More From Forbes

Life isn't fair - deal with it.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

There seems to be a lot of talk these days about what is fair, and what is not. President Obama seems to believe life should be fair – that “everybody should have a fair shake.” Some of the 99% seem to believe life has treated them unfairly, and some of the 1% percent feel life hasn’t treated them fairly enough. My questions are these: What is fair? Is life fair? Should life be fair? I’ll frame the debate, and you decide…

We clearly have no choice about how we come into this world, we have little choice early in life, but as we grow older choices abound. I have long believed that while we have no control over the beginning of our life, the overwhelming majority of us have the ability to influence the outcomes we attain. Fair is a state of mind, and most often, an unhealthy state of mind.

In business, in politics, and in life, most of us are beneficiaries of the outcomes we have contributed to. Our station in life cannot, or at least should not, be blamed on our parents, our teachers, our pastors, our government, or our society - it’s largely based on the choices we make, and the attitudes we adopt.

People have overcome poverty, drug addiction, incarceration, abuse, divorce, mental illness, victimization, and virtually every challenge known to man. Life is full of examples of the uneducated, the mentally and physically challenged, people born into war-torn impoverished backgrounds, who could have complained about life being unfair, but who instead chose a different path – they chose to overcome the odds and to leave the world better than they found it. Regardless of the challenges they faced, they had the character to choose contribution over complaint.

I don’t dispute that challenges exist. I don’t even dispute that many have an uphill battle due to the severity of the challenges they face. What I vehemently dispute is attempting to regulate, adjudicate, or legislate fairness somehow solves the world’s problems. Mandates don’t create fairness, but people’s desire and determination can work around or overcome most life challenges.

It doesn’t matter whether you are born with a silver spoon, plastic spoon, or no spoon at all. It’s not the circumstances by which you come into this world, but what you make of them once you arrive that matter. One of my clients came to this country from Africa in his late teens, barely spoke the language, drove a cab while working his way through college, and is now the President of a large technology services firm. Stories such as this are all around us – they are not miracles, nor are they the rare exception. They do however demonstrate blindness to the mindset of the fairness doctrine.

From a leadership perspective, it’s a leader’s obligation to do the right thing, regardless of whether or not it’s perceived as the fair thing. When leaders attempt to navigate the slippery slope of fairness, they will find themselves arbiter of public opinion and hostage to the politically correct. Fair isn’t a standard to be imposed unless a leader is attempting to impose mediocrity. Fair blends to a norm, and in doing so, it limits, inhibits, stifles, and restricts, all under the guise of balance and equality. I believe fair only exists as a rationalization or justification. The following 11 points came from a commencement speech widely attributed to Bill Gates entitled Rules for Life. While many dispute the source , whether it was proffered by Bill Gates or not, I tend to agree with the hypothesis:

Rule 1: Life is not fair -- get used to it!

Rule 2: The world won't care about your self-esteem. The world will expect you to accomplish something BEFORE you feel good about yourself.

Rule 3: You will NOT make $60,000 a year right out of high school. You won't be a vice-president with a car phone until you earn both.

Rule 4: If you think your teacher is tough, wait till you get a boss.

Rule 5: Flipping burgers is not beneath your dignity. Your Grandparents had a different word for burger flipping -- they called it opportunity.

Rule 6: If you mess up, it's not your parents' fault, so don't whine about your mistakes, learn from them.

Rule 7: Before you were born, your parents weren't as boring as they are now. They got that way from paying your bills, cleaning your clothes and listening to you talk about how cool you thought you are. So before you save the rain forest from the parasites of your parent's generation, try delousing the closet in your own room.

Rule 8: Your school may have done away with winners and losers, but life HAS NOT. In some schools they have abolished failing grades and they'll give you as MANY TIMES as you want to get the right answer. This doesn't bear the slightest resemblance to ANYTHING in real life.

Rule 9: Life is not divided into semesters. You don't get summers off and very few employers are interested in helping you FIND YOURSELF. Do that on your own time.

Rule 10: Television is NOT real life. In real life people actually have to leave the coffee shop and go to jobs.

Rule 11: Be nice to nerds. Chances are you'll end up working for one.

Here’s the thing – we all face challenges, and life treats us all unfairly. We all make regrettable choices, and we all suffer from things thrust upon us do to little if any fault of our own. When I suffered a debilitating stroke at an early age, I certainly asked myself “why did this happen to me?” I could have felt sorry for myself and became bitter, I could have thrown in the towel and quit on my family and myself – I didn’t. It took two years of gut-wrenching effort, but what I thought was a great injustice at the time changed my life for the better. Today, you couldn’t tell I ever had a stroke. The greatest adversity life can throw at you simply affords you an opportunity to make changes, improve, and get better.

By the title of today’s column you have no doubt surmised I believe life is not fair, nor do I believe we should attempt to socially or financially engineer it to be such. Fair is not an objective term – it is a matter of perspective filtered by a subjective assessment. My subjective assessment is that fair is an entitlement concept manufactured to appease those who somehow feel slighted. Life isn’t fair - #occupyreality

Follow me on Twitter @mikemyatt

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Life’s not fair! So why do we assume it is?

Doctoral Student in Developmental Psychology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Disclosure statement

Larisa Hussak receives funding from the National Science Foundation.

View all partners

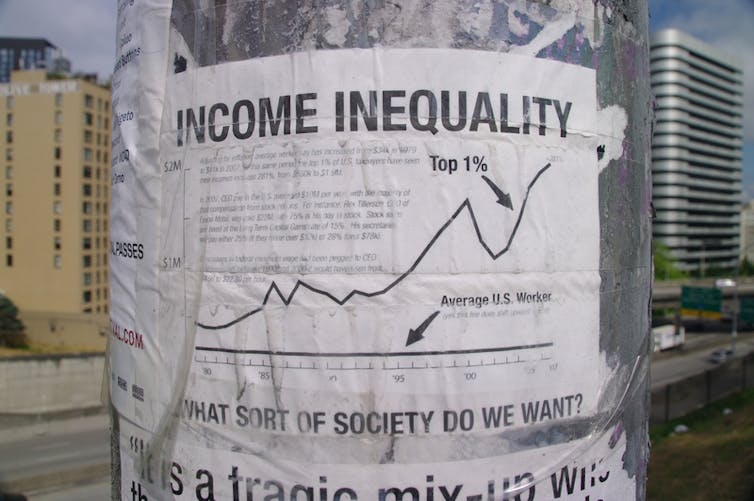

Income inequality in America has been growing rapidly, and is expected to increase . While the widening wealth gap is a hot topic in the media and on the campaign trail, there’s quite a disconnect between the perceptions of economists and those of the general public.

For instance, surveys show people tend to underestimate the income disparity between the top and bottom 20% of Americans, and overestimate the opportunity for poor individuals to climb the social ladder. Additionally, a majority of adults believe that corporations conduct business fairly despite evidence to the contrary and that the government should not act to reduce income inequality.

Even though inequality is increasing, Americans seem to believe that our social and economic systems work exactly as they should. This perspective has intrigued social scientists for decades. My colleague Andrei Cimpian and I have demonstrated in our recent research that these beliefs that our society is fair and just may take root in the first years of life, stemming from our fundamental desire to explain the world around us.

Believing in a legit reason for bad situations

When the going gets tough, it can be emotionally exhausting to think about all the obstacles in one’s path. This idea has been used by many researchers to explain why people – especially those who are disadvantaged – would support an unequal society. Consciously or not, people want to reduce the negative emotions they naturally feel when faced with unfairness and inequality.

To do this, people rationalize the way things are. Rather than confronting or trying to change what is unfair about their society, people prefer to fall back on the belief that there’s a valid reason for that inequity to exist.

This drive to relieve negative feelings by justifying “the system” seems to play an important role in people’s thinking about their societies all over the world . Therefore, it almost seems to be human nature to explain away the inequalities we encounter as simply the way things are supposed to be.

But are negative emotions necessary for people to justify the society around them? According to our findings , perhaps not.

Quick assumptions aren’t necessarily right

We make these kinds of justifying assumptions all day long, not just about social inequality. We’re constantly trying to make sense of everything we see around us.

When people generate explanations for the events and patterns they encounter in the world (for instance, orange juice being served at breakfast), they often do so quickly, without a whole lot of concern for whether the answer they come up with is 100% correct. To devise these answers on the spot, our explanation-generating system grabs onto the first things that come to mind, which are most often inherent facts. We look to simple descriptions of the objects in question – orange juice has vitamin C – without considering external information about the history of these objects or their surroundings.

What this means is the bulk of our explanations rely on the features of the things we’re trying to explain – there must be something about orange juice itself, like vitamin C, that explains why we have it for breakfast. Because of the shortcuts in this explanation process, it introduces a degree of bias into our explanations and, as a result, into how we understand the world.

There’s gotta be a reason…

In our research, Andrei and I wanted to see if this biased tendency to explain using inherent information shaped people’s beliefs about inequality. We hypothesized that inherent explanations of inequalities directly lead to the belief that society is fair. After all, if there is some inherent feature of the members of Group A (such as work ethic or intelligence) that explains their high status relative to Group B, then it seems fair that Group A should continue to enjoy an advantage.

What we found confirmed our predictions. When we asked adults to explain several status disparities, they favored explanations that relied on inherent traits over those that referred to past events or contextual influences. They were much more likely to say that a high-status group achieved their advantage because they were “smarter or better workers” than because they had “won a war” or lived in a prosperous region.

Furthermore, the stronger a participant’s preference for inherent explanations, the stronger their belief that the disparities were fair and just.

In order to ensure that this tendency wasn’t simply the result of a desire to reduce negative emotions, we told our participants about fictional disparities on other planets. Unlike the inequalities they may encounter in their everyday lives, our imaginary inequalities (for instance, between the Blarks and the Orps on Planet Teeku) would be unlikely to make participants feel bad. These made-up scenarios allowed us to see that people do jump to the same kinds of justifications even when we aren’t trying to alleviate negative feelings.

Kids buy into inherent explanations for inequality

We also asked these questions of an additional group of participants who should be even less likely to experience anxiety about their place in society when thinking about status disparities on alien planets: young children. Just like our adult participants, children as young as four years of age showed a strong preference for inherent explanations for inequality.

When we asked them to generate explanations, they were almost twice as likely to say that the high-status Blarks were more intelligent, worked harder, or were “just better” than the low-status Orps than they were to mention factors such as the neighborhood, family or history of either group. This preference promoted a belief that conditions were fair and worthy of support.

These findings suggest that the public’s misconceptions of inequality are, at least to some extent, due to our basic mental makeup. Primitive cognitive processes that allow us to create explanations for all the things we encounter in the world may also bias us to see our world as fair.

But the tendency to rely on inherent explanations, and adopt the subsequent belief that things are as they should be, is not unavoidable.

When we told children, for instance, that certain disparities were due to historical and contextual factors (rather than built-in, fundamental features of the aliens), they were much less likely to endorse those disparities as fair and just. Taking time to consider the many factors – both inherent and external – that contribute to social status may be an effective tool for developing a reasoned and critical perspective on our society in the face of growing inequality.

- Income inequality

- Social sciences

- Developmental psychology

- Negative emotions

Biocloud Project Manager - Australian Biocommons

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Deputy Editor - Technology

November 24, 2014

The problem isn’t that life is unfair – it’s your broken idea of fairness

258k shares Share on Facebook Share on Twitter

Unless you’re winning, most of life will seem hideously unfair to you.

The truth is, life is just playing by different rules.

The real rules are there. They actually make sense. But they’re a bit more complicated, and a lot less comfortable, which is why most people never manage to learn them.

Rule #1: Life is a competition

That business you work for? Someone’s trying to kill it. That job you like? Someone would love to replace you with a computer program. That girlfriend / boyfriend / high-paying job / Nobel Prize that you want? So does somebody else.

We’re all in competition, although we prefer not to realise it. Most achievements are only notable relative to others. You swam more miles, or can dance better, or got more Facebook Likes than the average. Well done.

It’s a painful thing to believe, of course, which is why we’re constantly assuring each other the opposite. “Just do your best”, we hear. “You’re only in competition with yourself”. The funny thing about platitudes like that is they’re designed to make you try harder anyway . If competition really didn’t matter, we’d tell struggling children to just give up.

Fortunately, we don’t live in a world where everyone has to kill each other to prosper. The blessing of modern civilisation is there’s abundant opportunities, and enough for us all to get by, even if we don’t compete directly.

But never fall for the collective delusion that there’s not a competition going on. People dress up to win partners. They interview to win jobs. If you deny that competition exists, you’re just losing. Everything in demand is on a competitive scale. And the best is only available to those who are willing to truly fight for it.

Rule #2. You’re judged by what you do, not what you think

Society judges people by what they can do for others . Can you save children from a burning house, or remove a tumour, or make a room of strangers laugh? You’ve got value right there.

That’s not how we judge ourselves though. We judge ourselves by our thoughts .

“I’m a good person”. “I’m ambitious”. “I’m better than this.” These idle impulses may comfort us at night, but they’re not how the world sees us. They’re not even how we see other people.

Well-meaning intentions don’t matter. An internal sense of honour and love and duty count for squat. What exactly can you and have you done for the world?

Abilities are not prized by their virtue. Whatever admiration society awards us, comes from the selfish perspectives of others. A hard working janitor is less rewarded by society than a ruthless stockbroker. A cancer researcher is rewarded less than a supermodel. Why? Because those abilities are rarer and impact more people.

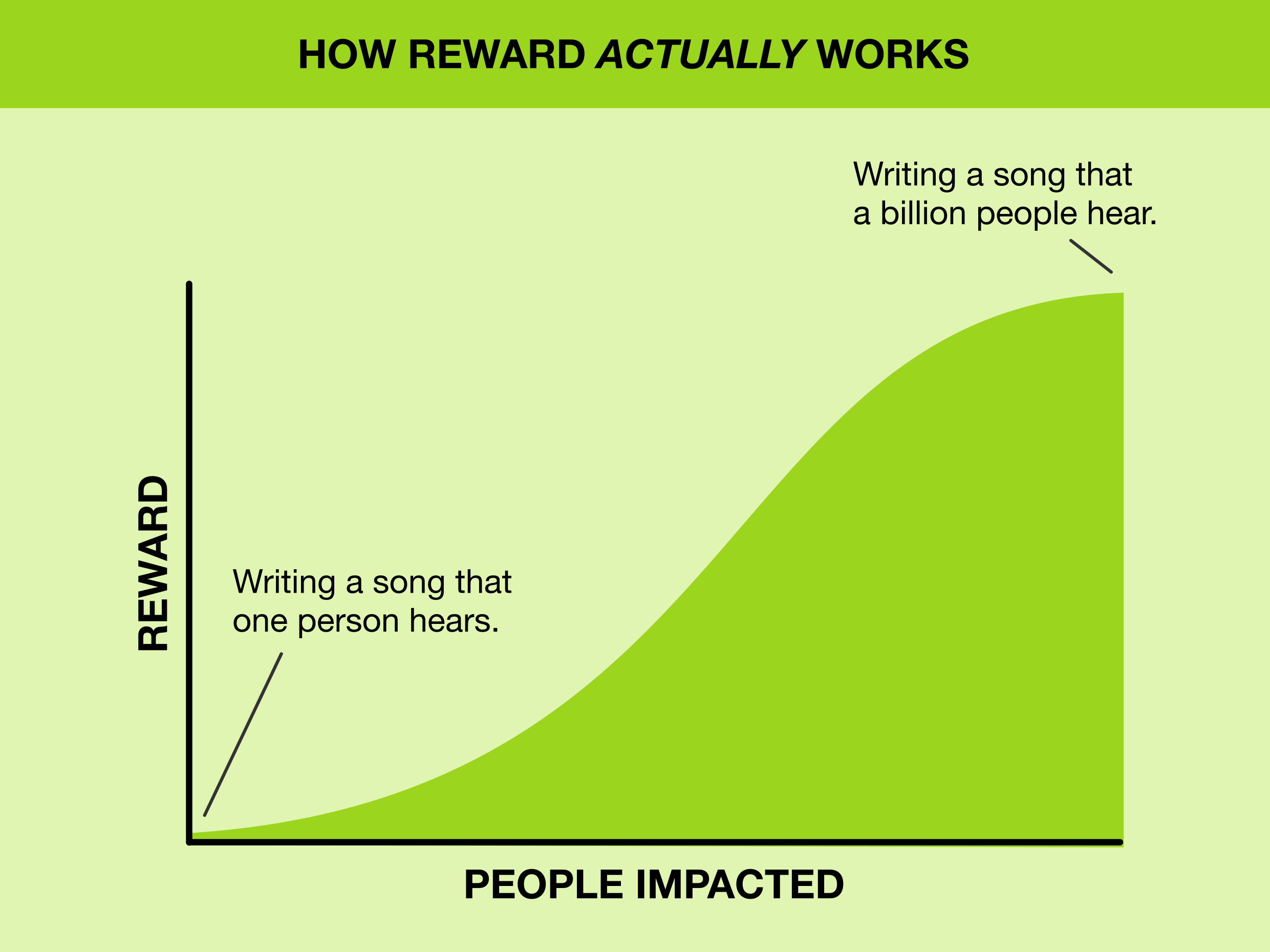

We like to like to think that society rewards those who do the best work. Like so:

But in reality, social reward is just a network effect. Reward comes down mostly to the number of people you impact :

Write an unpublished book, you’re nobody. Write Harry Potter and the world wants to know you. Save a life, you’re a small-town hero, but cure cancer and you’re a legend. Unfortunately, the same rule applies to all talents, even unsavoury ones: get naked for one person and you might just make them smile, get naked for fifty million people and you might just be Kim Kardashian.

You may hate this. It may make you sick. Reality doesn’t care. You’re judged by what you have the ability to do, and the volume of people you can impact. If you don’t accept this, then the judgement of the world will seem very unfair indeed.

Rule #3. Our idea of fairness is self interest

People like to invent moral authority. It’s why we have referees in sports games and judges in courtrooms: we have an innate sense of right and wrong, and we expect the world to comply. Our parents tell us this. Our teachers teach us this. Be a good boy, and have some candy.

But reality is indifferent. You studied hard, but you failed the exam. You worked hard, but you didn’t get promoted. You love her, but she won’t return your calls.

The problem isn’t that life is unfair; it’s your broken idea of fairness.

Take a proper look at that person you fancy but didn’t fancy you back. That’s a complete person . A person with years of experience being someone completely different to you. A real person who interacts with hundreds or thousands of other people every year.

Now what are the odds that among all that, you’re automatically their first pick for love-of-their-life? Because – what – you exist? Because you feel something for them? That might matter to you , but their decision is not about you .

Similarly we love to hate our bosses and parents and politicians. Their judgements are unfair. And stupid. Because they don’t agree with me! And they should! Because I am unquestionably the greatest authority on everything ever in the whole world!

It’s true there are some truly awful authority figures. But they’re not all evil, self-serving monsters trying to line their own pockets and savour your misery. Most are just trying to do their best, under different circumstances to your own.

Maybe they know things you don’t – like, say, your company will go bust if they don’t do something unpopular. Maybe they have different priorities to you – like, say, long term growth over short term happiness.

But however they make you feel , the actions of others are not some cosmic judgement on your being. They’re just a byproduct of being alive.

Why life isn’t fair

Our idea of fairness isn’t actually obtainable. It’s really just a cloak for wishful thinking.

Can you imagine how insane life would be if it actually was ‘fair’ to everyone? No-one could fancy anyone who wasn’t the love of their life, for fear of breaking a heart. Companies would only fail if everyone who worked for them was evil. Relationships would only end when both partners died simultaneously. Raindrops would only fall on bad people.

Most of us get so hung up on how we think the world should work that we can’t see how it does. But facing that reality might just be the key to unlocking your understanding of the world, and with it, all of your potential.

Enjoyed this? Get future posts emailed to you .

Keep reading

How to find your passion

You can do anything, if you stop trying to do everything

3.2k shares

How to master your life

Comment rules: Critical is fine, but if you’re trolling, I'll delete your stuff. Have fun and thanks for adding to the conversation.

Oliver Emberton

Founder of Silktide , writer, pianist, programmer, artist and general busy bee. Here I write about life and how to better it.

Get notified when I write something new

No spam, ever. View preview .

© Oliver Emberton 2024.

Website by Delighten

Advertisement

Life is not Fair: Get Used to It! A Personal Perspective on Contemporary Social Justice Research

- Open access

- Published: 15 July 2023

- Volume 36 , pages 293–304, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Adrian Furnham ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7545-8532 1

2486 Accesses

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This paper offers a very personal perspective on the Social Justice research world, much of which is to be found in this journal. It is my contention that this research has become too inward looking and detached from other mainstream and important issues. I also highlight some areas that I think neglected such as the Problem of Evil and Stoicism as a coping mechanism for misfortune.

Similar content being viewed by others

Social Identity Theory

Systemic racism: individuals and interactions, institutions and society

Mahzarin R. Banaji, Susan T. Fiske & Douglas S. Massey

The Social Learning Theory of Crime and Deviance

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Many academic disciplines are interested in the concept of justice, particularly law, philosophy, sociology and theology. Justice is about equality/equity, fairness, impartiality, legality, and trustfulness. However, one person’s justice is another’s injustice, and there is the rub: Most people would say justice is desirable, it is how they diversely define (and hope to achieve) it that can be the (academic) problem.

The title of this paper comes from the famous advice of the multi-billionaire Bill Gates who said young people should accept the realities of life. He noted that they needed to keep striving for success despite the obstacles that stand in our way. Instead of giving up or being discouraged, strive to be resilient and find ways to overcome challenges. It was not a call to campaign against injustice, but rather a way to try to cope with the inevitable truth. A friend, however, suggested I add “ So get used to challenging it ” arguing as so many Justice Researchers do, that we should all “get involved”, while I believe there may be a time and place to simply accept the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune”.

Psychology too has had a long-standing research agenda into justice. Developmental psychologists are interested in moral development, and how children come to understand fairness and justice in the world. Social psychologists have been interested in how people understand and react to justice and injustice, as well as, most importantly in their view, how to reduce injustice. Personality/Differential psychologists have been interested in systematic individual differences in beliefs about, and behaviour relating to, various forms of justice. Clinical psychologists have been concerned with how people cope with injustices visited upon themselves and others. Forensic psychologists have become concerned with how best to deal with those who are perpetrators or victims of injustice. Work psychologists have also been interested in Humanitarian Work Psychology, are concerned with how fair incomes and treatment in, and at, work can benefit groups and individuals alike. More recently, Environmental psychologists have become very involved in these issues especially concerns with climate change, farming practices and misuse of environmental resources.

As Torres-Harding et al., ( 2012 ) noted, “ social justice is consistently described as a value or belief, encompassing the idea that people should have equitable access to resources and protection of human rights. In addition, definitions of social justice typically involve power. Each definition encompasses the idea that structural and social inequalities should be minimized, and that society should work toward empowerment with people from disadvantaged or disempowered groups. Thus, participation, collaboration, and empowerment are all key components of social justice work. Social justice is a fundamental value of the community psychology field, particularly due to its emphasis on eliminating oppressive social conditions and promoting wellness” (p. 78).

In this paper, I will offer some personal reflections on social justice research. I was asked to reflect on a some very specific questions which I do in the conclusion.

