- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Controversial Xu Bing Work Enters the Guggenheim Museum’s Collection

By Barbara Pollack

- March 13, 2018

Call it the Art Boomerang.

On the eve of the opening last October of its major fall exhibition, “Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World,” the Guggenheim Museum pulled three works after an outpouring of protest from animal-rights activists . Now, one of those works, Xu Bing’s “A Case Study of Transference,” is coming back to the museum, this time as a valued part of its permanent collection, purchased with funds provided by an anonymous donor. The website ARTnews first reported the gift .

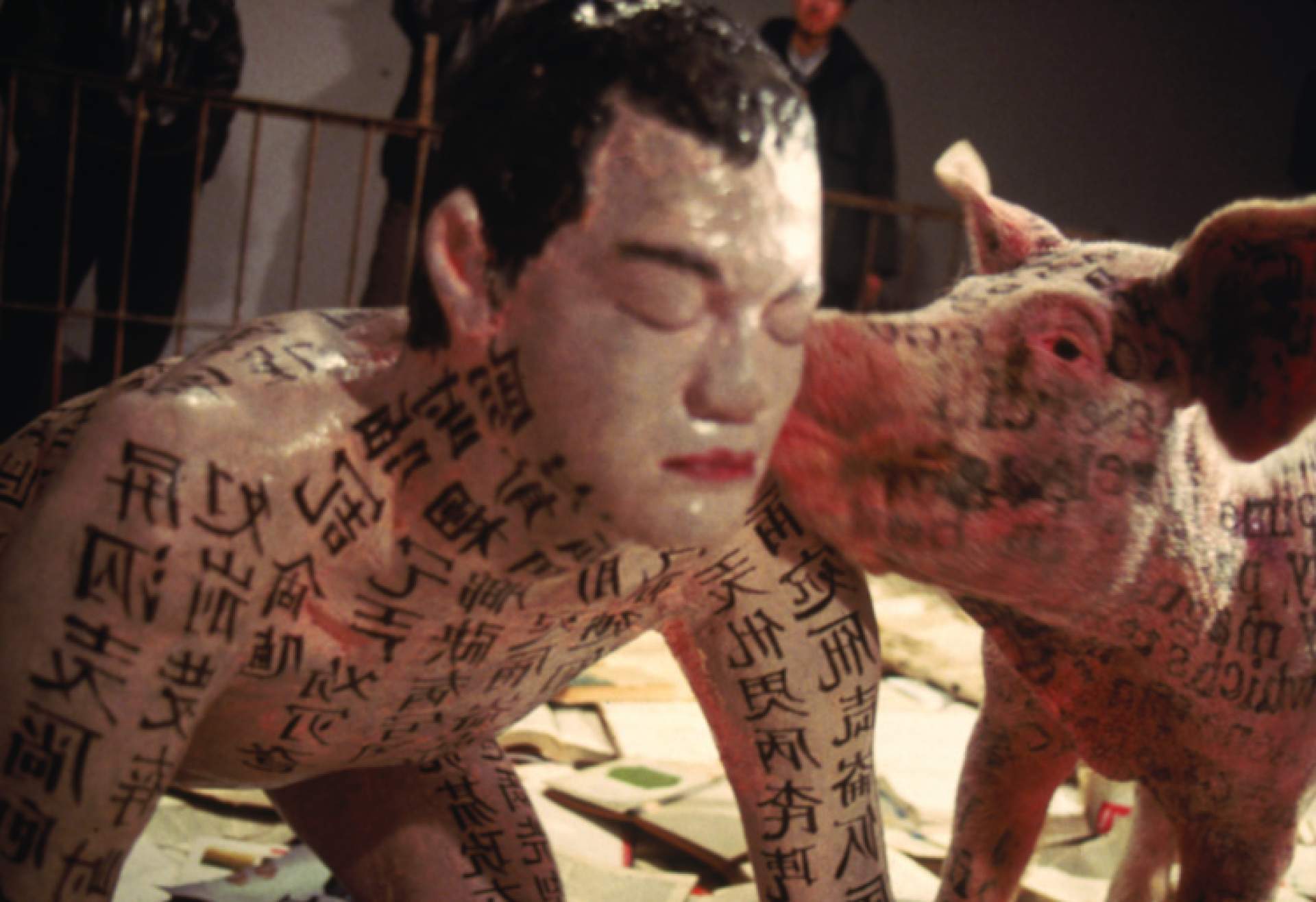

The controversial work is a video documentation of a 1994 performance in which two pigs, one imprinted with nonsensical English words and one stamped with fanciful Chinese characters, copulate before a live audience. It is a satirical take on the collision of East and West.

Instead of showing the video, the museum displayed a blank monitor with a wall label explaining, “For Xu, who, like many intellectuals of his generation, had spent time on a farm during the Cultural Revolution and was familiar with animal husbandry, the performance was a literal and visceral critique of Chinese artists’ desire for enlightenment through Western cultural ‘transference.’”

“Xu Bing’s ‘A Case Study of Transference’ is recognized as an iconic work of conceptual and performance art from China during this period and is now part of the exhibition history,” said Sarah Eaton, a spokeswoman for the Guggenheim, who told The New York Times that the museum might show the work there in the future.

It could also be shown elsewhere sometime soon. “Art and China After 1989” will travel to the Guggenheim Bilbao from May 11 to Sept. 23, 2018, and to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art from Nov. 10, 2018, to Feb. 24, 2019, although neither institution has finalized its checklist yet.

The Guggenheim Abu Dhabi already owns another work that was altered for the exhibition, Huang Yong Ping’s “Theater of the World” (1993), an empty cage that was intended to be filled with live insects, lizards and snakes that would ostensibly feed off each other during the course of the three-month show. In response to the museum’s intervention, the artist scribbled a note of protest in Chinese on an airsickness bag on his flight to New York from Paris where he lives. This work, titled “Vomit Bag” (2017), was displayed in a vitrine at the show and is also under consideration for entering the Guggenheim’s permanent collection.

Art and Museums in New York City

A guide to the shows, exhibitions and artists shaping the city’s cultural landscape..

Uzodinma Iweala, chief executive of The Africa Center , will leave at the end of 2024 after guiding it through the pandemic and securing funds.

Renaissance portraits go undercover in the new Metropolitan Museum show “Hidden Faces,” about the practice of concealing artworks behind sliding panels and reverse-side paintings.

Donna Dennis is a trailblazer of the architectural sculpture movement, and her diaries rival Frida Kahlo’s. Are we ready for the unsettling clarity of the godmother of installation art?

The Rubin will be “reimagined” as a global museum , but our critic says its charismatic presence will be only a troubling memory.

How do you make an artwork sing? Let your unconscious mind do it . That’s the message of an alluring show at the Japan Society.

Looking for more art in the city? Here are the gallery shows not to miss in April .

Sartle requires JavaScript to be enabled in order for you to enjoy its full functionality and user-experience.You can find info on how to enable JavaScript for your browser here .

We do our best to use images that are open source. If you feel we have used an image of yours inappropriately please let us know and we will fix it.

Our writing can be punchy but we do our level best to ensure the material is accurate. If you believe we have made a mistake, please let us know.

If you are planning to see an artwork, please keep in mind that while the art we cover is held in permanent collections, pieces are sometimes removed from display for renovation or traveling exhibitions.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

1071 Fifth Avenue New York, NY United States

More about A Case Study of Transference

Contributor

A Case Study of Transference by Xu Bing might be the most disturbing thing you see today…unless you’re a farmer.

A Case Study of Transference is “a video documentation of a 1994 performance in which two pigs , one imprinted with nonsensical English words and one stamped with fanciful Chinese characters, copulate before a live audience.” The pros of this piece are that 1) it makes for a very thought-provoking work and 2) no one can ever say that Xu Bing lacked originality. Compassion for animals? Maybe. But originality? Never.

