What is Music Therapy and How Does It Work?

Perhaps the music leaves you feeling calmer. Or happy. Or, let’s face it, downright sad. I am sure all of us can attest to the power of music.

Did you know, however, that music therapy is in itself an evidence-based therapy? Keep reading to learn more about the profession of music therapy.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive CBT Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will provide you with detailed insight into Positive CBT and give you the tools to apply it in your therapy or coaching.

This Article Contains:

A look at the psychology, a brief history of music therapy, research and studies, the different types and methods of music therapy, a list of music therapy techniques, what does a music therapist do, the best instruments to use in music therapy, available music therapy apps, voices: a world forum for music therapy, what is music therapy perspectives.

- The 5 Best Books on the Topic

Recommended Articles

5 recommended youtube videos, a take-home message.

Bruscia (1991) defined music therapy as ‘ an interpersonal process in which the therapist uses music and all of its facets to help patients to improve, restore or maintain health ’ (Maratos, Gold, Wang & Crawford, 2008).

A little later, in 1998, Bruscia suggested another alternative definition of music therapy as ‘ a systematic process of intervention wherein the therapist helps the client to promote health, using musical experiences and the relationships that develop through them as dynamic forces of change ’ (Geretsegger, Elefant, Mössler & Gold, 2014).

Does music therapy simply consist of music used therapeutically? As Bruscia’s definitions demonstrate, music therapy is much more complex. It shouldn’t be confused with ‘music medicine’ – which is music interventions delivered by medical or healthcare professionals (Bradt & Dileo, 2010).

Music therapy, on the other hand, is administered by trained music therapists (Bradt & Dileo, 2010).

How does music therapy work? Well, it is claimed that five factors contribute to the effects of music therapy (Koelsch, 2009).

Modulation of Attention

The first aspect is the modulation of attention. Music grabs our attention and distracts us from stimuli that may lead to negative experiences (such as worry, pain, anxiety and so on). This may also explain the anxiety and pain-reducing effects of listening to music during medical procedures (Koelsch, 2009).

Modulation of Emotion

The second way music therapy work is through modulation of emotion . Studies have shown that music can regulate the activity of brain regions that are involved in the initiation, generation, maintenance, termination, and modulation of emotions (Koelsch, 2009).

Modulation of Cognition

Music also modulates cognition. Music is related to memory processes (including the encoding, storage, and decoding of musical information and events related to musical experiences) (Koelsch, 2009). It is also involved in the analysis of musical syntax and musical meaning (Koelsch, 2009).

Modulation of Behavior

Music therapy also works through modulating behavior. Music evokes and conditions behaviors such as the movement patterns involved in walking, speaking and grasping (Koelsch, 2009).

Modulation of Communication

Music also affects communication. In fact, music is a means of communication. Therefore, music can play a significant role in relationships, as alluded to in the definition of music therapy (Koelsch, 2009).

- Musical interaction in music therapy, especially musical improvisation, serves as a non-verbal and pre-verbal language (Geretsegger et al., 2014).

- It allows people who are verbal to gain access to pre-verbal experiences (Geretsegger et al., 2014).

- It also gives non-verbal people the chance to communicate with others without words (Geretsegger et al., 2014).

- It allows all people to interact on a more emotional, relationship-oriented way than may be possible relying on verbal language (Geretsegger et al., 2014).

Interaction also takes place with listening to music by a process that generally includes choosing music that has meaning for the person, such as the music reflecting an issue that the person is currently occupied with (Geretsegger et al., 2014).

Wherever possible, individuals are encouraged to reflect on personal issues that relate to the music, or, associations that the music brings up. For individuals who have verbal abilities, another important part of music therapy is to reflect verbally on the musical processes (Geretsegger et al., 2014).

Looking at a psychological theory of music therapy is extremely challenging, given the fact that there are multiple ideas regarding the mechanisms of music used as a therapeutic means (Hillecke, Nickel & Volker Bolay, 2005).

The psychology of music is a relatively new area of study (Wigram, Pedersen & Bonde, 2002). Music therapy is a multi-disciplinary field, and the area of music psychology is an innovative interdisciplinary science drawing from the fields of musicology, psychology, acoustics, sociology, anthropology, and neurology (Hillecke et al., 2005; Wigram et al., 2002).

Psychologists use experiments and diagnostics such as questionnaires, and the paradigm of cognition, to analyze what happens in music therapy (Hillecke et al., 2005).

Important topics in the psychology of music are:

- The function of music in the life and history of mankind

- The function of music in the life and identity of a person

- Auditory perception and musical memory

- Auditory imagery

- The brain’s processing of musical inputs

- The origin of musical abilities and the development of musical skills

- The meaning of music and musical preferences for the forming of identity

- The psychology of music performance and composition (Wigram et al., pp 45 – 46).

In understanding how people hear and perceive musical sounds, a part of music psychology is psychoacoustics – one’s perception of music. Another important facet of the psychology of music is an understanding of the human ear, and also the way the brain is involved in the appreciation and performance of music (Wigram et al., 2002).

Lifespan music psychology refers to an individual’s relationship to music as a lifelong developmental process (Wigram et al., 2002).

The earliest reference to music therapy was a paper called “Musically Physically Considered”, that was published in a Columbian magazine (Greenberg, 2017).

Even long before that, Pythagoras (c.570 – c. 495 BC), the Greek philosopher and mathematician prescribed a variety of musical scales and modes in order to cure an array of physical and psychological conditions (Greenberg, 2017).

However, perhaps the earliest account of the healing properties of music appear in the Jewish bible. In it, the story was that David, a skilled musician, could cure King Saul’s depression through music (Greenberg, 2017).

This was told in Chapter 16 in Prophets:

“And it happened that whenever the spirit of melancholy from God was upon Saul, David would take the lyre (harp) and play it. Saul would then feel relieved and the spirit of melancholy would depart from him”

(1 Samuel, 16:23).

There may even be earlier accounts of music therapy. Whether such religious texts are historically accurate or not, music was conceived as a therapeutic modality when such texts were written (Greenberg, 2017).

Music therapy emerged as a profession in the 20th century after World War I and World War II. Both amateur and professional musicians attended veterans’ hospitals to play for the veterans who had suffered physical and emotional trauma (The American Music Therapy Association, n.d.).

The impact of the music on the patients’ physical and emotional responses saw the doctors and nurses requesting to hire the musicians. It became apparent that the hospital musicians required training before starting, and thus ensued the beginning of music therapy education (The American Music Therapy Association, n.d.).

Download 3 Free Positive CBT Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to find new pathways to reduce suffering and more effectively cope with life stressors.

Download 3 Free Positive CBT Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

To begin this discussion into musical therapy research, I will share a couple of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Reviews are systematic reviews that are internationally recognized as the highest standard in evidence-based health care.

A Cochrane Review of 5 studies examining music used in different ways as a part of the psychological treatment of people with depression found that reporting of the studies was poor. It did, however, find that most of the studies that made up the review did show positive effects in reducing depressive symptoms (Maratos et al., 2008). Therefore, the authors suggested that further research in this area is necessary.

Another Cochrane Review looked at 10 studies (a total of 165 participants) that assessed the effect of music therapy interventions that were conducted with children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) over periods ranging from one week to seven months (Geretsegger et al., 2014).

Individuals with ASD experience impairments in social interaction and communication. Music therapy provides a means of communication and expression through musical experiences and the relationships that develop through them (Geretsegger et al., 2014).

Geretsegger and colleagues (2014) found that in terms of social interaction within the context of therapy, music therapy was associated with improvements in the non-verbal communicative skills, verbal communication skills, initiating behavior and social emotional reciprocity of individuals with ASD. However, there was no statistically significant difference in non-verbal communication skills outside the context of the therapy (Geretsegger et al., 2014).

In terms of secondary outcomes, music therapy was found to be superior to ‘placebo’ therapy or standard care in promoting social adaptation and quality of the parent-child relationships (Geretsegger et al., 2014).

In a Cochrane Review, authors found that a limited range of studies suggest that music therapy may be beneficial on improving quality of life in end-of-life care (Bradt & Dileo, 2010). However, the results are derived from studies that have a high risk of bias. Bradt and Dileo (2010) therefore concluded that more research into this particular area is needed.

