How to Write an Article Critique Step-by-Step

Table of contents

- 1 What is an Article Critique Writing?

- 2 How to Critique an Article: The Main Steps

- 3 Article Critique Outline

- 4 Article Critique Formatting

- 5 How to Write a Journal Article Critique

- 6 How to Write a Research Article Critique

- 7 Research Methods in Article Critique Writing

- 8 Tips for writing an Article Critique

Do you know how to critique an article? If not, don’t worry – this guide will walk you through the writing process step-by-step. First, we’ll discuss what a research article critique is and its importance. Then, we’ll outline the key points to consider when critiquing a scientific article. Finally, we’ll provide a step-by-step guide on how to write an article critique including introduction, body and summary. Read more to get the main idea of crafting a critique paper.

What is an Article Critique Writing?

An article critique is a formal analysis and evaluation of a piece of writing. It is often written in response to a particular text but can also be a response to a book, a movie, or any other form of writing. There are many different types of review articles . Before writing an article critique, you should have an idea about each of them.

To start writing a good critique, you must first read the article thoroughly and examine and make sure you understand the article’s purpose. Then, you should outline the article’s key points and discuss how well they are presented. Next, you should offer your comments and opinions on the article, discussing whether you agree or disagree with the author’s points and subject. Finally, concluding your critique with a brief summary of your thoughts on the article would be best. Ensure that the general audience understands your perspective on the piece.

How to Critique an Article: The Main Steps

If you are wondering “what is included in an article critique,” the answer is:

An article critique typically includes the following:

- A brief summary of the article .

- A critical evaluation of the article’s strengths and weaknesses.

- A conclusion.

When critiquing an article, it is essential to critically read the piece and consider the author’s purpose and research strategies that the author chose. Next, provide a brief summary of the text, highlighting the author’s main points and ideas. Critique an article using formal language and relevant literature in the body paragraphs. Finally, describe the thesis statement, main idea, and author’s interpretations in your language using specific examples from the article. It is also vital to discuss the statistical methods used and whether they are appropriate for the research question. Make notes of the points you think need to be discussed, and also do a literature review from where the author ground their research. Offer your perspective on the article and whether it is well-written. Finally, provide background information on the topic if necessary.

When you are reading an article, it is vital to take notes and critique the text to understand it fully and to be able to use the information in it. Here are the main steps for critiquing an article:

- Read the piece thoroughly, taking notes as you go. Ensure you understand the main points and the author’s argument.

- Take a look at the author’s perspective. Is it powerful? Does it back up the author’s point of view?

- Carefully examine the article’s tone. Is it biased? Are you being persuaded by the author in any way?

- Look at the structure. Is it well organized? Does it make sense?

- Consider the writing style. Is it clear? Is it well-written?

- Evaluate the sources the author uses. Are they credible?

- Think about your own opinion. With what do you concur or disagree? Why?

Article Critique Outline

When assigned an article critique, your instructor asks you to read and analyze it and provide feedback. A specific format is typically followed when writing an article critique.

An article critique usually has three sections: an introduction, a body, and a conclusion.

- The introduction of your article critique should have a summary and key points.

- The critique’s main body should thoroughly evaluate the piece, highlighting its strengths and weaknesses, and state your ideas and opinions with supporting evidence.

- The conclusion should restate your research and describe your opinion.

You should provide your analysis rather than simply agreeing or disagreeing with the author. When writing an article review , it is essential to be objective and critical. Describe your perspective on the subject and create an article review summary. Be sure to use proper grammar, spelling, and punctuation, write it in the third person, and cite your sources.

Article Critique Formatting

When writing an article critique, you should follow a few formatting guidelines. The importance of using a proper format is to make your review clear and easy to read.

Make sure to use double spacing throughout your critique. It will make it easy to understand and read for your instructor.

Indent each new paragraph. It will help to separate your critique into different sections visually.

Use headings to organize your critique. Your introduction, body, and conclusion should stand out. It will make it easy for your instructor to follow your thoughts.

Use standard fonts, such as Times New Roman or Arial. It will make your critique easy to read.

Use 12-point font size. It will ensure that your critique is easy to read.

How to Write a Journal Article Critique

When critiquing a journal article, there are a few key points to keep in mind:

- Good critiques should be objective, meaning that the author’s ideas and arguments should be evaluated without personal bias.

- Critiques should be critical, meaning that all aspects of the article should be examined, including the author’s introduction, main ideas, and discussion.

- Critiques should be informative, providing the reader with a clear understanding of the article’s strengths and weaknesses.

When critiquing a research article, evaluating the author’s argument and the evidence they present is important. The author should state their thesis or the main point in the introductory paragraph. You should explain the article’s main ideas and evaluate the evidence critically. In the discussion section, the author should explain the implications of their findings and suggest future research.

It is also essential to keep a critical eye when reading scientific articles. In order to be credible, the scientific article must be based on evidence and previous literature. The author’s argument should be well-supported by data and logical reasoning.

How to Write a Research Article Critique

When you are assigned a research article, the first thing you need to do is read the piece carefully. Make sure you understand the subject matter and the author’s chosen approach. Next, you need to assess the importance of the author’s work. What are the key findings, and how do they contribute to the field of research?

Finally, you need to provide a critical point-by-point analysis of the article. This should include discussing the research questions, the main findings, and the overall impression of the scientific piece. In conclusion, you should state whether the text is good or bad. Read more to get an idea about curating a research article critique. But if you are not confident, you can ask “ write my papers ” and hire a professional to craft a critique paper for you. Explore your options online and get high-quality work quickly.

However, test yourself and use the following tips to write a research article critique that is clear, concise, and properly formatted.

- Take notes while you read the text in its entirety. Right down each point you agree and disagree with.

- Write a thesis statement that concisely and clearly outlines the main points.

- Write a paragraph that introduces the article and provides context for the critique.

- Write a paragraph for each of the following points, summarizing the main points and providing your own analysis:

- The purpose of the study

- The research question or questions

- The methods used

- The outcomes

- The conclusions were drawn by the author(s)

- Mention the strengths and weaknesses of the piece in a separate paragraph.

- Write a conclusion that summarizes your thoughts about the article.

- Free unlimited checks

- All common file formats

- Accurate results

- Intuitive interface

Research Methods in Article Critique Writing

When writing an article critique, it is important to use research methods to support your arguments. There are a variety of research methods that you can use, and each has its strengths and weaknesses. In this text, we will discuss four of the most common research methods used in article critique writing: quantitative research, qualitative research, systematic reviews, and meta-analysis.

Quantitative research is a research method that uses numbers and statistics to analyze data. This type of research is used to test hypotheses or measure a treatment’s effects. Quantitative research is normally considered more reliable than qualitative research because it considers a large amount of information. But, it might be difficult to find enough data to complete it properly.

Qualitative research is a research method that uses words and interviews to analyze data. This type of research is used to understand people’s thoughts and feelings. Qualitative research is usually more reliable than quantitative research because it is less likely to be biased. Though it is more expensive and tedious.

Systematic reviews are a type of research that uses a set of rules to search for and analyze studies on a particular topic. Some think that systematic reviews are more reliable than other research methods because they use a rigorous process to find and analyze studies. However, they can be pricy and long to carry out.

Meta-analysis is a type of research that combines several studies’ results to understand a treatment’s overall effect better. Meta-analysis is generally considered one of the most reliable type of research because it uses data from several approved studies. Conversely, it involves a long and costly process.

Are you still struggling to understand the critique of an article concept? You can contact an online review writing service to get help from skilled writers. You can get custom, and unique article reviews easily.

Tips for writing an Article Critique

It’s crucial to keep in mind that you’re not just sharing your opinion of the content when you write an article critique. Instead, you are providing a critical analysis, looking at its strengths and weaknesses. In order to write a compelling critique, you should follow these tips: Take note carefully of the essential elements as you read it.

- Make sure that you understand the thesis statement.

- Write down your thoughts, including strengths and weaknesses.

- Use evidence from to support your points.

- Create a clear and concise critique, making sure to avoid giving your opinion.

It is important to be clear and concise when creating an article critique. You should avoid giving your opinion and instead focus on providing a critical analysis. You should also use evidence from the article to support your points.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

Making sense of research: A guide for critiquing a paper

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Nursing, Griffith University, Meadowbrook, Queensland.

- PMID: 16114192

- DOI: 10.5172/conu.14.1.38

Learning how to critique research articles is one of the fundamental skills of scholarship in any discipline. The range, quantity and quality of publications available today via print, electronic and Internet databases means it has become essential to equip students and practitioners with the prerequisites to judge the integrity and usefulness of published research. Finding, understanding and critiquing quality articles can be a difficult process. This article sets out some helpful indicators to assist the novice to make sense of research.

Publication types

- Data Interpretation, Statistical

- Research Design

- Review Literature as Topic

- All eBooks & Audiobooks

- Academic eBook Collection

- Home Grown eBook Collection

- Off-Campus Access

- Literature Resource Center

- Opposing Viewpoints

- ProQuest Central

- Course Guides

- Citing Sources

- Library Research

- Websites by Topic

- Book-a-Librarian

- Research Tutorials

- Use the Catalog

- Use Databases

- Use Films on Demand

- Use Home Grown eBooks

- Use NC LIVE

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary vs. Secondary

- Scholarly vs. Popular

- Make an Appointment

- Writing Tools

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Summaries, Reviews & Critiques

- Writing Center

Service Alert

Article Summaries, Reviews & Critiques

- Writing an article SUMMARY

- Writing an article REVIEW

Writing an article CRITIQUE

- Citing Sources This link opens in a new window

- About RCC Library

Text: 336-308-8801

Email: [email protected]

Call: 336-633-0204

Schedule: Book-a-Librarian

Like us on Facebook

Links on this guide may go to external web sites not connected with Randolph Community College. Their inclusion is not an endorsement by Randolph Community College and the College is not responsible for the accuracy of their content or the security of their site.

A critique asks you to evaluate an article and the author’s argument. You will need to look critically at what the author is claiming, evaluate the research methods, and look for possible problems with, or applications of, the researcher’s claims.

Introduction

Give an overview of the author’s main points and how the author supports those points. Explain what the author found and describe the process they used to arrive at this conclusion.

Body Paragraphs

Interpret the information from the article:

- Does the author review previous studies? Is current and relevant research used?

- What type of research was used – empirical studies, anecdotal material, or personal observations?

- Was the sample too small to generalize from?

- Was the participant group lacking in diversity (race, gender, age, education, socioeconomic status, etc.)

- For instance, volunteers gathered at a health food store might have different attitudes about nutrition than the population at large.

- How useful does this work seem to you? How does the author suggest the findings could be applied and how do you believe they could be applied?

- How could the study have been improved in your opinion?

- Does the author appear to have any biases (related to gender, race, class, or politics)?

- Is the writing clear and easy to follow? Does the author’s tone add to or detract from the article?

- How useful are the visuals (such as tables, charts, maps, photographs) included, if any? How do they help to illustrate the argument? Are they confusing or hard to read?

- What further research might be conducted on this subject?

Try to synthesize the pieces of your critique to emphasize your own main points about the author’s work, relating the researcher’s work to your own knowledge or to topics being discussed in your course.

From the Center for Academic Excellence (opens in a new window), University of Saint Joseph Connecticut

Additional Resources

All links open in a new window.

Writing an Article Critique (from The University of Arizona Global Campus Writing Center)

How to Critique an Article (from Essaypro.com)

How to Write an Article Critique (from EliteEditing.com.au)

- << Previous: Writing an article REVIEW

- Next: Citing Sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 15, 2024 9:32 AM

- URL: https://libguides.randolph.edu/summaries

You are using an outdated browser

Unfortunately Ausmed.com does not support your browser. Please upgrade your browser to continue.

How to Critique a Research Article

Published: 01 October 2023

Let's briefly examine some basic pointers on how to perform a literature review.

If you've managed to get your hands on peer-reviewed articles, then you may wonder why it is necessary for you to perform your own article critique. Surely the article will be of good quality if it has made it through the peer-review process?

Unfortunately, this is not always the case.

Publication bias can occur when editors only accept manuscripts that have a bearing on the direction of their own research, or reject manuscripts with negative findings. Additionally, not all peer reviewers have expert knowledge on certain subject matters , which can introduce bias and sometimes a conflict of interest.

Performing your own critical analysis of an article allows you to consider its value to you and to your workplace.

Critical evaluation is defined as a systematic way of considering the truthfulness of a piece of research, its results and how relevant and applicable they are.

How to Critique

It can be a little overwhelming trying to critique an article when you're not sure where to start. Considering the article under the following headings may be of some use:

Title of Study/Research

You may be a better judge of this after reading the article, but the title should succinctly reflect the content of the work, stimulating readers' interest.

Three to six keywords that encapsulate the main topics of the research will have been drawn from the body of the article.

Introduction

This should include:

- Evidence of a literature review that is relevant and recent, critically appraising other works rather than merely describing them

- Background information on the study to orientate the reader to the problem

- Hypothesis or aims of the study

- Rationale for the study that justifies its need, i.e. to explore an un-investigated gap in the literature.

Materials and Methods

Similar to a recipe, the description of materials and methods will allow others to replicate the study elsewhere if needed. It should both contain and justify the exact specifications of selection criteria, sample size, response rate and any statistics used. This will demonstrate how the study is capable of achieving its aims. Things to consider in this section are:

- What sort of sampling technique and size was used?

- What proportion of the eligible sample participated? (e.g. '553 responded to a survey sent to 750 medical technologists'

- Were all eligible groups sampled? (e.g. was the survey sent only in English?)

- What were the strengths and weaknesses of the study?

- Were there threats to the reliability and validity of the study, and were these controlled for?

- Were there any obvious biases?

- If a trial was undertaken, was it randomised, case-controlled, blinded or double-blinded?

Results should be statistically analysed and presented in a way that an average reader of the journal will understand. Graphs and tables should be clear and promote clarity of the text. Consider whether:

- There were any major omissions in the results, which could indicate bias

- Percentages have been used to disguise small sample sizes

- The data generated is consistent with the data collected.

Negative results are just as relevant as research that produces positive results (but, as mentioned previously, may be omitted in publication due to editorial bias).

This should show insight into the meaning and significance of the research findings. It should not introduce any new material but should address how the aims of the study have been met. The discussion should use previous research work and theoretical concepts as the context in which the new study can be interpreted. Any limitations of the study, including bias, should be clearly presented. You will need to evaluate whether the author has clearly interpreted the results of the study, or whether the results could be interpreted another way.

Conclusions

These should be clearly stated and will only be valid if the study was reliable, valid and used a representative sample size. There may also be recommendations for further research.

These should be relevant to the study, be up-to-date, and should provide a comprehensive list of citations within the text.

Final Thoughts

Undertaking a critique of a research article may seem challenging at first, but will help you to evaluate whether the article has relevance to your own practice and workplace. Reading a single article can act as a springboard into researching the topic more widely, and aids in ensuring your nursing practice remains current and is supported by existing literature.

- Marshall, G 2005, ‘Critiquing a Research Article’, Radiography , vol. 11, no. 1, viewed 2 October 2023, https://www.radiographyonline.com/article/S1078-8174(04)00119-1/fulltext

Sarah Vogel View profile

Help and feedback, publications.

Ausmed Education is a Trusted Information Partner of Healthdirect Australia. Verify here .

- Queen's University Library

- Research Guides

How to Critique an Article (Psychology)

- Introduction

Participants

- Is the sample size adequate to find the effect? Are power analyses mentioned?

- Are there equal numbers of males and females?

- Are there a range of socioeconomic strata and ethnicities?

- For this class, is the diagnosis confirmed?

- Where were the participants obtained from, and are they a biased sample?

- If it is an experimental design, was true random assignment done (random number generator)?

- Are the measures widely used in the field?

- Are the measures reliable and valid?

- Are they appropriate for the group or age being studied (i.e. not too difficult or too easy)?

- Are all the measures explained adequately?

- Do the measures seem to have face validity -- that is, do they measure what the authors say the variable of interest is in an adequate fashion?

- Last Updated: Nov 5, 2021 9:46 AM

- Subjects: Psychology

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Critical Reviews

How to Write an Article Review (With Examples)

Last Updated: April 24, 2024 Fact Checked

Preparing to Write Your Review

Writing the article review, sample article reviews, expert q&a.

This article was co-authored by Jake Adams . Jake Adams is an academic tutor and the owner of Simplifi EDU, a Santa Monica, California based online tutoring business offering learning resources and online tutors for academic subjects K-College, SAT & ACT prep, and college admissions applications. With over 14 years of professional tutoring experience, Jake is dedicated to providing his clients the very best online tutoring experience and access to a network of excellent undergraduate and graduate-level tutors from top colleges all over the nation. Jake holds a BS in International Business and Marketing from Pepperdine University. There are 12 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 3,107,156 times.

An article review is both a summary and an evaluation of another writer's article. Teachers often assign article reviews to introduce students to the work of experts in the field. Experts also are often asked to review the work of other professionals. Understanding the main points and arguments of the article is essential for an accurate summation. Logical evaluation of the article's main theme, supporting arguments, and implications for further research is an important element of a review . Here are a few guidelines for writing an article review.

Education specialist Alexander Peterman recommends: "In the case of a review, your objective should be to reflect on the effectiveness of what has already been written, rather than writing to inform your audience about a subject."

Article Review 101

- Read the article very closely, and then take time to reflect on your evaluation. Consider whether the article effectively achieves what it set out to.

- Write out a full article review by completing your intro, summary, evaluation, and conclusion. Don't forget to add a title, too!

- Proofread your review for mistakes (like grammar and usage), while also cutting down on needless information.

- Article reviews present more than just an opinion. You will engage with the text to create a response to the scholarly writer's ideas. You will respond to and use ideas, theories, and research from your studies. Your critique of the article will be based on proof and your own thoughtful reasoning.

- An article review only responds to the author's research. It typically does not provide any new research. However, if you are correcting misleading or otherwise incorrect points, some new data may be presented.

- An article review both summarizes and evaluates the article.

- Summarize the article. Focus on the important points, claims, and information.

- Discuss the positive aspects of the article. Think about what the author does well, good points she makes, and insightful observations.

- Identify contradictions, gaps, and inconsistencies in the text. Determine if there is enough data or research included to support the author's claims. Find any unanswered questions left in the article.

- Make note of words or issues you don't understand and questions you have.

- Look up terms or concepts you are unfamiliar with, so you can fully understand the article. Read about concepts in-depth to make sure you understand their full context.

- Pay careful attention to the meaning of the article. Make sure you fully understand the article. The only way to write a good article review is to understand the article.

- With either method, make an outline of the main points made in the article and the supporting research or arguments. It is strictly a restatement of the main points of the article and does not include your opinions.

- After putting the article in your own words, decide which parts of the article you want to discuss in your review. You can focus on the theoretical approach, the content, the presentation or interpretation of evidence, or the style. You will always discuss the main issues of the article, but you can sometimes also focus on certain aspects. This comes in handy if you want to focus the review towards the content of a course.

- Review the summary outline to eliminate unnecessary items. Erase or cross out the less important arguments or supplemental information. Your revised summary can serve as the basis for the summary you provide at the beginning of your review.

- What does the article set out to do?

- What is the theoretical framework or assumptions?

- Are the central concepts clearly defined?

- How adequate is the evidence?

- How does the article fit into the literature and field?

- Does it advance the knowledge of the subject?

- How clear is the author's writing? Don't: include superficial opinions or your personal reaction. Do: pay attention to your biases, so you can overcome them.

- For example, in MLA , a citation may look like: Duvall, John N. "The (Super)Marketplace of Images: Television as Unmediated Mediation in DeLillo's White Noise ." Arizona Quarterly 50.3 (1994): 127-53. Print. [9] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- For example: The article, "Condom use will increase the spread of AIDS," was written by Anthony Zimmerman, a Catholic priest.

- Your introduction should only be 10-25% of your review.

- End the introduction with your thesis. Your thesis should address the above issues. For example: Although the author has some good points, his article is biased and contains some misinterpretation of data from others’ analysis of the effectiveness of the condom.

- Use direct quotes from the author sparingly.

- Review the summary you have written. Read over your summary many times to ensure that your words are an accurate description of the author's article.

- Support your critique with evidence from the article or other texts.

- The summary portion is very important for your critique. You must make the author's argument clear in the summary section for your evaluation to make sense.

- Remember, this is not where you say if you liked the article or not. You are assessing the significance and relevance of the article.

- Use a topic sentence and supportive arguments for each opinion. For example, you might address a particular strength in the first sentence of the opinion section, followed by several sentences elaborating on the significance of the point.

- This should only be about 10% of your overall essay.

- For example: This critical review has evaluated the article "Condom use will increase the spread of AIDS" by Anthony Zimmerman. The arguments in the article show the presence of bias, prejudice, argumentative writing without supporting details, and misinformation. These points weaken the author’s arguments and reduce his credibility.

- Make sure you have identified and discussed the 3-4 key issues in the article.

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://libguides.cmich.edu/writinghelp/articlereview

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4548566/

- ↑ Jake Adams. Academic Tutor & Test Prep Specialist. Expert Interview. 24 July 2020.

- ↑ https://guides.library.queensu.ca/introduction-research/writing/critical

- ↑ https://www.iup.edu/writingcenter/writing-resources/organization-and-structure/creating-an-outline.html

- ↑ https://writing.umn.edu/sws/assets/pdf/quicktips/titles.pdf

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/mla_style/mla_formatting_and_style_guide/mla_works_cited_periodicals.html

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4548565/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/593/2014/06/How_to_Summarize_a_Research_Article1.pdf

- ↑ https://www.uis.edu/learning-hub/writing-resources/handouts/learning-hub/how-to-review-a-journal-article

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/editing-and-proofreading/

About This Article

If you have to write an article review, read through the original article closely, taking notes and highlighting important sections as you read. Next, rewrite the article in your own words, either in a long paragraph or as an outline. Open your article review by citing the article, then write an introduction which states the article’s thesis. Next, summarize the article, followed by your opinion about whether the article was clear, thorough, and useful. Finish with a paragraph that summarizes the main points of the article and your opinions. To learn more about what to include in your personal critique of the article, keep reading the article! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Prince Asiedu-Gyan

Apr 22, 2022

Did this article help you?

Sammy James

Sep 12, 2017

Juabin Matey

Aug 30, 2017

Vanita Meghrajani

Jul 21, 2016

Nov 27, 2018

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.1: What’s a Critique and Why Does it Matter?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 6510

- Steven D. Krause

- Eastern Michigan University

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Critiques evaluate and analyze a wide variety of things (texts, images, performances, etc.) based on reasons or criteria. Sometimes, people equate the notion of “critique” to “criticism,” which usually suggests a negative interpretation. These terms are easy to confuse, but I want to be clear that critique and criticize don’t mean the same thing. A negative critique might be said to be “criticism” in the way we often understand the term “to criticize,” but critiques can be positive too.

We’re all familiar with one of the most basic forms of critique: reviews (film reviews, music reviews, art reviews, book reviews, etc.). Critiques in the form of reviews tend to have a fairly simple and particular point: whether or not something is “good” or “bad.”

Academic critiques are similar to the reviews we see in popular sources in that critique writers are trying to make a particular point about whatever it is that they are critiquing. But there are some differences between the sorts of critiques we read in academic sources versus the ones we read in popular sources.

- The subjects of academic critiques tend to be other academic writings and they frequently appear in scholarly journals.

- Academic critiques frequently go further in making an argument beyond a simple assessment of the quality of a particular book, film, performance, or work of art. Academic critique writers will often compare and discuss several works that are similar to each other to make some larger point. In other words, instead of simply commenting on whether something was good or bad, academic critiques tend to explore issues and ideas in ways that are more complicated than merely “good” or “bad.”

The main focus of this chapter is the value of writing critiques as a part of the research writing process. Critiquing writing is important because in order to write a good critique you need to critically read : that is, you need to closely read and understand whatever it is you are critiquing, you need to apply appropriate criteria in order evaluate it, you need to summarize it, and to ultimately make some sort of point about the text you are critiquing.

These skills-- critically and closely reading, summarizing, creating and applying criteria, and then making an evaluation-- are key to The Process of Research Writing, and they should help you as you work through the process of research writing.

In this chapter, I’ve provided a “step-by-step” process for making a critique. I would encourage you to quickly read or skim through this chapter first, and then go back and work through the steps and exercises describe.

Selecting the right text to critique

The first step in writing a critique is selecting a text to critique. For the purposes of this writing exercise, you should check with your teacher for guidelines on what text to pick. If you are doing an annotated bibliography as part of your research project (see chapter 6, “The Annotated Bibliography Exercise”), then you are might find more materials that will work well for this project as you continuously research.

Short and simple newspaper articles, while useful as part of the research process, can be difficult to critique since they don’t have the sort of detail that easily allows for a critical reading. On the other hand, critiquing an entire book is probably a more ambitious task than you are likely to have time or energy for with this exercise. Instead, consider critiquing one of the more fully developed texts you’ve come across in your research: an in-depth examination from a news magazine, a chapter from a scholarly book, a report on a research study or experiment, or an analysis published in an academic journal. These more complex essays usually present more opportunities for issues to critique.

Depending on your teacher’s assignment, the “text” you critique might include something that isn’t in writing: a movie, a music CD, a multimedia presentation, a computer game, a painting, etc. As is the case with more traditional writings, you want to select a text that has enough substance to it so that it stands up to a critical reading.

Exercise 7.1

Pick out at least three different possibilities for texts that you could critique for this exercise. If you’ve already started work on your research and an annotated bibliography for your research topic, you should consider those pieces of research as possibilities. Working alone or in small groups, consider the potential of each text. Here are some questions to think about:

- Does the text provide in-depth information? How long is it? Does it include a “works cited” or bibliography section?

- What is the source of the text? Does it come from an academic, professional, or scholarly publication?

- Does the text advocate a particular position? What is it, and do you agree or disagree with the text?

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Turk J Urol

- v.39(Suppl 1); 2013 Sep

How to write a review article?

In the medical sciences, the importance of review articles is rising. When clinicians want to update their knowledge and generate guidelines about a topic, they frequently use reviews as a starting point. The value of a review is associated with what has been done, what has been found and how these findings are presented. Before asking ‘how,’ the question of ‘why’ is more important when starting to write a review. The main and fundamental purpose of writing a review is to create a readable synthesis of the best resources available in the literature for an important research question or a current area of research. Although the idea of writing a review is attractive, it is important to spend time identifying the important questions. Good review methods are critical because they provide an unbiased point of view for the reader regarding the current literature. There is a consensus that a review should be written in a systematic fashion, a notion that is usually followed. In a systematic review with a focused question, the research methods must be clearly described. A ‘methodological filter’ is the best method for identifying the best working style for a research question, and this method reduces the workload when surveying the literature. An essential part of the review process is differentiating good research from bad and leaning on the results of the better studies. The ideal way to synthesize studies is to perform a meta-analysis. In conclusion, when writing a review, it is best to clearly focus on fixed ideas, to use a procedural and critical approach to the literature and to express your findings in an attractive way.

The importance of review articles in health sciences is increasing day by day. Clinicians frequently benefit from review articles to update their knowledge in their field of specialization, and use these articles as a starting point for formulating guidelines. [ 1 , 2 ] The institutions which provide financial support for further investigations resort to these reviews to reveal the need for these researches. [ 3 ] As is the case with all other researches, the value of a review article is related to what is achieved, what is found, and the way of communicating this information. A few studies have evaluated the quality of review articles. Murlow evaluated 50 review articles published in 1985, and 1986, and revealed that none of them had complied with clear-cut scientific criteria. [ 4 ] In 1996 an international group that analyzed articles, demonstrated the aspects of review articles, and meta-analyses that had not complied with scientific criteria, and elaborated QUOROM (QUality Of Reporting Of Meta-analyses) statement which focused on meta-analyses of randomized controlled studies. [ 5 ] Later on this guideline was updated, and named as PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). [ 6 ]

Review articles are divided into 2 categories as narrative, and systematic reviews. Narrative reviews are written in an easily readable format, and allow consideration of the subject matter within a large spectrum. However in a systematic review, a very detailed, and comprehensive literature surveying is performed on the selected topic. [ 7 , 8 ] Since it is a result of a more detailed literature surveying with relatively lesser involvement of author’s bias, systematic reviews are considered as gold standard articles. Systematic reviews can be diivded into qualitative, and quantitative reviews. In both of them detailed literature surveying is performed. However in quantitative reviews, study data are collected, and statistically evaluated (ie. meta-analysis). [ 8 ]

Before inquring for the method of preparation of a review article, it is more logical to investigate the motivation behind writing the review article in question. The fundamental rationale of writing a review article is to make a readable synthesis of the best literature sources on an important research inquiry or a topic. This simple definition of a review article contains the following key elements:

- The question(s) to be dealt with

- Methods used to find out, and select the best quality researches so as to respond to these questions.

- To synthetize available, but quite different researches

For the specification of important questions to be answered, number of literature references to be consulted should be more or less determined. Discussions should be conducted with colleagues in the same area of interest, and time should be reserved for the solution of the problem(s). Though starting to write the review article promptly seems to be very alluring, the time you spend for the determination of important issues won’t be a waste of time. [ 9 ]

The PRISMA statement [ 6 ] elaborated to write a well-designed review articles contains a 27-item checklist ( Table 1 ). It will be reasonable to fulfill the requirements of these items during preparation of a review article or a meta-analysis. Thus preparation of a comprehensible article with a high-quality scientific content can be feasible.

PRISMA statement: A 27-item checklist

Contents and format

Important differences exist between systematic, and non-systematic reviews which especially arise from methodologies used in the description of the literature sources. A non-systematic review means use of articles collected for years with the recommendations of your colleagues, while systematic review is based on struggles to search for, and find the best possible researches which will respond to the questions predetermined at the start of the review.

Though a consensus has been reached about the systematic design of the review articles, studies revealed that most of them had not been written in a systematic format. McAlister et al. analyzed review articles in 6 medical journals, and disclosed that in less than one fourth of the review articles, methods of description, evaluation or synthesis of evidence had been provided, one third of them had focused on a clinical topic, and only half of them had provided quantitative data about the extend of the potential benefits. [ 10 ]

Use of proper methodologies in review articles is important in that readers assume an objective attitude towards updated information. We can confront two problems while we are using data from researches in order to answer certain questions. Firstly, we can be prejudiced during selection of research articles or these articles might be biased. To minimize this risk, methodologies used in our reviews should allow us to define, and use researches with minimal degree of bias. The second problem is that, most of the researches have been performed with small sample sizes. In statistical methods in meta-analyses, available researches are combined to increase the statistical power of the study. The problematic aspect of a non-systematic review is that our tendency to give biased responses to the questions, in other words we apt to select the studies with known or favourite results, rather than the best quality investigations among them.

As is the case with many research articles, general format of a systematic review on a single subject includes sections of Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion ( Table 2 ).

Structure of a systematic review

Preparation of the review article

Steps, and targets of constructing a good review article are listed in Table 3 . To write a good review article the items in Table 3 should be implemented step by step. [ 11 – 13 ]

Steps of a systematic review

The research question

It might be helpful to divide the research question into components. The most prevalently used format for questions related to the treatment is PICO (P - Patient, Problem or Population; I-Intervention; C-appropriate Comparisons, and O-Outcome measures) procedure. For example In female patients (P) with stress urinary incontinence, comparisons (C) between transobturator, and retropubic midurethral tension-free band surgery (I) as for patients’ satisfaction (O).

Finding Studies

In a systematic review on a focused question, methods of investigation used should be clearly specified.

Ideally, research methods, investigated databases, and key words should be described in the final report. Different databases are used dependent on the topic analyzed. In most of the clinical topics, Medline should be surveyed. However searching through Embase and CINAHL can be also appropriate.

While determining appropriate terms for surveying, PICO elements of the issue to be sought may guide the process. Since in general we are interested in more than one outcome, P, and I can be key elements. In this case we should think about synonyms of P, and I elements, and combine them with a conjunction AND.

One method which might alleviate the workload of surveying process is “methodological filter” which aims to find the best investigation method for each research question. A good example of this method can be found in PubMed interface of Medline. The Clinical Queries tool offers empirically developed filters for five different inquiries as guidelines for etiology, diagnosis, treatment, prognosis or clinical prediction.

Evaluation of the Quality of the Study

As an indispensable component of the review process is to discriminate good, and bad quality researches from each other, and the outcomes should be based on better qualified researches, as far as possible. To achieve this goal you should know the best possible evidence for each type of question The first component of the quality is its general planning/design of the study. General planning/design of a cohort study, a case series or normal study demonstrates variations.

A hierarchy of evidence for different research questions is presented in Table 4 . However this hierarchy is only a first step. After you find good quality research articles, you won’t need to read all the rest of other articles which saves you tons of time. [ 14 ]

Determination of levels of evidence based on the type of the research question

Formulating a Synthesis

Rarely all researches arrive at the same conclusion. In this case a solution should be found. However it is risky to make a decision based on the votes of absolute majority. Indeed, a well-performed large scale study, and a weakly designed one are weighed on the same scale. Therefore, ideally a meta-analysis should be performed to solve apparent differences. Ideally, first of all, one should be focused on the largest, and higher quality study, then other studies should be compared with this basic study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, during writing process of a review article, the procedures to be achieved can be indicated as follows: 1) Get rid of fixed ideas, and obsessions from your head, and view the subject from a large perspective. 2) Research articles in the literature should be approached with a methodological, and critical attitude and 3) finally data should be explained in an attractive way.

How to Critique an Article: Mastering the Article Evaluation Process

Did you know that approximately 4.6 billion pieces of content are produced every day? From news articles and blog posts to scholarly papers and social media updates, the digital landscape is flooded with information at an unprecedented rate. In this age of information overload, honing the skill of articles critique has never been more crucial. Whether you're seeking to bolster your academic prowess, stay well-informed, or improve your writing, mastering the art of article critique is a powerful tool to navigate the vast sea of information and discern the pearls of wisdom.

How to Critique an Article: Short Description

In this article, we will equip you with valuable tips and techniques to become an insightful evaluator of written content. We present a real-life article critique example to guide your learning process and help you develop your unique critique style. Additionally, we explore the key differences between critiquing scientific articles and journals. Whether you're a student, researcher, or avid reader, this guide will empower you to navigate the vast ocean of information with confidence and discernment. Still, have questions? Don't worry! We've got you covered with a helpful FAQ section to address any lingering doubts. Get ready to unleash your analytical prowess and uncover the true potential of every article that comes your way!

What Is an Article Critique: Understanding The Power of Evaluation

An article critique is a valuable skill that involves carefully analyzing and evaluating a written piece, such as a journal article, blog post, or news article. It goes beyond mere summarization and delves into the deeper layers of the content, examining its strengths, weaknesses, and overall effectiveness. Think of it as an engaging conversation with the author, where you provide constructive feedback and insights.

For instance, let's consider a scenario where you're critiquing a research paper on climate change. Instead of simply summarizing the findings, you would scrutinize the methodology, data interpretation, and potential biases, offering thoughtful observations to enrich the discussion. Through the process of writing an article critique, you develop a critical eye, honing your ability to appreciate well-crafted work while also identifying areas for improvement.

In the following sections, our ' write my paper ' experts will uncover valuable tips on and key points on how to write a stellar critique, so let's explore more!

Unveiling the Key Aims of Writing an Article Critique

Writing an article critique serves several essential purposes that go beyond a simple review or summary. When engaging in the art of critique, as when you learn how to write a review article , you embark on a journey of in-depth analysis, sharpening your critical thinking skills and contributing to the academic and intellectual discourse. Primarily, an article critique allows you to:

%20(3).webp)

- Evaluate the Content : By critiquing an article, you delve into its content, structure, and arguments, assessing its credibility and relevance.

- Strengthen Your Critical Thinking : This practice hones your ability to identify strengths and weaknesses in written works, fostering a deeper understanding of complex topics and critical evaluation skills.

- Engage in Scholarly Dialogue : Your critique contributes to the ongoing academic conversation, offering valuable insights and thoughtful observations to the existing body of knowledge.

- Enhance Writing Skills : By analyzing and providing feedback, you develop a keen eye for effective writing techniques, benefiting your own writing endeavors.

- Promote Continuous Learning : Through the writing process, you continually refine your analytical abilities, becoming an avid and astute learner in the pursuit of knowledge.

How to Critique an Article: Steps to Follow

The process of crafting an article critique may seem overwhelming, especially when dealing with intricate academic writing. However, fear not, for it is more straightforward than it appears! To excel in this art, all you require is a clear starting point and the skill to align your critique with the complexities of the content. To help you on your journey, follow these 3 simple steps and unlock the potential to provide insightful evaluations:

%20(4).webp)

Step 1: Read the Article

The first and most crucial step when wondering how to do an article critique is to thoroughly read and absorb its content. As you delve into the written piece, consider these valuable tips from our custom essay writer to make your reading process more effective:

- Take Notes : Keep a notebook or digital document handy while reading. Jot down key points, noteworthy arguments, and any questions or observations that arise.

- Annotate the Text : Underline or highlight significant passages, quotes, or sections that stand out to you. Use different colors to differentiate between positive aspects and areas that may need improvement.

- Consider the Author's Purpose : Reflect on the author's main critical point and the intended audience. Much like an explanatory essay , evaluate how effectively the article conveys its message to the target readership.

Now, let's say you are writing an article critique on climate change. While reading, you come across a compelling quote from a renowned environmental scientist highlighting the urgency of addressing global warming. By taking notes and underlining this impactful quote, you can later incorporate it into your critique as evidence of the article's effectiveness in conveying the severity of the issue.

Step 2: Take Notes/ Make sketches

Once you've thoroughly read the article, it's time to capture your thoughts and observations by taking comprehensive notes or creating sketches. This step plays a crucial role in organizing your critique and ensuring you don't miss any critical points. Here's how to make the most out of this process:

- Highlight Key Arguments : Identify the main arguments presented by the author and highlight them in your notes. This will help you focus on the core ideas that shape the article.

- Record Supporting Evidence : Take note of any evidence, examples, or data the author uses to support their arguments. Assess the credibility and effectiveness of this evidence in bolstering their claims.

- Examine Structure and Flow : Pay attention to the article's structure and how each section flows into the next. Analyze how well the author transitions between ideas and whether the organization enhances or hinders the reader's understanding.

- Create Visual Aids : If you're a visual learner, consider using sketches or diagrams to map out the article's key points and their relationships. Visual representations can aid in better grasping the content's structure and complexities.

Step 3: Format Your Paper

Once you've gathered your notes and insights, it's time to give structure to your article critique. Proper formatting ensures your critique is organized, coherent, and easy to follow. Here are essential tips for formatting an article critique effectively:

- Introduction : Begin with a clear and engaging introduction that provides context for the article you are critiquing. Include the article's title, author's name, publication details, and a brief overview of the main theme or thesis.

- Thesis Statement : Present a strong and concise thesis statement that conveys your overall assessment of the article. Your thesis should reflect whether you found the article compelling, convincing, or in need of improvement.

- Body Paragraphs : Organize your critique into well-structured body paragraphs. Each paragraph should address a specific point or aspect of the article, supported by evidence and examples from your notes.

- Use Evidence : Back up your critique with evidence from the article itself. Quote relevant passages, cite examples, and reference data to strengthen your analysis and demonstrate your understanding of the article's content.

- Conclusion : Conclude your critique by summarizing your main points and reiterating your overall evaluation. Avoid introducing new arguments in the conclusion and instead provide a concise and compelling closing statement.

- Citation Style : If required, adhere to the specific citation style guidelines (e.g., APA, MLA) for in-text citations and the reference list. Properly crediting the original article and any additional sources you use in your critique is essential.

How to Critique a Journal Article: Mastering the Steps

So, you've been assigned the task of critiquing a journal article, and not sure where to start? Worry not, as we've prepared a comprehensive guide with different steps to help you navigate this process with confidence. Journal articles are esteemed sources of scholarly knowledge, and effectively critiquing them requires a systematic approach. Let's dive into the steps to expertly evaluate and analyze a journal article:

Step 1: Understanding the Research Context

Begin by familiarizing yourself with the broader research context in which the journal article is situated. Learn about the field, the topic's significance, and any previous relevant research. This foundational knowledge will provide a valuable backdrop for your journal article critique example.

Step 2: Evaluating the Article's Structure

Assess the article's overall structure and organization. Examine how the introduction sets the stage for the research and how the discussion flows logically from the methodology and results. A well-structured article enhances readability and comprehension.

Step 3: Analyzing the Research Methodology

Dive into the research methodology section, which outlines the approach used to gather and analyze data. Scrutinize the study's design, data collection methods, sample size, and any potential biases or limitations. Understanding the research process will enable you to gauge the article's reliability.

Step 4: Assessing the Data and Results

Examine the presentation of data and results in the article. Are the findings clear and effectively communicated? Look for any discrepancies between the data presented and the interpretations made by the authors.

Step 5: Analyzing the Discussion and Conclusions

Evaluate the discussion section, where the authors interpret their findings and place them in the broader context. Assess the soundness of their conclusions, considering whether they are adequately supported by the data.

Step 6: Considering Ethical Considerations

Reflect on any ethical considerations raised by the research. Assess whether the study respects the rights and privacy of participants and adheres to ethical guidelines.

Step 7: Identifying Strengths and Weaknesses

Identify the article's strengths, such as well-designed experiments, comprehensive, relevant literature reviews, or innovative approaches. Also, pinpoint any weaknesses, like gaps in the research, unclear explanations, or insufficient evidence.

Step 8: Offering Constructive Feedback

Provide constructive feedback to the authors, highlighting both positive aspects and areas for improvement for future research. Suggest ways to enhance the research methods, data analysis, or discussion to bolster its overall quality.

Step 9: Presenting Your Critique

Organize your critique into a well-structured paper, starting with an introduction that outlines the article's context and purpose. Develop a clear and focused thesis statement that conveys your assessment. Support your points with evidence from the article and other credible sources.

By following these steps on how to critique a journal article, you'll be well-equipped to craft a thoughtful and insightful piece, contributing to the scholarly discourse in your field of study!

Got an Article that Needs Some Serious Critiquing?

Don't sweat it! Our critique maestros are armed with wit, wisdom, and a dash of magic to whip that piece into shape.

An Article Critique: Journal Vs. Research

In the realm of academic writing, the terms 'journal article' and 'research paper' are often used interchangeably, which can lead to confusion about their differences. Understanding the distinctions between critiquing a research article and a journal piece is essential. Let's delve into the key characteristics that set apart a journal article from a research paper and explore how the critique process may differ for each:

Publication Scope:

- Journal Article: Presents focused and concise research findings or new insights within a specific subject area.

- Research Paper: Explores a broader range of topics and can cover extensive research on a particular subject.

Format and Structure:

- Journal Article: Follows a standardized format with sections such as abstract, introduction, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

- Research Paper: May not adhere to a specific format and allows flexibility in organizing content based on the research scope.

Depth of Analysis:

- Journal Article: Provides a more concise and targeted analysis of the research topic or findings.

- Research Paper: Offers a more comprehensive and in-depth analysis, often including extensive literature reviews and data analyses.

- Journal Article: Typically shorter in length, ranging from a few pages to around 10-15 pages.

- Research Paper: Tends to be longer, spanning from 20 to several hundred pages, depending on the research complexity.

Publication Type:

- Journal Article: Published in academic journals after undergoing rigorous peer review.

- Research Paper: May be published as a standalone work or as part of a thesis, dissertation, or academic report.

- Journal Article: Targeted at academics, researchers, and professionals within the specific field of study.

- Research Paper: Can cater to a broader audience, including students, researchers, policymakers, and the general public.

- Journal Article: Primarily aimed at sharing new research findings, contributing to academic discourse, and advancing knowledge in the field.

- Research Paper: Focuses on comprehensive exploration and analysis of a research topic, aiming to make a substantial contribution to the body of knowledge.

Appreciating these differences becomes paramount when engaging in the critique of these two forms of scholarly publications, as they each demand a unique approach and thoughtful consideration of their distinctive attributes. And if you find yourself desiring a flawlessly crafted research article critique example, entrusting the task to professional writers is always an excellent option – you can easily order essay that meets your needs.

Article Critique Example

Our collection of essay samples offers a comprehensive and practical illustration of the critique process, granting you access to valuable insights.

Tips on How to Critique an Article

Critiquing an article requires a keen eye, critical thinking, and a thoughtful approach to evaluating its content. To enhance your article critique skills and provide insightful analyses, consider incorporating these five original and practical tips into your process:

1. Analyze the Author's Bias : Be mindful of potential biases in the article, whether they are political, cultural, or personal. Consider how these biases may influence the author's perspective and the presentation of information. Evaluating the presence of bias enables you to discern the objectivity and credibility of the article's arguments.

2. Examine the Supporting Evidence : Scrutinize the quality and relevance of the evidence used to support the article's claims. Look for well-researched data, credible sources, and up-to-date statistics. Assess how effectively the author integrates evidence to build a compelling case for their arguments.

3. Consider the Audience's Perspective : Put yourself in the shoes of the intended audience and assess how well the article communicates its ideas. Consider whether the language, tone, and level of complexity are appropriate for the target readership. A well-tailored article is more likely to engage and resonate with its audience.

4. Investigate the Research Methodology : If the article involves research or empirical data, delve into the methodology used to gather and analyze the information. Evaluate the soundness of the study design, sample size, and data collection methods. Understanding the research process adds depth to your critique.

5. Discuss the Implications and Application : Consider the broader implications of the article's findings or arguments. Discuss how the insights presented in the article could impact the field of study or have practical applications in real-world scenarios. Identifying the potential consequences of the article's content strengthens your critique's depth and relevance.

Wrapping Up

In a nutshell, article critique is an essential skill that helps us grow as critical thinkers and active participants in academia. Embrace the opportunity to analyze and offer constructive feedback, contributing to a brighter future of knowledge and understanding. Remember, each critique is a chance to engage with new ideas and expand our horizons. So, keep honing your critique skills and enjoy the journey of discovery in the world of academic exploration!

Tired of Ordinary Critiques?

Brace yourself for an extraordinary experience! Our critique geniuses are on standby, ready to unleash their extraordinary skills on your article!

What Steps Need to Be Taken in Writing an Article Critique?

What is the recommended length for an article critique.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

Related Articles

.webp)

- Open access

- Published: 21 May 2024

A modern way to teach and practice manual therapy

- Roger Kerry 1 ,

- Kenneth J. Young ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8837-7977 2 ,

- David W. Evans 3 ,

- Edward Lee 1 , 4 ,

- Vasileios Georgopoulos 1 , 5 ,

- Adam Meakins 6 ,

- Chris McCarthy 7 ,

- Chad Cook 8 ,

- Colette Ridehalgh 9 , 10 ,

- Steven Vogel 11 ,

- Amanda Banton 11 ,

- Cecilia Bergström 12 ,

- Anna Maria Mazzieri 13 ,

- Firas Mourad 14 , 15 &

- Nathan Hutting 16

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies volume 32 , Article number: 17 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

114 Altmetric

Metrics details

Musculoskeletal conditions are the leading contributor to global disability and health burden. Manual therapy (MT) interventions are commonly recommended in clinical guidelines and used in the management of musculoskeletal conditions. Traditional systems of manual therapy (TMT), including physiotherapy, osteopathy, chiropractic, and soft tissue therapy have been built on principles such as clinician-centred assessment , patho-anatomical reasoning, and technique specificity. These historical principles are not supported by current evidence. However, data from clinical trials support the clinical and cost effectiveness of manual therapy as an intervention for musculoskeletal conditions, when used as part of a package of care.

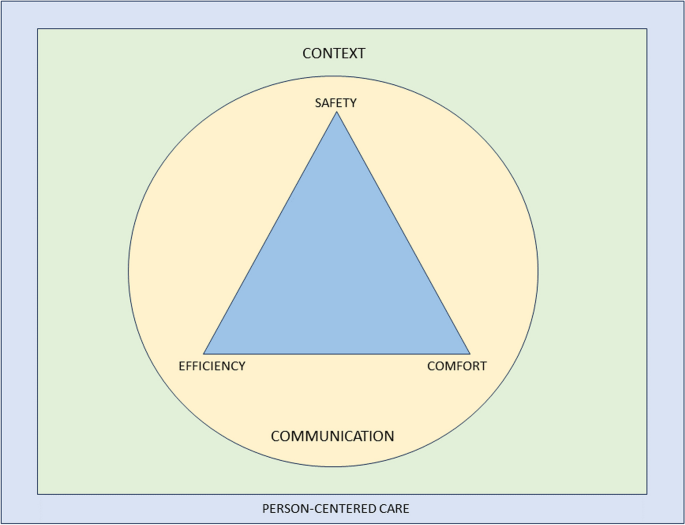

The purpose of this paper is to propose a modern evidence-guided framework for the teaching and practice of MT which avoids reference to and reliance on the outdated principles of TMT. This framework is based on three fundamental humanistic dimensions common in all aspects of healthcare: safety , comfort , and efficiency . These practical elements are contextualised by positive communication , a collaborative context , and person-centred care . The framework facilitates best-practice, reasoning, and communication and is exemplified here with two case studies.

A literature review stimulated by a new method of teaching manual therapy, reflecting contemporary evidence, being trialled at a United Kingdom education institute. A group of experienced, internationally-based academics, clinicians, and researchers from across the spectrum of manual therapy was convened. Perspectives were elicited through reviews of contemporary literature and discussions in an iterative process. Public presentations were made to multidisciplinary groups and feedback was incorporated. Consensus was achieved through repeated discussion of relevant elements.

Conclusions

Manual therapy interventions should include both passive and active, person-empowering interventions such as exercise, education, and lifestyle adaptations. These should be delivered in a contextualised healing environment with a well-developed person-practitioner therapeutic alliance. Teaching manual therapy should follow this model.

Musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions are leading contributors to the burden of global disability and healthcare [ 1 ]. Amongst other interventions, manual therapy (MT) has been recommended for the management of people with MSK conditions in multiple clinical guidelines, for example [ 2 , 3 ].

MT has been described as the deliberate application of externally generated force upon body tissue, typically via the hands, with therapeutic intent [ 4 ]. It includes touch-based interventions such as thrust manipulation, joint mobilisation, soft-tissue mobilisation, and neurodynamic movements [ 5 ]. For people with MSK conditions, this therapeutic intent is usually to reduce pain and improve movement, thus facilitating a return to function and improved quality of life [ 6 ]. Patient perceptions of MT are, however, vague and sit among wider expectations of treatment including education, self-efficacy and the role of exercise, and prognosis [ 7 ].

Although the teaching and practice of MT has invariably changed over time, its foundations arguably remain unaltered and set in biomedical and outdated principles. This paper sets out to review contemporary literature and propose a revised model to inform the teaching and practice of MT.

The aim of this paper is to stimulate debate about the future teaching and practice of manual therapy through the proposal of an evidence-informed re-conceptualised model of manual therapy. The new model dismisses traditional elements of manual therapy which are not supported by research evidence. In place, the model offers a structure based on common humanistic principles of healthcare.

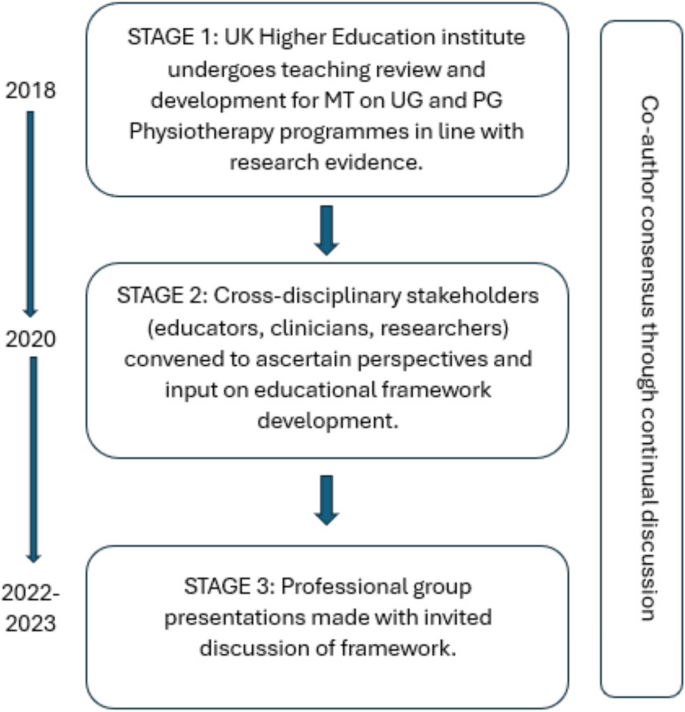

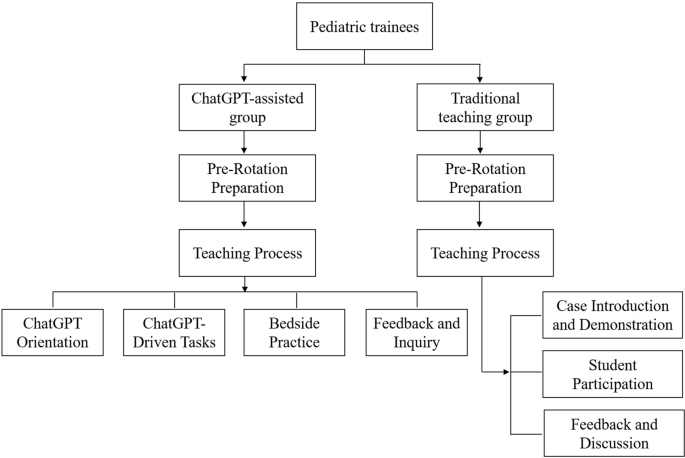

Consenus methodology

We present the literature synthesis and proposed framework as a consensus document to motivate further professional discussion developed through a simple three-stage iterative process over a 5-year period. The consensus methodology was classed as educational development which did not require ethical approval. Stage 1: a change of teaching practice was adopted by some co-authors (VG, RK, EL) on undergraduate and postgraduate Physiotherapy programmes at a UK University in 2018. This was a result of standard institutional teaching practice development which includes consideration of evidence-informed teaching. Stage 2: Input from a broader spectrum of stakeholders was sought, so a group of experienced, internationally-based educators, clinicians, and researchers from across the spectrum of manual therapy was convened. Perspectives were elicited through discussions in an iterative process. Stage 3: Presentations were made by some of the co-authors (VG, RK, SV, KY) to multidisciplinary groups (UK, Europe, North America) and feedback via questions and discussions was incorporated into further co-author discussions on the development of the framework. Consensus was achieved through repeated discussion of relevant elements. Figure 1 summarises the consensus methodology.

Summary and timeline of iterative consensus process for development of framework (MT: Manual Therapy; UG: Undergraduate; PG: Postgraduate)

Clinical & cost effectiveness of manual therapy

Manual therapy has been suggested to be a valuable part of a multimodal approach to managing MSK pain and disability, for example [ 8 ]. The majority of recent systematic reviews of clinical trials report a beneficial effect of MT for a range of MSK conditions, with at least similar effect sizes to other recommended approaches, for example [ 9 ]. Some systematic reviews report inconclusive findings, for example [ 10 ], and a minority report effects that were no better than comparison or sham treatments, for example [ 11 ].

Potential benefits must always be weighed against potential harms, of course. Mild to moderate adverse events from MT (e.g. mild muscle soreness) are common and generally considered acceptable [ 12 ], whilst serious adverse events are very rare and their risk may be mitigated by good practice [ 13 ]. MT has been reported by people with MSK disorders as a preferential and effective treatment with accepted levels of post-treatment soreness [ 14 ].

MT is considered cost-effective [ 15 ] and the addition of MT to exercise packages has been shown to increase clinical and cost-effectiveness compared to exercise alone in several MSK conditions [ 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. Further, manual therapy has been shown to be less costly and more beneficial than evidence-based advice to stay active [ 24 ].

In summary, MT is considered a useful evidence-based addition to care packages for people experiencing pain and disability associated with MSK conditions. As such, MT continues to be included in national and international clinical guidelines for a range of MSK conditions as part of multimodal care.

Principles of traditional manual therapy (TMT)