- SpringerLink shop

Types of journal articles

It is helpful to familiarise yourself with the different types of articles published by journals. Although it may appear there are a large number of types of articles published due to the wide variety of names they are published under, most articles published are one of the following types; Original Research, Review Articles, Short reports or Letters, Case Studies, Methodologies.

Original Research:

This is the most common type of journal manuscript used to publish full reports of data from research. It may be called an Original Article, Research Article, Research, or just Article, depending on the journal. The Original Research format is suitable for many different fields and different types of studies. It includes full Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion sections.

Short reports or Letters:

These papers communicate brief reports of data from original research that editors believe will be interesting to many researchers, and that will likely stimulate further research in the field. As they are relatively short the format is useful for scientists with results that are time sensitive (for example, those in highly competitive or quickly-changing disciplines). This format often has strict length limits, so some experimental details may not be published until the authors write a full Original Research manuscript. These papers are also sometimes called Brief communications .

Review Articles:

Review Articles provide a comprehensive summary of research on a certain topic, and a perspective on the state of the field and where it is heading. They are often written by leaders in a particular discipline after invitation from the editors of a journal. Reviews are often widely read (for example, by researchers looking for a full introduction to a field) and highly cited. Reviews commonly cite approximately 100 primary research articles.

TIP: If you would like to write a Review but have not been invited by a journal, be sure to check the journal website as some journals to not consider unsolicited Reviews. If the website does not mention whether Reviews are commissioned it is wise to send a pre-submission enquiry letter to the journal editor to propose your Review manuscript before you spend time writing it.

Case Studies:

These articles report specific instances of interesting phenomena. A goal of Case Studies is to make other researchers aware of the possibility that a specific phenomenon might occur. This type of study is often used in medicine to report the occurrence of previously unknown or emerging pathologies.

Methodologies or Methods

These articles present a new experimental method, test or procedure. The method described may either be completely new, or may offer a better version of an existing method. The article should describe a demonstrable advance on what is currently available.

Back │ Next

- Hirsh Health Sciences

- Webster Veterinary

Guide to Scholarly Articles

- What is a Scholarly Article?

- Scholarly vs. Popular vs. Trade Articles

Types of Scholarly Articles

Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods articles, why does this matter.

- Anatomy of Scholarly Articles

- Tips for Reading Scholarly Articles

Scholarly articles come in many different formats each with their own function in the scholarly conversation. The following are a few of the major types of scholarly articles you are likely to encounter as you become a part of the conversation. Identifying the different types of scholarly articles and knowing their function will help you become a better researcher.

Original/Empirical Studies

- Note: Empirical studies can be subdivided into qualitative studies, quantitative studies, or mixed methods studies. See below for more information

- Usefulness for research: Empirical studies are useful because they provide current original research on a topic which may contain a hypothesis or interpretation to advance or to disprove.

Literature Reviews

- Distinguishing characteristic: Literature reviews survey and analyze a clearly delaminated body of scholarly literature.

- Usefulness for research: Literature reviews are useful as a way to quickly get up to date on a particular topic of research.

Theoretical Articles

- Distinguishing characteristic: Theoretical articles draw on existing scholarship to improve upon or offer a new theoretical perspective on a given topic.

- Usefulness for research: Theoretical articles are useful because they provide a theoretical framework you can apply to your own research.

Methodological Articles

- Distinguishing characteristic: Methodological articles draw on existing scholarship to improve or offer new methodologies for exploring a given topic.

- Usefulness for research: Methodological articles are useful because they provide a methodologies you can apply to your own research.

Case Studies

- Distinguishing characteristic: Case studies focus on individual examples or instances of a phenomenon to illustrate a research problem or a a solution to a research problem.

- Usefulness for research: Case studies are useful because they provide information about a research problem or data for analysis.

Book Reviews

- Distinguishing characteristic: Book reviews provide summaries and evaluations of individual books.

- Usefulness for research: Book reviews are useful because they provide summaries and evaluations of individual books relevant to your research.

Adapted from the Publication manual of the American Psychological Association : the official guide to APA style. (Sixth edition.). (2013). American Psychological Association.

Qualitative articles ask "why" questions where as quantitative articles ask "how many/how much?" questions. These approaches are are not mutually exclusive. In fact, many articles combine the two in a mixed-methods approach.

We can think of these different kinds of scholarly articles as different tools designed for different tasks. What research task do you need to accomplish? Do you need to get up to date on a give topic? Find a literature review. Do you need to find a hypothesis to test or to extend? Find an empirical study. Do you need to explore methodologies? Find a methodological article.

- << Previous: Scholarly vs. Popular vs. Trade Articles

- Next: Anatomy of Scholarly Articles >>

- Last Updated: Aug 23, 2023 8:53 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.tufts.edu/scholarly-articles

- Richard G. Trefry Library

Q. What's the difference between a research article (or research study) and a review article?

- Course-Specific

- Textbooks & Course Materials

- Tutoring & Classroom Help

- Writing & Citing

- 44 Articles & Journals

- 3 Artificial Intelligence

- 11 Capstone/Thesis/Dissertation Research

- 37 Databases

- 56 Information Literacy

- 9 Interlibrary Loan

- 9 Need help getting started?

- 22 Technical Help

Answered By: Priscilla Coulter Last Updated: Jul 29, 2022 Views: 232119

A research paper is a primary source ...that is, it reports the methods and results of an original study performed by the authors . The kind of study may vary (it could have been an experiment, survey, interview, etc.), but in all cases, raw data have been collected and analyzed by the authors , and conclusions drawn from the results of that analysis.

Research papers follow a particular format. Look for:

- A brief introduction will often include a review of the existing literature on the topic studied, and explain the rationale of the author's study. This is important because it demonstrates that the authors are aware of existing studies, and are planning to contribute to this existing body of research in a meaningful way (that is, they're not just doing what others have already done).

- A methods section, where authors describe how they collected and analyzed data. Statistical analyses are included. This section is quite detailed, as it's important that other researchers be able to verify and/or replicate these methods.

- A results section describes the outcomes of the data analysis. Charts and graphs illustrating the results are typically included.

- In the discussion , authors will explain their interpretation of their results and theorize on their importance to existing and future research.

- References or works cited are always included. These are the articles and books that the authors drew upon to plan their study and to support their discussion.

You can use the library's article databases to search for research articles:

- A research article will nearly always be published in a peer-reviewed journal; click here for instructions on limiting your searches to peer-reviewed articles.

- If you have a particular type of study in mind, you can include keywords to describe it in your search . For instance, if you would like to see studies that used surveys to collect data, you can add "survey" to your topic in the database's search box. See this example search in our EBSCO databases: " bullying and survey ".

- Several of our databases have special limiting options that allow you to select specific methodologies. See, for instance, the " Methodology " box in ProQuest's PsycARTICLES Advanced Search (scroll down a bit to see it). It includes options like "Empirical Study" and "Qualitative Study", among many others.

