105 Best Words To Start A Paragraph

The first words of a paragraph are crucial as they set the tone and inform the reader about the content that follows.

Known as the ‘topic’ sentence, the first sentence of the paragraph should clearly convey the paragraph’s main idea.

This article presents a comprehensive list of the best words to start a paragraph, be it the first, second, third, or concluding paragraph.

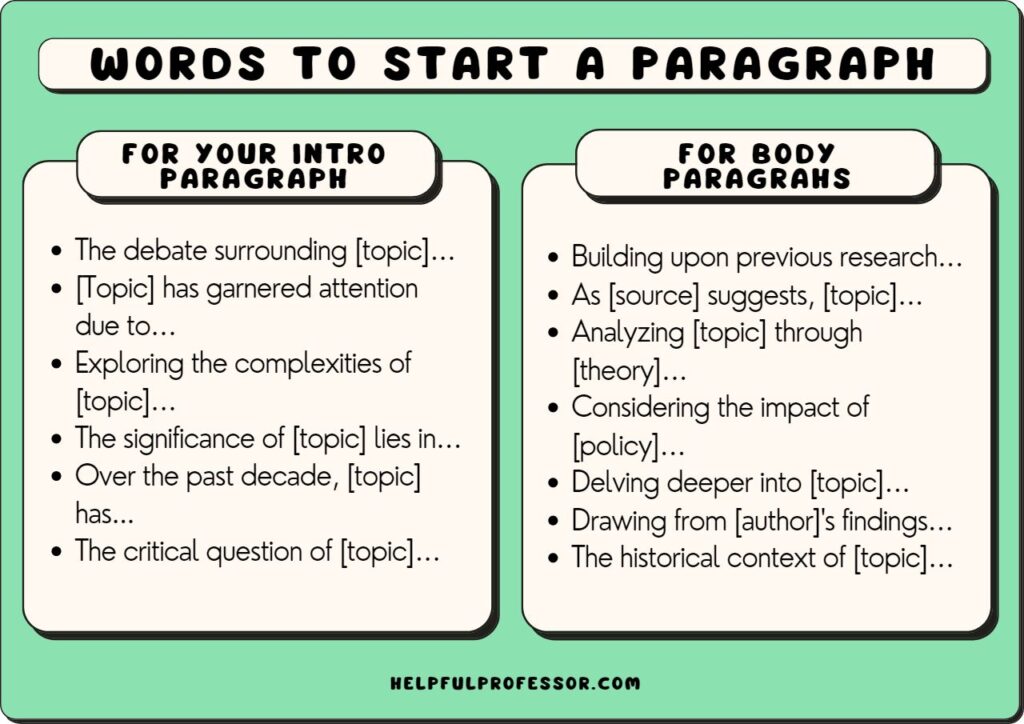

Words to Start an Introduction Paragraph

The words you choose for starting an essay should establish the context, importance, or conflict of your topic.

The purpose of an introduction is to provide the reader with a clear understanding of the topic, its significance, and the structure of the ensuing discussion or argument.

Students often struggle to think of ways to start introductions because they may feel overwhelmed by the need to effectively summarize and contextualize their topic, capture the reader’s interest, and provide a roadmap for the rest of the paper, all while trying to create a strong first impression.

Choose one of these example words to start an introduction to get yourself started:

- The debate surrounding [topic]…

- [Topic] has garnered attention due to…

- Exploring the complexities of [topic]…

- The significance of [topic] lies in…

- Over the past decade, [topic] has…

- The critical question of [topic]…

- As society grapples with [topic]…

- The rapidly evolving landscape of [topic]…

- A closer examination of [topic] reveals…

- The ongoing conversation around [topic]…

Don’t Miss my Article: 33 Words to Avoid in an Essay

Words to Start a Body Paragraph

The purpose of a body paragraph in an essay is to develop and support the main argument, presenting evidence, examples, and analysis that contribute to the overall thesis.

Students may struggle to think of ways to start body paragraphs because they need to find appropriate transition words or phrases that seamlessly connect the paragraphs, while also introducing a new idea or evidence that builds on the previous points.

This can be challenging, as students must carefully balance the need for continuity and logical flow with the introduction of fresh perspectives.

Try some of these paragraph starters if you’re stuck:

- Building upon previous research…

- As [source] suggests, [topic]…

- Analyzing [topic] through [theory]…

- Considering the impact of [policy]…

- Delving deeper into [topic]…

- Drawing from [author]’s findings…

- [Topic] intersects with [related topic]…

- Contrary to popular belief, [topic]…

- The historical context of [topic]…

- Addressing the challenges of [topic]…

Words to Start a Conclusion Paragraph

The conclusion paragraph wraps up your essay and leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

It should convincingly summarize your thesis and main points. For more tips on writing a compelling conclusion, consider the following examples of ways to say “in conclusion”:

- In summary, [topic] demonstrates…

- The evidence overwhelmingly suggests…

- Taking all factors into account…

- In light of the analysis, [topic]…

- Ultimately, [topic] plays a crucial role…

- In light of these findings…

- Weighing the pros and cons of [topic]…

- By synthesizing the key points…

- The interplay of factors in [topic]…

- [Topic] leaves us with important implications…

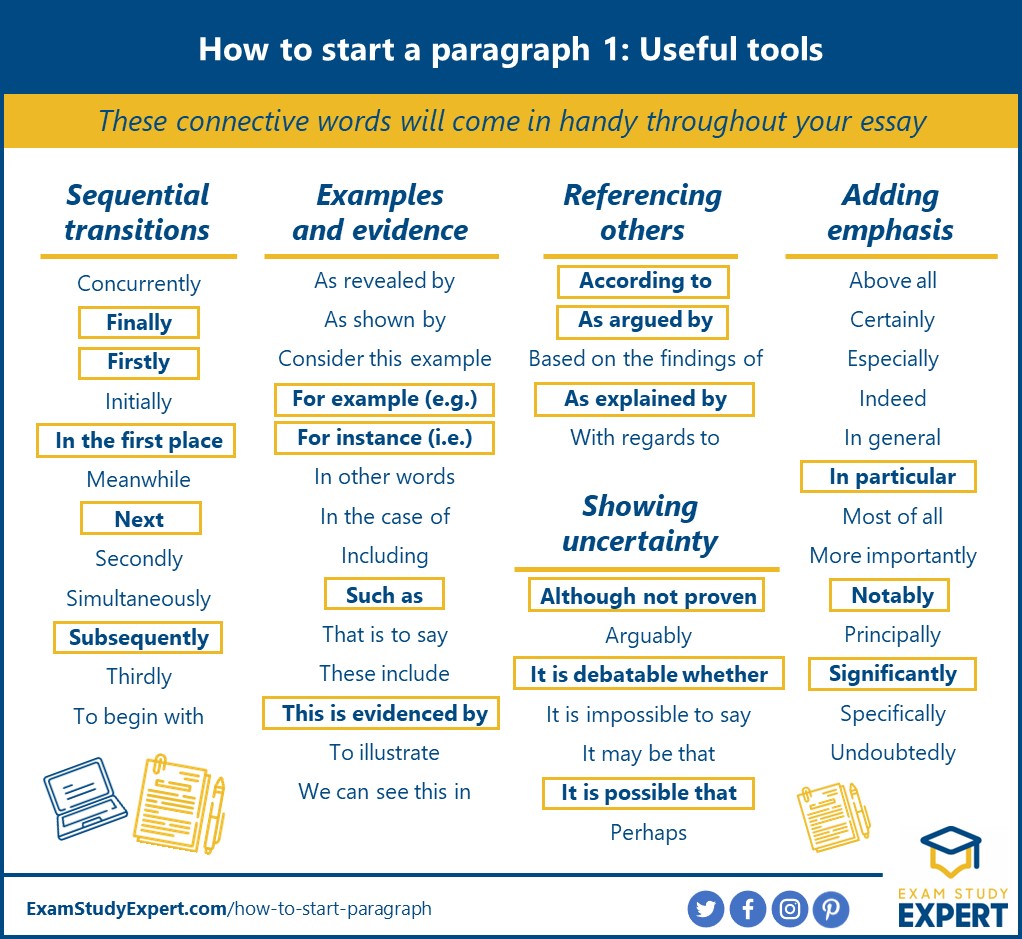

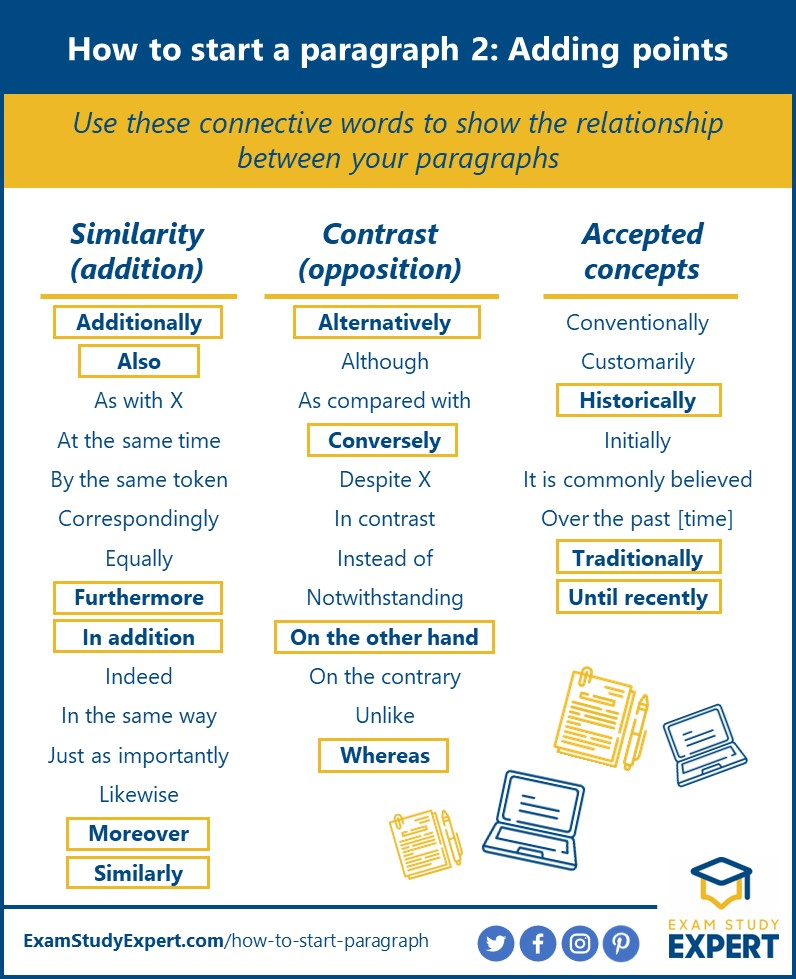

Complete List of Transition Words

Above, I’ve provided 30 different examples of phrases you can copy and paste to get started on your paragraphs.

Let’s finish strong with a comprehensive list of transition words you can mix and match to start any paragraph you want:

- Secondly, …

- In addition, …

- Furthermore, …

- Moreover, …

- On the other hand, …

- In contrast, …

- Conversely, …

- Despite this, …

- Nevertheless, …

- Although, …

- As a result, …

- Consequently, …

- Therefore, …

- Additionally, …

- Simultaneously, …

- Meanwhile, …

- In comparison, …

- Comparatively, …

- As previously mentioned, …

- For instance, …

- For example, …

- Specifically, …

- In particular, …

- Significantly, …

- Interestingly, …

- Surprisingly, …

- Importantly, …

- According to [source], …

- As [source] states, …

- As [source] suggests, …

- In the context of, …

- In light of, …

- Taking into consideration, …

- Given that, …

- Considering the fact that, …

- Bearing in mind, …

- To illustrate, …

- To demonstrate, …

- To clarify, …

- To put it simply, …

- In other words, …

- To reiterate, …

- As a matter of fact, …

- Undoubtedly, …

- Unquestionably, …

- Without a doubt, …

- It is worth noting that, …

- One could argue that, …

- It is essential to highlight, …

- It is important to emphasize, …

- It is crucial to mention, …

- When examining, …

- In terms of, …

- With regards to, …

- In relation to, …

- As a consequence, …

- As an illustration, …

- As evidence, …

- Based on [source], …

- Building upon, …

- By the same token, …

- In the same vein, …

- In support of this, …

- In line with, …

- To further support, …

- To substantiate, …

- To provide context, …

- To put this into perspective, …

Tip: Use Right-Branching Sentences to Start your Paragraphs

Sentences should have the key information front-loaded. This makes them easier to read. So, start your sentence with the key information!

To understand this, you need to understand two contrasting types of sentences:

- Left-branching sentences , also known as front-loaded sentences, begin with the main subject and verb, followed by modifiers, additional information, or clauses.

- Right-branching sentences , or back-loaded sentences, start with modifiers, introductory phrases, or clauses, leading to the main subject and verb later in the sentence.

In academic writing, left-branching or front-loaded sentences are generally considered easier to read and more authoritative.

This is because they present the core information—the subject and the verb—at the beginning, making it easier for readers to understand the main point of the sentence.

Front-loading also creates a clear and straightforward sentence structure, which is preferred in academic writing for its clarity and conciseness.

Right-branching or back-loaded sentences, with their more complex and sometimes convoluted structure, can be more challenging for readers to follow and may lead to confusion or misinterpretation.

Take these examples where I’ve highlighted the subject of the sentence in bold. Note that in the right-branching sentences, the topic is front-loaded.

- Right Branching: Researchers found a strong correlation between sleep and cognitive function after analyzing the data from various studies.

- Left-Branching: After analyzing the data from various studies, a strong correlation between sleep and cognitive function was found by researchers.

- The novel was filled with vivid imagery and thought-provoking themes , which captivated the audience from the very first chapter.

- Captivating the audience from the very first chapter, the novel was filled with vivid imagery and thought-provoking themes.

The words you choose to start a paragraph are crucial for setting the tone, establishing context, and ensuring a smooth flow throughout your essay.

By carefully selecting the best words for each type of paragraph, you can create a coherent, engaging, and persuasive piece of writing.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- ALL ARTICLES

- How To Study Effectively

- Motivation & Stress

- Smarter Study Habits

- Memorise Faster

- Ace The Exam

- Write Better Essays

- Easiest AP Classes Ranked

- Outsmart Your Exams

- Outsmart Your Studies

- Recommended Reads

- For Your Students: Revision Workshops

- For Your Teaching Staff: Memory Science CPD

- Our Research: The Revision Census

- All Courses & Resources

- For School Students and Their Parents

- For University Students

- For Professionals Taking Exams

- Study Smarter Network

- Testimonials

How To Start A Paragraph: 200+ Important Words And Phrases

by Kerri-Anne Edinburgh | Aug 3, 2022

There’s a lot to get right when you’re writing an essay. And a particularly important skill is knowing how to start a paragraph effectively. That first sentence counts!

Luckily for you, we’ve compiled HEAPS of advice, example phrases and top connective words to help you transition between paragraphs and guide your reader with ease.

So read on for a pick ’n’ mix of how to start a paragraph examples!

Paragraphs: the lowdown

So why exactly are paragraphs such an important tool for writing effectively ? Well:

- They’re an important part of keeping your reader captivated

- They help your reader to follow your argument or narrative

- And they keep your writing in easily digestible chunks of information!

And an important part of all that is nailing the start of your paragraphs . Honestly!

Start off strong and your reader will know exactly what you’re going to do next and how your information interrelates. Top marks here you come – and for the low, low cost of some clever vocab!

Start your paragraphs off weakly however, without setting up effective signposting and transitions , and they’ll get lost and ( horror !) might have to re-read your essay to make sense of it. Ugh.

What should your paragraphs contain?

If you’re writing an academic essay, there are a lot of popular conventions and guides about what a paragraph should include.

Academic writing guides favour well-developed paragraphs that are unified, coherent, contain a topic sentence, and provide adequate development of your idea. They should be long enough to fully discuss and analyse your idea and evidence.

And remember – you should ALWAYS start a new paragraph for each new idea or point .

You can read more about paragraph break guidelines in our helpful what is a paragraph article! If you’re wondering how long your paragraphs should be , check out our guideline article.

Paragraph structure (the PEEL method)

Academic paragraphs often follow a common structure , designed to guide your reader through your argument – although not all the time ! It goes like this:

- Start with a “topic sentence”

- Give 1-2 sentences of supporting evidence for (or against) your argument

- Next, write a sentence analysing this evidence with respect to your argument or topic sentence

- Finally, conclude by explaining the significance of this stance, or providing a transition to the next paragraph

(A quick definition: A “topic sentence” introduces the idea your paragraph will focus upon and makes summarising easy. It can occur anywhere but placing it at the start increases readability for your audience. )

One popular acronym for creating well-developed academic paragraphs is PEEL . This stands for Point, Evidence, Explanation, Link . Using this method makes it easy to remember what your paragraph should include.

- I.e. your point (the topic sentence), some evidence and analysis of how it supports your point, and a transitional link back to your essay question or forwards to your next paragraph.

NOTE : You shouldn’t start all your paragraphs the same way OR start every sentence in your paragraph with the same word – it’s distracting and won’t earn you good marks from your reader.

Free: Exam Success Cheat Sheet

My Top 6 Strategies To Study Smarter and Ace Your Exams

Privacy protected because life’s too short for spam. Unsubcribe anytime.

How to create clarity for your readers

Paragraphs are awesome tools for increasing clarity and readability in your writing. They provide visual markers for our eyes and box written content into easily digestible chunks.

But you still need to start them off strongly . Do this job well, and you can seamlessly guide your readers through the narrative or argument of your writing.

The first sentence of your paragraph is an important tool for creating that clarity . You can create links with the surrounding paragraphs and signal the purpose of this paragraph for your reader.

- Transitions show the links and relationships between the ideas you’re presenting: addition, contrast, sequential, conclusion, emphasis, example/citation

- Connective words help you to join together multiple paragraphs in a sequence

- Note: there is quite a lot of overlap in vocabulary! Some transitions are also great signposts etc.

Tip : Don’t overuse them! These techniques can make your writing sounds more professional and less like spoken language by smoothing over jarring jumps between topics. But using too many will make your writing stilted.

A common term that encompasses these three tools is “ sentence starter ”. They are typically set apart from the body of your sentence by a comma.

You can learn more about these key skills in our two helpful articles linked above – or explore a range of other writing skills advice, such as how to start an essay , structure an essay , and proofread an essay effectively!

Picking the right tone

It is important that the paragraph-starting phrases and connective words you choose complement the style of your writing and the conventions of the subject you are writing for .

For example, scientific papers usually have much clearer and expected structure and signposting conventions than arts and humanities papers.

If you’re unsure, it’s best to check some of the sources you’ve researched for your essay, explore the relevant academic style guide, or get help from a teacher – ask them for some examples!

Getting your grammar right

Grammatical conventions can be a minefield, but they’re worth remembering if you want to get top marks!

If you’re looking to increase the clarity of your writing and paragraphs, make sure you pick the right spot for your commas and colons .

For example, when you’re starting a new paragraph, many of the common signposting words and phrases require a comma. These include: however, therefore, moreover, what’s more, firstly, secondly, finally, likewise, for example, in general … (and more!).

These phrases should always be followed by a comma if it’s at the start of a sentence, or separated with a comma before and after like this if placed mid-sentence:

However, we cannot say for sure what happened here. We know, for example, that X claims to have lost the icon.

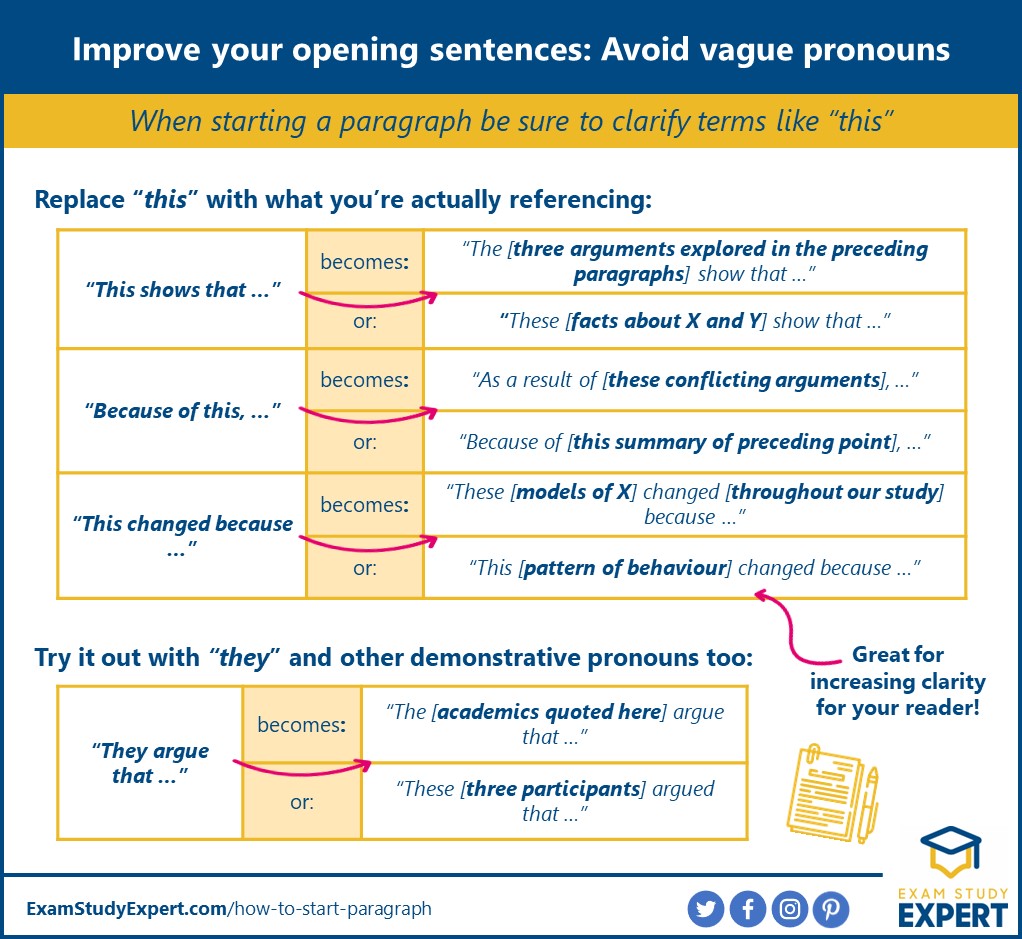

A word about “ this ” (a tip for really great writing)

As you start writing your paragraphs (and even sentences), you might be tempted to kick off with the word “ this” – as in the classic “ this shows that … ”.

But that’s not a great idea.

Why ? Academic essays aim should aim for maximum clarity, and “ this ” is just vague !

What’s important is that the connections that are clear to you , the writer (who is – hopefully – intimately familiar with your argument), are ALSO clear to your reader , who has probably never read your essay before.

Just imagine, your reader might be muttering “this what??” as they read, and then having to re-read the paragraph and the paragraph before to check … which is not ideal for getting good marks.

In complex documents (especially essays and theses) where a lot of information is presented at once, the points you’re referencing might be spread across several paragraphs of evidence and argument-building. So, unless your sentence/paragraph-starting “this” follows on immediately from the point it references, it’s best to try a different phrase.

And all it really takes is a little signposting and clarification to avoid the vagueness of “ this shows that ”. Ask yourself “ this WHAT shows that? ” And just point out what you’re referencing – and be obvious !

Here’s some examples:

You can also do a similar exercise with “ they ” and other demonstrative pronouns (that, these, those).

Specifying what your pronouns refer to will great help to increase the clarity of your (topic) sentences . And as an added bonus, your writing will also sound more sophisticated!

What type of paragraph are you starting?

When it comes to essay writing, there’s usually an expected structure: introduction, body (evidence and analysis) and conclusion .

With other genres of writing your paragraphs might not conform to such

Consider the structure of your paragraph. What do you want it to do? What is the topic? Do you want to open with your topic sentence?

How to start an introductory paragraph

Nailing the introduction of your essay is simultaneously one of the most important and hardest sections to write . A great introduction should set up your topic and explain why it’s significant.

One of the primary goals of an effective introduction is to clearly state your “ thesis statement ” (what your essay is about, and what you are setting out to achieve with your argument).

A popular (and easy) technique to start an introduction is to begin your first paragraph by immediately stating your thesis statement .

Here’s some examples of how to start a paragraph with your thesis statement:

- This paper discusses …

- In this paper, you will find …

- This essay argues that …

- This thesis will evaluate …

- This article will explore the complex socio-political factors that contributed to the decline of the Roman Empire between the reign of Constantine (312-337AD) and the fall of Rome in 476AD .

However, starting your introductory paragraph effectively is not all about immediately stating your thesis!

So head over to our great article on how to start an essay , for lots of more advice and examples on how to kick off your introductions and capture your reader’s attention with style!

How to start a body paragraph

Unless you’re writing an introduction or conclusion, you’ll be writing a “body paragraph”. Body paragraphs make up the majority of your essay, and should include all of your main points, data, evidence, analysis, deductions and arguments.

Each paragraph should have a particular purpose and be centred around one idea . Your body paragraphs might be analytical, evidential, persuasive, descriptive etc.

To help your reader make sense of the body of your essay, it’s important to guide them with signposts and transitions. These usually occur at the start of your paragraphs to demonstrate their relationship to preceding information.

However, that means there are LOTS of different techniques for starting your body paragraphs! So for 200+ words and phrases for effectively starting a body paragraph, simply keep reading!

How to start a concluding paragraph

Concluding paragraphs are a little different to other paragraphs because they shouldn’t be presenting new evidence or arguments . Instead, you’re aiming to draw your arguments together neatly, and tie up loose ends.

You might find them as part of a smaller sub-section within a longer academic dissertation or thesis. Or as part of the conclusion of your essay.

When starting your conclusion it’s always a great idea to let your reader know they’ve arrived by signposting its purpose . This is especially true if your essay doesn’t contain any headers!

Here are some examples of how to kick off your concluding paragraph:

- In conclusion, this paper has shown that …

- In summary, we have found that …

- A review of these analyses indicates that …

- To conclude, this essay has demonstrated that we must act immediately if we want to halt the drastic dwindling of our global bee population.

How to start a paragraph: 200+ top words and phrases for a winning first sentence

Choosing the best start for your paragraph is all about understanding the purpose of this paragraph within the wider context of the preceding (and following) paragraphs and your essay as a whole.

Where does it fit into the structure of your essay? Is it:

- Opening a new topic or theme?

- Providing explanations or descriptions?

- Continuing a list or sequence?

- Providing evidence?

- Presenting a different opinion or counter-argument?

- Beginning an analysis?

- Highlighting consequences?

- Drawing a conclusion?

It’s important to be direct in how you start each paragraph – especially if you’re struggling to get your point across!

The best way to craft a killer first sentence is to be clear on what you want it to do . We’ve covered 12 options below, packed with vocab and examples to get you started …

And don’t forget to consider when you should start a new paragraph , and how long you want your paragraphs to be . Where you place your paragraph breaks will have a big effect on the kind of starting sentence you need !

Finally – remember that the best time to craft effective opening sentences is after you’ve written your first draft and decided on your paragraph breaks! You should already have all your ideas arranged into a logical order.

Showing structure and presenting concepts

This first type of paragraphs are commonly found throughout your essay, whether you’re introducing your ideas, providing evidence and data, or presenting results.

There a lots of useful types of connective words and phrases to help you kick off your paragraphs with clarity:

Most notable are the sequential signposting words , which you can use throughout your essay to guide your reader through the steps of your argument, or a list of related evidence, for example.

If you’re looking for something a little more specific, read on for four sets of example academic phrases to use to start a paragraph!

1. Starting or continuing a sequence

One of the most important types of transitional phrases to help you start a paragraph is a sequential transition . These signposting transitions are great for academic arguments because they help you to present your points in order, without the reader getting lost along the way.

Sequential connectives and transitions create order within your narrative by highlighting the temporal relationship between your paragraphs. Think lists of events or evidence , or setting out the steps in your narrative .

You’ll often find them in combination with other paragraph-starting phrases ( have a look at the examples below to spot them !)

Why not try out some of these examples to help guide the readers of your essay?

- Before considering X, it is important to note that …

- Following on from Y, we should also consider …

- The first notion to discuss is …

- The next point to consider is …

- Thirdly, we know that Y is also an important feature of …

- As outlined in the previous paragraph, the next steps are to …

- Having considered X, it is also necessary to explore Y …

2. Providing evidence, examples or citations

Once you’ve made your claims or set out your ideas, it’s important to properly back them up. You’ll probably need to give evidence, quote experts and provide references throughout your essay .

If you’ve got more than one piece of evidence, it’s best to separate them out into individual paragraphs . Sequential signposting can be a helpful tool to help you and your reader keep track of your examples.

If your paragraph is all about giving evidence for a preceding statement, why not start with one of these phrases:

- For example, X often …

- This stance is clearly illustrated by …

- Consider the example of Y, which …

- This concept is well supported by …

If you want to quote or paraphrase a source or expert, a great way to start your paragraph is by introducing their views. You can also use phrases like these to help you clearly show their role in your essay:

- [Author], in particular, has argued that …

- According to [source], Y is heavily influenced by …

- [Source] for example, demonstrates the validity of this assertion by …

- This [counter-] argument is supported by evidence from X, which shows that …

Always remember to provide references for your sources in the manner most appropriate for your field ( i.e. footnotes, and author-date methods ).

3. Giving emphasis to your point

Not all points and paragraphs in an essay are made equal. It’s natural you’ll want to highlight ideas and evidence for your reader to make sure they’re persuaded by your argument !

So, if you want to give emphasis to what you’re about to discuss, be obvious ! In fact, you may need to be more direct than you think:

- This detail is significant because …

- Undoubtedly, this experience was …

- Certainly, there are ramifications for …

- The last chapters, in particular, are revealing of X …

4. Acknowledging uncertainty

In academia it’s common to find a little uncertainty in your evidence or results, or within the knowledge of your field . That’s true whether you’re a historian exploring artefacts from Ancient Greece, or a social scientist whose questionnaire results haven’t produced a clear answer.

Don’t hide from this uncertainty – it’s a great way to point ahead to future research that needs to be done. In fact, you might be doing it in your essay!

Why not try one of these examples to highlight the gaps in your academic field or experiment?

- Whether X is actually the case remains a matter of debate, as current explorations cannot …

- Although not proven, it is commonly understood that X …

- Whilst the likelihood of X is debateable …

- Given the age of the artifacts, it is impossible to say with accuracy whether Y …

- Although we cannot know for sure, the findings above suggest that …

- Untangling the causes of X is a complex matter and it is impossible to say for sure whether …

Showing the relationships between your points

As your essay progresses you will need to guide your reader through a succession of points, ideas and arguments by creating a narrative for them to follow. And important part of this task is the use of signposting to demonstrate the relationship between your paragraphs . Do they support each other? Do they present opposite sides of a debate?

Luckily there are lots of agreement , opposition and contextual connectives to help you increase your clarity:

Read on for four more sets of example academic phrases to help you present your ideas!

5. Making a new point

If there’s no connection between your new paragraph and the preceding material, you’re probably starting a new topic, point or idea.

That means it’s less likely ( although not impossible ) that you’ll need transitional phrases . However, it’s still important to signpost the purpose and position of this new paragraph clearly for your reader.

- We know that X …

- This section of the essay discusses …

- We should now turn to an exploration of Y …

- We should begin with an overview of the situation for X …

- Before exploring the two sides of the debate, it is important to consider …

You can find some great ideas and examples for starting a new topic in our how to start an essay article. Whilst they’re definitely applicable to introductions, these strategies can also work well for kicking off any new idea!

6. Presenting accepted concepts

If you’re aiming to take a new stance or question an accepted understanding with your essay, a great way to start a paragraph is by clearly setting out the concepts you want to challenge .

These phrases are also an effective way to establish the context of your essay within your field:

- It is commonly believed that …

- The accepted interpretation of X is …

- Until recently, it was thought that …

- Historically, X has been treated as a case of …

- Over the past two decades, scholars have approached X as an example of …

- The most common interpretation of Y is …

7. Adding similar points

Agreement connectives are an important tool in your arsenal for clearly indicating the continuation or positive relationship between similar ideas or evidence you’re presenting.

If you’re looking to continue your essay with a similar point, why not try one of these examples:

- Another aspect of X is …

- Another important point is …

- By the same token, Y should be explored with equal retrospection for …

- Moreover, an equally significant factor of X is …

- We should also consider …

- Proponents of Y frequently also suggested that …

8. Demonstrating contrast

In contrast, if you’re looking to present a counter-argument, opposite side of a debate, or critique of the ideas, evidence or results in your preceding paragraph(s), you’ll need to turn to contradiction and opposition connectives.

These phrases will help you to clearly link your paragraphs whilst setting them in contrast within your narrative:

- A contrary explanation is that …

- On the other side of this debate, X suggests that …

- Given this understanding of X, it is surprising that Y …

- On the other hand, critics of X point to …

- Despite these criticisms, proponents of X continue to …

- Whilst the discussion in the previous paragraph suggests X to be true, it fails to take into consideration Y …

Note : some paragraph-opening sentences can be modified using connective words to show either agreement or contrast! Here are some examples:

- It could also be said that X does [not] …

- It is [also] important to note that X … OR It is important, however, to note that X …

- There is [also/however], a further point to be considered …

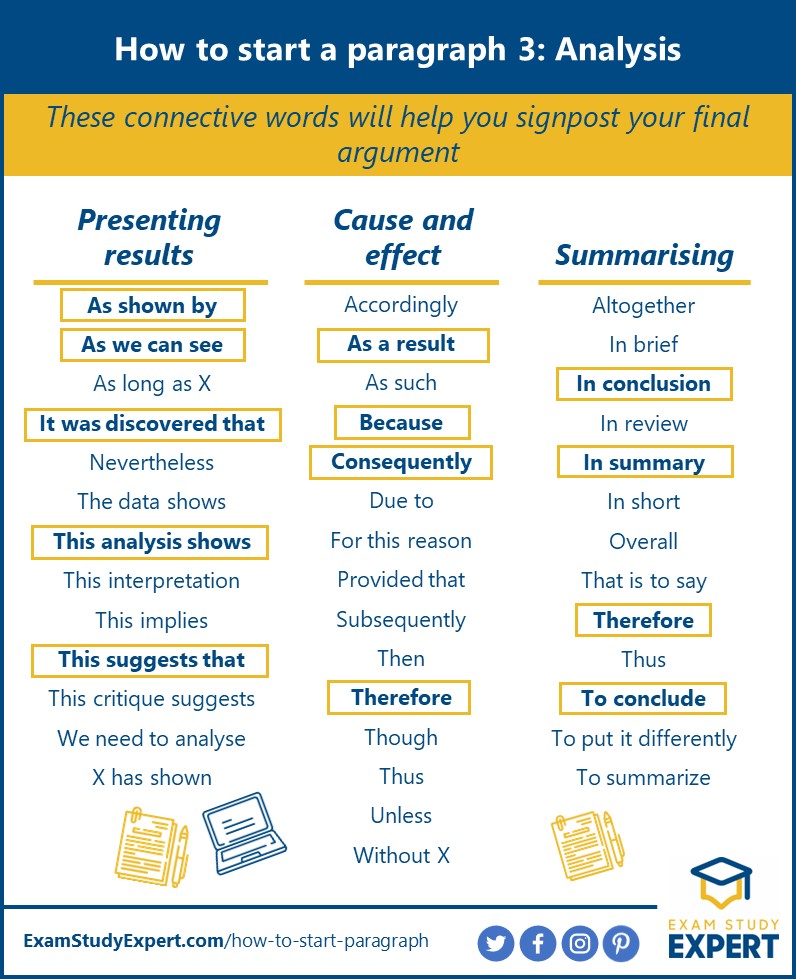

Presenting analyses, arguments and results

An important stage of any essay is the analysis – that’s when you bring your own arguments to the table, based on your data and results.

