Mga Sanaysay Tungkol sa Mental Health (7 Sanaysay)

Ang mga sanaysay tungkol sa mental health na mababasa mo sa post na ito ay masusing isinulat upang maghatid ng kaalaman, inspirasyon, at suporta sa mga mambabasa na nagnanais na mas maintindihan ang kahalagahan ng mental health sa ating buhay.

Mababasa mo dito ang mga sanaysay na tumatalakay sa iba’t ibang aspekto ng mental health – mula sa kahalagahan nito sa ating pang-araw-araw na pamumuhay, ang epekto ng pandemya sa ating kaisipan, hanggang sa mga hakbang na maaari nating gawin upang maging mas malusog at matatag ang ating mentalidad.

Nawa’y makatulong sa iyo ang mga nilalaman ng sanaysay na mababasa mo dito patungo sa pagkakaroon ng mas malalim na pag-unawa at pagpapahalaga sa mental health. Sama-sama nating pagyamanin ang ating kaalaman at kamalayan, at magbigay ng suporta sa mga taong nangangailangan upang maitaguyod ang isang mas maunlad at malusog na lipunan para sa lahat.

Mga Halimbawa ng Sanaysay Tungkol sa Mental Health

Sanaysay tungkol sa mental health, ang kahalagahan ng mental health sa ating buhay, epekto ng pandemya sa mental health, bakit mahalaga ang mental health, mental health ng kabataan sa bagong normal, epekto ng pandemya sa mental health ng mga kabataan, ang mental health sa makabagong panahon: pag-unawa, kamalayan, at suporta.

Sa makabagong mundo na ating ginagalawan, ang isyu ng mental health ay isa sa mga pangunahing aspeto ng kalusugan na dapat nating bigyang-pansin. Sa kabila ng mga teknolohiya at pag-unlad na ating natatamasa, ang mental health ay isa sa mga bagay na madalas na nakakaligtaan. Ang sanaysay na ito ay tatalakay sa kahalagahan ng mental health, ang mga kadahilanan na nakakaapekto dito, at ang mga hakbang na maaari nating gawin upang maging mas malusog ang ating kaisipan.

Una sa lahat, ano nga ba ang mental health? Ang mental health o kalusugang pangkaisipan ay tumutukoy sa kagalingan ng isang indibidwal sa aspeto ng emosyonal, sikolohikal, at sosyal na aspekto ng kanyang buhay. Ito ay tumutukoy sa kung paano natin pinangangasiwaan ang ating mga emosyon, pag-iisip, at pakikitungo sa ibang tao. Ang isang malusog na mental health ay mahalaga upang magkaroon tayo ng balanse at magandang kalidad ng buhay.

Ang mental health ay hindi lamang para sa mga mayroong problema sa kaisipan. Ang bawat isa sa atin ay may mental health na kailangang pangalagaan at paunlarin. Sa katunayan, ang mental health ay maaaring magdulot ng malalim na impluwensya sa ating pisikal na kalusugan. Mayroong iba’t-ibang kadahilanan na nakakaapekto sa mental health, gaya ng genetics, kapaligiran, karanasan sa buhay, at iba pang mga mapanganib na kadahilanan.

Upang mapanatili ang ating mental health, mahalaga na tayo ay magkaroon ng tamang balanse sa ating buhay. Narito ang ilang mga paraan upang pangalagaan ang mental health:

- Kumilos at maging aktibo. Ang regular na ehersisyo ay isa sa mga pinakamabisang paraan upang mapanatili ang ating mental health. Ito ay nakakatulong na maibsan ang stress, pagod, at maging ang mga sintomas ng depresyon at anxiety.

- Maging mulat sa iyong emosyon. Ang pagiging bukas sa ating mga emosyon ay tumutulong na maunawaan natin ang ating mga damdamin at kung paano natin ito haharapin. Sa pamamagitan nito, mas mapapabuti natin ang ating emosyonal na kalusugan.

- Magkaroon ng sapat na tulog. Ang sapat na tulog ay isa sa mga pinakamahalagang sangkap ng mental health. Ito ay tumutulong na mabawasan ang stress at pagod, at magbigay ng enerhiya para sa susunod na araw.

- Kumain ng masustansyang pagkain. Ang tamang nutrisyon ay isa pang mahalagang sangkap ng mental health. Ang mga pagkain na mayaman sa nutrients, tulad ng prutas, gulay, lean protein, at whole grains, ay nakakatulong upang mapanatili ang ating mental health at mabawasan ang pagkakataon ng pagkakaroon ng depresyon at iba pang mga mental na sakit.

- Kumonekta sa ibang tao. Ang pakikipag-ugnayan sa pamilya, kaibigan, at komunidad ay mahalaga sa ating mental health. Ang pagkakaroon ng suporta mula sa mga taong malapit sa atin ay nakakatulong upang mabawasan ang stress, maramdaman ang pagmamahal at pag-aaruga, at makakuha ng payo kung kinakailangan.

- Maglaan ng oras para sa sarili. Ang pagbibigay ng oras sa ating sarili ay mahalaga upang ma-refresh ang ating isipan at emosyon. Maaari itong sa pamamagitan ng pagbabasa, paglalakad, pagmumuni-muni, o anumang aktibidad na nagbibigay sa atin ng kasiyahan at pahinga.

- Huwag matakot humingi ng tulong. Kung sa tingin mo ay mayroong problema sa iyong mental health, huwag matakot na humingi ng tulong mula sa mga propesyonal, tulad ng mga psychologist, psychiatrist, o counselor. Sila ay makakatulong upang matukoy ang iyong kalagayan at magbigay ng nararapat na interbensyon.

Sa kabuuan, ang mental health ay isang mahalagang aspekto ng ating buhay na dapat nating bigyang halaga at pangalagaan. Ang pagiging malusog sa isip at emosyon ay makapagdudulot ng positibong epekto sa ating pisikal na kalusugan, relasyon sa ibang tao, at ang ating pang-araw-araw na gawain. Kung ating babalikan ang mga hakbang na nabanggit, maaari nating mas mapangalagaan ang ating mental health at magkaroon ng mas masagana at maligayang buhay.

Sa mundong puno ng hamon, stress, at pagsubok, napakahalaga na ating pahalagahan ang ating mental health. Ang mental health ay tumutukoy sa kalagayan ng ating kaisipan at emosyon na may malaking epekto sa ating pang-araw-araw na buhay. Ang sanaysay na ito ay naglalayong bigyang-diin ang kahalagahan ng mental health sa ating buhay, ang mga paraan kung paano ito mapangangalagaan, at ang mga hamon na kinakaharap ng mga Pilipino sa aspektong ito.

Unang-una, dapat nating maintindihan ang konsepto ng mental health. Ito ay may malaking kaugnayan sa ating kasiyahan, kapayapaan ng isip, at pagkakaroon ng malusog na relasyon sa ating sarili at sa ibang tao. Ang mental health ay lubhang mahalaga dahil ito ang nagbibigay-daan sa atin upang mas maayos na harapin ang mga pagsubok sa buhay, maging mas produktibo, at makamit ang ating mga layunin.

Upang mapangalagaan ang ating mental health, mahalaga na sundin natin ang mga sumusunod na paraan:

- Maging balanse ang ating pamumuhay: Tiyaking may sapat na oras para sa pag-aaral, trabaho, pahinga, at mga libangan. Iwasan ang sobrang pagtatrabaho o paglalaro ng video games dahil maaaring maging sanhi ito ng stress o kawalan ng motibasyon.

- Kumain ng masustansya at maging aktibo: Ang pagkain ng masusustansya at pag-eehersisyo ay maaaring magbigay ng positibong epekto sa ating mental health. Maaari rin itong makatulong upang mabawasan ang stress at mapabuti ang ating antas ng enerhiya.

- Matutunan ang stress management: Maghanap ng mga paraan upang mabawasan ang stress, tulad ng paggawa ng relaxation techniques, paghinga ng malalim, o pagpapraktis ng mindfulness meditation.

- Huwag matakot humingi ng tulong: Kung nahihirapan tayo sa ating mental health, huwag matakot humingi ng tulong mula sa pamilya, mga kaibigan, o propesyonal na mental health provider. Ito ay isang mahalagang hakbang upang malunasan ang anumang problema na kinakaharap natin.

Ang mga Pilipino ay kinakaharap ang ilang mga hamon sa aspektong ito. Isa sa mga ito ay ang kawalan ng sapat na kaalaman tungkol sa mental health, na nagsasadlak sa iba’t ibang stigma at diskriminasyon. Maraming Pilipino ang hindi umaasa ng tulong dahil sa takot na maging biktima ng mga negatibong pagtingin at paniniwala. Kaya naman, mahalaga na maging bukas ang ating isipan at puso, at tulungan natin ang isa’t isa upang mawala ang stigma na nakapaligid sa mental health.

Ang isa pang hamon ay ang limitadong access sa mental health services sa Pilipinas. Sa kasalukuyan, hindi lahat ng mga komunidad ay may sapat na pasilidad at mental health professionals upang tugunan ang mga pangangailangan ng mga taong nangangailangan ng tulong. Kaya naman, mahalaga na palakasin ang pampublikong suporta at pondo para sa mental health, upang marami pang Pilipino ang makakamit ang kanilang mental health needs.

Ang mental health ay isang napakahalagang aspekto ng ating buhay, at hindi dapat balewalain. Bilang isang Pilipino, nais kong ibahagi ang aking kaalaman at karanasan upang makatulong sa pagpapalaganap ng impormasyon tungkol sa mental health, at upang maging inspirasyon sa iba na mas maunawaan at magkaroon ng malasakit sa mga taong nakakaranas ng mga mental health challenges.

