Wait, but Wi-Fi?

Transmit Power Control Considerations

Proper configuration of Transmit Power Control (TPC) settings can help to ensure that your Access Point (AP) does not speak too loudly. If your AP is transmitting at 18dBm and an associated client station (STA) is at the cell edge and only capable of transmitting at 15dBm, your client will be able to hear the AP transmission, but the AP won’t be able to hear the client which leads to retransmissions and thus reduced performance.

Wireless network design is ultimately dependent upon the clients it is to support, so we will want to have an idea of what our intended clients are capable of. As an example, one of my customer’s clients is an HP EliteBook 8470p laptop workstation which has a Broadcom BCM943228HM4L Wi-Fi adapter. According to the product specification web page for this particular model, I was able to find that it is capable of transmitting at around 15dBm. If this is my customer’s least capable device, I would not want my AP to transmit louder than 15dBm either.

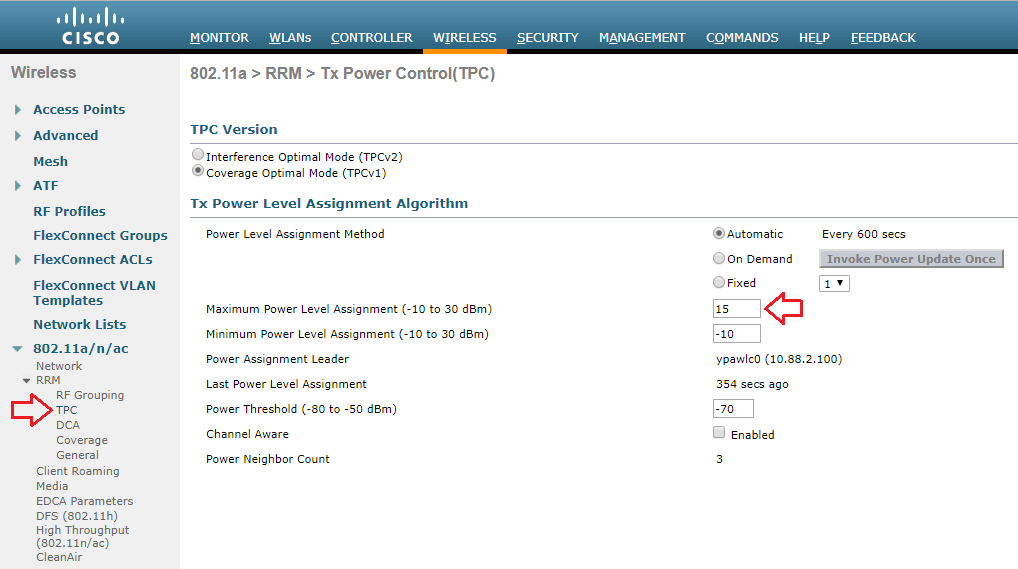

My customer is using a Cisco 3504 Wireless Controller running AireOS version 8.8. I am able to globally configure the Maximum Power Level Assignment to 15dBm.

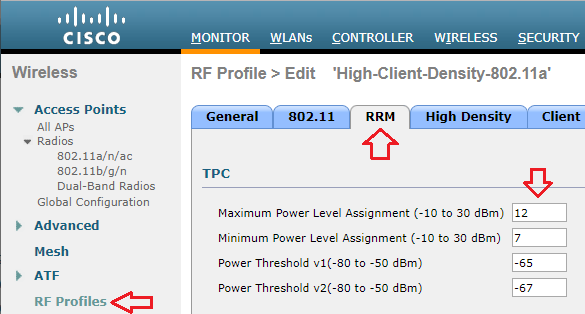

If the same controller were managing multiple locations with different requirements, I can also set a Maximum Power Level Assignment for different RF Profiles.

Though the maximum power level is configured in dBm, Cisco uses a series of numbers to represent levels of power. Phil Morgan of NC-Expert wrote an article titled WLC and AP Power settings in which he discusses Cisco power levels in further detail. In his article, he discusses how we can determine what the power levels represent as they vary by AP model, band (2.4 vs 5GHz), and even channel groupings (i.e. U-NII 1, 2, 2e, 3).

I also stumbled upon an excellent post by Maxim Risman in the Cisco Community titled Cisco Access point 2802i Tx Power Chart where he demonstrates the use of another very helpful command which summarizes the power levels of all APs: show advanced 802.11a txpower

Note that the range for the power levels actually does not change, but rather TPC is limiting the highest level that can be used.

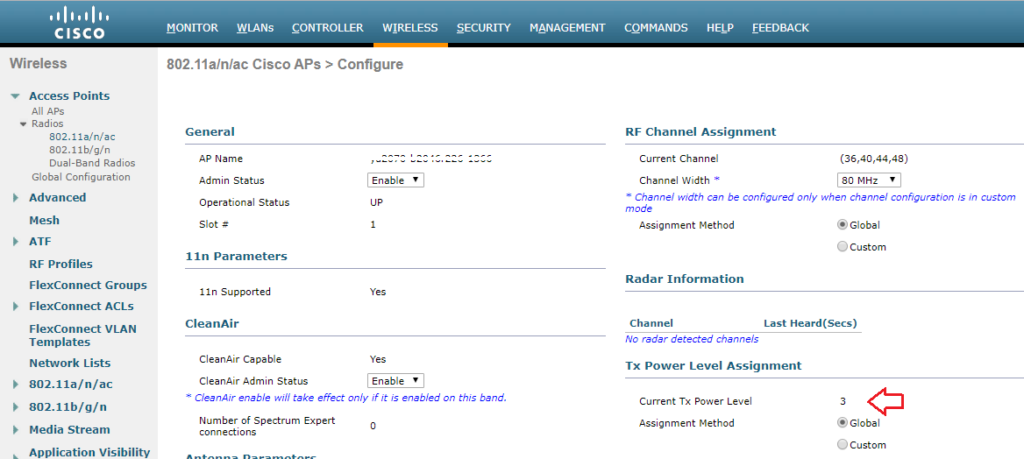

The current power level setting can also be found in the web GUI by navigating to Wireless > Access Points > Radios. There, you can see the power level for all of your APs in a column, or you can dive in to the configuration of a radio.

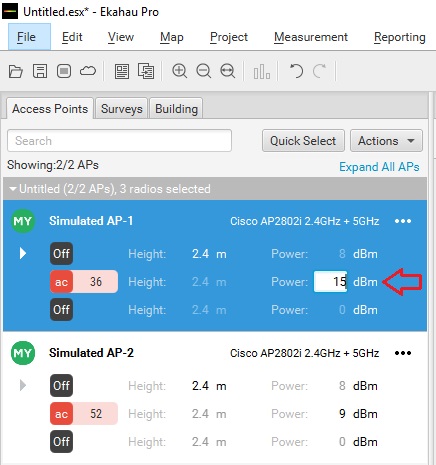

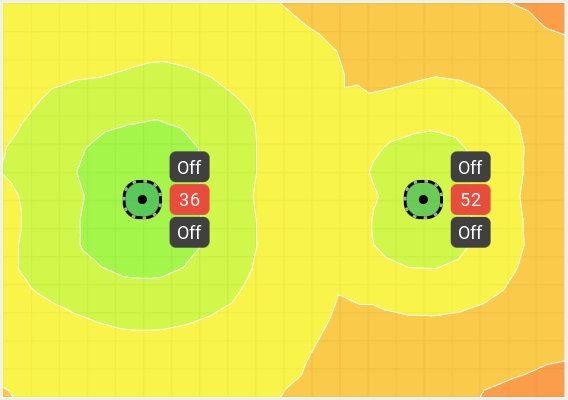

When performing predictive site surveys with Ekahau Pro site survey software, we have the ability to adjust the transmit power with which to generate our expected heat maps.

We can get an idea of how this difference may affect our design in the real world.

If you are interested in getting deeper into Cisco’s TPC implementation, you may want to check out a whitepaper they have published titled Transmit Power Control (TPC) Algorithm .