A review article is a secondary source ...it is written about other articles, and does not report original research of its own. Review articles are very important, as they draw upon the articles that they review to suggest new research directions, to strengthen support for existing theories and/or identify patterns among exising research studies. For student researchers, review articles provide a great overview of the existing literature on a topic. If you find a literature review that fits your topic, take a look at its references/works cited list for leads on other relevant articles and books!

You can use the library's article databases to find literature reviews as well! Click here for tips.

- Share on Facebook

Was this helpful? Yes 7 No 0

Related Topics

- Articles & Journals

- Information Literacy

Need personalized help? Librarians are available 365 days/nights per year! See our schedule.

Learn more about how librarians can help you succeed.

- SUNY Oswego, Penfield Library

- Resource Guides

Biological Sciences Research Guide

Primary research vs review article.

- Research Starters

- Citing Sources

- Open Educational Resources

- Peer Review

- How to Read a Scientific Article

- Conducting a Literature Review

- Interlibrary Loan

Quick Links

- Penfield Library

- Research Guides

- A-Z List of Databases & Indexes

Characteristics of a Primary Research Article

- Goal is to present the result of original research that makes a new contribution to the body of knowledge

- Sometimes referred to as an empirical research article

- Typically organized into sections that include: Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion/Conclusion, and References.

Example of a Primary Research Article:

Flockhart, D.T.T., Fitz-gerald, B., Brower, L.P., Derbyshire, R., Altizer, S., Hobson, K.A., … Norris, D.R., (2017). Migration distance as a selective episode for wing morphology in a migratory insect. Movement Ecology , 5(1), 1-9. doi: doi.org/10.1186/s40462-017-0098-9

Characteristics of a Review Article

- Goal is to summarize important research on a particular topic and to represent the current body of knowledge about that topic.

- Not intended to provide original research but to help draw connections between research studies that have previously been published.

- Help the reader understand how current understanding of a topic has developed over time and identify gaps or inconsistencies that need further exploration.

Example of a Review Article:

https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezproxy.oswego.edu/science/article/pii/S0960982218302537

- << Previous: Plagiarism

- Next: Peer Review >>

Understanding Scientific Journals and Articles: How to approach reading journal articles

by Anthony Carpi, Ph.D., Anne E. Egger, Ph.D., Natalie H. Kuldell

Listen to this reading

Did you know that scientific literature goes all the way back to 600 BCE? Although scientific articles have changed some – for example, Isaac Newton wrote about the fun he had with prisms in a 1672 scientific article – the basics remain the same. This ensures that published research becomes part of the archive of scientific knowledge upon which other scientists can build.

Scientists make their research available to the community by publishing it in scientific journals.

In scientific papers, scientists explain the research that they are building on, their research methods, data and data analysis techniques, and their interpretation of the data.

Understanding how to read scientific papers is a critical skill for scientists and students of science.

We've all read the headlines at the supermarket checkout line: "Aliens Abduct New Jersey School Teacher" or "Quadruplets Born to 99-Year-Old Woman: Exclusive Photos Inside." Journals like the National Enquirer sell copies by publishing sensational headlines, and most readers believe only a fraction of what is printed. A person more interested in news than gossip could buy a publication like Time, Newsweek or Discover . These magazines publish information on current news and events, including recent scientific advances. These are not original reports of scientific research , however. In fact, most of these stories include phrases like, "A group of scientists recently published their findings on..." So where do scientists publish their findings?

Scientists publish their original research in scientific journals, which are fundamentally different from news magazines. The articles in scientific journals are not written by journalists – they are written by scientists. Scientific articles are not sensational stories intended to entertain the reader with an amazing discovery, nor are they news stories intended to summarize recent scientific events, nor even records of every successful and unsuccessful research venture. Instead, scientists write articles to describe their findings to the community in a transparent manner.

- Scientific journals vs. popular media

Within a scientific article, scientists present their research questions, the methods by which the question was approached, and the results they achieved using those methods. In addition, they present their analysis of the data and describe some of the interpretations and implications of their work. Because these articles report new work for the first time, they are called primary literature . In contrast, articles or news stories that review or report on scientific research already published elsewhere are referred to as secondary .

The articles in scientific journals are different from news articles in another way – they must undergo a process called peer review , in which other scientists (the professional peers of the authors) evaluate the quality and merit of research before recommending whether or not it should be published (see our Peer Review module). This is a much lengthier and more rigorous process than the editing and fact-checking that goes on at news organizations. The reason for this thorough evaluation by peers is that a scientific article is more than a snapshot of what is going on at a certain time in a scientist's research. Instead, it is a part of what is collectively called the scientific literature, a global archive of scientific knowledge. When published, each article expands the library of scientific literature available to all scientists and contributes to the overall knowledge base of the discipline of science.

Comprehension Checkpoint

- Scientific journals: Degrees of specialization

Figure 1: Nature : An example of a scientific journal.

There are thousands of scientific journals that publish research articles. These journals are diverse and can be distinguished according to their field of specialization. Among the most broadly targeted and competitive are journals like Cell , the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), Nature , and Science that all publish a wide variety of research articles (see Figure 1 for an example). Cell focuses on all areas of biology, NEJM on medicine, and both Science and Nature publish articles in all areas of science. Scientists submit manuscripts for publication in these journals when they feel their work deserves the broadest possible audience.

Just below these journals in terms of their reach are the top-tier disciplinary journals like Analytical Chemistry, Applied Geochemistry, Neuron, Journal of Geophysical Research , and many others. These journals tend to publish broad-based research focused on specific disciplines, such as chemistry, geology, neurology, nuclear physics, etc.

Next in line are highly specialized journals, such as the American Journal of Potato Research, Grass and Forage Science, the Journal of Shellfish Research, Neuropeptides, Paleolimnology , and many more. While the research published in various journals does not differ in terms of the quality or the rigor of the science described, it does differ in its degree of specialization: These journals tend to be more specialized, and thus appeal to a more limited audience.

All of these journals play a critical role in the advancement of science and dissemination of information (see our Utilizing the Scientific Literature module for more information). However, to understand how science is disseminated through these journals, you must first understand how the articles themselves are formatted and what information they contain. While some details about format vary between journals and even between articles in the same journal, there are broad characteristics that all scientific journal articles share.

- The standard format of journal articles

In June of 2005, the journal Science published a research report on a sighting of the ivory-billed woodpecker, a bird long considered extinct in North America (Fitzpatrick et al., 2005). The work was of such significance and broad interest that it was displayed prominently on the cover (Figure 2) and highlighted by an editorial at the front of the journal (Kennedy, 2005). The authors were aware that their findings were likely to be controversial, and they worked especially hard to make their writing clear. Although the article has no headings within the text, it can easily be divided into sections:

Figure 2: A picture of the cover of Science from June 3, 2005.

