Home — Essay Samples — History — Historical Criticism

Essays on Historical Criticism

Book thief sparknotes, historical criticism of "theft" by katherine anne porter, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Analysis of John Dominic Crossan's Book "Jesus: a Revolutionary Biography"

Othello by william shakespeare: character analysis, historical inaccuracy in the film gladiator, evaluation of historical accuracy in the braveheart, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Historical Accuracy of The Depiction of The 1990s in Looking for Alibrandi

Understanding of literature due to several approaches, evaluation of historical accuracy of the play hamilton, relevant topics.

- Hammurabi's Code

- Historiography

- Declaration of Independence

- American Revolution

- Great Depression

- Civil Rights Movement

- Manifest Destiny

- Cesar Chavez

- Hurricane Katrina

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Bibliography

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Philosophy › Historical Criticism

Historical Criticism

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on November 13, 2020 • ( 0 )

Historical theory and criticism embraces not only the theory and practice of literary historiographical representation but also other types of criticism that, often without acknowledgment, presuppose a historical ground or adopt historical methods in an ad hoc fashion. Very frequently, what is called literary criticism, particularly as it was institutionalized in the nineteenth century and even up to the late twentieth century, is based on historical principles.

Aristotle commented on the origins of tragedy, Quintilian reviewed the history of oratory, and bibliographies and collections of books studied together existed in antiquity and in the Middle Ages. Yet a genuine literary or art history, finding continuity and change amid documents and data, was not possible until the growth of the historical sense in the Renaissance. Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists (1550), comprising over 150 biographies, towers above all Renaissance literary and art histories. It was no mere grouping of separate lives but an attempt to trace the progress of Italian art from Giotto to the age of Michelangelo, to establish the concept of a period (three of them for 1300-1550), and to distinguish one period from another. Despite Vasari’s example, the art history and literary history of the next two centuries were dominated by antiquarianism and chronologism.

The theory of modern historical criticism begins in the Enlightenment. Responding to the scientific revolution of the previous century, Giambattista Vico divided mathematics and physics from the humanities and what are now called the social sciences and stipulated by his verum factum principle that one can fully know only what one has made, namely, the products of language, civil institutions, and culture. In his New Science (1725) he argued that the closest knowledge of a thing lay in the study of its origins; outlined a concept of poetic logic by which one could grasp imaginatively the myths, customs, and fables of primitive cultures; and presented a theory of cultural development. Neither theology, philosophy, nor mathematics was the science of sciences: it was the “new science”—”history”—understood in Vichian terms. In his History of Ancient Art (1764) Johann Joachim Winckelmann studied “the origin, growth, change, and decline of classical art together with the different styles of various nations, times, and artists,” including Etruscan, Oriental, Greek, and Roman art. Though he surveyed “outward conditions,” he undermined his relativizing initiative in maintaining the neoclassical doctrine that Greek art is timeless and normative and in urging its imitation. Nevertheless, his definition of Greek art in terms of “noble simplicity and tranquil grandeur” distinguished the classical ideal from postclassical tendencies, thereby establishing one of the two polarities and prompting the need to define the other (quoted in Winckelmann, Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture , 1987, xvii, 33).

In England, the Homeric studies of Thomas Blackwell (1735) and Robert Wood (1769) sought to link the epic poet to the character of the times. Blackwell enumerated “a concource of natural causes” that “conspired to produce and cultivate that mighty genius”: climate, geography, phase of cultural and linguistic development, Homer’s “being born poor, and living a stroling indigent Bard” (quoted in Mayo 50). In his pioneering History of English Poetry (1774-81) Thomas Warton explored the changing fortunes of various genres from the Middle Ages to the sixteenth century in terms of primitive and sophisticated art. Samuel Johnson joined the narrative of a life, a critical analysis of the works, and a study of the poet’s mind and character in his Lives of the Poets (1779- 81), virtually creating the genre of literary biography. He also pondered writing a “History of Criticism . .. from Aristotle to the present age” (Walter Jackson Bate, Samuel Johnson, 1977, 532).

Although Johann Gottfried von Herder was not willing to abandon artistic universality or German nationalism, he was too much of a historical relativist to take the art of any one society as normative. He criticized Winckelmann for valuing Greek over Egyptian art when he did not take into account their vast cultural and environmental differences. Herder showed his appreciation for these difficulties in his treatment of the Arab influence on Provençal poetry. His historical method posited two basic assumptions: “that the literary standards of one nation cannot apply directly to the work of another” and “that in the same nation standards must vary from period to period” (Miller 7). In his Ideas on the Philosophy of History (1784-91) he drew analogies from organic nature and pressed for the investigation of physical, social, and moral contexts to depict the progressive development of national character. In his view, literature ( Volkspoesie ) is the product of an entire people striving to express itself, and though he himself believed that each nation contributed to the overarching ideal of universal art, his writings were subsequently appropriated to support national literary history. In response to Winckelmann, he located the beginnings of the modern artistic spirit in the Middle Ages and considered the Roman (a mixed genre of broad, variegated content, including philosophy) to be the quintessentially modern genre.

Both the theory and the practice of literary history expanded in the wake of the French Revolution and German idealist philosophy. G. W. F. Hegel defined Geist as the collective energies of mind and feeling that produce the Zeitgeist, or spirit of the age, and he conceived of the history of art in three movements illustrating the dialectical progression of Geist : oriental, in which matter over which the idea and its embodiment are in perfect equilibrium; and Romantic or modern, in which the idea, freed from subjugation, cannot be adequately expressed in material form. August von Schlegel’s Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature (1809-11) developed Herder’s notion of the two categories of Western art, classical and postclassical (conditioned by Christianity and mainly “northern”) for which the word “Romantic” became the preferred term. His goal was to trace “the origin and spirit of the romantic in the history of art.” In his formulation, the classic represents formal unity, natural harmony, objectivity, distinctness, the finite, and “enjoyment”; the Romantic signifies incompleteness, subjectivity, “internal discord,” indistinctness, infinity, and “desire,” idealism and melancholy being the chief characteristics of Romantic poetry (25-27). The Romantic outlook on historical writing stressed the organic nature of change, process rather than mere product. Germaine de Staël adopted the distinction between classic and Romantic in her influential De L’Allemagne (1810, On Germany ).

Michel Foucault/ New Criterion

Friedrich von Schlegel set these historical categories on firmer theoretical ground. His sociologically oriented Lectures on the History of Literature (1815) examine not only European languages but also Hebrew, Persian, and Sanskrit, thereby extending the range of comparative literary studies. Yet he advised against comparing poems of different ages and countries, preferring that they be compared with other works produced in their own time and country. He called for the study of the “national recollections” of a whole people, which are most fully revealed in literature, broadly defined and including poetry, fiction, philosophy, history, “eloquence and wit.” Literature contains “the epitome of all intellectual capabilities and progressive improvements of mankind.” For Schlegel, the modern spirit in literature reveals itself best in the novel combining the poetic and the prosaic; philosophy, criticism, and inspiration; and irony. Beyond the histories of individual nations, he applied his organicist principle to the effect that literature is “a great, completely coherent and evenly organized whole, comprehending in its unity many worlds of art and itself forming a peculiar work of art” (7-10). This is the Romantic ideal of totality, as in Hegel’s formulation that the true is the whole, and Schlegel heralded a “universal progressive poetry” (quoted in Wellek, Discriminations 29). “The national consciousness, expressing itself in works of narrative and illustration, is History .” The stage was set for the major achievements of nineteenth-century narrative literary history.

