Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10 The Power of Extension: Research, Teaching, and Outreach for Broader Impacts

Jeremy Elliott-Engel; Courtney Crist; and Gordon Jones

Introduction

The land-grant university (LGU) system was created on a foundation of three missions: classroom-teaching, research, and a specific type of community education called Extension [1] . The majority of this book has highlighted and focused on the formal higher-education classroom-teaching experience of the mission, and your doctoral program has provided training on the research component. This chapter will focus on the third mission, Extension (at non-LGU institutions similar efforts may be called outreach, engagement, or service). The Cooperative Extension System (CES) has a mission to translate research-based findings, best practices, and information in four broad program areas: youth development (4-H), agriculture and natural resources (ANR), family and consumer sciences (FCS), and community development (Seevers et al., 2007). Land-grant universities employ Extension educators to work from campus and state regional centers, as well as in local county or city offices to deliver Extension education programs based on stakeholder needs—including state, industry, and community needs (Baughman et al., 2012). It should be noted that university and state Extension organizational structures and program priority areas differ by state.

Extension educators offer nonformal educational programs to both businesses and the citizens of their communities. Local Extension educators are supported by research and Extension faculty across departments from the LGU. To start our journey to understanding what Extension education is, and how you, as a future or current LGU faculty member and researcher, will support Extension education, we will recount the history of the LGU mission, then introduce a learning theory for nonformal education, and finally explain the unique planning processes of Extension education programs.

The objectives of this chapter are to provide a translation of effective teaching practices from the higher-education classroom and emphasize the interconnections of teaching and research disciplines to impactful community outreach, engagement, and impact.

This chapter will discuss…

- The origin and mission of the land-grant university system.

- Educational theory utilized in non-formal educational settings.

- Educational learning contexts and environments outside of the formal classroom.

- How to establish and integrate a research, teaching, and outreach educational program to support broader impacts

What Is Extension?

The use of the word “Extension” derives from an educational development in England during the second half of the nineteenth century. Around 1850, discussions began in the two ancient universities of Oxford and Cambridge about how they could serve the educational needs, near to their homes, of the rapidly growing populations in the industrial, urban area. It was not until 1867 that a first practical attempt was made in what was designated “university Extension,” but the activity developed quickly to become a well-established movement before the end of the century. (Jones & Gartforth, 1997, p. 1)

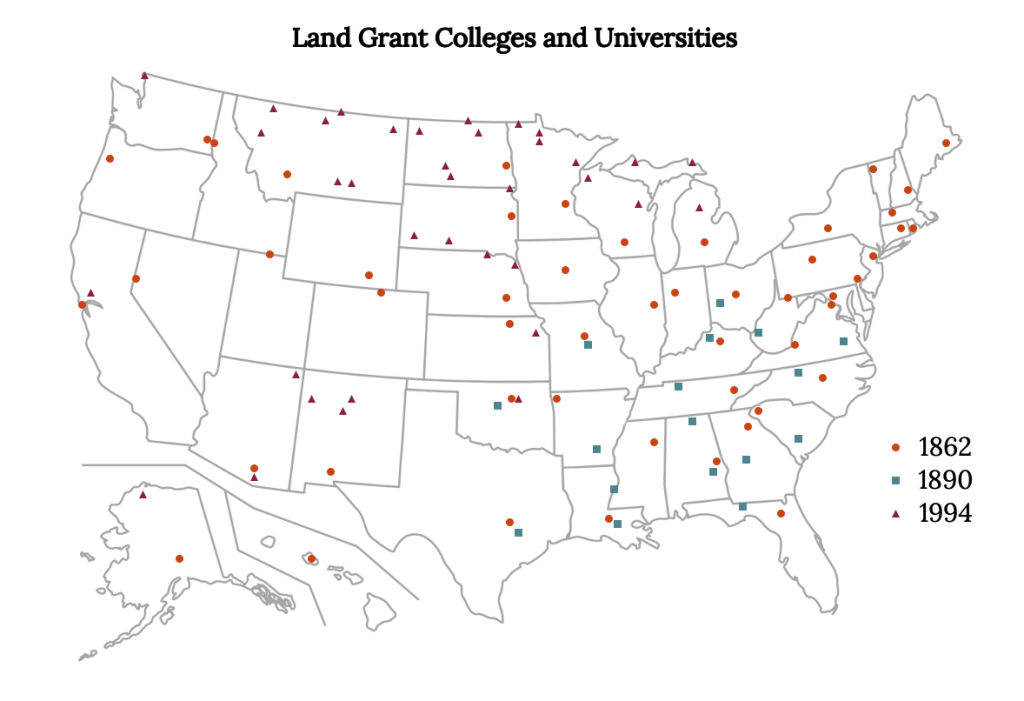

The idea of Extension started in the late nineteenth century in both the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States of America (US) with three components: adult education, technology transfer, and advisory services (Shinn et al., 2009). In the United States, the development of the Extension system started on July 2, 1862, when President Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Land-Grant College Act (Morrill Land-Grant Act, 1862). This legislation forming the LGU system was sponsored by Vermont Senator Justin Smith Morrill. Passage of the Morrill Act was unexpected because President James Buchanan had previously vetoed a version of the act in June 1860 due to Southern state representatives’ criticisms that granting Western territorial land was an imprudent use of resources. The Western territorial lands were lands taken from Native Americans by the US government. The bill that was vetoed had granted just 2,000 acres for a university’s setup. The successful version of the Morrill Act granted 30,000 acres of Western territorial land as an endowment to establish at least one college per state and territory (Wessel & Wessel, 1982). The Morrill Act successfully passed in 1862 largely because Southern states representatives were absent from Congress at the time of the vote due to the Civil War (Lee, 1963).

The established purpose of the LGU institutions is to make liberal and practical education available to all citizens of the nation, particularly the working class (Duemer, 2007; Depauw & McNamee, 2006; Lee, 1963; Simon, 1963). To achieve this mission the Morrill Act and its successors were deliberately designed not simply to encourage, but to force the states to significantly increase their efforts on behalf of higher education. The federal government, having promoted the establishment of new colleges, made it incumbent upon the states to supply the means of future development and expansion (Lee, 1963, p. 27). The LGUs married the humanistic idea of the renaissance university (liberal education) and the German university (practical education) (Bonnen, 1998). This combination of liberal and practical education in one institution was designed to democratize education and provide educational opportunities for all citizens. The LGUs evolved into entities with a three-pronged mission of research, teaching, and outreach (Simon, 1963).

In 1890, a second Morrill Act was passed, which prohibited the distribution of money to states that made race a consideration when making decisions about admission to their state’s 1862 LGU institution (Lee & Keys, 2013). Each state had to demonstrate that race was not a criterion when considering a student’s admission to the LGU. If Blacks or other persons of color were unable to be admitted because of race, then a separate LGU was established for them (Comer et al., 2006). This resulted in 19 previously slave-holding states establishing public colleges serving Blacks (Allen & Jewell, 2002; Provasnik et al., 2004; Redd, 1998; Roebuck & Murty, 1993). These “1890” institutions were awarded cash in lieu of land; however, they retain the designation of “land grant” due to the legislation. The 1890 institutions brought public and practical education to previously excluded and marginalized populations.

In 1994, the Equity in Educational Land-Grant Status Act established 29 tribal colleges and universities as “1994” tribal land-grant institutions. These institutions have a mission to provide federal government resources to improve the lives of Native American students through higher education (USDA-NIFA, 2015).

