Distance Learning

Using technology to develop students’ critical thinking skills.

by Jessica Mansbach

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is a higher-order cognitive skill that is indispensable to students, readying them to respond to a variety of complex problems that are sure to arise in their personal and professional lives. The cognitive skills at the foundation of critical thinking are analysis, interpretation, evaluation, explanation, inference, and self-regulation.

When students think critically, they actively engage in these processes:

- Communication

- Problem-solving

To create environments that engage students in these processes, instructors need to ask questions, encourage the expression of diverse opinions, and involve students in a variety of hands-on activities that force them to be involved in their learning.

Types of Critical Thinking Skills

Instructors should select activities based on the level of thinking they want students to do and the learning objectives for the course or assignment. The chart below describes questions to ask in order to show that students can demonstrate different levels of critical thinking.

*Adapted from Brown University’s Harriet W Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning

Using Online Tools to Teach Critical Thinking Skills

Online instructors can use technology tools to create activities that help students develop both lower-level and higher-level critical thinking skills.

- Example: Use Google Doc, a collaboration feature in Canvas, and tell students to keep a journal in which they reflect on what they are learning, describe the progress they are making in the class, and cite course materials that have been most relevant to their progress. Students can share the Google Doc with you, and instructors can comment on their work.

- Example: Use the peer review assignment feature in Canvas and manually or automatically form peer review groups. These groups can be anonymous or display students’ names. Tell students to give feedback to two of their peers on the first draft of a research paper. Use the rubric feature in Canvas to create a rubric for students to use. Show students the rubric along with the assignment instructions so that students know what they will be evaluated on and how to evaluate their peers.

- Example: Use the discussions feature in Canvas and tell students to have a debate about a video they watched. Pose the debate questions in the discussion forum, and give students instructions to take a side of the debate and cite course readings to support their arguments.

- Example: Us e goreact , a tool for creating and commenting on online presentations, and tell students to design a presentation that summarizes and raises questions about a reading. Tell students to comment on the strengths and weaknesses of the author’s argument. Students can post the links to their goreact presentations in a discussion forum or an assignment using the insert link feature in Canvas.

- Example: Use goreact, a narrated Powerpoint, or a Google Doc and instruct students to tell a story that informs readers and listeners about how the course content they are learning is useful in their professional lives. In the story, tell students to offer specific examples of readings and class activities that they are finding most relevant to their professional work. Links to the goreact presentation and Google doc can be submitted via a discussion forum or an assignment in Canvas. The Powerpoint file can be submitted via a discussion or submitted in an assignment.

Pulling it All Together

Critical thinking is an invaluable skill that students need to be successful in their professional and personal lives. Instructors can be thoughtful and purposeful about creating learning objectives that promote lower and higher-level critical thinking skills, and about using technology to implement activities that support these learning objectives. Below are some additional resources about critical thinking.

Additional Resources

Carmichael, E., & Farrell, H. (2012). Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Online Resources in Developing Student Critical Thinking: Review of Literature and Case Study of a Critical Thinking Online Site. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice , 9 (1), 4.

Lai, E. R. (2011). Critical thinking: A literature review. Pearson’s Research Reports , 6 , 40-41.

Landers, H (n.d.). Using Peer Teaching In The Classroom. Retrieved electronically from https://tilt.colostate.edu/TipsAndGuides/Tip/180

Lynch, C. L., & Wolcott, S. K. (2001). Helping your students develop critical thinking skills (IDEA Paper# 37. In Manhattan, KS: The IDEA Center.

Mandernach, B. J. (2006). Thinking critically about critical thinking: Integrating online tools to Promote Critical Thinking. Insight: A collection of faculty scholarship , 1 , 41-50.

Yang, Y. T. C., & Wu, W. C. I. (2012). Digital storytelling for enhancing student academic achievement, critical thinking, and learning motivation: A year-long experimental study. Computers & Education , 59 (2), 339-352.

Insight Assessment: Measuring Thinking Worldwide

http://www.insightassessment.com/

Michigan State University’s Office of Faculty & Organizational Development, Critical Thinking: http://fod.msu.edu/oir/critical-thinking

The Critical Thinking Community

http://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/defining-critical-thinking/766

Related Posts

Selecting a Video Style

Focus on Teaching and Learning Highlights Active Learning

Ways to Use Panopto in Online Courses

Is Technology Driving Online Education Off A Cliff?

9 responses to “ Using Technology To Develop Students’ Critical Thinking Skills ”

This is a great site for my students to learn how to develop critical thinking skills, especially in the STEM fields.

Great tools to help all learners at all levels… not everyone learns at the same rate.

Thanks for sharing the article. Is there any way to find tools which help in developing critical thinking skills to students?

Technology needs to be advance to develop the below factors:

Understand the links between ideas. Determine the importance and relevance of arguments and ideas. Recognize, build and appraise arguments.

Excellent share! Can I know few tools which help in developing critical thinking skills to students? Any help will be appreciated. Thanks!

- Pingback: EDTC 6431 – Module 4 – Designing Lessons That Use Critical Thinking | Mr.Reed Teaches Math

- Pingback: Homepage

- Pingback: Magacus | Pearltrees

Brilliant post. Will be sharing this on our Twitter (@refthinking). I would love to chat to you about our tool, the Thinking Kit. It has been specifically designed to help students develop critical thinking skills whilst they also learn about the topics they ‘need’ to.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Search Search Search …

- Search Search …

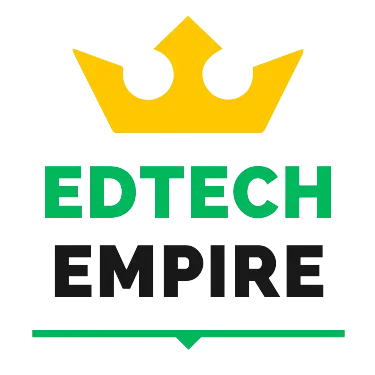

How to Teach Critical Thinking in the Digital Age: Effective Strategies and Techniques

In today’s rapidly evolving digital landscape, the ability to think critically has become increasingly important for individuals of all ages. As technology advances and information becomes more readily available, it is essential for teachers to adapt their methods to effectively teach critical thinking skills in the digital age.

However, the task of teaching critical thinking can prove challenging. Research from Daniel Willingham , a professor of psychology at the University of Virginia, suggests that students may struggle to apply these skills across different subjects and contexts. Nonetheless, with the right strategies and resources, educators can successfully incorporate critical thinking into their digital learning experiences , empowering their students to navigate the complex world of information.

The Importance of Critical Thinking in the Digital Age

In the digital age, we are constantly surrounded by information from various sources, making it essential for individuals to develop critical thinking skills in order to effectively evaluate the credibility and relevance of the content they consume. Furthermore, critical thinking helps people think through problems and apply the right information when developing solutions.