Published by Stephen

View all posts by Stephen

- Networking 101

Cisco Wireless Transmit Power Control

Power substation outside a VERY large data center in Atlanta,GA.

I’m going to start out by telling you something you probably already know. Every vendor has their own way of doing things. Sometimes it makes perfect sense, and other times you end up scratching your head wondering why that particular vendor implemented this feature or product. Since I have been spending a lot more time on wireless these days, I came across an issue that forced me to reconsider how transmit power control(TPC) actually works in a Cisco wireless deployment. I thought I would impart some of this information to you, dear reader, in the hopes that it may help you. If you spend a lot of time inside Cisco wireless LAN controllers, this may not be anything new to you.

The Need For TPC

If you have been around wireless long enough, you have probably dealt with wireless installs where all of the access points(AP) were functioning autonomously. While this isn’t a big deal in smaller environments, consider how much design work goes into a network with autonomous access points that number into the hundreds. It isn’t as simple as just deciding on channels and spinning all the access points up. You also have to consider the power levels of the respective access points. Failure to do so can result in the image below where the AP is clearly heard by the client device, but the AP cannot hear the client since it is transmitting at a higher power level than the client can match.

Now consider the use of a wireless LAN controller to manage all of those APs. In addition to things like dynamic channel assignment, you can also have it adjust the transmit power levels of the APs. This can come in handy when you have an AP fail and need the other APs to increase their transmit power to fill the gap that exists since that failed AP is no longer servicing clients. I should point out that proper design of a wireless network with respect to the client transmit power capabilities should NEVER be overlooked. You ALWAYS want to be aware of what power levels your clients can transmit at. It helps to reduce the problem in the image above.

There’s also the problem that can arise when too many APs can hear each other. It isn’t just about the clients. Wireless systems which adhere to the IEEE 802.11 standard are a half duplex medium. Only one device can talk at a time on a given channel. Either a client or the AP will talk, but not both at once. If an AP can hear another AP on the same channel at a usable signal, the airtime must be shared between those APs. Depending on the number of SSID’s in use, this can dramatically reduce the amount of airtime available for an AP to service a client. You can see some actual numbers with regard to SSIDs and APs in this blog post by Andrew von Nagy .

As you can see from two quick examples, there is a need to control the power level in which an AP will transmit. On controller based wireless networks(and even on the newer controller-less solutions), this is done automatically. I wouldn’t advise you turn that off unless you really know what you are doing and you have the time to plan it all out beforehand.

The Cisco Approach

On wireless LAN controllers, TPC is a function of Radio Resource Management(RRM). The specifics can be found here . I’ll spare you the read and give you the high points.

- The TPC algorithm is only concerned with reducing power levels. Increases in power levels are covered by Coverage Hole Detection and Correction algorithm.

- TPC runs in 10 minute intervals.

- A minimum of 4 APs are required for TPC to work.

It is the last point that I want to focus on, because the first two are pretty self explanatory. The reasoning behind the 4 AP minimum for TPC is as follows:

“For TPC to work ( or to even have a need for TPC ) 4 APS must be in proximity of each other. Why? Because on 2.4 GHz you only have three channels that do not overlap… Once you have a fourth AP you need to potentially adjust power down to avoid co channel interference. With 3 APS full power will not cause this issue.”

Those are not my words. They came from someone within Cisco that is focused on wireless. Since that person didn’t know I would publish that, I will not name said person. The explanation though, makes sense.

***Update – It appears that the Cisco documentation regarding TPC is a bit murky. Jeff Rensink pointed out in the comments below that TPC will also increase power levels. Although CHD will increase based on client information, I didn’t use any clients in my testing, as Jeff rightly assumed. The power increases I saw once I started removing AP’s from the WLC could not have been attributed to CHD adjustments. Read his comment below as he makes some very valid points. The NDP reference and accompanying link in his comment is fairly interesting.

Let’s see it in action to validate what Cisco’s documentation says.

TPC Testing

I happen to have a Cisco WLC 2504 handy with 4 APs. I set it up in my home office and only maintained about 10 feet separation from the APs. Ideally, I would test it with the APs a lot farther apart, but I did put some barriers around the APs to give some extra attenuation to the signal. I also only did testing on the 5GHz band. I disabled all of the 2.4GHz radios because I don’t need to give any of my neighbors a reason to hate me. Blasting 5GHz is less disruptive to their home wireless networks than 2.4GHz is due to the signals traveling farther / less attenuation of 2.4GHz vs 5GHz signals /antenna aperture. 🙂

Here you can see the available settings for TPC in the WLC GUI. This particular controller is running 7.6 code, so your version may vary.

- You can either set TPC to run automatically, on demand, or at a fixed power rate on all APs. TPC is band specific, so if you want different settings for 2.4GHz and 5GHz respectively, you can have that.

- Maximum and minimum settings for transmit power are available. The defaults are 30dBm for maximum power and -10dBm for minimum power.

- The power threshold is the minimum level at which you need to hear the third AP for the TPC algorithm to run. The default is -70dBm. You can set it higher or lower depending on your needs. High density environments might require a level stronger than -70dBm, with -50dBm being the strongest level supported. If you don’t necessarily need to run things like voice, you might be able to get away with a weaker threshold, but you cannot go beyond -80dBm.

A Quick Sidebar on Maximum Transmit Power in 5GHz

I set up the WLC with 3 APs active on 5GHz only. You can see that the power levels on the 3 APs are set to 1 in the image further down, which is maximum power according to Cisco. While it seems odd that max power would be a 1 and not some higher number, consider the fact that there are multiple maximum transmit power levels depending on which UNII band you are using in 5GHz. As a general reference, 20dBm would be 100mW and 14dBm would be 25mW. You could get 200mW(23dBm) of power using a UNII-3 channel vs UNII-1, which is maxed out 32mW(15dBm). That is a HUGE difference.

- 1 – 15dBm

- 2 – 12dBm

- 3 – 9dBm

- 4 – 6dBm

- 5 – 3dBm

- 1 – 17dBm

- 2 – 14dBm

- 3 – 11dBm

- 4 – 8dBm

- 5 – 5dBm

- 6 – 2dBm

- 1 – 23dBm

- 2 – 20dBm

- 3 – 17dBm

- 4 – 14dBm

- 5 – 11dBm

- 6 – 8dBm

- 7 – 5dBm

To see the supported power levels in terms of dBm on 5GHz, you can run the following command on the CLI of the WLC: show ap config 802.11a <ap name> The output will look something like this after you go through a handful of screens showing other stuff:

***Update – Brian Long wrote a blog post on this very thing! You can read it here .

Back To The Testing…

You can see in the image below that with 3 APs active, they are all running at power level 1, which is the default when the radios come online.

So let’s see what happens when I add the fourth AP. If our understanding of TPC is correct, we should see the power levels come down since the APs are so close to each other and will have a signal strength of well above -70dBm between each other.

Note – Power level decreases happen in single increments only, every time the TPC algorithm runs(every 10 minutes). To put it another way, it downgrades by 3dB max each cycle. Sam Clements pointed out to me via Twitter that when power levels increase, it can happen much more rapidly since the Coverage Hole Detection(CHD) and Correction algorithm is responsible for power increases.

If you want to see this work on the CLI in real time, you can issue the following command: debug airewave-director power enable

After I had waited for over half an hour, I decided to power off one more AP. When I brought it back online, I saw all 3 of the APs slowly go back to a power level of 1. Here’s the first change I saw in the 3 remaining APs:

It’s All In The Details

For wireless surveys, my company uses the Ekahau Site Survey product. It is a really neat survey tool and we use it for on site assessments as well as predictive surveys. When you define the requirements of the project, you can choose from a bunch of different vendor specific scenarios, or general wireless scenarios. I can apply those requirements to a predictive survey, or an on site survey where I am trying to determine if the existing coverage/capacity is good enough for the business needs.