The unifying ideal of these works—the essence of nineteenth-century historicism—was that the key to reality and truth lay in the continuous unfolding of history. They were founded on a few key organizational premises: “an initial situation from which the change proceeds”; “a final situation in which the first situation eventuates and which contrasts with the first in kind, quality, or amount”; “a continuing matter which undergoes change”; and “a moving cause, or convergence of moving causes” (Crane 33). The subject matter might be an idea (the sublime), a technique (English prose rhythm), a tradition (that of “wit”), a school (the Pléiade), a reputation (Ossian), a genre or subgenre, the “mind” of a nation or race. The principal subject was treated like a hero in a plot (birth, struggle to prominence, defeat of an older generation); emplotments were of three basic types, “rise, decline, and rise and decline” (Perkins, Is Literary 39). The works as a whole were characterized by a strong teleological drive. Representative narrative histories of the national stamp are Georg Gottfried Gervinus’s History of the Poetic National Literature of the Germans (1835-42), Julian Schmidt’s History of German Literature since the Death of Lessing (1861), Francesco de Sanctis ‘s History of Italian Literature (1870-71), Wilhelm Scherer’s History of German Literature (1883), and Gustave Lanson’s Histoire de la littérature française (1894). Taking a “scientific view,” Georg Brandes considered literary criticism to be “the history of the soul,” and his supranational and comparatist Main Currents in Nineteenth Century Literature (1872-90) traces “the outlines of a psychology” of the period 1800-1850, its thesis being “the gradual fading away and disappearance of the ideas and feelings of the preceding century, and the return of the idea of progress” ( Main i:vii).

In the mid-nineteenth century literary historians began searching among the social and natural sciences for models and analogies, for instance, Comtean positivism, John Stuart Mill’s atomistic psychology, or Charles Darwin’s evolutionary biology. Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve borrowed scientific analogies of a general nature in his historical and biographical criticism. His subtle, probing works cannot be pigeonholed. “I analyze, I botanize, I am a naturalist of minds,” he said (quoted in Bate 490), and he counseled that “one cannot take too many methods or hints to know a man; he is another thing than pure spirit” (Bate 499). For Victorian literary history René Wellek proposes four main categories: the scientific and static, the scientific and dynamic, the idealistic and static, and the idealistic and dynamic ( Discriminations 153). Henry Hallam’s Introduction to the Literature of Europe (1837-39) is atomistic and cyclical, starting at 1500 and beginning again at 50-year intervals. In his History of English Literature (1863-64) Hippolyte Tain e set forth a deterministic explanation of literary works with three principal causes (race, moment, and milieu); these are the “externals,” which lead to a center, the “genuine man,” “that mass of faculties and feelings which are the inner man” ( History 1:7). His dictum “Vice and virtue are products, like vitriol and sugar” (1:11) is a chemical analogy. He chose England as if he were a scientist preparing an experiment: England had a long and continuous tradition that could be traced developmentally and up to the present, in vivo as well as in vitro. Other national literatures were rejected for one reason or another. Latin literature had too weak a start, Germany had a two-hundred-year interruption, Italy and Spain declined after the seventeenth century. A Frenchman might lack the requisite objectivity in writing the history of his own nation. The Darwinian influence can be seen in the work of Taine’s pupil Ferdinand Brunetiére. In L’Évolution des genres dans l’histoire de la littérature (1890) he treated a literary genre as if it were a genus of nature, noting its origin, rise, and fall and situating a work of art at its appropriate place on the curve.

Some literary historians produced works in several categories. Leslie Stephen’s History of English Thought in the Eighteenth Century (1876) adapts an idealist viewpoint to describe the rise of agnosticism, while his English Literature and Society in the Eighteenth Century ( 1904) is deterministic, sociological, and “scientific”: literature is the “noise of the wheels of history” (quoted in Wellek, Discriminations 155). An example of the idealistic and dynamic category is W. J. Courthope’s six-volume History of English Poetry (1895-1910), which finds “the unity of the subject precisely where the political historian looks for it, namely, in the life of the nation as a whole,” and which uses “the facts of political and social history as keys to the poet’s meaning” (i:xv). Courthope wanted to uncover the “almost imperceptible gradations” of linguistic and metrical advance: “By this means the transition of imagination from mediaeval to modern times will appear much less abrupt and mysterious than we have been accustomed to consider it” (i:xxii). George Saintsbury’s Short History of English Literature (1898), History of Criticism (1906), and History of English Prose Rhythm (1912) are at once erudite and impressionistic, and occasionally idiosyncratic in their judgments. Obviously many literary histories were eclectic in their methodology and fell between categories.

New Historicism

Among the shortcomings of nineteenth-century narrative histories were the imbalance between the space given to the individual work of art and the background materials required to “explain” it. Too little attention was given to analysis of the work itself and to questions of literary merit. Often enough, works were submerged by their contexts and causes, which were in a sense infinite (philological, psychological, social, moral, economic, political). David Masson’s seven-volume “life and times” biography of Milton (1881) was heavily weighted toward the times; in his review James Russell Lowell complained that Milton had been reduced to “a speck on the enormous canvas” (251). The problem of multiplicity of contexts and the consequences involved in choosing among them was addressed by Johann Gustav Droysen in Historik (1857-82), which anticipates Benedetto Croce. Droysen accepted the fact that a historian’s ideological biases, often unexamined and arbitrary, came into play and predetermined the investigation. He showed how the historian could use this knowledge to advantage and mapped the different rhetorics of historical representation.

Inevitably, large-scale narrative history sank beneath its own weight and fell from favor. Literary historians chose ever-smaller areas of investigation, though with a wider attention to the variety of causal contexts. As Louis Cazamian said in his and Emile Legouis’s History of English Literature (1924), the “field of literature” needed to be widened to comprehend “philosophy, theology, and the wider results of the sciences” (1971 ed., xxi). Whatever their shortcomings, many narrative literary histories were brilliantly conceived and immensely readable, and perhaps these are the reasons why the genre has not ceased to be written.

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century the weaknesses and failings of the whole historicist enterprise were exposed by Friedrich Nietzsche , Wilhelm Dilthey, and Croce. Although Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy (1872) also falls in the category of narrative literary history, he attacked historical criticism in the second of his Untimely Meditations , “On the Advantages and Disadvantages of History for Life.” Nietzsche argued, not without irony, against history because the preoccupation with the past tended to relativize all knowledge, weigh down individual effort, and sap the vigor “for life.” The past must be “forgotten” in some sense if anything new was to be done.

Dilthey also objected to the positivist domination of history and formulated a theory of Geisteswissenschaften, or “human sciences,” comprising the social and humanistic sciences, which differed from the natural sciences in their interpretive approach. According to his method of Geistesgeschichte, material and cultural (i.e., natural) forces join in the creation of the unifying mind or spirit of a period. The critic must come into contact with the Erlebnis (“lived experience”) of a writer, a hermeneutical recapturing, or “re-experiencing,” of the past that requires not only intellect but imagination and empathy. The biographical essay becomes one of Dilthey’s preferred kinds of practical criticism: “Understanding the totality of an individual’s existence and describing its nature in its historical milieu is a high point of historical writing. . .. Here one appreciates the will of a person in the course of his life and destiny in his dignity as an end in itself” ( Introduction 37). Das Erlebnis und die Dichtung (1906) illustrates his method in studies of G. E. Lessing, Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe, Novalis, and Friedrich Hölderlin.

