- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- A new framework for...

A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance

- Related content

- Peer review

- Kathryn Skivington , research fellow 1 ,

- Lynsay Matthews , research fellow 1 ,

- Sharon Anne Simpson , professor of behavioural sciences and health 1 ,

- Peter Craig , professor of public health evaluation 1 ,

- Janis Baird , professor of public health and epidemiology 2 ,

- Jane M Blazeby , professor of surgery 3 ,

- Kathleen Anne Boyd , reader in health economics 4 ,

- Neil Craig , acting head of evaluation within Public Health Scotland 5 ,

- David P French , professor of health psychology 6 ,

- Emma McIntosh , professor of health economics 4 ,

- Mark Petticrew , professor of public health evaluation 7 ,

- Jo Rycroft-Malone , faculty dean 8 ,

- Martin White , professor of population health research 9 ,

- Laurence Moore , unit director 1

- 1 MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, Institute of Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK

- 2 Medical Research Council Lifecourse Epidemiology Unit, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK

- 3 Medical Research Council ConDuCT-II Hub for Trials Methodology Research and Bristol Biomedical Research Centre, Bristol, UK

- 4 Health Economics and Health Technology Assessment Unit, Institute of Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK

- 5 Public Health Scotland, Glasgow, UK

- 6 Manchester Centre for Health Psychology, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

- 7 London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK

- 8 Faculty of Health and Medicine, Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK

- 9 Medical Research Council Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

- Correspondence to: K Skivington Kathryn.skivington{at}glasgow.ac.uk

- Accepted 9 August 2021

The UK Medical Research Council’s widely used guidance for developing and evaluating complex interventions has been replaced by a new framework, commissioned jointly by the Medical Research Council and the National Institute for Health Research, which takes account of recent developments in theory and methods and the need to maximise the efficiency, use, and impact of research.

Complex interventions are commonly used in the health and social care services, public health practice, and other areas of social and economic policy that have consequences for health. Such interventions are delivered and evaluated at different levels, from individual to societal levels. Examples include a new surgical procedure, the redesign of a healthcare programme, and a change in welfare policy. The UK Medical Research Council (MRC) published a framework for researchers and research funders on developing and evaluating complex interventions in 2000 and revised guidance in 2006. 1 2 3 Although these documents continue to be widely used and are now accompanied by a range of more detailed guidance on specific aspects of the research process, 4 5 6 7 8 several important conceptual, methodological and theoretical developments have taken place since 2006. These developments have been included in a new framework commissioned by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) and the MRC. 9 The framework aims to help researchers work with other stakeholders to identify the key questions about complex interventions, and to design and conduct research with a diversity of perspectives and appropriate choice of methods.

Summary points

Complex intervention research can take an efficacy, effectiveness, theory based, and/or systems perspective, the choice of which is based on what is known already and what further evidence would add most to knowledge

Complex intervention research goes beyond asking whether an intervention works in the sense of achieving its intended outcome—to asking a broader range of questions (eg, identifying what other impact it has, assessing its value relative to the resources required to deliver it, theorising how it works, taking account of how it interacts with the context in which it is implemented, how it contributes to system change, and how the evidence can be used to support real world decision making)

A trade-off exists between precise unbiased answers to narrow questions and more uncertain answers to broader, more complex questions; researchers should answer the questions that are most useful to decision makers rather than those that can be answered with greater certainty

Complex intervention research can be considered in terms of phases, although these phases are not necessarily sequential: development or identification of an intervention, assessment of feasibility of the intervention and evaluation design, evaluation of the intervention, and impactful implementation

At each phase, six core elements should be considered to answer the following questions:

How does the intervention interact with its context?

What is the underpinning programme theory?

How can diverse stakeholder perspectives be included in the research?

What are the key uncertainties?

How can the intervention be refined?

What are the comparative resource and outcome consequences of the intervention?

The answers to these questions should be used to decide whether the research should proceed to the next phase, return to a previous phase, repeat a phase, or stop

Development of the Framework for Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions

The updated Framework for Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions is the culmination of a process that included four stages:

A gap analysis to identify developments in the methods and practice since the previous framework was published

A full day expert workshop, in May 2018, of 36 participants to discuss the topics identified in the gap analysis

An open consultation on a draft of the framework in April 2019, whereby we sought stakeholder opinion by advertising via social media, email lists and other networks for written feedback (52 detailed responses were received from stakeholders internationally)

Redraft using findings from the previous stages, followed by a final expert review.

We also sought stakeholder views at various interactive workshops throughout the development of the framework: at the annual meetings of the Society for Social Medicine and Population Health (2018), the UK Society for Behavioural Medicine (2017, 2018), and internationally at the International Congress of Behavioural Medicine (2018). The entire process was overseen by a scientific advisory group representing the range of relevant NIHR programmes and MRC population health investments. The framework was reviewed by the MRC-NIHR Methodology Research Programme Advisory Group and then approved by the MRC Population Health Sciences Group in March 2020 before undergoing further external peer and editorial review through the NIHR Journals Library peer review process. More detailed information and the methods used to develop this new framework are described elsewhere. 9 This article introduces the framework and summarises the main messages for producers and users of evidence.

What are complex interventions?

An intervention might be considered complex because of properties of the intervention itself, such as the number of components involved; the range of behaviours targeted; expertise and skills required by those delivering and receiving the intervention; the number of groups, settings, or levels targeted; or the permitted level of flexibility of the intervention or its components. For example, the Links Worker Programme was an intervention in primary care in Glasgow, Scotland, that aimed to link people with community resources to help them “live well” in their communities. It targeted individual, primary care (general practitioner (GP) surgery), and community levels. The intervention was flexible in that it could differ between primary care GP surgeries. In addition, the Link Workers did not support just one specific health or wellbeing issue: bereavement, substance use, employment, and learning difficulties were all included. 10 11 The complexity of this intervention had implications for many aspects of its evaluation, such as the choice of appropriate outcomes and processes to assess.

Flexibility in intervention delivery and adherence might be permitted to allow for variation in how, where, and by whom interventions are delivered and received. Standardisation of interventions could relate more to the underlying process and functions of the intervention than on the specific form of components delivered. 12 For example, in surgical trials, protocols can be designed with flexibility for intervention delivery. 13 Interventions require a theoretical deconstruction into components and then agreement about permissible and prohibited variation in the delivery of those components. This approach allows implementation of a complex intervention to vary across different contexts yet maintain the integrity of the core intervention components. Drawing on this approach in the ROMIO pilot trial, core components of minimally invasive oesophagectomy were agreed and subsequently monitored during main trial delivery using photography. 14

Complexity might also arise through interactions between the intervention and its context, by which we mean “any feature of the circumstances in which an intervention is conceived, developed, implemented and evaluated.” 6 15 16 17 Much of the criticism of and extensions to the existing framework and guidance have focused on the need for greater attention on understanding how and under what circumstances interventions bring about change. 7 15 18 The importance of interactions between the intervention and its context emphasises the value of identifying mechanisms of change, where mechanisms are the causal links between intervention components and outcomes; and contextual factors, which determine and shape whether and how outcomes are generated. 19

Thus, attention is given not only to the design of the intervention itself but also to the conditions needed to realise its mechanisms of change and/or the resources required to support intervention reach and impact in real world implementation. For example, in a cluster randomised trial of ASSIST (a peer led, smoking prevention intervention), researchers found that the intervention worked particularly well in cohesive communities that were served by one secondary school where peer supporters were in regular contact with their peers—a key contextual factor consistent with diffusion of innovation theory, which underpinned the intervention design. 20 A process evaluation conducted alongside a trial of robot assisted surgery identified key contextual factors to support effective implementation of this procedure, including engaging staff at different levels and surgeons who would not be using robot assisted surgery, whole team training, and an operating theatre of suitable size. 21

With this framing, complex interventions can helpfully be considered as events in systems. 16 Thinking about systems helps us understand the interaction between an intervention and the context in which it is implemented in a dynamic way. 22 Systems can be thought of as complex and adaptive, 23 characterised by properties such as emergence, feedback, adaptation, and self-organisation ( table 1 ).

Properties and examples of complex adaptive systems

- View inline

For complex intervention research to be most useful to decision makers, it should take into account the complexity that arises both from the intervention’s components and from its interaction with the context in which it is being implemented.

Research perspectives

The previous framework and guidance were based on a paradigm in which the salient question was to identify whether an intervention was effective. Complex intervention research driven primarily by this question could fail to deliver interventions that are implementable, cost effective, transferable, and scalable in real world conditions. To deliver solutions for real world practice, complex intervention research requires strong and early engagement with patients, practitioners, and policy makers, shifting the focus from the “binary question of effectiveness” 26 to whether and how the intervention will be acceptable, implementable, cost effective, scalable, and transferable across contexts. In line with a broader conception of complexity, the scope of complex intervention research needs to include the development, identification, and evaluation of whole system interventions and the assessment of how interventions contribute to system change. 22 27 The new framework therefore takes a pluralistic approach and identifies four perspectives that can be used to guide the design and conduct of complex intervention research: efficacy, effectiveness, theory based, and systems ( table 2 ).

Although each research perspective prompts different types of research question, they should be thought of as overlapping rather than mutually exclusive. For example, theory based and systems perspectives to evaluation can be used in conjunction, 33 while an effectiveness evaluation can draw on a theory based or systems perspective through an embedded process evaluation to explore how and under what circumstances outcomes are achieved. 34 35 36

Most complex health intervention research so far has taken an efficacy or effectiveness perspective and for some research questions these perspectives will continue to be the most appropriate. However, some questions equally relevant to the needs of decision makers cannot be answered by research restricted to an efficacy or effectiveness perspective. A wider range and combination of research perspectives and methods, which answer questions beyond efficacy and effectiveness, need to be used by researchers and supported by funders. Doing so will help to improve the extent to which key questions for decision makers can be answered by complex intervention research. Example questions include:

Will this effective intervention reproduce the effects found in the trial when implemented here?

Is the intervention cost effective?

What are the most important things we need to do that will collectively improve health outcomes?

In the absence of evidence from randomised trials and the infeasibility of conducting such a trial, what does the existing evidence suggest is the best option now and how can this be evaluated?

What wider changes will occur as a result of this intervention?

How are the intervention effects mediated by different settings and contexts?

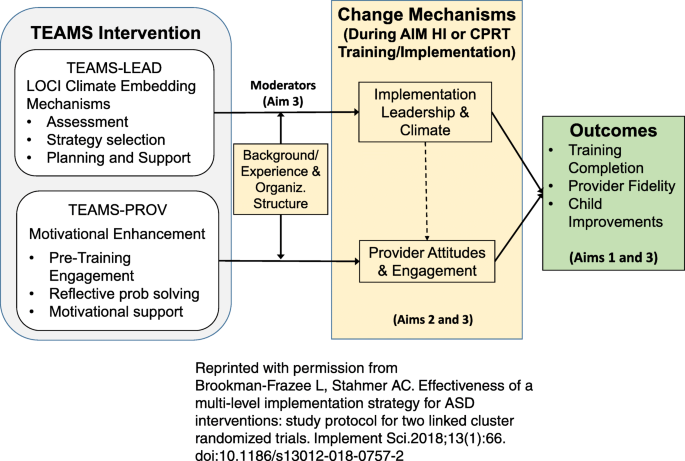

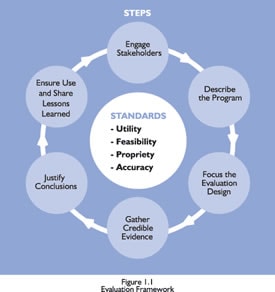

Phases and core elements of complex intervention research

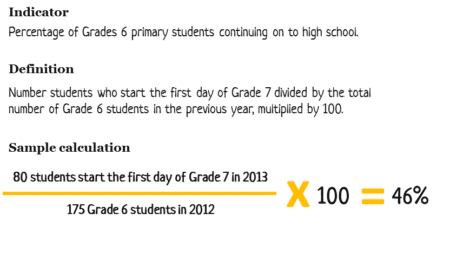

The framework divides complex intervention research into four phases: development or identification of the intervention, feasibility, evaluation, and implementation ( fig 1 ). A research programme might begin at any phase, depending on the key uncertainties about the intervention in question. Repeating phases is preferable to automatic progression if uncertainties remain unresolved. Each phase has a common set of core elements—considering context, developing and refining programme theory, engaging stakeholders, identifying key uncertainties, refining the intervention, and economic considerations. These elements should be considered early and continually revisited throughout the research process, and especially before moving between phases (for example, between feasibility testing and evaluation).

Framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions. Context=any feature of the circumstances in which an intervention is conceived, developed, evaluated, and implemented; programme theory=describes how an intervention is expected to lead to its effects and under what conditions—the programme theory should be tested and refined at all stages and used to guide the identification of uncertainties and research questions; stakeholders=those who are targeted by the intervention or policy, involved in its development or delivery, or more broadly those whose personal or professional interests are affected (that is, who have a stake in the topic)—this includes patients and members of the public as well as those linked in a professional capacity; uncertainties=identifying the key uncertainties that exist, given what is already known and what the programme theory, research team, and stakeholders identify as being most important to discover—these judgments inform the framing of research questions, which in turn govern the choice of research perspective; refinement=the process of fine tuning or making changes to the intervention once a preliminary version (prototype) has been developed; economic considerations=determining the comparative resource and outcome consequences of the interventions for those people and organisations affected

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Core elements

The effects of a complex intervention might often be highly dependent on context, such that an intervention that is effective in some settings could be ineffective or even harmful elsewhere. 6 As the examples in table 1 show, interventions can modify the contexts in which they are implemented, by eliciting responses from other agents, or by changing behavioural norms or exposure to risk, so that their effects will also vary over time. Context can be considered as both dynamic and multi-dimensional. Key dimensions include physical, spatial, organisational, social, cultural, political, or economic features of the healthcare, health system, or public health contexts in which interventions are implemented. For example, the evaluation of the Breastfeeding In Groups intervention found that the context of the different localities (eg, staff morale and suitable premises) influenced policy implementation and was an explanatory factor in why breastfeeding rates increased in some intervention localities and declined in others. 37

Programme theory

Programme theory describes how an intervention is expected to lead to its effects and under what conditions. It articulates the key components of the intervention and how they interact, the mechanisms of the intervention, the features of the context that are expected to influence those mechanisms, and how those mechanisms might influence the context. 38 Programme theory can be used to promote shared understanding of the intervention among diverse stakeholders, and to identify key uncertainties and research questions. Where an intervention (such as a policy) is developed by others, researchers still need to theorise the intervention before attempting to evaluate it. 39 Best practice is to develop programme theory at the beginning of the research project with involvement of diverse stakeholders, based on evidence and theory from relevant fields, and to refine it during successive phases. The EPOCH trial tested a large scale quality improvement programme aimed at improving 90 day survival rates for patients undergoing emergency abdominal surgery; it included a well articulated programme theory at the outset, which supported the tailoring of programme delivery to local contexts. 40 The development, implementation, and post-study reflection of the programme theory resulted in suggested improvements for future implementation of the quality improvement programme.

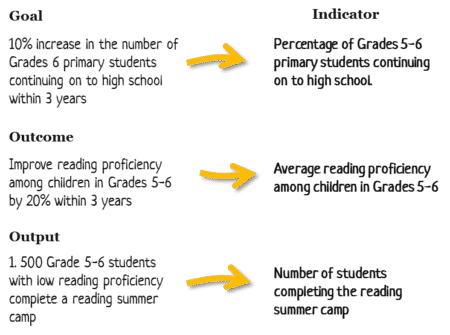

A refined programme theory is an important evaluation outcome and is the principal aim where a theory based perspective is taken. Improved programme theory will help inform transferability of interventions across settings and help produce evidence and understanding that is useful to decision makers. In addition to full articulation of programme theory, it can help provide visual representations—for example, using a logic model, 41 42 43 realist matrix, 44 or a system map, 45 with the choice depending on which is most appropriate for the research perspective and research questions. Although useful, any single visual representation is unlikely to sufficiently articulate the programme theory—it should always be articulated well within the text of publications, reports, and funding applications.

Stakeholders

Stakeholders include those individuals who are targeted by the intervention or policy, those involved in its development or delivery, or those whose personal or professional interests are affected (that is, all those who have a stake in the topic). Patients and the public are key stakeholders. Meaningful engagement with appropriate stakeholders at each phase of the research is needed to maximise the potential of developing or identifying an intervention that is likely to have positive impacts on health and to enhance prospects of achieving changes in policy or practice. For example, patient and public involvement 46 activities in the PARADES programme, which evaluated approaches to reduce harm and improve outcomes for people with bipolar disorder, were wide ranging and central to the project. 47 Involving service users with lived experiences of bipolar disorder had many benefits, for example, it enhanced the intervention but also improved the evaluation and dissemination methods. Service users involved in the study also had positive outcomes, including more settled employment and progression to further education. Broad thinking and consultation is needed to identify a diverse range of appropriate stakeholders.

The purpose of stakeholder engagement will differ depending on the context and phase of the research, but is essential for prioritising research questions, the co-development of programme theory, choosing the most useful research perspective, and overcoming practical obstacles to evaluation and implementation. Researchers should nevertheless be mindful of conflicts of interest among stakeholders and use transparent methods to record potential conflicts of interest. Research should not only elicit stakeholder priorities, but also consider why they are priorities. Careful consideration of the appropriateness and methods of identification and engagement of stakeholders is needed. 46 48

Key uncertainties

Many questions could be answered at each phase of the research process. The design and conduct of research need to engage pragmatically with the multiple uncertainties involved and offer a flexible and emergent approach to exploring them. 15 Therefore, researchers should spend time developing the programme theory, clearly identifying the remaining uncertainties, given what is already known and what the research team and stakeholders identify as being most important to determine. Judgments about the key uncertainties inform the framing of research questions, which in turn govern the choice of research perspective.

Efficacy trials of relatively uncomplicated interventions in tightly controlled conditions, where research questions are answered with great certainty, will always be important, but translation of the evidence into the diverse settings of everyday practice is often highly problematic. 27 For intervention research in healthcare and public health settings to take on more challenging evaluation questions, greater priority should be given to mixed methods, theory based, or systems evaluation that is sensitive to complexity and that emphasises implementation, context, and system fit. This approach could help improve understanding and identify important implications for decision makers, albeit with caveats, assumptions, and limitations. 22 Rather than maintaining the established tendency to prioritise strong research designs that answer some questions with certainty but are unsuited to resolving many important evaluation questions, this more inclusive, deliberative process could place greater value on equivocal findings that nevertheless inform important decisions where evidence is sparse.

Intervention refinement

Within each phase of complex intervention research and on transition from one phase to another, the intervention might need to be refined, on the basis of data collected or development of programme theory. 4 The feasibility and acceptability of interventions can be improved by engaging potential intervention users to inform refinements. For example, an online physical activity planner for people with diabetes mellitus was found to be difficult to use, resulting in the tool providing incorrect personalised advice. To improve usability and the advice given, several iterations of the planner were developed on the basis of interviews and observations. This iterative process led to the refined planner demonstrating greater feasibility and accuracy. 49

Refinements should be guided by the programme theory, with acceptable boundaries agreed and specified at the beginning of each research phase, and with transparent reporting of the rationale for change. Scope for refinement might also be limited by the policy or practice context. Refinement will be rare in the evaluation phase of efficacy and effectiveness research, where interventions will ideally not change or evolve within the course of the study. However, between the phases of research and within systems and theory based evaluation studies, refinement of interventions in response to accumulated data or as an adaptive and variable response to context and system change are likely to be desirable features of the intervention and a key focus of the research.

Economic considerations

Economic evaluation—the comparative analysis of alternative courses of action in terms of both costs (resource use) and consequences (outcomes, effects)—should be a core component of all phases of intervention research. Early engagement of economic expertise will help identify the scope of costs and benefits to assess in order to answer questions that matter most to decision makers. 50 Broad ranging approaches such as cost benefit analysis or cost consequence analysis, which seek to capture the full range of health and non-health costs and benefits across different sectors, 51 will often be more suitable for an economic evaluation of a complex intervention than narrower approaches such as cost effectiveness or cost utility analysis. For example, evaluation of the New Orleans Intervention Model for infants entering foster care in Glasgow included short and long term economic analysis from multiple perspectives (the UK’s health service and personal social services, public sector, and wider societal perspectives); and used a range of frameworks, including cost utility and cost consequence analysis, to capture changes in the intersectoral costs and outcomes associated with child maltreatment. 52 53 The use of multiple economic evaluation frameworks provides decision makers with a comprehensive, multi-perspective guide to the cost effectiveness of the New Orleans Intervention Model.

Developing or identifying a complex intervention

Development refers to the whole process of designing and planning an intervention, from initial conception through to feasibility, pilot, or evaluation study. Guidance on intervention development has recently been developed through the INDEX study 4 ; although here we highlight that complex intervention research does not always begin with new or researcher led interventions. For example:

A key source of intervention development might be an intervention that has been developed elsewhere and has the possibility of being adapted to a new context. Adaptation of existing interventions could include adapting to a new population, to a new setting, 54 55 or to target other outcomes (eg, a smoking prevention intervention being adapted to tackle substance misuse and sexual health). 20 56 57 A well developed programme theory can help identify what features of the antecedent intervention(s) need to be adapted for different applications, and the key mechanisms that should be retained even if delivered slightly differently. 54 58

Policy or practice led interventions are an important focus of evaluation research. Again, uncovering the implicit theoretical basis of an intervention and developing a programme theory is essential to identifying key uncertainties and working out how the intervention might be evaluated. This step is important, even if rollout has begun, because it supports the identification of mechanisms of change, important contextual factors, and relevant outcome measures. For example, researchers evaluating the UK soft drinks industry levy developed a bounded conceptual system map to articulate their understanding (drawing on stakeholder views and document review) of how the intervention was expected to work. This system map guided the evaluation design and helped identify data sources to support evaluation. 45 Another example is a recent analysis of the implicit theory of the NHS diabetes prevention programme, involving analysis of documentation by NHS England and four providers, showing that there was no explicit theoretical basis for the programme, and no logic model showing how the intervention was expected to work. This meant that the justification for the inclusion of intervention components was unclear. 59

Intervention identification and intervention development represent two distinct pathways of evidence generation, 60 but in both cases, the key considerations in this phase relate to the core elements described above.

Feasibility

A feasibility study should be designed to assess predefined progression criteria that relate to the evaluation design (eg, reducing uncertainty around recruitment, data collection, retention, outcomes, and analysis) or the intervention itself (eg, around optimal content and delivery, acceptability, adherence, likelihood of cost effectiveness, or capacity of providers to deliver the intervention). If the programme theory suggests that contextual or implementation factors might influence the acceptability, effectiveness, or cost effectiveness of the intervention, these questions should be considered.

Despite being overlooked or rushed in the past, the value of feasibility testing is now widely accepted with key terms and concepts well defined. 61 62 Before initiating a feasibility study, researchers should consider conducting an evaluability assessment to determine whether and how an intervention can usefully be evaluated. Evaluability assessment involves collaboration with stakeholders to reach agreement on the expected outcomes of the intervention, the data that could be collected to assess processes and outcomes, and the options for designing the evaluation. 63 The end result is a recommendation on whether an evaluation is feasible, whether it can be carried out at a reasonable cost, and by which methods. 64

Economic modelling can be undertaken at the feasibility stage to assess the likelihood that the expected benefits of the intervention justify the costs (including the cost of further research), and to help decision makers decide whether proceeding to a full scale evaluation is worthwhile. 65 Depending on the results of the feasibility study, further work might be required to progressively refine the intervention before embarking on a full scale evaluation.

The new framework defines evaluation as going beyond asking whether an intervention works (in the sense of achieving its intended outcome), to a broader range of questions including identifying what other impact it has, theorising how it works, taking account of how it interacts with the context in which it is implemented, how it contributes to system change, and how the evidence can be used to support decision making in the real world. This implies a shift from an exclusive focus on obtaining unbiased estimates of effectiveness 66 towards prioritising the usefulness of information for decision making in selecting the optimal research perspective and in prioritising answerable research questions.

A crucial aspect of evaluation design is the choice of outcome measures or evidence of change. Evaluators should work with stakeholders to assess which outcomes are most important, and how to deal with multiple outcomes in the analysis with due consideration of statistical power and transparent reporting. A sharp distinction between one primary outcome and several secondary outcomes is not necessarily appropriate, particularly where the programme theory identifies impacts across a range of domains. Where needed to support the research questions, prespecified subgroup analyses should be carried out and reported. Even where such analyses are underpowered, they should be included in the protocol because they might be useful for subsequent meta-analyses, or for developing hypotheses for testing in further research. Outcome measures could capture changes to a system rather than changes in individuals. Examples include changes in relationships within an organisation, the introduction of policies, changes in social norms, or normalisation of practice. Such system level outcomes include how changing the dynamics of one part of a system alters behaviours in other parts, such as the potential for displacement of smoking into the home after a public smoking ban.

A helpful illustration of the use of system level outcomes is the evaluation of the Delaware Young Health Program—an initiative to improve the health and wellbeing of young people in Delaware, USA. The intervention aimed to change underlying system dynamics, structures, and conditions, so the evaluation identified systems oriented research questions and methods. Three systems science methods were used: group model building and viable systems model assessment to identify underlying patterns and structures; and social network analysis to evaluate change in relationships over time. 67

Researchers have many study designs to choose from, and different designs are optimally suited to consider different research questions and different circumstances. 68 Extensions to standard designs of randomised controlled trials (including adaptive designs, SMART trials (sequential multiple assignment randomised trials), n-of-1 trials, and hybrid effectiveness-implementation designs) are important areas of methods development to improve the efficiency of complex intervention research. 69 70 71 72 Non-randomised designs and modelling approaches might work best if a randomised design is not practical, for example, in natural experiments or systems evaluations. 5 73 74 A purely quantitative approach, using an experimental design with no additional elements such as a process evaluation, is rarely adequate for complex intervention research, where qualitative and mixed methods designs might be necessary to answer questions beyond effectiveness. In many evaluations, the nature of the intervention, the programme theory, or the priorities of stakeholders could lead to a greater focus on improving theories about how to intervene. In this view, effect estimates are inherently context bound, so that average effects are not a useful guide to decision makers working in different contexts. Contextualised understandings of how an intervention induces change might be more useful, as well as details on the most important enablers and constraints on its delivery across a range of settings. 7

Process evaluation can answer questions around fidelity and quality of implementation (eg, what is implemented and how?), mechanisms of change (eg, how does the delivered intervention produce change?), and context (eg, how does context affect implementation and outcomes?). 7 Process evaluation can help determine why an intervention fails unexpectedly or has unanticipated consequences, or why it works and how it can be optimised. Such findings can facilitate further development of the intervention programme theory. 75 In a theory based or systems evaluation, there is not necessarily such a clear distinction between process and outcome evaluation as there is in an effectiveness study. 76 These perspectives could prioritise theory building over evidence production and use case study or simulation methods to understand how outcomes or system behaviour are generated through intervention. 74 77

Implementation

Early consideration of implementation increases the potential of developing an intervention that can be widely adopted and maintained in real world settings. Implementation questions should be anticipated in the intervention programme theory, and considered throughout the phases of intervention development, feasibility testing, process, and outcome evaluation. Alongside implementation specific outcomes (such as reach or uptake of services), attention to the components of the implementation strategy, and contextual factors that support or hinder the achievement of impacts, are key. Some flexibility in intervention implementation might support intervention transferability into different contexts (an important aspect of long term implementation 78 ), provided that the key functions of the programme are maintained, and that the adaptations made are clearly understood. 8

In the ASSIST study, 20 a school based, peer led intervention for smoking prevention, researchers considered implementation at each phase. The intervention was developed to have minimal disruption on school resources; the feasibility study resulted in intervention refinements to improve acceptability and improve reach to male students; and in the evaluation (cluster randomised controlled trial), the intervention was delivered as closely as possible to real world implementation. Drawing on the process evaluation, the implementation included an intervention manual that identified critical components and other components that could be adapted or dropped to allow flexible implementation while achieving delivery of the key mechanisms of change; and a training manual for the trainers and ongoing quality assurance built into rollout for the longer term.

In a natural experimental study, evaluation takes place during or after the implementation of the intervention in a real world context. Highly pragmatic effectiveness trials or specific hybrid effectiveness-implementation designs also combine effectiveness and implementation outcomes in one study, with the aim of reducing time for translation of research on effectiveness into routine practice. 72 79 80

Implementation questions should be included in economic considerations during the early stages of intervention and study development. How the results of economic analyses are reported and presented to decision makers can affect whether and how they act on the results. 81 A key consideration is how to deal with interventions across different sectors, where those paying for interventions and those receiving the benefits of them could differ, reducing the incentive to implement an intervention, even if shown to be beneficial and cost effective. Early engagement with appropriate stakeholders will help frame appropriate research questions and could anticipate any implementation challenges that might arise. 82

Conclusions

One of the motivations for developing this new framework was to answer calls for a change in research priorities, towards allocating greater effort and funding to research that can have the optimum impact on healthcare or population health outcomes. The framework challenges the view that unbiased estimates of effectiveness are the cardinal goal of evaluation. It asserts that improving theories and understanding how interventions contribute to change, including how they interact with their context and wider dynamic systems, is an equally important goal. For some complex intervention research problems, an efficacy or effectiveness perspective will be the optimal approach, and a randomised controlled trial will provide the best design to achieve an unbiased estimate. For others, alternative perspectives and designs might work better, or might be the only way to generate new knowledge to reduce decision maker uncertainty.

What is important for the future is that the scope of intervention research is not constrained by an unduly limited set of perspectives and approaches that might be less risky to commission and more likely to produce a clear and unbiased answer to a specific question. A bolder approach is needed—to include methods and perspectives where experience is still quite limited, but where we, supported by our workshop participants and respondents to our consultations, believe there is an urgent need to make progress. This endeavour will involve mainstreaming new methods that are not yet widely used, as well as undertaking methodological innovation and development. The deliberative and flexible approach that we encourage is intended to reduce research waste, 83 maximise usefulness for decision makers, and increase the efficiency with which complex intervention research generates knowledge that contributes to health improvement.

Monitoring the use of the framework and evaluating its acceptability and impact is important but has been lacking in the past. We encourage research funders and journal editors to support the diversity of research perspectives and methods that are advocated here and to seek evidence that the core elements are attended to in research design and conduct. We have developed a checklist to support the preparation of funding applications, research protocols, and journal publications. 9 This checklist offers one way to monitor impact of the guidance on researchers, funders, and journal editors.

We recommend that the guidance is continually updated, and future updates continue to adopt a broad, pluralist perspective. Given its wider scope, and the range of detailed guidance that is now available on specific methods and topics, we believe that the framework is best seen as meta-guidance. Further editions should be published in a fluid, web based format, and more frequently updated to incorporate new material, further case studies, and additional links to other new resources.

Acknowledgments

We thank the experts who provided input at the workshop, those who responded to the consultation, and those who provided advice and review throughout the process. The many people involved are acknowledged in the full framework document. 9 Parts of this manuscript have been reproduced (some with edits and formatting changes), with permission, from that longer framework document.

Contributors: All authors made a substantial contribution to all stages of the development of the framework—they contributed to its development, drafting, and final approval. KS and LMa led the writing of the framework, and KS wrote the first draft of this paper. PC, SAS, and LMo provided critical insights to the development of the framework and contributed to writing both the framework and this paper. KS, LMa, SAS, PC, and LMo facilitated the expert workshop, KS and LMa developed the gap analysis and led the analysis of the consultation. KAB, NC, and EM contributed the economic components to the framework. The scientific advisory group (JB, JMB, DPF, MP, JR-M, and MW) provided feedback and edits on drafts of the framework, with particular attention to process evaluation (JB), clinical research (JMB), implementation (JR-M, DPF), systems perspective (MP), theory based perspective (JR-M), and population health (MW). LMo is senior author. KS and LMo are the guarantors of this work and accept the full responsibility for the finished article. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting authorship criteria have been omitted.

Funding: The work was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (Department of Health and Social Care 73514) and Medical Research Council (MRC). Additional time on the study was funded by grants from the MRC for KS (MC_UU_12017/11, MC_UU_00022/3), LMa, SAS, and LMo (MC_UU_12017/14, MC_UU_00022/1); PC (MC_UU_12017/15, MC_UU_00022/2); and MW (MC_UU_12015/6 and MC_UU_00006/7). Additional time on the study was also funded by grants from the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorates for KS (SPHSU11 and SPHSU18); LMa, SAS, and LMo (SPHSU14 and SPHSU16); and PC (SPHSU13 and SPHSU15). KS and SAS were also supported by an MRC Strategic Award (MC_PC_13027). JMB received funding from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol and by the MRC ConDuCT-II Hub (Collaboration and innovation for Difficult and Complex randomised controlled Trials In Invasive procedures - MR/K025643/1). DF is funded in part by the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre (IS-BRC-1215-20007) and NIHR Applied Research Collaboration - Greater Manchester (NIHR200174). MP is funded in part as director of the NIHR’s Public Health Policy Research Unit. This project was overseen by a scientific advisory group that comprised representatives of NIHR research programmes, of the MRC/NIHR Methodology Research Programme Panel, of key MRC population health research investments, and authors of the 2006 guidance. A prospectively agreed protocol, outlining the workplan, was agreed with MRC and NIHR, and signed off by the scientific advisory group. The framework was reviewed and approved by the MRC/NIHR Methodology Research Programme Advisory Group and MRC Population Health Sciences Group and completed NIHR HTA Monograph editorial and peer review processes.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: support from the NIHR, MRC, and the funders listed above for the submitted work; KS has project grant funding from the Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office; SAS is a former member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Clinical Evaluation and Trials Programme Panel (November 2016 - November 2020) and member of the Chief Scientist Office Health HIPS Committee (since 2018) and NIHR Policy Research Programme (since November 2019), and has project grant funding from the Economic and Social Research Council, MRC, and NIHR; LMo is a former member of the MRC-NIHR Methodology Research Programme Panel (2015-19) and MRC Population Health Sciences Group (2015-20); JB is a member of the NIHR Public Health Research Funding Committee (since May 2019), and a core member (since 2016) and vice chairperson (since 2018) of a public health advisory committee of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; JMB is a former member of the NIHR Clinical Trials Unit Standing Advisory Committee (2015-19); DPF is a former member of the NIHR Public Health Research programme research funding board (2015-2019), the MRC-NIHR Methodology Research Programme panel member (2014-2018), and is a panel member of the Research Excellence Framework 2021, subpanel 2 (public health, health services, and primary care; November 2020 - February 2022), and has grant funding from the European Commission, NIHR, MRC, Natural Environment Research Council, Prevent Breast Cancer, Breast Cancer Now, Greater Sport, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, Christie Hospital NHS Trust, and BXS GP; EM is a member of the NIHR Public Health Research funding board; MP has grant funding from the MRC, UK Prevention Research Partnership, and NIHR; JR-M is programme director and chairperson of the NIHR’s Health Services Delivery Research Programme (since 2014) and member of the NIHR Strategy Board (since 2014); MW received a salary as director of the NIHR PHR Programme (2014-20), has grant funding from NIHR, and is a former member of the MRC’s Population Health Sciences Strategic Committee (July 2014 to June 2020). There are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Patient and public involvement: This project was methodological; views of patients and the public were included at the open consultation stage of the update. The open consultation, involving access to an initial draft, was promoted to our networks via email and digital channels, such as our unit Twitter account ( @theSPHSU ). We received five responses from people who identified as service users (rather than researchers or professionals in a relevant capacity). Their input included helpful feedback on the main complexity diagram, the different research perspectives, the challenge of moving interventions between different contexts and overall readability and accessibility of the document. Several respondents also highlighted useful signposts to include for readers. Various dissemination events are planned, but as this project is methodological we will not specifically disseminate to patients and the public beyond the planned dissemination activities.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

- Macintyre S ,

- Nazareth I ,

- Petticrew M ,

- Medical Research Council Guidance

- Campbell M ,

- Fitzpatrick R ,

- O’Cathain A ,

- Gunnell D ,

- Ruggiero ED ,

- Frohlich KL ,

- Copeland L ,

- Skivington K ,

- Matthews L ,

- Simpson SA ,

- Hawkins K ,

- Fitzpatrick B ,

- Mercer SW ,

- Blencowe NS ,

- Skilton A ,

- ROMIO Study team

- Greenhalgh T ,

- Petticrew M

- Campbell R ,

- Starkey F ,

- Holliday J ,

- ↵ Randell R, Honey S, Hindmarsh J, et al. A realist process evaluation of robot-assisted surgery: integration into routine practice and impacts on communication, collaboration and decision-making . NIHR Journals Library, 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK447438/ .

- ↵ The Health Foundation. Evidence Scan. Complex adaptive systems. Health Foundation 2010. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/complex-adaptive-systems .

- Wiggins M ,

- Sawtell M ,

- Robinson M ,

- Kessler R ,

- Folegatti PM ,

- Oxford COVID Vaccine Trial Group

- Clemens SAC ,

- Shearer JC ,

- Burgess RA ,

- Osborne RH ,

- Yongabi KA ,

- Paltiel AD ,

- Schwartz JL ,

- Walensky RP

- Lhussier M ,

- Williams L ,

- Guthrie B ,

- Pinnock H ,

- ↵ Penney T, Adams J, Briggs A, et al. Evaluation of the impacts on health of the proposed UK industry levy on sugar sweetened beverages: developing a systems map and data platform, and collection of baseline and early impact data. National Institute for Health Research, 2018. https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/164901/#/ .

- Hoddinott P ,

- Britten J ,

- Funnell SC ,

- Lawless A ,

- Delany-Crowe T ,

- Stephens TJ ,

- Pearse RM ,

- EPOCH trial group

- Melendez-Torres GJ ,

- Mounier-Jack S ,

- Hargreaves SC ,

- Manzano A ,

- Uzochukwu B ,

- ↵ White M, Cummins S, Raynor M, et al. Evaluation of the health impacts of the UK Treasury Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL) Project Protocol. NIHR Journals Library, 2018. https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/1613001/#/summary-of-research .

- ↵ National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. What is public involvement in research? – INVOLVE. https://www.invo.org.uk/find-out-more/what-is-public-involvement-in-research-2/ .

- Barrowclough C ,

- Stuckler D ,

- Monteiro C ,

- Lancet NCD Action Group

- Yardley L ,

- Ainsworth B ,

- Arden-Close E ,

- Barnett ML ,

- Ettner SL ,

- Powell BJ ,

- ↵ National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Developing NICE guidelines: the manual. NICE, 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg20/resources/developing-nice-guidelines-the-manual-pdf-72286708700869 .

- Balogun MO ,

- BeST study team

- Escoffery C ,

- Lebow-Skelley E ,

- Haardoerfer R ,

- Stirman SW ,

- Miller CJ ,

- Forsyth R ,

- Purcell C ,

- Hawkins J ,

- Movsisyan A ,

- Rehfuess E ,

- ADAPT Panel ,

- ADAPT Panel comprises of Laura Arnold

- Hawkes RE ,

- Ogilvie D ,

- Eldridge SM ,

- Campbell MJ ,

- PAFS consensus group

- Thabane L ,

- Hopewell S ,

- Lancaster GA ,

- ↵ Craig P, Campbell M. Evaluability Assessment: a systematic approach to deciding whether and how to evaluate programmes and policies. Evaluability Assessment working paper. 2015. http://whatworksscotland.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/WWS-Evaluability-Assessment-Working-paper-final-June-2015.pdf

- Cummins S ,

- ↵ Expected Value of Perfect Information (EVPI). YHEC - York Health Econ. Consort. https://yhec.co.uk/glossary/expected-value-of-perfect-information-evpi/ .

- Cartwright N

- Britton A ,

- McPherson K ,

- Sanderson C ,

- Burnett T ,

- Mozgunov P ,

- Pallmann P ,

- Villar SS ,

- Wheeler GM ,

- Collins LM ,

- Murphy SA ,

- McDonald S ,

- Coronado GD ,

- Schwartz M ,

- Tugwell P ,

- Knottnerus JA ,

- McGowan J ,

- ↵ Egan M, McGill E, Penney T, et al. NIHR SPHR Guidance on Systems Approaches to Local Public Health Evaluation. Part 1: Introducing systems thinking. NIHR School for Public Health Research, 2019. https://sphr.nihr.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/NIHR-SPHR-SYSTEM-GUIDANCE-PART-1-FINAL_SBnavy.pdf .

- Fletcher A ,

- ↵ Bicket M, Christie I, Gilbert N, et al. Magenta Book 2020 Supplementary Guide: Handling Complexity in Policy Evaluation. Lond HM Treas 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/879437/Magenta_Book_supplementary_guide._Handling_Complexity_in_policy_evaluation.pdf

- Pfadenhauer LM ,

- Gerhardus A ,

- Mozygemba K ,

- Curran GM ,

- Mittman B ,

- Landes SJ ,

- McBain SA ,

- ↵ Imison C, Curry N, Holder H, et al. Shifting the balance of care: great expectations. Research report. Nuffield Trust. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/shifting-the-balance-of-care-great-expectations

- Martinez-Alvarez M ,

- Chalmers I ,

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.11(3); 2021

Original research

Evaluating evaluation frameworks: a scoping review of frameworks for assessing health apps, sarah lagan.

Division of DIgital Psychaitry, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Lev Sandler

John torous, associated data.

bmjopen-2020-047001supp001.pdf

bmjopen-2020-047001supp002.pdf

Despite an estimated 300 000 mobile health apps on the market, there remains no consensus around helping patients and clinicians select safe and effective apps. In 2018, our team drew on existing evaluation frameworks to identify salient categories and create a new framework endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). We have since created a more expanded and operational framework Mhealth Index and Navigation Database (MIND) that aligns with the APA categories but includes objective and auditable questions (105). We sought to survey the existing space, conducting a review of all mobile health app evaluation frameworks published since 2018, and demonstrate the comprehensiveness of this new model by comparing it to existing and emerging frameworks.

We conducted a scoping review of mobile health app evaluation frameworks.

Data sources

References were identified through searches of PubMed, EMBASE and PsychINFO with publication date between January 2018 and October 2020.

Eligibility criteria

Papers were selected for inclusion if they meet the predetermined eligibility criteria—presenting an evaluation framework for mobile health apps with patient, clinician or end user-facing questions.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two reviewers screened the literature separately and applied the inclusion criteria. The data extracted from the papers included: author and dates of publication, source affiliation, country of origin, name of framework, study design, description of framework, intended audience/user and framework scoring system. We then compiled a collection of more than 1701 questions across 79 frameworks. We compared and grouped these questions using the MIND framework as a reference. We sought to identify the most common domains of evaluation while assessing the comprehensiveness and flexibility—as well as any potential gaps—of MIND.

New app evaluation frameworks continue to emerge and expand. Since our 2019 review of the app evaluation framework space, more frameworks include questions around privacy (43) and clinical foundation (57), reflecting an increased focus on issues of app security and evidence base. The majority of mapped frameworks overlapped with at least half of the MIND categories. The results of this search have informed a database ( apps.digitalpsych.org ) that users can access today.

As the number of app evaluation frameworks continues to rise, it is becoming difficult for users to select both an appropriate evaluation tool and to find an appropriate health app. This review provides a comparison of what different app evaluation frameworks are offering, where the field is converging and new priorities for improving clinical guidance.

Strengths and limitations of this study

- This scoping review is the largest and most up to date review and comparison of mobile health app evaluation frameworks.

- The analysis highlighted the flexibility and comprehensiveness of the Mhealth Index and Navigation Database (MIND) framework, which was used as a reference framework in this review, in diverse contexts.

- MIND was initially tailored to mental health and thus does not encompass thorough disease-specific criteria for other conditions such as asthma, diabetes and sickle cell anaemia—though such questions may be easily integrated.

- Subjective questions, especially those around ease of use and visual appeal, are difficult to standardise but may be among the most important features driving user engagement with mental health apps.

Introduction

The past 5 years have seen a proliferation of both mobile health apps and proposed tools to rate such apps. While these digital health tools hold great potential, concerns around privacy, efficacy and credibility, coupled with a lack of strict oversight by governing bodies, have highlighted a need for frameworks that can help guide clinicians and consumers to make informed app choices. Although the USs’ Food and Drug Administration has recognised the issue and is piloting a precertification programme that would prioritise app safety at the developer level, 1 this model is still in pilot stages and there has yet to be an international consensus around standards for health apps, resulting in a profusion of proposed frameworks across governments, academic institutions and commercial interests.

In 2018, our team drew on existing evaluation frameworks to identify salient categories from existing rating schemes and create a new framework. 2 The American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) App Evaluation Model was developed by harmonising questions from 45 evaluation frameworks and selecting 38 total questions that mapped to five categories: background information, privacy and security, clinical foundation, ease of use and interoperability. This APA model subsequently has been used by many diverse stakeholders given its flexibility in guiding informed decision-making. 3–7 However, the flexibility of the model also created a demand for a more applied approach that offered users more concrete information instead of placing the onus entirely on a clinician or provider.

Thus, since the framework’s development, the initial 38 questions have been operationalised into 105 new objective questions that invite a binary (yes/no) or numeric response by a rater. 8 These questions align with the categories proposed by the APA model but are more extensive and objective, with, for example, ‘app engagement’ operationalised into 11 different engagement styles to select. These 105 questions are sorted into six categories (App Origin and Functionality, Inputs and Outputs, Privacy and Security, Clinical Foundation, Features and Engagement, Interoperability and Data Sharing) and are intended to be answerable for any trained rater—clinician, peer, end user—and inform the public-facing Mhealth Index and Navigation Database (MIND), where users can view app attributes and compare ratings (see figure 1 below). MIND, thus, constitutes a new framework based on the APA model, with an accompanying public-facing database.

A screenshot of MIND highlighting several of the app evaluation questions (green boxes) and ability to access more. MIND, Mhealth Index and Navigation Database.

Recent systematic reviews have illustrated the growing number of evaluation tools for digital health devices, including mobile health apps. 9–11 Given the rapidly evolving health app space and the need to understand what aspects are considered in evaluation frameworks, we have sought to survey the landscape of existing frameworks. Our goal was to compare the categories and questions composing other frameworks to (1) identify common elements between them, (2) identify if gaps in evaluation frameworks have improved since 2018 and (3) assess how reflective our team’s MIND framework is in the current landscape. We, thus, aimed to map every question from the 2018 review, as well as questions from new app evaluation frameworks that have emerged since, using the questions of MIND as a reference. While informing our own efforts around MIND, the results of this review offer broad relevance across all of digital health, as understanding the current state of app evaluation helps inform how any new app may be assessed, categorised, judged and adopted.

Patient and public involvement

Like the APA model, MIND shifts the app evaluation process away from finding one ‘best’ app, and instead guiding users towards an informed decision based on selecting and placing value on the clinically relevant criteria that account for the needs and preferences of each patient and case. Questions were created with input of clinicians, patients, family members, researchers and policy-makers. The goal is not for a patient of clinician to consider all 105 questions but rather be able to access a subset of questions that appear most appropriate for the current use case at hand. Thus, thanks to its composition of discrete questions that aim to be objective and reproducible, MIND offers a useful tool to compare evaluation frameworks. It also offers an actionable resource for any user anywhere in the world to engage with app evaluation, providing tangible results in the often more theoretical world of app evaluation.

We followed a three-step process in order to identify and compare frameworks to MIND. This process included (1) assembling all existing frameworks for mobile medical applications, (2) separating each framework into the discrete evaluation questions comprising it and (3) mapping all questions to the 105 MIND framework questions as a reference.

Search strategy and selection criteria

We started with the 45 frameworks identified in the 2018 review by Moshi et al 9 and included 34 frameworks that have emerged since our initial analysis of the space that was conducted in 2018 and published in 2019. 2 To accomplish this, we conducted an adapted scoping review based on the Moshi criteria to identify recent frameworks. Although MIND focuses on mental health apps, its considerations and categories are transferable to health apps more broadly, and, thus, there was no mental health specification in the search terms.

References were identified through searches of PubMed, EMBASE and PsychINFO with the search terms ((mobile application) OR (smartphone app)) AND ((framework) OR (criteria) OR (rating)) and publication date between January 2018 and October 2020. We also identified records beyond the database search by seeking frameworks mentioned in subsequent and recent reviews 5 12 13 and surveying the grey literature and government websites. Papers were selected for inclusion if they meet the predetermined eligibility criteria—presenting an evaluation framework for mobile health apps with patient, clinician or end user-facing questions. Two reviewers (SL and JT) screened the literature separately and applied the inclusion criteria. The data extracted from the papers included: author and dates of publication, source affiliation, country of origin, name of framework, study design, description of framework, intended audience/user and framework scoring system. Articles were screened if they describe the evaluation of a single app, did not present a new framework (instead conducting a review of the space or relying on a previous framework), the framework was focused on developer instead of clinicians or end users, was the implementation and not evaluation focused, was not a framework for health apps and was a satisfaction survey instead of an evaluation framework. The data selection process is outlined in figure 2 .

Framework identification through database searches (PubMed, EMBASE, PsychINFO) and other sources (reviews since 2018, grey literature, government websites).

The 34 frameworks identified in the search were combined with the 45 frameworks from the 2018 review for a total of 79 frameworks for consideration. To our knowledge, this list comprehensively reflects the state of the field at the time of assembly. However, we do not claim it to be exhaustive, as frameworks are constantly changing, emerging and sunsetting, with no central repository. The final list of frameworks assembled can be found in online supplemental appendix 1 .

Supplementary data

Each resulting framework was reviewed and compiled into a complete list of its unique questions. The 79 frameworks yielded 1701 questions in total. Several of the original 45 frameworks focused exclusively on in-depth privacy considerations (evaluating privacy and security practices rather than the app itself), 14 and after eliminating these checklists that did not facilitate app evaluation by a clinician or end user, 70 total frameworks were mapped in entirety to the MIND framework.

In mapping questions, discussion was sometimes necessary as not every question was an exact, word-for-word match. The authors, thus, used discretion when it came to matching questions to MIND and discussed each decision to confirm mapping placement. Two raters (SL, LS) agreed on mapping placement, and disputes were brought to a third reviewer (JT) for final consideration. ‘Is data portable and interoperable?’, 15 for example, would be mapped to the question ‘can you email or export your data?’ ‘Connectivity’ 16 was mapped to ‘Does the app work offline?’ and ‘Is the arrangement and size of buttons/content on the screen zoomable if needed’ 17 was mapped to ‘is there at least one accessibility feature?’ Questions about suitability for the ‘target audience’ were mapped to the ‘patient-facing’ question in MIND.

Framework type

The aim of this review was to identify and compare mobile health app rating frameworks, assessing overlap and exploring changes and gaps relative to both previous reviews and to the MIND framework. Of the 70 frameworks ultimately assessed and mapped, the majority 39 (55.7%) offered models for evaluating mobile health apps broadly. Seven (10%) considered mental health apps, while six (8.5%) focused on apps for diabetes management. Other evaluation focuses included apps for asthma, autism, concussions, COVID-19, dermatology, eating disorders, heart failure, HIV, pain management, infertility and sickle cell disease ( table 1 ).

Number of disease-specific and general app evaluation frameworks, with general mobile health frameworks constituting more than half of identified frameworks

We mapped questions from 70 app evaluation frameworks against the six categories and 105 questions of MIND (see online supplemental appendix 2 ). We examined the number of frameworks that addressed each specific MIND category and identified areas of evaluation that are not addressed by MIND. Through the mapping process, we were able to gauge the most common questions and categories across different app evaluation frameworks.

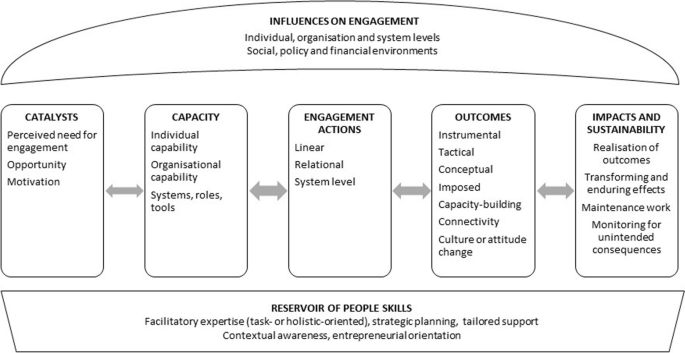

We sorted the questions into MIND’s six different categories—App Origin & Functionality, Inputs & Outputs, Privacy & Security, Evidence & Clinical Foundation, Features & Engagement Style and Interoperability & Data Sharing—in order to assess the most common broad areas of consideration. Across frameworks, the most common considerations were around privacy/security and clinical foundation, with 43 frameworks posing at least one question around the app’s privacy protections and 57 of the frameworks containing at least one question to evaluate evidence base or clinical foundation, as denoted in table 2 . Fifty-nine frameworks covered at least two of the MIND categories, with the majority of frameworks overlapping with at least four of MIND categories.

The questions from all frameworks were mapped to the reference framework (MIND) sorted into its six categories, with this table denoting how many frameworks had questions that could be sorted into each of the categories

MIND, Mhealth Index and Navigation Database.

We then took a more granular look at the questions from each of the 70 frameworks, matching questions one-by-one to questions of the MIND framework when possible. On an individual question level, specific questions about the presence of a privacy policy, security measures in place, supporting studies and patient-facing (or target population) tools were the most prevalent, with representation from 20, 25, 27 and 28 frameworks, respectively, for each question. Each of the 70 frameworks had at least one question that mapped to MIND. The most common questions, sorted into their respective categories, are depicted in figure 3 and table 3 , while the full list of mapped questions can be found in online supplemental appendix 2 .

The most commonly addressed questions, grouped within the categories of MIND. The blue triangle constitutes MIND and its six main categories, while the green trapezoid represents questions pertaining to usability or ease of use, which are not covered by MIND. MIND, Mhealth Index and Navigation Database.

Commonly addressed questions among those that could be mapped to the MIND reference framework (blue), and those that could not (green)

HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; MIND, Mhealth Index and Navigation Database.

Every question was examined but not every question in every framework could be matched to a corresponding question in MIND, and some questions fell outside one of the six categories. For example, 18 frameworks continue to present the subjective question of ‘is the app easy to use’ which will vary depending on the person and use case. MIND also does not offer questions related to other objective questions to which answers are not readily available such as ‘How were target users involved in the initial design and usability evaluations of the app?’ 18 While questions such as this are of high importance, lack of easily accessible answers creates a dilemma in their present utility for app evaluation. Furthermore, some questions such as economic analysis were not covered by MIND but by other frameworks and represent a similar dilemma in that actual data to base evaluation on are often lacking. Aside from subjective questions, other pronounced absences MIND were questions about customisability (addressed by seven other frameworks) and advertising (nine frameworks). Although MIND does ask about customisability in part by encouraging raters to consider accessibility features (and some frameworks ask about the ability to customise in conjunction with accessibility features, 19 MIND neither pose a question around the user’s ability to tailor or customise app content nor does it ask questions about the presence of advertisements on an app. Other questions unaddressed by MIND were about the user’s ability to contact the producer or developer to seek guidance about app use. Variations of this question include ‘is there a way to feedback user comments to the app developer?’ MIND also does not pose any questions regarding instructions in the app or the existence of a user guide. 20 Finally, it does ask about speed of app functionality. This variant of question asks, ‘is the app fast and easy to use in clinical settings?’ 15 figure 3 above, and table 3 below presents additional details on categories and questions both inside and outside the MIND reference framework.

As mobile health apps have proliferated, choosing the right one has become increasingly challenging for patient and clinician alike. While app evaluation frameworks can help sort through the myriad of mobile health apps, the growing number of frameworks further complicates the process of evaluation. Our review examined the largest number of evaluation frameworks to date with the goal of assessing their unique characteristics, gaps as well as overlap with the 105 questions in MIND. We identified frameworks for evaluating a wide range of mobile health apps—some focused on general mobile health, some specific and addressing specific disease domains like asthma, heart failure, mental health or pain management.

Despite the different disease conditions they addressed, there was substantial overlap among the frameworks, especially around clinical foundation and privacy and security. The most common category addressed was clinical foundation, with 57 of the evaluation frameworks posing at least one question regarding evidence base. More than half of the frameworks also addressed privacy and/or security and app functionality or origin.

The widespread focus on clinical foundation and privacy represents a major change in the space since 2018, when our team analysed an initial review of 45 health app evaluation frameworks and found that the most common category of consideration among the different frameworks was usability, with short-term usability highly overrepresented compared with privacy and evidence with base. In this 2018 review, there were 93 unique questions corresponding to short-term usability but only 10 to the presence of a privacy policy. Although many frameworks continue to consider usability, our current review suggests the most common questions across frameworks now concern evidence, clinical foundation and privacy. This shift may reflect an increased recognition of the privacy dangers some apps may pose.

This review illustrates the challenges in conceiving a comprehensive evaluation model. A continued concern in mobile health apps is engagement, 6 and it is unclear whether any framework adequately predicts engagement. Another persistent challenge is striking a balance between transparency/objectivity and subjectivity. Questions that prompt consideration of subjective user experiences may limit the generalisability and standardisation of a framework, as the questions inherently reflect the experience of the rater. An app’s ease of use, for example, will differ significantly depending on an individual’s level of comfort and experience with technology. However, subjective questions around user friendliness, visual appeal and interface design may be of greatest concern to an app user, and most predictive of engagement with an app. 21 Finally, a thorough assessment of an app is only feasible if information about the app is available. For example, some questions with clinical significance, such as the consideration of how peers or target users may be involved in app development, are not easily answerable by a health app consumer. Overall, there is a need for more data and transparency when it comes to health apps. App evaluation frameworks, while thorough, rigorous and tailored to clinical app use, can only go so far without transparency on the part of app developers. 22

The analysis additionally highlighted the flexibility and comprehensiveness of the MIND framework, which was used as a reference framework in this review, in diverse contexts. The MIND categories are inclusive of a wide range of frameworks and questions. Even without including any subjective questions in the mapping process, each of the 70 frameworks that were ultimately mapped had some overlap with MIND, and many of the 1700 questions ultimately included were mapped exactly with a MIND question. Although MIND was initially conceptualised as an evaluation tool specifically for mental health apps, the coherence between MIND and diverse types of app evaluation frameworks, such as those for concussion, 23 heart disease 24 and sickle cell anaemia, 25 demonstrates how the MIND categories can encompass many health domains. Condition-specific questions, for example, are a good fit for the ‘Features & Engagement’ category of MIND.

The results of our analysis suggest while numerous new app evaluation frameworks continue to emerge, there is a naturally appearing standard of common questions asked across all. While different use cases and medical subspecialties will require unique questions to evaluate apps, there are a set of common questions around aspects like privacy and level of evidence that are more universal. MIND appears to cover a large subset of these questions and, thus, may offer a useful starting point for new efforts as well as means to consolidate exiting efforts. Advantage of the more objective approach offered by MIND is that it can be represented as a research database to facilitate discovery of apps while not conflicting with local needs, personal preferences or cultural priorities. 26

Limitations