Here’s a screen shot of the default requirements for the “Cisco Voice” scenario found in version 7.6.4 of Ekahau’s Site Survey program:

Closing Thoughts

Understanding how the TPC function works is pretty important when designing Cisco wireless networks. Failure to consider what all is involved in regards to transmit power on your APs could(not WILL, but COULD) lead to problems in the wireless network’s operation. However, if you want to manually set transmit power, that’s an option as well. Opinions differ on running RRM. I’m not sure there is a right or wrong answer. It depends. 🙂 I will say that I almost never see Cisco wireless implementations where RRM is not being used.

I don’t want to end this post without mentioning that some networks may be perfectly fine running APs at max power, especially on the 5GHz side. Your coverage may be enough to where there is minimal channel overlap(easily achievable in 5GHz with 20MHz channels and the use of all 3 UNII bands), and each AP can hear one or two neighboring APs at a decent level due to good cell overlap. You just might not have enough APs to trigger the TPC algorithm to run. That doesn’t mean “you are doing it wrong”. If it works for the business and all your users are fine, who am I to tell you that you need to “fix” it.

Hopefully this was beneficial to you if you needed a clearer understanding of how Cisco’s TPC function works. If you already have a good understanding of TPC and managed to read this far, feel free to shame humiliate correct me in the comments.

11 Responses to Cisco Wireless Transmit Power Control

Nice write up of the TPC process with actual testing. I would just make one correction.

The normal TPC algorithm should also raise power levels in addition to lowering them. This is evidenced in your testing as the powers raise up on the TCP interval when you took APs away. This is needed so that if an AP fails in real life, the surrounding APs can dynamically increase their power levels. The document that you linked actually says this. Although it also says that TCP is only used to decrease power (as you noted in your article). So it’s contradicting itself.

With coverage hole detection, the APs increase power in response to clients being connected at a low signal level. I haven’t seen any mention of CHD working to raise power in the absence of clients. So I don’t believe it has the capability to do so. Thus, if it were true that CHD was the only means to raise AP power, AP power would never raise without associated clients. I’ guessing in your tests, you didn’t have clients associated.

I don’t write this to pick on your article (it was very good). I just wanted to point out a common misconception that is unfortunately created by Cisco’s own documentation on the subject.

The other thing that bugs me about the RRM doc that you referenced is the inference that neighboring APs will be heard at lower RSSI levels as their power decreases. This is where they are talking about the TPC algorithm and how they use the power threshold value to determine if they should raise/lower power or not based on the 3rd loudest neighbor. The problem with that is that Neighbor Discovery Protocol (NDP) messages are always sent at the highest power/lowest data rate. So current AP power does not affect how loud a neighbor is heard, because TPC uses those NDP frames in its calculations. But part of the NDP information is the power level used to send the frame. So the TPC calculation can still do the math to figure out what power level is appropriate based on the threshold value.

For as important of a technology to understand as RRM is, Cisco definitely doesn’t make it easy to figure out. The article below helps fill in some information in regards to RRM. One of the nuggets is actually the reason why your power levels weren’t rising back up as quickly as you expected.

http://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/td/docs/wireless/controller/technotes/7-4/RRM_DG_74.html

Your comment is exactly the kind of additional information I was looking for in terms of corrections to my understanding of TPC, so I am grateful that you took the time to write it. There was a paragraph that I cut out of the blog post last night before publishing that I wish I would have left in after reading your comment. In that paragraph, I mentioned that when I powered off an AP, I still saw the TPC algorithm running via the “Last Power Level Assignment” field under the TPC page for 802.11a/n/ac. When I was proofreading, I pulled that paragraph because I thought it contradicted the RRM documentation stating that the TPC algorithm only cares about power decreases. It seemed like it would cause more confusion if I left it in.

After reading your comment, it makes a lot more sense now. I also appreciate the tidbit around NDP and how those messages actually work independent of the assigned power level to the AP.

Thanks again for the additional information. If I have some time, I will probably amend the post and reference your comment.

Great read Matthew. This is a keeper. 🙂

1. Regarding the comment from Cisco:

“For TPC to work (or to even have a need for TPC) 4 APs must be in proximity of each other. Why? Because on 2.4 GHz you only have three channels that do not overlap… Once you have a fourth AP you need to potentially adjust power down to avoid co-channel interference. With 3 APs full power will not cause this issue.”

DA > This is hideous…as you seemed to eluded to. The two major issues with this statement is that 1) it takes into consideration that you’re doing your testing inside a Faraday cage, and 2) there’s no such thing as adjacent channel interference. 🙁 I just had to get this off my chest. 🙂

While I can think of an advantage or two of using arbitrary numbers (e.g. 1-8) to represent power levels, the fact that they are so disparate across bands makes it non-intuitive for the Cisco novice. 1 should equal 1, 2 = 2, 3 = 3, etc…but no…of course not. 🙁 Confusion within the GUI is bad enough….but it’s much worse than that. Trying to assure maximum capacity, by uniformly mixing UNII-1 and UNII-3 channels (especially when DFS isn’t supported by many of your client devices), wouldn’t you end up with large cells and mid-sized cells unless TPC kicks in?

3. Question

It just seems silly to disable TPC unless there’s a 4th Cisco AP present in the network. Jeff mentioned that NDP is used in TPC calculations. Is that to say that neighboring APs can be used as TPC’s required-and-mysterious “4th AP”?

Again, great article. Very helpful.

Regarding your point number 1, I think they assume that anyone operating a wireless network will ONLY use 1, 6, and 11 inside the US. Of course, you and I both know that there are MANY networks run by people who just don’t seem to care about that.

As for point 2, it is fairly confusing when considering power levels at 5GHz. I would rather just have the scale start at 1 using the lowest level(-1dBm or 2dBm), and then go all the way up to whatever number on that scale represents 23dBm. You would still need to know what UNII band your 5GHz radio was on to know if you were at max power, but if I knew that power level 4 was always represented by 14dBm, I would know the radio was at 25mW. On the other hand, I can always look at power levels inside a Cisco WLC and know right away who is at max power, even though I still need to know what UNII band the radio is on.

To your point 3, my understanding of TPC is that it won’t even kick in until a 4th AP is heard. Although the AP’s are sending NDP messages to each other no matter what(I am going to verify this right now.), those messages are also used for other things like CleanAir and Rogue Detection according to the document that Jeff mentioned in his comment.

I just verified that NDP messages are still being sent every 60 seconds with just a single AP active on the WLC.

Awesome post and will be a great reference to customers we work with in Hospitals!

The fact that a ‘1’ is not a ‘1’ is definitely a challenge and can have a big effect on designs. Here is a reference ( http://blong1wifiblog.blogspot.com/2015/01/cisco-wireless-access-point-5ghz.html ) to output powers and the corresponding Cisco Power level for the 1131, 1242, 1142, 2602 and 3702 Cisco Access Points.

It was a hospital implementation that inspired this post. 🙂

Thanks for the link to the writeup you did. I will mention it when I update this post based on the comments received so far. TPC is definitely something that appears rather simple if you look at the settings within the WLC, but there is so much more to it. Even when I thought I understood it after testing, it turns out I really didn’t! Not sure I still do.

Great post, Matthew! On ESS and predictives for Cisco Voice, does it make sense to you to change the ESS defaults from 2 APs heard to min of 3 (plus dBm to -70, as you also suggest)? I am on conversation for tshoot of a poorly designed voice WLAN right now and if I have to go back out to do a predictive, I am just wondering if changing the defaults makes the best sense for a proper design. Thoughts?

Keep in mind that ESS is built with clients in mind. It isn’t necessarily concerned with AP to AP communication with respect to power levels. It does a great job of showing channel overlap, number of AP’s heard, etc. Without an understanding of how TPC works, you can layout AP’s to provide adequate coverage and capacity, but completely neglect how the AP’s will behave towards each other. By changing the defaults from 2 AP’s to 3 with a minimum signal level of -70dBm, you can ensure(as much as a predictive survey can) that your AP’s will see enough of each other to have the TPC algorithm run and let power levels adjust to something other than the maximum.

The “Network Issues” display in ESS will show areas in yellow that don’t meet this 3AP@-70dBm, or whatever value you set. You don’t need to try and get rid of all the yellow across the entire floor or area. You just need to get rid of it around the AP’s themselves. You will also have to ensure that the standard client coverage requirements(-67dBm for Cisco voice) are met, but with the amount of AP’s you will need to get TPC working, that shouldn’t be a problem. The alternative is to have all your AP’s running at max power since TPC didn’t have the right amount of AP’s at the right signal level to adjust power levels. While AP’s running at max power isn’t necessarily a bad thing, it will cause problems if you have an AP fail and none of the neighboring AP’s can increase power to offset the signal coverage gap from the failed AP. Additionally, with varying power levels across the UNII bands on 5GHz, max power could be anywhere from 25mW to 200mW. That could cause some big issues with voice deployments as you’ll run into the issue where the phone can hear the AP, but the AP can’t hear the phone.

My thoughts

I haven’t deployed a Cisco WLAN system (yet), but other vendors have the same or similar algorithm for that. But I haven’t used it once in my designs. Now I’m always open to rethink my designs, but relying on TPC (or similar) to cover holes if an AP fails or to reduce CCI just doesn’t seem quite right to me.

To cover holes upon an AP failure can be somewhat designed for with some proper cell overlap, however I would do that only in the 5GHz.

And CCI is not a factor of APs only, client devices are STAs too and they will equally effect other APs on the same channel. Plus lowering pwr for them completely obliterates your RSSI/SNR design. And lowering pwr also changes your MCS rates.

And just to compare, if a critical life-saving hospital component is low on battery and someone needs it immediately, those doctors won’t say: “Now, just try and hold on for a second while we charge this baby up. It really shouldn’t take long.” No, they’ll get a new one ASAP having it ready on standby. So the same must apply to APs if it’s a mission critical component.

So using something like TPC just doesn’t seem prudent to me. I’d rather use a fixed power value and design around that, but then again, I’m always open for new ideas.

I would be curious how you design around failure of an AP. Do your designs have enough cell overlap to where a failed AP would be covered by other AP’s nearby? Additionally, how do you deal with persistent interference and orchestrate cascading channel changes to compensate for that? This wouldn’t necessarily be an issue on 5GHz if you are using multiple UNII bands and 20MHz channels, but it would definitely be an issue on the 2.4GHz side.

I suppose it all depends on how responsive a company can be to failures in the network. TPC, or any other vendor implementation for that matter, can dynamically change based on the RF conditions. If everything is manually set, it requires manual intervention. I am not saying that there isn’t a use case for manually setting transmit power and channel assignments. I just think the majority of people supporting wireless networks out there would prefer to automate as much of the process as possible. Thanks for your viewpoint!

Comments are closed.

- December 2018

- January 2017

- October 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

Recent Comments

- Matthew Norwood on Aerohive’s Private Pre-Shared Key Technology

- Lee Badman on Aerohive’s Private Pre-Shared Key Technology

- Matthew Norwood on Does Aerohive Scale?

- Chris Carlton on Does Aerohive Scale?

- Marc on From Multi-Vendor To Single-Vendor

Unlimited Access

Exam 350-401 topic 1 question 407 discussion.

If the maximum power level assignment for global TPC 802.11a/n/ac is configured to 10 dBm. which power level effectively doubles the transmit power?

siteoforigin

Rafaelinho88, get it certification.

Unlock free, top-quality video courses on ExamTopics with a simple registration. Elevate your learning journey with our expertly curated content. Register now to access a diverse range of educational resources designed for your success. Start learning today with ExamTopics!

Log in to ExamTopics

Report comment.

- Skip to content

- Skip to search

- Skip to footer

Enhanced Classic LAN, Release Release 12.2.1

New and changed information, general parameters, spanning tree, manageability, configuration backup, flow monitor.

The following table provides an overview of the significant changes up to this current release. The table does not provide an exhaustive list of all changes or of the new features up to this release.

Creating an Enhanced Classic LAN Fabric

This document describes how to create a new Enhanced Classic LAN fabric using the Enhanced Classic LAN fabric template.

Note that this document gives information specifically for the fields that you will see in the Enhanced Classic LAN fabric template. See the Managing Legacy/Classic Networks in Cisco Nexus Dashboard Controller document for detailed procedures around managing legacy/classic networks in NDFC using the Enhanced Classic LAN fabric template.

Navigate to the LAN Fabrics page:

Manage > Fabrics

Click Actions > Create Fabric .

The Create Fabric window appears.

Enter a unique name for the fabric in the Fabric Name field, then click Choose Fabric .

A list of all available fabric templates are listed.

From the available list of fabric templates, choose the Enhanced Classic LAN template, then click Select .

Enter the necessary field values to create a fabric.

The tabs and their fields in the screen are explained in the following sections. The fabric level parameters are included in these tabs.

When you have completed the necessary configurations, click Save .

Click on the fabric to display a summary in the slide-in pane.

Click on the Launch icon to display the Fabric Overview.

The General Parameters tab is displayed by default. The fields in this tab are described in the following table.

What’s next: Complete the configurations in another tab if necessary, or click Save when you have completed the necessary configurations for this fabric.

The fields in the Spanning Tree tab are described in the following table. All of the fields are automatically populated based on Cisco-recommended best practice configurations, but you can update the fields if needed.

The fields in the VPC tab are described in the following table. All of the fields are automatically populated based on Cisco-recommended best practice configurations, but you can update the fields if needed.

The fields in the Protocols tab are described in the following table. Most of the fields are automatically populated based on Cisco-recommended best practice configurations, but you can update the fields if needed.

The fields in the Advanced tab are described in the following table. All of the fields are automatically populated based on Cisco-recommended best practice configurations, but you can update the fields if needed.

The fields in the Resources tab are described in the following table. Most of the fields are automatically populated based on Cisco-recommended best practice configurations, but you can update the fields if needed.

The fields in the Manageability tab are described in the following table. Most of the fields are automatically populated based on Cisco-recommended best practice configurations, but you can update the fields if needed.

The fields in the Bootstrap tab are described in the following table. Most of the fields are automatically populated based on Cisco-recommended best practice configurations, but you can update the fields if needed.

The fields in the Configuration Backup tab are described in the following table. Most of the fields are automatically populated based on Cisco-recommended best practice configurations, but you can update the fields if needed.

The fields in the Flow Monitor tab are described in the following table. Most of the fields are automatically populated based on Cisco-recommended best practice configurations, but you can update the fields if needed.

In the Netflow Exporter area, click Actions > Add to add one or more Netflow exporters. This exporter is the receiver of the netflow data. The fields on this screen are:

Exporter Name - Specifies the name of the exporter.

IP - Specifies the IP address of the exporter.

VRF - Specifies the VRF over which the exporter is routed.

Source Interface - Enter the source interface name.

UDP Port - Specifies the UDP port over which the netflow data is exported.

Click Save to configure the exporter. Click Cancel to discard. You can also choose an existing exporter and select Actions > Edit or Actions > Delete to perform relevant actions.

In the Netflow Record area, click Actions > Add to add one or more Netflow records. The fields on this screen are:

Record Name - Specifies the name of the record.

Record Template - Specifies the template for the record. Enter one of the record templates names. The following two record templates are available for use. You can create custom netflow record templates. Custom record templates saved in the template library are available for use here.

netflow_ipv4_record - to use the IPv4 record template.

netflow_l2_record - to use the Layer 2 record template.

Is Layer2 Record - Check this check box if the record is for Layer2 netflow.

Click Save to configure the report. Click Cancel to discard. You can also choose an existing record and select Actions > Edit or Actions > Delete to perform relevant actions.

In the Netflow Monitor area, click Actions > Add to add one or more Netflow monitors. The fields on this screen are:

Monitor Name - Specifies the name of the monitor.

Record Name - Specifies the name of the record for the monitor.

Exporter1 Name - Specifies the name of the exporter for the netflow monitor.

Exporter2 Name - (optional) Specifies the name of the secondary exporter for the netflow monitor.

The record name and exporters referred to in each netflow monitor must be defined in " Netflow Record " and " Netflow Exporter ".

In the Netflow Sampler area, click Actions > Add to add one or more Netflow samplers. These are optional fields and are applicable only when there are N7K aggregation switches in the fabric. The fields on this screen are:

Sampler Name - Specifies the name of the sampler.

Number of Samples

Number of Packets in Each Sampling

Click Save to configure the monitor. Click Cancel to discard. You can also choose an existing monitor and select Actions > Edit or Actions > Delete to perform relevant actions.

THE SPECIFICATIONS AND INFORMATION REGARDING THE PRODUCTS IN THIS MANUAL ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE. ALL STATEMENTS, INFORMATION, AND RECOMMENDATIONS IN THIS MANUAL ARE BELIEVED TO BE ACCURATE BUT ARE PRESENTED WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED. USERS MUST TAKE FULL RESPONSIBILITY FOR THEIR APPLICATION OF ANY PRODUCTS.

THE SOFTWARE LICENSE AND LIMITED WARRANTY FOR THE ACCOMPANYING PRODUCT ARE SET FORTH IN THE INFORMATION PACKET THAT SHIPPED WITH THE PRODUCT AND ARE INCORPORATED HEREIN BY THIS REFERENCE. IF YOU ARE UNABLE TO LOCATE THE SOFTWARE LICENSE OR LIMITED WARRANTY, CONTACT YOUR CISCO REPRESENTATIVE FOR A COPY.

The Cisco implementation of TCP header compression is an adaptation of a program developed by the University of California, Berkeley (UCB) as part of UCB’s public domain version of the UNIX operating system. All rights reserved. Copyright © 1981, Regents of the University of California.

NOTWITHSTANDING ANY OTHER WARRANTY HEREIN, ALL DOCUMENT FILES AND SOFTWARE OF THESE SUPPLIERS ARE PROVIDED “AS IS" WITH ALL FAULTS. CISCO AND THE ABOVE-NAMED SUPPLIERS DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, THOSE OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT OR ARISING FROM A COURSE OF DEALING, USAGE, OR TRADE PRACTICE.

IN NO EVENT SHALL CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY INDIRECT, SPECIAL, CONSEQUENTIAL, OR INCIDENTAL DAMAGES, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, LOST PROFITS OR LOSS OR DAMAGE TO DATA ARISING OUT OF THE USE OR INABILITY TO USE THIS MANUAL, EVEN IF CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS HAVE BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES.

Any Internet Protocol (IP) addresses and phone numbers used in this document are not intended to be actual addresses and phone numbers. Any examples, command display output, network topology diagrams, and other figures included in the document are shown for illustrative purposes only. Any use of actual IP addresses or phone numbers in illustrative content is unintentional and coincidental.

The documentation set for this product strives to use bias-free language. For the purposes of this documentation set, bias-free is defined as language that does not imply discrimination based on age, disability, gender, racial identity, ethnic identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and intersectionality. Exceptions may be present in the documentation due to language that is hardcoded in the user interfaces of the product software, language used based on RFP documentation, or language that is used by a referenced third-party product.

Cisco and the Cisco logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of Cisco and/or its affiliates in the U.S. and other countries. To view a list of Cisco trademarks, go to this URL: http://www.cisco.com/go/trademarks . Third-party trademarks mentioned are the property of their respective owners. The use of the word partner does not imply a partnership relationship between Cisco and any other company. (1110R)

© 2017-2024 Cisco Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

Bias-Free Language

The documentation set for this product strives to use bias-free language. For the purposes of this documentation set, bias-free is defined as language that does not imply discrimination based on age, disability, gender, racial identity, ethnic identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and intersectionality. Exceptions may be present in the documentation due to language that is hardcoded in the user interfaces of the product software, language used based on RFP documentation, or language that is used by a referenced third-party product. Learn more about how Cisco is using Inclusive Language.

- Open a Support Case

- (Requires a Cisco Service Contract )

eating disorder in adolescence essay

Eating disorders in adolescents essay.

Eating disorder as a severe health condition that can be manifested in many different ways may tackle a person of any age, gender, and socio-cultural background. However, adolescents, especially when it comes to female teenagers, are considered to be the most vulnerable in terms of developing this condition (Izydorczyk & Sitnik-Warchulska, 2018). According to the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP, 2018), 10 in 100 young women struggle with an eating disorder. Thus, the purpose of the present paper is to dwell on the specifics of external factors causing the disorder as well as the ways to deal with this issue.

To begin with, it is necessary to define which diseases are meant under the notion of an eating disorder. Generally, eating disorders encompass such conditions as anorexia nervosa, bulimia, binge eating, and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) (AACAP, 2018). Although these conditions have different manifestations in the context of eating patterns, all of them affect teenager’s nutrition patterns and average weight. According to the researchers, there exist common external stressors that lead to an eating disorder, such as:

- Socio-cultural appearance standards. For the most part, modern culture and mass media promote certain body images as a generally accepted ideal, which causes many teenage girls to doubt their appearance and follow the mass trends.

- Biological factors. Some teenagers might have a genetic predisposition for certain disorders if anyone in the family struggled with the disease at some point in the past.

- Emotional factors. Children, who are at risk of being affected by such mental disorders as anxiety and depression, are likely to disrupt their nutrition patterns.

- Peer pressure. Similar to socio-cultural standards, peer pressure dictates certain criteria for the teenagers’ body image, eventually impacting their perception of food and nutrition (Izydorczyk & Sitnik-Warchulska, 2018).

With such a variety of potential stressors, it is imperative for both medical professionals and caregivers to pay close attention to the teenager’s eating habits. Thus, in order to assess the issue, any medical screening should include weight and height measurements. In such a way, medical professionals are able to define any discrepancies in the measurements over time and bring this issue up with a patient. When working with adolescents, it is of paramount importance to establish a trusting relationship with a patient, as teenagers are extremely vulnerable at this age. After identifying any issue related to weight and body image, nurses and physicians need to ask the patient whether they have any problems with eating. In case they are not willing to talk on the matter, it is necessary to emphasize that their response will not be shared with caregivers unless they want it. It is also necessary to ask questions regarding the child’s relationship with peers carefully, as they may easily become an emotional trigger.

In order to avoid such complications as eating disorders, it is vital for caregivers to talk with their children on the topic of the aforementioned stressors. Firstly, they need to promote healthy eating patterns by explaining why it is important for one’s body instead of giving orders to the child. For additional support, they may ask a medical professional to justify this information. Secondly, the caregivers need to dedicate time to explain the inappropriateness of body standards promoted by the mass media and promote diversity and positive body image within the family. Lastly, caregivers are to secure a safe environment for the teenager’s fragile self-esteem and self-actualization in order for them to feel more confident among peers (Boberová & Husárová, 2021). These steps, although frequently undermined, contribute beneficially in terms of dealing with eating disorders external stressors among adolescents.

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry [AACAP]. (2018). Eating disorders in teens. Web.

Boberová, Z., & Husárová, D. (2021). What role does body image in relationship between level of health literacy and symptoms of eating disorders in adolescents?. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 18 (7), 3482.

Izydorczyk, B., & Sitnik-Warchulska, K. (2018). Socio-cultural appearance standards and risk factors for eating disorders in adolescents and women of various ages. Frontiers in psychology , 9 , 429.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, June 23). Eating Disorders in Adolescents. https://ivypanda.com/essays/eating-disorders-in-adolescents/

"Eating Disorders in Adolescents." IvyPanda , 23 June 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/eating-disorders-in-adolescents/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Eating Disorders in Adolescents'. 23 June.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Eating Disorders in Adolescents." June 23, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/eating-disorders-in-adolescents/.

1. IvyPanda . "Eating Disorders in Adolescents." June 23, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/eating-disorders-in-adolescents/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Eating Disorders in Adolescents." June 23, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/eating-disorders-in-adolescents/.

- External Stressors in Adolescents

- Eating Disorders in Adolescent Girls

- Influence of Modelling in Teenager’s Eating Disorders

- Socio-Cultural Approach of Humanity Examination

- Eating and Mood Disorders Among Adolescents

- Stressors in Nursing Workplace

- Environmental Stressors

- The Socialization of the Caregivers

- Organizational Stressors, Their Results and Types

- Eating Disorders in Male Adolescents as Health Topic

- Discussion Board Post: Distinction between the Public and Private

- Cyberbullying: Definition, Forms, Groups of Risk

- Human Trafficking and Healthcare Organizations

- The Politics of Abortion in Modern Day Jamaica

- Challenges of Prisoner Re-Entry Into Society

Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Eating Disorders — Eating Disorders in Adolescents

Eating Disorders in Adolescents

- Categories: Eating Disorders

About this sample

Words: 568 |

Published: Feb 12, 2024

Words: 568 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, types of eating or feeding disorders in adolescents, causes and risk factors of eating disorders in adolescents, treating eating disorders.

Fairburn, C.G. (2008). Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders . New York: Guilford Press.

Grilo, C.M., & Mitchell, J.E. (2012). Treatment of Eating Disorders . New York: Guilford Press.

- Herrin, M., & Larkin, M. (2013). Nutrition Counseling in the Treatment of Eating Disorders . California: Routledge.

Hornbacher, M. (2009). Wasted: A Memoir of Anorexia and Bulimia . New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Lock, J., & Grange, D.L. (2005). Help Your Teenager Beat an Eating Disorder . New York: Guilford Press.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

5 pages / 2332 words

5 pages / 2196 words

2 pages / 799 words

4 pages / 1677 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Eating Disorders

Jane Martin's play "Beauty" is a thought-provoking exploration of society's obsession with physical appearance and the detrimental impact of consumerism on individual self-esteem. In this essay, we will delve into the portrayal [...]

Psychological disorders are more commonly diagnosed in today’s society. Years ago, a psychological disorder was easily overlooked. In today’s society, it is easier to tell if someone has a psychological disorder because of all [...]

According to “Number of Adults with Eating Disorders in The U.S in 2008-2012, by Age Group (in 1,000) on Statista, there were eleven thousand people between the age of eighteen to twenty-five years old who were diagnosed with [...]

First of foremost, the subject at hand is still in constant debates; whether food addiction truly exist or not, for as we all know food is vital to our survival as a living organism. Also, we all have this tendency to get [...]

Eating disorders have become a prevalent issue in today's society, affecting individuals of all ages and backgrounds. From anorexia nervosa to bulimia to binge eating disorder, these conditions not only impact physical health [...]

The global rise in obesity has reached alarming levels, presenting a significant public health challenge. This essay delves into the multifaceted nature of obesity and examines a range of solutions to address this complex issue. [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

SCOFF indicates Sick, Control, One, Fat, Food.

a Data from KiGGS baseline, 2003-2006. 34

b Data from KiGGS wave 2, 2014-2017. 34

eTable 1. Electronic search strategy

eTable 2. Excluded studies and reasons for exclusion

eTable 3. Results of the quality assessment checklist for prevalence studies

eFigure. Doi plot and Luis Furuya-Kanamori index determining the publication bias of the studies analyzed for proportion of disordered eating

Data sharing statement

See More About

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Others Also Liked

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

López-Gil JF , García-Hermoso A , Smith L, et al. Global Proportion of Disordered Eating in Children and Adolescents : A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis . JAMA Pediatr. 2023;177(4):363–372. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.5848

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Global Proportion of Disordered Eating in Children and Adolescents : A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- 1 Health and Social Research Center, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, Cuenca, Spain

- 2 Department of Environmental Health, T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts

- 3 Navarrabiomed, Hospital Universitario de Navarra (HUN), Universidad Pública de Navarra (UPNA), IdiSNA, Pamplona, Navarra, Spain

- 4 Centre for Health, Performance and Wellbeing, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, United Kingdom

- 5 Division of Psychology and Mental Health, University of Manchester, Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, Manchester, United Kingdom

- 6 Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, Manchester, United Kingdom

- 7 Centre for Public Health, Queen’s University, Belfast, United Kingdom

- 8 Postgraduate Program in Public Health, Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina, Brazil

- 9 Escuela de Fisioterapia, Universidad de las Américas, Quito, Ecuador

- 10 Faculty of Nursing, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, Albacete, Spain

- 11 Faculty of Health Sciences, San Antonio Catholic University of Murcia, Murcia, Spain

Question What is the global proportion of disordered eating in children and adolescents?

Findings In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 32 studies including 63 181 participants from 16 countries, 22% reported that children and adolescents showed disordered eating. The proportion was further elevated among girls, older adolescents, and those with higher body mass index.

Meaning Identifying the magnitude of disordered eating and its distribution in at-risk populations is crucial for planning and executing actions aimed at preventing, detecting, and dealing with them.

Importance The 5-item Sick, Control, One, Fat, Food (SCOFF) questionnaire is the most widely used screening measure for eating disorders. However, no previous systematic review and meta-analysis determined the proportion of disordered eating among children and adolescents.

Objective To establish the proportion among children and adolescents of disordered eating as assessed with the SCOFF tool.

Data Sources Four databases were systematically searched (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library) with date limits from January 1999 to November 2022.

Study Selection Studies were required to meet the following criteria: (1) participants: studies of community samples of children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 years and (2) outcome: disordered eating assessed by the SCOFF questionnaire. The exclusion criteria included (1) studies conducted with young people who had a diagnosis of physical or mental disorders; (2) studies that were published before 1999 because the SCOFF questionnaire was designed in that year; (3) studies in which data were collected during COVID-19 because they could introduce selection bias; (4) studies based on data from the same surveys/studies to avoid duplication; and (5) systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses and qualitative and case studies.

Data Extraction and Synthesis A systematic review and meta-analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline.

Main Outcomes and Measures Proportion of disordered eating among children and adolescents assessed with the SCOFF tool.

Results Thirty-two studies, including 63 181 participants, from 16 countries were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. The overall proportion of children and adolescents with disordered eating was 22.36% (95% CI, 18.84%-26.09%; P < .001; n = 63 181) ( I 2 = 98.58%). Girls were significantly more likely to report disordered eating (30.03%; 95% CI, 25.61%-34.65%; n = 27 548) than boys (16.98%; 95% CI, 13.46%-20.81%; n = 26 170) ( P < .001). Disordered eating became more elevated with increasing age ( B , 0.03; 95% CI, 0-0.06; P = .049) and body mass index ( B , 0.03; 95% CI, 0.01-0.05; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the available evidence from 32 studies comprising large samples from 16 countries showed that 22% of children and adolescents showed disordered eating according to the SCOFF tool. Proportion of disordered eating was further elevated among girls, as well as with increasing age and body mass index. These high figures are concerning from a public health perspective and highlight the need to implement strategies for preventing eating disorders.

Eating disorders are psychiatric disorders characterized by abnormal eating or weight control behaviors, which can lead to serious health problems. 1 These disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, and eating disorder–not otherwise specified. 2 , 3 They are defined according to individual signs and symptoms and with degrees of severity detailed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) ( DSM-5 ), 2 as well as in the World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11) . 3 Similarly, they are recognized within the mental disorders included in the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study 2019 4 and are currently a public health concern in most mid- and high-income countries because their prevalence in young people has markedly increased over the past 50 years. 1 Furthermore, eating disorders are among the most life-threatening of all mental health conditions 5 and accounted for 17 361.5 years of life lost (between 1990 and 2019) and caused 318.3 deaths worldwide in 2019. 4

The etiology of eating disorders is very complex and, similar to other psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety, arises from the intersection of many risk factors. 6 Although the prevalence varies according to study populations and definitions used, 7 it is recognized that eating disorders are common in adolescents and even more common in young adults. 8 Based on the DSM-5 , the prevalence of eating disorders in children and adolescents (aged 11-19 years) has been stated to be between 1.2% (boys) and 5.7% (girls), with increasing incidence over recent decades. 7 Considering that mid to late adolescence is a peak period of eating disorders and their symptoms, knowing and understanding the proportion of disordered eating among youths is a crucial issue. 9

Because some children and adolescents with eating disorders may hide the core symptoms of the illness and delay seeking specialized care due to feelings of shame or stigmatization, 10 it is reasonable to consider that eating disorders are underdiagnosed and undertreated. 11 In addition to diagnosed eating disorders, parents, guardians, and health care professionals should be aware of symptoms of disordered eating, which include behaviors such as weight loss dieting, binge eating, self-induced vomiting, excessive exercise, and the use of laxatives or diuretics (although not to the level to warrant a clinical diagnosis of an eating disorder). 12 Although these symptoms predict outcomes related to eating disorders and obesity in adolescents 5 years later, 13 it is important to distinguish disordered eating from eating disorders. 14 The term disordered eating is often used to describe and identify some of the different eating behaviors that do not necessarily meet the diagnostic criteria for an eating disorder and therefore cannot be classified as eating disorders per se. 15 Notwithstanding, although its impact on health is often minimized, disordered eating should be closely evaluated because it can evolve into eating disorders. 12

The Sick, Control, One, Fat, Food (SCOFF) questionnaire, developed in 1999 by Morgan et al, 16 is the most widely used screening measure for eating disorders. 17 It consists of 5 questions with dichotomic answers options (ie, yes or no) 16 : (1) Do you make yourself sick because you feel uncomfortably full? (2) Do you worry you have lost control over how much you eat? (3) Have you recently lost more than 1 stone in a 3-month period? (4) Do you believe yourself to be fat when others say you are too thin? (5) Would you say that food dominates your life? A positive screen is provided when a participant answers yes to 2 or more questions, 16 which denotes a suspicion of an existing eating disorder (ie, disordered eating). 17 Previous systematic reviews have examined the SCOFF questionnaire as a screening tool in primary care setting. 17 , 18 For instance, a recent systematic review with meta-analysis including 25 validation studies found that the validity of the cutoff point of 2 or more on the SCOFF questionnaire was high across samples with a pooled sensitivity of 86.0% and specificity of 83.0%. Another recent systematic review for populations and settings relevant to primary care in the US found that a cutoff point of 2 or more on the SCOFF questionnaire had a pooled sensitivity of 84% and pooled specificity of 80% among adults. 18 Among young people, previous studies have found that the cutoff point of 2 or more on the SCOFF questionnaire provided a sensitivity ranging from 64.1% to 81.9% and a specificity ranging from 77.7% to 87.2%. 19 - 22

Despite the above, thus far, no previous systematic review and meta-analysis determined the proportion of disordered eating among children and adolescents. From an epidemiological perspective, identifying the magnitude of disordered eating and its distribution in at-risk populations is crucial for planning and executing actions aimed at preventing, detecting, and dealing with them. 23 Therefore, the aim of the present study was to establish the proportion among children and adolescents of disordered eating as assessed with the SCOFF tool, one of the most widely used methods to study disordered eating in this population. 8

This systematic review and meta-analysis was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) ( CRD42022350837 ) and conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses ( PRISMA ) reporting guideline. 24

Studies were required to meet the following criteria: (1) participants: studies of community samples of children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 years and (2) outcome: disordered eating assessed by the SCOFF questionnaire. Searching was not restricted to articles published in peer-reviewed journals of any particular language. For studies that included children/adolescents and adults, the articles were reviewed and, if reported, the child/adolescent samples were included.

The exclusion criteria included (1) studies conducted with young people who had a diagnosis of physical or mental disorders; (2) studies that were published before 1999 because the SCOFF questionnaire was designed in that year 16 ; (3) studies in which data were collected during COVID-19 because they could introduce selection bias; (4) studies based on data from the same surveys/studies to avoid duplication; and (5) systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses and qualitative and case studies.

Two researchers (J.F.L.-G. and D.V.-M.) systematically searched PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library with date limits from January 1999 to November 2022. Based on the participants, outcome, and study criteria, studies were identified using all possible combinations of the following groups of search terms: (1) child* OR adolescent* OR youth* OR teen* OR young* and (2) Sick, Control, One, Fat, Food OR SCOFF. The complete search strategy for each database is shown in eTable 1 in Supplement 1 . In addition, the list of references of the studies included in this review and in a previous systematic review 17 was thoroughly reviewed to ensure that no eligible studies were missed.

After identifying eligible studies, Mendeley (version for Windows 10; Elsevier) was used to remove duplicate studies. Two members of the research team (J.F.L.-G. and D.V.-M.) conducted the selection process independently and screened every title and abstract to identify potentially relevant articles to be reviewed in the full-text phase. A third researcher (A.G.-H.) participated to resolve any discrepancies.

The proportion of participants with disordered eating (ie, cutoff point ≥2 on the SCOFF questionnaire) was extracted by 1 researcher (D.V.-M.). Another researcher (J.F.L.-G.) checked the data for accuracy. In case of a discrepancy between these 2 researchers, a third researcher (A.G.-H.) reviewed the information.

Information on the authors, affiliations, date, and source of each study included in this review was hidden to avoid bias in the assessment of the methodological quality of the articles. Two researchers (D.V.-M. and J.F.L.-G.) independently assessed the risk of study bias of the included studies. This assessment was performed using a specific tool by Hoy et al 25 for prevalence studies. The tool consists of 10 items that address both the external and internal validity of prevalence studies. Each item can be classified as yes (low risk) or no (high risk), which equals 0 and 1 point, respectively. The overall risk of study bias is deemed to be at low risk of bias, moderate risk of bias, or high risk of bias if the points scored are 0 to 3, 4 to 6, or 7 to 9, respectively.

Proportion of disordered eating was computed based on the raw numerators (ie, participants who scored ≥2 on SCOFF questionnaire) and denominators (ie, total sample) found among the studies.

Using RStudio software version 2022.07.2 + 576 (R Group for Statistical Computing) with the meta package, 26 a meta-analysis of single proportions (ie, metaprop ) was pooled by applying a random-effects model that displayed the results as forest plots using the inverse variance method. The exact or Clopper-Pearson method was used to establish 95% CIs for proportion from the selected individual studies, 27 and a Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation was used to normalize the results before calculating the pooled proportion. 28 A continuity correction of 0.5 was used both to calculate individual study results with confidence limits and to conduct meta-analysis.

Heterogeneity between the included studies was determined by the I 2 statistic and its P value. Small study effects and publication bias were examined using the Doi plot and the Luis Furuya-Kanamori index. 29 No asymmetry, minor asymmetry, or major asymmetry were considered with values of less than −2, between −2 and −1, and more than −1, respectively. 29

Subgroup analyses were conducted by gender. Furthermore, random-effects meta-regression analyses using the method of moments were estimated to independently assess whether disordered eating differed by mean age or body mass index (BMI) (both as continuous variables).

A total of 628 records were identified through database searches ( Figure 1 ). After screening for duplicates, gray literature, and other reasons, 302 records remained. Finally, 97 records were obtained for full-text review. Of those studies, 67 were excluded for several reasons (eTable 2 in Supplement 1 ). Two studies were included via other methods (ie, citation searching). Finally, 32 studies, including 63 181 participants, were included in this systematic review, and all studies were included in the meta-analysis.

The main characteristics of the 32 included studies are summarized in the Table . Twenty-six of the studies were cross-sectional, 19 , 20 , 30 , 31 , 34 , 36 , 37 , 39 , 41 - 46 , 48 - 59 4 were longitudinal, 32 , 33 , 35 , 40 1 was a quasi-experimental study, 47 and 1 was a randomized clinical trial. 38 A total of 63 181 participants (51.8% girls) aged 7 to 18 years were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

According to gender, 22 studies reported the overall proportion of children and adolescents with disordered eating in both girls and boys, and 2 studies included only 1 gender (ie, only girls 44 , 55 ). The remaining 8 studies did not report proportion segmented by gender. In terms of geographical regions, 16 different countries were identified, including 21 studies in Europe, 19 , 20 , 30 , 34 - 36 , 40 - 43 , 45 , 46 , 48 - 53 , 56 , 57 , 59 5 in Asia, 33 , 37 , 47 , 55 , 58 4 in North America, 31 , 32 , 44 , 54 1 in South America, 38 and 1 in Africa. 39 All the studies were conducted with participants from only 1 country.

All studies were deemed to be at low risk of bias, presenting scores ranging between 0 and 2 points (with the exception of the study by Hicks et al, 44 which presented 3 points). The main sources of bias were associated with the representativeness of the analyzed sample. 19 , 20 , 30 , 31 , 35 - 39 , 41 , 44 , 46 , 47 , 50 , 52 , 54 , 55 A summary of the risk of bias scoring is shown in eTable 3 in Supplement 1 .

Figure 2 shows that the overall proportion of children and adolescents with disordered eating was 22.36% (95% CI, 18.84%-26.09%; P < .001; n = 63 181) ( I 2 = 98.58%). The Luis Furuya-Kanamori index for the Doi plot showed no asymmetry, indicating no risk of publication bias (Luis Furuya-Kanamori index = −0.58) (eFigure in Supplement 1 ).

Figure 3 depicts the subgroup analysis according to gender. Girls were significantly more likely to report disordered eating (30.03%; 95% CI, 25.61%-34.65%; n = 27 548) than boys (16.98%; 95% CI, 13.46%-20.81%; n = 26 170) ( P < .001).

The random-effects meta-regression models between proportion of disordered eating and mean age or BMI are shown in Figure 4 . Disordered eating became more elevated with increasing age ( B , 0.03; 95% CI, 0-0.06; P = .049) ( Figure 4 A) and BMI ( B , 0.03; 95% CI, 0.01-0.05; P < .001) ( Figure 4 B).

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis that has comprehensively examined the overall proportion of children and adolescents with disordered eating in terms of gender, mean age, and BMI. The main findings of this study are as follows: (1) a total of 14 856 of 63 181 children and adolescents (22.36%) from 16 countries showed disordered eating; (2) the proportion of children and adolescents with disordered eating was significantly higher in girls than in boys; and (3) the proportion of disordered eating among children and adolescents was positively associated with mean age and BMI. These findings can inform intervention priorities for disordered eating as a global health initiative to prevent possible health problems among young people, 60 particularly in girls and young people with higher BMI.

Our findings indicate that more than 1 in 5 children and adolescents presented with disordered eating. It is noteworthy that disordered eating and eating disorders are not similar because not all children and adolescents who reported disordered eating behaviors will necessarily be diagnosed with an eating disorder. 15 However, disordered eating in childhood/adolescence may predict outcomes associated with eating disorders in early adulthood. 13 For this reason, this high proportion found is worrisome and call for urgent action to try to address this situation. In 2019, 14 million people experienced eating disorders including almost 3 million children and adolescents. 61 The behaviors related to eating disorders may lead to greater risk or damage to health, significant distress, or significant impairment of functioning. 60 Indeed, eating disorders are among the most life-threatening psychiatric problems, and people with these conditions die 10 to 20 years younger than the general population. 5

Our findings also indicated that the proportion of children and adolescents with disordered eating was higher in girls than in boys. Although sex differences in disordered eating seem to be relatively minor in adolescence, 62 it is well known that these disorders are more prevalent among girls. 63 Conventionally, studies have focused principally on the female sex, but currently this is not considered as a female-specific matter. The reasons for sex disagreement in the prevalence are not well known. 62 It has been pointed out that disordered eating is frequently unobserved among boys. 64 Boys are presumed to underreport the problem because of the societal perception that these disorders mostly affect girls 65 and because disordered eating has usually been thought by the general population to be exclusive to girls and women. 64 Additionally, it has been noted that the current diagnostic criteria of eating disorder 2 fail to detect disordered eating behaviors more commonly observed in boys than in girls, such as intensely engaging in muscle mass and weight gain with the goal of improving body image satisfaction. 64

On the other hand, the proportion of young people with disordered eating increased with increasing age. This finding is in line with the scientific literature. 66 - 68 The age at onset of eating disorders has classically been described in adolescence. 68 Adolescence represents a critical period for the onset of eating disorders. 66 Similarly, Swanson et al 67 found that the median age at onset of some eating disorders (eg, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder) ranged from 12.3 to 12.6 years in a US nationally representative sample including 10 123 adolescents. As the analyzed sample in the present systematic review and meta-analysis ranged from age 7 to 18 years and only 3 studies included only children (ie, aged 7-10 years), it seems to corroborate these ages at onset.

Importantly, we found that the proportion of children and adolescents with disordered eating became more evaluated with increasing BMI. In this sense, the proportion of disordered eating is higher in young people with excess weight than in their counterparts with normal weight. 37 , 69 , 70 Young people who have excess weight may follow disordered eating behaviors while attempting to lose body weight. 71 Therefore, it has been described that young people with excess weight is the population that appears to experience symptoms of disordered eating most frequently (eg, unsupervised weight loss dieting may lead to eating disorder risk 72 ). Although most adolescents who develop an eating disorder do not report prior excess weight problems, some adolescents could misinterpret what eating healthy consists of and engage in unhealthy behaviors (eg, skipping meals to generate a caloric deficit), which could then lead to development of an eating disorder. 73

The WHO’s Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2030 recognizes the essential role of mental health in achieving health for all people, establishing some objectives/priorities. 60 For instance, among others, this plan tries to strengthen information systems, evidence, and research for mental health. In this sense, our systematic review and meta-analysis contributes to this aim by providing epidemiological evidence on the current situation of disordered eating that, if undetected and untreated, can lead to eating disorders with their harmful consequences for the individual, the family, and society. Similarly, the high proportion of disordered eating found in this systematic review and meta-analysis reinforce the importance of screening eating disorders in primary care setting. This is in line with the recommendations by the American Academy of Pediatrics 74 and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 75 which advise screening young people through longitudinal height and weight monitoring and looking for symptoms of disordered eating. In this sense, the SCOFF questionnaire is simple, memorable, and easy for applying and scoring, 16 which may be considered the first approach to identify the need for a more detailed and specialized evaluation. 20 However, positive results should be followed by further questioning, prior to an automatic referral to mental health professionals. 76

The present study has certain limitations that must be acknowledged. First, only studies that analyzed disordered eating using the SCOFF questionnaire were included. This decision is justified by the intention of homogenizing the proportion of global proportion of children and adolescents with disordered eating. In this sense, the SCOFF questionnaire is the most widely used screening tool for eating disorders, has been adapted and validated for its use in several languages, seems to be highly effective as a screening tool, and has been extensively used to raise the suspicion level of an eating disorder. Second, because of the cross-sectional nature of most of the included studies, a causal relationship cannot be established. Third, due to the inclusion of binge eating disorder and other specified eating disorders in the DSM-5 , there is not enough evidence to support the use of SCOFF in primary care and community-based settings for screening all the range of eating disorders. However, a meta-analysis by Kutz et al 17 concluded that the SCOFF is a useful and simple screening tool for the most prevalent eating disorders (ie, bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa). Fourth, we included studies based on self-report questionnaires to assess disordered eating, and consequently, both social desirability and recall bias could influence the findings.

The available evidence from 32 studies comprising large samples from 16 countries showed that approximately 22% of children and adolescents showed disordered eating according to the SCOFF tool. The proportion of disordered eating was further elevated among girls as well as with increasing age and BMI. This high proportion is worrisome from a public health perspective and highlights the need to implement strategies for preventing eating disorders. 60

Accepted for Publication: November 30, 2022.

Published Online: February 20, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.5848