Title and authors: The title of a scientific article should concisely and accurately summarize the research . Here, the title used is "Ivory-billed Woodpecker ( Campephilus principalis ) Persists in North America." While it is meant to capture attention, journals avoid using misleading or overly sensational titles (you can imagine that a tabloid might use the headline "Long-dead Giant Bird Attacks Canoeists!"). The names of all scientific contributors are listed as authors immediately after the title. You may be used to seeing one or maybe two authors for a book or newspaper article, but this article has seventeen authors! It's unlikely that all seventeen of those authors sat down in a room and wrote the manuscript together. Instead, the authorship reflects the distribution of the workload and responsibility for the research, in addition to the writing. By convention, the scientist who performed most of the work described in the article is listed first, and it is likely that the first author did most of the writing. Other authors had different contributions; for example, Gene Sparling is the person who originally spotted the bird in Arkansas and was subsequently contacted by the scientists at the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. In some cases, but not in the woodpecker article, the last author listed is the senior researcher on the project, or the scientist from whose lab the project originated. Increasingly, journals are requesting that authors detail their exact contributions to the research and writing associated with a particular study.

Abstract: The abstract is the first part of the article that appears right after the listing of authors in an article. In it, the authors briefly describe the research question, the general methods , and the major findings and implications of the work. Providing a summary like this at the beginning of an article serves two purposes: First, it gives readers a way to decide whether the article in question discusses research that interests them, and second, it is entered into literature databases as a means of providing more information to people doing scientific literature searches. For both purposes, it is important to have a short version of the full story. In this case, all of the critical information about the timing of the study, the type of data collected, and the potential interpretations of the findings is captured in four straightforward sentences as seen below:

The ivory-billed woodpecker ( Campephilus principalis ), long suspected to be extinct, has been rediscovered in the Big Woods region of eastern Arkansas. Visual encounters during 2004 and 2005, and analysis of a video clip from April 2004, confirm the existence of at least one male. Acoustic signatures consistent with Campephilus display drums also have been heard from the region. Extensive efforts to find birds away from the primary encounter site remain unsuccessful, but potential habitat for a thinly distributed source population is vast (over 220,000 hectares).

Introduction: The central research question and important background information are presented in the introduction. Because science is a process that builds on previous findings, relevant and established scientific knowledge is cited in this section and then listed in the References section at the end of the article. In many articles, a heading is used to set this and subsequent sections apart, but in the woodpecker article the introduction consists of the first three paragraphs, in which the history of the decline of the woodpecker and previous studies are cited. The introduction is intended to lead the reader to understand the authors' hypothesis and means of testing it. In addition, the introduction provides an opportunity for the authors to show that they are aware of the work that scientists have done before them and how their results fit in, explicitly building on existing knowledge.

Materials and methods: In this section, the authors describe the research methods they used (see The Practice of Science module for more information on these methods). All procedures, equipment, measurement parameters , etc. are described in detail sufficient for another researcher to evaluate and/or reproduce the research. In addition, authors explain the sources of error and procedures employed to reduce and measure the uncertainty in their data (see our Uncertainty, Error, and Confidence module). The detail given here allows other scientists to evaluate the quality of the data collected. This section varies dramatically depending on the type of research done. In an experimental study, the experimental set-up and procedure would be described in detail, including the variables , controls , and treatment . The woodpecker study used a descriptive research approach, and the materials and methods section is quite short, including the means by which the bird was initially spotted (on a kayaking trip) and later photographed and videotaped.

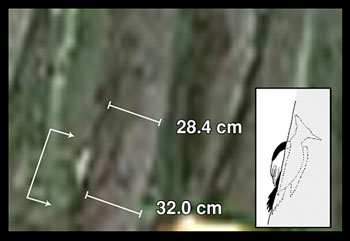

Results: The data collected during the research are presented in this section, both in written form and using tables, graphs, and figures (see our Using Graphs and Visual Data module). In addition, all statistical and data analysis techniques used are presented (see our Statistics in Science module). Importantly, the data should be presented separately from any interpretation by the authors. This separation of data from interpretation serves two purposes: First, it gives other scientists the opportunity to evaluate the quality of the actual data, and second, it allows others to develop their own interpretations of the findings based on their background knowledge and experience. In the woodpecker article, the data consist largely of photographs and videos (see Figure 3 for an example). The authors include both the raw data (the photograph) and their analysis (the measurement of the tree trunk and inferred length of the bird perched on the trunk). The sketch of the bird on the right-hand side of the photograph is also a form of analysis, in which the authors have simplified the photograph to highlight the features of interest. Keeping the raw data (in the form of a photograph) facilitated reanalysis by other scientists: In early 2006, a team of researchers led by the American ornithologist David Sibley reanalyzed the photograph in Figure 3 and came to the conclusion that the bird was not an ivory-billed woodpecker after all (Sibley et al, 2006).

Figure 3: An example of the data presented in the Ivory-billed woodpecker article (Fitzpatrick et al ., 2005, Figure 1).

Discussion and conclusions: In this section, authors present their interpretation of the data , often including a model or idea they feel best explains their results. They also present the strengths and significance of their work. Naturally, this is the most subjective section of a scientific research article as it presents interpretation as opposed to strictly methods and data, but it is not speculation by the authors. Instead, this is where the authors combine their experience, background knowledge, and creativity to explain the data and use the data as evidence in their interpretation (see our Data Analysis and Interpretation module). Often, the discussion section includes several possible explanations or interpretations of the data; the authors may then describe why they support one particular interpretation over the others. This is not just a process of hedging their bets – this how scientists say to their peers that they have done their homework and that there is more than one possible explanation. In the woodpecker article, for example, the authors go to great lengths to describe why they believe the bird they saw is an ivory-billed woodpecker rather than a variant of the more common pileated woodpecker, knowing that this is a likely potential rebuttal to their initial findings. A final component of the conclusions involves placing the current work back into a larger context by discussing the implications of the work. The authors of the woodpecker article do so by discussing the nature of the woodpecker habitat and how it might be better preserved.

In many articles, the results and discussion sections are combined, but regardless, the data are initially presented without interpretation .

References: Scientific progress requires building on existing knowledge, and previous findings are recognized by directly citing them in any new work. The citations are collected in one list, commonly called "References," although the precise format for each journal varies considerably. The reference list may seem like something you don't actually read, but in fact it can provide a wealth of information about whether the authors are citing the most recent work in their field or whether they are biased in their citations towards certain institutions or authors. In addition, the reference section provides readers of the article with more information about the particular research topic discussed. The reference list for the woodpecker article includes a wide variety of sources that includes books, other journal articles, and personal accounts of bird sightings.

Supporting material: Increasingly, journals make supporting material that does not fit into the article itself – like extensive data tables, detailed descriptions of methods , figures, and animations – available online. In this case, the video footage shot by the authors is available online, along with several other resources.

- Reading the primary literature

The format of a scientific article may seem overly structured compared to many other things you read, but it serves a purpose by providing an archive of scientific research in the primary literature that we can build on. Though isolated examples of that archive go as far back as 600 BCE (see the Babylonian tablets in our Description in Scientific Research module), the first consistently published scientific journal was the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London , edited by Henry Oldenburg for the Royal Society beginning in 1666 (see our Scientific Institutions and Societies module). These early scientific writings include all of the components listed above, but the writing style is surprisingly different than a modern journal article. For example, Isaac Newton opened his 1672 article "New Theory About Light and Colours" with the following:

I shall without further ceremony acquaint you, that in the beginning of the Year 1666...I procured me a Triangular glass-Prisme, to try therewith the celebrated Phenomena of Colours . And in order thereto having darkened my chamber, and made a small hole in my window-shuts, to let in a convenient quantity of the Suns light, I placed my Prisme at his entrance, that it might be thereby refracted to the opposite wall. It was at first a very pleasing divertissement, to view the vivid and intense colours produced thereby; but after a while applying my self to consider them more circumspectly, I became surprised to see them in an oblong form; which, according to the received laws of Refraction, I expected should have been circular . (Newton, 1672)

Figure 4: Isaac Newton described the rainbow produced by a prism as a "pleasing divertissement."

Newton describes his materials and methods in the first few sentences ("... a small hole in my window-shuts"), describes his results ("an oblong form"), refers to the work that has come before him ("the received laws of Refraction"), and highlights how his results differ from his expectations. Today, however, Newton 's statement that the "colours" produced were a "very pleasing divertissement" would be out of place in a scientific article (Figure 4). Much more typically, modern scientific articles are written in an objective tone, typically without statements of personal opinion to avoid any appearance of bias in the interpretation of their results. Unfortunately, this tone often results in overuse of the passive voice, with statements like "a Triangular glass-Prisme was procured" instead of the wording Newton chose: "I procured me a Triangular glass-Prisme." The removal of the first person entirely from the articles reinforces the misconception that science is impersonal, boring, and void of creativity, lacking the enjoyment and surprise described by Newton. The tone can sometimes be misleading if the study involves many authors, making it unclear who did what work. The best scientific writers are able to both present their work in an objective tone and make their own contributions clear.

The scholarly vocabulary in scientific articles can be another obstacle to reading the primary literature. Materials and Methods sections often are highly technical in nature and can be confusing if you are not intimately familiar with the type of research being conducted. There is a reason for all of this vocabulary, however: An explicit, technical description of materials and methods provides a means for other scientists to evaluate the quality of the data presented and can often provide insight to scientists on how to replicate or extend the research described.

The tone and specialized vocabulary of the modern scientific article can make it hard to read, but understanding the purpose and requirements for each section can help you decipher the primary literature. Learning to read scientific articles is a skill, and like any other skill, it requires practice and experience to master. It is not, however, an impossible task.

Strange as it seems, the most efficient way to tackle a new article may be through a piecemeal approach, reading some but not all the sections and not necessarily in their order of appearance. For example, the abstract of an article will summarize its key points, but this section can often be dense and difficult to understand. Sometimes the end of the article may be a better place to start reading. In many cases, authors present a model that fits their data in this last section of the article. The discussion section may emphasize some themes or ideas that tie the story together, giving the reader some foundation for reading the article from the beginning. Even experienced scientists read articles this way – skimming the figures first, perhaps, or reading the discussion and then going back to the results. Often, it takes a scientist multiple readings to truly understand the authors' work and incorporate it into their personal knowledge base in order to build on that knowledge.

- Building knowledge and facilitating discussion

The process of science does not stop with the publication of the results of research in a scientific article. In fact, in some ways, publication is just the beginning. Scientific journals also provide a means for other scientists to respond to the work they publish; like many newspapers and magazines, most scientific journals publish letters from their readers.

Unlike the common "Letters to the Editor" of a newspaper, however, the letters in scientific journals are usually critical responses to the authors of a research study in which alternative interpretations are outlined. When such a letter is received by a journal editor, it is typically given to the original authors so that they can respond, and both the letter and response are published together. Nine months after the original publication of the woodpecker article, Science published a letter (called a "Comment") from David Sibley and three of his colleagues, who reinterpreted the Fitzpatrick team's data and concluded that the bird in question was a more common pileated woodpecker, not an ivory-billed woodpecker (Sibley et al., 2006). The team from the Cornell lab wrote a response supporting their initial conclusions, and Sibley's team followed that up with a response of their own in 2007 (Fitzpatrick et al., 2006; Sibley at al., 2007). As expected, the research has generated significant scientific controversy and, in addition, has captured the attention of the public, spreading the story of the controversy into the popular media.

For more information about this story see The Case of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker module.

Table of Contents

Activate glossary term highlighting to easily identify key terms within the module. Once highlighted, you can click on these terms to view their definitions.

Activate NGSS annotations to easily identify NGSS standards within the module. Once highlighted, you can click on them to view these standards.

Biological Literature: Research vs Review Articles

- The Scientific Method Explained

- Parts of a Scientific Article

- How to Read Scientific Articles

- Research vs Review Articles

- Quantitative vs Qualitative Research

- How do I find a Quantitative article?

- Find Books/eBooks

- Linking Google Scholar to Gee Library Resources

- Related Websites

- Evaluating Resources

- Documenting Sources (Citations)

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Choosing Your Topic This link opens in a new window

- Creating a Literature Review

- Related Guides

- Library Session Materials

Research Articles

A research article describes an original study that the author(s) conducted themselves.

It will include a brief literature review, but the main focus of the article is to describe the theoretical approach, methods, and results of the authors' own study.

Look at the abstract or full text of the journal article and look for the following:

- Was data collected?

- Were there surveys, questionnaires, interviews, interventions (as in a clinical trial)?

- Is there a population?

- Is there an outline of the methodology used?

- Are there findings or results?

- Are there conclusions and a discussion of the significance?

A research article has a hypothesis, a method for testing the hypothesis, a population on which the hypothesis was tested, results or findings, and a discussion or conclusion.

Review Articles

Review articles summarize the current state of research on a subject by organizing, synthesizing, and critically evaluating the relevant literature. They tell what is currently known about an area under study and place what is known in context. This allows the researcher to see how their particular study fits into a larger picture. Review articles are not original research articles. Instead, they are a summary of many other original research articles. When your instructor tells you to obtain an "original research article" or to use a primary source, do not use an article that says review. Review articles may include a bibliography that will lead you back to the primary research reported in the article.

Systematic Review Articles

A systematic review is an appraisal and synthesis of primary research papers using a rigorous and clearly documented methodology in both the search strategy and the selection of studies. This minimizes bias in the results. The clear documentation of the process and the decisions made allow the review to be reproduced and updated.

Characteristics of a Systematic Review

- A clearly stated set of objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies

- An explicit, reproducible methodology

- A systematic search that attempts to identify all studies that would meet the eligibility criteria

- An assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies, for example through the assessment of risk of bias

- A systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies.

- << Previous: How to Read Scientific Articles

- Next: Quantitative vs Qualitative Research >>

- Last Updated: Oct 3, 2022 2:30 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mssu.edu/c.php?g=865170

This site is maintained by the librarians of George A. Spiva Library . If you have a question or comment about the Library's LibGuides, please contact the site administrator .

- Privacy Policy

Home » Review Article vs Research Article

Review Article vs Research Article

Table of Contents

Review articles and Research Articles are two different types of scholarly publications that serve distinct purposes in the academic literature.

Research Articles

A Research Article is a primary source that presents original research findings based on a specific research question or hypothesis. These articles typically follow a standard format that includes an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion sections. Research articles often include detailed descriptions of the research design, data collection and analysis procedures, and the results of statistical tests. These articles are typically peer-reviewed to ensure that they meet rigorous scientific standards before publication.

Review Articles

A Review Article is a secondary source that summarizes and analyzes existing research on a particular topic or research question. These articles provide an overview of the current state of knowledge on a particular topic, including a critical analysis of the strengths and limitations of previous research. Review articles often include a meta-analysis of the existing literature, which involves combining and analyzing data from multiple studies to draw more general conclusions about the research question or topic. Review articles are also typically peer-reviewed to ensure that they are comprehensive, accurate, and up-to-date.

Difference Between Review Article and Research Article

Here are some key differences between review articles and research articles:

In summary, research articles and review articles serve different purposes in the academic literature. Research articles present original research findings based on a specific research question or hypothesis, while review articles summarize and analyze existing research on a particular topic or research question. Both types of articles are typically peer-reviewed to ensure that they meet high standards of scientific rigor and accuracy.

Also see Research Methods

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Inductive Vs Deductive Research

Exploratory Vs Explanatory Research

Basic Vs Applied Research

Generative Vs Evaluative Research

Reliability Vs Validity

Longitudinal Vs Cross-Sectional Research

Maxwell Library | Bridgewater State University

Today's Hours:

- Maxwell Library

- Scholarly Journals and Popular Magazines

- Differences in Research, Review, and Opinion Articles

Scholarly Journals and Popular Magazines: Differences in Research, Review, and Opinion Articles

- Where Do I Start?

- How Do I Find Peer-Reviewed Articles?

- How Do I Compare Periodical Types?

- Where Can I find More Information?

Research Articles, Reviews, and Opinion Pieces

Scholarly or research articles are written for experts in their fields. They are often peer-reviewed or reviewed by other experts in the field prior to publication. They often have terminology or jargon that is field specific. They are generally lengthy articles. Social science and science scholarly articles have similar structures as do arts and humanities scholarly articles. Not all items in a scholarly journal are peer reviewed. For example, an editorial opinion items can be published in a scholarly journal but the article itself is not scholarly. Scholarly journals may include book reviews or other content that have not been peer reviewed.

Empirical Study: (Original or Primary) based on observation, experimentation, or study. Clinical trials, clinical case studies, and most meta-analyses are empirical studies.

Review Article: (Secondary Sources) Article that summarizes the research in a particular subject, area, or topic. They often include a summary, an literature reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses.

Clinical case study (Primary or Original sources): These articles provide real cases from medical or clinical practice. They often include symptoms and diagnosis.

Clinical trials ( Health Research): Th ese articles are often based on large groups of people. They often include methods and control studies. They tend to be lengthy articles.

Opinion Piece: An opinion piece often includes personal thoughts, beliefs, or feelings or a judgement or conclusion based on facts. The goal may be to persuade or influence the reader that their position on this topic is the best.

Book review: Recent review of books in the field. They may be several pages but tend to be fairly short.

Social Science and Science Research Articles

The majority of social science and physical science articles include

- Journal Title and Author

- Abstract

- Introduction with a hypothesis or thesis

- Literature Review

- Methods/Methodology

- Results/Findings

Arts and Humanities Research Articles

In the Arts and Humanities, scholarly articles tend to be less formatted than in the social sciences and sciences. In the humanities, scholars are not conducting the same kinds of research experiments, but they are still using evidence to draw logical conclusions. Common sections of these articles include:

- an Introduction

- Discussion/Conclusion

- works cited/References/Bibliography

Research versus Review Articles

- 6 Article types that journals publish: A guide for early career researchers

- INFOGRAPHIC: 5 Differences between a research paper and a review paper

- Michigan State University. Empirical vs Review Articles

- UC Merced Library. Empirical & Review Articles

- << Previous: Where Do I Start?

- Next: How Do I Find Peer-Reviewed Articles? >>

- Last Updated: Jan 24, 2024 10:48 AM

- URL: https://library.bridgew.edu/scholarly

Phone: 508.531.1392 Text: 508.425.4096 Email: [email protected]

Feedback/Comments

Privacy Policy

Website Accessibility

Follow us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Faculty and researchers : We want to hear from you! We are launching a survey to learn more about your library collection needs for teaching, learning, and research. If you would like to participate, please complete the survey by May 17, 2024. Thank you for your participation!

- University of Massachusetts Lowell

- University Libraries

Peer Reviewed Articles: What Are They?

- What is a Scholarly or Peer Reviewed Article?

- How to Tell if a Journal Article is Peer Reviewed

- Review Articles

- Types of Literature Sources, (Grey Literature)

- What are Evidence Based Reviews?

Related Information

- Video: What is Intellectual Dishonesty

If you cannot access the above video, you can watch it here

Characteristics of Scholarly Literature

Look for these:

- Often have a formal appearance with tables, graphs, and diagrams

- Always cite their sources in the form of footnotes or bibliographies

- Usually have an abstract or summary paragraph above the text; may have sections describing methodology

- Articles are written by an authority or expert in the field

- The language includes specialized terms and the jargon of the discipline

- Titles of scholarly journals often contain the word "Journal", "Review", "Bulletin", or "Research"

- Usually have a narrow or specific subject focus

- Contains original research, experimentation, or in-depth studies in the field

- Written for researchers , professors, or students in the field

- Often reviewed by the author's peers before publication (peer-reviewed or refereed)

- Advertising is minimal or none.

- Anatomy of a Scholarly Article Interactive mock-up of a scholarly article explaining the various section. from NCSU Libraries

► Peer-reviewed (or refereed): Refers to articles that have undergone a rigorous review process, often including revisions to the original manuscript, by peers in their discipline, before publication in a scholarly journal. This can include empirical studies, review articles, meta-analyses among others.

► Empirical study (or primary article) : An empirical study is one that aims to gain new knowledge on a topic through direct or indirect observation and research. These include quantitative or qualitative data and analysis. In science, an empirical article will often include the following sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion.

► Review article: In the scientific literature, this is a type of article that provides a synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. These are useful when you want to get an idea of a body of research that you are not yet familiar with. It differs from a systematic review in that it does not aim to capture ALL of the research on a particular topic.

► Systematic review : This is a methodical and thorough literature review focused on a particular research question. It's aim is to identify and synthesize all of the scholarly research on a particular topic in an unbiased, reproducible way to provide evidence for practice and policy-making. It may involve a meta-analysis (see below).

► Meta-analysis : This is a type of research study that combines or contrasts data from different independent studies in a new analysis in order to strengthen the understanding of a particular topic. There are many methods, some complex, applied to performing this type of analysis.

(Adapted from Scholarly Literature Types , Cornell University)

- Next: How to Tell if a Journal Article is Peer Reviewed >>

- Last Updated: Feb 14, 2024 3:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uml.edu/healtharticle_types

Communication Sciences & Disorders

- Communication Sciences & Disorders

- The research process

- Defining your topic and crafting your research question

- Identifying search terms from your question

- Broaden or narrow your search

- Find background information

- Find Articles

- Find books and ebooks

- Interlibrary loan

- Evidence Based Practice Portal (opens a new guide) This link opens in a new window

- How to distinguish between types of journal articles

- Components of a scholarly article, and things to consider when reading one

- Critically evaluating articles & other sources

- Writing tools

- Citing sources (opens a new guide) This link opens in a new window

- Understanding & Avoiding Plagiarism (opens a new guide) This link opens in a new window

- Organizations & Websites

Contact me for research assistance

Distinguishing between different types of journal articles

When writing a paper or conducting academic research, you’ll come across many different types of sources, including periodical articles. Periodical articles can be comprised of news accounts, opinion, commentary, scholarly analysis, and/or reports of research findings. There are three main types of periodicals that you will encounter: scholarly/academic, trade, and popular. The chart below will help you identify which type of periodical your article comes from.

Text and chart adapted from the WSU University Libraries' How to Distinguish Between Types of Periodicals and Types of Periodicals guides

What makes information peer-reviewed vs. scholarly vs. non-scholarly? Which type of source should I use?

- What makes information peer-reviewed vs. scholarly vs. non-scholarly?

- Which type of source should I use?

There is a nuanced distinction between peer-review and scholarship, which typically doesn't matter when evaluating sources for possible citation in your own work. Peer-review is a process through which editors of a journal have other experts in the field evaluate articles submitted to the journal for possible publication. Different journals have different ways of defining an expert in the field. Scholarly works, by contrast have an editorial process, but this process does not involve expert peer-reviewers. Rather, one or more editors, who are themselves often highly decorated scholars in a field, evaluate submissions for possible publication. This editorial process can be more economically driven than a peer-review process, with a greater emphasis on marketing and selling the published material, but as a general rule this distinction is trivial with regard to evaluating information for possible citation in your own work.

What is perhaps a more salient way of thinking about the peer-review / scholarship distinction is to recognize that while peer-reviewed information is typically highly authoritative, and is generally considered "good" information, the absence of a peer-review process doesn't automatically make information "bad." More specifically, the only thing the absence of a peer-review process means is that information published in this manner is not peer-reviewed. Nothing more. Information that falls into this category is sometimes referred to as "non-scholarly" information -- but again, that doesn't mean this information is somehow necessarily problematic.

Where does that leave you in terms of deciding what type of information to use in producing your own work? That is a highly individual decision that you must make. The Which type of source should I use? tab in this box offers further guidance on answering this question, though it is important to be aware that many WSU instructors will only consider peer-reviewed sources to be acceptable in the coursework you turn in . You can ask your instructor for his or her thoughts on the types of sources s/he will accept in student work.

Image: Martin Grater. (2017, Nov. 1). Deep Thought. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/152721954@N05/24304490568/. Used under the Creative Commons License.

Your topic and research question or thesis statement will guide you on which resources are best. Sources can be defined as primary, secondary and tertiary levels away from an event or original idea. Researchers may want to start with tertiary or secondary source for background information. Learning more about a topic will help most researchers make better use of primary sources.

While articles from scholarly journals are often the most prominent of the sources you will consider incorporating into your coursework, they are not the only sources available to you. Which sources are most appropriate to your research is a direct consequence of they type of research question you decide to address. In other words, while most university-level papers will require you to reference scholarly sources, not all will. A student in an English course writing a paper analyzing Bob Dylan's lyrics, for example, may find an interview with Dylan published in Rolling Stone magazine a useful source to cite alongside other scholarly works of literary criticism.

The WSU University Libraries' What Sources Should I Use? handout, as well as the other sub-tabs under the Evaluating information section of this guide (which is indeed the section you are currently viewing) offer further guidance on understanding and identifying scholarly resources, and comparing them against different criteria to evaluate if they will be of value to your research. How many non-scholarly works (if any) you are at liberty to cite alongside scholarly ones is often a question to ask of your professor. Some may not want you to cite any, whereas others may be ok with some non-scholarly works cited alongside scholarly ones.

Image: Brett Woods. (2006, Jan. 6). Deep Thoughts. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/brettanicus/87653641/. Used under the Creative Commons License.

- << Previous: Evaluating information

- Next: Components of a scholarly article, and things to consider when reading one >>

- Last Updated: Jan 2, 2024 4:10 PM

- URL: https://libraries.wichita.edu/csd

- Master Your Homework

- Do My Homework

Research Paper vs. Research Article: What’s the Difference?

Research papers and research articles are two different forms of academic writing, with distinct characteristics. Although they share some similarities in terms of format and purpose, there are important distinctions between the two types that should be understood by students who wish to write either form effectively. This article will explain the differences between a research paper and a research article, outlining their unique features and applications. Furthermore, it will offer guidance on how best to approach each type when crafting an effective piece for scholarly consumption.

I. Introduction to Research Paper vs. Research Article

Ii. defining a research paper and a research article, iii. comparative analysis of structure, content, and writing styles between the two types of scholarly documents, iv. pros & cons of conducting either a formal or an informal study, v. concluding remarks: how to choose between the different approaches when completing academic assignments, vi. limitations in comparing these texts as distinct forms of scholarly outputs, vii. future directions for understanding similarities & differences across all kinds of academic writings.

Research Paper vs. Research Article

The academic world is full of a variety of different writing styles, each with its own unique purpose and goals. Two particularly important forms are the research paper and the research article. Each has their own distinct features that make them uniquely suited to certain tasks within academia – let’s take a closer look at what sets them apart from one another!

A research paper , as you might expect, presents in-depth analysis on an issue or topic using evidence gathered through primary sources such as field work, laboratory experiments, surveys, interviews etc., whereas a research article , typically published in scholarly journals or online publications like websites & blogs addresses specific findings derived from secondary sources like books or other papers related to said subject matter. The former requires more effort & dedication from the author due to it being time consuming & involving careful structuring along with rigorous citation format adherence; while the latter focuses mainly on providing succinct yet comprehensive overviews regarding topics which have already been extensively discussed by experts in depth previously elsewhere – taking into account present day developments/breakthroughs if necessary before finally offering opinionated conclusions pertaining to said subjects.

Exploring the Characteristics of a Research Paper and Article

- Research paper:

- Research article:

A research paper is an extended form of writing that presents and supports an argument on a particular topic. It provides evidence for the opinion or idea in the form of facts, data, analysis, opinions from authorities in specific fields etc. The objective is to make original claims based on careful evaluation of information available on a given subject. It requires significant effort as one needs to be able to distill complex topics into concisely articulated points that are supported by solid evidence.

On the other hand, a research article is usually written for publication either online or printed through journals or magazines. These articles have been peer-reviewed which means they follow certain academic standards established within their discipline while presenting factual conclusions related to ongoing debates and arguments raised by preceding works. They generally provide new insight into existing knowledge rather than build upon it using more primary sources such as surveys and experiments conducted independently by authors themselves.

Comparison of Structure, Content and Writing Styles between Research Papers and Articles For the purpose of scholarly communication, both research papers and articles play a vital role. Though there is no hard-and-fast rule that distinguishes them from each other in terms of structure or content, they usually differ significantly in their style. In comparison to research papers, articles typically have a much smaller length requirement. They can range anywhere from 1 page to as many as 30 pages depending on the journal guidelines – making them more accessible for readers who are seeking concise summaries with quick insights into topics. On the contrary, research papers tend to be longer documents that delve deeper into an issue by providing extensive background information; detailed analysis; arguments bolstered by sources such as peer-reviewed journals or interviews; conclusion sections tying up any loose ends etc.

- Research Papers: Longer documents which provide extensive coverage about an issue.

- Articles: Short pieces covering high level overviews without going too deep.

When it comes down to writing styles used for these two types of documents – Authors generally follow formal academic language while creating research paper whereas article writers tend to use more casual tones in order to appeal wider audience groups. Additionally authors will often adopt conversational elements like anecdotes when crafting articles so that readers can get better understanding about specific points being discussed within context.

Formal vs. Informal Study: A Critical Analysis The choice between conducting a formal or informal study may be difficult for researchers due to the advantages and drawbacks of each approach. Depending on their research topic, scientists must carefully weigh up the pros and cons before deciding which course of action is most suitable for them.

A formal study , as conducted in many research papers and articles, often requires more time-consuming effort from researchers than an informal one because it involves using specific methodologies such as surveys, interviews, experiments etc., gathering quantitative data that needs to be statistically analyzed by employing reliable statistical methods. On the other hand, a formal investigation allows researchers to obtain objective information from well-defined populations about predetermined variables through systematic procedures that can yield precise results with larger external validity – making it possible to make generalizations beyond those studied in this particular case.

Conversely, an informal study , also known as participant observation or field work requires less structured approaches where collecting qualitative data is usually achieved via conversations with informants instead of strict instrumentations; thus allowing greater interaction between researcher and subjects resulting in increased understanding of contextually situated phenomena within its natural setting rather than artificially created ones used in laboratories’ studies – leading to deeper insights into complex social processes . Also noteworthy is its lower financial cost when compared against highly expensive equipment needed for undertaking large scale scientific investigations.. However despite yielding valuable first person accounts which might not have been obtained elsewhere , such observations are sometimes criticized due challenges related accuracy given reliance on subjective interpretations while generating evidence without significant use of control variables .

Selecting the Optimal Approach for Academic Assignments When it comes to completing academic assignments, there are various approaches one can take. In order to ensure success and optimal results, it is important that students consider all of their options carefully before making a choice.

Research papers often require extensive research and careful consideration when selecting an approach. Using primary sources such as books or peer-reviewed articles may be more reliable in comparison to secondary sources such as websites or blogs which are usually less credible due to lack of credibility checks by professionals within the field. Additionally, data analysis can help strengthen arguments while also adding clarity to any work produced during the course of completion; however, understanding how best utilize this analytical tool effectively requires additional practice and experience on behalf of the student undertaking it. For research articles, detailed knowledge about particular topics may lead towards better outcomes but general familiarity with content areas is sufficient enough for success here too. The key lies in being able identify appropriate methods quickly through use critical thinking skills coupled with clear objectives pertaining specifically each assignment itself at hand prior its execution – this way mistakes are avoided thus delivering quality results each time..

Comparative Analyses of Scholarly Outputs

- Scholarly output, such as research papers and articles, are subject to scrutiny when attempting to make comparisons.

- Due to the differences between these two types of outputs, it can be difficult or impossible to achieve a true comparison.

Comparing scholarly outputs is not always possible due to their distinct forms. Research papers typically have more depth than an article on the same topic which may mean that even though both documents might discuss similar topics in some aspects they will differ greatly in others. Furthermore, the format of each type of document contributes further complexities; for example, a research paper is often much longer and requires extensive background information before any conclusions can be drawn while articles tend towards presenting results with little room left for interpretation. The style used by authors also adds difficulty; many times research papers include complex jargon necessary for understanding specific points whereas an article strives for simplicity so its target audience can comprehend all material without excessive effort. These limitations prevent proper analysis from being done since one piece could provide certain details while another provides only bits related thereto leading readers into confusion if attempting to compare them directly despite intentions otherwise. It then becomes clear that academic pieces should instead remain separate entities rather than compared against each other since doing so would lead only too frustration given current constraints therein found.

Exploring the Similarities and Differences Between Academic Writings

As our understanding of academic writings continues to evolve, so too must our appreciation for both their similarities and differences. From research papers to research articles, it is important to consider how each one contributes unique insight into a given topic or issue.

The research paper and research article may look similar on the surface, but upon closer inspection one can see significant differences in their format, purpose, and audience. The key distinctions between these two forms of written work are scope of content covered, type of analysis used to draw conclusions or develop knowledge from data or evidence presented, and intended readership. Ultimately, understanding the essential characteristics that distinguish a research paper from a research article is beneficial for anyone who produces such texts as it will help them craft an effective product that aligns with its desired purposes.

Identifying Primary and Secondary Research Articles

- Primary and Secondary

Primary Research Articles

Primary research articles report on a single study. In the health sciences, primary research articles generally describe the following aspects of the study:

- The study's hypothesis or research question

- Some articles will include information on how participants were recruited or identified, as well as additional information about participants' sex, age, or race/ethnicity

- A "methods" or "methodology" section that describes how the study was performed and what the researchers did

- Results and conclusion section

Secondary Research Articles

Review articles are the most common type of secondary research article in the health sciences. A review article is a summary of previously published research on a topic. Authors who are writing a review article will search databases for previously completed research and summarize or synthesize those articles, as opposed to recruiting participants and performing a new research study.

Specific types of review articles include:

- Systematic Reviews

- Meta-Analysis

- Narrative Reviews

- Integrative Reviews

- Literature Reviews

Review articles often report on the following:

- The hypothesis, research question, or review topic

- Databases searched-- authors should clearly describe where and how they searched for the research included in their reviews

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis should provide detailed information on the databases searched and the search strategy the authors used.Selection criteria-- the researchers should describe how they decided which articles to include

- A critical appraisal or evaluation of the quality of the articles included (most frequently included in systematic reviews and meta-analysis)

- Discussion, results, and conclusions

Determining Primary versus Secondary Using the Database Abstract

Information found in PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus, and other databases can help you determine whether the article you're looking at is primary or secondary.

Primary research article abstract

- Note that in the "Objectives" field, the authors describe their single, individual study.

- In the materials and methods section, they describe the number of patients included in the study and how those patients were divided into groups.

- These are all clues that help us determine this abstract is describing is a single, primary research article, as opposed to a literature review.

- Primary Article Abstract

Secondary research/review article abstract

- Note that the words "systematic review" and "meta-analysis" appear in the title of the article

- The objectives field also includes the term "meta-analysis" (a common type of literature review in the health sciences)

- The "Data Source" section includes a list of databases searched

- The "Study Selection" section describes the selection criteria

- These are all clues that help us determine that this abstract is describing a review article, as opposed to a single, primary research article.

- Secondary Research Article

- Primary vs. Secondary Worksheet

Full Text Challenge

Can you determine if the following articles are primary or secondary?

- Last Updated: Feb 17, 2024 5:25 PM

- URL: https://library.usfca.edu/primary-secondary

2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117-1080 415-422-5555

- Facebook (link is external)

- Instagram (link is external)

- Twitter (link is external)

- YouTube (link is external)

- Consumer Information

- Privacy Statement

- Web Accessibility

Copyright © 2022 University of San Francisco

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.25(3); 2014 Oct

Peer Review in Scientific Publications: Benefits, Critiques, & A Survival Guide

Jacalyn kelly.

1 Clinical Biochemistry, Department of Pediatric Laboratory Medicine, The Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Tara Sadeghieh

Khosrow adeli.

2 Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

3 Chair, Communications and Publications Division (CPD), International Federation for Sick Clinical Chemistry (IFCC), Milan, Italy

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding publication of this article.

Peer review has been defined as a process of subjecting an author’s scholarly work, research or ideas to the scrutiny of others who are experts in the same field. It functions to encourage authors to meet the accepted high standards of their discipline and to control the dissemination of research data to ensure that unwarranted claims, unacceptable interpretations or personal views are not published without prior expert review. Despite its wide-spread use by most journals, the peer review process has also been widely criticised due to the slowness of the process to publish new findings and due to perceived bias by the editors and/or reviewers. Within the scientific community, peer review has become an essential component of the academic writing process. It helps ensure that papers published in scientific journals answer meaningful research questions and draw accurate conclusions based on professionally executed experimentation. Submission of low quality manuscripts has become increasingly prevalent, and peer review acts as a filter to prevent this work from reaching the scientific community. The major advantage of a peer review process is that peer-reviewed articles provide a trusted form of scientific communication. Since scientific knowledge is cumulative and builds on itself, this trust is particularly important. Despite the positive impacts of peer review, critics argue that the peer review process stifles innovation in experimentation, and acts as a poor screen against plagiarism. Despite its downfalls, there has not yet been a foolproof system developed to take the place of peer review, however, researchers have been looking into electronic means of improving the peer review process. Unfortunately, the recent explosion in online only/electronic journals has led to mass publication of a large number of scientific articles with little or no peer review. This poses significant risk to advances in scientific knowledge and its future potential. The current article summarizes the peer review process, highlights the pros and cons associated with different types of peer review, and describes new methods for improving peer review.

WHAT IS PEER REVIEW AND WHAT IS ITS PURPOSE?

Peer Review is defined as “a process of subjecting an author’s scholarly work, research or ideas to the scrutiny of others who are experts in the same field” ( 1 ). Peer review is intended to serve two primary purposes. Firstly, it acts as a filter to ensure that only high quality research is published, especially in reputable journals, by determining the validity, significance and originality of the study. Secondly, peer review is intended to improve the quality of manuscripts that are deemed suitable for publication. Peer reviewers provide suggestions to authors on how to improve the quality of their manuscripts, and also identify any errors that need correcting before publication.

HISTORY OF PEER REVIEW

The concept of peer review was developed long before the scholarly journal. In fact, the peer review process is thought to have been used as a method of evaluating written work since ancient Greece ( 2 ). The peer review process was first described by a physician named Ishaq bin Ali al-Rahwi of Syria, who lived from 854-931 CE, in his book Ethics of the Physician ( 2 ). There, he stated that physicians must take notes describing the state of their patients’ medical conditions upon each visit. Following treatment, the notes were scrutinized by a local medical council to determine whether the physician had met the required standards of medical care. If the medical council deemed that the appropriate standards were not met, the physician in question could receive a lawsuit from the maltreated patient ( 2 ).

The invention of the printing press in 1453 allowed written documents to be distributed to the general public ( 3 ). At this time, it became more important to regulate the quality of the written material that became publicly available, and editing by peers increased in prevalence. In 1620, Francis Bacon wrote the work Novum Organum, where he described what eventually became known as the first universal method for generating and assessing new science ( 3 ). His work was instrumental in shaping the Scientific Method ( 3 ). In 1665, the French Journal des sçavans and the English Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society were the first scientific journals to systematically publish research results ( 4 ). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society is thought to be the first journal to formalize the peer review process in 1665 ( 5 ), however, it is important to note that peer review was initially introduced to help editors decide which manuscripts to publish in their journals, and at that time it did not serve to ensure the validity of the research ( 6 ). It did not take long for the peer review process to evolve, and shortly thereafter papers were distributed to reviewers with the intent of authenticating the integrity of the research study before publication. The Royal Society of Edinburgh adhered to the following peer review process, published in their Medical Essays and Observations in 1731: “Memoirs sent by correspondence are distributed according to the subject matter to those members who are most versed in these matters. The report of their identity is not known to the author.” ( 7 ). The Royal Society of London adopted this review procedure in 1752 and developed the “Committee on Papers” to review manuscripts before they were published in Philosophical Transactions ( 6 ).

Peer review in the systematized and institutionalized form has developed immensely since the Second World War, at least partly due to the large increase in scientific research during this period ( 7 ). It is now used not only to ensure that a scientific manuscript is experimentally and ethically sound, but also to determine which papers sufficiently meet the journal’s standards of quality and originality before publication. Peer review is now standard practice by most credible scientific journals, and is an essential part of determining the credibility and quality of work submitted.

IMPACT OF THE PEER REVIEW PROCESS

Peer review has become the foundation of the scholarly publication system because it effectively subjects an author’s work to the scrutiny of other experts in the field. Thus, it encourages authors to strive to produce high quality research that will advance the field. Peer review also supports and maintains integrity and authenticity in the advancement of science. A scientific hypothesis or statement is generally not accepted by the academic community unless it has been published in a peer-reviewed journal ( 8 ). The Institute for Scientific Information ( ISI ) only considers journals that are peer-reviewed as candidates to receive Impact Factors. Peer review is a well-established process which has been a formal part of scientific communication for over 300 years.

OVERVIEW OF THE PEER REVIEW PROCESS