The meaning of the work is heavily reliant on the nationality/gender pairings of the pigs. The male pig is printed with English nonsense, while the female pig is printed with Chinese nonsense. The piece “is a satirical take on the collision of East and West.” Literally, by collision they mean sexual intercourse but metaphorically, collision means the sharing of ideas, languages, and cultures. Xu Bing came of age during the Cultural Revolution in China, a time when China was completely closed off to the outside world. Xu spent a significant portion of this time working on a farm in the countryside, hence the pigs. Then he worked for China’s propaganda brigade, making big-character posters, hence the calligraphy on the pigs. And lastly he moved to New York after his work in China began to be censored , hence the connecting of the East and the West via calligraffitied pigs.

This piece was legendary for sure, but not everyone was very excited about it. When the Guggenheim decided to put it in their exhibition titled, Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World along with two other pieces that included the use (or abuse) of animals, PETA flipped. They put together a petition in favor of cruelty free art that got over 820,000 signatures. But this is not what made the Guggenheim decide to pull these artworks from the exhibit. It was threats of violence that put them over the edge. In a statement about the decision the Guggenheim said, “Although these works have been exhibited in museums in Asia, Europe, and the United States, the Guggenheim regrets that explicit and repeated threats of violence have made our decision necessary,” and “as an arts institution committed to presenting a multiplicity of voices, we are dismayed that we must withhold works of art. Freedom of expression has always been and will remain a paramount value of the Guggenheim.” Instead of exhibiting the piece, they displayed a blank TV screen , because DRAMA.

- "Guggenheim Acquiring Controversial Xu Bing Work Pulled From Recent ‘China’ Show -." ARTnews. N.p., 2017. Web. 27 Apr. 2018.

- "Guggenheim Receives Xu Bing Work, Targeted By Animal Rights Activists, From Anonymous Donor." Artforum.com. N.p., 2018. Web. 27 Apr. 2018.

- Intellectual By Nature, Poet At Heart: Xu Bing | Brilliant Ideas Ep. 15. United States: Bloomberg, 2015. video.

- Pollack, Barbara. "Controversial Xu Bing Work Enters The Guggenheim Museum’S Collection." Nytimes.com. N.p., 2018. Web. 25 Apr. 2018.

- Sutton, Benjamin. "Guggenheim Accused Of Supporting Animal Cruelty In New Exhibition." Hyperallergic. N.p., 2017. Web. 27 Apr. 2018.

- Sutton, Benjamin. "Guggenheim Pulls Three Works From Upcoming Show After Outcry Over Animal Abuse [UPDATED]." Hyperallergic. N.p., 2017. Web. 24 Apr. 2018.

- Ask Yale Library

- Terms Governing Use

A Case Study of Transference

Many images in the Arts Library’s Visual Resources Digital Collection are scans from reproductions, used for teaching. When available, information on the original work appears in a Source Note field. Yale Library cannot provide high-resolution files, nor grant permission for use of copyrighted images. 2-1810 [email protected] http://guides.library.yale.edu/images

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Transference and How Does It Work?

Your Therapist Can Experience Transference, Too

Daniel B. Block, MD, is an award-winning, board-certified psychiatrist who operates a private practice in Pennsylvania.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/block-8924ca72ff94426d940e8f7e639e3942.jpg)

Universal Images Group / Getty Images

What Is Transference in Psychotherapy?

Types of transference, counter-transference.

- Transference Examples

- Talking With Your Therapist

Transference-Focused Therapy

Frequently asked questions.

Transference in psychoanalytic theory is when you project feelings about someone else onto your therapist. A classic example of transference is when a client falls in love with their therapist. However, one might also transfer feelings of rage, anger, distrust, or dependence.

While transference is typically a term for the mental health field, it can manifest in daily life when the brain tries to comprehend a current experience by examining the present through the past. Here we explore the definition of transference in greater detail and the different types.

At a Glance

Transference happens when your feelings for someone else are projected onto your therapist. It's a key part of psychodynamic therapies, and it's something your therapist will likely want to explore to understand your interactions and relationship patterns better. It can also go the other direction; your therapist might experience counter-transference, where they project their feelings for someone else onto you. In either case, it's crucial to understand how it works and how it might affect the therapeutic process—especially if there's a risk that it might hurt the therapeutic relationship.

Transference, in general, is "the process of moving something or someone from one place, position, etc. to another." However, the psychology-based definition of transference is a bit different and applies directly to those engaged in mental health therapy.

In this context, transference is defined as a projection of one's unconscious feelings onto their therapist. The American Psychological Association explains that these feelings are ones that were originally directed toward important figures in the person's childhood, such as their parents.

The concept of transference in therapy came about later in the 20th century, when therapeutic approaches became less strict, giving practitioners more flexibility in how they treated their patients.

Transference is a complex phenomenon and can sometimes be an obstacle to therapy. Based on their feelings, the client may feel tempted to cut off the relationship with their therapist altogether, for instance. Or they might become sullen and withdrawn during therapy sessions, impeding their progress.

Working through transferred feelings is an important part of psychodynamic therapy . The nature of the transference can provide important clues to the client’s issues, while working through the situation can help resolve deep-rooted conflicts in their psyche.

There are three types of transference in therapy:

- Positive transference

- Negative transference

- Sexualized transference

Positive Transference

Transference can sometimes be a good thing. An example of positive transference is when you apply enjoyable aspects of your past relationships to the relationship with your therapist. This can have a positive outcome because you see your therapist as caring, wise, and concerned about you.

The benefits of positive transference can be seen in a case study involving a child with autism . Once positive transference started to occur, the young boy's bond with the therapist started to strengthen and he began following the therapist's directions, reduced his aggressive behaviors, and his learning abilities developed.

Negative Transference

Negative transference involves the transfer of negative emotions to the therapist. Anger and hostility are two emotions that might have been felt in childhood, either toward a parent or other important individual, then reappearing in the therapeutic relationship .

Negative transference sounds bad but actually can enhance the therapeutic experience. Once realized, the therapist is able to use this transference as a topic of discussion, further examining the client's emotional response.

Negative transference can be especially useful if the therapist helps you overcome an emotional response that is out of proportion to what transpired during the therapy session.

Sexualized Transference

Do you feel attracted to your therapist ? If so, you might be experiencing sexualized transference, also sometimes referred to as erotic transference. Feelings that fall under sexualized transference include those that are:

- Intimate and sexual

- Reverential or feelings of worship

- Romantic and sensual

Some research suggests that sexualized transference may be more common for members of the LGBTQ+ community , especially if the person has few friends or others they can trust or confide in.

Mental health therapists must also be aware of the possibility that their own feelings and internal conflicts could be transferred to the client as well. This process is known as counter-transference and can muddy the therapeutic relationship.

An estimated 78% of therapists have felt sexual feelings toward a client at one time or another, with male therapists experiencing these intimate feelings more often than female therapists.

Despite the negative connotation of counter-transference, some psychotherapists use it in therapeutic ways. The therapist may choose to disclose their feelings if a client mentions that they seem angry, for instance, first crediting the client with recognizing this emotion and then working together to understand how much of the response may have been projected by the client.

Examples of Transference in Therapy

What does transference look like in a therapeutic setting? Here are a few examples to consider.

Example of Positive Transference

Tony's mother was always loving and supportive. Tony has a female therapist and projects these same feelings on her, considering her as a loving, supportive individual as well.

Example of Negative Transference

Michelle became very angry with her therapist when he discussed the possibility of homework activities. Through the exploration of her anger with the therapist, Michelle discovered that she was experiencing transference of unresolved anger toward an authoritarian elementary school teacher.

Example of Sexualized Transference

As therapy progresses, Chris develops sexual feelings toward the therapist. Chris has even had erotic fantasies involving the therapist, sometimes also saying flirtatious things during the therapy session.

Discussing Transference With Your Therapist

Hill Street Studios / Getty Images

If your therapist recognizes that you are experiencing transference, they may not want to discuss it right away. It will, however, be necessary to address the transference at some point because if the topic is avoided, it could lead to an impasse in therapy and negatively impact your relationship with your therapist .