In other studies, Klassen and colleagues (2008) looked at 19 randomized controlled trials and found that music therapy significantly reduced anxiety and pain in children undergoing medical and dental procedures.

The study also showed that rather than the use of music alone, use of music as a part of a multifaceted intervention may be more effective (Klassen, Liang, Tjosfold, Klassen & Hartling, 2008). The music is used to distract the patient from painful or anxiety-provoking stimuli, and this can also reduce the amount of medication required (Klassen et al., 2008).

Gerdner and Swanson (1993) examined the effects of individualized music in five elderly patients diagnosed with Dementia of Alzheimer’s Type. The patients resided in a long-term care facility and were confused and agitated.

Results from the study, both the immediate effects and the residual effects one hour after the intervention, suggest that individualized music is an alternate approach to management of agitation in confused elderly patients (Gerdner & Swanson, 1993).

Forsblom and colleagues (2009) conducted two parallel interview studies of stroke patients and professional nurses to ascertain the therapeutic role of listening to music in stroke rehabilitation.

They found music listening could be used to help patients relax , improve their mood and afford both mental and physical activation during the early stages of stroke recovery. Music listening was described as a ‘participative rehabilitation tool’ (Forsblom, et al. 2009).

The final study I will review, by Blood and Zatorre (2001) showed that music modulated amygdala activity. Using brain imaging techniques, the researchers played participants a piece of their own favorite music to induce an extremely pleasurable experience – described as “chills”.

In the control condition, participants listened to another participant’s favorite music. The intensity of the ‘chills’ experienced by participants correlated with increases in regional cerebral blood flow in brain areas believe to be involved in reward and emotion. This study supports the argument that music can induce ‘real’ emotions, as the brain regions for emotional processing were modulated by music (Blood & Zatorre, 2001).

Music-based therapy is based on two fundamental methods – the ‘receptive’ listening based method, and the ‘active’ method based on playing musical instruments (Guetin et al., 2009).

There are two receptive methods. The first of these, receptive ‘relaxation’ music therapy is often used in the treatment of anxiety, depression and cognitive disorders . Receptive ‘analytical’ music therapy is used as the medium for ‘analytic’ psychotherapy (Guetin et al., 2009). ‘Music medicine’ generally involves passive listening to pre-recorded music provided by medical personnel (Bradt & Dileo, 2010).

In terms of other types of music therapy, there is the Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music . This was developed by Helen Lindquist Bonny (Smith, 2018). The approach involves guided imagery with music.

With music added, the patient focuses on an image which is used as a starting point to think about and discuss any related problems. Music plays an integral role in the therapy and may be called a ‘co-therapist’. Individual patient needs and goals influence the music that is selected for the session (Smith, 2018).

The Dalcroze Eurythmics is a method used to teach music to students, which can also be used as a form of therapy. Developed by Èmile Jaques-Dalcroze, this method focuses on rhythm, structure, and expression of movement in the learning process. Because this method is apt for improving physical awareness, it helps those patients who have motor difficulties immensely (Smith, 2018).

The therapist may also ‘prescribe’ music medicine or guided imagery recordings containing music for the client to listen to outside the therapy room by making use of a digital psychotherapy platform such as Quenza (pictured here).

Therapists can use modern platforms such as these to send pre-recorded audio clips directly to the client’s smartphone or tablet according to a predetermined schedule.

Likewise, the therapist can track clients’ progress through these audio activities via their own computer or handheld device.

It is thought that Zoltàn Kodàly was the inspiration for the development of the Kodaly philosophy of music therapy (Smith, 2018). It involves using rhythm, notation, sequence, and movement to help the patient learn and heal.

This method has been found to improve intonation, rhythm and music literacy. It also has a positive impact on perceptual function, concept formation, motor skills and learning performance in a therapeutic setting (Smith, 2018).

Neurologic Music Therapy (NMT) is based on neuroscience. It was developed considering the perception and production of music and its influence on the function of the brain and behaviors (Smith, 2018).

NMT uses the variation within the brain both with and without music and manipulates this in order to evoke brain changes which affect the patient. It has been claimed that this type of music therapy changes and develops the brain by engaging with music. This has implications for training motor responses, such as tapping the foot to music. NMT can be used to develop motor skills (Smith, 2018).

Orff-Schulwerk is a music therapy approach developed by Gertrude Orff. When she realized that medicine alone was not sufficient for children with developmental delays and disabilities, Orff formed this model (Smith, 2018).

“Schulwerk”, or ‘school work’ in German, reflects this approach’s emphasis on education. It uses music to help children improve their learning ability. This method also highlights the importance of humanistic psychology and uses music as a way to improve the interaction between the patient and other people (Smith, 2018).

- Listening to live or recorded music

- Learning music-assisted relaxation techniques, such as progressive muscle relaxation or deep breathing

- Singing of familiar songs with live or recorded accompaniment

- Playing instruments, such as hand percussion

- Improvising music on instruments of voice

- Writing song lyrics

- Writing the music for new songs

- Learning to play an instrument, such as piano or guitar

- Creating art with music

- Dancing or moving to live or recorded music

- Writing choreography for music

- Discussing one’s emotional reaction or meaning attached to a particular song or improvisation

This information about what music therapists do was found on the ‘Your Free Career Test’ (n.d.) website.

Music therapists work in a variety of settings, including schools, hospitals, mental health service locations, and nursing homes. They help a variety of different patients/clients.

A music therapist evaluates each clients’ unique needs. They ascertain a client’s musical preferences and devises a treatment plan that is customized for the individual.

Music therapists are part of a multi-disciplinary team, working with other professionals to ensure treatment also works for the client to achieve their goals. For example, if a person is working on strengthening and movement in order to address physical limitations, a music therapist could introduce dance into their treatment plan.

Therapists are advised to follow their own preferences, and as explained by Rachel Rambach (2016) a board-certified music therapist – instruments are the tools of a music therapist and should be specifically chosen based on the needs and goals of clients.

Some instruments are, however, more popular.

Muzique (a company promoting creative art experiences) has listed three instruments that have been proven most effective.

The first of these is the Djembe , or hand drum. Given that this single drum does not have a central melodic component, the client is free to express and connect with the musical rhythms without fear of playing a ‘wrong note’. The use of a small drum also facilitates a connection between the therapist and client by allowing them to be in close proximity.

They can play together at the same time, which may not be possible with a piano or guitar.

The guitar , according to Muzique (n.d.) is generally the top instrument used by music therapists. Again, a guitar can be used in close proximity to a client. The music therapist can also maintain melodic or harmonic control whilst allowing the client to play. The guitar can help maintain control in a group setting, but it can also be soothing and relaxing.

Muzique (n.d.) suggests that the piano is probably the instrument of choice when working with large groups. As the sound of a guitar can be drowned out by other instruments being played by clients, the piano can be more steady and holding background.

The music therapist should be mindful, however, of the apparent physical barrier between themselves and the client, and if possible, have the client sit next to the piano.

When Working With Children

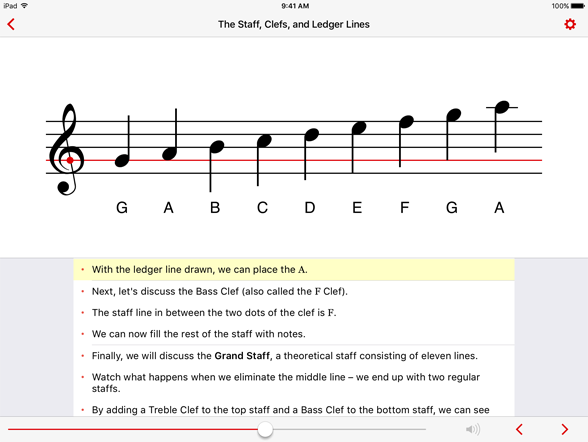

Rachel Rambach (2016) concedes that there are certain instruments that she tends to utilize more often than others in her work with children. These include the 8 note hand bell set , which consists of a group of bells that each have their own color, number and letter of the medical alphabet (which can be ordered by pitch) and the mini guitar (which is very child-friendly and portable).

Another instrument Rambach (2016) likes is the frog guiro , which can be used in various ways – such as a guiro making a croaking sound, like a frog, or as a wood block. Castanets make a fun sound, and also help children acquire a pincer grip.

Rambach (2016) favors fruit shakers , which although they don’t make a unique sound, have a very realistic appearance and thus appeal to children. The cabasa does, on the other hand, make a unique sound and also brings in a tactile element to music therapy.

The cabasa is good for targeting fine and gross motor skills. The ‘lollipop’ drum is light, and not too loud so these are often preferred by Rambach (2016) over bigger paddle drums.

Rambach (2016) thinks every music therapist should have a ukulele . Their sound is sweet and inviting, and the ukulele makes the perfect alternative to a guitar.

They can be used as an accompanying instrument, but also for adapted lessons. Finally, the gathering drum encourages group cohesion in group settings or classes. They encourage children, or adult clients, to work together – sharing, and interacting with others (Rambach, 2016).

Anytune – slow down music BPM

Get it from the App Store .

Get it from Google Play .

Garage Band

This app provides a great tool for song-writing or improvisation. The individual can create literally hundreds of realistic, high-quality sounds (Fandom, n.d.).

Guitarist’s Reference

The app provides guitar triads, arpeggios, a reverse chord finder tool, alternate guitar tunings, chords scale relationships and a guitar chord quiz (Fandom, n.d.).

Magic Piano

The app can also be switched to where you have to hit the right spot (or the note will sound out of tune if not) or just tap the screen with the rhythm. It has 4 different difficulty settings: easy, medium, hard and auto mode that senses the person’s ability after a few songs (Fandom, n.d.).

Real Guitar Free

It has a vast range of options and is perfect for both beginners and experienced guitarists (Sena, 2012).

The following information was found on the ‘ Voices ’ website.

This is an open-access peer-reviewed journal. It welcomes dialogue and discussion across disciplines about music, health, and social change. The journal promotes inclusiveness and socio-cultural awareness. It features a focus on cultural issues and social justice.

‘Voices’ is published by the University of Bergen and NORCE Norwegian Research Centre through GAMUT – The Grieg Academy Music Therapy Research Centre. The vision statement of ‘Voices’ is:

“ Voices: A World Forum for Music Therapy seeks to nurture the profile of music therapy as a global enterprise that is inclusive and has a broad range of influences in the International arena. The forum is particularly interested in encouraging the growth of music therapy in developing countries and intends to foster an exchange between Western and Eastern as well as Northern and Southern approaches to the art and science of music therapy ”.

An official publication of the American Music Therapy Association aim, is to inform readers from both within and outside the music therapy profession.

By disseminating scholarly work, this journal sets out to promote the development of music therapy clinical practice, with a particular focus on clinical benefits.

Music Therapy Perspective seeks to be a resource and forum for music therapists, music therapy students, and educators as well as others from related professions.

The Journal of Music Therapy

The Journal of Music Therapy disseminates research (edited by A. Blythe LaGasse) that advances the science and practice of music therapy. It also provides a forum for current music therapy research and theory, including music therapy tools , book reviews, and guest editorials.

“ Its mission is to promote scholarly activity in music therapy and to foster the development and understanding of music therapy and music-based interventions…The journal strives to present a variety of research approaches and topics, to promote clinical inquiry, and to serve as a resource and forum for researchers, educators, and clinicians in music therapy and related professions ”.

The 5 Best Books on the Topic (Incl. The Music Therapy Handbook)

There is such a lovely selection of books on music therapy, but to be concise, we only reflect on five.

1. Music Therapy Handbook – Barbara Wheeler

This book is a key resource for music therapists and also demonstrates how music therapy can be used by other mental health and medical professionals.

It provides case material and an extensive look at music therapy, including both the basic concepts as well as the emerging clinical approaches. It contains a comprehensive section on clinical applications.

Find the book on Amazon .

2. The New Music Therapist’s Handbook – Suzanne Hanser

This is a revised, updated version of Hanser’s 1987 book. It reflects recent developments in the field of music therapy.

This book serves as a ‘go-to’ resource for both students and professionals. It contains an introduction to music therapy as a profession, provides guidelines for setting up a practice, and describes new clinical applications as well as relevant case studies.

3. Case Studies in Music Therapy – Kenneth Bruscia

This book is suitable as a reference, a textbook for students, or simply to provide an introduction to the field of music therapy.

It is made up of 42 case-histories of children, adolescents and adults receiving group and individual therapy in a range of different settings, in order to demonstrate the process of music therapy from beginning to end.

The book describes various approaches and techniques in music therapy, and captures moving stories of people worldwide who have benefitted from music therapy and the relationships developed with music therapists.

4. Defining Music Therapy – Kenneth Bruscia

Bruscia’s book examines the unique difficulties of defining music within a therapeutic context and, conversely, defining therapy within a music context. It compares and examines more than 40 definitions of music therapy and provides a new definition.

Bruscia discusses each component of this new definition and by doing so suggests boundaries for what music therapy IS versus what it IS NOT.

5. Musicophilia: Tales of Music and The Brain – Oliver Sacks

This book is slightly different to the others. It examines the place music occupies in the brain, and how music affects the human condition.

Sacks explores cases of what he terms “musical malalignment”.

He explains why music is irresistible and can be both healing and unforgettable.

Bunt, L., & Pavlicevic, M. (2001). Music and emotion: Perspectives from music therapy. In P.N. Justin & J.A. Sloboda (Eds), series in affective science. Music and emotion: Theory and Research (pp. 181 – 201). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press

Stultz, D. L., Lineweaver, T. T., Brimmer, T., Cairns, A.C., Halcomb, D. J., Juett, J. et al. (2018). “Music first”: An alternative or adjunct to psychotropic medications for the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. GeroPsych: The Journal of Gerontopsychology & Geriatric Psychiatry, 31, 17 – 30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1024/1662-9647/a000180

Landis-Shack, N., Heinz, A. J., & Bonn-Miller, M. O. (2017). Music therapy for posttraumatic stress in adults: A theoretical review. Psychomusicology: Music, Mind, and Brain, 27, 334 – 342. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pmu0000192

Bell, T. P., McIntyre, K. A., & Hadley, R. (2016). Listening to classical music results in a positive correlation between spatial reasoning and mindfulness. Psychomusicology: Music, Mind, and Brain, 26, 226 – 235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pmu0000139

Barrett, F. J., Grimm, K. J., Robins, R. W., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., & Janata, P. (2010). Music-evoked nostalgia: Affect, memory, and personality. Emotion, 10, 390-403. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0019006

Ladviig, O., & Schellenberg, E. G. (2012). Liking unfamiliar music: Effects of felt emotion and individual differences. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity and The Arts, 6, 146 – 154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0024671

17 Science-Based Ways To Apply Positive CBT

These 17 Positive CBT & Cognitive Therapy Exercises [PDF] include our top-rated, ready-made templates for helping others develop more helpful thoughts and behaviors in response to challenges, while broadening the scope of traditional CBT.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Some of these heart-warming videos are perfect to illustrate the benefits of Music Therapy.

What is Music Therapy?

This video features a board-certified musical therapist, Ryan Judd. He answers the questions “What is music therapy?” and “how do I find a music therapist?”

Music Therapy: Healing Music Sound Therapy for Relax, Chakra Balancing, and Well-being.

From the Meditation Relax Club .

Suitable for use in relaxation exercises or meditation, this video features peaceful, calming music set against a tranquil video.

My Job: Music Therapist

Trish, a music therapist, explains her role. She also explains how music therapy can help clients to meet both medical and emotional needs.

What a Music Therapy Session Looks Like

By sharing a description of working with a child with autism spectrum disorder, this board-certified music therapist explains what happens in a music therapy session. This video gives a brief snapshot of what music therapy looks like.

Music Therapy

This video shows the music therapy department at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. It explains how board-certified music therapists assist patients to cope with procedures, pain and anxiety.

The power of music has been evident since the earliest days of humankind. However, after the world wars of the 20th century, music therapy heralded the beginning of a powerful new profession.

Since then, various types and methods of music therapy have been developed, and music therapy has been practiced in a variety of settings with far-reaching benefits.

Hopefully, this article has provided you with a helpful overview of the music therapy profession. What are your experiences with music therapy? What do you think it offers clients in conjunction with traditional therapies? Or, have you had experience of music therapy as a stand-alone intervention? Please feel free to share your thoughts and ideas.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. For more information, don’t forget to download our three Positive CBT Exercises for free .

- Blodgett, Ashley (2015). These 12 facts about music, and how they affect your brain, will astound you! Retrieved from https://www.unbelievable-facts.com/2015/04/facts-about-music.html/2

- Blood, A., & Zatorre, R. J. (2001). Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion. National Academy of Sciences, 98 , 11818 – 11823.

- Bradt, J., & Dileo, C. (2010). Music therapy for end-of-life care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1, Art. No: CD007169.

- Children’s Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service (n.d.). Music Therapy. Retrieved from https://www.childrens.health.qld.gov.au/fact-sheet-music-therapy/

- Everyday Harmony (n.d.). What is Music Therapy? Retrieved from www.everydayharmony.org/what-is-music-therapy/

- Fandom (n.d.). Music therapy activities wiki. Retrieved from https://musictherapyactivities.fandom.com/wiki/Music_Therapy_Activities_Wiki

- Forsblom, A., Lantinen, S., Särkämö, T., & Tervaniemi, M. (2009). Therapeutic role of music listening in stroke rehabilitation. The Neurosciences and Music III-Disorders & Plasticity: Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 1169 , 426 – 430.

- Gerdner, L. A., & Swanson, E. A. (1993). Effects of individualized music on confused and agitated elderly patients. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 7 , 284 – 291.

- Geretsegger, M., Elefant, C., Mössler, K. A., & Gold, C. (2014). Music therapy for people with autism spectrum disorder. Cochrane Review of Systematic Reviews, 6, Art. No: CD004381.

- Gold, C., Voracek, M., & Wigram, T. (2004). Effects of music therapy for children and adolescents with psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45 , 1054 – 1063.

- Greenberg, D. M. (2017). The World’s First Music Therapist. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/au/blog/the-power-music/201704/the-world-s-first-music-therapist

- Guetin, S., Portet, F., Picot, M. C., Pommie, C., Messgoudi, M., Djabelkir, L. et al. (2009). Effect of music therapy on anxiety and depression in patients with Alzheimer’s type dementia: Randomised, controlled study. Dementia & Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 28 , 36 – 46.

- Hillecke, T., Nickel, A., & Volker Bolay, H. (2005). Scientific perspectives on music therapy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1060 , 1 – 12.

- Jacobson, V., & Artman, J. (2013). Music therapy in a school setting. Retrieved from https://williams-syndrome.org/sites/williams-syndrome.org/files/MusicTherapyTearSheet2013.pdf

- Klassen, J. A., Liang, Y., Tjosvold, L., Klassen, T. P., & Hartling, L. (2008). Music for pain and anxiety in children undergoing medical procedures: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 8 , 117 – 128.

- Koelsch, S. (2009). A Neuroscientific perspective on music therapy. Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 1169 , 374 – 384.

- Levy, Jillian (2017). Music therapy: Benefits and uses for anxiety, depression and more. Retrieved from https://draxe.com/music-therapy-benefits

- Maratos, A., Gold, C., Wang, X., & Crawford, M. (2008). Music therapy for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 1, Art. No: CD004517.

- Muzique (n.d.). Top 3 instruments to use in a music therapy session. Retrieved from https://www.muzique.org/muziqueblog/top-3-instruments-to-use-in-a-music-therapy-session

- Nordoff Robbins (n.d.). What is music therapy? Retrieved from https://www.nordoff-robbins.org.uk/what-is-music-therapy

- Rambach, Rachel (2011). 12 songs every music therapist should know. Retrieved from https://listenlearnmusic.com/2011/03/12-songs-every-music-therapist-should-know.html

- Rambach, Rachel (2016). My top 10 music therapy instruments. Retrieved from https://listenlearnmusic.com/2016/02/my-top-10-music-therapy-instruments.html

- Scott, Elizabeth (2018). Music relaxation: A healthy stress management tool. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/music-as-a-health-and-relaxation-aid-3145191

- Seibert, Erin (n.d.). Mental health session ideas. Retrieved from https://musictherapytime.com/2015/12/24/mental-health-session-ideas/

- Sena, Kimberley (2012). Guest Post: Essential iPad apps for music therapists. Retrieved from www.musictherapymaven.com/guest-post-essential-ipad-apps-for-music-therapists/

- Smith, Yolanda (2018). Types of Music Therapy. Retrieved from https://www.news-medical.net/health/Types-of-Music-Therapy.aspx

- Soundscape Music Therapy (n.d.). Music Therapy Methods. Retrieved from https://soundscapemusictherapy.com/music-therapy-methods/

- The American Music Therapy Association (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.musictherapy.org/

- Therapedia (n.d.). Music Therapy. Retrieved from https://www.theravive/therapedia/music-therapy

- Wigram, T., Pedersen, I. N., & Bonde, L. O. (2002). A Comprehensive Guide to Music Therapy: Theory, Clinical Practice, Research and Training . London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

- Wong, H. L., C., Lopez-Nahas, V., & Molassiotis, A. (2001). Effects of music therapy on anxiety in ventilator-dependent patients. Heart and Lung: The Journal of Acute and Critical Care, 30 , 376 – 387.

- Your Free Career Test (n.d.). What does a music therapist do? Retrieved from https://www.yourfreecareertest.com/what-does-a-music-therapist-do/

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

That was a great article .Thank you

So informative

Wonderful Post, simple, clear, direct, Very Informative…..Great Job Heather!!!…BRAVO,….Am musician, composer & arranger and I’m actually working on a Research Proposal for an MPhil by Research will be exploring in the field of Music Therapy. All the Best to You Heather

Thanks for sharing, great article.

This was very helpful. It helped in my understanding of the connection between music and wellness.

This article is so good. I got all the information I need. Thanks for sharing.

That’s really nice post. I appreciate, Thanks for sharing.

Thank you Heather. I am researching music and the therapeutic effects it has on those of us with brain injuries, to put together a small book on How To Recover From. A Brain Injury. Interestingly enough, my sister played music for me, while I was in a coma. I then went through a post injury (10 years later) phase of recovery where I loved live music. I would like to contribute this idea, although I am sure you are aware of it yourself, and that is the ability of music to bring you into the moment so fully, that all the deficits and disabilities fall away. I found my whole being enveloped in the music being performed, and forgot all about who I was. It was fabulously wonderful to feel so lifted up from a world of always working on improving yourself.

Great book Heather with so much information, I am researching for a uni essay and this has been most helpful,

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Holistic Therapy: Healing Mind, Body, and Spirit

The term “holistic” in health care can be dated back to Hippocrates over 2,500 years ago (Relman, 1979). Hippocrates highlighted the importance of viewing individuals [...]

Trauma-Informed Therapy Explained (& 9 Techniques)

Trauma varies significantly in its effect on individuals. While some people may quickly recover from an adverse event, others might find their coping abilities profoundly [...]

Recreational Therapy Explained: 6 Degrees & Programs

Let’s face it, on a scale of hot or not, attending therapy doesn’t make any client jump with excitement. But what if that can be [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (50)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (33)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Positive CBT Exercises (PDF)

- Home The Latest Posts

A Quick Reference Guide to Lyric Analysis

[display_podcast]

AMTA-Pro Podcast April, 2019

Karen Miller, MM, MT-BC

1. Introduction

2. Rationale for developing the quick reference guide as a tool for music therapists

3. Common psychosocial music therapy techniques, including lyric analysis

4. Best practice components: theory, research, practice

5. Process for developing the quick reference guide as a tool for music therapists

6. 3-stage process of lyric analysis: explore, relate, apply

7. An overview of the Quick Reference Guide (see below)

Quick Reference Guide to Solution-focused Lyric Analysis in Psychosocial Music Therapy Treatment

Recommendations and Procedural Menu

Introduction

The Quick Reference Guide to Solution-Focused Lyric Analysis in Psychosocial Music Therapy Treatment is a procedural guideline for the use of lyric analysis as a tool within psychosocial music therapy treatment. The tool is intended for use by professional music therapists as well as music therapy students and educators. While lyric analysis is widely accepted as a method used to assist music therapy clients in identifying personal issues, exploring emotions, and relating to the experiences of others, the present tool is intended to pool information gained from research and clinical experience that will inform best practice by providing an easily accessible system for clinical decision-making. The tool is also intended to assist therapists and their clients in moving from the identification and expression of therapeutic material to positive action, thereby facilitating practical steps toward problem solving.

The Quick Reference Guide was built within the theoretical framework of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). Resulting recommendations are consistent with CBT principles as well as informed by both research and practice, intentionally providing a solid foundation of theory, research, and practice upon which to base clinical decisions.

The tool may be useful when clinical goals are centered on the amelioration of various forms of distress. It is intended for work with clients exhibiting psychosocial needs who demonstrate verbal skills and reality-based cognitive processes sufficient to complete the steps involved. Emotional, social, cognitive, and communication ability should be considered carefully in the decision-making process along with other factors outlined in the guide.

Guidelines presented were gathered from existing peer-reviewed publications as well as from extensive clinical practice. Those recommendations found in published research are referenced throughout the document. The Quick Reference Guide to Solution-Focused Lyric Analysis in Psychosocial Music Therapy Treatment was developed by Karen Miller, MM, MT-BC, while Professor of Music Therapy at Sam Houston State University, with research assistance from the following graduate students:

Mary Kate Becnel, MM, MT-BC Alexandra Brickley, MM, MT-BC Joyce Chun, MM, MT-BC Marcus Hughes, MM, MT-BC Karina Melara, MM, MT-BC Chen Peng, MM, Zachary Pollard, MM, MT-BC Nicole Rogers Sarah Rossi, MM, MT-BC Hannah Sopher, MT-BC Annie Vandervoort, MM, MT-BC Michael Way, MM, MT-BC

NOTE: ( ) denotes research reference throughout the document.

Song Choice Recommendations

Consider client’s choice vs. therapist’s choice of song and the benefits of each (2,6,8,9,10,11,21,22)

Be aware of client’s potential associations (4,6,8,11,15)

Identify positive and negative messages in songs before choosing – consider the usefulness of each (6,8,15)

Choose music and lyrics that are relatable to clients in their current state (2,4,5,6,8,15,18,19,20)

Pay attention to music style and characteristics; impact of the music as well as lyrics (2,4,5,6)

Consider the impact of repetition in lyrics (6,14)

Realize the power of both music and poetry (lyrics) to elicit emotion (2,4,5,15)

Choose songs that address specific topics and/or cognitive distortions related to the client’s goals (2,4,5,6,8,9,10,11,15,20,21,22,23)

Consult team members on appropriate topics (3)

Song Presentation Recommenadations

Use the Three Stage Procedural Menu as a guide in preparation, being mindful that it may be necessary or beneficial to skip Stage 1 or move in and out of stages in a different order.

Allow ample time, typically 30 minutes or more, for a complete process leading to specific problem-solving (20,21,22,23)

Consider the benefits of live vs. recorded music (7,8,9,10,11,18,19,22,23)

Ensure high quality music and sound to maximize attention and impact (19)

Stress that there are no right or wrong answers when interpreting songs (4,19)

Adapt for varying levels of functioning, including verbal, sensory, and cognitive abilities and medication effects Give individual copies of lyrics to clients before beginning (4,6,8,9,10,11,18,19,20,21,22,23)

Use large, bold font and easy reading format and consider numbering lines (4,19)

Instruct clients to mark lyrics that particularly stand out to them or give other assignment to actively engage clients with the lyrics (10,19)

Have clients re-read lyrics following song presentation (8)

Remain empathetic and use active listening skills to determine direction of discussion (3,4,6)

In a group setting, hear from everyone, and prompt clients to relate to and support one another (4)

Consider use of other modalities (illustration, art, movement, dance) to process the song prior to verbal processing (2)

Unless otherwise indicated, re-play song after the analysis (8)

As appropriate, encourage clients to share song with family, caregivers (11)

Assign specific homework related to discussion – consider use of worksheets as visual cues and structure for homework (1,8,19,22)

Always work within the boundaries of your training and ability; collaborate with team members, and refer clients to other therapists and health professionals when needed; maintain client’s emotional and physical safety as your top priority (4)

Three Stage Procedural Menu for Lyric Analysis Following Song Presentation

General Probes for Any Stage

Tell me more about that.

How did that make you feel? (8,9,11)

What does that remind you of? (8,9,11)

You seem (fill in emotion).

Stage 1: Explore (focus on the song)

~ Create probes directly from lyric content (e.g., Let’s talk about lines ________, What does the singer mean when he says ______? ) (2,4,5,6,18,20)

~ Other sample probes: (1,4,5,6,8,10,11,15,22)

Talk to me about this song.

What images were going through mind as you listened?

Tell me about the lyrics you highlighted/underlined.

What was the singer/songwriter experiencing?

What is the overall mood or message of the song?

Which lyrics represent thoughts or ideas that are rational or healthy?

Which lyrics represent thoughts or ideas that are distorted, irrational, or unhealthy?

What specific cognitive distortions can you identify in the lyrics?

What does this person do when he or she experiences difficult feelings?

How does that work for him/her?

How can he/she cope?

What would you tell this person?

What is this person most afraid of/angry about/happy about, etc.? (Follow up with, What are YOU most afraid of/angry about/happy about, etc.? then continue at Stage 2.)

Who can this person depend upon, and for what? (Follow up with, Who can you depend upon, and for what? then continue at Stage 2.)

Stage 2: Relate (focus on the client, including the client’s identification with the song, connection to the songwriter, client’s own thoughts, feelings, and behaviors)

~ Create probes directly from lyric content (e.g., How do you relate to the line ______? ) (2,4,5,20,21,22)

~ Other sample probes: (1,2,4,5,6,8,9,10,11,21,23)

In what ways is your life like this person’s life?

What would you like to be different?

How does the song connect with what you are going through?

How do you relate to that?

Which of those thoughts or feelings have you experienced? When?

Which lyrics stand out most to you?

What makes them stand out?

What emotions or personal experiences/memories are triggered by those lyrics?

When have you felt that way?

What was, or is, going on in your life that causes you to relate?

What was going through your mind when you heard this?

What was going through your mind when you felt that way?

What makes you feel that way now?

What needs to change?

Describe what a better future would look like.

What is going through your mind now?

What is the quick, passing thought that triggers/triggered that emotion?

On a scale of 1-100, how much did you believe that thought?

How much do you believe it now?

What evidence can we find for that thought being true?

What evidence can we find for that thought being false?

If that thought is likely false, what true statement can we make to replace it?

Stage 3: Apply (focus on coping and follow through)

~ Sample probes: (1,4,6,8,9,11,20,23)

When you have felt that way, how did you cope?

What coping strategies have you tried?

How did they work? What happened? And then what? And then what? And then what?

What are your options?

What will be the consequences of that option? And then what?

(repeat for other options)

What would you tell a close friend or family member in a similar situation?

Next time you feel that way, what will you tell yourself?

What seems to be the best direction or choice?

What is the first step?

What will you do today to get started?

May I follow up with you to see how it went? (Assign specific homework related to discussion.)

References

1. Beck, Judith S. Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and beyond . New York: Guilford, 2011. Print.

2. Bednarz, L. F., & Nikkel, B. (1992). The Role of Music Therapy in the Treatment of Young Adults Diagnosed with Mental Illness and Substance Abuse. Music Therapy Perspectives, 10 (1), 21-26. doi:10.1093/mtp/10.1.21.

3. Boenheim, C. (1966). Music and Group Psychotherapy. Journal of Music Therapy , 3 (2), 49-52. doi:10.1093/jmt/3.2.49.

4. Dvorak, A. L. (2017). A Conceptual Framework for Group Processing of Lyric Analysis Interventions in Music Therapy Mental Health Practice. Music Therapy Perspectives , 35 (2), 190-198.

5. Edgar, K. (1979). A case of poetry therapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 16 (1), 104-106. doi:10.1037/h0085863.

6. Heimlich, E. P., & Mark, A. J. (1990). Metaphoric Lyrics as a Bridge to the Adolescentâ € TMs World. Paraverbal Communication with Children , 159-173. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-0643-6_10.

7. Hilliard, R. E. (2006). The effect of music therapy sessions on compassion fatigue and team building of professional hospice caregivers. The Arts in Psychotherapy , 33 (5), 395-401. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2006.06.002.

8. Ho, M. K. (1984). The Use of Popular Music in Family Therapy. Social Work, 29 (1), 65-67. Retrieved January 21, 2017, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/23714274?ref=search- gateway:1ef22f67741f6661fe52abdffd94003b.

9. James, M. R. (1988). Music Therapy Values Clarification: A Positive Influence on Perceived Locus of Control. Journal of Music Therapy , 25 (4), 206-215. doi:10.1093/jmt/25.4.206.

10. Jones, J. D. (2005). A Comparison of Songwriting and Lyric Analysis Techniques to Evoke Emotional Change in a Single Session with People Who are Chemically Dependent. Journal of Music Therapy , 42 (2), 94-110. doi:10.1093/jmt/42.2.94.

11. Lelieuvre, R. B. (1998). “Goodnight Saigon”: Music, fiction, poetry, and film in readjustment group counseling. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice , 29 (1), 74-78. doi:10.1037//0735-7028.29.1.74.

12. Maultsby, M. C. (1977). Combining Music Therapy and Rational Behavior Therapy. Journal of Music Therapy, 14 (2), 89-97. doi:10.1093/jmt/14.2.89.

13. Montello, L., & Coons, E. E. (1998). Effects of Active Versus Passive Group Music Therapy on Preadolescents with Emotional, Learning, and Behavioral Disorders. Journal of Music Therapy, 35 (1), 49-67. doi:10.1093/jmt/35.1.49.

14. Nunes, J. C., Ordanini, A., & Valsesia, F. (2015). The power of repetition: Repetitive lyrics in a song increase processing fluency and drive market success. Journal of Consumer Psychology , 25 (2), 187-199. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2014.12.004.

15. Sargent, L. (1979). Poetry in Therapy. Social Work , 24 (2), 157-159. Retrieved January 21, 2017, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/23713665?ref=search-gateway:912083b6ff7392e3266b89282b21ef4f

16. Silverman, M. J., & Leonard, J. (2012). Effects of active music therapy interventions on attendance in people with severe mental illnesses: Two pilot studies. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 39 (5), 390-396. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2012.06.005

17. Silverman, M. J. (2007). Evaluating Current Trends in Psychiatric Music Therapy: A Descriptive Analysis. Journal of Music Therapy, 44 (4), 388-414. doi:10.1093/jmt/44.4.388

18. Silverman, M. J. (2009). The Effect of Lyric Analysis on Treatment Eagerness and Working Alliance in Consumers Who Are in Detoxification: A Randomized Clinical Effectiveness Study. Music Therapy Perspectives, 27 (2), 115-121. doi:10.1093/mtp/27.2.115

19. Silverman, M. J. (2009). The Use of Lyric Analysis Interventions in Contemporary Psychiatric Music Therapy: Descriptive Results of Songs and Objectives for Clinical Practice. Music Therapy Perspectives, 27 (1), 55-61. doi:10.1093/mtp/27.1.55

20. Silverman, M. J. (2010). The effect of a lyric analysis intervention on withdrawal symptoms and locus of control in patients on a detoxification unit: A randomized effectiveness study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 37 (3), 197-201. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2010.04.001

21. Silverman, M. J. (2015). Effects of educational music therapy on illness management knowledge and mood state in acute psychiatric inpatients: A randomized three group effectiveness study. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 25 (1), 57-75. doi:10.1080/08098131.2015.1008559

22. Silverman, M. J. (2015). Effects of Lyric Analysis Interventions on Treatment Motivation in Patients on a Detoxification Unit: A Randomized Effectiveness Study. Journal of Music Therapy, 52 (1), 117-134. doi:10.1093/jmt/thu057

23. Silverman, M. J. (2016). Effects of a Single Lyric Analysis Intervention on Withdrawal and Craving With Inpatients on a Detoxification Unit: A Cluster-Randomized Effectiveness Study. Substance Use & Misuse, 51 (2), 241-249. doi:10.3109/10826084.2015.1092990

About the Podcast Speaker

Ms. Miller has presented clinical and research material regionally, nationally, and internationally. Her research is published in the Journal of Music Therapy and Music Therapy Perspectives . She is a Past-President of the American Music Therapy Association’s Southwestern Region (SWAMTA) and has served the American Music Therapy Association (AMTA) as a long-standing Assembly Delegate and as co-chair of the organization’s Academic Program Approval Committee.

As Director of Music Therapy at SHSU, Professor Miller contributed to both qualitative and quantitative growth of music therapy programs through endeavors such as overseeing the development of graduate programs in music therapy, developing the on-campus SHSU Music Therapy Clinic, and establishing a wide variety of practicum and internship programs. Professor Miller gained prior university teaching experience at both the University of the Pacific in Stockton, California, and The Florida State University in Tallahassee, Florida.

Ms. Miller is also a singer/songwriter and has produced two CD’s of original songs.

Her music education and music therapy studies were completed at Oklahoma Baptist University (B.M.E.) and The Florida State University (M.M.).

Comments are closed.

Get our RSS Feed Use username: music & password: coda

Check it out

AMTA-Pro is filled to the brim with a wealth of podcasts featuring your colleagues sharing reflections, strategies, insider tips, and details about every aspect of music therapy. Don't miss even one of several dozen AMTA-Pro podcasts on a wide variety of topics, including: + Music therapy programs, clinical applications, and research in a broad range of areas such as Alzheimer's disease, eating disorders, stroke rehab, inpatient mental health, early childhood behavior issues, medical settings, wellness, NICU, wound care, hospice, and more. + Job Solutions, reimbursement, networking, and thriving in any economy. + Interviews with music therapy professionals, students, and interns, as well as special guests. + Podcasts capturing special AMTA events, conference speakers, and memorial tributes.

Did you know that you can now subscribe to AMTA-pro in a feed reader or with iTunes?

Click the orange RSS Feed button above, enter the username: music & password: coda and then choose the method of subscription you would like.

You can also subscribe by email:

Delivered by FeedBurner

© Copyright 2018 by the American Music Therapy Association, Inc.. All Rights Reserved. Content herein is for personal use only. No part may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording by any information storage or retrieval system, without express written permission from the American Music Therapy Association. Neither the American Music Therapy Association nor its Board of Directors is responsible for the conclusions reached or the opinions expressed in any of the AMTA.Pro symposiums.

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.org

Getting Details...

Degree Programs: There's Still Time to Apply. Apply Now!

1-866-berklee, int'l +1-617-747-2146, [email protected], searching..., or check out these faqs:.

- CHANGE CERTIFICATE: When a student wants to change their lower-level certificate to a higher-level certificate (or vice versa) prior to the completion of the program. There are no additional fees for this option other than the cost of additional courses, and you will only earn one certificate upon completion.

- STARTING A NEW CERTIFICATE: When a student wants to earn more than one certificate by having the courses from their lower-level certificate waived into a higher-level certificate. In this case, an additional $175 registration fee is required.

Financial Aid

- Attained at least a 2.70 cumulative GPA in concentrate courses

- Have a minimum cumulative GPA of 2.00

- Fulfilled all program requirements AND completed a minimum of 120 credits for a single major or 165 for a dual major

- Completed a minimum of 60 institutional credits for a single major or 105 institutional credits for a dual major

- Fulfilled all financial obligations to the college

Transfer Credits

Online undergraduate-level course, music therapy techniques for wellness.

Authored by Suzanne Hanser

Course Code: OMUTH-105

Next semester starts June 24 Enroll by 5 PM ET. Limited seats available.--> Enroll by 5 PM ET. Limited seats available.-->

3-credit tuition, non-credit tuition.

Have you found that music can immediately change your mood? Have you seen how music brings back special memories and pictures in your mind's eye? Have you noticed that a song can express exactly how you feel? This course explores these questions and more. You’ll learn how music affects your mind, body, and soul, and you’ll practice evidence-based musical activities and exercises that can enhance your general well-being and wellness.

Need guidance?

Call , Text , or Email us

Lesson 1: An Introduction to Integrative Health

- Music for Sickness and Health

- The Impact of Music on Our Lives

- Integrative Medicine/Health and Music Therapy

- Holistic Healing

- Healing Music

- Assignment 1: Music Healing

Lesson 2: Tuning In: Your Journey

- Physical Preparation

- Emotional Preparation

- Mental Preparation

- Existential Preparation

- Spiritual Preparation

- Musical Preparation

- Assignment 2: Tuning In

Lesson 3: Music for Comfort

- Music for Comfort: The Lullaby

- Comforting the Body with Music

- The Power of Breath

- What is Pranayama?

- Comforting the Mind Through Breath

- Assignment 3: Your Lullaby

Lesson 4: Music for Awakening

- Awakening through Music

- Awakening through Chant and Mantra

- Creating and Integrating Mantra (Jingles) into Your Wellness Practice

- Awakening through Imagery

- Awakening through Power Songs

- Assignment 4: Your Music for Awakening

Lesson 5: Finding Your Voice

- The Science Behind Singing

- Singing How You Feel

- Circle Singing

- Songwriting

- Ways to Integrate Creating Music into Your Music Wellness Practice

- Assignment 5: Your Music Wellness Practice

Lesson 6: Listening for Wellness

- Deep Listening

- Listening with Imagery

- How the Brain Processes Music

- Iso-Principle Technique

- Assignment 6: Matching Your Mood

Lesson 7: Music for Peace

- What is the Meaning of Peace?

- What is Gratitude?

- Musical Rituals

- Assignment 7: Your Song of Peace and Ritual

Lesson 8: Assessing Stress and Pain

- Stress Assessment Log

- Pain Assessment Log

- Music Listening Log

- What Music Can Do for You

- Assignment 8: Stress, Pain, and Music Listening Logs

Lesson 9: How to Apply Music for Wellness Every Day

- When Do You Need Music?

- Music-Based Applications for Every Day

- Implementation of a New Day

- Assignment 9: Your Music Plan

Lesson 10: How to Apply Music for Wellness for Stress and Pain

- Music Listening Applications for Serious Stress and Pain

- Playing Instruments as a Coping Strategy

- Singing as a Coping Strategy

- Creative Musical Solutions for Stress and Pain

- Improvisation as a Coping Strategy

- Songwriting as a Coping Strategy

- Assignment 10: Stress and Pain Strategy

Lesson 11: Your Personal Music Wellness Plan

- Evaluating Your Initial Contributions to the Course

- Music for Comfort

- Music for Awakening

- Finding Your Musical Voice

- Listening for Wellness

- Music for Peace

- Assignment 11: Music Wellness Re-Evaluations

Lesson 12: Bringing Meaning to Your Learning

- Integration

- Your Values

- Your Relationships

- Assignment 12: Final Music Wellness Play

Requirements

Prerequisites and course-specific requirements .

Prerequisite Courses, Knowledge, and/or Skills This course does not have any prerequisites.

Textbook(s)

- Integrative Health Through Music Therapy: Accompanying the Journey from Illness to Wellness by Suzanne B. Hanser (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016)

- Manage Your Stress and Pain Through Music by Suzanne. B. Hanser & S. E. Mandel (Berklee Press 2010)

- Digital or paper journal. Digital options include Google Keep , Penzu , Notes for Mac , Notepad for Windows , Evernote , etc.

Student Deals After enrolling, be sure to check out our Student Deals page for various offers on software, hardware, and more. Please contact [email protected] with any questions.

General Course Requirements

Below are the minimum requirements to access the course environment and participate in Live Chats. Please make sure to also check the Prerequisites and Course-Specific Requirements section above, and ensure your computer meets or exceeds the minimum system requirements for all software needed for your course.

- macOS High Sierra 10.13 or later

- Windows 10 or later

- Latest version of Google Chrome

- Zoom meeting software

- Speakers or headphones

- External or internal microphone

- Broadband Internet connection

Instructors

Author & Instructor

Dr. Suzanne B. Hanser is founding chair of the Music Therapy Department at Berklee College of Music. She is President of the International Association for Music & Medicine and past president of both the World Federation of Music Therapy and the National Association for Music Therapy. Dr. Hanser is the author of research articles, as well as several books: The New Music Therapist's Handbook, Manage Your Stress and Pain, with co-author Dr. Susan Mandel, and Integrative Health through Music Therapy: Accompanying the Journey from Illness to Wellness. In 2006 she was named by the Boston Globe as one of eleven Bostonians Changing the World. In 2009 she was awarded the Sage Publications Prize for her article, “From Ancient to Integrative Medicine: Models for Music Therapy.” She received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Music Therapy Association in November 2011.

What's Next?

When taken for credit, Music Therapy Techniques for Wellness can be applied towards the completion of these related programs:

Related Certificate Programs

- General Music Studies Professional Certificate

- General Music Studies Advanced Professional Certificate

Related Degree Major

- (Pre-Degree) Undeclared Option

Related Music Career Role

Employers look for skills learned in this course, when hiring for the following music career role:

Music Therapist

Contact our Academic Advisors by phone at 1-866-BERKLEE (U.S.), 1-617-747-2146 (INT'L), or by email at [email protected] .

Enroll by May 13 and Save up to $300

Get instant access to free music resources, access free music resources, free sample lessons.

Take our online school for a test drive with our free sample course, featuring 12 lessons from our most popular courses.

Degree Handbooks

Download free course materials designed to provide you with marketable skills in music.

Online Course Catalog

Browse more than 200 unique 12-week courses in a wide variety of musical interest areas.

News and Exclusive Content

Receive the latest in music trends, video tutorials, podcasts, and more.

Already have an account? Log in to get access.

Berklee is accredited by the New England Commission of Higher Education (NECHE).

Berklee Online is a University Professional and Continuing Education Association (UPCEA) award-winner eighteen years in a row (2005-2023).

We use cookies to improve your experience on our sites. By use of our site, you agree to our cookie policy .

Proof of Bachelor's Degree to Enroll

Proof of a bachelor's degree is required to enroll in any non-degree, graduate-level certificate or course .

Ready to submit an unofficial copy of your transcript?

International Students

See the Enrolling in a Graduate Certificate or Individual Course page for more information.

- My Publications

Must-have Musical Skills for Student Music Therapists to Develop

by Kimberly on October 22, 2020 · 0 comments

My primary responsibility in my current academic position is to train future music therapists. The vast majority of my more traditional teaching load is geared towards the preprofessional music therapist—introduction to music therapy, two music therapy methods courses, and pre-practicum, a course where students learn foundational elements of how to “do” music therapy (assessment, goals and objectives, etc.). As Clinical Training Director I oversee student fieldwork experiences, from placements to assignments to clinical supervision.

Suffice it to say I’ve spent a fair amount of time and energy over the past 7 years thinking about what’s needed to be an effective music therapist (more, really, since I started teaching and supervising students about 12 years ago now).

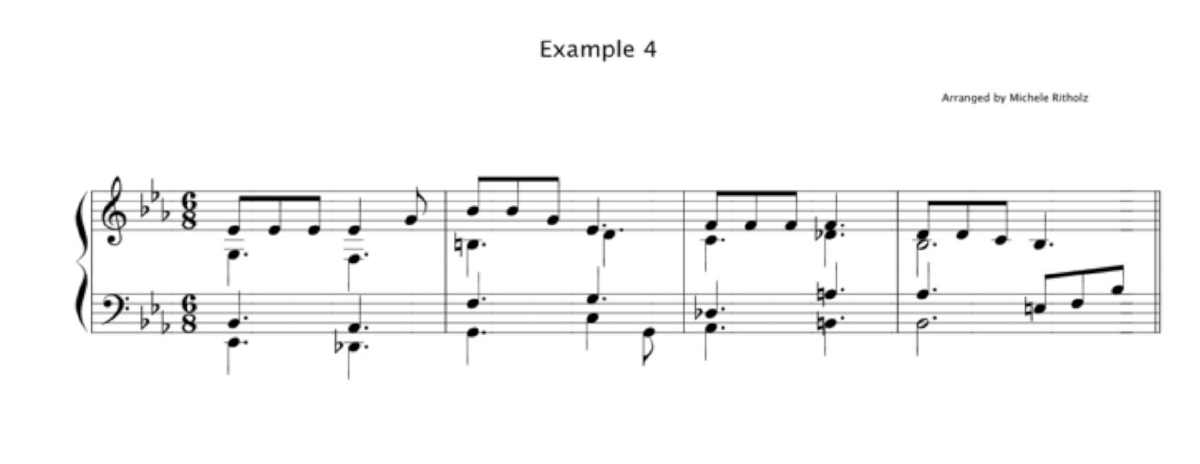

This post focuses on the musical skills I aim to nurture and help develop in my students. More specifically, I’m focusing here on the live musical skills needed to effectively facilitate therapeutic music experiences, whether they be recreative, receptive, improvisational, or compositional (with a nod to Bruscia (2014) for his description of music-based methods). There are other aspects of music therapy treatment that go beyond live music of course (recorded music, anyone?), but let’s stick with this idea of live musical skills for now.