The Bigger Picture

As noted above, most of the social sciences have been interested in justice, because of the importance and relevance of this topic to so much in life. People are confronted with injustices of many kinds and have to try to make sense of, and then deal with them. The more interesting question though is, when and how do people decide some system is actually broken, and needs fixing itself.

Ellenbogen ( 1986 ) in a very memorable and humourous way distinguished between how different religions understand injustice, and how psychotherapists deal with it. Of course, these are rather simple-minded stereotypes, and possibly even “offensive” to certain groups, because of the way they try to encapsulate and distinguish between various conceptualisations of injustice. Nevertheless, I believe it illustrates forcefully some of the numerous and profound differences in the ways injustice/evil/sh*t is considered.

It is clear injustice, here described as “sh*t happens” is an extremely important issue and that many struggle for an explanation for its existence, but also how to cope with it. It is very big topic indeed. The fundamental “take-away” for me is take a much wider view.

What this eccentric and amusing table illustrates is something, I feel, is important. It is about how individuals and groups have tried to come to terms with the fact that life is not fair and that we need a way of understanding why. Equally, we need to know how best to deal with the vicissitudes of everyday life: to right wrongs, prevent injustice, cruelty and evil: that is doing something, anything, about it.

In many ways, it is important to understand social justice in a wider context. One such approach that I really appreciated was the recent attempt of Krebs ( 2008 ) with his evolutionary account of the acquisition of a sense of justice. He argued that the mechanisms that give rise to a sense of justice evolved to help early humans maximize their gains from cooperative social interactions. A sense of justice encourages group members to distribute resources in fair ways ( distributive justice), to honour the commitments they make to others ( commutative justice), to punish cheaters ( corrective justice), and to develop effective and co-operative ways of resolving conflicts ( procedural justice). Thus, we inherit a disposition to react positively to being treated fairly and negatively to being treated unfairly, to pass judgement on those who treat others fairly or unfairly, and to feel obliged to pay others back by rewarding and punishing them appropriately.

“To achieve these goals, people use the tools with which they have been endowed by natural selection, especially language, perspective-taking abilities, and social intelligence. Although it is naïve to expect people to possess a universal sense of justice that consistently disposes them to make fair and impartial decisions that jeopardize their adaptive interests, it is realistic to expect people to be able to counteract one another’s biases in ways that enable them to make fair decisions in contexts in which such decisions advance everyone’s interests in optimal ways” (p. 244).

In this sense, social justice is a very big and important problem with which people have struggled for all time. The question is what psychologists “bring to the table”? And how has the last 30–50 years of Social Justice research made any theoretical or practical headway?

Justice Sensitivity and Justice Research

I have been struck at conferences and reading journals how “philosophically homogenous” researchers (and hence their research) is, in this area. Indeed, I wonder if it is possible that Justice Researchers are attracted to the field because of their particular justice sensitivity? The idea was identified over 35 years ago (Huseman et al., 1987 ). I consider whole issue of sensitivity to injustice maybe as Freud observed: we study our own problems.

Equity sensitivity is usually classified as relatively stable personality trait, which means that people are supposed to react to just or unjust situations in a consistent way though others have argued it is situation specific (Wijn & van den Bos, 2010 ). Researchers have determined three different types of justice-sensitive people namely benevolents, equity sensitives, and entitleds . Benevolents are referred to as “ givers ” because they are willing to bestow as much as possible to the people and organizations but are relatively unaffected by unfair treatment. They are prepared to experience personal discrimination, unfairness and injustice for a variety of personal reasons, and unlikely to complain or attempt some recompense. Some religions would strongly approve of this behaviour which is self-sacrificial for the greater good.

The counterparts are entitleds who are also labeled “ takers ” . Their ultimate ambition is to maximize their outcomes. They appear selfish, egocentric and deeply concerned about getting what they can from others. In between, there are “ equity sensitives ” who seek to achieve a balance between input and outcome.

As these different categorizations suggest, there are systematic and predictable behavioural differences between the three types. Benevolents are more likely to tolerate unfair payment, whereas entitleds are more likely to react stronger than benevolents to pay inequities by reducing their job performance (Allen & White, 2002 ). There are interesting questions about the development of justice sensitivity and how it can be appropriately moderated.

To be clear, there is in this area the older construct of equity sensitivity and the newer construct of justice sensitivity. The focus of equity sensitivity is on the outcome of an allocation—which limits the construct to distributive justice. The focus of justice sensitivity is on the role a person can play in any incidence of injustice. A person can be the victim of injustice (victim sensitivity), the observer of injustice (observer sensitivity), the beneficiary of injustice (beneficiary sensitivity), and the perpetrator of injustice (perpetrator sensitivity). Thus, the concept of justice is not limited to distributive justice in the justice sensitivity construct but includes all kinds of injustice (distributive, procedural, retributive, restorative, interactive, legal).

Another important difference is the assumed dimensionality. The justice sensitivity construct conceptualizes all facets (victim, observer, beneficiary, perpetrator) as potentially independent components (a person can be victim sensitive and beneficiary sensitive). By contrast, equity sensitivity is one-dimensional construct (a benevolent person cannot be entitled). These differences have important implications on measurement and research on developmental origins, behavioural outcomes, and correlations (with personality traits, for example). Justice sensitivity research has shown that all facets have some uniqueness which means that they overlap only partially and that they have unique relations with other variables. Yet all studies show a systematic pattern of overlap among the facets. Observer-, beneficiary-, and perpetrator sensitivity correlate highly among each other and seem to reflect a genuine concern for justice for others. Victim sensitivity correlates only moderately with the other factors.

I wondered, however, given the above ideas, that it maybe possible to divide researchers themselves into three categories: justice/equity sensitive, justice/equity indifferent, justice/equity accepting. The first category would be people eager to perceive, understand and, more importantly, redress or reduce injustice anywhere they see it. Of course, they may be much more sensitive to injustice in certain areas (education, health, work) and more or less personally committed to various forms of action. Essentially, they “filter” a great deal of the world, through a justice lens. Thus, they would be attracted to social justice research and probably be very homogenous in terms of their socio-political outlook. Perhaps younger researchers have a keener—and different—sense(s) of injustice at being left behind, than do say older researchers. But they are fellow-travellers and attracted to social justice research as a way of partly creating it.

Second, there are those who understand the concept of justice and injustice, but it is less important to them than a whole range of other activities and issues. They do not go out of their way to consider and possibly rectify issues of injustice. In this sense, they are relatively indifferent to justice issues and would not be particularly interested in research in the area. They would be a very heterogeneous group. This may be the case unless and until some injustice affects them, or they are affected by injustices (and material hardships, etc.) in their earlier life.

Third, there are those who are accepting of the “vicissitudes of life”, seeing most injustices perhaps as normal and a consequence of the human condition about which little can, or should, be done. “Life is not fair: get used to it”. There are all sorts of reasons why this occurs, many of which are difficult if not impossible to redress. Their basic philosophy is: You are “dealt-a-hand” in life; you cannot choose your parents; sh*t happens. The best strategy is not to be obsessed by some retribution but rather learn to cope and exploit what you have been given. They would therefore be less interested in social justice research and in devising strategies to increase it.

Inevitably, these various “types” may hold highly negative views about the other which can be most clearly seen in political debate. Thus, the justice accepting may view the justice sensitive as impractical, “bleeding-heart” liberals whose attempts at rectifying justice are ineffective, misplaced and indeed morally wrong. On the other hand, the justice sensitive may view the justice accepting as callous, unethical and morally corrupt. It could be argued that awareness and mutual understanding is the key to solve these justice dilemmas between justice “types”.

The question for research is this. Do the personal views on justice-injustice and equity-equality of researchers bias their hypotheses, methods and conclusions? Do they design studies to attempt to provide evidence for their particular theories and neglect, ignore and “pooh-pooh” those who take an opposite perspective? Are too many Social Justice researchers disinterested enough to do good work?

Believing the World is Just

My “way-into” this area was initially through the Just World literature. I read Lerner’s ( 1980 ) book while doing my doctorate and was completely hooked. My first study was on the BJW and attitudes to poverty (Furnham & Gunter, 1984 ), while the second was a cross-cultural study comparing BJWs in a very unjust society, namely South Africa, with one arguably more just, namely Great Britain (Furnham, 1985 ). I worked on the topic for years (Furnham, 1991 , 1992 , 1995 , 1998 ). I later published two reviews (Furnham, 2003 ; Furnham & Procter, 1989 ). I went to conferences in America and Germany and met many of the top scholars in the field. It was, and still is, a comparatively small group dominated by Canadians and Germans. The field is flourishing and expanding (Bartholomaeus & Strelan, 2019 ;

A lot of the early work seemed to suggest that those who believed the world was essentially a just place were both naïve and bad because, in order to sustain their BJW, they derogated “innocent victims”. Still today this expanding and voluminous literature seems to focus on the “evil and naïve consequences” of a BJW. Thus, it is argued, it is patently obvious, the world is not just and people who believe it is are deluded and often victim-blamers in their attempt to justify their naïve beliefs.

In an early paper, I made some distinction between those who felt the world was just (people got what they deserved), unjust (the good and virtuous were punished) and the a-just or random world where just deeds were randomly rewarded and punished. We also distinguished between three other worlds: the personal, interpersonal and social world (Furnham & Procter, 1992 ). I thought the early work and early measure too simple, “scatter-gun”, and naïve. It seemed to me that people could believe in different worlds for different reasons. I might believe the political and economic world unjust; but the world of personal relations just. But most of all, I personally felt the world was a-just. It rains on the just and unjust alike (Matthew 5). However, some would argue that what is, is not necessarily what it could be, that is made fairer.

But much more importantly, I felt it was personally much more disadvantageous to believe the world was unjust as opposed to just. Imagine believing good actions were punished as opposed to rewarded: good people are assassinated, while dictators live to an old age. A major development at the turn of the millennium was to view the BJW as a healthy coping mechanism rather than being the manifestation of anti-social beliefs and prejudice (Dalbert, 2001 ; Furnham, 2003 ). There was a subtle movement from focusing on victim derogation to positive coping. Studies have portrayed BJW beliefs as a personal resource or coping strategy, which buffers against stress and enhances achievement behaviour. Of course, as pointed out above one could believe in a just personal world, an a-just interpersonal world and an unjust political world at the same time. Further, there must be degrees in which the world is just or unjust: not simply a stark binary option.

For the first time, BJW beliefs were seen as an indicator of mental health and planning. This does not contradict the more extensive literature on BJW and victim derogation. Rather it helps explain why people are so eager to maintain their beliefs which may be their major coping strategy. BJW is clearly functional for the individual. Rather than despise people for believing the world is (relatively) just, which certainly we teach our children, the BJW may be seen as a fundamental, cognitive coping strategy. However, the directionality is not always clear: Do mentally healthy people believe the world is just, or do just world believers deal better with the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune”. Or indeed is there actually a reciprocal causal relationship. Believing the world is just when it is not may be a maladaptive bruising experience.

One question is how BJW is related to other coping strategies and which are favoured by healthy individuals who have low BJW beliefs. Again, the focus is on how BJW relate to personal experiences rather than that of others. I believe from personal experience that “what goes around, comes around”, that for the most part good deeds are rewarded and vice versa. That—the bad are punished and the good rewarded—is what we teach our children, though we no doubt all believe this simple observation needs to be caveated and explained (Baier et al., 2013 ).

Two Neglected Areas

I have a very wide range of research interest and believe, as noted above SJ researchers have become rather narrow. Two such areas illustrate my point.

The Problem of Evil (Theodicy)

Theodicy is an explanatory concept, and term used by scholars, to illustrate the ways in which people try to find meaning in injustice and the suffering that results. Why does God allows evil things to occur (Blumenthal, 1993 ; Chester, 1998 ; Parro, 2021 ; Tinker, 2009 ). It is also known as the “Problem of Evil”, (PoE), which is most relevant to those who believe in an omnipotent, omniscient and omni-present deity and attempting to reconcile the observation that “bad things happen to good people” (Furnham & Brown, 1992 ). Furnham and Robinson ( 2023 ) some have talked about the problem s of evil, sceptical theism and the like (Church et al., 2021 ). It is all about injustice in the world.

The PoE is an enormous problem for believers in a Just God: one of peace, love and justice. Why does he allow injustice in the world?

Some suggest that suffering from various forms of injustice, including social justice, can be mitigated or partly overcome by understanding why an individual found themselves in a particular negative situation. Theologians have distinguished between moral evil, caused by human agency, and various natural evils.

Clearly, mono-theistic and pan-theistic religions favour predominantly different solutions and explanations though some, like the doctrine of karma (behaviour in a previous life), are specific to particular religions. Why this is an interesting and neglected literature is because it examines how people “deal with” obvious, inexplicable and outrageous injustice in the world. How and why does a loving, all-powerful God allow such cruelty and injustice to occur? Indeed is injustice sent by God to test us?

I wonder how many SJ researchers are believers and how they have resolved the problem?

Indifference to, and Coping with, Social Injustice: Stoicism

Given that we are all, at some time another “victims” of injustice, what is the best way we can cope with it. Is it better to attempt to ignore or downplay the issue or confront it? Life is not fair: get used to it.

The denial and suppression of emotion is at the heart of the modern, and ancient, concept of stoicism and fortitude. It has been associated with many different religions and investigated as a potentially adaptive coping style (Pathak et al., 2017 ).

The stoics believed that being indifferent to pain and pleasure and exercising emotional self-control were the best routes to happiness. Stoicism as a philosophy and a coping style has not appeared directly in psychology, though similar ideas have appeared like repression, suppression, detachment, fortitude and toxic-avoidant coping. Furthermore, whilst the classic interpretation of stoicism is as a healthy and desirable worldview and coping mechanism, the related psychological concepts have nearly always been seen as being maladaptive (Moore et al, 2013 ). It has also been dismissed as a pathological, masculine, “Big boys don’t cry” maladaptive coping mechanism, related to many poor health outcomes.

The concept of stoicism is not dissimilar to that of repression, although the former seems overall more a functional—and the latter a more dysfunctional—coping strategy. More importantly, stoicism involves the suppression of both pleasure and suffering, whereas repression seems more concerned with the repression of only negative emotions. Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether stoicism as a coping strategy is psychologically adaptive or maladaptive. Repression is often confused with suppression, another type of defence mechanism. Whereas repression involves unconsciously blocking unwanted thoughts or impulses, suppression is conscious and voluntary, i.e. suppression represents a deliberate attempt to forget or not think about painful or unwanted thoughts.

So, my idea is that Social Justice researchers have neglected the clinical literature on personal and effective ways in which people attempt to deal with injustice (Pargament, 2011 ).

Advice to Young Scholars

There will never be a shortage of areas in which to explore concepts of justice. Current concerns include climate change, sex roles, retribution from slavery, the new world of work, etc. It would not be difficult to apply theories and measures to these areas and establish one’s academic research reputation. In doing so, new “topic-specific” measures may be constructed, new mini-theories developed and the field both consolidated and expanded. Plus, the world could actually be changed.

I have three worries and advice for young scholars who choose to take this path:

First, that the social justice literature gets too cut off from the mainstream. Researchers publish in specialist journals and go to specialist conferences. As noted above, social justice touches many disciplines and it is important to “keep up” with changes in the field. Do SJ researchers take into consideration changes in evolutionary psychology, neuro-psychology and cyber-psychology to make sure they are “with the project”? I think for too long evolutionary perspectives have been ignored. It is never good turn inward, particularly with such an interesting, important and multidimensional research agenda. Specialism is often, paradoxically, the enemy of progress.

Second, that the ideology of researchers too frequently permeates their research. It was R. S. Peters who observed that “ patient passive presuppositionless enquiry is a methodological myth ”. Are too many researchers coming to the research with a particular set of biases? Too eager perhaps to see injustice; too eager to “right-wrongs”; too angry to be sufficiently disinterested? It seems that most researchers in this area share a number of socio-political assumptions which means they are not confronted sufficiently to defend them. Politically left-wing, easily offended, depression-prone? An obsession with injustice and super-justice-sensitivity and a deep desire to right-wrongs is unlikely to lead to personal happiness or fulfillment? Perhaps, as noted above, it is often socio-political concerns that get people into the field.

Third, that the “objects/issues” of injustice become too wide. As noted about the theodicy literature suggests that there are three “grand attributions” for evil/injustice/unfairness: the will of (a) God; bad luck/chance/fate; and (deliberate) human actions. The ever growing and passionate debate about climate change illustrates this point well. To what extent is global warming a natural occurring phenomenon and what due to human behaviour: or is that climate denial. Do too many justice researchers want to see the causes of bad things in human behaviour because they can be changed. “Life is not fair: Do something about it”.

So, to briefly answer the questions I was asked

“What do you think about the current state of social justice scholarship?

I am not sure it has progressed a great deal over the last decade: Are there new theories, methods, insights? Can neuro-science help? I am not sure and wish the field the best.

Where do you think it is, and should be heading? Is it going in the right direction?

I think SJ researchers should integrate themselves more in the mainstream. I have made the point about being inward looking. There are imaginative evolutionary theories of justice and I wonder what neuro-science has to offer as well as devising new, non-self-report measures of SJ.

What advice would you give a young justice scholar? What would you like the current generation of young justice scholars to spend their time and talents on?”

SJ research is multi-disciplinary which is often a serious challenge as the different disciplines have very different research priorities. If I were a young scholar, I think I would have three interests: first, individual differences in conceiving of, and reacting to justice and injustice and devising new measures of those differences; second, looking at cross-cultural differences in the understanding of SJ particularly in ideas about the cause, and repair of injustice; third, studying those social groups who are often extremists and who are concerned about very specific areas of injustice like climate change, sex roles and wealth distribution.

Too much research on social justice is about social in justice. It is too easy for scholars to become somewhat myopic because of their specialism. New journals and societies are founded to cater for this and often those who join and publish spend too much time talking to each other. People appear to be attracted to the area particularly because of their own values and beliefs. This is called ASA theory: Attraction-Selection-Attrition. Indeed, some see their research as a personal quest and may as a consequence become insufficiently disinterested to do good research.

Life is not fair. Perhaps researchers should concentrate more on helping people accept this self-evident truth? As St Francis has been reputed to say “Lord, grant me the strength to change the things I can, the serenity to deal with the things I cannot change, and the wisdom to know the difference”? Or, as one of my “critical friends” preferred to conclude: So we can and should change what can be changed, which is much of what happens and will.

Allen, R. S., & White, C. S. (2002). Equity sensitivity theory: A test of responses to twotypes of under-reward situations. Journal of Managerial Issues, 14 , 435–451.

Google Scholar

Baier, M., Kals, E., & Müller, M. M. (2013). Ecological belief in a just world. Social Justice Research, 26 (3), 272–300.

Article Google Scholar

Bartholomaeus, J., & Strelan, P. (2019). The adaptive, approach oriented correlates of belief in a just world for the self: A review of the research. Personality and Individual Differences, 151 , 109485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.06.028

Blumenthal, D. (1993). Facing the abusing god: A theology of protest . Westminster John Knox.

Chester, D. K. (1998). The theodicy of natural disasters. Scottish Journal of Theology, 51 (4), 485–506. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0036930600056866

Church, M. I., Carlson, R., & Barrett, J. L. (2021). Evil intuitions? The problem of evil, experimental philosophy, and the need for psychological research. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 49 (2), 126–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091647120939110

Dalbert, C. (2001). The justice motive as a personal resource: Dealing with challenges and critical life events. Kluwer Academic/plenum Publishers . https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-3383-9

Ellenbogen, G. (1986). Oral sadism and the vegetarian personality . Brunner/Mazel.

Furnham, A. (1985). Just world beliefs in an unjust society: A cross-cultural comparison. European Journal of Social Psychology, 15 (3), 363–366. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420150310

Furnham, A. (1991). Just world beliefs in twelve societies. JoUrnal of Social Psychology, 133 (3), 317–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1993.9712149

Furnham, A. (1992). Relationship between knowledge of and attitudes towards AIDS. Psychological Reports, 71 (3), 1149–1150. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1992.71.3f.1149

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Furnham, A. (1995). The just world, charitable giving and attitudes to disability. Personality and Individual Differences, 19 (4), 577–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(95)00090-S

Furnham, A. (1998). Measuring the beliefs in a just world. In L. Montada & M. J. Lerner (Eds.), Responses to victimizations and belief in the just world (pp. 141–162). Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-6418-5_9

Chapter Google Scholar

Furnham, A. (2003). Belief in a just world: Research progress over the past decade. Personality and Individual Differences, 34 (5), 795–817. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00072-7

Furnham, A., & Brown, L. B. (1992). Theodicy: A neglected aspect of the psychology of religion. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 2 (1), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327582ijpr0201_4

Furnham, A., & Gunter, B. (1984). Just world beliefs and attitudes towards the poor. British Journal of Social Psychology, 23 (3), 265–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1984.tb00637.x

Furnham, A., & Procter, E. (1989). Belief in a just world: Review and critique of the individual difference literature. British Journal of Social Psychology, 28 (4), 365–384. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1989.tb00880.x

Furnham, A., & Procter, E. (1992). Sphere-specific just world beliefs and attitudes to AIDS. Human Relations, 45 (3), 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679204500303

Furnham, A., & Robinson, C. (2023). Correlates of beliefs about, and solutions to, the problem of evil. Mental Health, Religion and Culture . https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2023.2219633

Huseman, R. C., Hatfield, J. D., & Miles, E. W. (1987). A new perspective on equity theory: The equity sensitivity construct. Academy of Management Review, 12 , 222–234.

Krebs, D. L. (2008). The evolution of a sense of justice. In J. Duntley & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), Evolutionary forensic psychology: Darwinian foundations of crime and law (pp. 230–246). Oxford Academic. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195325188.003.0012

Lerner, M. J. (1980). Belief in a just world: A fundamental delusion . Plenum Publishing Corporation.

Book Google Scholar

Moore, A., Grime, J., Campbell, P., et al. (2013). Troubling stoicism: Sociocultural influences and applications to health and illness behaviour. Health, 17 , 159–173.

Pargament, K. I. (2011). Religion and coping: The current state of knowledge. In S. Folkman (Ed.), Oxford handbook of stress, health, and coping (pp. 269–288). Oxford University Press.

Parro, F. (2021). The problem of evil: An economic approach. Kyklos, 74 (4), 527–551. https://doi.org/10.1111/kykl.12277

Pathak, E. B., Wieten, S. E., & Wheldon, C. W. (2017). Stoic beliefs and health: development and preliminary validation of the Pathak-Wieten Stoicism Ideology Scale. BMJ Open, 7 (11), e015137. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015137

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tinker, M. (2009). Why do bad things happen to good people? Christian Focus.

Torres-Harding, S. R., Siers, B., & Olson, B. D. (2012). Development and psychometric evaluation of the social justice scale (SJS). American Journal of Community Psychology, 50 (1–2), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-011-9478-2

Wijn, R., & Bos, K. V. (2010). Toward a better understanding of the justice judgment process: The influence of fair and unfair events on state justice sensitivity. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40 , 1294–1301.

Download references

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Kjell Törnblom and Ali Kazemi for the invitation to write this paper and to Manfred Schmitt, Stuart Carr, Michael Bond, Elisabeth Kals and Nick Emler for comments on earlier drafts.

Open access funding provided by Norwegian Business School.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

BI: Norwegian Business School, Nydalen, Oslo, Norway

Adrian Furnham

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Adrian Furnham .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Furnham, A. Life is not Fair: Get Used to It! A Personal Perspective on Contemporary Social Justice Research. Soc Just Res 36 , 293–304 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-023-00417-7

Download citation

Accepted : 22 June 2023

Published : 15 July 2023

Issue Date : September 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-023-00417-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Has Life Been Unfair to You?

Five tools for getting past the anger and disappointment..

Posted July 30, 2014

Marty Nemko, Ph.D ., is a career and personal coach based in Oakland, California, and the author of 10 books.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Jamelle Bouie

The Supreme Court Is Playing a Dangerous Game

By Jamelle Bouie

Opinion Columnist

If the chief currency of the Supreme Court is its legitimacy as an institution, then you can say with confidence that its account is as close to empty as it has been for a very long time.

Since the court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization nearly two years ago, its general approval with the public has taken a plunge. As recently as the last presidential election year, according to the Pew Research Center , 70 percent of Americans said they had a favorable view of the court. In the wake of Dobbs, that number dipped to 44 percent. Twenty-four percent of Democrats, according to Pew, said they approved of the Supreme Court.

In the latest 538 average , just over 52 percent of Americans disapproved of the Supreme Court, and around 40 percent approved.

Does the court know about its precipitous decline with much of the public? It’s hard to say. It’s easier to answer a related question: Does it care? If the recent actions of the conservative majority are any indication, the answer is no.

Over the past month, members of that majority have effectively rewritten the 14th Amendment to functionally shield Donald Trump from the constitutional consequences of his actions leading up to and on Jan. 6. They have taken up the former president’s tendentious argument that he is immune to criminal prosecution for all actions taken while in office — postponing a trial and potentially denying the public the right to know, before we go to the polls in November, whether he is a criminal in the eyes of the law.

Most recently, the court allowed the State of Texas, governed by a cadre of some of the most reactionary conservatives in the country, to carry out its own immigration policy in contravention of both federal officials and the general precedent that it’s the national government that handles the national border, not the states.

It is enough to make teachers and practitioners of constitutional law wonder, as my colleague Jesse Wegman noted last month , whether there’s any reason to play the table as though it were still on the level — to continue to treat the court as if it were anything other than a partisan political institution.

Here I want to raise an additional point. It’s not just the recent actions of the Supreme Court — including the corrupt conduct of some of its members — that jeopardize its legitimacy and political standing but also the circumstances under which this particular court majority came into being.

There is no way to look past the fact that five of the six members of the conservative majority on the Roberts court were nominated by presidents who entered office without the winds of a popular majority. John Roberts and Samuel Alito, the author of Dobbs, were placed on the court by George W. Bush, who entered office short of a popular vote win and on the strength of a contested Electoral College victory. The other three — Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett — were nominated by Trump, who lost the national popular vote by more than two million ballots in 2016.

The three Trump justices bring additional baggage. Each one was nominated and confirmed in a show of partisan power politics. Gorsuch was the direct beneficiary of Senator Mitch McConnell’s blockade of the seat held by Justice Antonin Scalia, who died early in 2016. Republicans, led by McConnell, then the Senate majority leader, refused to give President Barack Obama’s nominee, Judge Merrick Garland of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, a hearing in the Senate Judiciary Committee. It was the first time the Senate had simply ignored a president’s nominee for the Supreme Court.

Kavanaugh was confirmed by a narrow vote of 50 to 48 (with one abstention and one absence) in the face of a credible accusation of sexual assault. Barrett was confirmed in flagrant violation of McConnell’s own rule for Supreme Court nominations. To block Garland, McConnell said that it was too close to an election to move forward; to confirm Barrett, McConnell said that it was too close to an election to wait.

There is no question that the Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs was the catalyst for its poor standing with the public. But the Dobbs majority owes itself to a garish Republican partisanship that almost certainly worked to weaken the political ground on which it stood in relation to the American people.

At the risk of sounding a little dramatic, you can draw a useful comparison between the Supreme Court’s current political position and the one it held on the eve of the 1860 presidential election.

It was not just the ruling itself that drove the ferocious opposition to the Supreme Court’s decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, which overturned the Missouri Compromise and wrote Black Americans out of the national community; it was the political entanglement of the Taney court with the slaveholding interests of the antebellum Democratic Party.

Six of the seven justices in the majority were Democratic appointments. The one who wasn’t, Samuel Nelson, was nominated by John Tyler, who was a Democrat before running on the Whig ticket with William Henry Harrison. Five of the justices were appointed by slave owners. At the time of the ruling, four of the justices were slave owners. And the chief justice, Roger Taney, was a strong Democratic partisan who was in close communication with James Buchanan, the incoming Democratic president, in the weeks before he issued the court’s ruling in 1857. Buchanan, in fact, had written to some of the justices urging them to issue a broad and comprehensive ruling that would settle the legal status of all Black Americans.

The Supreme Court, critics of the ruling said, was not trying to faithfully interpret the Constitution as much as it was acting on behalf of the so-called Slave Power, an alleged conspiracy of interests determined to take slavery national. The court, wrote a committee of the New York State Assembly in its report on the Dred Scott decision, was determined to “bring slavery within our borders, against our will, with all its unhallowed, demoralizing and blighted influences.”

The Supreme Court did not have the political legitimacy to issue a ruling as broad and potentially far-reaching as Dred Scott, and the result was to mobilize a large segment of the public against the court. Abraham Lincoln spoke for many in his first inaugural address when he took aim at the pretense of the Taney court to decide for the nation: “The candid citizen must confess that if the policy of the government upon vital questions, affecting the whole people, is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court, the instant they are made, in ordinary litigation between parties, in personal actions, the people will have ceased to be their own rulers.”

As much as ours is a dire moment for the future of the American republic, we can at least rest assured that we aren’t living through 1857 or 1860 or 1861. Santayana notwithstanding, history does not actually repeat itself. But this Supreme Court — the Roberts court — is playing its own version of the dangerous game that brought the Taney court to ruin. It is acting as if the public must obey its dictates. It is acting as if its legitimacy is incidental to its power. It is acting as if it cannot be touched or brought to heel.

The Supreme Court is making a bet, in other words, that it is truly unaccountable.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here's our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , WhatsApp , X and Threads .

Jamelle Bouie became a New York Times Opinion columnist in 2019. Before that he was the chief political correspondent for Slate magazine. He is based in Charlottesville, Va., and Washington. @ jbouie

Things you buy through our links may earn Vox Media a commission

- The Case for Marrying an Older Man

A woman’s life is all work and little rest. An age gap relationship can help.

In the summer, in the south of France, my husband and I like to play, rather badly, the lottery. We take long, scorching walks to the village — gratuitous beauty, gratuitous heat — kicking up dust and languid debates over how we’d spend such an influx. I purchase scratch-offs, jackpot tickets, scraping the former with euro coins in restaurants too fine for that. I never cash them in, nor do I check the winning numbers. For I already won something like the lotto, with its gifts and its curses, when he married me.

He is ten years older than I am. I chose him on purpose, not by chance. As far as life decisions go, on balance, I recommend it.

When I was 20 and a junior at Harvard College, a series of great ironies began to mock me. I could study all I wanted, prove myself as exceptional as I liked, and still my fiercest advantage remained so universal it deflated my other plans. My youth. The newness of my face and body. Compellingly effortless; cruelly fleeting. I shared it with the average, idle young woman shrugging down the street. The thought, when it descended on me, jolted my perspective, the way a falling leaf can make you look up: I could diligently craft an ideal existence, over years and years of sleepless nights and industry. Or I could just marry it early.

So naturally I began to lug a heavy suitcase of books each Saturday to the Harvard Business School to work on my Nabokov paper. In one cavernous, well-appointed room sat approximately 50 of the planet’s most suitable bachelors. I had high breasts, most of my eggs, plausible deniability when it came to purity, a flush ponytail, a pep in my step that had yet to run out. Apologies to Progress, but older men still desired those things.

I could not understand why my female classmates did not join me, given their intelligence. Each time I reconsidered the project, it struck me as more reasonable. Why ignore our youth when it amounted to a superpower? Why assume the burdens of womanhood, its too-quick-to-vanish upper hand, but not its brief benefits at least? Perhaps it came easier to avoid the topic wholesale than to accept that women really do have a tragically short window of power, and reason enough to take advantage of that fact while they can. As for me, I liked history, Victorian novels, knew of imminent female pitfalls from all the books I’d read: vampiric boyfriends; labor, at the office and in the hospital, expected simultaneously; a decline in status as we aged, like a looming eclipse. I’d have disliked being called calculating, but I had, like all women, a calculator in my head. I thought it silly to ignore its answers when they pointed to an unfairness for which we really ought to have been preparing.

I was competitive by nature, an English-literature student with all the corresponding major ambitions and minor prospects (Great American novel; email job). A little Bovarist , frantic for new places and ideas; to travel here, to travel there, to be in the room where things happened. I resented the callow boys in my class, who lusted after a particular, socially sanctioned type on campus: thin and sexless, emotionally detached and socially connected, the opposite of me. Restless one Saturday night, I slipped on a red dress and snuck into a graduate-school event, coiling an HDMI cord around my wrist as proof of some technical duty. I danced. I drank for free, until one of the organizers asked me to leave. I called and climbed into an Uber. Then I promptly climbed out of it. For there he was, emerging from the revolving doors. Brown eyes, curved lips, immaculate jacket. I went to him, asked him for a cigarette. A date, days later. A second one, where I discovered he was a person, potentially my favorite kind: funny, clear-eyed, brilliant, on intimate terms with the universe.

I used to love men like men love women — that is, not very well, and with a hunger driven only by my own inadequacies. Not him. In those early days, I spoke fondly of my family, stocked the fridge with his favorite pasta, folded his clothes more neatly than I ever have since. I wrote his mother a thank-you note for hosting me in his native France, something befitting a daughter-in-law. It worked; I meant it. After graduation and my fellowship at Oxford, I stayed in Europe for his career and married him at 23.

Of course I just fell in love. Romances have a setting; I had only intervened to place myself well. Mainly, I spotted the precise trouble of being a woman ahead of time, tried to surf it instead of letting it drown me on principle. I had grown bored of discussions of fair and unfair, equal or unequal , and preferred instead to consider a thing called ease.

The reception of a particular age-gap relationship depends on its obviousness. The greater and more visible the difference in years and status between a man and a woman, the more it strikes others as transactional. Transactional thinking in relationships is both as American as it gets and the least kosher subject in the American romantic lexicon. When a 50-year-old man and a 25-year-old woman walk down the street, the questions form themselves inside of you; they make you feel cynical and obscene: How good of a deal is that? Which party is getting the better one? Would I take it? He is older. Income rises with age, so we assume he has money, at least relative to her; at minimum, more connections and experience. She has supple skin. Energy. Sex. Maybe she gets a Birkin. Maybe he gets a baby long after his prime. The sight of their entwined hands throws a lucid light on the calculations each of us makes, in love, to varying degrees of denial. You could get married in the most romantic place in the world, like I did, and you would still have to sign a contract.

Twenty and 30 is not like 30 and 40; some freshness to my features back then, some clumsiness in my bearing, warped our decade, in the eyes of others, to an uncrossable gulf. Perhaps this explains the anger we felt directed at us at the start of our relationship. People seemed to take us very, very personally. I recall a hellish car ride with a friend of his who began to castigate me in the backseat, in tones so low that only I could hear him. He told me, You wanted a rich boyfriend. You chased and snuck into parties . He spared me the insult of gold digger, but he drew, with other words, the outline for it. Most offended were the single older women, my husband’s classmates. They discussed me in the bathroom at parties when I was in the stall. What does he see in her? What do they talk about? They were concerned about me. They wielded their concern like a bludgeon. They paraphrased without meaning to my favorite line from Nabokov’s Lolita : “You took advantage of my disadvantage,” suspecting me of some weakness he in turn mined. It did not disturb them, so much, to consider that all relationships were trades. The trouble was the trade I’d made struck them as a bad one.

The truth is you can fall in love with someone for all sorts of reasons, tiny transactions, pluses and minuses, whose sum is your affection for each other, your loyalty, your commitment. The way someone picks up your favorite croissant. Their habit of listening hard. What they do for you on your anniversary and your reciprocal gesture, wrapped thoughtfully. The serenity they inspire; your happiness, enlivening it. When someone says they feel unappreciated, what they really mean is you’re in debt to them.

When I think of same-age, same-stage relationships, what I tend to picture is a woman who is doing too much for too little.

I’m 27 now, and most women my age have “partners.” These days, girls become partners quite young. A partner is supposed to be a modern answer to the oppression of marriage, the terrible feeling of someone looming over you, head of a household to which you can only ever be the neck. Necks are vulnerable. The problem with a partner, however, is if you’re equal in all things, you compromise in all things. And men are too skilled at taking .

There is a boy out there who knows how to floss because my friend taught him. Now he kisses college girls with fresh breath. A boy married to my friend who doesn’t know how to pack his own suitcase. She “likes to do it for him.” A million boys who know how to touch a woman, who go to therapy because they were pushed, who learned fidelity, boundaries, decency, manners, to use a top sheet and act humanely beneath it, to call their mothers, match colors, bring flowers to a funeral and inhale, exhale in the face of rage, because some girl, some girl we know, some girl they probably don’t speak to and will never, ever credit, took the time to teach him. All while she was working, raising herself, clawing up the cliff-face of adulthood. Hauling him at her own expense.

I find a post on Reddit where five thousand men try to define “ a woman’s touch .” They describe raised flower beds, blankets, photographs of their loved ones, not hers, sprouting on the mantel overnight. Candles, coasters, side tables. Someone remembering to take lint out of the dryer. To give compliments. I wonder what these women are getting back. I imagine them like Cinderella’s mice, scurrying around, their sole proof of life their contributions to a more central character. On occasion I meet a nice couple, who grew up together. They know each other with a fraternalism tender and alien to me. But I think of all my friends who failed at this, were failed at this, and I think, No, absolutely not, too risky . Riskier, sometimes, than an age gap.

My younger brother is in his early 20s, handsome, successful, but in many ways: an endearing disaster. By his age, I had long since wisened up. He leaves his clothes in the dryer, takes out a single shirt, steams it for three minutes. His towel on the floor, for someone else to retrieve. His lovely, same-age girlfriend is aching to fix these tendencies, among others. She is capable beyond words. Statistically, they will not end up together. He moved into his first place recently, and she, the girlfriend, supplied him with a long, detailed list of things he needed for his apartment: sheets, towels, hangers, a colander, which made me laugh. She picked out his couch. I will bet you anything she will fix his laundry habits, and if so, they will impress the next girl. If they break up, she will never see that couch again, and he will forget its story. I tell her when I visit because I like her, though I get in trouble for it: You shouldn’t do so much for him, not for someone who is not stuck with you, not for any boy, not even for my wonderful brother.

Too much work had left my husband, by 30, jaded and uninspired. He’d burned out — but I could reenchant things. I danced at restaurants when they played a song I liked. I turned grocery shopping into an adventure, pleased by what I provided. Ambitious, hungry, he needed someone smart enough to sustain his interest, but flexible enough in her habits to build them around his hours. I could. I do: read myself occupied, make myself free, materialize beside him when he calls for me. In exchange, I left a lucrative but deadening spreadsheet job to write full-time, without having to live like a writer. I learned to cook, a little, and decorate, somewhat poorly. Mostly I get to read, to walk central London and Miami and think in delicious circles, to work hard, when necessary, for free, and write stories for far less than minimum wage when I tally all the hours I take to write them.