Additional consequences of avoiding transference are that you, the client, may:

- Become embarrassed, uncomfortable, and withdraw from therapy emotionally

- Experience higher levels of stress during therapy sessions due to how you feel

- Regress, which can negate some of the positive progress you already achieved

Talking about the transference when both you and the therapist are ready can help resolve these issues, enhancing the therapeutic process.

Transference-focused therapy is a type of therapy used to treat borderline personality disorder (BPD) . BPD is a personality disorder characterized by unstable emotions, moods, behaviors, and relationships.

Transference-focused therapy utilizes the therapeutic relationship to help people relate better to others. Transference allows the therapist to see how someone with BPD relates to others and then use this information to help the person build healthier relationships .

Once a therapist and client establish a trusting therapeutic relationship, they work to explore behavior patterns, thoughts, and emotions to better understand how the individual responds and copes. As people become more aware of these destructive patterns, they can work to build more effective skills and interactions.

Therapists also utilize transference in other types of psychotherapy . For example, transference is a key component of psychodynamic therapy, but it can also incorporated in other approaches, including relational therapy , integrative therapy , and eclectic therapy .

Transference is when a client projects feelings on the therapist, while counter-transference is when a therapist projects feelings on the client.

Counter-transference can make it harder for a therapist to be objective during the therapeutic process. It may even skew the therapy in the wrong direction as actions taken during the sessions could be based more on the therapist's feelings than on the feelings of the patient. Additionally, patients may not be able to resolve their issues if they are confused by the emotional response of the therapist.

Some researchers suggest that transference in therapy may be a defense mechanism , such as when the patient is insincere or not ready to face negative emotions. Others contend that whether transference is considered a defense mechanism varies depending on the therapist's interpretation.

If a client is feeling especially vulnerable, such as when dealing with a life-threatening disease that threatens their self-esteem and self-control, it may increase their risk of transference. Additionally, transference may be more common when therapy is conducted in person as opposed to therapy that occurs online .

Cambridge Dictionary. Transference .

American Psychological Association. Transference .

Parth K, Datz F, Seidman C, Löffler-Stastka H. Transference and counter-transference: A review . Bulletin Menninger Clinic . 2017;81(2):167-211. doi:10.1521/bumc.2017;81.2.167

Andersen SM, Przybylinski E. Experiments on transference in interpersonal relations: implications for treatment . Psychotherapy . 2012;49(3):370-83. doi:10.1037/a0029116

Gimenes Rodrigues A, Fiamenghi-Jr GA. Autism and transference: Case study in a Brazilian primary school . EAS J Psychol Behav Sci . 2019;1(5):84-89. doi:10.36349/EASJPBS.2019.v01i05.002

American Psychological Association. Negative transference .

Dharani Devi K, Manjula M, Bada Math S. Erotic transference in therapy with a lesbian client . Ann Psychiatry Mental Health . 2015;3(3):1029.

Dahl HSJ, Hoglend P, Ulberg R, et al. Does therapists' disengaged feelings influence the effect of transference work? A study on countertransference . Clin Psychol Psychother . 2017;24(2):462-474. doi:10.1002/cpp.2015

Capawana MR. Intimate attractions and sexual misconduct in the therapeutic relationship: Implications for socially just practice . Cogent Psychol . 2016;3(1):1194176. doi:10.1080/23311908.2016.1194176

Gabbard G. The role of countertransference in contemporary psychiatric treatment . World Psychiatry . 2020;19(2):243-244. doi:10.1002/wps.20746

Clarkin JF, Caligor E, Sowislo J. TFP extended: development and recent advances . Psychodyn Psychiatry . 2021 Summer;49(2):188-214. doi:10.1521/pdps.2021.49.2.188

Locati F, De Carli P, Tarasconi E, Lang M, Parolin L. Beyond the mask of deference: Exploring the relationship between ruptures and transference in a single-case study . Res Psychotherapy Psychopathol Process Outcome . 2016;19(2). doi:10.4081/ripppo.2016.212

Bhatia M, Petraglia J, de Roten Y, Banon E, Despland JN, Drapeau M. What defense mechanisms do therapists interpret in-session? . Psychodynamic Psychiatry . 2016;44(4):567-585. doi:10.1521/pdps.2016.44.4.567

Noorani F, Dyer AR. How should clinicians respond to transference reactions with cancer patients? . AMA Journal of Ethics .

Sayers J. Online psychotherapy: Transference and countertransference issues . Br J Psychotherapy . 2021;37(2):223-233. doi:10.1111/bjp.12624

By Lisa Fritscher Lisa Fritscher is a freelance writer and editor with a deep interest in phobias and other mental health topics.

A Case Study of Transference

2005 Inkjet print 160 x 14 inches (detail)

Transference vs Countertransference in Therapy: 6 Examples

In reality, transference occurs within the context of relationships and represents a complex interplay of emotions, memories, and subconscious actions.

While transference is a phenomenon seen in daily life, relationships, and interactions, we will take a closer look at how it affects professional settings and examine practical ways to make it a beneficial aspect of therapy.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Relationships Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients build healthy, life-enriching relationships.

This Article Contains:

What are transference & countertransference, 6 real-life examples, psychology theories behind the concepts, 4 signs to look for in your sessions, 5 ways to manage it in therapy, is countertransference bad ethical considerations, 2 helpful worksheets for therapists and clients, positivepsychology.com’s relevant resources, a take-home message.

Freud and Breuer (1895) originally identified and discussed transference and countertransference within a therapeutic context. These concepts were an important part of psychoanalytic treatment but have since been adopted by most forms of psychotherapy.

These concepts occur within any relationship, and the therapeutic relationship is no exception.

So what exactly are transference and countertransference?

Transference

Transference in therapy is the act of the client unknowingly transferring feelings about someone from their past onto the therapist. Freud and Breuer (1895) described transference as the deep, intense, and unconscious feelings that develop in therapeutic relationships with patients. They analyzed transference in order to account for distortions in a client’s perceptions of reality.

While Freud viewed transference as pathological, repetitive, and unreflective of the present relationship between the client and therapist (Wachtel, 2008), modern psychology has rebuffed this assessment.

Many psychological approaches recognize that the responses of a therapist can evoke reactions in the client, and the process of the interaction can be beneficial or harmful to therapy (Fuertes, Gelso, Owen, & Cheng, 2013).

Transference is multilayered and complex and happens when the brain tries to understand a current experience by examining it through the past (Makari, 1994).

There are three main categories of transference.

- Positive transference is when enjoyable aspects of past relationships are projected onto the therapist. This can allow the client to see the therapist as caring, wise, and empathetic, which is beneficial for the therapeutic process.

- Negative transference occurs when negative or hostile feelings are projected onto the therapist. While it sounds detrimental, if the therapist recognizes and acknowledges this, it can become an important topic of discussion and allow the client to examine emotional responses.

- Sexualized transference is when a client feels attracted to their therapist. This can include feelings of intimacy, sexual attraction, reverence, or romantic or sensual emotions.

A therapist can gain insight into a client’s thought patterns and behavior through transference if they can identify when it is happening and understand where it is coming from. Transference usually happens because of behavioral patterns created within a childhood relationship.

Types of transference include:

- Paternal transference Seeing the therapist as a father figure who is powerful, wise, authoritative, and protecting. This may evoke feelings of admiration or agitation, depending on the relationship the client had with their father.

- Maternal transference Associating the therapist with a mother figure who is seen as loving, influential, nurturing, or comforting. This type of transference can generate trust or negative feelings, depending on the relationship the client had with their mother.

- Sibling transference Can reflect dynamics of a sibling relationship and often occurs when a parental relationship is lacking.

- Non-familial transference Happens when clients idealize the therapist and reflect stereotypes that are influencing the client. For example, a priest is seen as holy, and a doctor is expected to cure and heal ailments.

- Sexualized transference Occurs when a person in therapy has a sexual attraction to their therapist. Eroticized transference is an all-consuming attraction toward the therapist and can be detrimental to the therapeutic alliance and client’s progress.

Countertransference

Countertransference has been viewed as the therapist’s reaction to projections of the client onto the therapist. It has been defined as the redirection of a therapist’s feelings toward a patient and the emotional entanglement that can occur with a patient (Fink, 2011).

While Freud viewed countertransference as dangerous because a psychoanalyst is supposed to remain completely objective and detached, those views have since been challenged (Boyer, 1982).

Racker (1988) built the idea that the therapist’s feelings have significance and can lead to important content to be worked through with the client. His definition of countertransference is “that which arises out of the analyst’s identification of himself with the (clients) internal objects” (Racker, 1988, p. 137).

When these reactions surface, they can be dealt with and lead to a healthy therapeutic relationship .

Below is a selection of examples from real life, and a few excellent videos to illustrate both transference and counter transference.

1. I have a crush on my therapist

This video provides a good description of erotic or sexual transference. This is the most dangerous form of transference and has the potential to harm the therapeutic alliance and process.

2. The Sopranos

The famous TV series The Sopranos provides us with a dramatic example of sexualized transference that would break all ethical codes of conduct for a therapy session.

3. Example of negative transference

Amanda (a 32-year-old woman) becomes furious with her therapist when he discusses assigning homework activities. She sighs loudly and states, “This is NOT what I came to therapy for. Homework? I am not in elementary school anymore!”

The therapist remains calm and states, “It sounds like you are upset about homework assignments. Tell me what you are experiencing right now.”

After exploring the emotions that surfaced, Amanda and her therapist come to realize that she was experiencing unresolved anger toward a verbally abusive authoritarian elementary school teacher.

4. Role-play

This video was created by a therapist to demonstrate several types of transference and countertransference. The therapist plays both roles (clinician and therapist) to act out/role-play examples of how transference can transpire in a session.

5. She’s Funny That Way

In this comical clip of famous actress Jennifer Aniston pretending to be a therapist, we can see exaggerated examples of countertransference. In this case, there are no professional boundaries, ethics, or appropriate therapeutic practices taking place.

6. School counseling

Countertransference is particularly hard in school counseling settings.

According to American Counseling Association (ACA) member Matthew Armes, a high school counselor in Martinsburg, West Virginia, “all counselors went to school and have associated memories.” Armes goes on to say that “working with students who are dealing with their parents’ expectations and relationship struggles can trigger countertransference for him because his parents were divorcing just as he was starting high school” (Notaras, 2013).

Armes initially rejected his father during the divorce but eventually repaired the relationship. He states that because so many students experience divorce, it is an issue he strongly empathizes with. It is important to set strong boundaries around this connection and empathy to effectively “let [students] know [they are] not alone and that there are ways to become a stronger person.”

Download 3 Free Positive Relationships Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients to build healthy, life-enriching relationships.

Download 3 Positive Relationships Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Are there theories to explain these specific examples of transference? Transference and countertransference are rooted in psychodynamic theory but can also be supported by social-cognitive and attachment theories .

These theories have different approaches to examine how maladaptive behaviors develop subconsciously and outside of our control.

Psychoanalytic theory

In psychoanalytic theory, transference occurs through a projection of feelings from the client onto the therapist, which allows the therapist to analyze the client (Freud & Breuer, 1895).

This theory sees human functioning as an interaction of drives and forces within a person and the unconscious structures of personality.

Within psychoanalytic theory, defense mechanisms are behaviors that create “safe” distance between individuals and unpleasant events, actions, thoughts, or feelings (Horacio, 2005).

Psychoanalytic theory posits that transference is a therapeutic tool critical to understanding an individual’s repressed, projected, or displaced feelings (Horacio, 2005). Healing can occur once the underlying issues are effectively exposed and addressed.

Social-cognitive perspective

Carl Jung (1946, p. 185), a humanistic psychologist, stated that within the transference dyad, both participants experience a variety of opposites:

“In love and in psychological growth, the key to success is the ability to endure the tension of the opposites without abandoning the process, and that this tension allows one to grow and transform.”

This dynamic can be seen in the modern social-cognitive perspective, which explains how transference can occur in daily life. When individuals meet a new person who reminds them of someone from their past, they subconsciously assume that the new person has similar traits and characteristics.

The individual will treat and react to the new person with the same behaviors and tendencies they did with the original person, transferring old patterns of behavior onto a new situation.

Attachment theory

Attachment theory is another theory that can help explain transference and countertransference. Attachment is the deep and enduring emotional bond between two people .

It is characterized by specific childhood behaviors such seeking proximity to an attachment figure when upset or threatened, and is developed in the first few years of life (Bowlby, 1969). If a child develops an unhealthy attachment style , they may later project their insecurities, anxiety, and avoidance onto the therapist.

The key to ensuring that transference remains an effective tool for therapy is for the therapist to be aware of when it is happening.

1. Unnecessarily strong (or inappropriate) emotions

When clients lash out with anger or distress in a way that seems excessive for the topic that is being discussed, it is a clear sign that transference may be taking place.

Clients may even demonstrate inappropriate laughter surrounding issues that are not funny, which can be a signal for the therapist to intervene (Lambert, Hansen, & Finch, 2001).

The therapist can address the strong or inappropriate emotions and get at core issues.

2. Emotions directed at the therapist

An obvious sign of transference is when a client directs emotions at the therapist. For example, if a client cries and accuses the therapist of hurting their feelings for asking a probing question, it may be a sign that a parent hurt the client regarding a similar question/topic in the past.

3. Unreasonable dislike for the client

Therapists also need to be aware of countertransference, when they are projecting feelings onto a client. One of the most common signs of countertransference is disliking a client for no apparent or obvious reason (Lambert et al., 2001).

This is a good opportunity for the therapist to examine personal values, beliefs, and emotions surrounding the characteristics of the client and past relationships.

4. Becoming overly emotional or preoccupied with a client

Another red flag for countertransference is if a therapist notices that thoughts and feelings for clients are taking up a significant amount of time outside of sessions.

It is natural for therapists to think of their clients outside the therapy room, but when they are joined with strong emotions or become intrusive or obsessive thoughts , the therapist may have to refer the client to another practitioner.

Psychological, spiritual, and emotional issues can trigger the most educated and experienced therapists within the therapeutic dynamic.

Some ways to manage transference and countertransference in therapy include the following.

1. Peer support

Consult a colleague, supervisor, or clinical director when feeling an emotional trigger or response. When a session is especially challenging, it can cause a therapist to sacrifice empathy and objectivity.

Regular peer support and clinical therapy meetings can be helpful. Brickel and Associates has more information on options for finding online peer support.

2. Continual self-reflection

Explore feelings toward individual clients, and write down ways you are consciously or unconsciously reacting to them in session.

Our introspection and self-reflection article outlines practical ways to explore self-reflection.

3. Clear boundaries

Set appropriate boundaries regarding scheduling, payment, and acceptable in-session behavior. Discuss any misunderstandings of intent and emotional projection as soon as it occurs.

4. Mindfulness

Practice mindfulness inside and outside of sessions to explore personal thoughts and feelings.

Gain insight into compassion fatigue, burnout , excessive stress, or an inability to do quality clinical work. Observe the space between stimulus and response, and make appropriate thoughtful reactions.

Lichtenberg, Bornstein, and Silver (1984) formulated that empathy is the foundation of human intersubjectivity, and that failing to demonstrate it is the largest impediment to treatment.

Lack of empathy can be a precursor to countertransference. When we employ empathy as practitioners, we are looking at the situation and client outside of our own view, making countertransference less likely.

The Social Work Dictionary defines “countertransference” as a set of conscious or unconscious emotional reactions to a client experienced by a social worker or professional, and has established specific ethical issues to consider in practice (Barker, 2014).

