Argumentative Essay On Democracy Is Better Than Military Rule

The debate between democracy and military rule has long been a topic of contention in discussions about governance. In this essay, we will explore the advantages of democracy over military rule, focusing on representation, human rights, the rule of law, economic development, and peaceful transitions of power. Democracy, with its emphasis on citizen participation and protection of individual rights, has proven to be a better path to progress and prosperity for nations worldwide.

Table of Contents

Reasons Why Democracy Is Better Than Military Rule Essay

Representation and participation.

One of the fundamental pillars of democracy is representation and participation. In democratic societies, citizens have the opportunity to elect their leaders, granting them a voice in shaping policies that impact their lives. Elected representatives, who are accountable to the people, advocate for the interests of their constituents and secure various perspectives, are considered in decision-making processes. In contrast, military rule often leaves citizens without a voice, as a select group makes decisions of military leaders without the consent of the governed.

Protection (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); of Human Rights

Democracies are characterized by a commitment to protecting individual rights and freedoms. Constitutional frameworks and independent judiciary systems in democratic nations ensure that basic human rights, such as freedom of speech, assembly, and expression, are upheld. These rights are essential for fostering an environment of open dialogue, debate, and progress. In contrast, military rule may impose restrictions on civil liberties, leading to censorship and oppression, stifling societal growth and development.

Rule of Law

The rule of law is a cornerstone of democratic governance. In a democracy, laws apply to all citizens equally, regardless of their social or political standing. This principle ensures that those in power are held accountable for their actions, promoting transparency and fairness. In military rule, the rule of law may be undermined, leading to arbitrary decision-making and a lack of checks and balances, which can result in abuse of power.

Economic Development

Empirical evidence suggests that democracies tend to experience higher levels of economic development compared to countries under military rule. The stability and predictability of democratic systems create a favorable environment for investment, innovation, and entrepreneurship. Additionally, democratic governments prioritize policies that foster economic growth, social welfare, and education, leading to better economic outcomes and improved living standards for citizens.

Peaceful Transitions of Power

One of the significant advantages of democracy is its ability to facilitate peaceful transitions of power through regular elections. In democratic nations, leaders are elected for a fixed term, and power is peacefully transferred to the winning candidate after each election cycle. This ensures political stability and reduces the risk of violent conflicts that can arise from power struggles in military regimes.

Challenges and Counterarguments

While democracy offers numerous benefits, it is essential to acknowledge its challenges and consider counterarguments. Democracies can face issues such as political polarization, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and the influence of money in politics. Furthermore, some argue that military rule can bring stability and decisive action in times of crisis. However, it is crucial to recognize that military rule often comes at the cost of human rights and undermines the principles of democratic governance.

In conclusion, democracy has proven to be a superior form of governance when compared to military rule. It ensures representation and citizen participation, protects human rights, upholds the rule of law, fosters economic development, and facilitates peaceful transitions of power. While it may face challenges, democracy remains the best path to progress and prosperity for nations worldwide. Embracing democracy’s core principles of inclusion, transparency, and accountability will continue to lead societies toward a brighter and more equitable future.

Hello! Welcome to my Blog StudyParagraphs.co. My name is Angelina. I am a college professor. I love reading writing for kids students. This blog is full with valuable knowledge for all class students. Thank you for reading my articles.

Related Posts:

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Globally, Broad Support for Representative and Direct Democracy

- 2. Democracy widely supported, little backing for rule by strong leader or military

Table of Contents

- 1. Many unhappy with current political system

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

- Appendix: Political categorization

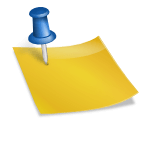

Governance can take many forms: by elected representatives, through direct votes by citizens, by a strong leader, the military or those with particular expertise. Some form of democracy is the public’s preference.

[a representative democracy]

A global median of 78% back government by elected representatives. But the intensity of this support varies significantly between nations. Roughly six-in-ten Ghanaians (62%), 54% of Swedes and 53% of Senegalese and Tanzanians hold the view that representative democracy is very good. Just 8% of Brazilians and 9% of Mexicans agree. The only countries where there is significantly strong opposition to representative democracy are Colombia (24% say it is very bad) and Tunisia (23% very bad).

In many countries, skepticism of representative democracy is tied to negative views about economic conditions. In 19 countries, people who say their national economies are in bad shape are less likely to believe representative democracy is good for the country.

In 23 nations, the belief that representative democracy is good is less common among people who think life is worse today than it was 50 years ago. In Spain, for example, just 63% of those who believe life is worse than before consider representative democracy a good thing for their country, compared with 80% who support representative democracy among those who say life is better than it was a half century ago.

Similarly, pessimism about the next generation is related to negative views about representative democracy. In roughly half the nations surveyed those who think today’s children will be worse off financially than their parents are less likely than others to say representative democracy is a good form of government. Among Mexicans who believe the next generation will be worse off, only 52% say representative democracy is good for the country. Backing for government by elected representatives is at 72% among those who say children will be better off than their parents.

Attitudes toward representative democracy are also associated with opinions about diversity. In more than a third of the nations surveyed those who think that having people of many different backgrounds – such as different ethnic groups, religions and races – makes their country a worse place to live are less likely than others to support government by elected representatives. In South Africa, a country with a troubled history of racial oppression and conflict, 73% of those who embrace diversity describe representative democracy as a good thing for their country; just 54% agree among those who say diversity makes South Africa a worse place to live.

Many publics want a direct say

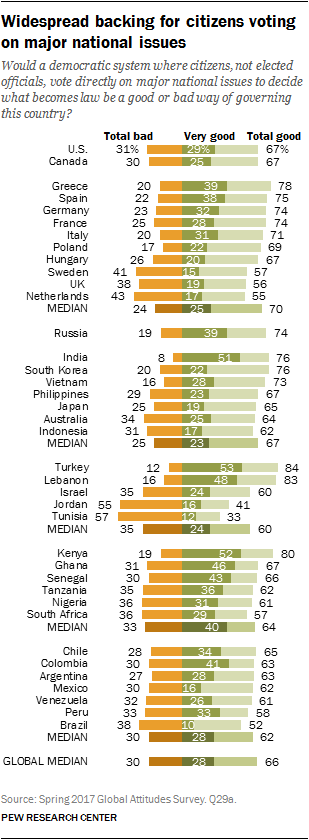

Direct democracy, a governing system where citizens, not elected officials, vote directly on major national issues, is supported by roughly two-thirds of the public around the world, with little difference in views between regions.

The strongest support for governing through referenda is found in Turkey (84%), where 53% of the public say it would be very good to have citizens vote on major national issues. Lebanon (83%) and Kenya (80%) also show broad support for direct democracy.

There is also strong backing for such governance in Japan (65%) even though the country has not had a referendum in the post-World War II era.

In the U.S., Germany and the Netherlands, people with a high school education or less are more likely than those with more than a high school education to support direct democracy. Such differences are small in the U.S. (6 percentage points) and Germany (8 points) but there is a 17-point differential in the Netherlands (62% of those with less educational attainment back direct democracy, but only 45% of those with more education agree).

In six of seven Latin American nations surveyed, those with a secondary school education or above are more supportive of direct democracy than those with less than a high school education. This educational divide is 16 points in Chile and 14 points in Argentina and Colombia. In each of these countries, those with less education are less likely to hold an opinion of direct democracy.

In Latin America, there is also a generation gap in views of direct democracy. In Brazil, Chile, Mexico and Venezuela, those ages 18 to 29 are more supportive than those ages 50 and older of having citizens, not elected officials, vote directly on issues of major national importance.

Notably, in the U.S. it is people ages 30 to 49 who are most likely (73%) to back referenda.

In other countries there are sharp divisions along religious or ethnic lines. In Israel it is Arabs (83%) more than Jews (54%) who favor direct democracy, and in Nigeria it is Muslims (70%) more than Christians (55%).

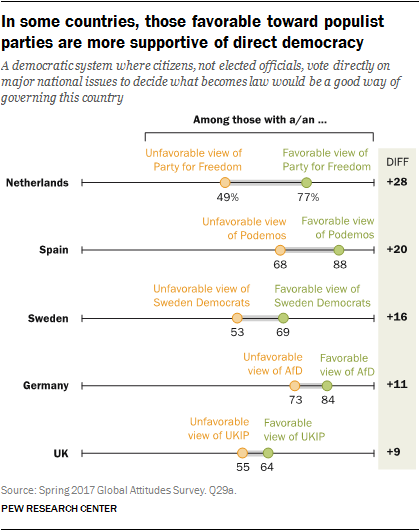

Supporters of some populist parties in Europe are particularly enthusiastic about direct democracy. In Spain, 88% of those who hold a favorable view of Podemos say citizens voting on national issues would be good for the country. In Germany, 84% of AfD backers agree, as do 77% of PVV supporters in the Netherlands.

Support for direct democracy can also be seen in other recent Pew Research Center findings in Europe. In the wake of the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union, a median of just 18% in nine continental EU member states say they want their country to exit the EU. But 53% support holding a national vote on their own country’s EU membership.

And such support is particularly strong among backers of Euroskeptic populist parties, many of whom have promised their supporters a referendum on EU membership. (For more on European’s attitudes about staying in the EU, see Post-Brexit, Europeans More Favorable Toward EU .)

And in six of the nine continental European nations surveyed, strong majorities of those who believe that direct democracy is a very good form of governance support their own EU membership referendum.

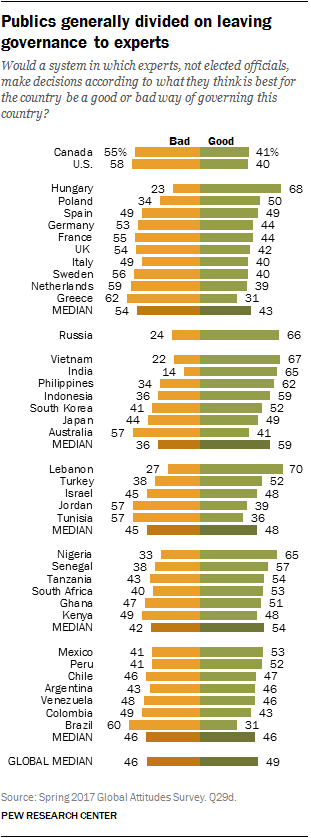

Technocracy has its champions

The value of expert opinion has been questioned in the eyes of the public in recent years. But when asked whether a governing system in which experts, not elected officials, make decisions would be a good or bad approach, publics around the world are divided: 49% say that would be a good idea, 46% think it would be a bad thing.

Europeans (a median of 43%) and Americans (40%) are the least supportive. But among Europeans, roughly two-thirds of Hungarians (68%) say leaving decision-making to experts would be a good way to govern.

Asian-Pacific publics generally back rule by experts, particularly people in Vietnam (67%), India (65%) and the Philippines (62%). Only Australians are notably wary: 57% say it would be a bad way to govern, and only 41% support governance by experts.

More than half of Africans surveyed also say governing by experts would be a good thing for their country. Nigerians (65%) are especially supportive. And it is Nigerian Muslims more than Christians who say this.

Young people in a number of advanced economies are particularly attracted to technocracy. In the U.S. the age gap is 10 percentage points – 46% of those ages 18 to 29 but only 36% of those ages 50 and older say it would be good if experts, not elected officials, made decisions. The young-old differential is even greater in Australia (19 points), Japan (18 points), the UK (14 points), Sweden (13 points) and Canada (13 points).

Some support for rule by strong leader

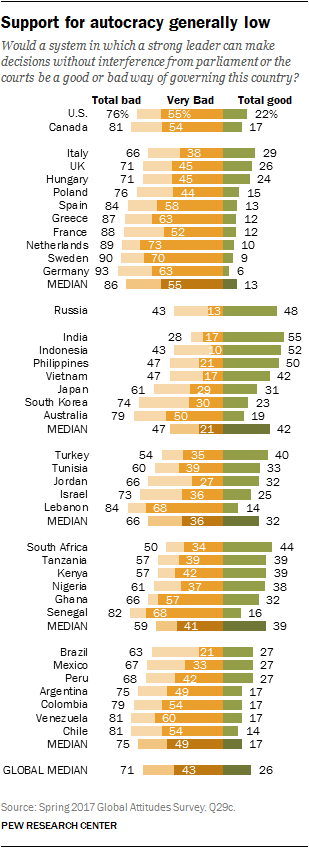

Rule by a strong leader is generally unpopular, though minorities of a substantial size back it. A global median of 26% say a system in which a strong leader can make decisions without interference from parliament or the courts would be a good way of governing. Roughly seven-in-ten (71%) say it would be a bad type of governance.

Opposition is particularly widespread in Europe (a median of 86% oppose rule by a strong leader), with strong opposition in Germany (93%), Sweden (90%) and the Netherlands (89%).

But autocracy is not universally opposed. Roughly four-in-ten Italians (43%) who have a favorable view of Forza Italia, the political party founded by former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, and a similar share of the British (42%) who favor UKIP say a strong leader making decisions would be good for their country. Nearly half of Russians (48%) back governance by a strong leader.

In Asia, 55% of Indians, 52% of Indonesians and 50% of Filipinos favor autocracy. Such support is particularly intense in India, where 27% very strongly back a strong leader.

Public views of rule by a strong leader are relevant in countries that have experienced degrees of authoritarianism in recent years. Roughly eight-in-ten Venezuelans (81%) and 71% of Hungarians oppose a strong leader who makes decisions without interference of parliament or the courts.

Rule by a strong leader also appeals to older members of the public in some countries. More than a quarter of Hungarians (29%) and South Koreans (34%) ages 50 and older favor governance by a strong leader.

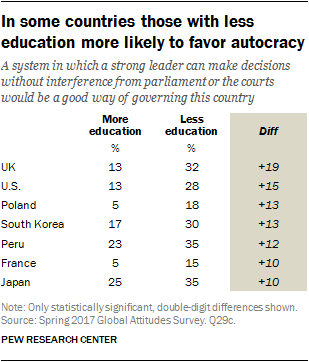

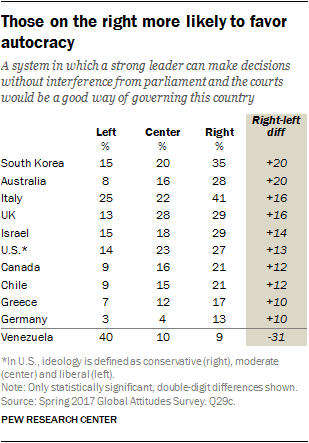

In advanced economies there is little overall backing for autocracy. But, where such support does exist, it is often people with a secondary education or below who are more likely than those with more education to favor autocratic rule. This educational divide is particularly wide in the UK (19 percentage points), the U.S. (15 points), Poland and South Korea (both 13 points).

In a number of nations there is a significant division of opinion about strong leaders based on ideology. Those who place themselves on the right of the ideological spectrum are more likely than those who place themselves on the left to say a strong leader making decisions would be a good way of governing. The ideological gap is 20 percentage points in South Korea and Australia and 16 points in Italy and the UK. Notably, in Venezuela, which has been ruled by populist, left-wing strongmen, those on the left are more supportive of autocratic rule than those on the right.

Significant minorities support military rule

There is minority support for a governing system in which the military rules the country: a median of 24% in the 38 nations surveyed. At least four-in-ten Africans (46%) and Asians (41%) see value in a government run by the generals and admirals.

The strongest backing is in Vietnam (70%), where the army has long played a pivotal role in governance in close collaboration with the Communist Party, especially in the 1960s and 70s during the war with the United States. Some of this may be nostalgia for the past: By two-to-one (46% to 23%) Vietnamese ages 50 and older are more likely than those ages 18 to 29 to say military rule would be very good for their country.

Notably, roughly half of both Indians (53%) and South Africans (52%), who live in nations that often hold themselves up as democratic exemplars for their regions, say military rule would be a good thing for their countries. But in these societies, older people (those ages 50 and older) are the least supportive of the army running the country, and they are the ones who either personally experienced the struggle to establish democratic rule or are the immediate descendants of those democratic pioneers. In South Africa, blacks (55%) more than whites (38%) also favor the military making governance decisions.