Sa pagtatapos, ang mental health ay isang kayamanan na dapat nating pangalagaan. Sa pamamagitan ng pagbibigay ng tamang suporta, kaalaman, at mga serbisyo, maaari nating ipakita ang ating pagmamahal at malasakit sa ating kapwa Pilipino na nakakaranas ng mga mental health struggles. Sa ganitong paraan, maaari nating ipakita na ang mental health ay isa sa pinakamahalagang aspekto ng ating buhay, at dapat itong bigyan ng sapat na pansin at pag-aaruga.

Sa panahon ng pandemya, ang buong mundo ay nabalot ng kawalan ng katiyakan, takot, at pag-aalala. Ang krisis na dala ng COVID-19 ay hindi lamang nagdulot ng sakit sa katawan, kundi pati na rin sa ating kaisipan. Ang sanaysay na ito ay tatalakay sa epekto ng pandemya sa mental health ng bawat isa, at ang mga paraan kung paano tayo makakabangon mula sa krisis na ito.

Ang pandemya ay nagdulot ng maraming pagbabago sa ating pang-araw-araw na buhay. Ito ay nagsimula sa pagpapatupad ng lockdowns at community quarantines, na nagdulot ng kawalan ng trabaho, pagkawala ng kita, at pagbabago sa ating mga gawain. Ang mga ito ay may malaking epekto sa ating mental health, dahil marami sa atin ang nakaranas ng stress, kawalan ng pag-asa, at pangamba sa hinaharap.

Isa sa mga pangunahing epekto ng pandemya sa mental health ay ang pagtaas ng anxiety at depression. Ang kawalan ng pagkakataong makalabas at makipag-ugnayan sa ibang tao ay maaaring maging sanhi ng kalungkutan, pagkawala ng interes sa dating mga hilig, at pagkakaroon ng negatibong pananaw sa buhay. Dagdag pa rito, ang stress na dala ng pagkawala ng trabaho at pagkakaroon ng financial problems ay nagdulot ng pagkabalisa sa marami sa atin.

Bukod pa rito, ang pandemya ay nagdulot din ng mga social issues na may epekto sa mental health, tulad ng domestic violence, child abuse, at pagkalulong sa droga o alak. Ang mga ito ay maaaring magdulot ng long-term psychological effects sa mga biktima at kanilang mga pamilya.

Sa kabila ng mga negatibong epekto ng pandemya sa mental health, mayroon din tayong mga paraan upang labanan ang mga ito at makabangon mula sa krisis na ito:

- Magkaroon ng regular na komunikasyon sa pamilya at mga kaibigan. Ang pag-uusap sa mga taong mahalaga sa atin ay maaaring makatulong upang maibsan ang ating kawalan ng pag-asa at kalungkutan.

- Magtakda ng mga bagong routines o goal. Ang pagkakaroon ng bagong layunin sa buhay ay maaaring makatulong upang mabigyan tayo ng bagong pag-asa at maging mas produktibo sa panahon ng pandemya.

- Maging aktibo sa pamamagitan ng pag-eehersisyo at pagkain ng masustansya. Ang malusog na pamumuhay ay maaaring makatulong upang mapabuti ang ating mental health at maging handa sa mga hamon na dala ng pandemya.

- Huwag matakot humingi ng tulong. Kung nakakaranas tayo ng labis na pagkabalisa, depression, o anumang problema sa ating mental health, mahalaga na humingi tayo ng tulong mula sa mga eksperto o mental health professionals. Ito ay isang mahalagang hakbang upang malunasan ang ating mga problema at maging mas malakas na tao pagkatapos ng pandemya.

- Mag-aral ng stress management techniques. Ang pag-aaral ng iba’t ibang paraan upang kontrolin ang stress, tulad ng deep breathing exercises, mindfulness meditation, at relaxation techniques ay maaaring makatulong upang mabawasan ang epekto ng pandemya sa ating mental health.

Sa pagtatapos, ang pandemya ay tunay na nagdulot ng maraming hamon at pagsubok sa ating buhay, lalo na sa ating mental health. Ngunit sa pamamagitan ng pagkakaisa at pagtutulungan, maaari nating labanan ang mga epekto ng krisis na ito at makabangon muli bilang mas malakas at mas handang tao sa hinaharap. Ang pagpapahalaga sa ating mental health at pagbibigay-suporta sa isa’t isa ay magiging susi upang malagpasan natin ang pandemya at makamit ang ating mga pangarap at layunin sa buhay.

Sa ating makulay at masalimuot na buhay, madalas ay nakakalimutan natin ang isang aspekto na napakahalaga sa ating pag-unlad at kasiyahan – ang mental health. Ito ang kalagayan ng ating kaisipan at emosyon na may malaking impluwensya sa ating pang-araw-araw na buhay. Sa sanaysay na ito, ating tatalakayin ang kahalagahan ng mental health sa bawat isa, sa ating komunidad, at sa ating lipunan.

Una, ang mental health ay mahalaga sa ating personal na buhay. Ito ay nagsisilbing pundasyon kung paano natin haharapin ang mga hamon, pagsubok, at oportunidad na dumarating sa atin. Ang pagkakaroon ng maayos na mental health ay nagbibigay-daan sa atin upang magkaroon ng mas malinaw na pag-iisip, maging mas maayos na gumawa ng mga desisyon, at maging mas epektibo sa pakikipag-ugnayan sa ating mga mahal sa buhay at kaibigan.

Ikalawa, ang mental health ay mahalaga sa ating mga relasyon. Ang maayos na mental health ay nagpapabuti sa ating emosyonal na katalinuhan na makatutulong sa atin na mas maunawaan at maging sensitibo sa damdamin ng iba. Ito ay nagpapalakas din sa ating abilidad na makipag-ugnayan sa ibang tao, magkaroon ng mas malalim na koneksyon, at maging mas responsableng miyembro ng pamilya at ng komunidad.

Ikatlo, ang mental health ay mahalaga sa ating propesyon o trabaho. Ang pagkakaroon ng maayos na mental health ay maaaring magresulta na maging mas produktibo, magkaroon ng mas mababang antas ng stress, at makaranas ng mas malaking kasiyahan sa ating ginagawa. Ito ay nagdudulot din ng mas malaking kakayahan na harapin ang stress at presyon sa trabaho, at maging mas malikhaing problem-solver.

Pang-apat, ang mental health ay mahalaga sa ating lipunan. Ang pagkakaroon ng malusog na mental health ay maaaring makatulong upang mabawasan ang insidente ng kriminalidad, domestic violence, at iba pang mga negatibong pag-uugali na maaaring makaapekto sa ating komunidad. Ito ay nakatutulong din upang mapalakas ang pagkakaisa, pagtutulungan, at pag-aaruga sa isa’t isa.

Sa ating pagkilala sa kahalagahan ng mental health, nararapat lamang na bigyan ito ng sapat na pansin at pag-aaruga. Ang pagpapahalaga sa mental health ay nangangahulugan ng pagtanggap sa ating mga emosyon, pag-aaral ng mga paraan upang mapabuti ang ating kaisipan, at pagbibigay ng suporta at pagmamahal sa mga taong nakakaranas ng mga mental health challenges.

Sa pagtatapos, ang mental health ay isang aspeto ng ating buhay na dapat nating bigyan ng sapat na halaga at pag-aaruga. Ang pagpapahalaga sa mental health ay isa sa mga susi upang maging mas malusog, mas masaya, at mas matagumpay na indibidwal. Sa pamamagitan ng pag-aalaga sa ating mental health, maaari nating ipakita ang ating pagmamahal sa ating sarili, sa ating pamilya, at sa ating komunidad. Sa ganitong paraan, maaari tayong makamit ang isang mas malusog at mas makabuluhang buhay.

Sa ating lipunan ngayon, ang kabataan ay patuloy na humaharap sa maraming pagsubok at hamon na dala ng pagbabago sa ating mundo. Ang “Bagong Normal” na dulot ng pandemya, teknolohiya, at iba pang mga pagbabago ay nagdulot ng malaking epekto sa mental health ng mga kabataan. Sa sanaysay na ito, tatalakayin natin ang kalagayan ng mental health ng kabataan sa Bagong Normal at ang mga hakbang na maaari nating gawin upang suportahan ang kanilang paglago at pag-unlad.

Sa panahon ng pandemya, ang kabataan ay dumanas ng mga pagbabago sa kanilang pamumuhay na maaaring magdulot ng stress at pagkabalisa. Ang pagpapatupad ng online learning ay isa sa mga pagbabagong ito, na nagdulot ng labis na presyon sa mga estudyante na masanay sa bagong paraan ng pag-aaral, gumamit ng teknolohiya sa kabila na hindi lahat ay may maayos na access dito, at balansehin ang kanilang mga tungkulin sa tahanan.

Bukod sa mga pag-aaral, ang pagkakaroon ng limited na social interaction dahil sa mga quarantine measures ay nagdulot ng pagkakahiwalay at pagkakalayo sa kanilang mga kaibigan at kamag-aral. Ang kawalan ng face-to-face na pakikipag-ugnayan ay maaaring magdulot ng pakiramdam ng kalungkutan, pagkawala ng koneksyon, at pagkakaroon ng higit na pagkabalisa.

Sa kabilang banda, ang pag-usbong ng teknolohiya at social media ay nagdulot ng maraming pagkakataon para sa mga kabataan na manatiling konektado at makibahagi sa iba’t ibang aktibidad. Gayunpaman, ang labis na paggamit ng social media at internet ay maaaring magdulot ng mga negatibong epekto sa kanilang mental health. Ang peer pressure, cyberbullying, at pagkukumpara sa buhay ng iba ay maaaring maging sanhi ng depresyon, mababang self-esteem, at iba pang mga mental health issues.

Upang masuportahan ang mental health ng kabataan sa Bagong Normal, narito ang ilang mga hakbang na maaari nating gawin:

- Palakasin ang komunikasyon: Ang pakikipag-usap sa mga kabataan tungkol sa kanilang mga problema, emosyon, at nararamdaman ay maaaring makatulong upang maunawaan natin ang kanilang mga kailangan at maging mas handa sa pagbibigay ng tulong.

- Magbigay ng suporta sa kanilang pag-aaral: Hikayatin ang mga kabataan na balansehin ang kanilang akademiko at personal na buhay, at magbigay ng patnubay at suporta habang sila ay umaangkop sa mga bagong pamamaraan ng pag-aaral, tulad ng online class.

- Itaguyod ang mga malusog na gawi: Hikayatin ang mga kabataan na magkaroon ng malusog na pamumuhay, tulad ng pagkain ng masustansyang pagkain, pagkakaroon ng sapat na pahinga at tulog, at pagsasagawa ng regular na ehersisyo. Ang mga malusog na gawi ay maaaring makatulong sa pagpapanatili ng kanilang mental health at pangkalahatang kalusugan.

- Limitahan ang oras sa social media at internet: Magbigay ng gabay sa mga kabataan sa tamang paggamit ng social media at teknolohiya. Itakda ang oras sa paggamit ng internet at mag-encourage na gumugol ng oras sa ibang aktibidad tulad ng sports, hobbies, at pagkakaroon ng face-to-face na pakikipag-ugnayan sa pamilya at kaibigan kapag posible.

- Huwag balewalain ang mga senyales ng problema sa mental health: Kung may ipinapakitang senyales ang mga kabataan ng mga mental health issues tulad ng pagkabalisa, depresyon, o anumang pagbabago sa kanilang pag-uugali, maghanap ng propesyonal na tulong mula sa mental health experts.

- Magbigay ng edukasyon tungkol sa mental health: Maging bukas sa pag-uusap tungkol sa mental health at ituro sa mga kabataan ang kahalagahan ng pag-aaruga sa kanilang sarili, pagtanggap ng tulong, at pagpapahalaga sa sarili at sa iba.

Sa pagtatapos, ang mental health ng kabataan sa Bagong Normal ay nangangailangan ng ating patuloy na suporta at pang-unawa. Ang pagkilala sa mga hamon na dala ng pandemya, teknolohiya, at iba pang mga pagbabago ay mahalaga upang mabigyan natin sila ng sapat na gabay at tulong sa pagharap sa mga pagsubok na ito. Sa pamamagitan ng pagpapahalaga sa kanilang mental health at pagbibigay ng suporta sa kanilang paglago at pag-unlad, maaari nating matulungan ang mga kabataan na maging mas malakas, mas masaya, at mas handang harapin ang kinabukasan.

Ang pandemya na dulot ng COVID-19 ay hindi lamang isang krisis sa kalusugan, ngunit isa rin itong malawakang krisis sa mental health na may malalim na epekto sa ating lipunan, lalo na sa mga kabataan. Ang paglisan mula sa kanilang nakasanayang pamumuhay, pagkawala ng mga oportunidad sa pag-aaral at pakikisalamuha, at ang biglaang pagbabago sa kanilang pang-araw-araw na gawain ay nagdudulot ng malalaking hamon sa kanilang mental health. Sa sanaysay na ito, tatalakayin natin ang mga epekto ng pandemya sa mental health ng mga kabataan.

Una, ang pandemya ay nagdulot ng matinding pagkabalisa at stress sa mga kabataan. Ang takot sa pagkakasakit, ang kawalan ng kasiguruhan sa kinabukasan, at ang mga pangamba sa kanilang pamilya at kaibigan ay lumikha ng isang sitwasyon kung saan ang kanilang mental health ay maaaring maapektuhan. Ang labis na stress at pagkabalisa ay maaaring magdulot ng iba pang mga problema sa mental health, tulad ng depresyon, sleep disturbances, at mababang self-esteem.

Pangalawa, ang pagpapatupad ng mga quarantine measures at ang paglilipat sa online learning ay nagresulta sa limitadong social interaction para sa mga kabataan. Ang kawalan ng pisikal na pakikipag-ugnayan sa mga kamag-aral, guro, at kaibigan ay maaaring magdulot ng pakiramdam ng kalungkutan, pagkakahiwalay, at pagkawala ng koneksyon sa ibang tao. Ito ay maaaring maging sanhi ng pagtaas ng mga kaso ng depresyon at anxiety disorders sa mga kabataan.

Pangatlo, ang pandemya ay nagdulot ng maraming pagkawala sa mga kabataan – mula sa pagkawala ng mga mahal sa buhay dahil sa COVID-19, hanggang sa pagkawala ng mga oportunidad sa pag-aaral at pag-unlad. Ang mga ito ay maaaring maging sanhi ng pagdadalamhati, pagkalito, at mababang self-worth. Ang mga pagkawala ay maaaring pagmulan ng post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at iba pang mga mental health challenges.

Upang harapin ang mga epekto ng pandemya sa mental health ng mga kabataan, maaari nating gawin ang mga sumusunod na hakbang:

- Magsagawa ng mga mental health awareness campaigns upang bigyang-pansin ang kahalagahan ng mental health at hikayatin ang mga kabataan na humingi ng tulong kapag kailangan.

- Magbigay ng suporta at gabay sa mga kabataan sa pag-aaral sa online learning at iba pang mga pagbabago sa kanilang pamumuhay.

- Palakasin ang komunikasyon sa loob ng pamilya at magkaroon ng regular na pag-uusap tungkol sa kanilang mga damdamin, pangamba, at mga karanasan sa panahon ng pandemya.

- Hikayatin ang mga kabataan na makibahagi sa mga aktibidad na nakatutulong sa kanilang mental health, tulad ng ehersisyo, pagbibisikleta, o anumang aktibidad upang magkaroon ng malusog na pamumuhay.

- I-promote ang responsibleng paggamit ng social media at teknolohiya upang mabawasan ang negatibong epekto nito sa mental health ng mga kabataan.

- Makipagtulungan sa mga mental health professionals upang magbigay ng sapat na serbisyo at suporta sa mga kabataang nangangailangan ng tulong sa kanilang mental health.

- Magbigay ng mga peer support programs at counseling services sa mga paaralan at komunidad upang matulungan ang mga kabataan na harapin ang mga hamon na dala ng pandemya.

Sa pagtatapos, ang pandemya ay isang malaking pagsubok na humamon sa mental health ng mga kabataan. Ngunit sa tamang suporta, pag-unawa, at pag-aaruga mula sa ating mga pamilya, komunidad, at pamahalaan, maaari nating matulungan ang mga kabataan na malampasan ang mga epekto ng pandemya at maging mas matatag sa harap ng anumang pagsubok sa hinaharap. Ang pagsisikap na ito ay hindi lamang makakatulong sa mga kabataan na mabawi ang kanilang mental health, ngunit magbibigay rin ng mas malusog at masiglang lipunan para sa lahat.

Sa makabagong panahon, ang mental health ay isa sa mga mahahalagang aspeto ng buhay na nangangailangan ng mas malalim na pag-unawa, kamalayan, at suporta mula sa bawat isa sa atin. Ang paglago ng teknolohiya, ang mabilis na pagbabago ng lipunan, at ang mga hamon na dala ng pandemya ay nagbigay ng iba’t ibang epekto sa ating mental health. Sa sanaysay na ito, ating tatalakayin ang kahalagahan ng pag-unawa, kamalayan, at suporta sa mental health sa makabagong panahon.

Una, ang pag-unawa sa mental health ay napakahalaga upang mabigyan ng tamang atensyon ang mga pangangailangan ng bawat isa. Ang pag-unawa sa mga sintomas, sanhi, at epekto ng iba’t ibang mental health issues ay makakatulong sa atin na magbigay ng angkop na tulong at suporta sa mga taong nangangailangan. Ang pag-unawa rin sa mga limitasyon at kakayahan ng bawat isa ay magbibigay-daan sa paggalang at pagtanggap sa kanilang karanasan.

Pangalawa, ang kamalayan sa mental health ay nangangailangan ng ating pagiging aktibo sa pagtuklas at pagpapalawak ng kaalaman sa mga isyung pangkaisipan. Ang paglahok sa mga mental health awareness campaigns, pagbabasa ng mga artikulo, at pakikinig sa mga kwento at karanasan ng iba ay ilan lamang sa mga paraan upang madagdagan ang ating kaalaman. Ang kamalayan ay nag-uugat sa ating pagnanais na matuto at maging mas handa sa pagtugon sa mga hamon sa ating mental health.

Pangatlo, ang suporta sa mental health ay hindi lamang tungkol sa pagbibigay ng tulong sa mga nangangailangan, ngunit pati na rin sa pagpapakita ng malasakit sa kanilang karanasan. Ang suporta ay maaaring magsimula sa loob ng pamilya, kung saan ang pagiging bukas sa pag-uusap tungkol sa emosyon at damdamin ay mahalaga. Maaari rin itong maging bahagi ng komunidad at mga institusyon, sa pamamagitan ng pagbibigay ng mga programa at serbisyong pang-mental health na tutugon sa mga pangangailangan ng bawat isa.

Sa makabagong panahon, ang mental health ay hindi na dapat ituring na isang taboo o kahihiyang usapin. Sa halip, ito ay isang hamon na dapat nating harapin nang sama-sama, sa pamamagitan ng pag-unawa, kamalayan, at suporta. Ang pagsisikap na ito ay hindi lamang makakatulong sa ating sariling mental health, ngunit magbibigay rin ng mas malusog at masiglang lipunan para sa lahat.

Sa ating pang-araw-araw na buhay, maaari nating ipakita ang ating pag-unawa sa mental health sa pamamagitan ng pagiging sensitibo sa mga damdamin ng iba at pagpapahalaga sa kanilang mga karanasan. Maging handa rin tayong tumanggap ng tulong para sa ating sariling mental health, at huwag matakot na humingi ng suporta sa oras ng pangangailangan.

Sa huli, ang mental health sa makabagong panahon ay isang aspeto ng buhay na dapat nating pagtuunan ng pansin at pahalagahan. Ang pag-unawa sa mga karanasan ng iba, pagkakaroon ng kamalayan sa mga isyung pangkaisipan, at pagbibigay ng suporta ay tatlong mahahalagang hakbang upang makamit ang isang mas maunlad na lipunan na may malusog na kaisipan para sa lahat.

At ‘yan ang mga halimbawa ng sanaysay tungkol sa mental health. Inaasahan namin na ang mga sanaysay na ito ay nagbigay sa iyo ng bagong kaalaman, inspirasyon, at pag-asa na magagamit sa iyong sariling buhay at sa pagtulong sa iba.

Hinihikayat ka naming i-share ang mga sanaysay na ito sa iyong pamilya, mga kaibigan, at sa marami pang iba sa pamamagitan ng social media o anumang paraan na angkop sa iyo. Ang pagbabahagi ng kaalaman at kamalayan ay isang mahalagang hakbang upang mapalakas ang ating ugnayan sa isa’t isa at maitaguyod ang isang malusog at maunlad na lipunan.

Muli, maraming salamat sa pagbabasa ng mga sanaysay tungkol sa mental health. Maging mabuti nawa tayong tagapagdala ng pagbabago at pag-asa para sa ating sarili at sa ating kapwa.

You may also like:

TULA: Kahulugan, Elemento, Uri, at mga Halimbawa ng Tula

MAIKLING KWENTO: Uri, Elemento, Bahagi at Mga Halimbawa

ALAMAT: Kahulugan at Halimbawa ng mga Alamat

PABULA: Kahulugan, Elemento at Mga Halimbawa ng Pabula

EPIKO: Ano ang Epiko at mga Halimbawa Nito

Bugtong, Bugtong: 490+ Mga Halimbawa ng Bugtong na may Sagot

You may also like

- Pang-abay na Pananggi: Ano ang Pang-abay na Pananggi at mga Halimbawa nito

- El Filibusterismo Kabanata 8 Buod, Mga Tauhan, at Aral

- Pang-abay na Pamaraan: Ano ang Pang-abay na Pamaraan at mga Halimbawa nito

- Noli Me Tangere Kabanata 46 Buod, Mga Tauhan, at Aral

- El Filibusterismo Kabanata 28 Buod, Mga Tauhan, at Aral

- X (Twitter)

- More Networks

- Subscribe Now

[OPINYON] Kasama tayo sa laban para sa mental health

Already have Rappler+? Sign in to listen to groundbreaking journalism.

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![mental health essay tagalog [OPINYON] Kasama tayo sa laban para sa mental health](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/612F469A6EA84F6BAE882D2B94A4B421/img/C08A0D1DED1045F39DD190A1A6A603F5/thought-leaders.jpg)

Hindi lamang ito basta may kinalaman o konektado sa isip o pag-iisip kundi sa bahay-kalinga para sa mga baliw. Walang kapagurang biro ang kapag taga-Mandaluyong ka ay tatanungin ka kung sa “loob o sa labas.”

Pasaring lamang ito sa lugar na kinatatayuan ng National Center for Mental Health (NCMH).

O mas kilala bilang Mental.

Nagsimula bilang Insular Psychopathic Hospital, ito ay itinayo sa Kalye Nueve de Pebrero, Baryo Mauway, Mandaluyong, sa probinsiya ng Rizal noong Disyembre 17, 1928. Ito ang pinaglipatan ng mga pasyenteng galing sa “Insane Department” ng San Lazaro Hospital noong 1925 at ng City Sanitarium noong 1935.

Kumbaga, noon pa man, problema na rin ang pagdami ng may mga kapansanan sa pag-iisip. Sa kasalukuyan, ang NCMH ay nagsisilbi sa humigit-kumulang 4,000 pasyenteng naka-admit bawat araw at 56,000 konsultasyon kada taon. Ito ay mula sa NCMH lamang.

Ayon 2010 National Census, sa 1.4 milyong Filipinong may kapansanan, 14 porsiyento – o tinatayang 200,000 tao – ang tinatawag na may “mental disability.”

At paparami pa sila nang paparami.

Paano na sila? Silang kung bansagan ay “Abnoy,” “Agooyong,” “Brenda,” “Buang,” “Koala,” “Kulang-kulang,” “Gunggong,” “Luko-luko,” “Lukresia Kasilag,” “Maysayad,” “May Tililing,” “May Topak,” “Praning,” “Retarded,” “Sinto-sinto,” “Siraulo,” “Taong Grasa,” “Timang,” “Wazak,” o iba pang kabilang sa ikatlong pinakakaraniwang kapansanan sa buong bansa?

Sila ba ay ang may sikosis lamang? Kabilang ba rito ang mga nalulong sa alak o droga? Paano ang mga may matinding lungkot at takot? O ang mga nagsasalita nang mag-isa matapos silang salantain ng kalamidad? O ang mga nag-uulyanin? O ang mga bully at binu-bully? O ang mga nang-aabuso at inaabuso? O ang mga naa-adik sa computer games? O social media?

Kung salat na nga ba sila sa buhay, sapat na ba ang batas?

Mga panukala at batas

Marami ang naging pagtatangkang magkaroon ng mga panukalang-batas ukol sa lusog-isip, pero walang nakakapasa sa Senado at Kamara.

Una sa lahat ng panukalang-batas ay ang ipinasa si Senador Orlando Mercado na Mental Health Act of 1989. Ito sana ang magdedeklara ng isang pambansang patakaran ukol sa lusog-isip, magtatatag ng Board of Mental Health sa Kagawaran ng Kalusugan, at magsasama sa karamdaman sa isip sa saklaw ng Medicare.

Noong 1998, nabuo ang Executive Order 470 na lumikha sa Philippine Council for Mental Health. Diumano, hindi man lamang ito nakapagpulong.

Nagkaroon tayo ng National Mental Health Policy noong 2001 kung kailan ang dating Kalihim ng Kagawaran ng Kalusugan na si Dr. Manuel Dayrit ay bumuo ng maituturing na isang pambansang patakaran para sa lusog-isip.

Magpahanggang isalang ang An Act Establishing A National Mental Health Policy For The Purpose Of Enhancing The Delivery of Integrated Mental Health Services, Promoting And Protecting Persons Utilizing Psychiatric, Neurologic, And Psychosocial Health Services, Appropriating Funds Therefor, And Other Purposes.”

Noong Mayo 2, 2017, nakapasa sa Senado ang Philippine Mental Health Act of 2017 bilangSenate Bill 1354. Tinututukan nito ang pagsasanib sa pangkalahatang pangangalaga sa kalusugan, kasama ang serbisyong mental, neurolohikal, at sikososyal. Bagamat ang pangunahing awtor nito ay si Senador Risa Hontiveros, na tagapangulo ng komite sa kalusugan sa Senado, kasama niyang nagsulong ng bill sina Senador Loren Legarda, Juan Edgardo Angara, Paolo Benigno Aquino IV, Vicente Sotto III (na ngayon ay Senate President na), Antonio Trillanes IV, at Joel Villanueva.

Maituturing ding kapanalig sa Kamara ng mga Representante sina Teddy Baguilat, Edward Maceda, Pia Cayetano, Karlo Nograles, Romero Quimbo, Chiqui Roa-Puno, Ron Salo, Yul Servo, Tom Villarin, Linabelle Villarica, at Isagani Zarate.

Ngayon, sana makatulong din ito sa tuloy-tuloy na pagiging positibo ng dati-rating negatibong tingin sa mental.

Nitong 21 Hunyo – noong International Day of Yoga mismo – pinirmahan ni President Rodrigo Duterte ang Republic Act 11036, mas kilala bilang Philippine Mental Health Law of 2018, na naglalayong ipagtanggol, itaguyod, at itaas ang antas ng lusog-isip – para mapabuti pa ang pagkakaloob ng kalinga para sa lusog-isip.

Ano ang lusog-isip?

Teka, ano nga ba itong paulit-ulit na lusog-isip?

Mas kilala sa Ingles bilang “mental health,” ang lusog-isip ay ang estado ng kaginhawahan ng tàong: (a) mulàt sa kaniyang sariling kakayahan, (b) nakakayang harapin ang pangkaraniwang hamon ng buhay, (c) kapaki-pakinabang, at (d) nakakatulong sa pamayanan.

Ano’t ano man, nariyan pa rin ang suliranin.

Bagamat kinikilala ang malaking papel ng pamahalaan, dapat nating bigyang-diin ang sama-samang tungkulin. Ito ay ang bayanihan ng lahat ng may kinalaman sa pangkalahatang kalusugan ng sambayanan.

Tinatayang may isang psychiatrist lamang sa bawat 200,000 Filipino. Kaya kailangang-kailangan pa rin ang tulong ng mga relihiyoso pati ng mga sikologo at iba pang kung tawagin ay mental health worker.

Halimbawa, noong dumagsa ang mga sakuna, tulad ng Yolanda at iba pa, ipinaloob ng World Health Organization (WHO) at Kagawaran ng Kalusugan ang lusog-isip sa pangunahing pangangailangang pang-kalusugan bilang bahagi ng rehabilitasyon.

Sa pamamagitan ng Mental Health Gap Action Program (mhGAP) na ito, sinanay ang mga doktor, nars, komadrona, at barangay health workers (BHW) na maisulong ang karapatan ng mga may karamdaman sa isip sa pamamagitan ng pagbibigay ng agarang serbisyong pangkalusugan.

Ipinagpapatuloy ito hanggang ngayon. Dahil dito, dumami ang mga doktor mula sa rural health units ang nagkukusang tumingin sa mga problema sa lusog-isip.

Pinalalakas na rin ang sistema upang maging regular ang rasyon ng gamot para sa kanila. Wala na itong ipinagkaiba sa mga suplay ng lunas para sa altapresyon, diabetes, impeksiyon, at iba pang pangkaraniwang sakit.

Pagkilos para sa mental health

Sa kasalukuyan, kaliwa’t kanan ang mga pulong ng iba’t ibang sektor ng lipunan para tiyakin ang tamang pagpapatupad ng naturang RA 11036.

Kasama rin tayo sa labang ito.

Ano’ng magagawa mo?

Simulan natin sa ating sarili.

Kung araw-araw nagagawa nating magsepilyo o magkaroon ng dental hygiene, bakit hindi natin gawin ang ating mental hygiene?

Ito ang agham ng pananatili ng lusog-isip na naging isang interdisiplaryong larangan na yumayakap sa sikolohiya, narsing, gawaing panlipunan, batas, at iba pang propesyon. Kabilang dito ay ang pagkakaroon ng malusog na asal upang maiwasan ang karamdamang mental.

Una, sanaying maging positibo. Matutong magpasalamat.

Ikalawa, kontrolin ang emosyon. Ipahayag ang damdamin mo sa tamang paraan.

Ikatlo, labanan ang istres. Panatilihin ang pangkalahatang kalusugan.

Malalagom natin ang mga prinsipyo ng pagkilos sa tulong ng tatlong T: (a) tuon; (b) tukoy; (c) tugon.

Tuunan natin ng pansin ang lusog-isip.

Tukuyuin natin ang mga nangangailangan ng tulong.

Tugunan natin ang mga pangangailangan nila.

Upang di-malimutan, mangyaring tandaan ang tulang ito:

Lusog-isip ay isipin At pagtuunan ng pansin. Karamdaman ay tukuyin, Tugunan ang suliranin!

– Rappler.com

Ang TOYM Awardee for Literature na si Vim Nadera ay nagtapos ng BS at MA Psychology sa University of Santo Tomas at ng PhD Philippine Studies sa University of the Philippines. Bilang performance art therapist, siya ay nakatulong na sa mga maykanser, may AIDS, nagdodroga, “comfort women,” batang kalye, inabuso, naipit sa mga kalamidad na likas at likha ng tao, at mga nagdadalamhati.

Add a comment

Please abide by Rappler's commenting guidelines .

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.

How does this make you feel?

Related Topics

Recommended stories, {{ item.sitename }}, {{ item.title }}.

Checking your Rappler+ subscription...

Upgrade to Rappler+ for exclusive content and unlimited access.

Why is it important to subscribe? Learn more

You are subscribed to Rappler+

- Language Basics

- Advanced Grammar Topics

- Conversational Use

- Language & Culture

- Learning Resources

- Privacy Policy

Discussing Mental Health and Well-being in Filipino

- by Amiel Pineda

- January 21, 2024 February 26, 2024

Discussing mental health in Filipino supports children’s growth and creates a welcoming space for all ages. It improves emotional well-being, fosters open dialogue, and offers resources against stigma.

Key Takeaways

- Mental health stigma and cultural perspectives significantly impact how individuals in the Filipino community think about and address mental health concerns.

- Family and community support play a crucial role in promoting understanding and providing practical assistance for individuals facing mental health challenges.

- Barriers to seeking mental health help in the Filipino community include stigma, lack of awareness, financial constraints, and fear of judgment or losing independence.

- Promoting mental health awareness in the Filipino community involves recognizing and addressing stigma, providing access to resources and support, and fostering open conversations.

Understanding Mental Health Stigma

Understanding mental health stigma is crucial for creating a supportive environment for individuals with mental health issues. Stigma can have detrimental effects on individuals’ social well-being and prevent them from seeking help for their mental health problems. It’s important to recognize that mental health is just as important as physical health.

By educating ourselves and engaging in open conversations, we can challenge these negative attitudes and promote acceptance. Advocacy, support, and understanding are essential in combating mental health stigma.

Filipino Cultural Perspectives on Mental Health

Shifting the focus from understanding mental health stigma, it’s essential to acknowledge the diverse cultural perspectives on mental health within Filipino communities.

Cultural perspectives on mental health significantly affect how individuals think about, relate to others, and address mental health concerns. These perspectives vary widely and can be influenced by cultural beliefs, practices, and values.

Stigma, family dynamics, and community acceptance also play significant roles in shaping these perspectives. Traditional healing practices, spirituality, and community support systems are integral to mental health care within specific cultural contexts.

Understanding these cultural perspectives is crucial for providing effective and inclusive support and promoting overall well-being. By recognizing and respecting the diverse cultural viewpoints on mental health, we can create more relevant and sensitive approaches to addressing mental health within Filipino communities.

Impact of Family and Community Support

Family and community support significantly impact an individual’s mental health and overall well-being by providing a sense of belonging and understanding, reducing feelings of isolation and loneliness. Such support helps determine the nurturing environment one is surrounded by, promoting open communication and understanding of mental health challenges. It aids in reducing stigma around mental health, encouraging seeking professional help and treatment.

Engaging with family and community support can provide practical assistance, such as help with daily tasks or emotional support during difficult times. This kind of support is crucial as it can greatly influence one’s mental well-being, creating a network of care and understanding that’s essential for overall health.

Barriers to Seeking Mental Health Help

Feeling the impact of family and community support is essential, but when it comes to seeking mental health help, various barriers can stand in the way. These barriers include stigma and fear of judgment, influenced by cultural beliefs and attitudes towards mental health.

Additionally, lack of awareness or understanding of mental health conditions can prevent people from seeking help. Financial constraints and limited access to mental health services also hinder seeking help.

Lastly, the fear of being perceived as weak or losing independence can discourage individuals from seeking mental health help.

Overcoming these barriers is crucial for fostering a supportive environment where individuals feel comfortable seeking the help they need.

Promoting Mental Health Awareness

You need to recognize the stigma surrounding mental health in society and understand how it affects individuals seeking help.

Access to mental health resources and support is crucial to promoting awareness and providing assistance to those in need.

It’s important to address these points to encourage open conversations and create a supportive environment for mental health.

Stigma in Society

Combatting societal stigma surrounding mental health is essential for promoting awareness and fostering open conversations. Stigma in society can hinder individuals from seeking help for mental health issues. Promoting mental health awareness helps combat stigma and encourages open conversations.

Education and understanding can help break down stigmas surrounding mental health conditions. Advocating for mental health support and resources can reduce societal stigma. Empowering individuals to seek help and support for their mental health promotes a stigma-free society.

Access to Resources

To promote mental health awareness effectively, it’s crucial to ensure access to resources such as crisis hotlines, treatment facilities, and support organizations. Encouraging individuals to seek help and support for mental health conditions is vital.

Providing crisis helpline numbers and available support services can make a significant difference. Emphasizing the importance of seeking help for mental health can help reduce stigma and encourage open conversations about mental well-being.

It’s essential to highlight the availability of resources such as SAMHSA, National Helpline, and Crisis Text Line for individuals to access mental health support and treatment. By urging individuals to prioritize their mental health and seek help when needed, we can support them in leading a healthier and happier life.

Importance of Well-being Practices

You deserve to prioritize your well-being practices, as they’re crucial for maintaining your mental health and overall happiness.

Engaging in self-care techniques, stress management tips, and seeking psychological support resources can help reduce stress and enhance your quality of life.

Self-Care Techniques

Engaging in self-care techniques is essential for maintaining your mental and emotional well-being. Prioritizing self-care can significantly impact your overall mental health and resilience. Here are key self-care practices to consider:

- Mindfulness : Cultivating mindfulness through meditation or conscious breathing can help reduce stress and enhance emotional regulation.

- Exercise : Regular physical activity not only benefits your physical health but also contributes to improved mood and reduced anxiety.

- Relaxation techniques : Incorporating relaxation methods such as deep breathing exercises or progressive muscle relaxation can aid in stress management and promote a sense of calm.

Stress Management Tips

Establishing healthy boundaries and learning to say no to excessive commitments are essential for effectively managing stress and prioritizing your well-being. Practice mindfulness and relaxation techniques to reduce stress and anxiety.

Engage in regular physical activity to boost your mood and improve overall well-being. Prioritize self-care activities such as hobbies, socializing, and adequate rest. Remember to seek professional help or support from loved ones when feeling overwhelmed.

Psychological Support Resources

Well-being practices such as stress management, healthy eating, exercise, and sleep play a crucial role in maintaining optimal mental health. It’s essential to embrace these practices and seek additional psychological support resources for a balanced well-being.

Here’s what you need to know:

- Developing healthy coping skills can improve resilience and contribute to better mental health outcomes.

- Seeking treatment for mental health is as important as seeking treatment for physical health.

- Encouraging individuals to talk about mental health openly reduces stigma and encourages support.

Integrating Filipino Traditional Healing Methods

Incorporating traditional healing methods into modern mental health practices can enhance the cultural relevance and holistic approach to mental well-being in the Filipino community. Traditional healing methods, such as herbal remedies, rituals, storytelling, and community ceremonies, can complement Western therapies and offer alternative perspectives on mental health.

Indigenous healers, known as albularyo or manghihilot, bring valuable insights and holistic approaches to mental well-being. Integrating these traditional healing methods acknowledges the spiritual and cultural significance in mental health care, providing a more comprehensive and inclusive support system.

Mental Health Resources in the Filipino Community

You may encounter mental health stigma and cultural barriers that can make it difficult to seek care in the Filipino community.

Accessing support services tailored to the unique experiences of Filipinos is crucial in addressing these challenges.

Understanding the available resources and knowing where to turn for culturally competent care can make a significant difference in your mental well-being.

Filipino Mental Health Stigma

Amidst the stigma surrounding mental health in the Filipino community, numerous resources are available to provide support and assistance. You can find help and understanding through organizations like the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and the Filipino Mental Health Initiative.

These resources offer culturally competent care and aim to address the unique cultural and language needs of the Filipino community . Additionally, there’s a growing awareness and advocacy within the community to combat mental health stigma, leading to the establishment of tailored mental health support groups and counseling services.

Efforts are being made to educate and empower the Filipino community to prioritize mental health and seek help without fear of judgment. You aren’t alone in this journey, and there are resources specifically designed to support you.

Cultural Barriers to Care

Cultural stigma and traditional beliefs present significant barriers to accessing mental health resources within the Filipino community.

The stigma surrounding mental health can make it difficult for Filipinos to seek professional help. Traditional beliefs and practices may clash with Western mental health approaches, hindering access to care.

The family-oriented culture often leads to reluctance in discussing personal struggles outside the family circle, further isolating individuals in need. Moreover, limited awareness and access to mental health resources within the Filipino community exacerbate the issue.

Language barriers also play a role, impeding effective communication with mental health professionals.

Addressing these cultural barriers is crucial in ensuring that Filipinos can access the support and resources they need for their mental well-being.

Access to Support Services

Accessing mental health resources and support services within the Filipino community is crucial for promoting well-being and addressing mental health concerns.

You have access to crisis hotlines like 988 and support websites like FindSupport.gov for immediate help. Additionally, SAMHSA’s National Helpline (800-662-HELP) can assist you in locating treatment facilities or providers.

Seeking help for mental health is important, and there are resources and support available in the Filipino community. Encouraging open conversations about mental health and the importance of seeking help can lead to a healthier and happier life.

Addressing Mental Health in Educational Settings

In creating a supportive and inclusive environment, educators can significantly impact students’ mental health and well-being in educational settings. By fostering a culture of understanding and empathy, educators play a crucial role in addressing mental health.

Implementing mental health education programs and raising awareness can help reduce stigma and promote a better understanding of mental health issues.

Providing access to mental health resources within educational institutions is essential for addressing students’ mental health needs.

Collaborating with mental health professionals and families is key to effectively addressing mental health in educational settings.

Together, we can create a nurturing environment where students feel supported and understood, ultimately contributing to their overall well-being and success in school.

Nurturing a Supportive Environment

Creating a nurturing environment fosters a sense of belonging and support for individuals struggling with mental health concerns. To achieve this, encourage open conversations about mental health to create a safe and supportive space. Offer empathy, understanding, and validation to those facing mental health challenges, showing them that they aren’t alone.

Promote positive and healthy coping mechanisms within your social circles, fostering an atmosphere of mutual care and support. By creating an environment where seeking professional help is encouraged and supported, you can ensure that individuals feel empowered to take the necessary steps towards their mental well-being.

Educate yourself and others about mental health to reduce stigma and increase awareness, ultimately fostering a supportive community where everyone feels understood and accepted.

Frequently Asked Questions

How would you explain mental health and wellness.

You explain mental health and wellness by understanding that it encompasses emotional, psychological, and social well-being, impacting how you think, feel, and behave. Developing healthy coping skills and seeking support are crucial for overall well-being.

How to Explain the Relationship Between Mental Health and Well-Being?

To explain the relationship between mental health and well-being, you need to understand that they’re intertwined. Your mental health affects your overall well-being, influencing your emotions, thoughts, and behavior, and vice versa.

What Is Emotional Well-Being and Mental Health in English?

Emotional well-being and mental health encompass your emotional, psychological, and social wellness. It affects how you think, feel, and behave at every stage of life. Seeking support and developing healthy coping skills can improve outcomes.

What Mental Health and Well-Being Means?

Understanding mental health and well-being means prioritizing your emotional, psychological, and social wellness. Recognizing warning signs and seeking help when needed is crucial. Investing in your mental health is as important as investing in your physical health for a fulfilling life.

How Can Discussing Mental Health and Well-being in Filipino Benefit Children’s Development?

Discussing mental health and well-being in Filipino can benefit children’s development by creating a supportive environment that promotes open communication and understanding. Introducing lullabies and nursery rhymes Filipino can help in soothing and calming children, improving their emotional well-being and overall development.

So, if you’re struggling with mental health, remember that seeking help is okay. Your community and family can be a source of support, and there are resources available to you.

Don’t let stigma or cultural barriers stop you from taking care of your well-being. It’s important to promote awareness and create a nurturing environment for mental health in the Filipino community.

You deserve to prioritize your mental health and seek the help you need.

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

Filipinos face the mental toll of the Covid-19 pandemic — a photo essay

Share this:.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

BY ORANGE OMENGAN

Depression, anxiety, and other mental health-related illnesses are on the rise among millennials as they face the pressure to be functional amidst pandemic fatigue. Omengan's photo essay shows three of the many stories of mental health battles, of struggling to stay afloat despite the inaccessibility of proper mental health services, which worsened due to the series of lockdowns in the Philippines.

“I was just starting with my new job, but the pandemic triggered much anxiety causing me to abandon my apartment in Pasig and move back to our family home in Mabalacat, Pampanga.”

This was Mano Dela Cruz's quick response to the initial round of lockdowns that swept the nation in March 2020.

Anxiety crept up on Mano, who was diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder Type II with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder traits. The 30-year-old writer is just one of many Filipinos experiencing the mental health fallout of the pandemic.

Covid-19 infections in the Philippines have reached 1,149,925 cases as of May 17. The pandemic is unfolding simultaneously with the growing number of Filipinos suffering from mental health issues. At least 3.6 million Filipinos suffer from mental, neurological, and substance use disorders, according to Frances Prescila Cuevas, head of the National Mental Health Program under the Department of Health.

As the situation overwhelmed him, Mano had to let go of his full-time job. “At the start of the year, I thought I had my life all together, but this pandemic caused great mental stress on me, disrupting my routine and cutting my source of income,” he said.

Mano has also found it difficult to stay on track with his medications. “I don’t have insurance, and I do not save much due to my medical expenses and psychiatric consultations. On a monthly average, my meds cost about P2,800. With my PWD (person with disability) card, I get to avail myself of the 20% discount, but it's still expensive. On top of this, I pay for psychiatric consultations costing P1,500 per session. During the pandemic, the rate increased to P2,500 per session lasting only 30 minutes due to health and safety protocols.”

The pandemic has resulted in substantial job losses as some businesses shut down, while the rest of the workforce adjusted to the new norm of working from home.

Ryan Baldonado, 30, works as an assistant human resource manager in a business process outsourcing company. The pressure from work, coupled with stress and anxiety amid the community quarantine, took a toll on his mental health.

Before the pandemic, Ryan said he usually slept for 30 hours straight, often felt under the weather, and at times subjected himself to self-harm. “Although the symptoms of depression have been manifesting in me through the years, due to financial concerns, I haven't been clinically diagnosed. I've been trying my best to be functional since I'm the eldest, and a lot is expected from me,” he said.

As extended lockdowns put further strain on his mental health, Ryan mustered the courage to try his company's online employee counseling service. “The free online therapy with a psychologist lasted for six months, and it helped me address those issues interfering with my productivity at work,” he said.

He was often told by family or friends: “Ano ka ba? Dapat mas alam mo na ‘yan. Psych graduate ka pa man din!” (As a psych graduate, you should know better!)

Ryan said such comments pressured him to act normally. But having a degree in psychology did not make one mentally bulletproof, and he was reminded of this every time he engaged in self-harming behavior and suicidal thoughts, he said.

“Having a degree in psychology doesn't save you from depression,” he said.

Depression and anxiety are on the rise among millennials as they face the pressure to perform and be functional amid pandemic fatigue.

Karla Longjas, 27, is a freelance artist who was initially diagnosed with major depression in 2017. She could go a long time without eating, but not without smoking or drinking. At times, she would cut herself as a way to release suppressed emotions. Karla's mental health condition caused her to get hospitalized twice, and she was diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder in 2019.

“One of the essentials I had to secure during the onset of the lockdown was my medication, for fear of running out,” Karla shared.

With her family's support, Karla can afford mental health care.

She has been spending an average of P10,000 a month on medication and professional fees for a psychologist and a psychiatrist. “The frequency of therapy depends on one's needs, and, at times, it involves two to three sessions a month,” she added.

Amid the restrictions of the pandemic, Karla said her mental health was getting out of hand. “I feel like things are getting even crazier, and I still resort to online therapy with my psychiatrist,” she said.

“I've been under medication for almost four years now with various psychologists and psychiatrists. I'm already tired of constantly searching and learning about my condition. Knowing that this mental health illness doesn't get cured but only gets manageable is wearing me out,” she added. In the face of renewed lockdowns, rising cases of anxiety, depression, and suicide, among others, are only bound to spark increased demand for mental health services.

MANO DELA CRUZ

Writer Mano Dela Cruz, 30, is shown sharing stories of his manic episodes, describing the experience as being on ‘top of the world.’ Individuals diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder Type II suffer more often from episodes of depression than hypomania. Depressive periods, ‘the lows,’ translate to feelings of guilt, loss of pleasure, low energy, and thoughts of suicide.

Mano says the mess in his room indicates his disposition, whether he's in a manic or depressive state. “I know that I'm not stable when I look at my room and it's too cluttered. There are days when I don't have the energy to clean up and even take a bath,” he says.

Mano was diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder Type II in 2016, when he was in his mid-20s. His condition comes with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder traits, requiring lifelong treatment with antipsychotics and mood stabilizers such as antidepressants.

Mano resorts to biking as a form of exercise and to release feel-good endorphins, which helps combat depression, according to his psychiatrist.

Mano waits for his psychiatric consultation at a hospital in Angeles, Pampanga.

Mano shares a laugh with his sister inside their home. “It took a while for my family to understand my mental health illness,” he says. It took the same time for him to accept his condition.

RYAN BALDONADO

Ryan Baldonado, 30, shares his mental health condition in an online interview. Ryan is in quarantine after experiencing symptoms of Covid-19.

KARLA LONGJAS

Karla Longjas, 27, does a headstand during meditative yoga inside her room, which is filled with bottles of alcohol. Apart from her medications, she practices yoga to have mental clarity, calmness, and stress relief.

Karla shares that in some days, she has hallucinations and tries to sketch them.

In April 2019, Karla was inflicting harm on herself, leading to her two-week hospitalization as advised by her psychiatrist. In the same year, she was diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder. The stigma around her mental illness made her feel so uncomfortable that she had to use a fake name to hide her identity.

Karla buys her prescriptive medications in a drug store. Individuals clinically diagnosed with a psychosocial disability can avail themselves of the 20% discount for persons with disabilities.

Karla Longjas is photographed at her apartment in Makati. Individuals diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) exhibit symptoms such as self-harm, unstable relationships, intense anger, and impulsive or self-destructive behavior. BPD is a dissociative disorder that is not commonly diagnosed in the Philippines.

This story is one of the twelve photo essays produced under the Capturing Human Rights fellowship program, a seminar and mentoring project

organized by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism and the Photojournalists' Center of the Philippines.

Check the other photo essays here.

Larry Monserate Piojo – “Terminal: The constant agony of commuting amid the pandemic”

Orange Omengan – “Filipinos face the mental toll of the Covid-19 pandemic”

Lauren Alimondo – “In loving memory”

Gerimara Manuel – “Pinagtatagpi-tagpi: Mother, daughter struggle between making a living and modular learning”

Pau Villanueva – “Hinubog ng panata: The vanishing spiritual traditions of Aetas of Capas, Tarlac”

Bernice Beltran – “Women's 'invisible work'”

Dada Grifon – “From the cause”

Bernadette Uy – “Enduring the current”

Mark Saludes – “Mission in peril”

EC Toledo – “From sea to shelf: The story before a can is sealed”

Ria Torrente – “HIV positive mother struggles through the Covid-19 pandemic”

Sharlene Festin – “Paradise lost”

PCIJ's investigative reports

THE SHRINKING GODS OF PADRE FAURA | READ .

7 MILLION HECTARES OF PHILIPPINE LAND IS FORESTED – AND THAT'S BAD NEWS | READ

FOLLOWING THE MONEY: PH MEDIA LESSONS FOR THE 2022 POLL | READ

DIGGING FOR PROFITS: WHO OWNS PH MINES? | READ

THE BULACAN TOWN WHERE CHICKENS ARE SLAUGHTERED AND THE RIVER IS DEAD | READ

- 24/7 Crisis Hotline:

- 0917-899-8727

- 24/7 Crisis Hotline:

- DOH-NCMH 24/7 Crisis Hotline:

MentalHealthPH

August 20, 2022

- #UsapTayo , Campaigns , Online

- End The Stigma!

Home » Blog » Philippine Literature and Mental Health

Philippine Literature and Mental Health

Writers/ Researchers: Rafael Reyes, Jasmin Cyrille Tecson Editor: K Ballesteros Peer Reviewer: Azie Marie Liban, Richardson dR Mojica Graphics: Billie Fuentes, Jacklyn Moral, Krystle Mae Labio Tweetchat Moderators: Gie Leanna Dela Pena, DG Ramos Patricia Sevilla Space Moderators: Azie Marie Liban, Billie Fuentes, Lemuel Gallogo

“Crispin! Basilio! Mga anak ko!” This infamous line from Noli Me Tangere is probably one of the many lines that most Filipinos use outside the borders of our schools. Sadly, this is remembered by most Filipinos, not because of Sisa’s character as a loving mother but due to the depiction of Sisa’s mental health condition.

Mental health is an issue that’s been brought up in many novels and textbooks, and continue to be taken out of context. In a study about Filipino help-seeking for mental health problems and associated barriers, stigma was identified as the primary barrier preventing Filipinos from seeking mental health services [1].

Literature is widely defined as written works used to transmit culture. However, literature can also be classified into different forms including stories, oral tradition, and visual literature. In this regard, we also consider folklore, poetry, and dramas in the Philippine context as part of Filipino Literature [2].

This August, as we take pride in celebrating our “Buwan ng Wikang Pambansa”, let’s dwell on the past of how mental health has been viewed in Philippine Literature and in what way can we make a move on how readers will view it moving forward.

To begin with, let us talk about Virgilio Enriquez and Sikolohiyang Pilipino. Filipino Psychology or “Sikolohiyang Pilipino” was first introduced as a movement to help understand the Filipino mind. This idea from Enriquez opened the doors for professionals to talk more about mental health and psychology in the Filipino context [3].

A study about Mental Health Literacy and Mental Health of Filipino College Students included five hundred nineteen (519) participants from six Philippine universities. According to the average Mental Health literacy scores, students from state universities showed significantly higher mental health literacy scores than those in private universities [4].

Nourishing mental health through literature

Reading has always been a timeless hobby. While the books and pieces we read today are an evolution of those that our ancestors engaged with, literature remains to be the best way to vicariously experience the world and the people who have stories to pass on.

What exactly does reading do for us? For one, it teaches us to be empathetic towards others. By engaging in the act of reading, we put ourselves in the shoes of the characters we see, and especially those we relate with. In particular, narratives can contain themes of illness and other health conditions to show the reader how it feels to experience pain and suffering under such conditions [5]. Understanding our bodies, then, is one step closer towards becoming empathic people.

Reading also provides a space for introspection or reflective thinking. Literature teaches us to become critical thinkers [5] and allows us to tap into our inner selves and ask how we were feeling [6]. In the realm of mental health literacy, being in touch with our thoughts and emotions has always been one of the underlying themes towards betterment.

A form of therapy involving literature has recently garnered interest in research: bibliotherapy. Bibliotherapy, refers to the use of literature, film, or other media to better understand and treat various mental health problems [7]. Despite being initially coined in 1916, the Ancient Greeks have had a similar approach to dealing with distress, as do the published books in the 1950s that were geared towards teaching children virtues [7]. A recent study even identified bibliotherapy’s usefulness for mental health and dementia by fostering social connections through a person-centered approach [6].

Suffice to say that literature definitely has an impact on the human person—especially when engaging with the book and letting the book engage with you through empathy and a room for introspection. While it’s not explicitly recognized whenever we ask the average reader about why they like reading, it shows why to this day, reading has become a beloved pastime for many.

Integrating Mental Health into Philippine Literature

The question now becomes: how do we take the power of literature in improving one’s mental health and raising mental health literacy in the Philippines?

Professor Sarce, a lecturer at Ateneo de Manila University, wrote a 2021 paper on the lack of discussion about illness in Philippine Literature discourse [5]. In the said paper, he provides a guide for tackling health and illness that will help students and teachers develop empathy [5]. He emphasizes the idea of “illness narratives” as a way to vicariously experience those who suffer from mental health problems [5]. Through this framework, he implies the need to have more literature that tackles illnesses, whether physical or mental, in order for more people to become more literate and empathic about having illnesses.

In a society where stigma and labeling against mental health is adamant, it is important that mental health is being talked about and written down in our literary works in a way that future generations will reflect on, learn from, and understand.

Pre-Session Activity

- Word Hunt: create a word hunt game with known philippine literature pieces

Session Questions

- What is your favorite piece of Philippine Literature?

- How is the act of reading literature a beneficial hobby?

- How can schools and other institutions utilize our local literature to promote mental health literacy?

References:

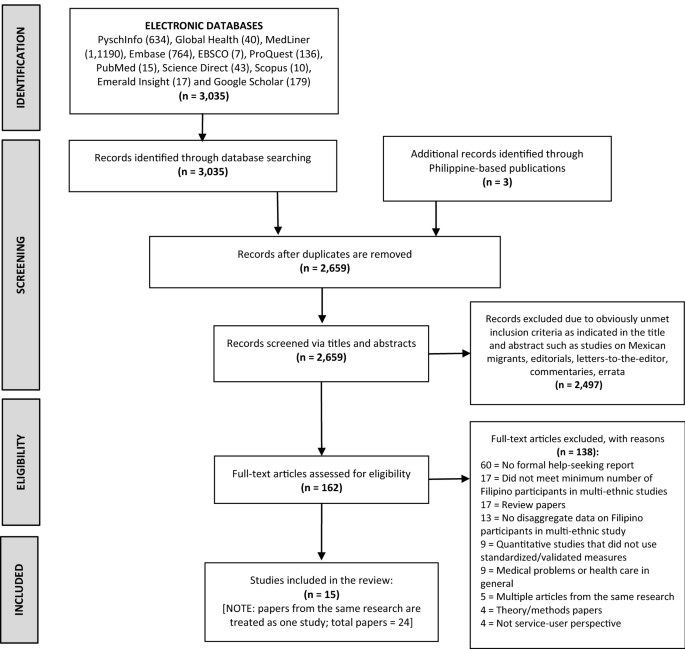

[1] Martinez, A. B., Co, M., Lau, J., & Brown, J. (2020). Filipino help-seeking for mental health problems and associated barriers and facilitators: a systematic review. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 55(11), 1397–1413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01937-2

[2] https://study.com/learn/lesson/literature-forms-types-genres.html#:~:text=Literature%20Meaning,-What%20is%20literature&text=However%2C%20literature%20is%20not%20always,be%20classified%20into%20different%20forms

[3] https://www.ipl.org/essay/Importance-Of-Filipino-Psychology-F3JJYC92PCED6

[4] Argao, R. C., Reyes, M. E., & Delariarte, C. (2021). Mental Health Literacy and Mental Health of Filipino College Students. North American Journal of Psychology, 23, 437–452. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353511438_Mental_Health_Literacy_and_Mental_Health_of_Filipino_College_Students

[5] Sarce, J. P. (2021). Teaching Philippine literature and illness: Finding cure in humanities. Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, 13(2), 1-11. https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v13n2.09

[6] Brewster, L., & McNicol, S. (2021). Bibliotherapy in practice: a person-centred approach to using books for mental health and dementia in the community. Medical Humanities, 47(4), e12-e12. https://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/id/eprint/146978/1/WiM_draft_article_2020_08_11_clean.pdf

[7] Mumbauer, J., & Kelchner, V. (2017). Promoting mental health literacy through bibliotherapy in school-based settings. Professional School Counseling, 21(1), 1096-2409. https://doi.org/10.5330/1096-2409-21.1.85

Recommended Reading

Watch and Listen: Notes from Fanboys of Music and TV Series

July 30, 2021 Writers: Alvin Joseph Mapoy and Jerwin Regala Editor: K Ballesteros Researcher: Nel Fortes Graphics: Krystle Mae

KapwaMH Privacy Statement

Introduction MentalHealthPH is committed to upholding your right to privacy and maintaining the confidentiality of your personal data, similar to

Growing Strong: senior citizens & their mental health in the Philippines

May 10, 2021 Writers: K Ballesteros& Jerwin Regala Researchers: Angelica Jane Evangelista, Azie Marie Libanan &Gie Lenna Dela Peña Graphics:

DISABILITY AND WELL-BEING

January 10, 2024 Writer: CJ Dumaguin, Kevin Miko Buac Researcher: CJ Dumaguin, Kevin Miko Buac Graphics: Jia Moaral, Krystle

#MentalHealthPH

- About Our Organization

- How We Work

- Meet the Team

- Media Mentions

- #VoicesOfHope

- #40SecondsOfHope

Get Involved

- Add a Directory Listing

- Share Your Story

- Volunteer with Us

- Partner with Us

- Start Your Own Chapter

- Make a Donation

Join our newsletter!

- Don't worry, we hate spam too!

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Mental health of Filipino seafarers and its implications for seafarers’ education

International Maritime Health

Related Papers

Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology

Karina G. Fernandez

The Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression (CES-D) scale is a well-validated and frequently used measure for assessing symptoms associated with depression. This scale was developed primarily on the basis of American populations, however, and previous research has suggested that the original factor structure may not be appropriate for all populations. One such population is the Filipino population. This study represents the first study we are aware of to examine the factor structure of the CES-D scale in a sample of Filipino seafarers. Seafaring is considered a high stress and high risk occupation. Based on data collected from 135 Filipino seafarers, we conducted factor analyses to identify the appropriate factor structure for the CES-D in this population. We found that a three-factor structure better described the responses of Filipinos in our sample than the standard four-factor structure. The Filipino factor structure appears to collapse depressive affect and somatic fact...

Ernesto Jr. R Gregorio

Objective: The study documented the Filipino Seafarer's lived experiences related to their health conditions, access to available services and facilities, satisfaction with these, and their coping mechanisms aboard international shipping vessels. Method: Descriptive Phenomenology was used with 12 Filipino Seafarers, in-depth interviews were done in an industrial clinic in Manila port area during their annual medical examination. Results: The most common health-related problems mentioned by informants from dry cargo-tanker vessels were sexually-transmitted infections, hypertension, accidents, heart attack and homesickness. Hypertension, back, knee and muscle pains and liver enzyme elevations were frequently mentioned problems in luxury liners. Circumstances on board like unlimited supply, lack of control over food choices and negative attitude of the cook were perceived to increase seafarer's vulnerability to lifestyle diseases. Loneliness seemed to have contributed to their propensity to engage in high-risk behavior. Informants reported to having access to services and facilities on board as well as satisfaction with these. Gym facilities were seldom used because of work fatigue. Coping mechanism included watching DVDs, singing karaoke, playing video games, listening to music and fishing. Conclusion: Despite the reported access to health information and services, informants still reported occupational and lifestyle-related diseases that were perceived to be associated with the work situation that requires appropriate health promotion strategies.

Ariana Juranko

jonna dotimas

Maritime industry seen as one of the fastest growing jobs now a days and it provides enormous numbers of employee comprising of individuals from several countries. Maritime industry creates good impact on Philippines economy thru the help of Filipino modern heroes also known as Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW). Filipino seafarers are competitive among others due on reliable and hardworking personality. Despite of that, maritime industry provides a lot of challenges on each individual which is part of the industry and it is entitled as one of the most critical jobs around the world. This study focusses on the challenges may encountered of Filipino seafarers on board in order to propose work-life balance. With intent to help Filipino seafarers to improve their way on how they handle daily life on and off the vessel. The researchers used descriptive study to provide naturally occurring health status, behavior, attitude, or other characteristic of particular group. Utilizing the data gat...

International Journal of Community & Family Medicine

Olaf Jensen

Marta Grubman-Nowak

Sanley Abila , Lijun Tang

Lyrad Porley

SUMMARY Although the Philippines provides more than one quarter of the world's seafarers employed aboard internationally trading ships, and its position as the world's leading supplier of ships' crews seems assured, it has not been possible for crew managers, officers of international agencies, associations and other interested parties to find reliable information about Filipino seafarers and their circumstances in one publication. This report modestly aims to remedy this gap, by providing a profile of the Philippine seafarers in the global labour market. Between October 2002 and January 2003, separate surveys were conducted, of seafarers (n=374) and students (n=658) enrolled in 11 maritime colleges, with the aim of generating a dependable profile of Filipino seafarers. The survey results were subsequently amplified by a search of available documentation and interviews with crewing managers, senior government and trade union officials. Websites and publications by government agencies, employers and unions, and seafarer organizations provided other data.

Journal of Medicine, University of Santo Tomas

Maria Minerva Calimag

Background: The seafarers’ poor mental health has been associated with significant morbidity, inefficiency, and accidents on board. Mental and physical health is largely dependent on the way seafarers handle stressors. Anchored on the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, this study aimed to identify the typology of Filipino merchant marine ratings according to their coping strategies to stressors on board vessels. Methods: Thirty-seven (37) Filipino merchant marine ratings participated in this study. They were chosen by purposive sampling. They rank-ordered 25 opinion statements on various stressors and coping mechanisms. The rank-ordered sorts were subjected to by-person factor analysis with Varimax rotation using the PQ Method version 2.32. The resulting factors were interpreted using the inductive approach, aided by the interview done after Q sorting. Results: Four factors were generated: solution-focused seafarers, stressor-focused seafarers, self-management–focused seafare...

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Manage Your Subscription

- Give a Gift Subscription

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

- Entertainment

'There Will Be Lumpia:' What Mom's Food Says About Love and Family (Exclusive)

'Bite By Bite' author Aimee Nezhukumatathil reflects on how her mother showed love through food in an exclusive excerpt from her new book

Articulate Photography by Tenola; Ecco

So often, the first and most powerful memories we have of our parents and families of origin center around food. The flavors of our childhood can contextualize who we are and where we came from, and who we want to become.

In her new book, Bite by Bite: Nourishments and Jamborees , poet and essayist Aimee Nezhukumatathil interrogates the way food and drink intertwines with our human experiences and identities and explores the often murky boundaries between heritage and memory. Below, in an exclusive excerpt for PEOPLE, she reflects on how a teenage slumber party taught her to appreciate an important food from her Filipino culture.