One of the challenges that the digital age presents is the need to differentiate factual and fake information. With the rise of social media and digital platforms, it becomes increasingly easy for false or misleading information to spread quickly. As a result, being able to discern between reliable and unreliable sources becomes an essential skill (The Tech Edvocate) .

In addition, critical thinking skills are vital in the workforce, as employees are expected to be effective problem solvers, innovative thinkers, and strong communicators. Possessing strong critical thinking skills prepares individuals to thrive in a constantly changing environment, as they can adapt to new situations, understand different perspectives, and make educated decisions.

Teaching critical thinking from a young age is crucial. Educators can use various strategies and techniques to integrate critical thinking in their lessons, such as using open-ended questions, encouraging students to evaluate sources, and promoting group work where students can learn from each other (Forbes) .

Challenges Faced in Teaching Critical Thinking Online

Teaching critical thinking skills online can be a challenging task for educators due to numerous obstacles. This section discusses the challenges of teaching critical thinking, focusing on difficulties such as information overload and technology distractions.

Information Overload

In the digital age, online students have access to an overwhelming amount of information. This can lead to difficulty in focusing on critical thinking exercises and applying those skills to new subject areas, as students struggle to navigate the vast online landscape of resources and materials.

Information overload can impede the development of effective critical thinking skills, as students find it more difficult to discern credible resources and make informed judgments. Educators must guide students in selecting appropriate resources and actively engage them in critical reflection on the information they encounter.

Technology Distractions

Another challenge in teaching critical thinking online is the presence of technology distractions. Online learners have to manage their time and attention across multiple devices and platforms, which can detract from their engagement with the learning material.

These distractions impact students’ ability to concentrate on critical thinking tasks and apply learned strategies. Additionally, constant multitasking can reduce the effectiveness of online learning, as students must split their focus between different tasks without giving their full attention to any one subject.

To mitigate technology distractions, educators can incorporate strategies such as limiting the use of technology during specific times, promoting time management skills, and offering engaging multimedia content. They can also foster a structured and supportive online learning environment, which encourages students to practice critical thinking throughout their coursework.

Techniques for Teaching Critical Thinking

Asking open-ended questions.

One effective technique for teaching critical thinking is to ask open-ended questions. These questions require more thought and exploration than simple yes or no answers, prompting students to critically analyze the issue at hand. Incorporating open-ended questions into lessons can encourage a deeper level of engagement and understanding in various subjects.

Debate and Discussion

Another valuable method for teaching critical thinking skills is to promote debate and discussion in the classroom. Through debates and discussions, students learn to listen to diverse perspectives, analyze arguments, and develop their own informed opinions. Encouraging students to express their ideas and engage with their peers in a respectful and thoughtful manner can foster a culture of critical thinking in the classroom.

Case Studies and Real-World Applications

Using case studies and real-world applications can help students develop critical thinking skills by connecting the material with real-life scenarios. When students analyze case studies, they can practice solving complex problems and applying the theoretical concepts they have learned to make informed decisions. Additionally, incorporating real-world examples and applications in lessons can make the learning experience more engaging and relevant for students.

Teaching Argument Evaluation

Teaching students how to evaluate arguments is an essential aspect of fostering critical thinking skills. By teaching them to identify the strengths and weaknesses of different arguments, students can better understand the nuances of logic and reasoning. This skill is especially crucial in the digital age, where students are often exposed to various sources of information, both reliable and unreliable. By developing their argument evaluation skills, students will be better equipped to navigate and assess the credibility of information they encounter online and in everyday life.

Digital Tools for Enhancing Critical Thinking

Teaching critical thinking in the digital age can be facilitated by leveraging digital tools that promote active learning and deeper engagement. This section explores various digital tools that can enhance critical thinking skills in students, including interactive learning platforms and collaboration and communication tools.

Interactive Learning Platforms

Interactive learning platforms help students develop critical thinking skills by engaging them in challenging activities that require problem-solving, analysis, and evaluation. These platforms often incorporate game-based elements and multimedia content to stimulate interest and maintain motivation.

For example, digital storytelling can be used to promote reflection, analysis, and synthesis skills in students. By creating and sharing their stories, students can critically assess their beliefs, values, and experiences, while comparing and contrasting them with their peers’ perspectives.

Collaboration and Communication Tools

Collaborative tools, such as online discussion forums, video conferencing, and shared documents, facilitate opportunities for students to exchange ideas, brainstorm solutions, and develop arguments on various topics. These tools foster critical thinking by encouraging students to analyze and evaluate different perspectives.

For instance, implementing project-based learning activities encourages students to work together, research, analyze data, and propose solutions to real-world problems. Through this collaborative process, students refine their critical thinking skills while learning how to communicate effectively and resolve conflicts.

Another example is the use of video conferencing tools, such as Zoom or Google Meet, for online debates or panel discussions. These sessions enable students to take a deep dive into topics and engage in structured discussions that challenge their assumptions and hone their critical thinking abilities.

Overall, integrating digital tools in the teaching process can effectively promote critical thinking in students, preparing them to thrive in the digital age.

Assessing Students’ Critical Thinking Skills

Assessing students’ critical thinking skills in the digital age requires a combination of formative and summative assessment methods. This section will outline these methods and explain how they can effectively be applied in the classroom.

Formative Assessment Methods

Formative assessment methods focus on continuous feedback and monitoring of students’ progress during the learning process. These methods aim to identify areas where students may require additional support or instruction. Some formative assessment methods for critical thinking skills include:

- Think-Pair-Share: An activity in which students think about the topic or question, discuss their thoughts with a partner, and then share their ideas with the whole class. This encourages students to evaluate different perspectives and revise their thinking accordingly.

- Questioning Techniques: Employing open-ended and higher-order questioning strategies can stimulate students’ critical thinking skills, prompting them to analyze, synthesize, and evaluate information. Examples of these questions can be found here .

- Peer Review: Students provide feedback on each other’s work by identifying strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement. This encourages self-reflection and fosters a collaborative learning environment.

Summative Assessment Methods

Summative assessments measure students’ critical thinking skills at the end of a unit, course, or academic year. These assessments aim to determine students’ level of competence and measure their growth over time. Some summative assessment methods for critical thinking include:

- Performance-Based Assessments: These assessments require students to apply their critical thinking skills to complete a task or solve a problem. Examples include case studies, debates, and presentations.

- Essay Examinations: Essay exams provide an opportunity for students to demonstrate their critical thinking skills through written analysis, synthesis, and evaluation of information.

- Digital Assessments: Digital assessments can be used to assess critical thinking skills by incorporating multimedia elements, interactive features, and real-time feedback. Examples can be found at ExamSoft .

By integrating both formative and summative assessment methods, educators can provide a comprehensive and accurate understanding of students’ critical thinking abilities in the digital age.

Continuous Improvement and Adaptation

In the digital age, it is crucial for educators to promote continuous improvement and adaptation in the development of critical thinking skills. As technology and information evolve rapidly, teachers must actively engage students in reflecting on their learning process and adjusting their strategies accordingly.