Like Dilthey, though from a very different point of view, Benedetto Croce offered a critique of historicism that takes place within the historicist tradition itself. In Estética (1902) Croce, who began his career as a historian of the theater and memorials of Naples, attacked dry positivist historicism and sociological criticism for dissolving the essential quality of the literary work, its “intuition,” into myriad causes (psychology, society, race, other literary works). He objected strongly to the organization of literary history on the basis of genres, schools, rhetorical tropes, meters, sophisticated versus folk poetry, the sublime, and so on. These were “pseudoconcepts,” useful labels perhaps for a given purpose but essentially arbitrary designations standing between reader and text. Moreover, none of these “pseudo-concepts” could help decide a case between “poetry” and “nonpoetry”: “All the books dealing with classification and systems of the arts could be burned without any loss whatever.” Croce argued on behalf of the presentness and particularity of the “intuition”; what is past is made present and vital in the act of judgment and narration: “Every true history is contemporary history” ( Aesthetic as Science of Expression and General Linguistic , 1902, trans. Douglas Ainslie, 1953, 114; History 11). His goal was to bring about a cultural renewal in which the traditional humanistic subjects, history and poetry, might once again play their central educative role and a new form of literary history would replace historicism. Croce’s critique was one of the first salvos in the idealist attack on science and positivism that continued well into the twentieth century. Aestheticism itself contributed to the disparagement of science and the revival of the idea of the genius, wholly exceptional, inexplicable, “above” an age.

In the twentieth century literary history lost the theoretical high ground in the academy. Modernism , New Criticism , Russian Formalism , nouvelle critique —all have an antihistoricist bias, posit the autonomy of the work of art, and focus on structural and formal qualities. At the same time, though the age of criticism had succeeded the age of historicism, literary history remained the most common activity within literary studies. Formalist and psychological approaches to a work of art are often found to lean on historical premises or to require a historically determined fact to build a case. As for narrative literary history, the errors and lessons of the nineteenth century were not in vain, and the achievements of modern historical scholarship are characterized by an awareness of the intellectual and rhetorical problems involved in their production.

Twentieth-century literary history offers a variety of models. One of the most common is a dialectical structure in which the main subject oscillates between two poles. In Cazamian’s history, long a standard work, phases of reason and intelligence (the classical) alternate with phases of imagination and feeling (Romantic). The dialectic of J. Livingston Lowes’s Convention and Revolt in Poetry (1919) is apparent from its title. The same writer’s Road to Xanadu: A Study in the Ways of the Imagination (1927) is an exhaustive source study of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” and “Kubla Khan.” In another model the literary historian depicts a “time of troubles” or “babble-like era of confusion—a time of transition from a purer past to a repurified future” (LaCapra 99). R. S. Crane and David Perkins each argue on behalf of “immanentist” theories that study the processes of change from a viewpoint within a tradition. Writers are compared and contrasted with predecessors and successors, and newness and difference are valued. Examples are Brunetifere, the Russian Formalists, W. Jackson Bate’s Burden of the Past and the English Poet (1970), Harold Bloom’s Anxiety of Influence (1973) and The Map of Misreading (1975), and Perkins’s History of Modern Poetry (2 vols., 1976-87), but Vasari’s Lives also has an immanentist theme. Some of the finest modern literary histories mix history, narrative, and criticism, selecting their contexts as particular works of art suggest them: F. O. Matthiessen’s American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman (1941), with its attempt to portray the Geist of transcendentalism; Douglas Bush’s English Literature in the Earlier Seventeenth Century, 1600-1660 (1945); and A Literary History of England, ed. Albert C. Baugh (1948). The period has also produced major literary biographies in Leon Edel on Henry James, Richard Ellmann on James Joyce and Oscar Wilde, and W. Jackson Bate on John Keats and Samuel Johnson.

In the era of postmodermism the theory of literary history has again received serious attention in Michel Foucault, Hayden White, and New Historicism . Postmodern literary histories flout the conventions of historical narrative and display the gaps, differences, discontinuities, crossing (without touching) patterns, not in the hope of capturing the essence of reality, but with the intention of showing that reality has no single essence. The avowedly “postmodern” Columbia Literary History of the United States (1988), which has 66 writers, “acknowledges diversity, complexity, and contradiction by making them structural principles, and it forgoes closure as well as consensus.” “No longer is it possible, or desirable,” the editor claims, “to formulate an image of continuity” (xiii, xxi). The encyclopedic idea has replaced historical narration. New Historicism situates the text at the center of intense contextualization, a single episode being examined from multiple perspectives. This runs the risk of overcontextualization, loss of the larger picture, and failure to account for the dynamics of historical change.

In his skeptical Is Literary History Possible? (1992) Perkins reviews the theory and practice of literary history and comments on the “insurmountable contradictions in organizing, structuring, and presenting the subject” and “the always unsuccessful attempt of every literary history to explain the development of literature that it describes.” At the same time, he defends both the writing and the reading of literary history, maintaining that objectivity is not an all-or-nothing affair. Literary history must not “surrender the idea) of objective knowledge,” for without it “the otherness of the past would entirely deliquesce in endless subjective and ideological reappropriations” (ix, 185). His humanistic position, skeptical of system and classification, shows one way through the antihistoricism and skepticism of the present, while remaining aware of the pitfalls that have beset historical criticism in the past.

Bibliography Walter Jackson Bate, ed., Criticism: The Major Texts (1952, rev. ed., 1970, prefaces published separately as Prefaces to Criticism, 1959); Sacvan Bercovitch, ed., Reconstructing American Literary History (1986); Georg Brandes, Hovedstrpmninger: Det ipde aarhundredes litteratur (6 vols., 1872-90, Main Currents in Nineteenth Century Literature, trans. Diana White and Mary Morison, 1901-5); Douglas Bush, “Literary History and Literary Criticism,” Literary History and Literary Criticism (ed. Leon Edel et al., 1964); Peter Carafiol, The American Ideal: Literary History as a Worldly Activity (1991); Bainard Cowan and Joseph G. Kronick, eds., Theorizing American Literature: Hegel, the Sign, and History (1991); Ronald S. Crane, Critical and Historical Principles of Literary History (1971); Benedetto Croce, La Poesia (1936, 6th ed., 1963, Benedetto Croce’s Poetry and Literature: An Introduction to Its Criticism and History, trans. Giovanni Gullace, 1981), Teoria e storia della storiografia (1917, 2d ed., 1919, History: Its Theory and Practice, trans. Douglas Ainslie, 1921); Philip Damon, ed., Literary Criticism and Historical Understanding (1967); Wilhelm Dilthey, Introduction to the Human Sciences: An Attempt to Lay a Foundation for the Study of Society and History (1883, trans. Ramon J. Betanzos, 1988), Poetry and Experience, Selected Works, vol. 5 (ed. Rudolf A. Makkreel and Frithjof Rodi, 1985); Emory Elliott et al., eds., Columbia Literary History of the United States (1988); Michel Foucault, Les Mots et les choses (1966, The Order of Things: An Archeology of the Human Sciences, trans. Alan Sheridan, 1970); Giovanni Getto, Storia delle storie letterarie (1942); John G. Grumley, History and Totality: Radical Historicism from Hegel to Foucault (1989); Giovanni Gullace, Taine and Brunetière on Criticism (1982); G. W. F. Hegel, The Introduction to Hegel’s Philosophy of Fine Art (trans. Bernard Bosenquet, 1905); Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Building a National Literature: The Case of Germany, 1830- 1870 (1985, trans. Renate Baron Franciscono, 1989); J. R. de J. Jackson, Historical Criticism and Meaning of Texts (1989); Hans Robert Jauss, Toward an Aesthetic of Reception (trans. Timothy Bahti, 1982); Reinhart Koselleck, Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time (1979, trans. Keith Tribe, 1985); Dominick LaCapra, History and Criticism (1985); Émile Legouis and Louis Cazamian, Histoire de la littérature anglaise (1924, History of English Literature, trans. Helen Douglas Irvine, 2 vois., 1926-27, rev. ed., i vol., 1930, rev. ed., 1971); James Russell Lowell, Among My Books (1904); Jerome J. McGann, The Beauty of Inflections: Literary Investigations in Historical Method and Theory (1985); Robert S. Mayo, Herderand the Beginnings of Comparative Literature (1969); G. Μ. Miller, The Historical Point of View in English Literary Criticism from 1570-1770 (1913); David Perkins, Is Literary History Possible? (1992); David Perkins, ed., Theoretical Issues in Literary History (1990); Paul Ricoeur, Temps et récit (3 vols., 1983-85, Time and Narrative, vois. 1-2, trans. Kathleen McLaughlin and David Pellauer, 1984-85, vol. 3, trans. Kathleen Blarney and David Pellauer, 1988); Richard Ruland, The Rediscovery of American Literature: Premises of Critical Taste, 1900-1940 (1967); August von Schlegel, Über dramatische Kunst und Litteratur (2 vois., 1809-11, A Course of Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature, 1817, trans. John Black, rev. A. J. W. Morrison, 1846); Friedrich von Schlegel, Geschichte der alten und neuen Litteratur (1815, Lectures on the History of Literature, Ancient and Modern, 1859); Hippolyte Taine, Histoire de ia littérature anglaise (4 vols., 1863-64, History of English Literature, trans. H. van Laun, 2 vois., 1872, rev. ed., 8 vois., 1897); H. Aram Veeser, ed., The New Historicism (1989); Giambattista Vico, The New Science (1725, 3d ed., 1744, trans. Thomas Goddard Bergin and Max Harold Fisch, 1948, rev. ed., 1968); Robert Weimann, Structure and Society in Literary History: Studies in the History and Theory of Historical Criticism (1976); René Wellek, Discriminations: Further Concepts of Criticism (1970), A History of Modem Criticism, 1750-1950 (8 vois., 1955-93); Hayden White, The Content of the Form: Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation (1987), Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe (1973). Source: Groden, Michael, and Martin Kreiswirth. The Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994.

Share this:

Categories: Philosophy

Tags: historical approach to literature , Historical Criticism , Historical theory , Historical theory and criticism , Literary Criticism , literary criticism in the light of historical evidence , Literary Theory , New Historicism

Related Articles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

How to Write a Historical Criticism Essay

Writing a history essay is indistinguishable to writing any other essay – or is it? Well, the standards are the same. You need a solid presentation – a framework to the reader what you will talk about in the essay. Make beyond any doubt you answer the inquiry. This may appear a moronic thing to call attention to, however all the time in an essay, the question isn’t explicitly answered. A solid presentation gives your reader an indication that you understand the inquiry and realize what you are doing with whatever remains of the essay.

Take a gander at the inquiry carefully and choose the catchphrases. This will manage your research into the topic and keep you concentrated and progressing nicely. Continue returning to the investigation as an update.

Plan for your historical criticism essay

When you have done this, usually accommodating to make a plan or a framework of what you will write. Your .plan should cover the focuses that each paragraph will address including things, for example,

• Have I enough indicates make my argument work?

• Do I have enough referenced proof to help my argument?

• Have I thought about alternative perspectives?

Addressing the above focuses keeps you concentrated on the inquiry and powers you to take a gander at each paragraph and point individually.

The assemblage of historical criticism essay

The main body of your essay ought to contain the majority of proof. As you are writing about history, it is essential that you are factually accurate with dates and so forth, this is after all history, and you can’t change it! Don’t merely incorporate a large amount of information here; make arguments that are relevant and upheld by historical facts and information.

Carrying out a thorough literature survey will enable you to discover an argument that tries to help your answer to the inquiry. A literature survey will allow you to make the feeling of an assemblage of research and offer you an analysis of all available literature, so you don’t have to invest energy researching each one individually, and with the amount of academic writing on history, this is invaluable.

The history essay as with any essay should entirety up all the focuses made earlier and how these help your answer to the inquiry presented. This part of your essay should make logical sense and give your reader a decent diagram of what has been stated in whatever is left of the essay.

The Secret of Writing a Historical Criticism Essay

What is a great essay writing? How can we write the best essay? Elegantly composed – what does that mean? These are challenging inquiries that understudies around the world put to themselves consistently. Certainly, to write an essay isn’t the easiest activity. Like any apprentice, we have to learn our trade as it was done in the good ‘ol days. How? In the first place, by writing. And second? We have to search out books and essays we can learn from. It is necessary to read some great writing before to write your essay. Great writers can rouse you by way of example. Here we will examine a few methods and strategies that can easily be applied to writing assignments.

A standout amongst the most important things is to learn that you ought to always plan your essays before you write them. Recall that writing is a procedure: it comprises of a progression of steps. Before starting, you should answer three inquiries:

A) what is the primary target for the historical criticism essay?

That is, to illuminate, to persuade, to entertain, to argue, to address or to rouse;

B) what is the topic of the historical criticism essay?

Notice that you can state the inquiry you want to answer in the essay itself;

C) what is your answer in a historical criticism essay?

Present your answer in a stable and clear postulation statement: a one-sentence summary. This proposal statement ought to indicate the particular subject of your essay.

That was easy. In this way, having answered these inquiries, you are currently ready to scribble down ideas and then show them in complete sentences. We have the accompanying advances: pick a topic (subject), narrow the problem (make sure to address just a single main idea), research the topic, analyze the inquiry, and make an argument. The problem or concept is the abstract subject of content. Okay, it is essential to work with this template, hence avoiding starting with a blank page.

Organize historical criticism essay

We as a whole realize that religious organization is a critical point in writing a school level essay, yet for the time being inspire the ideas without regard to structure. This is because you are creating an unfinished copy plot. Further, you should make a few choices about the organization. The writing trainers always prescribe that your writing style ought to be enthusiastic and engaging. Be that as it may, how? Make certain that your writing exceeds expectations when you utilize direct style, solid action words, and straightforward vocabulary. Moreover, make sure to vary your sentences structures by alternating short and long sentences and needy and autonomous clauses.

Area of a historical criticism essay

It is presently time to characterize the main areas and subsections of the essay. Notice that each part serves a particular capacity. The introductory paragraph is the most grounded paragraph in the essay. It sets the state of mind: it ought to convey what the primary sentence guarantees and to integrate information, to establish both a historical setting and a profound personal association with the subject exhibited all through the essay. Remember that the main sentence of the essay is punchy, essential to grabbing the reader’s attention.

The second and third paragraphs organize the ideas. What arrangement will you use to organize your ideas? For example chronological request, point by point, categorizing, derivation/enlistment, most important to least important or tight clamp versa, a solitary cause leading to a solitary impact or various impacts/different causes leading to a solitary impact or numerous impacts, spatial request, and so on. Be careful not to surrender to the pitfall of telling instead of showing; try to pick relevant details and use examples, analogies cites, statistics, stories, images, and so on. As such, your idea ought to be adequately upheld with examples. Keep in mind: be exceptionally persuading in explaining your perspectives. At that point, for each point: present it, explain it, and talk about how it is associated with your proposition/claim.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Historical Critical Approach: It's Definition, Reception, and Significance

This is a paper that I wrote for OT Exegesis class, just slightly edited. In the first part, I attempt to triangulate the mentality of historical critical approach by reviewing work of Spinoza, Eichhorn, and Wellhausen. In the second part, I'm reviewing reception of historical criticism in conservative camp, by "close reading" school (Cassuto, Clines) and by theological exegesis movement (Barth, Childs, Moberly, Hays). I contend that whereas historical critical approach is essentially modern, theological exegesis is essentially postmodern. I think that Childs, in a sense, was a prototype postmodern scholar. In the concluding chapter I'm contemplating proper places of synchronic and diachronic approach and giving an example.

Related Papers

Mark Sheridan

Published in: From the Nile to the Rhone and Beyond: Studies in Early Monastic Literature and Scriptural Interpretation (Studia Anselmiana 156) 2012. From what has been said, it will be apparent that one important aspect of the history of theology must be the history of concepts used to organize the reconstruction of the past. These guiding ideas need critical evaluation. It is not easy to escape anachronism, which is built into the knowing process. We inevitably and unconsciously view the past with our ideas, our language and the meanings we have given to words, regardless of what meanings they may have had in the past. Only unstinting critical vigilance can reduce an anachronistic reading of past events and ideas as we try to reconstruct and understand them. In this way critical history can also be an instrument for the theologian (who is not necessarily a different person from the historian), for it helps him to understand the origin and metamorphoses of the concepts that he uses.

Jeffrey M Niles

Higher criticism may be used effectively in the study of God’s holy word as it offers tools of study that are consistent with an orthodox view of inerrancy and may be used within the historical-grammatical method of hermeneutics. Much of the struggle for many evangelicals stems from an improper understanding of many terms involved. Therefore, this position paper proceeds first by examining several definitions pertaining to higher criticism including a peripheral look at the principles and distinctions of historical-grammatical interpretation and historical-critical hermeneutics. Secondly, the higher critical tools for studying the Bible are briefly defined and examples are given. It is not the purpose of this paper to examine all the pros and cons of the various fields of higher criticism. Nor does it attempt to examine the full use or misuse of these tools. Instead, it remains the goal of this project to define certain terms, distinguish various presuppositions and positions, and to provide a few examples of some of the legitimate instruments which have been packaged for the modern student of the Bible. The purpose of this paper is to articulate this writer’s position on these matters and to provide a hermeneutical base from which he and other evangelicals might work in their future interpretation of Scripture.

lee yeachan

Chip Dobbs-Allsopp

Michael Legaspi

David Clines

Goran Gaber

CONSTANTIN OANCEA

In den letzten Jahrzehnten sind unter orthodoxen Theologen hermeneutische Fragestellungen intensiv diskutiert worden. Es gibt auf der einen Seite die Bestrebung, ein orthodoxes Profil der biblischen Exegese zu identifizieren. Auf der anderen Seite wird nach der Legitimität der historisch-kritischen Exegese für die orthodoxe Theologie gefragt. In dieser Studie analysiere ich zunächst die Vorwürfe, die der historisch-kritischen Exegese gebracht wurden, wobei ich auch nach ihrer heutigen Relevanz frage. Danach nenne ich vier Argumente, die aus orthodoxer Sicht die historisch-kritische Herangehensweise an den biblischen Text legitimieren.

Review of Ecumenical Studies Sibiu

Daniel Pricop

This study aims to capture the dynamics of the recent biblical studies in the Orthodox and Western, especially Protestant, theological areas. Both the Orthodox biblical theology and the Western biblical theology are streamlined by research, which can be inspired by each other´s experience. Thus, the Orthodox biblical studies are recently shaped in receiving and developing an exegetical method, and in this sense may appeal to the Western experience, especially the historical-critical method. On the other hand, the Western biblical scholars are concerned with bringing into the present the meaning of biblical texts or their update, in a direction close to the Orthodox biblical experience. The solution to these concerns can be rediscovered in the mutual completion with ecumenical connotations.

Michael Buban

This work is concerned with some basic problems which historical criticism poses to biblical interpretation. The first chapter deals with historical criticism in relation to problems of the text’s historical distance and contemporary significance. Certain key figures from the field of philosophical hermeneutics are briefly introduced (Schleiermacher, Gadamer, Hirsch, Ricoeur), but attention is also paid to the ways how historical criticism was actually practiced (Wellhausen, Mowinckel). It is maintained that historical criticism is a tool in interpretation and does not impede possible appropriation of the text by those who read it with deep affection. The second chapter faces historical criticism as a theological problem, which has become most apparent in the inerrantist milieu and which was more or less successfully answered by canonical approaches. A special attention is given to the canonical approach of Brevard Childs, which is understood against the backdrop of Barth’s doctrine of the Word of God and Frei’s view of biblical narratives. A special attention is given to distinction between approaches of Brevard Childs and James Sanders. It is maintained that Sanders’ canonical criticism provides better interpretive platform, because it wants to address the needs of contemporary interpretive communities through a self-aware historical critical enterprise. The third chapter takes up the problem of violence in the book of Joshua and the problem of theological meaning of the exodus story. Biblical theological insights of James Sanders, James Barr, and Walter Brueggemann are applied. An eye is kept also on Pixley-Levenson debate and it is maintained that traditions of the exodus and conquest must be understood together as literary devices which invite communities of faith to freedom. As a result of the present research, historical criticism is presented as a hermeneutical tool which can help to rescue text’s significance for the contemporary communities of believers.

RELATED PAPERS

Nidia Mendez

sabine sten

gurpreet singh

Femi Dwi Astuti

International Journal on Natural Language Computing

MOHD ANUWI HUSAIN

Materials Advances

Ruslan Garifullin

Estudos em Jornalismo e Mídia

Elaide Martins

Jurnal Ilmiah Mahasiswa Feb

Misbahuddin Azzuhri

Physiological and Biochemical Zoology

Jocelyn Hudon

Achmad Fauzi

Noor Akhmazillah Mohd Fauzi

Journal of Molecular Liquids

usaid azhar

Sustainability

Neba Bhalla

Progress in Pediatric Cardiology

Gaia Spaziani

Godišnjak Pravnog fakulteta Univerziteta u Banjoj Luci, br. 44/2022, str. 185-187

Dejan Pilipović

Ciencia & Investigación Forestal

Sandra Perret

SVMMA. Revista de Cultures Medievals

SVMMA Revista de Cultures Medievals

Alexandru Nedelea

Indian Journal of Science and Technology

Ch Srinivas

Transplantation

Scientific Reports

Türk fizyoterapi ve rehabilitasyon dergisi

Abdurrahman Neyal

Adaptive Behavior

andre ribeiro

alain le hérissé

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

7.2: New Historical Criticism: An Overview

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 14853

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Early scholars of literature thought of history as a progression: events and ideas built on each other in a linear and causal way. History, consequently, could be understood objectively, as a series of dates, people, facts, and events. Once known, history became a static entity. We can see this in the previous example from Wonderland . The Mouse notes that the “driest thing” he knows is that “William the Conqueror, whose cause was favoured by the pope, was soon submitted to by the English, who wanted leaders, and had been of late much accustomed to usurpation and conquest. Edwin and Morcar, the earls of Mercia and Northumbria—” I think we would all agree to moan “Ugh!” In other words, the Mouse sees history as a list of great dead people that must be remembered and recited, a list that refers only to the so-called great events of history: battles, rebellions, and the rise and fall of leaders. Corresponding to this view, literature was thought to directly or indirectly mirror historical reality. Scholars believed that history shaped literature, but literature didn’t shape history.

While this view of history as a static amalgamation of facts is still considered important, other scholars in the movement called New Historicism see the relationship between history and literature quite differently. Today, most literary scholars think of history as a dynamic interplay of cultural, economic, artistic, religious, political, and social forces. They don’t necessarily concentrate solely on kings and nobles, or battles and coronations. In addition, they also focus on the smaller details of history, including the plight of the common person, popular songs and art, periodicals and advertisements—and, of course, literature. New Historical scholarship, it follows, is interdisciplinary , drawing on materials from a number of academic fields that were once thought to be separate or distinct from one another: history, religious studies, political science, sociology, psychology, philosophy, and even the natural sciences. In fact, New Historicism is also called cultural materialism since a text—whether it’s a piece of literature, a religious tract, a political polemic, or a scientific discovery—is seen as an artifact of history, a material entity that reflects larger cultural issues.

Your Process

- How have you learned to connect literature and history? Jot down two or three examples from previous classes.

Sometimes it’s obvious the way history can help us understand a piece of literature. When reading William Butler Yeats’s poem “Easter 1916” (which you can read online at http://www.poetryfoundation .org/poem/172061 ), for instance, readers immediately wonder how the date named in the poem’s title shapes the poem’s meaning.“Easter 1916 by William Butler Yeats,” The Atlantic Online, http://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/unbound/poetry/soundings/easter.htm .Curious readers might quickly look up that Easter date and discover that leaders of the Irish independence movement staged a short-lived revolt against British rule during Easter week in 1916. The rebellion was quickly ended by British forces, and the rebel leaders were tried and executed. Those curious readers might then understand the allusions that Yeats makes to each of the executed Irish leaders in his poem and gain a better sense of what Yeats hopes to convey about Ireland’s past and future through his poem’s symbols and language. Many writers, like Yeats, use their art to directly address social, political, military, or economic debates in their cultures. These writers enter into the social discourse of their time, this discourse being formed by the cultural conditions that define the age. Furthermore, this discourse reflects the ideology of the society at the time, which is the collective ideas—including political, economic, and religious ideas—that guide the way a culture views and talks about itself. This cultural ideology, in turn, reflects the power structures that control—or attempt to control—the discourse of a society and often control the way literature is published, read, and interpreted. Literature, then, as a societal discourse comments on and is influenced by the other cultural discourses, which reflect or resist the ideology that is based on the power structures of society.

Let’s turn to another example to illuminate these issues. One of the most influential books in American history was Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), which Stowe wrote to protest slavery in the South before the Civil War.“ Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture,” University of Virginia, http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/sitemap.html . Uncle Tom’s Cabin was an instant bestseller that did much to popularize the abolitionist movement in the northern United States. Legend has it that when Abraham Lincoln met Stowe during the Civil War, he greeted her, by saying “So you’re the little woman that wrote the book that started this great war.” In the case of Uncle Tom’s Cabin , then, it’s clear that understanding the histories of slavery, abolitionism, and antebellum regional tensions can help us make sense of Stowe’s novel.

But history informs literature in less direct ways, as well. In fact, many literary scholars—in particular, New Historical scholars—would insist that every work of literature, whether it explicitly mentions a historical event or not, is shaped by the moment of its composition (and that works of literature shape their moment of composition in turn). The American history of the Vietnam war is a great example, for we continue to interpret and revise that history, and literature (including memoirs) is a key material product that influences that revision: think of Michael Herr’s Dispatches (1977); Philip Caputo’s A Rumor of War (1977); Bobbie Anne Mason’s In Country (1985); Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried (1990); Robert Olen Butler’s A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain (1992); and, most recently, Karl Marlantes’s Matterhorn (2010).Michael Herr, Dispatches (New York: Vintage, 1977); Philip Carputo, A Rumor of War (New York: Ballantine, 1977); Bobbie Anne Mason, In Country (New York: HarperCollins, 2005); Tim O’Brien, The Things They Carried (New York: Mariner, 2009); Robert Olen Butler, A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain: Stories (New York: Holt, 1992); Karl Marlantes, Matterhorn (New York: Atlantic Monthly, 2010).

- Pick something you’ve read or watched recently. It doesn’t matter what you choose: the Harry Potter series, Twilight , The Hunger Games , even Jersey Shore or American Idol . Now reflect on what that book, movie, or television show tells you about your culture. What discourses or ideologies (values, priorities, concerns) does your cultural artifact reveal? Jot down your thoughts.

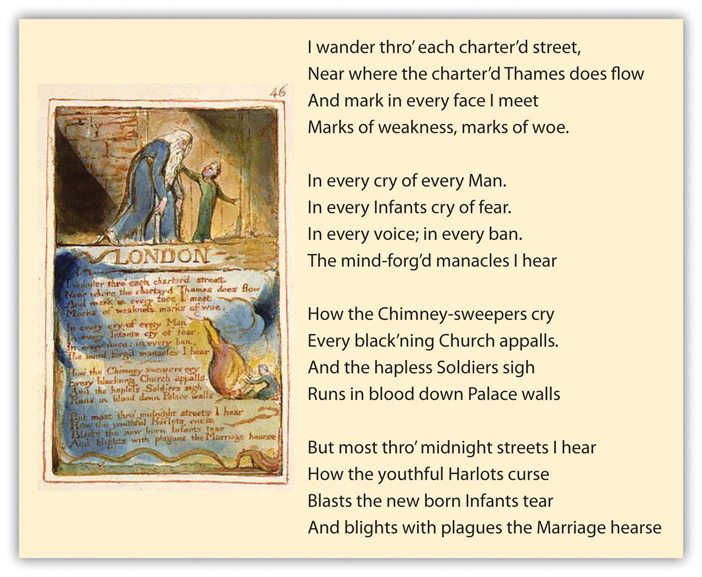

As you can see, authors influence their cultures and they, in turn, are influenced by the social, political, military, and economic concerns of their cultures. To review the connection between literature and history, let’s look at one final example, “London” ( http://www.blakearchive.org/exist/blake/archive/object.xq?objectid=songsie.b.illbk.36&java=yes ), written by the poet William Blake in 1794.

Illustration by William Blake for “London” from his Songs of Innocence and Experience (1794).

Unlike Yeats or Stowe, Blake does not refer directly to specific events or people from the late eighteenth century. Yet this poem directly confronts many of the most pressing social issues of Blake’s day. The first stanza, for example, refers to the “charter’d streets” and “charter’d Thames.” If we look up the meaning of the word “charter,” we find that the word has several meanings. Merriam-Webster Online , s.v. “charter,” http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/charter . “Charter” can refer to a deed or a contract. When Blake refers to “charter’d” streets, he might be alluding to the growing importance of London as a center of industry and commerce. A “charter” also defines boundaries and control. When Blake refers to “charter’d Thames,” then, he implies that nature—the Thames is the river that runs through London—has been constricted by modern society. If you look through the rest of the poem, you can see many other historical issues that a scholar might be interested in exploring: the plight of child laborers (“the Chimney-sweepers cry”); the role of the Church (“Every black’ning Church”), the monarchy (“down Palace walls”), or the military (“the hapless Soldiers sigh”) in English society; or even the problem of sexually transmitted disease (“blights with plagues the Marriage hearse”). You will also notice that Blake provided an etching for this poem and the poems that compose The Songs of Innocence (1789) and The Songs of Experience (in which “London” was published), so Blake is also engaging in the artistic movement of his day and the very production of bookmaking itself. And we would be remiss if we did not mention that Blake wrote these poems during the French Revolution (1789–99), where he initially hoped that the revolution would bring freedom to all individuals but soon recognized the brutality of the movement. That’s a lot to ask of a sixteen-line poem! But each of these topics is ripe for further investigation that might lead to an engaging critical paper.

When scholars dig into one historical aspect of a literary work, we call that process parallel reading . Parallel reading involves examining the literary text in light of other contemporary texts: newspaper articles, religious pamphlets, economic reports, political documents, and so on. These different types of texts, considered equally, help scholars construct a richer understanding of history. Scholars learn not only what happened but also how people understood what happened. By reading historical and literary texts in parallel, scholars create, to use a phrase from anthropology, a thick description that centers the literary text as both a product and a contributor to its historical moment. A story might respond to a particular historical reality, for example, and then the story might help shape society’s attitude toward that reality, as Uncle Tom’s Cabin sparked a national movement to abolish slavery in the United States. To help us think through these ideas further, let’s look at a student’s research and writing process.

Historical Criticism

We found 5 free papers on Historical Criticism

Essay examples, literary criticism.

The story that is the subject of this piece of literary criticism is Margaret Laurence’s “The Loons,” part of her collection of short stories titled A Bird in the House. Though considered a collection of short stories, this set of narratives also forms a cohesive whole in which the same characters and setting appear…

A Critical Essay on: History and Criticism

Dr. Reynaldo C. Ileto is an Honorary Professor whose area of expertise are Asian History, Religion and Society, Postcolonial Studies, and Government and Politics of Asia and the Pacific. Ileto has many publications, including Filipinos and their Revolution (1998). This particular set of texts and essays include the history of Philippine Revolution, walking through time…

The Jungle Historical Criticism

Despite its horrible content (or perhaps because of it? ), The Jungle turned into an overnight bestseller. Sinclair’s family is even remembered today mainly because of the effect that The Jungle had on American business and politics. This camp landed Sinclair on both the writing and the political representation. While you’re not expected to find…

Historical Criticism of Anton Chekhov’s The Lady with the Dog Analysis

Historical Criticism of Anton Chekhov’s The Lady with the DogRussian short story writer and playwright Anton Chekhov’s The Lady with the Dog (1899) is a brilliant exploration of the potential for social mores and social institution to undermine the individual desire for freedom and individual definition of happiness. According to many literary critics, Chekhov’s style…

New Historicism & Marxist Literary Criticism on “A Cask of Amontillado”

Cask Of Amontillado

New Historicism & Marxist Literary Criticism on “A Cask of Amontillado” “A Cask of Amontillado” by Edgar Allan Poe was first published in 1846 in an American magazine. The historical context of this piece is as much about revenge as the plot in the story itself. During this time, Poe had acquired a bitter rival…

Frequently Asked Questions about Historical Criticism

Don't hesitate to contact us. We are ready to help you 24/7

Hi, my name is Amy 👋

In case you can't find a relevant example, our professional writers are ready to help you write a unique paper. Just talk to our smart assistant Amy and she'll connect you with the best match.

The Critical Decision: America’s Entry into World War II in 1941

This essay about America’s entry into World War II in 1941 explores the significant consequences and the historical context that led to this pivotal decision. It examines the internal debates over intervention versus isolationism, the geopolitical dynamics at play, and the ethical dilemmas faced by the U.S. The essay also discusses the critical role of the Lend-Lease Act, the pressures from the European and Pacific theatres, and the impact of the Pearl Harbor attack, which unified the U.S. in its resolve to enter the war.

How it works

In the annals of history, the decision for America to enter World War II in 1941 stands as a pivotal moment fraught with significant consequences. This momentous decision was precipitated by the infamous attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th, which jolted the United States from its stance of neutrality into the throes of a global conflict. The path leading to this critical day was characterized by a complex interplay of geopolitical strategies, domestic debates over isolationism versus interventionism, and significant ethical dilemmas.

Before the attack, America was deeply divided over the question of involvement in the war. The scars of World War I were still fresh, and a strong sentiment of isolationism pervaded the national psyche. However, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was acutely aware of the threats posed by the rise of fascism and militarism in Europe and Asia. Through initiatives like the Lend-Lease Act, he aimed to bolster Allied forces while maintaining American neutrality, a stance that increasingly strained under the pressures of international demands.

Europe was meanwhile under siege. Hitler’s aggressive blitzkrieg had overwhelmed most of the continent, leaving Britain to contend alone against the relentless Nazi onslaught. The dire situation was underscored by the Battle of Britain and the perilous disruptions caused by German U-boats to Allied shipping lines. Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill fervently sought greater support from Roosevelt, emphasizing the critical need for American aid to prevent a catastrophic defeat for the Allies.

Simultaneously, tensions were mounting in the Pacific. Japan’s imperialist pursuits in China and Indochina were met with grave concern by U.S. policymakers, leading to economic sanctions intended to deter further Japanese expansion. Viewed by Japan as a direct threat to their ambitions in Southeast Asia, these tensions set both nations on an inevitable collision course.

The turning point came with the sudden and devastating attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese Imperial Navy, which left the U.S. shocked and unified in its resolve for action. President Roosevelt’s subsequent speech to Congress, where he branded December 7th, 1941, as “a date which will live in infamy,” rallied the nation and led to a formal declaration of war against Japan.

The aftermath saw a swift mobilization of the American war effort. Despite initial resistance from isolationist factions, led by figures such as Senator Robert A. Taft and aviator Charles Lindbergh, who advocated for focusing on domestic concerns and cautioned against overseas entanglements, the U.S. decisively entered the war.

However, America’s involvement was not without controversy. The internment of Japanese Americans, prompted by racial prejudice and wartime fear, marked a regrettable episode of violated civil liberties and constitutional rights, reflecting the darker aspects of national response during crisis.

Despite these internal and moral conflicts, America’s entry into World War II was crucial in shifting the balance of power. The U.S. leveraged its industrial capacity to become the “Arsenal of Democracy,” supporting its military and allies with a vast production of war materials. On the battlefronts, American forces demonstrated bravery and strategic acumen, contributing significantly to the eventual defeat of Axis powers.

Ultimately, America’s decision to enter the war in 1941 reshaped its role on the global stage and underscored its commitment to democratic values and human rights. This decision, while fraught with significant human and ethical costs, remains a defining chapter in U.S. history, offering enduring lessons on the complexities of international engagement and the pursuit of justice.

Cite this page

The Critical Decision: America's Entry into World War II in 1941. (2024, May 12). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/the-critical-decision-americas-entry-into-world-war-ii-in-1941/

"The Critical Decision: America's Entry into World War II in 1941." PapersOwl.com , 12 May 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/the-critical-decision-americas-entry-into-world-war-ii-in-1941/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Critical Decision: America's Entry into World War II in 1941 . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-critical-decision-americas-entry-into-world-war-ii-in-1941/ [Accessed: 12 May. 2024]

"The Critical Decision: America's Entry into World War II in 1941." PapersOwl.com, May 12, 2024. Accessed May 12, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/the-critical-decision-americas-entry-into-world-war-ii-in-1941/

"The Critical Decision: America's Entry into World War II in 1941," PapersOwl.com , 12-May-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-critical-decision-americas-entry-into-world-war-ii-in-1941/. [Accessed: 12-May-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Critical Decision: America's Entry into World War II in 1941 . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-critical-decision-americas-entry-into-world-war-ii-in-1941/ [Accessed: 12-May-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

- Social Sciences

- Religion and Theology

Historical Criticism: Definition, Methods, and Examples

Format: APA

Academic level: College

Paper type: Essay (Any Type)

Downloads: 0

James Holm Reply

The use of historical criticism in exegesis is by far the widely acknowledged method of biblical interpretation. Proponents argue that the historical context gives meaning to the scriptures as it helps one to understand the life and situation surrounding the text. “The surrounding context of any passage, verse, or word, helps shape the meaning of that passage, verse, or word.”(Cartwright et al, 2016) It is important to understand the preceding environment that motivated the passage, or the environment which the passage prophesized. However, there are diverse interpretations of biblical passages among Christians. Some Christians hold that there should be openness in the interpretation of the bible long as the Christian beliefs are not undermined. Antagonists of the historical and contextual criticism argue that there exists a chronological and situational difference between the environment surrounding the passage and the contemporary environment. Others may point out that the applicability of the Old Testament covenants to the Christian life was cancelled by the suffering and death of Christ (Klein et al. 2017). Regardless of the history and context, it is paramount that the interpretation remains within the doctrines of Christianity.

Joshua Sahatoo DB Forum 3 Reply

Hebrew and Greek were the first languages in which the bible was written. This fact gives immense importance to these two languages as they are regarded as the pioneers of the Biblical era. It is understandable that interpreters of the scripture may tend to make reference to Hebrew and Greek words used in passages. Proponents argue that this reference increases understanding of the contextual meaning of the words, enhancing better analysis and interpretation. It is a way of acknowledging the history of the scripture which undoubtedly is important in understanding the passage. “A commitment to understanding historical context is one of the best ways to honor the biblical past so that it remains relevant to our present" (Cartwright et al., p. 137). But do we always have to make reference to the Hebrew and Greek words? Klein et al. (2017) point out that besides historical context, translations form the baseline of biblical interpretation. Some people believe that meanings of the word may get distorted or lost during translations. However, it should be noted that making references to the ancient languages may also make understanding difficult. The people prefer straightforward and easy to understand languages, especially in seminars and church sessions. There is no better language to understand that the person’s native or local language without Greek or Hebrew word permutations.

Delegate your assignment to our experts and they will do the rest.

References

Cartwright, J., Gutierrez, B., & Hulshof, C. (2016). Everyday Bible study. Nashville, TN: Lifeway Church Resources. ISBN: 9781462740109.

Klein, W. W., Blomberg, C. L., & Hubbard Jr, R. L. (2017). Introduction to biblical interpretation . Zondervan.

Bottom of Form

- The 21st Century Judaism Religion

- Messiah - George Frideric Handel

Select style:

StudyBounty. (2023, September 15). Historical Criticism: Definition, Methods, and Examples . https://studybounty.com/historical-criticism-definition-methods-and-examples-essay

Hire an expert to write you a 100% unique paper aligned to your needs.

Related essays

We post free essay examples for college on a regular basis. Stay in the know!

Critical Evaluation of Harold A. Netland’s Christianity & Religious Diversity

Words: 1953

The History of Paul-The Silent Years

Words: 2688

The Foundation of a Building: Everything You Need to Know

Conflict between religion and science, prayer and healing: a guide to spiritual wellness, "3 idiots" film analysis.

Words: 1568

Running out of time ?

Entrust your assignment to proficient writers and receive TOP-quality paper before the deadline is over.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2 What Is Biographical Criticism?

This chapter will demonstrate how subsequent chapters will be organized throughout the book.

At some point in your educational journey, you’ve probably been asked to write a book report. As part of that report, you probably did some brief research about the author’s life to better understand what factors influenced his/her/their work.

Critical Lens: Biographical Criticism

When we look at biographical or historical information to help us interpret the author’s intent in a text, we are practicing historical or biographical criticism . With this type of criticism, popular throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the author—and the author’s intent—are the targets of our analysis. We read the text in tandem with the author’s life, searching for clues about what the author meant within the words of the text and life events. Throughout most of literary history, this is what we meant when we talked about literary criticism or literary analysis.

Learning Objectives

- Using a literary theory, choose appropriate elements of literature (formal, content, or context) to focus on in support of an interpretation (CLO 2.3)

- Emphasize what the work does and how it does it with respect to form, content, and context (CLO 2.4)

- Provide a thoughtful, thorough, and convincing interpretation of a text in support of a well-crafted thesis statement (CLO 5.1)

Applying Biographical Criticism to a Text

As a refresher on how this type of criticism works, let’s look at a poem by African American poet Phyllis Wheatley written in 1772 and published in 1773.

To the Right Honorable William, Earl of Dartmouth

Hail, happy day, when, smiling like the morn, Fair Freedom rose New-England to adorn: The northern clime beneath her genial ray, Dartmouth, congratulates thy blissful sway: Elate with hope her race no longer mourns, Each soul expands, each grateful bosom burns, While in thine hand with pleasure we behold The silken reins, and Freedom’s charms unfold. Long lost to realms beneath the northern skies

She shines supreme, while hated faction dies: Soon as appear’d the Goddess long desir’d, Sick at the view, she languish’d and expir’d; Thus from the splendors of the morning light The owl in sadness seeks the caves of night. No more, America, in mournful strain Of wrongs, and grievance unredress’d complain, No longer shalt thou dread the iron chain, Which wanton Tyranny with lawless hand Had made, and with it meant t’ enslave the land.

Should you, my lord, while you peruse my song, Wonder from whence my love of Freedom sprung, Whence flow these wishes for the common good, By feeling hearts alone best understood, I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat: What pangs excruciating must molest, What sorrows labour in my parent’s breast? Steel’d was that soul and by no misery mov’d That from a father seiz’d his babe belov’d: Such, such my case. And can I then but pray Others may never feel tyrannic sway?

For favours past, great Sir, our thanks are due, And thee we ask thy favours to renew, Since in thy pow’r, as in thy will before, To sooth the griefs, which thou did’st once deplore. May heav’nly grace the sacred sanction give To all thy works, and thou for ever live Not only on the wings of fleeting Fame, Though praise immortal crowns the patriot’s name, But to conduct to heav’ns refulgent fane, May fiery coursers sweep th’ ethereal plain, And bear thee upwards to that blest abode, Where, like the prophet, thou shalt find thy God.

Wheatley’s literary talent was recognized and celebrated by her contemporaries. Here’s a brief biographical sketch written nearly 60 years after her death from Biographical Sketches and Interesting Anecdotes of Persons of Color by A. Mott (1839):

A Short Account of Phillis Wheatley

1. Although the state of Massachusetts never was so deeply involved in the African slave trade as most of the other states, yet before the war which separated the United States of America from Great Britain, and gave us the title of a free and independent nation, there were many of the poor Africans brought into their ports and sold for slaves.

2. In the year 1761, a little girl about 7 or 8 years old was stolen from her parents in Africa, and being put on board a ship was brought to Boston, where she was sold for a slave to John Wheatley, a respectable inhabitant of that town. Her master giving her the name of Phillis, and she assuming that of her master, she was of course called Phillis Wheatley.

3. Being of an active disposition, and very attentive and industrious, she soon learned the English language, and in about sixteen months so perfectly, that she could read any of the most difficult parts of the Scriptures, to the great astonishment of those who heard her. And this she learned without any school instruction except what was taught her in the family.

4. The art of writing she obtained by her own industry and curiosity, and in so short a time that in the year 1765, when she was not more than twelve years of age,she was capable of writing letters to her friends on various subjects. She also wrote to several persons in high stations. In one of her communications to the Earl of Dartmouth, on the subject of Freedom, she has the following lines:

“Should you, my lord, while you pursue my song, Wonder from whence my love of Freedom sprung, Whence flow these wishes for the common good, By feeling hearts alone best understood— I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate, Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat: What pangs excruciating must molest, What sorrows labour in my parent’s breast? Steel’d was that soul, and by no misery mov’d, That from a father seized the babe belov’d. Such, such my case—and can I then but pray, Others may never feel tyrannic sway?”

5. In her leisure moments she often indulged herself in writing poetry, and a small volume of her composition was published in 1773, when she was about nineteen years of age, attested by the Governor of Massachusetts, and a number of the most respectable inhabitants of Boston, in the following language:

6. “We, whose names are under-written, do assure the world that the Poems specified in the following pages were, (as we verily believe,) written by Phillis, a young negro girl, who was but a few years since, brought an uncultivated barbarian from Africa; and has ever since been, and now is, under the disadvantage of serving as a slave in a family in this town. She has been examined by some of the best judges, and is thought qualified to write them.”*

7. Her master says—”Having a great inclination to learn the Latin language, she has made some progress in it.”

8. After the publication of the little volume mentioned, and about the 21st year of her age, she was liberated; but she continued in her master’s family, where she was much respected for her good conduct. Many of the most respectable inhabitants of Boston and its vicinity, visiting at the house, were pleased with an opportunity of conversing with Phillis, and observing her modest deportment, and the cultivation of her mind.

9. When about 23, she was married to a person of her own colour, who having also obtained considerable learning, kept a grocery, and officiated as a lawyer, under the title of Doctor Peters, pleading the cause of his brethren the Africans, before the tribunals of the state.