The three current missions of research, teaching, and outreach were achieved through additional legislation. The 1887 Hatch Experiment Station Act (Hatch Act) established the State Agricultural Experiment Station (SAES) to improve agricultural production through applied agriculture research and to provide educational outreach opportunities through the LGUs (Knoblauch et al., 1962). Joining the locally responsive research from the SAES with the LGUs expanded the capacity for classroom education and provided the opportunity to share knowledge onsite at research stations across each state. However, to extend the positive benefits of knowledge farther afield, more efforts were needed. Cooperative Extension began when President Woodrow Wilson signed the Smith-Lever Act into law on May 8, 1914. The purpose of Extension was declared to be an effort “to aid in diffusing among the people of the U.S. useful and practical information on subjects related to agriculture and home economics, and to encourage the application of the same” (Rasmussen, 1989, p. 7). The Smith-Lever Act did not specifically state that Extension services should only work with farmers (Ilvento, 1997; Rogers, 1988). Extension was designed to take the research-based knowledge generated at the LGUs and the SAES to US citizens through a partnership between LGUs and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

The implementation of this organizational system had significant and profound effects on adult education in the United States. Liberty Hyde Bailey, a renowned botanist and Cornell faculty member, was instrumental in the formation of the Extension service and 4-H; he argued that Extension could not address agricultural production issues without also addressing the social and human issues facing rural communities (Ilvento, 1997; Rosenberg, 2015). At the time, he lost the argument to Seaman Knapp, then president of Iowa Agricultural College, who laid the foundation of the Agricultural Experiment stations as an employee of the USDA. Knapp argued the role of Extension was solely to educate reluctant farmers on new technology (Ilvento, 1997; Peters, 1996). Because of Knapp’s influence, the purpose of Extension began as instruction and practical demonstration concerning agriculture and home economics for individuals in communities across the state who would otherwise not have access to information and new innovations.

The name Cooperative Extension emerged from the cost sharing, which required using state and local funding sources to match the funds contributed by the USDA. Currently, federal partners supply approximately 30 percent of the system’s financial resources, while state and local (e.g., county) funds make up the remaining portion of the budget (Rasmussen, 1989). Further, following funding trends within higher education, a growing share of Extension budgets consists of extramural grants and contracts (Jackson & Johnson, 1999).

The focus of US Extension work has evolved from primarily relaying technical innovation to also providing leadership for social, cultural, and community change and development (Stephenson, 2011) by partnering with communities to identify solutions to challenges in partnership (Vines, 2017). As previously mentioned, this adaption reflects a move toward Bailey’s perspective that community programming cannot provide technical knowledge without first supporting the individual and social needs of the participants. Extension, because of the nature of the organization, has always engaged with communities, and more importantly, has acted as an accessible and knowledgeable resource for the communities they serve. Extension professionals have sought to respond to society and community needs, whether in response to supporting a reduction of poverty in rural communities (Rogers, 1988; Selznick, 2011) or helping the nation survive World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II (Rasmussen, 1994) by ensuring the sustainability of food resources, and by supporting rural electrification (Rosenberg, 2015), rural telephone, and today, broadband access (Whitacre, 2018). The mission of Extension has expanded from a focus on agriculture and family and consumer sciences to incorporate areas of health, community, and business development, and from solely rural audiences to rural, suburban, and urban communities (Morse, 2009; DePauw & McNamee, 2006). While work remains to be done, 1862 LGUs in every state and territory work to serve a demographically representative population and address community challenges (Elliott-Engel, 2018), and 1890 and 1994 LGUs target historically underserved populations with specific interventions.

What Is Extension Education?

Early practitioners of … Extension education drew from foundational theories of learning and teaching (Dewey, 1938; James, 1907; Lancelot, 1944). During the early evolution, knowledge was grounded in observation and experience and passed to others through direct engagement methods. Over time, …Extension education integrated the principles of learning and teaching, applied research, and Extension outreach. Today’s field of study draws from educational psychology and the works of Bandura (1977), Bruner (1966), Gagné (1985), Knowles (1975), Piaget (1970), Thorndike (1932), Vygotsky (1978), and others. Perspectives of learning rise from the educational theories of behaviorism and constructivism, while the perspectives of teaching are drawn from the works of Freire (1972), Habermas (1988), Kolb (1984), Lewin (1951), and others who advanced problem solving, critical thinking, and communicative reason. (Shinn et al., 2009, p.77)

Extension is an organization that continuously plans, executes, and evaluates programs with learners (Meena et al., 2019, p. 17) and updates or modifies as needed. Extension education is a knowledge exchange system that engages change agents in a participatory persuasive process of educating stakeholders in a changing world (Shinn et al., 2009). Extension educators are professionals in the social, behavioral, and natural and life sciences who use sound principles of teaching and learning, and they integrate the sciences relevant for the development of human capital and for the sustainability of agriculture, food, renewable natural resources, and the environment (Shinn et al., 2009).

Extension education can be conducted and executed in many forms including in-person education (e.g., workshops, seminars, demonstrations, short courses), publication (e.g., website, print media), and using social media (e.g., infographics). In many non-LGU institutions, Extension is commonly referred to as community outreach or engagement. These terms originated in the Extension education movement. The work, when adopted, contributes to the democratic process of encouraging institutions of higher education to help extend research efforts beyond the students in the classroom and fellow researchers in academe to communities or businesses where it can be directly applied.

There are several principles that are important to keep in mind to ensure success in extending research and knowledge outside the higher education environment. The education of community members has different principles than the formal education setting. In formal education settings, motivation is incentivized by earning grades needed to receive certification through the earning of a degree. In nonformal education settings, education centers around learners’ motivations to obtain the knowledge being offered and its impact on their livelihood or success.

Nonformal Education Theory

Nonformal education is the learning instruction provided beyond the traditional secondary education system designed to prepare individuals (adolescents and adults) to achieve their personal, social, and economic life goals (Okojie, 2020). When extending their research beyond the formal classroom, the educator becomes an adult and nonformal educator, also known as an Extension educator. Extension educators remain intentional and systematic while also recognizing content can and should be adapted for different clientele (Etling, 1993).

Researchers have defined adult learners in overlapping but somewhat different ways. Merriam (2008) describes adult learners as those whose age, social roles, and self-perception define them as adults. Adult learning theory is informed by foundational scholars in related fields such as psychology and sociology. The theories of behaviorism, cognitivism, humanism, constructivism, and connectivism illuminate different learner types and their disposition toward the process of education (Balakrishnan, 2020). The main ideas, approaches, and contributions of these theories have been summarized for your reference in table 10.1. The denotation of the theory, approach, and application is indicated by the theorists’ major works and forthcoming implications.

Each theorist presents a systematic explanation for the observed facts and laws that relate to a specific aspect of life (Williamson, 2002), in this case the nonformal learner. Each of the theorists allows the Extension educator to conceptualize the learner in different ways. The nonformal learners bring their lived experiences, and thus, their varied motivations to the educational process. The educator in the nonformal context must think about barriers to participation and adoption (Rogers, 2003) of the practice or materials presented.

Nonformal Education Is Present Everywhere

The nonformal educator views all contexts and environments as a possible classroom and everyone as a possible student. The educator working with or through Extension (Extension Educator) has the flexibility to extend research and technical knowledge across many meaningful educational strategies (Fordham, 1979). The variety of strategies provides the Extension educator much greater flexibility, versatility, and adaptability than their formal classroom educator counterpart to meet the diverse learning needs of each clientele, and to adapt as those needs evolve (Coombs, 1976). Education can happen within numerous contexts. Common educational strategies for Extension education can be broken into three broad categories: An Extension educator can support a learner’s knowledge change through (1) face-to-face programming, (2) print, and (3) social media. Each approach has unique considerations for teaching and learning across areas of content, which are discussed below.

Face-to-Face

Many methods exist for engaging learners in person, and each uses a different approach to disseminating research. Clientele and subject matter will largely drive the type of face-to-face instruction. While many of the same teaching strategies for formal education can be applied in the nonformal educational setting, it is important to note the differences. For example, in most Extension programming, you will not assign homework and will not be giving graded assignments. Also, your learners need to be engaged with real-world relevance—this should also happen in a formal education setting, but sometimes this connection is forgotten. Learners also bring their own lived experiences and expertise into the learning environment. Many different strategies can be implemented and each has a different educational approach.