A useful approach to foster continuous improvement is to encourage students to set goals, reflect on their progress and actively seek feedback. This process can be facilitated through digital tools such as online discussions, project-based learning, and gamification .

Furthermore, educators can:

- Implement mini research assignments that challenge students to investigate topics further and engage in self-guided exploration.

- Introduce debates or collaborative projects that require students to apply critical reasoning and consider multiple perspectives.

- Use active learning methods such as brainstorming sessions, trainings, and case studies to encourage students to analyze and evaluate information before drawing conclusions.

Taking advantage of digital resources, teachers can create an environment where students continuously refine their critical thinking abilities and adapt to the ever-changing digital landscape. By implementing these strategies, educators will better prepare students to effectively navigate and contribute to the digital age.

In the digital age, teaching critical thinking skills requires the incorporation of effective instructional strategies and innovative technologies. Engaging learners in activities such as data collection, analysis , and group discussions promotes a dynamic learning environment where students can develop and sharpen their thinking abilities.

Teachers should consider multiple methods to facilitate the development of critical thinking. By integrating different teaching approaches , educators can create a rich and diverse educational experience for their students. This may include the use of various digital tools, such as collaborative platforms, serious games, and immersive technologies, which enhance the learning process and keep the students motivated and engaged.

Adaptability and continuous professional improvement are essential aspects for educators striving to foster critical thinking skills in a digital age. By staying up-to-date with current trends and research , as well as incorporating new instructional approaches and technologies, teachers will be better equipped for navigating and succeeding in the rapidly evolving educational landscape.

Ultimately, empowering learners with robust critical thinking skills will not only prepare them for academic success but also help them become responsible digital citizens who can make informed decisions in a highly interconnected world. By embracing the opportunities that digital technologies provide and adapting teaching practices accordingly, educators can truly make a lasting impact on their students’ lives.

You may also like

The Role of Intuition in Critical Thinking: Unraveling the Connection

Intuition plays a significant role in the process of critical thinking. As an innate ability, intuition allows individuals to make decisions and […]

Critical Thinking in Healthcare and Medicine: A Crucial Skill for Improved Outcomes

Critical thinking is a crucial skill for individuals working in various healthcare domains, such as doctors, nurses, lab assistants, and patients. It […]

What’s the Difference Between Critical Thinking and Scientific Thinking?

Thinking deeply about things is a defining feature of what it means to be human, but, surprising as it may seem, there […]

The Basics of Using Critical Thinking in Business

In the world of business, being precise and careful is highly recommended. However, how often do you respond too rashly to a […]

Does Technology Help Boost Students’ Critical Thinking Skills?

- Share article

Does using technology in school actually help improve students’ thinking skills? Or hurt them?

That’s the question the Reboot Foundation, a nonprofit, asked in a new report examining the impact of technology usage. The foundation analyzed international tests, like the Programme for International Student Assessment or PISA, which compares student outcomes in different nations, and the National Assessment of Educational Progress or NAEP, which is given only in the U.S. and considered the “Nation’s Report Card.”

The Reboot Foundation was started—and funded—by Helen Bouygues , whose background is in business, to explore the role of technology in developing critical thinking skills. It was inspired by Bouygues’ own concerns about her daughter’s education.

The report’s findings: When it comes to the PISA, there’s little evidence that technology use has a positive impact on student scores, and some evidence that it could actually drag it down. As for the NAEP? The results varied widely, depending on the grade level, test, and type of technology used. For instance, students who used computers to do research for reading projects tended to score higher on the reading portion of the NAEP. But there wasn’t a lot of positive impact from using a computer for spelling or grammar practice.

And 4th-graders who used tablets in all or almost all of their classes scored 14 points lower on the reading exam than those who reported never using tablets. That’s the equivalent of a year’s worth of learning, according to the report.

However, 4th-graders students who reported using laptops or desktop computers “in some classes” outscored students who said they “never” used these devices in class by 13 points. That’s also the equivalent of a year’s worth of learning. And 4th-grade students who said they used laptops or desktop computers in “more than half” or “all” classes scored 10 points higher than students who said they never used those devices in class.

Spending too much time on computers wasn’t helpful.

“There were ceiling effects of technology, and moderate use of technology appeared to have the best association with testing outcomes,” the report said. “This occurred across a number of grades, subjects, and reported computer activities.”

In fact, there’s a negative correlation between time spent on the computer during the school day and NAEP score on the 4th-grade reading NAEP.

That trend was somewhat present, although less clearly, on the 8th-grade reading NAEP.

“Overall usage of technology is probably not just not great, but actually can lower scores and testing for basic education [subjects like math, reading, science],” said Bouygues. “Even in the middle school, heavy use of technology does lower scores, but if you do have things that are specifically catered to a specific subject, that actually serves a purpose.”

For instance, she said her daughter, a chess enthusiast, has gotten help from digital sources in mastering the game. But asking kids to spend a chunk of every day typing on Microsoft Word, as some classrooms do in France, isn’t going to help teach higher-order thinking skills.

She cautioned though, that the report stops short of making a casual claim and saying that sitting in front of a laptop harms students’ ability to be critical thinkers. The researchers didn’t have the kind of evidence needed to be able to make that leap.

For more research on the impact of technology on student outcomes, take a look at these stories:

- Technology in Education: An Overview

- Computers + Collaboration = Student Learning, According to New Meta-Analysis

- Technology Has No Impact on Teaching and Learning (opinion)

Image: Getty

A version of this news article first appeared in the Digital Education blog.

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

The trend of ICT in education for critical thinking skills: A systematic literature review

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Reprints and Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Iik Nurhikmayati , Darhim Darhim; The trend of ICT in education for critical thinking skills: A systematic literature review. AIP Conf. Proc. 28 November 2023; 2909 (1): 040002. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0182604

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

ICT in education is gaining acceptance as a learning method that helps teachers and students achieve optimal learning objectives. ICT is believed to motivate and facilitate the learning process. Critical thinking skills, as one of the 21st-century skills, are known to be improved through ICT-based education. This article presents a systematic review of the literature published in the last five years and an indexed database of Springer and Eric. The results showed a total of 27 articles that met the criteria. Research findings on ICT trends in education for critical thinking skills are structured under three reports: (1) ICT trends in education include android, VR, AR, and coding; (2) the best strategy with ICT monitoring is distance learning, programming teaching, and STEM; and (3) other skills that are enhanced along with critical thinking skills are cognitive and affective skills, which are problem-solving, creativity and innovation, collaboration skills and communication skills. Based on this evidence, we make recommendations for future research to consider other types of ICT for enhancing critical thinking skills. In addition, using other learning strategies, such as problem-based learning and inquiry, can be considered to improve critical thinking skills.

Sign in via your Institution

Citing articles via, publish with us - request a quote.

Sign up for alerts

- Online ISSN 1551-7616

- Print ISSN 0094-243X

- For Researchers

- For Librarians

- For Advertisers

- Our Publishing Partners

- Physics Today

- Conference Proceedings

- Special Topics

pubs.aip.org

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Connect with AIP Publishing

This feature is available to subscribers only.

Sign In or Create an Account

Edtech Empire | Edtech Blog

Teaching Critical Thinking in the Digital Age

As technology becomes increasingly integrated into our daily lives, it is important to recognize its impact on education. The digital age presents both opportunities and challenges for educators, particularly when it comes to teaching critical thinking. In this blog post, we will explore the art of teaching critical thinking in the digital age and discuss some strategies for incorporating technology into the classroom.

Table of Contents

Understanding critical thinking, the importance of critical thinking, challenges of teaching critical thinking in the digital age, is technology producing a decline in critical thinking and analysis, how critical thinking is important to media and digital literacy, 1. encourage questioning, 2. use educational technology, 3. incorporate gamification, 4. teach ai prompt engineering, 5. incorporate technology into lesson plans, 6. encouraging active engagement with digital media, 7. teaching the art of questioning, 8. encouraging independent research, 9. fostering collaborative learning, teaching in the era of chatgpt, 1. analyzing and interpreting data, 2. evaluating arguments and evidence, 3. solving problems and making decisions, 4. generating hypotheses and testing them, 5. identifying patterns and relationships, 6. making connections between different ideas or concepts, q: what is critical thinking in the digital age, q: what is the art of critical thinking, q: what is digital critical thinking, q: what are the thinking skills in the digital age.

Critical thinking is a cognitive skill that involves the ability to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information to make reasoned and logical decisions. It is a multifaceted process that requires the individual to engage in independent and reflective thinking. Critical thinking involves asking questions, identifying assumptions, analyzing arguments, and drawing conclusions based on evidence.

It also involves the ability to identify biases and recognize the limitations of one’s knowledge and understanding. The development of critical thinking skills is crucial for individuals to navigate complex issues and make informed decisions in various aspects of life.

Furthermore, critical thinking is essential in the digital age where there is an abundance of information and misinformation, and individuals need to be able to analyze and evaluate digital content critically. The ability to think critically is a lifelong skill that is valuable in all aspects of life, including education, career, and personal relationships.

Critical thinking is a valuable skill that enables individuals to analyze information, make informed decisions, and solve complex problems. In today’s rapidly changing world, critical thinking is more important than ever. With the abundance of information available at our fingertips, it is essential that we teach students how to think critically so they can navigate this information landscape effectively. You may further check this article from futurelearn.com on the importance of critical thinking .

While technology can be a powerful tool for teaching critical thinking, it also presents some unique challenges. One of the biggest challenges is the overwhelming amount of information available online. With so much information, it can be difficult for students to determine what is credible and what is not. Additionally, technology can be a distraction, making it difficult for students to focus on the task at hand.

The use of technology has become ubiquitous in our daily lives, including in education. However, some have expressed concerns that technology is producing a decline in critical thinking and analysis skills. Critics argue that technology has made it easier for individuals to access information without having to engage in critical analysis, resulting in a generation of individuals who are more likely to accept information at face value without questioning its validity.

Additionally, the abundance of digital distractions, such as social media and video games, can lead to a lack of focus and decreased attention span, which may impede the development of critical thinking skills. However, others argue that technology can also be used as a tool to enhance critical thinking and analysis, as well as to provide access to a wealth of information that can be analyzed and evaluated.

Ultimately, the impact of technology on critical thinking and analysis is complex and multifaceted, and requires ongoing exploration and discussion.

Media and digital literacy are essential skills for navigating the digital landscape of the modern age. Critical thinking plays a crucial role in developing these skills, as it enables individuals to evaluate and analyze digital media content effectively. The ability to critically analyze media and digital content is particularly important in an era of fake news and misinformation, where it can be challenging to discern what is accurate and what is not.

Critical thinking allows individuals to identify biases and question the validity of information presented in digital media, enabling them to make informed decisions and form their opinions. It also enables individuals to understand the broader implications of digital media on society, including issues related to privacy, security, and ethical considerations.

Therefore, critical thinking is an essential component of media and digital literacy and is crucial for individuals to effectively engage with digital media in a responsible and informed manner. You may read more about this in this article titled, “ Enhancing critical thinking skills and media literacy in initial vocational education ”.

Strategies for Teaching Critical Thinking in the Digital Age

Despite the challenges, there are several strategies that educators can use to teach critical thinking in the digital age. Here are a few:

One of the most effective ways to teach critical thinking is to encourage students to ask questions. This can be done in a variety of ways, such as asking open-ended questions, posing hypothetical scenarios, and encouraging students to think deeply about the material they are studying. By asking questions, students are forced to think critically about the information they are learning and are better able to make connections between different concepts.

Educational technology can be a powerful tool for teaching critical thinking. For example, online discussion forums can be used to encourage students to engage with each other and share their ideas. Similarly, interactive simulations and virtual reality experiences can be used to help students understand complex concepts in a more engaging way. However, it is important to be aware of the potential downsides of technology, such as its impact on social relationships. (Learn more about this topic here: How Educational Technology Impacts Social Relationships ).

Gamification is the use of game-like elements in non-game contexts, such as education. By incorporating gamification into the classroom, educators can make learning more engaging and fun for students. For example, points, badges, and leaderboards can be used to motivate students to complete assignments and participate in class discussions. However, it is important to be aware of the challenges associated with gamification, such as the potential for students to become too focused on the rewards rather than the learning itself. (Learn more about gamification here: Gamification in Education: Benefits, Challenges, and Best Practices ).

As AI and machine learning become increasingly prevalent, it is important for students to understand how these technologies work and AI prompt engineering is the process of creating prompts that can be used to train machine learning models. By teaching students about AI prompt engineering , educators can help them understand how these technologies work and how they can be used in a variety of contexts. (Learn more about teaching AI prompt engineering here: Teaching AI Prompt Engineering to Students: Importance, Tips and Prospects ).

Technology can be a valuable tool for enhancing lesson plans and engaging students. For example, videos, podcasts, and other multimedia can be used to supplement traditional classroom materials. Similarly, online quizzes and assessments can be used to test students’ knowledge and provide immediate feedback. However, it is important to ensure that the technology is used in a meaningful way and does not distract from the learning objectives. (Learn more about incorporating technology into lesson plans here: How to Incorporate Technology into Lesson Plans )

Encouraging active engagement with digital media is essential for individuals to develop critical thinking skills and engage with digital content responsibly. Active engagement involves actively questioning, analyzing, and evaluating digital media content rather than passively consuming it.

It requires individuals to be proactive in seeking out diverse perspectives and sources of information to gain a comprehensive understanding of a topic. Teachers and educators can play a crucial role in encouraging active engagement by incorporating digital media literacy into their lesson plans and teaching students how to evaluate digital content critically.

Additionally, educators can encourage students to engage with digital media through interactive and collaborative activities such as online discussions, digital storytelling, and gamification. By actively engaging with digital media, individuals can develop the skills and knowledge necessary to make informed decisions and navigate the digital landscape effectively.

Teaching the art of questioning is an essential component of developing critical thinking skills. The ability to ask thoughtful and insightful questions is crucial for individuals to gain a deeper understanding of a topic, challenge assumptions, and make informed decisions. Effective questioning involves asking open-ended questions that prompt individuals to think critically and explore various perspectives.

Teachers and educators can teach the art of questioning by modeling effective questioning techniques, encouraging students to ask questions, and providing opportunities for students to practice asking questions.

Additionally, educators can teach students how to evaluate the quality of questions by examining factors such as relevance, complexity, and potential biases. By teaching the art of questioning, individuals can develop the skills necessary to engage in independent and reflective thinking, evaluate information critically, and make informed decisions.

Encouraging independent research is a crucial component of developing critical thinking skills in the digital age. Independent research involves seeking out information from diverse sources, evaluating the quality and relevance of information, and synthesizing information to form informed opinions and make informed decisions.

Teachers and educators can encourage independent research by providing students with opportunities to explore topics of interest, guiding students through the research process, and teaching students how to evaluate the credibility and reliability of sources. Additionally, educators can teach students how to use various digital tools and resources to conduct research effectively.

By encouraging independent research, individuals can develop the skills and knowledge necessary to navigate the digital landscape effectively, evaluate information critically, and make informed decisions.

Fostering collaborative learning is a crucial aspect of developing critical thinking skills in the digital age. Collaborative learning involves working together with peers to solve problems, share knowledge, and explore different perspectives.

Moreover, it encourages individuals to engage in active listening, communication, and teamwork, all of which are essential for developing critical thinking skills. Educators can foster collaborative learning by incorporating group projects, online discussions, and other interactive activities into their lesson plans.

These activities can help individuals develop their ability to work collaboratively and think critically while also promoting digital literacy and responsible use of technology. By fostering collaborative learning, educators can help individuals develop the skills necessary to navigate the digital landscape effectively, make informed decisions, and contribute to society.

As a language model trained by OpenAI, ChatGPT represents the cutting edge of artificial intelligence . While ChatGPT can be a valuable tool for education, it is important to remember that it is still a machine and cannot replace human teachers. Educators should use ChatGPT as a supplement to their teaching, rather than a replacement. (Learn more about teaching in the age of ChatGPT here: Teaching in the Age of ChatGPT ).

What Activities Can Teachers Incorporate to Develop Critical Thinking?

To analyze and interpret data, one must carefully scrutinize the data to uncover patterns, relationships, and trends. This can require critical thinking skills to determine what the data is telling us and how it can be used effectively. Additionally, students may need to look closely at the data to identify any correlations or discrepancies that can help them draw meaningful conclusions.

Evaluating arguments and evidence involves assessing the strength and reliability of the evidence and arguments presented in a text or other source. This can require critical thinking skills to determine whether the argument is logical and the evidence is valid. For example, students may need to assess the credibility of sources cited in an argument or evaluate the soundness of a particular claim.

Solving problems and making decisions requires students to identify problems, generate potential solutions, evaluate those solutions, and select the best option. This can require critical thinking skills to determine which solution is most effective or appropriate. For example, students might need to weigh the pros and cons of different solutions or consider how each solution would impact various stakeholders.

Generating hypotheses and testing them involves developing a hypothesis or prediction about a particular phenomenon and then testing it through experimentation or observation. This can require critical thinking skills to design experiments that will effectively test their hypotheses. However, students may need to consider different variables that could impact their results or develop alternative hypotheses if their initial predictions are not supported by their findings.

Identifying patterns and relationships requires students to recognize similarities and differences between different pieces of information or data. This can require critical thinking skills to identify patterns or relationships that are not immediately apparent. For example, students might need to compare data from different sources or identify common themes across different texts.

Making connections between different ideas or concepts involves linking various ideas or concepts together to create a more complete understanding of a particular topic. This can require critical thinking skills to identify connections between seemingly unrelated ideas. For example, students might need to consider how different historical events influenced each other or how various scientific concepts are related.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

A: Critical thinking in the digital age refers to the ability to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information in a rapidly changing technological landscape. It involves using a combination of logic, reasoning, and creativity to solve problems and make informed decisions.

A: The art of critical thinking involves the ability to question assumptions, think independently, and evaluate evidence objectively. Furthermore, It involves using a range of cognitive skills, including analysis, synthesis, evaluation, and interpretation, to make sound judgments and decisions.

A: Digital critical thinking refers to the application of critical thinking skills in the context of digital technology. It involves evaluating information sources, analyzing data, and making informed decisions based on digital information. Additionally, in today’s world, accessing and sharing more information digitally makes digital critical thinking skills increasingly important.

A: The thinking skills in the digital age include a range of cognitive abilities, including analytical thinking, creative thinking, problem-solving, decision-making, and information literacy. Additionally, these skills are essential for success in the rapidly changing technological landscape of the digital age.

Teaching critical thinking in the digital age presents both opportunities and challenges. By encouraging questioning, incorporating educational technology and gamification, teaching AI prompt engineering, and incorporating technology into lesson plans, educators can help students develop the critical thinking skills they need to succeed in today’s rapidly changing world. However, remember that using technology in a meaningful way and never replacing human teachers is important. By finding the right balance between technology and human interaction, we can ensure that students receive the best possible education.

Khondker Mohammad Shah-Al-Mamun is an experienced writer, technology integration and automation specialist, and Microsoft Innovative Educator who leads the Blended Learning Center at Daffodil International University in Bangladesh. He was also a Google Certified Educator and a leader of Google Educators Group (GEG) Dhaka South.

Khondker Mohammad Shah – Al – Mamun

Latest Posts

- Moodle LMS for Teachers: Your Essential Guide and FAQ

- Microsoft Paint is Now Equipped with AI

- Why You Shouldn’t Trust AI Detection Tools to Spot AI Writing

- Inclusive Education Using Technology: Empowering Every Learner

- ChatGPT Revolution: Why and How Education Must Keep Up

Sponsored Offer

Affiliate Link

- Edtech Career

- Edtech Reviews

- Edtech Tips

- Teaching Tips

- October 2023

- September 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

Popular Posts

Free Google Sites Templates for Teachers

Teaching in the Age of ChatGPT

How to Use Generative AI in Assessment

Top 10 Gamification Apps for Education

Teaching AI Prompt Engineering to Students: Importance, Tips and Prospects

Using ChatGPT in Education: Guide for Teachers

Best Free AI Content Detection Tools for Teachers

Effective ChatGPT Prompts for Teachers: A Comprehensive Guide

Top Free Metaverse Platforms for Teachers

How Educational Technology Impacts Social Relationships

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Our Mission

Helping Students Hone Their Critical Thinking Skills

Used consistently, these strategies can help middle and high school teachers guide students to improve much-needed skills.

Critical thinking skills are important in every discipline, at and beyond school. From managing money to choosing which candidates to vote for in elections to making difficult career choices, students need to be prepared to take in, synthesize, and act on new information in a world that is constantly changing.

While critical thinking might seem like an abstract idea that is tough to directly instruct, there are many engaging ways to help students strengthen these skills through active learning.

Make Time for Metacognitive Reflection

Create space for students to both reflect on their ideas and discuss the power of doing so. Show students how they can push back on their own thinking to analyze and question their assumptions. Students might ask themselves, “Why is this the best answer? What information supports my answer? What might someone with a counterargument say?”

Through this reflection, students and teachers (who can model reflecting on their own thinking) gain deeper understandings of their ideas and do a better job articulating their beliefs. In a world that is go-go-go, it is important to help students understand that it is OK to take a breath and think about their ideas before putting them out into the world. And taking time for reflection helps us more thoughtfully consider others’ ideas, too.

Teach Reasoning Skills

Reasoning skills are another key component of critical thinking, involving the abilities to think logically, evaluate evidence, identify assumptions, and analyze arguments. Students who learn how to use reasoning skills will be better equipped to make informed decisions, form and defend opinions, and solve problems.

One way to teach reasoning is to use problem-solving activities that require students to apply their skills to practical contexts. For example, give students a real problem to solve, and ask them to use reasoning skills to develop a solution. They can then present their solution and defend their reasoning to the class and engage in discussion about whether and how their thinking changed when listening to peers’ perspectives.

A great example I have seen involved students identifying an underutilized part of their school and creating a presentation about one way to redesign it. This project allowed students to feel a sense of connection to the problem and come up with creative solutions that could help others at school. For more examples, you might visit PBS’s Design Squad , a resource that brings to life real-world problem-solving.

Ask Open-Ended Questions

Moving beyond the repetition of facts, critical thinking requires students to take positions and explain their beliefs through research, evidence, and explanations of credibility.

When we pose open-ended questions, we create space for classroom discourse inclusive of diverse, perhaps opposing, ideas—grounds for rich exchanges that support deep thinking and analysis.

For example, “How would you approach the problem?” and “Where might you look to find resources to address this issue?” are two open-ended questions that position students to think less about the “right” answer and more about the variety of solutions that might already exist.

Journaling, whether digitally or physically in a notebook, is another great way to have students answer these open-ended prompts—giving them time to think and organize their thoughts before contributing to a conversation, which can ensure that more voices are heard.

Once students process in their journal, small group or whole class conversations help bring their ideas to life. Discovering similarities between answers helps reveal to students that they are not alone, which can encourage future participation in constructive civil discourse.

Teach Information Literacy

Education has moved far past the idea of “Be careful of what is on Wikipedia, because it might not be true.” With AI innovations making their way into classrooms, teachers know that informed readers must question everything.

Understanding what is and is not a reliable source and knowing how to vet information are important skills for students to build and utilize when making informed decisions. You might start by introducing the idea of bias: Articles, ads, memes, videos, and every other form of media can push an agenda that students may not see on the surface. Discuss credibility, subjectivity, and objectivity, and look at examples and nonexamples of trusted information to prepare students to be well-informed members of a democracy.

One of my favorite lessons is about the Pacific Northwest tree octopus . This project asks students to explore what appears to be a very real website that provides information on this supposedly endangered animal. It is a wonderful, albeit over-the-top, example of how something might look official even when untrue, revealing that we need critical thinking to break down “facts” and determine the validity of the information we consume.

A fun extension is to have students come up with their own website or newsletter about something going on in school that is untrue. Perhaps a change in dress code that requires everyone to wear their clothes inside out or a change to the lunch menu that will require students to eat brussels sprouts every day.

Giving students the ability to create their own falsified information can help them better identify it in other contexts. Understanding that information can be “too good to be true” can help them identify future falsehoods.

Provide Diverse Perspectives

Consider how to keep the classroom from becoming an echo chamber. If students come from the same community, they may have similar perspectives. And those who have differing perspectives may not feel comfortable sharing them in the face of an opposing majority.

To support varying viewpoints, bring diverse voices into the classroom as much as possible, especially when discussing current events. Use primary sources: videos from YouTube, essays and articles written by people who experienced current events firsthand, documentaries that dive deeply into topics that require some nuance, and any other resources that provide a varied look at topics.

I like to use the Smithsonian “OurStory” page , which shares a wide variety of stories from people in the United States. The page on Japanese American internment camps is very powerful because of its first-person perspectives.

Practice Makes Perfect

To make the above strategies and thinking routines a consistent part of your classroom, spread them out—and build upon them—over the course of the school year. You might challenge students with information and/or examples that require them to use their critical thinking skills; work these skills explicitly into lessons, projects, rubrics, and self-assessments; or have students practice identifying misinformation or unsupported arguments.

Critical thinking is not learned in isolation. It needs to be explored in English language arts, social studies, science, physical education, math. Every discipline requires students to take a careful look at something and find the best solution. Often, these skills are taken for granted, viewed as a by-product of a good education, but true critical thinking doesn’t just happen. It requires consistency and commitment.

In a moment when information and misinformation abound, and students must parse reams of information, it is imperative that we support and model critical thinking in the classroom to support the development of well-informed citizens.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Teaching critical thinking about health using digital technology in lower secondary schools in Rwanda: A qualitative context analysis

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Institute of Health and Society, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, School of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Rwanda, Kigali, Rwanda

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation School of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Rwanda, Kigali, Rwanda

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Institute of Health and Society, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, Tropical Institute of Community Health and Development, Kisumu, Kenya

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Institute of Health and Society, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, Department of Medicine, Makerere University, College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda

Affiliations Centre for Informed Health Choices, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo, Norway, Faculty of Health Sciences, Oslo Metropolitan University, Oslo, Norway

Affiliation Department of Medicine, Makerere University, College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda

Affiliation Tropical Institute of Community Health and Development, Kisumu, Kenya

Roles Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Centre for Informed Health Choices, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo, Norway, Health Systems Research Unit, South African Medical Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Centre for Informed Health Choices, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo, Norway

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

- Michael Mugisha,

- Anne Marie Uwitonze,

- Faith Chesire,

- Ronald Senyonga,

- Matt Oxman,

- Allen Nsangi,

- Daniel Semakula,

- Margaret Kaseje,

- Simon Lewin,

- Published: March 22, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248773

- Reader Comments

Introduction

Adolescents encounter misleading claims about health interventions that can affect their health. Young people need to develop critical thinking skills to enable them to verify health claims and make informed choices. Schools could teach these important life skills, but educators need access to suitable learning resources that are aligned with their curriculum. The overall objective of this context analysis was to explore conditions for teaching critical thinking about health interventions using digital technology to lower secondary school students in Rwanda.

We undertook a qualitative descriptive study using four methods: document review, key informant interviews, focus group discussions, and observations. We reviewed 29 documents related to the national curriculum and ICT conditions in secondary schools. We conducted 8 interviews and 5 focus group discussions with students, teachers, and policy makers. We observed ICT conditions and use in five schools. We analysed the data using a framework analysis approach.