Only one-in-ten Europeans back military rule. But some on the populist right of the political spectrum voice such support. Nearly a third of those who hold a favorable view of the National Front in France (31%) say a governing system in which the military rules the country would be a good thing, as do nearly a quarter of those who favor UKIP in the United Kingdom (23%).

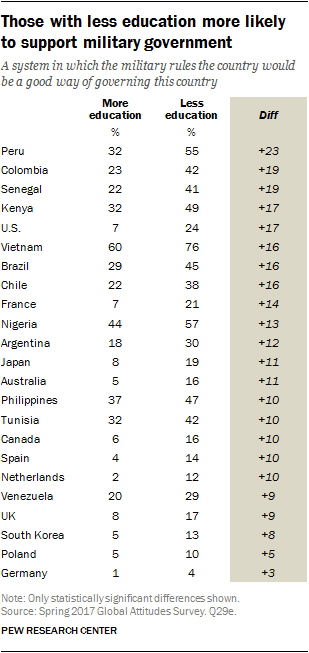

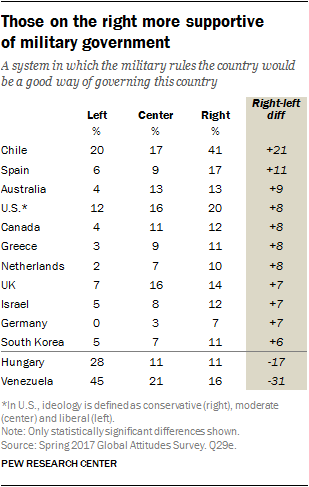

Support for a governing system in which the military rules the country enjoys backing among people with less education in at least half the countries surveyed, with some of the strongest support among those with less than a secondary education in Africa and Latin America.

More than half of Peruvians with less than a high school education (55%) prefer military rule. Only about a third (32%) of more educated Peruvians agree.

Particularly strong backing for military rule also exists among the less educated in Vietnam (76%), Nigeria (57%), Kenya (49%) and the Philippines (47%).

Notably, one-in-five of those ages 50 and older in the U.S. support military rule, as do roughly one-in-four Japanese (24%) ages 18 to 29.

Ideology also plays a role in public views of military rule. But it can cut both ways. In some countries, people on the right of the political spectrum are significantly more supportive of military governance than those on the left, especially in Chile. In Hungary and Venezuela, on the other hand, it is more likely to be individuals on the left who see value in military rule.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Authoritarianism

- Trust in Government

- Trust, Facts & Democracy

Support for democracy is strong in Hong Kong and Taiwan

Who likes authoritarianism, and how do they want to change their government, many across the globe are dissatisfied with how democracy is working, facts on foreign students in the u.s., how countries around the world view democracy, military rule and other political systems, most popular, report materials.

- Explore global opinions on political systems by country

- Spring 2017 Survey Data

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

10 Major Differences Between Military and Democratic Government

- Post author: Edeh Samuel Chukwuemeka ACMC

- Post published: January 23, 2024

- Post category: Scholarly Articles

A democratic government is a clear opposition of military rule or government because, while democracy is aimed at protecting the interest of citizens through popular participation in government, military rule cares less about the interest of the people. For this reason, most countries like Nigeria and Liberia, that have experienced military rule, are saying “NO” to any form of military leadership.

In practice, most countries that claim to be practicing democracy do not really exhibit those essential features of a democratic state. That is why some scholars are of the view that, in most countries, it is nearly impossible to pinpoint the basic tenets of democracy.

Well, in this article, we will be highlighting the core differences between military and democratic government. I therefore enjoin you to read this work till the end so as to enable you understand everything contained in it.

- Major Characteristics of Military Rule

- Problems and criticism of democracy

- Why Indirect rule was adopted in Nigeria? See reason

- Pillars of democracy: 8 Essential pillars of democracy

Table of Contents

What is a democratic government?

In my previous article on the Pillars of Democracy , I explained democracy as a form of government in which the people have the authority to choose their governing legislation. Put in a different way, is it a system of government by the whole population or all the eligible members of a state, typically through elected representatives.

Below is a very short video that explains democracy and it’s features. I enjoin you to watch it before we continue.

What is a military government?

On the other hand, Merriam-Webster dictionary defines a military government as a government established by a military commander in conquered territory to administer the military law declared under military authority applicable to all persons in the conquered territory and superseding any incompatible local law.

Differences Between Military and Democratic Rule or Government

Below are the differences between a military and a democratic government:

1. A democratic government is ruled by civilians, usually elected by the people. On the other hand, military government is ruled by the armed forces, who do not come to power through election, but by force of arms.

2. Democracy is ruled by the constitution and reign of civil laws which are reasonably justifiable in a democratic society with civilian exercising all legislative, executive and judicial powers. Military rule means suspension and modification of the constitution. Imposition of martial law wholesale, partially, or modified, with the military exercising all legislative, executive and sometimes judicial powers as the case may be.

3. Democracy is a product or a process rooted in the tradition of civil liberties, rights and obligations, constitutional and civil behaviors. It is a system that is based on fundamental rights, such as freedom of speech, free debate and opposition, especially by minority political parties in parliament as the case may be.

Military regime is a process, procedure or system with expertise; adapted and rooted in war and combat. It is a system rooted in martial law and forces. It is also a system that demands obedience always and in its purest essence makes no room for debate and opposition.

4. A democratic government is usually transparent, responsible and accountable to the people, who may renew its mandate to rule at election. Military rule is largely not responsible or accountable to the people. The people may however, check it through popular civil action and so forth.

5. Democracy brings to its task the traditions of fundamental rights, legal and constitutional requirements. Military regime uses shortcut and substitutes. It relies on martial law, military tactics and force.

6. Democracy allows for imputs, criticism and the functioning of a free press and free debate among subordinates and the people. A civil administration elicits people and co-operation and it is also adaptable to easy change and modification. Civil administration operates on a voluntary basis and thereby elicits loyalty and devotion, which no military force can instill. Military government operates a chain of command and there is little individual initiative at the bottom. The military operates by order that allows little or no deviation.

7. Democracy is rule by civil made by the elected representatives of the people in parliamentary. Military rule is rule by decrees, edits, Martial law and emergency laws.

8. Democracy allows the assertion of rule of law as guaranteed by the constitution. Military rule is assertion of arbitrary power, restriction of civil liberties. In extreme cases, there may be suspension of habeas corpus and imposition of retrospective laws and stricter penalties.

9. Democracy is slow, and has the appearance of inefficiency. Action is usually voluntary and rooted in dialogue and persuasion; therefore the result achieved are usually more lasting. Military rule operates by threat or application of force which leads to immediate obedience. It has the appearance of efficiency. However, it is a strait jacket of order which can only be obeyed and not debated. Since obedience is by force, the result achieved do not often last long in the absence of continuous monitoring, threat or application of force.

10. The mandate of a constitutional and democratic government to rule and its tenure of office is usually stipulated in the constitution or in a law and its assumption of office or continuation in power is determined by the Electorate through vote during elections.

A military regime does not have a constitutional or legal mandate to rule and its tenure of office is not owed to the people. It either voluntarily determines its own tenure or such tenure is determined by another military take over or, popular civil action by the people.

Yeah! There you have the differences between a military and democratic government. Following the content of this article, it is evident that a civilian or democratic government is far better than a military government since there is always an element of freedom when there is a democratic government.

Using Nigeria for instance, there is no doubt that this country recorded more growth and development in a democratic regime than in the military.

Of course, military rule has advantages in some way. However, if the two governments are placed side-by-side, democracy is apparently better.

- Are lawyers liars? See the truth as to whether lawyers are liars here

- How to answer law problem questions using IRAC method

- Achievements of military rule in Nigeria

This is where is am going to end today. If you have anything to ask or contribute to this article, then you can send it using the comment section. If you think that military government is better than civilian government, i want to here from you. Share your opinion in the comment section below.

