Here’s how you know

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- National Institutes of Health

NCCIH Clinical Digest

for health professionals

Massage Therapy for Health : What the Science Says

Clinical Guidelines, Scientific Literature, Info for Patients: Massage Therapy for Health

.header_greentext{color:green!important;font-size:24px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_bluetext{color:blue!important;font-size:18px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_redtext{color:red!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_darkred{color:#803d2f!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_purpletext{color:purple!important;font-size:31px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_yellowtext{color:yellow!important;font-size:20px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_blacktext{color:black!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_whitetext{color:white!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_darkred{color:#803d2f!important;}.Green_Header{color:green!important;font-size:24px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Blue_Header{color:blue!important;font-size:18px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Red_Header{color:red!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Purple_Header{color:purple!important;font-size:31px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Yellow_Header{color:yellow!important;font-size:20px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Black_Header{color:black!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.White_Header{color:white!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;} Low-Back Pain

Several reviews of research have found weak evidence that massage may be helpful for low-back pain. Clinical guidelines issued by the American College of Physicians in 2017 included massage as an option for treating acute/subacute low-back pain but did not include massage therapy among the options for treating chronic low-back pain.

What Does the Research Show?

- The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, in a 2016 evaluation of nondrug therapies for low-back pain, examined 20 studies that compared massage to usual care or other interventions and found that there was evidence that massage was helpful for chronic low-back pain but that the strength of evidence was low. The agency also looked at 6 studies that compared different types of massage but found that the evidence was insufficient to show whether any types were more effective than others.

- A 2015 Cochrane review found evidence that massage may provide short-term relief from low-back pain, but the evidence is not of high quality. The long-term effects of massage for low-back pain have not been established.

- Clinical practice guidelines issued by the American College of Physicians in 2017 included massage therapy as an option for treating acute/subacute low-back pain but did not include massage therapy among the options for treating chronic low-back pain.

.header_greentext{color:green!important;font-size:24px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_bluetext{color:blue!important;font-size:18px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_redtext{color:red!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_darkred{color:#803d2f!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_purpletext{color:purple!important;font-size:31px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_yellowtext{color:yellow!important;font-size:20px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_blacktext{color:black!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_whitetext{color:white!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_darkred{color:#803d2f!important;}.Green_Header{color:green!important;font-size:24px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Blue_Header{color:blue!important;font-size:18px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Red_Header{color:red!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Purple_Header{color:purple!important;font-size:31px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Yellow_Header{color:yellow!important;font-size:20px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Black_Header{color:black!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.White_Header{color:white!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;} Neck and Shoulder Pain

Massage therapy may provide short-term benefits for neck or shoulder pain.

- A 2016 review of four randomized controlled trials found that massage therapy may provide short-term benefits from neck pain. However, a 2012 Cochrane review of 15 trials on massage therapy for neck pain concluded that no recommendations for practice can be made at this time because the effectiveness of massage for neck pain remains uncertain.

- A 2013 review of 12 studies of massage for neck pain (757 total participants) found that massage therapy was more helpful for both neck and shoulder pain than inactive therapies but was not more effective than other active therapies. For shoulder pain, massage therapy had short-term benefits only.

- A 2014 randomized controlled trial involving 228 participants with chronic nonspecific neck pain found that 60-minute massages given multiple times per week was more effective than fewer or shorter sessions. The participants were randomized to 5 groups receiving various doses of massage (a 4-week course consisting of 30-minute visits 2 or 3 times weekly or 60-minute visits 1, 2, or 3 times weekly) or to a single control group (a 4-week period on a wait list).

.header_greentext{color:green!important;font-size:24px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_bluetext{color:blue!important;font-size:18px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_redtext{color:red!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_darkred{color:#803d2f!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_purpletext{color:purple!important;font-size:31px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_yellowtext{color:yellow!important;font-size:20px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_blacktext{color:black!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_whitetext{color:white!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_darkred{color:#803d2f!important;}.Green_Header{color:green!important;font-size:24px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Blue_Header{color:blue!important;font-size:18px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Red_Header{color:red!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Purple_Header{color:purple!important;font-size:31px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Yellow_Header{color:yellow!important;font-size:20px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Black_Header{color:black!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.White_Header{color:white!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;} Osteoarthritis

Only a few studies have examined massage therapy for osteoarthritis, but results of some of these studies suggest that massage may have short-term benefits in relieving knee pain.

- A 2017 systematic review of seven randomized controlled trials involving 352 participants with arthritis found low- to moderate-quality evidence that massage therapy is superior to nonactive therapies in reducing pain and improving functional outcomes. A 2013 review of two randomized controlled trials found positive short-term (less than 6 months) effects in the form of reduced pain and improved self-reported physical functioning. Results of a 2006 randomized controlled trial of 68 adults with OA of the knee who received standard Swedish massage over 8 weeks demonstrated statistically significant improvements in pain and physical function.

.header_greentext{color:green!important;font-size:24px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_bluetext{color:blue!important;font-size:18px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_redtext{color:red!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_darkred{color:#803d2f!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_purpletext{color:purple!important;font-size:31px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_yellowtext{color:yellow!important;font-size:20px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_blacktext{color:black!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_whitetext{color:white!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_darkred{color:#803d2f!important;}.Green_Header{color:green!important;font-size:24px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Blue_Header{color:blue!important;font-size:18px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Red_Header{color:red!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Purple_Header{color:purple!important;font-size:31px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Yellow_Header{color:yellow!important;font-size:20px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Black_Header{color:black!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.White_Header{color:white!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;} Headache

Only a small number of studies have looked at massage for headache, and results have not been consistent.

- Limited evidence from two small studies suggests massage therapy is possibly helpful for migraines, but clear conclusions cannot be drawn. A 2011 systematic review of these two studies concluded that massage therapy might be equally effective as propranolol and topiramate in the prophylactic management of migraine.

- A 2016 randomized controlled trial with 64 participants evaluated 2 types of massage (lymphatic drainage and traditional massage), once a week for 8 weeks, in patients with migraine. The frequency of migraines decreased in both groups, compared with people on a waiting list.

- In a 2015 randomized controlled trial , 56 people with tension headaches were assigned to receive massage at myofascial trigger points or an inactive treatment (detuned ultrasound) twice a week for 6 weeks or to be on a waiting list. People who received either massage or the inactive treatment had a decrease in the frequency of headaches, but there was no difference between the two groups.

.header_greentext{color:green!important;font-size:24px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_bluetext{color:blue!important;font-size:18px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_redtext{color:red!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_darkred{color:#803d2f!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_purpletext{color:purple!important;font-size:31px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_yellowtext{color:yellow!important;font-size:20px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_blacktext{color:black!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_whitetext{color:white!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_darkred{color:#803d2f!important;}.Green_Header{color:green!important;font-size:24px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Blue_Header{color:blue!important;font-size:18px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Red_Header{color:red!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Purple_Header{color:purple!important;font-size:31px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Yellow_Header{color:yellow!important;font-size:20px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Black_Header{color:black!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.White_Header{color:white!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;} Cancer Symptoms and Treatment Side Effects

With appropriate precautions, massage therapy can be part of supportive care for cancer patients who would like to try it; however, the evidence that it can relieve pain and anxiety is not strong. 2014 clinical practice guidelines for the care of breast cancer patients include massage as one of several approaches that may be helpful for stress reduction, anxiety, depression, fatigue, and quality of life.

- Clinical practice guidelines issued in 2009 by the Society for Integrative Oncology recommends considering massage therapy delivered by an oncology-trained massage therapist as part of a multimodality treatment approach in patients experiencing anxiety or pain.

- In 2017 the Society for Integrative Oncology issued guidelines on the evidence-based use of integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment, recommending the use of massage therapy to improve mood disturbance in breast cancer survivors after active treatment (grade B). This recommendation is based on results from six trials.

- In clinical practice guidelines issued by the American College of Chest Physicians in 2013, massage therapy is suggested as part of a multi-modality cancer supportive care program for lung cancer patients whose anxiety or pain is not adequately controlled by usual care.

- A 2016 Cochrane review of 19 small studies involving 1,274 participants found some studies suggesting that massage with or without aromatherapy may help relieve pain and anxiety in people with cancer; however, the quality of the evidence was very low and results were not consistent.

- Another 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis of 16 studies concluded that based on the available evidence, weak recommendations are suggested for massage therapy, compared to an active comparator, for the treatment of pain, fatigue, and anxiety.

.header_greentext{color:green!important;font-size:24px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_bluetext{color:blue!important;font-size:18px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_redtext{color:red!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_darkred{color:#803d2f!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_purpletext{color:purple!important;font-size:31px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_yellowtext{color:yellow!important;font-size:20px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_blacktext{color:black!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_whitetext{color:white!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_darkred{color:#803d2f!important;}.Green_Header{color:green!important;font-size:24px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Blue_Header{color:blue!important;font-size:18px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Red_Header{color:red!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Purple_Header{color:purple!important;font-size:31px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Yellow_Header{color:yellow!important;font-size:20px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Black_Header{color:black!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.White_Header{color:white!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;} Fibromyalgia

Results of research suggest that massage therapy may be helpful for some fibromyalgia symptoms.

- A 2014 systematic review and meta-analysis of 9 studies (404 total participants) concluded that massage therapy, if continued for at least 5 weeks, improved pain, anxiety, and depression in people with fibromyalgia but did not have an effect on sleep disturbance.

- A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 studies (478 total participants) compared the effects of different kinds of massage therapy and found that most styles of massage had beneficial effects on the quality of life in fibromyalgia. Swedish massage may be an exception; 2 studies of this type of massage (56 total participants) did not show benefits.

.header_greentext{color:green!important;font-size:24px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_bluetext{color:blue!important;font-size:18px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_redtext{color:red!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_darkred{color:#803d2f!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_purpletext{color:purple!important;font-size:31px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_yellowtext{color:yellow!important;font-size:20px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_blacktext{color:black!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_whitetext{color:white!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_darkred{color:#803d2f!important;}.Green_Header{color:green!important;font-size:24px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Blue_Header{color:blue!important;font-size:18px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Red_Header{color:red!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Purple_Header{color:purple!important;font-size:31px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Yellow_Header{color:yellow!important;font-size:20px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Black_Header{color:black!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.White_Header{color:white!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;} HIV/AIDS

There is some evidence that massage therapy may have benefits for anxiety, depression, and quality of life in people with HIV/AIDS, but the amount of research and number of people studied are small.

- A 2010 review of four studies involving a total of 178 participants concluded that massage therapy may help improve the quality of life for people with HIV or AIDS. A 2013 randomized controlled trial of 54 people suggested that massage may be helpful for depression in people with HIV; and a 2017 study of 29 people with HIV found that massage may be helpful for anxiety.

.header_greentext{color:green!important;font-size:24px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_bluetext{color:blue!important;font-size:18px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_redtext{color:red!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_darkred{color:#803d2f!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_purpletext{color:purple!important;font-size:31px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_yellowtext{color:yellow!important;font-size:20px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_blacktext{color:black!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_whitetext{color:white!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_darkred{color:#803d2f!important;}.Green_Header{color:green!important;font-size:24px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Blue_Header{color:blue!important;font-size:18px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Red_Header{color:red!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Purple_Header{color:purple!important;font-size:31px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Yellow_Header{color:yellow!important;font-size:20px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Black_Header{color:black!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.White_Header{color:white!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;} Infant Care

There is some evidence that premature infants who are massaged may have improved weight gain. No benefits of massage for healthy full-term infants have been clearly demonstrated.

- In a 2017 review of 34 randomized controlled trials of massage therapy for premature infants, 20 of the studies (1,250 total infants) evaluated the effect of massage on weight gain, with most showing an improvement. The mechanism by which massage therapy might increase weight gain is not well understood. Some studies suggested other possible benefits of massage but because the amount of evidence is small, no conclusions can be reached about effects other than weight gain.

- A 2013 Cochrane review of 34 studies of healthy full-term infants didn’t find clear evidence of beneficial effects of massage in these low-risk infants.

The risk of harmful effects from massage therapy appears to be low. However, there have been rare reports of serious side effects, such as blood clot, nerve injury, or bone fracture. Some of the reported cases have involved vigorous types of massage, such as deep tissue massage, or patients who might be at increased risk of injury.

.header_greentext{color:green!important;font-size:24px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_bluetext{color:blue!important;font-size:18px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_redtext{color:red!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_darkred{color:#803d2f!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_purpletext{color:purple!important;font-size:31px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_yellowtext{color:yellow!important;font-size:20px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_blacktext{color:black!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_whitetext{color:white!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.header_darkred{color:#803d2f!important;}.Green_Header{color:green!important;font-size:24px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Blue_Header{color:blue!important;font-size:18px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Red_Header{color:red!important;font-size:28px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Purple_Header{color:purple!important;font-size:31px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Yellow_Header{color:yellow!important;font-size:20px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.Black_Header{color:black!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;}.White_Header{color:white!important;font-size:22px!important;font-weight:500!important;} References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Noninvasive Treatments for Low Back Pain. AHRQ Publication No. 16-EHC004-EF. February 2016.

- Bennett C, Underdown A, Barlow J. Massage for promoting mental and physical health in typically developing infants under the age of six months . Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . 2013;(4):CD005038. Accessed at https://www.cochranelibrary.com on January 21, 2017.

- Boyd C, Crawford C, Paat CF, et al. The impact of message therapy on function in pain populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials: Part II, cancer pain populations . Pain Med . 2016;17(8):1553-1568.

- Chaibi A, Tuchin PJ, Russell MB. Manual therapies for migraine: a systematic review . J Headache Pain . 2011;12(2):127-133.

- Deng GE, Rausch SM, Jones LW, et al. Complementary therapies and integrative medicine in lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer , 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest . 2013;143(5 Suppl):e420S-e436S.

- Furlan AD, Giraldo M, Baskwill A, et al. Massage for low-back pain . Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . 2015;(9):CD001929. Accessed at www.cochranelibrary.com on January 26, 2017.

- Greenlee H, Balneaves LG, Carlson LE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines on the use of integrative therapies as supportive care in patients treated for breast cancer . Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs . 2014;2014(50):346-358.

- Happe S, Peikert A, Siegert R, et al. The efficacy of lymphatic drainage and traditional massage in the prophylaxis of migraine: a randomized, controlled parallel group study. Neurological Sciences . 2016;37(10):1627-1632,

- Hillier SL, Louw Q, Morris L, et al. Massage therapy for people with HIV/AIDS . Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . 2010;(1):CD007502. Accessed at www.cochranelibrary.com on August 18, 2017.

- Kong LJ, Zhan HS, Cheng YW, et al. Massage therapy for neck and shoulder pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2013;2013;613279.

- Li Y-h, Wang F-y, Feng C-q et al. Massage therapy for fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials . PLoS One . 2014;9(2):e89304.

- Moraska AF, Stenerson L, Butryn N, et al. Myofascial trigger point-focused head and neck massage for recurrent tension-type headache: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial . Clinical Journal of Pain . 2015;31(2):159-168.

- Nahin RL, Boineau R, Khalsa PS, Stussman BJ, Weber WJ. Evidence-based evaluation of complementary health approaches for pain management in the United States . Mayo Clinic Proceedings . September 2016;91(9):1292-1306.

- Nelson NL, Churilla JR. Massage therapy for pain and function in patients with arthritis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials . Am J Phys Med Rehabil . 2017;96(9):665-672.

- Niemi A-K. Review of randomized controlled trials of massage in preterm infants . Children . 2017;4(4):pii:E21.

- Patel KC, Gross A, Graham N, Goldsmith CH, Ezzo J, Morien A, Peloso PMJ. Massage for mechanical neck disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;9:CD004871.

- Perlman AI, Ali A, Njike VY, et al. Massage therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized dose-finding trial . PLoS One . 2012;7(2):e30248.

- Poland RE, Gertsik L, Favreau JT, et al. Open-label, randomized, parallel-group controlled clinical trial of massage for treatment of depression in HIV-infected subjects . Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine . 2013;19(4):334-340.

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM et al. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians . Annals of Internal Medicine . 2017;166(7):514-530.

- Shengelia R, Parker SJ, Ballin M, et al. Complementary therapies for osteoarthritis: are they effective? Pain Manag Nurs . 2013;14(4):e274-e288.

- Sherman KJ, Cook AJ, Wellman RD, et al. Five-week outcomes from a dosing trial of therapeutic massage for chronic neck pain . Ann Fam Med . 2014;12(2):112-120.

- Shin ES, Seo KH, Lee SH, et al. Massage with or without aromatherapy for symptom relief in people with cancer . Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . 2016;(6):CD009873. Accessed at www.cochranelibrary.com on January 26, 2017.

- Yuan SLK, Matsutani LA, Marques AP. Effectiveness of different styles of massage therapy in fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Manual Therapy . 2015;20(2):257-264.

NCCIH Clinical Digest is a service of the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, NIH, DHHS. NCCIH Clinical Digest, a monthly e-newsletter, offers evidence-based information on complementary health approaches, including scientific literature searches, summaries of NCCIH-funded research, fact sheets for patients, and more.

The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health is dedicated to exploring complementary health products and practices in the context of rigorous science, training complementary health researchers, and disseminating authoritative information to the public and professionals. For additional information, call NCCIH’s Clearinghouse toll-free at 1-888-644-6226, or visit the NCCIH website at nccih.nih.gov . NCCIH is 1 of 27 institutes and centers at the National Institutes of Health, the Federal focal point for medical research in the United States.

Content is in the public domain and may be reprinted, except if marked as copyrighted (©). Please credit the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health as the source. All copyrighted material is the property of its respective owners and may not be reprinted without their permission.

Subscriptions

NCCIH Clinical Digest is a monthly e-newsletter that offers evidence-based information on complementary and integrative health practices.

Clinical Digest Archive

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 08 April 2024

A systematic review and multivariate meta-analysis of the physical and mental health benefits of touch interventions

- Julian Packheiser ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9805-6755 2 na1 nAff1 ,

- Helena Hartmann 2 , 3 , 4 na1 ,

- Kelly Fredriksen 2 ,

- Valeria Gazzola ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0324-0619 2 ,

- Christian Keysers ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2845-5467 2 &

- Frédéric Michon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1289-2133 2

Nature Human Behaviour ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

- Paediatric research

- Randomized controlled trials

Receiving touch is of critical importance, as many studies have shown that touch promotes mental and physical well-being. We conducted a pre-registered (PROSPERO: CRD42022304281) systematic review and multilevel meta-analysis encompassing 137 studies in the meta-analysis and 75 additional studies in the systematic review ( n = 12,966 individuals, search via Google Scholar, PubMed and Web of Science until 1 October 2022) to identify critical factors moderating touch intervention efficacy. Included studies always featured a touch versus no touch control intervention with diverse health outcomes as dependent variables. Risk of bias was assessed via small study, randomization, sequencing, performance and attrition bias. Touch interventions were especially effective in regulating cortisol levels (Hedges’ g = 0.78, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.24 to 1.31) and increasing weight (0.65, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.94) in newborns as well as in reducing pain (0.69, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.89), feelings of depression (0.59, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.78) and state (0.64, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.84) or trait anxiety (0.59, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.77) for adults. Comparing touch interventions involving objects or robots resulted in similar physical (0.56, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.88 versus 0.51, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.64) but lower mental health benefits (0.34, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.49 versus 0.58, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.73). Adult clinical cohorts profited more strongly in mental health domains compared with healthy individuals (0.63, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.80 versus 0.37, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.55). We found no difference in health benefits in adults when comparing touch applied by a familiar person or a health care professional (0.51, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.73 versus 0.50, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.61), but parental touch was more beneficial in newborns (0.69, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.88 versus 0.39, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.61). Small but significant small study bias and the impossibility to blind experimental conditions need to be considered. Leveraging factors that influence touch intervention efficacy will help maximize the benefits of future interventions and focus research in this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Touching the social robot PARO reduces pain perception and salivary oxytocin levels

Nirit Geva, Florina Uzefovsky & Shelly Levy-Tzedek

The impact of mindfulness apps on psychological processes of change: a systematic review

Natalia Macrynikola, Zareen Mir, … John Torous

The why, who and how of social touch

Juulia T. Suvilehto, Asta Cekaite & India Morrison

The sense of touch has immense importance for many aspects of our life. It is the first of all the senses to develop in newborns 1 and the most direct experience of contact with our physical and social environment 2 . Complementing our own touch experience, we also regularly receive touch from others around us, for example, through consensual hugs, kisses or massages 3 .

The recent coronavirus pandemic has raised awareness regarding the need to better understand the effects that touch—and its reduction during social distancing—can have on our mental and physical well-being. The most common touch interventions, for example, massage for adults or kangaroo care for newborns, have been shown to have a wide range of both mental and physical health benefits, from facilitating growth and development to buffering against anxiety and stress, over the lifespan of humans and animals alike 4 . Despite the substantial weight this literature gives to support the benefits of touch, it is also characterized by a large variability in, for example, studied cohorts (adults, children, newborns and animals), type and duration of applied touch (for example, one-time hug versus repeated 60-min massages), measured health outcomes (ranging from physical health outcomes such as sleep and blood pressure to mental health outcomes such as depression or mood) and who actually applies the touch (for example, partner versus stranger).

A meaningful tool to make sense of this vast amount of research is through meta-analysis. While previous meta-analyses on this topic exist, they were limited in scope, focusing only on particular types of touch, cohorts or specific health outcomes (for example, refs. 5 , 6 ). Furthermore, despite best efforts, meaningful variables that moderate the efficacy of touch interventions could not yet be identified. However, understanding these variables is critical to tailor touch interventions and guide future research to navigate this diverse field with the ultimate aim of promoting well-being in the population.

In this Article, we describe a pre-registered, large-scale systematic review and multilevel, multivariate meta-analysis to address this need with quantitative evidence for (1) the effect of touch interventions on physical and mental health and (2) which moderators influence the efficacy of the intervention. In particular, we ask whether and how strongly health outcomes depend on the dynamics of the touching dyad (for example, humans or robots/objects, familiarity and touch directionality), demographics (for example, clinical status, age or sex), delivery means (for example, type of touch intervention or touched body part) and procedure (for example, duration or number of sessions). We did so separately for newborns and for children and adults, as the health outcomes in newborns differed substantially from those in the other age groups. Despite the focus of the analysis being on humans, it is widely known that many animal species benefit from touch interactions and that engaging in touch promotes their well-being as well 7 . Since animal models are essential for the investigation of the mechanisms underlying biological processes and for the development of therapeutic approaches, we accordingly included health benefits of touch interventions in non-human animals as part of our systematic review. However, this search yielded only a small number of studies, suggesting a lack of research in this domain, and as such, was insufficient to be included in the meta-analysis. We evaluate the identified animal studies and their findings in the discussion.

Touch interventions have a medium-sized effect

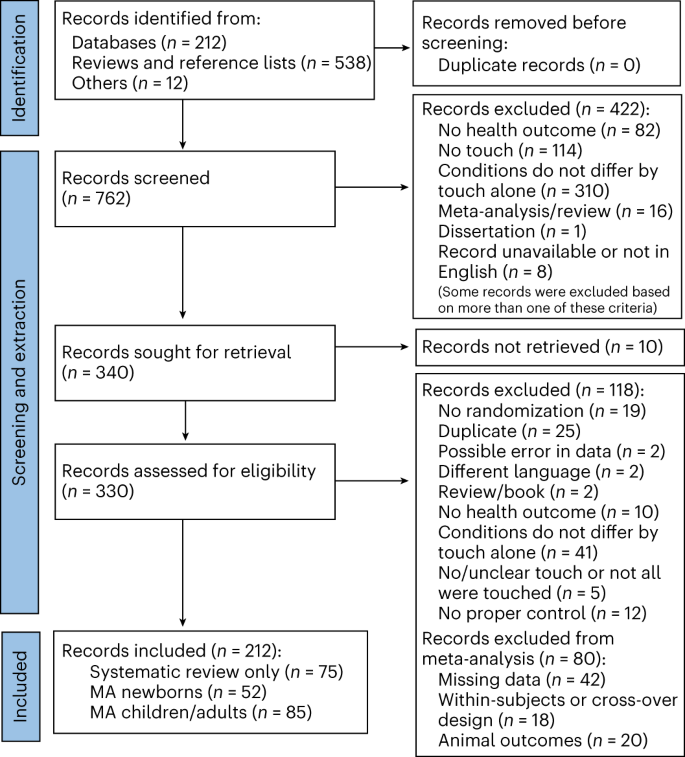

The pre-registration can be found at ref. 8 . The flowchart for data collection and extraction is depicted in Fig. 1 .

Animal outcomes refer to outcomes measured in non-human species that were solely considered as part of a systematic review. Included languages were French, Dutch, German and English, but our search did not identify any articles in French, Dutch or German. MA, meta-analysis.

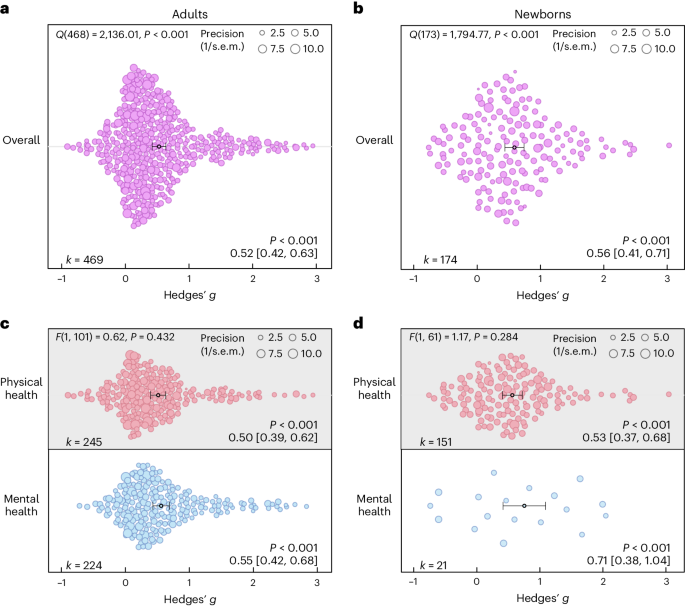

For adults, a total of n = 2,841 and n = 2,556 individuals in the touch and control groups, respectively, across 85 studies and 103 cohorts were included. The effect of touch overall was medium-sized ( t (102) = 9.74, P < 0.001, Hedges’ g = 0.52, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.42 to 0.63; Fig. 2a ). For newborns, we could include 63 cohorts across 52 studies comprising a total of n = 2,134 and n = 2,086 newborns in the touch and control groups, respectively, with an overall effect almost identical to the older age group ( t (62) = 7.53, P < 0.001, Hedges’ g = 0.56, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.71; Fig. 2b ), suggesting that, despite distinct health outcomes, touch interventions show comparable effects across newborns and adults. Using these overall effect estimates, we conducted a power sensitivity analysis of all the included primary studies to investigate whether such effects could be reliably detected 9 . Sufficient power to detect such effect sizes was rare in individual studies, as investigated by firepower plots 10 (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 ). No individual effect size from either meta-analysis was overly influential (Cook’s D < 0.06). The benefits were similar for mental and physical outcomes (mental versus physical; adults: t (101) = 0.79, P = 0.432, Hedges’ g difference of −0.05, 95% CI −0.16 to 0.07, Fig. 2c ; newborns: t (61) = 1.08, P = 0.284, Hedges’ g difference of −0.19, 95% CI −0.53 to 0.16, Fig. 2d ).

a , Orchard plot illustrating the overall benefits across all health outcomes for adults/children across 469 in part dependent effect sizes from 85 studies and 103 cohorts. b , The same as a but for newborns across 174 in part dependent effect sizes from 52 studies and 63 cohorts. c , The same as a but separating the results for physical versus mental health benefits across 469 in part dependent effect sizes from 85 studies and 103 cohorts. d , The same as b but separating the results for physical versus mental health benefits across 172 in part dependent effect sizes from 52 studies and 63 cohorts. Each dot reflects a measured effect, and the number of effects ( k ) included in the analysis is depicted in the bottom left. Mean effects and 95% CIs are presented in the bottom right and are indicated by the central black dot (mean effect) and its error bars (95% CI). The heterogeneity Q statistic is presented in the top left. Overall effects of moderator impact were assessed via an F test, and post hoc comparisons were done using t tests (two-sided test). Note that the P values above the mean effects indicate whether an effect differed significantly from a zero effect. P values were not corrected for multiple comparisons. The dot size reflects the precision of each individual effect (larger indicates higher precision). Small-study bias for the overall effect was significant ( F test, two-sided test) in the adult meta-analysis ( F (1, 101) = 21.24, P < 0.001; Supplementary Fig. 3 ) as well as in the newborn meta-analysis ( F (1, 61) = 5.25, P = 0.025; Supplementary Fig. 4 ).

Source data

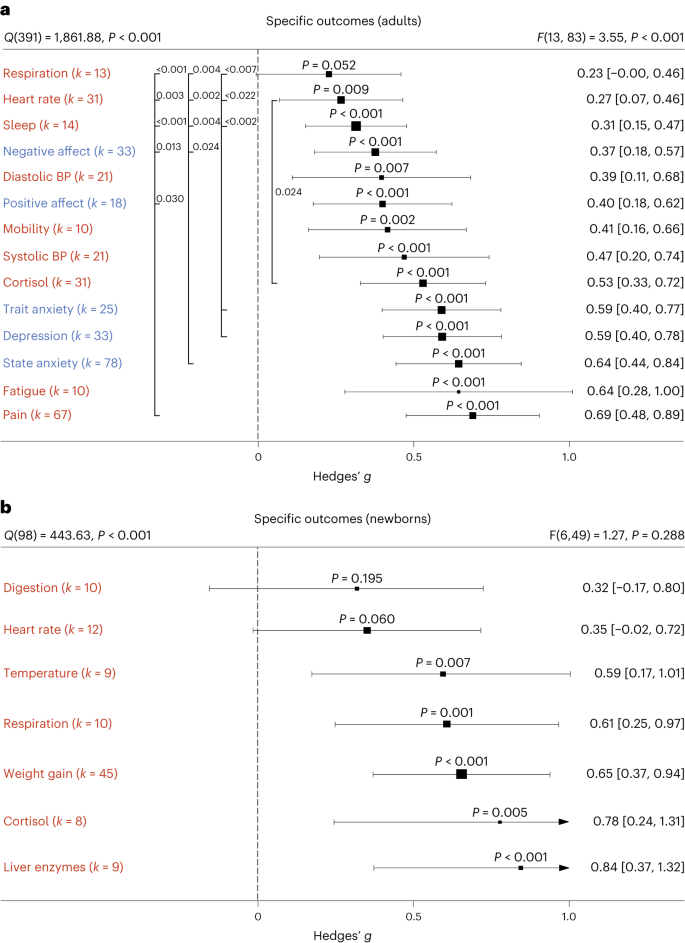

On the basis of the overall effect of both meta-analyses as well as their median sample sizes, the minimum number of studies necessary for subgroup analyses to achieve 80% power was k = 9 effects for adults and k = 8 effects for newborns (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6 ). Assessing specific health outcomes with sufficient power in more detail in adults (Fig. 3a ) revealed smaller benefits to sleep and heart rate parameters, moderate benefits to positive and negative affect, diastolic blood and systolic blood pressure, mobility and reductions of the stress hormone cortisol and larger benefits to trait and state anxiety, depression, fatigue and pain. Post hoc tests revealed stronger benefits for pain, state anxiety, depression and trait anxiety compared with respiratory, sleep and heart rate parameters (see Fig. 3 for all post hoc comparisons). Reductions in pain and state anxiety were increased compared with reductions in negative affect ( t (83) = 2.54, P = 0.013, Hedges’ g difference of 0.31, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.55; t (83) = 2.31, P = 0.024, Hedges’ g difference of 0.27, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.51). Benefits to pain symptoms were higher compared with benefits to positive affect ( t (83) = 2.22, P = 0.030, Hedges’ g difference of 0.29, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.54). Finally, touch resulted in larger benefits to cortisol release compared with heart rate parameters ( t (83) = 2.30, P = 0.024, Hedges’ g difference of 0.26, 95% CI 0.04–0.48).

a , b , Health outcomes in adults analysed across 405 in part dependent effect sizes from 79 studies and 97 cohorts ( a ) and in newborns analysed across 105 in part dependent effect sizes from 46 studies and 56 cohorts ( b ). The type of health outcomes measured differed between adults and newborns and were thus analysed separately. Numbers on the right represent the mean effect with its 95% CI in square brackets and the significance level estimating the likelihood that the effect is equal to zero. Overall effects of moderator impact were assessed via an F test, and post hoc comparisons were done using t tests (two-sided test). The F value in the top right represents a test of the hypothesis that all effects within the subpanel are equal. The Q statistic represents the heterogeneity. P values of post hoc tests are depicted whenever significant. P values above the horizontal whiskers indicate whether an effect differed significantly from a zero effect. Vertical lines indicate significant post hoc tests between moderator levels. P values were not corrected for multiple comparisons. Physical outcomes are marked in red. Mental outcomes are marked in blue.

In newborns, only physical health effects offered sufficient data for further analysis. We found no benefits for digestion and heart rate parameters. All other health outcomes (cortisol, liver enzymes, respiration, temperature regulation and weight gain) showed medium to large effects (Fig. 3b ). We found no significant differences among any specific health outcomes.

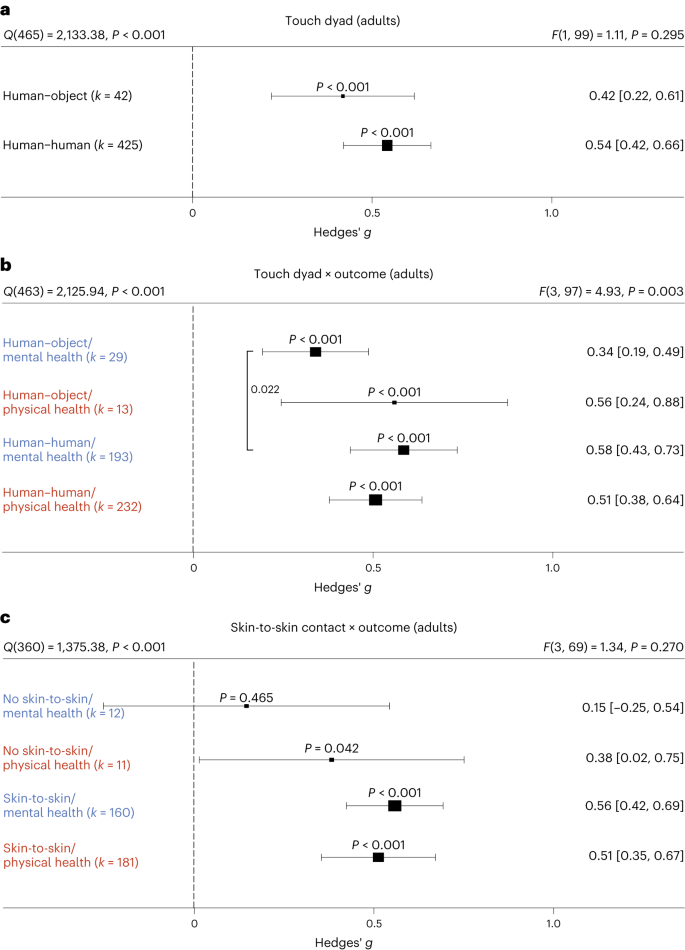

Non-human touch and skin-to-skin contact

In some situations, a fellow human is not readily available to provide affective touch, raising the question of the efficacy of touch delivered by objects and robots 11 . Overall, we found humans engaging in touch with other humans or objects to have medium-sized health benefits in adults, without significant differences ( t (99) = 1.05, P = 0.295, Hedges’ g difference of 0.12, 95% CI −0.11 to 0.35; Fig. 4a ). However, differentiating physical versus mental health benefits revealed similar benefits for human and object touch on physical health outcomes, but larger benefits on mental outcomes when humans were touched by humans ( t (97) = 2.32, P = 0.022, Hedges’ g difference of 0.24, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.44; Fig. 4b ). It must be noted that touching with an object still showed a significant effect (see Supplementary Fig. 7 for the corresponding orchard plot).

a , Forest plot comparing humans versus objects touching a human on health outcomes overall across 467 in part dependent effect sizes from 85 studies and 101 cohorts. b , The same as a but separately for mental versus physical health outcomes across 467 in part dependent effect sizes from 85 studies and 101 cohorts. c , Results with the removal of all object studies, leaving 406 in part dependent effect sizes from 71 studies and 88 cohorts to identify whether missing skin-to-skin contact is the relevant mediator of higher mental health effects in human–human interactions. Numbers on the right represent the mean effect with its 95% CI in square brackets and the significance level estimating the likelihood that the effect is equal to zero. Overall effects of moderator impact were assessed via an F test, and post hoc comparisons were done using t tests (two-sided test). The F value in the top right represents a test of the hypothesis that all effects within the subpanel are equal. The Q statistic represents the heterogeneity. P values of post hoc tests are depicted whenever significant. P values above the horizontal whiskers indicate whether an effect differed significantly from a zero effect. Vertical lines indicate significant post hoc tests between moderator levels. P values were not corrected for multiple comparisons. Physical outcomes are marked in red. Mental outcomes are marked in blue.

We considered the possibility that this effect was due to missing skin-to-skin contact in human–object interactions. Thus, we investigated human–human interactions with and without skin-to-skin contact (Fig. 4c ). In line with the hypothesis that skin-to-skin contact is highly relevant, we again found stronger mental health benefits in the presence of skin-to-skin contact that however did not achieve nominal significance ( t (69) = 1.95, P = 0.055, Hedges’ g difference of 0.41, 95% CI −0.00 to 0.82), possibly because skin-to-skin contact was rarely absent in human–human interactions, leading to a decrease in power of this analysis. Results for skin-to-skin contact as an overall moderator can be found in Supplementary Fig. 8 .

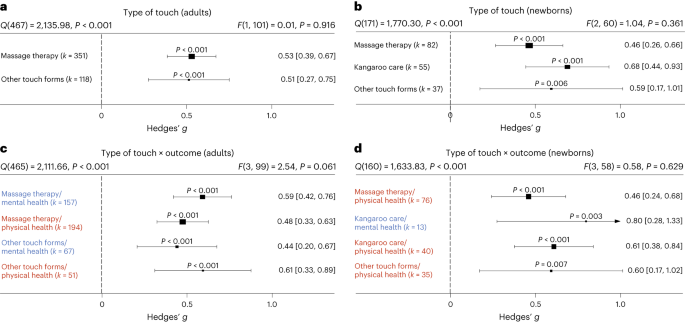

Influences of type of touch

The large majority of touch interventions comprised massage therapy in adults and kangaroo care in newborns (see Supplementary Table 1 for a complete list of interventions across studies). However, comparing the different types of touch explored across studies did not reveal significant differences in effect sizes based on touch type, be it on overall health benefits (adults: t (101) = 0.11, P = 0.916, Hedges’ g difference of 0.02, 95% CI −0.32 to 0.29; Fig. 5a ) or comparing different forms of touch separately for physical (massage therapy versus other forms: t (99) = 0.99, P = 0.325, Hedges’ g difference 0.16, 95% CI −0.15 to 0.47) or for mental health benefits (massage therapy versus other forms: t (99) = 0.75, P = 0.458, Hedges’ g difference of 0.13, 95% CI −0.22 to 0.48) in adults (Fig. 5c ; see Supplementary Fig. 9 for the corresponding orchard plot). A similar picture emerged for physical health effects in newborns (massage therapy versus kangaroo care: t (58) = 0.94, P = 0.353, Hedges’ g difference of 0.15, 95% CI −0.17 to 0.47; massage therapy versus other forms: t (58) = 0.56, P = 0.577, Hedges’ g difference of 0.13, 95% CI −0.34 to 0.60; kangaroo care versus other forms: t (58) = 0.07, P = 0.947, Hedges’ g difference of 0.02, 95% CI −0.46 to 0.50; Fig. 5d ; see also Supplementary Fig. 10 for the corresponding orchard plot). This suggests that touch types may be flexibly adapted to the setting of every touch intervention.

a , Forest plot of health benefits comparing massage therapy versus other forms of touch in adult cohorts across 469 in part dependent effect sizes from 85 studies and 103 cohorts. b , Forest plot of health benefits comparing massage therapy, kangaroo care and other forms of touch for newborns across 174 in part dependent effect sizes from 52 studies and 63 cohorts. c , The same as a but separating mental and physical health benefits across 469 in part dependent effect sizes from 85 studies and 103 cohorts. d , The same as b but separating mental and physical health outcomes where possible across 164 in part dependent effect sizes from 51 studies and 62 cohorts. Note that an insufficient number of studies assessed mental health benefits of massage therapy or other forms of touch to be included. Numbers on the right represent the mean effect with its 95% CI in square brackets and the significance level estimating the likelihood that the effect is equal to zero. Overall effects of moderator impact were assessed via an F test, and post hoc comparisons were done using t tests (two-sided test). The F value in the top right represents a test of the hypothesis that all effects within the subpanel are equal. The Q statistic represents heterogeneity. P values of post hoc tests are depicted whenever significant. P values above the horizontal whiskers indicate whether an effect differed significantly from a zero effect. Vertical lines indicate significant post hoc tests between moderator levels. P values were not corrected for multiple comparisons. Physical outcomes are marked in red. Mental outcomes are marked in blue.

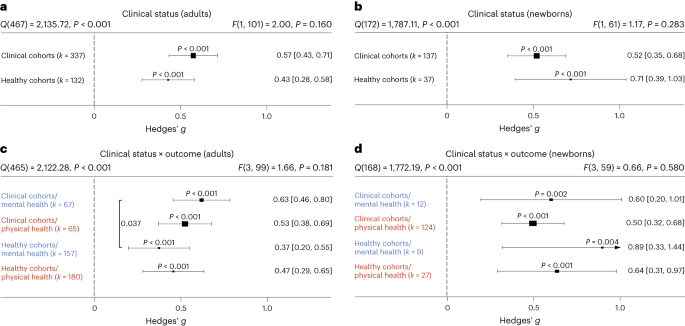

The role of clinical status

Most research on touch interventions has focused on clinical samples, but are benefits restricted to clinical cohorts? We found health benefits to be significant in clinical and healthy populations (Fig. 6 ), whether all outcomes are considered (Fig. 6a,b ) or physical and mental health outcomes are separated (Fig. 6c,d , see Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12 for the corresponding orchard plots). In adults, however, we found higher mental health benefits for clinical populations compared with healthy ones (Fig. 6c ; t (99) = 2.11, P = 0.037, Hedges’ g difference of 0.25, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.49).

a , Health benefits for clinical cohorts of adults versus healthy cohorts of adults across 469 in part dependent effect sizes from 85 studies and 103 cohorts. b , The same as a but for newborn cohorts across 174 in part dependent effect sizes from 52 studies and 63 cohorts. c , The same as a but separating mental versus physical health benefits across 469 in part dependent effect sizes from 85 studies and 103 cohorts. d , The same as b but separating mental versus physical health benefits across 172 in part dependent effect sizes from 52 studies and 63 cohorts. Numbers on the right represent the mean effect with its 95% CI in square brackets and the significance level estimating the likelihood that the effect is equal to zero. Overall effects of moderator impact were assessed via an F test, and post hoc comparisons were done using t tests (two-sided test).The F value in the top right represents a test of the hypothesis that all effects within the subpanel are equal. The Q statistic represents the heterogeneity. P values of post hoc tests are depicted whenever significant. P values above the horizontal whiskers indicate whether an effect differed significantly from a zero effect. Vertical lines indicate significant post hoc tests between moderator levels. P values were not corrected for multiple comparisons. Physical outcomes are marked in red. Mental outcomes are marked in blue.