Two major themes found. The first was demand for teaching critical thinking about health. The current curriculum explicitly aims to develop critical thinking competences in students. Critical thinking and health topics are taught across subjects. But understanding and teaching of critical thinking varies among teachers, and critical thinking about health is not being taught. The second theme was the current and expected ICT conditions. Most public schools have computers, projectors, and internet connectivity. However, use of ICT in teaching is limited, due in part to low computer to student ratios.

Conclusions

There is a need for learning resources to develop critical thinking skills generally and critical thinking about health specifically. Such skills could be taught within the existing curriculum using available ICT technologies. Digital resources for teaching critical thinking about health should be designed so that they can be used flexibly across subjects and easily by teachers and students.

Citation: Mugisha M, Uwitonze AM, Chesire F, Senyonga R, Oxman M, Nsangi A, et al. (2021) Teaching critical thinking about health using digital technology in lower secondary schools in Rwanda: A qualitative context analysis. PLoS ONE 16(3): e0248773. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248773

Editor: Gwo-Jen Hwang, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, TAIWAN

Received: February 1, 2021; Accepted: March 4, 2021; Published: March 22, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Mugisha et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data underlying the results presented in the study are available from Norwegian Data Center at http://nsddata.nsd.uib.no/webview/index.jsp?node=0&submode=ddi&study=http%3A%2F%2F129.177.90.161%3A80%2Fobj%2FfStudy%2FNSD2930&language=no&mode=documentation .

Funding: This research was funded by the Research Council of Norway ( https://www.forskningsradet.no/en/ ). Project number 284683, grant no:69006 awarded to ADO. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

We are confronted all the time with claims about the world. Many of these claims are not directly testable by most of us. We must figure out how to evaluate other people’s arguments to come to our own conclusions, particularly about causal claims [ 1 ]. Adolescents, like adults, encounter a wide range of health-related claims in their daily lives, and many of those are claims about health interventions, i.e., statements or messages about purported benefits or harms of actions people can take to protect or improve health. When confronted with such claims, most people are not trying to be scientists. Rather, they are trying to figure out what to believe and what to do.

Such claims are obtained from peers, families, the community, social and mass media. Misleading claims can lead to bad decisions about health, if they are believed. For example, there are endless claims about what people can do to prevent or treat COVID-19 [ 2 ]. Acting on unreliable claims can lead to unnecessary suffering and wasted resources [ 3 – 7 ]. Conversely, failure to believe and act on reliable claims about health interventions also leads to unnecessary suffering and inefficient use of health services [ 8 – 10 ].

Making good decisions about health depends on critical thinking, people’s ability to obtain, process and understand health information needed to make informed decisions [ 11 – 14 ]. Additionally, people need to think critically about health information, for instance to assess the trustworthiness of claims about health interventions or to understand how to deal with conflicting claims [ 15 ]. Many countries have moved towards competence-based curricula and include critical thinking as a key competence [ 16 , 17 ], although not specifically critical thinking about health. A strong case can be made for investing in health education for adolescents based on developmental science [ 18 ]. However, few educational interventions to improve adolescents’ ability to think critically about health have been evaluated rigorously [ 19 ].

We are a team developing and evaluating resources to enable young people to think critically about health claims. The team includes researchers from East Africa, where the resources are being developed and evaluated, as well as from Chile and Norway. The team is part of the Informed Health Choices (IHC) network, which includes researchers from over 20 countries who are developing and testing learning resources for primary and secondary schools [ 20 ].

We first identified key concepts (principles) that people need to understand and apply when deciding what health claims to believe and what to do [ 21 ]. Together with teachers in Uganda, we prioritised concepts that were relevant for primary school children [ 22 ]. We have also prioritised concepts for secondary schools, together with national curriculum committee members and teachers in Rwanda, Uganda, and Kenya [ 23 ]. We developed and tested learning resources in Ugandan primary school children [ 24 , 25 ]. In a follow up study, we showed that children retained what they had learned for at least one year [ 26 ]. The team has translated primary school learning resources to Kinyarwanda and Kiswahili and piloted their use in Rwanda and Kenya. Key findings from the Rwandan pilot study indicated that IHC resources were useful and feasible to use in Rwandan primary schools [ 27 ]. The primary school resources have also been translated to other languages, including Chinese, Croatian, French, Greek, Italian, Norwegian, Persian, Portuguese, Spanish and pilot testing of translated resources is ongoing in several countries [ 28 ].

In a process evaluation, researchers found that lack of time in the curriculum and printing costs were major challenges to scaling up use of the IHC primary school resources [ 29 ]. One way of reducing the cost of the intervention would be to use digital resources. Digital learning resources are much cheaper to distribute than printed resources because they eliminate printing costs, and they do not need to be physically shipped. However, schools may not be equipped to use digital resources and teachers and students may prefer printed learning materials. Further, we conducted a context analysis in Norway to explore the demand for teaching critical thinking about health in primary schools [ 30 ]. We found that although teachers were interested, there was little time available for teaching new content outside the curriculum and little time for teachers to seek out and test new resources.

Building on what we learned in our work with primary school resources, and in collaboration with stakeholders in education, we are developing digital learning resources for secondary school students in East Africa that can be easily adapted for use in other countries. To inform the development of the resources and ensure that they are well suited for the Rwandan context, we conducted a context analysis to explore 1) the demand for learning resources, 2) the extent to which these fit with the curriculum and 3) ICT conditions in secondary schools. Researchers in Kenya and Uganda carried out similar context analyses [ 31 – 33 ]. While our focus is on understanding the context for developing suitable learning resources for critical thinking about health, our findings can also inform the design of other digital learning resources in low resource educational settings.

We used a qualitative descriptive study approach [ 34 ]. This entails describing a phenomenon without moving far from or into the data; it requires less interpretation than an “interpretive descriptive” approach. We chose this method because the nature of the data we sought was primarily factual. We employed four qualitative methods: document review, key informant interviews, focus group discussions, and observations.

Document review

The document review included analysis of the existing curriculum, of approved learning resources in lower secondary schools, and of current documentation on ICT for education (ICT for education policy, ICT implementation plans, and guidelines for use of ICT in education). We searched for relevant documents on the official websites of the Rwanda Education Board (REB) and Ministry of Education. We consulted REB to retrieve and obtain clarifications of documents that could not be found on the official website. In total, we reviewed 29 documents for curriculum, resources and ICT use in Rwanda.

We reviewed the national curriculum for lower secondary schools. We read syllabuses for each subject taught in lower secondary schools. For each subject, we reviewed its rationale, competences, objectives, topic areas and units taught. We explored what health topics are covered in the curriculum and in which subjects and course units these health topics are located. We reviewed how critical thinking is generally covered in the curriculum and specifically in relation to health topics. We mapped if there were any IHC concepts and competences reflected in the curriculum. We used the IHC Key Concepts as a framework for reviewing the curriculum, mapping where in the curriculum IHC concepts are relevant explicitly or implicitly. The IHC Key Concepts includes 49 principles grouped in three categories, each with three high level concepts, and corresponding competences (see Table 1 ). We did not review international or special needs curricula used in Rwandan lower secondary schools.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248773.t001

We reviewed e-books approved by REB. We started by reviewing all books used in lower secondary schools of Rwanda. For each electronic book used in lower secondary schools, we reviewed whether the content included health topics or critical thinking about health.

We reviewed existing documentation on ICT use in secondary education, including existing national policy for use of ICT in education, and strategic and implementation plans for ICT in secondary schools. We also reviewed existing e-learning platforms and digital learning resources available through the REB gateway. We explored the status of the rolling out of ICT infrastructure in Rwandan secondary schools, and the availability of resources (equipment, Internet access, e-learning content, etc) in schools where ICT has been rolled out.

Key informant interviews

We interviewed key informants such as curriculum development and ICT for education at REB, secondary school teachers, and school ICT support officers. We explored how the competence-based curriculum is implemented in Rwanda, focusing on critical thinking and health topics, and how competence-based learning is evaluated. We asked secondary school teachers and ICT support officers at schools to describe how they teach competence-based curriculum with a focus on critical thinking and health related topics. We also explored ICT use for teaching and learning, and challenges using digital learning resources.

Focus group discussions

We conducted focus group discussions with students to explore how they obtain health information, what they use as a basis for making health decisions, and claims they hear in everyday life. We explored whether critical thinking about health is something they would be interested to learn in school. We also explored how they search for information about health and other topics at school. Finally, we explored how they access and use ICT for learning in school.

Observation

We visited selected schools and observed what ICT infrastructure is available and how it is used for teaching and learning. We observed existing ICT labs, digital equipment, Internet access, and content. Where we were able to access ongoing classes, we observed how ICT was used in teaching and learning.

First, we sampled documents to review according to the objectives. We purposively selected curriculum documents, approved learning resources and ICT policy and implementation documents (n = 29). For the curriculum and learning resources we selected those used in lower secondary schools in Rwanda. Second, we used convenience sampling to select five schools to conduct observations, interviews with teachers, and focus group discussions with students. Due to time and budget constraints, we applied convenience sampling to select five schools. We took care to choose schools that varied as much as possible in terms of ownership (private/public), day/boarding, equipment, and location (urban/rural). In each school, the school administration identified at least 10 students from lower secondary school with whom we conducted a focus group discussion. Two of the five focus group discussions were conducted out of school premises due to the Covid-19 pandemic. In each school, we purposively selected two to three teachers of biology and English because the current curriculum informed us that health topics were mainly taught in those subjects. We also interviewed people in charge of ICT at each school. Lastly, we purposively selected 5–10 key informants from REB’s departments of curriculum development and ICT for education. In order to capture the opinions, views and experiences of a wide range of participants, we selected participants that were of direct relevance to our study objectives.

Data collection procedures

For the document review, we used the study objectives and IHC Key Concepts as frameworks for collecting data. We extracted statements pertinent to each study objective. We summarised all findings in a single table, including the name of the document, the extracted statement, and the page number where the statement was found. This exercise was done independently by two researchers who then compared the data they extracted and resolved any disagreement through discussion.

For key informant interviews, we used semi-structured interview guides to collect information from the study participants, one for teachers and one for policy makers. Guides included questions that covered critical thinking about health, resources for teaching critical thinking, and ICT infrastructure used in teaching and learning. Guides also explored existing challenges and opportunities for using ICT for teaching and learning. We piloted the two interview guides with a few participants first and slightly modified them as needed. We interviewed participants face to face in a private place of their choice. Participants were encouraged to express their views freely and take discussion in a new relevant direction. We conducted some interviews with two or three teachers or REB key informants at the same time.

We also used an interview guide to conduct focus group discussions with students. We asked questions to explore how they learn to think critically, what claims about treatment effects they are familiar with, which sources of health information they use, and how they use ICT for learning purposes. We approached and conducted interviews at the workplace of study participants in a designated room that assured privacy of participants and recording of discussions. Interviews and focus group discussions were moderated by a male PhD fellow with Master of Public Health and experience qualitative research (first author). Each interview lasted at least an hour and the focus group discussion lasted between one hour and half. At least two researchers conducted each interview and focus group discussion. One person guided the discussion, and another took notes and recorded the discussion. Interviews and focus group discussions were recorded, transcribed verbatim and translated to English if the interview was conducted in Kinyarwanda. We collected observations using a checklist that covered ICT equipment, internet-connectivity, and e-learning content used in schools.

The amount of data we collected was guided by considerations of the variation in issues emerging from the data and the extent to which we were able to explain these variations. We considered our time and resource constraints and the need to avoid large volumes of data that cannot be easily managed or analysed as highlighted in the literature [ 35 , 36 ].

Data analysis

We compiled and analysed all data from the document review, key informant interviews, focus group discussions, and observations together, using a framework analysis approach for applied research [ 37 ]. This approach differs from thematic content analysis in that it is deductive in nature with pre-set objectives [ 38 ]. It also involves analysing, classifying and summarising data in a thematic framework [ 39 ]. We began by reading all notes, transcripts, and documents to familiarise ourselves with the data. Then we conducted an analysis based on a coding scheme of initial themes derived directly from the objectives of our study: 1) demand for learning resources to teach critical thinking about health, 2) links between critical thinking about health and the curriculum, and 3) current and expected ICT conditions for teaching and learning in secondary schools. We determined sub-themes from data within each initial theme. We indexed all the data using the initial themes and sub-themes and rearranged data within and across themes (charting) to compare summaries of data during analysis. Two researchers independently analysed the data and compared their findings. The two researchers discussed disagreements in codes and themes and agreed on the final themes.

We summarized the key findings and assessed our confidence in these using a version of the Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (GRADE-CERQual) approach [ 40 ]. GRADE-CERQual was modified for primary qualitative studies [ 29 , 41 ]. GRADE-CERQual is a systematic and transparent method for assessing the confidence in evidence from reviews of qualitative research through the lens of four components: methodological limitations, data adequacy, coherence and relevance [ 42 ]. Although CERQual has been designed for assessing findings emerging from qualitative evidence syntheses, the components of the approach are also suitable for assessing findings from a single study with multiple sources of qualitative data. We modified the components slightly as follows: 1) Methodological limitations: the extent to which there are concerns about the sampling and collection of the data that contributed evidence to an individual finding, 2) Coherence of the finding: an assessment of how clear and compelling the fit is between the data and the finding that brings together these data, 3) Adequacy of the data contributing to a finding: an overall determination of the degree of richness and quantity of data supporting a finding and 4) Relevance: the extent to which the body of evidence supporting a finding is applicable to the context (perspective or population, phenomenon of interest, setting) specified in the study question.