- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

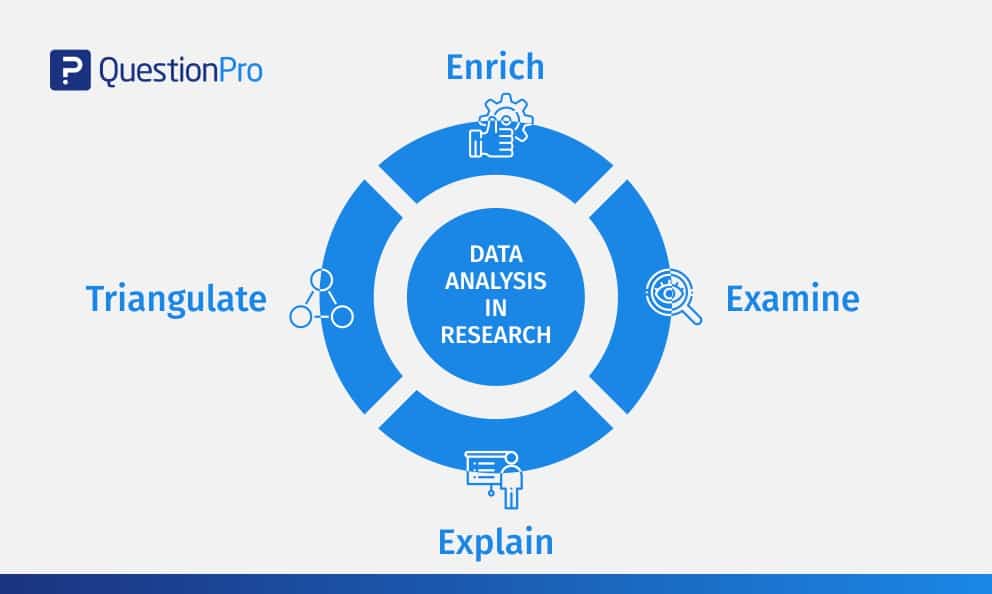

Data Analysis in Research: Types & Methods

Content Index

Why analyze data in research?

Types of data in research, finding patterns in the qualitative data, methods used for data analysis in qualitative research, preparing data for analysis, methods used for data analysis in quantitative research, considerations in research data analysis, what is data analysis in research.

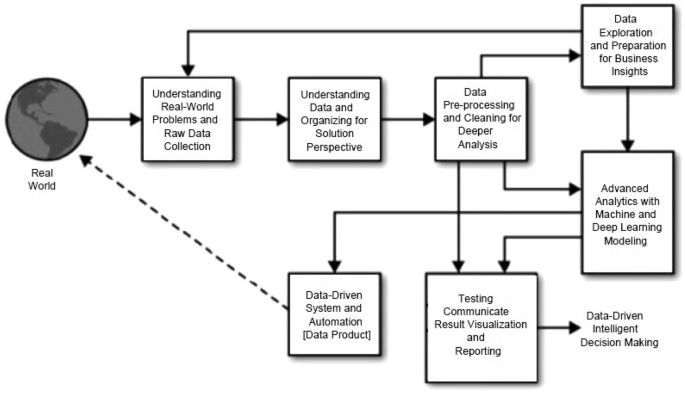

Definition of research in data analysis: According to LeCompte and Schensul, research data analysis is a process used by researchers to reduce data to a story and interpret it to derive insights. The data analysis process helps reduce a large chunk of data into smaller fragments, which makes sense.

Three essential things occur during the data analysis process — the first is data organization . Summarization and categorization together contribute to becoming the second known method used for data reduction. It helps find patterns and themes in the data for easy identification and linking. The third and last way is data analysis – researchers do it in both top-down and bottom-up fashion.

LEARN ABOUT: Research Process Steps

On the other hand, Marshall and Rossman describe data analysis as a messy, ambiguous, and time-consuming but creative and fascinating process through which a mass of collected data is brought to order, structure and meaning.

We can say that “the data analysis and data interpretation is a process representing the application of deductive and inductive logic to the research and data analysis.”

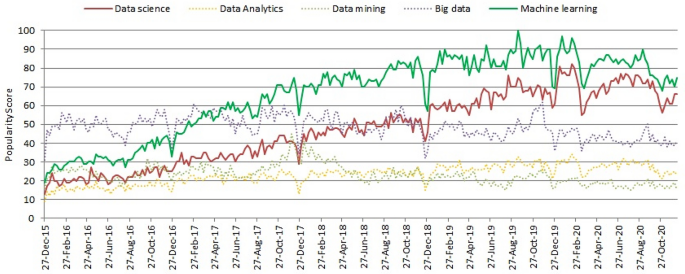

Researchers rely heavily on data as they have a story to tell or research problems to solve. It starts with a question, and data is nothing but an answer to that question. But, what if there is no question to ask? Well! It is possible to explore data even without a problem – we call it ‘Data Mining’, which often reveals some interesting patterns within the data that are worth exploring.

Irrelevant to the type of data researchers explore, their mission and audiences’ vision guide them to find the patterns to shape the story they want to tell. One of the essential things expected from researchers while analyzing data is to stay open and remain unbiased toward unexpected patterns, expressions, and results. Remember, sometimes, data analysis tells the most unforeseen yet exciting stories that were not expected when initiating data analysis. Therefore, rely on the data you have at hand and enjoy the journey of exploratory research.

Create a Free Account

Every kind of data has a rare quality of describing things after assigning a specific value to it. For analysis, you need to organize these values, processed and presented in a given context, to make it useful. Data can be in different forms; here are the primary data types.

- Qualitative data: When the data presented has words and descriptions, then we call it qualitative data . Although you can observe this data, it is subjective and harder to analyze data in research, especially for comparison. Example: Quality data represents everything describing taste, experience, texture, or an opinion that is considered quality data. This type of data is usually collected through focus groups, personal qualitative interviews , qualitative observation or using open-ended questions in surveys.

- Quantitative data: Any data expressed in numbers of numerical figures are called quantitative data . This type of data can be distinguished into categories, grouped, measured, calculated, or ranked. Example: questions such as age, rank, cost, length, weight, scores, etc. everything comes under this type of data. You can present such data in graphical format, charts, or apply statistical analysis methods to this data. The (Outcomes Measurement Systems) OMS questionnaires in surveys are a significant source of collecting numeric data.

- Categorical data: It is data presented in groups. However, an item included in the categorical data cannot belong to more than one group. Example: A person responding to a survey by telling his living style, marital status, smoking habit, or drinking habit comes under the categorical data. A chi-square test is a standard method used to analyze this data.

Learn More : Examples of Qualitative Data in Education

Data analysis in qualitative research

Data analysis and qualitative data research work a little differently from the numerical data as the quality data is made up of words, descriptions, images, objects, and sometimes symbols. Getting insight from such complicated information is a complicated process. Hence it is typically used for exploratory research and data analysis .

Although there are several ways to find patterns in the textual information, a word-based method is the most relied and widely used global technique for research and data analysis. Notably, the data analysis process in qualitative research is manual. Here the researchers usually read the available data and find repetitive or commonly used words.

For example, while studying data collected from African countries to understand the most pressing issues people face, researchers might find “food” and “hunger” are the most commonly used words and will highlight them for further analysis.

LEARN ABOUT: Level of Analysis

The keyword context is another widely used word-based technique. In this method, the researcher tries to understand the concept by analyzing the context in which the participants use a particular keyword.

For example , researchers conducting research and data analysis for studying the concept of ‘diabetes’ amongst respondents might analyze the context of when and how the respondent has used or referred to the word ‘diabetes.’

The scrutiny-based technique is also one of the highly recommended text analysis methods used to identify a quality data pattern. Compare and contrast is the widely used method under this technique to differentiate how a specific text is similar or different from each other.

For example: To find out the “importance of resident doctor in a company,” the collected data is divided into people who think it is necessary to hire a resident doctor and those who think it is unnecessary. Compare and contrast is the best method that can be used to analyze the polls having single-answer questions types .

Metaphors can be used to reduce the data pile and find patterns in it so that it becomes easier to connect data with theory.

Variable Partitioning is another technique used to split variables so that researchers can find more coherent descriptions and explanations from the enormous data.

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Research Questions and Questionnaires

There are several techniques to analyze the data in qualitative research, but here are some commonly used methods,

- Content Analysis: It is widely accepted and the most frequently employed technique for data analysis in research methodology. It can be used to analyze the documented information from text, images, and sometimes from the physical items. It depends on the research questions to predict when and where to use this method.

- Narrative Analysis: This method is used to analyze content gathered from various sources such as personal interviews, field observation, and surveys . The majority of times, stories, or opinions shared by people are focused on finding answers to the research questions.

- Discourse Analysis: Similar to narrative analysis, discourse analysis is used to analyze the interactions with people. Nevertheless, this particular method considers the social context under which or within which the communication between the researcher and respondent takes place. In addition to that, discourse analysis also focuses on the lifestyle and day-to-day environment while deriving any conclusion.

- Grounded Theory: When you want to explain why a particular phenomenon happened, then using grounded theory for analyzing quality data is the best resort. Grounded theory is applied to study data about the host of similar cases occurring in different settings. When researchers are using this method, they might alter explanations or produce new ones until they arrive at some conclusion.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

Data analysis in quantitative research

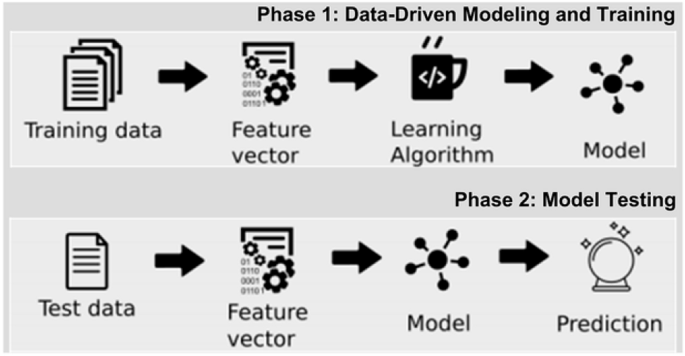

The first stage in research and data analysis is to make it for the analysis so that the nominal data can be converted into something meaningful. Data preparation consists of the below phases.

Phase I: Data Validation

Data validation is done to understand if the collected data sample is per the pre-set standards, or it is a biased data sample again divided into four different stages

- Fraud: To ensure an actual human being records each response to the survey or the questionnaire

- Screening: To make sure each participant or respondent is selected or chosen in compliance with the research criteria

- Procedure: To ensure ethical standards were maintained while collecting the data sample

- Completeness: To ensure that the respondent has answered all the questions in an online survey. Else, the interviewer had asked all the questions devised in the questionnaire.

Phase II: Data Editing

More often, an extensive research data sample comes loaded with errors. Respondents sometimes fill in some fields incorrectly or sometimes skip them accidentally. Data editing is a process wherein the researchers have to confirm that the provided data is free of such errors. They need to conduct necessary checks and outlier checks to edit the raw edit and make it ready for analysis.

Phase III: Data Coding

Out of all three, this is the most critical phase of data preparation associated with grouping and assigning values to the survey responses . If a survey is completed with a 1000 sample size, the researcher will create an age bracket to distinguish the respondents based on their age. Thus, it becomes easier to analyze small data buckets rather than deal with the massive data pile.

LEARN ABOUT: Steps in Qualitative Research

After the data is prepared for analysis, researchers are open to using different research and data analysis methods to derive meaningful insights. For sure, statistical analysis plans are the most favored to analyze numerical data. In statistical analysis, distinguishing between categorical data and numerical data is essential, as categorical data involves distinct categories or labels, while numerical data consists of measurable quantities. The method is again classified into two groups. First, ‘Descriptive Statistics’ used to describe data. Second, ‘Inferential statistics’ that helps in comparing the data .

Descriptive statistics

This method is used to describe the basic features of versatile types of data in research. It presents the data in such a meaningful way that pattern in the data starts making sense. Nevertheless, the descriptive analysis does not go beyond making conclusions. The conclusions are again based on the hypothesis researchers have formulated so far. Here are a few major types of descriptive analysis methods.

Measures of Frequency

- Count, Percent, Frequency

- It is used to denote home often a particular event occurs.

- Researchers use it when they want to showcase how often a response is given.

Measures of Central Tendency

- Mean, Median, Mode

- The method is widely used to demonstrate distribution by various points.

- Researchers use this method when they want to showcase the most commonly or averagely indicated response.

Measures of Dispersion or Variation

- Range, Variance, Standard deviation

- Here the field equals high/low points.

- Variance standard deviation = difference between the observed score and mean

- It is used to identify the spread of scores by stating intervals.

- Researchers use this method to showcase data spread out. It helps them identify the depth until which the data is spread out that it directly affects the mean.

Measures of Position

- Percentile ranks, Quartile ranks

- It relies on standardized scores helping researchers to identify the relationship between different scores.

- It is often used when researchers want to compare scores with the average count.

For quantitative research use of descriptive analysis often give absolute numbers, but the in-depth analysis is never sufficient to demonstrate the rationale behind those numbers. Nevertheless, it is necessary to think of the best method for research and data analysis suiting your survey questionnaire and what story researchers want to tell. For example, the mean is the best way to demonstrate the students’ average scores in schools. It is better to rely on the descriptive statistics when the researchers intend to keep the research or outcome limited to the provided sample without generalizing it. For example, when you want to compare average voting done in two different cities, differential statistics are enough.

Descriptive analysis is also called a ‘univariate analysis’ since it is commonly used to analyze a single variable.

Inferential statistics

Inferential statistics are used to make predictions about a larger population after research and data analysis of the representing population’s collected sample. For example, you can ask some odd 100 audiences at a movie theater if they like the movie they are watching. Researchers then use inferential statistics on the collected sample to reason that about 80-90% of people like the movie.

Here are two significant areas of inferential statistics.

- Estimating parameters: It takes statistics from the sample research data and demonstrates something about the population parameter.

- Hypothesis test: I t’s about sampling research data to answer the survey research questions. For example, researchers might be interested to understand if the new shade of lipstick recently launched is good or not, or if the multivitamin capsules help children to perform better at games.

These are sophisticated analysis methods used to showcase the relationship between different variables instead of describing a single variable. It is often used when researchers want something beyond absolute numbers to understand the relationship between variables.

Here are some of the commonly used methods for data analysis in research.

- Correlation: When researchers are not conducting experimental research or quasi-experimental research wherein the researchers are interested to understand the relationship between two or more variables, they opt for correlational research methods.

- Cross-tabulation: Also called contingency tables, cross-tabulation is used to analyze the relationship between multiple variables. Suppose provided data has age and gender categories presented in rows and columns. A two-dimensional cross-tabulation helps for seamless data analysis and research by showing the number of males and females in each age category.

- Regression analysis: For understanding the strong relationship between two variables, researchers do not look beyond the primary and commonly used regression analysis method, which is also a type of predictive analysis used. In this method, you have an essential factor called the dependent variable. You also have multiple independent variables in regression analysis. You undertake efforts to find out the impact of independent variables on the dependent variable. The values of both independent and dependent variables are assumed as being ascertained in an error-free random manner.

- Frequency tables: The statistical procedure is used for testing the degree to which two or more vary or differ in an experiment. A considerable degree of variation means research findings were significant. In many contexts, ANOVA testing and variance analysis are similar.

- Analysis of variance: The statistical procedure is used for testing the degree to which two or more vary or differ in an experiment. A considerable degree of variation means research findings were significant. In many contexts, ANOVA testing and variance analysis are similar.

- Researchers must have the necessary research skills to analyze and manipulation the data , Getting trained to demonstrate a high standard of research practice. Ideally, researchers must possess more than a basic understanding of the rationale of selecting one statistical method over the other to obtain better data insights.

- Usually, research and data analytics projects differ by scientific discipline; therefore, getting statistical advice at the beginning of analysis helps design a survey questionnaire, select data collection methods , and choose samples.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

- The primary aim of data research and analysis is to derive ultimate insights that are unbiased. Any mistake in or keeping a biased mind to collect data, selecting an analysis method, or choosing audience sample il to draw a biased inference.

- Irrelevant to the sophistication used in research data and analysis is enough to rectify the poorly defined objective outcome measurements. It does not matter if the design is at fault or intentions are not clear, but lack of clarity might mislead readers, so avoid the practice.

- The motive behind data analysis in research is to present accurate and reliable data. As far as possible, avoid statistical errors, and find a way to deal with everyday challenges like outliers, missing data, data altering, data mining , or developing graphical representation.

LEARN MORE: Descriptive Research vs Correlational Research The sheer amount of data generated daily is frightening. Especially when data analysis has taken center stage. in 2018. In last year, the total data supply amounted to 2.8 trillion gigabytes. Hence, it is clear that the enterprises willing to survive in the hypercompetitive world must possess an excellent capability to analyze complex research data, derive actionable insights, and adapt to the new market needs.

LEARN ABOUT: Average Order Value

QuestionPro is an online survey platform that empowers organizations in data analysis and research and provides them a medium to collect data by creating appealing surveys.

MORE LIKE THIS

Customer Communication Tool: Types, Methods, Uses, & Tools

Apr 23, 2024

Top 12 Sentiment Analysis Tools for Understanding Emotions

QuestionPro BI: From research data to actionable dashboards within minutes

Apr 22, 2024

21 Best Customer Experience Management Software in 2024

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

data analysis Recently Published Documents

Total documents.

- Latest Documents

- Most Cited Documents

- Contributed Authors

- Related Sources

- Related Keywords

Introduce a Survival Model with Spatial Skew Gaussian Random Effects and its Application in Covid-19 Data Analysis

Futuristic prediction of missing value imputation methods using extended ann.

Missing data is universal complexity for most part of the research fields which introduces the part of uncertainty into data analysis. We can take place due to many types of motives such as samples mishandling, unable to collect an observation, measurement errors, aberrant value deleted, or merely be short of study. The nourishment area is not an exemption to the difficulty of data missing. Most frequently, this difficulty is determined by manipulative means or medians from the existing datasets which need improvements. The paper proposed hybrid schemes of MICE and ANN known as extended ANN to search and analyze the missing values and perform imputations in the given dataset. The proposed mechanism is efficiently able to analyze the blank entries and fill them with proper examining their neighboring records in order to improve the accuracy of the dataset. In order to validate the proposed scheme, the extended ANN is further compared against various recent algorithms or mechanisms to analyze the efficiency as well as the accuracy of the results.

Applications of multivariate data analysis in shelf life studies of edible vegetal oils – A review of the few past years

Hypothesis formalization: empirical findings, software limitations, and design implications.

Data analysis requires translating higher level questions and hypotheses into computable statistical models. We present a mixed-methods study aimed at identifying the steps, considerations, and challenges involved in operationalizing hypotheses into statistical models, a process we refer to as hypothesis formalization . In a formative content analysis of 50 research papers, we find that researchers highlight decomposing a hypothesis into sub-hypotheses, selecting proxy variables, and formulating statistical models based on data collection design as key steps. In a lab study, we find that analysts fixated on implementation and shaped their analyses to fit familiar approaches, even if sub-optimal. In an analysis of software tools, we find that tools provide inconsistent, low-level abstractions that may limit the statistical models analysts use to formalize hypotheses. Based on these observations, we characterize hypothesis formalization as a dual-search process balancing conceptual and statistical considerations constrained by data and computation and discuss implications for future tools.

The Complexity and Expressive Power of Limit Datalog

Motivated by applications in declarative data analysis, in this article, we study Datalog Z —an extension of Datalog with stratified negation and arithmetic functions over integers. This language is known to be undecidable, so we present the fragment of limit Datalog Z programs, which is powerful enough to naturally capture many important data analysis tasks. In limit Datalog Z , all intensional predicates with a numeric argument are limit predicates that keep maximal or minimal bounds on numeric values. We show that reasoning in limit Datalog Z is decidable if a linearity condition restricting the use of multiplication is satisfied. In particular, limit-linear Datalog Z is complete for Δ 2 EXP and captures Δ 2 P over ordered datasets in the sense of descriptive complexity. We also provide a comprehensive study of several fragments of limit-linear Datalog Z . We show that semi-positive limit-linear programs (i.e., programs where negation is allowed only in front of extensional atoms) capture coNP over ordered datasets; furthermore, reasoning becomes coNEXP-complete in combined and coNP-complete in data complexity, where the lower bounds hold already for negation-free programs. In order to satisfy the requirements of data-intensive applications, we also propose an additional stability requirement, which causes the complexity of reasoning to drop to EXP in combined and to P in data complexity, thus obtaining the same bounds as for usual Datalog. Finally, we compare our formalisms with the languages underpinning existing Datalog-based approaches for data analysis and show that core fragments of these languages can be encoded as limit programs; this allows us to transfer decidability and complexity upper bounds from limit programs to other formalisms. Therefore, our article provides a unified logical framework for declarative data analysis which can be used as a basis for understanding the impact on expressive power and computational complexity of the key constructs available in existing languages.

An empirical study on Cross-Border E-commerce Talent Cultivation-—Based on Skill Gap Theory and big data analysis

To solve the dilemma between the increasing demand for cross-border e-commerce talents and incompatible students’ skill level, Industry-University-Research cooperation, as an essential pillar for inter-disciplinary talent cultivation model adopted by colleges and universities, brings out the synergy from relevant parties and builds the bridge between the knowledge and practice. Nevertheless, industry-university-research cooperation developed lately in the cross-border e-commerce field with several problems such as unstable collaboration relationships and vague training plans.

The Effects of Cross-border e-Commerce Platforms on Transnational Digital Entrepreneurship

This research examines the important concept of transnational digital entrepreneurship (TDE). The paper integrates the host and home country entrepreneurial ecosystems with the digital ecosystem to the framework of the transnational digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. The authors argue that cross-border e-commerce platforms provide critical foundations in the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. Entrepreneurs who count on this ecosystem are defined as transnational digital entrepreneurs. Interview data were dissected for the purpose of case studies to make understanding from twelve Chinese immigrant entrepreneurs living in Australia and New Zealand. The results of the data analysis reveal that cross-border entrepreneurs are in actual fact relying on the significant framework of the transnational digital ecosystem. Cross-border e-commerce platforms not only play a bridging role between home and host country ecosystems but provide entrepreneurial capitals as digital ecosystem promised.

Subsampling and Jackknifing: A Practically Convenient Solution for Large Data Analysis With Limited Computational Resources

The effects of cross-border e-commerce platforms on transnational digital entrepreneurship, a trajectory evaluator by sub-tracks for detecting vot-based anomalous trajectory.

With the popularization of visual object tracking (VOT), more and more trajectory data are obtained and have begun to gain widespread attention in the fields of mobile robots, intelligent video surveillance, and the like. How to clean the anomalous trajectories hidden in the massive data has become one of the research hotspots. Anomalous trajectories should be detected and cleaned before the trajectory data can be effectively used. In this article, a Trajectory Evaluator by Sub-tracks (TES) for detecting VOT-based anomalous trajectory is proposed. Feature of Anomalousness is defined and described as the Eigenvector of classifier to filter Track Lets anomalous trajectory and IDentity Switch anomalous trajectory, which includes Feature of Anomalous Pose and Feature of Anomalous Sub-tracks (FAS). In the comparative experiments, TES achieves better results on different scenes than state-of-the-art methods. Moreover, FAS makes better performance than point flow, least square method fitting and Chebyshev Polynomial Fitting. It is verified that TES is more accurate and effective and is conducive to the sub-tracks trajectory data analysis.

Export Citation Format

Share document.

Loading metrics

Open Access

Principles for data analysis workflows

Contributed equally to this work with: Sara Stoudt, Váleri N. Vásquez

Affiliations Berkeley Institute for Data Science, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, California, United States of America, Statistical & Data Sciences Program, Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts, United States of America

Affiliations Berkeley Institute for Data Science, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, California, United States of America, Energy and Resources Group, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, California, United States of America

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Berkeley Institute for Data Science, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, California, United States of America, Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, California, United States of America

- Sara Stoudt,

- Váleri N. Vásquez,

- Ciera C. Martinez

Published: March 18, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008770

- Reader Comments

A systematic and reproducible “workflow”—the process that moves a scientific investigation from raw data to coherent research question to insightful contribution—should be a fundamental part of academic data-intensive research practice. In this paper, we elaborate basic principles of a reproducible data analysis workflow by defining 3 phases: the Explore, Refine, and Produce Phases. Each phase is roughly centered around the audience to whom research decisions, methodologies, and results are being immediately communicated. Importantly, each phase can also give rise to a number of research products beyond traditional academic publications. Where relevant, we draw analogies between design principles and established practice in software development. The guidance provided here is not intended to be a strict rulebook; rather, the suggestions for practices and tools to advance reproducible, sound data-intensive analysis may furnish support for both students new to research and current researchers who are new to data-intensive work.

Citation: Stoudt S, Vásquez VN, Martinez CC (2021) Principles for data analysis workflows. PLoS Comput Biol 17(3): e1008770. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008770

Editor: Patricia M. Palagi, SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, SWITZERLAND

Copyright: © 2021 Stoudt et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: SS was supported by the National Physical Sciences Consortium ( https://stemfellowships.org/ ) fellowship. SS, VNV, and CCM were supported by the Gordon & Betty Moore Foundation ( https://www.moore.org/ ) (GBMF3834) and Alfred P. Sloan Foundation ( https://sloan.org/ ) (2013-10-27) as part of the Moore-Sloan Data Science Environments. CCM holds a Postdoctoral Enrichment Program Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund ( https://www.bwfund.org/ ). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Both traditional science fields and the humanities are becoming increasingly data driven and computational. Researchers who may not identify as data scientists are working with large and complex data on a regular basis. A systematic and reproducible research workflow —the process that moves a scientific investigation from raw data to coherent research question to insightful contribution—should be a fundamental part of data-intensive research practice in any academic discipline. The importance and effective development of a workflow should, in turn, be a cornerstone of the data science education designed to prepare researchers across disciplinary specializations.

Data science education tends to review foundational statistical analysis methods [ 1 ] and furnish training in computational tools , software, and programming languages. In scientific fields, education and training includes a review of domain-specific methods and tools, but generally omits guidance on the coding practices relevant to developing new analysis software—a skill of growing relevance in data-intensive scientific fields [ 2 ]. Meanwhile, the holistic discussion of how to develop and pursue a research workflow is often left out of introductions to both data science and disciplinary science. Too frequently, students and academic practitioners of data-intensive research are left to learn these essential skills on their own and on the job. Guidance on the breadth of potential products that can emerge from research is also lacking. In the interest of both reproducible science (providing the necessary data and code to recreate the results) and effective career building, researchers should be primed to regularly generate outputs over the course of their workflow.

The goal of this paper is to deconstruct an academic data-intensive research project, demonstrating how both design principles and software development methods can motivate the creation and standardization of practices for reproducible data and code. The implementation of such practices generates research products that can be effectively communicated, in addition to constituting a scientific contribution. Here, “data-intensive” research is used interchangeably with “data science” in a recognition of the breadth of domain applications that draw upon computational analysis methods and workflows. (We define other terms we’ve bolded throughout this paper in Box 1 ). To be useful, let alone high impact, research analyses should be contextualized in the data processing decisions that led to their creation and accompanied by a narrative that explains why the rest of the world should be interested. One way of thinking about this is that the scientific method should be tangibly reflected, and feasibly reproducible, in any data-intensive research project.

Box 1. Terminology

This box provides definitions for terms in bold throughout the text. Terms are sorted alphabetically and cross referenced where applicable.

Agile: An iterative software development framework which adheres to the principles described in the Manifesto for Agile software development [ 35 ] (e.g., breaks up work into small increments).

Accessor function: A function that returns the value of a variable (synonymous term: getter function).

Assertion: An expression that is expected to be true at a particular point in the code.

Computational tool: May include libraries, packages, collections of functions, and/or data structures that have been consciously designed to facilitate the development and pursuit of data-intensive questions (synonymous term: software tool).

Continuous integration: Automatic tests that updated code.

Gut check: Also “data gut check.” Quick, broad, and shallow testing [ 48 ] before and during data analysis. Although this is usually described in the context of software development, the concept of a data-specific gut check can include checking the dimensions of data structures after merging or assessing null values/missing values, zero values, negative values, and ranges of values to see if they make sense (synonymous words: smoke test, sanity check [ 49 ], consistency check, sniff test, soundness check).

Data-intensive research : Research that is centrally based on the analysis of data and its structural or statistical properties. May include but is not limited to research that hinges on large volumes of data or a wide variety of data types requiring computational skills to approach such research (synonymous term: data science research). “Data science” as a stand-alone term may also refer more broadly to the use of computational tools and statistical methods to gain insights from digitized information.

Data structure: A format for storing data values and definition of operations that can be applied to data of a particular type.

Defensive programming : Strategies to guard against failures or bugs in code; this includes the use of tests and assertions.

Design thinking: The iterative process of defining a problem then identifying and prototyping potential solutions to that problem, with an emphasis on solutions that are empathetic to the particular needs of the target user.

Docstring: A code comment for a particular line of code that describes what a function does, as opposed to how the function performs that operation.

DOI: A digital object identifier or DOI is a unique handle, standardized by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), that can be assigned to different types of information objects.

Extensibility: The flexibility to be extended or repurposed in a new scenario.

Function: A piece of more abstracted code that can be reused to perform the same operation on different inputs of the same type and has a standardized output [ 50 – 52 ].

Getter function: Another term for an accessor function.

Integrated Development Environment (IDE): A software application that facilitates software development and minimally consists of a source code editor, build automation tools, and a debugger.

Modularity: An ability to separate different functionality into stand-alone pieces.

Mutator method: A function used to control changes to variables. See “setter function” and “accessor function.”

Notebook: A computational or physical place to store details of a research process including decisions made.

Mechanistic code : Code used to perform a task as opposed to conduct an analysis. Examples include processing functions and plotting functions.

Overwrite: The process, intentional or accidental, of assigning new values to existing variables.

Package manager: A system used to automate the installation and configuration of software.

Pipeline : A series of programmatic processes during data analysis and data cleaning, usually linear in nature, that can be automated and usually be described in the context of inputs and outputs.

Premature optimization : Focusing on details before the general scheme is decided upon.

Refactoring: A change in code, such as file renaming, to make it more organized without changing the overall output or behavior.

Replicable: A new study arrives at the same scientific findings as a previous study, collecting new data (with the same or different methods) and completes new analyses [ 53 – 55 ].

Reproducible: Authors provide all the necessary data, and the computer codes to run the analysis again, recreating the results [ 53 – 55 ].

Script : A collection of code, ideally related to one particular step in the data analysis.

Setter function: A type of function that controls changes to variables. It is used to directly access and alter specific values (synonymous term: mutator method).

Serialization: The process of saving data structures, inputs and outputs, and experimental setups generally in a storable, shareable format. Serialized information can be reconstructed in different computer environments for the purpose of replicating or reproducing experiments.

Software development: A process of writing and documenting code in pursuit of an end goal, typically focused on process over analysis.

Source code editor: A program that facilitates changes to code by an author.

Technical debt: The extra work you defer by pursuing an easier, yet not ideal solution, early on in the coding process.

Test-driven development: Each change in code should be verified against tests to prove its functionality.

Unit test: A code test for the smallest chunk of code that is actually testable.

Version control: A way of managing changes to code or documentation that maintains a record of changes over time.

White paper: An informative, at least semiformal document that explains a particular issue but is not peer reviewed.

Workflow : The process that moves a scientific investigation from raw data to coherent research question to insightful contribution. This often involves a complex series of processes and includes a mixture of machine automation and human intervention. It is a nonlinear and iterative exercise.

Discussions of “workflow” in data science can take on many different meanings depending on the context. For example, the term “workflow” often gets conflated with the term “ pipeline ” in the context of software development and engineering. Pipelines are often described as a series of processes that can be programmatically defined and automated and explained in the context of inputs and outputs. However, in this paper, we offer an important distinction between pipelines and workflows: The former refers to what a computer does, for example, when a piece of software automatically runs a series of Bash or R script s. For the purpose of this paper, a workflow describes what a researcher does to make advances on scientific questions: developing hypotheses, wrangling data, writing code, and interpreting results.

Data analysis workflows can culminate in a number of outcomes that are not restricted to the traditional products of software engineering (software tools and packages) or academia (research papers). Rather, the workflow that a researcher defines and iterates over the course of a data science project can lead to intellectual contributions as varied as novel data sets, new methodological approaches, or teaching materials in addition to the classical tools, packages, and papers. While the workflow should be designed to serve the researcher and their collaborators, maintaining a structured approach throughout the process will inform results that are replicable (see replicable versus reproducible in Box 1 ) and easily translated into a variety of products that furnish scientific insights for broader consumption.

In the following sections, we explain the basic principles of a constructive and productive data analysis workflow by defining 3 phases: the Explore, Refine, and Produce Phases. Each phase is roughly centered around the audience to whom research decisions, methodologies, and results are being immediately communicated. Where relevant, we draw analogies to the realm of design thinking and software development . While the 3 phases described here are not intended to be a strict rulebook, we hope that the many references to additional resources—and suggestions for nontraditional research products—provide guidance and support for both students new to research and current researchers who are new to data-intensive work.

The Explore, Refine, Produce (ERP) workflow for data-intensive research

We partition the workflow of a data-intensive research process into 3 phases: Explore, Refine, and Produce. These phases, collectively the ERP workflow, are visually described in Fig 1A and 1B . In the Explore Phase, researchers “meet” their data: process it, interrogate it, and sift through potential solutions to a problem of interest. In the Refine Phase, researchers narrow their focus to a particularly promising approach, develop prototypes, and organize their code into a clearer narrative. The Produce Phase happens concurrently with the Explore and Refine Phases. In this phase, researchers prepare their work for broader consumption and critique.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

(A) We deconstruct a data-intensive research project into 3 phases, visualizing this process as a tree structure. Each branch in the tree represents a decision that needs to be made about the project, such as data cleaning, refining the scope of the research, or using a particular tool or model. Throughout the natural life of a project, there are many dead ends (yellow Xs). These may include choices that do not work, such as experimentation with a tool that is ultimately not compatible with our data. Dead ends can result in informal learning or procedural fine-tuning. Some dead ends that lie beyond the scope of our current project may turn into a new project later on (open turquoise circles). Throughout the Explore and Refine Phases, we are concurrently in the Produce Phase because research products (closed turquoise circles) can arise at any point throughout the workflow. Products, regardless of the phase that generates their content, contribute to scientific understanding and advance the researcher’s career goals. Thus, the data-intensive research portfolio and corresponding academic CV can be grown at any point in the workflow. (B) The ERP workflow as a nonlinear cycle. Although the tree diagram displayed in Fig 1A accurately depicts the many choices and dead ends that a research project contains, it does not as easily reflect the nonlinearity of the process; Fig 1B’s representation aims to fill this gap. We often iterate between the Explore and Refine Phases while concurrently contributing content to the Produce Phase. The time spent in each phase can vary significantly across different types of projects. For example, hypothesis generation in the Explore Phase might be the biggest hurdle in one project, while effectively communicating a result to a broader audience in the Produce Phase might be the most challenging aspect of another project.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008770.g001

Each phase has an immediate audience—the researcher themselves, their collaborative groups, or the public—that broadens progressively and guides priorities. Each of the 3 phases can benefit from standards that the software development community uses to streamline their code-based pipelines, as well as from principles the design community uses to generate and carry out ideas; many such practices can be adapted to help structure a data-intensive researcher’s workflow. The Explore and Refine Phases provide fodder for the concurrent Produce Phase. We hope that the potential to produce a variety of research products throughout a data-intensive research process, rather than merely at the end of a project, motivates researchers to apply the ERP workflow.

Phase 1: Explore

Data-intensive research projects typically start with a domain-specific question or a particular data set to explore [ 3 ]. There is no fixed, cross-disciplinary rule that defines the point in a workflow by which a hypothesis must be established. This paper adopts an open-minded approach concerning the timing of hypothesis generation [ 4 ], assuming that data-intensive research projects can be motivated by either an explicit, preexisting hypothesis or a new data set about which no strong preconceived assumptions or intuitions exist. The often messy Explore Phase is rarely discussed as an explicit step of the methodological process, but it is an essential component of research: It allows us to gain intuition about our data, informing future phases of the workflow. As we explore our data, we refine our research question and work toward the articulation of a well-defined problem. The following section will address how to reap the benefits of data set and problem space exploration and provide pointers on how to impose structure and reproducibility during this inherently creative phase of the research workflow.

Designing data analysis: Goals and standards of the Explore Phase

Trial and error is the hallmark of the Explore Phase (note the density of “deadends” and decisions made in this phase in Fig 1A ). In “Designerly Ways of Knowing” [ 5 ], the design process is described as a “co-evolution of solution and problem spaces.” Like designers, data-intensive researchers explore the problem space, learn about the potential structure of the solution space, and iterate between the 2 spaces. Importantly, the difficulties we encounter in this phase help us build empathy for an eventual audience beyond ourselves. It is here that we experience firsthand the challenges of processing our data set, framing domain research questions appropriate to it, and structuring the beginnings of a workflow. Documenting our trial and error helps our own work stay on track in addition to assisting future researchers facing similar challenges.

One end goal of the Explore Phase is to determine whether new questions of interest might be answered by leveraging existing software tools (either off the shelf or with minor adjustments), rather than building new computational capabilities ourselves. For example, during this phase, a common activity includes surveying the software available for our data set or problem space and estimating its utility for the unique demands of our current analysis. Through exploration, we learn about relevant computational and analysis tools while concurrently building an understanding of our data.

A second important goal of the Explore Phase is data cleaning and developing a strategy to analyze our data. This is a dynamic process that often goes hand in hand with improving our understanding of the data. During the Explore Phase, we redesign and reformat data structures, identify important variables, remove redundancies, take note of missing information, and ponder outliers in our data set. Once we have established the software tools—the programming language, data analysis packages, and a handful of the useful functions therein—that are best suited to our data and domain area, we also start putting those tools to use [ 6 ]. In addition, during the Explore Phase, we perform initial tests, build a simple model, or create some basic visualizations to better grasp the contents of our data set and check for expected outputs. Our research is underway in earnest now, and this effort will help us to identify what questions we might be able to ask of our data.

The Explore Phase is often a solo endeavor; as shown in Fig 1A , our audience is typically our current or future self. This can make navigating the phase difficult, especially for new researchers. It also complicates a third goal of this phase: documentation. In this phase, we ourselves are our only audience, and if we are not conscientious documenters, we can easily end up concluding the phase without the ability to coherently describe our research process up to that point. Record keeping in the Explore Phase is often subject to our individual style of approaching problems. Some styles work in real time, subsetting or reconfiguring data as ideas occur. More methodical styles tend to systematically plan exploratory steps, recording them before taking action. These natural tendencies impact the state of our analysis code, affecting its readability and reproducibility.

However, there are strategies—inspired by analogous software development principles—that can help set us up for success in meeting the standards of reproducibility [ 7 ] relevant to a scientifically sound research workflow. These strategies impose a semblance of order on the Explore Phase. To avoid concerns of premature optimization [ 8 ] while we are iterating during this phase, documentation is the primary goal, rather than fine-tuning the code structure and style. Documentation enables the traceability of a researcher’s workflow, such that all efforts are replicable and final outcomes are reproducible.

Analogies to software development in the Explore Phase

Documentation: code and process..

Software engineers typically value formal documentation that is readable by software users. While the audience for our data analysis code may not be defined as a software user per se, documentation is still vital for workflow development. Documentation for data analysis workflows can come in many forms, including comments describing individual lines of code, README files orienting a reader within a code repository, descriptive commit history logs tracking the progress of code development, docstrings detailing function capabilities, and vignettes providing example applications. Documentation provides both a user manual for particular tools within a project (for example, data cleaning functions), and a reference log describing scientific research decisions and their rationale (for example, the reasons behind specific parameter choices).

In the Explore Phase, we may identify with the type of programmer described by Brant and colleagues as “opportunistic” [ 9 ]. This type of programmer finds it challenging to prioritize documenting and organizing code that they see as impermanent or a work in progress. “Opportunistic” programmers tend to build code using others’ tools, focusing on writing “glue” code that links preexisting components and iterate quickly. Hartmann and colleagues also describe this mash-up approach [ 10 ]. Rather than “opportunistic programmers,” their study focuses on “opportunistic designers.” This style of design “search[es] for bridges,” finding connections between what first appears to be different fields. Data-intensive researchers often use existing tools to answer questions of interest; we tend to build our own only when needed.

Even if the code that is used for data exploration is not developed into a software-based final research product, the exploratory process as a whole should exist as a permanent record: Future scientists should be able to rerun our analysis and work from where we left off, beginning from raw, unprocessed data. Therefore, documenting choices and decisions we make along the way is crucial to making sure we do not forget any aspect of the analysis workflow, because each choice may ultimately impact the final results. For example, if we remove some data points from our analyses, we should know which data points we removed—and our reason for removing them—and be able to communicate those choices when we start sharing our work with others. This is an important argument against ephemerally conducting our data analysis work via the command line.

Instead of the command line, tools like a computational notebook [ 11 ] can help capture a researcher’s decision-making process in real time [ 12 ]. A computational notebook where we never delete code, and—to avoid overwriting named variables—only move forward in our document, could act as “version control designed for a 10-minute scale” that Brant and colleagues found might help the “opportunistic” programmer. More recent advances in this area include the reactive notebook [ 13 – 14 ]. Such tools assist documentation while potentially enhancing our creativity during the Explore Phase. The bare minimum documentation of our Explore Phase might therefore include such a notebook or an annotated script [ 15 ] to record all analyses that we perform and code that we write.

To go a step beyond annotated scripts or notebooks, researchers might employ a version control system such as Git. With its issues, branches, and informative commit messages, Git is another useful way to maintain a record of our trial-and-error process and track which files are progressing toward which goals of the overall project. Using Git together with a public online hosting service such as GitHub allows us to share our work with collaborators and the public in real time, if we so choose.

A researcher dedicated to conducting an even more thoroughly documented Explore Phase may take Ford’s advice and include notes that explicitly document our stream of consciousness [ 16 ]. Our notes should be able to efficiently convey what failed, what worked but was uninteresting or beyond scope of the project, and what paths of inquiry we will continue forward with in more depth ( Fig 1A ). In this way, as we transition from the Explore Phase to the Refine Phase, we will have some signposts to guide our way.

Testing: Comparing expectations to output.

As Ford [ 16 ] explains, we face competing goals in the Explore Phase: We want to get results quickly, but we also want to be confident in our answers. Her strategy is to focus on documentation over tests for one-off analyses that will not form part of a larger research project. However, the complete absence of formal tests may raise a red flag for some data scientists used to the concept of test-driven development . This is a tension between the code-based work conducted in scientific research versus software development: Tests help build confidence in analysis code and convince users that it is reliable or accurate, but tests also imply finality and take time to write that we may not be willing to allocate in the experimental Explore Phase. However, software development style tests do have useful analogs in data analysis efforts: We can think of tests, in the data analysis sense, as a way of checking whether our expectations match the reality of a piece of code’s output.

Imagine we are looking at a data set for the first time. What weird things can happen? The type of variable might not be what we expect (for example, the integer 4 instead of the float 4.0). The data set could also include unexpected aspects (for example, dates formatted as strings instead of numbers). The amount of missing data may be larger than we thought, and this missingness could be coded in a variety of ways (for example, as a NaN, NULL, or −999). Finally, the dimensions of a data frame after merging or subsetting it for data cleaning may not match our expectations. Such gaps in expectation versus reality are “silent faults” [ 17 ]. Without checking for them explicitly, we might proceed with our analysis unaware that anything is amiss and encode that error in our results.

For these reasons, every data exploration should include quantitative and qualitative “gut checks” [ 18 ] that can help us diagnose an expectation mismatch as we go about examining and manipulating our data. We may check assumptions about data quality such as the proportion of missing values, verify that a joined data set has the expected dimensions, or ascertain the statistical distributions of well-known data categories. In this latter case, having domain knowledge can help us understand what to expect. We may want to compare 2 data sets (for example, pre- and post-processed versions) to ensure they are the same [ 19 ]; we may also evaluate diagnostic plots to assess a model’s goodness of fit. Each of the elements that gut checks help us monitor will impact the accuracy and direction of our future analyses.

We perform these manual checks to reassure ourselves that our actions at each step of data cleaning, processing, or preliminary analysis worked as expected. However, these types of checks often rely on us as researchers visually assessing output and deciding if we agree with it. As we transition to needing to convince users beyond ourselves of the correctness of our work, we may consider employing defensive programming techniques that help guard against specific mistakes. An example of defensive programming in the Julia language is the use of assertions, such as the @assert macro to validate values or function outputs. Another option includes writing “chatty functions” [ 20 ] that signal a user to pause, examine the output, and decide if they agree with it.

When to transition from the Explore Phase: Balancing breadth and depth

A researcher in the Explore Phase experiments with a variety of potential data configurations, analysis tools, and research directions. Not all of these may bear fruit in the form of novel questions or promising preliminary findings. Learning how to find a balance between the breadth and depth of data exploration helps us understand when to transition to the Refine Phase of data-intensive research. Specific questions to ask ourselves as we prepare to transition between the Explore Phase and the Refine Phase can be found in Box 2 .

Box 2. Questions

This box provides guiding questions to assist readers in navigating through each workflow phase. Questions pertain to planning, organization, and accountability over the course of workflow iteration.

Questions to ask in the Explore Phase

- Good: Ourselves (e.g., Code includes signposts refreshing our memory of what is happening where.)

- Better: Our small team who has specialized knowledge about the context of the problem.

- Best: Anyone with experience using similar tools to us.

- Good: Dead ends marked differently than relevant and working code.

- Better: Material connected to a handful of promising leads.

- Best: Material connected to a clearly defined scope.

- Good: Backed up in a second location in addition to our computer.

- Better: Within a shared space among our team (e.g., Google Drive, Box, etc.).

- Best: Within a version control system (e.g., GitHub) that furnishes a complete timeline of actions taken.

- Good: Noted in a separate place from our code (e.g., a physical notebook).

- Better: Noted in comments throughout the code itself, with expectations informally checked.

- Best: Noted systematically throughout code as part of a narrative, with expectations formally checked.

Questions to ask in the Refine Phase

- Who is in our team?

- Consider career level, computational experience, and domain-specific experience.

- How do we communicate methodology with our teammates’ skills in mind?

- What reproducibility tools can be agreed upon?

- How can our work be packaged into impactful research products?

- Can we explain the same important results across different platforms (e.g., blog post in addition to white paper)?

- How can we alert these people and make our work accessible?

- How can we use narrative to make this clear?

Questions to ask in the Produce Phase

- Do we have more than 1 audience?

- What is the next step in our research?

- Can we turn our work into more than 1 publishable product?

- Consider products throughout the entire workflow.

- See suggestions in the Tool development guide ( Box 4 ).

Imposing structure at certain points throughout the Explore Phase can help to balance our wide search for solutions with our deep dives into particular options. In an analogy to the software development world, we can treat our exploratory code as a code release—the marker of a stable version of a piece of software. For example, we can take stock of the code we have written at set intervals, decide what aspects of the analysis conducted using it seem most promising, and focus our attention on more formally tuning those parts of the code. At this point, we can also note the presence of research “dead ends” and perhaps record where they fit into our thought process. Some trains of thought may not continue into the next phase or become a formal research product, but they can still contribute to our understanding of the problem or eliminate a potential solution from consideration. As the project matures, computational pipelines are established. These inform project workflow, and tools, such as Snakemake and Nextflow, can begin to be used to improve the flexibility and reproducibility of the project [ 21 – 23 ]. As we make decisions about which research direction we are going to pursue, we can also adjust our file structure and organize files into directories with more informative names.

Just as Cross [ 5 ] finds that a “reasonably-structured process” leads to design success where “rigid, over-structured approaches” find less success, a balance between the formality of documentation and testing and the informality of creative discovery is key to the Explore Phase of data-intensive research. By taking inspiration from software development and adapting the principles of that arena to fit our data analysis work, we add enough structure to this phase to ease transition into the next phase of the research workflow.

Phase 2: Refine

Inevitably, we reach a point in the Explore Phase when we have acquainted ourselves with our data set, processed and cleaned it, identified interesting research questions that might be asked using it, and found the analysis tools that we prefer to apply. Having reached this important juncture, we may also wish to expand our audience from ourselves to a team of research collaborators. It is at this point that we are ready to transition to the Refine Phase. However, we should keep in mind that new insights may bring us back to the Explore Phase: Over the lifetime of a given research project, we are likely to cycle through each workflow phase multiple times.

In the Refine Phase, the extension of our target audience demands a higher standard for communicating our research decisions as well as a more formal approach to organizing our workflow and documenting and testing our code. In this section, we will discuss principles for structuring our data analysis in the Refine Phase. This phase will ultimately prepare our work for polishing into more traditional research products, including peer-reviewed academic papers.

Designing data analysis: Goals and standards of the Refine Phase

The Refine Phase encompasses many critical aspects of a data-intensive research project. Additional data cleaning may be conducted, analysis methodologies are chosen, and the final experimental design is decided upon. Experimental design may include identifying case studies for variables of interest within our data. If applicable, it is during this phase that we determine the details of simulations. Preliminary results from the Explore Phase inform how we might improve upon or scale up prototypes in the Refine Phase. Data management is essential during this phase and can be expanded to include the serialization of experimental setups. Finally, standards of reproducibility should be maintained throughout. Each of these aspects constitutes an important goal of the Refine Phase as we determine the most promising avenues for focusing our research workflow en route to the polished research products that will emerge from this phase and demand even higher reproducibility standards.

All of these goals are developed in conjunction with our research team. Therefore, decisions should be documented and communicated in a way that is reproducible and constructive within that group. Just as the solitary nature of the Explore Phase can be daunting, the collaboration that may happen in the Refine Phase brings its own set of challenges as we figure out how to best work together. Our team can be defined as the people who participate in developing the research question, preparing the data set it is applied to, coding the analysis, or interpreting the results. It might also include individuals who offer feedback about the progress of our work. In the context of academia, our team usually includes our laboratory or research group. Like most other aspects of data-intensive research, our team may evolve as the project evolves. But however we define our team, its members inform how our efforts proceed during the Refine Phase: Thus, another primary goal of the Refine Phase is establishing group-based standards for the research workflow. Specific questions to ask ourselves during this phase can be found in Box 2 .

In recent years, the conversation on standards within academic data science and scientific computing has shifted from “best” practices [ 24 ] to “good enough” practices [ 25 ]. This is an important distinction when establishing team standards during the Refine Phase: Reproducibility is a spectrum [ 26 ], and collaborative work in data-intensive research carries unique demands on researchers as scholars and coworkers [ 27 ]. At this point in the research workflow, standards should be adopted according to their appropriateness for our team. This means talking among ourselves not only about scientific results, but also about the computational experimental design that led to those results and the role that each team member plays in the research workflow. Establishing methods for effective communication is therefore another important goal in the Refine Phase, as we cannot develop group-based standards for the research workflow without it.

Analogies to software development in the Refine Phase

Documentation as a driver of reproducibility..

The concept of literate programming [ 8 ] is at the core of an effective Refine Phase. This philosophy brings together code with human-readable explanations, allowing scientists to demonstrate the functionality of their code in the context of words and visualizations that describe the rationale for and results of their analysis. The computational notebooks that were useful in the Explore Phase are also applicable here, where they can assist with team-wide discussions, research development, prototyping, and idea sharing. Jupyter Notebooks [ 28 ] are agnostic to choice of programming language and so provide a good option for research teams that may be working with a diverse code base or different levels of comfort with a particular programming language. Language-specific interfaces such as R’s RMarkdown functionality [ 29 ] and Literate.jl or the reactive notebook put forward by Pluto.jl in the Julia programming language furnish additional options for literate programming.

The same strategies that promote scientific reproducibility for traditional laboratory notebooks can be applied to the computational notebook [ 30 ]. After all, our data-intensive research workflow can be considered a sort of scientific experiment—we develop a hypothesis, query our data, support or reject our hypothesis, and state our insights. A central tenet of scientific reproducibility is recording inputs relevant to a given analysis, such as parameter choices, and explaining any calculation used to obtain them so that our outputs can later be verifiably replicated. Methodological details—for example, the decision to develop a dynamic model in continuous time versus discrete time or the choice of a specific statistical analysis over alternative options—should also be fully explained in computational notebooks developed during the Refine Phase. Domain knowledge may inform such decisions, making this an important part of proper notebook documentation; such details should also be elaborated in the final research product. Computational research descriptions in academic journals generally include a narrative relevant to their final results, but these descriptions often do not include enough methodological detail to enable replicability, much less reproducibility. However, this is changing with time [ 31 , 32 ].

As scientists, we should keep a record of the tools we use to obtain our results in addition to our methodological process. In a data-intensive research workflow, this includes documenting the specific version of any software that we used, as well as its relevant dependencies and compatibility constraints. Recording this information at the top of the computational notebook that details our data science experiment allows future researchers—including ourselves and our teams—to establish the precise computational environment that was used to run the original research analysis. Our chosen programming language may supply automated approaches for doing this, such as a package manager , simplifying matters and painlessly raising the standards of reproducibility in a research team. The unprecedented levels of reproducibility possible in modern computational environments have produced some variance in the expectations of different research communities; it behooves the research team to investigate the community-level standards applicable to our specific domain science and chosen programming language.

A notebook can include more than a deep dive into a full-fledged data science experiment. It can also involve exploring and communicating basic properties of the data, whether for purposes of training team members new to the project or for brainstorming alternative possible approaches to a piece of research. In the Exploration Phase, we have discovered characteristics of our data that we want our research team to know about, for example, outliers or unexpected distributions, and created preliminary visualizations to better understand their presence. In the Refine Phase, we may choose to improve these initial plots and reprise our data processing decisions with team members to ensure that the logic we applied still holds.

Computational notebooks can live in private or public repositories to ensure accessibility and transparency among team members. A version control system such as Git continues to be broadly useful for documentation purposes in the Refine Phase, beyond acting as a storage site for computational notebooks. Especially as our team and code base grows larger, a history of commits and pull requests helps keep track of responsibilities, coding or data issues, and general workflow.

Importantly however, all tools have their appropriate use cases. Researchers should not develop an overt reliance on any one tool and should learn to recognize when different tools are required. For example, computational notebooks may quickly become unwieldy for certain projects and large teams, incurring technical debt in the form of duplications or overwritten variables. As our research project grows in complexity and size, or gains team members, we may want to transition to an Integrated Development Environment (IDE) or a source code editor —which interact easily with container environments like Docker and version control systems such as GitHub—to help scale our data analysis, while retaining important properties like reproducibility.

Testing and establishing code modularity.

Code in data-intensive research is generally written as a means to an end, the end being a scientific result from which researchers can draw conclusions. This stands in stark contrast to the purpose of code developed by data engineers or computer scientists, which is generally written to optimize a mechanistic function for maximum efficiency. During the Refine Phase, we may find ourselves with both analysis-relevant and mechanistic code , especially in “big data” statistical analyses or complex dynamic simulations where optimized computation becomes a concern. Keeping the immediate audience of this workflow phase, our research team, at the forefront of our mind can help us take steps to structure both mechanistic and analysis code in a useful way.

Mechanistic code, which is designed for repeated use, often employs abstractions by wrapping code into functions that apply the same action repeatedly or stringing together multiple scripts into a computational pipeline. Unit tests and so-called accessor functions or getter and setter functions that extract parameter values from data structures or set new values are examples of mechanistic code that might be included in a data-intensive research analysis. Meanwhile, code that is designed to gain statistical insight into distributions or model scientific dynamics using mathematical equations are 2 examples of analysis code. Sometimes, the line between mechanistic code and analysis code can be a blurry one. For example, we might write a looping function to sample our data set repeatedly, and that would classify as mechanistic code. But that sampling may be designed to occur according to an algorithm such as Markov Chain Monte Carlo that is directly tied to our desire to sample from a specific probability distribution; therefore, this could be labeled analysis and mechanistic code. Keep your audience in mind and the reproducibility of your experiment when considering how to present your code.

It is common practice to wrap code that we use repeatedly into functions to increase readability and modularity while reducing the propensity for user-induced error. However, the scripts and programming notebooks so useful to establishing a narrative and documenting work in the Refine Phase are set up to be read in a linear fashion. Embedding mechanistic functions in the midst of the research narrative obscures the utility of the notebooks in telling the research story and generally clutters up the analysis with a lot of extra code. For example, if we develop a function to eliminate the redundancy of repeatedly restructuring our data to produce a particular type of plot, we do not need to showcase that function in the middle of a computational notebook analyzing the implications of the plot that is created—the point is the research implications of the image, not the code that made the plot. Then where do we keep the data-reshaping, plot-generating code?

Strategies to structure the more mechanistic aspects of our analysis can be drawn from common software development practices. As our team grows or changes, we may require the same mechanistic code. For example, the same data-reshaping, plot-generating function described earlier might be pulled into multiple computational experiments that are set up in different locations, computational notebooks, scripts, or Git branches. Therefore, a useful approach would be to start collecting those mechanistic functions into their own script or file, sometimes called “helpers” or “utils,” that acts as a supplement to the various ongoing experiments, wherever they may be conducted. This separate script or file can be referenced or “called” at the beginning of the individual data analyses. Doing so allows team members to benefit from collaborative improvements to the mechanistic code without having to reinvent the wheel themselves. It also preserves the narrative properties of team members’ analysis-centric computational notebooks or scripts while maintaining transparency in basic methodologies that ensure project-wide reproducibility. The need to begin collecting mechanistic functions into files separate from analysis code is a good indicator that it may be time for the research team to supplement computational notebooks by using a code editor or IDE for further code development.