The in-person strategies vary from one-on-one training or consulting to large format training, to groups of learners co-developing knowledge, or applied hands-on demonstrations. You will notice that each of these teaching and learning modes connect to the theoretical constructs of learning in table 10.1.

Direct client support, such as technical assistance, is a large component of Extension specialists’ responsibilities. Stakeholder needs can vary with program area or content. Often, in specific circumstances, specialists may visit clients at their operations to assist directly with troubleshooting, system improvement, pilot testing, or optimizing methods. Extension has a rich history of disseminating information and teaching best practices to the stakeholders they serve. Each discipline may have a different approach or structure for assisting clients. Client assistance is largely dependent on the client’s current state and needs. As an example, food science (family and consumer sciences) provides a wide array of services to clientele including food safety consultation on process deviations, interpretation of laws, labeling review, educational information, shelf-life information, product analysis, food safety training, and meeting the requirements for processing and selling food.

The work of Extension provides an opportunity for educating and connecting with all of society in a state and/or local region rather than solely those connected to higher education. It is important to develop Extension programs and supporting materials that are inclusive of the broad range of human experiences, cultures, resources, and identities, and to be sensitive to the systemic disadvantage that many groups have experienced (Farella, Moore, et al., 2021). We should strive to remember that programs which have historically been offered by the Extension Service were designed to cater to the needs of the majority, and that we have a responsibility to design—or redesign—our Extension programs to be equitable and meet the needs of everyone (Farella, Hauser et al., 2021; Fields, 2020). Careful assessment of the needs of the communities we serve and, in many cases, further understanding for ourselves as educators, are required to develop inclusive, accessible, and culturally sensitive programming.

Extension provides services such as seminars, training, continuing education, and certifications for clients ranging from producers to general public interest. Extension has and provides the subject matter experts to deliver these training and educational opportunities in diverse content areas. Further, Extension often has a public reputation for disseminating reliable information without bias. Training may be presented in collaboration with state and/or federal regulatory agencies or may be provided to meet regulatory standards and requirements outlined by governing agencies. For example, American National Standards Institute (ANSI) certification (e.g. ServSafe, Safe Plates), Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs), related certifications of Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), and Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) trainings and certifications are required by regulatory agencies depending on the sector of the industry. In agriculture, Extension educators deliver programs which provide continuing education credits for pesticide applicators and programs like Beef Quality Assurance for livestock producers. Extension specialists and personnel/agents often offer these training and certifications as part of their programmatic planning in a way to serve stakeholders. Extension trainers may need additional training and experience to certify participants and lead state training sessions.

Similar to research collaborations, Extension educators also collaborate with colleagues in other states, counties, departments, and universities to diversify and expand programmatic efforts to a wider audience. Expertise among state Extension systems can vary and collaboration allows for better programming that serves both stakeholders and Extension educators. and Additionally, within the university, course collaborations are useful as clients may need topic diversity. Generally, entrepreneur series include speakers from across departments (i.e., varied subject areas) as well as topics to provide a general introduction to the subjects.

Using the Food industry as an example, subject matter experts represent agricultural economics, government/regulatory agencies, marketing, food safety, and business (Crist & Canales, 2020). These programs provide stakeholders a foundation of information as well as contacts in the event they need further assistance in that specific subject area. Recently, Extension program delivery has shifted toward using more online educational platforms, certification programs, expert happy hours, and “lunch and learn” series in order for stakeholders to access the information they need as well as provide a forum for questions.

Extension specialists–faculty with a content area focus– can provide programmatic and subject matter competency in-service opportunities and training to Extension agents–county-based Extension professionals. Inservice training is considered continuing education and an opportunity to increase subject matter competency. Further, agents select the programs that they will deliver in the county. Specialists provide in-service training to agents so they may deliver these programs as intended and/or provide additional insight to the execution of the program. Inservice opportunities can include many topics and range in subject matter from youth development to agriculture and natural resources. Further, inservice training is provided throughout the year and on different education platforms including webinars, face-to-face training or lectures, and online platforms.

Syllabus Development

As Extension educators, it is important to make connections for students in traditional education to career paths and opportunities. As a group, Extension educators need to advocate and share their stories and passion with audiences that may not be familiar with the unique career opportunities of Extension, as most will associate higher education with the pillars of research and teaching. Some students may be familiar with part of Extension either through 4-H involvement or by having parents who were involved in educational offerings (e.g., master gardener). You can strengthen the connection of careers in Extension by incorporating assignments, presentations, and curriculum development into courses. Additionally, your institution may have Extension apprenticeship programs. These types of programs can be a valuable opportunity for students to learn more about the day-to-day Extension roles while at the same time impacting their communities. Integrating some of our communication pathways into syllabi or student experiences will expose them to the multifaceted world of Extension.

Community of Practice

The Communities of Practice (CoP) framework is constructed from the exchange of a group of people who have a shared interest and want to improve on that interest using regular interactions with each other to accomplish that development (Wenger, 1998). Lave and Wenger (1991) introduced CoP to provide a template for examining the learning that happens among practitioners in a social environment comprising both novices and experts. Newcomers use this exchange between these populations to create a professional identity. Wenger (1998) then advanced the focus of CoP to personal growth and the trajectory of individuals’ participation within a group (i.e., peripheral versus core participation). No matter the purpose of educational outcome, CoPs can be designed intentionally, fostered informally, or identified after they have developed organically. A CoP can also be an outcome from learning experiences (Elliott-Engel & Westfall-Rudd, 2018) that result from your strategy and lead to connecting people, providing a shared context, enabling dialogue, stimulating learning, capturing and diffusing existing knowledge, introducing collaborative processes, helping people organize, and generating new knowledge (Cambridge et al., 2005).

A great example of direct client support (and farm model training), as well as being the foundation of the Extension service, is boll weevil eradication. The boll weevil was an invasive insect pest that was devastating cotton crops throughout the South in the early 1900s. Seaman Knapp, who has been mentioned previously, was sent to Mississippi by the USDA to help find a solution to the boll weevil infestation. Knapp set up an experimental farm to demonstrate to growers’ methods for mitigating the boll weevil damage. The farm opportunity became the model for agricultural demonstration (Mississippi State University Extension Service, 2020; Palmer, 2014). Similar stories exist for other areas and educational formats. For example, the foundation of family and consumer sciences began with home-demonstration clubs that focused on improving nutrition and living conditions for rural families. These sessions continue today and address a variety of topics such as nutrition, cooking, health, mental health, financial literacy, volunteer programs, and home-based businesses (Mississippi State University Extension Service, 2020).

Print Communications

Print media is an important form of education delivery we often think of as andragogy rather than pedagogy. Most, if not all of us, have heard the phrase “publish or perish” in reference to faculty roles. This colloquialism emphasizes that print formats of education are highly valued in the academe. Yet, not all forms of print publication are equivalent or have the same credibility (e.g., burden of peer review), and thus their value is weighted differently by the institution’s Promotion and Tenure review board.

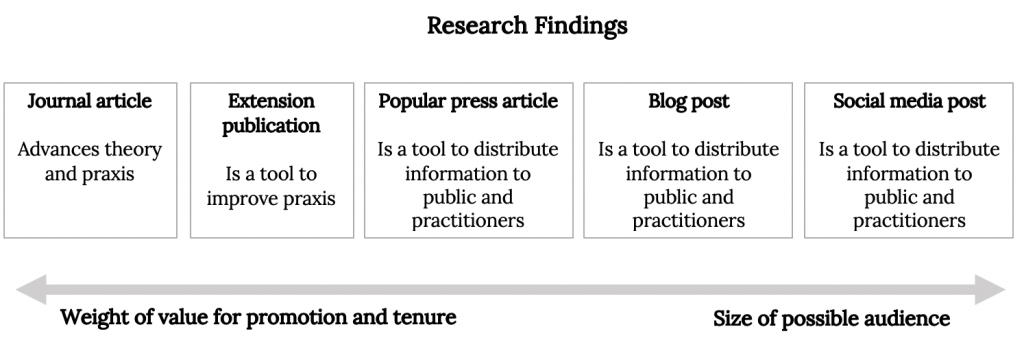

A successful Extension educator should formulate a plan of distribution that includes each level of communication. Figure 10.2 provides a framework for you to think through how you can take your research findings and translate these specific findings into all forms of print communication. An Extension educator should provide multiple communication formats to ensure that the research done on campus is communicated to the citizens of the state they serve.

It is unfortunate that social media and electronic options give the greatest reach for distributing research findings to a large audience and yet are weighted the least. Social media and other digital forms of publication are hard to evaluate for impact as well as implementation and/or behavior change. It would be easy to become hyperfocused on submitting publications to journals with a high-impact factor because that is what is favored for promotion. Yet, in Extension, we must ask, what is the value of creating new knowledge if it stays within the walls of the ivory tower? Extension’s purpose and mission is disseminating research-based evidence to improve the lives of the stakeholders they serve.

Social Media

Social media may not be commonly viewed as a pedagogical tool or accorded traditional forms of value in academe. However, it is a tool for rapidly spreading knowledge and its reach is hard to ignore in current society. Social media has evolved our consumption of both information and entertainment; it has also changed our preferences on how to consume new information (Subramanian, 2018). The use of social media provides the greatest opportunity to distribute research findings to a wide audience and to affect social discourse both positively and negatively. The field of science communication is rich, filled with best practices for effective outcomes, including language, strategy, and design. We won’t address those strategies here, yet we do want to emphasize the need to use and engage with social media and to view it as a platform for teaching. (For further reading on science communication, we recommend Laura Bowater & Kay Yeoman’s Science Communication: A Practical Guide for Scientists, New York: Wiley, 2012.)

In Conclusion: Extension Is a Bridge

Extension activities should be viewed as a bridge to enhancing and expanding the reach of research-based evidence and technical information from members of academe to stakeholders in need. Faculty who hold Extension appointments should funnel energy into sharing their findings to the betterment of society. Many grants and funding opportunities require a broader impact statement, outreach, expected outcomes, and evaluation component and approach. This is where Extension professionals should shine and can use their expertise to develop methods for reaching and educating the audience where the findings will be most impactful. The “traditional” researcher may overlook this area of importance, but many funding agencies are placing higher priority on proposals that address how the grant will impact or improve the affected stakeholders. The next chapter, “Program Planning for Community Engagement and Broader Impacts,” will further discuss how to develop and translate knowledge to benefit stakeholders.

Powerful and impactful teaching is rarely confined to the classroom. The Extension system and nonformal education are valuable for early career faculty members and graduate students. We hope that you will integrate the educational approaches from nonformal educational settings into your classroom and engage your learners with issues relevant to our communities.

Not every reader will be an Extension specialist or a county-based Extension professional (a.k.a., Agent), nor will every reader even work at an LGU. However, all faculty have the motivation, if not the obligation, to share findings from your research agenda to the public. Many times this outreach is labeled as “broader impacts” (Donovan, 2019). We hope this chapter helps you see how your teaching and research can become integral to your community. If you are a graduate student seeking a position in higher-education, we hope this chapter has raised your interest in Extension education at LGUs or in developing better ways to communicate your ideas about how to bring community-relevant research and teaching to your research agenda.

If you are reading this while working or studying at a LGU institution we hope this chapter has raised your awareness of the mission of your institution, and that you will seek out Extension professionals to help you in your teaching, research, and outreach efforts. If you do become an Extension specialist, or a county-based 4-H professional, congratulations! You are in for a challenging and rewarding career. We hope this chapter serves as a framework for conducting excellent Extension education programming and provides a greater awareness of the organization’s beginnings, the theory that frames the work, and some basic practices of non-formal education that you can use to maximize community outreach efforts.

Reflection Questions

- When you think about your research and teaching, what public issues do you see yourself ready to contribute solutions and education?

- After reviewing Figure 2, how are you using an array of mediums to share content? Where can you improve your efforts?

Allen, W.R., & Jewell, J.O. (2002). A Backward Glance Forward: Past, Present and Future Perspectives on Historically Black Colleges and Universities. The Review of Higher Education 25(3), 241-261. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2002.0007 .

Balakrishnan, S. (2021). The Adult Learner in Higher Education: A Critical Review of Theories and Applications. In I. Management Association (Eds.), Research Anthology on Adult Education and the Development of Lifelong Learners (pp. 34-47). IGI Global. http://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-8598-6.ch002 .

Baughman, S., Boyd, H. H., & Franz, N. K. (2012). Non-formal educator use of evaluation results. Evaluation and Program Planning , 35(3), 329-336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.11.008 .

Bonnen, J. T. (1998). The land grant idea and the evolving outreach university. In R. Lerner, & L. A. K. Simon (Eds.), University-Community Collaborations for the Twenty-First Century (pp. 25–70). Garland Publishing.

Cambridge, D., Kaplan, S., & Suter, V. (2005). Community of Practice Design Guide: A Step by-Step Guide for Designing & Cultivating Communities of Practice in Higher Education . EDUCAUSE. https://library.educause.edu/resources/2005/1/community-of-practice-design-guide-a-stepbystep-guide-for-designing-cultivating-communities-of-practice-in-higher-education .

Comer, M. M., Campbell, T., Edwards, K., & Hillison, J. (2006). Cooperative Extension and the 1890 land-grant institution: The real story. Journal of Extension , 44(3), Article 3FEA4. https://www.joe.org/joe/2006june/a4.php .

Coombs, P. (1976). Non-formal education: Myths, realities, and opportunities. Comparative Education Review , 20(3), 281-293. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1187481 .

Crist, C., & Canales, E. (2020). Multidisciplinary program approach to building food and business skills for agricultural entrepreneurs. Journal of Extension , 58(3). https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/joe/vol58/iss3/12 .

DePauw, K. P, & McNamee, M. (2006). The new responsibility for state and land grant universities. In A. C. Nelson, B. L. Allen, & D. L. Trauger (Eds.), Toward a Resilient Metropolis . Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech.

Duemer, L. S. (2007). The agricultural education origins of the Morrill Land Grant Act of 1862. American Educational History Journal , 34(1), 135–146. http://www.infoagepub.com/index.php?id=11&s=s4671eb77329b1 .

Elliott-Engel, J. (2018). State Administrators’ Perceptions of the Environmental Challenges of Cooperative Extension and the 4-H Program and Their Resulting Adaptive Leadership Behaviors [Doctoral dissertation, Virginia Tech]. VTechWorks. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/98002 .

Elliott-Engel, J., & Westfall-Rudd, D. (2018). Preparing future CALS professors for improved teaching: A qualitative evaluation of a cohort based program. NACTA Journal , 62(3), 229-236. https://www.nactateachers.org/index.php/volume-62-number-3-september-2018/2769-secondary-agriculture-science-teachers .

Elliott-Engel, J., Westfall-Rudd, D. M., Seibel, M., & Kaufman, E. (2020). Extension’s response to the change in public value: Considerations for ensuring the Cooperative Extension System’s financial security. Journal of Human Sciences and Extension , 8(2), 69-90. https://www.jhseonline.com/article/view/868 .

Etling, A. (1993). What is non-formal education? Journal of Agricultural Education , 34(4), 72-76. doi: 10.5032/jae.1993.04072 .

Farella, J., Hauser, M., Parrott, A., Moore, J. D., Penrod, M., & Elliott-Engel, J. (2021). 4-H Youth Development Programming in Indigenous Communities: A Critical Review of Cooperative Extension Literature. The Journal of Extension , 59(3), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.34068/joe.59.03.07 .

Farella, J., Moore, J., Arias, J., & Elliott-Engel, J. (2021). Framing Indigenous Identity Inclusion in Positive Youth Development: Proclaimed Ignorance, Partial Vacuum, and the Peoplehood Model. Journal of Youth Development , 16(4), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2021.1059 .

Fields, N. I. (2020). Exploring the 4-H Thriving Model: A Commentary Through an Equity Lens. Journal of Youth Development , 15(6), 171-194. https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2020.1058 .

Fordham, P. (1979) The interaction of formal and non-formal education. Studies in Adult Education , 11(1), 1-11. doi: 10.1080/02660830.1979.11730384 .

Ilvento, T. W. (1997). Expanding the role and function of the Extension system in the university setting. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review , 26, 153–165. doi: 10.1017/S1068280500002628 .

Jackson, D. G., & Johnson, L. (1999). When to look a gift horse in the mouth. Journal of Extension . 37(4), Article 4COM2. https://www.joe.org/joe/1999august/comm2.php .

Jones, G. E., & Garforth, C. (1997). The History, Development, and Future of Agricultural Extension. Improving Agricultural Extension: A Reference Manual . FAO.

Knoblauch, H. C., Law, E. M., & Meyer, W. P. (1962). State agricultural experiment stations: A history of research policy and procedure (No. 904). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Knowles, M. S., Swanson, R. A., & Holton, E. F. III (2005). The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development (6th ed.). Elsevier.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation . Cambridge University Press.

Lee, G. G. (1963). The Morrill Act and education. British Journal of Educational Studies , 12(1), 19–40. doi: 10.1080/00071005.1963.9973102 .

Lee, J. M., & Keys, S. W. (2013). Land-grant but unequal: State one-to-one match funding for 1890 land-grant universities. APLU Office of Access and Success publication , (3000-PB1).

Meena, D. K., Meena, N. R., & Sharma, S. (2019). Fundamentals of Human Ethics and Agriculture Extension . Scientific Publishers.

Merriam, S. B. (2008). Adult learning theory for the twenty‐first century. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education , 2008(119), 93-98. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.309.

Mississippi State University Extension Service. (2020). About Extension. Retrieved from: http://Extension.msstate.edu/about-Extension .

Morrill Land-Grant Act. (1862). U.S. Statutes at Large, 12 503.

Morse, G. W. (2009). Extension’s Money and Mission Crisis: The Minnesota response. iUniverse.

Okojie, M. C. P. O., & Sun, Y. (2020). Foundations of adult education, learning characteristics, and instructional strategies. In M. C. P. O. Okojie & T. C. Boulder (Eds). Handbook of Research on Adult Learning in Higher Education (pp. 1-33). IGI Global. https://www.igi-global.com/book/handbook-research-adult-learning-higher/232294 .

Palmer, D. 2014. Boll Weevils and Beyond: Extension Entomology [Blog]. Retrieved from: http://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/ifascomm/2014/05/19/boll-weevils-and-beyond-Extension-entomology/ .

Peters, S. J. (1996). Extension and the Democratic Promise of the Land Grant Idea . University of Minnesota Extension Service and Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs.

Provasnik, S., Shafer, L. L., & Snyder, T. D. (2004). Historically black colleges and universities, 1976-2001 (No. NCSE 2004 062). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Rasmussen, W. D. (1989). Taking the University to the People: Seventy-Five Years of Cooperative Extension . Iowa State University Press.

Redd, K. E. (1998). Historically black colleges and universities: Making a comeback. New Directions for Higher Education , 26(2), 33-43. doi: 10.1002/he.10203 .

Roebuck, J., & Murty, K. (1993). Historically Black Colleges and Universities: Their Place in American Higher Education . Praeger Publishers.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations (5th Ed.). Simon and Schuster.

Rogers, E. M. (1988). The intellectual foundation and history of the agricultural Extension model. Science Communication , 9(4), 492–510. doi: 10.1177/0164025988009004003 .

Rosenberg, G. (2015). The 4-H Harvest: Sexuality and the State in Rural America . University of Pennsylvania Press.

Seevers, B., Graham, D., & Conklin, N. (2007). Education Through Cooperative Extension (2nd ed.). Delmar Publishers.

Selznick, P. (2011). TVA and the Grass Roots . Quid Pro Books.

Shinn, G. C., Wingenbach, G. J., Lindner, J. R., Briers, G. E., & Baker, M. (2009). Redefining agricultural and Extension education as a field of study: Consensus of fifteen engaged international scholars. Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education , 16(1), 73-88. https://www.aiaee.org/attachments/101_Shinn-Redefining-Vol-16.1%20e-6.pdf .

Simon, J. Y. (1963). The politics of the Morrill Act. Agricultural History , 37(2), 103–111.

Smith-Lever of 1914, 7 U.S.C. 341 et. seq. (1914).

Stephenson, M. (2011). Conceiving land grant university community engagement as adaptive leadership. Higher Education , 61(1), 95–108. doi: 10.1007/s10734-010-9328-4 .

Subramanian, K. R. (2018). Myth and mystery of shrinking attention span. International Journal of Trend in Research and Development , 5(1). http://www.ijtrd.com/papers/IJTRD16531.pdf .

U.S. Department of Agriculture-National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA-NIFA). (2015). The 1994 Land-Grant Institutions: Standing on Tradition, Embracing the Future. USDA- NIFA. https://nifa.usda.gov/sites/default/files/resource/1994%20LGU%20Anniversary%20Pub%20WEB_0.pdf .

Vines, K. (2017). Engagement through Extension: Toward Understanding Meaning and Practiceamong Educators in Two State Extension Systems [Doctoral dissertation], The Pennsylvania State University. https://etda.libraries.psu.edu/catalog/13816kav11 .

Wenger, E. (1998) Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity . Cambridge University Press.

Wessel, T. R. & Wessel, M. (1982). 4-H: An American Idea, 1900–1980: A History of 4-H[USA] . National 4-H Council.

Whitacre, B. E. (2018). Extension’s role in bridging the broadband digital divide: focus on supply or demand? Journal of Extension , 46(3), Article 3RIB2. https://joe.org/joe/2008june/rb2.php .

Williamson, K. (2002). The beginning stages of research. In K. Williamson, A. Bow, F. Burstein, P. Darke, R. Harvey, G. Johanson, S. McKemmish, M. Oosthuizen, S. Saule, D. Schauder, G. Shanks, & K. Tanner (Eds.), In Topics in Australasian Library and Information Studies, Research Methods for Students, Academics and Professionals (2nd ed.), (pp. 49-66). Chandos Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-876938-42-0.50010-1 .

Figure and Table Attributions

- Figure 10.1 Adapted under fair use from USDA NIFA 2019. Graphic by Kindred Grey.

- Figure 10.2 Kindred Grey. CC BY 4.0.

- Table 10.1 adapted from Balakrishnan, S. (2020). The adult learner in higher education: A critical review of theories and applications. In Accessibility and Diversity in the 21st Century University (pp. 250-263). IGI Global. doi: 10.4018/978-1-7998-2783-2.ch013

- How to cite this book chapter: Elliott-Engel, J., Crist, C., and James, G. 2022. The Power of Extension: Research, Teaching, and Outreach for Broader Impacts. In: Westfall-Rudd, D., Vengrin, C., and Elliott-Engel, J. (eds.) Teaching in the University: Learning from Graduate Students and Early-Career Faculty . Blacksburg: Virginia Tech College of Agriculture and Life Sciences . https://doi.org/10.21061/universityteaching License: CC BY-NC 4.0. ↵

Teaching in the University Copyright © 2022 by Jeremy Elliott-Engel; Courtney Crist; and Gordon Jones is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

About Grants

The lifecycle of grants and cooperative agreements consists of four phases: Pre-Award, Award, Post-Award, and Close Out.

Access to Data

The National Institute of Food and Agriculture is committed to serving its stakeholders, Congress, and the public by using new technologies to advance greater openness.

Access Data Gateway

The Data Gateway enables users to find funding data, metrics, and information about research, education, and extension projects that have received grant awards from NIFA.

View Resources Page

This website houses a large volume of supporting materials. In this section, you can search the wide range of documents, videos, and other resources.

Featured Webinar

Second annual virtual grants support technical assistance workshop.

Check out this five-day workshop in March 2024 workshop, designed to help you learn about NIFA grants and resources for grants development and management.

The National Institute of Food and Agriculture provides leadership and funding for programs that advance agriculture-related sciences.

Extension provides non-formal education and learning activities to people throughout the country — to farmers and other residents of rural communities as well as to people living in urban areas. It emphasizes taking knowledge gained through research and education and bringing it directly to the people to create positive changes.

All universities engage in research and teaching, but the nation's more than 100 land-grant colleges and universities have a third, critical mission — extension. Through extension, land-grant colleges and universities bring vital, practical information to agricultural producers, small business owners, consumers, families, and young people.

NIFA supports both universities and local offices of the Cooperative Extension System (CES) to provide research-based information to its range of audiences. As the CES federal partner, NIFA plays a key role in the mission by distributing annual congressionally appropriated formula grants to supplement state and county funds.

Improving Lives in Rural and Urban Areas

The hallmarks of the extension program — openness, accessibility, and service — illuminate how cooperative extension brings evidence-based science and modern technologies to farmers, consumers, and families. Through extension, land-grant institutions reach out to offer their resources to address public needs. By educating farmers on business operations and on modern agricultural science and technologies, extension contributes to the success of countless farms, ranches, and rural business. Further, these services improve the lives of consumers and families through nutrition education, food safety training, and youth leadership development.

Past, Present, and Future

In 2014, NIFA and our land-grant university partners celebrated 100 years of Cooperative Extension in the United States. The Smith-Lever Act formalized extension in 1914, but its roots go back to agricultural clubs and societies of the early 1800s. The act expanded USDA's partnership with land-grant universities to apply research and provide education in agriculture. Over the last century, extension has adapted to changing times and landscapes, and it continues to address a wide range of human, plant, and animal needs in both urban and rural areas. Today, extension works to:

- Translate science for practical application

- Identify emerging research questions, find answers and encourage application of science and technology to improve agricultural, economic, and social conditions

- Prepare people to break the cycle of poverty, encourage healthful lifestyles, and prepare youth for responsible adulthood

- Provide rapid response regarding disasters and emergencies

- Connect people to information and assistance available online through eXtension.org

The nation’s transformation from a manufacturing to an information society raises questions as to how to best reach an intended audience. Extension educators use modern technology to disseminate knowledge and tools but also rely on traditional human values and relationships to gain the attention and trust from the people they serve. As residents of the communities in which they work, local extension agents bring credibility to their roles as educators.

High-Impact Outcome

Tomorrow’s Agricultural and Natural Resource Workforce

Experiential learning is a great way to promote youth interest in adopting science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) in their future careers. NIFA-supported 4-H programs touch over 6 million children across the country every year. Several projects supported by NIFA Smith-Lever funds and special funding from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service taught youth to learn and apply Geographic Information Systems mapping skills that support wildlife refuge systems from the Caribbean to the Pacific, Maine to Alaska. For example, youth in Iowa tested the effectiveness of mapping using iPhones compared with Global Positioning System units. This learning experience allowed them to map features such as fences, invasive species, oak stands, and areas that need attention to conserve wildlife. Similarly, a project in Minnesota engaged teens on the White Earth Indian Reservation to conduct golden-winged warbler habitat and nesting cover mapping at the Tamarac Refuge. Such experiences help youth develop science skills and learn skills necessary for future employment.

Latest Updates

- Latest Funding Opportunities

- Latest Blogs

- Latest Impacts

funding opportunity

Tribal colleges extension program: special emphasis, new beginning for tribal students program, research facilities act program, nifa funded projects help strengthen maui community, nifa’s frsan connects farmers and ranchers to stress assistance programs, nifa invests over $6m in commodity board research topics (afri a1811), nifa funding helps veterinary clinic better serve large animal clients, veterinary diagnostic laboratory scientists develop tool to rapidly detect devastating swine disease, your feedback is important to us..

Your Article Library

Extension: concept and need | education.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

After reading this article you will learn about:- 1. Concept of Extension 2. Need for Extension 3. Levels of Extension 4. The Philosophy of Extension 5. Objectives of Extension 6. Function of Extension 7. The Extension Educational Process 8. Principles of Extension 9. Cyber Extension 10. Motivation in Extension 11. Extension Agent as a Democratic Group Leader and Other Details .

- Future Challenges for Extension

1. Concept of Extension:

The use of the term ‘extension’ originated in England in 1866 with a system of university extension which was taken up first by Cambridge and Oxford Universities, and later by other educational institutions in England and in other countries.

The term ‘extension education’ was first used in 1873 by Cambridge University to describe this particular educational innovation. The objective of university extension was to take the educational advantages of universities to ordinary people.

Historically, extension has meant education in agriculture and in home economics for rural people. This education is practical, aimed at improving farm and home.

According to Ensminger (1957) extension is education and that its purpose is to change attitudes and practices of the people with whom the work is done.

Leagans (1961) conceptualized extension education as an applied science consisting of content derived from research, accumulated field experiences and relevant principles drawn from the behavioural sciences synthesized with useful technology into a body of philosophy, principles, content and methods focused on the problems of out-of-school education for adults and youth.

The National Commission on Agriculture (1976) refers to extension as an out-of-school education and services for the members of the farm family and others directly or indirectly engaged in farm production, to enable them to adopt improved practices in production, management, conservation and marketing.

The National Commission further stated that, agricultural extension is not only imparting knowledge and securing adoption of a particular improved practice but also aims at changing the outlook of the farmers to the point where they will be receptive to, and on their own initiative, continuously seek means of improving their farm occupation, home and family life in totality.

In addition to practising in the field, extension is formally taught in colleges and universities leading to the award of degrees. Research is also carried out in extension. What is unique for extension is the application of the knowledge of this discipline in socioeconomic transformation of the rural communities.

In this context, Extension may be defined as the science of developing capability of the people for sustainable improvement in their quality of life. The main aim of extension is human resource development.

The concept of extension is based on the following basic premises. Following Hassanullah (1995), these are :

1. People have unlimited potential for personal growth and development.

2. The development may take place at any stage of their lives, if they are provided with adequate and appropriate learning opportunities.

3. Adults are not interested in learning only for the sake of learning. They are motivated when new learning provides opportunity for application, for increased productivity and improved standards of living.

4. Such learning is a continuous need of rural populations and should be provided on a continuing basis, because the problems as well as the technologies of production and living are continuously changing.

5. Given the required knowledge and skills, people are capable of making optimal choices for their individual and social benefits.

2. Need for Extension :

The need for extension arises out of the fact that the condition of the rural people in general, and the farm people in particular, has got to be improved. There is a gap between what is-the actual situation and what ought to be-the desirable situation. This gap has to be narrowed down by the application of science and technology in their enterprises and bringing appropriate changes in their behaviour.

According to Supe (1987), the researchers neither have the time nor are they equipped for the job of persuading the villagers to adopt scientific methods, and to ascertain from them the’ rural problems.

Similarly, it is difficult for all the farmers to visit the research stations and obtain firsthand information. Thus, there is need for an agency to interpret the findings of research to the farmers and to carry the problems of the farmers to research for solution. This gap is filled by the extension agency.

3. Levels of Extension :

Extension is generally thought of at two levels, extension education and extension service. Extension at these two levels are interrelated, but at the same time maintain their separate identity. Extension Education-The extension education role is generally performed by the higher learning institutions like the Agricultural and other Universities and Colleges, ICAR Institutes, Home Science Colleges and apex level Training and Extension Organizations.

At the university level, extension is integrated with teaching and research, while at the research institutes, extension is integrated with research. At the other apex level organizations, extension is generally integrated with training in extension.

The extension education function of these institutions and organizations is to educate, train and develop professionals for teaching and research in extension and for the extension service, and also to develop methodology for research in extension and field extension work. The field extension work of these institutions and organizations is generally limited to the neighbouring villages or blocks, which are considered as their extension laboratories.

Extension Service-It is mainly to provide educational service to the people according to their need, for improving their life through better working. The main responsibility of extension service is with the State Government. The departments of Agriculture, Horticulture, Animal Husbandry, Veterinary, Forestry, Fishery, Sericulture etc. of the State Government carry out extension work with the farmers and rural people over the entire State.

The departments maintain close contact with the relevant Universities and Research Institutes for obtaining appropriate technology and methodology for extension work, and for providing them with feedback information from the field for research.

The extension service provided by the departments of the State Government is location-specific, input-intensive and, target and result oriented. The extension service works in close coordination with other development departments, input supply agencies, credit institutions, voluntary organizations and Panchayats.

The extension service has the main responsibility of educating and training the farmers, farm women, and rural youth and village leaders of the State and for this purpose they take the help of the universities, research institutes and, training and extension organizations.

Two more trends in extension service are gaining ground in India. These are, decentralization of extension through closer coordination with Panchayats (Local Self- Government), and privatization of extension through increased private sector participation.

4. The Philosophy of Extension :

Philosophy is the pursuit of wisdom, a body of general principles or laws of a field of knowledge. Essentially philosophy is a view of life and its various components. The practical implication is that the philosophy of a particular discipline would furnish the principles or guidelines with which to shape or mould the programmes or activities relating to that discipline.

According to Kelsey and Hearne (1967), the basic philosophy of extension education is to teach people how to think, not what to think. Extension’s specific job is furnishing the inspiration, supplying specific advice and technical help, and counseling to see that the people as individuals, families, groups and communities work together as a unit in ‘blueprinting’ their own problems, charting their own courses, and that they launch forth to achieve their objectives. Sound extension philosophy is always forward looking.

5. Objectives of Extension :

Objectives are expression of the ends towards which our efforts are directed. The fundamental objective of extension is to develop the rural people economically, socially and culturally by means of education.

More specifically, the objectives of extension are:

1. To assist people to discover and analyze their problems and identify the felt needs.

2. To develop leadership among people and help them in organizing groups to solve their problems.

3. To disseminate research information of economic and practical importance in a way people would be able to understand and use.

4. To assist people in mobilizing and utilizing the resources which they have and which they need from outside.

5. To collect and transmit feedback information for solving management problems.

6. Function of Extension :

The function of extension is to bring about desirable changes in human behaviour by means of education. Changes may be brought about in their knowledge, skill, attitude, understanding, goals, action and confidence.

Change in knowledge means change in what people know. For example, farmers who did not know of a recent HYV crop came to know of it through participation in extension programmes. The Extension Agents (EAs) who did not know of Information Technology (IT) came to know of them after attending a training course.

Change in skill is change in the technique of doing things. The farmers learnt the technique of growing the HYV crop which they did not know earlier. The EAs learnt the skill of using IT.

Change in attitude involves change in the feeling or reaction towards certain things. The farmers developed a favourable attitude towards the HYV crop. The EAs developed a favourable feeling about the use of IT in extension programme.

Change in understanding means change in comprehension. The farmers realized the importance of the HYV crop in their farming system and the extent to which it was economically profitable and desirable, in comparison to the existing crop variety. The EAs understood the use of IT and the extent to which these would make extension work more effective.

Change in goal is the distance in any given direction one is expected to go during a given period of time. The extent to which the farmers raised their goal in crop production, say, increasing crop yield in a particular season by five quintals per hectare by cultivating the HYV crop. The EAs set their goal of getting an improved practice adopted by the farmers within a certain period of time by using IT.

Change in action means change in performance or doing things. The farmers who did not cultivate the HYV crop earlier cultivated it. The EAs who earlier did not use IT in their extension programmes started using them.

Change in confidence involves change in self-reliance. Farmers felt sure that they have the ability of raising crop yield. The EAs developed faith on their ability to do better extension work. The development of confidence or self-reliance is the solid foundation for making progress.

To bring desirable change in behaviour is the crucial function of extension. For this purpose the extension personnel shall continuously seek new information to make extension work more effective.

The farmers and homemakers also on their own initiative shall continuously seek means of improving their farm and home. The task is difficult because millions of farm families with little education, scattered in large areas with their own beliefs, values, attitudes, resources and constraints are pursuing diverse enterprises.

7. The Extension Educational Process :

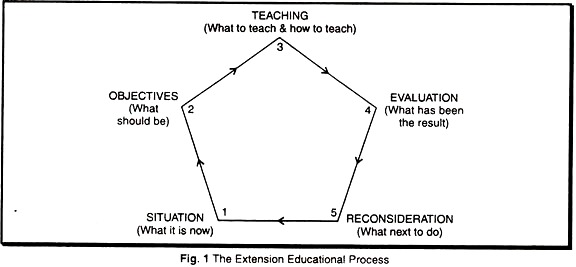

Extension education is a participatory process and involves five essential and interrelated steps. The sequence of steps is discussed on the basis of concept developed by Leagans(1967).

First Step:

The first step consists of collection of facts and analysis of the situation. Facts about the people and their enterprises; the economic, social, cultural, physical and technological environment in which they live and work. These may be obtained by appropriate survey and establishing rapport with the people.

The responses obtained are to be analyzed with the local people to identify the problems and resources available in the community. For example, after a survey in a community and analysis of the data, the problem was identified as low income of the farm family from their crop production enterprise.

Second Step:

The next step is deciding on realistic objectives which may be accomplished by the community. A limited number of objectives should be selected by involving the local people. The objectives should be specific and clearly stated, and on completion should bring satisfaction to the community. Objectives should state the behavioural changes in people as well as economic and social outcomes desired.

In the example, the problem was identified as low income from crop production enterprise. A deeper probe into the data revealed that low income was due to low yield of crops, which was attributed to the use of local seeds with low yield potential, application of little fertilizer and lack of protection measures.

By taking into consideration the capacity and competency of the people in the community and the availability of resources, the objective was set up to increase the crop yield by 20 percent within a certain period of time. It was estimated that the increased yield shall bring increased income, which shall enhance the family welfare.

Third Step:

The third step is teaching, which involves choosing what should be taught (the content) and how the people should be taught (the methods and aids to be used). It requires selecting research findings of economic and practical importance relevant to the community, and selection and combination of appropriate teaching methods and aids.

Based on the problems identified in the particular example, technologies like use of HYV seeds, application of fertilizer and plant protection measures were selected as teaching content. Result demonstration, method demonstration, farmers’ training and farm publications were chosen as teaching methods, and rape recorder and slides were selected as teaching aids.

Fourth Step:

The fourth step is evaluating the teaching, i.e. determining the extent to which the objectives have been reached. To evaluate the results of an educational programme objectively, it is desirable to conduct a re-survey. The evidence of changed behaviour should be collected, which shall not only provide a measure of success, but shall also indicate the deficiencies, if any.

In the example, the re-survey after the fixed period of time, indicated that the crop yield had increased by 10 percent. It, therefore, indicated that there was a gap of 10 percent in crop yield in comparison to the target (objective) of 20 percent fixed earlier.

The re-survey also indicated that there had been two important deficiencies in carrying out the extension educational programme, such as, there was lack of proper water management and the farmers could not apply the fertilizer and plant protection measures as per recommendation due to lack of funds.

Fifth Step:

The fifth step is re-consideration of the entire extension educational programme on the light of the results of evaluation. The problems identified in the process of evaluation may become the starting point for the next phase of the extension educational programme, unless new problems have developed or new situations have arisen.

After re-consideration of the results of evaluation with the people, the following teaching objectives were again set up. For example, these were, training the farmers on proper water management practices and putting up demonstrations on water management.

The people were also advised to contact the banks for obtaining production credit in time to purchase the critical inputs. Thus, the continuous process of extension education shall go on, resulting in progress of the people from a less desirable to a more desirable situation.

8. Principles of Extension :

Principles are generalized guidelines which form the basis for decision and action in a consistent way. The universal truth in extension which have been observed and found to hold good under varying conditions and circumstances are presented.

1. Principle of Cultural Difference:

Culture simply means social heritage. There is cultural difference between the extension agents and the farmers. Differences exist between groups of farmers also. The differences may be in their habits, customs, values, attitudes and way of life. Extension work, to be successful, must be carried out in harmony with the cultural pattern of the people.

2. Grass Roots Principle:

Extension programmes should start with local groups, local situations and local problems. It must fit to the local conditions. Extension work should start with where people are and what they have. Change should start from the existing Situation.

3. Principle of Indigenous Knowledge:

People everywhere have indigenous knowledge systems which they have developed through generations of work experience and problem solving in their own specific situations. The indigenous knowledge systems encompass all aspects of life and people consider it essential for their survival.

Instead of ignoring the indigenous knowledge systems as outdated, the extension agent should try to understand them and their ramifications in the life of the people, before proceeding to recommend something new to them.

4. Principle of Interests and Needs:

People’s interests and people’s needs are the starting points of extension work. To identify the real needs and interests of the people are challenging tasks. The extension agents should not pass on their own needs and interests as those of the people. Extension work shall be successful only when it is based on the interests and needs of the people as they see them.

5. Principle of Learning by Doing:

Learning remains far from perfect, unless people get involved in actually doing the work. Learning by doing is most effective in changing people’s behaviour. This develops confidence as it involves maximum number of sensory organs. People should learn what to do, why to do, how to do and with what result.

6. Principle of Participation:

Most people of the village community should willingly cooperate and participate in identifying the problems, planning of projects for solving the problems and implementing the projects in getting the desired results. It has been the experience of many countries that people become dynamic if they take decisions concerning their own affairs, exercise responsibility for, and are helped to carry out projects in their own areas.

The participation of the people is of fundamental importance for the success of an extension programme. People must share in developing and implementing the programme and feel that it is their own programme.

7. Family Principle:

Family is the primary unit of society. The target for extension work should, therefore, be the family. That is, developing the family as a whole, economically and socially. Not only the farmers, the farm women and farm youth are also to be involved in extension programmes.

8. Principle of Leadership:

Identifying different types of leaders and working through them is essential in extension. Local leaders are the custodians of local thought and action. The involvement of local leaders and legitimization by them are essential for the success of a programme.

Leadership traits are to be developed in the people so that they of their own shall seek change from less desirable to more desirable situation. The leaders may be trained and developed to act as carriers of change in the villages.

9. Principle of Adaptability:

Extension work and extension teaching methods must be flexible and adapted to suit the local conditions. This is necessary because the people, their situation, their resources and constraints vary from place to place and time to time.

10. Principle of Satisfaction:

The end product of extension work should produce satisfying results for the people. Satisfying results reinforce learning and motivate people to seek further improvement.

11. Principle of Evaluation:

Evaluation prevents stagnation. There should be a continuous built-in method of finding out the extent to which the results obtained are in agreement with the objectives fixed earlier. Evaluation should indicate the gaps and steps to be taken for further improvement.

9. Cyber Extension :

CYBER EXTENSION (also known as e-extension) may be defined as extension over the cyber space, the imaginary space created by the interconnected telecommunication and computer networks. It means using the power of online networks, computer communications and digital interactive multimedia to facilitate dissemination of farm information.

Cyber extension includes effective use of information and communication technology, national and international information networks, the Internet, Expert Systems, Multimedia Learning Systems and computer based training systems, to improve information access to the farmers, extension workers, research scientists and extension managers.

The cyber extension naturally, cannot and will not eliminate all the problems of traditional extension. And in most cases, cyber extension will complement the traditional extension. It will both add to and subtract from today’s extension methodology. It will add more interactivity. It will add speed. It will add two-way communication.

It will add to wider range and also more in-depth messaging. It will widen the scope of extension; it will also improve quality. It will subtract costs and reduce time. It will reduce dependency on so many actors in the chain of extension system, and frankly it will change the whole method of extension in coming decades.

It will bring new information services to rural areas which farmers, as users, will have much greater control than over current information channels. Even if every farmer does not have a computer terminal, these could become readily available at local information resource centres, with computers carrying expert systems to help farmers to make decisions.

However, it will not make extension worker redundant. Rather, they will be able to concentrate on tasks and services where human interaction is essential-in helping farmers individually and in small groups to diagnose problems, to interpret data, and to apply their meaning.

10. Motivation in Extension :

Motivation means movement or motion, an inner state that energizes, activates or moves and directs human behaviour towards goals. It is a need satisfying and goal seeking behaviour. Motivation is a generalized term which includes drives, desires, needs, and similar forces.

Motivation may generate at two levels. The motivations which generate from within one’s own self are known as intrinsic motivation. For example, the satisfaction of doing good work may itself be perceived as a reward, which may motivate an individual to make better work and progress further.

Motivations which generate from an artificially induced incentive, say, award of titles like Krishi Pandit, prizes, certificates, etc., are known as extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation produces a stronger and more permanent drive in comparison to extrinsic motivation and is considered more important in extension.

The main purpose of extension work is to motivate the farm people to adopt new ideas and practices, where extension agents act as motivators. However, as human beings, not only farmers, the extension agents also need motivation.

The motivations which are more relevant for the rural people are presented, following Wilson and Gallup (1955):

1. The Desire for Security:

People are in need of economic, social, psychological and spiritual security, so that they may feel safe. The farmers may be motivated to adopt new practices by convincing them that the new practices shall increase income and employment, and enhance security of the family.

2. The Desire for New Experience:

People are attracted towards new situations, new ideas, new interests, and new ways of doing things. Extension teaching provides new knowledge, new skills, new attitudes, and satisfies a basic human desire.

3. The Desire for Response:

People cannot stay alone. They need companionship, a feeling of belongingness. Extension satisfies this need by encouraging people to work together in groups.

4. The Desire for Recognition:

Human craving for status, prestige, and being considered as important is well known. Adoption leadership builds up prestige and recognition for the people in the rural community. McClelland identified three types of basic motivating needs- need for power (n/PWR), need for affiliation (n/AFF) and need for achievement (n/ACH). All the three drives, according to Koontz and others (1984), are of special relevance to management, and hence for the change agent system.

1. Need for power:

People with a high need for power have a great concern for exercising influence and control. Such individuals generally are seeking positions of leadership ; they are forceful, outspoken, hardheaded, and demanding; and they enjoy teaching and public speaking.

2. Need for affiliation:

People with a high need for affiliation usually derive pleasure from being loved and tend to avoid the pain of being rejected by a social group. As individuals, they are likely to be concerned with maintaining pleasant social relationships, to enjoy a sense of intimacy and understanding, to be ready to console and help others in trouble, and to enjoy friendly interaction with others.

3. Need for achievement:

People with a high need for achievement have an intense desire for success and an equally intense fear of failure. They want to be challenged, set moderately difficult (but not impossible) goals for themselves, take a realistic approach to risk, prefer to assume personal responsibility to get a job done, like specific and prompt feedback on how they are doing, tend to be restless, like to work long hours, do not worry unduly about failure if it does occur, and like to run their own shows.

The two sets of motivations mentioned here are not mutually exclusive and there may be some overlapping. For example, the need for affiliation and the desire for response may convey the same meaning. Further, achievement motivation may also be relevant for farmers who are commercially oriented and have developed good managerial ability.

11. Extension Agent as a Democratic Group Leader: