Sapir–Whorf hypothesis (Linguistic Relativity Hypothesis)

Mia Belle Frothingham

Author, Researcher, Science Communicator

BA with minors in Psychology and Biology, MRes University of Edinburgh

Mia Belle Frothingham is a Harvard University graduate with a Bachelor of Arts in Sciences with minors in biology and psychology

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

There are about seven thousand languages heard around the world – they all have different sounds, vocabularies, and structures. As you know, language plays a significant role in our lives.

But one intriguing question is – can it actually affect how we think?

It is widely thought that reality and how one perceives the world is expressed in spoken words and are precisely the same as reality.

That is, perception and expression are understood to be synonymous, and it is assumed that speech is based on thoughts. This idea believes that what one says depends on how the world is encoded and decoded in the mind.

However, many believe the opposite.

In that, what one perceives is dependent on the spoken word. Basically, that thought depends on language, not the other way around.

What Is The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis?

Twentieth-century linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf are known for this very principle and its popularization. Their joint theory, known as the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis or, more commonly, the Theory of Linguistic Relativity, holds great significance in all scopes of communication theories.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis states that the grammatical and verbal structure of a person’s language influences how they perceive the world. It emphasizes that language either determines or influences one’s thoughts.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis states that people experience the world based on the structure of their language, and that linguistic categories shape and limit cognitive processes. It proposes that differences in language affect thought, perception, and behavior, so speakers of different languages think and act differently.

For example, different words mean various things in other languages. Not every word in all languages has an exact one-to-one translation in a foreign language.

Because of these small but crucial differences, using the wrong word within a particular language can have significant consequences.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is sometimes called “linguistic relativity” or the “principle of linguistic relativity.” So while they have slightly different names, they refer to the same basic proposal about the relationship between language and thought.

How Language Influences Culture

Culture is defined by the values, norms, and beliefs of a society. Our culture can be considered a lens through which we undergo the world and develop a shared meaning of what occurs around us.

The language that we create and use is in response to the cultural and societal needs that arose. In other words, there is an apparent relationship between how we talk and how we perceive the world.

One crucial question that many intellectuals have asked is how our society’s language influences its culture.

Linguist and anthropologist Edward Sapir and his then-student Benjamin Whorf were interested in answering this question.

Together, they created the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which states that our thought processes predominantly determine how we look at the world.

Our language restricts our thought processes – our language shapes our reality. Simply, the language that we use shapes the way we think and how we see the world.

Since the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis theorizes that our language use shapes our perspective of the world, people who speak different languages have different views of the world.

In the 1920s, Benjamin Whorf was a Yale University graduate student studying with linguist Edward Sapir, who was considered the father of American linguistic anthropology.

Sapir was responsible for documenting and recording the cultures and languages of many Native American tribes disappearing at an alarming rate. He and his predecessors were well aware of the close relationship between language and culture.

Anthropologists like Sapir need to learn the language of the culture they are studying to understand the worldview of its speakers truly. Whorf believed that the opposite is also true, that language affects culture by influencing how its speakers think.

His hypothesis proposed that the words and structures of a language influence how its speaker behaves and feels about the world and, ultimately, the culture itself.

Simply put, Whorf believed that you see the world differently from another person who speaks another language due to the specific language you speak.

Human beings do not live in the matter-of-fact world alone, nor solitary in the world of social action as traditionally understood, but are very much at the pardon of the certain language which has become the medium of communication and expression for their society.

To a large extent, the real world is unconsciously built on habits in regard to the language of the group. We hear and see and otherwise experience broadly as we do because the language habits of our community predispose choices of interpretation.

Studies & Examples

The lexicon, or vocabulary, is the inventory of the articles a culture speaks about and has classified to understand the world around them and deal with it effectively.

For example, our modern life is dictated for many by the need to travel by some vehicle – cars, buses, trucks, SUVs, trains, etc. We, therefore, have thousands of words to talk about and mention, including types of models, vehicles, parts, or brands.

The most influential aspects of each culture are similarly reflected in the dictionary of its language. Among the societies living on the islands in the Pacific, fish have significant economic and cultural importance.

Therefore, this is reflected in the rich vocabulary that describes all aspects of the fish and the environments that islanders depend on for survival.

For example, there are over 1,000 fish species in Palau, and Palauan fishers knew, even long before biologists existed, details about the anatomy, behavior, growth patterns, and habitat of most of them – far more than modern biologists know today.

Whorf’s studies at Yale involved working with many Native American languages, including Hopi. He discovered that the Hopi language is quite different from English in many ways, especially regarding time.

Western cultures and languages view times as a flowing river that carries us continuously through the present, away from the past, and to the future.

Our grammar and system of verbs reflect this concept with particular tenses for past, present, and future.

We perceive this concept of time as universal in that all humans see it in the same way.

Although a speaker of Hopi has very different ideas, their language’s structure both reflects and shapes the way they think about time. Seemingly, the Hopi language has no present, past, or future tense; instead, they divide the world into manifested and unmanifest domains.

The manifested domain consists of the physical universe, including the present, the immediate past, and the future; the unmanifest domain consists of the remote past and the future and the world of dreams, thoughts, desires, and life forces.

Also, there are no words for minutes, minutes, or days of the week. Native Hopi speakers often had great difficulty adapting to life in the English-speaking world when it came to being on time for their job or other affairs.

It is due to the simple fact that this was not how they had been conditioned to behave concerning time in their Hopi world, which followed the phases of the moon and the movements of the sun.

Today, it is widely believed that some aspects of perception are affected by language.

One big problem with the original Sapir-Whorf hypothesis derives from the idea that if a person’s language has no word for a specific concept, then that person would not understand that concept.

Honestly, the idea that a mother tongue can restrict one’s understanding has been largely unaccepted. For example, in German, there is a term that means to take pleasure in another person’s unhappiness.

While there is no translatable equivalent in English, it just would not be accurate to say that English speakers have never experienced or would not be able to comprehend this emotion.

Just because there is no word for this in the English language does not mean English speakers are less equipped to feel or experience the meaning of the word.

Not to mention a “chicken and egg” problem with the theory.

Of course, languages are human creations, very much tools we invented and honed to suit our needs. Merely showing that speakers of diverse languages think differently does not tell us whether it is the language that shapes belief or the other way around.

Supporting Evidence

On the other hand, there is hard evidence that the language-associated habits we acquire play a role in how we view the world. And indeed, this is especially true for languages that attach genders to inanimate objects.

There was a study done that looked at how German and Spanish speakers view different things based on their given gender association in each respective language.

The results demonstrated that in describing things that are referred to as masculine in Spanish, speakers of the language marked them as having more male characteristics like “strong” and “long.” Similarly, these same items, which use feminine phrasings in German, were noted by German speakers as effeminate, like “beautiful” and “elegant.”

The findings imply that speakers of each language have developed preconceived notions of something being feminine or masculine, not due to the objects” characteristics or appearances but because of how they are categorized in their native language.

It is important to remember that the Theory of Linguistic Relativity (Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis) also successfully achieves openness. The theory is shown as a window where we view the cognitive process, not as an absolute.

It is set forth to look at a phenomenon differently than one usually would. Furthermore, the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis is very simple and logically sound. Understandably, one’s atmosphere and culture will affect decoding.

Likewise, in studies done by the authors of the theory, many Native American tribes do not have a word for particular things because they do not exist in their lives. The logical simplism of this idea of relativism provides parsimony.

Truly, the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis makes sense. It can be utilized in describing great numerous misunderstandings in everyday life. When a Pennsylvanian says “yuns,” it does not make any sense to a Californian, but when examined, it is just another word for “you all.”

The Linguistic Relativity Theory addresses this and suggests that it is all relative. This concept of relativity passes outside dialect boundaries and delves into the world of language – from different countries and, consequently, from mind to mind.

Is language reality honestly because of thought, or is it thought which occurs because of language? The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis very transparently presents a view of reality being expressed in language and thus forming in thought.

The principles rehashed in it show a reasonable and even simple idea of how one perceives the world, but the question is still arguable: thought then language or language then thought?

Modern Relevance

Regardless of its age, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, or the Linguistic Relativity Theory, has continued to force itself into linguistic conversations, even including pop culture.

The idea was just recently revisited in the movie “Arrival,” – a science fiction film that engagingly explores the ways in which an alien language can affect and alter human thinking.

And even if some of the most drastic claims of the theory have been debunked or argued against, the idea has continued its relevance, and that does say something about its importance.

Hypotheses, thoughts, and intellectual musings do not need to be totally accurate to remain in the public eye as long as they make us think and question the world – and the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis does precisely that.

The theory does not only make us question linguistic theory and our own language but also our very existence and how our perceptions might shape what exists in this world.

There are generalities that we can expect every person to encounter in their day-to-day life – in relationships, love, work, sadness, and so on. But thinking about the more granular disparities experienced by those in diverse circumstances, linguistic or otherwise, helps us realize that there is more to the story than ours.

And beautifully, at the same time, the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis reiterates the fact that we are more alike than we are different, regardless of the language we speak.

Isn’t it just amazing that linguistic diversity just reveals to us how ingenious and flexible the human mind is – human minds have invented not one cognitive universe but, indeed, seven thousand!

Kay, P., & Kempton, W. (1984). What is the Sapir‐Whorf hypothesis?. American anthropologist, 86(1), 65-79.

Whorf, B. L. (1952). Language, mind, and reality. ETC: A review of general semantics, 167-188.

Whorf, B. L. (1997). The relation of habitual thought and behavior to language. In Sociolinguistics (pp. 443-463). Palgrave, London.

Whorf, B. L. (2012). Language, thought, and reality: Selected writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. MIT press.

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis: Examples, Definition, Criticisms

Developed in 1929 by Edward Sapir, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (also known as linguistic relativity ) states that a person’s perception of the world around them and how they experience the world is both determined and influenced by the language that they speak.

The theory proposes that differences in grammatical and verbal structures, and the nuanced distinctions in the meanings that are assigned to words, create a unique reality for the speaker. We also call this idea the linguistic determinism theory .

Spair-Whorf Hypothesis Definition and Overview

Cibelli et al. (2016) reiterate the tenets of the hypothesis by stating:

“…our thoughts are shaped by our native language, and that speakers of different languages therefore think differently”(para. 1).

Kay & Kempton (1984) explain it a bit more succinctly. They explain that the hypothesis itself is based on the:

“…evolutionary view prevalent in 19 th century anthropology based in both linguistic relativity and determinism” (pp. 66, 79).

Linguist Edward Sapir, an American linguist who was interested in anthropology , studied at Yale University with Benjamin Whorf in the 1920’s.

Sapir & Whorf began to consider lexical and grammatical patterns and how these factored into the construction of different culture’s views of the world around them.

For example, they compared how thoughts and behavior differed between English speakers and Hopi language speakers in regard to the concept of time, arguing that in the Hopi language, the absence of the future tense has significant relevance (Kay & Kempton, 1984, p. 78-79).

Whorf (2021), in his own words, asserts:

“Every language is a vast pattern-system, different from others, in which are culturally ordained the forms and categories by which the personality not only communicates, but also analyzes nature, notices or neglects types of relationship and phenomena, channels his reasoning, and builds the house of his consciousness” (p. 252).

10 Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Examples

- Constructions of food in language: A language may ascribe many words to explain the same concept, item, or food type. This shows that they perceive it as extremely important in their society, in comparison to a culture whose language only has one word for that same concept, item, or food.

- Descriptions of color in language: Different cultures may visually perceive colors in different ways according to how the colors are described by the words in their language.

- Constructions of gender in language: Many languages are “gendered”, creating word associations that pertain to the roles of men or women in society.

- Perceptions of time in language: Depending upon how the tenses are structured in a language, it may dictate how the people that speak that language perceive the concept of time.

- Categorization in language: The ways concepts and items in a given culture are categorized (and what words are assigned to them) can affect the speaker’s perception of the world around them.

- Politeness is encoded in language: Levels of politeness in a language and the pronoun combinations to express these levels differ between languages. How languages express politeness with words can dictate how they perceive the world around them.

- Indigenous words for snow: A popular example used to justify this hypothesis is the Inuit people, who have a multitude of ways to express the word snow. If you follow the reasoning of Sapir, it would suggest that the Inuits have a profoundly deeper understanding of snow than other cultures.

- Use of idioms in language: An expression or well-known saying in one culture has an acute meaning implicitly understood by those that speak the particular language but is not understandable when expressed in another language.

- Values are engrained in language: Each country and culture have beliefs and values as a direct result of the language it uses.

- Slang in language: The slang used by younger people evolves from generation to generation in all languages. Generational slang carries with it perceptions and ideas about the world that members of that generation share.

See Other Hypothesis Examples Here

Two Ways Language Shapes Perception

1. perception of categories and categorization.

How concepts and items in a culture are categorized (and what words are assigned to them) can affect the speaker’s perception of the world around them.

Although the examples of this phenomenon are too numerous to cite, a clear example is the extremely contextual, nuanced, and hyper-categorized Japanese language.

In the English language, the concept of “you” and “I” is narrowed to these two forms. However, Japanese has numerous ways to express you and I, each having various levels of politeness and appropriateness in relation to age, gender, and stature in society.

While in common conversation, the pronoun is often left out of the conversation – reliant on context, misuse or omission of the proper pronoun can be perceived as rude or ill-mannered.

In other ways, the complexity of the categorical lexicons can often leave English speakers puzzled. This could come in the form of classifications of different shaped bowls and plates that serve different functions; it could be traces of the ancient Japanese calendar from the 7 th Century, that possessed 72 micro-seasons during a year, or any number of sub-divided word listings that may be considered as one blanket term in another language.

Masuda et al. (2017) gives a clear example:

“ People conceptualize objects along the lines drawn between existing categories in their native language. That is, if two concepts fall into the same linguistic category, the perception of similarity between these objects would be stronger than if the two concepts fall into different linguistic categories.”

They then go on to give the example of how Japanese vs English speakers might categorize an everyday object – the bell:

“For example, in Japanese, the kind of bell found in a bell tower generally corresponds to the word kane—a large bell—which is categorically different from a small bell, suzu. However, in English, these two objects are considered to belong within the same linguistic category, “bell.” Therefore, we might expect English speakers to perceive these two objects as being more similar than would Japanese speakers (para 5).

2. Perception of the Concept of Time

According to a way the tenses are structured in a language, it may dictate how the people that speak that language perceive the concept of time

One of Sapir’s most famous applications of his theory is to the language of the Arizona Native American Hopi tribe.

He claimed, although refuted vehemently by linguistic scholars since, that they have no general notion of time – that they cannot decipher between the past, present, or future because of the grammatical structures that are used within their language.

As Engle (2016) asserts, Sapir believed that the Hopi language “encodes on ordinal value, rather than a passage of time”.

He concluded that, “a day followed by a night is not so much a new day, but a return to daylight” (p. 96).

However, it is not only Hopi culture that has different perception of time imbedded in the language; Thai culture has a non-linear concept of time, and the Malagasy people of Madagascar believe that time in motion around human beings, not that human beings are passing through time (Engle, 2016, p. 99).

Criticism of Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

1. language as context-dependent.

Iwamoto (2005) expresses that the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis fails to recognize that language is used within context. Its purely decontextualized textual analysis of language is too one-dimensional and doesn’t consider how we actually use language:

“Whorf’s “neat and simplistic” linguistic relativism presupposes the idea that an entire language or entire societies or cultures are categorizable or typable in a straightforward, discrete, and total manner, ignoring other variables such as contextual and semantic factors .” (Iwamoto, 2005, p. 95)

2. Not universally applicable

Another criticism of the hypothesis is that Sapir & Whorf’s hypothesis cannot be transferred or applied to all languages.

It is difficult to cite empirical studies that confirm that other cultures do not also have similarities in the way concepts are perceived through their language – even if they don’t possess a similar word/expression for a particular concept that is expressed.

3. thoughts can be independent of language

Stephen Pinker, one of Sapir & Whorf’s most emphatic critics, would argue that language is not of our thoughts, and is not a cultural invention that creates perceptions; it is in his opinion, a part of human biology (Meier & Pinker, 1995, pp. 611-612).

He suggests that the acquisition and development of sign language show that languages are instinctual, therefore biological; he even goes so far as to say that “all speech is an illusion”(p. 613).

Cibelli, E., Xu, Y., Austerweil, J. L., Griffiths, T. L., & Regier, T. (2016). The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis and Probabilistic Inference: Evidence from the Domain of Color. PLOS ONE , 11 (7), e0158725. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158725

Engle, J. S. (2016). Of Hopis and Heptapods: The Return of Sapir-Whorf. ETC.: A Review of General Semantics , 73 (1), 95. https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1G1-544562276/of-hopis-and-heptapods-the-return-of-sapir-whorf

Iwamoto, N. (2005). The Role of Language in Advancing Nationalism. Bulletin of the Institute of Humanities , 38 , 91–113.

Meier, R. P., & Pinker, S. (1995). The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language. Language , 71 (3), 610. https://doi.org/10.2307/416234

Masuda, T., Ishii, K., Miwa, K., Rashid, M., Lee, H., & Mahdi, R. (2017). One Label or Two? Linguistic Influences on the Similarity Judgment of Objects between English and Japanese Speakers. Frontiers in Psychology , 8 . https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01637

Kay, P., & Kempton, W. (1984). What Is the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis? American Anthropologist , 86 (1), 65–79. http://www.jstor.org/stable/679389

Whorf, B. L. (2021). Language, Thought, and Reality: Selected Writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf . Hassell Street Press.

Gregory Paul C. (MA)

Gregory Paul C. is a licensed social studies educator, and has been teaching the social sciences in some capacity for 13 years. He currently works at university in an international liberal arts department teaching cross-cultural studies in the Chuugoku Region of Japan. Additionally, he manages semester study abroad programs for Japanese students, and prepares them for the challenges they may face living in various countries short term.

- Gregory Paul C. (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Upper Middle-Class Lifestyles: 10 Defining Features

- Gregory Paul C. (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Arousal Theory of Motivation: Definition & Examples

- Gregory Paul C. (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Theory of Mind: Examples and Definition

- Gregory Paul C. (MA) #molongui-disabled-link 10 Strain Theory Examples (Plus Criticisms of Merton)

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Positive Punishment Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Dissociation Examples (Psychology)

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 15 Zone of Proximal Development Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link Perception Checking: 15 Examples and Definition

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis: How Language Influences How We Express Ourselves

Rachael is a New York-based writer and freelance writer for Verywell Mind, where she leverages her decades of personal experience with and research on mental illness—particularly ADHD and depression—to help readers better understand how their mind works and how to manage their mental health.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/RachaelGreenProfilePicture1-a3b8368ef3bb47ccbac92c5cc088e24d.jpg)

Thomas Barwick / Getty Images

What to Know About the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

Real-world examples of linguistic relativity, linguistic relativity in psychology.

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, also known as linguistic relativity, refers to the idea that the language a person speaks can influence their worldview, thought, and even how they experience and understand the world.

While more extreme versions of the hypothesis have largely been discredited, a growing body of research has demonstrated that language can meaningfully shape how we understand the world around us and even ourselves.

Keep reading to learn more about linguistic relativity, including some real-world examples of how it shapes thoughts, emotions, and behavior.

The hypothesis is named after anthropologist and linguist Edward Sapir and his student, Benjamin Lee Whorf. While the hypothesis is named after them both, the two never actually formally co-authored a coherent hypothesis together.

This Hypothesis Aims to Figure Out How Language and Culture Are Connected

Sapir was interested in charting the difference in language and cultural worldviews, including how language and culture influence each other. Whorf took this work on how language and culture shape each other a step further to explore how different languages might shape thought and behavior.

Since then, the concept has evolved into multiple variations, some more credible than others.

Linguistic Determinism Is an Extreme Version of the Hypothesis

Linguistic determinism, for example, is a more extreme version suggesting that a person’s perception and thought are limited to the language they speak. An early example of linguistic determinism comes from Whorf himself who argued that the Hopi people in Arizona don’t conjugate verbs into past, present, and future tenses as English speakers do and that their words for units of time (like “day” or “hour”) were verbs rather than nouns.

From this, he concluded that the Hopi don’t view time as a physical object that can be counted out in minutes and hours the way English speakers do. Instead, Whorf argued, the Hopi view time as a formless process.

This was then taken by others to mean that the Hopi don’t have any concept of time—an extreme view that has since been repeatedly disproven.

There is some evidence for a more nuanced version of linguistic relativity, which suggests that the structure and vocabulary of the language you speak can influence how you understand the world around you. To understand this better, it helps to look at real-world examples of the effects language can have on thought and behavior.

Different Languages Express Colors Differently

Color is one of the most common examples of linguistic relativity. Most known languages have somewhere between two and twelve color terms, and the way colors are categorized varies widely. In English, for example, there are distinct categories for blue and green .

Blue and Green

But in Korean, there is one word that encompasses both. This doesn’t mean Korean speakers can’t see blue, it just means blue is understood as a variant of green rather than a distinct color category all its own.

In Russian, meanwhile, the colors that English speakers would lump under the umbrella term of “blue” are further subdivided into two distinct color categories, “siniy” and “goluboy.” They roughly correspond to light blue and dark blue in English. But to Russian speakers, they are as distinct as orange and brown .

In one study comparing English and Russian speakers, participants were shown a color square and then asked to choose which of the two color squares below it was the closest in shade to the first square.

The test specifically focused on varying shades of blue ranging from “siniy” to “goluboy.” Russian speakers were not only faster at selecting the matching color square but were more accurate in their selections.

The Way Location Is Expressed Varies Across Languages

This same variation occurs in other areas of language. For example, in Guugu Ymithirr, a language spoken by Aboriginal Australians, spatial orientation is always described in absolute terms of cardinal directions. While an English speaker would say the laptop is “in front of” you, a Guugu Ymithirr speaker would say it was north, south, west, or east of you.

As a result, Aboriginal Australians have to be constantly attuned to cardinal directions because their language requires it (just as Russian speakers develop a more instinctive ability to discern between shades of what English speakers call blue because their language requires it).

So when you ask a Guugu Ymithirr speaker to tell you which way south is, they can point in the right direction without a moment’s hesitation. Meanwhile, most English speakers would struggle to accurately identify South without the help of a compass or taking a moment to recall grade school lessons about how to find it.

The concept of these cardinal directions exists in English, but English speakers aren’t required to think about or use them on a daily basis so it’s not as intuitive or ingrained in how they orient themselves in space.

Just as with other aspects of thought and perception, the vocabulary and grammatical structure we have for thinking about or talking about what we feel doesn’t create our feelings, but it does shape how we understand them and, to an extent, how we experience them.

Words Help Us Put a Name to Our Emotions

For example, the ability to detect displeasure from a person’s face is universal. But in a language that has the words “angry” and “sad,” you can further distinguish what kind of displeasure you observe in their facial expression. This doesn’t mean humans never experienced anger or sadness before words for them emerged. But they may have struggled to understand or explain the subtle differences between different dimensions of displeasure.

In one study of English speakers, toddlers were shown a picture of a person with an angry facial expression. Then, they were given a set of pictures of people displaying different expressions including happy, sad, surprised, scared, disgusted, or angry. Researchers asked them to put all the pictures that matched the first angry face picture into a box.

The two-year-olds in the experiment tended to place all faces except happy faces into the box. But four-year-olds were more selective, often leaving out sad or fearful faces as well as happy faces. This suggests that as our vocabulary for talking about emotions expands, so does our ability to understand and distinguish those emotions.

But some research suggests the influence is not limited to just developing a wider vocabulary for categorizing emotions. Language may “also help constitute emotion by cohering sensations into specific perceptions of ‘anger,’ ‘disgust,’ ‘fear,’ etc.,” said Dr. Harold Hong, a board-certified psychiatrist at New Waters Recovery in North Carolina.

As our vocabulary for talking about emotions expands, so does our ability to understand and distinguish those emotions.

Words for emotions, like words for colors, are an attempt to categorize a spectrum of sensations into a handful of distinct categories. And, like color, there’s no objective or hard rule on where the boundaries between emotions should be which can lead to variation across languages in how emotions are categorized.

Emotions Are Categorized Differently in Different Languages

Just as different languages categorize color a little differently, researchers have also found differences in how emotions are categorized. In German, for example, there’s an emotion called “gemütlichkeit.”

While it’s usually translated as “cozy” or “ friendly ” in English, there really isn’t a direct translation. It refers to a particular kind of peace and sense of belonging that a person feels when surrounded by the people they love or feel connected to in a place they feel comfortable and free to be who they are.

Harold Hong, MD, Psychiatrist

The lack of a word for an emotion in a language does not mean that its speakers don't experience that emotion.

You may have felt gemütlichkeit when staying up with your friends to joke and play games at a sleepover. You may feel it when you visit home for the holidays and spend your time eating, laughing, and reminiscing with your family in the house you grew up in.

In Japanese, the word “amae” is just as difficult to translate into English. Usually, it’s translated as "spoiled child" or "presumed indulgence," as in making a request and assuming it will be indulged. But both of those have strong negative connotations in English and amae is a positive emotion .

Instead of being spoiled or coddled, it’s referring to that particular kind of trust and assurance that comes with being nurtured by someone and knowing that you can ask for what you want without worrying whether the other person might feel resentful or burdened by your request.

You might have felt amae when your car broke down and you immediately called your mom to pick you up, without having to worry for even a second whether or not she would drop everything to help you.

Regardless of which languages you speak, though, you’re capable of feeling both of these emotions. “The lack of a word for an emotion in a language does not mean that its speakers don't experience that emotion,” Dr. Hong explained.

What This Means For You

“While having the words to describe emotions can help us better understand and regulate them, it is possible to experience and express those emotions without specific labels for them.” Without the words for these feelings, you can still feel them but you just might not be able to identify them as readily or clearly as someone who does have those words.

Rhee S. Lexicalization patterns in color naming in Korean . In: Raffaelli I, Katunar D, Kerovec B, eds. Studies in Functional and Structural Linguistics. Vol 78. John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2019:109-128. Doi:10.1075/sfsl.78.06rhe

Winawer J, Witthoft N, Frank MC, Wu L, Wade AR, Boroditsky L. Russian blues reveal effects of language on color discrimination . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(19):7780-7785. 10.1073/pnas.0701644104

Lindquist KA, MacCormack JK, Shablack H. The role of language in emotion: predictions from psychological constructionism . Front Psychol. 2015;6. Doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00444

By Rachael Green Rachael is a New York-based writer and freelance writer for Verywell Mind, where she leverages her decades of personal experience with and research on mental illness—particularly ADHD and depression—to help readers better understand how their mind works and how to manage their mental health.

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Linguistic Theory

DrAfter123/Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is the linguistic theory that the semantic structure of a language shapes or limits the ways in which a speaker forms conceptions of the world. It came about in 1929. The theory is named after the American anthropological linguist Edward Sapir (1884–1939) and his student Benjamin Whorf (1897–1941). It is also known as the theory of linguistic relativity, linguistic relativism, linguistic determinism, Whorfian hypothesis , and Whorfianism .

History of the Theory

The idea that a person's native language determines how he or she thinks was popular among behaviorists of the 1930s and on until cognitive psychology theories came about, beginning in the 1950s and increasing in influence in the 1960s. (Behaviorism taught that behavior is a result of external conditioning and doesn't take feelings, emotions, and thoughts into account as affecting behavior. Cognitive psychology studies mental processes such as creative thinking, problem-solving, and attention.)

Author Lera Boroditsky gave some background on ideas about the connections between languages and thought:

"The question of whether languages shape the way we think goes back centuries; Charlemagne proclaimed that 'to have a second language is to have a second soul.' But the idea went out of favor with scientists when Noam Chomsky 's theories of language gained popularity in the 1960s and '70s. Dr. Chomsky proposed that there is a universal grammar for all human languages—essentially, that languages don't really differ from one another in significant ways...." ("Lost in Translation." "The Wall Street Journal," July 30, 2010)

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis was taught in courses through the early 1970s and had become widely accepted as truth, but then it fell out of favor. By the 1990s, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis was left for dead, author Steven Pinker wrote. "The cognitive revolution in psychology, which made the study of pure thought possible, and a number of studies showing meager effects of language on concepts, appeared to kill the concept in the 1990s... But recently it has been resurrected, and 'neo-Whorfianism' is now an active research topic in psycholinguistics ." ("The Stuff of Thought. "Viking, 2007)

Neo-Whorfianism is essentially a weaker version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis and says that language influences a speaker's view of the world but does not inescapably determine it.

The Theory's Flaws

One big problem with the original Sapir-Whorf hypothesis stems from the idea that if a person's language has no word for a particular concept, then that person would not be able to understand that concept, which is untrue. Language doesn't necessarily control humans' ability to reason or have an emotional response to something or some idea. For example, take the German word sturmfrei , which essentially is the feeling when you have the whole house to yourself because your parents or roommates are away. Just because English doesn't have a single word for the idea doesn't mean that Americans can't understand the concept.

There's also the "chicken and egg" problem with the theory. "Languages, of course, are human creations, tools we invent and hone to suit our needs," Boroditsky continued. "Simply showing that speakers of different languages think differently doesn't tell us whether it's language that shapes thought or the other way around."

- Definition and Discussion of Chomskyan Linguistics

- Generative Grammar: Definition and Examples

- Cognitive Grammar

- Universal Grammar (UG)

- Transformational Grammar (TG) Definition and Examples

- The Theory of Poverty of the Stimulus in Language Development

- Linguistic Performance

- Linguistic Competence: Definition and Examples

- What Is a Natural Language?

- The Definition and Usage of Optimality Theory

- 24 Words Worth Borrowing From Other Languages

- What Is Linguistic Functionalism?

- Definition and Examples of Case Grammar

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Biography of Noam Chomsky, Writer and Father of Modern Linguistics

- An Introduction to Semantics

Sapir Whorf Hypothesis

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, a foundational concept in linguistics, posits that the structure of a language influences its speakers’ worldview or cognition. Crafting a thesis statement around this intricate theory requires a nuanced understanding of language’s role in shaping thought. This guide delves into formulating clear and compelling hypothesis statements on the Sapir-Whorf premise, accompanied by standout examples and invaluable writing insights. Dive in to unravel the intertwining dynamics of language and thought.

What is a Sapir-Whorf hypothesis?

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, often referred to as linguistic relativity, is a concept in linguistics that posits that the structure and vocabulary of a language can influence and shape its speakers’ cognition, worldview, and perception of reality. The idea suggests that people’s understanding of the world is fundamentally intertwined with the language they speak. A Good hypothesis is named after its proponents, Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf.

What is an example of a statement that supports the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis?

An often-cited example in support of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is the various words for snow in the Inuit languages. The claim, although sometimes exaggerated, is that because the Inuit have multiple words to describe different types of snow, they perceive and interact with snow differently than speakers of languages with fewer terms. This linguistic diversity for a particular phenomenon ostensibly provides a richer, more nuanced understanding and perception of that phenomenon.

100 Sapir Whorf Hypothesis Statement Examples

Size: 223 KB

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, emphasizing linguistic relativity, has inspired numerous debates and studies in linguistics. Crafting a scientific hypothesis statement around this theory means exploring how language nuances might shape thought patterns and perspectives. Delve into these illustrative examples to understand the multifaceted impact of language on cognition.

- The Color Spectrum : Languages with more color words allow speakers to differentiate shades more distinctly than languages with fewer color terms.

- Time Perception : Cultures with cyclical concepts of time, reflected in their languages, perceive events differently from those with linear time concepts.

- Gendered Languages : Languages that assign gender to inanimate objects can influence speakers’ perceptions of those objects.

- Spatial Relations : The use of cardinal directions in certain indigenous languages results in speakers having an innate sense of orientation.

- Emotion Expression : Some languages may lack direct translations for emotions found in other languages, potentially affecting emotional awareness or expression.

- Causality Descriptions : Different languages might attribute blame or causality differently due to their grammatical structures.

- Action Descriptions : How languages describe actions (e.g., breaking a vase) can shape the speaker’s perception of intent or accident.

- Counting Systems : The existence or absence of certain numbers in languages can influence basic math skills or value perceptions.

- Metaphor Usage : Metaphors unique to certain languages might shape the way speakers conceptualize abstract ideas.

- Abstract Concepts : Concepts like love, honor, or bravery might have nuanced interpretations based on linguistic structures.

- Danger Perception : The way languages describe danger or safety can influence cautionary behaviors in speakers.

- Moral Judgments : Moral values or judgments might be swayed by the presence or absence of particular terms.

- Value Systems : Languages that emphasize communal terms might foster a more collective mindset in their speakers.

- Nature Relations : Indigenous languages with diverse terms for nature might shape a deeper connection or respect for the environment.

- Interpersonal Interactions : The manner in which respect or hierarchy is linguistically structured can affect social interactions.

- Past and Future : Tenses and structures that emphasize the past or future can shape speakers’ attitudes towards events.

- Taste and Flavor : Culinary terms unique to languages might shape the tasting experience.

- Musicality and Rhythm : Languages with a more rhythmic cadence might influence their speakers’ musical perceptions.

- Material Value : The linguistic description of material wealth or poverty can shape value perceptions.

- Body and Health : Body image and health perceptions can be influenced by the terminology used in different languages.

- Dream Interpretations : Some cultures have unique linguistic terms for dream elements, potentially influencing dream interpretations.

- Learning Styles : Languages that emphasize visual or auditory elements might shape preferred learning modalities.

- Decision Making : The linguistic framing of choices and consequences in different languages can impact decision-making processes.

- Kinship Terms : Languages with intricate kinship terminologies might promote stronger familial bonds or responsibilities.

- Faith and Spirituality : The way divinity or spiritual experiences are described in different languages can shape spiritual perceptions.

- Conflict Resolution : Linguistic nuances in addressing disputes can influence conflict resolution techniques.

- Weather Perceptions : Languages with varied terms for weather patterns might influence speakers’ reactions or preparations for weather changes.

- Cultural Celebrations : Specific cultural festivals, named and described uniquely in different languages, can shape the sentiment around these celebrations.

- Animal Relations : Indigenous languages might have unique terms for animals, reflecting a different relationship or respect level with wildlife.

- Negotiations and Trade : Trade languages or lingua francas might influence negotiation styles or terms of agreements.

- Art and Creativity : The way different cultures linguistically describe art can shape artistic values or interpretations.

- Trust and Relationships : Trust-building words or phrases unique to certain languages can influence relationship dynamics.

- Parenting Styles : Different terminologies for parenting or child-rearing might reflect varied parenting values or techniques.

- Grief and Loss : The linguistic approach to grief, memorial, and remembrance can shape mourning practices.

- Storytelling Techniques : Narration styles can be influenced by the linguistic structures and storytelling terms unique to certain languages.

- Humor and Wit : What is considered humorous in one culture, reflected through language, might not translate directly into another language.

- Ethics and Virtue : The linguistic framing of right and wrong, or virtuous behaviors, can guide moral compasses.

- Travel and Exploration : The wanderlust spirit might be encapsulated differently across languages, influencing exploration desires.

- Sport and Competition : Terms of victory, defeat, or competition in languages can shape sportsmanship values.

- Mental Health : The linguistic approach to mental wellness or illness can shape stigma or understanding around mental health.

- Culinary Traditions : The way different cultures linguistically describe flavors or food preparation might shape their culinary uniqueness and appreciation.

- Temporal Perceptions : Languages that emphasize cyclical versus linear time can influence perspectives on past, present, and future.

- Environmental Conservation : Indigenous languages might have unique terms for nature, which could indicate a heightened sense of environmental stewardship.

