Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education pp 15–25 Cite as

Action Research on Sustainable Development

- Karin Tschiggerl 2

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 11 October 2019

183 Accesses

Download reference work entry PDF

Action research (AR) can be defined as a systematic type of research enabling “people to find effective solutions to problems they confront in their everyday lives” (Stringer 2013 ). Based on a reflective process on a cycle of actions, a particular problematic situation can be addressed. The idea behind is that by doing so changes occur within the setting, the participants, as well as the researcher (Herr and Anderson 2005 ).

Introduction

Since the rise of the international discussion starting with the publication of the Brundtland report “Our common future” in 1987 (WCED 1987 ), many approaches and programs have been initiated toward a sustainable development. “Sustainable development is a process with the clear vision to change our societies from unsustainable to sustainable” (Baumgartner 2011 ). Nonetheless, many sustainability-related problems are still existent or even faced by increasing negative impacts. This leads to the assumption of a lacking awareness, ability, and/or willingness to adopt the necessary change. In this context, Wilber ( 2000 ) provides an analysis of factors that limit change: (1) individual subjective factors (values, worldview, etc.), (2) individual objective factors (sociodemographics, knowledge, etc.), (3) collective subjective factors (culture, shared norms, etc.), and (4) collective objective factors (political, economic, technological, etc.). Given the necessity of change by overcoming these barriers, Ballard ( 2005 ) identifies three conditions that are required in responding to the challenge of sustainable development: (a) awareness of what happens and what is required; (b) agency, which means responding in a subjective meaningful way; and (c) association or collaboration with others. To implement change it is necessary to work across all of these conditions, whereby this requires the key process of (d) action and reflection. In the light of permanent learning needs for sustainable development, action and reflection processes are seen as central factors.

Sustainable development can be seen as a complex, dynamic process of further development and learning toward better solutions for existing challenges, whereby the creation of awareness for sustainability leads over a deep individual and organizational change (Tschiggerl and Fresner 2008 ). As change concepts can be manifold, Egmose ( 2015 ) considers sustainable change as equally radical and democratic, which means that unsustainable current ways of living have to be transformed by “democratic experiments” that transcend present realities. Baumgartner and Korhonen ( 2010 ) state that there is an urgent need for taking actions for sustainable development. In this context science is required to help society to identify and solve sustainability problems using adequate research approaches.

Considering these limitations and aspects to implement actions for sustainable development, this entry presents action research as a viable method toward solving sustainability-related issues. Therefore, it is important to understand the methodological basics of action research (AR), which will be presented and discussed regarding potential difficulties and critics. Especially the AR process will be explained in detail to retrace how change can be achieved. Following, several examples of action research applied to sustainability-related issues will be presented to recognize the usefulness of this type of investigation. The last chapter concludes why action research can help to foster and implement real change toward sustainable development.

Action Research as a Collaborative Approach Towards Sustainable Development

As stated by several authors (Ballard 2005 ; Reason and Bradbury 2006 ; Park 2006 ; Zuber-Skerrit 2012 ; Egmose 2015 ), the action research methodology offers a useful approach for understanding and working with complex socio-ecological systems to encourage collaborations and participation aiming at intervention, development, and change (Manring 2014 ). Therefore, traditional research and development strategies have to be supplemented by human initiatives, innovations, and actions resulting from participative and democratic processes that allow new knowledge creation to solve problems (Zuber-Skerrit 2012 ).

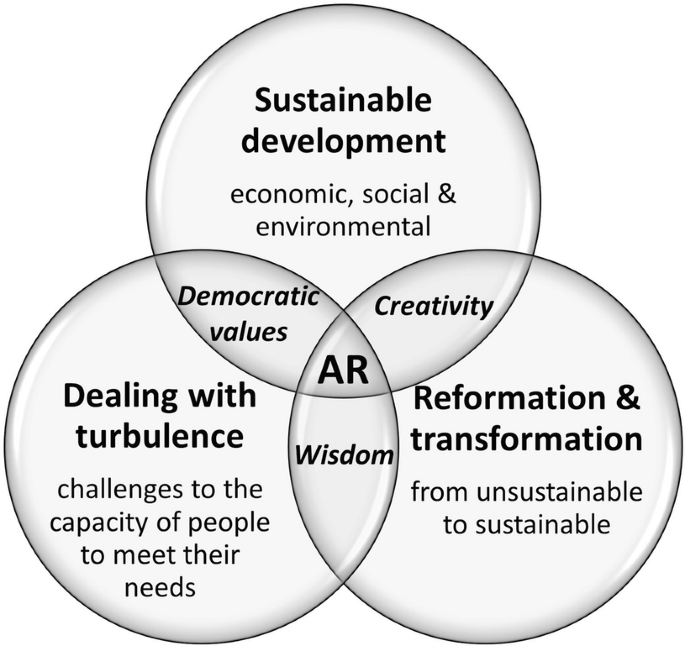

Zuber-Skerrit et al. ( 2013 ) describe the democratic values of collaboration and participation as the essential objectives for action research. Therefore they propose a framework of participatory action learning and action research (Fig. 1 ) to explore possible ways to reach a transformation toward sustainable development.

Action research for sustainable development. (Source: Adapted from Zuber-Skerrit et al. 2013 )

According to the authors, democratic values can lead to wisdom, which can be seen as a social construct of deep understanding of relationships and the ability to identify the most meaningful action to solve problems and challenges. To achieve a reformation and transformation of current (unsustainable) practices, it requires the extension of wisdom to creativity and innovation. This can be generated by transformed – in the sense of aware – individuals or groups participating in action research processes (Zuber-Skerrit et al. 2013 ).

The following chapter describes the methodological aspects of action research and gives an overview of characteristics, the research process, and criteria to assess the quality of AR studies.

The Methodology of Action Research

Action research is a research approach that aims at the execution of an action and the generation of knowledge and a theory about it while the activity evolutes. The results are as well action and research outcome, whereas the objective of traditional approaches is solely the creation of knowledge (Coghlan and Brannick 2014 ). Action research can be explained as a cyclical process of diagnosis, action planning, action taking, evaluation, and specified learning. The focus is rather on active research than on research about action, where the members of the system being investigated are actively participating in the process (Middel et al. 2005 ). Greenwood ( 2007 ) describes the approach as follows:

Action research is neither a method nor a technique; it is an approach to living the world that includes the creation of areas for collaborative learning and the design, enactment and evaluation of liberating actions … it combines action and research, reflection and action in an ongoing cycle of cogenerative knowledge.

The origins and the basic idea can be traced back to the psychologist Kurt Lewin. He proposed a participative action research paradigm where the attendees not only generate but also apply knowledge during the research process. Thus, AR can be seen as a democratic process (Skinner 2017 ).

To classify research as action research, the following five elements should be contained (Meyers 2013 ):

Aim and benefit: While scientific investigations aim at the expansion of general knowledge, AR targets the knowledge acquisition and solution of a practical problem. The focus is on transformation and change toward a positive value for the society.

Contextual focus: As the action researcher deals with real-life problems, the context has to be broader than in case study research.

Data relying on change and construction of knowledge: AR is change oriented; thus, it requires data that detect the consequences of an intended change. Action researchers need therefore continual and systematic collected data, which further require an interpretation to generate knowledge from it.

Participative research process: AR demands the active participation of those affected by the real-life problem and who “own” it. As AR is collaborative, the concerned should at least be involved in selecting the problem, identifying solutions, and validating results.

Knowledge dissemination: AR has to be documented and disseminated according to accepted scientific practices to be considered as research. This means that a research topic has to deal with existing literature to generate general knowledge. This falls to the action researcher.

Types of Action Research

Zuber-Skerrit and Perry ( 2002 ) as well as Skinner ( 2017 ) distinguish between three types of AR: Type 1 requires an external expert as support due to the complexity of a problem. Type 2 can involve a facilitator, but the focus is on individual power of equal participants. In type 3 the power is completely within the group. Table 1 gives an overview of AR types and their main characteristics.

The system boarders between formal (technical) and practical action research are stringent; only emancipatory AR uses all technical and organizational competences. Thus, this type relates most to organizational learning (Zuber-Skerrit and Perry 2002 ). According to Carr and Kemmis ( 1986 ), only type 3 can be marked as real AR as it fulfills the minimum requirements: strategic action determines the content; the proceeding includes planning, action, observation, and reflection; all phases of research activities integrate participation and collaboration.

Independent from the type of AR, three basic topics are handled in every definition and classification: empowerment of participants, adoption of knowledge, and social change (Masters 1995 ). However, contemporary action research is affected by a great variety (Meyers 2013 ).

The Action Research Process

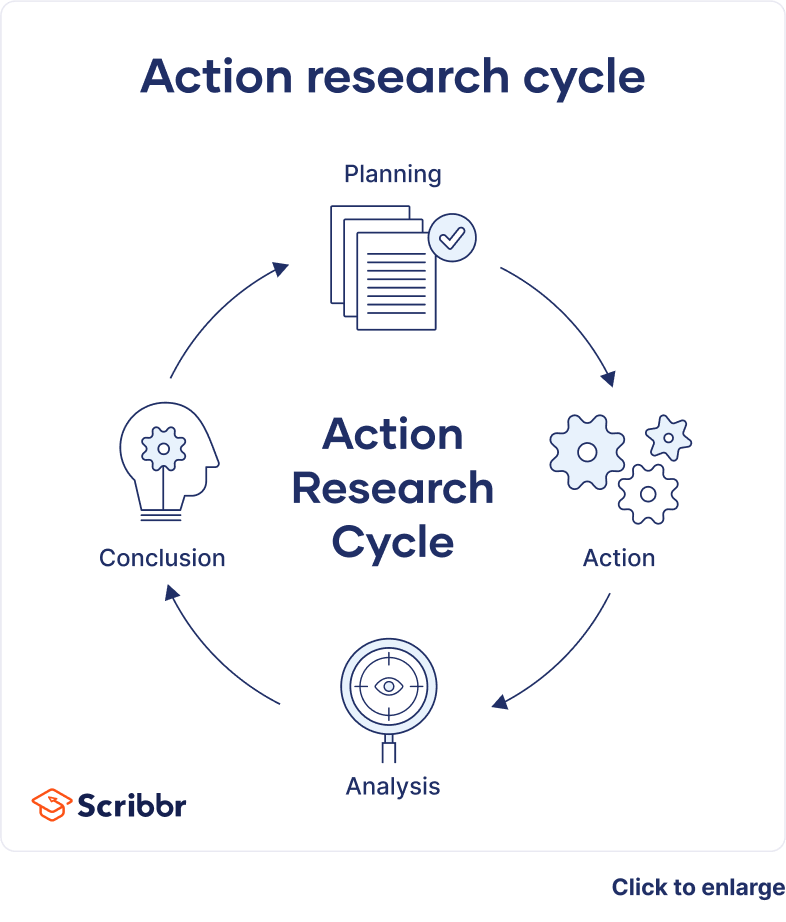

In its simplest form after Lewin ( 1997 [1946]), the AR process contains a pre-step and three core activities: planning, action, and detection of facts. The objective is defined in the pre-step. Planning includes in general that there is a plan and the decision regarding the first step. Acting means to conduct the first step, and detection of facts deals with the evaluation of what was learnt. This builds the basis for the next step and an ongoing spiral of planning – acting – evaluating.

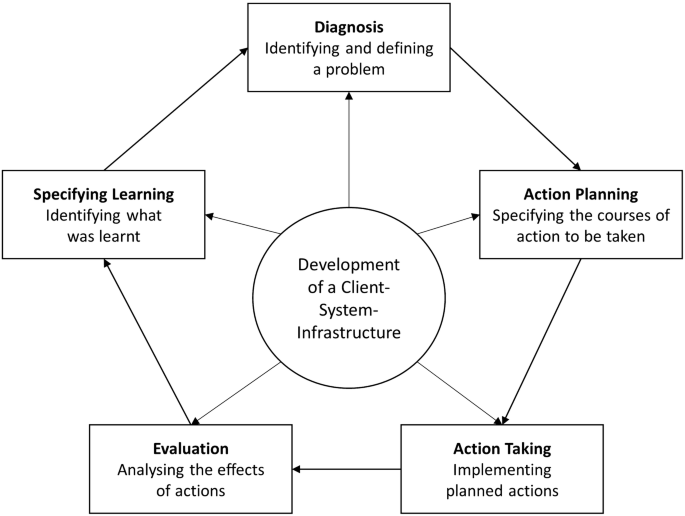

Susman and Evered ( 1978 ) describe AR as cyclical process with five steps: diagnosis, action planning, implementing action, evaluation, and definition of learnings (Fig. 2 ). The infrastructure within a client system, which can be described as the research context, and the action researcher facilitate and regulate some or all phases together.

Cyclical process of action research. (Source: Susman and Evered 1978 )

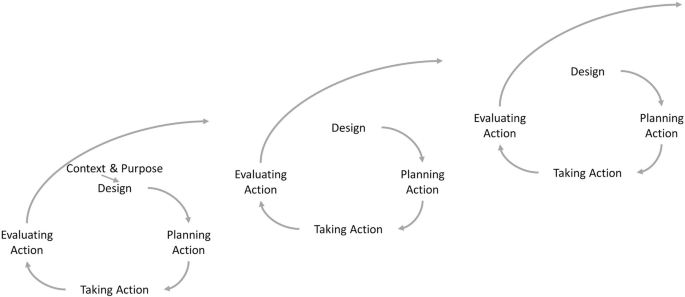

Coghlan and Brannick ( 2014 ) propose an AR cycle consisting of a pre-step (context and aim) and four basic steps: design, action planning, action taking, and evaluation. The emphasis is on the first step regarding the design where stakeholders construct the problem and relevant questions in the form of a dialogue. They have to be articulated carefully as they are as well practical and theoretical foundation for the actions. After planning and taking those actions, the results should be evaluated regarding the following questions:

Was the initial design adequate?

Did the conducted actions correspond to the design?

Were the actions conducted adequately?

What will be implemented within the next cycle of design, planning, and action?

In this manner the cycles will be continued and form a spiral, as illustrated in Fig. 3 .

Spiral of action research cycles. (Source: Coghlan and Brannick 2014 )

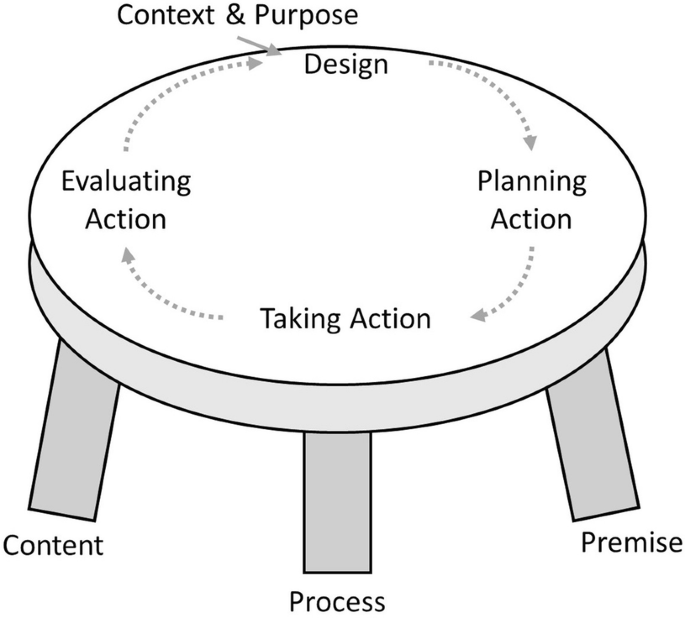

In every AR project, two cycles are running in parallel. The first cycle stands for the before mentioned, while the second one is a reflection cycle, evaluating the original AR cycle (Coghlan and Brannick 2014 ). Zuber-Skerrit and Perry ( 2002 ) describe this as the core and the thesis AR cycle. This means that as well the design, planning, implementation, and evaluation regarding the proceeding and learning within the project have to take place. Herewith, the action researcher can evaluate how steps are conducted and, if they are consistent, how the following steps shall be executed. Argyris ( 2003 ) argues that the investigation of AR cycles itself is essential for the development of applicable knowledge. It’s the dynamic of recurrent reflection that generates the learning process of the AR cycle. Thus, AR goes beyond trivial problem-solving and enables learning about learning, the so-called meta-learning. Coghlan and Brannick ( 2014 ) relate to three kinds of reflection in the AR process: reflection regarding the content, the processes, and the premises. Figure 4 illustrates the connections of reflection types as meta-cycle of core AR.

Meta-cycle of action research. (Source: Coghlan and Brannick 2014 )

Reflection regarding the content analyzes the framework, the planned and the implemented, as well as the evaluated. The design and how it is carried out in planning, implementation, and evaluation are the critical focus of the process reflection. Finally, reflection of premises analyzes unformulated and unconscious assumptions that affect the attitudes and behavior of participants. Hence, this meta-cycle is the continuous monitoring conducted in every cycle, whereby continuous learning will be enabled (Coghlan and Brannick 2014 ).

Quality of Action Research

Action research requires its own quality criteria and cannot be assessed according to those of positivist research. According to Coghlan and Brannick ( 2014 ), high-quality AR includes three relevant elements: a good story, thorough reflection, and the extrapolation of useful knowledge or theory by reflecting the story. Not more than with other research methods, also AR faces a risk regarding validity. To guarantee a valid proceeding, the action researcher has to implement the AR cycles and test own assumptions and inputs from a critical public. Thus, action research has to combine advocacy and investigation; in other words, it has to integrate conclusions, attributions, perceptions, and openness for evaluation and critics. This combination includes deductions from observable data and the creation of deductions that can be evaluated, with the aim to enable learning (Coghlan and Coghlan 2002 ).

In the context of sustainable development, Egmose ( 2015 ) argues that a methodology focusing on change requires notably a reflection on how to implement change in real life. Thus, the demands regarding reflexivity are particularly high as the challenge of sustainability exceeds perceived boundaries and classifications. This means, the simplifications made to categorize actual situations may hinder a comprehensive assessment of sustainability issues and its impacts.

Applying Action Research to Sustainability Issues

Zuber-Skerrit ( 2012 ) puts the aspects relevant to sustainable development down to those that are as well inherent to action research:

Engagement: The problem has to be identified and a need for change has to be observed.

Value-driven agendas and planned interventions: Actions have to be specified and planned.

Need for practical and sustainable change: Actions have to be implemented and reflected regarding their effects and impacts.

Support of organizations and individuals to ensure continuation of the process: The new generated knowledge has to be identified and experienced as a learning outcome that affects future problem-solving capabilities.

In that sense, both sustainable development and action research aims at identifying a need for change and to support it with both rigor and relevant research to enable practical solutions (Baumgartner 2011 ; Zuber-Skerrit 2012 ).

Literature shows a broad range of applications where an action research approach was used to answer various research questions resulting from “real-world” problems in different stakeholder environments. Table 2 gives an overview of selected cases from recent years where action research was chosen as the research method. The review of the selected literature includes the identified “real-world” problem, where a need for change of the current practice was identified. The action level specifies the involved actors, which can be described as the “owners” of the problem. As action research aims at generating a practical solution for a specified group or community and generating new knowledge, also the outcome expanding actual theory will be illustrated.

The essence out of these studies can be illustrated by a statement from Bradbury ( 2001 ): “Action research can be of significant value in building capacity for, and in the study of, efforts in support of sustainable development. Action researchers can help further the conversations already underway through giving a common language to many of the trans-sectoral initiatives that include people from the cultural and economic realms, and then further telling these stories, be it through publication channels (which require further theoretical reflection) or through convening forums for public conversation.” There are manifold shapes of problems and questions related to sustainable development. Documented approaches on how to develop solutions and implement them, while expanding existing knowledge and theory, can help to improve not only current practices but also transform systems in a wider sense toward sustainable development.

Critical Reflection on Action Research for Sustainable Development

From an epistemological perspective, a focus on sustainability includes scientists to acknowledge planetary boundaries and orientation toward an uncertain future, which has normative implications and is biased. Thus, researchers from both sustainability science and action research for sustainable development are questioned regarding their scientific objectivity. In this sense, action researchers in the pursuit of sustainability are not neutral analysts, whereby they are required to engage in self-inquiry and reflection (Wittmayer et al. 2013 ). This refers to the meta-cycle of action research which necessitates the careful reflection of the content, the processes, and the premises within projects (Coghlan and Brannick 2014 ).

One of the critics on AR is the popular belief that this method is nothing else than consulting disguised as research, which faces a serious problem for AR. Gummesson ( 2000 ) proposes four ways to distinguish AR from consulting:

Consultants working with AR approaches have to conduct investigations and documentations more thoroughly.

Researchers rely on theoretical consultants on empirical justifications.

Consultants have to work under tense time and budget restrictions.

Consulting is linear – order acceptance, analysis, action/intervention, order completion. In contrast, AR is cyclical – data acquisition, feedback to involved persons, data analysis, action planning, intervention, and evaluation followed by a next cycle.

Despite this differentiation, Velenturf and Purnell ( 2017 ) see consulting as one method to achieve commitment and collaboration within participatory approaches. Stakeholders should also be engaged in other levels of participation – from informing to full autonomy – which are appropriate to their influence and interest. Further, they conclude that radical and transformative change, as it is required for the transition from unsustainable to sustainable states (see also Zuber-Skerrit et al. ( 2013 )), demands participative processes. This shows several benefits regarding the quality, legitimacy, and efficiency of interventions:

Improvement of social inclusiveness and empowerment of stakeholders.

Promotion of social learning, whereby the connections between societal segments can be strengthened and adversarial relations can be transformed.

The quality of information and solutions can be improved due to their adaptation to specific contexts.

The acceptance and commitment to solutions can be increased.

Despite the positive effects of action research, it is a great challenge to researchers to conduct this kind of research approach in terms of their ability to deal with community spaces and possible power differences, ethical dilemmas, and conflicts (Wittmayer et al. 2013 ).

Conclusion and Outlook

The aim of action research is to improve practice while contributing to theory. Action research does not distinguish between research and action but is research through action. In contrast to traditional research approaches, action research is thus imprecise, uncertain, and possibly more volatile in its application (Coghlan and Coghlan 2002 ). A great number of applications from literature, as well as the statements of several authors, evidence the relevance of action research on sustainability-related issues. To lead social systems, which may be located at micro- or macro-levels, toward a sustainable development, coordinated change, cooperation, and collaboration are required from multiple actors across society. The role of academia can be to facilitate such processes through participatory action research in all sustainability-related fields (Velenturf and Purnell 2017 ). As concluded by Manring ( 2014 ), there is a clear need to educate and train students to participate as leaders and partners in sustainability initiatives, among others, by action research and practice.

Action research expects us to stop just going through the motions, doing what we’ve always done because we’ve done it, doing it the same way because we’ve always done it that way. Action researchers take a close look at what they are doing and act to make things better that they already are. Taking a closer look is action in and of itself and that research, that knowledge creation – any action taken based on that research – has the potential to transform the work that we do, the working conditions that we sweat under and, most importantly, the people who we are. (Coghlan and Brannick 2014 )

Especially in times of upheavals – political, social, economic, and technological – and on the threshold to a fourth industrial era, action research can make great contributions to shape and pursue this change in all its facings for the good of all involved in a sustainable way. The understanding of how this can be realized in the most sustainable way while adopting it in the forms of applied practices is the aim of any action research (Tschiggerl 2017 ). In the words of Zuber-Skerrit ( 2012 ), action research is a solution to and integration for problem-solving and sustainable development in a world of turbulence.

Cross-References

Innovative Approaches to Learning Sustainable Development

Deep Learning on Sustainable Development

Reflective Actions for Sustainable Development

Reflective Practice for Sustainable Development

Anderson F (2015) The development of rural sustainability using participatory action research: a case study from Guatemala. J Hum Resour Sustain Stud 3:28–33

Google Scholar

Argyris C (2003) Actionable knowledge. In: Tsoukas T, Knudsen C (eds) The Oxford handbook of organization theory. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 423–452

Ballard D (2005) Using learning processes to promote change for sustainable development. Action Res 3(2):135–156

Article Google Scholar

Baumgartner RJ (2011) Critical perspectives of sustainable development research and practice. J Clean Prod 19:783–786

Baumgartner RJ, Korhonen J (2010) Strategic thinking for sustainable development. Sustain Dev 18(2):71–75

Bolwig S, Ponte S, du Toit A, Riisgaard L, Halberg N (2008) Integrating poverty, gender and environmental concerns into value chain analysis: a conceptual framework and lessons for action research. Danish Institute for International Studies, Copenhagen

Bradbury H (2001) Learning with the natural step: action research to promote conversations for sustainable development. In: Reason P, Bradbury H (eds) Handbook of action research: participative inquiry and practice. Sage, London, pp 307–313

Bratt C (2011) Assessment of eco-labelling and green procurement from a strategic sustainability perspective. Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karlskrona

Burns H (2016) Learning sustainability leadership: an action research study of a graduate leadership course. Int J Scholarsh Teach Learn 10(2):8

Carr W, Kemmis S (1986) Becoming critical: education, knowledge, and action research. Falmer Press, London

Coghlan D, Brannick T (2014) Doing action research in your own organization. Sage, London

Coghlan P, Coghlan D (2002) Action research for operations management. Int J Oper Prod Manag 22(2):220–240

Egmose J (2015) Action research for sustainability. Ashgate, Farnham

Greenwood DJ (2007) Pragmatic action research. Int J Action Res 2(1–2):131–148

Gummesson E (2000) Qualitative methods in management research. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Hallstedt SI, Isaksson O (2017) Material criticality assessment in early phases of sustainable product development. J Clean Prod 161:40–52

Hasan H, Smith S, Finnegan P (2017) An activity theoretic analysis of the mediating role of information systems in tackling climate change adaptation. Inf Syst J 27:271–308

Herr K, Anderson GL (2005) The action research dissertation: a guide for students and faculty. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Book Google Scholar

Lewin K (1997 [1946]) Action research and minority problems. In: Lewin K (ed) Resolving social conflicts and field theory in social science. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp 34–46

Manring SL (2014) The role of universities in developing interdisciplinary action research collaborations to understand and manage resilient social-ecological systems. J Clean Prod 64:125–135

Masters J (1995) The history of action research. In: Hughes I (ed) Action research electronic reader. http://www.aral.com.au/arow/rmasters.html . Accessed 5 Jan 2017

Meyers MD (2013) Qualitative research in business & management. Sage, London

Middel R, Brennan L, Coghlan D, Coghlan P (2005) The application of action learning and action research in collaborative improvement within the extended manufacturing enterprise. In: Kotzab H, Seuring S, Müller M, Reiner G (eds) Research methodologies in supply chain management. Physika, Heidelberg, pp 365–380

Chapter Google Scholar

Park P (2006) Knowledge and participatory research. In: Reason P, Bradbury H (eds) The handbook of action research. Sage, London, pp 83–93

Reason P, Bradbury H (2006) The handbook of action research. Sage, London

Richert M (2017) An energy management framework tailor-made for SMEs: case study of a German car company. J Clean Prod 164:221–229

Robèrt K, Borén S, Ny H, Broman G (2017) A strategic approach to sustainable transport system development – part 1: attempting a generic community planning process model. J Clean Prod 140:53–61

Shapira H, Ketchie A, Nehe M (2017) The integration of design thinking and strategic sustainable development. J Clean Prod 140:277–287

Skinner H (2017) Action research. In: Kubacki K, Rundle-Thiele S (eds) Formative research in social marketing. Springer Science + Business Media, Singapore, pp 11–31

Stringer ET (2013) Action research, 4th edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Susman GI, Evered RD (1978) An assessment of the scientific merits of action research. Adm Sci Q 23(4):582–603

Tschiggerl K (2017) Aktionsforschung und deren Anwendung in den Wirtschaftswissenschaften. Working paper, Montanuniversitaet Leoben

Tschiggerl K, Fresner J (2008) From “doing green” to “doing good”: a consultancy perspective of mainstreaming sustainable development through continuous improvement. Paper presented at the Corporate Responsibility Research Conference CRRC 2008, Queen’s University Management School, Belfast, 7–9 September 2008

Tschiggerl K, Topic M (2018) A systematic approach to adopt sustainability and efficiency practices in energy-intensive industries. In: Leal Filho W (ed) Handbook of sustainability science and research. Springer, Berlin, pp 523–536

Velenturf APM, Purnell P (2017) Resource recovery from waste: restoring the balance between resource scarcity and waste overload. Sustainability 9(9):1603

Wilber K (2000) Integral psychology. Shambhala, Boston

Wittmayer J, Schaepke N, Feiner G, Piotrowski R, van Steenbergen F, Baasch S (2013) Action research for sustainability: reflections on transition management in practice. http://incontext-fp7.eu/sites/default/files/InContext-ResearchBrief-Action_research_for_sustainability.pdf . Accessed 21 Dec 2017

World Commission on Environment and Development WCED (1987) Our common future. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Zuber-Skerrit O (2012) Action research for sustainable development in a turbulent world. Emerald, Bingley

Zuber-Skerrit O, Perry C (2002) Action research within organisations and university thesis writing. Learn Organ 9(4):171–179

Zuber-Skerrit O, Wood L, Bob D (2013) Action research for sustainable development in a turbulent world: reflections and future perspectives. Action Learn Action Res J 18(2):184–203

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Montanuniversitaet Leoben, Leoben, Austria

Karin Tschiggerl

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Karin Tschiggerl .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Life Sciences, World Sustainable Development Research and Transfer Centre, Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, Hamburg, Germany

Walter Leal Filho

Section Editor information

Democritus University of Thrace, Thrace, Greece

Evangelos Manolas

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Tschiggerl, K. (2019). Action Research on Sustainable Development. In: Leal Filho, W. (eds) Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11352-0_158

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11352-0_158

Published : 11 October 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-11351-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-11352-0

eBook Packages : Education Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Education

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Health Res Policy Syst

An analysis of the strategic plan development processes of major public organisations funding health research in nine high-income countries worldwide

Cristina morciano.

1 Research Coordination and Support Service, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Viale Regina Elena, 299, 00161 Rome, Italy

Maria Cristina Errico

Carla faralli.

2 National Centre for Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy

Luisa Minghetti

Associated data.

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article in Additional file 1 .

There have been claims that health research is not satisfactorily addressing healthcare challenges. A specific area of concern is the adequacy of the mechanisms used to plan investments in health research. However, the way organisations within countries devise research agendas has not been systematically reviewed. This study seeks to understand the legal basis, the actors and the processes involved in setting research agendas in major public health research funding organisations.

We reviewed information relating to the formulation of strategic plans by 11 public funders in nine high-income countries worldwide. Information was collected from official websites and strategic plan documents in English, French, Italian and Spanish between January 2019 and December 2019, by means of a conceptual framework and information abstraction form.

We found that the formulation of a strategic plan is a common and well-established practice in shaping research agendas across international settings. Most of the organisations studied are legally required to present a multi-year strategic plan. In some cases, legal provisions may set rules for actors and processes and may establish areas of research and/or types of research to be funded. Commonly, the decision-making process involves both internal and external stakeholders, with the latter being generally government officials and experts, and few examples of the participation of civil society. The process also varies across organisations depending on whether there is a formal requirement to align to strategic priorities developed by an overarching entity at national level. We also found that, while actors and their interactions were traceable, information, sources of information, criteria and the mechanisms/tools used to shape decisions were made less explicit.

Conclusions

A complex picture emerges in which multiple interactive entities appear to shape research plans. Given the complexity of the influences of different parties and factors, the governance of the health research sector would benefit from a traceable and standardised knowledge-based process of health research strategic planning. This would provide an opportunity to demonstrate responsible budget stewardship and, more importantly, to make efforts to remain responsive to healthcare challenges, research gaps and opportunities.

Advances in scientific knowledge have contributed greatly to improvements in healthcare, but there have been claims that health research is not adequately addressing healthcare challenges. These concerns are reflected in the increasing debate over the adequacy of the mechanisms used to plan investment in health research and ensure its optimal distribution [ 1 – 5 ].

Over recent decades, methods and tools have been produced in order to guide the process of setting the health research agenda and facilitate more explicit and transparent judgment regarding research priorities. There is no single method that is considered appropriate for all settings and purposes, yet it is recognised that their optimal application requires a knowledge of health needs, research gaps and the perspectives of key stakeholders [ 6 – 10 ].

A number of studies have described initiatives to set health research agendas. Several articles refer to experiences focusing on specific health conditions, for example, those undertaken under the framework of the James Lind Alliance [ 11 ]. There are also reviews of disparate examples of research agenda-setting in low- and middle-income countries [ 12 , 13 ] as well as in high-income countries (HICs) [ 14 ]. These initiatives were highly heterogeneous with regard to their promotor (public organisations, academics, advocacy groups, etc.), the level of the research system (global, regional, national, sub-national, organisational or sub-organisational) and the scope of the prioritisation process (broad themes or specific research questions).

However, there are no studies that have specifically investigated the way large public organisations in HICs devise their research agendas and to what extent this is linked to regulations and organisational setup. In 2016, Moher et al. reported on how research funders had addressed recommendations to increase value and reduce waste in biomedical research [ 15 ]. Within this framework, they provided a general overview of setting the overall agenda in a convenient sample of six public funders of health research. They also affirmed the need for a “ periodic survey of information on research funders’ websites about their principle and methods used to decide what research to support ” [ 15 ]. At the same time, Viergever et al. identified the 10 largest funders of health research in the world and recommended further study of their priority-setting processes [ 16 ].

Given this context, we wished to provide an updated and thorough description of the way public funders of research in HICs devise their research agenda. We therefore analysed the regulatory framework for the actors and processes involved in developing the strategic plan in 11 major English and non-English speaking public research funders across 9 HICs worldwide.

Strategic planning

Our analysis focused on the development of the strategic plan, or strategic planning, at organisational level as a crucial step in the setting of the research agenda by the organisation. By the term ‘setting the research agenda’, we meant the whole-organisation research management planning cycle, which may encompass multiple decision-making level (organisational, sub-organisational, research programme level, etc.) actors and funding flows.

Strategic planning has been defined in social science as a “ deliberative, disciplined effort to produce fundamental decisions and actions that shape and guide what an organization (or other entity) is, what it does, and why ” [ 17 ].

The strategic plan is assumed to be the final outcome of the strategic planning process, in which priority-setting is the key milestone. It is therefore expected that the research priorities of the organisation will be included. Depending on mandate, priorities could be related to research topics (e.g. health conditions or diseases), types of research (e.g. basic or clinical) and/or other planned initiatives (e.g. workforce or research integrity).

The choice to focus on strategic planning was also guided by the fact that it is known from social science that strategic planning is a well-established practice within public organisations worldwide [ 17 , 18 ]. This would enable us to ensure comparability of information on modalities of decision-making in research planning across organisations from different countries.

Selection of public organisations

We created a list of public funders of health research, drawing from a previous study in which the authors identified 55 public and philanthropic organisations and listed them according to their annual expenditure on health research [ 16 ]. In order to strike a balance between learning about the practices of health research funders, and keeping data collection feasible and manageable, we restricted our sample to two organisations per country, with health research budgets of more than 200 million USD annually. In doing so, we identified a manageable subsample of 35 organisations having the greatest potential influence on research agendas, both locally and globally, and representing different health research systems in different countries.

We based our overview on publicly available information and restricted our sample to those organisations with published strategic research plans in English, French, Italian or Spanish (Additional file 1 ).

Information search and abstraction

Since we expected processes to vary across organisations, we did not use guidelines or best practices for strategic planning, which allowed us to document a wide range of experiences. As mentioned earlier, we based this overview on the collection of publicly available information by means of a conceptual framework and an information abstraction form (Box 1 , Additional file 1 ).

We based the conceptual framework on Walt and Gilson’s policy analysis model [ 19 ] and the information that could actually be retrieved after an initial assessment of the available information. The conceptual framework and the data abstraction form were conceived in an effort to (1) standardise the search for and collection of information across organisations, (2) render the collection process more transparent, and (3) make the retrieved information more understandable to readers.

Three authors (CM, CF and MCE) performed the review of information and the compilation of the form independently, with differences of opinion resolved by discussion. Information was collected in duplicate from 1 January 2019 to 31 July 2019. Before submitting the article, we updated the information by accessing and reviewing the official websites of the included organisations until 10 December 2019.

We searched for information that answered our questions by (1) browsing the funding organisations’ official websites and following links providing information about the organisations, e.g. Who we are, About us, Mission, Laws and statutes, Funding opportunities and other similar web pages, and by (2) identifying and reviewing strategic plans. When an organisation was composed of multiple sub-organisations, we limited our analysis to the strategic planning of the overarching organisation.

A second phase of research consisted of producing a profile for each organisation according to the data extraction form (Additional file 1 ). Bearing in mind that the results of this analysis could have been very general, we also used two organisations as case studies to provide more detailed examples of planning and implementing research priorities at the organisational level. We accessed and reviewed the official websites of the case study organisations until 14 April 2020. We did not contact organisations directly to obtain additional information. After collecting and analysing the information, we produced a narrative overview of our findings.

Box 1 Conceptual framework

Organisation profile

This section describes the funding organisation and its role and relationship with other overarching governmental bodies.

What are the contents of the strategic plan?

This section examines the publicly available strategic plan of the funding organisation. The strategic plan is assumed to be the final outcome of the strategic planning process and includes the research priorities of the organisation. Depending on the mandate of the organisation, the research priorities are those related to research topics (for example, health conditions/diseases), types of research (for example, basic research, clinical research) and/or other planned initiatives within the mandate of the organisation (e.g. workforce, research integrity).

Regulatory basis

This part seeks to understand if there is an official basis for strategic planning, for example, a law or a government document that establishes processes and actors for setting priorities.

What are the process and tools of strategic planning?

This section seeks to describe the processes and tools for identifying the research priorities included in the strategic plan, including whether or not there are explicit mechanisms, criteria, instruments and information to guide and inform the process of strategic planning such as a research landscape analysis or a more structured experience of priority-setting.

Who are the actors involved?

This section examines who the involved actors are in preparing the strategic plan; for example, who coordinates the process and who is involved in the process (e.g. clinicians, patients, citizens, researchers) and how the organisation relates with other entities in preparing the strategic plan.

Included organisations

We included 11 public organisations with a publicly available strategic plan in English, Spanish, French or Italian (Additional file 1 ). There were two from the United States, two from France, and one each from the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Japan, Italy, Spain and Singapore. The mandates of the organisations were diverse – some had the task of funding research and other activities in support of health research, while others were involved in both funding and conducting health research (Table 1 ).

Description of the selected organisations and of the development of their strategic plan

The strategic plan: format and content

The strategic plans varied in format (Additional file 1 ). While some organisations indicated broad lines of research, others structured their strategic plan in a complex hierarchy with high-level priorities connected to goals and sub-goals. In some cases, indicators, or menus of indicators, were added to monitor progress of the planned work and/or assess the impact of the research. In some research plans, the type of research funding (e.g. responsive, commissioned, research training) and budget were explicitly linked to research priorities.

With regard to content, some organisations focused their strategy on supporting the production of new knowledge of specific diseases or conditions. Others prepared a comprehensive strategy to support different functions of the health research system, such as producing knowledge, sustaining the workforce and infrastructure, developing policies for research integrity and conceiving processes for making more informed decisions. Some strategic plans briefly described the research environment at the national, organisational or programme level. One organisation described the process used to develop health research priorities.

Most of the organisations are legally required to present a multi-year strategic plan or at least annual research priorities. In addition, legislation sets rules and procedures by covering subjects such as the actors to be involved, the documents to be consulted and the format of the strategic plan document to be adopted. In some cases, legal provisions indicate areas and/or types of research to be funded (Table 1 ).

Commonly, the main actors are the top-level policy-makers of the organisations. A spectrum of external stakeholders from multiple sectors may be involved and their participation varies across organisations. External stakeholders can be members of academia or government research agencies, or industry professionals and policy-makers. Most frequently, they have a membership role in organisational governing bodies (boards and committees) (Table 1 ).

The government maintains a role in shaping the strategic plan to various extents in different organisations. This may involve producing nationwide strategic plans for research that the organisations have to adopt or align to, directing attention to specific research priorities or types of research, having representatives in the governing bodies of the organisations and retaining the power of final approval of the organisations’ strategic plans (Table 1 ). Other actors involved are overarching government agencies, which play a role in managing or coordinating the research plan at the national level. Examples of this are the Spanish National Research Agency and United Kingdom Research and Innovation (UKRI). When this study was being conducted, the latter had just been established and been given the role of developing a coherent national research strategy.

The participation of civil society in governing bodies, temporary committees or consultation exercises was far less common. There are representatives of the public in the advisory bodies of the National Institutes of Health (NIH; e.g. the Advisory Committee to the Director).

The Chief Executive Officer of the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), acting under the terms of the NHMRC Act, established the Community and Consumer Advisory Group. This is a working committee whose function is to provide advice on health questions and health and medical research matters, from consumer and community perspectives. Most notably, the United States Department of Defense – Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs (DoD-CDMRP) involve consumers (patients, their representatives and caregivers) at all levels of the funding process, from strategic planning to the peer-review process of research proposals. Organisations also have external consultation exercises, in which the target audiences and mechanisms implemented vary (Table 1 ).

In order to illustrate the interactions between different actors, we identified two broad categories of organisation. The first comprises those organisations that develop their own plans with a certain degree of independence. Government and legal provisions might provide some direction. In this group are the NIH, the Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale (Inserm), the Italian Ministry of Health (MoH), the NHMRC, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Medical Research Council (MRC), the DoD-CDMRP, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (Table 1 ).

The second category is made up of those organisations whose research planning derives from the strategic plan of an overarching entity. In this group are the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), the National Medical Research Council (NMRC) and the MRC. Both categories are represented in the case studies below.

An example of the first category from the United States is the 5-year strategic plan, NIH-Wide Strategic Plan, Fiscal Years 2016–2020: Turning Discovery Into Health, developed by the NIH at the request of Congress. Legislation provides direction on some criteria for setting priorities in the plan, but it is the NIH Director who develops it in consultation with internal (Centres, Institutes and Offices) and external stakeholders (see the NIH case study).

In Australia, the Chief Executive Officer of the NHMRC identifies major national health issues likely to arise during the 4-year period covered by the plan and devises the strategy in consultation with the Minister for Health and the NHMRC governing bodies. The Minister provides guidance on the NHMRC’s strategic priorities and approves or revises the plan. In Canada, the governing bodies of the CIHR are responsible for devising the strategic plan. The Deputy Minister of the Department of Health participates as a non-voting member of one of the governing bodies.

The common characteristic of the second category is that the process of strategic planning derives from one or more overarching entities. This means that the strategic plans of the organisations are informed to various extents by the research programmes of such an entity or entities. In some cases, there is a main institution with research coordination and/or management roles at the national level. For example, in Spain, in order to inform funding grants, the ISCIII adopted the research priorities set out in the Strategic Action for Health included in the State Plan for Science, Innovation and Technology 2017–2020 . This plan, elaborated by the Government Delegated Committee for the Policies for Research, Technology and Innovation ( la Comisión Delegada del Gobierno para Política Scientífica, Tecnológica y de Innovación ), in cooperation with the Ministry of Fianance, is aligned with the four strategic objectives of the Spanish Strategy for Science, Technology and Innovation 2013–2020. The newly established Spanish State Research Agency ( Agencia Estatal de Investigacion ) also participated in the development of the State Plan. However, its role is mainly in monitoring the plan’s funding, including ISCIII funding for the Strategic Action for Health.

UKRI, sponsored by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, is the body responsible for the development of a coherent national research strategy that balances the allocation of funding across different disciplines. In 2018, the MRC became a committee body of UKRI, alongside eight other committees, called ‘Councils’, which represent various research sectors. The MRC is required to develop a strategic plan that is coherent with the strategic objectives set by UKRI. This plan must be approved by the UKRI Board, the governing body responsible for ensuring that Council plans are consistent with the UKRI strategy.

In Singapore, the NMRC refers to the strategic plan developed by the National Research Foundation, a department within the Prime Minister’s Office. The NMRC has a well-described system for incorporating national priorities into the organisation’s research plan (see the NMRC case study).

With regard to the information, sources of information, criteria and mechanisms used to shape decisions, the included organisations were less explicit. Most commonly, organisations introduced health research priorities with an overview of major general advancements in biomedical research or a catalogue of organisational activities and a research portfolio.

A small number of organisations presented a brief situational analysis of the health and health research sectors. In these cases, the scope and nature of the presented information varied from one organisation to another (Additional file 1 ).

For example, the NIH-Wide Strategic Plan contains a brief summary of the state of research at the organisational level. The plans of each DoD-CDMRP health research programme present a summary of both the current health and health research landscapes at the national level.

Other organisations stated that the plan had been supported by information analysis of the research field, but they did not report explicitly on this work.

Case studies

The national institutes of health (nih).

The NIH is an operating division of the United States Department of Health and Human Services whose mission is to improve public health by conducting and funding basic and translational biomedical research. It is made up of 27 theme-based Institutes, Centers and Offices, each of which develops an individual strategic plan [ 20 ].

The first 5-year strategic plan, NIH-Wide Strategic Plan, Fiscal Years 2016–2020: Turning Discovery into Health, was prepared at the request of Congress and published in 2016 [ 21 ]. The legal framework stipulates that the NIH-coordinated strategy will inform the individual strategic plans of the Institutes and Centers. In addition, it provides some direction regarding content and the process to be adopted for generating the overall NIH strategy [ 22 , 23 ]. For example, it sets out specific requirements for the identification of research priorities. These include “ an assessment of the state of biomedical and behavioural research ” and the consideration of “ (i) disease burden in the United States and the potential for return on investment to the United States; (ii) rare diseases and conditions; (iii) biological, social, and other determinants of health that contributes to health disparities; and (iv) other factors the Director of National Institutes of Health determines appropriate ” [ 23 ]. The NIH Director is also required to consult “ with the directors of the national research institutes and national centers, researchers, patient advocacy groups and industry leaders ” [ 23 ]. To fulfil the request of Congress, the NIH Director and the Principal Deputy Director initiated the process by creating a draft ‘framework’ for the strategic plan. This framework was designed with the purposes of identifying major areas of research that cut across NIH priorities and of setting out principles to guide the NIH research effort (‘unifying principles’).

The development of the NIH-Wide Strategic Plan involved extensive internal and external consultations throughout the process. Consultees included the ad hoc NIH-Wide Strategic Plan Working Group, composed of representatives of all 27 Institutes, Centers and Offices, the Advisory Committee to the Director, which is an NIH standing committee of experts in research fields relevant to the NIH mission, and representatives of the research community (from academia and the private sector) and the general public. The framework was also presented at meetings with the National Advisory Councils of the Institutes and Centers.

In addition, the framework was disseminated to external stakeholders for comments and suggestions, which were solicited via a series of public webinars and through the initiative Request for Information: Inviting Comments and Suggestions on a Framework for the NIH-Wide Strategic Plan. In this case, a web-based form collected comments and suggestions on a predefined list of topic areas from a wide array of stakeholders representative of patient advocacy organisations, professional associations, private hospitals and companies, academic institutions, government and private citizens [ 24 – 27 ]. A report on the analysis of the public comments is publicly available [ 27 ].

The National Medical Research Council (NMRC)

The NMRC is the organisation that has the role of promoting, coordinating and funding biomedical research in Singapore [ 28 ]. It has developed its own research strategy by adopting the research priorities indicated by the national research strategy in the domain of health and biomedical sciences [ 29 ].

The national research strategy is the responsibility of the National Research Foundation, a department of the Prime Minister’s Office. It defines broad research priorities relating to various areas of research identified as ‘domains’. Within the health and biomedical sciences domain, five areas of research have been proposed with input from the Ministry of Health and the Health and Biomedical Sciences International Advisory Council. These are cancer, cardiovascular diseases, infectious diseases, neurological and sense disorders, diabetes mellitus and other metabolic/endocrine conditions. Criteria for selection of the areas of focus were “ disease impact, scientific excellence in Singapore and national needs ” [ 29 ].

The approach of NMRC to implementing the national research strategy at organisational level involves the establishment of ‘task forces’, i.e. groups of experts, with the role of defining the specific research strategy for each of the five areas of focus. Each task force provides documentation of research recommendations and methods used to prioritise research topics [ 30 ].

For example, the Neurological and Sense Disorders Task Force identified sub-areas of research 1 after analysing the local burden of neurological and sense disorders as well as considering factors such as local scientific expertise and research talent, ongoing efforts in neurological and sense disorders, industry interest, and opportunities for Singapore. As part of the effort, input was also solicited from the research community and policy-makers. This research prioritisation exercise served for both the NMRC grant scheme and a 10-year research roadmap [ 31 ].

Our study is the first to report on the processes used by a set of large national public funders to develop health research strategic plans. In line with findings from public management literature [ 16 , 17 ], we found that the formulation of a strategic plan is a well-established practice in shaping research agendas across international settings and it is a legal requirement for the majority of the organisations we studied.

We were able to reconstruct the process for developing the strategic plan by identifying the main actors involved and how they are connected. A complex picture emerges, in which multiple interactive entities and forces, often organised in a non-linear dynamic, appear to shape the research plans. In general, an organisation has to take into account legislative provisions, government directives, national overall research plans, national health plans and specific disease area plans. In some cases, it has to consider ‘institutionalised’ allocation of resources across organisations’ sub-entities (institutes, centres and units), which are historically associated with a particular disease or type of research.

On the other hand, we found little documentation of the decision-making mechanisms and information used to inform decision-making. There were, for example, few references to health research needs, research capabilities, the sources of information consulted, and the principles and criteria applied. This despite the increasing attention being paid nationally and internationally to the need for an explicit evidence-based or rational approach to setting health research priorities, particularly in the light of current economic constraints [ 3 , 32 , 33 ]. Given the complexity of the influences of different parties and factors, the governance of the health research sector would benefit from a traceable knowledge-based process of strategic planning, similar to that advocated for the health sector [ 34 ].

We found, however, evidence of an increasing interest in improving ways to establish research priorities at the organisational level. For example, NIH has brought forward the Senate request to develop a coordinated research strategy by including, in the strategic plan, the intention to further improve the processes for setting NIH research priorities and to optimise approaches to making informed funding decisions [ 21 ].

Recently, the DoD-CDMRP, the second largest funder of health research in the United States, reviewed its research management practices upon the recommendations of an ad hoc committee of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. In the area of strategic planning, the committee recommended an analysis of the funding landscape across different agencies and organisations, the identification of short- and long-term research needs, and harmonisation with the research priorities of other organisations [ 35 ].

In its strategic plan, the JSPS has placed particular emphasis on the development of research-on-research capacity and infrastructures to analyse the research landscape at organisational, national and international levels in order to ensure that funding decisions are evidence based [ 36 ].

The allocation of sufficient resources to develop the infrastructure and technical expertise required for collection, analysis and dissemination of a portfolio of relevant data should be considered a necessary step when a funding organisation or country decides to implement standardised approaches for strategic planning and priority-setting.

Additionally, from the perspective of health research as a system, data collection and analyses should not be limited to ‘what is funded’, but should also include ‘who is funded and where’, and be linked to research policies and their long-term outcomes. The benefit of such an approach is not limited to the prevention of unnecessary duplication of research. Support would also be provided for producing formal mechanisms to coordinate research effort across research entities, within and among countries. Collaborations with other non-profit as well as for-profit organisations would be promoted and the capacity for research would be created and strengthened where necessary.

A number of resources and initiatives in this field already exist at organisational and national level. For example, the NIH has the Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools, a public repository of data and other tools from NIH research activities [ 37 ]. This repository is linked to Federal RePORTER, an infrastructure that makes data on federal investments in science available. In the United Kingdom, the Health Research Classification System performs regular analysis of the funding landscape of United Kingdom health research to support monitoring, strategy development and coordination [ 38 ].

At the international level, there is ongoing global work to shape evidence-based health research decisions and coordination. In 2013, the WHO Global Observatory on Health R&D was established “ in order to monitor and analyze relevant information on health research and development, […] with a view to contributing to the identification of gaps and opportunities for health research and development and defining priorities […] and to facilitate the development of a global shared research agenda ” [ 33 ]. This effort has been coupled with a global call to action, which asks governments to create or strengthen national health research observatories and contribute to the WHO Observatory. Furthermore, the Clinical Research Initiative for Global Health, a consortium of research organisations across the world, has ongoing projects that will map clinical research networks and funding capacity and conduct clinical research at a global level [ 39 ].

A further key area that deserves comment is the engagement of stakeholders. In general, a spectrum of external stakeholders from multiple sectors is involved and the extent of this involvement varies across organisations. Decision-making processes commonly include people from government bodies, academia, research agencies and industry. However, we found that the participation of civil society, here represented by the intended beneficiaries of research such as health professionals, patients and their carers, remains limited. The fact that decision-making is still the domain of government officials and experts is an unexpected finding. There is a widespread consensus that the participation of a mix of stakeholders can improve the process of strategic planning. The logic behind this is that representatives of those who are affected by decisions can bring new information and perspectives and improve the effectiveness of the process [ 17 , 32 , 40 ]. Broader inclusion is desirable, both for granting legitimacy to strategic planning and for advancing equity in healthcare. Decisions on research priorities shape knowledge and, ultimately, they determine whether patients and their carers will have access to healthcare options that meet their needs [ 41 ].

Additionally, our study shows that the involvement of civil society is not only desirable but is also feasible. Organisations that support the participation of civil society have this practice firmly embedded in their governance, although it may be implemented in different ways.

Strengths and limitations

A particular strength of our study is the innovative way in which we approached the disorienting complexity of whole-organisation planning cycle management. This allowed us to contribute to an understanding of the processes used by large public funders not only in English-speaking countries but also in France, Italy and Spain.

However, one potential limitation concerns the accuracy and completeness of the information. This drawback was imposed by both the unstructured nature of the information and its fragmentation across multiple webpages and legal and/or administrative documents. Nevertheless, we strove to ensure accuracy, consistency and a clear presentation of the relevant information by means of a conceptual framework and a data abstraction form. In addition, to guarantee the reliability of the data, two reviewers abstracted the information independently, before discussing it and reaching a consensus. The use of more accessible information, e.g. through single documents, would therefore be advisable to improve accountability and transparency. This would also be of particular importance for exchanging knowledge and promoting research in the specific field of research governance.

In addition to the limitations imposed by the available data, there is a potential limitation in the methodology of the study. In conducting our research, we decided to rely only on publicly available information and we did not ask organisations for further details. Consequently, we may have missed some actions and drawn an incomplete picture of the organisations presented. Our strategy was based on the assumption that, if a strategic plan existed, both it and a description of its associated decision-making process would be present in the public domain, given that transparency in decision-making is an acknowledged element of good public organisation governance [ 42 ]. We would therefore counter that the process should be more transparent and should address, in particular, the criteria and information used to support decision-making.

In addition, it was not possible to ascertain in detail how processes actually took place. For example, engaging external stakeholders, such as representatives of civil society, is a key feature of the organisations included in the study but we do not know whether this engagement was meaningful or simply granted legitimacy to leadership decisions.

Furthermore, by limiting our inclusion criteria to organisations with strategic plans publicly available in English, French, Spanish and Italian, we excluded two German organisations (the German Research Foundation and the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung – the Federal Ministry of Education and Research) and two Chinese bodies (the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Ministry of Health). These organisations could have been included on the basis of their health research budgets. While it is unlikely that these bodies from two countries with similar health research systems have practices that would have changed our conclusions, it would nevertheless be useful in the future to acquire information regarding their experiences in this area.

Future research

Having considered the abovementioned limitations, we recommend that qualitative research be conducted to further validate our findings by complementing the information presented here with data gathered from key informants within each organisation. We also suggest that the study be extended to include other organisations and countries. Additional research should also expand on our study by more deeply exploring the perspectives of the members of external stakeholder bodies regarding their involvement in strategic planning within each organisation. Making this information accessible would benefit those funder organisations who wish to both increase public engagement in health research decision-making and make it more meaningful.

It would also be interesting to explore whether and why funder organisations are influenced by the research plans of other organisations (including academic, advocacy and international bodies) within and among countries, and whether they have formal mechanisms in place to coordinate with other such organisations. This information would be of use in guiding research coordination policies, with the aim of avoiding duplication of effort and identifying not only gaps in research but also overlapping interests and opportunities for partnerships.

Our study illustrates the variety of the processes adopted in developing strategic plans for health research in the international setting. A complex picture emerges in which multiple interactive entities appear to shape research plans. Although we found documentation of the actors involved in the processes, much less was available on the mechanisms, information, criteria and tools used to inform decision-making.

Given the complexity of the influences of different parties and factors, both funding organisations and health sector governance would benefit from a traceable knowledge-based process of strategic planning. The benefits of such an approach are not limited to demonstrating responsible budget stewardship as it would also provide opportunities to respond to research gaps and healthcare needs and to move more effectively from basic to translational research.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements.

The authors thank Letizia Sampaolo, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, the information specialist who made an initial search of relevant scientific articles, and Stephen James for English language review of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

Authors’ contributions.

CM conceived of the study and made a first drafted the work. CM, MCE and CF abstracted the data and compiled the organisations’ profiles. LM contributed to the draft and substantively revised the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This research was partly supported by funding for 'Ricerca Corrente' of the Istituto Superiore di Sanità.

Availability of data and materials

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

1 Neurodegenerative diseases (vascular dementia and Parkinson’s diseases), neurodegenerative eye diseases (age-related macular degeneration and glaucoma), mental health disorders (depression) and neurotechnology.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Cristina Morciano, Email: [email protected] .

Maria Cristina Errico, Email: [email protected] .

Carla Faralli, Email: [email protected] .

Luisa Minghetti, Email: [email protected] .

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12961-020-00620-x.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

Published on January 27, 2023 by Tegan George . Revised on January 12, 2024.

Table of contents

Types of action research, action research models, examples of action research, action research vs. traditional research, advantages and disadvantages of action research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about action research.

There are 2 common types of action research: participatory action research and practical action research.

- Participatory action research emphasizes that participants should be members of the community being studied, empowering those directly affected by outcomes of said research. In this method, participants are effectively co-researchers, with their lived experiences considered formative to the research process.

- Practical action research focuses more on how research is conducted and is designed to address and solve specific issues.

Both types of action research are more focused on increasing the capacity and ability of future practitioners than contributing to a theoretical body of knowledge.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Action research is often reflected in 3 action research models: operational (sometimes called technical), collaboration, and critical reflection.

- Operational (or technical) action research is usually visualized like a spiral following a series of steps, such as “planning → acting → observing → reflecting.”

- Collaboration action research is more community-based, focused on building a network of similar individuals (e.g., college professors in a given geographic area) and compiling learnings from iterated feedback cycles.

- Critical reflection action research serves to contextualize systemic processes that are already ongoing (e.g., working retroactively to analyze existing school systems by questioning why certain practices were put into place and developed the way they did).

Action research is often used in fields like education because of its iterative and flexible style.

After the information was collected, the students were asked where they thought ramps or other accessibility measures would be best utilized, and the suggestions were sent to school administrators. Example: Practical action research Science teachers at your city’s high school have been witnessing a year-over-year decline in standardized test scores in chemistry. In seeking the source of this issue, they studied how concepts are taught in depth, focusing on the methods, tools, and approaches used by each teacher.

Action research differs sharply from other types of research in that it seeks to produce actionable processes over the course of the research rather than contributing to existing knowledge or drawing conclusions from datasets. In this way, action research is formative , not summative , and is conducted in an ongoing, iterative way.

As such, action research is different in purpose, context, and significance and is a good fit for those seeking to implement systemic change.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Action research comes with advantages and disadvantages.

- Action research is highly adaptable , allowing researchers to mold their analysis to their individual needs and implement practical individual-level changes.

- Action research provides an immediate and actionable path forward for solving entrenched issues, rather than suggesting complicated, longer-term solutions rooted in complex data.

- Done correctly, action research can be very empowering , informing social change and allowing participants to effect that change in ways meaningful to their communities.

Disadvantages

- Due to their flexibility, action research studies are plagued by very limited generalizability and are very difficult to replicate . They are often not considered theoretically rigorous due to the power the researcher holds in drawing conclusions.

- Action research can be complicated to structure in an ethical manner . Participants may feel pressured to participate or to participate in a certain way.

- Action research is at high risk for research biases such as selection bias , social desirability bias , or other types of cognitive biases .

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Action research is conducted in order to solve a particular issue immediately, while case studies are often conducted over a longer period of time and focus more on observing and analyzing a particular ongoing phenomenon.