Signalling this clearly, therefore, is pretty important! Happily, there are plenty of connective words and phrases that can help you out:

Read on for four sets of example academic phrases to use to start your analysis, results and summary paragraphs!

9. Conducting an analysis and constructing your argument

Once you’ve set out your evidence or data, it’s time to point out the connections within them. Or to analyse how they support the argument you want to make.

With humanities essays it is common to analyse the impact of your evidence as you present it. In contrast, sciences essays often contain a dedicated analysis section after the data has been presented.

You’ll probably need several analytical paragraphs to address each of your points. So, a great way to get started is to dive straight in by signposting the connections you want to make in each one:

- Each of these arguments make an important contribution to X because …

- In order to fully understand Y, we need to analyse the findings from …

- Each model of X and Y changed throughout the experiment because …

- Exploring this dataset reveals that, in fact, X is not as common as hypothesised …

- Notwithstanding such limitations, this data still shows that …

- Of central concern to Y, therefore, is the evidence that …

- This interpretation of X is …

- This critique implies that …

- This approach is similar to that of Y, who, as we have seen above, argues that …

- The resulting graphs suggest that …

- Whilst conducting the survey, it was discovered that …

10. Presenting results

Having completed your analyses of any evidence (and hopefully persuaded your reader of your argument), you may need to present your results. This is especially relevant for essays that examine a specific dataset after a survey or experiment .

If you want to signpost this section of your essay clearly, start your paragraph with a phrase like these:

- The arguments presented above show that …

- In this last analysis, we can see that X has shown …

- As we have seen, the data gathered demonstrates that …

- As demonstrated above, our understanding of X primarily stems from …

11. Demonstrating cause and effect

When writing an academic essay you may often need to demonstrate the cause and effect relationship between your evidence or data, and your theories or results . Choosing the right connective phrases can be important for showing this relationship clearly to your reader.

Try one of these phrases to start your paragraph to clearly explain the consequences:

- As a consequence, X cannot be said to …

- Therefore, we can posit that …

- Provided that X is indeed true, it has been shown that Y …

- As such, it is necessary to note that …

- For this reason, the decision was made to …

- The evidence show that the primary cause of X was …

- As a result of Y, it was found that …

12. Summarising a topic or analysis

In general, summary paragraphs should not present any new evidence or arguments. Instead, they act as a reminder of the path your essay has taken so far.

Of course, these concluding paragraphs commonly occur at the end of an essay as part of your conclusion. However, they are also used to draw one point or stage of your argument to a close before the next begins .

Within a larger essay or dissertation, these interludes can be useful reminders for your reader as you transition between providing context, giving evidence, suggesting new approaches etc.

It’s worth noting that concluding your topic or analysis isn’t always the same as presenting results, although there can be some similarities in vocabulary.

Connect your arguments into summaries with clear linking phrases such as:

- Altogether, these arguments demonstrate that …

- Each of these arguments make an important contribution to our understanding of X …

- From this overview of X and Y, we can conclude that …

- We can therefore see that …

- It was hypothesised that X, however, as we have seen …

- Therefore, we can [clearly] see that …

Time to get writing your paragraphs!

And that’s it! You should now have a much-improved understanding of how to start a paragraph.

Whether you we’re worried about how to start your introductions or conclusions, or were wondering about specific types of body paragraphs, hopefully you’ve found what you need in the examples above .

If you need more writing advice to help you nail top marks for your essay, we’ve got a whole series of articles designed to improve your writing skills – perfect ! Have a read for top tips to for capturing easy marks 😊

You can learn:

- how to create effective paragraphs

- about the ideal length(s) for your paragraphs

- how to start an essay AND how to structure an essay

- the 70+ top connective words and phrases to improve your writing

- how to signpost your essay for top marks

- about improving clarity with easy proofreading tricks

Good luck completing your essay!

The Science Of Studying Smart

Download my free exam success cheat sheet: all my #1 must-know strategies to supercharge your learning today.

Your privacy protected. No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

- Latest Posts

- [2024] Are AP US Government & Politics and AP Comparative Government and Politics Hard or Easy? Difficulty Rated ‘Quite Easy’ (Real Student Reviews + Pass Data) - 5 Jan 2024

- [2024] Is AP Human Geography Hard or Easy? Difficulty Rated ‘Quite Easy’ (Real Student Reviews + Pass Data) - 5 Jan 2024

- [2024] Is AP Microeconomics Hard or Easy? Difficulty Rated ‘Quite Easy’ (Real Student Reviews + Pass Data) - 5 Jan 2024

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Read My Test-Taking Technique Book For More Marks In Exams

Top Picks: Recommended Reading From The Blog

How To Study Effectively : Ultimate Guide [READER FAVOURITE]

Exam Memorization Secrets

Inspirational Exam Quotes

Finding The Perfect Study Routine

Pomodoro Method : 9-Step Guide

Best Books About Studying

Listen To The Podcast

How To Start A New Paragraph: A How-To Guide and Top Tips

Here, we’ll explore what you need to know about how to start a new paragraph, from developing a topic sentence to using transition words smoothly.

We’ve all been there: working through a challenging topic and figuring out how to carry your reader through smoothly and coherently. You must understand how to create a stellar paragraph and how to transition from one paragraph to the next to help your reader follow your thoughts. If you know the thesis of your writing and you have a solid outline of what you’d like to say, it’s time to start building your body paragraphs, one by one.

You must understand both when and how to create a new paragraph. This will depend mainly on the type of writing you’re doing (more on that later). When you create a new paragraph, you must tell your reader what your paragraph will discuss (in the case of a body paragraph) without giving away everything you’re about to say. This can prove tricky, and if you find that you’re struggling to create topic sentences that don’t give away all of your details, you likely need to develop meatier ideas to support your general thesis.

Here, we’ll explore everything you need to know about how and when to start a new paragraph, how to use transition words to take your reader from one idea to the next flawlessly, and how to switch up your new paragraph style depending on whether you’re writing an academic or narrative piece.

When To Start A New Paragraph: Your How-To Guide

1. use new paragraphs for new topics, 2. create a topic sentence, 3. use transition words to move to a new idea, 4. know your formatting rules, 5. use quotation marks and dialogue to tell your story, starting a new paragraph: quick tips, 1. spacing between paragraphs, 2. paragraphs in different types of writing.

Readers generally don’t like big blocks of text , and it can be overwhelming for your reader to see large paragraphs without breaks to indicate a new idea. About five sentences per paragraph is a good rule of thumb to follow, but there’s no need for all of your paragraphs to follow this strictly.

Generally, each paragraph should introduce a new concept or idea. However, this can look different in academic and narrative writing. Academic writing generally starts a new paragraph each time you introduce a new point. In contrast, narrative writing uses a new paragraph to introduce small events that further the storyline or narrative concept.

If you glance over your text and find that you have a large block that could appear intimidating to your reader, find places to break up your writing. For example, develop large paragraphs into two or three ideas, or pare down your writing to be more concise if you want to stick with a single paragraph. You might also be interested in our list of paragraph writing topics .

A new paragraph should serve as a transition to a new topic or supporting point. Utilizing your outline, be sure that your paragraphs serve as a separate, clear point supporting your thesis. If you find that two or more of your paragraphs are very similar and rely on the same supporting points, see if you can condense your writing, making room for additional points that support your thesis.

When writing academically, you’ll want to begin each new paragraph with a topic sentence that introduces your supporting points. After you create your outline for your work, it’s also good to write the topic sentence for each paragraph. Many writers find that it’s easier to do this all at once instead of trying to come up with a topic sentence each time you transition to a new idea once your writing is started.

Your topic sentence should set the tone for what’s to come without giving away all of your supporting details. Therefore, keep your topic sentence short and to the point, and utilize the following sentences to support your topic sentence fully. Always keep in mind that each supporting point should ultimately relate to the thesis of your writing.

Using transition words can make it easier to move from one topic to the next. However, be careful that you don’t fall into the trap of constantly using the same transition words, as this can make your writing repetitive and cause your reader to lose interest. Reading your final work aloud can help you notice if you tend to use the same words repeatedly and can provide valuable insight into how you can replace repetition with new transition words.

Transition words that help you transition from the first paragraph to the next paragraph and so on fall into a few different categories: chronology (next, before, later, meanwhile), comparison (similarly, likewise), clarity (for instance, for example), continuation (furthermore, additionally), and conclusion (as a result, consequentially). Using transition words can help you separate paragraphs whether you’re writing a short story or a research paper, and can help your paragraph breaks read naturally.

