Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 10, Issue 11

- The Philippine COVID-19 Outcomes: a Retrospective study Of Neurological manifestations and Associated symptoms (The Philippine CORONA study): a protocol study

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5621-1833 Adrian I Espiritu 1 , 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1135-6400 Marie Charmaine C Sy 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1241-8805 Veeda Michelle M Anlacan 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5317-7369 Roland Dominic G Jamora 1

- 1 Department of Neurosciences , College of Medicine and Philippine General Hospital, University of the Philippines Manila , Manila , Philippines

- 2 Department of Clinical Epidemiology, College of Medicine , University of the Philippines Manila , Manila , Philippines

- Correspondence to Dr Adrian I Espiritu; aiespiritu{at}up.edu.ph

Introduction The SARS-CoV-2, virus that caused the COVID-19 global pandemic, possesses a neuroinvasive potential. Patients with COVID-19 infection present with neurological signs and symptoms aside from the usual respiratory affectation. Moreover, COVID-19 is associated with several neurological diseases and complications, which may eventually affect clinical outcomes.

Objectives The Philippine COVID-19 Outcomes: a Retrospective study Of Neurological manifestations and Associated symptoms (The Philippine CORONA) study investigators will conduct a nationwide, multicentre study involving 37 institutions that aims to determine the neurological manifestations and factors associated with clinical outcomes in COVID-19 infection.

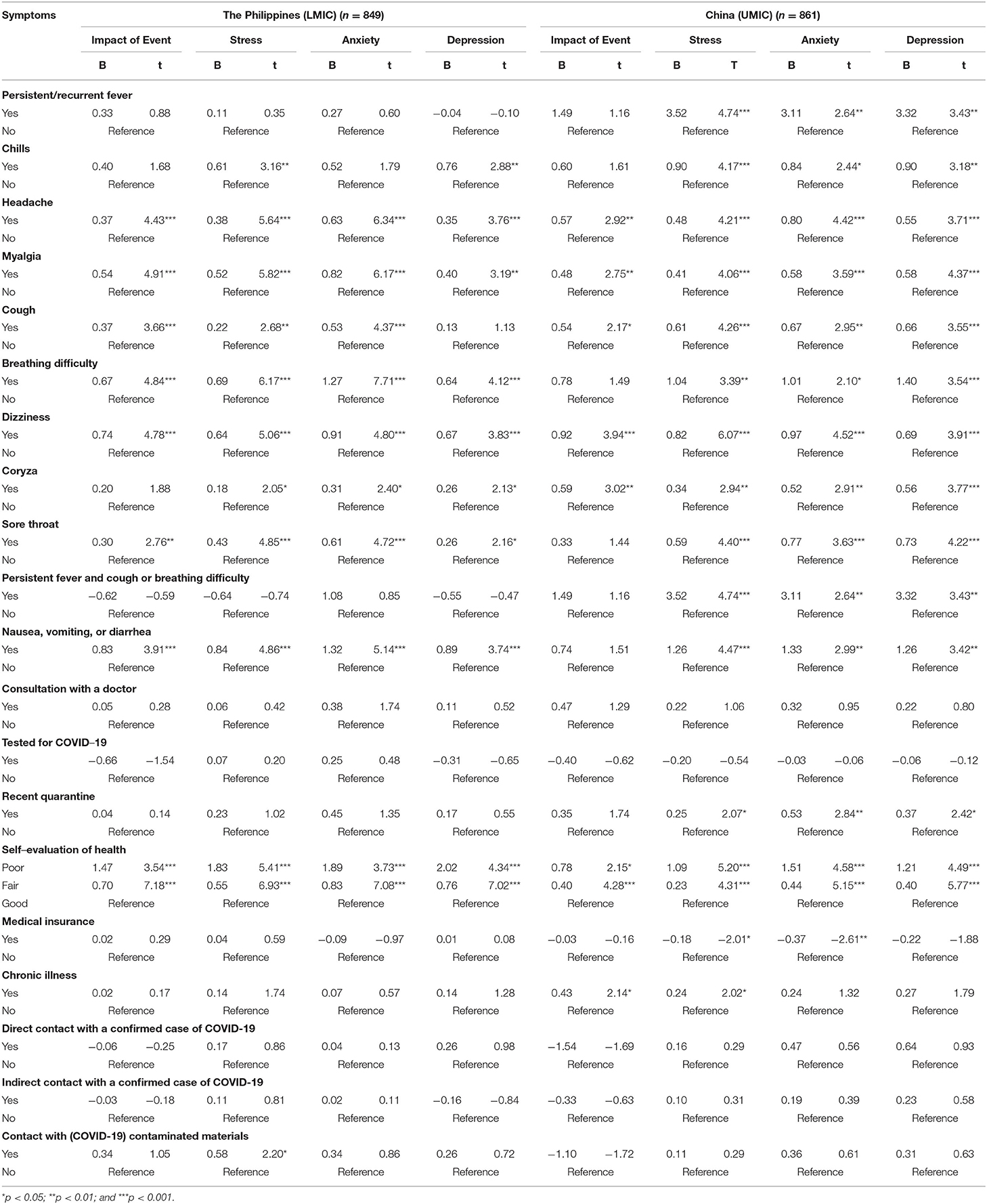

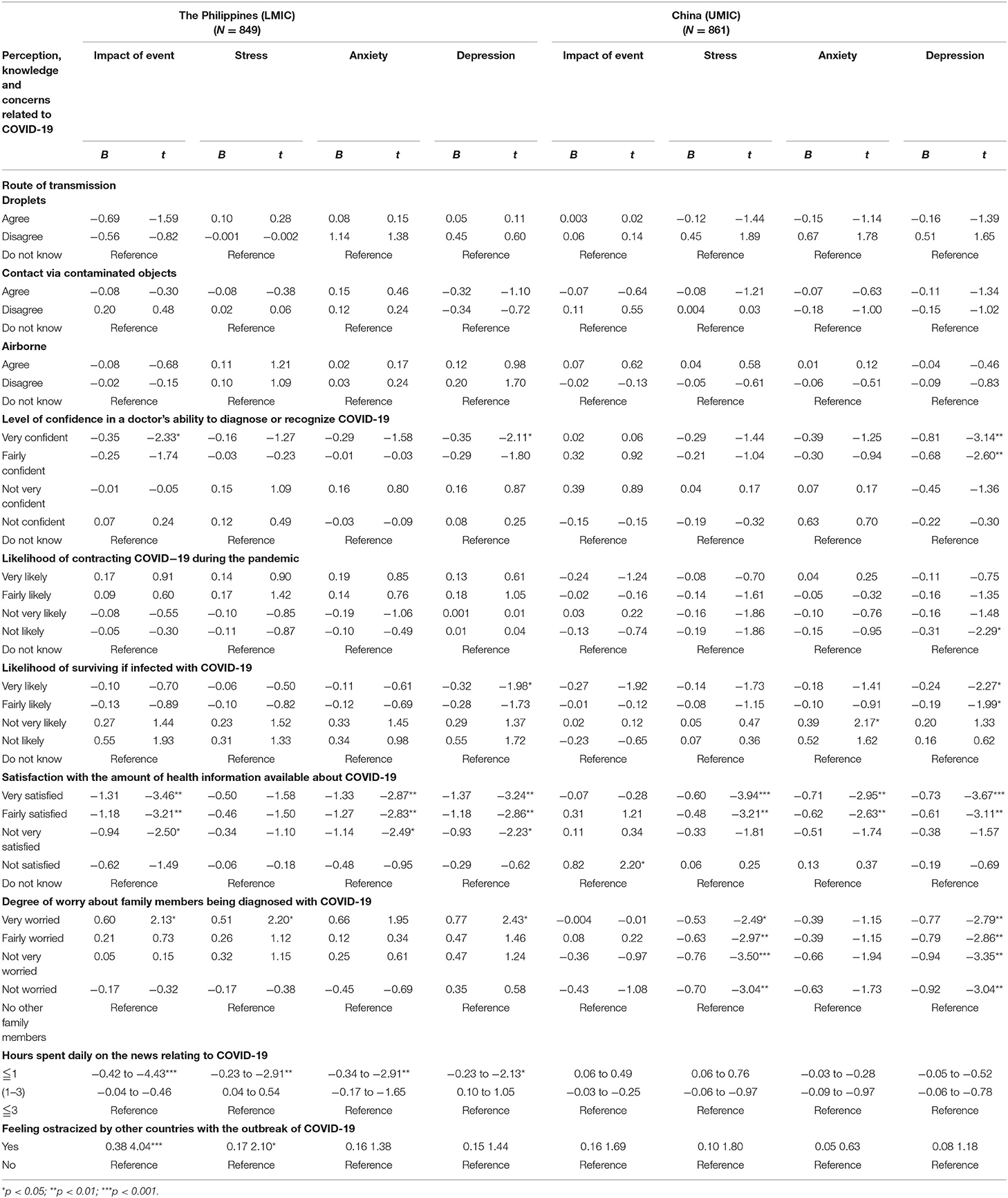

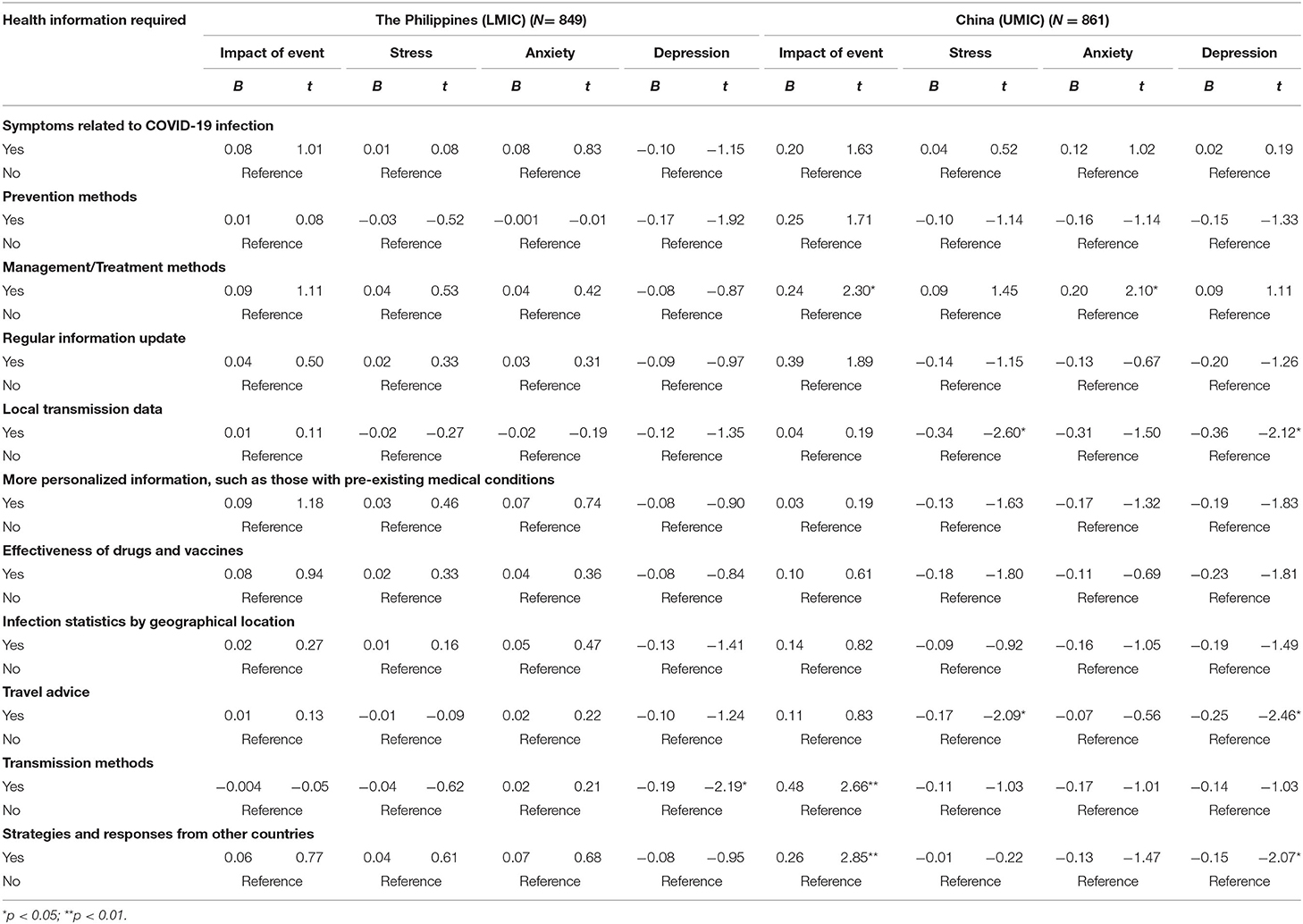

Methodology and analysis This is a retrospective cohort study (comparative between patients with and without neurological manifestations) via medical chart review involving adult patients with COVID-19 infection. Sample size was determined at 1342 patients. Demographic, clinical and neurological profiles will be obtained and summarised using descriptive statistics. Student’s t-test for two independent samples and χ 2 test will be used to determine differences between distributions. HRs and 95% CI will be used as an outcome measure. Kaplan-Meier curves will be constructed to plot the time to onset of mortality (survival), respiratory failure, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, duration of ventilator dependence, length of ICU stay and length of hospital stay. The log-rank test will be employed to compare the Kaplan-Meier curves. Stratified analysis will be performed to identify confounders and effects modifiers. To compute for adjusted HR with 95% CI, crude HR of outcomes will be adjusted according to the prespecified possible confounders. Cox proportional regression models will be used to determine significant factors of outcomes. Testing for goodness of fit will also be done using Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Subgroup analysis will be performed for proven prespecified effect modifiers. The effects of missing data and outliers will also be evaluated in this study.