On the AMTA end, the Standards for Education and Clinical Training (2018) state that training programs should help students develop “competencies in functional keyboard, guitar, voice, percussion, and improvisation.” The AMTA Professional Competencies (2013) document is a bit more detailed, listing specific (and arguably basic) music, conducting, and compositional skills a professional music therapist should be able to complete, with a focus on guitar, piano, voice, and percussion. The most detailed is the CBMT Board Certification Domains (2020) , which under section III.A.5 lists 34 distinct mostly-musical skills a board certified music therapist should be able to demonstrate to achieve therapeutic goals.

For me, when I take a step back and consider what I see as integral to contemporary music therapy practice, the musical skills I aim to help my students develop are intended to promote authenticity, adaptability, holistic musicianship, and/or healthy practice. What do I mean by these?

“ Authenticity ” means you have the technical and aural skills to be able to learn and play music in a way that’s stylistically…well, authentic. Given the rich diversity of musical traditions, there is no way to “teach them all” within the time constraints of a college degree. Rather, I aim to help my students develop skills they can use to listen to music in order to learn and play it for clients in a way that’s authentic to (or reflective of) the intended style.

“ Adaptability ” means you have the technical and aural skills to be able to change the music. Sometimes this happens during the planning stage. I often tell my students that part of the “fun” of being a music therapist is we have permission to take a song and change it to meet an intended therapeutic purpose. Other times this adaptability occurs on-the-spot in response to what you observe in the client. Maybe we need to musically redirect a client or aim to shift them to a different state of physiologic arousal. In either case we need to have certain musical skills in place in order to change the music we provide to meet client needs.

“ Holistic musicianship ” means you have skills beyond singing and playing music, you must be able to compose and improvise music as well. This is often closely tied to music theory—we need to have an understanding of the structure of music (including form, harmony, melody, texture, and more) in order to create music…and by extension help clients create music.

“ Healthy practice ” means you perform music in a way that protects your vocal and musculoskeletal health. This means working to maintain healthy back, shoulder, and wrist alignment, keeping space for breathing and breath support, and singing with resonance. It’s a major shift to go from facilitating one session a week to multiple sessions a day, so I aim to help my students develop healthy habits and abilities before sending them off to internship.

Within these areas there are of course certain technical skills that need to be rehearsed and solidified before any of the authenticity, adaptability, and holistic musicianship can come to fruition. These include things like:

- Singing on pitch with appropriate breath support and resonance, both a capella and with accompaniment.

- Smoothly playing and transitioning between different chords/chord shapes on various harmonic accompaniment instruments. (Although in the US the transitions between chords will most likely start with traditional Western harmonic progressions, we need not be limited to this.)

- Applying different accompaniment patterns. On stringed accompaniment instruments (typically guitar and ukulele) this includes strumming and fingerpicking patterns, as well as percussive effects such as stops. On keyboard instruments this includes at minimum playing the bass note in the left hand (or variations such as bass and fifth, bass and octave, or bass, fifth, and octave) with chords in the right hand, as well as effective use of the sustaining pedal.

- Leading a musical experience, including the ability to prep and cue an entrance in time, as well as incorporate a musical introduction that establishes tempo and tonality.

- Transposing between keys, which on the guitar includes accurate use of the capo.

- Understanding and executing appropriate playing techniques, which can be for the purposes of resonance as well as proper (i.e., healthy) technique. This can apply to vocal placement, how you play different percussion and drum instruments, and knowing, for example, where to strum on a ukulele (which is different than on a guitar).

This is not intended as an all-inclusive list—there are myriad other musical skills that can encompass a music therapist’s practice. But when I reflect on what to me are the foundational skills to nurture (and why), this is where I land. I share my thoughts here with the understanding that others have thoughts on this topic too. In that spirit, I welcome your thoughts, comments, questions, and suggestions below.

American Music Therapy Association. (2013). Professional competencies. https://www.musictherapy.org/about/competencies/

American Music Therapy Association. (2018). Standards for education and clinical training . https://www.musictherapy.org/members/edctstan/

Bruscia, K. (2014). Defining music therapy (3rd ed.). Barcelona Publishers.

Certification Board for Music Therapists. (2020). Music therapy board certification: Board certification domains—2020. https://www.cbmt.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CBMT_Board_Certification_Domains_2020.pdf

{ 0 comments… add one now }

You must log in to post a comment.

Previous post: What’s in a name? Reflections on describing the work we do

Next post: Things to Look for in a Referral

Welcome! My name is Kimberly Sena Moore. I’m a board certified music therapist, associate professor in the Bower School of Music & the Arts at Florida Gulf Coast University , and advisor on legislative and policy issues for Certification Board for Music Therapists . Feel free to explore this site for information on music therapy and my journey as a working mama in academia. Thanks for visiting!

FOLLOW MY RESEARCH

How to Start a Therapy Practice

Closing Shop 101

MAVEN SPONSORS

- Academic Journeys

- Guest Posts

- Kimberly Personal

- Mommy Mondays

- Music Therapy

- Private Practice

- Suggested Resources

FIND ME HERE

Get smart with the Thesis WordPress Theme from DIYthemes.

WordPress Admin

The Harmony Handbook Vol. 1

Resources for music therapists working with adolescents and adults in mental health treatment, this 50-page ebook will help you by: .

- Decreasing session planning time. All interventions come with instructions and worksheets.

- Allowing you to take a break from constantly having to come up with your own session plans.

- Supplying you with a go-to resource when wondering, “what should I do in my session today?”

- Giving you a fresh starting place to implement and generate new ideas.

- Expanding your abilities and skills as a music therapist.

- Providing music therapy resources, ideas, and interventions for your clientele.

This eBook is divided into 3 sections and includes:

- Music therapy worksheets may serve as assessment tools, self-reflection tools, session openers, or topics for discussion. These worksheets provide an opportunity for reflecting on music and creativity, and can be useful as a break from playing music, homework assignments, and for facilitating music based discussions and reflections.

- 10 Music therapy interventions are presented in universal themes, each with instructions, suggested music, and accompanying worksheets to facilitate a structured and goal-oriented session. The interventions used within these themes are meant to stimulate a deeper level of emotional connection with the theme and music, to later be processed within the group and/or with the therapist. These interventions were designed for groups but may be also used with individuals and adapted to suit various functioning levels and time frames.

- 5 Guided meditation scripts that are short and simple. They may be used to open or close sessions, and support the interventions.

Payments are made securely by credit card or PayPal Download of eBook as PDF file will be available immediately after payment

PREVIEW & REVIEWS

Working with adolescents and adults in acute mental health is very rewarding. The Harmony Handbook is a helpful sourcebook full of creative, insightful, and realistic interventions to improve and supplement current music therapy practice for this population. Ami leaves room for the music therapist to determine the best uses for each section of interventions, which allows the reader the chance to not just follow a recipe, but integrate the ideas into their own practice. The structure of this book permits easy understanding of how each intervention can unfold with mindful attention to important themes that can be addressed with this population. Ami also offers further suggestions to help develop the theme or intervention further. The Harmony Handbook is a valuable sourcebook, full of ideas that aim to inspire clients to connect with music and their treatment objectives.

My testimony to this work of art is one filled with deep gratitude and appreciation. Ami obviously has not only worked well with these individuals, but has done so in a way that authentically embodies the artistic expression of what we do as music therapists. Members of my substance abuse rehab groups have resonated with these ideas telling me things like, “I not only like these songs, but what you do with them; it applies directly to what I’m going through.” Her brilliant tapestry of weaving together specific interventions that can be molded to fit the varying needs of clients in mental health treatment has also helped in shaping my own work in this field.

About the Author

Ami Kunimura, MA, MT-BC is the founder of The Self-Care Institute and a writer, speaker, and music therapist.

Ami has been a board-certified music therapist since 2006, specializing in mental health, trauma, and addictions treatment. Ami also holds certifications in yoga education and first and second degree reiki, with training in mindfulness and meditation.