A more detailed analysis of specific clinical conditions in adults revealed positive mental and physical health benefits for almost all assessed clinical disorders. Differences between disorders were not found, with the exception of increased effectiveness of touch interventions in neurological disorders (Supplementary Fig. 13 ).

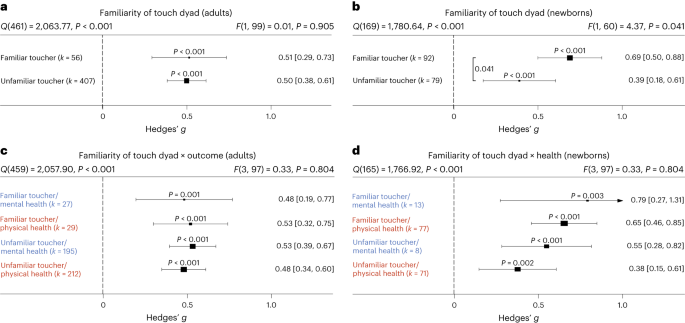

Familiarity in the touching dyad and intervention location

Touch interventions can be performed either by familiar touchers (partners, family members or friends) or by unfamiliar touchers (health care professionals). In adults, we did not find an impact of familiarity of the toucher ( t (99) = 0.12, P = 0.905, Hedges’ g difference of 0.02, 95% CI −0.27 to 0.24; Fig. 7a ; see Supplementary Fig. 14 for the corresponding orchard plot). Similarly, investigating the impact on mental and physical health benefits specifically, no significant differences could be detected, suggesting that familiarity is irrelevant in adults. In contrast, touch applied to newborns by their parents (almost all studies only included touch by the mother) was significantly more beneficial compared with unfamiliar touch ( t (60) = 2.09, P = 0.041, Hedges’ g difference of 0.30, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.59) (Fig. 7b ; see Supplementary Fig. 15 for the corresponding orchard plot). Investigating mental and physical health benefits specifically revealed no significant differences. Familiarity with the location in which the touch was applied (familiar being, for example, the participants’ home) did not influence the efficacy of touch interventions (Supplementary Fig. 16 ).

a , Health benefits for being touched by a familiar (for example, partner, family member or friend) versus unfamiliar toucher (health care professional) across 463 in part dependent effect sizes from 83 studies and 101 cohorts. b , The same as a but for newborn cohorts across 171 in part dependent effect sizes from 51 studies and 62 cohorts. c , The same as a but separating mental versus physical health benefits across 463 in part dependent effect sizes from 83 studies and 101 cohorts. d , The same as b but separating mental versus physical health benefits across 169 in part dependent effect sizes from 51 studies and 62 cohorts. Numbers on the right represent the mean effect with its 95% CI in square brackets and the significance level estimating the likelihood that the effect is equal to zero. Overall effects of moderator impact were assessed via an F test, and post hoc comparisons were done using t tests (two-sided test). The F value in the top right represents a test of the hypothesis that all effects within the subpanel are equal. The Q statistic represents the heterogeneity. P values of post hoc tests are depicted whenever significant. P values above the horizontal whiskers indicate whether an effect differed significantly from a zero effect. Vertical lines indicate significant post hoc tests between moderator levels. P values were not corrected for multiple comparisons. Physical outcomes are marked in red. Mental outcomes are marked in blue.

Frequency and duration of touch interventions

How often and for how long should touch be delivered? For adults, the median touch duration across studies was 20 min and the median number of touch interventions was four sessions with an average time interval of 2.3 days between each session. For newborns, the median touch duration across studies was 17.5 min and the median number of touch interventions was seven sessions with an average time interval of 1.3 days between each session.

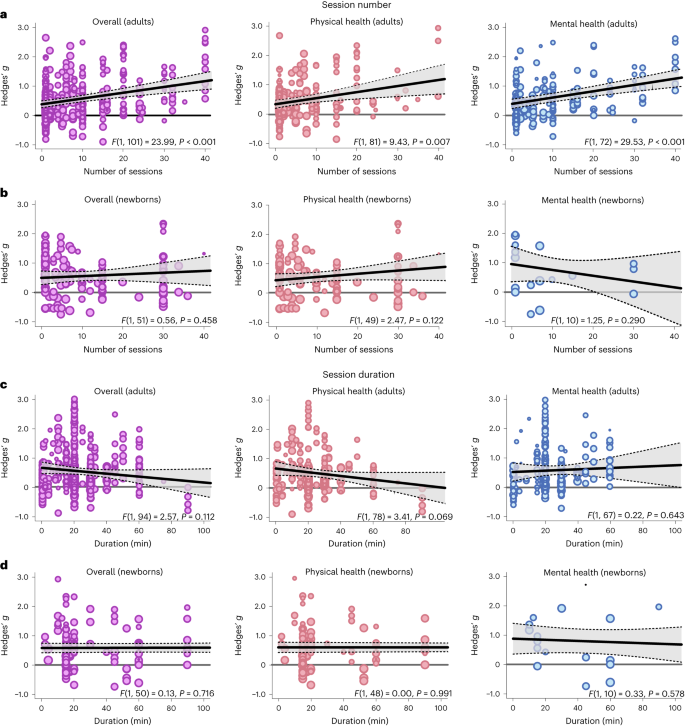

Delivering more touch sessions increased benefits in adults, whether overall ( t (101) = 4.90, P < 0.001, Hedges’ g = 0.02, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.03), physical ( t (81) = 3.07, P = 0.003, Hedges’ g = 0.02, 95% CI 0.01–0.03) or mental benefits ( t (72) = 5.43, P < 0.001, Hedges’ g = 0.02, 95% CI 0.01–0.03) were measured (Fig. 8a ). A closer look at specific outcomes for which sufficient data were available revealed that positive associations between the number of sessions and outcomes were found for trait anxiety ( t (12) = 7.90, P < 0.001, Hedges’ g = 0.03, 95% CI 0.02–0.04), depression ( t (20) = 10.69, P < 0.001, Hedges’ g = 0.03, 95% CI 0.03–0.04) and pain ( t (37) = 3.65, P < 0.001, Hedges’ g = 0.03, 95% CI 0.02–0.05), indicating a need for repeated sessions to improve these adverse health outcomes. Neither increasing the number of sessions for newborns nor increasing the duration of touch per session in adults or newborns increased health benefits, be they physical or mental (Fig. 8b–d ). For continuous moderators in adults, we also looked at specific health outcomes as sufficient data were generally available for further analysis. Surprisingly, we found significant negative associations between touch duration and reductions of cortisol ( t (24) = 2.71, P = 0.012, Hedges’ g = −0.01, 95% CI −0.01 to −0.00) and heart rate parameters ( t (21) = 2.35, P = 0.029, Hedges’ g = −0.01, 95% CI −0.02 to −0.00).

a , Meta-regression analysis examining the association between the number of sessions applied and the effect size in adults, either on overall health benefits (left, 469 in part dependent effect sizes from 85 studies and 103 cohorts) or for physical (middle, 245 in part dependent effect sizes from 69 studies and 83 cohorts) or mental benefits (right, 224 in part dependent effect sizes from 60 studies and 74 cohorts) separately. b , The same as a for newborns (overall: 150 in part dependent effect sizes from 46 studies and 53 cohorts; physical health: 127 in part dependent effect sizes from 44 studies and 51 cohorts; mental health: 21 in part dependent effect sizes from 11 studies and 12 cohorts). c , d the same as a ( c ) and b ( d ) but for the duration of the individual sessions. For adults, 449 in part dependent effect sizes across 80 studies and 96 cohorts were included in the overall analysis. The analysis of physical health benefits included 240 in part dependent effect sizes across 67 studies and 80 cohorts, and the analysis of mental health benefits included 209 in part dependent effect sizes from 56 studies and 69 cohorts. For newborns, 145 in part dependent effect sizes across 45 studies and 52 cohorts were included in the overall analysis. The analysis of physical health benefits included 122 in part dependent effect sizes across 43 studies and 50 cohorts, and the analysis of mental health benefits included 21 in part dependent effect sizes from 11 studies and 12 cohorts. Each dot represents an effect size. Its size indicates the precision of the study (larger indicates better). Overall effects of moderator impact were assessed via an F test (two-sided test). The P values in each panel represent the result of a regression analysis testing the hypothesis that the slope of the relationship is equal to zero. P values are not corrected for multiple testing. The shaded area around the regression line represents the 95% CI.

