- Library guides

- Book study rooms

- Library Workshops

- Library Account

- Library Services

- Library Services Home

- Library Guides

- Business School Guides

- Market research

- Citing and referencing market research

- Statistics and economics

- Case studies

Guidance from Cite Them Right Online

Cite Them Right Online provides a few different types of guidance that can be relevant for Referencing Market Research and Data. The most straightforward is the guidance for referencing Market research reports from online databases . Navigate to Harvard > Research > Reports > Market research reports from online databases to find the guidance.

Market Research Reports referenced in Harvard will resemble the following:

In-text citation: (MarketLine, 2019)

Reference List:

MarketLine (2019) 'United Kingdom - Gyms, Health & Fitness Clubs'. Available at: http://advantage.marketline.com/ (Accessed: 14 August 2019).

Using RefWorks to cite and reference company information

RefWorks is an online reference management, writing and collaboration tool designed to help researchers at all levels gather, organise, store and share all types of information and to generate citations and bibliographies.

Market research references can be added to your RefWorks library so you can quickly and easily add it to your work, but RefWorks does not have as many standard formats for doing this as Cite Them Right Online.

- Add a reference to market research using the + button in the web version of RefWorks.

- Select the 'Report' option for the type of source you wish to reference. This will give you a set of boxes with various details to fill in such as 'Title', 'Date of Publication'.

- Using the guidance above from Cite Them Right Online , fill out the boxes with the information you have available.

- The author of the data will be the publisher of the database that you got it from because market research databases publish their own information. So, for example, if you used Mintel, the author will be Mintel.

You can then click on the " symbol in RefWorks to check what your reference will look like when it appears in a bibliography. Make sure you have selected 'Cite Them Right - Harvard'.

- << Previous: Case studies

- Last Updated: Mar 12, 2024 3:12 PM

- URL: https://libguides.city.ac.uk/marketresearch

Marketing & Advertising

- News/Articles

- Company/Industry Info

- Consumer/Market Data

- Advertising Resources

- Ad Rates This link opens in a new window

How To Cite Using APA Style (Videos)

Citing journal/magazine articles, citing web pages, citing books.

- Citing Business Databases

Citing Newspaper Articles

- Associations

American Psychological Association, or APA, style is commonly used in the social and behavioral sciences. Check out the resources and example citations on this page.

- Basics of APA Style Tutorial

- Citing References: APA Style [PDF]

- Purdue OWL - APA 7th ed. Formatting and Style Guide

This video playlist walks you through why to use APA (below), and how to cite books , articles , webpages , and business resources . Watch whichever ones you need!

Plagiarism involves taking credit for work that is not one's own. Below are some resources that can help you avoid plagiarism.

- Avoiding Academic Misconduct (UWW Dean of Students) [Word Doc]

- Plagiarism: Cut & Paste Doesn't Cut It [Interactive Tutorial]

With DOI Assigned:

Without a DOI Assigned:

Example:

See other article citation examples here: http://libguides.uww.edu/apa/articles

Basic webpage: .

Corporate author:

See other website citation examples here: http://libguides.uww.edu/apa/web

See other book citation examples here: http://libguides.uww.edu/apa/books

For help citing all the unusual business databases, visit this page: http://libguides.uww.edu/apa/business, free online: .

Note: If there is no author listed, the title of the article comes first, followed by the date.

Print, or from a database with no DOI:

- << Previous: Ad Rates

- Next: Associations >>

- Last Updated: Feb 26, 2024 11:37 AM

- URL: https://libguides.uww.edu/marketing

*MARKETING RESEARCH*

- Annotated bibliography

- Peer reviewed articles

- Books/eBooks

- Demographics

- Library DIY

- Off-campus access

Business Citations

Market research report, swot analysis, online industry profile/report, online company profile, apa-can't find what you're looking for.

- Ask a Librarian

IMPORTANT NOTE: Citing Business Resources:

Although the APA provides clear instructions on how to cite standard publication types, some business-specific sources include unique information that is not addressed in APA instructions. Because of that, some of the examples and instructions on this page represent the B.D. Owens Library's interpretation of APA rules. The American Psychological Association maintains a Style Blog that addresses many frequently asked questions.

If there is no official title, create a non-italicized description in square brackets (see section 9.22, page 292). The square brackets indicate to somebody else searching the database cannot use the exact words to search for the item, but can indicate how to locate similar information.

For citing resources that are more standardized in business databases (Business Source Premier, Nexis Uni), click here .

REFERENCE (BUSINESS SOURCE PREMIER)

![how to reference market research [ APA: Market Research Report ]](https://libapps.s3.amazonaws.com/customers/2793/images/Market_Research_Report.PNG)

IN TEXT

("Executive summary," 2009).

MarketLine. (2019, November 29). NIKE Inc [SWOT analysis]. Business Source Premier .

( MarketLine, 2019).

- Business Source Premier

REFERENCE

MarketLine. (2019, May). Industry profile: Mobile phones in the United States. Business Source Premier .

NOTE: Include the database name if content only appears in a particular database . Include the retrieval date if content changes over time and versions of the page are not archived. Multiple citations to different works from the one author from the same year are distinguished by assigning a, b, c, to the citations in text and also in the reference list. This is entered after the date.

MarketLine. (2020a, September). Marketline industry profile: Airlines in North America. MarketLine.

MarketLine. (2020b, September). MarketLine industry profile: Airlines in the United States. MarketLine .

(MarketLine, 2020a).

(MarketLine, 2020b).

(see p. 296 section 9.30 and p. 319 examples 13 and 14 of the 7th edition)

NOTE: Include the database name if content only appears in a particular database .

REFERENCE

MarketLine. (2019, October 25). Cerner Corporation [Company profile] . Business Source Premier .

IN TEXT

(MarketLine, 2019).

NOTE: Include the database name if content only appears in a particular database . Include the retrieval date if content changes over time and versions of the page are not archived.

MarketLine. (2020, April 13). Walmart Inc [Company profile] . MarketLine Advantage . Retrieved June 10, 2020, from https://advantage.marketline.com/Company/Profile/wal_mart_stores_inc?companyprofile

( MarketLine, 2020).

NOTE: Include the database name if content only appears in a particular database . Include the retrieval date if content changes over time and versions of the page are not archived.

Zoom Company Information. (2020, January 2). Starbucks Corporation [Company profile]. Nexis Uni . Retrieved February 3, 2020, from https://advance.lexis.com/api/permalink/c876bb8e-2b26-4db3-bb27-c1317259766c/?context=1516831

(Zoom Company Information, 2020).

NOTE: Include the retrieval date if content changes over time and versions of the page are not archived.

REFERENCE (Lexisnexis)

Walmart Inc. (2020, October 2). Form 8-K [SEC Filings]. Nexis Uni . Retrieved October 6, 2020.

(Walmart Inc., 2020).

Get more APA examples :

![how to reference market research [ more APA Style examples ]](https://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/customers/2793/images/apa.png)

- << Previous: Off-campus access

- Next: Ask a Librarian >>

- Last Updated: Feb 19, 2024 9:33 AM

- URL: https://libguides.nwmissouri.edu/marketing

- Library Hours

- Strategic Plan

- Giving to the Libraries

- Jobs at the Libraries

- Find Your Librarian

- View All →

- Google Scholar

- Research Guides

- Textbook/Reserves

- Government Documents

- Get It For Me

- Print/Copy/Scan

- Renew Materials

- Study Rooms

- Use a Computer

- Borrow Tech Gear

- Student Services

- Faculty Services

- Users with Disabilities

- Visitors & Alumni

- Special Collections

- Find Information

Industry Research

- Getting Started

- Industry Classifications

- U.S. Census Bureau Industry Data

- Industry Financials & Ratios

- Trade Associations

- Regulation & Government Agencies

- Porter's Five Forces

- Value Chain Analysis & VRIO

- Industry Data & Statistics

Citing Sources in APA Style

The purpose of citing is (1) to give credit to the original author, and (2) enable the reader to find the source. The American Psychological Association (APA) citation style is widely used in business school courses. You may find general guidelines in:

- APA Style Guide: OWL at Excelsior

The APA Style Manual doesn't address directly how to cite business-type sources from library databases, such as analyst reports, market research reports, industry profiles, etc. These sources may not have the same citation elements as books, journal articles, or open access websites:

- Reports often don't list a named individual author. In this case, the name of the publisher or organization that produced information will serve as a corporate author.

- URLs from the address bar for the content in library databases may be too long, inaccessible to readers because of a firewall, or expire after a session. If the URL is not accessible, use the name of a database.

- The APA Style Manual no longer requires the date the information is retrieved.

Suggested Format for Citing Reports in APA style:

Author, A. A., & Author, B. B. (Date of publication). Title of document . Publisher [optional]. Retrieved from [database name].

NOTE: Use Publisher / Contributor / Organization Name:

- Only if this name is different from the database name and there is a named personal author

- As a corporate author at the beginning of the citation, if no personal author is listed

How to Build an APA Citation for a Report

You may easily create your own APA citation once you identify appropriate elements of a document for citing.

EXAMPLE 1: A report with a named author, produced by S&P Capital IQ McGraw Hill Financial and retrieved from the S&P Capital IQ NetAdvantage database

CITATION: Holt, D. (2016, March). Industry surveys: Electronic equipment & instruments . Retrieved from S&P Capital IQ NetAdvantage.

EXAMPLE 2: A report without a named author, produced by Euromonitor International, and retrieved from the Passport database. The name of the publisher is used as a corporate author.

CITATION: Euromonitor International. (2016, September). Wearable electronics in the US . Retrieved from Passport database.

NOTE: Always check with your professor for specific citation guidelines.

Several libraries created examples for citing business sources in APA style:

- Citing Online Business Resources in APA Style: Bentley Library Guide

- Citing Business Databases in APA: University of North Carolina Greensboro

- Citing Business Resources APA Style: California State University Chico

- << Previous: Salaries

- Last Updated: Mar 31, 2024 11:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.utsa.edu/industry

- Library Locations

- Staff Directory

- 508 Compliance

- Site Search

- © The University of Texas at San Antonio

- Information: 210-458-4011

- Campus Alerts

- Required Links

- UTSA Policies

- Report Fraud

- Find Data about Consumers

- Find Data about Companies

- Find Data about Retail Locations

- Cite Your Sources

- Find Scholarly Articles

- MKTG Course Guides

- CoB Faculty Resources

- OnPoint: Business Booklists This link opens in a new window

- Listen to Podcasts on Marketing

- Responsible Use of Databases

Business Librarian

Document information as you research

Document information as you find it.

Pasting a bunch of links into a document and making sense of them later is counterproductive. It wastes time if you have to re-scan and determine value later. Instead, highlight exactly what key information a source provides as you collect sources. Two other tips:

- Use persistent or permalinks. Beware! Copying the URL from the browser won't always reopen the search results.

- Adopt a file-naming convention to make your documents easier to search

- Pro tip: Save your research with persistent links (PDF) Some business databases don't let you copy the URL and re-open the article later. This file shows how to access search results at a later time.

- Pro tip: Name your files smartly (PDF) Using a file-naming convention (FNC) will save time and reduce stress.

Recommended resources

- Document sources_Template (Google Sheets) Make a copy of this template into your Google Drive folder and document where you find evidence to cite later.

Choose a citation manager

Most business reports require 2 types of citations: In-text citations in the narrative and an alphabetized bibliography of citations at the end.

Remember: The goal of every in-text citation is to direct your readers back to the bibliography so they can verify the information on their own. They work together.

Recommended citation generator

- ZoteroBib Helps you build a bibliography instantly from any computer or device, without creating an account or installing any software

Other help with APA style

- Doing Business Research: What information you need to cite JMU business databases Shows you how to create citations for common business databases, since citation generators often can't parse permalinks.

- Complete APA citation guide for COB 300 (PDF) Includes a sample of what a bibliography and in-text citations should look like in APA 7th.

- APA Formatting & Style Guide A thorough guide to APA style from Purdue University.

- Missing Pieces: How to Write an APA Style Reference Even Without All the Information The authors of the APA style manual answers questions about unique style problems, e.g., "How do I cite a mobile app?"

- JMU Writing Center Schedule an appointment or attend drop-in hours in the Student Success Center.

- << Previous: Find Data about Retail Locations

- Next: Find Scholarly Articles >>

- Last Updated: Mar 22, 2024 1:11 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.jmu.edu/mktg

- Our story /

- Teaching & learning /

- The city of Liverpool /

- International university /

- Widening participation

- Campus & facilities

- Our organisation

University Library

- University of Liverpool Library

- Library Help

Q. How do I cite a Market Research Report using the Harvard Style?

- 25 About the Library

- 9 Accessibility

- 19 Borrow, renew, return

- 1 Collection Management

- 28 Computers and IT

- 28 Copyright

- 36 Databases

- 11 Disability Support

- 7 Dissertations & Theses

- 13 Electronic resources

- 48 Find Things

- 23 General services

- 34 Help & Support

- 2 Inter-Library Loans

- 13 Journals

- 5 Library facilities

- 7 Library Membership

- 9 Management School

- 3 Newspapers

- 26 Off-Campus

- 77 Online Resources

- 4 Open Access

- 28 Reading Lists

- 40 Referencing

- 5 Registration

- 11 Repository

- 17 Research Support

- 2 Reservations

- 2 Science Fiction

- 11 Search Tools

- 5 Special Collections & Archives

- 3 Standards & Patents

- 16 Student Support

- 7 Study Rooms

- 47 Using the Library

- 11 Visitors

Answered By: Sarah Roughley Barake Last Updated: Feb 16, 2023 Views: 18159

DISCOVER and the Library Catalogue have been replaced by Library Search . We're busy updating all of our links, but in the meantime, please use Library Search when searching for resources or managing your Library Account.

To reference market research reports in Harvard style, please see the appropriate section in Cite-Them-Right .

Please note you should always refer to any departmental/school guidelines you’ve been given.

Links & Files

- Referencing Guide

- Share on Facebook

Was this helpful? Yes 12 No 5

Comments (0)

Related questions, browse topics.

- About the Library

- Accessibility

- Borrow, renew, return

- Collection Management

- Computers and IT

- Disability Support

- Dissertations & Theses

- Electronic resources

- Find Things

- General services

- Help & Support

- Inter-Library Loans

- Library facilities

- Library Membership

- Management School

- Online Resources

- Open Access

- Reading Lists

- Referencing

- Registration

- Research Support

- Reservations

- Science Fiction

- Search Tools

- Special Collections & Archives

- Standards & Patents

- Student Support

- Study Rooms

- Using the Library

- Library Website Accessibility Statement

- Customer Charter

- Library Regulations

- Acceptable use of e-Resources

- Service Standards

- Re-use of Public Sector Information

- Victoria Gallery & Museum

- Garstang Museum

- Libraries, Museums and Galleries - Intranet

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » References in Research – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

References in Research – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

References in Research

Definition:

References in research are a list of sources that a researcher has consulted or cited while conducting their study. They are an essential component of any academic work, including research papers, theses, dissertations, and other scholarly publications.

Types of References

There are several types of references used in research, and the type of reference depends on the source of information being cited. The most common types of references include:

References to books typically include the author’s name, title of the book, publisher, publication date, and place of publication.

Example: Smith, J. (2018). The Art of Writing. Penguin Books.

Journal Articles

References to journal articles usually include the author’s name, title of the article, name of the journal, volume and issue number, page numbers, and publication date.

Example: Johnson, T. (2021). The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health. Journal of Psychology, 32(4), 87-94.

Web sources

References to web sources should include the author or organization responsible for the content, the title of the page, the URL, and the date accessed.

Example: World Health Organization. (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public

Conference Proceedings

References to conference proceedings should include the author’s name, title of the paper, name of the conference, location of the conference, date of the conference, and page numbers.

Example: Chen, S., & Li, J. (2019). The Future of AI in Education. Proceedings of the International Conference on Educational Technology, Beijing, China, July 15-17, pp. 67-78.

References to reports typically include the author or organization responsible for the report, title of the report, publication date, and publisher.

Example: United Nations. (2020). The Sustainable Development Goals Report. United Nations.

Formats of References

Some common Formates of References with their examples are as follows:

APA (American Psychological Association) Style

The APA (American Psychological Association) Style has specific guidelines for formatting references used in academic papers, articles, and books. Here are the different reference formats in APA style with examples:

Author, A. A. (Year of publication). Title of book. Publisher.

Example : Smith, J. K. (2005). The psychology of social interaction. Wiley-Blackwell.

Journal Article

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (Year of publication). Title of article. Title of Journal, volume number(issue number), page numbers.

Example : Brown, L. M., Keating, J. G., & Jones, S. M. (2012). The role of social support in coping with stress among African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(1), 218-233.

Author, A. A. (Year of publication or last update). Title of page. Website name. URL.

Example : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, December 11). COVID-19: How to protect yourself and others. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html

Magazine article

Author, A. A. (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of article. Title of Magazine, volume number(issue number), page numbers.

Example : Smith, M. (2019, March 11). The power of positive thinking. Psychology Today, 52(3), 60-65.

Newspaper article:

Author, A. A. (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of article. Title of Newspaper, page numbers.

Example: Johnson, B. (2021, February 15). New study shows benefits of exercise on mental health. The New York Times, A8.

Edited book

Editor, E. E. (Ed.). (Year of publication). Title of book. Publisher.

Example : Thompson, J. P. (Ed.). (2014). Social work in the 21st century. Sage Publications.

Chapter in an edited book:

Author, A. A. (Year of publication). Title of chapter. In E. E. Editor (Ed.), Title of book (pp. page numbers). Publisher.

Example : Johnson, K. S. (2018). The future of social work: Challenges and opportunities. In J. P. Thompson (Ed.), Social work in the 21st century (pp. 105-118). Sage Publications.

MLA (Modern Language Association) Style

The MLA (Modern Language Association) Style is a widely used style for writing academic papers and essays in the humanities. Here are the different reference formats in MLA style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Book. Publisher, Publication year.

Example : Smith, John. The Psychology of Social Interaction. Wiley-Blackwell, 2005.

Journal article

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal, volume number, issue number, Publication year, page numbers.

Example : Brown, Laura M., et al. “The Role of Social Support in Coping with Stress among African American Adolescents.” Journal of Research on Adolescence, vol. 22, no. 1, 2012, pp. 218-233.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Webpage.” Website Name, Publication date, URL.

Example : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “COVID-19: How to Protect Yourself and Others.” CDC, 11 Dec. 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Magazine, Publication date, page numbers.

Example : Smith, Mary. “The Power of Positive Thinking.” Psychology Today, Mar. 2019, pp. 60-65.

Newspaper article

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Newspaper, Publication date, page numbers.

Example : Johnson, Bob. “New Study Shows Benefits of Exercise on Mental Health.” The New York Times, 15 Feb. 2021, p. A8.

Editor’s Last name, First name, editor. Title of Book. Publisher, Publication year.

Example : Thompson, John P., editor. Social Work in the 21st Century. Sage Publications, 2014.

Chapter in an edited book

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Chapter.” Title of Book, edited by Editor’s First Name Last name, Publisher, Publication year, page numbers.

Example : Johnson, Karen S. “The Future of Social Work: Challenges and Opportunities.” Social Work in the 21st Century, edited by John P. Thompson, Sage Publications, 2014, pp. 105-118.

Chicago Manual of Style

The Chicago Manual of Style is a widely used style for writing academic papers, dissertations, and books in the humanities and social sciences. Here are the different reference formats in Chicago style:

Example : Smith, John K. The Psychology of Social Interaction. Wiley-Blackwell, 2005.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal volume number, no. issue number (Publication year): page numbers.

Example : Brown, Laura M., John G. Keating, and Sarah M. Jones. “The Role of Social Support in Coping with Stress among African American Adolescents.” Journal of Research on Adolescence 22, no. 1 (2012): 218-233.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Webpage.” Website Name. Publication date. URL.

Example : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “COVID-19: How to Protect Yourself and Others.” CDC. December 11, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Magazine, Publication date.

Example : Smith, Mary. “The Power of Positive Thinking.” Psychology Today, March 2019.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Newspaper, Publication date.

Example : Johnson, Bob. “New Study Shows Benefits of Exercise on Mental Health.” The New York Times, February 15, 2021.

Example : Thompson, John P., ed. Social Work in the 21st Century. Sage Publications, 2014.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Chapter.” In Title of Book, edited by Editor’s First Name Last Name, page numbers. Publisher, Publication year.

Example : Johnson, Karen S. “The Future of Social Work: Challenges and Opportunities.” In Social Work in the 21st Century, edited by John P. Thompson, 105-118. Sage Publications, 2014.

Harvard Style

The Harvard Style, also known as the Author-Date System, is a widely used style for writing academic papers and essays in the social sciences. Here are the different reference formats in Harvard Style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of publication. Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher.

Example : Smith, John. 2005. The Psychology of Social Interaction. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of publication. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal volume number (issue number): page numbers.

Example: Brown, Laura M., John G. Keating, and Sarah M. Jones. 2012. “The Role of Social Support in Coping with Stress among African American Adolescents.” Journal of Research on Adolescence 22 (1): 218-233.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of publication. “Title of Webpage.” Website Name. URL. Accessed date.

Example : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. “COVID-19: How to Protect Yourself and Others.” CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html. Accessed April 1, 2023.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of publication. “Title of Article.” Title of Magazine, month and date of publication.

Example : Smith, Mary. 2019. “The Power of Positive Thinking.” Psychology Today, March 2019.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of publication. “Title of Article.” Title of Newspaper, month and date of publication.

Example : Johnson, Bob. 2021. “New Study Shows Benefits of Exercise on Mental Health.” The New York Times, February 15, 2021.

Editor’s Last name, First name, ed. Year of publication. Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher.

Example : Thompson, John P., ed. 2014. Social Work in the 21st Century. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of publication. “Title of Chapter.” In Title of Book, edited by Editor’s First Name Last Name, page numbers. Place of publication: Publisher.

Example : Johnson, Karen S. 2014. “The Future of Social Work: Challenges and Opportunities.” In Social Work in the 21st Century, edited by John P. Thompson, 105-118. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Vancouver Style

The Vancouver Style, also known as the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals, is a widely used style for writing academic papers in the biomedical sciences. Here are the different reference formats in Vancouver Style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Book. Edition number. Place of publication: Publisher; Year of publication.

Example : Smith, John K. The Psychology of Social Interaction. 2nd ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2005.

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Article. Abbreviated Journal Title. Year of publication; volume number(issue number):page numbers.

Example : Brown LM, Keating JG, Jones SM. The Role of Social Support in Coping with Stress among African American Adolescents. J Res Adolesc. 2012;22(1):218-233.

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Webpage. Website Name [Internet]. Publication date. [cited date]. Available from: URL.

Example : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19: How to Protect Yourself and Others [Internet]. 2020 Dec 11. [cited 2023 Apr 1]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html.

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Article. Title of Magazine. Year of publication; month and day of publication:page numbers.

Example : Smith M. The Power of Positive Thinking. Psychology Today. 2019 Mar 1:32-35.

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Article. Title of Newspaper. Year of publication; month and day of publication:page numbers.

Example : Johnson B. New Study Shows Benefits of Exercise on Mental Health. The New York Times. 2021 Feb 15:A4.

Editor’s Last name, First name, editor. Title of Book. Edition number. Place of publication: Publisher; Year of publication.

Example: Thompson JP, editor. Social Work in the 21st Century. 1st ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014.

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Chapter. In: Editor’s Last name, First name, editor. Title of Book. Edition number. Place of publication: Publisher; Year of publication. page numbers.

Example : Johnson KS. The Future of Social Work: Challenges and Opportunities. In: Thompson JP, editor. Social Work in the 21st Century. 1st ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014. p. 105-118.

Turabian Style

Turabian style is a variation of the Chicago style used in academic writing, particularly in the fields of history and humanities. Here are the different reference formats in Turabian style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher, Year of publication.

Example : Smith, John K. The Psychology of Social Interaction. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2005.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal volume number, no. issue number (Year of publication): page numbers.

Example : Brown, LM, Keating, JG, Jones, SM. “The Role of Social Support in Coping with Stress among African American Adolescents.” J Res Adolesc 22, no. 1 (2012): 218-233.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Webpage.” Name of Website. Publication date. Accessed date. URL.

Example : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “COVID-19: How to Protect Yourself and Others.” CDC. December 11, 2020. Accessed April 1, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Magazine, Month Day, Year of publication, page numbers.

Example : Smith, M. “The Power of Positive Thinking.” Psychology Today, March 1, 2019, 32-35.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Newspaper, Month Day, Year of publication.

Example : Johnson, B. “New Study Shows Benefits of Exercise on Mental Health.” The New York Times, February 15, 2021.

Editor’s Last name, First name, ed. Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher, Year of publication.

Example : Thompson, JP, ed. Social Work in the 21st Century. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2014.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Chapter.” In Title of Book, edited by Editor’s Last name, First name, page numbers. Place of publication: Publisher, Year of publication.

Example : Johnson, KS. “The Future of Social Work: Challenges and Opportunities.” In Social Work in the 21st Century, edited by Thompson, JP, 105-118. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2014.

IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) Style

IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) style is commonly used in engineering, computer science, and other technical fields. Here are the different reference formats in IEEE style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Book Title. Place of Publication: Publisher, Year of publication.

Example : Oppenheim, A. V., & Schafer, R. W. Discrete-Time Signal Processing. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2010.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Abbreviated Journal Title, vol. number, no. issue number, pp. page numbers, Month year of publication.

Example: Shannon, C. E. “A Mathematical Theory of Communication.” Bell System Technical Journal, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 379-423, July 1948.

Conference paper

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Paper.” In Title of Conference Proceedings, Place of Conference, Date of Conference, pp. page numbers, Year of publication.

Example: Gupta, S., & Kumar, P. “An Improved System of Linear Discriminant Analysis for Face Recognition.” In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Science and Network Technology, Harbin, China, Dec. 2011, pp. 144-147.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Webpage.” Name of Website. Date of publication or last update. Accessed date. URL.

Example : National Aeronautics and Space Administration. “Apollo 11.” NASA. July 20, 1969. Accessed April 1, 2023. https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/apollo/apollo11.html.

Technical report

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Report.” Name of Institution or Organization, Report number, Year of publication.

Example : Smith, J. R. “Development of a New Solar Panel Technology.” National Renewable Energy Laboratory, NREL/TP-6A20-51645, 2011.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Patent.” Patent number, Issue date.

Example : Suzuki, H. “Method of Producing Carbon Nanotubes.” US Patent 7,151,019, December 19, 2006.

Standard Title. Standard number, Publication date.

Example : IEEE Standard for Floating-Point Arithmetic. IEEE Std 754-2008, August 29, 2008

ACS (American Chemical Society) Style

ACS (American Chemical Society) style is commonly used in chemistry and related fields. Here are the different reference formats in ACS style:

Author’s Last name, First name; Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Article. Abbreviated Journal Title Year, Volume, Page Numbers.

Example : Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Cui, Y.; Ma, Y. Facile Preparation of Fe3O4/graphene Composites Using a Hydrothermal Method for High-Performance Lithium Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 2715-2721.

Author’s Last name, First name. Book Title; Publisher: Place of Publication, Year of Publication.

Example : Carey, F. A. Organic Chemistry; McGraw-Hill: New York, 2008.

Author’s Last name, First name. Chapter Title. In Book Title; Editor’s Last name, First name, Ed.; Publisher: Place of Publication, Year of Publication; Volume number, Chapter number, Page Numbers.

Example : Grossman, R. B. Analytical Chemistry of Aerosols. In Aerosol Measurement: Principles, Techniques, and Applications; Baron, P. A.; Willeke, K., Eds.; Wiley-Interscience: New York, 2001; Chapter 10, pp 395-424.

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Webpage. Website Name, URL (accessed date).

Example : National Institute of Standards and Technology. Atomic Spectra Database. https://www.nist.gov/pml/atomic-spectra-database (accessed April 1, 2023).

Author’s Last name, First name. Patent Number. Patent Date.

Example : Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; Chen, H.; Zhang, W. US Patent 9,999,999, December 31, 2022.

Author’s Last name, First name; Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Article. In Title of Conference Proceedings, Publisher: Place of Publication, Year of Publication; Volume Number, Page Numbers.

Example : Jia, H.; Xu, S.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Huang, X. Fast Adsorption of Organic Pollutants by Graphene Oxide. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 2017; Volume 1, pp 223-228.

AMA (American Medical Association) Style

AMA (American Medical Association) style is commonly used in medical and scientific fields. Here are the different reference formats in AMA style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Article Title. Journal Abbreviation. Year; Volume(Issue):Page Numbers.

Example : Jones, R. A.; Smith, B. C. The Role of Vitamin D in Maintaining Bone Health. JAMA. 2019;321(17):1765-1773.

Author’s Last name, First name. Book Title. Edition number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year.

Example : Guyton, A. C.; Hall, J. E. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2015.

Author’s Last name, First name. Chapter Title. In: Editor’s Last name, First name, ed. Book Title. Edition number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year: Page Numbers.

Example: Rajakumar, K. Vitamin D and Bone Health. In: Holick, M. F., ed. Vitamin D: Physiology, Molecular Biology, and Clinical Applications. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:211-222.

Author’s Last name, First name. Webpage Title. Website Name. URL. Published date. Updated date. Accessed date.

Example : National Cancer Institute. Breast Cancer Prevention (PDQ®)–Patient Version. National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/breast/patient/breast-prevention-pdq. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed April 1, 2023.

Author’s Last name, First name. Conference presentation title. In: Conference Title; Conference Date; Place of Conference.

Example : Smith, J. R. Vitamin D and Bone Health: A Meta-Analysis. In: Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research; September 20-23, 2022; San Diego, CA.

Thesis or dissertation

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Thesis or Dissertation. Degree level [Doctoral dissertation or Master’s thesis]. University Name; Year.

Example : Wilson, S. A. The Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Bone Health in Postmenopausal Women [Doctoral dissertation]. University of California, Los Angeles; 2018.

ASCE (American Society of Civil Engineers) Style

The ASCE (American Society of Civil Engineers) style is commonly used in civil engineering fields. Here are the different reference formats in ASCE style:

Author’s Last name, First name. “Article Title.” Journal Title, volume number, issue number (year): page numbers. DOI or URL (if available).

Example : Smith, J. R. “Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Sustainable Drainage Systems in Urban Areas.” Journal of Environmental Engineering, vol. 146, no. 3 (2020): 04020010. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EE.1943-7870.0001668.

Example : McCuen, R. H. Hydrologic Analysis and Design. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education; 2013.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Chapter Title.” In: Editor’s Last name, First name, ed. Book Title. Edition number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year: page numbers.

Example : Maidment, D. R. “Floodplain Management in the United States.” In: Shroder, J. F., ed. Treatise on Geomorphology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2013: 447-460.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Paper Title.” In: Conference Title; Conference Date; Location. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year: page numbers.

Example: Smith, J. R. “Sustainable Drainage Systems for Urban Areas.” In: Proceedings of the ASCE International Conference on Sustainable Infrastructure; November 6-9, 2019; Los Angeles, CA. Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers; 2019: 156-163.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Report Title.” Report number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year.

Example : U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. “Hurricane Sandy Coastal Risk Reduction Program, New York and New Jersey.” Report No. P-15-001. Washington, DC: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; 2015.

CSE (Council of Science Editors) Style

The CSE (Council of Science Editors) style is commonly used in the scientific and medical fields. Here are the different reference formats in CSE style:

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. “Article Title.” Journal Title. Year;Volume(Issue):Page numbers.

Example : Smith, J.R. “Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Sustainable Drainage Systems in Urban Areas.” Journal of Environmental Engineering. 2020;146(3):04020010.

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. Book Title. Edition number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year.

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. “Chapter Title.” In: Editor’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial., ed. Book Title. Edition number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year:Page numbers.

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. “Paper Title.” In: Conference Title; Conference Date; Location. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year.

Example : Smith, J.R. “Sustainable Drainage Systems for Urban Areas.” In: Proceedings of the ASCE International Conference on Sustainable Infrastructure; November 6-9, 2019; Los Angeles, CA. Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers; 2019.

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. “Report Title.” Report number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year.

Bluebook Style

The Bluebook style is commonly used in the legal field for citing legal documents and sources. Here are the different reference formats in Bluebook style:

Case citation

Case name, volume source page (Court year).

Example : Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

Statute citation

Name of Act, volume source § section number (year).

Example : Clean Air Act, 42 U.S.C. § 7401 (1963).

Regulation citation

Name of regulation, volume source § section number (year).

Example: Clean Air Act, 40 C.F.R. § 52.01 (2019).

Book citation

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. Book Title. Edition number (if applicable). Place of Publication: Publisher; Year.

Example: Smith, J.R. Legal Writing and Analysis. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Aspen Publishers; 2015.

Journal article citation

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. “Article Title.” Journal Title. Volume number (year): first page-last page.

Example: Garcia, C. “The Right to Counsel: An International Comparison.” International Journal of Legal Information. 43 (2015): 63-94.

Website citation

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. “Page Title.” Website Title. URL (accessed month day, year).

Example : United Nations. “Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/ (accessed January 3, 2023).

Oxford Style

The Oxford style, also known as the Oxford referencing system or the documentary-note citation system, is commonly used in the humanities, including literature, history, and philosophy. Here are the different reference formats in Oxford style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Book Title. Place of Publication: Publisher, Year of Publication.

Example : Smith, John. The Art of Writing. New York: Penguin, 2020.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Article Title.” Journal Title volume, no. issue (year): page range.

Example: Garcia, Carlos. “The Role of Ethics in Philosophy.” Philosophy Today 67, no. 3 (2019): 53-68.

Chapter in an edited book citation

Author’s Last name, First name. “Chapter Title.” In Book Title, edited by Editor’s Name, page range. Place of Publication: Publisher, Year of Publication.

Example : Lee, Mary. “Feminism in the 21st Century.” In The Oxford Handbook of Feminism, edited by Jane Smith, 51-69. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Page Title.” Website Title. URL (accessed day month year).

Example : Jones, David. “The Importance of Learning Languages.” Oxford Language Center. https://www.oxfordlanguagecenter.com/importance-of-learning-languages/ (accessed 3 January 2023).

Dissertation or thesis citation

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Dissertation/Thesis.” PhD diss., University Name, Year of Publication.

Example : Brown, Susan. “The Art of Storytelling in American Literature.” PhD diss., University of Oxford, 2020.

Newspaper article citation

Author’s Last name, First name. “Article Title.” Newspaper Title, Month Day, Year.

Example : Robinson, Andrew. “New Developments in Climate Change Research.” The Guardian, September 15, 2022.

AAA (American Anthropological Association) Style

The American Anthropological Association (AAA) style is commonly used in anthropology research papers and journals. Here are the different reference formats in AAA style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. Book Title. Place of Publication: Publisher.

Example : Smith, John. 2019. The Anthropology of Food. New York: Routledge.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. “Article Title.” Journal Title volume, no. issue: page range.

Example : Garcia, Carlos. 2021. “The Role of Ethics in Anthropology.” American Anthropologist 123, no. 2: 237-251.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. “Chapter Title.” In Book Title, edited by Editor’s Name, page range. Place of Publication: Publisher.

Example: Lee, Mary. 2018. “Feminism in Anthropology.” In The Oxford Handbook of Feminism, edited by Jane Smith, 51-69. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. “Page Title.” Website Title. URL (accessed day month year).

Example : Jones, David. 2020. “The Importance of Learning Languages.” Oxford Language Center. https://www.oxfordlanguagecenter.com/importance-of-learning-languages/ (accessed January 3, 2023).

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. “Title of Dissertation/Thesis.” PhD diss., University Name.

Example : Brown, Susan. 2022. “The Art of Storytelling in Anthropology.” PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. “Article Title.” Newspaper Title, Month Day.

Example : Robinson, Andrew. 2021. “New Developments in Anthropology Research.” The Guardian, September 15.

AIP (American Institute of Physics) Style

The American Institute of Physics (AIP) style is commonly used in physics research papers and journals. Here are the different reference formats in AIP style:

Example : Johnson, S. D. 2021. “Quantum Computing and Information.” Journal of Applied Physics 129, no. 4: 043102.

Example : Feynman, Richard. 2018. The Feynman Lectures on Physics. New York: Basic Books.

Example : Jones, David. 2020. “The Future of Quantum Computing.” In The Handbook of Physics, edited by John Smith, 125-136. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Conference proceedings citation

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. “Title of Paper.” Proceedings of Conference Name, date and location: page range. Place of Publication: Publisher.

Example : Chen, Wei. 2019. “The Applications of Nanotechnology in Solar Cells.” Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Nanotechnology, July 15-17, Tokyo, Japan: 224-229. New York: AIP Publishing.

Example : American Institute of Physics. 2022. “About AIP Publishing.” AIP Publishing. https://publishing.aip.org/about-aip-publishing/ (accessed January 3, 2023).

Patent citation

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. Patent Number.

Example : Smith, John. 2018. US Patent 9,873,644.

References Writing Guide

Here are some general guidelines for writing references:

- Follow the citation style guidelines: Different disciplines and journals may require different citation styles (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago). It is important to follow the specific guidelines for the citation style required.

- Include all necessary information : Each citation should include enough information for readers to locate the source. For example, a journal article citation should include the author(s), title of the article, journal title, volume number, issue number, page numbers, and publication year.

- Use proper formatting: Citation styles typically have specific formatting requirements for different types of sources. Make sure to follow the proper formatting for each citation.

- Order citations alphabetically: If listing multiple sources, they should be listed alphabetically by the author’s last name.

- Be consistent: Use the same citation style throughout the entire paper or project.

- Check for accuracy: Double-check all citations to ensure accuracy, including correct spelling of author names and publication information.

- Use reputable sources: When selecting sources to cite, choose reputable and authoritative sources. Avoid sources that are biased or unreliable.

- Include all sources: Make sure to include all sources used in the research, including those that were not directly quoted but still informed the work.

- Use online tools : There are online tools available (e.g., citation generators) that can help with formatting and organizing references.

Purpose of References in Research

References in research serve several purposes:

- To give credit to the original authors or sources of information used in the research. It is important to acknowledge the work of others and avoid plagiarism.

- To provide evidence for the claims made in the research. References can support the arguments, hypotheses, or conclusions presented in the research by citing relevant studies, data, or theories.

- To allow readers to find and verify the sources used in the research. References provide the necessary information for readers to locate and access the sources cited in the research, which allows them to evaluate the quality and reliability of the information presented.

- To situate the research within the broader context of the field. References can show how the research builds on or contributes to the existing body of knowledge, and can help readers to identify gaps in the literature that the research seeks to address.

Importance of References in Research

References play an important role in research for several reasons:

- Credibility : By citing authoritative sources, references lend credibility to the research and its claims. They provide evidence that the research is based on a sound foundation of knowledge and has been carefully researched.

- Avoidance of Plagiarism : References help researchers avoid plagiarism by giving credit to the original authors or sources of information. This is important for ethical reasons and also to avoid legal repercussions.

- Reproducibility : References allow others to reproduce the research by providing detailed information on the sources used. This is important for verification of the research and for others to build on the work.

- Context : References provide context for the research by situating it within the broader body of knowledge in the field. They help researchers to understand where their work fits in and how it builds on or contributes to existing knowledge.

- Evaluation : References provide a means for others to evaluate the research by allowing them to assess the quality and reliability of the sources used.

Advantages of References in Research

There are several advantages of including references in research:

- Acknowledgment of Sources: Including references gives credit to the authors or sources of information used in the research. This is important to acknowledge the original work and avoid plagiarism.

- Evidence and Support : References can provide evidence to support the arguments, hypotheses, or conclusions presented in the research. This can add credibility and strength to the research.

- Reproducibility : References provide the necessary information for others to reproduce the research. This is important for the verification of the research and for others to build on the work.

- Context : References can help to situate the research within the broader body of knowledge in the field. This helps researchers to understand where their work fits in and how it builds on or contributes to existing knowledge.

- Evaluation : Including references allows others to evaluate the research by providing a means to assess the quality and reliability of the sources used.

- Ongoing Conversation: References allow researchers to engage in ongoing conversations and debates within their fields. They can show how the research builds on or contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

How to Do Market Research: The Complete Guide

Learn how to do market research with this step-by-step guide, complete with templates, tools and real-world examples.

Access best-in-class company data

Get trusted first-party funding data, revenue data and firmographics

What are your customers’ needs? How does your product compare to the competition? What are the emerging trends and opportunities in your industry? If these questions keep you up at night, it’s time to conduct market research.

Market research plays a pivotal role in your ability to stay competitive and relevant, helping you anticipate shifts in consumer behavior and industry dynamics. It involves gathering these insights using a wide range of techniques, from surveys and interviews to data analysis and observational studies.

In this guide, we’ll explore why market research is crucial, the various types of market research, the methods used in data collection, and how to effectively conduct market research to drive informed decision-making and success.

What is market research?

Market research is the systematic process of gathering, analyzing and interpreting information about a specific market or industry. The purpose of market research is to offer valuable insight into the preferences and behaviors of your target audience, and anticipate shifts in market trends and the competitive landscape. This information helps you make data-driven decisions, develop effective strategies for your business, and maximize your chances of long-term growth.

Why is market research important?

By understanding the significance of market research, you can make sure you’re asking the right questions and using the process to your advantage. Some of the benefits of market research include:

- Informed decision-making: Market research provides you with the data and insights you need to make smart decisions for your business. It helps you identify opportunities, assess risks and tailor your strategies to meet the demands of the market. Without market research, decisions are often based on assumptions or guesswork, leading to costly mistakes.

- Customer-centric approach: A cornerstone of market research involves developing a deep understanding of customer needs and preferences. This gives you valuable insights into your target audience, helping you develop products, services and marketing campaigns that resonate with your customers.

- Competitive advantage: By conducting market research, you’ll gain a competitive edge. You’ll be able to identify gaps in the market, analyze competitor strengths and weaknesses, and position your business strategically. This enables you to create unique value propositions, differentiate yourself from competitors, and seize opportunities that others may overlook.

- Risk mitigation: Market research helps you anticipate market shifts and potential challenges. By identifying threats early, you can proactively adjust their strategies to mitigate risks and respond effectively to changing circumstances. This proactive approach is particularly valuable in volatile industries.

- Resource optimization: Conducting market research allows organizations to allocate their time, money and resources more efficiently. It ensures that investments are made in areas with the highest potential return on investment, reducing wasted resources and improving overall business performance.

- Adaptation to market trends: Markets evolve rapidly, driven by technological advancements, cultural shifts and changing consumer attitudes. Market research ensures that you stay ahead of these trends and adapt your offerings accordingly so you can avoid becoming obsolete.

As you can see, market research empowers businesses to make data-driven decisions, cater to customer needs, outperform competitors, mitigate risks, optimize resources and stay agile in a dynamic marketplace. These benefits make it a huge industry; the global market research services market is expected to grow from $76.37 billion in 2021 to $108.57 billion in 2026 . Now, let’s dig into the different types of market research that can help you achieve these benefits.

Types of market research

- Qualitative research

- Quantitative research

- Exploratory research

- Descriptive research

- Causal research

- Cross-sectional research

- Longitudinal research

Despite its advantages, 23% of organizations don’t have a clear market research strategy. Part of developing a strategy involves choosing the right type of market research for your business goals. The most commonly used approaches include:

1. Qualitative research

Qualitative research focuses on understanding the underlying motivations, attitudes and perceptions of individuals or groups. It is typically conducted through techniques like in-depth interviews, focus groups and content analysis — methods we’ll discuss further in the sections below. Qualitative research provides rich, nuanced insights that can inform product development, marketing strategies and brand positioning.

2. Quantitative research

Quantitative research, in contrast to qualitative research, involves the collection and analysis of numerical data, often through surveys, experiments and structured questionnaires. This approach allows for statistical analysis and the measurement of trends, making it suitable for large-scale market studies and hypothesis testing. While it’s worthwhile using a mix of qualitative and quantitative research, most businesses prioritize the latter because it is scientific, measurable and easily replicated across different experiments.

3. Exploratory research

Whether you’re conducting qualitative or quantitative research or a mix of both, exploratory research is often the first step. Its primary goal is to help you understand a market or problem so you can gain insights and identify potential issues or opportunities. This type of market research is less structured and is typically conducted through open-ended interviews, focus groups or secondary data analysis. Exploratory research is valuable when entering new markets or exploring new product ideas.

4. Descriptive research

As its name implies, descriptive research seeks to describe a market, population or phenomenon in detail. It involves collecting and summarizing data to answer questions about audience demographics and behaviors, market size, and current trends. Surveys, observational studies and content analysis are common methods used in descriptive research.

5. Causal research

Causal research aims to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables. It investigates whether changes in one variable result in changes in another. Experimental designs, A/B testing and regression analysis are common causal research methods. This sheds light on how specific marketing strategies or product changes impact consumer behavior.

6. Cross-sectional research

Cross-sectional market research involves collecting data from a sample of the population at a single point in time. It is used to analyze differences, relationships or trends among various groups within a population. Cross-sectional studies are helpful for market segmentation, identifying target audiences and assessing market trends at a specific moment.

7. Longitudinal research

Longitudinal research, in contrast to cross-sectional research, collects data from the same subjects over an extended period. This allows for the analysis of trends, changes and developments over time. Longitudinal studies are useful for tracking long-term developments in consumer preferences, brand loyalty and market dynamics.

Each type of market research has its strengths and weaknesses, and the method you choose depends on your specific research goals and the depth of understanding you’re aiming to achieve. In the following sections, we’ll delve into primary and secondary research approaches and specific research methods.

Primary vs. secondary market research

Market research of all types can be broadly categorized into two main approaches: primary research and secondary research. By understanding the differences between these approaches, you can better determine the most appropriate research method for your specific goals.

Primary market research

Primary research involves the collection of original data straight from the source. Typically, this involves communicating directly with your target audience — through surveys, interviews, focus groups and more — to gather information. Here are some key attributes of primary market research:

- Customized data: Primary research provides data that is tailored to your research needs. You design a custom research study and gather information specific to your goals.

- Up-to-date insights: Because primary research involves communicating with customers, the data you collect reflects the most current market conditions and consumer behaviors.

- Time-consuming and resource-intensive: Despite its advantages, primary research can be labor-intensive and costly, especially when dealing with large sample sizes or complex study designs. Whether you hire a market research consultant, agency or use an in-house team, primary research studies consume a large amount of resources and time.

Secondary market research

Secondary research, on the other hand, involves analyzing data that has already been compiled by third-party sources, such as online research tools, databases, news sites, industry reports and academic studies.

Here are the main characteristics of secondary market research:

- Cost-effective: Secondary research is generally more cost-effective than primary research since it doesn’t require building a research plan from scratch. You and your team can look at databases, websites and publications on an ongoing basis, without needing to design a custom experiment or hire a consultant.

- Leverages multiple sources: Data tools and software extract data from multiple places across the web, and then consolidate that information within a single platform. This means you’ll get a greater amount of data and a wider scope from secondary research.

- Quick to access: You can access a wide range of information rapidly — often in seconds — if you’re using online research tools and databases. Because of this, you can act on insights sooner, rather than taking the time to develop an experiment.

So, when should you use primary vs. secondary research? In practice, many market research projects incorporate both primary and secondary research to take advantage of the strengths of each approach.

One rule of thumb is to focus on secondary research to obtain background information, market trends or industry benchmarks. It is especially valuable for conducting preliminary research, competitor analysis, or when time and budget constraints are tight. Then, if you still have knowledge gaps or need to answer specific questions unique to your business model, use primary research to create a custom experiment.

Market research methods

- Surveys and questionnaires

- Focus groups

- Observational research

- Online research tools

- Experiments

- Content analysis

- Ethnographic research

How do primary and secondary research approaches translate into specific research methods? Let’s take a look at the different ways you can gather data:

1. Surveys and questionnaires

Surveys and questionnaires are popular methods for collecting structured data from a large number of respondents. They involve a set of predetermined questions that participants answer. Surveys can be conducted through various channels, including online tools, telephone interviews and in-person or online questionnaires. They are useful for gathering quantitative data and assessing customer demographics, opinions, preferences and needs. On average, customer surveys have a 33% response rate , so keep that in mind as you consider your sample size.

2. Interviews

Interviews are in-depth conversations with individuals or groups to gather qualitative insights. They can be structured (with predefined questions) or unstructured (with open-ended discussions). Interviews are valuable for exploring complex topics, uncovering motivations and obtaining detailed feedback.

3. Focus groups

The most common primary research methods are in-depth webcam interviews and focus groups. Focus groups are a small gathering of participants who discuss a specific topic or product under the guidance of a moderator. These discussions are valuable for primary market research because they reveal insights into consumer attitudes, perceptions and emotions. Focus groups are especially useful for idea generation, concept testing and understanding group dynamics within your target audience.

4. Observational research

Observational research involves observing and recording participant behavior in a natural setting. This method is particularly valuable when studying consumer behavior in physical spaces, such as retail stores or public places. In some types of observational research, participants are aware you’re watching them; in other cases, you discreetly watch consumers without their knowledge, as they use your product. Either way, observational research provides firsthand insights into how people interact with products or environments.

5. Online research tools

You and your team can do your own secondary market research using online tools. These tools include data prospecting platforms and databases, as well as online surveys, social media listening, web analytics and sentiment analysis platforms. They help you gather data from online sources, monitor industry trends, track competitors, understand consumer preferences and keep tabs on online behavior. We’ll talk more about choosing the right market research tools in the sections that follow.

6. Experiments

Market research experiments are controlled tests of variables to determine causal relationships. While experiments are often associated with scientific research, they are also used in market research to assess the impact of specific marketing strategies, product features, or pricing and packaging changes.

7. Content analysis

Content analysis involves the systematic examination of textual, visual or audio content to identify patterns, themes and trends. It’s commonly applied to customer reviews, social media posts and other forms of online content to analyze consumer opinions and sentiments.

8. Ethnographic research

Ethnographic research immerses researchers into the daily lives of consumers to understand their behavior and culture. This method is particularly valuable when studying niche markets or exploring the cultural context of consumer choices.

How to do market research

- Set clear objectives

- Identify your target audience

- Choose your research methods

- Use the right market research tools

- Collect data

- Analyze data

- Interpret your findings

- Identify opportunities and challenges

- Make informed business decisions

- Monitor and adapt

Now that you have gained insights into the various market research methods at your disposal, let’s delve into the practical aspects of how to conduct market research effectively. Here’s a quick step-by-step overview, from defining objectives to monitoring market shifts.

1. Set clear objectives

When you set clear and specific goals, you’re essentially creating a compass to guide your research questions and methodology. Start by precisely defining what you want to achieve. Are you launching a new product and want to understand its viability in the market? Are you evaluating customer satisfaction with a product redesign?

Start by creating SMART goals — objectives that are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound. Not only will this clarify your research focus from the outset, but it will also help you track progress and benchmark your success throughout the process.

You should also consult with key stakeholders and team members to ensure alignment on your research objectives before diving into data collecting. This will help you gain diverse perspectives and insights that will shape your research approach.

2. Identify your target audience

Next, you’ll need to pinpoint your target audience to determine who should be included in your research. Begin by creating detailed buyer personas or stakeholder profiles. Consider demographic factors like age, gender, income and location, but also delve into psychographics, such as interests, values and pain points.

The more specific your target audience, the more accurate and actionable your research will be. Additionally, segment your audience if your research objectives involve studying different groups, such as current customers and potential leads.

If you already have existing customers, you can also hold conversations with them to better understand your target market. From there, you can refine your buyer personas and tailor your research methods accordingly.

3. Choose your research methods

Selecting the right research methods is crucial for gathering high-quality data. Start by considering the nature of your research objectives. If you’re exploring consumer preferences, surveys and interviews can provide valuable insights. For in-depth understanding, focus groups or observational research might be suitable. Consider using a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods to gain a well-rounded perspective.

You’ll also need to consider your budget. Think about what you can realistically achieve using the time and resources available to you. If you have a fairly generous budget, you may want to try a mix of primary and secondary research approaches. If you’re doing market research for a startup , on the other hand, chances are your budget is somewhat limited. If that’s the case, try addressing your goals with secondary research tools before investing time and effort in a primary research study.

4. Use the right market research tools

Whether you’re conducting primary or secondary research, you’ll need to choose the right tools. These can help you do anything from sending surveys to customers to monitoring trends and analyzing data. Here are some examples of popular market research tools:

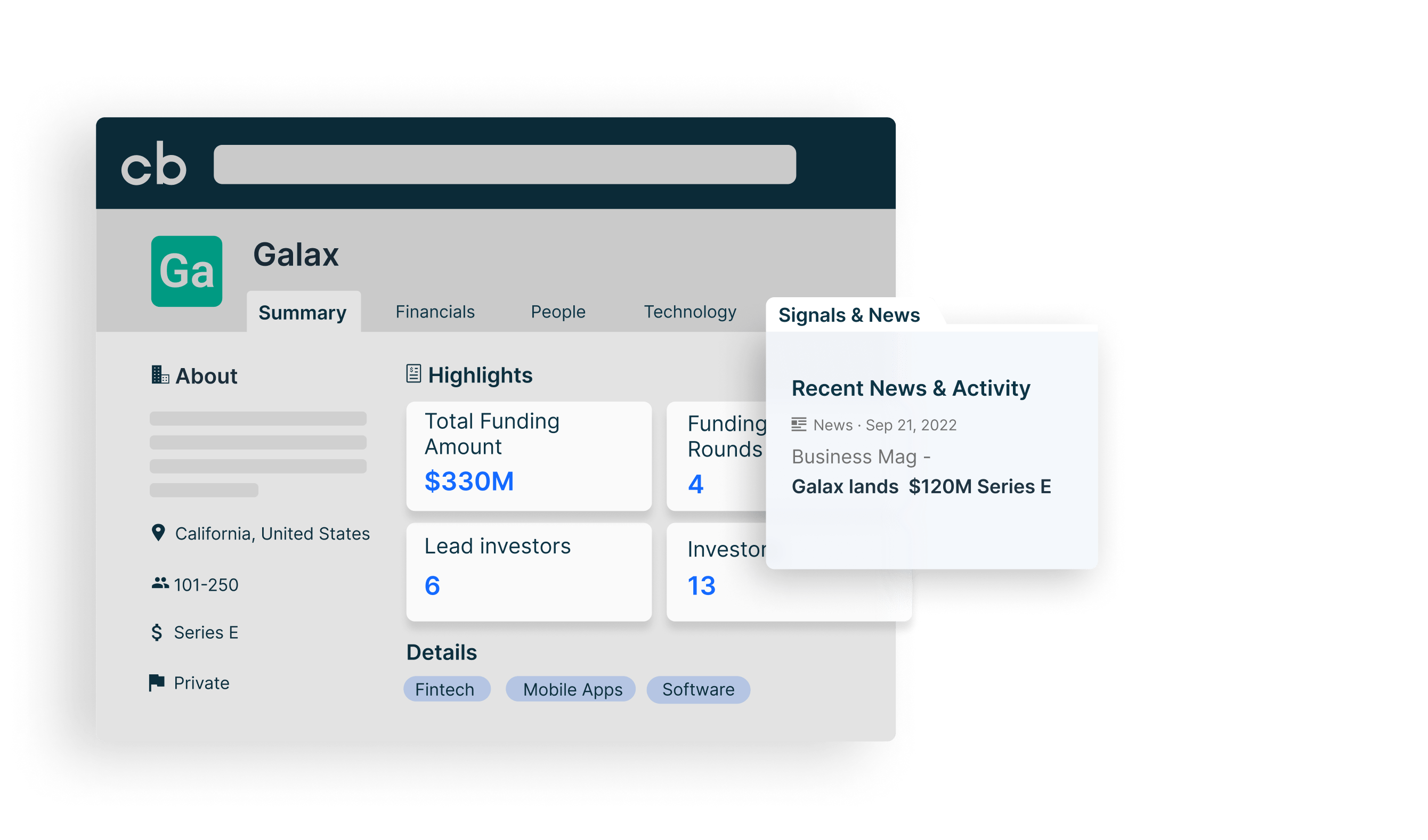

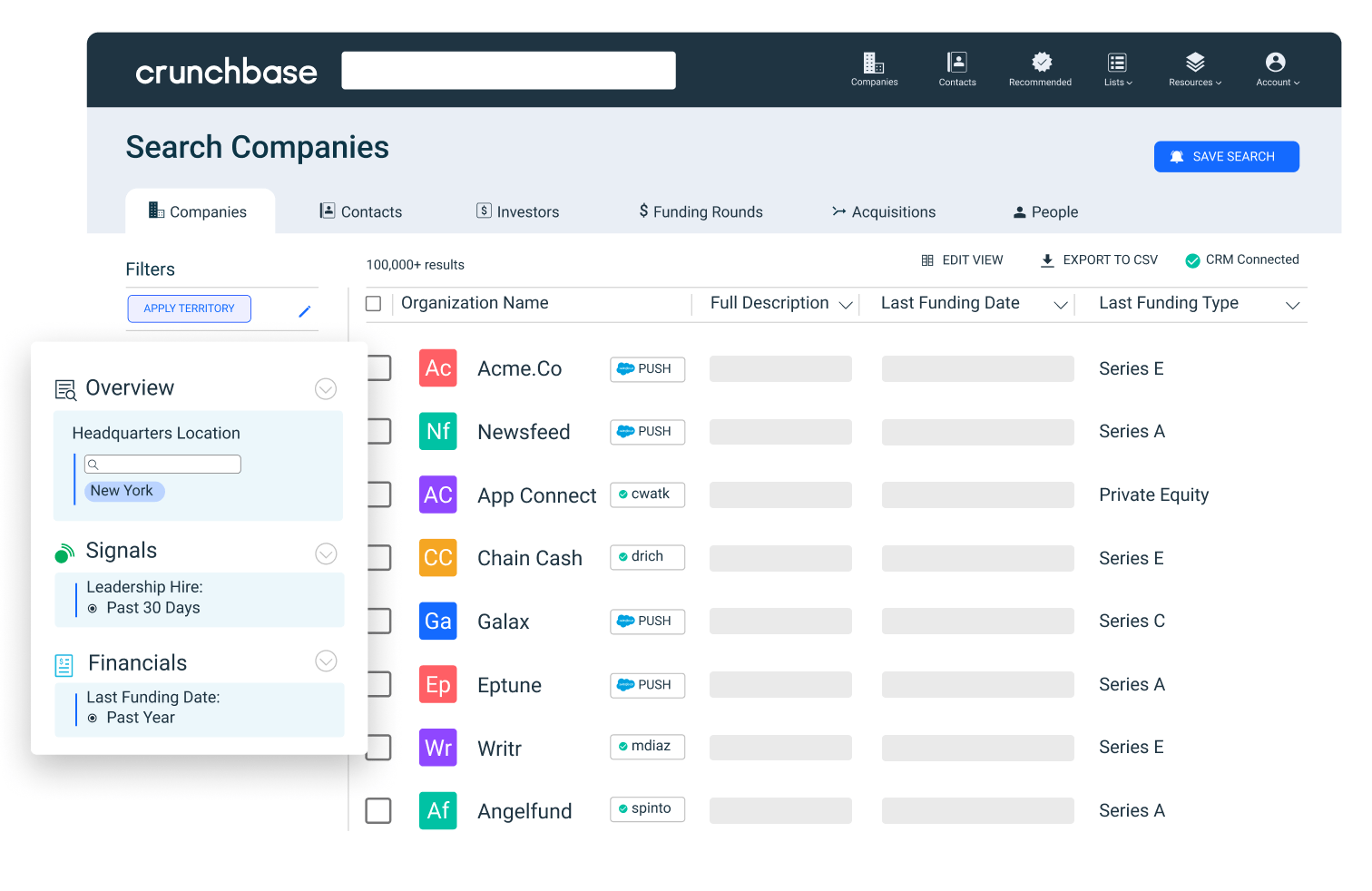

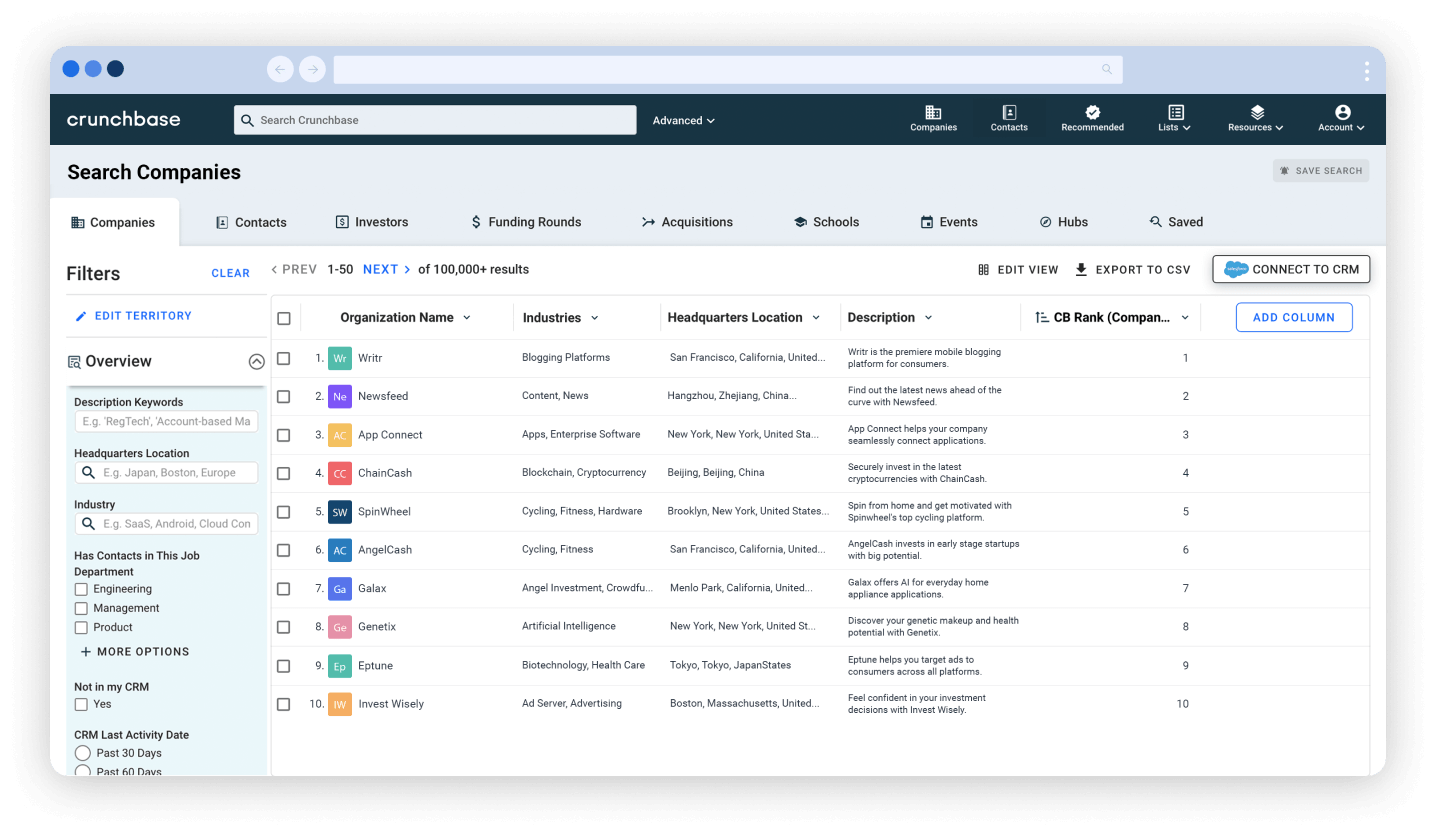

- Market research software: Crunchbase is a platform that provides best-in-class company data, making it valuable for market research on growing companies and industries. You can use Crunchbase to access trusted, first-party funding data, revenue data, news and firmographics, enabling you to monitor industry trends and understand customer needs.

- Survey and questionnaire tools: SurveyMonkey is a widely used online survey platform that allows you to create, distribute and analyze surveys. Google Forms is a free tool that lets you create surveys and collect responses through Google Drive.

- Data analysis software: Microsoft Excel and Google Sheets are useful for conducting statistical analyses. SPSS is a powerful statistical analysis software used for data processing, analysis and reporting.

- Social listening tools: Brandwatch is a social listening and analytics platform that helps you monitor social media conversations, track sentiment and analyze trends. Mention is a media monitoring tool that allows you to track mentions of your brand, competitors and keywords across various online sources.

- Data visualization platforms: Tableau is a data visualization tool that helps you create interactive and shareable dashboards and reports. Power BI by Microsoft is a business analytics tool for creating interactive visualizations and reports.

5. Collect data

There’s an infinite amount of data you could be collecting using these tools, so you’ll need to be intentional about going after the data that aligns with your research goals. Implement your chosen research methods, whether it’s distributing surveys, conducting interviews or pulling from secondary research platforms. Pay close attention to data quality and accuracy, and stick to a standardized process to streamline data capture and reduce errors.

6. Analyze data

Once data is collected, you’ll need to analyze it systematically. Use statistical software or analysis tools to identify patterns, trends and correlations. For qualitative data, employ thematic analysis to extract common themes and insights. Visualize your findings with charts, graphs and tables to make complex data more understandable.

If you’re not proficient in data analysis, consider outsourcing or collaborating with a data analyst who can assist in processing and interpreting your data accurately.

7. Interpret your findings

Interpreting your market research findings involves understanding what the data means in the context of your objectives. Are there significant trends that uncover the answers to your initial research questions? Consider the implications of your findings on your business strategy. It’s essential to move beyond raw data and extract actionable insights that inform decision-making.

Hold a cross-functional meeting or workshop with relevant team members to collectively interpret the findings. Different perspectives can lead to more comprehensive insights and innovative solutions.

8. Identify opportunities and challenges

Use your research findings to identify potential growth opportunities and challenges within your market. What segments of your audience are underserved or overlooked? Are there emerging trends you can capitalize on? Conversely, what obstacles or competitors could hinder your progress?

Lay out this information in a clear and organized way by conducting a SWOT analysis, which stands for strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. Jot down notes for each of these areas to provide a structured overview of gaps and hurdles in the market.

9. Make informed business decisions

Market research is only valuable if it leads to informed decisions for your company. Based on your insights, devise actionable strategies and initiatives that align with your research objectives. Whether it’s refining your product, targeting new customer segments or adjusting pricing, ensure your decisions are rooted in the data.

At this point, it’s also crucial to keep your team aligned and accountable. Create an action plan that outlines specific steps, responsibilities and timelines for implementing the recommendations derived from your research.

10. Monitor and adapt

Market research isn’t a one-time activity; it’s an ongoing process. Continuously monitor market conditions, customer behaviors and industry trends. Set up mechanisms to collect real-time data and feedback. As you gather new information, be prepared to adapt your strategies and tactics accordingly. Regularly revisiting your research ensures your business remains agile and reflects changing market dynamics and consumer preferences.

Online market research sources

As you go through the steps above, you’ll want to turn to trusted, reputable sources to gather your data. Here’s a list to get you started:

- Crunchbase: As mentioned above, Crunchbase is an online platform with an extensive dataset, allowing you to access in-depth insights on market trends, consumer behavior and competitive analysis. You can also customize your search options to tailor your research to specific industries, geographic regions or customer personas.

- Academic databases: Academic databases, such as ProQuest and JSTOR , are treasure troves of scholarly research papers, studies and academic journals. They offer in-depth analyses of various subjects, including market trends, consumer preferences and industry-specific insights. Researchers can access a wealth of peer-reviewed publications to gain a deeper understanding of their research topics.