Problem loading mint-content-page app.

Things aren't going well... have you tried refreshing the page and are you using an up to date browser? If so, and you still see this message, please contact us and we'll help you out.

You have Javascript disabled and your user experience may not be as intended without enabling it. Please consider enabling Javascript or email us at digital [at] industry.gov.au for further assistance.

Corporate plan 2022–23

Download or share.

Our Corporate plan 2022–23 explains who we are, what we do and where we are going.

It outlines our:

- purpose, key activities and strategic priorities

- operating environment

- portfolio entities and stakeholders

- risk management and oversight

- performance measures.

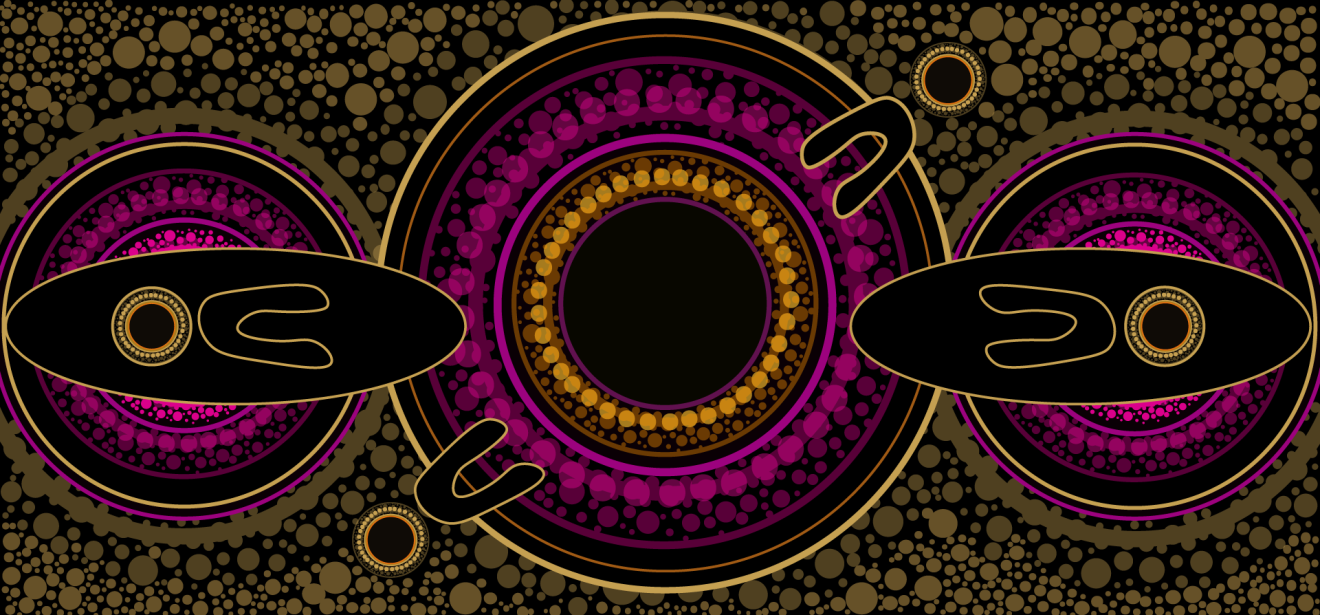

Acknowledgement of Country

Our department recognises the First Peoples of this nation and their ongoing connection to culture and country. We acknowledge First Nations Peoples as the Traditional Owners, Custodians and Lore Keepers of the world’s oldest living culture and pay respects to their Elders past, present and emerging.

Artwork by Lynnice Church, 2021

About the artist and artwork

Ms Lynnice Church is a Ngunnawal, Wiradjuri and Kamilaroi woman who resides in Canberra. A contemporary Aboriginal artist, Lynnice is self-taught and has painted since she was a young girl. Her artwork reflects the continuing connection of Aboriginal culture in the context of today’s society. She has always been passionate about all forms of art as expression, particularly Aboriginal art and culture and interpreting this into a modern day landscape.

The artwork shows the importance of listening, sharing and building knowledge and understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture to create a culturally safe space. This is shown by the 2 shields and people sitting either side of the centre circle which symbolises the rich culture and experiences that our people bring and are able to share. The centre circle shows this point of connection and the importance of relationships that can only be built through respect, collaboration and trust.

Secretary’s introduction

The Department of Industry, Science and Resources and our broader portfolio are integral to the Australian Government’s economic agenda. Our purpose is to help the government build a better future for all Australians through a productive, resilient and sustainable economy enriched by science and technology. We do this by:

- growing innovative and competitive businesses, industries and regions

- investing in science and technology

- strengthening the resources sector.

In an increasingly complex and interconnected world, we work with other Australian Government agencies, states and territories, international counterparts and a range of external stakeholders. This enables us to deliver integrated policy advice and implement effective policies and programs.

Our portfolio is at the heart of the government’s plan to revitalise Australian industry and make the most of new and emerging technologies. This will create productive, sustainable and high-value jobs in the economy of tomorrow. The portfolio supports businesses and industries by reducing barriers to productivity, designing appropriate regulatory frameworks and providing targeted investment and services.

The department helps Australia’s industrial and resource sectors respond to the ongoing pressures of the COVID-19 pandemic, natural disasters and economic adjustments. We place people and businesses at the centre of our programs and services, consistent with the broader Australian Public Service reform agenda.

We work effectively thanks to the capability of our staff, systems and practices. We do everything with integrity and strive to be a model employer. We will maintain our collaborative, supportive and inclusive culture where everyone feels valued and can perform at their best.

This corporate plan for 2022–23 to 2025–26 sets out how we will achieve our purpose and deliver the government’s priorities. It provides an overview of our operating environment, strategic priorities, activities, risks, capabilities, and how we measure our performance.

I am pleased to present our corporate plan as required under paragraph 35(1)(b) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 . This is our main planning document and was prepared according to the requirements of the PGPA act.

I look forward to reporting on our progress in the performance statements included in our annual report.

Our key activities and strategic priorities

Our purpose.

Building a better future for all Australians by enabling a productive, resilient and sustainable economy, enriched by science and technology.

We will achieve our purpose through the following key activities and strategic priorities.

Key activity 1.1: growing innovative and competitive businesses, industries and regions

- renewables and low emissions technologies

- medical science

- value-add in the agriculture, forestry and fisheries sectors

- value-add in resources

- enabling capabilities.

- address barriers to scale and competitiveness for Australian manufacturers

- develop domestic manufacturing capabilities

- benefit regional communities

- upskill the sector’s workforce to ensure Australia can make things again.

- Implementing the Australian Made Battery Plan to guide governments and industry towards a shared vision of end-to-end battery manufacturing.

- Boosting critical supply chains and economic resilience by encouraging diversification of Australian industry and its imports, and promoting Australia as a reliable, responsible and sustainable partner. This includes bolstering capability to identify and address risk in critical supply chains.

- Enhancing regulatory settings for businesses and the community through harmonised national frameworks that promote ethical and sustainable market growth, the responsible use of technology and encourage business collaboration, innovation and investment. For example, implementing country of origin labelling for the seafood industry will enable consumers to make informed decisions on their purchases.

- Implementing the Buy Australian Plan to improve the way Australian Government contracts work, ensuring more procurement opportunities are available to Australian businesses and their employees.

- Maximising the benefits of sovereign space technologies and data, including using them to address challenges such as natural disasters and climate change. This includes supporting the creation and adoption of critical technologies and maintaining a responsible regulatory framework for space sector activities.

- enhancing our dialogues and partnerships in science and technology, both in Australia and internationally

- providing medium to long-term funding for industry-led research collaborations through the Cooperative Research Centre Program

- helping businesses transform through the Entrepreneurs’ Programme

- co-administering the Research and Development Tax Incentive.

Key activity 1.2: investing in science and technology

- Building a stronger science sector to help solve challenges, improve productivity and wellbeing, and boost the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) pipeline.

- Investing in Australia’s technology capabilities such as quantum, robotics and artificial intelligence to boost our economy and create high-value jobs that will help retain talent in Australia.

- Ensuring Australia has the advanced measurement science it needs to accelerate our economy and support global trade, by developing and harnessing the expertise of the National Measurement Institute.

- Securing long-term science and technology capabilities by investing in Questacon’s grassroots science engagement activities and ensuring they reach diverse communities, including those in remote and regional Australia.

- Supporting Australia’s digital capability through targeted initiatives to accelerate the adoption of technologies and foster transformation across the economy.

Key activity 1.3: supporting a strong resources sector

- Growing national prosperity through a strong and resilient resources sector that continues to create sustainable and high-value jobs, including in regional and remote communities and maintains Australia's reputation as a stable and reliable energy supplier to overseas markets.

- Supporting the sector to contribute to the global transition to net zero through emissions reduction, and capitalising on opportunities presented in a low-emissions economy.

- Accelerating the growth of Australia’s critical minerals sector to support new clean-energy technologies in Australia and overseas, including delivery of the Critical Minerals Strategy.

- Addressing community expectations on environment, social and governance credentials . This includes strengthening First Nations engagement, and examining options to improve gender equality, skills and safety in the resources sector.

- Encouraging proactive planning for decommissioning offshore oil and gas projects and overseeing decommissioning of the Laminaria–Corallina oil fields and Northern Endeavour facility.

- Implementing reforms to secure and ensure oversight of our domestic gas supply , including reforming the Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism.

- Progressing a responsible and sustainable framework to manage and dispose of radioactive waste .

Our operating environment

An uncertain and complex economic environment.

The Australian economy has shown significant resilience to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, ongoing natural disasters, and geopolitical instability and their associated domestic and global implications. However, the economic environment remains uncertain and subject to continued disruption including in industrial, financial and energy markets. The Australian economy must keep adjusting to remain productive, resilient and sustainable.

Our economy’s short-term growth will be affected by the rapid rise in global inflation and associated substantial tightening in financial conditions, exacerbated by ongoing supply chain disruption and skills shortages. Our long-term prosperity relies on continued productivity growth. And yet, Australia’s productivity growth has slowed over the past decade, as it has in other advanced economies. Reasons for this include a structural shift towards services, low rates of cutting-edge innovation domestically, and companies adopting new technologies at a slower rate.

Factors that will influence our policy advice and program implementation include:

- responding to the implications of geo-strategic shifts

- the challenge of adapting to and mitigating against climate change

- supporting equitable outcomes for all Australians – including economic empowerment for disadvantaged groups such as First Nations people

- our continued demographic transition

- technology changes that will shape how we work and live.

Growing business and industry

In this operating environment, we will support the government strengthen Australia’s prosperity by stimulating high-growth industries and increasing commercialisation of Australian research.

We are establishing the $15 billion National Reconstruction Fund (NRF), a major part of the government’s Future Made in Australia agenda. The NRF will target projects and investments that help Australia capture new, high‑value market opportunities to help Australian businesses grow and succeed. It will diversify and transform Australian industry to help create secure, high-value jobs and drive sustainable economic growth.

The NRF will complement existing grant programs that develop domestic manufacturing capabilities and upskill the sector’s workforce.

The importance of secure and resilient supply chains has been demonstrated over recent years. Our Office of Supply Chain Resilience will support the government to work with domestic and international partners to identify and monitor vulnerabilities and improve resilience to facilitate ongoing access to essential goods and services.

The world is currently in an acute energy crisis against the backdrop of a longer term transition to lower emission energy sources, both of which have significant implications for individuals and businesses. We will support the government’s broader energy market reform agenda, to ensure Australian industry has access to secure and affordable energy as they transition to lower emission energy sources.

We are providing targeted support to critical and emerging technologies that make the most of Australia’s potential and deliver solutions to real-world problems – for both commercial and societal gain. This includes support for next-generation technologies, such as quantum, robotics and artificial intelligence.

To lift our commercialisation performance, we will support entrepreneurs and businesses to invest in research and innovation, create new ideas, scale up and grow. This will promote the translation of Australia’s world-class business research and ideas into new, high value and in-demand products and services.

We will drive the delivery of the Australian Made Battery Plan, including publishing Australia’s first National Battery Strategy, supporting the creation of a battery Manufacturing Precinct, and implementing a Powering Australia Industry Growth Centre focusing on commercialisation, international market access, management and workforce skills, and opportunities for regulatory reform.

The Australian Made Battery Plan complements other government priorities including the NRF, Powering Australia (including the National Electric Vehicle Strategy and Australia’s emissions reduction target), Rewiring the Nation, the Critical Minerals Strategy and the Buy Australia Plan.

We will ensure a responsible regulatory framework for space activities and that space services, capability and investment supports Australia’s transition to a high-tech future, including underpinning our manufacturing industries.

Rapid scientific and technological advancement

Science and technology are key to addressing national challenges. They underpin the development of new jobs, businesses and industries, and enable existing industries and business to innovate and grow. We will support the government to create an environment that supports Australian know-how and harnesses investments in science and technology to improve the lives of Australians, contribute to national wellbeing and build our industry, science and research capabilities.

We are revitalising the National Science and Research Priorities and renewing the National Science Statement to provide a long-term vision for Australian science and support stronger alignment of effort and investment, to deliver greater benefits for all Australians.

We are partnering internationally to showcase Australian knowledge and ensure we have access to resilient critical technology supply chains. We work with domestic and international organisations to ensure Australia’s regulatory environment encourages investment, establishes trusted technology frameworks, and shapes global standards and ethics that will guide the development of safe and trusted technologies.

We ensure Australians receive the maximum benefits from rapidly advancing digital technologies. We encourage small and medium businesses to adopt digital technologies, make sure Australians have the digital skills to participate in the modern workforce, and contribute to the development of regulation to guide those developing or using new technologies. We monitor and coordinate digital technology policies across government so they are cohesive and consistent.

We will continue encouraging greater diversity and inclusion of women and under-represented groups in STEM. The government has commissioned an independent review of the effectiveness of existing government programs in these areas and the cultural and structural barriers to participation and retention. The results of the review will help us identify and use approaches that improve diversity and inclusion.

We will continue working with the science and research community to promote, enable and harness Australia’s world‑leading scientific research. Our public research institutions – including the CSIRO, Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO), the National Measurement Institute (NMI), and Geoscience Australia – ensure Australia has access to world‑leading research infrastructure and expertise.

In 2023 we’ll start construction of the Square Kilometre Array, an innovative global project that will expand our understanding of the universe and support jobs and growth in regional Australia.

Questacon continues to strive to engage all Australians with science, technology and innovation, and connects communities across Australia with STEM opportunities.

NMI continues delivering independent, specialised measurement services and regulation that strengthens the international competitiveness of Australian businesses and underpins confidence in products and services for all Australians.

All of this contributes to creating a resilient economy through high-value jobs being retained in Australia, consistent with the government’s objective of growing technology-related jobs to 1.2 million by 2030.

Supporting a strong resources sector

A strong, competitive and sustainable resources sector is crucial to a thriving Australian economy. Our resources sector will provide export and employment opportunities, particularly in regional Australia, well into the future.

The resources sector has an important role in the transition to net zero emissions, both in Australia and internationally. We will prioritise the Critical Minerals Strategy and support the sector to seize the opportunities of this transition. This includes supporting the deployment of emissions abatement technologies across the sector and growing our critical minerals sector to provide the inputs required for low emissions technologies.

Australia’s resources sector can play a critical role in the global transition to net zero. We will keep supporting collaboration between governments to attract international investment in Australian critical minerals projects and support the sector to build, scale and grow its downstream processing capabilities.

Australia’s coal and gas exports will support our trading partners as they implement decarbonisation initiatives to achieve net zero. Gas will continue to have a role in Australia, ensuring energy security while we increase renewable energy generation. We will also work to understand the emissions impacts of coal and gas in Australia’s energy mix and support an orderly transition to net zero.

We need to carefully balance our domestic energy security with the needs of trading partners, who invest in our resources sector and rely on Australian commodities for their own energy security. A key priority early in 2023 is to support the government to reform the Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism and ensure there is sufficient domestic supply of gas to support our consumer and industrial needs.

We will ensure a sustainable and responsible approach to environmental management, including for offshore oil and gas activities and the way we manage radioactive waste. For example, we will continue to work with the offshore petroleum industry and regulators to encourage early and proactive planning for decommissioning and to ensure titleholders meet all costs and liabilities over the life of the project, including for decommissioning activities. We will also promote sustainable mine closure practices through the government’s participation in rehabilitation planning and regulation at the Ranger and Rum Jungle sites in the Northern Territory.

In supporting a strong resources sector, we will reinforce whole-of-government priorities including improving First Nations engagement, promoting gender equality and onsite safety to ensure that the development of Australia’s resources is done safely and benefits all Australians.

Our capability

The Department of Industry, Science and Resources was created on 1 July 2022 following machinery of government changes announced on 1 June 2022. We gained responsibility for the Critical Technologies Policy Coordination Office, the Office of Supply Chain Resilience and the Digital Technology Taskforce. Our climate change and energy functions were transferred to the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water.

We have restructured our department to align our functions with government priorities and to build policy and corporate centres of excellence that support our key activities. The department maintains cross-cutting policy and corporate capabilities that service the whole department. These include international and economic and data analytics capabilities, as well as corporate enabling capabilities.

Our employees are our greatest asset, and investing in their capability will help us deliver the corporate plan. We will maintain and develop a capable and professional workforce with the right tools and processes to do their jobs.

Our next People strategy will be finalised in 2022–23. It will promote modern ways of working across our national footprint, using technology and innovative learning approaches. It will drive our approach to attracting and retaining talent.

We are creating an environment that celebrates diversity, where employees feel they are safe and belong through our:

- Accessibility action plan 2020–2025

- Inclusion strategy 2021–2023

- Safety, health and wellbeing strategy 2020–2023 .

Shared services

We have a national footprint across Australia so our people can work directly with stakeholders. Our 3000-plus workforce operates from more than 60 locations in Australia and overseas supporting the work of the department and government.

Our Business Grants Hub works closely with policy partners to deliver grant administration services in 11 different Australian Government agencies. We also provide payroll and financial management systems to 12 Australian Government agencies. In 2022–23 we will strengthen our service provision and introduce new ways to measure customer satisfaction.

Technology and data

In 2022–23 we will develop and provide technology platforms that provide effective and efficient service. Our priority is to create a sustainable ICT environment that delivers effective workplace collaboration, innovation, security management, and greater staff productivity. This will reflect our status as a mature, data-driven organisation and improve policy outcomes for businesses and the Australian community.

Our Data strategy 2021–2024 helps our department work more efficiently, improves how staff access and use data, and manages our response to the new Data Availability and Transparency Act 2022 .

We will deploy more sophisticated data capabilities (such as econometrics, data science, geospatial analysis and modelling) to respond to challenges and opportunities across our policies and programs.

We will raise data literacy by ensuring our employees:

- know what data to use to solve problems

- can apply critical thinking to understand and address data’s strengths and limitations

- use data strategically to shape policy and deliver effective programs, regulations and services.

Our portfolio entities and stakeholders

We work closely with the specialised agencies and entities in our portfolio. We deliver services for the Australian community, whole economy and other Commonwealth portfolios.

Beyond our portfolio, we work with a diverse range of stakeholders and partners to support the government, industry, businesses and the Australian community.

We are responsible for whole-of-government coordination and advice on cross-cutting policy issues, including critical technologies, the digital economy and supply chain resilience. We draw on our strong relationships across the Australian Public Service to deliver these responsibilities.

The department does not have any subsidiaries.

Stakeholders

- First Nations People

- science organisations

- universities

- international partners

- consumer bodies

- professional associations

- not-for-profit organisations

- state, territory and Commonwealth entities

The department and its portfolio entities use these tools to support sectors and stakeholders:

- regulation and legislation

- service delivery

- data and analysis.

Our risk management and oversight

We have embedded a proactive risk management approach in our policies and processes, equipping staff with practical tools and techniques to make balanced and informed decisions in changing circumstances.

Our governance structure oversees the enterprise risk framework to ensure we can respond to evolving opportunities and threats in line with our enterprise risk appetite.

By communicating openly and honestly about risk, and actively engaging with it, we will:

- respond to rapidly changing operating environments

- engage with new and emerging risks

- pragmatically address the risks we share across the department and with other stakeholders.

Our Risk Management Framework is aligned with the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy . We will continue refining the framework to reflect contemporary risk management practices.

The tables below outlines our enterprise risks and how we manage each one.

Enterprise strategic risks

Enterprise operational risks, our governance.

Our strong governance arrangements support our decision-making – by ensuring transparency, accountability and integrity are applied to all of our activities.

Our governance committee structure includes the Executive Board and its sub-committees. Sub-committees cover people and culture, financial management, security and program performance.

Our committee structure provides assurance and oversight of our management responsibilities and supports compliance with legislative, regulatory, financial and other obligations. This helps the Secretary in discharging their oversight and governance obligations.

Our performance

We measure and report on our performance to track progress against our purpose and key activities. This demonstrates accountability to our ministers, the government, the parliament and the Australian public. Our performance is reported in our annual report.

Our performance measures relate directly to our purpose and key activities. The measures are both qualitative and quantitative to assess our outputs, efficiency and effectiveness over time.

Performance information for each key activity is set out as follows:

- performance measure: used to track progress toward an intended result.

- why this matters: the impact, difference or result we want to achieve to support the key activities and purpose.

- targets: what success will look like.

- data sources: the information we will use to measure our performance against the target.

- changes from previous year: this field is included for the first time in this corporate plan. It allows comparisons between reporting periods.

To assist the government to build a better future for all Australians by enabling a productive, resilient and sustainable economy, enriched by science and technology.

Our portfolio budget statement (PBS) outcome statement

Support economic growth, productivity and job creation for all Australians by investing in science, technology and commercialisation, growing innovative and competitive businesses, industries and regions and supporting resources.

Activity 1.1: growing innovative and competitive businesses, industries and regions

This activity aims to support the growth of innovative and competitive businesses, industries and regions, and build a diversified, flexible, resilient and dynamic economic base that can identify and adapt to new markets and emerging opportunities. It relates to PBS 2022–23 Outcome 1, Program 1.2

Removed performance measures for activity 1.1

Activity 1.2: investing in science and technology.

This activity aims to boost our science and technology capability to facilitate the development and uptake of new ideas and technology and build a strong base for science to be used in Australian decision-making. It relates to PBS 2022–23 Outcome 1, Program 1.1.

Removed performance measures activity 1.2

Activity 1.3: supporting a strong resources sector.

This activity aims to support the sustainable development of the resources sector, attract private sector investment and encourage innovative technologies. It relates to PBS 2022–23 Outcome 1, Program 1.3.

Removed performance measures for activity 1.3

Alignment between our outcomes, programs and key activities.

This year’s corporate plan includes changes to our performance measures that reflect a review of our performance framework to:

- identify areas for improvement

- align them with our functions and organisational structure

- ensure compliance with s16EA of the PGPA Rule.

We conducted the review after publishing the 2022–23 Portfolio Budget Statements. This means that some of the performance measures in this plan do not reflect those in the PBS.

The following table describes how our outcome statements and programs align with our key activities as at 1 July 2022.

Download a copy of the plan

More information.

- Skip to navigation

- Skip to content

- Skip to footer

Write a business plan

Write down your ideas.

A business plan explains your business's goals and outlines how they will be achieved.

If you're applying for a grant or finance, you must have a business plan as part of the application.

When to do a plan

You should write a business plan before you start operating.

It can be tricky to do if you're still in the planning stages. But you can amend your plan as your business grows and changes.

Review your plan regularly and update it as needed.

Even existing businesses may benefit from putting a business plan together.

What to include

In general, a plan would usually include:

- an executive summary

- description of your business

- information about your business structure

- market research

- marketing and sales strategy

- financial plan - such as your start-up costs and funding , expected cash flow and sales plan

- staffing requirements, including how you will attract, select and recruit workers .

Get a business plan template from the Australian Government's Business website .

For assistance putting together your plan, talk to:

- small business champions

- a business coach or consultant (fees may apply)

- government funded services like the Business Enterprise Centre NT .

Existing businesses may be eligible for the Business Growth Program . This program provides funding for existing businesses to work with business consultants.

Contact a Territory Business Centre to find out what help you might be eligible for.

On this page

Research your business idea.

Look into your idea before deciding to make it a business.

Create a sales plan

Set realistic sales goals.

Contact a Territory Business Centre

Territory Business Centres can give you information about starting a business, licensing requirements and government assistance programs.

Digital Transformation Agency

Corporate Plan 2022–23

This DTA Corporate Plan 2022–23 covers the period 2022–23 to 2025–26, as required under paragraph 35 (1)(b) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 .

Foreword from the Chief Executive Officer

Digital technology is profoundly affecting how governments deliver services. Driven by the needs of people, businesses and communities, the Australian Public Service (APS) has made great strides in using digital to improve outcomes for service delivery to citizens and businesses, and to manage the process of government itself.

With the acceleration in digital caused by COVID-19, we are now moving at a rate of change that previously would have been considered impossible for government. This creates challenges across government – to project delivery and timetables, project costs and interoperability across the APS. To support the digital transformation and the introduction of new and effective government services, we need capability, technical and cultural change across the APS. This means considering alternatives to traditional government approaches with long lead times to develop policy and services, and long-term delivery via long-lasting technology platforms. We need to go beyond ‘e-government’ – changing manual, over the counter or phone business processes to digital at the front-end and automating middle and back-office processes in the existing agency constructs. It requires reinventing the way government is set up and how it presents to its customers.

Citizen and business expectations are high, for both the quality and pace of digital change. Government service delivery is now about personalised experiences when people want to know or do something, or when they need help or care. We must use data and insights to measure satisfaction and deliver services in ways, and within timeframes, driven by those using the service, rather than by government.

The Digital Transformation Agency (DTA) is at the forefront of supporting government in its digital transformation. We lead government’s digital transformation strategy, oversee the short, medium, and long-term whole-of-government coordinated digital and ICT investment portfolio and manage whole-of-government digital and ICT sourcing and contracts.

Due to the high cost and risks involved, digitally enabled projects benefit from long-term planning, prioritised investment, coordinated sourcing and ongoing oversight. A coordinated approach achieves better value for money through whole-of-government procurement of digital products and services, reuse of existing platforms, services and standards, and investments aligned with overarching digital strategy and government architecture.

Opportunities for and uptake of government digital services will continue to rapidly evolve. Until recently, these investments have largely been driven by individual policy or agency proposals.

The DTA is now well positioned to connect, oversee at the whole-of-government level, and provide trusted advice on, digital and ICT matters and investment decisions. More strategic and informed decisions will benefit multiple agencies, provide the best value for the Commonwealth, and effectively support Australian people and businesses – positioning Australia as a world-leading digital government.

This corporate plan builds on our first year of delivering on our current mandate as a trusted adviser to government. It has been a significant year of change, transformation and hard work. In the year ahead we will demonstrate and embed our work to guide and measure the government’s ambitions in Australia’s digital future.

Chris Fechner, Chief Executive Officer

Statement of preparation

I, Chris Fechner, as the accountable authority of the Digital Transformation Agency (DTA), present the 2022–23 DTA corporate plan, which covers the period 2022–23 to 2025–26, as required under paragraph 35 (1)(b) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act).

Chris Fechner

Chief Executive Officer, 24 August 2022

To support the Minister for Finance and the Australian Government by providing digital and ICT strategy and policy leadership, investment advice, strategic sourcing, and delivery oversight to drive the government’s digital transformation and deliver benefits to all Australians.

The Australia Government is a world-leader in digital government for the benefit of citizens, businesses and communities by 2025.

To be the trusted adviser to the Australian Government and Commonwealth entities on digital and ICT matters and investment decisions.

Strategic objectives

Lead government’s digital transformation strategy.

Oversee the short, medium and long-term whole-of-government digital and ICT investment portfolio.

Manage whole-of-government digital and ICT strategic sourcing and contracts.

Be a valued employer with the expertise to achieve our purpose.

Operating context

Delivering world-leading digital government means going beyond having simple online services and investing in cutting-edge technology: the people and businesses that engage with government expect these services to be stable, secure, reliable and capable of anticipating the future needs of every user. The degree to which the APS effectively and efficiently transforms the digital landscape today will impact on the trust individuals and businesses have in government and how much public value we deliver tomorrow.

Environment

We are responsible for stewarding the government through the rapidly changing and complex digital and ICT environment. Fast-paced technological change is challenging the way we work and engage across society – creating constant opportunities to rethink how decisions about digital and ICT investment are made, and how government services are designed and delivered. Digital disruption, increased demand and the global pandemic have seen a significant shift towards digital as Australians’ preferred way of accessing services. This environment has also changed the nature of the way government operates as a digitally enabled enterprise.

The national response to COVID-19 has highlighted what is possible, however, challenges remain. We need to address fragmented digital delivery and channel inconsistencies in customer services as well as lack of investment in interoperability and reuse of digital capabilities as standards across government. In addition, ongoing reforms to the public service and fiscal challenges place a premium on the government’s ability to more effectively plan and prioritise digital transformation in the most cost-effective way. The path forward requires leadership and high levels of coordination and collaboration across government and industry. It requires alignment with an overarching investment framework from early planning through to initiative delivery and realisation of planned benefits, underpinned by a clear digital government architecture that links strategies, policies, standards and guidance.

We will continue to work diligently across government and industry to be the trusted advisor on digital and ICT matters and investment decisions. We will also continue to reinforce the essential building blocks of digital transformation, providing an informed picture of current digital capability and capacity, and mapping future needs.

The DTA is committed to strategic investments to make digital services simple, helpful, respectful and transparent to customers, and that increase focus on building capabilities that support those customers, whether they be people, communities, businesses or employees of the APS. In doing this, we will increase rigour of digital investment oversight to maximise value while reducing risk and waste.

We are an Executive Agency within the Finance Portfolio. Our people have expertise and skills in:

- overarching strategy, policy, standards and guidance for government digital and ICT investment and service delivery

- whole-of-government digital and ICT enterprise architecture

- whole-of-government digital and ICT investment portfolio planning, prioritisation, contestability and assurance

- whole-of-government digital and ICT sourcing and contracts

- discovering, framing, establishing and transitioning new digital and ICT initiatives for government

- enabling services to support a responsive, capable agency.

Through our workforce planning and development we are building an agency that can adapt to the challenges, risks and opportunities in our current and future operating environments through use of emerging technologies, contemporary approaches and broad collaboration to achieve our purpose.

Values and behaviour

Our values and corresponding behaviours reflect our mandate as a trusted adviser to government. They underpin and guide our day-to-day work practices across all facets of the way we work – within the DTA and across the APS:

- Collaboration – we work together to achieve goals.

- Respect – we make everyone feel safe, supported and included.

- Transparency – we build trust through being authentic and honest.

- Future focused – we use our expertise to support the government’s digital agenda.

- Excellence – we strive for excellence in all we do.

Diversity and inclusion

The DTA believes it is crucial to have a diverse and inclusive workplace that reflects the range of people, communities, cultures and diversity groups we serve.

We are committed to building and maintaining an inclusive working environment based on trust, mutual respect and understanding. We want everyone, regardless of who they are or what they do for the DTA, to feel equally involved in, and supported in, all areas of the workplace.

Our diversity and inclusion strategy focuses on leadership and culture, awareness and creating a sense of belonging, celebrations through recognised events, and our diversity network. Our Executive Diversity Champion plays a visible leadership role across the DTA to work with staff to create a valued, respected and diverse culture.

We ensure our offices are accessible and offer reasonable adjustments as required.

The DTA is a member of the Diversity Council Australia, the Australian Network on Disability and Pride in Diversity, and we have special access to diversity and inclusion resources.

Risk oversight and management

Our work practices and regular, open and transparent communication with stakeholders enables us to quickly identify, understand and respond to emerging risks.

We manage risk in line with the AS/NZS 31000:2018 risk management standard and have implemented the guidance to comply with the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy (RMG 211) to support the requirement of section 16 in the PGPA Act.

To achieve the strategic objectives we have developed to support the government’s mandate for the DTA, we have considered our associated strategic risks, which are summarised in the following table along with corresponding mitigation strategies.

Cooperation

We work most closely with Australian Government agencies.

We also work with state, territory and international governments, advisory and oversight bodies as well as industry and academia, and people who provide or use government services.

We cooperate effectively with our stakeholders across government and industry to understand the operating environment, identify challenges and opportunities for improvement, and provide trusted advice to government.

We are improving our ways of working by developing an agency service map of the models, tools, processes and data used across the DTA. Through this, we are identifying opportunities to improve connectedness and transparency to embed into an improved operating model to work more effectively across our organisation and across government.

The aim is to ensure better awareness and management of priorities, actively manage our peak periods and surge activities, manage consistent workflow and methods, improve reuse of data and intelligence, and implement value and benefits management across the DTA.

Performance

The DTA is responsible for leading and linking the overarching direction for digital strategy, policy and services, while being independent of its delivery. This means the benefits (impact) are often delivered by other agencies.

The following performance measures are therefore intended to assess the DTA’s contribution to the impact, rather than assess the impact itself. We will continue to refine and mature our performance measures as we mature as an agency and update our corporate plan accordingly.

Strategic objective 1

Key activities.

- Provide strategic and policy leadership on digital government through whole-of- government and shared ICT planning, investments and digital service delivery.

- Develop, deliver and monitor whole-of-government architecture strategies, policies and standards for digital and ICT investments and sourcing.

Strategic objective 2

- Manage strategic coordination and oversight functions for digital and ICT investments across the project lifecycle, including providing advice on whole-of-government reuse opportunities.

- Provide advice to the Minister on digital and ICT investment proposals and lead new digital proposals as directed by the Minister.

Strategic objective 3

- Manage whole-of-government digital sourcing and purchasing to simplify processes for government agencies and industry, reduce costs, increase speed, and generate reuse opportunities.

Strategic objective 4

- Forecast and manage required workforce, capabilities and resources.

- Support the DTA to pursue our strategic objectives.

Table of requirements

The corporate plan has been prepared in accordance with the requirements of:

- subsection 35(1) of the PGPA Act

- subsection 16E(2) of the PGPA Rule 2014

The table details the requirements met by the DTA’s corporate plan and the page reference(s) for each requirement.

At the end of your visit today, would you complete a short survey to help improve our services?

Thanks! When you're ready, just click "Start survey".

It looks like you’re about to finish your visit. Are you ready to start the short survey now?

Business planning

Find out how to create a plan for your new or current business, including writing the plan and operational documents, and setting goals.

Start your planning by:

- watching the writing a business plan video

- downloading the business plan template

- watching our small business planning webinar recording .

Planning a new business?

Find out how to plan your new business idea —use our guides, checklists and tips to help you develop your idea and sharpen the personal skills you'll need to be a business owner.

Writing a business plan

Discover what a business plan is and how you can prepare or update one for your business. Download our free business plan template.

Create a business vision

Find out how to create a vision for your business, describing your goals and what success looks like. Use our template to create your own.

Business values

Learn about developing values for your business. Follow our 5-step process to develop and implement your own values.

SWOT analysis

Get an overview of the SWOT analysis business tool, including what it involves, the benefits of using one, and how to conduct one for your business.

Short and long-term goals and KPIs

Learn about setting business goals and tracking them through KPIs. You should set short and long-term goals and review your goals and KPIs regularly.

Business policies, processes, procedures and codes of practice

Discover the value of creating and applying operational documents for your business. Codes of practice explain your legal and industry obligations.

Choosing and working with business advisers

Learn what to consider before choosing a professional to help you achieve your business goals.

Tools and resources

Find out more about the value of a business plan and create one for your business.

Video - Writing a business plan

Watch our video to help you write a business plan.

Download the business plan template

Use our template to create a plan for your new or existing business, or as a guide for making your own.

Download the SWOT analysis template

Use the SWOT analysis template to understand your business’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats.

- Updated: 1 Jun 2023

- Reviewed: 8 Dec 2022

© Department of Finance This content is only accurate as at the date of printing or download. Refer to Home | Department of Finance to ensure you are viewing the latest version.

Buy Australian Plan

The Buy Australian Plan will improve the way government contracts work and build domestic industry capability through the Australian Government’s purchasing power. Commonwealth procurement is a major economic lever, and the Government will use its significant purchasing power to support all businesses to deliver better value for money, grow the local economy and strengthen our domestic industry and manufacturing capability. The Buy Australian Plan will:

- maximise opportunities for Aussie businesses in major infrastructure projects

- open the door to more government work for more small and medium businesses by decoding and simplifying procurement processes

- establish a Secure Australian Jobs Code to prioritise secure work in government contracts and ensure that government purchasing power is being used to support businesses that engage in fair, equitable, ethical and sustainable practices

- provide more opportunities for First Nations businesses with a view to maximise skills transfer so that we can get more First Nations workers into long-term skilled work

- level the playing field by bringing in a Fair Go Procurement Framework requiring those that gain government contracts to pay their fair share of tax

- support industry sectors through the government’s purchasing power

- use government spending power to take action on climate change and support energy projects

- strengthen Defence industries and capability

- make National Partnerships work to maximise the use of local workers and businesses.

The Australian Government will provide $18.1 million over 4 years from 2023-24 (and $1.5 million per year ongoing) to the Department of Finance to improve government procurement processes for businesses, including by:

- delivering tools to improve the ability of businesses to compete for procurement opportunities more effectively

- improving AusTender to increase transparency and establish a supplier portal for panels

- increasing engagement with small-to-medium enterprises to promote awareness of opportunities to sell to the Australian Government

- improving procurement and contract management capability across the Australian Public Service to deliver value-for-money Commonwealth procurements.

This measure builds on the 2022-23 October Budget measure titled Buy Australian Plan.

Future Made in Australia Office

The Future Made in Australia Office has been established in the Department of Finance to support delivery of the Buy Australian Plan and actively support local industry take advantage of government purchasing opportunities. The Office will:

- coordinate implementation of the Buy Australian Plan across the Australian Public Service

- strengthen engagement with states and territories to deliver economic, social and environmental benefits to regions, industry sectors and communities

- build the procurement and contracting capabilities of the Australian Public Service, and

- engage directly with businesses and industry sectors to help lift their competitive capabilities.

The 2023-24 Budget commitment builds on the creation of the Future Made in Australia Office by improving AusTender, increasing engagement with businesses and improving procurement capability across the Australian Public Service.

This will make procurement clearer and simpler to help small and medium-sized enterprises, First Nations businesses, regional and remote businesses, and industry sectors to compete for and win more government contracts.

A progress report on the implementation of the Buy Australian Plan will be provided on this webpage soon.

Useful links

- Government Procurement information

- Selling to Government information

- AusTender – centralised publication of Australian Government business opportunities

- Australian industry participation – opportunities to compete for work in major projects

- AusIndustry – support and services for businesses and industry

Search Finance.gov.au

Please note: Search is currently being indexed on the new site, Friday 8 November.

Search will be available later today.

Thank you for your patience.

Countries, economies and regions

Select a country, economy or region to find embassies, country briefs, economic fact sheets, trade agreements, aid programs, information on sanctions and more.

International relations

Global security.

- Australia and sanctions

- Australian Safeguards and Non-proliferation Office (ASNO)

- Counter-terrorism

- Non-proliferation, disarmament and arms control

- Peacekeeping and peacebuilding

Regional architecture

- Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC)

- Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)

- East Asia Summit (EAS)

- Australia and the Indian Ocean region

- Pacific Islands regional organisations

Global themes

- Child protection

- Climate change

- Cyber affairs and critical technology

- Disability Equity and Rights

- Gender equality

- Human rights

- Indigenous peoples

- People Smuggling, Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery

- Preventing Sexual Exploitation, Abuse and Harassment

- Australia’s treaty-making process

International organisations

- The Commonwealth of Nations

- United Nations (UN)

- World Trade Organization

Foreign Arrangements Scheme

Trade and investment, about free trade agreements (ftas).

- The benefits of FTAs

- How to get free trade agreement tariff cuts

- Look up FTA tariffs and services market access - DFAT FTA Portal

- Discussion paper on potential modernisation – DFAT FTA Portal

About foreign investment

- The benefits of foreign investment

- Investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS)

- Australia's bilateral investment treaties

- Australia's foreign investment policy

For Australian business

- Addressing non-tariff trade barriers

Expo 2025 Osaka, Kansai

Stakeholder engagement.

- Ministerial Council on Trade and Investment

- Trade 2040 Taskforce

- First Nations trade

Australia's free trade agreements (FTAs)

- ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand (AANZFTA)

- Chile (ACLFTA)

- China (ChAFTA)

- Hong Kong ( A-HKFTA & IA)

- India (AI-ECTA)

- Indonesia (IA-CEPA)

- Japan (JAEPA)

- Korea (KAFTA)

- Malaysia (MAFTA)

- New Zealand (ANZCERTA)

- Peru (PAFTA)

- Singapore (SAFTA)

- Thailand (TAFTA)

- United Kingdom (A-UKFTA)

- USA (AUSFTA)

- Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)

- European Union (A-EUFTA)

- India (AI-CECA)

- Australia-UAE Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement

- Australia-Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)

Trade and investment data, information and publications

- Fact sheets for countries and regions

- Australia's trade balance

- Trade statistics

- Foreign investment statistics

- Trade and investment publications

- Australia's Trade through Time

WTO, G20, OECD, APEC and IPEF and ITAG

Services and digital trade.

- Service trade policy

- Australia-Singapore Digital Economy Agreement

- Digital trade & the digital economy

Development

Australia’s development program, performance assessment.

- Development evaluation

- Budget and statistical information

Who we work with

- Multilateral organisations

- Non-government organisations (NGOs)

- List of Australian accredited non-government organisations (NGOs)

Development topics

- Development issues

- Development sectors

2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

- Sustainable Development Goals

Where we deliver our Development Program

Humanitarian action.

Where and how Australia provides emergency assistance.

People-to-people

Australia awards.

- Australia Awards Scholarships

- Australia Awards Fellowships

New Colombo Plan

- Scholarship program

- Mobility program

Public diplomacy

- Australian Cultural Diplomacy Grants Program

- Australia now

- UK/Australia Season 2021-22

Foundations, councils and institutes

- Australia-ASEAN Council

- Australia-India Council

- Australia-Indonesia Institute

- Australia-Japan Foundation

- Australia-Korea Foundation

- Council for Australian-Arab Relations (CAAR)

- Council on Australia Latin America Relations (COALAR)

International Labour Mobility

- Pacific Labour Mobility Scheme

- Agriculture Visa

Australian Volunteers Program

Supporting organisations in developing countries by matching them with skilled Australians.

Sports diplomacy

Australia is a successful global leader and innovator in sport.

A global platform for achievement, innovation, collaboration, and cooperation

About Australia

Australia is a stable, democratic and culturally diverse nation with a highly skilled workforce and one of the strongest performing economies in the world.

Australia in Brief publication

This is the 52nd edition of Australia in Brief, revised and updated in February 2021

Travel advice

To help Australians avoid difficulties overseas, we maintain travel advisories for more than 170 destinations.

- Smartraveller – travel advice

International COVID-19 Vaccination Certificate

Prove your COVID-19 vaccinations when you travel overseas.

- Services Australia

The Australian Passport Office and its agents are committed to providing a secure, efficient and responsive passport service for Australia.

- Australian Passport Office

24-hour consular emergency helpline

- Within Australia: 1300 555 135

- Outside Australia: +61 2 6261 3305

- Getting help overseas

- Visas for Australians travelling overseas

- Visas to visit Australia

2023-24 DFAT Corporate Plan

The corporate plan is the department’s primary planning document. It sets out our vision, purpose, capabilities and risks, and describes the complex international environment in which we operate. The corporate plan is a roadmap for how we will deliver the Government’s agenda over the next four years and how we will measure our performance. Results against this corporate plan will be reported in our 2023–24 annual performance statements.

Download DFAT Corporate Plan

- 2023–24 DFAT Corporate Plan [Word 7 MB]

- 2023–24 DFAT Corporate Plan [PDF3 MB]

Reports and publications

Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

View reports and publications

The aim of audit insights is to communicate lessons from our audit work to make it easier for people working within the Australian public sector to apply those lessons.

View ANAO Insights

Work program

The ANAO work program outlines potential and in-progress work across financial statement and performance audit.

View the work program

Our staff add value to public sector effectiveness and the independent assurance of public sector administration and accountability, applying our professional and technical leadership to have a real impact on real issues.

View Careers

The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) is a specialist public sector practice providing a range of audit and assurance services to the Parliament and Commonwealth entities.

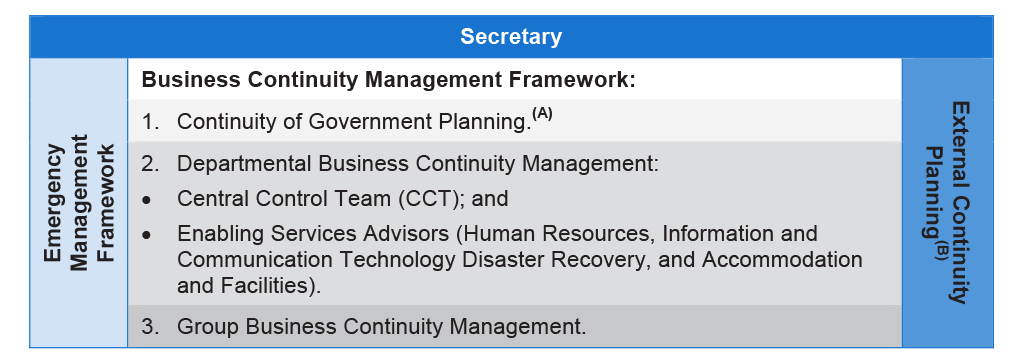

Business Continuity Management

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page .

The objective of the audit was to assess the adequacy of selected Australian Government entities’ practices and procedures to manage business continuity. To conclude against this objective, the ANAO adopted high-level criteria relating to the entities’ establishment, implementation and review of business continuity arrangements.

Introduction

1. Many services delivered by public sector entities are essential to the economic and social well-being of society—a failure to deliver these could have significant consequences for those concerned and for the nation. Other services may not be essential, but a disruption can nonetheless result in inconvenience and inefficiency, and have economic costs.

2. Government entities face a range of situations—including equipment failure, natural disaster, and criminal activity—that may lead to a significant business disruption. In response to such business disruption, entities need to have arrangements in place to support the continuation and/or resumption of essential services and ultimately return to business as usual. Often these arrangements will need to operate alongside emergency or disaster management arrangements to ensure the safety of staff and assets.

3. Business continuity management (BCM) is the development, implementation and maintenance of policies, frameworks and programs, to assist an entity manage a business disruption, as well as build entity resilience. 1 As such, BCM is an important element of good governance. BCM forms part of an entity’s overall approach to effective risk management, and can provide a capability that assists in preventing, preparing for, responding to, managing and recovering from the impacts of a disruptive event.

4. To appropriately focus an entity’s business continuity arrangements, it is important to have a clear and agreed understanding of the entity’s business objectives and the critical business functions or activities which help to achieve those objectives. The business continuity arrangements should also identify the resources supporting these priority functions. These resources are known as enabling assets and services, and include information and communication technology (ICT), property and security, and human resources.

Policy requirements and better practice

5. Business continuity management in Australian Government entities is governed by the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF), which requires entities to use a risk management approach to cover all areas of protective security activity. The PSPF applied to all former Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act) agencies, and to those former Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act 1997 (CAC Act) bodies that have received a Ministerial Direction. This arrangement is currently being revised as part of the introduction of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), from 1 July 2014. 2

6. For entities subject to the PSPF, the key mandatory requirements relating to BCM are GOV 11 and PHYSEC 7 (see Table S.1, below). The ANAO completed an audit in 2013–14 of the Management of Physical Security 3 which included a focus on the implementation of PHYSEC 7 in three entities. This audit focuses on the GOV 11 requirement.

Table S.1: Protective Security Policy Framework—key mandatory requirements relating to business continuity management

Source: PSPF, June 2013, pp. 18 and 34.

7. Protocols, standards and guidelines have been developed to support the mandatory requirements in the PSPF. In relation to GOV 11, this includes an expectation that an entity’s BCM program should comprise the following five components:

- a governance structure that establishes authorities and responsibilities for the BCM program, including for the development and approval of business continuity plans (BCPs);

- an impact analysis to identify and prioritise an entity’s critical services and assets, including the identification and prioritisation of information exchanges provided by, or to other entities or external parties;

- plans, measures and arrangements to ensure the continued availability of critical services and assets, and of any other service or asset when warranted by a threat and risk assessment;

- activities to monitor an entity’s level of overall preparedness; and

- the continuous review, testing and audit of BCPs.

8. In addition to these specific requirements, entities should seek to adopt a BCM approach that is relevant, appropriate and cost-effective. In this respect, clearly defining the purpose, priorities and coverage of BCM is important. The PSPF identifies several standards and guidelines that provide additional explanation for the five BCM components, and other aspects of BCM. These include Standards Australia Handbooks published in 2004 and 2006 4 and the ANAO Better Practice Guide (BPG) 2009, Business Continuity Management—Building Resilience in Public Sector Entities . In addition to the standards and guidelines referred to in the PSPF, there is a range of other useful Australian and international better practice materials. 5 Consistent with the PSPF promotion of a risk-based approach, entities are expected to tailor their BCM arrangements to their particular context and operating environment. In this regard, entities have some flexibility in relation to the structure, content and comprehensiveness of their programs.

9. Entities subject to the PSPF are required to report annually on their compliance with the mandatory PSPF requirements to their portfolio minister. 6 Of the 110 entities that reported on the GOV 11 mandatory requirement in 2013, 12 entities reported that they were non-compliant. The majority of the non-compliant entities were in the process of finalising reviews of their BCPs at the time of reporting.

Previous audits

10. The ANAO has conducted four audits since 2002 that have focused on BCM arrangements in entities. 7 Each of these audits has identified areas for improvement. Specific areas for improvement include the need for enhanced oversight and testing of BCM arrangements, as well as the need to adopt a program management approach to BCM in order to facilitate continual review and adjustment. The ANAO has also considered BCP and disaster recovery planning as part of the interim phase of the audits of financial statements of major general government sector agencies. These audits have highlighted the importance of BCP and ICT disaster recovery planning to the continuing delivery of services, but have observed that a number of entities relied on unplanned disruptions to business operations to test their BCPs. 8

Audit objective, criteria and scope

Audit objective.

11. The objective of the audit was to assess the adequacy of selected Australian Government entities’ practices and procedures to manage business continuity. To conclude against this objective, the ANAO adopted high-level criteria relating to the entities’ establishment, implementation and review of business continuity arrangements.

12. The ANAO examined BCM arrangements and practices in the:

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) 9 ;

- Department of Finance (Finance); and

- Department of Social Services (DSS).

13. For the selected entities 10 , the ANAO assessed the BCM framework and approach, including key documentation (such as BCM policy and BCPs), entity responses to actual events, BCM exercises and testing activities, and monitoring and review.

Overall conclusion

14. The risk and potential consequences of natural disasters and other business disruption events reinforces the need for Australian Government entities to have effective business continuity management (BCM) arrangements in place to provide for the continued availability of critical services and assets. Effective BCM arrangements give entity management and stakeholders greater confidence in the entity’s ability to manage the impact of a disruption and return to business as usual.

15. In line with policy requirements and expectations of the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF), each of the entities had established relevant governance structures, assessed risks, identified critical functions, services or assets, undertaken business impact analyses, and developed business continuity plans (BCPs). Each of the entities assessed their business continuity risk at an entity-wide level, and developed a BCM program to manage their risk exposure. The program involved annual or biennial business impact analysis, development of BCPs, and testing of business continuity arrangements. Finance’s approach was the most structured, providing a clear line of sight between the 17 functions it identified as critical and the actions that would be undertaken to recover in the event of a disruption, including key dependencies and resource requirements.

16. CASA, as a Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act 1997 body, was not required to comply with the PSPF, but had nonetheless developed its BCM approach generally in line with the PSPF. CASA has chosen to manage the business continuity of its most time critical activity 11 separate from its entity-wide BCP. While CASA’s BCP anticipates having functions and systems operational in alternative locations within 24 hours, it did not identify a list of these critical functions or activities and their key dependencies. As a result, the focus of the plan was on enabling resources rather than critical functions as envisaged by the GOV 11 element of the PSPF and better practice guidance. However, CASA’s BCP did provide a list of 23 ICT systems and facilities that need to be recovered within 48 hours. The absence of a list of critical functions, and the lack of integration of the arrangements for managing critical functions, introduces the risk that the delivery of key products and services will not be appropriately prioritised and addressed during a disruption. To better support the management of disruptions, CASA should identify and prioritise critical functions in its BCPs, and detail key dependencies.

17. As a larger and more diverse entity, DSS’s BCM approach was to identify six Mission Critical Activities and 281 critical functions (requiring recovery within seven days). Of these critical functions, 120 related to the six Mission Critical Activities and the remainder were considered to be enabling services. Responses were to be managed across 33 BCPs, each varying in comprehensiveness. The volume of documentation is potentially problematic from a recovery perspective. To assist in making decisions regarding potential recovery action, DSS should prioritise and rationalise its critical functions at an entity-wide level. This would involve determining entity priorities for services and assets, particularly in relation to resourcing and the continuation, recovery and/or stand down of functions.

18. Since January 2010, the audited entities have each experienced a number of business disruptions, ranging in impact from the minor and inconvenient—partial evacuations and all day outages of critical systems—to the significant—week-long office closures due to weather events including cyclones and floods. In most cases the entities’ emergency or disaster response arrangements were initiated quickly to provide protection for staff and property, however, in this period Finance was the only entity that had initiated its BCM arrangements in response to disruptions to provide protection for affected critical functions.

19. CASA and DSS managed several significant disruptions in 2011, including the Queensland floods and Cyclone Yasi, without activating business continuity arrangements. CASA has advised that some critical operational processes were diverted to other locations. 12 Beyond this, CASA adopted an emergency response intended to protect staff and property. Similarly, DSS responded with an emergency management approach—business continuity arrangements were not activated. Regardless, neither the emergency management nor business continuity arrangements extended to consideration of community services (delivered by the department’s funded service providers), consequently senior management within the Queensland Office sought to manage continuity issues in relation to these services as the event unfolded. A subsequent review recommended a number of operating changes. While DSS’s Queensland State Office had revised its BCM arrangements for the continuation of services delivered by funded service providers, these arrangements were not sufficiently proactive and have not been applied at an entity-wide level.

20. To understand and improve the operation of business continuity arrangements, it is important to review the response to disruptions. Finance systematically documented incidents and their impact, providing reasons why the BCPs were, or were not, initiated during an incident, and had undertaken post incident reviews. In contrast, CASA’s and DSS’s approaches to documenting events, their impact, BCM considerations and post incident review were not systematic, limiting the opportunity for continuous improvement.

21. Between 2009 and 2013 CASA and DSS had undertaken testing of some aspects of their BCM approach. This generally included testing critical ICT systems, DSS also usually conducted an annual test of its entity-wide BCP 13 , while CASA participated in a joint exercise with NSW police and emergency services. Relative to the other entities examined, Finance had a more comprehensive testing and exercising regime in place, and conducted entity-wide annual tests for some critical functions. This included post-exercise reviews, with assigned actions, to incorporate improvements or revisions into the BCPs.

22. The PSPF provides entities with flexibility to establish a BCM approach which is appropriate to their business requirements. To be practical and useful during a disruption, the approach needs to establish priorities, be easy to follow and should be tested. Finance’s arrangements were more mature and reflected incremental improvements made by the department over a number of years. However, while CASA’s 14 and DSS’s BCM approaches align with the PSPF expectation to have a BCM program, both entities should take a more structured and systematic approach to planning for, testing and responding to business disruptions. This provides for continuous improvement to business continuity planning. The ANAO has made three recommendations in this regard.

Key findings by chapter

Business continuity management (chapter 2).

23. A key element of effective ongoing management of business continuity is developing and implementing an appropriate governance framework. Such a framework includes establishing overall policy, key responsibilities, annual planning arrangements, and performance review and monitoring arrangements. All audited entities had developed a governance framework as part of their BCM approach and had reviewed these in 2013. Each entity also issued policy and guidance, determined the objective and scope of their BCM approach, and assigned key roles and responsibilities. Generally, entities’ arrangements focused on continuing or recovering critical functions within maximum acceptable outage timeframes—mostly within one to seven days of a disruption.

24. CASA and Finance had developed overall BCM framework documents to promote a more coherent understanding of their approach, while DSS had not yet developed a similar overall representation of its BCM arrangements. Finance’s policy and guidance also provided targeted guidance for different stages of the BCM approach (and for different levels within the entity) with practical tools such as templates. CASA’s and DSS’s guidance was not as well-structured, and better links could have been established between their respective policy and guidance materials.

Assessing and Planning for Business Continuity Needs (Chapter 3)

25. Effective planning of BCM includes: identification of critical business functions; undertaking a business impact analysis; and developing strategies and plans to manage the continuation and recovery of critical functions during a business disruption. While entities generally begin with the identification of all business processes, it is necessary to refine these into a prioritised list of critical processes, and assign target recovery times. In this respect, CASA would benefit from specifically addressing critical functions in its BCPs, and DSS from rationalising and prioritising its critical functions—the list of 281 critical functions is too extensive to usefully focus on the continuation or restoration of business priorities.

26. To restore business, entities must be able to readily identify and have on hand—or recover—the technology, telecommunications and vital records necessary to support these critical business functions. It is also important to understand external and internal dependencies and prepare adequate arrangements, including with third party providers, to make sure the entity can deliver key products and services within target recovery times. Neither DSS’s nor CASA’s business impact analyses and BCPs contained sufficient details of key dependencies for their critical functions. For DSS this is an important risk to manage given the department’s use of third parties to deliver community services across Australia. There would also be merit in DSS adjusting its current approach towards more proactive and action-oriented plans that better facilitate business continuity preparedness.

Responding to Disruptions (Chapter 4)

27. When responding to a disruption an entity should record important decisions and actions, including the Control Team’s considerations regarding activating BCM arrangements. After the entity has returned to normal operations it is sound practice to review its response to the disruption. This contributes to continuous improvement, potentially placing an entity in a better position to respond to similar future events. By analysing successes and failures, lessons to be learned can be drawn out, and actions can be taken to safeguard against failures and to replicate and repeat successes.