Demographic influences of sex and age

We used the ratio between women and men in the single-study samples as a proxy for sex-specific effects. Sex ratios were heavily skewed towards larger numbers of women in each cohort (median 83% women), and we could not find significant associations between sex ratio and overall ( t (62) = 0.08, P = 0.935, Hedges’ g = 0.00, 95% CI −0.00 to 0.01), mental ( t (43) = 0.55, P = 0.588, Hedges’ g = 0.00, 95% CI −0.00 to 0.01) or physical health benefits ( t (51) = 0.15, P = 0.882, Hedges’ g = −0.00, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.01). For specific outcomes that could be further analysed, we found a significant positive association of sex ratio with reductions in cortisol secretion ( t (18) = 2.31, P = 0.033, Hedges’ g = 0.01, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.01) suggesting stronger benefits in women. In contrast to adults, sex ratios were balanced in samples of newborns (median 53% girls). For newborns, there was no significant association with overall ( t (36) = 0.77, P = 0.447, Hedges’ g = −0.01, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.01) and physical health benefits of touch ( t (35) = 0.93, P = 0.359, Hedges’ g = −0.01, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.01). Mental health benefits did not provide sufficient data for further analysis.

The median age in the adult meta-analysis was 42.6 years (s.d. 21.16 years, range 4.5–88.4 years). There was no association between age and the overall ( t (73) = 0.35, P = 0.727, Hedges’ g = 0.00, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.01), mental ( t (53) = 0.94, P = 0.353, Hedges’ g = 0.01, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.02) and physical health benefits of touch ( t (60) = 0.16, P = 0.870, Hedges’ g = 0.00, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.01). Looking at specific health outcomes, we found significant positive associations between mean age and improved positive affect ( t (10) = 2.54, P = 0.030, Hedges’ g = 0.01, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.02) as well as systolic blood pressure ( t (11) = 2.39, P = 0.036, Hedges’ g = 0.02, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.04).

A list of touched body parts can be found in Supplementary Table 1 . For the touched body part, we found significantly higher health benefits for head touch compared with arm touch ( t (40) = 2.14, P = 0.039, Hedges’ g difference of 0.78, 95% CI 0.07 to 1.49) and torso touch ( t (40) = 2.23, P = 0.031; Hedges’ g difference of 0.84, 95% CI 0.10 to 1.58; Supplementary Fig. 17 ). Touching the arm resulted in lower mental health compared with physical health benefits ( t (37) = 2.29, P = 0.028, Hedges’ g difference of −0.35, 95% CI −0.65 to −0.05). Furthermore, we found a significantly increased physical health benefit when the head was touched as opposed to the torso ( t (37) = 2.10, P = 0.043, Hedges’ g difference of 0.96, 95% CI 0.06 to 1.86). Thus, head touch such as a face or scalp massage could be especially beneficial.

Directionality

In adults, we tested whether a uni- or bidirectional application of touch mattered. The large majority of touch was applied unidirectionally ( k = 442 of 469 effects). Unidirectional touch had higher health benefits ( t (101) = 2.17, P = 0.032, Hedges’ g difference of 0.30, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.58) than bidirectional touch. Specifically, mental health benefits were higher in unidirectional touch ( t (99) = 2.33, P = 0.022, Hedges’ g difference of 0.46, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.66).

Study location

For adults, we found significantly stronger health benefits of touch in South American compared with North American cohorts ( t (95) = 2.03, P = 0.046, Hedges’ g difference of 0.37, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.73) and European cohorts ( t (95) = 2.22, P = 0.029, Hedges’ g difference of 0.36, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.68). For newborns, we found weaker effects in North American cohorts compared to Asian ( t (55) = 2.28, P = 0.026, Hedges’ g difference of −0.37, 95% CI −0.69 to −0.05) and European cohorts ( t (55) = 2.36, P = 0.022, Hedges’ g difference of −0.40, 95% CI −0.74 to −0.06). Investigating the interaction with mental and physical health benefits did not reveal any effects of study location in both meta-analyses (Supplementary Fig. 18 ).

Systematic review of studies without effect sizes

All studies where effect size data could not be obtained or that did not meet the meta-analysis inclusion criteria can be found on the OSF project 12 in the file ‘Study_lists_final_revised.xlsx’ (sheet ‘Studies_without_effect_sizes’). Specific reasons for exclusion are furthermore documented in Supplementary Table 2 . For human health outcomes assessed across 56 studies and n = 2,438 individuals, interventions mostly comprised massage therapy ( k = 86 health outcomes) and kangaroo care ( k = 33 health outcomes). For datasets where no effect size could be computed, 90.0% of mental health and 84.3% of physical health parameters were positively impacted by touch. Positive impact of touch did not differ between types of touch interventions. These results match well with the observations of the meta-analysis of a highly positive benefit of touch overall, irrespective of whether a massage or any other intervention is applied.

We also assessed health outcomes in animals across 19 studies and n = 911 subjects. Most research was conducted in rodents. Animals that received touch were rats (ten studies, k = 16 health outcomes), mice (four studies, k = 7 health outcomes), macaques (two studies, k = 3 health outcomes), cats (one study, k = 3 health outcomes), lambs (one study, k = 2 health outcomes) and coral reef fish (one study, k = 1 health outcome). Touch interventions mostly comprised stroking ( k = 13 health outcomes) and tickling ( k = 10 health outcomes). For animal studies, 71.4% of effects showed benefits to mental health-like parameters and 81.8% showed positive physical health effects. We thus found strong evidence that touch interventions, which were mostly conducted by humans (16 studies with human touch versus 3 studies with object touch), had positive health effects in animal species as well.

The key aim of the present study was twofold: (1) to provide an estimate of the effect size of touch interventions and (2) to disambiguate moderating factors to potentially tailor future interventions more precisely. Overall, touch interventions were beneficial for both physical and mental health, with a medium effect size. Our work illustrates that touch interventions are best suited for reducing pain, depression and anxiety in adults and children as well as for increasing weight gain in newborns. These findings are in line with previous meta-analyses on this topic, supporting their conclusions and their robustness to the addition of more datasets. One limitation of previous meta-analyses is that they focused on specific health outcomes or populations, despite primary studies often reporting effects on multiple health parameters simultaneously (for example, ref. 13 focusing on neck and shoulder pain and ref. 14 focusing on massage therapy in preterms). To our knowledge, only ref. 5 provides a multivariate picture for a large number of dependent variables. However, this study analysed their data in separate random effects models that did not account for multivariate reporting nor for the multilevel structure of the data, as such approaches have only become available recently. Thus, in addition to adding a substantial amount of new data, our statistical approach provides a more accurate depiction of effect size estimates. Additionally, our study investigated a variety of moderating effects that did not reach significance (for example, sex ratio, mean age or intervention duration) or were not considered (for example, the benefits of robot or object touch) in previous meta-analyses in relation to touch intervention efficacy 5 , probably because of the small number of studies with information on these moderators in the past. Owing to our large-scale approach, we reached high statistical power for many moderator analyses. Finally, previous meta-analyses on this topic exclusively focused on massage therapy in adults or kangaroo care in newborns 15 , leaving out a large number of interventions that are being carried out in research as well as in everyday life to improve well-being. Incorporating these studies into our study, we found that, in general, both massages and other types of touch, such as gentle touch, stroking or kangaroo care, showed similar health benefits.

While it seems to be less critical which touch intervention is applied, the frequency of interventions seems to matter. More sessions were positively associated with the improvement of trait outcomes such as depression and anxiety but also pain reductions in adults. In contrast to session number, increasing the duration of individual sessions did not improve health effects. In fact, we found some indications of negative relationships in adults for cortisol and blood pressure. This could be due to habituating effects of touch on the sympathetic nervous system and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, ultimately resulting in diminished effects with longer exposure, or decreased pleasantness ratings of affective touch with increasing duration 16 . For newborns, we could not support previous notions that the duration of the touch intervention is linked to benefits in weight gain 17 . Thus, an ideal intervention protocol does not seem to have to be excessively long. It should be noted that very few interventions lasted less than 5 min, and it therefore remains unclear whether very short interventions have the same effect.

A critical issue highlighted in the pandemic was the lack of touch due to social restrictions 18 . To accommodate the need for touch in individuals with small social networks (for example, institutionalized or isolated individuals), touch interventions using objects/robots have been explored in the past (for a review, see ref. 11 ). We show here that touch interactions outside of the human–human domain are beneficial for mental and physical health outcomes. Importantly, object/robot touch was not as effective in improving mental health as human-applied touch. A sub-analysis of missing skin-to-skin contact among humans indicated that mental health effects of touch might be mediated by the presence of skin-to-skin contact. Thus, it seems profitable to include skin-to-skin contact in future touch interventions, in line with previous findings in newborns 19 . In robots, recent advancements in synthetic skin 20 should be investigated further in this regard. It should be noted that, although we did not observe significant differences in physical health benefits between human–human and human–object touch, the variability of effect sizes was higher in human–object touch. The conditions enabling object or robot interactions to improve well-being should therefore be explored in more detail in the future.

Touch was beneficial for both healthy and clinical cohorts. These data are critical as most previous meta-analytic research has focused on individuals diagnosed with clinical disorders (for example, ref. 6 ). For mental health outcomes, we found larger effects in clinical cohorts. A possible reason could relate to increased touch wanting 21 in patients. For example, loneliness often co-occurs with chronic illnesses 22 , which are linked to depressed mood and feelings of anxiety 23 . Touch can be used to counteract this negative development 24 , 25 . In adults and children, knowing the toucher did not influence health benefits. In contrast, familiarity affected overall health benefits in newborns, with parental touch being more beneficial than touch applied by medical staff. Previous studies have suggested that early skin-to-skin contact and exposure to maternal odour is critical for a newborn’s ability to adapt to a new environment 26 , supporting the notion that parental care is difficult to substitute in this time period.

With respect to age-related effects, our data further suggest that increasing age was associated with a higher benefit through touch for systolic blood pressure. These findings could potentially be attributed to higher basal blood pressure 27 with increasing age, allowing for a stronger modulation of this parameter. For sex differences, our study provides some evidence that there are differences between women and men with respect to health benefits of touch. Overall, research on sex differences in touch processing is relatively sparse (but see refs. 28 , 29 ). Our results suggest that buffering effects against physiological stress are stronger in women. This is in line with increased buffering effects of hugs in women compared with men 30 . The female-biased primary research in adults, however, begs for more research in men or non-binary individuals. Unfortunately, our study could not dive deeper into this topic as health benefits broken down by sex or gender were almost never provided. Recent research has demonstrated that sensory pleasantness is affected by sex and that this also interacts with the familiarity of the other person in the touching dyad 29 , 31 . In general, contextual factors such as sex and gender or the relationship of the touching dyad, differences in cultural background or internal states such as stress have been demonstrated to be highly influential in the perception of affective touch and are thus relevant to maximizing the pleasantness and ultimately the health benefits of touch interactions 32 , 33 , 34 . As a positive personal relationship within the touching dyad is paramount to induce positive health effects, future research applying robot touch to promote well-being should therefore not only explore synthetic skin options but also focus on improving robots as social agents that form a close relationship with the person receiving the touch 35 .

As part of the systematic review, we also assessed the effects of touch interventions in non-human animals. Mimicking the results of the meta-analysis in humans, beneficial effects of touch in animals were comparably strong for mental health-like and physical health outcomes. This may inform interventions to promote animal welfare in the context of animal experiments 36 , farming 37 and pets 38 . While most studies investigated effects in rodents, which are mostly used as laboratory animals, these results probably transfer to livestock and common pets as well. Indeed, touch was beneficial in lambs, fish and cats 39 , 40 , 41 . The positive impact of human touch in rodents also allows for future mechanistic studies in animal models to investigate how interventions such as tickling or stroking modulate hormonal and neuronal responses to touch in the brain. Furthermore, the commonly proposed oxytocin hypothesis can be causally investigated in these animal models through, for example, optogenetic or chemogenetic techniques 42 . We believe that such translational approaches will further help in optimizing future interventions in humans by uncovering the underlying mechanisms and brain circuits involved in touch.

Our results offer many promising avenues to improve future touch interventions, but they also need to be discussed in light of their limitations. While the majority of findings showed robust health benefits of touch interventions across moderators when compared with a null effect, post hoc tests of, for example, familiarity effects in newborns or mental health benefit differences between human and object touch only barely reached significance. Since we computed a large number of statistical tests in the present study, there is a risk that these results are false positives. We hope that researchers in this field are stimulated by these intriguing results and target these questions by primary research through controlled experimental designs within a well-powered study. Furthermore, the presence of small-study bias in both meta-analyses is indicative that the effect size estimates presented here might be overestimated as null results are often unpublished. We want to stress however that this bias is probably reduced by the multivariate reporting of primary studies. Most studies that reported on multiple health outcomes only showed significant findings for one or two among many. Thus, the multivariate nature of primary research in this field allowed us to include many non-significant findings in the present study. Another limitation pertains to the fact that we only included articles in languages mostly spoken in Western countries. As a large body of evidence comes from Asian countries, it could be that primary research was published in languages other than specified in the inclusion criteria. Thus, despite the large and inclusive nature of our study, some studies could have been missed regardless. Another factor that could not be accounted for in our meta-analysis was that an important prerequisite for touch to be beneficial is its perceived pleasantness. The level of pleasantness associated with being touched is modulated by several parameters 34 including cultural acceptability 43 , perceived humanness 44 or a need for touch 45 , which could explain the observed differences for certain moderators, such as human–human versus robot–human interaction. Moreover, the fact that secondary categorical moderators could not be investigated with respect to specific health outcomes, owing to the lack of data points, limits the specificity of our conclusions in this regard. It thus remains unclear whether, for example, a decreased mental health benefit in the absence of skin-to-skin contact is linked mostly to decreased anxiolytic effects, changes in positive/negative affect or something else. Since these health outcomes are however highly correlated 46 , it is likely that such effects are driven by multiple health outcomes. Similarly, it is important to note that our conclusions mainly refer to outcomes measured close to the touch intervention as we did not include long-term outcomes. Finally, it needs to be noted that blinding towards the experimental condition is essentially impossible in touch interventions. Although we compared the touch intervention with other interventions, such as relaxation therapy, as control whenever possible, contributions of placebo effects cannot be ruled out.

In conclusion, we show clear evidence that touch interventions are beneficial across a large number of both physical and mental health outcomes, for both healthy and clinical cohorts, and for all ages. These benefits, while influenced in their magnitude by study cohorts and intervention characteristics, were robustly present, promoting the conclusion that touch interventions can be systematically employed across the population to preserve and improve our health.

Open science practices

All data and code are accessible in the corresponding OSF project 12 . The systematic review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42022304281) before the start of data collection. We deviated from the pre-registered plan as follows:

Deviation 1: During our initial screening for the systematic review, we were confronted with a large number of potential health outcomes to look at. This observation of multivariate outcomes led us to register an amendment during data collection (but before any effect size or moderator screening). In doing so, we aimed to additionally extract meta-analytic effects for a more quantitative assessment of our review question that can account for multivariate data reporting and dependencies of effects within the same study. Furthermore, as we noted a severe lack of studies with respect to health outcomes for animals during the inclusion assessment for the systematic review, we decided that the meta-analysis would only focus on outcomes that could be meaningfully analysed on the meta-analytic level and therefore only included health outcomes of human participants.

Deviation 2: In the pre-registration, we did not explicitly exclude non-randomized trials. Since an explicit use of non-randomization for group allocation significantly increases the risk of bias, we decided to exclude them a posteriori from data analysis.

Deviation 3: In the pre-registration, we outlined a tertiary moderator level, namely benefits of touch application versus touch reception. This level was ignored since no included study specifically investigated the benefits of touch application by itself.

Deviation 4: In the pre-registration, we suggested using the RoBMA function 47 to provide a Bayesian framework that allows for a more accurate assessment of publication bias beyond small-study bias. Unfortunately, neither multilevel nor multivariate data structures are supported by the RoBMA function, to our knowledge. For this reason, we did not further pursue this analysis, as the hierarchical nature of the data would not be accounted for.

Deviation 5: Beyond the pre-registered inclusion and exclusion criteria, we also excluded dissertations owing to their lack of peer review.

Deviation 6: In the pre-registration, we stated to investigate the impact of sex of the person applying the touch. This moderator was not further analysed, as this information was rarely given and the individuals applying the touch were almost exclusively women (7 males, 24 mixed and 85 females in studies on adults/children; 3 males, 17 mixed and 80 females in studied on newborns).

Deviation 7: The time span of the touch intervention as assessed by subtracting the final day of the intervention from the first day was not investigated further owing to its very high correlation with the number of sessions ( r (461) = 0.81 in the adult meta-analysis, r (145) = 0.84 in the newborn meta-analysis).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria