- Open access

- Published: 09 July 2021

Using concept mapping to prioritize barriers to diabetes care and self-management for those who experience homelessness

- Eshleen K. Grewal 1 ,

- Rachel B. Campbell 1 ,

- Gillian L. Booth 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Kerry A. McBrien 6 , 7 ,

- Stephen W. Hwang 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Patricia O’Campo 2 , 4 , 5 &

- David J. T. Campbell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5570-3630 1 , 7 , 8

International Journal for Equity in Health volume 20 , Article number: 158 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

4429 Accesses

13 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Diabetes is a chronic medical condition which demands that patients engage in self-management to achieve optimal glycemic control and avoid severe complications. Individuals who have diabetes and are experiencing homelessness are more likely to have chronic hyperglycemia and adverse outcomes. Our objective was to collaborate with individuals experiencing homelessness and care providers to understand the barriers they face in managing diabetes, as a first step in identifying solutions for enhancing diabetes management in this population.

We recruited individuals with lived experience of homelessness and diabetes (i.e. clients; n = 32) from Toronto and health and social care providers working in the areas of diabetes and/or homelessness (i.e. providers; n = 96) from across Canada. We used concept mapping, a participatory research method, to engage participants in brainstorming barriers to diabetes management, which were subsequently categorized into clusters, using the Concept Systems Global MAX software, and rated based on their perceived impact on diabetes management. The ratings were standardized for each participant group, and the average cluster ratings for the clients and providers were compared using t-tests.

The brainstorming identified 43 unique barriers to diabetes management. The clients’ map featured 9 clusters of barriers: Challenges to getting healthy food , Inadequate income , Navigating services, Not having a place of your own , Relationships with professionals , Diabetes education , Emotional wellbeing , Competing priorities , and Weather-related issues . The providers’ map had 7 clusters: Access to healthy food , Dietary choices in the context of homelessness , Limited finances, Lack of stable, private housing , Navigating the health and social sectors , Emotional distress and competing priorities , and Mental health and addictions . The highest-rated clusters were Challenges to getting healthy food (clients) and Mental health and addictions (providers). Challenges to getting healthy food was rated significantly higher by clients ( p = 0.01) and Competing priorities was rated significantly higher by providers ( p = 0.03).

Conclusions

Experiencing homelessness poses numerous barriers to managing diabetes, the greatest of which according to clients, is challenges to getting healthy food. This study showed that the way clients and providers perceive these barriers differs considerably, which highlights the importance of including clients’ insights when assessing needs and designing effective solutions.

Diabetes mellitus is a commonly occurring chronic medical condition that is associated with a high burden of mortality and morbidity. In 2018, 34.2 million Americans, or 10.5 % of the population, had diabetes and approximately 1.5 million Americans were newly diagnosed that year [ 1 ]. The risk of mortality for people with diabetes is two times greater than it is for people without diabetes, and having diabetes can reduce life expectancy by 5–15 years [ 2 ]. Chronically high blood glucose levels can result in an increased risk of diabetes-related complications over time, which include: nerve damage, kidney disease, blindness, and vascular disease [ 3 ]. To avoid adverse outcomes, people with diabetes must make decisions about their management frequently and on an ongoing basis. There is evidence to suggest that the combination of self-management education and self-management support can result in improvements in glycemic control through improved self-care behaviours, which in turn can reduce the risk of developing complications [ 4 ]. Participation in diabetes education, therefore, is critical for improving knowledge and self-efficacy, which enables patients to engage in healthy behaviours [ 4 ]. These healthy behaviours, including smoking cessation, dietary modification, and regular physical activity, in combination with pharmacotherapy, can reduce the risk for complications such as major adverse cardiac events [ 5 ]. Other behaviours such as self-monitoring of blood glucose levels can empower patients, improve treatment adherence, and assist diabetes care professionals in making decisions about treatment [ 6 ].

Among those with diabetes, people with lived experience of homelessness (PWLEH) are more likely than the general population to have elevated blood glucose levels [ 7 ]. Homelessness is defined by a lack of stable and safe housing, but it is often accompanied by inadequate income, mental and physical health problems, difficulty accessing health care and social supports, substance use disorders, previous involvement with the justice system, and adverse childhood experiences [ 8 , 9 ]. Although health issues may lead to homelessness, homelessness also greatly affects health, making it challenging for people who are experiencing homelessness to access care [ 8 , 10 ] and engage in self-management, especially when they have a chronic medical condition like diabetes, for which management is complex.

There are many barriers that can make it challenging to manage diabetes for PWLEH. Accessing health care services can involve long wait times and an appreciable amount of time may be spent travelling to and from appointments [ 11 ]. In addition to time, there is a financial burden associated with managing diabetes, as the costs of medications and blood glucose testing supplies may not be covered by public health insurance programs, even within Canada’s universal health system [ 7 , 11 , 12 ]. Barriers specific to homelessness that have been identified in the literature include concerns about food insecurity related to low-quality foods available in shelters, as well as challenges with safely storing medications and supplies, and strict shelter schedules with respect to eating meals and taking medications [ 7 , 13 ]. Travelling to appointments often involves the use of public transportation with associated costs. As many PWLEH do not have a fixed mailing address or reliable access to a phone, issues contacting patients are also common [ 8 , 14 ], making it difficult to schedule and notify patients of appointments [ 15 ]. Perceived feelings of being unwelcome in clinical settings can also prevent people who are experiencing homelessness from seeking health care services [ 16 ]. Other priorities, namely, obtaining the necessities of life (food, shelter, etc…), drug and alcohol use, and mental health or cognitive issues can also interfere with diabetes self-management [ 7 , 13 , 17 ].

While there are many barriers and challenges to diabetes management, the importance of these in relation to one another is not well known, nor is it well known if these priorities differ between providers and PWLEH. Other studies that have compared the perspectives of service users with those of service providers have found differences of opinions between the two groups [ 18 , 19 ]. One such study asking community members and service providers about which social and mental health services should be made available at a new medical clinic in the community found that community members and service providers had different views regarding which services were most needed [ 19 ]. Another study aimed to identify existing gaps in services for youth, where the opinions of the youth differed from those of the service providers regarding importance, but not in terms of ‘what to do first’ [ 18 ]. Traditionally, homeless-serving agencies have provided services based on their own beliefs about their clients’ needs instead of directly asking their clients what they need [ 20 ]. For instance, they may have focused on providing mental health and substance use services because the rates of mental illness and substance use are high among this population, or they may have prioritized housing because this population is characterized by a lack of a stable home, but those services may not address the most pressing issues for people who are experiencing homelessness [ 20 ] and may result in service gaps and barriers. The perspectives of service users, therefore, can be useful for service providers because those insights can help the providers understand how to tailor their services to better fill the gaps in service provision and remove barriers to accessing services, based on their clients’ priorities.

Given the complexity of diabetes management, myriad barriers that can affect adherence, and the potential for differences in perspectives between providers and PWLEH, we sought to collaborate with people who had lived experience of homelessness and diabetes, as well as health and social care providers who work with people experiencing homelessness and/or people with diabetes, to prioritize the challenges faced by this population in managing diabetes. The objective of this study was to determine the perceived relative impact of barriers to diabetes management and whether the perceptions about the impact of those barriers differed between providers and PWLEH.

Study design

We used a semi-quantitative, participatory methodology known as concept mapping. We used concept mapping because it can be used to create visual representations that depict the combined thoughts of a group, by integrating input from multiple people using quantitative data analysis techniques [ 21 ]. This methodology enabled us to gather insights from a group of PWLEH who have diabetes (herein referred to as the clients) and from various providers representing different areas of health and social care (herein referred to as the providers) and to quantitatively compare their collective feedback. Our study was approved by the research ethics boards of the University of Calgary and Unity Health Toronto/St. Michael’s Hospital.

Study participants & recruitment

The clients for this study were all recruited in Toronto, Ontario – Canada’s largest city and the city with the largest population of people experiencing homelessness [ 22 ]. The prevalence of diabetes among PWLEH in Toronto is thought to be similar to the prevalence among the general population [ 23 ] and barriers to managing diabetes previously identified by PWLEH in Toronto [ 7 ] are similar to the barriers identified by PWLEH in other cities [ 24 ].

Eight of the clients in this study were recruited as part of a larger community-based participatory research project designed to understand what it is like to live with diabetes while experiencing homelessness or housing instability and to propose and develop potential interventions for this population [ 25 ]. These eight participants met regularly in Toronto for study-related activities. In addition, we recruited several other participants to take part in this concept mapping exercise, to increase the sample size. To be eligible to participate, the clients had to: be older than 18 years, have a history of diabetes with a duration greater than two years, and have experienced homelessness within the previous two years. Homelessness in this study was defined similarly to the definition offered by the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness; we included participants whose living situations could be described as unsheltered, emergency sheltered, or provisionally sheltered [ 26 ]. Colleagues and advocates in the homeless-serving sector were consulted to determine the best places for recruiting the target population. Posters were put up in shelters, at homeless-serving agencies, and health clinics catering to the homeless population for recruitment. Established programs serving people who were experiencing homelessness or housing instability also helped with recruitment by advertising an information session to their program attendees. We explained the study to interested parties and obtained informed consent.

The service providers who took part in this study had previously been recruited as participants in another study of diabetes care for PWLEH [ 27 ]. They comprised professionals from four main categories of care: diabetes care professionals who worked primarily with inner-city or homeless populations, other health care professionals who worked primarily with inner-city or homeless populations, endocrinologists or diabetes care providers who did not specifically focus on inner-city or homeless populations, and other stakeholders, including frontline staff in shelters and social care providers. The providers were recruited from five major Canadian cities (Toronto, Ottawa, Edmonton, Calgary, and Vancouver), and they participated in this study remotely. Although the barriers to diabetes self-management may be similar across cities for PWLEH, the services available in each city differ [ 27 ]. Services in the health sector are largely impacted by funding and approval from provincial governments, which may have different priorities, and services in the homeless-serving sector are often provided by non-profit organizations, which rely to a great extent on donor funding for service provision. For these reasons, services that exist in one city may not exist in another, and we felt that it would be valuable to gain input from providers across different jurisdictions about their perspectives.

Data collection

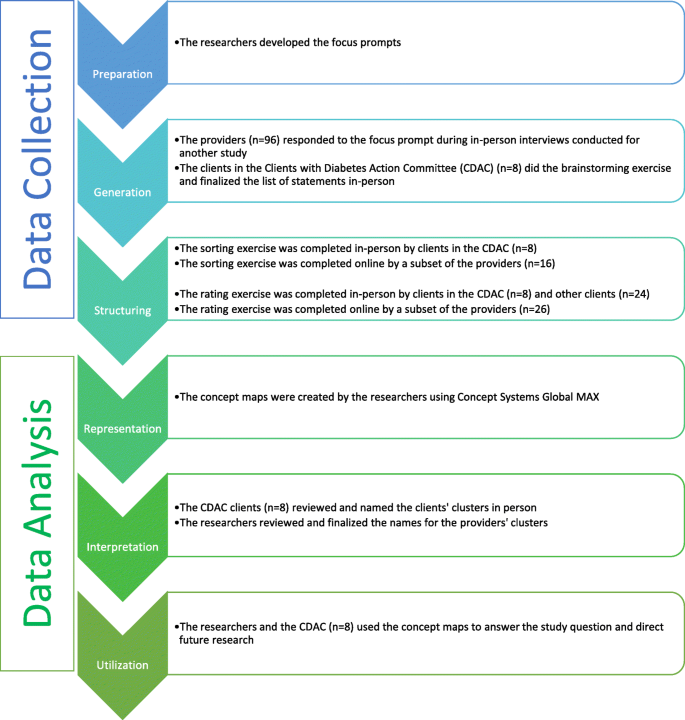

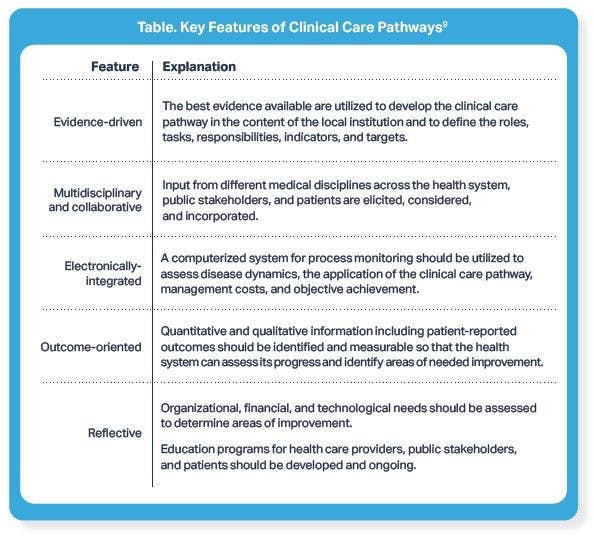

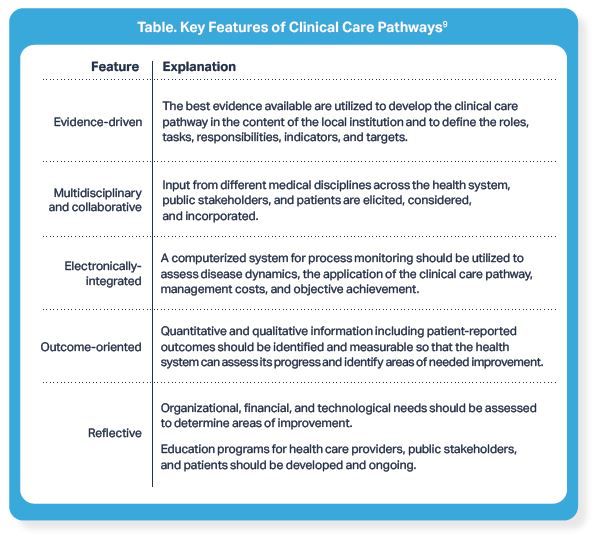

The concept mapping process involves six steps and is depicted in Fig. 1 . The initial three steps relate to data collection: preparation, generation of statements, and structuring of statements [ 28 ].

The concept mapping process

In the first step, preparation, the researchers must determine what the focus of the study will be. Usually, this involves two separate focus statements. The first statement is referred to as the focus prompt or the brainstorming focus, and it is developed to guide the brainstorming exercise in the second step. The second focus statement, called the rating focus, defines the factor(s) upon which the brainstormed statements will be rated in the rating exercise of the third step [ 28 , 29 ]. The focus prompt for the brainstorming exercise was, ‘What are some ways, good or bad, that diabetes might be affected by homelessness?’ . The rating prompt was: ‘What impact does [that factor] have on diabetes care and self-management (on a scale from no impact to high impact), specifically for people who are struggling with homelessness or housing instability?’ .

Generation involves a brainstorming exercise, in which the participants are provided with the focus prompt and asked to brainstorm statements in response [ 28 ]. The brainstorming exercise is done individually by each participant, and eventually, the ideas are combined and refined to form one set of statements [ 29 ]. Eight clients did the brainstorming exercise during an in-person group meeting. The providers had been individually interviewed by members of the research team, who then shared the providers’ ideas with the clients during their brainstorming session. The researchers recorded the ideas from the clients and the providers and refined the list of statements with the clients. The providers did not take part in the refinement of statements, as this aspect of the brainstorming exercise was done in person during a meeting with the clients.

Structuring involved two different exercises, sorting and rating. For the sorting exercise, each participant was asked to group individual statements into categories based on similarity, in a way that was meaningful to that individual [ 21 , 30 ]. The statements could not all be sorted into one pile, nor could each statement be in its own pile [ 29 ]. “Miscellaneous” piles with a group of statements that did not have a specific theme or link to each other were also discouraged. These instructions were explained to participants at the outset of the exercise and facilitators were present to help clarify instructions. The clients completed this exercise manually with statements printed on individual cue cards, while the providers completed this exercise using a tailor-made online platform. For the rating exercise, a Likert scale ranging from zero to four was used to rate each statement. A rating of zero meant the statement had no impact on diabetes control and self-management, and a rating of four meant it had an extreme impact on diabetes control and self-management. This exercise was done on paper forms by the clients and online by the providers.

Data analysis

The final three steps of the concept mapping process relate to data analysis: representation of statements, interpretation of maps, and utilization of maps [ 28 ].

In the representation step, sorting and rating data were analyzed using concept mapping software (Concept Systems Global Max, 2020, Ithaca NY) [ 30 , 31 ]. The representation step was done separately for the clients and the providers: the clients’ data were analyzed to create a clients’ cluster map and the providers’ data were analyzed to produce a providers’ cluster map. By having two cluster maps, rather than one, we were able to see how the number of clusters, the names of clusters, and the sorting of the statements, differed between the two participant groups.

The sorting data were analyzed using multidimensional scaling analysis, a technique that plots each statement as a point on a map. Statements that are closer together on the map were grouped together during the sorting exercise more often than statements that are farther apart. Multidimensional scaling was used to generate a matrix for each participant with one row and one column representing each of the statements [ 29 ]. In this study, the matrix had 43 rows and 43 columns. Each cell in the matrix corresponds to two statements, the row statement and the column statement. If those two statements were sorted into the same pile by the participant, the cell is given a value of one, and if they were not sorted into the same pile, the cell is assigned a value of zero [ 21 , 29 ]. This is done with each participant’s data so that there are as many separate matrices as there are participants in the study. All of the individual matrices are then summed to create a similarity matrix indicating how many participants sorted each pair of statements into the same pile [ 29 ]. This similarity data is used to create a two-dimensional point map, where the distance between two points on the map corresponds to their similarity [ 21 ].

These points were then grouped together to form clusters through hierarchical cluster analysis. Hierarchical cluster analysis uses the data from the point map to separate the points into non-overlapping clusters, developing a cluster map. The number of clusters in the final cluster map is determined by the participants and the researchers so that the map is presented in a way that is meaningful and useful to them [ 21 ]. This analysis begins by considering each statement to be in a cluster of its own, and it combines two clusters at a time, reducing the number of overall clusters until all the statements are in the same cluster. The statements are combined based on proximity, meaning that the two points that are closest together on the point map would be the first two points to form a cluster together [ 29 ]. The reliability, or goodness-of-fit of the map, is determined by calculating the final stress of the model [ 32 ]. Lower stress values suggest a better fit. Stress values in concept mapping data tend to be higher than in other multidimensional scaling analyses [ 33 ], therefore there is no accepted standard, however, it has been reported that an acceptable value for studies of this nature is less than 0.30 [ 34 ].

An average rating is then calculated for each cluster using the ratings for each of the individual statements in that cluster. Upon reviewing the average cluster ratings, it was clear that the clients and providers had rated the statements very differently, such that the clients had generally given lower ratings whereas the providers had given higher ratings, which resulted in lower average cluster ratings for the clients’ clusters and higher average cluster ratings for the providers’ clusters. To determine whether there was in fact a difference in the ratings between the two groups, the ratings were standardized and compared using unpaired two-sided t-tests, with an alpha of < 0.05. To standardize, the participants’ ratings for each statement were subtracted from the average rating of all the statements for their participant group (i.e., the clients’ average rating or the providers’ average rating). Both groups had different numbers of clusters with different numbers of statements in them, which would have been difficult to compare, so it was necessary to use the same cluster structure for both groups. We chose to compare based on the clients’ cluster structure because we wanted the analysis to be client-centred and because the clients had reviewed the clusters and the statements that were in each cluster, so the final structure reflected their feedback. We used unpaired t-tests to quantitatively compare the standardized cluster ratings to determine whether there was a statistically significant difference between the ratings of the clients and those of the providers for each cluster in the patient cluster map.

In the interpretation step, the maps and reports generated in the previous step are used to help frame the interpretation of the data. We assessed point maps, cluster maps, cluster reports with statements, and raw ratings reports. In this step, some of the clients were reconvened for an in-person meeting to discuss any changes that needed to be made to the maps and to provide input on the names of each of the clusters. The providers were not able to come together for a meeting, so their clusters were named by the researchers.

In the final step, utilization, the concept maps are reviewed to determine how they can be utilized to answer the study question [ 30 ]. In this study, the findings from the clients’ concept mapping research informed the subsequent research program in providing the topics of interest for the participatory photovoice project that ensued [ 35 ].

There were 32 clients and 96 providers who took part in this study: Although there were 128 participants altogether, only a subset of those participants took part in each stage of the concept mapping process (Fig. 1 ). For instance, only eight of the 32 clients took part in the brainstorming and sorting exercises, but all 32 took part in the rating exercise. For the providers, all 96 took part in the brainstorming exercise, but only 16 and 26 of these individuals took part in the sorting and rating exercises, respectively. The final sample size is consistent with what has typically been reported in other concept mapping projects [ 34 ].

Characteristics of the clients

The demographic characteristics of the clients are presented in Table 1 . All of the clients were over the age of 25 and just over half identified as men. None of the clients were sleeping rough at the time of this study, while a quarter of the clients were in private housing with the remainder in shelter or tenuous, transitional, or community housing. Collectively, they had experienced homelessness or housing instability for a median length of two years and had been living with diabetes for a median length of seven years. A majority of the clients had experienced some diabetes-related complications and had physical or mental health comorbidities as well. The most commonly reported method of managing diabetes was the use of oral medications, which were utilized by three-quarters of the clients, although approximately one-third of the clients used injectable agents (including insulin). The clients also saw a variety of care providers for the treatment of their diabetes; about three-quarters saw a family physician, one-fifth saw a pharmacist, and one-third saw a medical specialist, a diabetes nurse, and a diabetes dietitian, respectively.

Characteristics of the providers

Only eight of the providers completed the demographic survey. Most (6/8) were women, half were between the ages of 55 and 64, and 5/8 had 20 or more years of experience working with patients that have diabetes and/or complex social needs, while the rest had 15–19 years of experience. The providers also had a variety of different qualifications and titles including, registered dietitian, registered nurse, certified diabetes educator, family physician, program administrator/manager, and executive director. They also worked in a variety of settings such as community/private family medicine practices, specialty practices, community health centres, community pharmacies, academic/public family medicine practices, and homeless shelters.

Concept mapping

During the brainstorming exercise, the participants generated a list of statements representing barriers to self-management, starting with a large list, which was then refined by removing duplicates and combining similar statements. The resulting, final version of the list contained 43 statements (Table 2 ).

Using the data from the sorting exercises, the statements were plotted in relation to one another and presented as point maps through multidimensional scaling, and the points were then grouped to form cluster maps (Fig. 2 a and b) through hierarchical cluster analysis. The clients’ cluster map is based on sorting data from eight participants, and it consists of nine clusters, with a final stress value of 0.2987. Those clusters were named: (1) Challenges to getting healthy food , (2) Inadequate income , (3) Navigating services , (4) Not having a place of your own , (5) Relationships with professionals , (6) Diabetes education , (7) Emotional well-being , (8) Competing priorities , and (9) Weather-related issues . The providers’ cluster map had seven clusters, made using sorting data from 16 participants, and had a final stress value of 0.2521. The clusters were named: (1) Access to healthy food , (2) Dietary choices in the context of homelessness , (3) Limited finances , (4) Lack of stable, private housing , (5) Navigating the health and social sectors , (6) Emotional distress and competing priorities , and (7) Mental health and addictions . Appendix A (see Additional File 1 ) contains tables that list which statements were in each cluster for both the clients and the providers.

Cluster maps for the clients and the providers. a . Clients’ cluster map. b . Providers’ cluster map

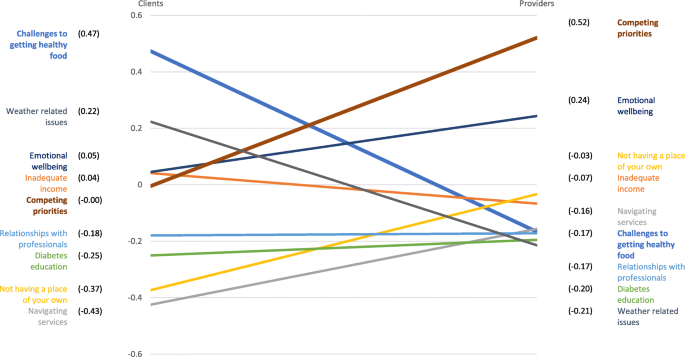

The rating exercise was completed by 32 clients and 26 providers. The ratings for the individual statements were used to calculate an average cluster rating. The clients’ clusters, arranged from the cluster with the highest average rating to the cluster with the lowest average rating, with the average rating in parentheses (out of a total of four), are: (1) Challenges to getting healthy food (2.08), (2) Weather-related issues (1.83), (3) Emotional well-being (1.65), (4) Inadequate income (1.65), (5) Competing priorities (1.60), (6) Relationships with professionals (1.43), (7) Diabetes education (1.35), (8) Not having a place of your own (1.23), and (9) Navigating services (1.18). Providers’ clusters, by contrast, were: (1) Mental health and addictions (3.54), (2) Emotional distress and competing priorities (3.42), (3) Dietary choices in the context of homelessness (3.12), (4) Navigating the health and social sectors (3.00), (5) Limited finances (2.97), (6) Lack of stable, private housing (2.88), and (7) Access to healthy food (2.79).

Using the grouping of clusters defined by clients, we calculated standardized cluster averages for the two groups (Fig. 3 ). There were two clusters for which the standardized averages differed in a statistically significant manner, Challenges to getting healthy food (standardized difference = 0.6396; p = 0.013) and Competing priorities (standardized difference=-0.5250; p = 0.026). The clients had a higher rating for Challenges to getting healthy food than the providers and the providers had a higher rating for Competing priorities . While trends were suggesting potential differences in the other clusters, these were the only two that reached statistical significance, due to the relatively small sample size for this quantitative analysis.

Graphical representation of the average standardized cluster ratings

The clients and providers identified a plethora of barriers to diabetes management, ultimately resulting in a refined list of 43 unique barriers. The clients’ and providers’ sorting data resulted in concept maps with distinct cluster names and configurations representing differing perceptions of barriers to managing diabetes while experiencing homelessness. Both the clients’ and the providers’ clusters represented themes related to access to healthy food; financial limitations; housing; health and social care; and psychosocial wellbeing. The clients chose to have a cluster titled Relationships with professionals , whereas the providers’ map included those barriers in the Navigating the health and social sectors and Lack of stable, private housing clusters. While the clients’ map has two clusters representing similar themes: Navigating services and Not having a place of your own , the clients saw the barriers related to relationships as being distinct from those related to navigation issues or housing issues and chose to have a separate cluster for them. These findings confirm the notion that the perspectives of clients/patients/service users and service providers regarding barriers to diabetes management may be different, and that the reasoning behind patients’ differing perspectives may not be evident to the providers. Traditionally, the identification of barriers and the creation of solutions has not meaningfully considered input from the individuals who have the most at stake, the patients/clients. Our findings highlight the importance of considering the patient perspective when designing solutions for enhancing diabetes management to address the barriers which have the greatest impact, according to patients.

Comparisons of the cluster ratings indicated that there were significant differences between the clients and the providers in the perceived impact of the barriers faced in diabetes management. The cluster related to challenges to accessing healthy food was the most influential from the client perspective, and it was rated significantly higher by the clients than the providers. The cluster representing priorities that compete with diabetes management was thought to be the most impactful by providers, and the rating for this cluster was significantly higher for the providers compared to the clients.

There are many reasons why accessing healthy food can be challenging for PWLEH. Many may rely on shelters or community kitchens for food so they must eat whatever is available, even if they have been advised to avoid such food by their healthcare providers [ 36 ]. The meals in shelters often have high amounts of sugar, starch and fat, and there are few fruits and vegetables available, which results in diets that are likely to be inappropriate for people with diabetes [ 7 ]. These shelters and community kitchens, however, also have limited resources and must often rely on food that is donated to them [ 24 ]. Sometimes, PWLEH may be unable to get three meals in a day so they are often eating when they can and hoarding extra food, so they have something to eat later. Alternatively, if they had access to affordable, nutritious food, they would not be worried about where their next meal is going to come from [ 37 ] and they would have greater diabetes self-management self-efficacy [ 38 ]. The lack of access to food is especially concerning for people who are using insulin, as they may use less than the prescribed amount of insulin for fear of developing hypoglycemia if they are not able to predict mealtimes reliably [ 15 ]. It is likely that because PWLEH need to negotiate their dietary intake daily, this rose to the top of the priority list for them. Providers may benefit from knowing that for PWLEH this is the most troubling aspect of diabetes self-management.

With regards to competing priorities, studies have noted that PWLEH tend to have many demands and prioritize things such as food, shelter, and employment above diabetes care and self-management practices [ 13 ]. When they continually face difficulties in meeting these basic needs, people may forego preventative care or sacrifice self-care [ 39 ]. This may partially explain why the providers believed that competing priorities have a great effect on diabetes management. As for why this cluster of factors was rated lower by clients, we hypothesize that this discrepancy may relate to lower health-related self-awareness in this population [ 40 ], or because clients did not fully grasp how their other issues may affect their diabetes, likely due to the fact that their social networks are often comprised of others who face similar issues. This is consistent with literature documenting that non-clinically trained people are typically less aware of the impact of the social determinants of health [ 41 ]. By contrast, healthcare providers are more likely to be informed about the social determinants of health and how diabetes care is affected significantly by the complete picture of patients’ lives [ 42 ]. It is also possible that barriers related to competing priorities were deemed less impactful by the clients because their greatest competing priority is accessing food, which had a separate cluster of its own, and had the highest average rating for the clients. The clients may also have felt that accessing healthy food is more important than other aspects of self-management if the diabetes education they received emphasized the importance of diet above all else.

The second highest-rated cluster for the clients was focused on issues related to the weather. Cold-related injuries are very common amongst PWLEH in Canada and they often result in emergency department visits [ 43 ]. One of the many complications of diabetes is reduced circulation, especially in the feet, so in cold weather foot care becomes even more important, as the winter weather can increase the risk for infections, frostbite and amputations [ 44 , 45 ].

The providers’ third highest-rated cluster focused on a lack of stable, secure housing and while the clients had a similar cluster, for them, it received the second-lowest rating. Understandably, providers would consider this an important barrier, given that there is much in the literature describing the need to treat homelessness as a health issue [ 46 ] and suggesting that it is important for providers to help address housing concerns [ 15 ]. It is surprising, however, that this cluster was given such a low rating relative to the other clusters by the clients because participants in other qualitative studies have described housing as a foundational need that affects diabetes self-management in numerous ways [ 36 , 47 ]. In one study, participants reported that being unstably housed is emotionally and physically draining, which makes it difficult to prioritize diabetes, and when the need for shelter is not met, there is no foundation from which they can pursue their health goals [ 47 ]. This view is in accordance with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which places basic needs such as food and shelter ahead of health [ 8 , 15 , 48 ]. Not having housing also means not having a secure place to store diabetes testing supplies such as glucometers or medications and insulin, and there is a fear that they may be stolen in a communal living arrangement such as an emergency shelter [ 36 ]. Furthermore, stable housing can provide a sense of consistency and control that can help with the routinization of diabetes care and allow some control over diet, while high housing costs can compete with the cost of diabetes care [ 47 ].

One of the strengths of this study is its participatory nature. We gathered input from PWLEH as well as a variety of providers who work in health and social settings, which ensured that we had diverse perspectives represented. The clients were able to review the concept maps and name the clusters, which meant that the final maps reflected their perspectives rather than the opinions of the researchers. This is important because the participants may see the value of having certain themes or representing the barriers a different way than the researchers. Concept mapping incorporates both qualitative and quantitative analyses in one process, which enables complex ideas to be explored in a short period of time, and the output of the quantitative analyses supplements and enhances the qualitative interpretations. Furthermore, the creation of visual representations through this combination of analyses provides structure and credibility to the results [ 30 ]. Additionally, it includes both individual and group activities, and the process in which these activities occur avoids some of the issues that are commonly experienced when using qualitative methodologies such as, the monopolization of group discussion time by one or two individuals, the likelihood of conformity bias, or the need for individuals to publicly discuss their personal opinions or experiences [ 30 ]. Another strength is that the participants were involved in the analysis of the data and they were able to interpret the concept maps that were created using their data. This methodology ensures that the thoughts of the participants are accurately reflected [ 28 , 30 ]. The visual concept maps allowed us to display the associations between multiple themes and the rating data enabled comparison of the relative importance of each theme [ 28 , 30 ].

There are also limitations to this study, one of which is that only eight clients completed the sorting exercise. This was due to the time commitment required of participants and the complexity of the task. Ideally, participants must take part in the brainstorming, sorting, and rating exercises, and then review the results and provide feedback, but it may be difficult to keep participants engaged throughout the whole process. However, despite this small sample, the resultant map still had an acceptable final stress value. Another limitation of this study is the lack of available demographic data about the providers, as only a small proportion of the providers completed the demographic survey. While it is unfortunate that we are unable to fully describe the group of providers who participated in this study, we do know that the roles they had and the settings they worked in varied considerably. Additionally, the providers did not have the opportunity to reflect on the concept map that was produced with their data. The research team decided to finalize the cluster map on their own because the providers were from five different cities, and it was not possible to plan a meeting for all of the providers.

The participants in our study identified many of the same barriers that are described in other studies. However, this study is unique in that it allowed participants to rank these barriers from most to least impactful on diabetes management – and compared these rankings between PWLEH and providers. The results show that clients and providers differ in their understanding of barriers and the impact they have on diabetes management. Given that the clients in this study have indicated that difficulties with accessing healthy food are the greatest barriers to managing diabetes, future research and interventions aimed at improving diabetes management among PWLEH who have diabetes could focus on determining how to improve access to diabetes-appropriate food for this population.

Availability of data and materials

The data pertaining to this study may be available upon request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

people with lived experience of homelessness

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020.

Public Health Agency of Canada. Diabetes in Canada: Facts and figures from a public health perspective. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2011.

Diabetes Canada. Diabetes 360: A framework for a diabetes strategy for Canada. 2018.

Sherifali D, Berard LD, Gucciardi E, MacDonald B, MacNeill G. Self-Management Education and Support. Can J Diabetes. 2018;42(Suppl 1):36-s41.

Google Scholar

Stone JA, Houlden RL, Lin P, Udell JA, Verma S. Cardiovascular Protection in People With Diabetes. Can J Diabetes. 2018;42(Suppl 1):162-s9.

Berard LD, Siemens R, Woo V. Monitoring Glycemic Control. Can J Diabetes. 2018;42(Suppl 1):47-s53.

Hwang SW, Bugeja AL. Barriers to appropriate diabetes management among homeless people in Toronto. CMAJ. 2000;163(2):161–5.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Davies A, Wood LJ. Homeless health care: meeting the challenges of providing primary care. Med J Aust. 2018;209(5):230–4.

Article Google Scholar

Gaetz S, Backgrounder: “What is homelessness?” 2009 [Available from: https://homelesshub.ca/resource/what-homelessness .

Campbell DJT, O’Neill BG, Gibson K, Thurston WE. Primary healthcare needs and barriers to care among Calgary’s homeless populations. BMC Fam Practice. 2015;16(1):139.

Canada. Standing Committee on Health. A diabetes strategy for Canada. 2019.

Campbell DJT, Manns BJ, Hemmelgarn BR, Sanmartin C, Edwards A, King-Shier K. Understanding Financial Barriers to Care in Patients With Diabetes: an Exploratory Qualitative Study. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43(1):78–86.

Elder NC, Tubb MR. Diabetes in homeless persons: barriers and enablers to health as perceived by patients, medical, and social service providers. Soc Work Public Health. 2014;29(3):220–31.

Mancini NL, Campbell RB, Yaphe HM, Tibebu T, Grewal EK, Saunders-Smith T, et al. Identifying challenges and solutions to providing diabetes care for the homeless. Diabetes Can. 2020.

Nickasch B, Marnocha SK. Healthcare experiences of the homeless. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2009;21(1):39–46.

Wen CK, Hudak PL, Hwang SW. Homeless people’s perceptions of welcomeness and unwelcomeness in healthcare encounters. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(7):1011–7.

Campbell RB, Saunders-Smith T, Tibebu T, Grewal EK, Yaphe HM, Mancini NL, et al. Patient-level barriers to diabetes management among those with housing instability. Can J Diabetes. 2020;44(7):S22.

Minh A, Patel S, Bruce-Barrett C, O’Campo P. Letting Youths Choose for Themselves: Concept Mapping as a Participatory Approach for Program and Service Planning. Fam Community Health. 2015;38(1):33–43.

Velonis AJ, Molnar A, Lee-Foon N, Rahim A, Boushel M, O’Campo P. “One program that could improve health in this neighbourhood is ____?“ using concept mapping to engage communities as part of a health and human services needs assessment. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):150-.

Acosta O, Toro PA. Let’s ask the homeless people themselves: a needs assessment based on a probability sample of adults. Am J Community Psychol. 2000;28(3):343–66.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Trochim W, Kane M. Concept mapping: an introduction to structured conceptualization in health care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17(3):187–91.

Gaetz S, Donaldson J, Richter T, Gulliver T. The State of Homelessness in Canada 2013. Toronto: Canadian Homelessness Research Network Press; 2013.

Lee TC, Hanlon JG, Ben-David J, Booth GL, Cantor WJ, Connelly PW, et al. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in homeless adults. Circulation. 2005;111(20):2629–35.

Davachi S, Ferrari I. Homelessness and Diabetes: Reducing Disparities in Diabetes Care Through Innovations and Partnerships. Can J Diabetes. 2012;36(2):75–82.

Campbell DJT, Campbell RB, DiGiandomenico A, Larsen M, Davidson MA, McBrien KA, Booth GL, Hwang SW. Using community-based participatory research approaches to meaningfully engage those with lived experience of diabetes and homelessness. BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care. 2021;9:e002154. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2021-002154 .

Gaetz S, Barr C, Friesen A, Harris B, Hill C, et al. Kovacs-Burns. Canadian Definition of Homelessness. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness; 2012.

Campbell DJT, Campbell RB, Booth GL, Hwang SW, McBrien KA. Innovations in Providing Diabetes Care for Individuals Experiencing Homelessness: An Environmental Scan. Can J Diabetes. 2020;44(7):643–50.

Trochim WM. An introduction to concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Eval Prog Plan. 1989;12(1):1–16.

Kane M, Trochim W. M. K. Concept Mapping for Planning and Evaluation. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 2007. Available from: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/concept-mapping-for-planning-and-evaluation .

Burke JG, O’Campo P, Peak GL, Gielen AC, McDonnell KA, Trochim WM. An introduction to concept mapping as a participatory public health research method. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(10):1392–410.

Concept Systems Inc. The Concept System® Global MAX™. Ithaca: Concept Systems Inc; 2020. p. Web-based Platform.

Kruskal JB. Multidimensional scaling by optimizing goodness of fit to a nonmetric hypothesis. Psychometrika. 1964;29(1):1–27.

Trochim WMK. The reliability of concept mapping. Annual Conference of the American Evaluation Association; Dallas. 1993.

Rosas SR, Kane M. Quality and rigor of the concept mapping methodology: a pooled study analysis. Eval Prog Plan. 2012;35(2):236–45.

Campbell R, Larsen M, DiGiandomenico A, Davidson M, Booth G, Hwang S, et al. Illustrating challenges of managing diabetes while homeless using photovoice methodology. Can Med Assoc J. 2021;193.

Rojas-Guyler L, Inniss-Richter ZM, Lee R, Bernard AL, King K, editors. Factors Predictive of Knowledge and Self-Management Behaviors among Male Military Veterans with Diabetes Residing in a Homeless Shelter for People Recovering from Addiction. 2014.

Lee BA, Greif MJ. Homelessness and hunger. J Health Soc Behav. 2008;49(1):3–19.

Vijayaraghavan M, Jacobs EA, Seligman H, Fernandez A. The association between housing instability, food insecurity, and diabetes self-efficacy in low-income adults. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(4):1279–91.

Gelberg L, Gallagher TC, Andersen RM, Koegel P. Competing priorities as a barrier to medical care among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(2):217–20.

Rew L. A Theory of Taking Care of Oneself Grounded in Experiences of Homeless Youth. Nurs Res. 2003;52(4):234–41.

Robert SA, Booske BC, Rigby E, Rohan AM. Public views on determinants of health, interventions to improve health, and priorities for government. WMJ. 2008;107(3):124–30.

PubMed Google Scholar

Willems S, Van Roy K, De Maeseneer J. Appendix A Educating health professionals to address the social determinants of health. A Framework for Educating Health Professionals to Address the Social Determinants. of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2016.

Zhang P, Bassil K, Gower S, Katj M, Kiss A, Gogosis E, et al. Cold-related injuries in a cohort of homeless adults. J Soc Distress Homeless. 2019;28:85–9.

Hillson R. Diabetes and temperature. Pract Diabetes. 2016;33(2):45–6.

Spero D. Diabetes Self-Management 2019. Available from: https://www.diabetesselfmanagement.com/blog/eight-ways-manage-diabetes-cold-weather/ .

Stafford A, Wood L. Tackling Health Disparities for People Who Are Homeless? Start with Social Determinants. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(12):1535.

Keene DE, Guo M, Murillo S. “That wasn’t really a place to worry about diabetes”: Housing access and diabetes self-management among low-income adults. Soc Sci Med. 2018;197:71–7.

Maslow AH. Motivation and Personality, 3rd Ed. New York: Harper and Row; 1987.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This study received funding from Alberta Innovates, the O’Brien Institute for Public Health and the Cal Wenzel Cardiometabolic Fund.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Medicine, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

Eshleen K. Grewal, Rachel B. Campbell & David J. T. Campbell

Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Gillian L. Booth, Stephen W. Hwang & Patricia O’Campo

Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Gillian L. Booth & Stephen W. Hwang

MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions, St. Michael’s Hospital, Unity Health Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Toronto, Canada

Department of Family Medicine, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

Kerry A. McBrien

Department of Community Health Sciences, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

Kerry A. McBrien & David J. T. Campbell

Department of Cardiac Sciences, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

David J. T. Campbell

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The study was conceived by DJTC and RBC with meaningful contributions from GLB, KAM, SWH, and PO. Data collection and analysis were conducted by EKG, RBC and DJTC. The initial draft of the manuscript was written by EKG and DJTC and was revised with feedback from RBC, GLB, KAM, SWH, and PO. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to David J. T. Campbell .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study received ethics approval from the institutional review boards at the University of Calgary (REB 18-1663) and St. Michael’s Hospital/Unity Health Toronto (REB 18–288). All participants provided informed consent.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

Statements organized by cluster. Tables displaying the clients’ clusters with statements and the providers’ clusters with statements.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Grewal, E.K., Campbell, R.B., Booth, G.L. et al. Using concept mapping to prioritize barriers to diabetes care and self-management for those who experience homelessness. Int J Equity Health 20 , 158 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01494-3

Download citation

Received : 22 February 2021

Accepted : 08 June 2021

Published : 09 July 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01494-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Diabetes mellitus

- Homeless persons

- Patient engagement research

- Patient priorities

- Community-based participatory research

International Journal for Equity in Health

ISSN: 1475-9276

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Entire Site

- Research & Funding

- Health Information

- About NIDDK

- For Health Professionals

- Diabetes Discoveries & Practice Blog

Every Person with Diabetes Needs Ongoing Self-Management Education and Support

- Patient Self-Management

- Medication and Monitoring

- Patient Communication

You prescribe medications for type 2 diabetes, but what about diabetes education and support? It can be just as essential.

Research shows that diabetes self-management education and support (DSMES) can improve A1C levels and have a positive effect on other clinical, psychosocial, and behavioral aspects of diabetes. Margaret (Maggie) Powers, PhD, RD, CDE, a clinician and research scientist at the International Diabetes Center in Park Nicollet in Minneapolis, explains how.

Q: Why should health care providers promote diabetes self-management education and support (DSMES) for their patients with type 2 diabetes?

A: It’s important because over 90 percent of diabetes care is self-care; provided by the person with diabetes. Diabetes self-management education and support enables people to be the best self-managers possible.

Q: When should that educational support be provided?

A: Our goal in writing the DSMES joint position statement was to provide clear guidance on the four critical times when a person with type 2 diabetes might need more attention to diabetes self-management. The objective was to encourage health care professionals to assess, provide, and adjust DSMES. This can help to avoid crisis management and support people with diabetes to be comfortable and confident in their decision making.

The position statement includes an algorithm of care that addresses four critical time points; these time points also are relevant for the other aspects of diabetes care.

- Fourth time point: When transitions in care occur, such as when someone is transitioning from the hospital to home or from home to assisted living. These transitions can affect an individual’s activity or ability to function, and we want to be on top of that, while also attending to other adjustments that might influence daily choices.

In clinical care at these different times, there is often a focus on, “Do we need to adjust the medication?” Yet, there’s also this whole aspect of actually taking the medication, the daily self-management, and nutrition. We want the health care system to be aware of these four critical time points and refer people appropriately to recognized and certified diabetes self-management education programs, registered dietitians, and mental health professionals, or to provide that care in the clinical setting.

Q: How can clinicians be encouraged to provide diabetes education, or make referrals for that education, at these time points for their patients?

A: We recommend embedding a diabetes self-management education and support checklist into clinical health records so that referrals for diabetes education are systematized. When you have someone who’s newly diagnosed with diabetes, or who’s experiencing another health problem, even if it’s a broken elbow—as their health care provider you may not be thinking, “I need to figure out how they’re going to stay active” or “How are they going to check their blood glucose?” or “Can they do that with one hand?” If the referral process is embedded in the clinical health record for the four critical time points, it can improve clinical outcomes, quality of care, and patient satisfaction.

Q: Can you provide more in-depth information on what is involved in DSMES?

A: If you’re the primary care provider, you can answer questions and provide emotional support regarding the diagnosis. But you might not have the time to ask and problem-solve important questions for the patient such as, “What times do you eat? When do you eat? How are you going to prepare foods now? When are you going to take the medication? How are you going to remember to take the medication?”

As diabetes educators, when we meet with someone at diagnosis, our role is to assess the factors that influence the individual’s decision making—like lifestyle, cultural influences, health beliefs, current knowledge, physical limitations, family support, financial status, medical history, even literacy and numeracy—we use a lot of numbers in diabetes. And we cover a lot of ground. We work with the person on medication adherence, monitoring of blood glucose, the food plan, physical activity, prevention of heart disease, and dealing with other acute and chronic complications. Diabetes education is also about risk reduction, such as smoking cessation, daily foot checks at home, and developing personal strategies to address psychosocial issues and concerns.

Q: What’s the evidence that diabetes education improves outcomes?

A: When I was president of the ADA, I did a talk on this topic, which is reprinted in the article, “If DSME Were a Pill, Would You Prescribe It?” Typically, when somebody is diagnosed with diabetes, they’re prescribed metformin. But why is diabetes education or nutrition therapy not automatically prescribed? The ADA goes through a process of evaluating medications and they look at efficacy—does it reduce A1C? What’s the risk of hypoglycemia with the medication? Is it weight neutral? What are the side effects? What are the costs? What I did in my talk was look at the efficacy of diabetes education using the same parameters. It reduces A1C; we have that data from diabetes education programs. We know that when people are initially diagnosed with diabetes, we can actually reduce or delay the initiation of medication with nutrition therapy.

Also, research shows that diabetes education improves the quality of life, self-efficacy, empowerment, healthy coping strategies, self-care behaviors, and adherence to the food plan. It also leads to healthier food choices, more activity, and use of glucose monitoring, and it lowers blood pressure and lipids. This is all referenced and cited in the article.

Q: Is diabetes education covered by Medicare and private insurance?

A: Medicare definitely believes in the value of education and reimburses for diabetes education and medical nutrition therapy. Private insurance also reimburses, especially for nutrition therapy. However, we've found that very few people are using the reimbursement benefits .

Q: What's preventing everyone with diabetes from receiving diabetes education?

A: I don’t think that there’s been a clear expectation by health care providers that they should write a referral or by people with diabetes that they should expect to receive referrals to a dietitian and a diabetes educator. But the ADA’s Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2019 recommend that everybody should receive nutrition therapy from a qualified person and they should receive diabetes education. People living with diabetes need to have clear expectations for this, and the health system—including primary care providers—needs to make the referrals. Clinical systems management can help by providing automatic referrals at the four critical time points.

There are still barriers that we're working through with Medicare. For example, you can't receive nutrition therapy and diabetes education at the same time. Another barrier is that Medicare requires diabetes education to be offered within the health system. We cannot offer our program at the local church, community center, or library—Medicare will not reimburse for those programs, even though we would like to make our programs more accessible in the community.

Another barrier is that the referral to diabetes education must come from the primary care provider. It can’t be the cardiologist, for example, and the patient cannot self-refer.

Q: The 2018 update of the ADA/EASD consensus report reinforces the importance of DSMES. What do you think will be the impact of this report?

A: I am thrilled that this consensus report supports the concept of four critical time points for diabetes education as well as individualized programs of medical nutrition therapy. The original version primarily focused on medication selection, but with each revision there’s been a much clearer indication of the value of diabetes education and medical nutrition therapy. I think this report can have a major impact on diabetes education by reducing the barriers to access and supporting the self-management needs of people with diabetes.

How do you ensure that your patients with diabetes receive education and support at critical times? Share below in the comments.

Editor’s Note: Learn more by viewing Discovering the Full Super Powers of DSMES (PDF, 1.96 MB) , a National Diabetes Education Program (NDEP) webinar and related continuing education credit available through CDC Training and Continuing Education Online .

Subscribe to get blog updates.

Share this page

We welcome comments; all comments must follow our comment policy .

Blog posts written by individuals from outside the government may be owned by the writer and graphics may be owned by their creator. In such cases, it is necessary to contact the writer, artist, or publisher to obtain permission for reuse.

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 4: Ambulatory Care—Type 2 Diabetes Management

Bradley Phillips; Michelle Farland

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Chapter aims, introduction.

- OUR PRACTICE—AN OUTPATIENT INTERDISCIPLINARY ENDOCRINOLOGY PRACTICE

- UTILIZING CRITICAL THINKING SKILLS IN OUR PRACTICE

- APPLICATION OF THE PPCP IN OUR PRACTICE

- THE COLLECTION OF PATIENT INFORMATION IN OUR PRACTICE

- CLINICAL REASONING, CRITICAL THINKING, AND THE PPCP FOR THE CARE OF CARLOS P.

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

The aims of this chapter are to:

Discuss the roles of a systematic patient care process and clinical reasoning in assessing and resolving medication-related problems as part of a collaborative effort to provide patient-centered care in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) management.

Incorporate the elements of the Pharmacists’ Patient Care Process (PPCP) in a simulated patient case while outlining critical thought processes and clinical reasoning as it relates to the care of a person with T2DM.

• Type 2 diabetes • critical thinking • clinical reasoning • medication optimization • chronic disease state management • Pharmacists’ Patient Care Process • patient-centered care

Providing care for patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) requires a multifactorial approach and is ideally conducted in an interdisciplinary practice. The World Health Organization describes diabetes as “a chronic disease that occurs either when the pancreas does not produce enough insulin or when the body cannot effectively use the insulin it produces.” 1 The primary concern of the resultant hyperglycemia is the negative impact on nerves and blood vessels. These negative impacts result in chronic complications of diabetes, including microvascular complications (eg, retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy) and macrovascular complications (eg, transient ischemic attack, cerebral vascular accident, myocardial infarction).

According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2023, the diagnosis of DM is made following a fasting plasma glucose (≥126 mg/dL), 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (≥200 mg/dL following 75 g anhydrous glucose), random plasma glucose (≥200 mg/dL with classic symptoms of hyperglycemia such as polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia), or A1C (≥6.5%). 2 Confirmation of the diagnostic test is needed in the absence of unequivocal hyperglycemia.

Over 37 million Americans have a diagnosis of diabetes, with about 90% having type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The cost of diabetes care in the United States has risen significantly in recent years, with a 26% increase between 2012 and 2017. In 2017, the estimated cost of diabetes was $327 billion (US dollars), with direct medical costs contributing $237 billion and reduced productivity contributing $90 billion. 3

Diabetes management requires active participation from the patient in many aspects of their lives, and accordingly, it requires healthcare providers to actively engage in the biopsychosocial model when applying a multifactorial approach to providing care to each patient. Therefore, the ADA recommends “people with diabetes can benefit from a coordinated multidisciplinary team that may include and is not limited to diabetes care and education specialists, primary care and subspecialty clinicians, nurses, registered dietitian nutritionists, exercise specialists, pharmacists, dentists, podiatrists, and mental health professionals.” 4

Sign in or create a free Access profile below to access even more exclusive content.

With an Access profile, you can save and manage favorites from your personal dashboard, complete case quizzes, review Q&A, and take these feature on the go with our Access app.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

- Previous Article

- Next Article

What Is Professional Competency?

Elements of a glycemic management education program, institutional culture, diabetes education in the hospital: establishing professional competency.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Cite Icon Cite

- Get Permissions

Carol S. Manchester; Diabetes Education in the Hospital: Establishing Professional Competency. Diabetes Spectr 1 October 2008; 21 (4): 268–271. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaspect.21.4.268

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Establishing and maintaining professional competency is essential for the successful delivery of diabetes care and education. An interdisciplinary approach to education is effective for facilitating the delivery of knowledge and supporting glycemic control efforts in the hospital. Educational programs should be designed to promote and develop critical thinking skills and clinical judgment using a variety of media and resources targeted to adult learners. A competent professional staff will provide care that is evidence-based, safe, effective, and appropriate for the population served. These efforts have the potential to improve quality outcome measures and enhance patient satisfaction.

Between 1980 and 2003, hospital discharges coded with a diagnosis of diabetes increased from 2.2 to 5.1 million, representing a 132% increase in 23 years. 1 The economic burden of diabetes care was estimated at $174 billion in 2007, of which $116 billion was spent on medical expenditures, including $58 million on hospital inpatient care. 2 These figures continue to increase at a time when the management of acute care diabetes and hyperglycemia has undergone intensification and rapid change. 3 – 5 Thus, health care systems are gaining an awareness of the importance of glycemic control, the impact that provision of diabetes care has on resources,and the need to redesign systems and processes that will optimize diabetes care delivery.

How, then, can national standards for diabetes care and education be met;staff knowledge be maintained at cost-neutral levels; lengths of stay,readmission rates, and hospital-acquired complications be reduced; and cost savings be achieved? 6 – 15 The establishment of an interdisciplinary team of clinical experts and“champions” can help achieve all of these goals and facilitate the delivery of diabetes self-management education in the acute care setting.

In a 2004 article, Abbate 16 stated that, “Improving diabetes care requires competent providers to be actively involved in quality improvement in order to build a system capable of translating their knowledge into optimal outcomes for patients.” To state that one is competent is to say that one has sufficient knowledge and ability and is capable of the task or position. A definition of competency that can be applied to all disciplines is, “a level of performance demonstrating the effective application of knowledge, skill, and judgment.” 17 In its scope of practice document, the International Council of Nurses states that, “The registered nurse attains knowledge and competency that reflects current nursing practice.” 18 And the American Nurses Association adds that, “Although registered nurses have the most contact with the acutely ill patient and are often the main providers of survival skills education, all health care providers need sufficient diabetes knowledge to provide safe, competent care to persons with or at risk for diabetes.” 19

Ensuring the professional competency of an entire clinical staff is essential to the successful delivery of evidence-based, safe, effective,respectful, and appropriate care.

Studies have reported the lack of diabetes knowledge prevalent in a variety of provider disciplines. 20 – 23 This lack of knowledge includes unawareness of current practice standards,insufficient understanding of pharmacological agents including insulin and oral diabetes agents, inaccurate carbohydrate counting, and an inability to critically assess patient characteristics crucial to individualized diabetes management. Add to this the need to carefully evaluate concomitant therapies,treat comorbidities, and provide diabetes self-management knowledge and skills to patients, and it becomes clear that providers are lacking crucial skills and knowledge essential to managing these complex tasks.

Key elements of a successful inpatient glycemic management education program include core competencies, knowledge assessment, development of a strategic education plan, and continuing education. These must be established by an interdisciplinary team composed of individuals knowledgeable about diabetes and willing to serve as champions of efforts to improve glycemic control. The complementary knowledge and skill sets of the various disciplines represented in a diabetes care team allow the team to develop an educational program that will disseminate the wide range of requisite knowledge and training necessary to ensure professional competency throughout the health care system.

Core competencies must be established for physicians, nurses, dietitians,and pharmacists as the primary providers of patients care and education. A competency is “verification that required skills, processes, or concepts are done/understood correctly as determined by an expert.” 24 Competencies are used to validate and verify the scientific knowledge base and skills of staff members. Core competencies related to hospital glycemic management and diabetes care include the proper use of insulin and other diabetes medications, nutrition therapy, point-of-care testing, hypoglycemia treatment, and concomitant therapies.

Methods that can be used to successfully evaluate competencies include case scenarios that require critical thinking and problem-solving skills with a focus on assessment, prioritization, and accurate clinical decision making, as well as simulation exercises that entail observation of skills (process audits) and can incorporate written exercises. Internet-based competency tests can also be created, allowing individuals to take a competency test at any time. Table 1 identifies key elements to be included in a core competencies test for insulin; Table 2 provides an example of an insulin competency checklist and questions designed to promote critical thinking and clinical judgment skills. It is important to consider the Joint Commission's requirements for age-related competencies and incorporate these into core competency tests developed for specific populations and staff members. 25

Core Competency Content for Insulin

Example of a Competency Question for Insulin

Before developing a strategic plan for diabetes staff education, a thorough assessment of each professional discipline's current knowledge and skills must be conducted. Valid tools are available or can be developed to test the basic knowledge necessary for safe care delivery and effective problem solving,prioritization, and assessment. It is extremely helpful to have an awareness of the educational preparation and training of the staff; recognizing the composition of the staff will help the team tailor educational offerings for specific groups or individuals using appropriate teaching methodologies. 26

A review and inventory of available tools, reference materials, and Internet-based resources must be completed. Determining the actual availability of these resources to staff is important. If the resources exist but staff members are unable to access them easily and in a timely manner, the benefit is lost. Additionally, an education budget must be discussed with administration so that it is clear how many non-patient–care hours can be used for learning.

Providing education to all staff members who deal with diabetic patients anywhere along the health care continuum presents significant challenges. Factors that can affect the success of educational initiatives include the varying work schedules of staff, paid versus unpaid time for training,inclusion of “nice to know” versus “need to know”information, and the linking of performance to clinical excellence and peer review. 27 Another major challenge is “information acquisition fatigue,” the constant introduction of new information, new equipment and technology, and new processes and changes that can lead to an inability to process, integrate, and internalize newly acquired knowledge. An educational plan should be multifaceted, realistic, and flexible and should have established measurable learning outcomes for staff.

Some components of a successful plan for acute care include employee orientation, tests of medication knowledge, preceptor clinical guidelines and curriculum, annual competency testing for each discipline (e.g., physicians,nurses, dietitians, and pharmacists), professional development and continuing education, and resource support. Facilities that are associated with an academic health center must also plan to review curriculum and provide orientation to faculty and students. Strong collaborative partnerships with schools can be established to provide graduate student preceptorships in diabetes care and education.

New employee orientation is an excellent opportunity to establish the standard of practice and impart necessary knowledge and understanding of glycemic management. This can include a review of the classifications of diabetes, the rationale for tight glycemic control, acute care glycemic targets, and the treatment modalities used in the hospital (e.g., basal-bolus insulin therapy). This is also a good time to stress the importance of educating patients to perform diabetes self-care sooner rather than later.

Incorporating relevant diabetes scenarios on a new employee test allows for assessment of their level of knowledge before they finish formal orientation. Preceptors of the new employees, who have had their knowledge validated before they model diabetes care for new staff, can then be aware of the new employees' strengths and identify appropriate learning opportunities.

Administration can be supportive by allowing time for new employees to be trained to competency rather than to a specific duration of time. 28 This is especially important when training new graduates. A study conducted by Forneris and Peden-McAlpine 29 with novice nurses identified the emergence of the intentional critical thinker at 4–6 months, with intentional coaching and narrative reflective journaling as part of the process. This confirms that critical-thinking skills are developed and nurtured by the professionals and experiences encountered over time.

Professional development or continuing education can be targeted at a basic or an advanced level. Special population needs and research can be incorporated into these offerings. Methods to facilitate learning include the development and use of case studies and case scenarios, Grand Rounds presentations, Internet-based learning modules, journal clubs, resource toolkits, and medication charts. Clinical rounding, clinical coaching,observation and shadowing, and cross-discipline training should be considered an integral part of the staff development plan. 27 , 30 – 34 A creative and innovative approach to education has resulted in sustained knowledge and professional growth. 35