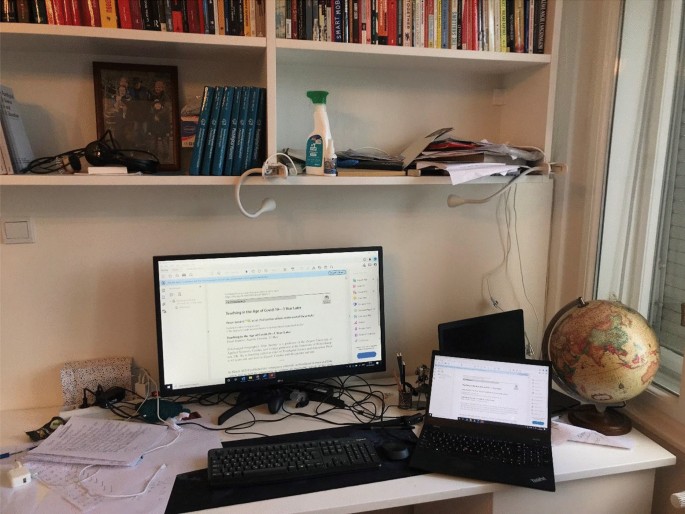

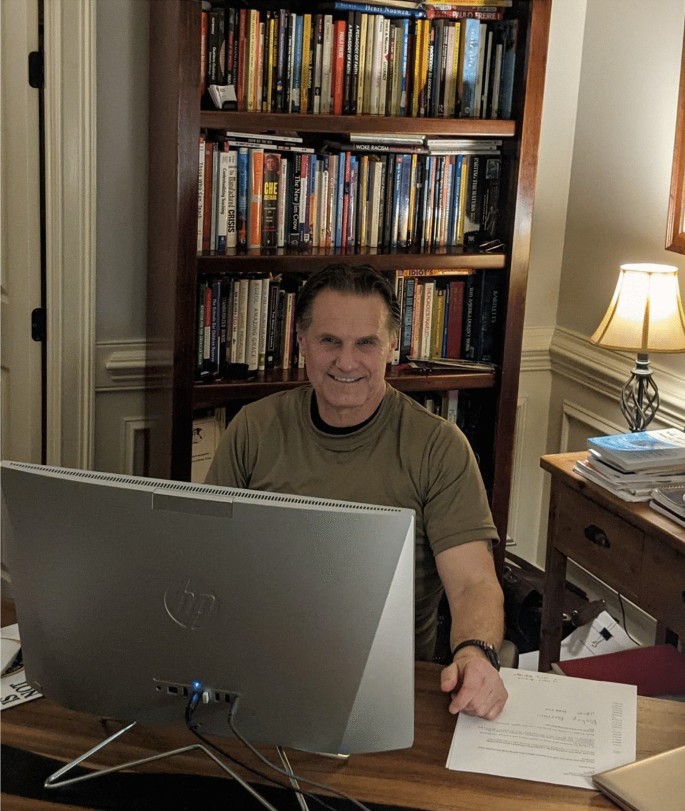

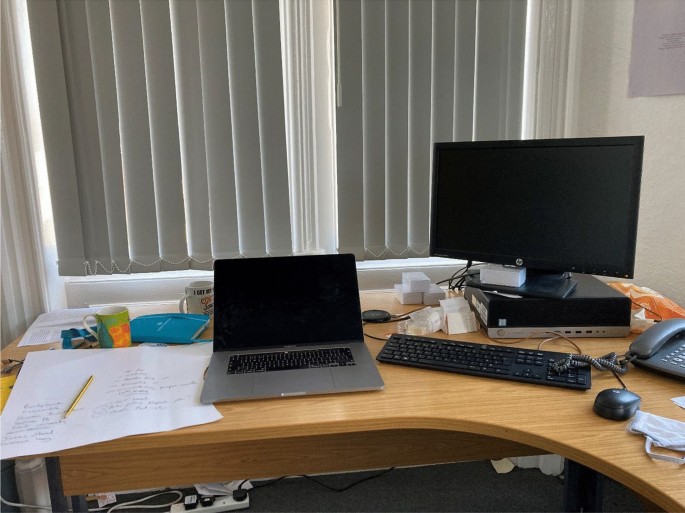

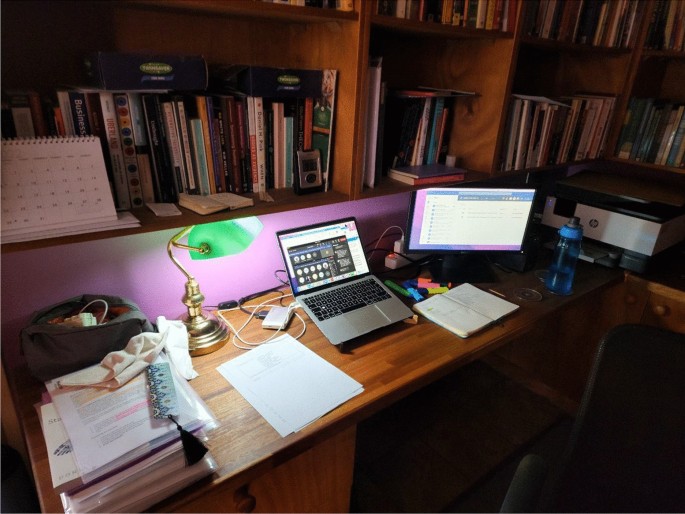

Fig. 1 [New figure] My home workspace, where I wrote the Call for Testimonies. The university is open; I was at home because it was raining, and I didn’t feel like getting wet

Party in the Hermit Kingdom

Ana Fuentes-Martínez , Lund , Sweden , 29 March

[Unchanged biography.] Ana Fuentes-Martinez was born in A Coruña, Spain, in 1975. She is a mathematics and computer programming teacher at Katedralskolan in Lund and a researcher at University West, Sweden. Her investigations concern integrating mathematics and programming from the perspective of teacher professional development.

Back in the old normal, Swedish universities were already struggling in their efforts to have more teaching staff working at their offices rather than from home. The flexible hours and the lack of supervision made the choice easy for those who had other concerns to reconcile—childcare, doctors’ appointments, a company on the side. This arrangement put a strain on the remaining staff on campus, who found their time scattered catering to students other than their own, taking in assignments and solving floor-shop problems. To mitigate this problem, some departments went as far as granting presence-bonus for teachers who were at their offices a minimum of 2 days a week, which was compensated with reduced teaching duties. Working from home was not discussed overtly but it was nevertheless a reality that reverberated in the walls of many empty campus offices.

When the Covid-19 hit pandemic levels, working from home was the first option for all of us who were able to do so. Two years later, the old question of who is at campus and who is not has proved to be still highly relevant and problematic. The departments are luring with cake and celebrations to attract employees back to their desks, but they are still hosting online or blended meetings to promote attendance. The necessary technology is now commonplace and it seems petty to restrain its use for the sake of interaction in the physical workplace.

The threshold for participating in physical gatherings is in many ways higher than it was before. We have less tolerance for colleagues or students turning in with even the mildest of symptoms. Commuting is dire, with gas prices hitting new records and public transportation still holding back some of the old lines. In many cases, working from home has become the default and there needs to be a good reason to attend campus. This has exacerbated the problem of empty offices and forced flexible solutions: work landscapes without designated desks, functional spaces to accommodate collaborative work, and technical equipment to allow for physical meetings with online participants.

This new workplace setting has also had repercussions on the ways that students interact with campus staff. We have gotten used to sending emails rather than popping by which makes questions and suggestions better prepared but possibly scarcer (Fuentes Martinez 2022 ). At the same time, the boundaries between the private sphere and the working place have become blurred, particularly in an information-intensive field such as teaching and research. Being out-of-office is no longer a valid excuse for delaying a prompt answer since the office has ceased to be the place where answers reside.

As the workplace and its workers are reinventing their mutual necessity, social gatherings are gaining importance to catalyse fruitful meetings and spontaneous work collaborations. We need also to reinvent the sense of belonging that the physical workplace once enacted and replace it with activities and participants, with common goals and shared responsibilities.

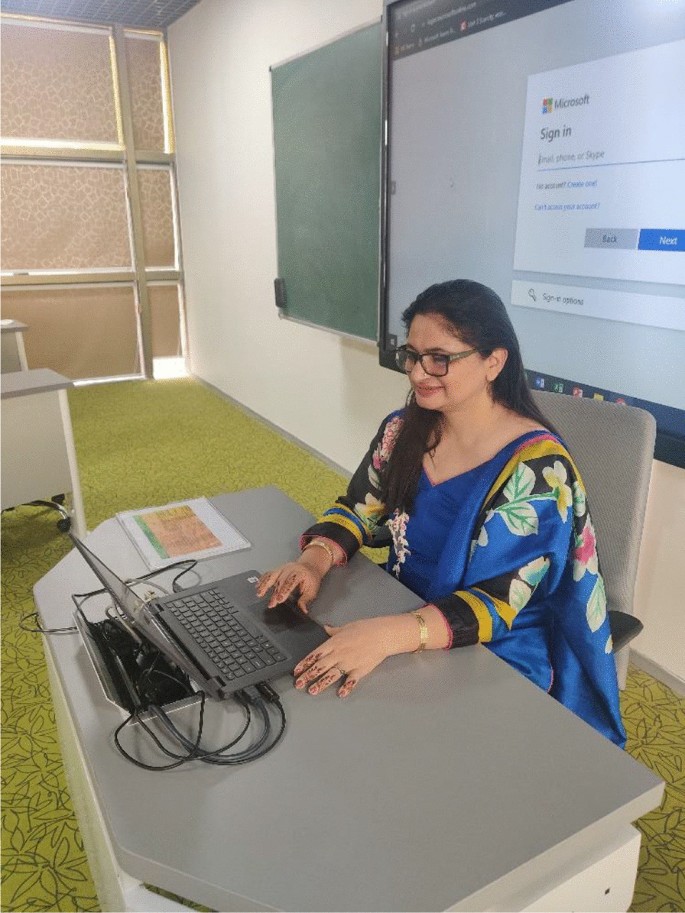

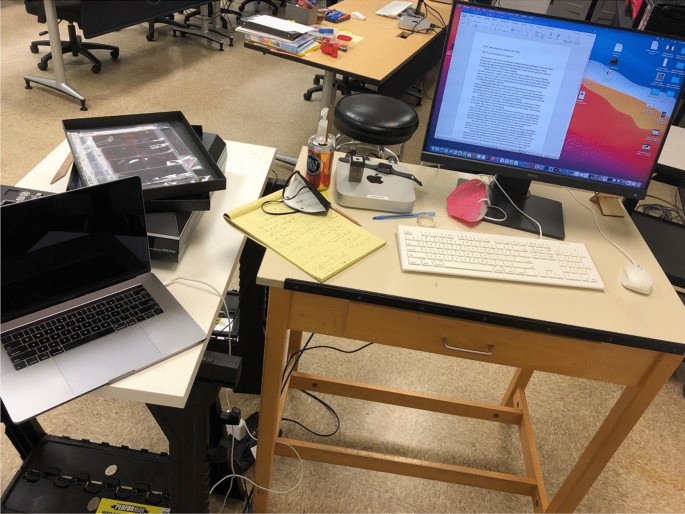

Fig. 2 [New figure] My home workplace in the former walk-in closet is a little bit tidier now as paper heaps are replaced with digital documents, and a little bit cosier with new blinds. My desk at campus has vanished as such, and I am welcome to plug my computer to any free dock station when I work there

Dialectic of Renewal and Resignation

Charles Reitz , Kansas City , MO , USA , 29 March

[Unchanged biography.] Emeritus Professor of philosophy, Kansas City Kansas Community College, with four recent books: Crisis & Commonwealth: Marcuse, Marx McLaren (2015), Philosophy & Critical Pedagogy (2016), Ecology & Revolution: Herbert Marcuse and the Challenge of a New World System Today (2019), and The Revolutionary Ecological Legacy of Herbert Marcuse (2022).

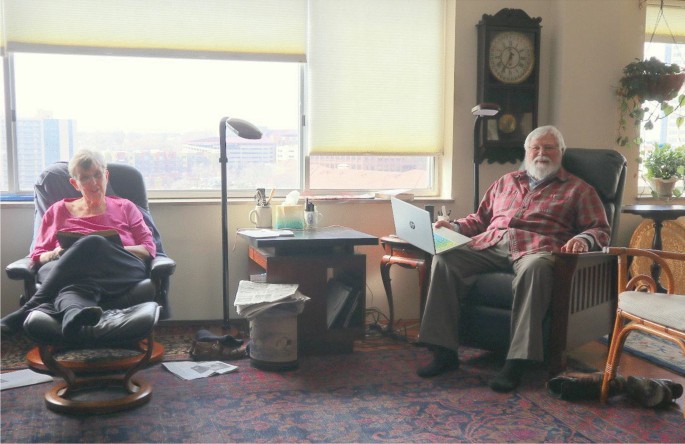

March 2022 is the anniversary of my 30-day hospital stay with Covid-19. I have recovered. The federal government picked up all my costs. Retired from teaching when Covid-19 hit, I have been writing and publishing. I continue this work (Reitz 2021 ) post-Covid from home: in an easy chair in our living room where I sit with my laptop near my wife, also a retired professor who is constantly reading. We have a study where most of our books are kept and where we connect remotely to colleagues or attend events via Zoom and/or print downloaded documents.

Resignation

Our daughter is an upper-level administrator at an R1 research university in another state. She has been under great stress because she and her team have been in charge of helping her university’s professors across all disciplines gear-up for remote teaching. The duress has caused her to consider leaving administration and to return to her tenured position in a humanities department where her workload would be more manageable.

On a recent visit to our daughter’s home, I picked up an academic journal she was reading, Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature , Language , Composition , and Culture (October 2021, Volume 21, Issue 3) Footnote 4 . Two articles on the new powers of postdigital undergraduate teaching struck me in particular. One supported writing skill development through online annotational exchanges amongst the students in the class and the instructor. This is a method entirely postdigital and fully suited to pandemic precautions. The second article reported on coupling student curiosity to an informal browsing of an actual digital research archive. The students used digital finding-aids to access digitized primary source materials and do authentic informal research.

The Great Resignation ( See Thompson 2021 )

The Covid-19 crisis unveiled the essential role of labour in society. Truck drivers, grocery stockers, cashiers, medical professionals and teachers are crucial. The growth in income of society’s upper echelons of privilege however has been dramatically out of proportion to the reductions in income experienced by nearly everyone else. Over-accumulation has sapped labour, perhaps more than Covid-19. Economic expectations are continually being leveled down, and workers are increasingly being treated with oligarchic disdain as expendable in teaching and elsewhere. This has brought a Legitimation Crisis with regard to the meaning of work and our teaching. It is also occurring at the expense of planet earth: wealth extraction and profitable waste doing damage to air, water, and soil quality.

The demise of the system is occurring, including the melting away of the veneer of democracy in the heat of a new neofascist white nationalism. War in Ukraine portends even worse. Our dilemmas of alienation, ecological challenge and peace have their political economic foundations. So does our collective power.

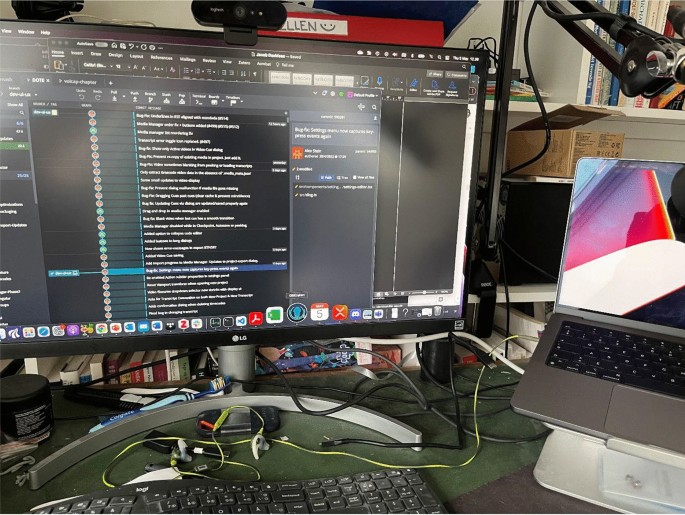

Fig. 3 [New figure] Retired professors Charles Reitz and Roena Haynie have been working from their apartment’s eighth floor sitting room for the past 10 years

Weary from the Past, Hong Kong

Liz Jackson , Hong Kong , China , 30 March

[Updated biography.] Liz Jackson is Professor and Head of Department of International Education at the Education University of Hong Kong. She is the former Director of the Comparative Education Research Centre and a Fellow and Past President of the Philosophy of Education Society of Australasia. Her recent books include Contesting Education and Identity in Hong Kong (2021), Beyond Virtue : The Politics of Educating Emotions (2020), and Questioning Allegiance: Resituating Civic Education (2019).

Two years ago, Petar Jandrić invited me to write about teaching during Covid-19. I titled my piece, ‘Weary from the Future, Hong Kong’ (Jackson 2020 ). Here, we had been experiencing a protest movement (over extradition and national security bills) for the last year. It boiled over in December 2019, whilst I was planning for an ill-fated Philosophy of Education Society of Australasia Annual Conference. We were already locking down and teaching online. By April and May that year, it was shocking to see weak western responses to Covid-19, oblivious to the situation in Asia, where success was tied to masking, isolating and tracing.

A year ago, I was invited to reflect again. My response was hopeful. I had changed jobs, gotten promoted, moved flats, adopted kittens. I missed travelling; Hong Kong is about the size of New York City, so government mandates discouraging flying with 21-day (self-funded) hotel quarantines upon arrival. Forced hospital stays for those returning positive were vexing. However, I was, all things considered, facing each day happily, and settling into routines, including intermittent lockdowns, still working mostly from home, teaching online.

Now Hong Kong has been amongst the first to face Covid-19 and may be amongst the last. Whilst the rest of the world shifts gears, our lockdown worsens. I have been to campus or a restaurant five times in the last 6 months. For months, I did not leave the flat, except to run, after the government needlessly killed 2000 hamsters and rabbits after a (human) outbreak tied to a pet shop (Leung 2022 ). The government locks down buildings with any cases or contacts, moving people (positive or not) into quarantine camps for weeks. I have worried about our cats since then, considering events in the mainland (Yan 2022 ).

The National Security Police have taken over the Covid response. They arrest or fine anyone who dares to remove their mask whilst jogging in the forest, to associate with more than one other person in public or to resist going to hospital or quarantine (positive or not). It would be better if it worked. Officials still have unmasked parties of hundreds (Chau 2022 ). Elderly deaths skyrocketed, whilst asymptomatic patients were handcuffed in queues outside jam-packed hospitals during cold nights (Romero and Lai 2022 ). Yesterday, an official promised us a merry Christmas if we could follow the rules (Hong Kong Economic Times 2022 ). Meanwhile, the government thanks the mainland for tens of thousands of camps which are ready for a sixth wave, with mainland-style electrical sockets and squat toilets (Lee 2022 ), paid for by Hong Kong.

Most of my friends have left for good last month, when the government announced a universal testing plan, whilst children are separated from their parents if positive (Sun 2022 ). As February was declared summer holiday and school was cancelled, apparently to make way for more quarantine facilities, our student teachers now make videos for their school practicums. When I meet with students on Zoom, I remind them to be cautious around contact tracing, and never tell any police about their pets. As the student population dwindles, so does my department, which has seen several resignations since I became its head 2 months ago. At the same time, university democracy walls and other symbols and student unions have been uprooted and banned across the region (Leung 2021 ).

For 3 years, Hong Kong has been suffering. I remain in the eye of the storm, at home with my partner and two exceptionally spoiled cats.

Fig. 4 [New figure] Enjoying a partial sea view from the office with Geng, one of my two Covid boys, who is almost 2 years old

Dennis Grauslund , Aalborg , Denmark , 30 March

[Updated biography.] Dennis Grauslund is now a Senior Lecturer at University College of Northern Denmark, Denmark. Dennis is 32 years old and still lives in Aalborg, Denmark, with his partner and two children. In the past year, his family has had Covid-19 once.

As I write this testimonial, I am sitting at my desk in my campus office. Society is fully open and has been so for months. In the office with five desks, three are occupied. When looking outside the window, the sky is blue, and spring has arrived. It has been good to return to our physical workplace; it has been a positive experience to see colleagues and students again and discuss different matters in person rather than online. It is something that is appreciated, especially by my students. We have drastically scaled back on virtual meetings and lectures because we found it important to ‘reconnect’ in person. That said, we tend to have one or two colleagues attending meetings virtually that they otherwise would have declined to participate in due to time constraints, etc. Also, we have seen a decrease in class attendance, the reasons given often being worries or symptoms of Covid-19.

However, have we indeed reconnected as colleagues? I am not sure. It takes time, and we all have to make an effort to get to know one another again. That is a challenge, as one of the significant transformations is a shift in how people work; much more is done from home. Today, out of 16 people, only 8 are present. Four of these are teaching or having exams, so we are 4 people in 2 different offices.

One of the major challenges I find is coping with feeling disconnected. Not only from colleagues and what exciting projects might be underway but also from the industry. One of the ways I stay connected is by attending practitioner conferences to network and learn more about the challenges they face and understand how we can make a positive difference in the industry. This has been immensely difficult as most conferences have been cancelled. Another major challenge is the feeling that my professional development has hit a stagnation point, not because I wanted to stagnate, but because the main focus has been on ‘surviving through a pandemic’ and ‘managing students’ feelings and their feeling of disconnection’.

I am both excited and nervous about the future. I see some great changes in how we work, i.e. increased flexibility; however, the same flexibility poses challenges, as it can contribute to the feeling of disconnection. We have been back in the office more or less since August 2021, but my feelings of disconnect have not changed considerably. Will they ever change? Luckily, I can always count on the support of my partner; she has been supportive, especially during the past few months where I have had a less than positive period; perhaps some winter blues?

My thoughts on Covid-19 have changed in the past year. I have been worried and anxious from the beginning of the pandemic. However, the evolution of Covid-19 to more gentle variants has toned down my worries and the fact that most Danes have been vaccinated multiple times now. I am still concerned about the long-term effects of Covid-19 as studies suggest a significant number of people continue to struggle with the after-effects of the virus.

If this is the ‘new normal’, I hope to see another new normal soon, in which we will all be connected once again.

Fig. 5 [New figure] My desk at my campus office, with all the handwritten notes and articles that I need for the day. The picture is taken in the morning

Volunteering and Covid-19, the New Normal?

David Hayes , Further Education , Worcester , UK , 30 March

[Unchanged biography.] David Hayes felt privileged to teach for over 30 years. He found those he taught, and taught with, more interesting than his subject. That subject was often mathematics. Originally from Scotland, Dave enjoys life in Worcester, UK, with an all-too-observant partner, two sons, and a disrespectful cat called Jasmine.

I have stated previously, that as a retired Maths teacher, I enjoyed the experience of providing some volunteer support for students. The support given at local schools and colleges was generally face-to-face and it was provided to either individuals or to small groups. It tended to be low-tech support, often paper based, and it usually complemented other provision. Perhaps the key thing about that period of volunteering was that it was all pre-Covid-19 .

I had assumed that at some point I might return to such volunteering. After all, it is an intrinsically rewarding activity and I believed, with good reason, that there would be a need for experienced volunteers. There had been something of a hiatus in children’s Maths education and the Government had promised funding for tuition: funding indeed that I would neither need nor would wish for.

Armed with a fairly positive attitude, a printer, and a supply of stamps, I sent out letters to ten local schools and colleges, stating my position. That position was of being a retired teacher, who wished to give some hours of volunteering each week. If I had anticipated that I would get few replies, then I was not to be disappointed. I received just one that commended me for my public spirit .

Shortly afterwards, I travelled to the particular school, where we had a genial discussion about what I could offer. I stated that I would be happy to commit to any whole day each week, of their choosing, provided I could be informed about which weekday it would be in advance. This would permit me to factor in certain caring responsibilities. Whilst awaiting details about the appropriate Disclosure and Barring Services (DBS) check for such volunteering, I received a further email stating that they would not be able to use me because ‘I was not flexible enough’. I have made overtures to other places but with less persistence. I have decided to leave matters there, since it seems unwise to run after those who may not want me around.

What lesson, if any, have I learned? From my own experience, I know that teachers work hard and that they tend to be a dedicated bunch. I am in no doubt that there is a post-Covid-19 need to harness experience, just as there is an expressed will from the Government to do so. Despite all such good and proper feelings, there is a persistent doubt within me as to whether such public bodies are set up properly to use volunteers effectively. One may argue that it is not their job to do so, that volunteering should be the preserve of the Charitable Sector. I see no reason why this should be so, particularly when the last 2 years furnishes us with such obvious needs. If there is to be a New Normal , then let us make sure that it is inclusive and that it works for the benefit of those learning.

Fig. 6 [New figure] Past and present

The New Normal Education System

Happiness Onesmo Lukoko , Dar es Salaam , Tanzania , 30 March

[Unchanged biography.] Happiness Onesmo Lukoko is a part time Assistant Lecturer in the Institute of Development Studies at University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM). Happiness is 27 years old and lives in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

The pandemic affected every aspect of our lives, including our plans and daily routines. Because we were not under lockdown in Tanzania, we are continuing to work at our physical workplaces as usual. Since the outbreak, we have all been advised to take precautions like wearing masks, keeping a safe distance and washing our hands frequently. Our new work approach is to continually encourage our children and the community to take measures, with the government emphasizing the importance of immunizations. The most significant lesson we learned from the pandemic, in my opinion, is the importance of practicing preventive measures against any infectious disease. Wearing masks and washing hands help prevent the spread of the virus.

The epidemic ushered in a new era of online and hybrid learning across a variety of platforms. The emphasis on the use of information communication technology (ICT) has been a major transformation in my work. The use of ICT has been promoted by the university so that in case of another outbreak we will be ready to switch to hybrid learning. Workers are given masks and sanitizer and there are washing stations in each class.

Most of my activities, such as meetings, require me to be online the majority of the time. One of the most significant professional issues, in my opinion, is the loss of personal touch with students and colleges as a result of social distance measures. The most difficult personal task is figuring out how to spend time alone.

At the present, I am happy and tranquil because I am following all recommendations of health experts. I eagerly await the opportunity to reconnect with my international friends. I miss the days when you could simply fly to another country without limits, go on field trips with your pals, chat about life and have fun.

I think it is still possible to go back to a new normal by taking precautions and being optimistic. It is important to take care of ourselves, especially our minds and our attitudes, because everything begins with ourselves. The mind is a very powerful tool that can build or destroy people. Since the emergence of Covid-19, numerous frightening news have been broadcast to the public, causing stress and affecting people’s mental health. Negativity can ruin our thinking and I think it is important to feed our minds with positive ideas. Because we learn how to live every day, I believe it is crucial to keep calm and follow all measures recommended by specialists.

Fig. 7 [New figure] This is my workspace in my apartment where I conduct my online meetings and other online activities

The New Normal—Making the Most of It

Michael Hogan , Galway , Ireland , 30 March

[Unchanged biography.] Michael Hogan is a Lecturer at the National University of Ireland, Galway, where he teaches Social Psychology, Positive Psychology, Critical and Collaborative Thinking and Applied Systems Science Design Methods. Michael is 48 years old, and lives in Moycullen, Galway, with his wife, Vicky, also a Lecturer at NUI, Galway, and three children, Siona, Oisin and Freya.

The day after tomorrow will see the arrival of 1 April 2022, and yet 12 March 2020, when we were first forced online by the Covid-19 pandemic, seems like only yesterday. Time perception seems to have changed for many people, including myself, and yet so much has happened during these past 2 years. Reflecting on the experience and lessons learnt is valuable, not only because it qualitatively expands and deepens one’s time perception but, more importantly, because it allows the transformation and development derived from life experience to be perceived and properly appreciated. In this way, I’m grateful for this opportunity to reflect again and contribute to this collective paper.

In relation to our return to the physical workplace and face-to-face in-person teaching, the initial experience last September reminded me of an experience I once had meditating, many years ago, when I was deep into the practice of martial arts. Upon returning from a deep meditative state, where I had ‘vanished’ and experienced myself only as white light, I recall to this day the very first ‘intention’ I experienced. The ‘intention’, in that swift returning from no-mind to mind and body, had immense power and it revealed to me the essential power of intentions as they arise in consciousness and manifest in action.

Upon returning to our School of Psychology building that first day in early September, I experienced a similar feeling and associated sentiment in relation to the raw power of physical connection with others and the shared spaces we occupy. Whilst it was optional to return to campus and teach in person last September, and whilst we still connected with many students online whilst simultaneously teaching other students in person, I did not hesitate to return ‘to the room’ and share the space with students. We all struggled a little with facemasks and breathing and talking, and we all had to get used to only seeing one another’s eyes, with no mouth on display; but on balance, it was by far the preferred option for me and many students at the time.

We all experienced this ‘new normal’ differently, but it was notable and deeply valuable to recognise again—as if we had somehow forgotten—the essential, raw power of physical connection. Many of us thrive on this physical connection as teachers, we need it and we appreciate it, and students need it and appreciate it, too.

More generally, it was a collective appreciation of togetherness that was the dominant feeling in the classroom, certainly as I experienced it; and this was coupled with a new appreciation of learning together. Indeed, I was surprised and delighted to see so many students turn up to class—we were like magnets drawn to one another and our shared learning experience, and student performance and engagement, was truly excellent this year. Perhaps the main lessons that many people, including myself, have drawn from the pandemic centre around the fundamental truths of being human, including our need to connect and learn from one another, both of which are foundational for the very existence and purpose of Universities.

At the same time, things have changed, our practice of connecting with one another has changed. Now that we are back ‘in the building’, teaching, doing research and supporting ongoing administration and management of our units, we now connect in a variety of different ways and, of course, we see the value of sustaining many of our new online skills—meeting, teaching, facilitating online as needed, supporting those who cannot be physically present when the rest of us are. We have many new tools we can use, new ways of cooperating and coordinating our actions, and we’ve got better at connecting with one another online, even if this ‘getting better’ often simply means just ‘being ourselves’—the good, the bad, the tired, the inspired, the stressed, the over-excited and not altogether-working-so-well in the audio-visual digital space. All the great variation of human behaviour and experience that plays out.

Perhaps my sense personally is that I’ve become more comfortable with ‘being myself’ online and I expect nothing else from everyone else, only that they are free to be themselves. This perhaps reflects a deeper feeling that is shared by many—we have all been through, and we continue to live through, a very difficult time and we need to go easy on one another, accommodate and be flexible and do the best we can.

My main feelings at the moment are a mixture of reflective and appreciative and particularly tired, as we approach the end of teaching this week. I look forward to our in-person presentations in class tomorrow, where our system design students will get a chance to showcase the products of 12 weeks of intensive work together. The dominant reflective stance at this point also derives from awareness of the uncertainly of our current work status. We may well experience another wave and new strains the virus that break through our booster vaccines and force us to work again completely online. My hope is we will continue to adapt and perhaps better master the flexibility required, and further our fundamental bonds of solidarity, friendship and learning which have sustained us and which will serve us well if another radical behavioural shift is required.

I am very proud of my students, and year on year it grows. I think they know it. Perhaps I should say it more often, but then again, they know me and I know them; we focus on the work—we focus on learning together and getting out alive. I find it an increasingly humbling experience to serve them, particularly now as I get older and recognise that my time in this role is limited. This appreciative feeling also derived from a deeper realisation that I may not live much longer, and I accept that. This abiding sense of my own mortality provides perspective. I am here to serve, and I have few other concerns in life.

I am deeply proud of my three children and the way they have adapted through all the phases and stages of change, learning online and learning more about what it means to be a family, with their Mum and Dad, and learning to appreciate their community and all the good things that a good community brings. Again, much like last year and the year before, I close by saying we are still very much in medias res , in the middle of things: doing, adapting, working to get ‘over the line’. And yet again, I am not sure where that line is exactly. I just focus on the job at hand and I continue, in my own quiet way, to appreciate all the wonderful compassion, cooperation, creativity, solidarity and collective strength I see all around us every day. We will continue to teach, and we will continue to work hard—there is much to learn and much to do.

Fig. 8 [New figure] This is my workspace in the upstairs box room. It has not changed since last year. Vicky is in the new room downstairs. We are sometimes here and sometimes ‘in the building’ on campus. The kids are now back at school

The New Normal—Keeping the Best Practices Initiated by the Pandemic

Peter Mozelius , Stockholm , Sweden , 31 March

[Updated biography.] Peter Mozelius is an Associate Professor and Senior Lecturer at the Mid Sweden University in Östersund, Sweden. After that the pandemic broke loose in March 2020, Peter has worked by distance, from his home office in Stockholm for more than 2 years now.

In my new normality, I have not returned to the physical workspace at the university campus in Östersund. I still carry out the vast majority of my work from my home office in Stockholm, but for staff gatherings and department conferences I take the train up to Östersund for face-to-face activities. The main reason for continuing to work by distance is the excellent results with an increased delivery both for teaching and learning activities and for research.

Regarding the teaching, courses have shifted from blended learning with face-to-face sessions to blended synchronous learning with collaborative group activities online. Most of the synchronous activities are conducted in so called breakout rooms in the video conferencing tool Zoom. In programming courses, the outcomes have been better compared to when the same workshops were given face-to-face in active learning classrooms. The most positive surprise for programming courses is the good focus at full-day online gatherings. As an example, the introductory course starts with a ‘coffee & chat’ at 9.30 am followed by lectures, workshops, ensemble programming between 10 am to 4 pm. Important of course to have a lunch break and some shorter coffee/tea breaks as well, but the surprise is that some course participants stay on in Zoom after 4 pm for extra support and discussions.

Thesis supervision has worked out well, but with a need for different data collection methods during the pandemic. The quality of completed theses are about the same as before the pandemic, but sometimes with feelings of loneliness for thesis writers, especially the ones with only one author. Online seminars in the Zoom environment have worked well for the technical parts of the supervision and for the final seminars. Regarding my research, I have around 35 publications during the pandemic, which is more than for the same timeframe before the pandemic. The writing has been more focused, but research design has been a bit different. More literature studies and email interviews than earlier.

Research collaborations have worked well online, but I strongly miss the networking at traditional conferences. Virtual conferences could probably be improved and developed further, but we really need to meet face-to-face sometimes. Regarding my personal life, I feel healthier now than before the pandemic. The time that I spent on train travels earlier between Stockholm and Östersund have been used for more pleasant activities. I often go for jogging rounds on the lunch break, and I have eaten healthier food during the pandemic. A positive side effect is that I am better at cooking than before the pandemic. However, the lack of cultural events was boring, and I am really looking forward to attending live music sessions and theatre again.

To conclude, the new normality is a good normality. The best practices initiated by the pandemic should be kept, but it would be a great relief if we are now really experiencing the last phase of the Covid-19 era.

Fig. 9 [New figure] My home workplace

Janine Aldous Arantes , Melbourne , Australia , 4 April

[Updated biography.] Dr Janine Aldous Arantes is a Research Fellow with the Institute of Sustainable Industries and Liveable Cities (ISILC) and Lecturer in the College of Arts and Education, Victoria University, Australia. Janine is 47 years old and lives in Melbourne, Australia, with her husband and two sons, but—since the last iteration, unfortunately, our Kelpie passed. We now have a nine-month-old Golden retriever, who is gorgeous.

The ‘new normal’ for me is not exceptionally different. Well, in terms of working conditions at least. I remain working from home, although there is an expectation that we are back on campus. My physical office at the university is there, but I don’t expect the establishment of a new, blended work format until 2023. This is because all my classes for 2022 are formatted as online and remote delivery. Although there is an anticipation that I will be on campus from my employer, my particular situation means that this has not been enacted for me yet.

This flexibility allows the execution of significant learning from the pandemic lockdowns. Working from home (for me) is a matter of increased productivity. The removal of commuting means that I have a greater output. The removal of walking between classrooms means that I am more efficient. This transformation means that I am more focussed. In terms of private life, it also means that I don’t take time off work to meet the isolation regulations. Working from home (arguably, for my employer and me) is much better.

With all opportunities come challenges. But I would suggest that we have yet to experience the challenges of some being face-to-face and others working from home. For example, will we soon share an academic form of ‘us’ and ‘them’? Will those working face to face on campus have more significant interaction and impact on academic work and promotion opportunities? Will those working from home publish more? Will students opt for more flexibility or the relational characteristics of being on campus? My thoughts are that answers to these questions will be context-dependent. Perhaps the Masters students would like the flexibility too? Maybe the Bachelor students might enjoy the on-campus experiences? Either way, this transformation brings a constant state of ‘not knowing’. Coping with these feelings is left to leading, managing, and facilitating what I have control over whilst also keeping an eye on transformations I cannot control.

My thinking about the Covid-19 pandemic during the past year has significantly shifted. I was worried about data, profiling and privacy—and now I seem to have resigned myself to forms of algorithmic governance as part of the new normal. I do not seem concerned about corporates collecting and using my data now—I guess I have metaphorically drowned in the massive pool of information I have given away due to Covid-19 online and remote teaching. And, I do not seem to want to come up for breath. Instead, I am swimming in this pool and constantly looking for the good (arguably at the expense of my privacy). There are too many people around me, who are still struggling to keep their heads above water—in terms of climate change and wars. So, I guess I am wading in this pool because I have to. I have to find ways to make this new normal great. And in many ways—it is.

Fig. 10 [New figure] We moved three times during the pandemic, and this is now my office. It is shared with the laundry but is light, bright, and private. Teaching online, with three others working in the house, meant we needed a room each—and this has worked out wonderfully. Our Goldie sits at my feet most days, and I am home when our children return from school every day

The Enduring Benefits of Online Education

Paul Levinson , White Plains , NY , USA , 7 April

[Unchanged biography.] Paul Levinson has published 10 books about media theory (e.g. The Soft Edge , Digital McLuhan , New New Media ) translated into 15 languages and 6 science fiction novels (e.g. The Silk Code , The Plot to Save Socrates ), and is a singer-songwriter ( Twice Upon a Rhyme , Welcome Up : Songs of Space and Time ). He is a professor at Fordham University in New York City and appears on CNN, MSNBC, NPR, the BBC and numerous news outlets.

I began teaching once again in person at Fordham University in September 2021 with a mixture of trepidation and exhilaration. Even though I and all of my students had been thoroughly vaccinated and wore masks, it was still more dangerous in the classroom than being safe and sound at home, where there was no way I could inadvertently catch Covid-19. But it was fun and satisfying to interact with the students in person once again.

Wearing masks provided no impediment at all to my teaching in person, and the two classes I taught went very well. Nonetheless, I missed the benefits of remote teaching via Zoom. No time was wasted driving to and from Fordham University. I had also gotten to know each student in the class better in the online environment, than in the in-person classroom, in which it was easier for a student to keep a low profile. My take-away from this experience is as I expected: online education has enormous value on the university level and should not be seen as just a stopgap in fighting the dissemination of the destructive Covid-19 virus.

In general, I found that the three terms I spent at home, teaching remotely during the pandemic, have had an excellent effect on both my professional and personal life. I had much more time for writing—both my science fiction stories and my scholarly nonfiction about the impact of social media—and projects I began during that time at home continued after I returned to teaching on the university campus. Similarly, the beneficial personal effects of staying at home, ranging from gardening to spending more time with my family, have continued.

My thinking about the Covid-19 pandemic is, if anything, to take it even more seriously. My wife and I have not only been vaccinated, but double-boostered. Clearly, the appearance of new strains of the virus means we—the human species—are by no means out of the woods as yet. My wife and I continue to take all the precautions we can take. We only eat outdoors in restaurants, or otherwise takeout food if we do not want to cook. We wear masks when we shop in supermarkets, go into post offices, etc., and stay in those places for as limited a time as possible. The same applies to my time in person at Fordham University. I go to the campus in person only to teach classes. I am glad that departmental meetings and the like are conducted via Zoom.

Given the depraved Russian attack on Ukraine, the world’s attention has understandably moved away from Covid-19. I feel that way too. But until we get vaccines that can be effective against all variants, we need to continue to be on our guard about the virus and reap whatever benefits we can from remote education and conducting of business.

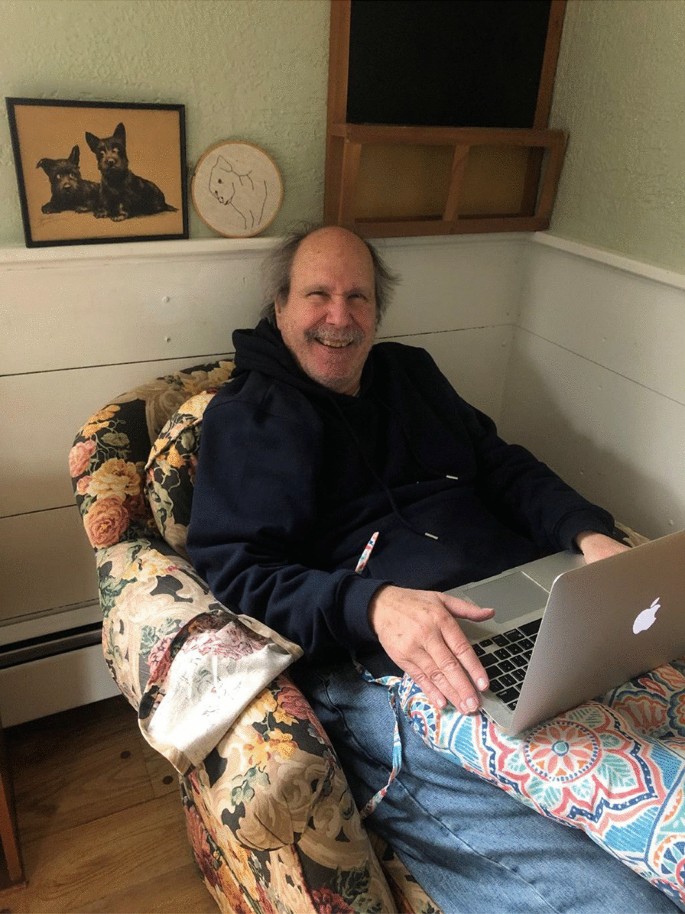

Fig. 11 [New figure] The photo is of me right now on Cape Cod, at the house we bought last year with our daughter, for a brief getaway

Jānis (John) Tālivaldis Ozoliņš , Ballarat , Victoria , Australia , 8 April

[Unchanged biography.] Jānis (John) Tālivaldis Ozoliņš is Adjunct Professor at the University of Notre Dame Australia, Visiting Professor, Faculty of History and Philosophy and Honorary Fellow, Institute of Philosophy and Sociology at the University of Latvia, Latvia, and Adjunct Lecturer, Catholic Theological College, University of Divinity, Melbourne, Australia. He lives in Ballarat, Victoria, and also in Riga, Latvia, with his wife. He has four adult children.

The past year has seen Melbourne claim the title of the most locked down city in the world and the return to a semblance of normality really only beginning in November 2021 with most restrictions easing. Return to my physical workplace became possible at the beginning of February 2022. Although my office looked the same, gremlins had got into my Internet and phone connections so that my phone did not work and my computer could not access the Internet. Still, it was nice to be back, even though we were still expected to be sparing in our workplace attendance.

Classes commenced face-to-face for the first time in nearly a year, though with students having to maintain the mandatory 1.5 m apart. Classes, on government advice, were restricted to 2 h only, rather than the full three hours that was normally allocated and students were not allowed to linger after classes. The rules relaxed after t3 weeks, perhaps because common sense prevailed, as with 93% of the population having received their double vaccination, the danger from the virus was no longer as great.

In the workplace, the 2 years of mostly online learning meant that the option for students to join online rather than face-to-face was made available. The challenge is to find ways in which it is possible to not only teach the face-to-face class in front of you, but also involve the online students. It is one thing to develop teaching methods that work for online students only, quite another to find ways to teach both face-to-face and online. Add in the possibility of asynchronous learning via lecture recordings and web-based materials, and the challenges multiply. There is no question that the pandemic has thrown up a great many new challenges in the teaching and learning space.

One of the main revelations of the pandemic has been the authoritarianism of both corporations and state government in mandating vaccination and in the latter the tendency to stifle all dissent and happily impose nonsensical restrictions. For example, at one stage, as restrictions were easing, restaurant patrons were required to wear masks if they were standing but could remove them when seated. The demonisation of those who were unvaccinated was unconscionable and revealed a rising predilection for intolerance of alternative perspectives and willingness to use coercion to impose the fiat of the government. The pandemic has encouraged the undermining of democracy by allowing leaders to continue to invoke emergency powers that enable them to rule without the usual scrutiny by parliament. Unchecked power always leads to disaster. The lack of alternative voices means that many of the problems thrown up by the pandemic, such as the steep rise in mental health issues especially amongst children and adolescents are not being tackled as vigorously as they need to be.

The world has changed and many things as academics we took for granted, such as international travel, is much more restricted and made more difficult. Zoom has become the cheap alternative to face-to-face meetings. We have swapped appearance for reality. We are much more conscious too, of all the viruses and bacteria that are lurking around the globe waiting to infect us. A recent outbreak of Japanese encephalitis in Australia had the health department providing the rather unhelpful advice that people should avoid getting bitten by mosquitoes lest they succumb to this relatively rare disease. Despite all this, I face the future with hope and wary caution.

Fig. 12 [New figure] My desk in my study. The only change is a new laptop

A Heightened Awareness Towards Scholar-Activism

James D. Kirylo , Columbia , SC , USA , 8 April

[Unchanged biography.] James D. Kirylo is Professor of Education at the University of South Carolina. His published books, amongst others, are The Thoughtful Teacher : Making Connections with a Diverse Student Population (2021), Reinventing Pedagogy of the Oppressed (2020) and Paulo Freire : The Man from Recife (2011).

It has been just over 2 years since Covid-19 viciously emerged on the world stage, with over six million succumbing to death and countless others who continue to deal with long-term effects. The magnitude of this deadly disease has clearly been no small matter. Equally consequential, however, the wonders of science to produce a vaccine at such a rapid pace has been a marvel to behold, saving countless lives and averting serious illness.

With respect to my professional life, not much has changed since my initial 2020 and subsequent 2021 instalments for this series of Covid-related articles. I pretty much exclusively taught online prior to the pandemic, continued to do so during its height and am continuing at this very moment. This means, of course, that there was not a necessity for me to change my instructional delivery forum from a traditional classroom setting to online. A seamless, minimally disruptive process was a good thing. Moreover, it became even more crystalized how fortunate I was (am) to be in a privileged space and have the availability of technology, access to medical care and to be fully vaccinated—indeed, to even have the luxury to ponder that we are hopefully coming out on the other side of the pandemic.

Whilst the vaccine is available to major portions of the world, we still have a way to go on that score. Just this morning as I gathered my thoughts to write this piece, it was reported that millions of the world’s poor still have not received the first shot. This should alarmingly alert us all regarding how much work still needs to be done in the effort to foster a global-common-good when it comes to health and wellness care. When it comes to this care, along with access to opportunity, quality education and availability to technology, the idea of a ‘new normal’ remains as the ‘old normal’ for countless people. That is, not much has changed for those who have historically been on the outside, looking in. They are still knocking on the proverbial door.

The pandemic has exposed the human condition even more when it comes to the disparities between the haves and have nots. That is why, for me—right here, right now—writing this final narrative for this three-part-series of articles, I cannot help but think about ways that should be pursued in order to cultivate what the liberation theologian would call making a preferential option for the poor. In other words, this ‘new normal’ must be infused with a heightened sense of inclusiveness on how we stay actively engaged in advocating for policies and practices on behalf of the most vulnerable amongst us, whereby their ‘old normal’ of lack is brightly transformed to a ‘new normal’ of sitting at the table of access and opportunity. Becoming a more forceful voice—what many are characterizing as a scholar-activist—has amplified my attention during this era of the pandemic. My hope is that it does the same for still many others.

Fig. 13 [New figure] At my desk in my home office

Keeping On Whilst Keeping On…

Paul R. Carr , Montréal , Canada , 9 April

[Unchanged biography.] Paul R. Carr is a Full Professor in the Department of Education at the Université du Québec en Outaouais, Canada, and is also the Chair-holder of the UNESCO Chair in Democracy, Global Citizenship and Transformative Education (DCMÉT) .

Documenting the last 2 years of living with and through the pandemic has been a cathartic and transformative experience. The ebb and flow of hoping to re-create social interaction has consistently been dashed and softened by the reality that each time the society opens up (and all of these terms need to be problematized, examined and unpacked), the number of cases of Covid-19 explode. Everyone wants to go out, get out, be with people, and enjoy cultural events, dining, lived experiences together and the like, and yet the risk of doing so is constantly a concern for everyone.

I, along with many others in my social circle and more generally in Canadian society, contracted the Omicron variant at the end of 2022. I have no idea how, where, from whom, etc., as I had little social contact at that time. Having already had two vaccinations certainly helped diminish the impact but I would not want to live through it again. The formally documented number of Covid-19 cases and deaths is most likely severely under-represented, and this means that we are really not sure of the true impact, especially in areas where data are not collected.

We are all learning to be arm-chair epidemiologists, attempting to digest and interpret figures, trends, concepts and information so as to make living together a more agreeable experience. The 10–15% who refuse to be vaccinated in Canada, for instance, have had an extremely deleterious effect on the healthcare system, with a disproportionate percentage of hospital beds being allocated to the non-vaccinated. The trucker protest and subsequent political movements for ‘freedom’, however that is interpreted, has also cajoled governments to ‘return to normal’, ‘open up society’ and to ‘live with the virus’.

Despite the debate and confusion around wearing masks, presenting or not mandatory vaccine passports, limiting access to public and private spaces, constant references to mental health and the need to socialise and, as well, the overarching framing of everything within an economic trapping, we continue to function, if that is the word for it. Things have changed but we still have social inequalities, which, on the contrary, are being more clearly illuminated as we learn to accept the integration of the virus within our social systems.

At my university, I have taught one course in person in 2 years, and everything else is distance education. The directives change often, and rightly so, and it is difficult to quickly switch, for example, from in-person to a distance course, and vice-versa. Surprisingly, I have adapted to online teaching but this requires support, re-thinking and a lot of preparation. What we lose in the affective interactions and relationships where we can see and denote body language, laughter, human emotions and interplay between students and professors can, in a small way, be compensated with online engagement.

For example, I have created a closed-group Facebook page which has allowed for more innovative sharing of content, comments and co-construction of knowledge and a more effective organization of assignments and evaluations (which are all submitted and evaluated online without paper and the potential of misplacing or poorly documenting students’ work).

Although attendance rates appear to have increased with online learning, we also face some dilemmas with cameras off or not knowing who is engaged or not. I am concerned about the impact on students, who are often isolated and who also face real-life situations in relation to employment, relationships, and support.

The committees, the meetings, the research, the proliferation of international presentations and a panoply of online activity have also increased markedly and substantially. My collaboration with UNESCO and international partners has also been enhanced through a re-orienting of how I/we worked before the pandemic. Not less busy, not less productive, not less engaged, not less fulfilled, but… this is a different experience. Perhaps, the incalculable benefit of working and living with my partner has made the transition, if that is what it is, more agreeable and enjoyable.

I am concerned about lots of things, and the pandemic has heightened my distress at how the world wishes/attempts to come together, especially with warfare being an almost unstoppable force that decimates humanity and the environment. We continue to get vaccinated (I will be getting the fourth one in a few weeks) but I am fully cognizant that vaccination, which is not, in the least, evenly distributed around the world, is but one part of the puzzle. But I remain hopeful and optimistic, despite everything, that we can build a better place together even if this will require millions and billions of individual gestures, actions, hugs and moments. This reflective project is but one of the actions to stimulate solidarity and humanity across boundaries and borders.

Fig. 14 [New figure] This is not a pipe/office

2022 : T he New Normal

Nina Hood and Marek Tesar , Auckland , Aotearoa New Zealand , 13 April

[Updated biographies.] Nina Hood is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Auckland and the founder of the not-for-profit organization The Education Hub. Marek Tesar is a Professor, Head of School and Associate Dean International at the University of Auckland. They live in Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand, with their two sons.

With the Pandemic slowly winding down, and the ‘orange light’ setting being approved for Aotearoa New Zealand (on today, the day of writing this), which removes many restrictions, we have certainly moved away from our original elimination response to the idea that we can be living with the virus. This move coincides for us with promises of the future—to be able to attend meetings and to teach in person, and to have a physical graduation ceremony.