- Value of Silence : Cultures with specific linguistic emphasis on listening or silence might place more importance on reflection and quietude.

- Musical Appreciation : The terminology around musical notes, scales, and emotions in songs can shape how music is created and enjoyed.

- Concept of Home : The linguistic definition of ‘home’ or ‘family’ in different languages can reflect distinct values or emotional attachments.

- Work Ethic and Ambition : How different languages describe success, hard work, or ambition might influence professional values.

- Monetary Relations : The way wealth, poverty, or economic status is described can shape perceptions around money and wealth distribution.

- Beauty Standards : Terms related to beauty or attractiveness in different languages might create distinct standards or ideals.

- Emotions and Feelings : Some languages have unique words for specific emotions, which might lead to varied emotional expressions or understandings.

- Aging and Maturity : How different cultures linguistically address aging might shape perceptions of maturity and life stages.

- Digital World : The introduction of technology-related terms in languages can influence the adoption and attitude towards digital evolution.

- Political Discourse : The language of politics, with its unique terms and phrases, can shape political beliefs and alignments.

- Education and Learning : Terminologies related to learning and intelligence in languages can mold educational values.

- Sense of Community : Languages emphasizing collective terms over individualistic ones might promote stronger communal bonds.

- Marriage and Partnerships : The way relationships, marriages, or partnerships are described linguistically can shape societal norms around them.

- Health and Well-being : Unique terms for health, wellness, or well-being in certain languages can influence health practices and beliefs.

- Spiritual Practices : Linguistic terms around meditation, prayer, or other spiritual practices can guide their significance in various cultures.

- Traditions and Rituals : The linguistic explanation of rituals or traditions can shape their importance and the way they’re practiced.

- Urbanization and Rural Life : The contrast between urban and rural life, as described in languages, can influence perceptions about city living versus countryside living.

- Travel and Exploration : Languages that contain vast lexicons for journey, adventure, or discovery may influence a culture’s propensity for exploration and travel.

- Interpersonal Connections : The presence or absence of specific terms related to friendships, partnerships, or alliances in a language can shape interpersonal relationships.

- Artistic Expressions : How a culture linguistically describes art forms, be it painting, sculpture, or dance, can shape their artistic creations and interpretations.

- Concept of Truth : How truth, honesty, and lies are linguistically depicted might play a role in the cultural values related to integrity.

- Justice and Morality : Distinct terms related to justice, rights, or moral codes in languages can determine the ethical fabric of a society.

- Sports and Leisure : The linguistic portrayal of games, fun, or relaxation can mold the recreational and sports norms of a culture.

- Weather Patterns : Languages with a variety of terms for specific weather conditions might influence communities’ adaptability and preparedness for diverse climates.

- Linguistic Evolution : The way languages adapt and incorporate new terms, especially from other languages, can be indicative of cultural assimilation and globalization trends.

- Gender Roles : The use of gender-specific or neutral terms in languages can influence gender roles and perceptions within a society.

- Conflict and Resolution : The terminology associated with war, peace, conflict, and reconciliation can shape a culture’s approach to disputes and their resolution.

- Agricultural Practices : The presence of diverse terms related to farming, crops, or soil in languages can be reflective of agricultural practices and innovations.

- Mental Health : The way mental health issues are linguistically framed can influence societal stigmas and support systems related to them.

- Space and Astronomy : Languages with specific terminologies for celestial bodies or space phenomena may impact a culture’s inclination towards astronomy and space exploration.

- Medicine and Healing : The lexicon associated with illness, healing, and medicine can guide a community’s approach to health and therapeutic practices.

- Fashion and Trends : How fashion, style, and trends are described in different languages can drive the fashion choices and aesthetics of a culture.

- Child Rearing and Parenting : The linguistic emphasis on concepts like discipline, love, nurture, or independence might influence parenting styles.

- Architectural Preferences : Terms related to space, design, or architecture in different languages can shape building styles and city planning.

- Social Media Influence : The way social media platforms and online interactions are linguistically framed can impact digital communication norms.

- Celebrations and Festivities : The terminology around celebration, joy, and festivals can determine the manner and fervor of communal celebrations.

- Philosophical Thought : The presence of terms related to existentialism, life, purpose, or philosophy can guide a culture’s philosophical leanings and debates.

- Dietary Habits : The variety of terms in a language for different types of food, preparation methods, or eating habits might sway a community’s culinary practices and preferences.

- Environmental Stewardship : A language that possesses diverse terms related to nature, conservation, and the environment may stimulate a heightened ecological awareness and practice within its speakers.

- Educational Systems : The terminologies related to learning, knowledge, wisdom, and instruction can influence a society’s approach to education and its structure.

- Emotional Expression : How emotions, feelings, and moods are portrayed linguistically can influence the emotional openness and expressivity of its speakers.

- Concept of Time : Languages that emphasize past, present, future, or cyclical events in unique ways might shape the cultural perceptions of time and its significance.

- Business Practices : The linguistic framing of commerce, trade, profit, and loss can guide the business ethos and entrepreneurial ventures of a community.

- Religious Practices : Terms and phrases related to divinity, spirituality, rituals, or faith can deeply affect the religious practices and beliefs of a society.

- Political Systems : The language surrounding governance, authority, rights, and duties can mold the political systems and ideologies within a culture.

- Music and Rhythms : The lexicon associated with sounds, rhythms, melodies, and harmony can drive the musical inclinations and genres popular in a community.

- Urbanization and Development : The terminologies addressing growth, urbanization, infrastructure, and planning can determine the developmental trajectory of a society.

- Animal and Plant Biodiversity : Languages rich in terms for various flora and fauna might affect a community’s interaction with and knowledge about biodiversity.

- Spiritual Practices : How spiritual concepts, rituals, and experiences are articulated can shape the spiritual journeys and quests of its speakers.

- Transport and Mobility : The linguistic framing of movement, speed, vehicles, and journeys might influence the transport systems and preferences of a society.

- Social Hierarchies : Terminologies related to class, caste, privilege, or status can impact the societal structures and hierarchies of a culture.

- Marriage and Relationships : The language encompassing love, marriage, partnerships, and relationships can mold the matrimonial practices and relationship norms.

- Mental Processes : The linguistic representation of thinking, reasoning, introspection, or cognition might influence cognitive processes and intellectual engagements.

- Technological Advancements : How technology, innovation, and digital realms are linguistically framed can guide technological adaptations and revolutions within a culture.

- Aging and Life Transitions : The terminologies about age, maturity, youth, or old age can shape societal views on aging and life phases.

- Economic Systems : The lexicon related to wealth, poverty, economy, or trade can steer the economic systems and policies of a nation.

- Nature and Landscapes : Languages with a plethora of terms for landscapes, terrains, or natural wonders might influence a culture’s relationship with nature and its conservation efforts.

Sapir Whorf Hypothesis Quizlet Statement Examples

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis delves into how language impacts cognitive processes and one’s worldview. The following are statements you might find on educational platforms like Quizlet, designed for study and review.

- Language Learning : Mastering a new language can expand an individual’s cognitive horizons and alter their perception of reality.

- Grammar Structures : The way a language’s grammar prioritizes events can influence how its speakers perceive actions and consequences.

- Color Perception : Different languages categorize colors uniquely, potentially affecting how their speakers recognize and differentiate hues.