Just like transference, countertransference is not always bad and can be an effective tool in therapy if used properly. The ethical considerations set forth by the ACA and the Newfoundland and Labrador Association of Social Workers (2018) include:

- Professional boundaries When experiencing countertransference, it is important to consider how professional boundaries can be impacted. Professionals need to ensure that the relationship always serves the needs of the client first.

- Conflicts of interest Countertransference may create a conflict of interest that impedes the professional’s ability to remain unbiased or objective. Practitioners can get wrapped up in their own emotional and personal issues, which interferes with the ability to provide effective treatment and impartial judgement.

- Self-disclosure When considering self-disclosure, a professional must examine the benefits/risks and ask whose needs are being met. It is also important to think about whether the client is experiencing transference and how this influences the therapeutic relationship.

- Competence in practice Professionals in the field of mental health should offer the highest quality service possible, and the therapeutic relationship must be terminated if countertransference affects the ability to practice competently.

Having shared experiences with a client can enhance empathy, but therapists and those in the mental health field must work through ethical considerations to inform decision making.

Self-reflection and self-awareness are some of the most powerful tools to guide ethical decisions. The following worksheets and resources can help with this.

For some helpful materials to strengthen your and your client’s understanding of transference, check out the following worksheets.

1. Awareness Transference Worksheet

This basic worksheet helps both clients and clinicians identify specific people in their life and their cognitive and emotional reactions to them. This exercise can highlight how past relationships are being transferred to the present moment.

2. Transference Exercise

This free exercise was designed to help teach clinical psychology students about transference. It can be a helpful exercise to revisit, even among seasoned clinicians.

17 Exercises for Positive, Fulfilling Relationships

Empower others with the skills to cultivate fulfilling, rewarding relationships and enhance their social wellbeing with these 17 Positive Relationships Exercises [PDF].

Created by experts. 100% Science-based.

You’ll find even more resources around our blog around the topics of transference, communication boundaries, and the therapeutic relationship.

Check out some of the following free materials to get you started:

- 3-Step Mindfulness Worksheet Mindfulness is an important tool for both therapists and clients to practice on a consistent basis. This simple but effective worksheet can bring both parties to a place of self-awareness and decrease the likelihood of unproductive transference.

- Levels of Validation This short self-assessment helps therapists and counselors consider the level at which they typically validate the feelings and experiences of their clients, ranging from mindfully listening to radical genuineness.

- Listening Accurately Worksheet This handout presents five simple steps to facilitate accurate listening and can be used to help establish communication norms at the beginning of a therapeutic relationship.

- Assertive Formula This three-part worksheet lays out a formula to help you or your clients clearly and respectfully communicate when someone else’s behavior is causing a problem.

Besides these tools, these articles are excellent supplemental reading material:

- How to Establish Healthy Boundaries in Therapy

- Therapeutic Relationships in Counseling

- Termination in Therapy

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others build healthy relationships, this collection contains 17 validated positive relationships tools for practitioners. Use them to help others form healthier, more nurturing, and life-enriching relationships.

Mental health professionals practice in a very lonely world bound by confidentiality and ethical concerns. We must be simultaneously aware of the emotions and feedback clients project and the emotions and thoughts that are personally experienced.

Transference and countertransference can be a double-edged sword. They can destroy the therapeutic process or provide an avenue to healing. They can break down the therapeutic alliance or become its most effective tool.

Identifying examples of transference and countertransference is a wonderful starting point to prevent negative interference in therapy.

Self-reflection, mindfulness, empathy, and ethical boundaries are excellent tools to ensure that when transference arises in session, it is directed in a helpful and therapeutic way.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Relationships Exercises for free .

- Barker, R. (2014). The social work dictionary . NASW Press.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Volume I attachment . Basic Books.

- Boyer, L. B. (1982). Analytic experiences in work with regressed patients . Unknown publisher.

- Fink, B. (2011). The fundamentals of psychoanalytic technique: A Lacanian approach for practitioners . W. W. Norton & Co.

- Freud, S., & Breuer, J. (1895). Studies in hysteria . Penguin Books.

- Fuertes, J. N., Gelso, C., Owen, J., & Cheng, D. (2013). Real relationship, working alliance, transference/countertransference and outcome in time-limited counseling and psychotherapy. Counseling Psychology Quarterly , 26 (3), 294–312.

- Horacio, E. (2005). The fundamentals of psychoanalytic technique . Karnac Books.

- Jung, C. (1946). The psychology of transference . Princeton University Press.

- Lambert, M. J., Hansen, N. B., & Finch, A. E. (2001). Patient-focused research: Using patient outcome data to enhance treatment effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 69 , 159–172.

- Lichtenberg, J., Bornstein, M., & Silver, D. (1984). Empathy I . Analytic Press.

- Makari, G. J. (1994). Toward an intellectual history of transference. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America , 17 (3), 559–570.

- Newfoundland and Labrador Association of Social Workers. (2018). Standards of practice for social workers in Newfoundland and Labrador. Retrieved June 15, 2021, from https://nlcsw.ca/sites/default/files/inline-files/Standards_of_Practice.pdf

- Notaras, S. (2013). Attending to countertransference. Counseling Today , 9 , 29–31.

- Racker, H. (1988). The meaning and uses of countertransference. In B. Wolstein (Ed.), Essential papers on countertransference. New York University Press.

- Wachtel, P. L. (2008). Relational theory and the practice of psychotherapy . Guilford Press.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Can you please add a work cited page please .

It seems each time I read a Positive Psychology piece, it begins negatively. In this case: “For ages, the term “transference” has been associated with pathology, enmeshed boundaries, and unhealthy therapy sessions.” I have never found this to be true. Its originator found it to be an exciting and useful tool in treatment.

Hello, second time you mention that the references are at the bottom of the article but I don’t see them, looking for the Freud and Breuer (1895) one in particular. Can you post the link to actual reference here maybe? thank you in advance

If you scroll down to where it says “How useful was this article to you?” immediately above this you’ll see a grey button that says ‘References’ with a plus sign you can click (or just search ‘References’ in your browser to find it).

The reference you’re looking for is as follows: Freud, S., & Breuer, J. (1895). Studies in hysteria. Penguin Books.

Hope this helps!

– Nicole | Community Manager

You mention a resource on “low trajectory patient” (Perhaps the phrasing is incorrect). I would love more information on this or the resource. Thank you. Misty

Could you please clarify where in this article you read it? In which section and in what context? Then I can perhaps assist.

Thank you, Annelé

Where are the references cited listed? 1e. Frued, 1895. Seriously. I want to look it up.

Hi Brennan,

If you scroll to the very end of the article, you will find a button that you can click to reveal the reference list.

Well rounded article – thank you

I’d been wanting to learn more about transference so really enjoyed reading this one, Melissa — thank you! 🙂

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Setting Boundaries: Quotes & Books for Healthy Relationships

Rather than being a “hot topic,” setting boundaries is more of a “boomerang topic” in that we keep coming back to it. This is partly [...]

14 Worksheets for Setting Healthy Boundaries

Setting healthy, unapologetic boundaries offers peace and freedom where life was previously overwhelming and chaotic. When combined with practicing assertiveness and self-discipline, boundary setting can [...]

Victim Mentality: 10 Ways to Help Clients Conquer Victimhood

Life isn’t always fair, and injustice is everywhere. However, some people see themselves as victims whenever they face setbacks or don’t get their own way. [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

3 Positive Relationships Exercises Pack

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Res Psychother

- v.22(3); 2019 Dec 19

Transference interpretations as predictors of increased insight and affect expression in a single case of long-term psychoanalysis

Yasemin sohtorik İlkmen.

1 Department of Psychology, Boğaziçi University, Bebek, Istanbul

Sibel Halfon

2 Department of Psychology, Bilgi University, Istanbul, Turkey

Contributions: the authors contributed equally.

Improved insight and affect expression have been associated with specific effects of transference work in psychodynamic psychotherapy. However, the micro-associations between these variables as they occur within the sessions have not been studied. The present study investigated whether the analyst’s transference interpretations predicted changes in a patient’s insight and emotion expression in her language during the course of a long-term psychoanalysis. 449 thematic units from 30 sessions coming from different years of psychoanalysis were coded by outside raters for analyst’s use of transference interpretations using Transference Work Scale, and patient’s insight, positive emotions, anger and sadness were calculated using the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count System. Multilevel modeling analyses indicated that transference interpretations positively predicted patient’s insight and positive emotion words and negatively predicted anger and sadness. The qualitative micro-analyses of selected sessions showed that the opportunity to explore negative emotions within the transference relationship reduced the patient’s avoidance of such feelings, generated insight into negative relational patterns, and helped form more balanced representations of self and others that allowed for positive feelings. The findings were discussed for clinical implications and future research directions.

Introduction

The role of transference, as the repetition of repressed historical past in a new context with the therapist, has been recognized as an essential element of psychoanalytic therapies since Freud formally introduced the term in 1912. Freud initially thought transference was a form of resistance and disrupts the progress of analysis. As his theories on therapy and technique evolved over time, he considered the analysis of transference to be the most effective element of psychoanalytic treatment (Gay, 1988 ). Consequently, transference became a means to understand and translate the unconscious, and transference interpretations the necessary and primary components of analytic technique by fostering insight. Through this process the patient gains insights into their relationship patterns, and gets a chance to experience a different type of relating with the therapist who provides the conditions to achieve this change (Heimann, 1956 ). More recently, clinicians and researchers started to rely on broader definitions of transference, not solely as enactment of early relationships but also as a new experience influenced by the relationship with the therapist (Cooper, 1987 ). Transference interpretations in most empirical studies are defined as an explicit focus on the here-and-now relationship between the therapeutic dyad and links to earlier relationships (Hoglend, 1993 , 2004 ; Piper, Azim, Joyce, & McCallum, 1991 ). According to psychodynamic theory, transference interpretations are an essential component of psychodynamic technique because of their effectiveness in increasing insight about the nature of the one’s problems and in their immediate affective resonance to the patient as they are practiced in the here and now of the therapeutic relationship (Gabbard & Westen, 2003 ; Messer & McWilliams, 2007 ). However, linking hereand- now issues to earlier experiences is not always necessary, and actually not recommended for patients with severe personality disorders (Levy & Scala, 2012 ). For instance, in Transference Focused Psychotherapy developed particularly for patients with borderline personality disorder, interpretations are utilized to address the present unconscious particularly in the earlier phases of the treatment (Kernberg, 2016 ).

Despite this central position of transference interpretations in psychodynamic therapies, there is conflicting research evidence regarding the relationship between transference interpretations and treatment outcome. Whereas some research shows a direct association between transference interpretations and outcome ( i.e ., Clarkin, Levy, Lenzenweger, & Kernberg, 2007 ; Doering et al., 2010 ; Levy et al., 2006 ), others fail to report such an association ( i.e ., Hoglend, 1993 ; Piper et al., 1991 ). These null findings suggest that rather than a direct association between transference interpretations and outcome, this relation may be mediated by other mechanisms of change, particularly increased affect expression, tolerance, and insight (Johansson et al., 2010 ; Høglend & Hagtvet, 2019). There is converging research evidence that shows that gains in insight on one’s problems during psychodynamic treatment are associated with successful outcome (Grande, Rudolf, Oberbracht, & Pauli-Magnus, 2003 ; Johansson et al., 2010 ; Kivligham, Multon, & Patton, 2000 ) and these results are further strengthened when this is combined with emotional expression (Fisher, Atzil- Slonim, Barkalifa, Rafaeli, & Peri, 2016 ; Kramer, Pascual- Leone, Despland, & de Roten, 2015 ; Solbakken, Hansen, & Monsen, 2011 ) creating a cognitive-emotional processing that would not be possible without either component. It is possible that these change mechanisms are best activated within the transference relationship, where a cognitive-affective restructuring takes place in the here and now of an affectively charged relationship and interventions help the patient to gain insight on his/her own internal world and relationship patterns (Kernberg, Diamond, Yeomans, Clarkin, & Levy, 2008 ). Following these findings, the aim of this study was to investigate the associations between transference interpretations and a patient’s changes in emotion expression and insight as expressed in her language in a single case of long-term psychoanalysis.

Transference interpretations and mechanisms of change in psychodynamic therapies

The association between transference interpretations, affective resonance and insight has been empirically investigated in few research studies. Johansson et al. ( 2010 ) found in a randomized clinical trial that the effect of transference interpretations on interpersonal and overall functioning was mediated by increased insight. In another study, Ulberg, Amlo, Johnsen Dahl, and Hoglend ( 2017 ) demonstrated on two clinical cases that transference interpretations were associated with improved therapy outcome by enhancing insight. Investigating the mechanisms of change, Messer ( 2013 ) demonstrated the positive impact of insight achieved through transference interpretations in a single case study. However, insight needs to be linked to appropriate affect in order for working through to take place (Gabbard & Westen, 2003 ). To the authors’ knowledge, only Høglend and Hagtvet (2019) investigated whether increased affect awareness along with insight mediated the relation between initial functioning and outcome and found support for this model long-term transference focused work.

Contemporary psychoanalytic theories emphasize the importance of the corrective emotional experience within the therapeutic relationship as an essential element of change (Gabbard & Westen, 2003 ). These relational theories regard human psych as emerging within a relational context in which intrapsychic and interpersonal aspects continually shape each other (Mitchell, 1988 ). One of the central themes in the relational theories is the interaction between transference and countertransference, and how they influence each other (Aron, 2006 ). In these views, both analyst and patient contribute to the analytic interaction. The insights gained in therapy are considered specific to the particular analyst-patient dyad because they are co-created by this analytic couple (Renik & Spillius, 2004 ). Since both parties bring their own subjective experiences to this interaction, they both contribute significantly in the co-creation of the patient’s understanding of his/her mental life. In this intersubjective view of the clinical encounter both participants must mutually recognize each other’s subjectivity in order to achieve separation, awareness of the outside reality and ability for attunement with the other (Benjamin, 1990 ). However, recent theories suggest that therapeutic change is facilitated by both insight and therapeutic relationship as well as their interaction in complex ways (Gabbard & Westen, 2003 ).

Linguistic analyses of affect expression and insight

Traditionally, patient’s insight and affect expression have been investigated via self-report scales or observerrated measures, which provide an outside and partial perspective into the immediate experience of the patient in the session. In order to address this problem, computerized linguistic analyses have been employed on session transcripts to understand the psychological, particularly cognitive and affective processes that are associated with patient’s word choices. Pennebaker and coworkers have done pioneering work in the study of different word categories and linking these with various psychological states based on their computer based linguistic program named Linguistic Inquiry Word Count (LIWC) (Pennebaker, Booth, Boyd, & Francis, 2015a ). They have not focused particularly on psychodynamic therapies; however, they extensively analyzed the writing features most strongly associated with enhanced psychological and physiological health and found that it is important for people to generate insight and express affect related to personal experiences, especially ones that are traumatic or stressful (Pennebaker & Seagal, 1999 ). In particular, stories that contained a high rate of emotion words ( e.g ., sad , hurt , guilt , joy ) and insight words ( e.g ., understood , thought , know ) showed the greatest benefit (Pennebaker & Seagal, 1999 ).

Other studies showed that the valence of emotion words affected different facets of psychological health. For example, using a high frequency of positive emotion words in an expressive writing exercise was associated with improved physical health as indicated by decrease in the number of physician visits and self-report symptoms (Pennebaker, Mayne, & Francis, 1997 ). The specific types of negative emotion words also relate to adjustment and can shed light on additional facets of emotional expression. In one study, researchers examined the expression of negative emotions in written texts and found that the expression of anger and sadness were associated with higher quality of life and lower depression scores among breast cancer patients (Lieberman & Goldstein, 2006 ).

Computerized linguistic analyses of psychodynamic treatments

Computerized linguistic analyses of treatment processes provide the means to integrate systematic linguistic analysis of sessions with clinical evaluations. Erhard Mergenthaler and his group focused on the emotional tone (density of emotional words) and level of abstraction (the amount of abstract nouns) within patients’ language in psychodynamic therapies and found that successful outcome in psychodynamic therapy is associated with increased use of emotion and abstraction in language, which shows that the patients have emotional access to conflictual themes and can reflect upon them building insight (Buchheim & Mergenthaler, 2000; Gelo & Mergenthaler, 2012; Lepper & Mergenthaler, 2008 ). Bucci’s multiple code theory is another application of these premises to psychoanalytic research using the concept of Referential Activity (RA; see Bucci, Maskit, & Murphy, 2016 , for a review). Bucci has found that patients initially come to therapy with sensory and somatic emotion schemas not yet associated with words. However, if the treatment is working properly, these schemas are integrated in a narrative, which will include the analyst, sometimes explicitly, almost certainly implicitly and the representations of emotions in the here and now of the therapeutic relationship (Bucci & Maskit, 2007 ; Bucci, Maskit, & Hoffman, 2012 ). Even though Pennebaker and his group have not particularly studied patients’ linguistic choices in psychodynamic treatments, the associations they found between emotion expression and insight in expressive writing tasks have to do with the creation of a narrative that provides a cognitive and affective elaboration of incoherent experiences; an idea that is much akin to the psychoanalytic principles of the talking cure .

In terms of the types of emotions expressed, Mergenthaler ( 2008 ) posits that negative emotion occurs first within a session for problems to be elicited followed by an increase in positive emotion for key helpful moments of problem solving to begin. Similarly, Pennebaker and Francis ( 1996 ) found that students who used more positive emotion words and words indicating insight and causal thinking when writing about thoughts and feelings had better health outcomes.

Some studies examined how therapists’ interventions predicted changes in patient’s linguistic choices. For example, Vegas, Halfon, Cavdar, and Kaya ( 2015 ) looked at the association between the analyst’s interventions and patient’s discourse patterns and found that analytic explorations predicted the patient’s emotional and insight focused language. Recent literature has begun to examine therapist-patient discourse to identify therapist and patient contributions to significant change processes within therapy (Levitt & Piazza-Bonin, 2011 ). In particular, Valdés et al. (2010) found that within change moments patients brought up a number of different emotions and therapists explored these emotions. Valdés Sanchez (2012) found that during change episodes when therapist showed understanding and mirroring of patient’s affective states in the here and now and gave new meaning to emotional material, patient presented novel emotional content. Furthermore, patient responded with cognitive insight words in response to therapist’s emotional processing of transferential material. These studies indicate that patients respond to therapist’s interventions with increased insight and emotion expression in language particularly during change moments. However, to the author’s knowledge, there have been no prior studies that specifically assessed the associations between transference interpretations and patient’s level of insight and emotion expression in language.

The case of study

The sessions examined in the current study were taken from a case known as Mrs. C in the psychoanalytic literature and has been studied previously by various researchers (Ablon & Jones, 2005 ; Halfon, Fisek, & Cavdar, 2017 ; Halfon & Wenstein, 2013 ; Jones & Windholz, 1990 ). Mrs. C was in psychoanalysis for six years, yielding nearly 1,100 hours of which were all audio-taped (Jones & Windholz, 1990 ). Using the Q-technique, Jones and Windholz ( 1990 ) examined Mrs. C’s analysis, and concluded that the outcome of her analysis was successful. They found that over the course of her treatment, Mrs. C exhibited increased capacity for free association and access to her emotions, greater self-disclosure and decreased amount of intellectualization and rationalization. They also reported improvement in her initial complaints of feelings of inadequacy, guilt and anxiety. On the analyst’s part, he became more active in interpreting Mrs. C’s defenses and recurrent relationship patterns over the course of the treatment. More recently, Halfon and Weinstein ( 2013 ) and Halfon, Fisek and Cavdar ( 2017 ) studied 30 sessions from the 70 studied by Jones and Windholz ( 1990 ) and found an improved capacity on the part of the patient to verbally express her emotions throughout her analysis.

These findings indicate that there was an increase in affective expression and elaboration in the case of study, however the specific types of interventions associated with this pattern have not been investigated. Literature has shown that transference interpretations impact outcome through increased insight that is combined with emotion expression in the here and now of the therapeutic relationship. Moreover, some studies show that in change moments, patient expresses more positive affect, whereas other studies show that there is initially negative affect expression. Expression of anger and sadness have most frequently been associated with transference work ( i.e ., Levy et al., 2006 ) that eventually gives way to more positive affect. Therefore, this study will examine the associations of transference interpretations on insight and positive and negative affect (anger and sadness) expression of the patient. Our specific hypotheses are: i) transference interpretations will be associated with an increase in emotional expression (positive emotions as well as anger and sadness), ii) transference interpretations will be associated with an increase in use of insight words.

The patient, Mrs. C, was a married woman in her late twenties. She was a social worker, and gave birth to two children throughout her 6 year-long psychoanalysis. She originally went to analysis with complaints of lack of sexual desire and pleasure, difficulty experiencing her feelings, being self-critical and uncomfortable disagreeing with others, and feeling tense and worried about her mistakes (Jones & Windholz, 1990 ). The patient gave oral consent to be audiotaped as part of her regular, ongoing psychoanalytic treatment. The taping was done unobtrusively in the usual course of a five times per week psychoanalysis. 214 sessions of this patient’s treatment have been published by Sage Press and were systematically deidentified. It is from this published de-identified data set that sampling for the present study was done.

Session selection and segmentation

Sessions were randomly selected over a span of general time period in the treatment from 70 sessions that were already studied in depth by other researchers (Bucci, 1997 ; Jones & Windholz, 1990 ). Sessions 90 to 94 from the first year, Sessions 258 to 262 from the second year, Sessions 431 to 435 from the third year, Sessions 601 to 605 from the fourth year, Sessions 767 to 771 from the fifth year, and finally Sessions 936 to 940 from the sixth year of treatment were chosen.

Each session was divided into thematic units following the procedure developed by Waldron et al. ( 2004 ). This procedure allows the creation of units that take into consideration the turns of speech between the analyst and the patient. Specifically, thematic units consist of clinically meaningful segments of communication that aggregate around a given theme. This procedure yielded different number of units (min=6 to max=24) between sessions ( M =14.97, SD =4.55). To do the segmenting, two clinical psychology doctoral-level students were trained using the segmenting manual developed by Waldron et al. ( 2004 ). Afterwards, they segmented each session with an interrater reliability score of 0.83. Disagreements were resolved upon discussion with the second author.

Transference interpretations

Each unit was scored based on the criteria provided by Transference Work Scale (Ulberg, Amlo, & Hoglend, 2014 ). Ulberg et al. ( 2014 ) define transference interpretation as any intervention aimed to point out the therapistpatient relationship in the therapeutic process. Accordingly, there are five categories of transference interventions, which are not designed to be hierarchical: 1) addressing the transaction between the analyst and the patient, 2) encouraging the exploration of the thoughts and feelings about the therapy and analyst, 3) encouraging the exploration of how patient believes the analyst might think and feel about them, 4) including herself in the interpretation of internal dynamics and transference manifestations, and 5) providing genetic interpretation and linking this with therapeutic interaction. The scale has good interrater reliability for category classification, as kappa values range between 0.60 and 0.90 (Ulberg, Amlo, Critchfield, Marble, & Hoglend, 2014 ). In the current study, the sessions were rated by three independent raters, a doctoral level clinical psychologist with over ten years of experience and two clinical psychology master’s level students, who received ten hours of training from the first author. Interrater reliabilities between three independent raters were excellent ranging between 0.94 and 0.96 ( M =0.96, SD =0.01).Disagreements were resolved with consultation with the first author.

Linguistic analyses

The LIWC (Pennebaker et al., 2015a ) is a computerassisted method for studying emotional, cognitive, and structural aspects of verbal and written speech. The LIWC compares transcripts to its dictionary, providing counts of words, as proportions of the total words analyzed within the transcript that tap into 66 various domains or word categories. The LIWC has been validated across a number of studies as detailed by Pennebaker, Chung, Ireland, Gonzales, and Booth ( 2007 ) with the psychological language categories related to health outcomes. In line with the aims of this study, we used LIWC word categories tapping into insightwords (think, know, realize, meaning, understand), positive emotions (love, fun, good, happy, gift, nice, sweet), sadness (crying, grief, sad) and anger (hate, kill, annoyed, rude) scores. Internal reliability coefficients are 0.84 for insight, 0.64 for positive emotion, 0.70 for sadness and 0.53 for anger categories (Pennebaker, Boys, Jordan, & Blackburn, 2015 b).

Procedures and data analytic strategy

In order to code for the type of intervention in each unit, a score of “0” was assigned if there was no intervention, “2” if analyst used any one of the transference interventions as described by above categories in TWS, and “1” for the remaining interventions that did not meet criteria for transference interventions. These non-transference interventions were analyst’s activities that included explorations, clarifications and questions as well as nontransference interpretations such as addressing patient’s conflicts ( e.g ., So you talked to your mother on the phone , What was your choice? , How do you feel it is connected? Well it’s always been hard for you to imagine feeling opposite ). All units (patient sections) were then entered into the LIWC2015 to calculate the percentage of insight words, positive emotion words, and sadness and anger words.

In our data psychotherapy units ( N =449) were nested within sessions ( N =30) who were nested within years ( N =6). Therefore, we used a multilevel modeling approach using MLwin Version 3 (Rasbash, Steele, Browne, & Goldstein, 2015 ). Since multiple sessions were conducted within the same year, we investigated the degree of interdependency due to years. We used two-level (units nested within sessions) and three level (units nested within sessions nested within years) empty multilevel models, where we entered our dependent variables, that were positive emotions, insight, anger and sadness with no predictor variables. The year level ICCs were 0.00, ns. , for positive emotions, insight, anger and sadness, which showed that years accounted for 0.00% of the variance in positive emotions, insight, anger and sadness suggesting that the variance in the dependent variables is not attributable to differences between years. The variance at the session level was slightly higher, albeit not significant for the dependent variables, such that the session level ICCs were 0.03 for positive emotions accounting for 0.45% of the variance, 0.00 for insight and sadness accounting for 0.00% of the variance, and 0.03 for anger accounting for 0.01% of the variance. Even though the session level variances were not significant, we chose to run two level models to control for the interdependency between units that may be attributable to session characteristics.

Quantitative results

Descriptive statistics.

The descriptive statistics and inter-correlations between the study variables are presented in Table 1 . Table 2 shows the detailed descriptive statistics of the interventions. Over the course of the treatment, of the 226 analytic interventions, 43% of the analyst’s interventions were non-transference type and 57% were transference interpretations. The analyst’s transference interventions increased over the course of treatment. When we look more closely at the types of transference interventions the analyst practiced, the analyst most frequently addressed the transaction between himself and the patient (Category 1; 44%), followed by encouraging the exploration of the thoughts and feelings about the therapy and analyst (Category 2; 36%), including himself in the interpretation of internal dynamics and transference manifestations (Category 4; 10%) and the rest of the categories were practiced only a total of 10% of the time. The frequency of the categories practiced changed over the course of treatment such that in the first three years, the analyst mostly made Category 1 transference interventions, however after the third year, there was an increase in the Category 2 and 4 interventions.

Descriptive Statistics and Pearson’s Correlations for the Study Variables (N=442).

The difference between total number of interventions (n=449) and study variables (n=442) results from the fact that there were 7 incidents of therapist intervention where patient did not respond verbally, so there were no words to analyze.

** P<0.01.

Multilevel modeling

We conducted 4 separate fixed effect multilevel models with maximum likelihood (ML) estimation to analyze the data that nests change in units within the sessions, where positive emotions, insight, anger and sadness were our dependent variables and type of analyst’s activity (transference intervention, non-transference intervention, no intervention) was our predictor. No intervention was the reference category.

The results indicated that ( Table 3 ) both transference and non-transference interventions positively predicted positive emotions. Transference interventions positively predicted insight, and negatively predicted anger and sadness, whereas non-transference interventions were not significant in these models.

Qualitative analyses

The following segments were chosen according to patient’s linguistic markers. We chose segments where there was a transference interpretation and an increase in one of the linguistic markers compared to the session mean.

Year 1, session 93

The patient talks about the difficult things she is facing in her life and reports that she feels uninvolved and unable to deal with these things. The analyst brings her attention to the transference:

Analyst: Including here. (category 1, address transaction)

Patient: … instead of meeting them, I am running away from them.

Analyst: You said, ah, earlier that you’ve been feeling, I think you called it, uninvolved all week. I have a kind of an impression that that’s the way you’re feeling here, now. But I’m not sure. (category 1, address transaction)

Patient: … And both weeks I’ve overslept a great deal, which I never, or very rarely do. And just somehow, as long as I’m in bed, asleep, then these things don’t, whatever it is, don’t bother me… (She elaborates further on her passivity, regressing into sleep to avoid facing difficulties). I was just thinking about the way I’m not feeling involved in anything today. And it’s almost as if wherever I turn my thoughts to, I either have very ambivalent or confused or contradictory thoughts or feelings about different things so that I immediately withdraw from thinking about it, anything.

At this point, the patient expresses negative affect (feeling uninvolved, confused/ambivalent) outside of the transference valation; however, with the analyst’s focus on the transference relationship, she brings up a transference reaction.

Patient: … It’s funny, something just occurred to me that, uhm, seems so little but now it seems that it could have thrown me for this whole time. When, when I came in today, I felt as if when I said hello to you that I looked at, looked at your eyes, really, longer than I ever had before. And I was sort of aware that I wasn’t kind of hiding my face away from you as soon as I said hello, which I usually do. And then afterwards, I felt very, right when I came in, very uncomfortable that I had, well, it was in some way, exposed myself or made myself vulnerable.

Summary of analyst interventions in frequencies and percentages.

Summary of multilevel models predicting emotions and insight by type of intervention.

No intervention is the reference category.

** P<0.01

* P<0.05.

Analyst: How would it make you vulnerable? (Category 2, thoughts and feelings about therapy)

Patient: I don’t really think I understand how, except that I know I feel uncomfortable looking at people. Not always but very often I’m aware of sort of forcing myself to look at people because my inclination is not to.

Analyst: Were you aware of any particular thing you saw? (Category 3,beliefs about therapist)

Patient: When I looked at your eyes?

Analyst: Yeah. I mean, was there any more to it than that? (Category 3 cont.)

Patient: (Pause) Well, it was just sort of a friendly expression that, uhm, I don’t know exactly what it was. But I think it’s an expression I like to see and yet I feel uncomfortable if I see it and, and keep looking at it. (Pause)

She is now actively engaged and present as the analyst explores the transference and tries to keep the patient in the here-and-now by exploring her vulnerability in relation to himself. In response, even though the patient reports on her passivity in her outside relationships, she talks about being active with the analyst (looking him right in the eye) and the accompanying anxiety about exposing herself. She can elucidate these fears only after the analyst invites these responses in the transference relationship. Compared to the beginning of the session where she was talking about experiencing a general lack of involvement, she now shows increased self-focus, increased emotion that is more varied (feelings of discomfort and vulnerability) as well as positive affect (liking the analyst’s friendly expression). She also shows insight into why she may be experiencing these feelings.

Year 3, session 433

This is one of the first sessions after the patient came back to analysis following the birth of her first child. She talks about her distance from her child, which helps her retrieve an important childhood memory: