General Studies

All Programmes

Study Material

Quest for UPSC CSE Panels

Sub-Categories:

GS-I: Ancient History

Prelims : History of India

Mains : Indian culture- Salient aspects of Art Forms, Literature and Architecture from ancient to modern times

In the sixth century BC, Jainism emerged as a result of widespread opposition to the formalized ritualism and hierarchical structure of the Vedic religion. Jainism is one of the religions whose origin can be traced back to the twenty four teachers (tirthankaras - ones who establishes a path or ford), through whom their faith is believed to have been handed down.

Jainism is a sramanic religion. Sramana' is a Sanskrit word that denotes an ascetic or monk. The practice of virtues such as non-violence, renunciation, celibacy, self-control, etc., as well as asceticism, mysticism, meditation, contemplation, silence, and solitude, among others, are distinguishing features of this tradition.

Factors led to the Rise of Jainism in India

The primary cause of the rise of religion was the religious unrest in India in the 6th century BC. Other major factors include:

- For example, the sacrificial ceremonies were too expensive, and the superstitious beliefs and mantras confused people.

- Domination of Brahmans: The Brahmans stated themselves as upper Varna with the highest status in society and demanded several privileges. Thus, these systems naturally divided society and generated tensions.

- Opposition from Kshatriyas and Vaishyas: They reacted strongly against the ritualistic domination of the Brahmans.

- The equality of Jainism: Attracted the masses, which gave relief from the discriminations of the Varna system.

- Use of Simple Language : Mahavira’s religious message was in simple language. The masses were drawn to it because it was in the language they spoke and understood better. Acceptance by the masses soon led to its spread.

- Nonviolence and other practical moralities that Jainism advocated attracted people to it.

- Its edge over the Vedic religion was a comparatively easier way to liberation, thereby gaining wider adherence throughout India.

Historical Background of Jainism

According to Jaina traditions, twenty-four Tirthankaras were responsible for the origin and development of Jaina religion and philosophy. Of these, the first twenty-two are of doubtful historicity. In the case of the last two, Parsvanatha and Mahavira, Buddhist works confirm their historicity.

- Adinath/Rishabhdev: The first Tirthankara (supreme preacher) and establisher of the Ikshvaku dynasty.

- Ajita: The second Tirthankara

- Neminatha: the twenty-second Tirthankara

- Parsvanatha believed in the eternity of ‘matter’ .

- The followers of Parsvanatha wore white garments .

- Thus, it is clear that even before Mahavira, some kind of Jaina faith existed.

- Mahavira: The twenty-fourth Tirthankara was Vardhamana Mahavira.

Mahavira and his life

The 24th Tirthankara was Vardhamana Mahavira.

- Birth: Born in Kundagrama (Basukunda), a suburb of Vaishali (Bihar), in 540 BC.

- Parents: Father Siddhartha (head of the Jnatrikas, a Kshatriya clan) and mother, Trishala, a Lichchavi princess.

- Spouse: Yashoda

- What made Vardhaman Mahavira take up asceticism?

- At the age of thirty, Vardhamana left his home and became an ascetic.

- For twelve years, he lived the life of an ascetic following severe austerities.

- In the 13th year of his asceticism, at the age of 42, he attained the ‘Supreme Knowledge’ (Kaivalya).

- Titles: He was later known as ‘Mahavira’ (the supreme hero) or ‘Jina’ (the conqueror). He was also hailed as ‘Nirgrantha’.

- Preachings: For the next thirty years, he moved from place to place and preached his doctrines in Kosala, Magadha , and further east.

- Patronage: He often visited the courts of Bimbisara and Ajatasatru.

- Death: He died at Pawa (near Rajagriha) in Patna district at the age of 72 (468 BC).

Jain Councils

Teachings of mahavira.

The ultimate objective of Mahavira’s teachings is how one can attain total freedom from the cycle of birth, life, pain, misery, and death and achieve the permanent blissful state of one's self. This is also known as liberation , Nirvana , absolute freedom , or Moksha .

Pancha Mahavratas in Jainism

Mahavira accepted most of the religious doctrines laid down by Parsvanatha. However, he made some alterations and additions to them. The five doctrines of Jainism (five vows), known as Panchamahavratas, are for the monks.

- Anuvratas: A code of conduct was prescribed for both householders and monks. To avoid evil karma, a householder had to observe the five vows (in their limited nature).

- Jainism believed that the monastic life was essential to attaining salvation, and a householder could not attain it.

- A monk had to observe certain strict rules and abandon worldly possessions.

- According to him, the soul is in a state of bondage created by desire accumulated through previous births.

- The liberated soul then becomes ‘the pure soul ." He thought that all objects, animate and inanimate, had a soul.

- He believed that they felt pain or the influence of injury.

- He advocated a life of severe asceticism and extreme penance to attain ‘nirvana’ or the highest spiritual state.

- The idea of God: He believed that the world was not created by any supreme creator. The world functions according to an eternal law of decay and development.

- View on Vedas: He rejected the authority of the Vedas and objected to Vedic rituals and the supremacy of the Brahmanas.

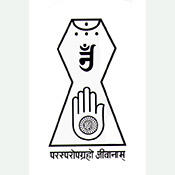

8 Auspicious Symbols of Jainism

Jainism has several important symbols that hold significant meaning for its followers. Here are some of the key symbols of Jainism:

- Swastika - It signifies the peace and well-being of humans.

- Nandavarta - It is a large swastika with nine endpoints.

- Bhadrasana - A throne is said to be sanctified by the Jaina’s feet.

- Shrivatsa - A mark manifests on the chest of Tirthankara's image and signifies his pure soul.

- Darpana - The mirror which reflects the inner self.

- Minayugala - A couple fish which signifies the conquest over sexual urges.

- Vardhamanaka - A shallow dish is used as a lamp, which shows the increase in wealth, due, and merit.

- Kalasha - A pot filled with pure water.

Five types of knowledge in Jainism

According to Jainism, knowledge is the quality of the soul. Understanding and acquiring knowledge are attained through pramana (instruments of knowledge) and naya (points of view).

- Mati Jnana: Perception through the activity of sense organs, including the mind.

- Sruta Jnana : Knowledge revealed by the scriptures.

- Avadhi Jnana : Clairvoyant perception.

- Manahparyaya Jnana : Telepathic knowledge

- Kevala Jnana : Temporal knowledge or omniscience.

Mahavira’s teachings were orally transmitted to people. His disciples, Ganadharas, wrote them down in the text form of fourteen ‘Purvas’ and twelve Angas.

Among the 12 Angas, the Acharanga sutta and Bhagavati sutta are the most important. While the former deals with the code of conduct which a Jain monk must follow, the latter expounds the Jaina doctrines comprehensively.

Doctrine of Syadvada and Anekantavada

- According to this concept, identity and difference must exist in reality.

- Anekantavada has also been interpreted to mean- non-absolutism, intellectual ahimsa, religious pluralism, and rejection of fanaticism.

Sects of Jainism

The Jain order has been divided into two major sects: Svetambara and Digambara.

- The leader of the group that stayed back at Magadha wasof Sthulbhadra.

- During the 12 years of famine, the group in South India stuck to the strict practices, while the group in Magadha adopted a more lax attitude and started wearing white clothes.

- They were called the Terapanthis among the Svetambaras and the Samaiyas among the Digambaras. (This sect came into existence about the sixth century CE).

Sub-sects of Jainism under Digambaras and Svetambaras

Spread of jainism to other parts of india.

Jainism spread to different parts of India during Mahavira's lifetime and after his death. Several factors are responsible for its spread.

- His simple way of life, penance and austerity attracted people towards him.

- Mahavira had eleven disciples known as Ganadharas or heads of schools.

- Arya Sudharma was the only Ganadhara who survived after the death of Mahavira . Mahavira became the first ‘Thera’ (chief preceptor) .

- Role of Jain Monks : Jain monks spread Jainism by visiting several places and holding scholarly discussions exhibiting their personal examples of simplicity, which could significantly influence the people.

- Royal Patronage: The followers of Mahavira slowly spread over the whole country. In many regions, royal patronage was bestowed on Jainism.

- According to Jaina tradition, Udayin , the successor of Ajatasatru, was a devoted Jaina.

- Chandragupta Maurya was a follower of Jainism, and he migrated with Bhadrabahu to the south and spread Jainism.

- During the early centuries of the Christian Era, Mathura and Ujjain became great centres of Jainism.

- Two Theras administered the Jaina order in the days of the late Nanda King: Sambhutavijaya and Bhadrabahu. The sixth Thera was Bhadrabahu, a contemporary of Maurya King Chandragupta Maurya.

Relevance of Jain Ideology in today's World

The doctrines of Jainism with respect to the contemporary world situation are found to be very much relevant. With these doctrines of Jainism, we can bring back the peace and harmony in the society and the world.

- Anektavada highlights the spirit of intellectual and social tolerance in the world.

- Non-violence: The principle of non-violence gained prominence in today's nuclear-weapon world to attain long-lasting peace in society.

- The principle of Aparigraha can help to control consumerist habits as there is a great increase in greed and possessive tendencies.

- The doctrine of Triratna is relevant to present-time situations, which can liberate the souls of women along with men from the subjugation to liberty and freedom.

PYQs on Jainism

Question 1: With reference to Indian history, consider the following texts: (UPSC Prelims 2022)

- Nettipakarana

- Parishishtaparvan

- Avadanashataka

- Trishashtilakshana Mahapurana

Which of the above are Jaina texts?

- 2 and 4 only

Answer: (b)

Question 2: With reference to the religious practices in India, the "Sthanakvasi" sect belongs to (UPSC Prelims 2018)

- Vaishnavism

Question 3: With reference to the religious history of India, consider the following statements (UPSC Prelims 2017)

- Sautrantika and Sammitiya were the sects of Jainism.

- Sarvastivadin held that the constituents of phenomena were not wholly momentary but existed forever in a latent form.

Which of the statements given above is/are correct?

- Both 1 and 2

- Neither 1 nor 2

Question 4: Which of the following statements is/are applicable to Jain doctrine? (UPSC Prelims 2013)

- The surest way of annihilating Karma is to practice penance.

- Every object, even the smallest particle, has a soul.

- Karma is the bane of the soul and must be ended.

Select the correct answer using the codes given below.

- 2 and 3 only

- 1 and 3 only

Answer: (d)

FAQs on Jainism

What is jainism.

Jainism is an ancient Indian religion that teaches that the path to liberation and bliss is through harmlessness and renunciation.

What are the five vows of Jainism?

The five doctrines of Jainism (five vows), known as Panchamahavratas, are Ahimsa, Satya, Asteya, Brahmacharya, and Aparigraha.

What are the three Ratnas of Jainism?

In Jainism, the three jewels (also referred to as ratnatraya) are understood as samyag-darsana (“right faith”), samyag-jnana (“right knowledge”), and samyak-charitra (“right conduct”).

What is the ideology of Jainism?

According to Jainism, the path to enlightenment is through nonviolence and reducing harm to living things (including plants and animals). Jains, like Hindus and Buddhists, believe in reincarnation. Karma determines the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth.

Who are the Tirthankaras?

Tirthankaras are called Arihants/Arahants, individuals who have successfully conquered inner passions. A Tirthankara is not an incarnation of the god. He is an ordinary soul born as a human and attains the state of a Tirthankara due to intense practices of penance, calmness and meditation.

What is Aryika in Jainism?

Aryika is a female mendicant in Jainism, also known as Sadhvi. A Sadhvi enters the mendicant order by making five vows, i.e., Ahimsa, Satya, Asteya, Brahmacharya and Aparigraha.

© 2024 Vajiram & Ravi. All rights reserved

ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

Jainism is one of the three ancient religions of India, with a value system that puts nonviolence above all else.

Anthropology, Sociology, Religion, Social Studies, Ancient Civilizations, World History, Storytelling

A hand carved statue of Mahavira made from marble, inside a Jain temple in Jaisalmer Fort, Rajasthan, India. Also known as Vardhamana, Mahavira was a tirthankara or a teacher of the dharma.

Photograph by Craig Lovell

Jainism is one of the three most ancient religions of India, with roots that go back to at least the mid-first century B.C.E. Today, it is still an integral part of Indian culture . Jainism teaches that the path to enlightenment is through nonviolence and reducing harm to living things (including plants and animals) as much as possible.

Like Hindus and Buddhists, Jains believe in reincarnation . This cycle of birth, death, and rebirth is determined by one’s karma . Jains believe bad karma is caused by harming living things. To avoid bad karma , Jains must practice ahimsa, a strict code of nonviolence . Jains believe plants, animals, and even some nonliving things (like air and water) have souls, just as humans do. The principle of nonviolence includes doing no harm to humans, plants, animals, and nature. For that reason, Jains are strict vegetarians —so strict, in fact, that eating root vegetables is not allowed because removing the root would kill the plant. However, Jains can eat vegetables that grow above the ground, because they can be picked while leaving the rest of the plant intact. In complete dedication to nonviolence , the highest-ranked Jain monks and nuns avoid swatting at mosquitoes or sweeping a path on the floor so they do not step on an ant. In addition to nonviolence , Jainism has four additional vows that guide believers: always speak the truth, do not steal, show sexual restraint (with celibacy as an ideal), and do not become attached to worldly things.

While it shares many beliefs and values with Hinduism and Buddhism, Jainism has its own spiritual leaders and teachers. Jains honor 24 Jinas, or Tirthankaras: spiritual leaders who achieved enlightenment and have been liberated from the cycle of rebirth. One of the most influential Jinas was Mahavira, born Vardhamana, who is considered the 24th, and final, Jina. He was born into the kshatriya or warrior class, traditionally dated in 599 B.C.E., though many scholars believe he was born later. When he was 30 years old, he renounced his worldly possessions to live the life of an ascetic (one who practices self-denial of worldly things). After over 12 years of intense fasting and meditation, Vardhamana achieved enlightenment and became Mahavira (meaning “Great Hero”). According to tradition, he established a large community of Jain followers: 14,000 monks and 36,000 nuns at the time of his death.

Today, most followers of Jainism live in India, with estimates of upwards of four million followers. Jainism’s teachings have influenced many all over the world. Though born a Hindu, Mahatma Gandhi admired the Jains' commitment to complete nonviolence, and he incorporated that belief into his movement for Indian independence.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Manager

Program specialists, specialist, content production, last updated.

October 31, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.1: Jainism- Introduction

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 226229

- Lumen Learning

For those who wish to listen to information on the world’s religions here is a listing of PODCASTS on RELIGIONS by Cynthia Eller.

If you have iTunes on your computer just click and you will be led to the listings. phobos.apple.com/WebObjects/MZStore.woa/wa/viewPodcast?id=117762189&s=143441

Here is a link to the site for the textbook REVEALING WORLD RELIGIONS related to which these podcasts were made. thinkingstrings.com/Product/WR/index.html

************************************************************ Jainism was born in India about the same period as Buddhism. It was established by Mahavira (c. 599 – 527 BC) in about 500 B. C. He was born near Patna in what is now Bihar state. Mahavira like Buddha belonged to the warrior caste. Mahavira was called ‘Jina’ meaning the big winner and from this name was derived the name of the religion.

In many senses Jainism is similar to Buddhism. Both developed as a dissension to the Brahmanic philosophy that was dominant during that period in north-east India. Both share a belief in reincarnation which eventually leads to liberation. Jainism is different to Buddhism in its ascetic beliefs. Both these religions emphasize non-violence, but non-violence is the main core in Jainism. Mahavira just like Buddha isn’t the first prophet of his religion. In Jainism like Buddhism there is a belief in reincarnation which eventually leads to liberation. Neither of these religions their religious philosophy around worship. But Jainism is different than Buddhism in its ascetic beliefs. Both these religions emphasis on non-violence, but in Jainism non-violence is its main core.

Jains believe that every thing has life and this also includes stones, sand, trees and every other thing. The fact that trees breath came to be known to the science world only from the 20th century. Mahavira who believed that every thing has life and also believed in non-violence practically didn’t eat anything causing his self- starvation to death. Mahavira was also extremely ascetic and walked around completely naked because of his renouncement of life. After years of hardship and meditation he attained enlightenment; thereafter he preached Jainism for about 30 years and died at Pava (also in Bihar) in 527 BC.

Mahavira’s religion followers are less extreme than him in diets. They are vegetarians. But the religious Jains will do everything possible to prevent hurting any being. They won’t walk in fields where there are insects to prevent the possibility of stepping on them. They also cover their mouth to prevent the possibility of swallowing small invisible microbes. They mostly do not work in professions where there is a possibility of killing any living being like in agriculture instead professions like banking and business. But it is not clear what came first, businessmen who adopted Jain philosophy because it was easy for them to follow or Jainish philosophy which convinced the Jains to adopt non violent professions.

There are two Jain philosophies. Shvetember and Digamber. Digamber monks like Mahavira don’t wear any clothes, but normally they don’t walk like that outside their temples. The Digambers include among them only men. The Shvetembers monks wear white clothes and they include women.

©Aharon Daniel Israel 1999-2000 allowed to use

Contributors and Attributions

- Authored by : Philip A. Pecorino. Located at : http://www.qcc.cuny.edu/socialsciences/ppecorino/phil_of_religion_text/CHAPTER_2_RELIGIONS/Jainism.htm . License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

- Introduction to Jainism

- Jainism in America

- The Jain Experience

- Issues for Jains in America

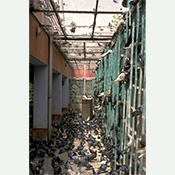

A Hospital for Birds

... Read more about A Hospital for Birds

Tirthankaras: “Ford-Makers”

Jiva: The Souls of All Beings

... Read more about Jiva: The Souls of All Beings

Karma: Clouding of the Soul

... Read more about Karma: Clouding of the Soul

Ahimsa: Reverence for Life

An Ethic for Living

... Read more about An Ethic for Living

Anekantavada: The Relativity of Views

Jain Renouncers: Sky Clad and White Clad

... Read more about Jain Renouncers: Sky Clad and White Clad

Mendicants and Laity

Temples and Images

... Read more about Temples and Images

The Jain Symbol

Jainism Outside India

... Read more about Jainism Outside India

V.R. Gandhi at the World’s Parliament of Religions

... Read more about V.R. Gandhi at the World’s Parliament of Religions

Jain Immigration

... Read more about Jain Immigration

Building Temples and Networks

... Read more about Building Temples and Networks

Jain Teachers in the New World

Namaskara Mantra: Beginning with Praise

... Read more about Namaskara Mantra: Beginning with Praise

The Temple and Image

... Read more about The Temple and Image

Celebrating Mahavira: Mahavira Jayanti and Divali

... Read more about Celebrating Mahavira: Mahavira Jayanti and Divali

Paryushana and the Festival of Forgiveness

... Read more about Paryushana and the Festival of Forgiveness

Ahimsa in Daily Life

... Read more about Ahimsa in Daily Life

“Gateway to Luck”

... Read more about “Gateway to Luck”

Unity: The American Context

Authority Without Monks

... Read more about Authority Without Monks

Love and Marriage

... Read more about Love and Marriage

Svadhyaya: Jain Education for Adults in North America

Pathshala: The Next Generation

... Read more about Pathshala: The Next Generation

Image Gallery

Recent News

How lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and fortune, is depicted in jainism and buddhism, jainism, american style, bandi chhor divas, celebrated at diwali, has a history and values of its own, young jains of america.

- Das Lakshan

- Jain meditation

- Kumar, Sushil

Jainism Timeline

6323dddaff85d27ed6f05d9690e4cb70, jainism in the world (text), c. 850 bce parshvanath, twenty-third tirthankara.

In Jainism, a Tirthankara is a spiritual teacher who has overcome the cycle of death and rebirth (samsara). The first Tirthankara is said to have founded Jainism millions of years ago. Historians date the twenty-third Tirthankara, Parshvanath, to the eighth or ninth century BCE.

599 – 527 BCE Mahavira

The twenty-fourth Tirthankara, Mahavira, was born in the 6th century BCE near Patna in what is now the state of Bihar in India. He is said to have been a kshatriya, a prince or warrior, and to have renounced the world to seek self-realization. He attained kaivalya, luminous knowledge, at age 42 and taught for thirty years until his death.

360 BCE Beginning of Digambar/Shvetambar Split

It is said that at a time of famine in the 4th century BCE, part of the Jain community migrated south. When they returned, they found the monks of the north had compiled a version of the scripture with which they did not wholly agree and had taken to wearing simple white clothing rather than maintaining the “sky-clad” traditions. Thus the Shvetambar (“White-clad”) and Digambar (“Sky-clad”) schism constitutes the major sectarian split in the Jain tradition.

400s CE Formation of the Shvetambar Siddhanta

By the fifth century CE, Shvetambar Jains had compiled a canon, commonly called the Siddhanta. The canon includes 45 texts subsumed under six categories, the oldest and most venerated of which are the 12 angas, including the Acharanga.

400s CE Development of Jain Lay Community

By the early centuries of the common era, the Jain tradition had small communities throughout the Indian peninsula. Shvetambars were concentrated in north and west India, the Digambars were principally in south and central India. Although the monastic order remained the core of both Jain communities, in each case a growing number of lay practitioners associated themselves with the tradition. Beginning in the fifth century, Jain literature increasingly concerned itself with regulating non-monastic life, including proper etiquette toward monks and nuns, temple worship, and life-cycle rites.

1000s CE Digambar Community Concentrates in Maharashtra

The Digambar Jain community, which had previously enjoyed royal patronage in south and east India, fell into disfavor as Hindu theism gained popularity in the 11th century CE. Digambars migrated north and westward, settling in Karnataka and Maharashtra, where their descendants have continued to make their homes.

1100s CE Shvetambar Community Concentrates in Gujarat

The tide of Hindu theism that precipitated the emigration of Digambar Jains from southern India swept over northern India as well in the 1100s CE. This shift, coupled with the rise of Islam, resulted in a contraction of the Shvetambar community, which has been concentrated in Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh ever since.

1400s CE Sthanakvasi Reform Movement Develops

Beginning around the 10th century CE, there developed a class of monks who lived full-time in temples and exerted increasing control over temple resources. Charges of corruption and spiritual degeneration occurred with increasing frequency, culminating in 1451, when a Shvetambar layman named Lonka Saha launched the Sthanakvasi reform movement. Unlike most Jain groups, Sthanakvasis, or “dwellers in halls” (as opposed to temples), object to the veneration of images, claiming that such activity too easily degenerates into idol-worship. Monks of this movement are recognized by their practice of donning a cloth or mask over the mouth and nose to avoid inadvertently inhaling and thus harming minute life forms.

1500s CE Taranapantha Reform Movement Emerges

Apparently influenced by the Sthanakvasi movement, a small group of Digambars under the leadership of a man by the name of Taranasvami emerged in the 16th century CE. This group became known as the Taranapantha Reform Movement, and like the Sthanakvasis, also banned the worship of images.

1700s CE Birth of Terapantha Reform Movement

Followers of Jainism agree that a person should eschew any action that would harm a living being. But in the eighteenth century CE, a Sthanakvasi monk named Bhikhanji also asserted that a person should avoid any action that would directly affect another sentient being, including saving its life. Bhikhanji believed that to give aid to another not only indicates that one has failed to practice total renunciation, but makes one responsible for any harm that that being may cause in the future. It is said that Bhikhanji’s reform movement is called Terapantha, “the path of the thirteen,” because he could only gather twelve disciples to follow his radical ideas. Today, the Terapantha movement continues as a small but vocal minority of the Shvetambar tradition.

1869 – 1948 CE Friendship of Mohandas Gandhi and Raychandbhai Mehta

Mohandas Gandhi was arguably the greatest champion of nonviolence in the 20th century. Although a Hindu, his appreciation for the profound spiritual significance of ahimsa derived principally from the conversations and correspondence he had with Raychandbhai Mehta, a prominent Jain layman. According to Gandhi, the three men who most deeply influenced his thought were Tolstoy, Ruskin, and Raychandbhai.

1970 CE Shri Chitrabhanu Travels to Geneva

In 1970, Shri Chitrabhanu became the first Jain monk to break the injunction against traveling by airplane when he flew to Geneva to attend the second Spiritual Summit Conference. He arrived in the United States one year later to establish the Jain International Meditation Center in New York and to found and inspire many other Jain centers across the U.S. and the world.

1990 CE “Jain Declaration on Nature”

The “Jain Declaration on Nature'' was a statement on the Jain philosophy of non-violence and its relevance to the ecological crisis. The declaration was presented in 1990 by an international group of Jain leaders to H.R.H. Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

2010 CE Jain Temple Opened in Belgium

In 2010, the largest Jain temple outside of India opened its doors in a suburb of Antwerp to serve the thousands of Jains in the area, many of whom are involved in the diamond trade. The community’s spiritual leader, Ramesh Mehta, was also a member of the Belgian Council of Religious Leaders, illustrating the strengthening relationship between the Jain community and other European faith groups.

Jainism in America (text)

1893 ce v.r. gandhi at world’s parliament of religions.

Virchand R. Gandhi (1864-1901), a Bombay lawyer, was the sole Jain at the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago. Following the Parliament, V.R. Gandhi stayed in the U.S. for two years to give some 535 lectures on such topics as Jainism, Yoga, Hindu culture, and Indian philosophy.

1893 CE Shri Lalan Comes to the U.S.

A Jain scholar named Shri Lalan came to the U.S. in 1893 and stayed for over four years. Inspired by the Jain teachings of Shri Lalan, an American woman, Mrs. Howard, became a disciple and a vegetarian.

1896-97 CE V.R. Gandhi Helps Organize Famine Relief

On a second trip to the U.S. and England in 1896-1897, V.R. Gandhi joined with Charles C. Bonney, who had been President of the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions, to organize a Famine Relief Committee for India. This committee sent about $10,000 and a steamer full of corn to India.

1904-05 CE Jain Temple Replica at St. Louis World’s Fair

A replica of the Jain temple at Palitana in Gujarat was sent by the British government of India to the St. Louis World’s Fair Exposition in 1904. After being in storage for several decades, the temple replica was purchased by the Summa Corporation, which placed it in their Castaways Hotel in Las Vegas, Nevada. In 1995, the hotel donated the temple replica to the Jain Center of Southern California.

1919 CE Life and Stories of Parsvanatha Published

In 1919, Maurice Bloomfield, Professor of Sanskrit at Johns Hopkins University, published Life and Stories of the Jaina Savior Parsvanatha, one of the first Jain texts published in the U.S.

1933 CE Jain at World Fellowship of Faiths in Chicago

Champatrai Jain, a lawyer from India, presented a talk on “Ahimsa as the Key to World Peace” at the 1933 World Fellowship of Faiths meeting in Chicago.

1959 CE Formation of Jain Groups in the U.S.

In 1959, Jains in New York City organized an informal society. A second group was formed in Michigan soon after.

1966 CE First American Jain Center Established

The first Jain Center in the U.S. was established in New York City in 1966 by a small group of Jain immigrants. Three years later, another Jain center was established in Chicago.

1971 CE Gurudev Chitrabhanu First Visits U.S.

Gurudev Chitrabhanu visited the U.S. in 1971 to spread the message of Jainism and non-violence. His trip made him the first Jain monk to part with the monastic tradition of travel restriction. Later, having left the traditional monkhood, he returned to the United States and became one of the most important religious leaders of the American Jain community. Chitrabhanu established the Jain Meditation International Center in New York City in 1974.

1973 CE Jain Center of Greater Boston Established

Since its founding in 1973, the Jain Center of Greater Boston has made a significant contribution to Jainism in the U.S., promoting Jain philosophy and community. In 1979, the Center began publishing the Jain Study Circular, which has developed nationwide circulation. That same year, the Center’s “Directory of Jains in North America” first appeared, and today is regularly updated. In 1981, the Center became one of the first Jain Centers in North America to have its own temple.

1975 CE Acharya Sushil Kumar First Visits U.S.

Sushil Kumar became a monk in the Shvetambar Sthanakvasi sect of Jainism at the age of 15. He first came to the U.S. in 1975, and was the first Jain monk to travel abroad regularly while remaining a monk — a controversial move. He traveled extensively throughout the world and was an active participant at world conferences on peace and interreligious cooperation. Acharya Sushil Kumar passed away in 1994, at the age of 68.

1975 CE Jain Society of Greater Detroit

The Jain Society of Greater Detroit began in 1975 with about 50 families, but grew to over 250 families by the early 1990s. The Society operates a Jain study class for 100 children, hosts a summer camp, sponsors visiting lectures, and celebrates the Jain festivals. It has designated Thanksgiving Day as Ahimsa Day, a day of non-violence. In 1991, construction began on a million-dollar temple in Farmington Hills, a Detroit suburb.

1980 CE Sushil Kumar Founds International Mahavir Jain Mission

The International Mahavir Jain Mission (IMJM) was founded in Cleveland, Ohio in 1980 by Acharya Sushil Kumar. The purposes of the IMJM include promoting understanding of Jain scriptures, teachings, and practices, and cultivating academic and cultural exchange among Jains. Until his death in 1994, Kumar was the chairperson of IMJM. The society headquarters later moved to Siddhachalam in New Jersey.

1981 CE April 26 Proclaimed as a Day of Ahimsa in Cleveland

In 1981, the mayor of Cleveland and the city’s Jain Society proclaimed April 26, 1981 as a Day of Ahimsa (non-violence) in Cleveland, Ohio.

1981 CE Federation of JAINA Organized

In 1980, the Jain Center of Southern California voted to host a conference that would bring together representatives of all the Jain centers in North America. The conference took place over Memorial Day weekend of the following year. During this three-day meeting, the Federation of Jain Associations in North America (JAINA) was created, and a constitution for the new organization was drafted. JAINA continues to hold national conventions every other year, having convened in New York City (1983); Detroit (1985); Chicago (1987 and 1995); Toronto (1989); Stanford, California (1991); and Pittsburgh (1993).

1983 CE Siddhachalam Established in New Jersey

Siddhachalam was founded in New Jersey in 1983. This rural ashram and temple complex, established by Acharya Sushil Kumar on 108 acres in the foothills of the Pocono Mountains, was created as the first Jain tirtha or pilgrimage place outside of India. The rural center is a residential community for Jain monks and nuns and a retreat center for laity.

1985 CE Jain Digest Begins Publication

Jain Digest, a quarterly publication of the Jain Associations in North America (JAINA), was launched in 1985. The digest contains news from Jain societies throughout the U.S. and Canada. Jain Digest today has readers around the world.

1986 CE First Public Exhibit of Jain Paintings

In 1986 the New York Public Library organized “The World of Jainism,” the first public exhibition of Jain paintings in the U.S. Paintings from the manuscript Kalpa Sutra and other scriptures from the 15th to 19th centuries were featured. The exhibition of Jain paintings was part of the library’s participation in the Festival of India, a two-year-long celebration of Indian culture in the U.S.

1986 CE Indo-American Jain Conference

The Indo-American Jain Conference of the World Jain Congress was convened at Siddhachalam on September 26-28, 1986. The theme of the conference was Jain unity. Twelve hundred participants came from India, Europe, the U.S., Canada, and Africa. The construction of temples, literature, and world peace were among the topics discussed at the conference.

1987 CE Jain Study Circle Established

The Jain Study Circle was established in 1987 to promote study and understanding of the Jain tradition. The Circle organized study groups and took over responsibility for publishing the Jain Study Circular, which had been instituted by the Jain Center of Boston.

1988 CE Jain Temple Opens in Los Angeles

Members of the Jain Center of Southern California initially held their meetings in various community spaces. But in 1988, the JCSC opened their first temple, Jain Bhavan, in Los Angeles.

1991 CE Images Installed at Siddhachalam

From August 2-11, 1991, several thousand Jains came to the hilly countryside near Blairstown, New Jersey, to witness the installation of images of the Tirthankaras in the newly completed temple at Siddhachalam, the first Jain ashram and tirtha in the U.S. The event, called a Pratishta Mahotsav, was overseen by the founder of Siddhachalam, Acharya Sushil Kumar.

1992 CE American Jains at UN Earth Summit

Sushil Kumar represented American Jains in several interreligious events held in conjunction with the U.N. Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992.

1992 CE First Chaturmas in California

In 1992, the Jain Center of Northern California organized a four-month stay of two Jain monks called Samans, from an order of monks and nuns created by Acharya Tulsi in India specially to be able to travel and teach abroad. During their visit, the two gave lectures in Gujarati, Hindi, and English and provided instruction in Preksha meditation.

1993 CE Dedication of the Jain Temple in Chicago

In 1993, the Jain Society of Metropolitan Chicago dedicated a new temple in Bartlett, Illinois, a western suburb of Chicago. The temple was the largest Jain temple in the U.S. and contains both Shvetambar and Digambar images.

1993 CE Jainism Online

The Jain Bulletin Board System was launched on the Internet in 1993 to provide online information about Jainism. Jain presence online only continued to expand during the following decades, connecting Jains around the world as well as providing a platform for American Jains to engage with one another and with the wider American community.

2001 CE 9/11 Attacks Cause Hateful Backlash

While perpetrators of post-9/11 hate crimes targeted Muslims, many individuals of South Asian and Arab descent were also victims. Along with many communities whose members fit a similar racial profile, Jains collaborated to clarify their religious and cultural traditions to an American audience.

2010 CE Growth and Expansion of Jain Communities

The Jain community of Boston, among others throughout the U.S., experienced so much growth in the early 2000s that a larger building was required for the Jain Center of Greater Boston (JCGB). In 2010, community members moved to a new site in Norwood, a former synagogue that now houses classrooms for Jain education, a large event space, and a remodeled temple. The growth and formalized establishment of Jains in the U.S. is visible in communities across the country, especially apparent in such national groups as JAINA and the many conferences, youth programs, scholarships, and events they oversee.

Selected Publications & Links

Seeling, Holly . “ Authority and Transmission in the 'American' Jain Tradition .” The Pluralism Project , 1991.

Jain, Neelu . “ From Religion to Ethnicity: The Identity of Immigrant and Second Generation Indian Jains in the United States .” National Identities 6, no. 3 (2004): 277.

Bose, Subhindra . “ Indians Barred from American Citizenship .” Modern Review (Calcutta) , 1923, 33 , 691-695.

Jain Quantum

E-jain digest, young jain professionals, explore jainism in greater boston.

Jains first came from India to America in the late 1960s, establishing the Jain Center of Greater Boston (JCGB) in 1973. From 1981 until 2010, members of the JCGB gathered in a former Swedish Lutheran church in Norwood. Since 2010, JCGB have gathered in their own, purpose-built derasar (temple) in Norwood. A second local organization, the Jain Sangh of New England (JSNE), formed in 2000.

A study of the philosophy of Jainism

by Deepa Baruah | 2017 | 46,858 words

Summary : Among the heterodox systems of Indian philosophy, Jainism is regarded as one of the oldest religions in India having its own metaphysics, philosophy and ethics. It has discussed all the important topics of Indian philosophy. The salient features of Jaina philosophy include its realistic classification of being and its theory of knowledge, with its famous doctrines of syādvāda, anekāntavāda and nayavāda.

Copyright: Creative Commons Licence Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Source 1: exoticindiaart.com Source 2: shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in

Contents of this online book ( + / - )

The full text of the A study of the philosophy of Jainism in English is available here and publically accesible (free to read online). Of course, I would always recommend buying the book so you get the latest edition. You can see all this book’s content by visiting the pages in the below index:

Article published on 28 January, 2019

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Jainism: A Philosophy Promoting Individualism, Relativity and Co-Existence

In this paper, attempts are made to explore how Jain philosophy promote acceptance of differences hence, peace and multiculturalism. Discussing the doctrines of Karma, Anekantavada, Syadavada and Nyasa, the paper unfolds how the Jain philosophy facilitates an acceptance of individualism and respect for other’s opinions and viewpoints, therefore forming the base for co-existence by implying equality among individuals.

Related Papers

Academia.edu

Dr. CHIRANJIB KUMAR CHOUDHARY (PhD)

The present world has been facing numerous problems such as global warming, climate change, and economic crisis due to human thrust for unlimited wants and in course of that globalization has posed many challenges. People have been looking eagerly for some major solution for all these problems. And that solutions must be nature oriented and ecofriendly and must follow non-violence. Jain philosophy fits in that format as it believes in truth(nature rule) and non-violence(compassion and humanity). Growing stress among human beings due to modern work environment and human conflicts could be solved and digested by meditation-mediation, fasting and social harmony(aparigraha-detachment from some worldly affairs for harmony). Problems are many but solution is only one that is practices of Jain philosophy. Slowly but surely Jainism could paved the way by its practical approach of justified vows. The present paper focuses on the various dimensions of Jain philosophy and its effective role in resolving various issues of globalized world. The paper is reflective in nature and tried to highlight on the important aspect of Jainism in context of modern world and its need to resolve the global challenges, issues and crisis.

Jeffery Long

Religion Compass

AbstractThe Jains have constituted a small but highly culturally significant minority community in the Indian subcontinent for thousands of years. Probably best known for the profound commitment to an ethos of ahimsa, or nonviolence in thought, word, and deed, it is in the areas of nonviolence and ascetic practice that the Jains have had their greatest impact on the Hindu majority. Key themes and topics of ongoing scholarly debate and discussion in relation to Jainism are the question of its origins, the relationship of Jainism to Hinduism, the roles of women—especially ascetics—in the tradition, Jainism and ecology, and finally, the distinctive Jain approach to religious pluralism contained in a set of teachings called the Jain doctrines of relativity—anekantavada, nayavada, and syadvada.

Pisit P. Maneewong

The aim of this research is to undertake a comparative survey of ethics between Jainism and Buddhism. There are three objectives of this paper: 1) to present a brief overview of Jainism, 2) to study the ethics in Jainism, and 3) to make a comparison between the ethics in Jainism and Buddhism. In India, religion is a way of life, a spiritual path and a path to liberation for all seekers. India has been the land of spirituality and philosophy, and it also was the birthplace of the numerous religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism. Among Indian religions, Jainism and Buddhism are most related to each other. Jainism and Buddhism are alike in many aspects, having common features, i.e. the origins, the teachings, the followers, and the aim of liberation. Both religions share so many similarities from the outside, yet they are slightly different upon deeper investigation into their detail and information of their teachings. In Jainism, there are twenty-four Tīrthaṅkaras or Jinas. The last Tīrthaṅkara, Mahāvīra was a contemporary spiritual leader living in the same period as Gautama Buddha, the founder of Buddhism. Buddhism differed from the Jainism by teaching an alternative, not practicing extreme asceticism like Jainism did. Both philosophies and teachings continue to share similar terminologies, concepts and ideas of important themes even though the meanings may differ a bit, for example regarding the Mokṣa and Nibbāna ideals, both religions practice to liberate themselves to attain that supreme bliss but their methodologies are different. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to provide a survey of Jain ethics and Buddhist ethics and do a comparative study of ethics between Jainism and Buddhism in overview.

Shubham Srivastava

The ontological view of Jains is concerned primarily with the life and existence rather than the creation of the universe and the conception of God. Jainism, however, cannot be regarded as agnosticism or metaphysical nihilism. It is to the credit of Jain thinkers that they constructed a philosophy and theory of reality out of the negative approach of those who were protesting against the dogmatism of the Vedas. Jainism does not deny reality. Jain philosophers adopted a middle course by propounding a theory that the world consisted of two eternal, uncreated, coexisting but independent categories of substances: The conscious (jiva) and the unconscious (ajiva). They developed the logic that the world is not altogether unknowable; only one should not be absolutely certain about one's assertions. Jain philosophers said that moral and religious values must be brought out of dogmatic slavery. Wisdom must be proved by reason which, in turn, depends on the experiences of self and of others. The human experience based on reason constitutes the data for the discovery of reality. CONCEPT OF GODHOOD: Professor Surendranath Dasgupta, the famous philosopher-historian, has described the concept of Godhood as follows: "The true God is not the God as the architect of the universe, nor the God who tides over our economic difficulties or panders to our vanity by fulfilling our wishes, but it is the God who emerges within and through our value-sense, pulling us up and through the emergent ideals and with whom I may feel myself to be united in the deepest bonds of love. The dominance of value in all its forms presupposes love, for it is the love for the ideal that leads us to forget our biological encumbrances. Love is to be distinguished from passion by the fact that while the latter is initiated biologically, the former is initiated from a devotedness to the ideal. When a consummating love of this description is generated, man is raised to Godhood and God to man." This corresponds to the Jain approach to Godhood. In Jainism, God is the supreme manifestation of human excellence.

While examining a knee-deep contrast and comparison of Jainism and Christianity, an attempt is made to underscore the likenesses amongst all religions assuming the same basic needs for all mankind. Specifically, and with regard to matters of living, the struggle to ascend (moksha) in Jainism is contrasted with Christianity's struggle to improve (sanctification), and the differing roles of each faith's approach to compassion briefly discussed. In matters of truth, whether truth is absolute and what that might mean for all humanity is contrasted between the faiths. The criticisms and modern movements of each faith are shown in their resemblances, along with the author's personal thoughts on the subject of religious faith and its future in America.

Marie-Hélène Gorisse

Abstract, contents and reviews of PDNRL no. 36

The De Nobili Research Library – Association for Indology and the Study of Religion , Himal Trikha

Narendra Bhandari

A Sunday lecture for the Vedanta Society of New York exploring similarities and differences between Jain philosophy and Vedānta, and emphasizing the pluralism of the Jain anekānta doctrine and the approach of Sri Ramakrishna.

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Email Signup

Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology

Overview Essay

Jainism and Ecology

Christopher Key Chapple, Loyola Marymount University

Abstract: Jainism posits the vibrant existence of a living universe. Jains advocate the protection of life, from its most advanced forms down to the microbes and the elements. In addition to exploring the history and philosophy of Jainism and its implications for an ecological worldview, leading voices from the Jain community and the recent “Jain Declaration on the Climate Crisis” will be surveyed.

The Universe Lives

The Jain premise that individual life forms pervade the earth down to the elemental level, paired with the requirement that all harm to life be minimized, predisposes Jainism to a friendliness toward life that lends to what in modern times is referred to as environmental ethics. Because all environments are suffused with life and because life must be honored, Jainism implicitly affirms the basic ideas of ecological ethics and, although a bit more complex, of bioethics. Actions taken by Jain persons, in order to recognize and abide by the teachings of ahiṃsā , must take into consideration the desire on the part of any life form to flourish. This sentiment is expressed in the oldest surviving Jain text as follows:

All breathing, existing, living, sentient beings should not be slain, nor treated with violence, nor abused, nor tormented, nor driven away. This is the pure, unchangeable, eternal law. [1]

Harm to any life form causes the karma that obstructs one’s energy and consciousness and happiness to densify. Such actions must be avoided.

Since the rise of environmental awareness and concern after the 1984 Union Carbide industrial accident in Bhopal that took thousands of lives, several organizations have taken up the task of ecological advocacy India, most notably the Centre for Science and Environment in New Delhi and the Centre for Environment Education in Ahmedabad. Neither organization focuses particularly on faith-based approaches to environmental advocacy. Most work undertaken by Jains on behalf of environmental issues has been championed by individuals, several of whom will be discussed in this article.

As noted above, environmental or ecological concerns did not enter the modern Indian lexicon until the advent of local disasters that prompted a reconsideration of the prevailing Nehruvian drive toward India’s industrialization following independence from British colonial rule in 1947. Though some concerns had been expressed by Gandhi and others regarding pollution of local water sources, this was not seen to be part of the broad systemic problems that have been revealed since the Bhopal disaster. Since that time, numerous campaigns have been aimed at cleaning India’s rivers, improving air quality, and ensuring the integrity and vitality of the soil. Leaders within these movements include M. C. Mehta who campaigned successfully for the transition to less-polluting compressed natural gas auto-rickshaws and taxis in Delhi and other cities and Vandana Shiva, whose work on behalf of organic agriculture has reached millions of farmers throughout the subcontinent. Because of Jain involvement with numerous businesses, various attempts have been made to infuse business ethics with an ecological sensibility. This article will explore Jain involvement with select businesses at both the theoretical and practical level, examining the writings and work of the late jurist L. M. Singhvi, the late religious leader Acarya Tulsi, educator and activist Satish Kumar, contemporary ethicist Atul Shah, and the Chairman of the Indian Green Building Council, Prem C. Jain.

It is now well recognized that India stands first in the world for polluted cities whose air and water have become quite foul. Litter abounds throughout India. Sewage treatment is woefully inadequate and simply absent from most towns and cities. Industrial and human waste effluent flows into rivers and streams. Particulate matter rises from dung cooking fires and transport vehicles, turning Indian skies gray, choking the population. The World Health Organization has ranked Delhi’s air as the most polluted on the planet and more than 600,000 premature deaths are estimated to occur due to pollution yearly in India. [2]

At a conference convened at Harvard University’s Center for the Study of World Religions in 1998, scholars and activists engaged in a robust conversation about the prospects for a Jain contribution to the contemporary issue of pollution and its mitigation. At the conference, everyone agreed that the situation is dire and unprecedented. This is true of all historic religious; no religion confronted the social sin of ecological imbalance incurred by the human hand as seen in the past century. However, each religion developed a moral code to guide human actions. At the conference, many Jain leaders lifted up the premises and practices of their faith as a torch to light the way out of the current predicament. In particular, Nathmal Tatia suggested that “By strengthening themselves to resist the various temptations put forth by technology and consumer mentality, Jains can perhaps provide an example for living lightly on the planet earth.” [3] Padmanabh S. Jaini cited two examples of Jain innovation in regard to reducing coal pollution and mitigating malaria, stating that “the Jain response to development issues must be mindful of traditional Jain teachings on nonviolence and non-possessiveness.” [4] Sadhvi Shilapi, citing the work on Jain nuns in Bihar to encourage the planting of trees and the adoption of a vegetarian diet, states that “Wants should be reduced, desires curbed, and consumption levels kept within reasonable limits.” [5] Two scholars raised the measured counterpoint that the evidence does not always indicate that Jain vow-based decision making leads to environmentally friendly practice. John Cort pointed out that the Jain focus on one’s liberation from the world ( mokṣa-mārga ) might downplay “the sociobiological contexts in which Jain live and in which any Jain environmental praxis will be located.” [6] Cort also raised the issue that reforestation is sometimes deleterious to those who support themselves by collecting fodder. Paul Dundas noted that Jain acts of worship generally involve the construction of temples and offerings of flowers and other substances, deemed by some Jains to be acts of violence. Dundas, having quoted Abhayadeva Sūri, Haribhadra, and Yaśovijaya, writes that digging in the earth to create wells and temples, clearly an act of violence, constitutes “a lesser evil… is outweighed by the greater goods of water made available to human beings and worship offered to the Jinas.” [7] Simply put, Jains throughout history has advanced an instrumentalist argument in regard to natural resources. If a greater good can be achieved, a little violence is acceptable and even deemed to be necessary. Though he does not state it directly, Dundas implies that this position constitutes an ethical slippery slope, a justification for the anthropocentrism that lies at the core of current ecological crises. Without doubt, simple answers will not suffice.

The Jain approach to environmental ethics rests on premises radically different from those presented in the prophetic monotheisms and racially different from the views held by her sister faiths of Hinduism and Buddhism. Rather than assenting to the notion that the world was created by a benevolent presiding deity, Jainism holds that the world has always been present and will exist forevermore. Rather than following an externally imposed moral code, practitioners of the Jain faith are taught the benefits of self-initiated virtuous action to be performed not for the sake of sheer obedience but for the purposes of self-improvement and purification. In contrast to Hinduism, Jainism does not advocate sacrificial activity such as the killing animals to propitiate wrathful deities. Jainism does not posit an underlying unifying state of consciousness such as Brahman but insists upon the individual integrity of each and every soul, from beginningless time into an infinite future. Unlike Buddhism, Jainism posits the reality of a Self or Soul that holds the potential to attain its unique state of freedom. Buddhism teaches emptiness of self and other; Jainism teaches about a universe filled with innumerable living souls.

Jaina Physics and Metaphysics

The Jaina approach to the natural world is simultaneously respectful and cautious, and above all driven by moral concerns. First, according to Jaina ontology, the world is suffused with life forces ( jῑva ) that merit protection. Hence, the lives contained in particles of earth, drops of water, rays of light, gusts of wind, as well as micro-organisms, plants, and animals must be acknowledged and, to the greatest extent possible, not harmed. Each has entered its particular form due to the materiality of karma. One must exert caution because each harmful action causes the karma surrounding one’s own soul to thicken and darken, obscuring the radiant consciousness of the soul and blocking its ascent to freedom. The Jaina universe thus conceived becomes a moral universe. In order to advance toward freedom, one must develop impeccable adherence to a moral code in order to purge all impedimentary karmas.

Physics and metaphysics, matter and spirit stand intertwined in the Jaina worldview. The tradition posits only four forces that do not possess life: matter or pudgala which can manifest as karma, time, space, and movement. Aside from these, all beings, including elemental realities and plants, possess consciousness, energy, and an innate state of bliss. The following passage from the Ācārāṅga Sūtra , the oldest extant Jaina text (ca. 350 BCE), gives a sense of how the Jainas regard life to pervade all aspects of the natural world:

As the nature of (human beings) is to be born and grow old, so is the nature of plants is to be born and grow old…. As (humans) fall sick when cut, also that (tree) falls sick when cut; as (the human) needs food, so that (plant) needs food; as the (human) will decay, so that (plant) will decay; as the human is not eternal, so that (plant) is not eternal…. As this is changing, so that is changing. One who injures plants does not comprehend and renounce sinful acts. The one who does not injure plants comprehends and renounces sinful acts. Knowing (those plants), a wise person would not act sinfully toward plants, nor cause others to act so, nor allow others to do so. The who knows the causes of sin relating to plants is called a reward-knowing sage. [8]

This theory of plants accords with what Sir James Frazer observed in The Golden Bough . He wrote that for the early Austrians, “the tree feels the cut not less than a wounded man his hurt” [9] David Haberman has written about the affection for trees felt in Varanasi, where he notes that the sentiment can be extended to “tree worship worldwide: trees have not only been commonly thought of as animate beings but also as powerful divine beings who when approached in a respectful manner offer in return life-enhancing benefits to human beings.” [10] In the Jaina context, the divinity of the tree would envision the future possibility that the tree, which is divine like all other souls, might take human birth and enter the path toward freedom from all karmic constraints. This spirit of affection extends to all living beings, to be protected according to the Jaina moral code.

In the coding of a pan-ethical universe, Jainism, particularly in the Tattvārthasūtra (fifth century CE) of Umāsvati, each of the life forms stands within a hierarchy of ascent from elemental beings, microbes, and plants, said to possess the sense of touch; worms, which add the sense of taste; crawling bugs which add smell; flying insects which add sight; and the array of mammals, reptiles, fish, and amphibians who can also hear and think. Life constantly moves from one form to the next. A virtuous human may even take birth in a heavenly realm, while a person of dissipation may endure torture in one of the seven hells. The nature of one’s next birth depends upon action performed in the immediate past body, implying that even microorganisms exert some degree of touch in terms of whom and why they make contact with other forms of life. The human birth stands supreme, being the only domain through which one can perform the necessary karmic purgations to attain freedom, a state at the edge of the universe untouched by the effects of karma.

Jaina Vows as Moral Foundation

This coded universe carries a strong message: regardless of one’s station in life, choice by each and every individual determines future circumstance. If one has earned the good fortune of human birth, a golden opportunity looms: to consciously and purposively commit oneself to the spiritual path of pursuing a life shaped by religiously inspired vows. These vows, applicable to both laypersons and monastics but in varying degrees of intensity, include a set of five greater vows ( mahāvrata ) and a set of twelve lesser vows ( anuvrata ). The Ācārāṅga Sūtra lists five forms of intensity for each of the five great vows, summarized as follows: In the observance of nonviolence ( ahiṃsā ), a monk ( nirgrantha ) must be “careful in his walk;” guard against any thought that “produces cutting or splitting or division and dissension, quarrels, faults, and pains, injures living beings, or kills creatures;” not engage in speech that is “sinful and blamable;” be “careful in lying down his utensils of begging” so as to not “hurt or displace or injure or kill all sorts of living beings,” and must not “eat or drink without inspecting his food and drink” for the same reason ( AS II:15.i.1-5, Jacobi 1968, 203-204).

The second vow, holding to truth ( satya ), requires the five following qualifications: speaking only after deliberation, not speaking from a place of anger, not speaking out of greed, not speaking due to fear, and not speaking for the purpose of ridicule. The third vow, not stealing ( asteya ), entails the pronouncement that “I shall neither take myself what is not given nor cause others to take it, nor consent to their taking it” ( AS II.15.iii.). Because a monk’s livelihood depends upon gathering alms, five further qualifications are given: thoughtfulness about where to ask for food, receipt of permission to do so from one’s supervisory director, moving onto a new place after a fixed period of time in order to not become a burden, always asking permission to visit a new place, and consulting with other monks about the duration of stay.

The fourth vow involves restraint from sexual thought and activity. Acknowledging the range of ways in which sexual desire can manifest, the Ācārāṅga Sūtra proclaims: “I renounce all sexual pleasures, either with gods or humans or animals” ( AS II.15.iv). The five clauses include to “not continually discuss topics relating to women,” to “not regard and contemplate the lovely forms of women,” to “not recall to mind the pleasures and amusements he formerly had with women,” to “not eat and drink too much,” and, to make certain that all options are covered, to “not occupy a bed or couch with women or animals or eunuchs” ( AS II.15.iv).

The fifth vow, nonpossession ( aparigraha ) requires the monk or nun to renounce all attachments. The basic monastic vows restrict the postulant to a bare minimum of possessions, generally a change of robes, a begging bowl, and small satchel for carrying books for members of the Svetambara order, and for male members of Digambara communities, no clothes, only a water pot and satchel. However, the Ācārāṅga Sūtra mandates that the senses must be controlled in each of five expressions. One must vow to “not be attached to, nor delighted with, nor desiring of, nor infatuated by, nor covetous of, nor disturbed by the agreeable or disagreeable sounds” ( AS II.15.v). The text goes on to say that “If it is impossible not to hear sounds which reach the ear, the mendicant should avoid love or hate originated by them.” The same is said of seeing, that if one “sees agreeable and disagreeable forms or colors, one should not be attached.” This formula repeats for smelling, tasting, and touching.

The vow-based morality of the monks is somewhat lighter when reinterpreted for lay Jainas. For instance, Muni Kuśalcanravija states, as summarized by John Cort, a layperson’s adaptation of nonviolence would include “A layperson should not overwork either animals or people… A layperson should not let people and animals in one’s care go hungry.” [11] Similarly, a Jaina business person is advised not to tell lies ( satya ), to not avoid taxes ( asteya ), to be faithful in marriage and avoid “ardent gazing or lewd gestures” ( brahmacarya ), and to avoid attachment to one’s wealth “limiting either the value of various types of possessions or all of one’s possessions in total.” [12] To these five basic vows the layperson adds three vows to restrict activity and four additional vows to undertake spiritual practices. The restrictions of activity include “restricting the geographical limits within which one travels,” “restricting what one uses and consumes,” and “restricting one’s activities, particularly one’s occupation.” [13] This last vow governs suitable professions with the traditional occupations including merchant, artisan, publisher, jeweler, and so forth, all of which avoid direct harm to complex life forms.

The four spiritual vows include undertaking a daily 48 minute meditation, periodic stricter restriction prohibiting travel, occasional days of temporary mendicancy, and making regular donations to monastic communities. All these activities are undertaken within the context of the three moral jewels of the Jaina faith: right outlook, right knowledge, and right action. The moral life begins with outlook and knowledge, from which proceeds moral action. Nine principal beliefs characterize the Jaina view of reality, summarized from the Tattvārthasūtra as follows:

- multiple forms of life forces ( jῑva )

- four non-living forces ( ajῑva ): matter/karma, time, space, movement

- influx of karma adhering to the life force ( āsrava )

- bondage of the soul by karma ( bandha )

- auspicious forms of karma ( puṇya )

- inauspicious forms of karma ( papa )

- stopping the influx ( saṃvara ) through adherence to vows

- sloughing off karma ( nirjarā )

- liberation/freedom ( mokṣa/nirvāṇa/kevala ) [14]

By analyzing activity in light of these categories, one applies knowledge leading to propitious action. The moral life, while essentially teleological, carries benefits in the realm of day to day living, as will be suggested in the examples provided below.

Moral Conscience in Indian History

The influence of Jaina activists in the public sphere has been disproportionate to their numbers throughout Indian history. From earliest recorded times, they have campaigned (along with the Buddhists) against the violent Brāhmaṇical rituals that involve animal sacrifice, with some success. The Jainas became particularly influential during the period of approximately 700 to 1200 in two kingdoms, Karnataka in the south and Gujarat in the west. The Digambara community influenced legislation for a time in the south. King Kumarapala of Gujarat (ruled 1143-1175 CE) converted to Jainism under the tutelage of the great scholar and Svetambara monk Hemacandra (1089-1172). Kumarapala enacted Jaina-friendly legislation and public work projects including temple construction. The Jainas were also somewhat influential at the Mughal court. In 1587, the Svetambara Jaina teacher Hiravijaya Suri (1527-95 CE) so impressed Emperor Akbar that a decree was issued banning the slaughter of animals in the empire during the week-long Jaina celebration of Paryusan, a time of fasting and forgiveness and reconciliation held every September. [15] In the main, however, the Jaina community has been a small minority throughout the history of the subcontinent, currently number somewhere between four and six million, less than one half of one percent of the population. Nonetheless, two 20 th century Jaina figures made significant contributions to moral philosophy within public life in India: Acarya Tulsi (1914-1997) and L. M. Singhvi (1931-2007). Additionally, three 21 st century figures will also be profiled who have advocated for a Jain-informed approach to ecological issues: Satish Kumar, Atul Shah, and Prem Jain (1936-2018).

Acarya Tulsi, Religious Exemplar

Acarya Tulsi was born into a large family in Ladnun, Rajasthan, during British colonial rule. He entered the Svetambara Terapanthi order of Jaina monks at the age of eleven after meeting Acarya Kalugani, its eighth leader. This movement, established by Acarya Bhikshu in the 18 th century, started as a more austere branch of the Sthanakvasi Svetambaras, renowned for their eschewal of all images that are generally used as part of worship. The year of separation came in 1759 when Bhikshu broke all formal ties, bringing six fellow monks with him to establish a new self-initiated order. [16] In many ways, this proved to be a Protestant movement, with Bhikshu decrying the notion that anyone can earn merit through donation. Only strict adherence to the rules of nonviolence can guarantee spiritual progress. From the onset, the Terapanthi pioneered education for Jaina nuns, who previously were not given the opportunity for study afforded to men.

Tulsi was elevated to leadership of the order at the age of 22 and presided for many decades over a dynamic period of growth. The numbers of monks, nuns, and lay followers increased within the Terapanthi community. A new order of Samanis was established, allowing women in particular to postpone their final vows. This has allowed the movement to be of service in particular to the growing number of diaspora Jainas. Samanis have established learning and meditation centers in London, Florida, New Jersey, and Texas. Acarya Tulsi established a learning institute on a hundred acre campus in his home town of Ladnun in 1970, which achieved status as a deemed university in 1991.

Whereas Acarya Tulsi’s successor Acarya Mahapragya focused on the development of a spiritual practice known as Preksha Meditation, Tulsi turned his attention in 1949 toward a campaign known as the Anuvrat Movement. He saw that newly independent India needed a moral compass for guidance and he distilled and reinterpreted the standard Jaina precepts for contemporary times. Though carrying no legislative weight, they remain a talking point for the process of making moral decisions and have influenced monastic and lay leaders within the Terapanthi community. The vows are eleven in number, with explanatory subdivisions:

- I will not deliberately kill any innocent creature (includes suicide and foeticide)

- I will not attack anyone (non-support of aggression; advocacy of disarmament)

- I will not take part in violent agitation or any destructive activity

- I believe in human unity (no discrimination allowed based on color, race, gender, caste

- I will practice religious tolerance (no sectarian violence)

- I will be honest in business and general behavior (commit no harm or deception)

- I will practice continence and limit material possessions

- I will not apply unethical means in elections

- I will not encourage or practice evil social customs

- I will lead a life free from addiction (no alcohol, drugs, tobacco)

- I will strive to minimize environmental pollution (no cutting of trees; no wastage of water) [17]

Simplified versions were prepared over a number of years for students, teachers, business people, officers, employees, voters, and for those interested in spiritual practice. These anuvrats function similarly to the Quaker queries and the Jesuit Examen in that they prompt a reckoning with one’s conscience in a systematic fashion. Though perhaps originally intended as a social movement with broad impact, they have served to sharpen attention within the Terapanthi community worldwide to the wider implications of Jaina moral teachings.

When I interviewed Acharya Tulsi in 1989 and asked him about environmental ethics, he smiled and pointed to the few items he owned: his clothes, a few books, a broom, a begging bowl. He commented that this was the model for environmental ethics: learning to do with less. Less possessions, less harm to the environment. [18]

L. M. Singhvi, Barrister

Member of a mixed Hindu-Jaina family, L. M. Singhvi rose to prominence in the fields of law and government. He served as High Commissioner (Ambassador) from India to Great Britain in the 1990s and as a member of India’s Parliament for many years, in the Lok Sabha (Lower House of Representatives) from 1962 to 1967 and in the Rajya Sabha (Upper House; approx. Senate) from 1998 to 2004. He was tireless in his advocacy of Jaina causes. He presented the Jain Declaration on Nature to Prince Philip in 1990 on the occasion of Jainism’s participation in the World Wildlife Fund Network on Conservation and Religion. It was reprinted in 2002 as the appendix to the book Jainism and Ecology. The Declaration outlines the core principles of Jainism, reframing them as dialogue partners in the emerging discourse on religion and ecology.

The Declaration states that Jainism presents an ecological philosophy and consequently summarizes various aspects of the faith in light of its particular attention to nature. The first part discusses Jaina teachings on nonviolence, interdependence, recognition of multiple perspectives, emphasis on equanimity, and commitment to compassion, empathy, and charity. The second section provides a synopsis of Jaina biological categories as delineated earlier in this chapter. The third and final part highlights the Jain Code of Conduct as exemplary for bringing about environment justice. Key aspects include the restatement of the five Jaina vows (described earlier in this chapter), the history of Jaina kindness to animals, the Jaina advocacy of vegetarianism, the teachings on restraint and avoidance of waste, and finally, the value of charity in the tradition. [19]

Decidedly more complex than Acarya Tulsi’s eleven Anuvrats, this Declaration demonstrates the philosophical commitment of the Jaina community not only to regard life but to advocate for sustaining and protecting life in all of its forms. By asserting the presence of conscious life within soil, rivers, fires, and wind as well as within the overly self-obsessed human realm, Jainism calls for an expansion of view, a broadening of horizon that can serve as an antidote to the damning anthropocentrism that has characterized most of human philosophical endeavor. When Singhvi writes about compassion and empathy, he intends not to limit one’s scope to the merely human but to include all the animals and plants and the elements themselves.

Satish Kumar, Contemporary Ethicist

Satish Kumar, who served as a Jain Therapanthi Svetambara monk for nine years before joining the Bhū Dān movement of Vinobha Bhave and subsequently founded Schumacher College in southwest England, has long championed the social engagement of Jain values with public life. He edited Resurgence , the leading journal for ecological spirituality in Britain, for several decades, contributing himself many pieces on how the Jain value of simplicity intersects with ecological values. [20] At Schumacher College, which Satish Kumar co-founded in 1990, spirituality and ecology are taught in tandem, inspired in large part by the nature-friendly aspects of Jain thought and practice. [21]