Ethics and dissemination This protocol was approved by the Single Joint Research Ethics Board of the Philippine Department of Health (SJREB-2020–24) and the institutional review board of the different study sites. The dissemination of results will be conducted through scientific/medical conferences and through journal publication. The lay versions of the results may be provided on request.

Trial registration number NCT04386083 .

- adult neurology

- epidemiology

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040944

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The Philippine COVID-19 Outcomes: a Retrospective study Of Neurological manifestations and Associated symptoms Study is a nationwide, multicentre, retrospective, cohort study with 37 Philippine sites.

Full spectrum of neurological manifestations of COVID-19 will be collected.

Retrospective gathering of data offers virtually no risk of COVID-19 infection to data collectors.

Data from COVID-19 patients who did not go to the hospital are unobtainable.

Recoding bias is inherent due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Introduction

The COVID-19 has been identified as the cause of an outbreak of respiratory illness in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, in December 2019. 1 The COVID-19 pandemic has reached the Philippines with most of its cases found in the National Capital Region (NCR). 2 The major clinical features of COVID-19 include fever, cough, shortness of breath, myalgia, headache and diarrhoea. 3 The outcomes of this disease lead to prolonged hospital stay, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, dependence on invasive mechanical ventilation, respiratory failure and mortality. 4 The specific pathogen that causes this clinical syndrome has been named SARS-CoV-2, which is phylogenetically similar to SARS-CoV. 4 Like the SARS-CoV strain, SARS-CoV-2 may possess a similar neuroinvasive potential. 5

A study on cases with COVID-19 found that about 36.4% of patients displayed neurological manifestations of the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS). 6 The associated spectrum of symptoms and signs were substantially broad such as altered mental status, headache, cognitive impairment, agitation, dysexecutive syndrome, seizures, corticospinal tract signs, dysgeusia, extraocular movement abnormalities and myalgia. 7–12 Several reports were published on neurological disorders associated with patients with COVID-19, including cerebrovascular disorders, encephalopathy, hypoxic brain injury, frequent convulsive seizures and inflammatory CNS syndromes like encephalitis, meningitis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and Guillain-Barre syndrome. 7–16 However, the estimates of the occurrences of these manifestations were based on studies with a relatively small sample size. Furthermore, the current description of COVID-19 neurological features are hampered to some extent by exceedingly variable reporting; thus, defining causality between this infection and certain neurological manifestations is crucial since this may lead to considerable complications. 17 An Italian observational study protocol on neurological manifestations has also been published to further document and corroborate these findings. 18

Epidemiological data on the proportions and spectrum of non-respiratory symptoms and complications may be essential to increase the recognition of clinicians of the possibility of COVID-19 infection in the presence of other symptoms, particularly neurological manifestations. With this information, the probabilities of diagnosing COVID-19 disease may be strengthened depending on the presence of certain neurological manifestations. Furthermore, knowledge of other unrecognised symptoms and complications may allow early diagnosis that may permit early institution of personal protective equipment and proper contact precautions. Lastly, the presence of neurological manifestations may be used for estimating the risk of certain important clinical outcomes for better and well-informed clinical decisions in patients with COVID-19 disease.

To address this lack of important information in the overall management of patients with COVID-19, we organised a research study entitled ‘The Philippine COVID-19 Outcomes: a Retrospective study Of Neurological manifestations and Associated symptoms (The Philippine CORONA Study)’.

This quantitative, retrospective cohort, multicentre study aims: (1) to determine the demographic, clinical and neurological profile of patients with COVID-19 disease in the Philippines; (2) to determine the frequency of neurological symptoms and new-onset neurological disorders/complications in patients with COVID-19 disease; (3) to determine the neurological manifestations that are significant factors of mortality, respiratory failure, duration of ventilator dependence, ICU admission, length of ICU stay and length of hospital stay among patients with COVID-19 disease; (4) to determine if there is significant difference between COVID-19 patients with neurological manifestations compared with those COVID-19 patients without neurological manifestations in terms of mortality, respiratory failure, duration of ventilator dependence, ICU admission, length of ICU stay and length of hospital stay; and (5) to determine the likelihood of mortality, respiratory failure and ICU admission, including the likelihood of longer duration of ventilator dependence and length of ICU and hospital stay in COVID-19 patients with neurological manifestations compared with those without neurological manifestations.

Scope, limitations and delimitations

The study will include confirmed cases of COVID-19 from the 37 participating institutions in the Philippines. Every country has its own healthcare system, whose level of development and strategies ultimately affect patient outcomes. Thus, the results of this study cannot be accurately generalised to other settings. In addition, patients with ages ≤18 years will be excluded in from this study. These younger patients may have different characteristics and outcomes; therefore, yielded estimates for adults in this study may not be applicable to this population subgroup. Moreover, this study will collect data from the patient records of patients with COVID-19; thus, data from patients with mild symptoms who did not go to the hospital and those who had spontaneous resolution of symptoms despite true infection with COVID-19 are unobtainable.

Methodology

To improve the quality of reporting of this study, the guidelines issued by the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Initiative will be followed. 19

Study design

The study will be conducted using a retrospective cohort (comparative) design (see figure 1 ).

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Schematic diagram of the study flow.

Study sites and duration

We will conduct a nationwide, multicentre study involving 37 institutions in the Philippines (see figure 2 ). Most of these study sites can be found in the NCR, which remains to be the epicentre of the COVID-19 pandemic. 2 We will collect data for 6 months after institutional review board approval for every site.

Location of 37 study sites of the Philippine CORONA study.

Patient selection and cohort description

The cases will be identified using the designated COVID-19 censuses of all the participating centres. A total enumeration of patients with confirmed COVID-19 disease will be done in this study.

The cases identified should satisfy the following inclusion criteria: (A) adult patients at least 19 years of age; (B) cases confirmed by testing approved patient samples (ie, nasal swab, sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid) employing real-time reverse transcription PCR (rRT-PCR) 20 from COVID-19 testing centres accredited by the Department of Health (DOH) of the Philippines, with clinical symptoms and signs attributable to COVID-19 disease (ie, respiratory as well as non-respiratory clinical signs and symptoms) 21 ; and (C) cases with disposition (ie, discharged stable/recovered, home/discharged against medical advice, transferred to other hospital or died) at the end of the study period. Cases with conditions or diseases caused by other organisms (ie, bacteria, other viruses, fungi and so on) or caused by other pathologies unrelated to COVID-19 disease (ie, trauma) will be excluded.

The first cohort will involve patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection who presented with any neurological manifestation/s (ie, symptoms or complications/disorder). The comparator cohort will compose of patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection without neurological manifestation/s.

Sample size calculation

We looked into the mortality outcome measure for the purposes of sample size computation. Following the cohort study of Khaledifar et al , 22 the sample size was calculated using the following parameters: two-sided 95% significance level (1 – α); 80% power (1 – β); unexposed/exposed ratio of 1; 5% of unexposed with outcome (case fatality rate from COVID19-Philippines Dashboard Tracker (PH) 23 as of 8 April 2020); and assumed risk ratio 2 (to see a two-fold increase in risk of mortality when neurological symptoms are present).

When these values were plugged in to the formula for cohort studies, 24 a minimum sample size of 1118 is required. To account for possible incomplete data, the sample was adjusted for 20% more. This means that the total sample size required is 1342 patients, which will be gathered from the participating centres.

Data collection

We formulated an electronic data collection form using Epi Info Software (V.7.2.2.16). The forms will be pilot-tested, and a formal data collection workshop will be conducted to ensure collection accuracy. The data will be obtained from the review of the medical records.

The following pertinent data will be obtained: (A) demographic data; (B) other clinical profile data/comorbidities; (C) neurological history; (D) date of illness onset; (E) respiratory and constitutional symptoms associated with COVID-19; (F) COVID-19 disease severity 25 at nadir; (G) data if neurological manifestation/s were present at onset prior to respiratory symptoms and the specific neurological manifestation/s present at onset; (H) neurological symptoms; (i) date of neurological symptom onset; (J) new-onset neurological disorders or complications; (K) date of new neurological disorder or complication onset; (L) imaging done; (M) cerebrospinal fluid analysis; (N) electrophysiological studies; (O) treatment given; (P) antibiotics given; (Q) neurological interventions given; (R) date of mortality and cause/s of mortality; (S) date of respiratory failure onset, date of mechanical ventilator cessation and cause/s of respiratory failure; (T) date of first day of ICU admission, date of discharge from ICU and indication/s for ICU admission; (U) other neurological outcomes at discharge; (V) date of hospital discharge; and (W) final disposition. See table 1 for the summary of the data to be collected for this study.

- View inline

Data to be collected in this study

Main outcomes considered

The following patient outcomes will be considered for this study:

Mortality (binary outcome): defined as the patients with confirmed COVID-19 who died.

Respiratory failure (binary outcome): defined as the patients with confirmed COVID-19 who experienced clinical symptoms and signs of respiratory insufficiency. Clinically, this condition may manifest as tachypnoea/sign of increased work of breathing (ie, respiratory rate of ≥22), abnormal blood gases (ie, hypoxaemia as evidenced by partial pressure of oxygen (PaO 2 ) <60 or hypercapnia by partial pressure of carbon dioxide of >45), or requiring oxygen supplementation (ie, PaO 2 <60 or ratio of PaO 2 /fraction of inspired oxygen (P/F ratio)) <300).

Duration of ventilator dependence (continuous outcome): defined as the number of days from initiation of assisted ventilation to cessation of mechanical ventilator use.

ICU admission (binary outcome): defined as the patients with confirmed COVID-19 admitted to an ICU or ICU-comparable setting.

Length of ICU stay (continuous outcome): defined as the number of days admitted in the ICU or ICU-comparable setting.

Length of hospital stay (continuous outcome): defined as the number of days from admission to discharge.

Data analysis plan

Statistical analysis will be performed using Stata V.7.2.2.16.

Demographic, clinical and neurological profiles will be summarised using descriptive statistics, in which categorical variables will be expressed as frequencies with corresponding percentages, and continuous variables will be pooled using means (SD).

Student’s t-test for two independent samples and χ 2 test will be used to determine differences between distributions.

HRs and 95% CI will be used as an outcome measure. Kaplan-Meier curves will be constructed to plot the time to onset of mortality (survival), respiratory failure, ICU admission, duration of ventilator dependence (recategorised binary form), length of ICU stay (recategorised binary form) and length of hospital stay (recategorised binary form). Log-rank test will be employed to compare the Kaplan-Meier curves. Stratified analysis will be performed to identify confounders and effects modifiers. To compute for adjusted HR with 95% CI, crude HR of outcomes at discrete time points will be adjusted for prespecified possible confounders such as age, history of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and respiratory disease, COVID-19 disease severity at nadir, and other significant confounding factors.

Cox proportional regression models will be used to determine significant factors of outcomes. Testing for goodness of fit will be done using Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Likelihood ratio tests and other information criteria (Akaike Information Criterion or Bayesian Information Criterion) will be used to refine the final model. Statistical significance will be considered if the 95% CI of HR or adjusted HR did not include the number one. A p value <0.05 (two tailed) is set for other analyses.

Subgroup analyses will be performed for proven prespecified effect modifiers. The following variables will be considered for subgroup analyses: age (19–64 years vs ≥65 years), sex, body mass index (<18.5 vs 18.5–22.9 vs ≥23 kg/m 2 ), with history of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease (presence or absence), hypertension (presence or absence), diabetes mellitus (presence or absence), respiratory disease (presence or absence), smoking status (smoker or non-smoker) and COVID-19 disease severity (mild, severe or critical disease).

The effects of missing data will be explored. All efforts will be exerted to minimise missing and spurious data. Validity of the submitted electronic data collection will be monitored and reviewed weekly to prevent missing or inaccurate input of data. Multiple imputations will be performed for missing data when possible. To check for robustness of results, analysis done for patients with complete data will be compared with the analysis with the imputed data.

The effects of outliers will also be assessed. Outliers will be assessed by z-score or boxplot. A cut-off of 3 SD from the mean can also be used. To check for robustness of results, analysis done with outliers will be compared with the analysis without the outliers.

Study organisational structure

A steering committee (AIE, MCCS, VMMA and RDGJ) was formed to direct and provide appropriate scientific, technical and methodological assistance to study site investigators and collaborators (see figure 3 ). Central administrative coordination, data management, administrative support, documentation of progress reports, data analyses and interpretation and journal publication are the main responsibilities of the steering committee. Study site investigators and collaborators are responsible for the proper collection and recording of data including the duty to maintain the confidentiality of information and the privacy of all identified patients for all the phases of the research processes.

Organisational structure of oversight of the Philippine CORONA Study.

This section is highlighted as part of the required formatting amendments by the Journal.

Ethics and dissemination

This research will adhere to the Philippine National Ethical Guidelines for Health and Health-related Research 2017. 26 This study is an observational, cohort study and will not allocate any type of intervention. The medical records of the identified patients will be reviewed retrospectively. To protect the privacy of the participant, the data collection forms will not contain any information (ie, names and institutional patient number) that could determine the identity of the patients. A sequential code will be recorded for each patient in the following format: AAA-BBB where AAA will pertain to the three-digit code randomly assigned to each study site; BBB will pertain to the sequential case number assigned by each study site. Each participating centre will designate a password-protected laptop for data collection; the password is known only to the study site.

This protocol was approved by the following institutional review boards: Single Joint Research Ethics Board of the DOH, Philippines (SJREB-2020-24); Asian Hospital and Medical Center, Muntinlupa City (2020- 010-A); Baguio General Hospital and Medical Center (BGHMC), Baguio City (BGHMC-ERC-2020-13); Cagayan Valley Medical Center (CVMC), Tuguegarao City; Capitol Medical Center, Quezon City; Cardinal Santos Medical Center (CSMC), San Juan City (CSMC REC 2020-020); Chong Hua Hospital, Cebu City (IRB 2420–04); De La Salle Medical and Health Sciences Institute (DLSMHSI), Cavite (2020-23-02-A); East Avenue Medical Center (EAMC), Quezon City (EAMC IERB 2020-38); Jose R. Reyes Memorial Medical Center, Manila; Jose B. Lingad Memorial Regional Hospital, San Fernando, Pampanga; Dr. Jose N. Rodriguez Memorial Hospital, Caloocan City; Lung Center of the Philippines (LCP), Quezon City (LCP-CT-010–2020); Manila Doctors Hospital, Manila (MDH IRB 2020-006); Makati Medical Center, Makati City (MMC IRB 2020–054); Manila Medical Center, Manila (MMERC 2020-09); Northern Mindanao Medical Center, Cagayan de Oro City (025-2020); Quirino Memorial Medical Center (QMMC), Quezon City (QMMC REB GCS 2020-28); Ospital ng Makati, Makati City; University of the Philippines – Philippine General Hospital (UP-PGH), Manila (2020-314-01 SJREB); Philippine Heart Center, Quezon City; Research Institute for Tropical Medicine, Muntinlupa City (RITM IRB 2020-16); San Lazaro Hospital, Manila; San Juan De Dios Educational Foundation Inc – Hospital, Pasay City (SJRIB 2020-0006); Southern Isabela Medical Center, Santiago City (2020-03); Southern Philippines Medical Center (SPMC), Davao City (P20062001); St. Luke’s Medical Center, Quezon City (SL-20116); St. Luke’s Medical Center, Bonifacio Global City, Taguig City (SL-20116); Southern Philippines Medical Center, Davao City; The Medical City, Pasig City; University of Santo Tomas Hospital, Manila (UST-REC-2020-04-071-MD); University of the East Ramon Magsaysay Memorial Medical Center, Inc, Quezon City (0835/E/2020/063); Veterans Memorial Medical Center (VMMC), Quezon City (VMMC-2020-025) and Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center, Cebu City (VSMMC-REC-O-2020–048).

The dissemination of results will be conducted through scientific/medical conferences and through journal publication. Only the aggregate results of the study shall be disseminated. The lay versions of the results may be provided on request.

Protocol registration and technical review approval

This protocol was registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov website. It has received technical review board approvals from the Department of Neurosciences, Philippine General Hospital and College of Medicine, University of the Philippines Manila, from the Cardinal Santos Medical Center (San Juan City) and from the Research Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, De La Salle Medical and Health Sciences Institute (Dasmariñas, Cavite).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Almira Abigail Doreen O Apor, MD, of the Department of Neurosciences, Philippine General Hospital, Philippines, for illustrating figure 2 for this publication.

- Adhikari SP ,

- Wu Y-J , et al

- Department of Health

- Philippine Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases

- Hu Y , et al

- Li Yan‐Chao ,

- Bai Wan‐Zhu ,

- Hashikawa T ,

- Wang M , et al

- Paterson RW ,

- Benjamin L , et al

- Hall JP , et al

- Varatharaj A ,

- Ellul MA , et al

- Mahammedi A ,

- Vagal A , et al

- Collantes MEV ,

- Espiritu AI ,

- Sy MCC , et al

- Merdji H , et al

- Sharifi Razavi A ,

- Poyiadji N ,

- Noujaim D , et al

- Zhou H , et al

- Moriguchi T ,

- Goto J , et al

- Nicholson TR , et al

- Ferrarese C ,

- Priori A , et al

- von Elm E ,

- Altman DG ,

- Egger M , et al

- Li J , et al

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Khaledifar A ,

- Hashemzadeh M ,

- Solati K , et al

- McGoogan JM

- Philippine Research Ethics Board

VMMA and RDGJ are joint senior authors.

AIE and MCCS are joint first authors.

Twitter @neuroaidz, @JamoraRoland

Collaborators The Philippine CORONA Study Group Collaborators: Maritoni C Abbariao, Joshua Emmanuel E Abejero, Ryndell G Alava, Robert A Barja, Dante P Bornales, Maria Teresa A Cañete, Ma. Alma E Carandang-Concepcion, Joseree-Ann S Catindig, Maria Epifania V Collantes, Evram V Corral, Ma. Lourdes P Corrales-Joson, Romulus Emmanuel H Cruz, Marita B Dantes, Ma. Caridad V Desquitado, Cid Czarina E Diesta, Carissa Paz C Dioquino, Maritzie R Eribal, Romulo U Esagunde, Rosalina B Espiritu-Picar, Valmarie S Estrada, Manolo Kristoffer C Flores, Dan Neftalie A Juangco, Muktader A Kalbi, Annabelle Y Lao-Reyes, Lina C Laxamana, Corina Maria Socorro A Macalintal, Maria Victoria G Manuel, Jennifer Justice F Manzano, Ma. Socorro C Martinez, Generaldo D Maylem, Marc Conrad C Molina, Marietta C Olaivar, Marissa T Ong, Arnold Angelo M Pineda, Joanne B Robles, Artemio A Roxas Jr, Jo Ann R Soliven, Arturo F Surdilla, Noreen Jhoanna C Tangcuangco-Trinidad, Rosalia A Teleg, Jarungchai Anton S Vatanagul and Maricar P Yumul.

Contributors All authors conceived the idea and wrote the initial drafts and revisions of the protocol. All authors made substantial contributions in this protocol for intellectual content.

Funding Philippine Neurological Association (Grant/Award Number: N/A). Expanded Hospital Research Office, Philippine General Hospital (Grant/Award Number: N/A).

Disclaimer Our funding sources had no role in the design of the protocol, and will not be involved during the methodological execution, data analyses and interpretation and decision to submit or to publish the study results.

Map disclaimer The depiction of boundaries on the map(s) in this article does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. The map(s) are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient and public involvement Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and confidence in the Philippines and Malaysia: A cross-sectional study of sociodemographic factors and digital health literacy

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Clinical Informatics Research Unit, Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom

Roles Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Community Medicine, International Medical School, Management and Science University, Shah Alam, Malaysia, Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Asia Metropolitan University, Johor Bahru, Malaysia, Global Public Health, Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Monash University Malaysia, Bandar Sunway, Malaysia

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Cyberjaya, Cyberjaya, Malaysia

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department: School of Criminal Justice Education, Institution: J.H. Cerilles State College, Caridad, Dumingag, Zamboanga del Sur, Philippines

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Global Public Health, Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Monash University Malaysia, Bandar Sunway, Malaysia, South East Asia Community Observatory (SEACO), Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Monash University Malaysia, Bandar Sunway, Malaysia

- Ken Brackstone,

- Roy R. Marzo,

- Rafidah Bahari,

- Michael G. Head,

- Mark E. Patalinghug,

- Published: October 19, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

With the emergence of the highly transmissible Omicron variant, large-scale vaccination coverage is crucial to the national and global pandemic response, especially in populous Southeast Asian countries such as the Philippines and Malaysia where new information is often received digitally. The main aims of this research were to determine levels of hesitancy and confidence in COVID-19 vaccines among general adults in the Philippines and Malaysia, and to identify individual, behavioural, or environmental predictors significantly associated with these outcomes. Data from an internet-based cross-sectional survey of 2558 participants from the Philippines ( N = 1002) and Malaysia ( N = 1556) were analysed. Results showed that Filipino (56.6%) participants exhibited higher COVID-19 hesitancy than Malaysians (22.9%; p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences in ratings of confidence between Filipino (45.9%) and Malaysian (49.2%) participants ( p = 0.105). Predictors associated with vaccine hesitancy among Filipino participants included women (OR, 1.50, 95% CI, 1.03–1.83; p = 0.030) and rural dwellers (OR, 1.44, 95% CI, 1.07–1.94; p = 0.016). Among Malaysian participants, vaccine hesitancy was associated with women (OR, 1.50, 95% CI, 1.14–1.99; p = 0.004), social media use (OR, 11.76, 95% CI, 5.71–24.19; p < 0.001), and online information-seeking behaviours (OR, 2.48, 95% CI, 1.72–3.58; p < 0.001). Predictors associated with vaccine confidence among Filipino participants included subjective social status (OR, 1.13, 95% CI, 1.54–1.22; p < 0.001), whereas vaccine confidence among Malaysian participants was associated with higher education (OR, 1.30, 95% CI, 1.03–1.66; p < 0.028) and negatively associated with rural dwellers (OR, 0.64, 95% CI, 0.47–0.87; p = 0.005) and online information-seeking behaviours (OR, 0.42, 95% CI, 0.31–0.57; p < 0.001). Efforts should focus on creating effective interventions to decrease vaccination hesitancy, increase confidence, and bolster the uptake of COVID-19 vaccination, particularly in light of the Dengvaxia crisis in the Philippines.

Citation: Brackstone K, Marzo RR, Bahari R, Head MG, Patalinghug ME, Su TT (2022) COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and confidence in the Philippines and Malaysia: A cross-sectional study of sociodemographic factors and digital health literacy. PLOS Glob Public Health 2(10): e0000742. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742

Editor: Nnodimele Onuigbo Atulomah, Babcock University, NIGERIA

Received: June 12, 2022; Accepted: September 20, 2022; Published: October 19, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Brackstone et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Data are available on the OSF repository: https://osf.io/ncwjq/ .

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

While many high-income settings have achieved relatively high coverage with their COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, almost 32.1% of the world’s population have not received a single dose of any COVID-19 vaccine as of July 2022 [ 1 ]. The Philippines and Malaysia are among two of the most populous countries in Southeast Asia with an estimated population of 110 million and 32 million people, respectively. To date, Malaysia has seen over 4.6 million cases with a mortality rate of 0.77%, while approximately 3.7 million cases of COVID-19 were detected in the Philippines with a mortality rate of 1.60% [ 2 ]. Malaysia is doing considerably well with their vaccination efforts, with 84.8% of the population currently considered fully vaccinated as of July 2022. However, vaccination campaigns in the Philippines have been more difficult, with 65.6% of the population fully vaccinated [ 3 ]. With the emergence of the highly transmissible Omicron variant across the world [ 4 ], large-scale vaccination coverage remains fundamental to the national and global pandemic response. Regular scientific assessments of factors that may impede the success of COVID-19 vaccination coverage will be critical as vaccination campaigns continue in these nations.

A key factor for the success of vaccination campaigns is people’s willingness to be vaccinated once doses become accessible to them personally. Vaccine hesitancy is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the delay in the acceptance, or blunt refusal of, vaccines. In fact, vaccine hesitancy was described by the WHO as one of the top 10 threats to global health in 2019 [ 5 ]. Conversely, vaccine confidence relates to individuals’ beliefs that vaccines are effective and safe. In general, a loss of trust in health authorities is a key determinant of vaccine confidence, with misconceptions about vaccine safety being among the most common reasons for low confidence in vaccines [ 6 ].

Previously, vaccination in Southeast Asia has been associated with mistrust and fear, particularly in the Philippines, who are still suffering the consequences of the Dengvaxia (dengue) vaccine controversy in 2017 [ 7 ]. Studies suggest that this highly political mainstream event, in which anti-vaccination campaigns linked dengue vaccines with autism spectrum disorder and with corrupt schemes of pharmaceutical companies, continue to erode the population’s trust in vaccines. For example, a survey conducted on over 30,000 Filipinos in early 2021 showed that 41% of respondents would refuse the COVID-19 vaccine once it became available, whereas Malaysia reported 27% hesitancy [ 8 ]. Researchers predict that the controversy surrounding Dengvaxia may have prompted severe medical mistrust and subsequently weakened the public’s attitudes toward vaccines [ 7 , 9 ]. However, there may be many additional factors that weaken confidence in vaccines. For example, incompatibility with religious beliefs is one key driver of weakened confidence in vaccines [ 10 , 11 ], whereas living in urbanised (vs. rural) areas predicts COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in some countries [ 12 – 14 ], possibly due to being more connected to the internet and social media and being more exposed to COVID-19-related misinformation.

Other predictors of vaccine hesitancy and confidence may include digital health literacy–one’s ability to seek, find, understand, and appraise health information from digital resources–and social media use. Research has shown that beliefs in available information is integral to perceptions of the vaccine safety and effectiveness [ 15 – 17 ]. Previous studies, for example, have associated higher vaccine hesitancy with misinformation about the virus and vaccines, particularly if they relied on social media as a key source of information [ 18 , 19 ]. Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) is a widely accepted theory which may explain individual behaviors, including digital health literacy [ 20 ]. SCT consists of three factors–environmental, personal, and behavioural–and any two of these components interact with each other and influence the third. As such, SCT can assist in establishing a link between one’s behaviour (e.g., information-seeking–one form of digital health literacy) and environmental factors (e.g., availability of information online), which may interact to promote medical mistrust and influence vaccine hesitancy and confidence (personal) [ 21 ]. Thus, health behaviours are often influenced by social systems as well as personal behaviours.

Although vaccine hesitancy and confidence are related concepts (e.g., people who express low confidence in vaccines are more likely to be vaccine-hesitant [ 6 ]), they are also distinct [ 22 ]. Thus, the main aims of this research were to determine levels of hesitancy and confidence in COVID-19 vaccines among general adults in the Philippines and Malaysia, and to identify behavioural or environmental predictors that are significantly associated with both outcomes. Thus, developing a deeper understanding of the factors associated with vaccine hesitancy and confidence will provide insight into how specific population groups may respond to health threats and public health control measures.

Design, subjects, and procedure

This was an internet-based cross-sectional survey conducted from May 2021 to September 2021 in the Philippines and Malaysia. Snowball sampling methods were used for the data collection using social media, including research networks of universities, hospitals, friends, and relatives. Filipino and Malaysian residents aged 18 years or older were invited to take part. The inclusion criteria for participants’ eligibility included 18 years or older, and an understanding of the English language. All invited participants consented to the online survey before completion. Consented participants could only respond to questions once using a single account. The voluntary survey contained a series of questions which assessed sociodemographic variables, social media use, digital literacy skills in health, and attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine.

Ethical approval

The study received ethical approval from Asia Metropolitan University’s Medical Research and Ethics Committee (Ref: AMU/FOM/MREC 0320210018). All participants provided informed consent. All study information was written and provided on the first page of the online questionnaire, and participants indicated consent by selecting the agreement box and proceeding to the survey.

Demographics.

Filipino and Malaysian participants indicated their age category (18–24, 25–34, or 35–44), gender (man, woman), community type (rural, urban), educational level (no formal education, primary, secondary, tertiary), employment (unemployed, part-time, full-time), religion (Christian, Buddhism, Muslim, Hinduism, Other, None), income (1 = very insufficient ; 4 = very sufficient ; M = 1.84, SD = 0.81), whether they were permanently impaired by a health problem (no vs. yes), and whether they were social media users (no vs. yes).

Subjective social status.

Participant then rated their own perceived social status using the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status scale [ 23 ]. Participants viewed a drawing of a ladder with 10 rungs, and read that the ladder represented where people stand in society. They read that the top of the ladder consists of people who are best off, have the most money, highest education, and best jobs, and those at the bottom of the ladder consists of people who are worst off, have the least money, lowest education, and worst or no jobs. Using a validated single-item measure, participants placed an ‘X’ on the rung that best represented where they think they stood on the ladder (1 = lowest ; 10 = highest; M = 6.23, SD = 1.86).

Vaccine confidence and hesitancy.

Participants were also asked about their perceived level of confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine (“I am completely confident that the COVID-19 vaccine is safe,” 1 = strongly disagree ; 7 = strongly agree; M = 4.57, SD = 1.48). Then, participants were asked about their level of hesitancy to the COVID-19 vaccine (“I think everyone should be vaccinated according to the national vaccination schedule”; no, I don’t know, yes). These questions were adapted from the World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe survey [ 24 ]. The tool underwent evaluation by multidisciplinary panel of experts for necessity, clarity, and relevance.

Digital health literacy.

Finally, participants completed the Digital Health Literacy Instrument (DHLI) [ 25 ], which was adapted in the context of the COVID-HL Network. The scale measures one’s ability to seek, find, understand, and appraise health information from digital resources. A total of 12 items (three per each dimension) were asked, and answers were recorded on a four-point Likert scale (1 = very difficult ; 4 = very easy; α = .92; M = 2.15, SD = 0.59). While the original DHLI is comprised of 7 subscales, we used the following four domains, including: (1) information searching or using appropriate strategies to look for information (e.g., “When you search the internet for information on coronavirus virus or related topics, how easy or difficult is it for you to find the exact information you are looking for?”; α = .87; M = 2.15, SD = 0.65), (2) adding self-generated content to online-based platforms (e.g., “When typing a message on a forum or social media such as Facebook or Twitter about the coronavirus a related topic, how easy or difficult is it for you to express your opinion, thought, or feelings in writing?”; α = .74; M = 2.15, SD = 0.65), (3) evaluating reliability of online information (e.g., “When you search the internet for information on the coronavirus or related topics, how easy or difficult is it for you to decide whether the information is reliable or not?”; α = .86; M = 2.20, SD = 0.69), and (4) determining relevance of online information (e.g., “When you search the internet for information on the coronavirus or related topics, how easy or difficult is it for you to use the information you found to make decisions about your health [e.g., protective measures, hygiene regulations, transmission routes, risks and their prevention?”]; α = .87; M = 2.09, SD = 0.68). The reliability statistics for the overall DHL score was 0.92, while the alpha coefficients for the four subscales ranged from 0.74 to 0.87, suggesting acceptable to good internal consistency.

Data analysis

Data were examined for errors, cleaned, and exported into IBM SPSS Statistics 28 for further analysis. All hypotheses were tested at a significance level of 0.05. χ 2 tests were conducted for group differences of categorical variables, and Mann-Whitney tests for continuous variables. Subgroup analyses were performed for Filipino and Malaysian participants.

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and confidence were treated as separate dependent variables in a logistic regression model providing the strictest test of potential associations with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and confidence among Filipino and Malaysian participants. Low vaccine confidence was operationalised by dichotomising participants’ responses to the statement: “I am completely confident that the COVID-19 vaccine is safe” into those who disagreed or neither agreed nor disagreed (1–4), whereas high vaccine confidence was operationalised by dichotomising participants’ responses into those who agreed to some extent (5–7). Vaccine hesitancy was operationalised by dichotomising responses to the statement: “I think everyone should be vaccinated according to the National vaccination schedule” into those indicating ‘no’ or ‘I don’t know,’ whereas no vaccine hesitancy was operationalized by dichotomising participants’ response into those who indicated ‘yes.’

Independent variables were: age (18–24 vs. 25–34 vs. 35–44 [ref]), gender (women vs. men [ref]), community type (rural vs. urban [ref]), educational level (tertiary vs. secondary or less [ref]), employment (employed to some degree vs. unemployed [ref]), religion (Philippines: Christianity vs. Islam [ref]; Malaysia: Christianity vs. Buddhism vs. Hinduism vs. Islam [ref]), income (low (1–2) vs. high (3–4 [ref])), whether they were permanently impaired by a health problem (yes vs. no [ref]), whether they were social media users [yes vs. no [ref]), their perceived ranking on the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status (continuous variable), and finally the four domains of the DHLI scale (all continuous variables).

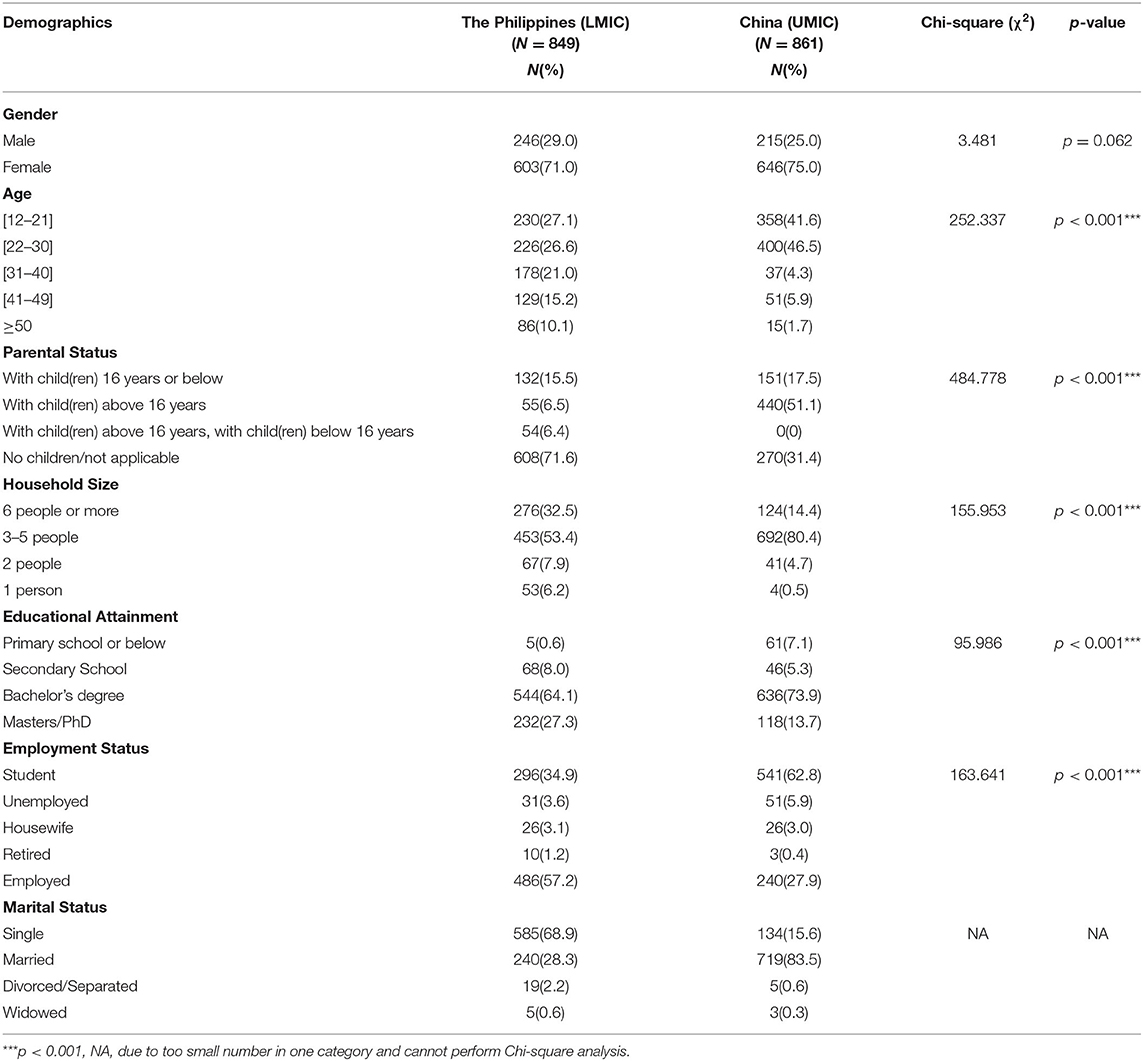

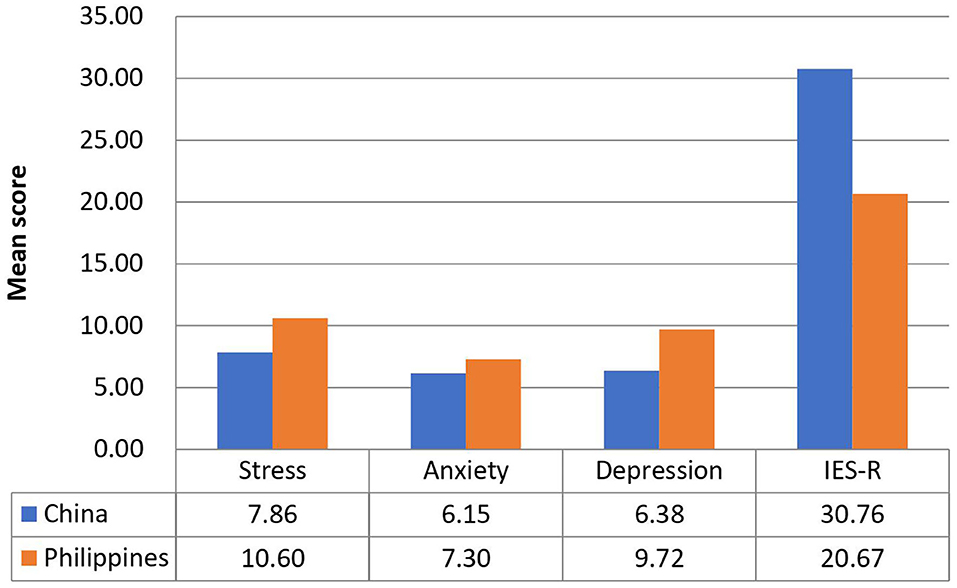

A total of 2558 participants completed the online survey. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics of participants from the Philippines ( N = 1002) vs. Malaysia ( N = 1556). Filipino (vs. Malaysian) participants indicated higher rates of education ( p < 0.001), but were more likely to be unemployed ( p < 0.001). Further, Filipino (vs. Malaysian) participants were also more likely to indicate lower income ( p < 0.001) and rate themselves lower on subjective social status ( p < 0.001). Malaysian (vs. Filipino) participants were more likely to live in urban areas ( p < 0.001). Most notably, Filipino participants (56.6%) indicated higher prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy compared to Malaysian participants (22.9%; p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences between Filipino (45.9%) and Malaysian (49.2%) participants in ratings of vaccine confidence ( p = 0.105). Malaysian (vs. Filipino) participants were also more likely to report using social media (96.6 vs. 89.8%; < 0.001).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Values are presented as percent (n) or means ± SD.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742.t001

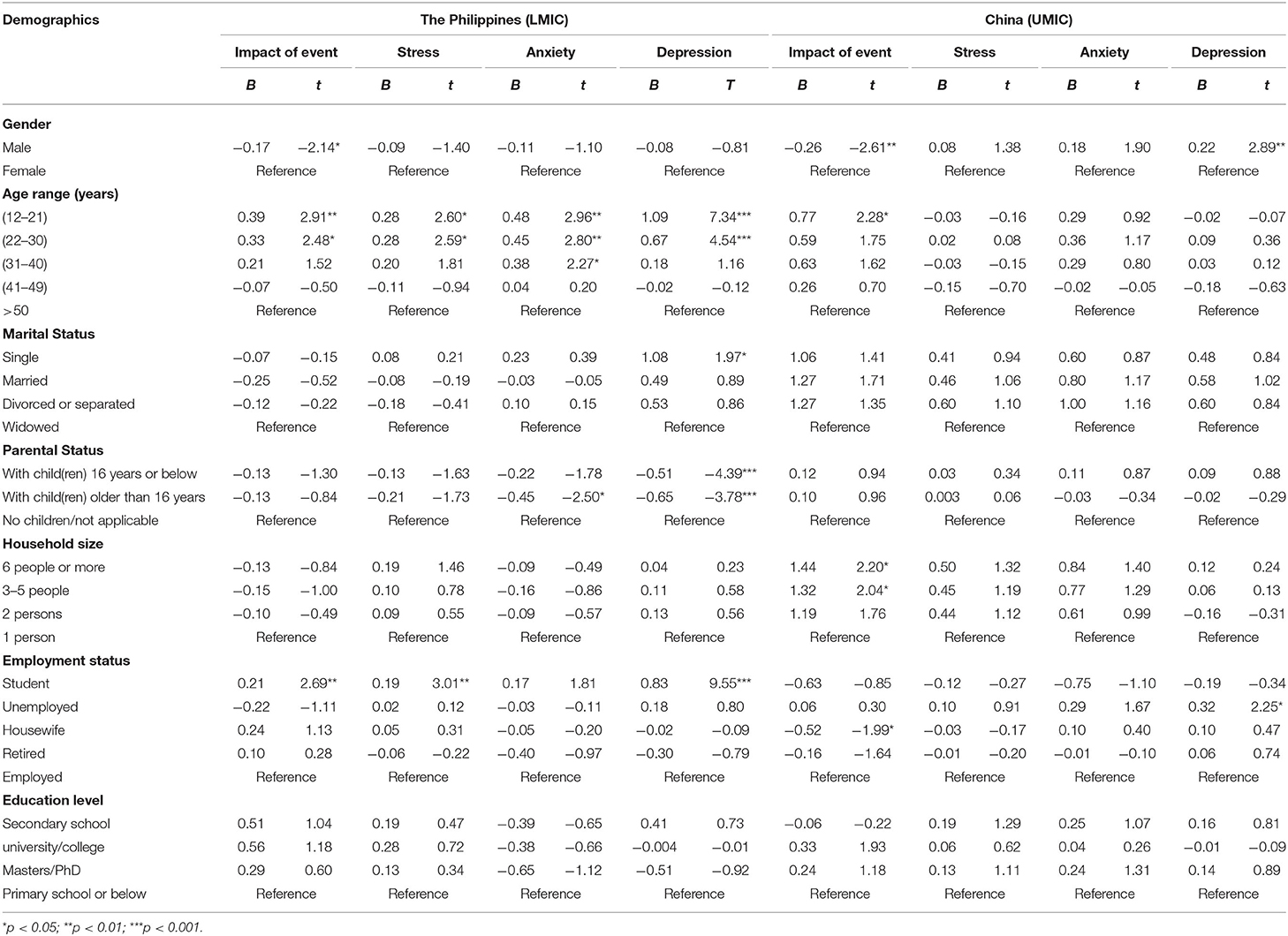

Table 2 shows significant predictors of vaccine hesitancy in both Filipino and Malaysian samples. Among Filipino participants, multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that factors associated with higher vaccine hesitancy included women (OR, 1.51, 95% CI, 1.14–2.00; p = 0.004), residing in a rural community (OR, 1.45, 95% CI, 1.07–1.95; p = 0.015), and having lower income (OR, 1.62, 95% CI, 1.20–2.19; p = 0.001). Among Malaysian participants, women (OR, 1.51, 95% CI, 1.14–2.00; p = 0.004), being aged 25–34 (vs. 18–24; OR, 1.52, 95% CI, 1.48–2.21; p = 0.027), Christians (OR, 2.45, 95% CI, 1.66–3.62; p < 0.001), completing tertiary education (OR, 2.17, 95% CI, 1.63–2.88; p < 0.001), social media use (OR, 11.59, 95% CI, 5.63–23.84; p < 0.001), and information-seeking behaviours (OR, 2.50, 95% CI, 1.74–3.61; p < 0.001) were predictors of higher vaccine hesitancy, whereas having a health impairment (OR, 0.49, 95% CI, 0.30–0.78; p = 0.003) and higher self-reported ratings on subjective social status (OR, 0.82, 95% CI, 0.75–0.89; p < 0.001) were associated with lower vaccine hesitancy.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742.t002

Table 3 shows significant predictors of vaccine confidence in both Filipino and Malaysian samples. Factors positively associated with higher vaccine confidence among Filipino participants included higher self-reported ratings on subjective social status (OR, 1.16, 95% CI, 1.07–1.25; p < 0.001), whereas factors associated with lower vaccine confidence included women (OR, 0.72, 95% CI, 0.54–0.96; p = 0.026) and information-seeking behaviours (OR, 0.63, 95% CI, 0.49–0.81; p < 0.001). Among Malaysian participants, factors positively associated with higher vaccine confidence included women (OR, 1.27, 95% CI, 1.18–1.60; p = 0.035), completing tertiary education (OR, 1.31, 95% CI, 1.03–1.66; p = 0.026), and higher self-reported ratings on subjective social status (OR, 1.08, 95% CI, 1.00–1.16; p = 0.036). Factors negatively associated with lower vaccine confidence included residing in a rural community (OR, 0.63, 95% CI, 0.47–0.87; p = 0.004), Christians (OR, 0.50, 95% CI, 1.20–2.24; p < 0.001), Buddhists (OR, 0.15., 95% CI, 0.10–0.22; p < 0.001), Hindus (OR, 0.24., 95% CI, 0.17–0.34; p = 0.004), information-seeking behaviours (OR, 0.42, 95% CI, 0.31–0.58; p < 0.001), and determining relevance of online information (OR, 0.68, 95% CI, 0.51–0.92; p = 0.013).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742.t003

Malaysia and the Philippines are among the most populous countries in Southeast Asia. While the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been permanent in the Philippines, it has been shown thus far to be temporary in Malaysia [ 26 ]. Between January and October 2020, around 30,000 Malaysians had been infected by the virus with a mortality rate of 0.79%, while approximately 380,000 cases of COVID-19 were detected in the Philippines with a mortality rate of 1.9% [ 2 ]. Further, 61.8% of Malaysians had completed their vaccination up until September 2021, while the percentage of completed vaccinations during the same period in the Philippines was only 19.2% [ 27 ]. Vaccine uptake is likely to be a key determining factor in the outcome of a pandemic. Knowledge around factors which predict vaccine hesitancy and confidence is of the utmost important in order to improve vaccination rates. Thus, the core aims of this research were to determine levels of hesitancy and confidence in COVID-19 vaccines among general adults in the Philippines and Malaysia, and to identify behavioural or environmental predictors that are significantly associated with these outcomes.

First, while there were no significant differences in ratings of confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine between Filipino and Malaysian participants, Filipino (compared to Malaysian) participants expressed greater vaccine hesitancy. This may be a consequence of previous vaccine scares in the years leading up to the pandemic, including the Dengvaxia controversy in 2016 [ 7 , 9 ]. Systematic reviews demonstrated that, by the end of 2020, the highest vaccine acceptance was in China, Malaysia, and Indonesia [ 28 , 29 ]. The authors postulated that this elevated awareness was due to being among the first countries affected by the virus, hence resulting in greater confidence in vaccines [ 28 ].

Next, this study shows that women expressed greater vaccine hesitancy in both countries. The evidence base shows mixed findings, with other studies reporting higher hesitancy in women [ 30 ] or in men [ 31 ]. In some countries, the gender gap is not as substantial as others. In a large global study conducted in countries such as Russia and the United States, it was found that there is greater gender gap in vaccine hesitancy among men and women compared to countries such as Nepal and Sierra Leone [ 32 , 33 ]. Unsurprisingly, what drives this hesitancy is the inclusion of pregnant women, where studies have consistently demonstrated that this population is more hesitant toward vaccination due to concerns for their babies [ 34 ]. Hence, after taking all consideration into account, gender differences in vaccine hesitancy cannot be supported with certainty. This also emphasises the need for tailored health promotion towards the key populations at risk.

There are clear differences in predictors of vaccine hesitancy in the Philippines and Malaysia. However, when results for both countries were combined, women, urban dwellers, those of Christian faith, those with higher educational attainment, higher self-reported social class, social media use, and information-seeking tendencies remained as predictors of hesitancy. Urban-dwellers and individuals with more years of education have previously been demonstrated as predictors for vaccine hesitancy [ 35 ], but contradictory results have also previously been shown [ 36 , 37 ]. Urban residents are typically more connected to the internet and social media and, thus, may be more exposed to vaccine-related misinformation than rural inhabitants who have fewer sources of information available to them [ 12 – 14 ]. Nevertheless, reports have shown higher vaccine refusals among those with strong religious beliefs such as the Amish Community in the United States and the Orthodox Protestants in the Netherlands [ 38 ], as well as some Muslim groups in Pakistan [ 18 ].

Frequent social media use is the only strong predictor for vaccine hesitancy in this study, followed by information-seeking behaviours. Research has identified that the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine is the primary concern that people have, including beliefs in available information [ 15 – 17 ]. Unfortunately, high internet literacy is a double-edged sword, since participants in this study preferred to seek information through social media, and thus may have been exposed to inaccurate information regarding COVID-19 vaccine. Previous studies have associated higher vaccine hesitancy with misinformation about the virus and vaccines [ 18 ], particularly if they relied heavily on social media as a key source of vaccine-related information [ 19 ]. A 2022 systematic review discovered that high social media use is the main driver of vaccine hesitancy across all countries around the globe, and is especially prominent in Asia [ 39 ]. Furthermore, vaccine acceptance and uptake improved among those who obtained their information from healthcare providers compared to relatives or the internet [ 40 ].

In terms of vaccine confidence, our findings show that those with higher subjective social status have higher confidence in vaccination, consistent with previous studies describing how those with a higher income had expressed willingness to pay for their COVID-19 vaccination if necessary [ 32 , 41 , 42 ]. Further, those of Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu faiths, as well as those with a tendency to seek out information, were associated with lower vaccine confidence. This is in keeping with the previous findings demonstrating that strong religious convictions are often tied to mistrust of authorities and beliefs about the cause of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is fuelled by social media [ 43 ]. Furthermore, concern on the permissibility of these vaccines in their religion reduces its acceptability [ 10 ]. However, it is interesting to note that, while the majority in Malaysia are Muslims, it did not reduce the rate of vaccine acceptance and confidence in the country.

These findings have important implications for health authorities and governments in areas focusing on improving vaccination uptake. Misinformation about vaccination greatly hampers vaccination efforts. Thus, not only is it important to understand how specific population groups are influenced by digital platforms such as social media, but it is imperative to provide the right information driven by governmental and non-governmental organisations [ 39 ]. This could be achieved by having community-specific public education and role modelling from local health and public officials, which has been shown to increase public trust [ 44 ]. Since the primary reason for hesitancy is concern about the safety of vaccines, it is crucial that education programmes stress the effectiveness and importance of COVID-19 vaccinations [ 45 ]. Participants in this study coped with the pandemic by seeking out new information, but they sought information from social media when information from the authorities was lacking or were viewed as untrustworthy, which may have contained erroneous information. One way to deter this is to empower information-technology companies to monitor vaccine-related materials on social media, remove false information, and create correct and responsible content [ 44 ].

Furthermore, behavioural change techniques have been found to be useful in stressing the consequences of rejecting the vaccine on physical and mental health [ 46 ]. The most effective “nudging” interventions included offering incentives for parents and healthcare workers, providing salient information, and employing trusted figures to deliver this information [ 47 ]. Finally, since religious concerns have been prominent in reducing vaccine confidence and increasing hesitancy in this study, it is important to tailor messages to include information related to religion, and the use of religious leaders to spread these messages [ 48 ]. These are all important factors for increasing uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine, but also may be relevant in acceptability of routine immunisations as countries look to transition towards a post-pandemic delivery of healthcare.

A limitation of this study includes its cross-sectional design and the heterogeneity among participants, which meant that temporal changes in attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines across time were not captured. Further, the need for internet access among Filipino and Malaysian participants limited the representativeness of the sample population. Thus, certain demographic were under-represented, including Filipino and Malaysian individuals over the age of 45, and people of lower socio-economic status. The surveys were also implemented in English, which may have limited the participation of target participants who were not fluent in English. In addition, due to space limitations, vaccine hesitancy and confidence were each captured using one item, which raises concerns of the items’ validity and reliability. Finally, not all independent variables were accounted for, including medical mistrust [ 49 ], vaccine knowledge [ 50 ], and specific social media platforms used [ 11 ]. We also did not assess whether participants had received any doses of the COVID-19 vaccine previously. Future research should include more important predictors to build a broader picture of vaccine-related hesitancy and confidence in the Philippines and Malaysia, and more items should be utilised to tap into these concepts more comprehensively. Despite these limitations, the core strength of this study relates to its relatively large number of participants from both countries, and its comprehensive analysis of predictors to provide as a starting point going forward.

Conclusions

The main aims of this research were to determine levels of hesitancy and confidence in COVID-19 vaccines among unvaccinated individuals in the Philippines and Malaysia, and to identify predictors significantly associated with these outcomes. Predictors of vaccine hesitancy in this study included the use of social media, information-seeking, and Christianity. Higher socioeconomic status positively predicted vaccine confidence. However, being Christian, Buddhist or Hindu, and the tendency to seek information online, were predictors of hesitancy. Efforts to improve uptake of COVID-19 vaccination must be centred upon providing accurate information to specific communities using local authorities, health services and other locally-trusted voices (such as religious leaders), and for the masses through social media. Further studies should focus on the development of locally-tailored health promotion strategies to improve vaccination confidence and increase the uptake of vaccination–especially in light of the Dengvaxia crisis in the Philippines.

Supporting information

S1 file. inclusivity in global research questionnaire..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742.s001

- 1. Ritchie H, Mathieu E, Rodés-Guirao L, Appel C, Giattino C, Ortiz-Ospina E, et al. Coronavirus pandemic. Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Available from https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations .

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 3. Ritchie H, Mathieu E, Rodés-Guirao L, Appel C, Giattino C,Ortiz-Ospina E, et al. Philippines: Coronavirus pandemic country profile. Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Available from https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/philippines .

- 9. Mendoza RU, Valenzuela, S, Dayrit, M. A Crisis of Confidence: The Case of Dengvaxia in the Philippines. SSRN: doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3519736.

- Open access

- Published: 21 September 2021

Local government responses for COVID-19 management in the Philippines

- Dylan Antonio S. Talabis 1 , 2 ,

- Ariel L. Babierra 1 , 2 ,

- Christian Alvin H. Buhat 1 , 2 ,

- Destiny S. Lutero 1 , 2 ,

- Kemuel M. Quindala III 1 , 2 &

- Jomar F. Rabajante 1 , 2 , 3

BMC Public Health volume 21 , Article number: 1711 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

551k Accesses

25 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Responses of subnational government units are crucial in the containment of the spread of pathogens in a country. To mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Philippine national government through its Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases outlined different quarantine measures wherein each level has a corresponding degree of rigidity from keeping only the essential businesses open to allowing all establishments to operate at a certain capacity. Other measures also involve prohibiting individuals at a certain age bracket from going outside of their homes. The local government units (LGUs)–municipalities and provinces–can adopt any of these measures depending on the extent of the pandemic in their locality. The purpose is to keep the number of infections and mortality at bay while minimizing the economic impact of the pandemic. Some LGUs have demonstrated a remarkable response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The purpose of this study is to identify notable non-pharmaceutical interventions of these outlying LGUs in the country using quantitative methods.

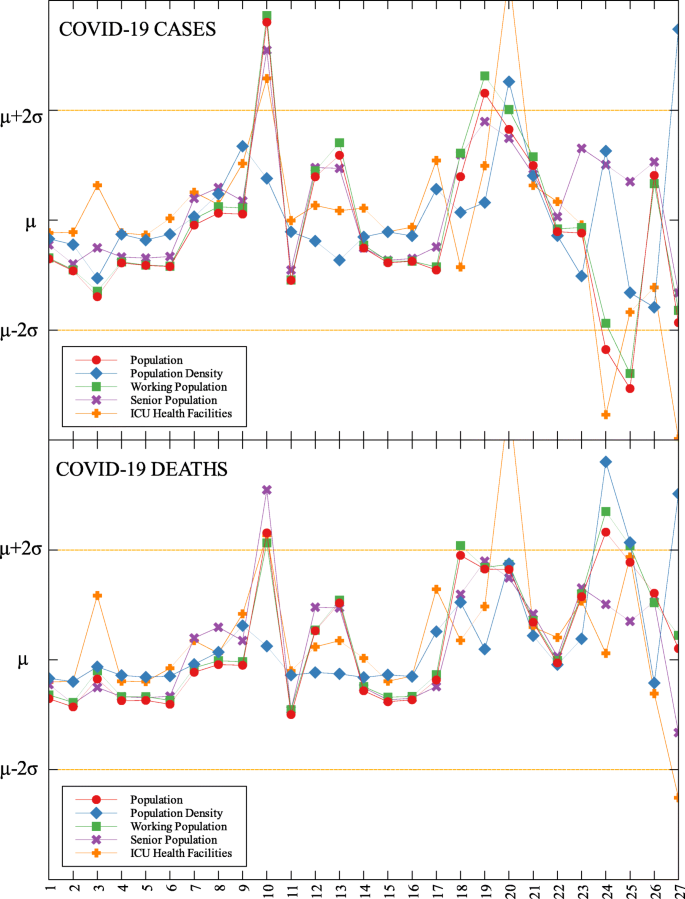

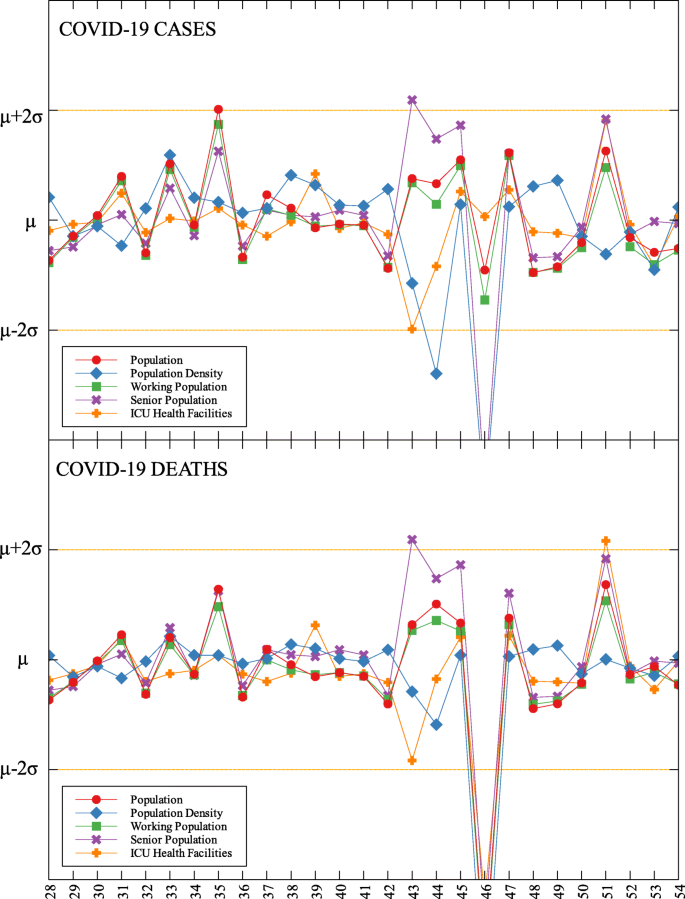

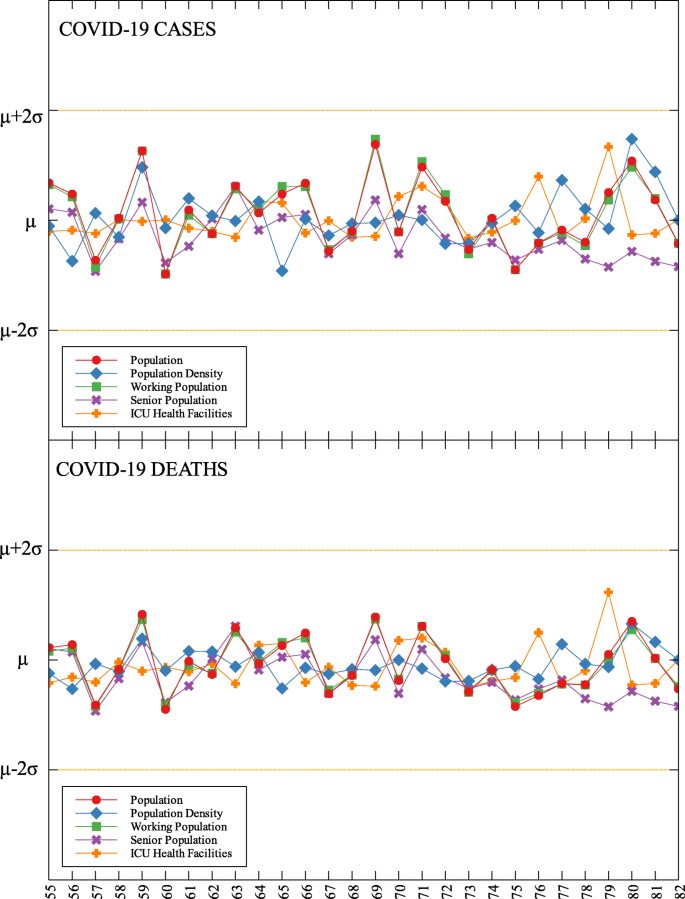

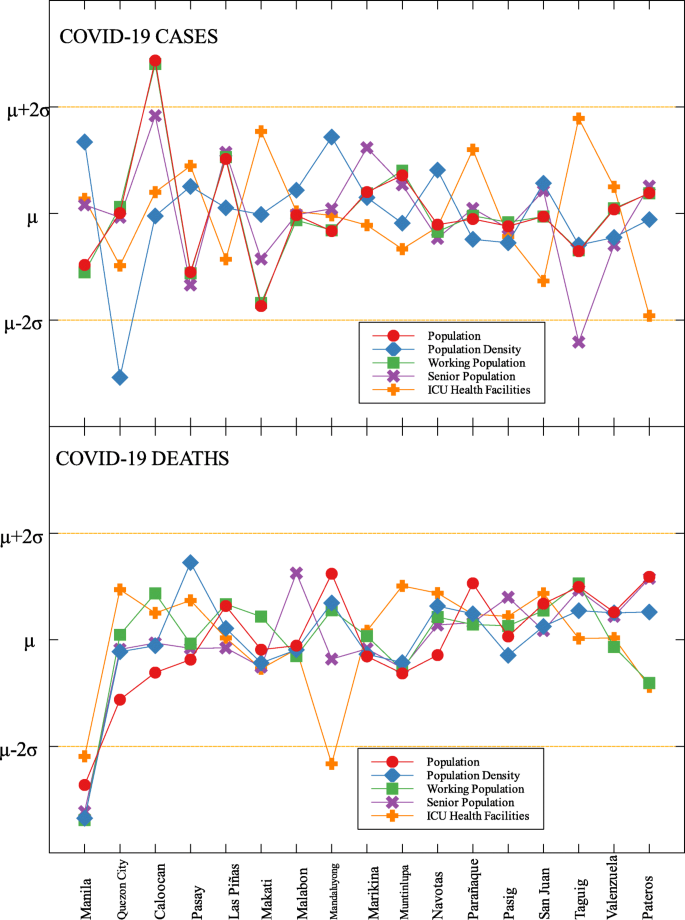

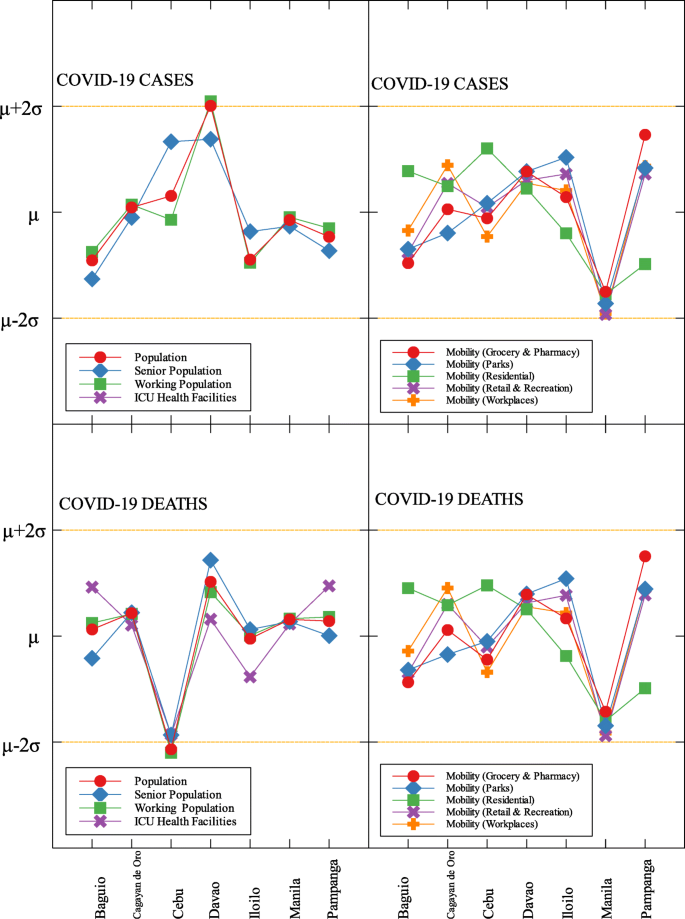

Data were taken from public databases such as Philippine Department of Health, Philippine Statistics Authority Census, and Google Community Mobility Reports. These are normalized using Z-transform. For each locality, infection and mortality data (dataset Y ) were compared to the economic, health, and demographic data (dataset X ) using Euclidean metric d =( x − y ) 2 , where x ∈ X and y ∈ Y . If a data pair ( x , y ) exceeds, by two standard deviations, the mean of the Euclidean metric values between the sets X and Y , the pair is assumed to be a ‘good’ outlier.

Our results showed that cluster of cities and provinces in Central Luzon (Region III), CALABARZON (Region IV-A), the National Capital Region (NCR), and Central Visayas (Region VII) are the ‘good’ outliers with respect to factors such as working population, population density, ICU beds, doctors on quarantine, number of frontliners and gross regional domestic product. Among metropolitan cities, Davao was a ‘good’ outlier with respect to demographic factors.

Conclusions

Strict border control, early implementation of lockdowns, establishment of quarantine facilities, effective communication to the public, and monitoring efforts were the defining factors that helped these LGUs curtail the harm that was brought by the pandemic. If these policies are to be standardized, it would help any country’s preparedness for future health emergencies.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of cases have already reached 82 million worldwide at the end of 2020. In the Philippines, the number of cases exceeded 473,000. As countries around the world face the continuing threat of the COVID-19 pandemic, national governments and health ministries formulate, implement and revise health policies and standards based on recommendations by world health organization (WHO), experiences of other countries, and on-the-ground experiences. Early health measures were primarily aimed at preventing and reducing transmission in populations at risk. These measures differ in scale and speed among countries, as some countries have more resources and are more prepared in terms of healthcare capacity and availability of stringent policies [ 1 , 2 ].

During the first months of the pandemic, several countries struggled to find tolerable, if not the most effective, measures to ‘flatten’ the COVID-19 epidemic curve so that health facilities will not be overwhelmed [ 3 , 4 ]. In responding to the threat of the pandemic, public health policies included epidemiological and socio-economic factors. The success or failure of these policies exposed the strengths or weaknesses of governments as well as the range of inequalities in the society [ 5 , 6 ].

As national governments implemented large-scale ‘blanket’ policies to control the pandemic, local government units (LGUs) have to consider granular policies as well as real-time interventions to address differences in the local COVID-19 transmission dynamics due to heterogeneity and diversity in communities. Some policies in place, such as voluntary physical distancing, wearing of face masks and face shields, mass testing, and school closures, could be effective in one locality but not in another [ 7 – 9 ]. Subnational governments like LGUs are confronted with a health crisis that have economic, social and fiscal impact. While urban areas have been hot spots of the COVID-19 pandemic, there are health facilities that are already well in placed as compared to less developed and deprived rural communities [ 10 ]. The importance of local narratives in addressing subnational concerns are apparent from published experiences in the United States [ 11 ], China [ 12 , 13 ], and India [ 14 ].

In the Philippines, the Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF) was convened by the national government in January 2020 to monitor a viral outbreak in Wuhan, China. The first case of local transmission of COVID-19 was confirmed on March 7, 2020. Following this, on March 8, the entire country was placed under a State of Public Health Emergency. By March 25, the IATF released a National Action Plan to control the spread of COVID-19. A community quarantine was initially put in place for the national capital region (NCR) starting March 13, 2020 and it was expanded to the whole island of Luzon by March 17. The initial quarantine was extended up to April 30 [ 5 , 15 ]. Several quarantine protocols were then implemented based on evaluation of IATF:

Community Quarantine (CQ) refers to restrictions in mobility between quarantined areas.

In Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ), strict home quarantine is implemented and movement of residents is limited to access essential goods and services. Public transportation is suspended. Only economic activities related to essential and utility services are allowed. There is heightened presence of uniformed personnel to enforce community quarantine protocols.

Modified Enhanced Community Quarantine (MECQ) is implemented as a transition phase between ECQ and GCQ. Strict home quarantine and suspension of public transportation are still in place. Mobility restrictions are relaxed for work-related activities. Government offices operates under a skeleton workforce. Manufacturing facilities are allowed to operate with up to 50% of the workforce. Transportation services are only allowed for essential goods and services.

In General Community Quarantine (GCQ), individuals from less susceptible age groups and without health risks are allowed to move within quarantined zones. Public transportation can operate at reduced vehicle capacity observing physical distancing. Government offices may be at full work capacity or under alternative work arrangements. Up to 50% of the workforce in industries (except for leisure and amusement) are allowed to work.

Modified General Community Quarantine (MGCQ) refers to the transition phase between GCQ and the New Normal. All persons are allowed outside their residences. Socio-economic activities are allowed with minimum public health standard.

LGUs are tasked to adopt, coordinate, and implement guidelines concerning COVID-19 in accordance with provincial and local quarantine protocols released by the national government [ 16 ].

In this study, we identified economic and demographic factors that are correlated with epidemiological metrics related to COVID-19, specifically to the number of infected cases and number of deaths [ 17 , 18 ]. At the regional, provincial, and city levels, we investigated the localities that differ with the other localities, and determined the possible reasons why they are outliers compared to the average practices of the others.

We categorized the data into economic, health, and demographic components (See Table 1 ). In the economic setting, we considered the number of people employed and the number of work hours. The number of health facilities provides an insight into the health system of a locality. Population and population density, as well as age distribution and mobility, were used as the demographic indicators. The data (as of November 10, 2020) from these seven factors were analyzed and compared to the number of deaths and cumulative cases in cities, provinces or regions in the Philippines to determine the outlier.

The Philippine government’s administrative structure and the availability of the data affected its range for each factor. Regional data were obtained for the economic component. For the health and demographic components, data from cities and provinces were retrieved from the sources. Due to the NCR exhibiting the highest figures in all key components, an investigation was conducted to identify an outlier among its cities. The z -transform

where x is the actual data, μ is the mean and σ is the standard deviation were applied to normalize the dataset. Two sets of normalized data X and Y were compared by assigning to each pair ( x , y ), where x ∈ X and y ∈ Y , its Euclidean metric d given by d =( x − y ) 2 . Here, the Y ’s are the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths, and X ’s are the other demographic indicators. Since 95% of the data fall within two standard deviations from the mean, this will be the threshold in determining an outlier. This means that if a data pair ( x , y ) exceeds, by two standard deviations, the mean of the Euclidean metric values between the sets X and Y , the pair is assumed to be an outlier.

To identify a good outlier, a bias computation was performed. In this procedure, Y represents the normalized data set for the number of deaths or the number of cases while X represents the normalized data set for every factor that were considered in this study. The bias is computed using the metric

for all x in X and y in Y . To categorize a city, province, or region as a good outlier, the bias corresponding to this locality must exceed two standard deviations from the mean of all the bias computations between the sets X and Y .

Results and discussion

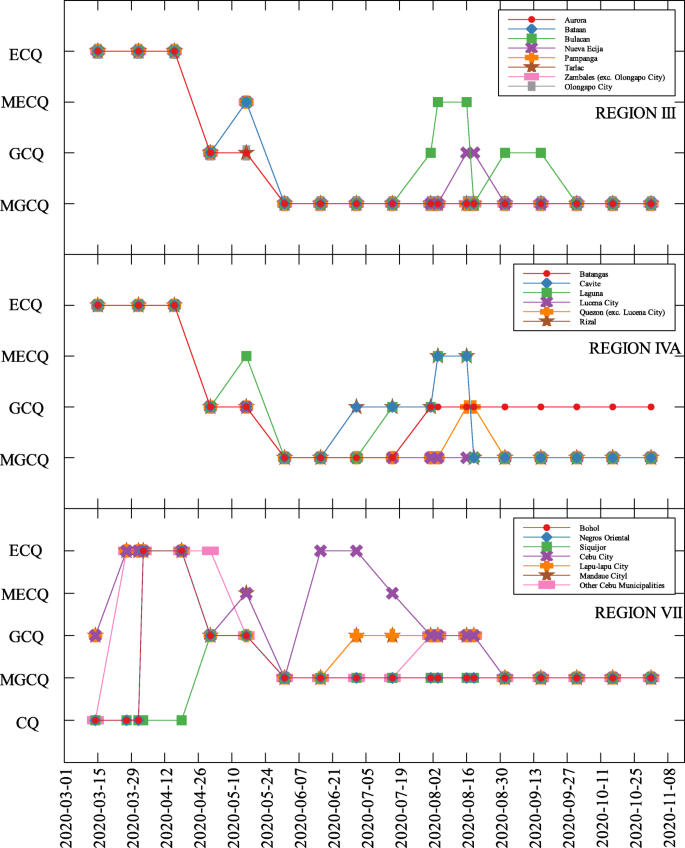

The data used were the reported COVID-19 cases and deaths in the Philippines as of November 10, 2020 which is 240 days since community lockdowns were implemented in the country. Figure 1 shows the different lockdowns implemented per province since March 15. It can be seen that ECQ was implemented in Luzon and major cities in the country in the first few weeks since March 15, and slowly eased into either GCQ or MGCQ as time progressed. By August, the most stringent lockdown was MECQ in the National Capital Region (NCR) and some nearby provinces. Places under MECQ on September were Iloilo City, Bacolod City, and Lanao del Sur, with the last province as the lone community to be placed under MECQ the month after. By November 1, 2020, communities were either placed under GCQ or MGCQ.

COVID-19 community quarantines in Regions III, IVA and VII

Comparison of economic, health, and demographic components and COVID-19 parameters

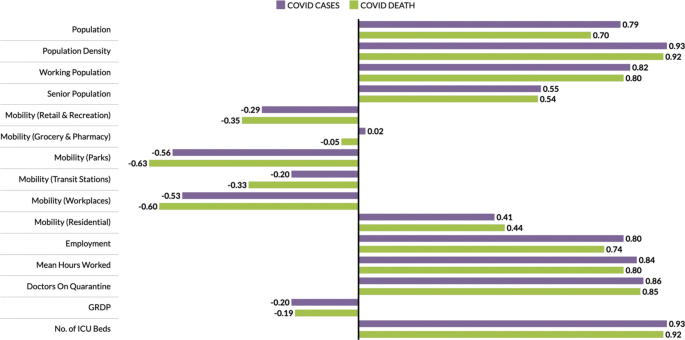

The economic, health and demographic components were compared to COVID-19 cases and deaths. These comparisons were done for different community levels (regional, provincial, city/metropolitan) (See Tables 2 , 3 , and 4 ). Figure 2 summarizes the correlation of components to COVID-19 cases and deaths at the regional level. In all components, correlations with other parameters to both COVID-19 cases and deaths are close. Every component except Residential Mobility and GRDP have slightly higher correlation coefficient for COVID-19 cases as compared to COVID-19 deaths.

Correlation of components to COVID-19 cases and deaths at the regional level

Among the components, the number of ICU beds component has the highest correlation with COVID-19 parameters. This makes sense as this is one of the first-degree measures of COVID-19 transmission. Population density comes in second, followed by mean hours worked and working population, which are all related to how developed the region is economy-wise. Regions having larger population density also have a huge working population and longer working hours [ 24 ]. Thus, having a huge population density implies high chance of having contact with each other [ 25 , 26 ]. Another component with high correlation to the cases and deaths is the number of doctors on quarantine, which can be looked at two ways; (i) huge infection rate in the region which is the reason the doctors got exposed or are on quarantine, and (ii) lots of doctors on quarantine which resulted to less frontliners taking care of the infected individuals. All definitions of mobility and the GDP are not strongly correlated to any of the COVID-19 measures.

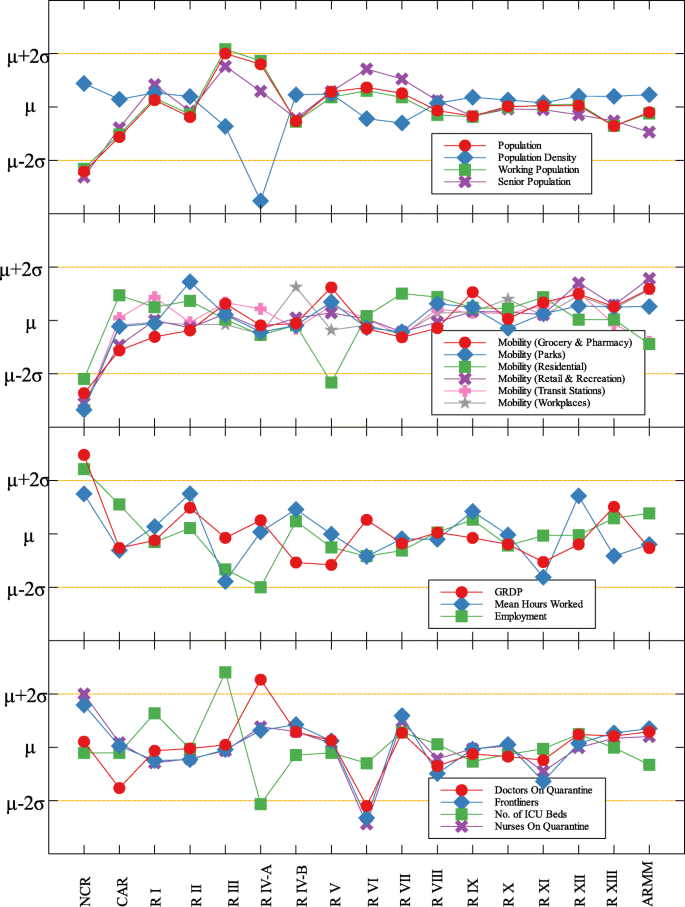

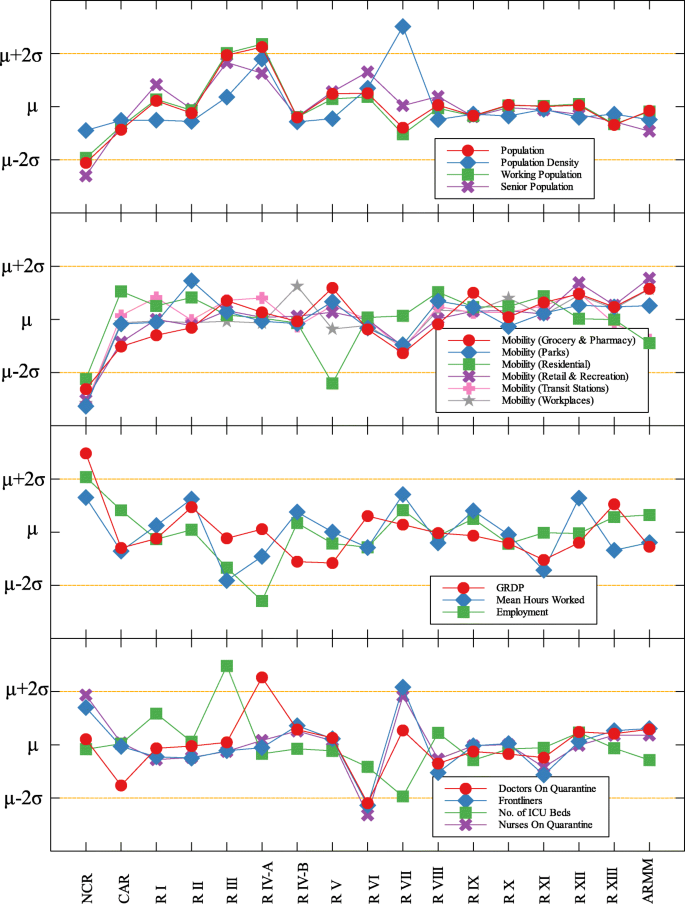

In each data set, outliers were identified depending on their distance from the mean. For simplicity, we denote components that are compared with COVID-19 cases by (C) and with COVID-19 deaths by (D). The summary of outliers among regions in the Philippines is shown in Figs. 3 and 4 . Data is classified according to groups of component. In each outlier region, non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPI) implemented and their timing are identified.

Outliers among regions in the Philippines with respect to COVID-19 cases

Outliers among regions in the Philippines with respect to COVID-19 deaths

Region III is an outlier in terms of working population (C) and the number of ICU beds (C) (see Fig. 5 and Table 5 ). This means that considering the working population of the region, the number of COVID-19 infections are better than that of other regions. Same goes with the number of ICU beds in relation to COVID-19 deaths. Region III is comprised of Aurora, Bataan, Nueva Ecija, Pampanga, Tarlac, Zambales, and Bulacan. This good performance might be attributed to their performance especially on their programs against COVID-19. As early as March 2020, the region had been under a community lockdown together with other regions in Luzon. Being the closest to NCR, Bulacan has been the most likely to have high number of COVID-19 cases in the region. But the province responded by opening infection control centers which offer free healthcare, meals, and rooms for moderate-severe COVID-19 patients [ 27 ]. They have also implemented strict monitoring of entry-exit borders, organization of provincial task force and incident command center, establishment of provincial quarantine facilities for returning overseas Filipino workers, mandated municipal quarantine facilities for asymptomatic cases, and mass testing, among others [ 27 ]. Most of which have been proven effective in reducing the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths [ 28 ].

Outliers among the provinces in Luzon with respect to COVID-19 cases and deaths

Outliers among the provinces in Visayas with respect to COVID-19 cases and deaths

Outliers among the provinces in Mindanao with respect to COVID-19 cases and deaths

Region IV-A is an outlier in terms of population and working population (D) and doctors on quarantine (D) (see Fig. 5 and Table 5 ). Considering their population and working population, the COVID-19 death statistics show better results compared to other regions. Same goes with the number of doctors in the region which are in quarantine in relation to the reported COVID-19 deaths. This shows that the region is doing well in terms of decreasing the COVID-19 fatalities compared to other regions in terms of populations and doctors on quarantine. Region IV-A is comprised of Batangas, Cavite, Laguna, Quezon, and Rizal. Same with Region III, they have been under the community lockdown since March of last year. Provinces of the region such as Rizal have been proactive in responding to the epidemic as they have already suspended classes and distributed face masks even before the nationwide lockdown [ 29 ]. Despite being hit by natural calamities, the region still continue ramping up the response to the pandemic through cash assistance, first aid kits, and spreading awareness [ 30 ].

An interesting result is that NCR, the center of the country and the most densely populated, is a good outlier in terms of GRDP (C) and GRDP (D). Cities in the region launched various programs in order to combat the disease. They have launched mass testings with Quezon City, Taguig City, and Caloocan City starting as early as April 2020. Pasig City started an on-the-go market called Jeepalengke. Navotas, Malabon, and Caloocan recorded the lowest attack rate of the virus. Caloocan city had good strategies for zoning, isolation and even in finding ways to be more effective and efficient. Other programs also include color-coded quarantine pass, and quarantine bands. It is also possible that NCR may just have a very high GRDP compared to other regions. A breakdown of the outliers within NCR can be seen in Fig. 8 .

Outliers in the national capital region with respect to COVID-19 cases and deaths