When writing for a high school class, college class, or professional publication, you’ll likely have some formatting instructions that your teacher, professor, or editor will want you to follow when completing written work. For example, paragraph length, comma use, and thesis statement formatting may all have specific requirements for your class or publication. Be sure to carefully read your syllabus or talk with your editor to ensure that you’re following the requirements.

First-line indentation is typically used to start a new paragraph. Still, your professor or editor may ask that you use hanging indentation or spaces between paragraphs with no indentation. As long as a significant change in the text indicates that a new paragraph is beginning, your reader will quickly adjust to your indentation style.

If you’re writing a short story or another narrative piece that includes conversation, you’ll want to begin a new paragraph every time the speaker changes. This can result in short or one-sentence paragraphs, but don’t worry–this is the correct way to split paragraphs within dialogue so that your reader can easily follow your storyline.

Whether you choose to insert spaces between paragraphs is generally a matter of personal preference unless your professor or editor requests that you leave additional spacing. Whether you choose to place extra spaces between paragraphs or not, be sure to follow one of the most basic rules of academic and narrative writing: be consistent. If your research paper, short story, or another piece of writing has spacing between paragraphs in some spaces but not others, your work can become disorganized and tough for your reader to follow.

Many of your decisions regarding when to start a new paragraph will depend on the type of story or essay writing. In an academic writing piece, you’ll likely create new body paragraphs whenever you’re introducing a new idea or thought or developing a new point to support your thesis. In academic writing, paragraphs tend to be more uniform in length than in other types of writing.

In narrative writing, your paragraphs will likely look a little bit different. This is because narrative writing lends itself to greater creativity and more variation in paragraph sizes and styles. For example, you may use sentence-long paragraphs in dialogues throughout your narrative, while you may use longer paragraphs to introduce a new setting or character.

For more help with your writing, check out our essay writing tips !

Amanda has an M.S.Ed degree from the University of Pennsylvania in School and Mental Health Counseling and is a National Academy of Sports Medicine Certified Personal Trainer. She has experience writing magazine articles, newspaper articles, SEO-friendly web copy, and blog posts.

View all posts

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

On Paragraphs

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The purpose of this handout is to give some basic instruction and advice regarding the creation of understandable and coherent paragraphs.

What is a paragraph?

A paragraph is a collection of related sentences dealing with a single topic. Learning to write good paragraphs will help you as a writer stay on track during your drafting and revision stages. Good paragraphing also greatly assists your readers in following a piece of writing. You can have fantastic ideas, but if those ideas aren't presented in an organized fashion, you will lose your readers (and fail to achieve your goals in writing).

The Basic Rule: Keep one idea to one paragraph

The basic rule of thumb with paragraphing is to keep one idea to one paragraph. If you begin to transition into a new idea, it belongs in a new paragraph. There are some simple ways to tell if you are on the same topic or a new one. You can have one idea and several bits of supporting evidence within a single paragraph. You can also have several points in a single paragraph as long as they relate to the overall topic of the paragraph. If the single points start to get long, then perhaps elaborating on each of them and placing them in their own paragraphs is the route to go.

Elements of a paragraph

To be as effective as possible, a paragraph should contain each of the following: Unity, Coherence, A Topic Sentence, and Adequate Development. As you will see, all of these traits overlap. Using and adapting them to your individual purposes will help you construct effective paragraphs.

The entire paragraph should concern itself with a single focus. If it begins with one focus or major point of discussion, it should not end with another or wander within different ideas.

Coherence is the trait that makes the paragraph easily understandable to a reader. You can help create coherence in your paragraphs by creating logical bridges and verbal bridges.

Logical bridges

- The same idea of a topic is carried over from sentence to sentence

- Successive sentences can be constructed in parallel form

Verbal bridges

- Key words can be repeated in several sentences

- Synonymous words can be repeated in several sentences

- Pronouns can refer to nouns in previous sentences

- Transition words can be used to link ideas from different sentences

A topic sentence

A topic sentence is a sentence that indicates in a general way what idea or thesis the paragraph is going to deal with. Although not all paragraphs have clear-cut topic sentences, and despite the fact that topic sentences can occur anywhere in the paragraph (as the first sentence, the last sentence, or somewhere in the middle), an easy way to make sure your reader understands the topic of the paragraph is to put your topic sentence near the beginning of the paragraph. (This is a good general rule for less experienced writers, although it is not the only way to do it). Regardless of whether you include an explicit topic sentence or not, you should be able to easily summarize what the paragraph is about.

Adequate development

The topic (which is introduced by the topic sentence) should be discussed fully and adequately. Again, this varies from paragraph to paragraph, depending on the author's purpose, but writers should be wary of paragraphs that only have two or three sentences. It's a pretty good bet that the paragraph is not fully developed if it is that short.

Some methods to make sure your paragraph is well-developed:

- Use examples and illustrations

- Cite data (facts, statistics, evidence, details, and others)

- Examine testimony (what other people say such as quotes and paraphrases)

- Use an anecdote or story

- Define terms in the paragraph

- Compare and contrast

- Evaluate causes and reasons

- Examine effects and consequences

- Analyze the topic

- Describe the topic

- Offer a chronology of an event (time segments)

How do I know when to start a new paragraph?

You should start a new paragraph when:

- When you begin a new idea or point. New ideas should always start in new paragraphs. If you have an extended idea that spans multiple paragraphs, each new point within that idea should have its own paragraph.

- To contrast information or ideas. Separate paragraphs can serve to contrast sides in a debate, different points in an argument, or any other difference.

- When your readers need a pause. Breaks between paragraphs function as a short "break" for your readers—adding these in will help your writing be more readable. You would create a break if the paragraph becomes too long or the material is complex.

- When you are ending your introduction or starting your conclusion. Your introductory and concluding material should always be in a new paragraph. Many introductions and conclusions have multiple paragraphs depending on their content, length, and the writer's purpose.

Transitions and signposts

Two very important elements of paragraphing are signposts and transitions. Signposts are internal aids to assist readers; they usually consist of several sentences or a paragraph outlining what the article has covered and where the article will be going.

Transitions are usually one or several sentences that "transition" from one idea to the next. Transitions can be used at the end of most paragraphs to help the paragraphs flow one into the next.

How to Write a Paragraph in an Essay

#scribendiinc

Written by Scribendi

The deadline for your essay is looming, but you're still not sure how to write your essay paragraphs or how to structure them. If that's you, then you're in good hands.

After the content of your essay, the structure is the most important part. How you arrange your thoughts in an essay can either support your argument or confuse the reader. The difference comes down to your knowledge of how to write a paragraph to create structure and flow in an essay.

At its most basic level, an essay paragraph comprises the following elements: (1) a topic sentence, (2) sentences that develop and support the topic sentence, and (3) a concluding sentence.

Also, when writing a paragraph or essay , keep in mind that most essays follow the five-paragraph model. This model involves writing an introductory paragraph, three paragraphs of supporting arguments, and a conclusion paragraph.

In most cases, a paper of this length just won't cut it. However, remembering this formula can help you write key paragraphs in your essay, such as an introduction that states the main hypothesis, a body that supports this argument, and a conclusion that ties everything together.

Let's break down how to write a paragraph so you can get that essay written.

Writing a paragraph means grouping together sentences that focus on the same topic so that the important points are easy to understand. In the body of an essay, each paragraph functions as its own point or argument that backs up the essay's main hypothesis. Each paragraph also includes evidence that supports each argument made.

It helps to separate each paragraph idea in a quick essay outline before you start writing your paragraphs so you can organize your thoughts. It is also helpful to link each paragraph in a cohesive way that supports your hypothesis. For good paragraph writing to work, your readers will need to be able to clearly follow the ideas you're presenting throughout your essay.

Essay paragraphs are important for organizing topics and thoughts and for creating readability and flow. Readers often skip large blocks of writing in blog posts, articles, or essays. It can be confusing when there are no breaks between different ideas or when thoughts flow one into the next without any discernible pauses. Knowing how to write a paragraph to help break up your content and ideas is essential for avoiding this.

Elevate Your Writing with Professional Editing

Hire one of our expert editors , or get a free sample.

Writing a paragraph is easier when you follow a structure. An essay paragraph consists of around 250 words , with the sentence count varying from five to six or more, depending on the type of essay you're writing.

The structure of an essay paragraph includes the following:

- A topic sentence at the beginning of the paragraph that clearly states one idea

- Supporting sentences that explain the idea in the topic sentence and provide evidence to back up that idea

- A concluding sentence that links back to the original topic sentence idea and segues to the next paragraph

Following this basic structure will ensure that you never have to wonder how to write a paragraph and will keep your essay structure consistent.

What Is a Topic Sentence?

All good paragraph writing starts with a topic sentence. The topic sentence provides a brief summary of the content. In an essay's body, each paragraph begins with a topic sentence.

The topic sentence gives structure to a paragraph the same way a thesis gives structure to an essay. Both a thesis and a topic sentence state the main idea that drives the rest of the content. In the case of a paragraph, the topic sentence drives the rest of the paragraph content, and in the case of an essay, the thesis drives the rest of the essay content.

When writing a topic sentence, keep in mind that it should be

- The first sentence of your paragraph

- Specific, focusing on a specific area of your thesis statement

- The focus of your paragraph

There are two parts to every topic sentence: the topic, which is what the paragraph will be about, and the controlling idea, which is the paragraph's direction. For example, if your paragraph was about hamsters being great pets, that would be your topic, but your controlling idea might be that there are many reasons why hamsters are great pets.

A paragraph example with a good topic sentence would start out something like this:

Hamsters are great pets for many reasons. They don't require extensive training, so no time-consuming obedience courses are necessary. They are also relatively inexpensive to own when compared to dogs or cats because they're low-maintenance.

Examples of Effective Hooks

A paragraph in an essay should always use an effective hook. If you're hoping to grab the attention of your reader, it helps to start your paragraph with a compelling statement or question that will be of interest.

Here are a few examples to use for inspiration:

Most people would rather work to live than live to work, and the gig economy makes this possible.

How important is it for today's influencers to rely on Instagram?

Daily sugar intake has reached a staggering average of 25 teaspoons per person in the United States.

Supporting Sentences

Writing an essay paragraph is like building an effective and functional house. In the same way that each room has a purpose, each paragraph in your essay should have its own separate topic with supporting sentences . Paragraph writing can be simple if you think of it this way!

The goal of supporting sentences is to provide evidence validating each topic in your paragraph. Each sentence provides details to help your reader understand the paragraph's main idea.

If you have trouble coming up with supporting sentences to develop the main idea in your paragraph, try rephrasing your topic sentence as a question. For example, if you're writing about how all babies have three basic needs, ask, what are the three basic needs of all babies?

At the end of your supporting sentences, add a concluding sentence that ties everything to the main argument of your essay. Repeat this for each supporting argument, and you'll have mastered the concept of how to write a paragraph. Read on for a paragraph example with supporting sentences.

Supporting Sentence Examples

To get a feel for how to use supporting sentences in a paragraph in an essay, check out this basic example:

Babies have three basic needs. First, babies need food. Depending on their age, they'll drink formula for their first meals and graduate to soft baby food later. Second, they need shelter. Babies need a safe place to live. Third, they need support. They need someone loving to look out for them and take care of them.

How to Use Transitions

Knowing how to write a paragraph involves knowing how to use transitions .

Good essay paragraphs have transitions that help ideas flow clearly from one to the next. Given that your essay will include many different ideas and subtopics, your transitions will ensure that your information and ideas are well connected.

If you're not familiar with transitions, they are words or phrases that connect ideas. They signal a connection between your topic sentence and your supporting sentences, but they also help readers connect ideas between paragraphs.

At the beginning of a sentence, use a transition to segue into a new idea. At the beginning of each paragraph, use a transition to signal a new concept or idea that you will discuss.

However, try to avoid one-word transitions at the beginning of a paragraph, like "Since" or "While," because they don't usually provide enough information. Instead, try using transitional phrases between paragraphs (instead of words), such as "On the other hand" or "In addition to."

Examples of Transitions

Here are a few examples of transitions — both one-word transitions and transitional phrases — to use in the paragraphs of your essay:

- As a result

- For example

- By the same token

- Consequently

- In the meantime

- To summarize

- To conclude

- Undoubtedly

- Subsequently

Writing a paragraph in an essay can be simple if you understand basic paragraph structure. Additionally, it's helpful to keep in mind the structure of an essay and how each essay paragraph links together to form a fully developed argument or idea.

Creating an outline before you start writing your essay—which can also be described as a blueprint (to return to the metaphor of building a house)—is a great way to effectively arrange your topics, support your argument, and guide your writing.

Knowing how to write a paragraph is essential to communicating your thoughts and research, no matter the topic, in a way that is readable and coherent.

How Long Is a Paragraph?

An essay paragraph can vary in length depending on a variety of factors, such as the essay's type, topic, or requirements. Generally, essay paragraphs are three to five or more sentences, since each paragraph should have a fully developed idea with a beginning, middle, and end.

However, all essays are different, and there are no hard and fast rules that dictate paragraph length. So, here are some guidelines to follow while writing a paragraph:

- Stick to one idea per paragraph.

- Keep your paragraphs roughly the same length.

- Ensure that each page of your essay has 2 – 3 paragraphs.

- Combine shorter paragraphs into a larger one if the smaller paragraphs work together to express a single idea.

Overall, it's the paragraph writing itself that dictates a paragraph's length. Don't get too caught up in trying to reach a specific word count or number of sentences. Understanding this concept is key to knowing how to write a paragraph that conveys a clear and fully developed idea.

How Do I Know When to Start a New Paragraph?

A new essay paragraph will always signal a new point or idea. Before you think about starting a new paragraph, ask yourself whether you are about to discuss something new that you haven't brought up yet. If the answer is yes, it warrants a new paragraph.

The end of a paragraph functions as a break for your reader. If you've successfully developed and concluded an idea, you'll know that it's time to begin a new paragraph, especially if the material is long or complex.

Every essay should have an introductory paragraph and a conclusion paragraph. But as long as you keep in mind that good paragraph writing means starting off with a new idea each time, you're in a good position to know when a new paragraph should begin.

How Many Paragraphs Do I Need in My Essay?

The number of paragraphs you write in an essay will largely depend on the requirements of the essay. These requirements are usually dictated by an instructor.

For a short, 1-page essay, your instructor might require only three paragraphs. For a longer, 2- to 3-page essay, you might need five paragraphs. For longer essays, there could be up to seven to nine paragraphs. Any essay with more paragraphs than that is usually deemed a thesis or a research paper.

At a minimum, an essay will always have at least three paragraphs: an introductory paragraph, a body paragraph, and a conclusion paragraph. Depending on the required word or page count or the type of essay (argumentative, informative, etc.), your essay could have multiple paragraphs expanding on different points. An argumentative essay, for example, should have at least five paragraphs.

Therefore, the most important question to ask when deciding on your number of essay paragraphs is this: What does my professor expect from me?

Ask a Professional to Edit Your Essay

About the author.

Scribendi's in-house editors work with writers from all over the globe to perfect their writing. They know that no piece of writing is complete without a professional edit, and they love to see a good piece of writing transformed into a great one. Scribendi's in-house editors are unrivaled in both experience and education, having collectively edited millions of words and obtained numerous degrees. They love consuming caffeinated beverages, reading books of various genres, and relaxing in quiet, dimly lit spaces.

Have You Read?

"The Complete Beginner's Guide to Academic Writing"

Related Posts

Essay Writing Help

How to Improve Essay Writing Skills

How to Write an Introduction to an Essay

Upload your file(s) so we can calculate your word count, or enter your word count manually.

We will also recommend a service based on the file(s) you upload.

English is not my first language. I need English editing and proofreading so that I sound like a native speaker.

I need to have my journal article, dissertation, or term paper edited and proofread, or I need help with an admissions essay or proposal.

I have a novel, manuscript, play, or ebook. I need editing, copy editing, proofreading, a critique of my work, or a query package.

I need editing and proofreading for my white papers, reports, manuals, press releases, marketing materials, and other business documents.

I need to have my essay, project, assignment, or term paper edited and proofread.

I want to sound professional and to get hired. I have a resume, letter, email, or personal document that I need to have edited and proofread.

Prices include your personal % discount.

Prices include % sales tax ( ).

How to Write an Effective Paragraph

Paragraphs are meant to make reading a text easier. When a writer composes for school or work purposes, paragraphs help promote the brevity, clarity, and simplicity expected of formal writing. Each new paragraph signals a pause in thought and a change in topic, directing readers to anticipate what is to follow or allowing them a moment to digest the material in the preceding paragraph. Reasons to start a new paragraph include

- beginning a new idea,

- emphasizing a particular point,

- changing speakers in dialogue,

- allowing readers to pause, and

- breaking up lengthy text, usually moving to a subtopic.

Once a writer is satisfied with their paragraph content, they take their readers into consideration. They revise and edit to make their paragraphs both engaging and easy to read. Key considerations for revising and editing paragraphs are length, variety, clarity, and transitions.

PARAGRAPH LENGTH

Effective paragraphs vary in length. Paragraph lengths should invite readers in, neither seeming too daunting nor appearing incomplete. Paragraphs of more than one double-spaced page will appear too dense and too long to be inviting. However, short paragraphs can appear choppy and undeveloped. In fact, one-sentence paragraphs are rarely effective. Not only can a one-sentence paragraph seem abrupt, but it can also leave readers puzzled. A sentence that makes a point about a topic will typically need at least one or even more sentences to illustrate and explain that point.

For complex concepts such as those in persuasive essays that demand detailed explanation and supporting evidence, longer paragraphs are necessary. However, when narrating an example or explaining a process, shorter paragraphs will best emphasize the order of ideas or importance of each step.

SENTENCE VARIETY

Most people have experienced a lecture or presentation given by someone who talks in a monotone. It probably puts the audience to sleep. The equivalent of such monotony in writing occurs when sentences have the same structure and the same length. Once the content of the writing is solid, an experienced writer revises, paying attention to sentence variety. Strong paragraphs contain a variety of sentence structures, sentence types, sentence openings, and sentence lengths.

Sentence Structures

One method for gaining sentence variety is to use all of the below sentence structures in your paper.

1. Simple Sentence = one independent clause with no subordinate clause

Music is life itself (Louis Armstrong).

Independent clause

2. Compound Sentence = two or more independent clauses with no subordinate clauses

One arrow is easily broken , but a bundle of ten can’t be broken .

independent clause, [conjunction] independent clause

3. Complex Sentence = one independent clause with one or more subordinate clauses

If you scatter thorns , don’t go barefoot .

subordinate clause, independent clause

4. Compound-Complex Sentence = at least two independent clauses and at least one subordinate clause

Tell me what you eat , and I will tell you [what you are] .

independent clause, [conjunction] independent clause [subordinate clause]

Sentence Types

Another method for adding variety is to use different sentence types:

- Declarative = makes a statement: The echo always has the last word.

- Imperative = makes a demand: Love your neighbor.

- Interrogative = asks a question: Are second thoughts always wisest?

- Exclamatory = makes an exclamation: I want to wash the flag, not burn it!

Declarative sentences will naturally be used the most in academic writing. But imperative and interrogative sentences can make the content stronger and add sentence variety. Exclamatory sentences are used rarely in academic writing and professional writing but can occasionally be effective, depending on context, audience, and purpose.

Sentence Openings

Another way to add sentence variety is with sentence openings. Many writers fall into a pattern of starting sentences the same way, generally with the subject of the sentence. Here is a sample of what can be done with the simple sentence “John broke the window.” The different openings not only add variety, but also create more interesting content.

- Subject : John broke the window.

- Conjunction: But John broke the window.

- Adverb (answers how, when, why): Afterwards , John broke the window.

- Adverb Clause: While hitting a fly ball in the vacant field, John broke the window.

- Expletive (there, it): There is the window John broke.

- Correlative Conjunction: Either John broke the window with the fly ball or he did not.

- Prepositional Phrase: During the game, John broke the window.

- Infinitive Phrase: To complete the destructiveness of the baseball game, John broke the window.

- Passive Voice: The window was broken by John.

- Participle Phrase: Testing his father’s patience, John broke the window.

- Subordinate Clause: Although John hit a home run, the price was a broken window.

- Inverted Word Order: The window John broke.

Inverted word order should not be overused. But occasional use at an important point where the writer wants to grab the reader’s attention can add surprise and drama as in the following example:

o Normal Word Order: The Christmas treats, the bright, beribboned presents, and the charitable love of the season are all gone.

o Inverted Word Order: Gone are the Christmas treats, the bright, beribboned presents, and the charitable love of the season.

Varied Sentence Lengths

A final way to vary sentences is with length. Experienced writers strive to compose sentences that are short, medium, and long in length. They can check sentence length by beginning each sentence of a paragraph on a separate line, so they can scan the lengths. Here is an example:

- Kirilov’s home is described as dark, in part because of his son’s sickness and death, which occurred barely five minutes before Aboguin rings the doctor’s doorbell.

- The entry is dark and the lamp in his drawing room is unlighted, allowing the twilight and the dark September evening to fill the room, relieved only by a light in the adjoining study that lights his books and a big lamp in the dead boy’s bedroom.

- The darkness extends to Kirilov himself.

- Chekhov describes him as having a prematurely gray beard and skin with a pale gray hue.

- His hands are stained black with carbolic acid, marking him as a laborer.

- His dark home and gray appearance exemplify the grayness and monotony of life that characterize his recent loss and years of poverty.

The varied lengths are easy to see at a glance. If the writer decides the paper’s sentences need to be more varied in length, much can be done. For example, clauses can be converted to phrases: Sentence one in the paragraph above could be changed to the following:

- Kirilov’s home is described as dark, in part because of his son’s sickness and death, occurring barely five minutes before.

Sentences can be combined. Sentences three and four above could become the following:

- The darkness extends to Kirilov himself as Chekhov describes him as having a prematurely graybeard and skin with a pale gray hue.

Long sentences can be divided. Sentence two above could become the following:

- The entry is dark, and the lamp in his drawing room is unlighted, allowing the twilight and the dark September evening to fill the room. The darkness is relieved only by a light in the adjoining study that lights his books and a big lamp in the dead boy’s bedroom.

Phrases can become one or two words. Sentence four above could become the following:

- Chekhov describes him as prematurely gray.

These changes do not necessarily make the sentence better, but they serve as good examples of what can be done to change sentence length and add sentence variety.

SENTENCE CLARITY

Sentence clarity requires grammatical correctness; however, mixed constructions, faulty predication, and inconsistent or incomplete comparisons are common causes of garbled sentences that writers must check for when revising and editing.

Mixed Construction

A mixed construction occurs when a sentence begins with one grammatical pattern and concludes with a different grammatical pattern, as if the writer started writing a sentence, was interrupted, and then finished it without referring back to the beginning.

- The fact that our room was hot we opened the window between our beds.

- By not prosecuting marijuana possession as vigorously as crack possession encourages marijuana users to think they can ignore the law.

- Because of the European discovery of America became a profitable colony for Britain.

An easy way to identify mixed constructions is to read a paper backwards, one sentence at a time so that each sentence is isolated.

Faulty Predication

Faulty predication occurs when the predicate of a sentence does not logically complete its subject. Most often, faulty predication involves the verb “to be.” We know that “to be” verbs act like equal signs between the subject and predicate:

- The piano player is skilled.

However, if the predicate is logically inconsistent with the subject, the sentence will confuse readers.

- The power of a skilled piano player is keenly aware of being able to raise strong emotions in listeners. [Can the power of a piano player be keenly aware?]

- Listeners are keenly aware of the power a skilled piano player has to raise strong emotions in listeners. [Now it is the listeners who are keenly aware.]

Inconsistent or Incomplete Comparisons

When making comparisons, the writer must make sure they are consistent and complete.

- Inconsistent: Brownlee’s business proposal is better than Summers. [Brownlee’s business proposal is being compared to Summers, a person.]

- Consistent: Brownlee’s business proposal is better than the one by Summers.

- Incomplete: I was ashamed because my background was so different. [Different from what?]

- Complete: I was ashamed because my background was so different from that of my new co-workers.

Inconsistent and incomplete comparisons are common in speech. Context, facial expression, and body language supply the missing information. But in formal writing, care must be taken to compose clear sentences.

TRANSITIONS

Transitions are one of the methods used to make paragraphs flow smoothly. Transitions are connectors or bridges between thoughts. When the reader knows the relationship between concepts or sentences, the thoughts flow smoothly and the paragraph is easier to read. Writers use both transition words and transition sentences.

Transition Words and Phrases

Transitional expressions work well between sentences when the relationship between sentences is not already evident. Transitional expressions can also be used between paragraphs so that the content of one paragraph leads logically into the next paragraph. In these cases, the transition highlights the relationship that is already clear. If someone reads the word “however,” they know that the next thought will be in contrast to the previous one. The word acts as a bridge explaining the relationship between the two thoughts. If someone reads the word “meanwhile,” they know that the next event is happening at the same time as the event discussed previously. The word explains the simultaneous relationship between the two events.

Example of Transition Words and Expressions

- To Indicate Time Order : in the past, before, earlier, preceding, recently, presently, currently, now

- To Provide an Example : for example, for instance, to illustrate, specifically, in particular, namely, in other words

- To Indicate Results : as a result, consequently, because of, for this reason, since, therefore, thus, accordingly

- To Concede : although, even though, admittedly, granted, while it is true, of course

- To Compare : in comparison, in like manner, in much the same way, likewise

- To Contrast : and yet, but, despite, nevertheless, nonetheless, notwithstanding, however, contrary to, on the other hand

- To Emphasize : above all, undoubtedly, most importantly, moreover, furthermore, without question

Transition Sentences

For more sophisticated transitions between paragraphs, writers use whole sentences. Types of transition sentences include the following:

- Echo Transition : The writer echoes a word, phrase, or idea from the last sentence of one paragraph in the first sentence of the next paragraph. Here is an example:

. . . Throughout the story, the husband’s word is considered law, and the wife barely dares to question it.

This unequal marriage fits perfectly into the historical period of the setting. . .

The italicized phrase echoes the idea in the previous paragraph, providing a bridge to the next paragraph.

- Key Word Transition : The writer repeats key words from one paragraph to the next. Here is an example:

. . . Shirley Jackson shows the uselessness of the lottery and the selfishness of human nature through Mr. Warner’s ignorance.

This selfishness of human nature is shown very clearly through Tessie in the story….

The repetition of key words demonstrates the relationship between the ideas in the two paragraphs.

- Look Backward and Forward : In one or two sentences, the text looks back at the ideas of the preceding paragraph and then looks forward to the ideas in the next paragraph.