- Spatial Relations : The linguistic tools available for discussing space and direction can shape spatial reasoning and navigation abilities.

- Mathematical Concepts : The linguistic representation of numbers and mathematical operations might alter mathematical reasoning in different cultures.

- Moral and Ethics : The terms available for discussing right and wrong can sway moral reasoning and ethical considerations.

- Causality : How cause and effect are linguistically constructed can impact understanding of events and their outcomes.

- Temporal Reasoning : The linguistic tools for discussing time can shape perceptions of past, present, and future events.

- Emotional Recognition : The words available for emotions can influence emotional recognition and expression.

- Social Interactions : Linguistic constructs regarding politeness, respect, and formality can mold social behavior and interactions.

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Statement Examples for Linguistic Determinism

Linguistic determinism is the idea that language and its structures limit and determine human knowledge or thought. Here are examples of statements reflecting this aspect of the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis.

- Gendered Languages : In languages with gendered nouns, speakers might inherently ascribe masculine or feminine qualities to objects.

- Tense Structures : Languages with specific future tenses may make speakers more future-oriented in their thinking and planning.

- Lexical Gaps : Absence of specific words in a language can make certain concepts difficult to grasp or articulate for its speakers.

- Counting Systems : In languages without words for numbers beyond a certain point, quantification of larger amounts becomes challenging.

- Descriptive Limitations : If a language lacks adjectives for certain emotions, its speakers might find it challenging to identify or express those feelings.

- Categorization : How a language categorizes objects or concepts linguistically can determine how its speakers mentally categorize them.

- Spatial References : In languages that use absolute directions (like North or South) instead of relative ones (like left or right), spatial cognition is fundamentally different.

- Time Conceptions : Languages without distinct past and future tenses may influence speakers to perceive time in a more cyclical or present-focused manner.

- Action Perceptions : In languages where the subject of a verb is always evident, speakers might always look for someone to credit or blame for actions.

- Sensory Limitations : Languages that don’t differentiate between certain sensory experiences might lead to less distinction between those sensations among its speakers.

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Statement Examples for Linguistic Relativity

Linguistic relativity posits that while language influences thought, it doesn’t strictly determine it. These statements exemplify the relativistic relationship between language and cognition.

- Bilingual Mindsets : Bilingual individuals may experience different cognitive patterns depending on the language they’re currently using.

- Cultural Expressions : Unique cultural phrases or idioms capture concepts that might not be present in other languages but can still be understood by outsiders with explanation.

- Translation Challenges : Some words or phrases might not have direct translations across languages, indicating unique cognitive constructs.

- Artistic Interpretations : Art forms, like poetry, can convey emotions and ideas that might be difficult to express in another language but aren’t impossible to understand.

- Shared Human Experiences : Despite linguistic differences, universal human experiences like love, grief, and joy are understood across cultures.

- Adapted Concepts : Over time, languages borrow and adapt words from other languages, showing flexible cognitive adaptation.

- Language Evolution : As cultures evolve, so do languages, reflecting shifting cognitive and societal priorities.

- Learning New Concepts : Even if a concept doesn’t exist in one’s native language, it can be learned and understood in another linguistic context.

- Multilingual Societies : In societies where multiple languages coexist, there’s evidence of flexible cognitive frameworks that move beyond linguistic limitations.

- Metaphorical Thinking : Different languages use different metaphors to describe similar concepts, highlighting varied cognitive pathways to understanding.

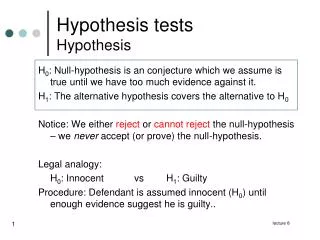

What are two main points of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis?

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, also known as linguistic relativity, posits a deep relationship between language and thought. This idea is named after its proponents, Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf. Here are the two primary points:

- Linguistic Determinism : This is the stronger form of the hypothesis and suggests that the language we speak determines the way we think, perceive, and understand the world. In other words, without the vocabulary or grammar structure in a language to represent a specific concept, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to comprehend that concept. For example, if a language lacks a word for a specific color, speakers of that language might not distinguish it as a separate color but rather as a shade of another color they can identify.

- Linguistic Relativity : This is a more moderate form of the hypothesis, which posits that language influences thought and perceptions but does not strictly dictate them. Here, variations in language result in differences in cognition across cultures, but it does not necessarily limit the cognitive capacity. For instance, even if a language lacks a specific term, speakers can still understand the concept if explained in different terms.

How do you write a Sapir-Whorf hypothesis statement? – Step by Step Guide

Crafting a Sapir-Whorf hypothesis statement involves understanding the influence of language on cognition and perception:

- Identify the Concept : Start by pinpointing a specific cognitive or perceptual concept you want to address, such as color perception, time, or morality.

- Research Language Variations : Understand how different languages represent or fail to represent this concept. For instance, are there languages without future tenses? How do they discuss future events?

- Formulate the Statement : Clearly articulate how language might determine or influence the perception of this concept. For instance: “In languages without future tenses, there might be a more present-focused worldview.”

- Provide Comparisons : To bolster your statement, contrast it with how the concept might be understood in another language.

- Review and Refine : Make sure your statement is clear, concise, and rooted in the principles of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.

Tips for Writing a Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Statement

- Be Specific : Given the intricate nature of the hypothesis, specificity can enhance clarity. Instead of making broad generalizations, pinpoint specific linguistic features and their potential cognitive effects.

- Use Real-Language Examples : Back up your statements with real examples from different languages to illustrate your point.

- Avoid Absolutism : Especially when discussing linguistic relativity, avoid making absolute statements. Remember, the hypothesis suggests influence, not strict determination.

- Stay Updated : Language and cognition research is ongoing. Familiarize yourself with current research on the topic to ensure your statements are up-to-date.

- Seek Feedback : Before finalizing your statement, seek feedback from peers or experts in linguistics to ensure accuracy and clarity.

- Refrain from Stereotyping : While the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis does suggest linguistic influence on cognition, it’s essential to avoid perpetuating cultural or linguistic stereotypes. Remember, language is just one of many factors that shape thought and perception.

AI Generator

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

- Preferences

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

Something went wrong! Please try again and reload the page.

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

Sapir-whorf hypothesis the sapir-whorf hypothesis revolves around the idea that language has power and can control how you see the world. language is a guide to your ... – powerpoint ppt presentation.

- The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis revolves around the idea that language has power and can control how you see the world. Language is a guide to your reality, structuring your thoughts. It provides the framework through which you make sense of the world.

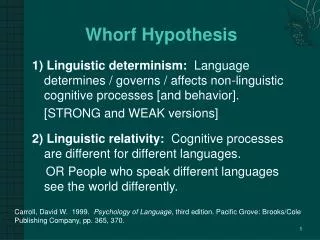

- Linguistic determinism the language we use to some extent determines the way in which we view and think about the world around us.

- Linguistic relativity people who speak different languages perceive and think about the world quite differently from one another.

- Example 1 Gasoline barrels

- Example 2 Inuit words for snow Apache place-names (Basso reading)

- Example 3 Hopi conceptions of time

- Example 4 Color words

- Example 5 Piraha lack of number words

PowerShow.com is a leading presentation sharing website. It has millions of presentations already uploaded and available with 1,000s more being uploaded by its users every day. Whatever your area of interest, here you’ll be able to find and view presentations you’ll love and possibly download. And, best of all, it is completely free and easy to use.

You might even have a presentation you’d like to share with others. If so, just upload it to PowerShow.com. We’ll convert it to an HTML5 slideshow that includes all the media types you’ve already added: audio, video, music, pictures, animations and transition effects. Then you can share it with your target audience as well as PowerShow.com’s millions of monthly visitors. And, again, it’s all free.

About the Developers

PowerShow.com is brought to you by CrystalGraphics , the award-winning developer and market-leading publisher of rich-media enhancement products for presentations. Our product offerings include millions of PowerPoint templates, diagrams, animated 3D characters and more.

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

Dec 20, 2019

100 likes | 235 Views

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis revolves around the idea that language has power and can control how you see the world. Language is a guide to your reality, structuring your thoughts. It provides the framework through which you make sense of the world.

Share Presentation

Presentation Transcript

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis revolves around the idea that language has power and can control how you see the world. Language is a guide to your reality, structuring your thoughts. It provides the framework through which you make sense of the world. See the article “The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis: Worlds Shaped by Words”

To understand the S-W Hypothesis, it helps to be aware that there are two opposing ideas about language and culture. The S-W Hypothesis is in line with the second idea listed here: 1. Language mirrors reality: People have thoughts first, then put them into words. Words record what is already there. All humans think the same way, but we use different words to label what we sense. This is an example of the cloak theory: that language is a cloak that conforms to the customary categories of thoughts of its speakers *This is NOT the S-W Hypothesis

To understand the S-W Hypothesis, it helps to be aware that there are two opposing ideas about language and culture. The S-W Hypothesis is in line with the second idea listed here: 2. Language dictates how we think. The vocabulary and grammar (structure) of a language determines the way we view the world (“worlds shaped by words”). This is an example of the mold theory: that language is a mold in terms of which thought categories are cast. *This IS the S-W Hypothesis

The S-W Hypothesis consists of 2 paired principles: Linguistic determinism: the language we use to some extent determines the way in which we view and think about the world around us. Linguistic relativity: people who speak different languages perceive and think about the world quite differently from one another.

Example 1: Gasoline barrels • Example 2: Inuit words for snow & Apache place-names (Basso reading) • Example 3: Hopi conceptions of time • Example 4: Color words • Example 5: Piraha lack of number words

Implications of the Strong Version of the S-W Hypothesis: • *note that these implications are controversial, which is why many do not accept the strong version of the S-W Hypothesis • •A change in world view is impossible for speakers of one language. For this reason, some speak of the “prison-house of language,” or call language a “straightjacket” • •True cross-cultural communication and translation are impossible • --case of Pablo Neruda – refuses to allow his poetry to be translated from Spanish • --case of Ngugi Wa Thiongo – refused, for a long time, to write in any language but Swahili • •Language is powerful–it can stimulate strong, emotional responses and shape how people think about morally and socially important issues. • --This is why we use euphemisms. • --This is why groups like the “language police” try to intervene and control what words people use.

- More by User

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. Rodolfo Celis Beaver College Linguistics. Read disclaimer first. Benjamin Lee Whorf. April 24, 1897 – July 26, 1941. Never trained formally as a linguist, though eventually came to be recognized as a leader in the field and held important university positions.

906 views • 9 slides

![sapir whorf hypothesis examples ppt Edward Sapir [1884-1939]](https://cdn0.slideserve.com/1084146/edward-sapir-1884-1939-dt.jpg)

Edward Sapir [1884-1939]

Edward Sapir [1884-1939]. Born in Germany and immigrated into the United States in late 19th century Events occuring during this time include the following - Wright Bros. first airplane 1903 - Einstein proposes theory of relativity 1905 - World War I 191

949 views • 7 slides

Hypothesis?

What's the deal with the left fusiform activity during reading positively correlated with phonological awareness in lower-SES children but not in higher-SES children?

294 views • 20 slides

Whorf Hypothesis and Color Terms

Whorf Hypothesis and Color Terms. The relation of language to culture and nature. Whorf Hypothesis. Benjamin Lee Whorf – Chemical Engineer worked as accident investigator for insurance companies. Whorf Hypothesis. Question Whorf sought to answer: Culture ↔ Language structure

398 views • 16 slides

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. Jessie G. Varquez , Jr. Anthro 270. 10 August 2011. Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Whorfian Hypothesis Linguistic Relativism. Language coerces thought The limit of my language is the limit of my world.

2.06k views • 24 slides

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis :

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis :. A hypothesis holding that the structure of a language affects the perceptions of reality of its speakers and thus influences their thought patterns and worldviews Language can thus DEFINE consciousness, as well as be a REFLECTION of it. Activity: The Human Continuum.

973 views • 7 slides

Effect of Baseline Serum Creatinine Estimation on Acute Kidney Injury Evaluation in Non-Critically Ill Children Treated with Aminoglycosides. Jillian Caldwell , BSc 1 , Michael Pizzi , BSc 1 , Melissa Piccioni , MSc 1 and Michael Zappitelli , MD, MSc 1 .

278 views • 1 slides

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. Ahmet Mesut Ateş March 27, 2013 Applied Linguistics Karadeniz Technical University. Mould and Cloak Theories.

2.61k views • 15 slides

Hypothesis:

Do the glacial /interglacial changes in sea level influence abyssal hill formation?. Peter Huybers & Charles Langmuir Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138. B athymetry profiles matched to δ 18 O changes,

179 views • 1 slides

Peter Heudtlass Debarati Guha -Sapir

Mapping vulnerability MDGs and Earth observations in disaster epidemiology 2 nd GEOSS Science and Technology Stakeholder Workshop Bonn, Germany, August 28-31, 2012. Peter Heudtlass Debarati Guha -Sapir Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED), Brussels

301 views • 13 slides

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. To what extent, if at all, does our language govern our thought processes?. Grammar . “In substance, grammar is one and the same in all languages, but it may vary accidentally.” Roger Bacon Chomsky – the propensity to receive grammar is innate.

544 views • 9 slides

Defining ‘Culture’ Linguistic Relativity Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

Defining ‘Culture’ Linguistic Relativity Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. Representation Who has the authority to select what is representative of a given culture/ outsider/ insider Culture is ‘heterogeneous’ 1/ social (members differ in age, gender, experience…) 2/ historical (changes over time)

685 views • 7 slides

101 views • 1 slides

Hypothesis. Our next hypothesis: After a 2 year hiatus, does resuscitation skill performance and HFHS trained individuals improve to a greater percentage than traditionally trained didactic only individuals following a didactic only refresher if the team is physician led?. Methods. n= 234

355 views • 16 slides

Pg. 16 Question: Do different brands of gum affect the diameter of a bubble that has been blown?. Hypothesis:. If you chew four pieces of gum, then the __________ brand will make the biggest bubble because …. Materials Needed:. Each group needs:

272 views • 9 slides

The Parkfield Experiment is a comprehensive, long-term earthquake research project on the San Andreas fault. The experiment's purpose is to better understand the physics of earthquakes - what actually happens on the fault and in the surrounding region before, during and after an earthquake

665 views • 45 slides

Whorf Hypothesis