Edeh Samuel Chukwuemeka, ACMC, is a lawyer and a certified mediator/conciliator in Nigeria. He is also a developer with knowledge in various programming languages. Samuel is determined to leverage his skills in technology, SEO, and legal practice to revolutionize the legal profession worldwide by creating web and mobile applications that simplify legal research. Sam is also passionate about educating and providing valuable information to people.

This Post Has 4 Comments

Very nice and very good news

I love this thank you for the explanation it’s makes me understand it very well

But a military rule is far better in sense that only in Nigeria that it is seen like this but other countries it’s the same

I really love this, thanks you for the explanation

Comments are closed.

Explore our publications and services.

University of michigan press.

Publishes award-winning books that advance humanities and social science fields, as well as English language teaching and regional resources.

Michigan Publishing Services

Assists the U-M community of faculty, staff, and students in achieving their publishing ambitions.

Deep Blue Repositories

Share and access research data, articles, chapters, dissertations and more produced by the U-M community.

A community-based, open source publishing platform that helps publishers present the full richness of their authors' research outputs in a durable, discoverable, accessible and flexible form. Developed by Michigan Publishing and University of Michigan Library.

- shopping_cart Cart

Browse Our Books

- See All Books

- Distributed Clients

Feature Selections

- New Releases

- Forthcoming

- Bestsellers

- Great Lakes

English Language Teaching

- Companion Websites

- Subject Index

- Resources for Teachers and Students

By Skill Area

- Academic Skills/EAP

- Teacher Training

For Authors

Prospective authors.

- Why Publish with Michigan?

- Open Access

- Our Publishing Program

- Submission Guidelines

Author's Guide

- Introduction

- Final Manuscript Preparation

- Production Process

- Marketing and Sales

- Guidelines for Indexing

For Instructors

- Exam Copies

- Desk Copies

For Librarians and Booksellers

- Our Ebook Collection

- Ordering Information for Booksellers

- Review Copies

Background and Contacts

- About the Press

- Customer Service

- Staff Directory

News and Information

- Conferences and Events

Policies and Requests

- Rights and Permissions

- Accessibility

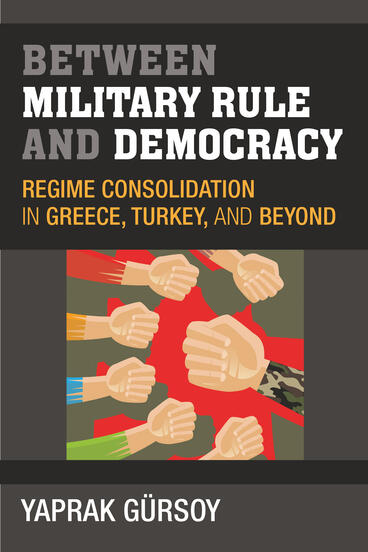

Between Military Rule and Democracy

Regime consolidation in greece, turkey, and beyond.

Examines military interventions in Greece, Turkey, Thailand, and Egypt, and the military’s role in authoritarian and democratic regimes

Look Inside

- Table of Contents

Description

Why do the armed forces sometimes intervene in politics via short-lived coups d’état, at other times establish or support authoritarian regimes, or in some cases come under the democratic control of civilians? To find answers, Yaprak Gürsoy examines four episodes of authoritarianism, six periods of democracy, and ten short-lived coups in Greece and Turkey, and then applies her resultant theory to four more recent military interventions in Thailand and Egypt.

Based on more than 150 interviews with Greek and Turkish elites, Gürsoy offers a detailed analysis of both countries from the interwar period to recent regime crises. She argues that officers, politicians, and businesspeople prefer democracy, authoritarianism, or short-lived coups depending on the degree of threat they perceive to their interests from each other and the lower classes. The power of elites relative to the opposition, determined in part by the coalitions they establish with each other, affects the success of military interventions and the consolidation of regimes.

With historical and theoretical depth, Between Military Rule and Democracy will interest students of regime change and civil-military relations in Greece, Turkey, Thailand, and Egypt, as well as in countries facing similar challenges to democratization.

Yaprak Gürsoy is Lecturer of Politics and International Relations at Aston University.

“ Between Military Rule and Democracy is a pioneering study in the sense that there exists no comparative-historical study of the same level of historical depth and theoretical sophistication which tries to uncover the complex trajectories of democratization and authoritarian reversals in the Southeastern periphery of Europe.” —Ziya Öniş, Koç University

“ Between Military Rule and Democracy goes beyond many of the other treatments of militaries in politics by making a well-supported argument concerning factors that influence the actions of militaries in various situations . . . It thus makes an interesting contribution to the literature on democratization and authoritarianism as well as providing very well-documented case studies of the actions of militaries in two countries where they have played an important role over time.” —Sharon Wolchik, George Washington University

News, Reviews, Interviews

Watch: Yaprak Gursoy book launch with the South East European Studies group at Oxford Link | 5/24/2017 Watch: Interview with Yaprak Gursoy with the South East European Studies group at Oxford Link | 4/19/2017

Supporting ‘democracy’ is hard for many who feel government and the economy are failing them

Associate Professor of Political Science, University of South Carolina

Disclosure statement

Matthew Wilson is affiliated with the Varieties of Democracy Institute ( https://v-dem.net/about/v-dem-institute/scholars-and-staff/ ).

University of South Carolina provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Americans, it seems, can both value the idea of democracy and not support it in practice .

Since 2016, academics and journalists have expressed concerns that formerly secure democracies are becoming less democratic . Different measures of democracy, such as scores produced by the Economist Intelligence Unit , Freedom House and the Varieties of Democracy Institute , have suggested as much based on data over the past decade.

The surveys have sounded alarms about the future of democratic governance in places such as the U.S., which the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance listed as “backsliding” since 2019.

A number of countries that were once considered stable democracies – such as Hungary, India and Nicaragua – have seen their leaders and representatives undermine government institutions in common ways: by encouraging division and polarization , spreading misleading or biased messages , pursuing strategies to unfairly dominate in elections , promoting loyalists and marginalizing opponents , and attacking efforts to hold leaders accountable .

This pattern across democracies raises questions about whether what’s called democratic backsliding is happening globally and which democracies are at risk of failing .

A report released recently by the Pew Research Center that describes the results of public opinion surveys on democracy and political representation in 24 countries, including the U.S., has added to those concerns.

A substantial portion of respondents feel unrepresented by their governments, and 59% are dissatisfied with how their democracy is functioning. Three-quarters of respondents indicate that elected officials do not care what people like them think, and 42% say that no political party in their country represents their views.

In the U.S., Pew reports that 66% are dissatisfied with how democracy is working, 83% feel overlooked by officials, and 49% feel overlooked by political parties. Such pessimistic trends are not new; a Gallup Poll in 2021 and a Pew survey from 2022 both reported that Americans’ trust in government is low.

One of the most unsettling statistics from the recent survey is that 32% of Americans think that “rule by a strong leader or the military would be a good way of governing their country .” This particular finding has been taken as evidence for the idea that a growing number of Americans support replacing democracy with an authoritarian government .

Are Americans losing faith in democracy?

Not quite. Instead, respondents may be losing faith in current institutions’ ability to deliver what they expect out of democracy.

Democracy’s different definitions

Most Americans support democracy as a concept.

Pew found that about 75% of respondents in the U.S. think that representative democracy is a good way of governing . A 2023 study also showed that Americans tend to see themselves as being more committed to democracy, while viewing members of the other party as being more likely to subvert democracy.

But people hold different ideas about what “democracy” is and what it should look like.

When asked to define democracy, those who emphasize electoral and liberal aspects – such as free elections and civil liberties – are more likely to indicate support for democracy . Research shows that commitment to these values is strongly related to democracy support .

In contrast, those who define democracy in terms of its ability to deliver economic security, such as taxing the rich and helping the unemployed, show weaker support for it . This suggests that when people in more democratic countries think that democracy is supposed to alleviate income disparities, they tend to be less satisfied with how democracy is working.

Respondents’ evaluations of whether their country is democratic – or whether democracy is functioning as intended – can therefore be influenced by whether they are economically well off and whether they feel their values are represented in society . Those who are benefiting more from the current political situation are more likely to support it .

Citizens’ desires for a strong leader may largely reflect economic dissatisfaction that overlaps with social and political shifts , such as changes in demographic diversity, family structures and religiousness . Competition with other groups over power and resources presents threats that make people more concerned about their future well-being than about how democracy is functioning.

Many may think that democracy is broken because it neither provides what they expect nor reflects the values they hold. Being laid off and experiencing rising food prices, or disapproving of prevailing positions on socially divisive issues such as abortion, can lead a person to think that supporting mainstream politicians and the usual practice of electing officials is not enough to guarantee that their interests are represented.

Using dissatisfaction to undermine democracy

The Pew survey does not directly indicate that American citizens do not support democracy. But it does reveal an important vulnerability.

The results suggest that a substantial portion of citizens might support a leader working outside of democracy’s institutions – by breaking laws and avoiding accountability for it – because they have lost faith in those institutions’ ability to deliver their version of good governance.

Dissatisfaction with government performance and concerns about socioeconomic well-being can lead citizens to support someone who is willing to flout constitutional rules to restore what they consider to be a broken democracy.

When facing changes that they deem a threat to their economic and social security, voters may gravitate toward someone who can “fix” the problem .

This has the potential to erode the very freedoms that respondents profess to care about. Populist leaders can use dissatisfaction and people’s feelings of being left behind or excluded to build support and justify antidemocratic stances.

Recognizing this is important for understanding how citizens can intrinsically value democracy – and undermine it at the same time . Although people may think they share similar definitions of it, democracy is a complex concept.

Concluding that citizens do not support democracy based on the survey does not address what those citizens think democracy is.

- Public opinion

- Authoritarianism

- Democratic backsliding

- Pew Research Center

- 2024 US presidential election

Scheduling Analyst

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Privacy Overview

Necessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and is used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies. It is mandatory to procure user consent prior to running these cookies on your website.

Global site navigation

- Celebrities

- Celebrity biographies

- Messages - Wishes - Quotes

- TV-shows and movies

- Fashion and style

- Capital Market

- Family and Relationships

Local editions

- Legit Nigeria News

- Legit Hausa News

- Legit Spanish News

- Legit French News

Advantages of democracy over military rule in Nigeria

Eventually, people will always talk about the advantages of democracy over military rule in Nigeria. Those who had an opportunity to compare two rules will vote for democracy and will always appreciate peaceful and stable democracy. We will remind you in this article one more time why the whole country has to work hard to overcome the challenges of Democracy in Nigeria.

What is democracy

Today democracy is considered the best form of government in the world. In a democratic state, people are believed to have power in there hands, and people decide how to rule the country.

The characteristics of democracy are:

- People are the highest form of political power; they have a right to choose and to be chosen.

- Mass media and citizens have a right to express themselves; people can even organize meetings.

- The law protects the rights of the citizens.

- The rule of law prevails.

- The separation of powers into executive, legislature and judicial branches.

- Pure democracy does not exist.

Top 5 causes of the current religious crisis in Nigeria and possible solutions

READ ALSO: What are main features of democracy?

You must be surprised by the last line, but this is indeed the problem of democracy, it does not exist. There are always exceptions that do not permit people to rule the country entirely. At the same time, these restrictions do not let the democracy to become the anarchy. Anyway, to see all advantages of the regime that is supposed to be called “democracy,” we will compare it with the other governing experienced by the Nigerians – military rule.

What is military rule

Military rule - is political regime when the power is concentrated in the hands of the military as an organization. It is believed to be one of the types of the authoritarian regime because at the time of military rule human rights are noticeably limited.

The main features of military rule are:

- The concentration of power in the hands of the military ruler.

- A significant limitation or complete absence of democratic rights and freedoms.

- Willful violation of constitutional proclamation of rights and freedoms in the pretext of restoring and maintaining order in the country.

- The military government can resort to weapons for resolving any conflict. People lose any right to express their opinion and have to suffer under the pressure of armed people.

Causes, positive and negative effects of military rule in Nigeria

However, military rule has positive sights:

- The rulers have no other choice but maintain and sponsor some projects, the civilian government forgets about in peaceful times.

- The military rule includes severe discipline, that factually “destroys” corruption and bureaucracy.

READ ALSO: History of Democracy Day in Nigeria

What are the advantages of democracy over military rule in relation to human rights

We are going to speak about democracy and the army rule in the context of Nigeria because this country experienced both regimes.

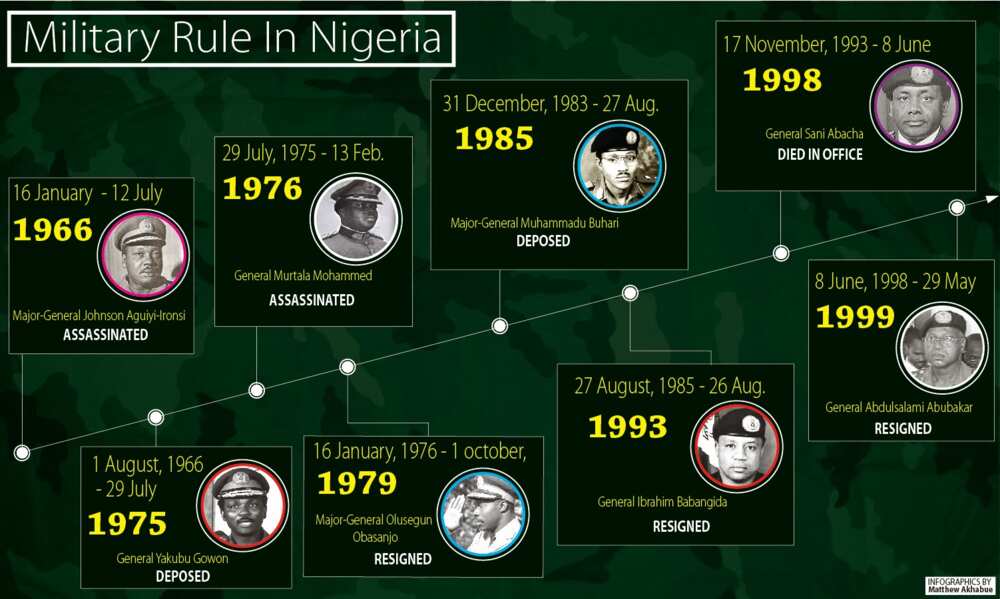

Military rule in Nigeria started for the first time in 1966 – a several years after obtaining the independence. The matter was that Nigeria was in an infantile state, and it was necessary to adjust the governing so that all citizens were satisfied.

There were several coup d’états against the existing government of the grounds of ethnicity, discontentment and many other reasons. It is quite clear that military rule was not the best period in the life of Nigerian people. But citizens of the current time must be able to compare these two forms of ruling to avoid choosing the wrong ways in the future.

Top primary values and principles of constitutional democracy

First of all, it is necessary to highlight the advantages of democracy over military rule in Nigeria concerning human rights.

1. The right to vote

The military rule usually begins with the armed seizure of the governing power.

2. The right to express one’s point of view

Military rule press is characterized by propaganda. All mass media (including radio, television, Internet) work for the government only. People can not organize demonstrations and meetings because they will be punished. During the military rule, many people were tortured because of their opposition to the government. Democracy predisposes the freedom of speech and pluralism of opinions. Meetings organized by people will be taken into account, and people will be listened to because the government depends on people.

3. The right to live

In the period of the military rule in Nigeria, many people were killed and tortured. They were not protected by the law or police. In the democratic conditions, all citizens are supposed to be protected by the law, and all people are supposed to be equal in the court.

How to solve the problem of cultural diversity in Nigeria

READ ALSO: History of democracy in Nigeria from 1960

Advantages of democracy over military rule in general

Other advantages of democracy over military rule in Nigeria include:

- Democracy is the best way to implement the social and political system in a society with constantly changing living conditions without revolutionary explosions and upheavals.

- Democracy is stable. People appreciate peace that is why the regime that presupposes no peace provokes mass dissatisfaction. The problem of Nigerian military rule consists in its durability. It took thirty-three years for the state to become democratic! That is why it is still so difficult to recover from the consequences of revolutions, blood spilling, and instability.

- Democracy promotes the idea of national identity, of national pride, while military rule destroys it. Many people tend to leave the country with military rule.

- Government is stable in a democratic state. Unlike the military rule, you will never wake up and hear the name of a new ruler of the country. Democracy brings stability. At least, in the democratic state, you will go to bed thinking that tomorrow will be a different day!

Advantages and disadvantages of democracy

As it can be seen, military rule is evil, like any other authoritarian rule. This is not just someone’s subjective point of view. Summing up the advantages of democratic rule over military rule is human life which is the most precious thing in the world and any rule that threats or neglects it is considered wrong, dangerous, and must be demolished. Fortunately, it happened in Nigeria, and under no conditions should it (military rule) be repeated.

READ ALSO: Advantages and disadvantages of democracy

Source: Legit.ng

Is Military Rule Better Than The Civilian Rule Or Vice-Versa?

This article examines whether military rule is better than the civilian rule and vice-versa. It provides the advantages of each system of government and gives room for readers to build on any of the points highlighted.

What is a Democratic Government?

Democracy is a form of government in which all eligible citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Democracy allows people to participate equally—either directly or through elected representatives—in the laws’ proposal, development, and creation. i.e., A democratic government is ruled by civilians, usually elected by the people. Democracy is ruled by the constitution and reign of civil laws, which are reasonably justifiable in a democratic society with civilians exercising all legislative, executive, and judicial powers.

A democratic government contrasts two forms of government where power is either held by one, as in a monarchy or where power is held by a small number of individuals, as in an oligarchy or aristocracy. Nevertheless, these oppositions, inherited from Greek philosophy, are now ambiguous because contemporary governments have mixed democratic, oligarchic, and monarchic elements. Several variants of democracy exist, but there are two primary forms that concern how the whole body of citizens executes its will: direct democracy and representative democracy.

Read: Is democracy the best form of government?

What is a Military Government

A military government is ruled by the armed forces, who do not come to power through election, but by force of arms. A military regime is a process, procedure, or system with expertise, adapted and rooted in war and combat. It is a system rooted in martial law and forces. It is also a system that demands obedience always and, in its purest essence, makes no room for debate and opposition.

Some of the features of military rule include Suspension of the constitution, absence of an election, use of decrees and edicts, lack of respect for fundamental human rights, no checks and balances, centralized form of government, no periodic election, etc.

Read: Causes and remedies to indiscipline in schools

Is military rule better than the civilian rule?

Below are the advantages of civilian rule and military rule. This will help you give the essential points to defend the side you want to take, i.e., Military rule is better than a civilian rule, or civilian rule is better than military rule.

Civilian Rule

- There are ways to resolve different views and conflicts peacefully.

- It is a government by the people and for the people

- Respect for human dignity.

- The freedom to act, speak and think freely (as long as it does not stop others from doing the same).

- Equality before the law.

- Safe and secure community.

- It is a system of government that is efficient, transparent, responsive, and accountable to citizens.

- Ability to hold elected representatives accountable.

- Opposition and criticism are tolerated.

Military Rule

- The military has protocol and structure.

- Protection of life and properties is ensured in a military regime.

- Decision-making is faster in military regimes than in civilian.

- It instills discipline and brings about order and corporate living among people in society.

- Control of corruption

- It is cost-effective. Since the election is not conducted, billions spent on this process are avoided.

- There is respect of authority

- Criminal activities are minimal. Martial law can quickly illuminate all criminals.

Military naturally commands respect and fear that is enough to make everyone do what is right while the nation develops with people marginalizing one another.

Related posts:

- Nigerian Military School JS1 Application Form 2024/2025

- Nigerian Military School (NMS) Admission List 2023/2024

- Nigerian Military School (NMS) Zaria School Fees 2023/2024

- Effective teaching as a tool for national development

- IELTS fees, Location, Test dates, And Exam Tips In Nigeria

Bolarinwa Olajire

Leave a reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

The Deep, Tangled Roots of American Illiberalism

By Steven Hahn

Dr. Hahn is a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian at New York University and the author, most recently, of “Illiberal America: a History.”

In a recent interview with Time, Donald Trump promised a second term of authoritarian power grabs, administrative cronyism, mass deportations of the undocumented, harassment of women over abortion, trade wars and vengeance brought upon his rivals and enemies, including President Biden. “If they said that a president doesn’t get immunity,” Mr. Trump told Time, “then Biden, I am sure, will be prosecuted for all of his crimes.”

Further evidence, it seems, of Mr. Trump’s efforts to construct a political world like no other in American history. But how unprecedented is it, really? That Mr. Trump continues to lead in polls should make plain that he and his MAGA movement are more than noxious weeds in otherwise liberal democratic soil.

Many of us have not wanted to see it that way. “This is not who we are as a nation,” one journalist exclaimed in what was a common response to the violence on Jan. 6, “and we must not let ourselves or others believe otherwise.” Mr. Biden has said much the same thing.

While it’s true that Mr. Trump was the first president to lose an election and attempt to stay in power, observers have come to recognize the need for a lengthier view of Trumpism. Even so, they are prone to imagining that there was a time not all that long ago when political “normalcy” prevailed. What they have failed to grasp is that American illiberalism is deeply rooted in our past and fed by practices, relationships and sensibilities that have been close to the surface, even when they haven’t exploded into view.

Illiberalism is generally seen as a backlash against modern liberal and progressive ideas and policies, especially those meant to protect the rights and advance the aspirations of groups long pushed to the margins of American political life. But in the United States, illiberalism is better understood as coherent sets of ideas that are related but also change over time.

This illiberalism celebrates hierarchies of gender, race and nationality; cultural homogeneity; Christian religious faith; the marking of internal as well as external enemies; patriarchal families; heterosexuality; the will of the community over the rule of law; and the use of political violence to achieve or maintain power. This illiberalism sank roots from the time of European settlement and spread out from villages and towns to the highest levels of government. In one form or another, it has shaped much of our history. Illiberalism has frequently been a stalking horse, if not in the winner’s circle. Hardly ever has it been roundly defeated.

A few examples may be illustrative. Although European colonization of North America has often been imagined as a sharp break from the ways of home countries, neo-feudal dreams inspired the making of Euro-American societies from the Carolinas up through the Hudson Valley, based as they were on landed estates and coerced labor, while the Puritan towns of New England, with their own hierarchies, demanded submission to the faith and harshly policed their members and potential intruders alike. The backcountry began to fill up with land-hungry settlers who generally formed ethnicity-based enclaves, eyed outsiders with suspicion and, with rare exceptions, hoped to rid their territory of Native peoples. Most of those who arrived in North America between the early 17th century and the time of the American Revolution were either enslaved or in servitude, and master-servant jurisprudence shaped labor relations well after slavery was abolished, a phenomenon that has been described as “belated feudalism.”

The anti-colonialism of the American Revolution was accompanied not only by warfare against Native peoples and rewards for enslavers, but also by a deeply ingrained anti-Catholicism, and hostility to Catholics remained a potent political force well into the 20th century. Monarchist solutions were bruited about during the writing of the Constitution and the first decade of the American Republic: John Adams thought that the country would move in such a direction and other leaders at the time, including Washington, Madison and Hamilton, wondered privately if a king would be necessary in the event a “republican remedy” failed.

The 1830s, commonly seen as the height of Jacksonian democracy, were racked by violent expulsions of Catholics , Mormons and abolitionists of both races, along with thousands of Native peoples dispossessed of their homelands and sent to “Indian Territory” west of the Mississippi.

The new democratic politics of the time was often marked by Election Day violence after campaigns suffused with military cadences, while elected officials usually required the support of elite patrons to guarantee the bonds they had to post. Even in state legislatures and Congress, weapons could be brandished and duels arranged; “bullies” enforced the wills of their allies.

When enslavers in the Southern states resorted to secession rather than risk their system under a Lincoln administration, they made clear that their Confederacy was built on the cornerstone of slavery and white supremacy. And although their crushing defeat brought abolition, the establishment of birthright citizenship (except for Native peoples), the political exclusion of Confederates, and the extension of voting rights to Black men — the results of one of the world’s great revolutions — it was not long before the revolution went into reverse.

The federal government soon allowed former Confederates and their white supporters to return to power, destroy Black political activism and, accompanied by lynchings (expressing the “will” of white communities), build the edifice of Jim Crow: segregation, political disfranchisement and a harsh labor regime. Already previewed in the pre-Civil War North, Jim Crow received the imprimatur of the Supreme Court and the administration of Woodrow Wilson .

Few Progressives of the early 20th century had much trouble with this. Segregation seemed a modern way to choreograph “race relations,” and disfranchisement resonated with their disenchantment with popular politics, whether it was powered by Black voters in the South or European immigrants in the North. Many Progressives were devotees of eugenics and other forms of social engineering, and they generally favored overseas imperialism; some began to envision the scaffolding of a corporate state — all anticipating the dark turns in Europe over the next decades.

The 1920s, in fact, saw fascist pulses coming from a number of directions in the United States and, as in Europe, targeting political radicals. Benito Mussolini won accolades in many American quarters. The lab where Josef Mengele worked received support from the Rockefeller Foundation. White Protestant fundamentalism reigned in towns and the countryside. And the Immigration Act of 1924 set limits on the number of newcomers, especially those from Southern and Eastern Europe, who were thought to be politically and culturally unassimilable.

Most worrisome, the Ku Klux Klan, energized by anti-Catholicism and antisemitism as well as anti-Black racism, marched brazenly in cities great and small. The Klan became a mass movement and wielded significant political power; it was crucial, for example , to the enforcement of Prohibition. Once the organization unraveled in the late 1920s, many Klansmen and women found their way to new fascist groups and the radical right more generally.

Sidelined by the Great Depression and New Deal, the illiberal right regained traction in the late 1930s, and during the 1950s won grass-roots support through vehement anti-Communism and opposition to the civil rights movement. As early as 1964, in a run for the Democratic presidential nomination, Gov. George Wallace of Alabama began to hone a rhetoric of white grievance and racial hostility that had appeal in the Midwest and Middle Atlantic, and Barry Goldwater’s campaign that year, despite its failure, put winds in the sails of the John Birch Society and Young Americans for Freedom.

Four years later, Wallace mobilized enough support as a third-party candidate to win five states. And in 1972, once again as a Democrat, Wallace racked up primary wins in both the North and the South before an assassination attempt forced him out of the race. Growing backlashes against school desegregation and feminism added further fuel to the fire on the right, paving the way for the conservative ascendancy of the 1980s.

By the early 1990s, the neo-Nazi and Klansman David Duke had won a seat in the Louisiana Legislature and nearly three-fifths of the white vote in campaigns for governor and senator. Pat Buchanan, seeking the Republican presidential nomination in 1992, called for “America First,” the fortification of the border (a “Buchanan fence”), and a culture war for the “soul” of America, while the National Rifle Association became a powerful force on the right and in the Republican Party.

When Mr. Trump questioned Barack Obama’s legitimacy to serve as president, a project that quickly became known as “birtherism,” he made use of a Reconstruction-era racist trope that rejected the legitimacy of Black political rights and power. In so doing, Mr. Trump began to cement a coalition of aggrieved white voters. They were ready to push back against the nation’s growing cultural diversity — embodied by Mr. Obama — and the challenges they saw to traditional hierarchies of family, gender and race. They had much on which to build.

Back in the 1830s, Alexis de Tocqueville, in “Democracy in America,” glimpsed the illiberal currents that already entangled the country’s politics. While he marveled at the “equality of conditions,” the fluidity of social life and the strength of republican institutions, he also worried about the “omnipotence of the majority.”

“What I find most repulsive in America is not the extreme freedom reigning there,” Tocqueville wrote, “but the shortage of guarantees against tyranny.” He pointed to communities “taking justice into their own hands,” and warned that “associations of plain citizens can compose very rich, influential, and powerful bodies, in other words, aristocratic bodies.” Lamenting their intellectual conformity, Tocqueville believed that if Americans ever gave up republican government, “they will pass rapidly on to despotism,” restricting “the sphere of political rights, taking some of them away in order to entrust them to a single man.”

The slide toward despotism that Tocqueville feared may be well underway, whatever the election’s outcome. Even if they try to fool themselves into thinking that Mr. Trump won’t follow through, millions of voters seem ready to entrust their rights to “a single man” who has announced his intent to use autocratic powers for retribution, repression, expulsion and misogyny.

Only by recognizing what we’re up against can we mount an effective campaign to protect our democracy, leaning on the important political struggles — abolitionism, antimonopoly, social democracy, human rights, civil rights, feminism — that have challenged illiberalism in the past and offer the vision and political pathways to guide us in the future.

Our biggest mistake would be to believe that we’re watching an exceptional departure in the country’s history. Because from the first, Mr. Trump has tapped into deep and ever-expanding illiberal roots. Illiberalism’s history is America’s history.

Steven Hahn is a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian at New York University and the author, most recently, of “ Illiberal America: a History .”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , WhatsApp , X and Threads .

The New Propaganda War

Autocrats in China, Russia, and elsewhere are now making common cause with MAGA Republicans to discredit liberalism and freedom around the world.

Listen to this article

Listen to more stories on curio

This article was featured in the One Story to Read Today newsletter. Sign up for it here .

On June 4 , 1989 , the Polish Communist Party held partially free elections, setting in motion a series of events that ultimately removed the Communists from power. Not long afterward, street protests calling for free speech, due process, accountability, and democracy brought about the end of the Communist regimes in East Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Romania. Within a few years, the Soviet Union itself would no longer exist.

Also on June 4, 1989, the Chinese Communist Party ordered the military to remove thousands of students from Tiananmen Square. The students were calling for free speech, due process, accountability, and democracy. Soldiers arrested and killed demonstrators in Beijing and around the country. Later, they systematically tracked down the leaders of the protest movement and forced them to confess and recant. Some spent years in jail. Others managed to elude their pursuers and flee the country forever.

Explore the June 2024 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

In the aftermath of these events, the Chinese concluded that the physical elimination of dissenters was insufficient. To prevent the democratic wave then sweeping across Central Europe from reaching East Asia, the Chinese Communist Party eventually set out to eliminate not just the people but the ideas that had motivated the protests. In the years to come, this would require policing what the Chinese people could see online.

Nobody believed that this would work. In 2000, President Bill Clinton told an audience at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies that it was impossible. “In the knowledge economy,” he said, “economic innovation and political empowerment, whether anyone likes it or not, will inevitably go hand in hand.” The transcript records the audience reactions:

“Now, there’s no question China has been trying to crack down on the internet.” ( Chuckles. ) “Good luck!” ( Laughter. ) “That’s sort of like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall.” ( Laughter. )

While we were still rhapsodizing about the many ways in which the internet could spread democracy, the Chinese were designing what’s become known as the Great Firewall of China . That method of internet management—which is in effect conversation management—contains many different elements, beginning with an elaborate system of blocks and filters that prevent internet users from seeing particular words and phrases. Among them, famously, are Tiananmen , 1989 , and June 4 , but there are many more. In 2000, a directive called “ Measures for Managing Internet Information Services ” prohibited an extraordinarily wide range of content, including anything that “endangers national security, divulges state secrets, subverts the government, undermines national unification,” and “is detrimental to the honor and interests of the state”—anything, in other words, that the authorities didn’t like.

From the May 2022 issue: There is no liberal world order

The Chinese regime also combined online tracking methods with other tools of repression, including security cameras, police inspections, and arrests. In Xinjiang province, where China’s Uyghur Muslim population is concentrated, the state has forced people to install “nanny apps” that can scan phones for forbidden phrases and pick up unusual behavior: Anyone who downloads a virtual private network, anyone who stays offline altogether, and anyone whose home uses too much electricity (which could be evidence of a secret houseguest) can arouse suspicion. Voice-recognition technology and even DNA swabs are used to monitor where Uyghurs walk, drive, and shop. With every new breakthrough, with every AI advance, China has gotten closer to its holy grail: a system that can eliminate not just the words democracy and Tiananmen from the internet, but the thinking that leads people to become democracy activists or attend public protests in real life.

But along the way, the Chinese regime discovered a deeper problem: Surveillance, regardless of sophistication, provides no guarantees. During the coronavirus pandemic, the Chinese government imposed controls more severe than most of its citizens had ever experienced. Millions of people were locked into their homes. Untold numbers entered government quarantine camps. Yet the lockdown also produced the angriest and most energetic Chinese protests in many years. Young people who had never attended a demonstration and had no memory of Tiananmen gathered in the streets of Beijing and Shanghai in the autumn of 2022 to talk about freedom. In Xinjiang, where lockdowns were the longest and harshest, and where repression is most complete, people came out in public and sang the Chinese national anthem , emphasizing one line: “Rise up, those who refuse to be slaves!” Clips of their performance circulated widely, presumably because the spyware and filters didn’t identify the national anthem as dissent.

Even in a state where surveillance is almost total, the experience of tyranny and injustice can radicalize people. Anger at arbitrary power will always lead someone to start thinking about another system, a better way to run society. The strength of these demonstrations, and the broader anger they reflected, was enough to spook the Chinese Communist Party into lifting the quarantine and allowing the virus to spread. The deaths that resulted were preferable to public anger and protest.

Like the demonstrations against President Vladimir Putin in Russia that began in 2011, the 2014 street protests in Venezuela , and the 2019 Hong Kong protests , the 2022 protests in China help explain something else: why autocratic regimes have slowly turned their repressive mechanisms outward, into the democratic world. If people are naturally drawn to the image of human rights, to the language of democracy, to the dream of freedom, then those concepts have to be poisoned. That requires more than surveillance, more than close observation of the population, more than a political system that defends against liberal ideas. It also requires an offensive plan: a narrative that damages both the idea of democracy everywhere in the world and the tools to deliver it.

On February 24, 2022, as Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine, fantastical tales of biological warfare began surging across the internet. Russian officials solemnly declared that secret U.S.-funded biolabs in Ukraine had been conducting experiments with bat viruses and claimed that U.S. officials had confessed to manipulating “dangerous pathogens.” The story was unfounded, not to say ridiculous, and was repeatedly debunked .

Nevertheless, an American Twitter account with links to the QAnon conspiracy network—@WarClandestine—began tweeting about the nonexistent biolabs , racking up thousands of retweets and views. The hashtag #biolab started trending on Twitter and reached more than 9 million views. Even after the account—later revealed to belong to a veteran of the Army National Guard—was suspended, people continued to post screenshots. A version of the story appeared on the Infowars website created by Alex Jones, best known for promoting conspiracy theories about the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School and harassing families of the victims. Tucker Carlson, then still hosting a show on Fox News, played clips of a Russian general and a Chinese spokesperson repeating the biolab fantasy and demanded that the Biden administration “stop lying and [tell] us what’s going on here.”

Chinese state media also leaned hard into the story. A foreign-ministry spokesperson declared that the U.S. controlled 26 biolabs in Ukraine: “Russia has found during its military operations that the U.S. uses these facilities to conduct bio-military plans.” Xinhua, a Chinese state news agency, ran multiple headlines: “U.S.-Led Biolabs Pose Potential Threats to People of Ukraine and Beyond,” “Russia Urges U.S. to Explain Purpose of Biological Labs in Ukraine,” and so on. U.S. diplomats publicly refuted these fabrications. Nevertheless, the Chinese continued to spread them. So did the scores of Asian, African, and Latin American media outlets that have content-sharing agreements with Chinese state media. So did Telesur, the Venezuelan network; Press TV, the Iranian network; and Russia Today, in Spanish and Arabic, as well as on many Russia Today–linked websites around the world.

This joint propaganda effort worked. Globally, it helped undermine the U.S.-led effort to create solidarity with Ukraine and enforce sanctions against Russia. Inside the U.S., it helped undermine the Biden administration’s effort to consolidate American public opinion in support of providing aid to Ukraine. According to one poll, a quarter of Americans believed the biolabs conspiracy theory to be true. After the invasion, Russia and China—with, again, help from Venezuela, Iran, and far-right Europeans and Americans—successfully created an international echo chamber. Anyone inside this echo chamber heard the biolab conspiracy theory many times, from different sources, each one repeating and building on the others to create the impression of veracity. They also heard false descriptions of Ukrainians as Nazis, along with claims that Ukraine is a puppet state run by the CIA, and that NATO started the war.

Outside this echo chamber, few even know it exists. At a dinner in Munich in February 2023, I found myself seated across from a European diplomat who had just returned from Africa. He had met with some students there and had been shocked to discover how little they knew about the war in Ukraine, and how much of what they did know was wrong. They had repeated the Russian claims that the Ukrainians are Nazis, blamed NATO for the invasion, and generally used the same kind of language that can be heard every night on the Russian evening news. The diplomat was mystified. He grasped for explanations: Maybe the legacy of colonialism explained the spread of these conspiracy theories, or Western neglect of the global South, or the long shadow of the Cold War.

But the story of how Africans—as well as Latin Americans, Asians, and indeed many Europeans and Americans—have come to spout Russian propaganda about Ukraine is not primarily a story of European colonial history, Western policy, or the Cold War. Rather, it involves China’s systematic efforts to buy or influence both popular and elite audiences around the world; carefully curated Russian propaganda campaigns, some open, some clandestine, some amplified by the American and European far right; and other autocracies using their own networks to promote the same language.

To be fair to the European diplomat, the convergence of what had been disparate authoritarian influence projects is still new. Russian information-laundering and Chinese propaganda have long had different goals. Chinese propagandists mostly stayed out of the democratic world’s politics, except to promote Chinese achievements, Chinese economic success, and Chinese narratives about Tibet or Hong Kong. Their efforts in Africa and Latin America tended to feature dull, unwatchable announcements of investments and state visits. Russian efforts were more aggressive—sometimes in conjunction with the far right or the far left in the democratic world—and aimed to distort debates and elections in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and elsewhere. Still, they often seemed unfocused, as if computer hackers were throwing spaghetti at the wall, just to see which crazy story might stick. Venezuela and Iran were fringe players, not real sources of influence.

Slowly, though, these autocracies have come together, not around particular stories, but around a set of ideas, or rather in opposition to a set of ideas. Transparency, for example. And rule of law. And democracy. They have heard language about those ideas—which originate in the democratic world—coming from their own dissidents, and have concluded that they are dangerous to their regimes. Their own rhetoric makes this clear. In 2013, as Chinese President Xi Jinping was beginning his rise to power, an internal Chinese memo, known enigmatically as Document No. 9 —or, more formally, as the Communiqué on the Current State of the Ideological Sphere—listed “seven perils” faced by the Chinese Communist Party. “Western constitutional democracy” led the list, followed by “universal human rights,” “media independence,” “judicial independence,” and “civic participation.” The document concluded that “Western forces hostile to China,” together with dissidents inside the country, “are still constantly infiltrating the ideological sphere,” and instructed party leaders to push back against these ideas wherever they found them, especially online, inside China and around the world.

From the December 2021 issue: The bad guys are winning

Since at least 2004, the Russians have been focused on the same convergence of internal and external ideological threats. That was the year Ukrainians staged a popular revolt, known as the Orange Revolution —the name came from the orange T-shirts and flags of the protesters—against a clumsy attempt to steal a presidential election. The angry intervention of the Ukrainian public into what was meant to have been a carefully orchestrated victory for Viktor Yanukovych, a pro-Russian candidate directly supported by Putin himself, profoundly unnerved the Russians. This was especially the case because a similarly unruly protest movement in Georgia had brought a pro-European politician, Mikheil Saakashvili, to power the year before.

Shaken by those two events, Putin put the bogeyman of “color revolution” at the center of Russian propaganda. Civic protest movements are now always described as color revolutions in Russia, and as the work of outsiders. Popular opposition leaders are always said to be puppets of foreign governments. Anti-corruption and prodemocracy slogans are linked to chaos and instability wherever they are used, whether in Tunisia, Syria, or the United States. In 2011, a year of mass protest against a manipulated election in Russia itself, Putin bitterly described the Orange Revolution as a “well-tested scheme for destabilizing society,” and he accused the Russian opposition of “transferring this practice to Russian soil,” where he feared a similar popular uprising intended to remove him from power.